Abstract

Introduction

In phase III trials in adolescents and children with atopic dermatitis (AD), dupilumab significantly decreased global disease severity. However, the effects of dupilumab on the extent and signs of AD across different anatomical regions were not reported. Here we characterize the efficacy of dupilumab in improving the extent and signs of AD across four different anatomical regions in children and adolescents.

Methods

A post hoc subset analysis was performed using data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international multicenter, phase III trials of dupilumab therapy in adolescents aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD and children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with severe AD. Endpoints included mean percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) signs (erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, lichenification) and extent of AD (measured by percentage of body surface area [% BSA] involvement) from baseline to week 16 across four anatomical regions (head and neck, trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities).

Results

Dupilumab improved both the extent and severity of AD signs across the four anatomical regions. Improvements were shown to be similar across the four anatomical regions for % BSA involvement and for reduction in EASI signs. Improvements in all signs were seen early, within the first 4 weeks of treatment, and were sustained through week 16, across all regions.

Conclusions

In pediatric patients 6 years of age and older, treatment with dupilumab resulted in rapid and consistent improvement in the extent and signs of AD across all anatomical regions.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers

LIBERTY AD ADOL (NCT03054428) and LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914).

Does dupilumab provide improvement in atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions in children and adolescents? (MP4 48,385 kb)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00568-y.

Keywords: Atopic eczema, Dupilumab, Pediatric dermatology, Patients, Immunology, Cytokines, Contact dermatitis, Anatomical regions, Facial erythema, Signs

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| In phase III trials in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and children 6 years of age and older with severe AD, treatment with dupilumab resulted in a substantial reduction in disease severity. |

| In adults, improvements were shown to be similar across anatomical regions. |

| This study aimed to characterize the efficacy of dupilumab in improving the extent and signs of AD across four different anatomical regions in children and adolescents. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This study reports the effect of dupilumab across different anatomical regions in pediatric patients 6 years of age and older. |

| Dupilumab demonstrated rapid and consistent improvement for 16 weeks in the extent and signs of atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14779038.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by distinct distribution patterns in different age groups, but with some interpatient variation with regard to the most severely affected sites [1–3]. In some cases, this represents a secondary condition. For example, the face, feet, and hands are common sites for exacerbation by irritants or allergic contact dermatitis [1, 2, 4], while Malassezia colonization may trigger exacerbation on the face and neck, especially in adolescents [5]. Sun-exposed sites can also be exacerbated by photosensitivity [6, 7].

Some anatomical regions may have a greater impact on quality of life than others [8, 9]. The face and hands, for example, are highly visible, aesthetically important sites. Palmar involvement can interfere with function and plantar involvement with ambulation [9, 10]. Affected skin folds can be painful.

The anatomical location of AD can also impact treatment options. Although topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the mainstay treatment for AD, prolonged use on the face can trigger rosacea and perioral dermatitis, while use on skin folds carries a higher risk of striae [11]. Steroid withdrawal can result in rebound erythema on the facial regions [12]. Skin atrophy can occur, especially on the eyelids and intertriginous areas [13, 14]. Thicker skin on palms and soles may require use of higher-potency TCS for optimal response, with increased risk of atrophy and rebound effects [2, 11]. The tissue distribution and response to systemic medication, including biologics, may be different across anatomical areas owing to regional differences in skin blood flow [15].

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that blocks the shared receptor component for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, inhibiting signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13 [16, 17], which are key drivers of type 2-mediated inflammation in multiple diseases [16, 18].

The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and evaluation of percentage body surface area (BSA) affected permit assessment of AD clinical severity by defined anatomical region based on four signs (erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification) [19, 20]. Previous analyses of data from phase III trials in adults with moderate-to-severe AD showed that significant disease severity improvement from dupilumab was similar in all anatomical regions as assessed by EASI [21]. Improvements were seen as early as week 4, and were maintained up to week 52 [21].

Phase III trials in 251 adolescents aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD [22] and in 367 children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with severe AD [23] treated with dupilumab demonstrated substantial improvements in global disease severity and BSA affected with an acceptable safety profile. However, efficacy across different anatomical regions was not reported.

The objective of this study was to assess the efficacy of dupilumab in improving the extent and severity of AD signs (erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, lichenification) in four anatomical regions (head and neck, trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities) in pediatric patients aged 6 years and older.

Methods

We performed a post hoc analysis of data from two randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled, global, phase III trials of dupilumab: LIBERTY AD ADOL (NCT03054428) [22] and LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914) [23]. The full study designs and patient populations of the trials have been previously reported [22, 23].

