Abstract

Metastatic mature teratoma is a common radiologic and histopathologic finding after chemotherapy for metastatic non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. The leading theory for these residual tumors is the selective chemotherapy resistance of teratomas versus the high chemotherapy sensitivity of the embryonal components. Growing teratoma syndrome is a relatively rare phenomenon defined as an enlarging residual mass histologically proven to be a mature teratoma in the setting of normal serum tumor markers. Metastatic mature teratomas should be resected because of their malignant potential and occasional progression to growing teratoma syndrome with the invasion of the surrounding structures. CT is the preferred imaging modality for post-chemotherapy surveillance and should cover all sites of potential metastatic disease. This article reviews the clinical, pathologic, and multimodality imaging features of metastatic mature teratomas in patients with primary testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumors.

Keywords: Metastatic mature teratoma, Growing teratoma syndrome, Non-seminomatous germ cell tumor, Testicular cancer, Surveillance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic mature teratoma (MMT) is a common residual tumor in patients treated with chemotherapy for metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs). These residual tumors are typically located at the initial sites of metastatic disease and can therefore be mistaken for viable malignancy on surveillance imaging. The leading theory for residual MMT is “chemotherapeutic retroversion”–selective chemotherapy–induced treatment of malignant components with the persistence of teratoma, which is resistant to chemotherapy [1]. Another theory is the de-differentiation of malignant cells into a mature teratoma.

Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is a relatively rare phenomenon characterized by the enlargement or recurrence of residual MMT sites. GTS was first described in 1982 as growing metastases during or after chemotherapy with normalized tumor markers and histologic confirmation of mature teratoma without evidence of embryonal components [2]. Although histopathological examination shows it is benign, GTS can result in complications due to locally aggressive behavior. This article reviews the clinical, pathologic, and multimodality imaging features of patients with metastatic testicular NSGCT presenting with MMT and GTS. These features are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Metastatic Mature Teratoma and Growing Teratoma Syndrome.

| Definition | Clinical Features | Histologic Features | Imaging Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic mature teratoma | - Residual tumor at sites of metastatic NSGCT following chemotherapy | - Usually asymptomatic - Patients have an overall good prognosis after complete resection |

- Well-differentiated tumor with at least one germinal layer - No embryonal malignant cells - Frequent association with necrosis and fibrosis |

- CT: partially cystic, often multiloculated with enhancing septations - Fat and calcification more common in female - MR: variable; T2-hyperintensity due to cystic or necrotic content; T1-hyperintensity due to proteinaceous cyst content; enhancing septations - Ultrasound: partially cystic mass with anechoic fluid spaces - PET-CT: not recommended for post-chemotherapy surveillance of NSGCT; teratoma is non-avid or mildly avid; intense uptake may be indicative of viable malignancy or malignant transformation |

| Growing teratoma syndrome | - Enlarging masses histologically confirmed as metastatic mature teratoma during or after chemotherapy with normalized serum tumor markers | - Potential for local mass effect on or invasion of surrounding structures may result in medical or surgical complications | - Metastatic mature teratoma with enlarged cystic spaces | - Imaging characteristics of metastatic mature teratoma with increasing size and expanding cystic spaces - Potential imaging findings related to urinary, biliary, bowel, or vascular complications |

NSGCT = non-seminomatous germ cell tumor

Clinical Background

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy among male aged 20–34 years. NSGCTs are less common than seminomas, but they are more aggressive. The preferred initial treatment regimen for stage III metastatic NSGCT is orchiectomy followed by cisplatin-based chemotherapy [3]. In most patients, however, serum tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase) normalize after the completion of chemotherapy. Patients with persistently elevated or rising tumor markers after primary chemotherapy subsequently receive salvage chemotherapy regimens. Patients with normal tumor markers after chemotherapy but with residual metastatic masses undergo retroperitoneal lymph node dissection and staged resection of residual disease in other locations.

