Abstract

We introduce the AusTraits database - a compilation of values of plant traits for taxa in the Australian flora (hereafter AusTraits). AusTraits synthesises data on 448 traits across 28,640 taxa from field campaigns, published literature, taxonomic monographs, and individual taxon descriptions. Traits vary in scope from physiological measures of performance (e.g. photosynthetic gas exchange, water-use efficiency) to morphological attributes (e.g. leaf area, seed mass, plant height) which link to aspects of ecological variation. AusTraits contains curated and harmonised individual- and species-level measurements coupled to, where available, contextual information on site properties and experimental conditions. This article provides information on version 3.0.2 of AusTraits which contains data for 997,808 trait-by-taxon combinations. We envision AusTraits as an ongoing collaborative initiative for easily archiving and sharing trait data, which also provides a template for other national or regional initiatives globally to fill persistent gaps in trait knowledge.

Subject terms: Ecology, Evolution, Ecology

| Measurement(s) | plant trait |

| Technology Type(s) | digital curation |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Viridiplantae |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Australia |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.14545755

Background & Summary

Species traits are essential for comparing ecological strategies among plants, both within any given vegetation and across environmental space or evolutionary lineages1–4. Broadly, a trait is any measurable property of a plant capturing aspects of its structure or function5–8. Traits thereby provide useful indicators of species’ behaviours in communities and ecosystems, regardless of their taxonomy8–10. Through global initiatives the volume of available trait information for plants has grown rapidly in the last two decades11,12. However, the geographic coverage of trait measurements across the globe is patchy, limiting detailed analyses of trait variation and diversity in some regions, and, more generally, development of theory accounting for the diversity of plant strategies.

One such region where trait data is sparsely documented is Australia; a continent with a flora of c. 28,900 native vascular plant taxa13 (including species, subspecies, varietas and forma). While significant investment has been made in curating and digitising herbarium collections and observation records in Australia over the last two decades (e.g. The Australian Virtual Herbarium houses ~7 million specimen occurrence records; https://avh.ala.org.au), no complementary resource yet exists for consolidating information on plant traits. Moreover, relatively few Australian species are represented in the leading global databases. For example, the international TRY database12 has measurements for only 3830 Australian species across all collated traits. This level of species coverage limits our ability to use traits to understand and ultimately manage Australian vegetation14. While initiatives such as TRY12 and the Open Traits Network15 are working towards global synthesis of trait data, a stronger representation of Australian plant taxa in these efforts is essential, especially given the high richness and endemicity of this continental flora, and the unique contribution this makes to global floral diversity16,17.

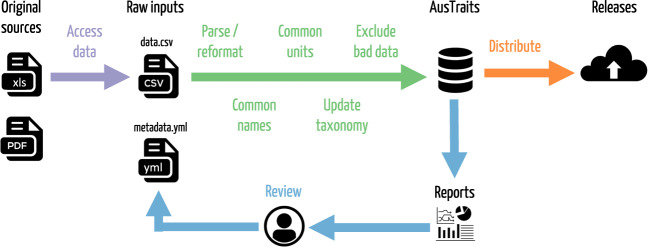

Here we introduce the AusTraits database (hereafter AusTraits), a compilation of plant traits for the Australian flora. Currently, AusTraits draws together 283 distinct sources and contains 997,808 measurements spread across 448 different traits for 28,640 taxa. To assemble AusTraits from diverse primary sources and make data available for reuse, we needed to overcome three main types of challenges (Fig. 1): (1) Accessing data from diverse original sources, including field studies, online databases, scientific articles, and published taxonomic floras; (2) Harmonising these diverse sources into a federated resource, with common taxon names, units, trait names, and data formats; and (3) Distributing versions of the data under suitable license. To meet this challenge, we developed a workflow which draws on emerging community standards and our collective experience building trait databases.

Fig. 1.

The data curation pathway used to assemble the AusTraits database. Trait measurements are accessed from original data sources, including published floras and field campaigns. Features such as variable names, units and taxonomy are harmonised to a common standard. Versioned releases are distributed to users, allowing the dataset to be used and re-used in a reproducible way.

By providing a harmonised and curated dataset on 448 plant traits, AusTraits contributes substantially to filling the gap in Australian and global biodiversity resources. Prior to the development of AusTraits, data on Australian plant traits existed largely as a series of disconnected datasets collected by individual laboratories or initiatives.

AusTraits has been developed as a standalone database, rather than as part of the existing global database TRY12, for three reasons. First, we sought to establish an engaged and localised community, actively collaborating to enhance coverage of plant trait data within Australia. We envisioned that a community would form more readily to fill gaps in national knowledge of traits with local ownership of the resource. While we will never have a counterfactual, a vibrant community excited to be part of this initiative has indeed been established and coverage is much higher for Australian species than has been achieved since TRY’s inception. Local ownership also aligns well with funding opportunities and national research priorities, and enables database coordinators to progress at their own speed. Second, we wanted to apply an entirely open-source approach to the aggregation workflow. All the code and raw files used to create the compiled database are available, and this database is freely available via a third party data repository (Zenodo) which is itself built for long term data archiving, with an established API. Finally, we targeted primary data sources, where possible, whereas TRY accepts aggregated datasets. The hope was that this would increase data quality, by removing intermediaries and easier identification of duplicates.

While independent, the overall structure of AusTraits is similar to that of TRY, ensuring the two databases will be interoperable. Both databases are founded on similar principles and terminology18,19. Increasingly, researchers and biodiversity portals are seeking to connect diverse datasets15, which is possible if they share a common foundation.

We envision AusTraits as an on-going collaborative initiative for easily archiving and sharing trait data about the Australian flora. Open access to a comprehensive resource like this will generate significant new knowledge about the Australian flora across multiple scales of interest, as well as reduce duplication of effort in the compilation of plant trait data, particularly for research students and government agencies seeking to access information on traits. In coming years, AusTraits will continue to be expanded, with integrations into other biodiversity platforms and expansion of coverage into historically neglected plant lineages in trait science, such as pteridophytes (lycophytes and ferns). Further, through international initiatives, such as the Open Traits Network, linkages are being forged between plant datasets and a variety of other organismal databases15.

Methods

Primary sources

AusTraits version 3.0.2 was assembled from 283 distinct sources, including published papers, field measurements, glasshouse and field experiments, botanical collections, and taxonomic treatments. Initially we identified a list of candidate traits of interest, then identified primary sources containing measurements for these traits, before contacting authors for access. As the compilation grew, we expanded the list of traits considered to include any measurable quantity that had been quantified for at least a moderate number of taxa (n > 20).

For a small subset of sources from herbaria, providing a text description of taxa, we used regular expressions in R to extract measurements of traits from the text. A variety of expressions were developed to extract height, leaf/seed dimensions and growth form. Error checking was completed on approximately 60% of mined measurements by visually inspecting the extracted values relative to the textual descriptions.

Trait definitions

A full list of traits and their sources appears in Supplementary Table 120–354 . The list of sources in AusTraits was developed gradually as new datasets were incorporated, drawing from original source publications and a published thesaurus of plant characteristics19. We categorised traits based on the tissue where it is measured (bark, leaf, reproductive, root, stem, whole plant) and the type of measurement (allocation, life history, morphology, nutrient, physiological). Version 3.0.2 of AusTraits includes 358 numeric and 90 categorical traits.

Database structure

The schema of AusTraits broadly follows the principles of the established Observation and Measurement Ontology18 in that, where available, trait data are connected to contextual information about the collection (e.g. location coordinates, light levels, whether data were collected in the field or lab) and information about the methods used to derive measurements (e.g. number of replicates, equipment used). The database contains 11 elements, as described in Table 1. This format was developed to include information about the trait measurements, taxon, methods, sites, contextual information, people involved, and citation sources.