Briefly, LIBERTY AD ADOL included adolescent patients aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled by topical medications or for whom topical treatment was medically inadvisable [22]. Patients were required to have minimum overall BSA of AD involvement at screening and baseline of 10%; there was no requirement for minimum BSA of involvement in a specific anatomical region. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (q4w; with a loading dose of 600 mg), or dupilumab every 2 weeks (q2w; 200 mg with a loading dose of 400 mg if body weight < 60 kg, or 300 mg with a loading dose of 600 mg if body weight ≥ 60 kg). Systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants, systemic corticosteroids or TCS, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical crisaborole were only allowed for use as rescue treatment for patients with intolerable AD symptoms at the discretion of the investigator. Assessments, including patient-reported outcomes and investigator-performed assessments, to evaluate treatment effect were based on overall AD disease severity without any further prespecified analysis to assess efficacy individually in different anatomical regions.

LIBERTY AD PEDS included children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with severe AD inadequately controlled by topical medications [23]. Minimum overall BSA of AD involvement at screening and baseline of 15% was required, without any requirement for minimum BSA of involvement in a specific anatomical region. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, dupilumab 300 mg q4w (loading dose of 600 mg) or dupilumab q2w (100 mg with a loading dose of 200 mg if body weight < 30 kg, or 200 mg with a loading dose of 400 mg if body weight ≥ 30 kg). All patients received medium-potency TCS starting 2 weeks before baseline, with a possibility to escalate to high-potency TCS as rescue treatment; the use of very high-potency TCS was prohibited. On the basis of investigator discretion, low-potency TCS were allowed to be used once daily on areas of thin skin (face, neck, intertriginous and genital areas, and areas of skin atrophy, etc.) or for areas where continued treatment with medium-potency TCS was considered unsafe. Use of topical calcineurin inhibitors was prohibited. Assessments, including patient-reported outcomes and investigator-performed assessments, to evaluate treatment effects were based on overall AD disease severity without any further prespecified analysis to assess efficacy individually in different anatomical regions.

Both trials were conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at all study sites. For all patients, at least one parent or legal guardian provided written informed assent, and patients provided written informed assent before study participation.

Endpoints

Least squares (LS) mean percentage change in EASI from baseline to week 16 by visit and the median percentage change in BSA affected from baseline to week 16 by visit were evaluated in the four anatomical regions (head and neck, trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities). As a result of the non-normal distribution of % BSA data and to reduce the impact of outliers, an analysis using median percentage change (rather than mean percentage change) from baseline was performed. The median difference and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated with the Hodges–Lehmann method. The median estimates and 95% CI were calculated with the quantile regression method.

BSA was calculated using the rule of nines and combined in the four regions as follows: head and neck (0–9%), trunk (0–36%), upper right plus upper left extremities (0–18%), and lower right plus lower left extremities plus genitalia (0–37%).

LS mean percentage change from baseline in EASI signs (erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification) was evaluated in the four anatomical regions. EASI sign scores were calculated as a composite of the intensity (0–3) and extent of involvement (0–6). For each region, the intensity of signs (erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, lichenification) was summated (0–12) and then multiplied by extent of involvement (0–6). These scores were presented as both weighted and nonweighted scores. For weighting, the % BSA assigned to each anatomical region in the EASI score calculation was used [24]. For children aged < 8 years, the % BSA weighting coefficient used was 0.2 for head and neck, 0.3 for trunk, 0.2 for upper extremities, and 0.3 for lower extremities. For children aged ≥ 8 years, the % BSA weighting coefficient used was 0.1 for head and neck, 0.3 for trunk, 0.2 upper extremities, and 0.4 for lower extremities.

Analysis

Only data from LIBERTY AD ADOL and LIBERTY AD PEDS for patients receiving dupilumab doses approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency (dupilumab 300 mg q4w for body weight < 30 kg; 300 mg q4w for body weight ≥ 30 kg; 200 mg q2w for body weight ≥ 30 to < 60 kg or 300 mg q2w for body weight ≥ 60 kg) or corresponding placebo were included in this analysis. All patients randomized to the approved dupilumab doses were included in efficacy analyses.

Endpoints were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with baseline measurement as covariate and the treatment, randomization strata (baseline disease severity [Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) = 3 vs. IGA = 4] for LIBERTY AD ADOL only), and geographical region (North America vs. Europe for LIBERTY AD PEDS only) as fixed factors. Values after rescue medication use were set to missing. For LS mean percentage change in EASI, EASI signs, and median percentage change in BSA affected, missing values were imputed using the last observation carried forward method. p < 0.05 (two-sided tests) was regarded as significant. Statistical Analysis Software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

In the LIBERTY AD ADOL study, 251 patients were randomized (mean age 14.5 years; 59% male) [22], and in LIBERTY AD PEDS, 367 patients were randomized (mean age approximately 8.5 years; 49.9% male) [23]. A total of 167 patients from LIBERTY AD ADOL and 304 patients from LIBERTY AD PEDS were included in this analysis (patients who received approved dupilumab doses, and body-weight-matched placebo control patients).