MMT is common in resected specimens and does not indicate treatment failure. Approximately 35–40% of patients have residual retroperitoneal MMT after induction chemotherapy with 40–50% of masses consisting of necrosis/fibrosis and 10–15% consisting of viable malignancy [4,5]. Among the residual masses with sizes of ≤ 2 cm, 15–26% are MMT, approximately 67% are necrotic/fibrotic, and 4–7% contain viable germ cell tumors [6,7].

Residual MMT is resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy and requires surgical resection, although subcentimeter residual masses can be followed by imaging. With successful treatment, patients with MMT have an overall favorable prognosis (10-year survival of 92% in patients with residual retroperitoneal MMT) [8]. However, recurrence rates are high after incomplete resection, and residual MMT rarely transforms into germ cell or non-germ cell malignancies [9].

Although the behavior of MMT is usually indolent, the incidence of GTS is approximately 3% in patients with advanced NSGCT [10]. Most cases of GTS present within two years of the completion of chemotherapy, but longer disease-free intervals have been reported [11,12]. The factors influencing MMT enlargement consistent with GTS are unclear, although cytokines have been proposed to play a role in biological regulation [13,14]. The potential for local growth involving surrounding structures can result in medical and surgical complications. MMT and GTS have also been described in patients with ovarian and primary mediastinal NSGCTs [14,15].

Pathology

Teratomas are tumors that can contain fully developed tissues and organs originating from one or more of the germinal layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm), including hair, teeth, muscle, and bone. Teratomas are present in approximately 50% of NSGCTs, and most patients with MMT have evidence of teratoma in their primary tumor (Fig. 1) [16]. Other histologic components found in NSGCTs are embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma, and other rare trophoblastic tumors in varying combinations, including seminomas. Pure teratomas of the testes are rare.

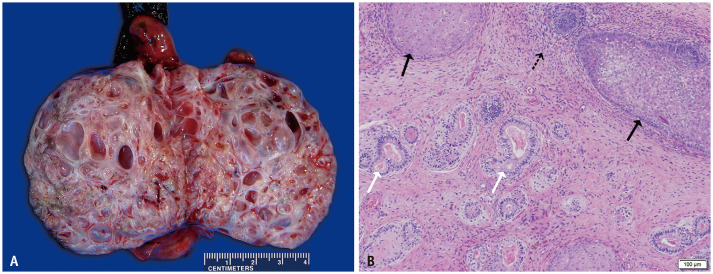

Fig. 1. A 28-year-old male with testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor.

A. Gross examination of the resected testicular tumor shows near-complete replacement of the testicular parenchyma with solid tumor and cystic areas of teratoma. The solid components consisted of teratoma and embryonal carcinoma. B. A histologic slide (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100) shows the teratomatous component with squamous differentiation (black arrows), glandular differentiation (white arrows), and cellular mesenchyme (dashed arrow).

Microscopically, mature teratomas have well-differentiated components with a disordered arrangement and cytologic atypia. Immature teratomas contain incompletely differentiated embryonic tissue. Grossly, teratomas may be solid tumors containing muscle and bone or multicystic tumors composed of dilated glands or entrapped epidermal structures filled with serous, gelatinous, mucinous, or epidermal material (Fig. 1). Sebaceous material, hair, and teeth are more common in ovarian teratomas than in testicular teratomas [16]. In post-pubertal patients, teratomas have malignant potential and may transform into NSGCTs, sarcomas, squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, carcinoid tumors, or primitive neuroectodermal tumors [14].