Table 1.

| Element | Contents |

|---|---|

| traits | A table containing measurements of plant traits. |

| sites | A table containing observations of site characteristics associated with information in ‘traits’. Cross referencing between the two dataframes is possible using combinations of the variables ‘dataset_id’, ‘site_name’. |

| contexts | A table containing observations of contextual characteristics associated with information in ‘traits’. Cross referencing between the two dataframes is possible using combinations of the variables ‘dataset_id’, ‘context_name’. |

| methods | A table containing details on methods with which data were collected, including time frame and source. |

| excluded_data | A table of data that did not pass quality test and so were excluded from the master dataset. |

| taxa | A table containing details on taxa associated with information in ‘traits’. This information has been sourced from the APC (Australian Plant Census) and APNI (Australian Plant Name Index) and is released under a CC-BY3 license. |

| definitions | A copy of the definitions for all tables and terms. Information included here was used to process data and generate any documentation for the study. |

| sources | Bibtex entries for all primary and secondary sources in the compilation. |

| contributors | A table of people contributing to each study. |

| taxonomic_updates | A table of all taxonomic changes implemented in the construction of AusTraits. Changes are determined by comparing against the APC (Australian Plant Census) and APNI (Australian Plant Name Index). |

| build_info | A description of the computing environment used to create this version of the dataset, including version number, git commit and R session_info. |

For storage efficiency, the main table of traits contains relatively little information (Table 2), but can be cross linked against other tables (Tables 3–8) using identifiers for dataset, site, context, observation, and taxon (Table 1). The dataset_id is ordinarily the surname of the first author and year of publication associated with the source’s primary citation (e.g. Blackman_2014). Trait values were also recorded as being one of several possible value types (value_type) (Table 9), reflecting the type of measurement submitted by the contributor, as different sources provide different levels of detail. Possible values include raw_value, individual_mean, site_mean, multisite_mean, expert_mean, experiment_mean. Further details on the methods used for collecting each trait are provided in a methods table (Table 5).

Table 4.

Structure of the contexts table, containing observations of contextual characteristics associated with information in traits.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| context_name | Name of contextual senario where individual was sampled. Cross-references to identical columns in ‘contexts’ and ‘traits’. |

| context_property | The contextual characteristic being recorded. Name should include units of measurement, e.g. ‘CO2 concentration (ppm)’. |

| value | Measured value. |

Table 2.

Structure of the traits table, containing measurements of plant traits.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| taxon_name | Currently accepted name of taxon in the Australian Plant Census or in the Australian Plant Name Index. |

| site_name | Name of site where individual was sampled. Cross-references to identical columns in ‘sites’ and ‘traits’. |

| context_name | Name of contextual senario where individual was sampled. Cross-references to identical columns in ‘contexts’ and ‘traits’. |

| observation_id | A unique identifier for the observation, useful for joining traits coming from the same ‘observation_id’. These are assigned automatically, based on the ‘dataset_id’ and row number of the raw data. |

| trait_name | Name of trait sampled. |

| value | Measured value. |

| unit | Units of the sampled trait value after aligning with AusTraits standards. |

| date | Date sample was taken, in the format ‘yyyy-mm-dd’, but with days and months only when specified. |

| value_type | A categorical variable describing the type of trait value recorded. |

| replicates | Number of replicate measurements that comprise the data points for the trait for each measurement. A numeric value (or range) is ideal and appropriate if the value type is a ‘mean’, ‘median’, ‘min’ or ‘max’. For these value types, if replication is unknown the entry should be ‘unknown’. If the value type is ‘raw_value’ the replicate value should be 1. If the value type is ‘expert_mean’, ‘expert_min’, or ‘expert_max’ the replicate value should be ‘na’. |

| original_name | Name given to taxon in the original data supplied by the authors |

Table 3.

Structure of the sites table, containing observations of site characteristics associated with information in traits.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| site_name | Name of site where individual was sampled. Cross-references to identical columns in ‘sites’ and ‘traits’. |

| site_property | The site characteristic being recorded. Name should include units of measurement, e.g. ‘longitude (deg)’. Ideally we have at least these variables for each site - ‘longitude (deg)’, ‘latitude (deg)’, ‘description’. |

| value | Measured value. |

Table 8.

Structure of the contributors table, of people contributing to each study.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| name | Name of contributor |

| institution | Last known institution or affiliation |

| role | Their role in the study |

Table 9.

Possible value types of trait records.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| raw_value | Value is a direct measurement |

| site_min | Value is the minimum of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon at a single site |

| site_mean | Value is the mean or median of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon at a single site |

| site_max | Value is the maximum of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon at a single site |

| multisite_min | Value is the minimum of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon across multiple sites |

| multisite_mean | Value is the mean or median of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon across multiple sites |

| multisite_max | Value is the maximum of measurements on multiple individuals of the taxon across multiple sites |

| expert_min | Value is the minimum observed for a taxon across its range or in this particular dataset, as estimated by an expert based on their knowledge of the taxon. Data fitting this category include estimates from floras that represent a taxon’s entire range. |

| expert_mean | Value is the mean observed for a taxon across its range or in this particular dataset, as estimated by an expert based on their knowledge of the taxon. Data fitting this category include estimates from floras that represent a taxon’s entire range, and values for categorical variables obtained from a reference book, or identified by an expert. |

| expert_max | Value is the maximum observed for a taxon across its range or in this particular dataset, as estimated by an expert based on their knowledge of the taxon. Data fitting this category include estimates from floras that represent a taxon’s entire range. |

| experiment_min | Value is the minimum of measurements from an experimental study either in the field or a glasshouse |

| experiment_mean | Value is the mean or median of measurements from an experimental study either in the field or a glasshouse |

| experiment_max | Value is the maximum of measurements from an experimental study either in the field or a glasshouse |

| individual_mean | Value is a mean of replicate measurements on an individual (usually for experimental ecophysiology studies) |

| individual_max | Value is a maximum of replicate measurements on an individual (usually for experimental ecophysiology studies) |

| literature_source | Value is a site or multi-site mean that has been sourced from an unknown literature source |

| unknown | Value type is not currently known |

Table 5.

Structure of the methods table, containing details on methods with which data were collected, including time frame and source.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| trait_name | Name of trait sampled. Allowable values specified in the table ‘traits’. |

| methods | A textual description of the methods used to collect the trait data. Whenever available, methods are taken near-verbatim from referenced source. Methods can include descriptions such as ‘measured on botanical collections’, ‘data from the literature’, or a detailed description of the field or lab methods used to collect the data. |

| year_collected_start | The year data collection commenced. |

| year_collected_end | The year data collection was completed. |

| description | A 1–2 sentence description of the purpose of the study. |

| collection_type | A field to indicate where the majority of plants on which traits were measured were collected - in the ‘field’, ‘lab’, ‘glasshouse’, ‘botanical collection’, or ‘literature’. The latter should only be used when the data were sourced from the literature and the collection type is unknown. |

| sample_age_class | A field to indicate if the study was completed on ‘adult’ or ‘juvenile’ plants. |

| sampling_strategy | A written description of how study sites were selected and how study individuals were selected. When available, this information is copied verbatim from a published manuscript. For botanical collections, this field ideally indicates which records were ‘sampled’ to measure a specific trait. |

| source_primary_citation | Citation for primary source. This detail is generated from the primary source in the metadata. |

| source_primary_key | Citation key for primary source in ‘sources’. The key is typically of format ‘Surname_year’. |

| source_secondary_citation | Citations for secondary source. This detail is generated from the secondary source in the metadata. |

| source_secondary_key | Citation key for secondary source in ‘sources’. The key is typically of format ‘Surname_year’. |

Harmonisation

To harmonise each source into the common AusTraits format we applied a reproducible and transparent workflow (Fig. 1), written in R355, using custom code, and the packages tidyverse356, yaml357, remake358, knitr359, and rmarkdown360. In this workflow, we performed a series of operations, including reformatting data into a standardised format, generating observation ids for each set of linked measurements, transforming variable names into common terms, transforming data into common units, standardising terms (trait values) for categorical variables, encoding suitable metadata, and flagging data that did not pass quality checks. Details from each primary source were saved with minimal modification into two plain text files. The first file, data.csv, contains the actual trait data in comma-separated values format. The second file, metadata.yml, contains relevant metadata for the study, as well as options for mapping trait names and units onto standard types, and any substitutions applied to the data in processing. These two files provide all the information needed to compile each study into a standardised AusTraits format. Successive versions of AusTraits iterate through the steps in Fig. 1, to incorporate new data and correct identified errors, leading to a high-quality, harmonised dataset.

After importing a study, we generated a detailed report which summarised the study’s metadata and compared the study’s data values to those collected by other studies for the same traits. Data for continuous and categorical variables are presented in scatter plots and tables respectively. These reports allow first the AusTraits data curator, followed by the data contributor, to rapidly scan the metadata to confirm it has been entered correctly and the trait data to ensure it has been assigned the correct units and their categorical traits values are properly aligned with AusTraits trait values.