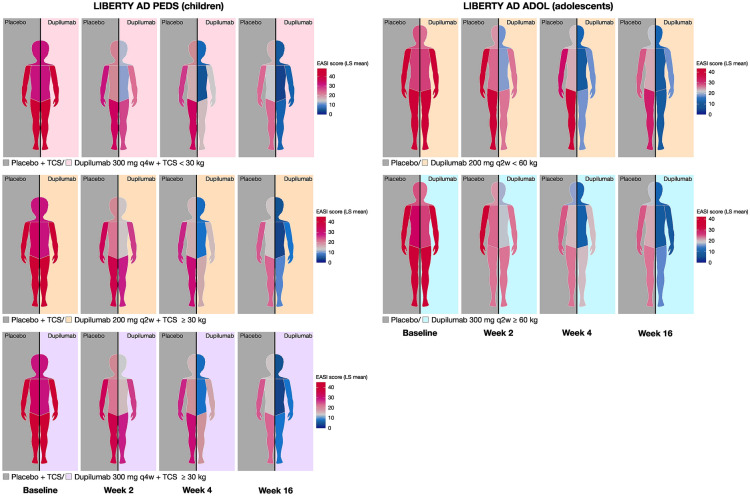

EASI scores and component scores were balanced at baseline between the treatment groups in each individual study (Tables 1 and 2). The overall EASI score as well as the regional scores were comparable between the dupilumab and placebo arms across both studies at baseline. On comparing the EASI regional scores at baseline, there was a trend towards higher disease severity on the upper and lower extremities compared with the head and neck, and trunk regions (43.5 and 45.4 vs. 28.0 and 29.4, respectively, in LIBERTY AD PEDS; 40.1 and 38.6 vs. 27.7 and 30.5, respectively, in LIBERTY AD ADOL) (Fig. 1; Table S1 in the Supplementary Material).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics: EASI regional scores (weighted for % BSA) and % BSA affected

| Score range | LIBERTY AD PEDS, aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years | LIBERTY AD ADOL, aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 304) |

Placebo + TCS < 30 kg (n = 61) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS < 30 kg (n = 61) |

Placebo + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 62) |

Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 59) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 61) |

Overall (n = 167) |

Placebo < 60 kg (n = 43) |

Dupilumab 200 mg q2w < 60 kg (n = 43) |

Placebo ≥ 60 kg (n = 42) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q2w ≥ 60 kg (n = 39) |

||

| EASI score, mean (SD) | 0–72 | 37.9 (12.1) | 38.9 (12.6) | 36.9 (12.4) | 39.0 (11.5) | 37.1 (11.8) | 37.8 (12.6) | 35.4 (13.9) | 35.0 (15.5) | 36.1 (14.6) | 36.0 (12.4) | 34.4 (13.1) |

| EASI regional score, weighted for % BSAa | ||||||||||||

| Head and neck, mean (SD) |

0–14.4b or 0–7.2c |

3.8 (2.8) | 5.3 (3.4) | 4.8 (3.3) | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.9) | 2.9 (2.1) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.5) |

| Trunk, mean (SD) | 0–21.6 | 8.8 (5.3) | 9.0 (5.4) | 8.7 (5.1) | 9.6 (4.9) | 8.2 (5.7) | 8.5 (5.4) | 9.2 (5.4) | 9.0 (6.0) | 8.8 (5.7) | 9.7 (5.2) | 9.1 (4.6) |

| Upper extremities, mean (SD) | 0–14.4 | 8.7 (2.8) | 8.8 (2.8) | 8.3 (2.9) | 9.0 (2.8) | 8.4 (2.7) | 9.0 (2.6) | 8.0 (3.1) | 8.1 (3.4) | 7.7 (3.1) | 8.3 (2.9) | 8.0 (3.2) |

| Lower extremities, mean (SD) |

0–21.6b or 0–28.8c |

16.6 (5.7) | 15.8 (5.0) | 15.0 (5.5) | 17.5 (5.6) | 17.5 (5.7) | 17.4 (6.2) | 15.4 (6.8) | 14.9 (7.1) | 16.8 (6.6) | 15.4 (6.9) | 14.5 (6.7) |