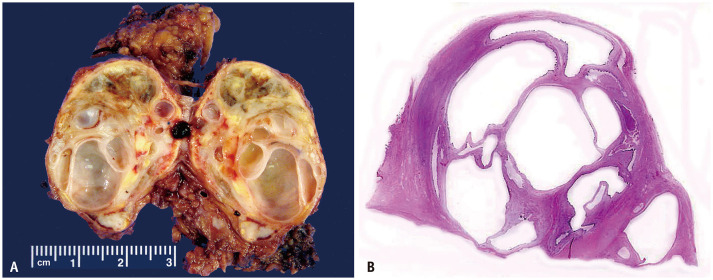

In addition to these features, resected specimens of MMT frequently have necrosis, fibrosis, cholesterol clefts, and histiocytic infiltration corresponding to the remnants of burned-out malignant components. In patients progressing to GTS, MMT tends to develop enlarging cystic spaces (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 2. A 20-year-old male with metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor presenting with growing teratoma syndrome.

A. Gross examination of a resected left para-aortic lymph node shows near-complete invasion by a multicystic metastatic mature teratoma.

B. A whole histologic slide (hematoxylin and eosin stain) correlates with the multicystic structure of the teratoma.

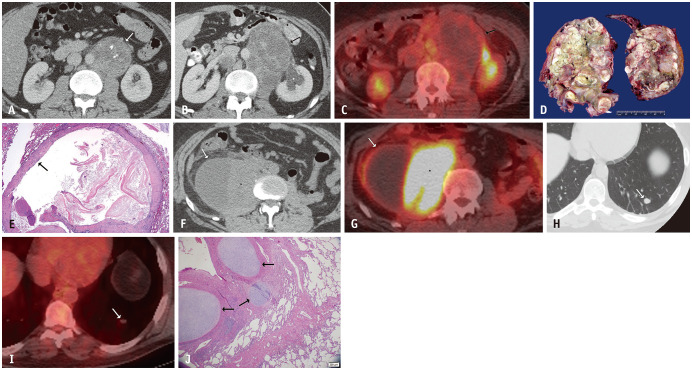

Fig. 3. A 33-year-old male with metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor.

A. Axial contrast-enhanced abdominal CT at the time of presentation showed a solid left retroperitoneal mass with internal calcification (arrow). B. Eight months later, after three cycles of chemotherapy and normalization of tumor markers, an axial contrast-enhanced abdominal CT showed enlargement of the mass with increasing low attenuation predominantly corresponding to necrosis (arrow). The mass also resulted in hydronephrosis of the left kidney (asterisk). C. PET-CT at that time showed no increased FDG-uptake (arrow). D. This mass was resected and gross examination shows near-complete invasion by metastatic mature teratoma with multiple cystic areas filled with yellowish and greenish necrotic material. E. The microscopic appearance of one of the cystic areas (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 2) shows a squamous epithelial lining (arrow) filled with keratinized squamous epithelial flakes and cellular debris. Findings are consistent with growing teratoma syndrome in the setting of normal tumor markers. F, G. The patient again presented three years later with abdominal pain and normal tumor markers. An axial contrast-enhanced abdominal CT (F) and PET-CT (G) showed a large cystic and solid right retroperitoneal mass (arrows). The solid component demonstrated marked FDG-uptake (asterisks). Pathology was consistent with metastatic teratoma with embryonal carcinoma, which does not produce serum markers. He also had three new lung nodules at that time. H, I. Axial chest CT (H) and PET-CT (I) images showed a left lower lobe nodule with no increased FDG-uptake (arrows). J. The nodules were resected and a histologic image of one of the nodules (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 40) shows metastatic mature teratoma with cartilaginous differentiation (arrows) within the alveolar parenchyma of the lung (right side of image). FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose

Imaging Features

CT is the most widely used imaging modality for post-chemotherapy surveillance in patients with metastatic NSGCTs typically obtained approximately four weeks after completion of chemotherapy and covering all regions of potential metastatic disease. This usually includes the abdomen and pelvis and, occasionally, the chest. To limit radiation exposure, some experts advocate chest radiography rather than chest CT in patients without active abdominal disease or tumor marker elevation, given the low likelihood of chest-only disease [5].