Taxonomy

We developed a custom workflow to clean and standardise taxonomic names using the latest and most comprehensive taxonomic resources for the Australian flora: the Australian Plant Census (APC)13 and the Australian Plant Name Index (APNI)361. These resources document all known taxonomic names for Australian plants, including currently accepted names and synonyms. While several automated tools exist for updating taxonomy, such as taxize362, these do not currently include up to date information for Australian taxa. Updates were completed in two steps. In the first step, we used both direct and then fuzzy matching (with up to 2 characters difference) to search for an alignment between reported names and those in three name sets: 1) All accepted taxa in the APC, 2) All known names in the APC, 3) All names in the APNI. Names were aligned without name authorities, as we found this information was rarely reported in the raw datasets provided to us. Second, we used the aligned name to update any outdated names to their current accepted name, using the information provided in the APC. If a name was recorded as being both an accepted name and an alternative (e.g. synonym) we preferred the accepted name, but also noted the alternative records. For phrase names, when a suitable match could not be found, we manually reviewed near matches via web portals such as the Atlas of Living Australia to find a suitable match. The final resource reports both the original and the updated taxon name alongside each trait record (Table 2), as well as an additional table summarising all taxonomic name changes (Table 6) and further information from the APC and APNI on all taxa included (Table 7). Any changes in taxonomy are exposed within the compiled dataset, enabling researchers to review these as needed.

Table 6.

Structure of the taxonomic_updates table, of all taxonomic changes implemented in the construction of AusTraits. Changes are determined by comparing against the APC (Australian Plant Census) and APNI (Australian Plant Name Index).

| key | value |

|---|---|

| dataset_id | Primary identifier for each study contributed into AusTraits; most often these are scientific papers, books, or online resources. By default should be name of first author and year of publication, e.g. ‘Falster_2005’. |

| original_name | Name given to taxon in the original data supplied by the authors |

| cleaned_name | Name of the taxon after implementing any changes encoded for this taxon in the metadata file for the correpsonding ‘dataset_id’. |

| taxonIDClean | Where it could be identified, the ‘taxonID’ of the ‘cleaned_name’ for this taxon in the APC. |

| taxonomicStatusClean | Taxonomic status of the taxon identified by ‘taxonIDClean’ in the APC. |

| alternativeTaxonomicStatusClean | The status of alternative records with the name ‘cleaned_name’ in the APC. |

| acceptedNameUsageID | ID of the accepted name for taxon in the APC or APNI. |

| taxon_name | Currently accepted name of taxon in the APC or in the APNI . |

Table 7.

Structure of the taxa table, containing details on taxa associated with information in the traits table. This information has been sourced from the APC (Australian Plant Census) and APNI (Australian Plant Name Index) and is released under a CC-BY3 license.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| taxon_name | Currently accepted name of taxon in the APC or in the APNI . |

| source | Source of taxnonomic information, either APC or APNI. |

| acceptedNameUsageID | ID of the accepted name for taxon in the APC or APNI. |

| scientificNameAuthorship | Authority for taxon indicated under taxon_name. |

| taxonRank | Rank of the taxon. |

| taxonomicStatus | Taxonomic status of the taxon. |

| family | Family of the taxon. |

| genus | Genus of the taxon. |

| taxonDistribution | Known distribution of the taxon, by state. |

| ccAttributionIRI | Source of taxonomic information. |

Data Records

Access

Static versions of AusTraits, including version 3.0.2 used in this descriptor, are available via Zenodo363. Data is released under a CC-BY license enabling reuse with attribution – being a citation of this descriptor and, where possible, original sources. Deposition within Zenodo helps makes the dataset consistent with FAIR principles364. As an evolving data product, successive versions of AusTraits are being released, containing updates and corrections. Versions are labeled using semantic versioning to indicate the change between versions365. As validation (see Technical Validation, below) and data entry are ongoing, users are recommended to pull data from release, to ensure results in their downstream analyses remain consistent as the database is updated.

The R package austraits (https://github.com/traitecoevo/austraits) provides easy access to data and examples on manipulating data (e.g. joining tables, subsetting) for those using this platform.

Data coverage

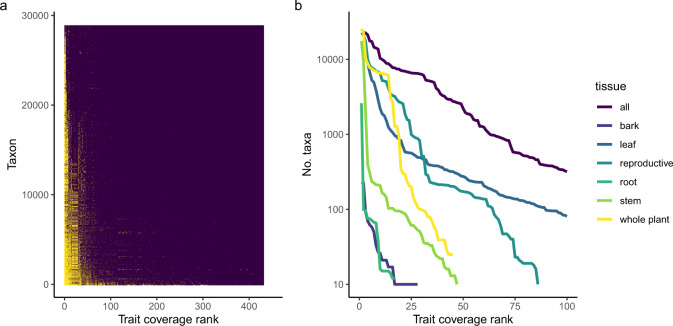

The number of accepted vascular plant taxa in the APC (as of May 2020) is around 28,98113. Version 3.0.2 of AusTraits includes at least one record for 26,852 taxa (~93% of known taxa). Five traits (leaf_length, leaf_width, plant_height, life_history, plant_growth_form) have records for more than 50% of known species (Fig. 2a). Across all traits, the median number of taxa with records is 62. Supplementary Table 1 shows the number of studies, taxa, and families with data in AusTraits, as well as the number of geo-referenced records, for each trait. Looking across traits and tissue categories, coverage declined gradually, with moderate coverage(>20%) for more than 50 traits (Fig. 2). Coverage for root, stem and bark traits declined much faster than trait measurements for other plant tissues (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Coverage of traits by taxa. (a) Matrix showing the coverage of taxa for each trait, with yellow indicating presence of data. The figure was generated with a subset of 500 randomly selected taxa. (b) Number of taxa with data for first 100 traits for all traits and separated by tissue.

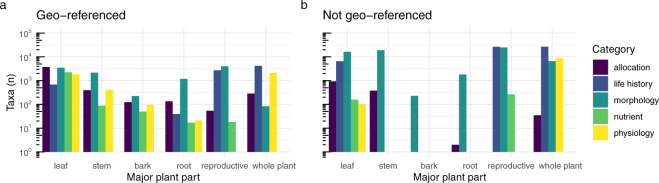

The most common traits are non geo-referenced records from floras; these are trait values representing a continental or region mean (or spread) and hence are not linked to a location. Yet, geo-referenced records were available for several traits for more than 10% of the flora (Fig. 3a). Coverage is notably higher for geo-referenced measurements of some tissues and trait types - such as bark stems and roots - relative to non-geo-referenced measurements (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of taxa with trait records by plant tissue and trait category, for data that are (a) Geo-referenced, and (b) Not geo-referenced. Many records without a geo-reference come from botanical collections, such as floras.

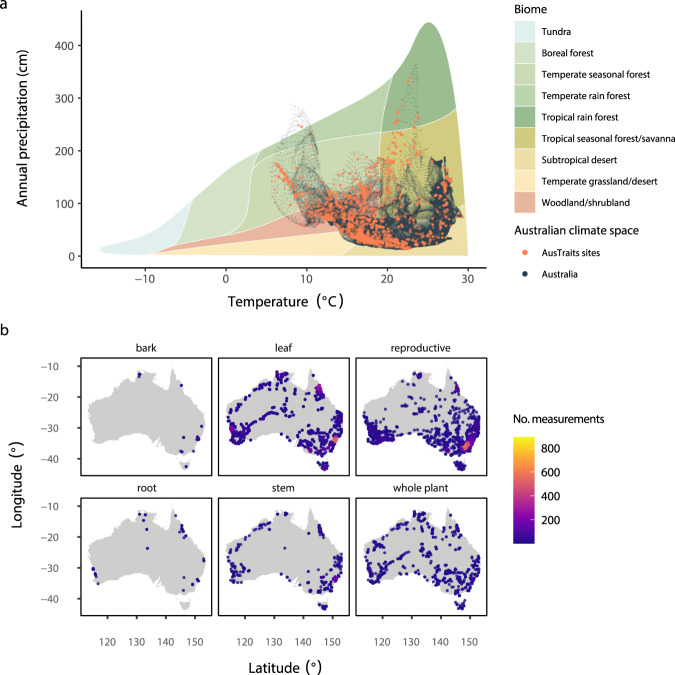

Trait records are spread across the climate space of Australia (Fig. 4a), as well as geographic locations (Fig. 4b). As with most data in Australia, the density of records was somewhat concentrated around cities or roads in remote regions.

Fig. 4.

Coverage of geo-referenced trait records across Australian climatic and geographic space for traits in different categories. (a) AusTraits’ sites (orange) within Australia’s precipitation-temperature space (dark-grey) superimposed upon Whittaker’s classification of major biomes by climate370. Climate data were extracted at 10" resolution from WorldClim371. (b) Locations of geo-referenced records for different plant tissues.