| % BSA affected, median (Q1–Q3) |

54.0 (38.5–76.3) |

60.0 (47.0–80.0) |

50.0 (36.0–78.0) |

57.3 (37.7–79.0) |

48.0 (40.5–69.5) |

53.0 (34.0–73.0) |

53.0 (39.0–73.5) |

52.0 (38.0–76.0) |

54.5 (38.0–77.5) |

52.5 (38.0–79.0) |

53.0 (40.0–68.5) |

|

| Head and neck, median (Q1–Q3) | (0–9) |

5.0 (3.0–7.0) |

6.0 (4.0–9.0) |

5.5 (4.0–8.0) |

4.0 (3.0–6.5) |

4.5 (3.0–6.0) |

5.0 (2.0–7.0) |

5.0 (3.1–6.5) |

6.0 (3.1–8.0) |

5.0 (3.5–6.5) |

4.5 (2.5–6.3) |

4.8 (4.0–6.0) |

| Torso, median (Q1–Q3) | (0–36) |

16.0 (8.0–27.0) |

18.0 (12.0–29.0) |

16.0 (8.0–25.0) |

18.0 (10.0–30.0) |

12.0 (7.0–25.0) |

15.0 (6.0–25.0) |

18.0 (10.0–27.9) |

16.0 (12.0–28.0) |

18.0 (8.0–27.0) |

19.5 (9.0–30.0) |

18.0 (12.0–27.0) |

| Upper extremities, median (Q1–Q3) | (0–18) |

11.5 (9.0–15.0) |

12.0 (9.8–14.6) |

10.0 (8.0–13.0) |

12.0 (9.0–15.0) |

10.0 (8.0–14.0) |

10.0 (9.3–15.4) |

12.0 (8.0–16.0) |

12.0 (8.0–16.0) |

12.0 (8.0–16.0) |

11.5 (8.0–16.0) |

12.0 (8.0–14.0) |

| Lower extremities, median (Q1–Q3) | (0–37) |

23.2 (15.3–30.0) |

24.0 (18.0–30.0) |

23.0 (12.0–28.0) |

22.5 (14.0–30.0) |

22.0 (14.0–30.0) |

20.0 (14.4–31.0) |

20.0 (13.0–31.0) |

19.8 (12.0–32.0) |

22.0 (14.0–32.0) |

19.0 (13.0–32.0) |

19.0 (14.0–28.0) |

BSA body surface area, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, Q1–Q3 interquartile range, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SD standard deviation, TCS topical corticosteroid

aFor children aged < 8 years, % BSA weighting coefficient is 0.2 for head and neck, 0.3 for trunk, 0.2 for upper extremities, and 0.3 for lower extremities. For children aged ≥ 8 years, % BSA weighting coefficient is 0.1 for head and neck, 0.3 for trunk, 0.2 upper extremities, and 0.4 for lower extremities

bFor children aged < 8 years in LIBERTY AD PEDS

cFor children aged ≥ 8 years and adolescents in LIBERTY AD ADOL

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics: EASI erythema, infiltration/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification scores

| Score range | LIBERTY AD PEDS, aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years | LIBERTY AD ADOL, aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 304) |

Placebo + TCS < 30 kg (n = 61) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS < 30 kg (n = 61) |

Placebo + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 62) |

Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 59) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS ≥ 30 kg (n = 61) |

Overall (n = 167) |

Placebo < 60 kg (n = 43) |

Dupilumab 200 mg q2w < 60 kg (n = 43) |

Placebo ≥ 60 kg (n = 42) |

Dupilumab 300 mg

q2w ≥ 60 kg (n = 39) |

||

| EASI erythema score | ||||||||||||

| Head and neck, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 8.0 (4.5) | 8.8 (5.0) | 8.4 (4.6) | 7.9 (4.3) | 7.6 (3.8) | 7.4 (4.8) | 8.2 (4.4) | 8.6 (4.3) | 7.8 (4.5) | 8.0 (5.1) | 8.2 (3.7) |

| Trunk, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 7.8 (4.6) | 7.7 (4.7) | 7.6 (4.6) | 8.4 (4.4) | 7.4 (4.7) | 7.9 (4.9) | 8.2 (4.8) | 7.7 (5.1) | 7.8 (5.1) | 8.7 (4.6) | 8.6 (4.2) |

| Upper extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 10.9 (3.8) | 10.9 (3.7) | 10.2 (4.0) | 11.4 (3.9) | 10.5 (3.5) | 11.5 (3.8) | 10.1 (4.2) | 10.3 (4.2) | 9.7 (4.4) | 10.5 (3.9) | 9.9 (4.2) |

| Lower extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 11.3 (3.9) | 12.0 (3.7) | 10.8 (3.8) | 11.2 (4.0) | 11.4 (3.9) | 11.3 (4.0) | 9.7 (4.5) | 9.4 (4.7) | 10.5 (4.6) | 9.4 (4.5) | 9.2 (4.1) |

| EASI infiltration/papulation score | ||||||||||||

| Head and neck, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 6.9 (4.3) | 7.3 (4.48) | 7.5 (4.3) | 6.6 (4.2) | 6.5 (4.1) | 6.5 (4.5) | 7.1 (4.3) | 7.6 (4.2) | 7.1 (4.4) | 6.5 (4.5) | 7.3 (4.1) |

| Trunk, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 7.7 (4.8) | 8.0 (4.76) | 7.6 (4.6) | 8.5 (4.5) | 7.1 (5.2) | 7.4 (4.8) | 7.9 (4.6) | 8.0 (5.1) | 7.5 (4.9) | 8.2 (4.4) | 8.1 (4.1) |