Because MMT usually presents at or near the initial metastatic sites, the most common location of MMT in male with testicular NSGCT is the retroperitoneum (up to 80% of patients) [14]. Other potential sites include the liver, lungs, and lymph nodes (iliac, mediastinal, and supraclavicular), while MMT in female with ovarian NSGCT may involve the peritoneum [9,17,18].

Predicting the histology of residual masses is difficult. No imaging reliably differentiates MMT from viable cancer, necrosis, or fibrosis [19]. Likewise, small residual foci of malignancy may not be apparent and do not consistently elevate tumor markers [20]. The size of a residual retroperitoneal mass after chemotherapy is an independent predictor of relapse, and retroperitoneal tumors that shrink by at least 35% after chemotherapy are less likely to contain viable cancer or teratoma, although sensitivity and specificity are only 73% and 82%, respectively [7,21].

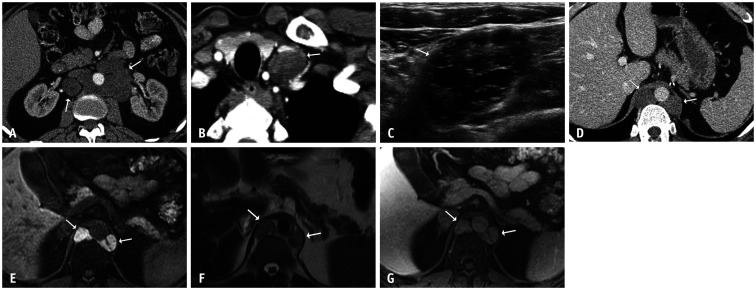

Abdominal MMT is typically a hypoattenuating retroperitoneal mass on CT with cystic or necrotic contents and often multiloculated with enhancing septations (Figs. 3, 4) [20]. Fat and calcification may be present with larger amounts of fat within the MMT than in the primary tumor [22,23]. The MR characteristics of abdominal MMT vary, and they are independent of the presence of necrosis or viable malignancy [24]. Both cystic and necrotic contents in MMT have a high T2 signal. The T1 signal varies with the proteinaceous content of cystic fluid - increasing protein corresponds to an increasing signal (Figs. 4, 5). Subtraction images may help exclude the enhancement of inherently T1-hyperintense masses. Enhancing septations and enhancing tissue may be present. Calcification is less apparent than on CT.

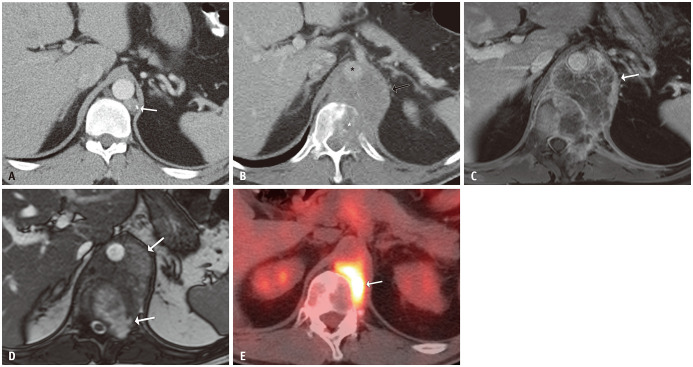

Fig. 4. A 47-year-old male with metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor.

A. After chemotherapy, tumor markers normalized and an axial contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen showed residual low-attenuation periaortic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (arrows). B. An axial contrast-enhanced chest CT image showed a new left supraclavicular lymph node (arrow). C. An ultrasound of the supraclavicular lymph node showed a mixed solid and cystic mass with anechoic spaces (arrow). These masses were resected, and the pathological findings were consistent with metastatic mature teratoma. D-G. Four years later, the patient presented with normal tumor markers and new retrocrural masses (arrows). An axial contrast-enhanced abdominal CT image (D) showed homogeneously low-attenuation masses. A corresponding contrast-enhanced MRI showed marked T1-hyperintensity (E), mild T2-hyperintensity (F), and inherent T1 signal without enhancement on a post-contrast image (G). Note the thin septation within the left retrocrural mass in figure parts (E) and (G) These masses were resected, and the pathological findings demonstrated multicystic masses compatible with metastatic mature teratoma. New left supraclavicular and retrocrural masses with normal tumor markers were consistent with growing teratoma syndrome.