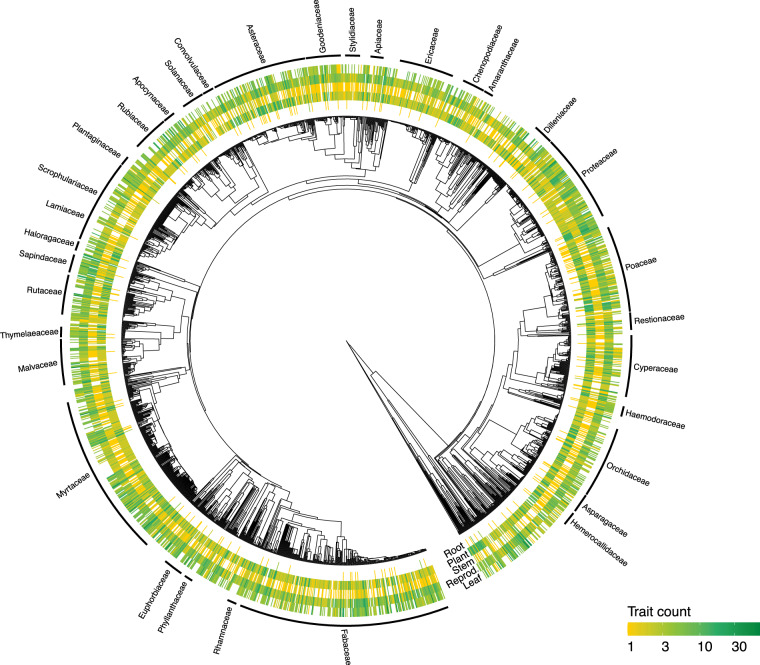

Overall trait coverage across an estimated phylogenetic tree of Australian plant species is relatively unbiased (Fig. 5), though there are some notable exceptions. One exception is for root traits, where taxa within Poaceae have large amounts of information available relative to other plant families. A cluster of taxa within the family Myrtaceae which are largely from Western Australia have little leaf information available.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic distribution of trait data in AusTraits for a subset of 2000 randomly sampled taxa. The heatmap colour intensity denotes the number of traits measured within a family for each plant tissue. The most widespread family names (with more than ten taxa) are labelled on the edge of the tree.

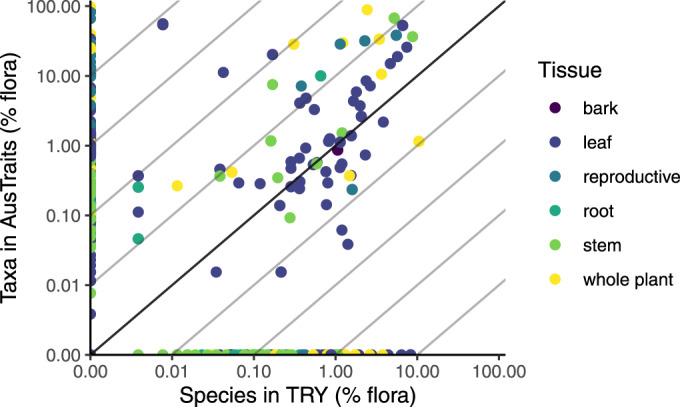

Comparing coverage in AusTraits to the global database TRY, there were 76 traits overlapping. Of these, AusTraits tended to contain records for more taxa, but not always; multiple traits had more than 10 times the number of taxa represented in AusTraits (Fig. 6). However, there were more records in TRY for 25 traits, in particular physiological leaf traits. Many traits were not overlapping between the two databases (Fig. 6). We noted that AusTraits includes more seed and fruit nutrient data; possibly reflecting the interest in Australia in understanding how fruit and seeds are provisioned in nutrient-depauperate environments. AusTraits includes more categorical values, especially variables documenting different components of species’ fire response strategies, reflecting the importance of fire in shaping Australian communities and the research to document different strategies species have evolved to succeed in fire-prone environments.

Fig. 6.

The number of taxa with trait records in AusTraits and global TRY database (accessed 28 May 2020). Each point shows a separate trait.

Technical Validation

We implemented three strategies to maintain data quality. First, we conducted a detailed review of each source based on a bespoke report, showing all data and metadata, by both an AusTraits curator (primarily Wenk) and the original contributor (where possible). Measurements for each trait were plotted against all other values for the trait in AusTraits, allowing quick identification of outliers. Corrections suggested by contributors were combined back into AusTraits and made available with the next release. Version 3.0.2 of AusTraits, described here, is the sixth release.

Second, we implemented automated tests for each dataset, to confirm that values for continuous traits fall within the accepted range for the trait, and that values for categorical traits are on a list of allowed values. Data that did not pass these tests were moved to a separate spreadsheet (“excluded_data”) that is also made available for use and review.

Third, we provide a pathway for user feedback. AusTraits is an open-source community resource and we encourage engagement from users on maintaining the quality and usability of the dataset. As such, we welcome reporting of possible errors, as well as additions and edits to the online documentation for AusTraits that make using the existing data, or adding new data, easier for the community. Feedback can be posted as an issue directly at the project’s GitHub page (http://traitecoevo.github.io/austraits.build).

Usage Notes

Each data release is available in multiple formats: first, as a compressed folder containing text files for each of the main components, second, as a compressed R object, enabling easy loading into R for those using that platform.

Using the taxon names aligned with the APC, data can be queried against location data from the Atlas of Living Australia. To create the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 6, we pruned a master tree for all higher plants366 using the package V.PhyloMaker367 and visualising via ggtree368. To create Fig. 3a, we used the package plotbiomes369 to create the baseline plot of biomes.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of all Australian taxonomists and their supporting institutions, whose long-term work on describing the flora has provided a rich source of data for AusTraits, including: Australian National Botanic Gardens; Australian National Herbarium; Biodiversity Science, Parks Australia; Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research; Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Western Australia; Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria; Flora of Australia; Kew; National Herbarium of NSW; National Herbarium of Victoria; Northern Territory Herbarium; NSW Department of Planning, Industry, and Environment; Queensland Herbarium; State Herbarium of South Australia; Tasmanian Herbarium; and the Western Australian Herbarium. We gratefully acknowledge input from the following persons who contributed to data collection Sophia Amini, Julian Ash, Tara Boreham, Ross Bradstock, Willi A. Brand, Amber Briggs, John Brock, Don Butler, Robert Chinnock, Peter Clarke, Derek Clayton, Steven Clemants, Harold Trevor Clifford, Michelle Cochrane, Bronwyn Collins, Alessandro Conti, Wendy Cooper, William Cooper, Ian Cowie, Lyn Craven, Ian Davidson, Derek Eamus, Judy Egan, Chris Fahey, Paul Irwin Forster, John Foster, Tony French, Allison Frith, Ronald Gardiner, Malcolm Gill, Ethel Goble-Garratt, Peter Grubb, Chris Guinane, TJ Hall, Monique Hallet, Tammy Haslehurst, Foteini Hassiotou, John Herbohn, Peter Hocking, Jing Hu, Kate Hughes, Muhammad Islam, Ian Kealley, Greg Keighery, James Kirkpatrick, Kirsten Knox, Luka Kovac, Kaely Kreger, John Kuo, Martin Lambert, Dana Lanceman, Michael Lawes, Claire Laws, Emma Laxton, Liz Lindsay, Daniel Montoya Londono, Christiane Ludwig, Ian Lunt, Mary Maconochie, Karen Marais, Bruce Maslin, Riah Mason, Richard Mazanec, Elissa McFarlane, Huw Morgan, Peter Myerscough, Des Nelson, Dominic Neyland, Mike Olsen, Corinna Orscheg, Jacob McC. Overton, Paula Peeters, George Perry, Aaron Phillips, Loren Pollitt, Rob Polmear, Hugh Possingham, Aina Price, Thomas Pyne, R.J.Williams, Barbara Rice, Jessica L. Rigg, Bryan Roberts, Miguel de Salas, Anna Salomaa, Inge Schulze, Waltraud Schulze, Andrew John Scott, Alison Shapcott, Veronica Shaw, Luke Shoo, Anne Sjostrom, Santiago Soliveres, Amanda Spooner, George Stewart, Jan Suda, Catherine Tait, Daniel Taylor, Ian Thompson, Hellmut R. Toelken, Malcolm Trudgen, W.E Westman, Erica Williams, Kathryn Willis, J. Bastow Wilson, Jian Yen. We thank H Cornelissen, H Poorter, SC McColl-Gausden, and one anonymous reviewer for feedback on an earlier draft, and K Levett for advice on data structures. This work was supported by fellowship grants from Australian Research Council to Falster (FT160100113), Gallagher (DE170100208) and Wright (FT100100910). The AusTraits project received investment (10.47486/TD044, 10.47486/DP720) from the Australian Research Data Commons (ARDC). The ARDC is funded by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

Author contributions

R.V.G., I.J.W. conceived the original idea; R.V.G., E.H.W., C.B., S.A. collated data from primary sources; D.S.F. developed the workflow for the harmonising of data and led all coding; E.H.W., D.I., S.C.A., J.L. contributed to coding; E.H.W., S.C.A., C.B., J.L. error-checked trait measurements; A.M., A.F. assisted with workflow for updating taxonomy; D.I. developed figures for the paper; F.K., D.S.F. developed the R package; D.S.F., R.V.G., D.I., E.H.W. wrote the first draft of the paper. All other authors contributed the raw data and metadata underpinning the resource, reviewed the harmonised data for errors, and reviewed the final paper for publication.

