Abstract

Introduction

Pembrolizumab provided durable responses and acceptable safety in recurrent or metastatic (R/M) cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in the KEYNOTE-629 study. In this elderly, fragile population with disfiguring tumours, preservation of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is critical. Here, we present pre-specified exploratory HRQoL analyses from the first interim analysis of KEYNOTE-629.

Methods

Patients with R/M cSCC not amenable to surgery or radiation therapy received pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for ≤ 24 months. HRQoL end points included change from baseline to week 12 in European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) global health status (GHS)/QoL, functioning, symptom and European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) scores and change from baseline through week 48 in EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores. Improvement (≥ 10-point increase post-baseline with confirmation) was assessed using the exact binomial method.

Results

Analyses included 99 patients for EORTC QLQ-C30 and 100 for EQ-5D-5L. Compliance was > 80% at week 12. Mean scores were stable from baseline to week 12 for GHS/QoL (4.95 points; 95% confidence interval, −1.00 to 10.90) and physical functioning (−3.38 points; 95% confidence interval, −8.80 to 2.04). EORTC-QLQ-C30 functioning, symptom, and EQ-5D-5L scores remained stable at week 12. Post-baseline scores were improved in 29.3% of patients for GHS/QoL, 17.2% for physical functioning, and in a numerically higher proportion of responders versus non-responders (GHS/QoL, 55.6% versus 16.1%; physical functioning, 36.1% versus 7.1%).

Conclusions

In elderly patients with R/M cSCC, the clinical efficacy of pembrolizumab translates into a benefit validated by HRQoL preservation or improvement during treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03284424.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00598-6.

Keywords: Cancer, Clinical trial, Immunotherapy, Pembrolizumab, Quality of life, Squamous cell carcinoma

Plain Language Summary

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common type of non-melanoma skin cancer. cSCC is usually caused by cumulative exposure to sunlight and often occurs in exposed parts of the body such as the head and neck. cSCC is most often seen in older people. If cSCC is detected early, it can be removed by surgery; however, if left untreated, the cancer can spread throughout the body and cause death. The disease itself and its treatment can be painful, cause scarring, or change the patient’s physical appearance. Hence, people with cSCC often have poor quality of life. It is therefore important to develop new drugs to help patients with cSCC live longer without worsening their quality of life. The phase 2 KEYNOTE-629 study investigated how well the drug pembrolizumab treated cSCC and whether it was safe. KEYNOTE-629 included patients who were mostly older and had advanced cSCC. The results showed that pembrolizumab was effective and safe. Here, we investigated how pembrolizumab affected the quality of life of these patients. To do this, we asked patients to answer questionnaires on important aspects of their experience, such as their general health status, physical functioning, emotional wellbeing, and symptoms. We found that patients who were treated with pembrolizumab had stable quality of life during treatment. Furthermore, patients whose cancer responded well to pembrolizumab were more likely to have an improved quality of life. These results support the use of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced cSCC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00598-6.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) experience pain, disfigurement and anxiety, which negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL). |

| Because patients with recurrent or metastatic (R/M) cSCC tend to be fragile due to advanced age, there remains an unmet need for effective treatments that also maintain HRQoL. |

| This pre-specified exploratory analysis investigated HRQoL in patients with R/M cSCC treated with pembrolizumab in the phase 2 KEYNOTE-629 study. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| HRQoL scores were stable with pembrolizumab, indicating HRQoL was not negatively affected by adverse events, and improvements in HRQoL were positively correlated with treatment response. |

| The results of this study show that the efficacy of pembrolizumab can translate into tangible benefit in elderly patients with R/M cSCC. |

Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), the second most common type of non-melanoma skin cancer, accounts for 20% of all skin cancer deaths [1]. Patients with distant metastatic cSCC have mortality rates of ≥ 70% [1, 2]. Approximately 1.8 million cases of cSCC were diagnosed worldwide in 2017, with elderly patients at particularly high risk given that cumulative sun exposure is the primary risk factor for development [3, 4]. The symptoms of cSCC and the high morbidity associated with standard treatment for the disease can result in pain, scarring, disfigurement and anxiety, any of which can affect patients’ overall health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [5, 6]. Patients with cSCC may experience negative psychosocial and mental health effects as a result of treatments that alter their physical appearance or impede their ability to speak, swallow or see, particularly in those with advanced cSCC in the anatomic regions above the clavicle [6–9].

There remains an unmet need for effective and tolerable therapies that also maintain physical functioning and HRQoL for patients whose tumours are unresectable due to anatomical location or recurrence within a previously irradiated field. Treatment guidelines for patients with recurrent or metastatic (R/M) cSCC recommend therapy with programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitors (i.e. cemiplimab or pembrolizumab) if curative surgery or radiotherapy is not feasible, or platinum-containing chemotherapy or epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (e.g. cetuximab) if the patient is ineligible for immunotherapy [10, 11]. The PD-1 inhibitors cemiplimab and pembrolizumab were included in the treatment paradigm based on trials showing effective anti-tumour activity and acceptable tolerability in locally advanced or metastatic cSCC [12–14].