Fig. 5. A 38-year-old male with metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor treated with chemotherapy 6 years earlier.

A. A surveillance axial contrast-enhanced abdominal CT showed a partially calcified left retrocrural lymph node (arrow). No action was taken at that time, and he presented two years later with worsening back pain. B. Axial contrast-enhanced CT showed enlargement of the left retroperitoneal mass (arrow), invading the spine (white asterisk) and encasing and displacing the aorta (black asterisk). C, D. Contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrated peripheral enhancement with enhancing septations (arrow, C) and non-enhancing T2-hyperintensity corresponding to necrosis (arrows, D). E. PET-CT showed fluorodeoxyglucose-uptake along the spine (arrow). The tumor markers were negative, and the pathological findings were consistent with metastatic mature and immature teratomas, which were mostly necrotic with minimal viable malignant tumor.

Mediastinal MMT has imaging features similar to those of retroperitoneal MMT [20,25]. Pulmonary MMT is more likely to appear as solid than cystic on CT; however, necrotic nodules can have low attenuation similar to fluid (Fig. 6) [20]. The cavitation of pulmonary MMT with air-fluid levels has been reported [2,26]. Although ultrasound is not utilized for thoracic disease and may not offer an adequate resolution for evaluating abdominal disease, MMT may be present in accessible regions such as supraclavicular lymph nodes. In these situations, ultrasound can demonstrate the cystic components suggestive of MMT (Fig. 4) [27].

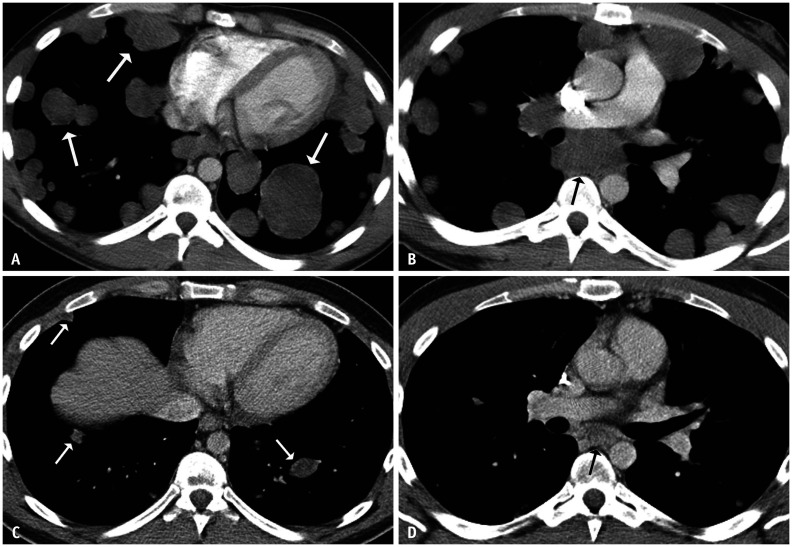

Fig. 6. A 24-year-old male with metastatic testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumor.

At presentation, there was a large retroperitoneal mass (not shown).

A, B. Axial contrast-enhanced chest CT images showed extensive pulmonary metastatic disease (white arrows) and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (black arrow). Following four cycles of chemotherapy, the tumor markers normalized. C, D. A repeat contrast-enhanced CT showed markedly improving pulmonary and mediastinal lesions. The residual lung nodules (white arrows) and a subcarinal lymph node (black arrow) decreased in size and attenuation. Several lung nodules were resected, and the pathological findings were consistent with metastatic mature teratoma with foci of necrosis.