Code availability

All code, raw and compiled data are hosted within GitHub repositories under the Trait Ecology and Evolution organisation (http://traitecoevo.github.io/austraits.build/). The archived material includes all data sources and code for rebuilding the compiled dataset. The code used to produce this paper is available at http://github.com/traitecoevo/austraits_ms.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Daniel Falster, Rachael Gallagher.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-021-01006-6.

References

- 1.Zanne AE, et al. Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments. Nature. 2014;506:89. doi: 10.1038/nature12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornwell WK, et al. Functional distinctiveness of major plant lineages. J. Ecol. 2014;102:345–356. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díaz S, et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature. 2016;529:167. doi: 10.1038/nature16489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunstler G, et al. Plant functional traits have globally consistent effects on competition. Nature. 2016;529:204. doi: 10.1038/nature16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapin FS, III, Autumn K, Pugnaire F. Evolution of suites of traits in response to environmental stress. Am. Nat. 1993;142:S78–S92. doi: 10.1086/285524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler PB, et al. Functional traits explain variation in plant life history strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:740–745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315179111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz S, Cabido M, Casanoves F. Plant functional traits and environmental filters at a regional scale. J. Veg. Sci. 1998;9:113–122. doi: 10.2307/3237229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Violle C, et al. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos. 2007;116:882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westoby M. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecol. Strategy scheme. Plant Soil. 1998;199:213–227. doi: 10.1023/A:1004327224729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk JL, et al. Revisiting the holy grail: Using plant functional traits to understand ecological processes. Biol. Rev. 2017;92:1156–1173. doi: 10.1111/brv.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kattge J, et al. TRY a global database of plant traits. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011;17:2905–2935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02451.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kattge J, et al. TRY plant trait database enhanced coverage and open access. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020;26:119–188. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CHAH. Australian Plant Census, Centre of Australian National Biodiversity Research. https://id.biodiversity.org.au/tree/51354547 (2020).

- 14.Kissling WD, et al. Towards global data products of Essential Biodiversity Variables on species traits. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1531–1540. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0667-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher RV, et al. Open Science principles for accelerating trait-based science across the Tree of Life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:294–303. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman, A. D. et al. Numbers of living species in Australia and the world. (Australian Government, 2009).

- 17.Hopper SD, Gioia P. The Southwest Australian Floristic Region: Evolution and conservation of a global hot spot of biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2004;35:623–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madin J, et al. An ontology for describing and synthesizing ecological observation data. Ecol. Inform. 2007;2:279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2007.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garnier E, et al. Towards a thesaurus of plant characteristics: An ecological contribution. J. Ecol. 2017;105:298–309. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams MA. M, P. & Attiwill. Role of Acacia spp. in nutrient balance and cycling in regenerating Eucalyptus regnans F. Muell. forests. I. Temporal changes in biomass and nutrient content. Aust. J. Bot. 1984;32:205–215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahrens CW, et al. Plant functional traits differ in adaptability and are predicted to be differentially affected by climate change. Ecol. Evo. 2019;10:232–248. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian National Botanic Gardens. The National Seed Bank. http://www.anbg.gov.au/gardens/living/seedbank/ (2018).

- 23.Angevin, T. Species richness and functional trait diversity response to land use in a temperate eucalypt woodland community. (La Trobe University, 2011).

- 24.Apgaua DMG, et al. Functional traits and water transport strategies in lowland tropical rainforest trees. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apgaua DMG, et al. Plant functional groups within a tropical forest exhibit different wood functional anatomy. Funct. Ecol. 2017;31:582–591. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashton DH. Studies of litter in Eucalyptus regnans forests. Aust. J. Bot. 1975;23:413–433. doi: 10.1071/BT9750413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashton DH. Phosphorus in forest ecosystems at Beenak, Victoria. Victoria. The J. Ecol. 1976;64:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Attiwill PM. Nutrient cycling in a Eucalyptus obliqua (L’Herit.) forest IV: Nutrient uptake and nutrient return. Aust. J. Bot. 1980;28:199–222. doi: 10.1071/BT9800199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barlow, B. A., Clifford, H. T., George, A. S. & McCusker, A. K. A. Flora of Australia. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/abrs/online-resources/flora/main/ (1981).

- 30.Bean AR. A revision of Baeckea (Myrtaceae) in eastern Australia, Malesia and south-east Asia. Telopea. 1997;7:245–268. doi: 10.7751/telopea19971018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell, L.C. Nutrient requirements for the establishment of native flora at Weipa. (Comalco Aluminium Ltd., 1985).

- 32.Bennett LT, Attiwill PM. The nutritional status of healthy and declining stands of Banksia integrifolia on the Yanakie Isthmus, Victoria. Aust. J. Bot. 1997;45:15–30. doi: 10.1071/BT96025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bevege, D. I. Biomass and nutrient distribution in indigenous forest ecosystems. vol. 6 20 (Queensland Department of Forestry, 1978).

- 34.Birk EM, Turner J. Response of flooded gum (E. grandis) to intensive cultural treatments: biomass and nutrient content of eucalypt plantations and native forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 1992;47:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(92)90262-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackman CJ, Brodribb TJ, Jordan GJ. Leaf hydraulic vulnerability is related to conduit dimensions and drought resistance across a diverse range of woody angiosperms. New Phytol. 2010;188:1113–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackman CJ, et al. Leaf hydraulic vulnerability to drought is linked to site water availability across a broad range of species and climates. Ann. Bot. 2014;114:435–440. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackman CJ, et al. The links between leaf hydraulic vulnerability to drought and key aspects of leaf venation and xylem anatomy among 26 Australian woody angiosperms from contrasting climates. Ann. Bot. 2018;122:59–67. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bloomfield KJ, et al. A continental-scale assessment of variability in leaf traits: Within species, across sites and between seasons. Funct. Ecol. 2018;32:1492–1506. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolza, E. Properties and uses of 175 timber species from Papua New Guinea and West Irian. (Victoria (Australia) CSIRO, Div. of Building Research, 1975).

- 40.Bragg JG, Westoby M. Leaf size and foraging for light in a sclerophyll woodland. Funct. Ecol. 2002;16:633–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brisbane Rainforest Action and Information Network. Trait measurements for Australian rainforest species. http://www.brisrain.org.au/ (2016).

- 42.Briggs AL, Morgan JW. Seed characteristics and soil surface patch type interact to affect germination of semi-arid woodland species. Plant Ecol. 2010;212:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s11258-010-9806-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brock, J. & Dunlop, A. Native plants of northern Australia. (Reed New Holland, 1993).

- 44.Brodribb TJ, Cochard H. Hydraulic failure defines the recovery and point of death in water-stressed conifers. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:575–584. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckton G, et al. Functional traits of lianas in an Australian lowland rainforest align with post-disturbance rather than dry season advantage. Austral Ecol. 2019;44:983–994. doi: 10.1111/aec.12764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burgess SSO, Dawson TE. Predicting the limits to tree height using statistical regressions of leaf traits. New Phytol. 2007;174:626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burrows GE. Comparative anatomy of the photosynthetic organs of 39 xeromorphic species from subhumid New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2001;162:411–430. doi: 10.1086/319579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler DW, Gleason SM, Davidson I, Onoda Y, Westoby M. Safety and streamlining of woody shoots in wind: an empirical study across 39 species in tropical Australia. New Phytol. 2011;193:137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CAB International. Forestry Compendium. http://www.cabi.org/fc/ (2009).