| Upper extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 10.9 (3.7) | 11.1 (3.9) | 10.3 (3.7) | 11.4 (3.9) | 10.4 (3.7) | 11.3 (3.4) | 10.1 (4.1) | 10.5 (4.5) | 9.4 (3.8) | 10.3 (3.9) | 10.1 (4.2) |

| Lower extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 11.4 (3.9) | 11.9 (4.0) | 11.1 (3.9) | 11.1 (4.0) | 11.3 (3.7) | 11.5 (4.0) | 9.9 (4.5) | 9.9 (5.0) | 10.4 (4.2) | 9.9 (4.6) | 9.2 (4.5) |

| EASI excoriation score | ||||||||||||

| Head and neck, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 6.1 (4.5) | 6.6 (4.8) | 6.7 (4.7) | 6.1 (4.5) | 5.3 (3.7) | 5.7 (4.5) | 6.0 (4.7) | 5.9 (4.8) | 6.0 (5.0) | 6.0 (4.8) | 6.0 (4.5) |

| Trunk, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 6.7 (4.8) | 6.7 (4.9) | 6.7 (4.6) | 7.3 (4.8) | 6.5 (5.2) | 6.5 (4.6) | 7.3 (5.0) | 7.3 (5.4) | 7.1 (5.4) | 7.9 (4.7) | 7.0 (4.6) |

| Upper extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 10.6 (4.1) | 10.7 (4.3) | 10.3 (4.1) | 10.8 (4.2) | 10.1 (4.2) | 11.1 (3.9) | 9.9 (4.3) | 10.2 (4.6) | 9.3 (4.3) | 10.4 (3.7) | 9.9 (4.5) |

| Lower extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 11.2 (4.0) | 11.7 (3.8) | 10.8 (4.1) | 11.0 (3.8) | 11.1 (4.1) | 11.1 (4.3) | 9.5 (4.8) | 8.6 (5.2) | 10.5 (4.4) | 9.9 (4.6) | 9.0 (5.0) |

| EASI lichenification score | ||||||||||||

| Head and neck, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 7.0 (4.6) | 7.4 (4.5) | 7.8 (4.9) | 6.7 (4.3) | 6.8 (4.4) | 6.2 (4.9) | 6.5 (4.2) | 7.1 (4.7) | 6.1 (4.3) | 6.0 (4.2) | 6.6 (3.7) |

| Trunk, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 7.1 (4.7) | 7.6 (4.6) | 7.2 (4.5) | 7.8 (4.9) | 6.5 (4.8) | 6.5 (5.0) | 7.1 (4.9) | 7.2 (5.4) | 7.1 (4.7) | 7.4 (5.5) | 6.7 (4.2) |

| Upper extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 11.1 (3.8) | 11.3 (3.9) | 10.7 (3.9) | 11.5 (3.8) | 10.9 (3.3) | 11.3 (3.8) | 10.0 (4.5) | 9.8 (5.0) | 10.0 (4.4) | 10.3 (4.5) | 10.0 (4.2) |

| Lower extremities, mean (SD) | 0–18 | 11.6 (4.1) | 12.6 (3.7) | 11.2 (4.3) | 11.8 (4.1) | 11.1 (3.7) | 11.1 (4.4) | 9.5 (4.8) | 9.4 (5.1) | 10.6 (4.6) | 9.3 (4.9) | 8.7 (4.3) |

EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SD standard deviation, TCS topical corticosteroid

Fig. 1.

Analysis of value in EASI regional scoresa (from baseline to week 16)b. aEASI regional scores nonweighted for % BSA. bFor graphical purposes, figures have been constructed to represent the right side of the body being treated with placebo and the left side being treated with dupilumab. In patients receiving dupilumab, similar responses were achieved on both sides of the body. BSA body surface area, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, LS least squares, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroid

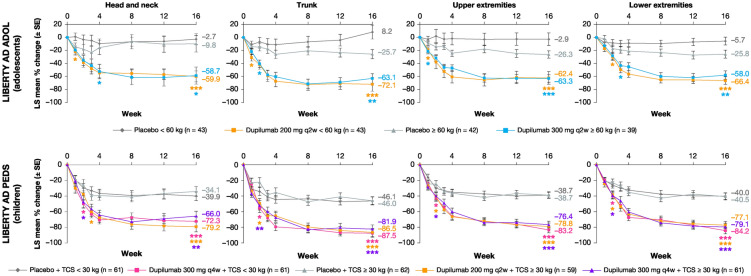

Overall, all dupilumab regimens vs. the corresponding placebo regimen significantly improved EASI score across the four anatomical regions during 16 weeks of treatment (Figs. 1 and 2). In LIBERTY AD PEDS, a significant improvement was seen with dupilumab as early as week 1 in head and neck, trunk, and upper extremities scores, and as early as week 2 in lower extremities scores, with improvements in all EASI scores and anatomical regions sustained through week 16. In LIBERTY AD ADOL, a significant improvement vs. placebo was seen in all four anatomical regions as early as week 2, with improvements sustained through week 16.