In patients with GTS, enlarging MMT typically demonstrates an expanding cystic component, while increasing solid and enhancing tissue suggests malignant transformation (Fig. 3) [2]. The growth rate in GTS is variable, with a median linear growth rate of 0.5 cm/month [28,29] and rare long-term stabilization [14,30]. Residual masses can grow very large and should be evaluated for the mass effect on or direct invasion of the surrounding structures. Approximately 12% of cases of GTS result in complications, such as urinary, biliary, or bowel obstruction, inferior vena cava compression, aorta encasement and narrowing, and vascular thrombosis (Fig. 3) [14,27]. Most cases of MMT and GTS, however, are asymptomatic (some present with abdominal or back pain) with normal tumor markers, highlighting the importance of surveillance imaging.

PET-CT can be misleading in patients with metastatic NSGCTs, and it currently has no recommended role in post-chemotherapy surveillance or characterization of known diseases [5,25]. MMT may be characterized by anything from no fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake to mild uptake, and viable malignancy may be associated with a higher uptake than MMT. Despite its 90% positive predictive value for the presence of viable malignancy or MMT in residual masses, PET-CT has a high false-negative rate (up to 40%) [25]. Non-FDG-avid MMT cannot be distinguished from necrosis, but it should still be resected (Figs. 3, 5). PET-CT is also limited for the detection of small residual lesions and may miss small foci of malignancy within larger masses.

CONCLUSION

Although metastatic testicular NSGCTs have a high cure rate, residual metastatic masses are common after chemotherapy and may represent viable malignancy, teratoma, necrosis, or fibrosis. MMT should be surgically resected because they are resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Some cases of MMT progress to GTS, which is defined as enlarging MMT during or after chemotherapy with normal serum tumor markers. Imaging features of GTS include an enlarging residual mass with expanding cystic spaces and the potential for malignant transformation or complications due to the involvement of surrounding structures. While no imaging modality can definitively diagnose MMT, post-chemotherapy surveillance imaging is critical in identifying residual sites of disease for curative resection in patients with metastatic NSGCTs and normalized tumor markers.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Daniel B. Green, Paul G. Craig.

- Writing—original draft: Daniel B. Green, Paul G. Craig, Elaine T. Lam.

- Writing—review and editing: all authors.