- 50.Caldwell E, Read J, Sanson GD. Which leaf mechanical traits correlate with insect herbivory among feeding guilds? Ann. Bot. 2015;117:349–361. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcv178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canham CA, Froend RH, Stock WD. Water stress vulnerability of four Banksia species in contrasting ecohydrological habitats on the Gnangara Mound. Western Australia. Plant Cell Envrion. 2009;32:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carpenter RJ. Cuticular morphology and aspects of the ecology and fossil history of North Queensland rainforest Proteaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1994;116:249–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1994.tb00434.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carpenter RJ, Hill RS, Jordan GJ. Leaf Cuticular Morphology Links Platanaceae and Proteaceae. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2005;166:843–855. doi: 10.1086/431806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catford JA, Downes BJ, Gippel CJ, Vesk PA. Flow regulation reduces native plant cover and facilitates exotic invasion in riparian wetlands. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011;48:432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01945.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catford JA, Morris WK, Vesk PA, Gippel CJ, Downes BJ. Species and environmental characteristics point to flow regulation and drought as drivers of riparian plant invasion. Divers. Distrib. 2014;20:1084–1096. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cernusak LA, Hutley LB, Beringer J, Tapper NJ. Stem and leaf gas exchange and their responses to fire in a north Australian tropical savanna. Plant Cell Envrion. 2006;29:632–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cernusak LA, Hutley LB, Beringer J, Holtum JAM, Turner BL. Photosynthetic physiology of eucalypts along a sub-continental rainfall gradient in northern Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011;151:1462–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandler GT, Crisp MD, Cayzer LW, Bayer RJ. Monograph of Gastrolobium (Fabaceae: Mirbelieae) Aust. Syst. Bot. 2002;15:619–739. doi: 10.1071/SB01010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chave J, et al. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol. Lett. 2009;12:351–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheal, D. Growth stages and tolerable fire intervals for Victoria’s native vegetation data sets. (Victorian Government Department of Sustainability; Environment Melbourne, 2010).

- 61.Cheesman AW, Duff H, Hill K, Cernusak LA, McInerney FA. Isotopic and morphologic proxies for reconstructing light environment and leaf function of fossil leaves: A modern calibration in the Daintree Rainforest, Australia. Am. J. Bot. 2020;107:1165–1176. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen, et al. Plants show more flesh in the tropics: Variation in fruit type along latitudinal and climatic gradients. Ecography. 2017;40:531–538. doi: 10.1111/ecog.02010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chinnock, R. J. Eremophila and allied genera: A monograph of the plant family Myoporaceae. (Rosenberg, 2007).

- 64.Choat B, Ball MC, Luly JG, Holtum JAM. Hydraulic architecture of deciduous and evergreen dry rainforest tree species from north-eastern Australia. Trees. 2005;19:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s00468-004-0392-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choat B, Ball MC, Luly JG, Donnelly CF, Holtum JAM. Seasonal patterns of leaf gas exchange and water relations in dry rain forest trees of contrasting leaf phenology. Tree Physiol. 2006;26:657–664. doi: 10.1093/treephys/26.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choat B, et al. Global convergence in the vulnerability of forests to drought. Nature. 2012;491:752–755. doi: 10.1038/nature11688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chudnoff, M. Tropical timbers of the world. 472 (US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1984).

- 68.The French agricultural research and international cooperation organization (CIRAD). Wood density data. http://www.cirad.fr/ (2009).

- 69.Clarke PJ, et al. A synthesis of postfire recovery traits of woody plants in Australian ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;534:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooper, W. & Cooper, W. T. Fruits of the Australian tropical rainforest. (Nokomis Editions, 2004).

- 71.Cooper, W. & Cooper, W. T. Australian rainforest fruits. 272 (CSIRO Publishing, 2013).

- 72.Cornwell, W. K. Causes and consequences of functional trait diversity: plant community assembly and leaf decomposition. (Stanford University, California, 2006).

- 73.Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research. EUCLID 2.0: Eucalypts of Australia. http://apps.lucidcentral.org/euclid/text/intro/index.html (2002).

- 74.Craven LA. A taxonomic revision of Calytrix Labill. (Myrtaceae) Brunonia. 1987;10:1–138. doi: 10.1071/BRU9870001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Craven LA, Lepschi BJ, Cowley KJ. Melaleuca (Myrtaceae) of Western Australia: Five new species, three new combinations, one new name and a new state record. Nuytsia. 2010;20:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Crisp MD, Cayzer L, Chandler GT, Cook LG. A monograph of Daviesia (Mirbelieae, Faboideae, Fabaceae) Phytotaxa. 2017;300:1–308. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.300.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cromer RN, Raupach M, Clarke ARP, Cameron JN. Eucalypt plantations in Australia - the potential for intensive production and utilization. Appita J. 1975;29:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cross, E. The characteristics of natives and invaders: A trait-based investigation into the theory of limiting similarity. (La Trobe University, 2009).

- 79.Crous KY, et al. Photosynthesis of temperate Eucalyptus globulus trees outside their native range has limited adjustment to elevated CO2 and climate warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013;19:3790–3807. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crous KY, Wujeska-Klause A, Jiang M, Medlyn BE, Ellsworth DS. Nitrogen and phosphorus retranslocation of leaves and stemwood in a mature Eucalyptus forest exposed to 5 years of elevated CO2. Front. Plant. Sci. 2019;10:art664. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cunningham SA, Summerhayes B, Westoby M. Evolutionary divergences in leaf structure and chemistry, comparing rainfall and soil nutrient gradients. Ecol. Monogr. 1999;69:569–588. doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0569:EDILSA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Curran TJ, Clarke PJ, Warwick NWM. Water relations of woody plants on contrasting soils during drought: does edaphic compensation account for dry rainforest distribution? Aust. J. Bot. 2009;57:629–639. doi: 10.1071/BT09128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Curtis EM, Leigh A, Rayburg S. Relationships among leaf traits of Australian arid zone plants: alternative modes of thermal protection. Aust. J. Bot. 2012;60:471–483. doi: 10.1071/BT11284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denton MD, Veneklaas EJ, Freimoser FM, Lambers H. Banksia species (Proteaceae) from severely phosphorus-impoverished soils exhibit extreme efficiency in the use and re-mobilization of phosphorus. Plant Cell Envrion. 2007;30:1557–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Desch, H. E. & Dinwoodie, J. M. Timber structure, properties, conversion and use. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1996).

- 86.de Tombeur F, et al. A shift from phenol to silica-based leaf defenses during long-term soil and ecosystem development. Ecol. Lett. 2021;24:984–995. doi: 10.1111/ele.13713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dong N, et al. Leaf nitrogen from first principles: field evidence for adaptive variation with climate. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:481–495. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-481-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dong N, et al. Components of leaf-trait variation along environmental gradients. New Phytol. 2020;228:82–94. doi: 10.1111/nph.16558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Du P, Arndt SK, Farrell C. Relationships between plant drought response, traits, and climate of origin for green roof plant selection. Ecol. Appl. 2018;28:1752–1761. doi: 10.1002/eap.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Du P, Arndt SK, Farrell C. Can the turgor loss point be used to assess drought response to select plants for green roofs in hot and dry climates? Plant Soil. 2019;441:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s11104-019-04133-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duan H, et al. Drought responses of two gymnosperm species with contrasting stomatal regulation strategies under elevated [CO2] and temperature. Tree Physiol. 2015;35:756–770. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Duncan RP, et al. Plant traits and extinction in urban areas: a meta-analysis of 11 cities. Glob. Ecol. Biog. 2011;20:509–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00633.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dwyer JM, Laughlin DC. Constraints on trait combinations explain climatic drivers of biodiversity: The importance of trait covariance in community assembly. Ecol. Lett. 2017;20:872–882. doi: 10.1111/ele.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dwyer JM, Mason R. Plant community responses to thinning in densely regenerating Acacia harpophylla forest. Restor. Ecol. 2018;26:97–105. doi: 10.1111/rec.12536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eamus D, Prichard H. A cost-benefit analysis of leaves of four Australian savanna species. Tree Physiol. 1998;18:537–545. doi: 10.1093/treephys/18.8-9.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eamus D, Myers B, Duff G, Williams D. Seasonal changes in photosynthesis of eight savanna tree species. Tree Physiol. 1999;19:665–671. doi: 10.1093/treephys/19.10.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Myers B, E. D, Duff G. A cost-benefit analysis of leaves of eight Australian savanna tree species of differing life-span. Photosynthetica. 1999;36:575–586. doi: 10.1023/A:1007048222329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Edwards C, Read J, Sanson GD. Characterising sclerophylly: some mechanical properties of leaves from heath and forest. Oecologia. 2000;123:158–167. doi: 10.1007/s004420051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Edwards C, Sanson GD, Aranwela N, Read J. Relationships between sclerophylly, leaf biomechanical properties and leaf anatomy in some Australian heath and forest species. Plant Biosyst. 2000;134:261–277. doi: 10.1080/11263500012331350445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schöenenberger J, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of fossil flowers using an angiosperm-wide data set: proof-of-concept and challenges ahead. Am. J. Bot. 2020;107:1433–1448. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Esperon-Rodriguez M, et al. Functional adaptations and trait plasticity of urban trees along a climatic gradient. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020;54:art126771. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Everingham SE, Offord CA, Sabot MEB, Moles AT. Time travelling seeds reveal that plant regeneration and growth traits are responding to climate change. Ecology. 2020;102:e03272. doi: 10.1002/ecy.3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Falster DS, Westoby M. Leaf size and angle vary widely across species: what consequences for light interception? New Phytol. 2003;158:509–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Falster DS, Westoby M. Alternative height strategies among 45 dicot rain forest species from tropical Queensland, Australia. J. Ecol. 2005;93:521–535. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2005.00992.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Falster DS, Westoby M. Tradeoffs between height growth rate, stem persistence and maximum height among plant species in a post-fire succession. Oikos. 2005;111:57–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13383.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Farrell C, Mitchell RE, Szota C, Rayner JP, Williams NSG. Green roofs for hot and dry climates: Interacting effects of plant water use, succulence and substrate. Ecol. Eng. 2012;49:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.08.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Farrell C, Szota C, Williams NSG, Arndt SK. High water users can be drought tolerant: using physiological traits for green roof plant selection. Plant Soil. 2013;372:177–193. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1725-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Farrell C, Szota C, Arndt SK. Does the turgor loss point characterize drought response in dryland plants? Plant Cell Envrion. 2017;40:1500–1511. doi: 10.1111/pce.12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feller MC. Biomass and nutrient distribution in two eucalypt forest ecosystems. Austral Ecol. 1980;5:309–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1980.tb01255.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Firn J, et al. Leaf nutrients, not specific leaf area, are consistent indicators of elevated nutrient inputs. Nature Ecol. Evo. 2019;3:400–406. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Flynn, J. H. & Holder, C. D. A guide to useful woods of the world. (Forest Products Society, 2001).