Fig. 2.

LS mean percentage change in EASI regional scorea from baseline to week 16 by visit in four anatomical regions. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001; vs. corresponding placebo. aEASI regional scores weighted for % BSA. BSA body surface area, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, LS least squares, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SE standard error, TCS topical corticosteroid

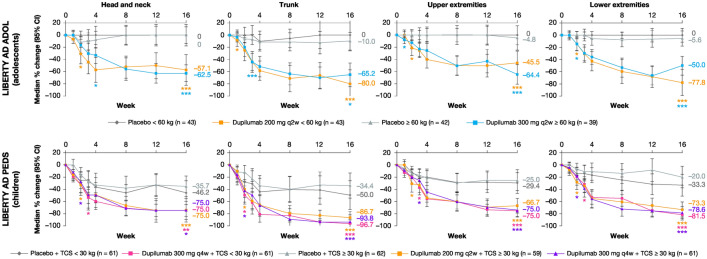

Median percentage change in BSA affected from baseline to week 16 by visit in four anatomical regions is shown in Fig. 3. Overall, all dupilumab regimens vs. the corresponding placebo regimen significantly improved the extent of lesions as measured by improvements in % BSA across the four anatomical regions during 16 weeks of treatment.

Fig. 3.

Median percentage change in BSA affecteda from baseline to week 16 by visit in four anatomical regions. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001; vs. corresponding placebo. aThe median difference and 95% CI were calculated with the Hodges–Lehmann method. The median estimates and 95% CI were calculated with the quantile regression method. BSA body surface area, CI confidence interval, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroid

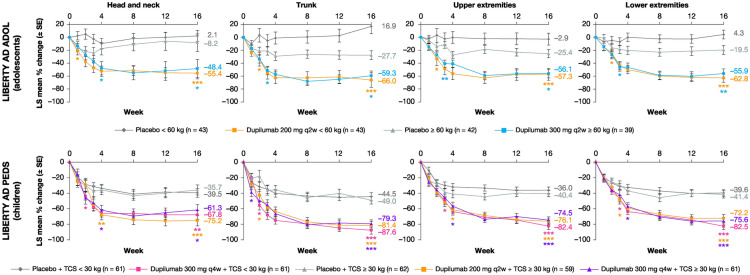

Overall, all dupilumab regimens vs. the corresponding placebo regimens significantly improved EASI signs score across the four anatomical regions during 16 weeks of treatment, including lichenification, the AD sign most resistant to treatment [25] (Fig. 4; Figs. S1–S3 in the Supplementary Material). Although statistical significance for lichenification was not seen for the dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS ≥ 30 kg for the head and neck region at week 16, the dupilumab treatment showed numerically higher improvement as compared with placebo. Moreover, a statistically significant difference was seen at week 12. Regarding erythema (Fig. 4) in LIBERTY AD ADOL, a significant improvement in head and neck with dupilumab was seen as early as week 1, and in trunk, lower extremities, and upper extremities as early as week 2. In LIBERTY AD PEDS a significant improvement vs. placebo in head and neck and trunk was seen with dupilumab as early as week 2, and in the upper and lower extremities as early as week 3. Regarding infiltration/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification (Figs. S1, S2, and S3, respectively, in the Supplementary Material), significant improvements in all measures assessed vs. the corresponding placebo groups were seen with both dupilumab regimens within the first 4 weeks of treatment.

Fig. 4.

LS mean percentage change from baseline in EASI sign scorea (erythema) in four anatomical regions. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001; vs. corresponding placebo. aEASI sign score is calculated as composite of the intensity (0–3) and extent of involvement (0–6). EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, LS least squares, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SE standard error, TCS topical corticosteroid

Discussion

In this analysis of data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trials in adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD and children with severe AD, dupilumab rapidly improved the extent and severity of AD signs across four anatomical regions (head and neck, trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities). The disease burden at baseline was comparable across treatment groups. However, the baseline disease burden was numerically higher in upper and lower extremities compared with trunk and head and neck. This is consistent with flexural areas, wrists, ankles, hands and feet, being favored sites for AD [26]. Moreover, this pattern was seen consistently in younger children as well as adolescents. This was expected, as childhood (seen in pre-pubertal children) and adult forms (seen in post-pubertal children and adults) have been reported to have similar distributions as opposed to infantile forms, which tend to favor the face, scalp, and trunk [27]. Dupilumab reduced the extent of AD across the four anatomical regions (measured by % BSA) and improved erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification (measured by EASI).