References

- 1.DiSaia PJ, Saltz A, Kagan AR, Morrow CP. Chemotherapeutic retroconversion of immature teratoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Trindade A, Johnson DE. The growing teratoma syndrome. Cancer. 1982;50:1629–1635. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821015)50:8<1629::aid-cncr2820500828>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilligan T, Lin DW, Aggarwal R, Chism D, Cost N, Derweesh IH, et al. Testicular cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1529–1554. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steyerberg EW, Keizer HJ, Fosså SD, Sleijfer DT, Toner GC, Schraffordt Koops H, et al. Prediction of residual retroperitoneal mass histology after chemotherapy for metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumor: multivariate analysis of individual patient data from six study groups. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1177–1187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daneshmand S, Albers P, Fosså SD, Heidenreich A, Kollmannsberger C, Krege S, et al. Contemporary management of postchemotherapy testis cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;62:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldenburg J, Alfsen GC, Lien HH, Aass N, Waehre H, Fossa SD. Postchemotherapy retroperitoneal surgery remains necessary in patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer and minimal residual tumor masses. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3310–3317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shayegan B, Carver BS, Stasi J, Motzer RJ, Bosl GJ, Sheinfeld J. Clinical outcome following post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in men with intermediate- and poor-risk nonseminomatous germ cell tumour. BJU Int. 2007;99:993–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver BS, Shayegan B, Serio A, Motzer RJ, Bosl GJ, Sheinfeld J. Long-term clinical outcome after postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in men with residual teratoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1033–1037. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maroto P, Tabernero JM, Villavicencio H, Mesía R, Marcuello E, Solé-Balcells FJ, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: experience of a single institution. Eur Urol. 1997;32:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paffenholz P, Pfister D, Matveev V, Heidenreich A. Diagnosis and management of the growing teratoma syndrome: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:529.e23–529.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kikawa S, Todo Y, Minobe S, Yamashiro K, Kato H, Sakuragi N. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary: a case report with FDG-PET findings. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:926–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonneveld DJ, Sleijfer DT, Koops HS, Keemers-Gels ME, Molenaar WM, Hoekstra HJ. Mature teratoma identified after postchemotherapy surgery in patients with disseminated nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: a plea for an aggressive surgical approach. Cancer. 1998;82:1343–1351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980401)82:7<1343::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Gaast A, Kok TC, Splinter TA. Growing teratoma syndrome successfully treated with lymphoblastoid interferon. Eur Urol. 1991;19:257–258. doi: 10.1159/000473633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.André F, Fizazi K, Culine S, Droz J, Taupin P, Lhommé C, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: results of therapy and long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1389–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LT, Chen CL, Hwang WS. The growing teratoma syndrome. A case of primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumor treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Chest. 1990;98:231–233. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahrami A, Ro JY, Ayala AG. An overview of testicular germ cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1267–1280. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1267-AOOTGC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaoka T, Takahashi K, Yamada T, Miyokawa N, Tokusashi Y, Yoshida M, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome secondary to immature teratoma of the ovary. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2115–2118. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umekawa T, Tabata T, Tanida K, Yoshimura K, Sagawa N. Growing teratoma syndrome as an unusual cause of gliomatosis peritonei: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:761–763. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stomper PC, Kalish LA, Garnick MB, Richie JP, Kantoff PW. CT and pathologic predictive features of residual mass histologic findings after chemotherapy for nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: can residual malignancy or teratoma be excluded? Radiology. 1991;180:711–714. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.3.1651526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panicek DM, Toner GC, Heelan RT, Bosl GJ. Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: enlarging masses despite chemotherapy. Radiology. 1990;175:499–502. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2158120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda Ede P, Abe DK, Nesrallah AJ, dos Reis ST, Crippa A, Srougi M, et al. Predicting necrosis in residual mass analysis after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:203. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kattan J, Droz JP, Culine S, Duvillard P, Thiellet A, Peillon C. The growing teratoma syndrome: a woman with nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;49:395–399. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han NY, Sung DJ, Park BJ, Kim MJ, Cho SB, Kim KA, et al. Imaging features of growing teratoma syndrome following a malignant ovarian germ cell tumor. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2014;38:551–557. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfannenberg AC, Oechsle K, Bokemeyer C, Kollmannsberger C, Dohmen BM, Bares R, et al. The role of [18F] FDG-PET, CT/MRI and tumor marker kinetics in the evaluation of post chemotherapy residual masses in metastatic germ cell tumors--prospects for management. World J Urol. 2004;22:132–139. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aide N, Comoz F, Sevin E. Enlarging residual mass after treatment of a nonseminomatous germ cell tumor: growing teratoma syndrome or cancer recurrence? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4494–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coscojuela P, Llauger J, Pérez C, Germá J, Castañer E. The growing teratoma syndrome: radiologic findings in four cases. Eur J Radiol. 1991;12:138–140. doi: 10.1016/0720-048x(91)90116-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorigan JG, Eftekhari F, David CL, Shirkhoda A. The growing teratoma syndrome: an unusual manifestation of treated, nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:325–329. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiess PE, Kassouf W, Brown GA, Kamat AM, Liu P, Gomez JA, et al. Surgical management of growing teratoma syndrome: the M. D. Anderson cancer center experience. J Urol. 2007;177:1330–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee DJ, Djaladat H, Tadros NN, Movassaghi M, Tejura T, Duddalwar V, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: clinical and radiographic characteristics. Int J Urol. 2014;21:905–908. doi: 10.1111/iju.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffery GM, Theaker JM, Lee AH, Blaquiere RM, Smart CJ, Mead GM. The growing teratoma syndrome. Br J Urol. 1991;67:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1991.tb15109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]