- 112.Fonseca CR, Overton JMC, Collins B, Westoby M. Shifts in trait-combinations along rainfall and phosphorus gradients. J. Ecol. 2000;88:964–977. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00506.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.McDonald PG, Fonseca CR, Overton JMC, Westoby M. Leaf-size divergence along rainfall and soil-nutrient gradients: is the method of size reduction common among clades? Funct. Ecol. 2003;17:50–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00698.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Forster PI. A taxonomic revision of Alyxia (Apocynaceae) in Australia. Aust. Syst. Bot. 1992;5:547–580. doi: 10.1071/SB9920547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Forster PI. New names and combinations in Marsdenia (Asclepiadaceae: Marsdenieae) from Asia and Malesia (excluding Papusia) Aust. Syst. Bot. 1995;8:691–701. doi: 10.1071/SB9950691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.French BJ, Prior LD, Williamson GJ, Bowman DMJS. Cause and effects of a megafire in sedge-heathland in the Tasmanian temperate wilderness. Aust. J. Bot. 2016;64:513–525. doi: 10.1071/BT16087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Froend RH, Drake PL. Defining phreatophyte response to reduced water availability: preliminary investigations on the use of xylem cavitation vulnerability in Banksia woodland species. Aust. J. Bot. 2006;54:173–179. doi: 10.1071/BT05081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Funk JL, Standish RJ, Stock WD, Valladares F. Plant functional traits of dominant native and invasive species in mediterranean-climate ecosystems. Ecology. 2016;97:75–83. doi: 10.1890/15-0974.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gallagher RV, et al. Invasiveness in introduced Australian acacias: The role of species traits and genome size. Divers. Distrib. 2011;17:884–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2011.00805.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gallagher RV, Leishman MR. A global analysis of trait variation and evolution in climbing plants. J. Biogeogr. 2012;39:1757–1771. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02773.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gardiner R, Shoo LP, Dwyer John. M. Look to seedling heights, rather than functional traits, to explain survival during extreme heat stress in the early stages of subtropical rainforest restoration. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019;56:2687–2697. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Geange SR, et al. Phenotypic plasticity and water availability: responses of alpine herb species along an elevation gradient. Clim. Change Responses. 2017;4:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40665-017-0029-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Geange SR, Holloway-Phillips M-M, Briceno VF, Nicotra AB. Aciphylla glacialis mortality, growth and frost resistance: a field warming experiment. Aust. J. Bot. 2020;67:599–609. doi: 10.1071/BT19034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ghannoum O, et al. Exposure to preindustrial, current and future atmospheric CO2 and temperature differentially affects growth and photosynthesis in Eucalyptus. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010;16:303–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02003.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gleason SM, Butler DW, Zieminska K, Waryszak P, Westoby M. Stem xylem conductivity is key to plant water balance across Australian angiosperm species. Funct. Ecol. 2012;26:343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.01962.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gleason SM, Butler DW, Waryszak P. Shifts in leaf and stem hydraulic traits across aridity gradients in eastern Australia. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2013;174:1292–1301. doi: 10.1086/673239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gleason SM, Blackman CJ, Cook AM, Laws CA, Westoby M. Whole-plant capacitance, embolism resistance and slow transpiration rates all contribute to longer desiccation times in woody angiosperms from arid and wet habitats. Tree Physiol. 2014;34:275–284. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gleason SM, et al. Vessel scaling in evergreen angiosperm leaves conforms with Murray’s law and area-filling assumptions: implications for plant size, leaf size and cold tolerance. New Phytol. 2018;218:1360–1370. doi: 10.1111/nph.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Goble-Garratt E, Bell D, Loneragan W. Floristic and leaf structure patterns along a shallow elevational gradient. Aust. J. Bot. 1981;29:329–347. doi: 10.1071/BT9810329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gosper CR. Fruit characteristics of invasive bitou bush, Chrysanthemoides monilifera (Asteraceae), and a comparison with co-occurring native plant species. Aust. J. Bot. 2004;52:223–230. doi: 10.1071/BT03046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gosper CR, Yates CJ, Prober SM. Changes in plant species and functional composition with time since fire in two mediterranean climate plant communities. J. Veg. Sci. 2012;23:1071–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01434.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gosper CR, Prober SM, Yates CJ. Estimating fire interval bounds using vital attributes: implications of uncertainty and among-population variability. Ecol. Appl. 2013;23:924–935. doi: 10.1890/12-0621.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gosper CR, Yates CJ, Prober SM. Floristic diversity in fire-sensitive eucalypt woodlands shows a “U”-shaped relationship with time since fire. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013;50:1187–1196. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gosper CR, et al. A conceptual model of vegetation dynamics for the unique obligate-seeder eucalypt woodlands of south-western Australia. Austral Ecol. 2018;43:681–695. doi: 10.1111/aec.12613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Clayton, W. D., Vorontsova, M. S., Harman, K. T. & Williamson, H. GrassBase - The online world grass flora. http://www.kew.org/data/grasses-db.html (2006).

- 136.Gray EF, et al. Leaf:wood allometry and functional traits together explain substantial growth rate variation in rainforest trees. AoB Plants. 2019;11:1–11. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Groom, P. K. & Lamont, B. B. Reproductive ecology of non-sprouting and re-sprouting Hakea species (Proteaceae) in southwestern Australia. In Gondwanan heritage (eds. S.D. Hopper M. Harvey, J. C. & George, A. S.) (Surrey Beatty, Chipping Norton, 1996).