The dupilumab dosing regimens assessed in children and adolescents yielded similar EASI and % BSA improvements across all four anatomical regions, reflecting comparable results seen in adults with moderate-to-severe AD who received dupilumab with or without TCS [21]. Signs of inflammation mimicking AD can suggest another etiology based on their distribution, such as superimposed contact dermatitis involving the face, hands, and feet, photodistributed reactions, and Malassezia colonization involving the face and neck [4, 6, 28, 29]. However, a 16-week course of dupilumab in over 200 pediatric patients yielded similar improvement across all regions, suggesting that nonatopic confounding causes of inflammation are uncommon during the first 4 months of treatment. On the basis of reports in the literature, dupilumab may have a beneficial effect on some of these co-existing etiologies, especially allergic contact dermatitis [30–33].

The dupilumab regimens assessed here showed improvement in all EASI signs. Improvements in all regions and signs were seen early, after the first or second dupilumab dose, and were sustained through week 16. Although there have been published case series in patients with AD showing apparent new-onset dupilumab-induced facial erythema associated with a spectrum of proposed causes [34–38], in the present analysis the improvements in erythema scores for the head and neck region were comparable with those seen for other signs and anatomical regions. This observation, coupled with the finding that the improvement in regional EASI scores was similar across different anatomical regions including head and neck, suggests that these instances of dupilumab-induced erythema are unlikely to reflect AD lesions that did not respond to dupilumab treatment. Alternatively, worsening facial erythema may be too rare, 4% of patients in one study [35], and not covering enough surface area to be able to be detected by the EASI head and neck region score for a relatively small population of patients.

The efficacy results are accompanied by a safety profile consistent with the primary analyses of the trials: dupilumab was generally well tolerated with an acceptable safety profile [22, 23, 39]. An ongoing phase III study in adults and adolescents with AD affecting hands and feet (NCT04417894) will further evaluate the effect of dupilumab on these sites [40].

This was a post hoc subset analysis, based on data from phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Since the analysis was post hoc and not adjusted for multiplicity, the p values provided in the manuscript are nominal. Other limitations include short-term (16 weeks) duration, relatively small number (N = 263) of dupilumab-treated subjects, and inability to subdivide assessment of EASI parameters within each anatomical region: upper and lower extremity regions cannot be broken down to assess hand or foot involvement/improvement, and the head and neck region cannot be broken down to assess facial involvement/improvement.

Conclusions

In randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials of dupilumab in children with severe and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, baseline disease burden was greater in upper and lower extremities compared with trunk and head and neck. Treatment yielded comparable improvements in erythema, edema/papulation, excoriation, and lichenification across the four anatomical regions beginning within the first 4 weeks of treatment and sustained through week 16. Dupilumab was generally well tolerated with an acceptable safety profile [22, 23].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families for their participation in these studies; their colleagues for their support; and Linda Williams (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), El-Bdaoui Haddad and Adriana Mello (Sanofi Genzyme) for their contributions.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The journal Rapid Service Fee was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Ekaterina Semenova, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. according to the Good Publication Practice guideline.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

ELS, ASP, BS, AB contributed to study concept and design. ELS, ASP, ECS, DT, AW, MJC, DM acquired data. ZC conducted the statistical analyses of the data. RH generated body area color graphics. All authors interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Eric L. Simpson has been an investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and received a consultant’s honorarium from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Forté Biosciences, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmétique, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi Genzyme, and Valeant. Amy S. Paller has been an investigator for AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Lenus Pharma, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and UCB; and a consultant for AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Almirall, Asana Biosciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, BridgeBio Pharma, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Exicure, Forté, Galderma, Incyte, InMed Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, LEO Pharma, LifeMax, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi Genzyme, Sol–Gel, and UCB. Elaine C. Siegfried has been a consultant for Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Verrica Pharmaceuticals; a member of data safety monitoring boards for GlaxoSmithKline, LEO Pharma, and Novan; and a Principal Investigator for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Stiefel, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals. Diamant Thaçi has been a consultant, advisory board member, and/or investigator for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Beiersdorf, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Galderma, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, and UCB. Andreas Wollenberg has been an investigator for Beiersdorf, Eli Lilly, Galderma, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi Genzyme; a consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Galderma, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi Genzyme; and received research grants from Beiersdorf, LEO Pharma, and Pierre Fabre. Michael J. Cork has been a consultant and/or advisory board member and/or received research grants from Astellas Pharma, Atopix, Boots, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, Kymab, L’Oreal, LEO Pharma, Menlo, National Eczema Society, UK, Novartis, Oxagen, Perrigo (ACO Nordic), Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB Pharma. Danielle Marcoux has been an investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, and Pfizer; a Principal Investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Sanofi Genzyme; a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB; and a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi Genzyme. Rui Huang, Zhen Chen, Brad Shumel, and Ashish Bansal are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Ana B. Rossi and Debra Sierka are employees of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Sanofi Genzyme.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All trials were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for good clinical practice and applicable regulatory requirements. The studies were approved by the appropriate institutional ethics committees at each participating institution. All patients provided written consent/assent, and at least one parent or guardian for each adolescent patient provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