- 138.Groom PK, Lamont BB. Fruit-seed relations in Hakea: serotinous species invest more dry matter in predispersal seed protection. Austral Ecol. 1997;22:352–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1997.tb00682.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Groom PK, Lamont BB. Phosphorus accumulation in Proteaceae seeds: A synthesis. Plant Soil. 2010;334:61–72. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0135-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Grootemaat S, Wright IJ, van Bodegom PM, Cornelissen JHC, Cornwell WK. Burn or rot: leaf traits explain why flammability and decomposability are decoupled across species. Funct. Ecol. 2015;29:1486–1497. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Grootemaat S, Wright IJ, van Bodegom PM, Cornelissen JHC, Shaw V. Bark traits, decomposition and flammability of Australian forest trees. Aust. J. Bot. 2017;65:327. doi: 10.1071/BT16258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Grootemaat S, Wright IJ, van Bodegom PM, Cornelissen JHC. Scaling up flammability from individual leaves to fuel beds. Oikos. 2017;126:1428–1438. doi: 10.1111/oik.03886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gross CL. The reproductive ecology of Canavalia rosea (Fabaceae) on Anak Krakatau. Indonesia. Aust. J. Bot. 1993;41:591–599. doi: 10.1071/BT9930591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gross CL. A comparison of the sexual systems in the trees from the Australian tropics with other tropical biomes–more monoecy but why? Am. J. Bot. 2005;92:907–919. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.6.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Grubb PJ, Metcalfe DJ. Adaptation and inertia in the Australian tropical lowland rain-forest flora: Contradictory trends in intergeneric and intrageneric comparisons of seed size in relation to light demand. Funct. Ecol. 1996;10:512–520. doi: 10.2307/2389944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Grubb PJ, et al. Monocot leaves are eaten less than dicot leaves in tropical lowland rain forests: Correlations with toughness and leaf presentation. Ann. Bot. 2008;101:1379–1389. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Guilherme Pereira C, Clode PL, Oliveira RS, Lambers H. Eudicots from severely phosphorus-impoverished environments preferentially allocate phosphorus to their mesophyll. New Phytol. 2018;218:959–973. doi: 10.1111/nph.15043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Guilherme Pereira C, et al. Trait convergence in photosynthetic nutrient-use efficiency along a 2-million year dune chronosequence in a global biodiversity hotspot. J. Ecol. 2019;107:2006–2023. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hacke UG, et al. Water transport in vesselless Angiosperms: Conducting efficiency and cavitation safety. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2007;168:1113–1126. doi: 10.1086/520724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hall TJ. The nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations of some pasture species in the Dichanthium-Eulalia Grasslands of North-West Queensland. Rangeland J. 1981;3:67–73. doi: 10.1071/RJ9810067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Harrison MT, Edwards EJ, Farquhar GD, Nicotra AB, Evans JR. Nitrogen in cell walls of sclerophyllous leaves accounts for little of the variation in photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency. Plant Cell Envrion. 2009;32:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hassiotou F, Evans JR, Ludwig M, Veneklaas EJ. Stomatal crypts may facilitate diffusion of CO2 to adaxial mesophyll cells in thick sclerophylls. Plant Cell Envrion. 2009;32:1596–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Hatch, A. B. Influence of plant litter on the Jarrah forest soils of the Dwellingup region. West. Aust. For. Timber Bur. Leaflet18 (1955).

- 154.Hayes P, Turner BL, Lambers H, Laliberte E. Foliar nutrient concentrations and resorption efficiency in plants of contrasting nutrient-acquisition strategies along a 2-million-year dune chronosequence. J. Ecol. 2013;102:396–410. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hayes PE, Clode PL, Oliveira RS, Lambers H. Proteaceae from phosphorus-impoverished habitats preferentially allocate phosphorus to photosynthetic cells: an adaptation improving phosphorus-use efficiency. Plant Cell Envrion. 2018;41:605–619. doi: 10.1111/pce.13124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Henery ML, Westoby M. Seed mass and seed nutrient content as predictors of seed output variation between species. Oikos. 2001;92:479–490. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hocking PJ. The nutrition of fruits of two proteaceous shrubs, Grevillea wilsonii and Hakea undulata, from south-western Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 1982;30:219–230. doi: 10.1071/BT9820219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Hocking PJ. Mineral nutrient composition of leaves and fruits of selected species of Grevillea from southwestern Australia, with special reference to Grevillea leucopteris Meissn. Aust. J. Bot. 1986;34:155–164. doi: 10.1071/BT9860155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Hong, L. T. et al. Plant resources of south east Asia: Timber trees. World biodiversity Database CD rom series (Springer-Verlag Berlin; Heidelberg GmbH; Co. KG, 1999).

- 160.Hopmans P, Stewart HTL, Flinn DW. Impacts of harvesting on nutrients in a eucalypt ecosystem in southeastern Australia. For. Ecol. Manage. 1993;59:29–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(93)90069-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Huang G, Rymer PD, Duan H, Smith RA, Tissue DT. Elevated temperature is more effective than elevated CO2 in exposing genotypic variation in Telopea speciosissima growth plasticity: implications for woody plant populations under climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015;21:3800–3813. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hyland, B. P. M., Whiffin, T., Christophel, D., Gray, B. & Elick, R. W. Australian tropical rain forest plants trees, shrubs and vines. (CSIRO Publishing, 2003).

- 163.World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). The wood density database. http://www.worldagroforestry.org/output/wood-density-database (2009).

- 164.Ilic, J., Boland, D., McDonald, M., G., D. & Blakemore, P. Woody density phase 1 - State of knowledge. National Carbon Accounting System. Technical Report 18. (Australian Greenhouse Office, Canberra, Australia, 2000).

- 165.Islam M, Turner DW, Adams MA. Phosphorus availability and the growth, mineral composition and nutritive value of ephemeral forbs and associated perennials from the Pilbara, Western Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1999;39:149–159. doi: 10.1071/EA98133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Islam M, Adams MA. Mineral content and nutritive value of native grasses and the response to added phosphorus in a Pilbara rangeland. Trop. Grassl. 1999;33:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Jordan GJ. An investigation of long-distance dispersal based on species native to both Tasmania and New Zealand. Aust. J. Bot. 2001;49:333–340. doi: 10.1071/BT00024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Jordan GJ, Weston PH, Carpenter RJ, Dillon RA, Brodribb TJ. The evolutionary relations of sunken, covered, and encrypted stomata to dry habitats in Proteaceae. Am. J. Bot. 2008;95:521–530. doi: 10.3732/ajb.2007333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Jordan GJ, Carpenter RJ, Koutoulis A, Price A, Brodribb TJ. Environmental adaptation in stomatal size independent of the effects of genome size. New Phytol. 2015;205:608–617. doi: 10.1111/nph.13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Jordan GJ, et al. Links between environment and stomatal size through evolutionary time in Proteaceae. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2020;287:20192876. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Jurado E. Diaspore weight, dispersal, growth form and perenniality of central Australian plants. J. Ecol. 1991;79:811–828. doi: 10.2307/2260669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Jurado E, Westoby M. Germination biology of selected central Australian plants. Austral Ecol. 1992;17:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1992.tb00816.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Kanowski, J. Ecological determinants of the distribution and abundance of the folivorous marsupials endemic to the rainforests of the Atherton uplands, north Queensland. (James Cook University, Townsville, 1999).

- 174.Keighery G. Taxonomy of the Calytrix ecalycata complex (Myrtaceae) Nuytsia. 2004;15:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 175.Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Seed Information Database (SID) and Seed Bank Database. http://data.kew.org/sid/ (2019).

- 176.Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Seed protein data from Seed Information Database (SID) and Seed Bank Database. http://data.kew.org/sid/ (2019).

- 177.Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Oil content data from Seed Information Database (SID) and Seed Bank Database. http://data.kew.org/sid/ (2019).

- 178.Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Seed dispersal data from the Seed Information Database (SID) and Seed Bank Database. http://data.kew.org/sid/ (2019).

- 179.Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Germination data from the Seed Information Database (SID) and Seed Bank Database. http://data.kew.org/sid/ (2019).

- 180.Knox KJE, Clarke PJ. Fire severity and nutrient availability do not constrain resprouting in forest shrubs. Plant Ecol. 2011;212:1967–1978. doi: 10.1007/s11258-011-9956-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Körner C, Cochrane PM. Stomatal responses and water relations of Eucalyptus pauciflora in summer along an elevational gradient. Oecologia. 1985;66:443–455. doi: 10.1007/BF00378313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Kooyman R, Rossetto M, Cornwell W, Westoby M. Phylogenetic tests of community assembly across regional to continental scales in tropical and subtropical rain forests. Glob. Ecol. Biog. 2011;20:707–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00641.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Kotowska MM, Wright IJ, Westoby M. Parenchyma abundance in wood of evergreen trees varies independently of nutrients. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020;11:art86. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Kuo J, Hocking P, Pate J. Nutrient reserves in seeds of selected Proteaceous species from South-western Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 1982;30:231–249. doi: 10.1071/BT9820231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Laliberté E, et al. Experimental assessment of nutrient limitation along a 2-million-year dune chronosequence in the south-western Australia biodiversity hotspot. J. Ecol. 2012;100:631–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.01962.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Lambert, M. J. Sulphur relationships of native and exotic tree species. (Macquarie University, Sydney, 1979).

- 187.Lamont BB, Groom PK, Cowling RM. High leaf mass per area of related species assemblages may reflect low rainfall and carbon isotope discrimination rather than low phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations. Funct. Ecol. 2002;16:403–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]