For LIBERTY AD ADOL (NCT03054428) and LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914): Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., FDA, EMA, PMDA, etc.), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

References

- 1.Draelos ZD. Use of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in thin and sensitive skin areas. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:98–104. doi: 10.1185/030079908X280419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HH, Patel KR, Singam V, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and phenotype of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1526–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tada J, Toi Y, Arata J. Atopic dermatitis with severe facial lesions exacerbated by contact dermatitis from topical medicaments. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheynius A, Johansson C, Buentke E, Zargari A, Linder MT. Atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome and Malassezia. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:161–169. doi: 10.1159/000053860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, de Bruin-Weller MS, Sigurdsson V. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119–123. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200910020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, Lehmann P. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270–275. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rønnstad ATM, Halling-Overgaard AS, Hamann CR, Skov L, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Association of atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in children and adults: a systematic review and meta–analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler JF, Ghosh A, Sung J, et al. Impact of chronic hand dermatitis on quality of life, work productivity, activity impairment, and medical costs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsambas A, Abeck D, Haneke E, et al. The effects of foot disease on quality of life: results of the Achilles Project. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:191–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2717–2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ference JD, Last AR. Choosing topical corticosteroids. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoepe S, Schäcke H, May E, Asadullah K. Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:406–420. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murrel DF, Calvieri S, Ortonne JP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of pimecrolimus cream 1% in adolescents and adults with head and neck atopic dermatitis and intolerant of, or dependent on, topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:954–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundberg C, Smedegård G. Regional differences in skin blood flow as measured by radioactive microspheres. Acta Physiol Scand. 1981;111:491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1981.tb06768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, et al. Dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75:1188–1204. doi: 10.1111/all.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:425–437. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto TM, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blauvelt A, Rosmarin D, Bieber T, et al. Improvement of atopic dermatitis with dupilumab occurs equally well across different anatomical regions: data from phase III clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:196–197. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbier N, Paul C, Luger T, et al. Validation of the Eczema Area and Severity Index for atopic dermatitis in a cohort of 1550 patients from the pimecrolimus cream 1% randomized controlled clinical trials programme. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, Silverberg JI, et al. Dupilumab provides rapid and sustained improvement in SCORAD outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: combined results of four randomized phase 3 trials. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;8:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1750550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasserbauer N, Ballow M. Atopic dermatitis. Am J Med. 2009;122:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudikoff D, Lebwohl M. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1998;351:1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darabi K, Hostetler SG, Bechtel MA, Zirwas M. The role of Malassezia in atopic dermatitis affecting the head and neck of adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deguchi H, Umemoto N, Sugiura H, Danno K, Uehara M. Ultraviolet light is an environmental factor aggravating facial lesions of adult atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 1998;4:10. doi: 10.5070/D30JK73412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldminz AM, Pamela LS. A case series of dupilumab-treated allergic contact dermatitis patients. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12701. doi: 10.1111/dth.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maloney NJ, Tegtmeyer K, Zhao J, Worswick S. Dupilumab in dermatology: potential for uses beyond atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:S1545961619P1053X. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendricks AJ, Yosipovitch G, Shi VY. Dupilumab use in dermatologic conditions beyond atopic dermatitis—a systematic review. J Dermatol Treat. 2021;32:19–28. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1689227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machler BC, Sung CT, Darwin E, Jacob SE. Dupilumab use in allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:280–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Wijs LEM, Nguyen NT, Kunkeler ACM, Nijsten T, Damman J, Hijnen DJ. Clinical and histopathological characterization of paradoxical head and neck erythema in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:745–749. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soria A, Du-Thanh A, Seneschal J, et al. Development or exacerbation of head and neck dermatitis in patients treated for atopic dermatitis with dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1312–1315. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakanishi M, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Arakawa Y, Masuda K, Katoh N. Dupilumab-resistant facial erythema—dermascopic, histological and clinical findings of three patients. Allergol Int. 2021;70:156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, Grant-Kels JM. Characterizing dupilumab facial redness: a multi-institution retrospective medical record review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:230–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muzumdar S, Zubkov M, Waldman R, DeWane ME, Wu R, Grant-Kels JM. Characterizing dupilumab facial redness in children and adolescents: a single-institution retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1520–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegfried EC, Bieber T, Simpson EL, et al. Effect of dupilumab on laboratory parameters in adolescents with atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00583-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NCT04417894. A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe atopic hand and foot dermatitis (Liberty-AD-HAFT). https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04417894. Accessed Mar 16, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For LIBERTY AD ADOL (NCT03054428) and LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914): Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., FDA, EMA, PMDA, etc.), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.