Pembrolizumab has demonstrated extended survival for several advanced malignancies, including R/M head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [15–19] and Merkel cell carcinoma, which, like cSCC, is an ultraviolet-exposure–driven malignancy [20]. The phase 2 KEYNOTE-629 study is a two-cohort trial designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable locally advanced or R/M cSCC [14]. In an interim analysis of the R/M cSCC cohort of KEYNOTE-629 (n = 105; data cutoff, 8 April 2019), pembrolizumab in heavily pre-treated patients demonstrated anti-tumour activity, durable and rapid responses, encouraging survival outcomes and manageable safety [14]. The objective response rate was 34.3% [95% confidence interval (CI) 25.3–44.2], and the disease control rate was 52.4% (95% CI 42.4–62.2); median duration of response was not reached (range 2.7–13.1+ months). Median progression-free survival was 6.9 months (95% CI 3.1–8.5), and median overall survival was not reached (95% CI 10.7 months–not reached). Adverse events were consistent with the established safety profile of pembrolizumab. The patients with R/M cSCC in this study were primarily elderly [median age, 72 years (range 29.0–95.0)] and most were heavily pre-treated, indicating that pembrolizumab is efficacious and well tolerated in a relatively fragile population [14]. The clinical benefit of pembrolizumab demonstrated in KEYNOTE-629 resulted in US Food and Drug Administration regulatory approval for the treatment of R/M cSCC not curable by surgery or radiation therapy [21, 22].

We present results of the pre-specified exploratory HRQoL analyses for patients with R/M cSCC treated with pembrolizumab from the first interim analysis of KEYNOTE-629.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

KEYNOTE-629 (NCT03284424) is an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study of pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable locally advanced or R/M cSCC. The study is ongoing at 39 centres in nine countries. Detailed methods and eligibility criteria for KEYNOTE-629 are published [14]. Briefly, eligible patients were adults with histologically confirmed cSCC as the primary site of malignancy that was metastatic (i.e. disseminated disease) and/or unresectable (i.e. not curable by surgery or radiation therapy) and with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1. Pembrolizumab 200 mg was administered intravenously every 3 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxic effects or study withdrawal for up to 35 cycles (approximately 2 years).

The study protocol and amendments were approved by the appropriate ethics review committees [names listed in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table S1]. All patients gave written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, its amendments and the ethics principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

HRQoL Assessments

HRQoL assessments involved the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [23, 24] and European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) [25, 26]; questionnaires were administered electronically prior to other study procedures at baseline, at weeks 3 and 6, and then every 6 weeks through the first year, every 9 weeks until the end of treatment, and at the 30-day safety follow-up visit.

The EORTC QLQ-C30, the most commonly used cancer-specific instrument to assess HRQoL, is psychometrically and clinically validated [23, 24]. It comprises five functional dimensions, nine items that measure symptoms or cancer-specific concerns, and a global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) scale [24]. The EQ-5D-5L is a standard instrument used to measure health status consisting of two parts: a graded visual analogue scale (VAS) on which patients rate their perceived health status from 0 (worst health you can imagine) to 100 (best health you can imagine), and a descriptive system comprising five health state dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) rated on a five-level descriptive scale (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, extreme problems/unable to) that is used to generate a health state profile for each patient [25, 26]. For the descriptive system, each health state can be assigned an index or utility score based on societal preference weights.

Compliance with the HRQoL questionnaires was defined as the proportion of patients who completed the HRQoL assessment among those who were expected to complete the questionnaires at a given time point, excluding patients missing by design. Patients who were missing by design included those who died; who discontinued due to an adverse event, clinical progression, progressive disease, physician decision or withdrawal from study; who completed study treatment; for whom the clinic visit was not reached or scheduled; and for whom translation was not available. The completion rate for the HRQoL questionnaires was defined as the proportion of patients who completed the HRQoL assessment among all patients in the HRQoL analysis population.

End Points

The pre-specified exploratory HRQoL end points were change from baseline in the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning, and symptom scores, and change from baseline in the EQ-5D-5L health status score. Mean changes from baseline in HRQoL scores were primarily evaluated at week 12 to ensure an adequate completion rate (i.e. ≥ 70% of patients completed the HRQoL assessment among all patients in the HRQoL analysis population). Analyses of mean change from baseline in QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores were also summarised for patients who were on study and able to complete questionnaires at each time point through week 48.

Responses for each of the GHS/QoL, physical functioning and symptom scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 were calculated by averaging the items within the scales and transforming the scores linearly (scales range from 0 to 100) [24]. Symptom scales for which higher scores represented higher symptom burden were reverse-scored to simplify presentation, such that a higher score for GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scales denotes better HRQoL. Responses to the EQ-5D-5L VAS were scored from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health) [26]. EQ-5D-5L responses were weighted and aggregated into utility scores based on the US algorithm, with scores ranging from < 0 (where 0 is equivalent to death) to 1 (equivalent to full health) [26, 27].

A ≥ 10-point change from baseline in the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scores was considered clinically meaningful [28]. The overall proportions of patients with improved, stable and deteriorated GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores relative to baseline were summarised. Overall improvement was defined as a ≥ 10-point increase in score from baseline at any time during the trial, with confirmation at the next visit. For patients who did not achieve improved HRQoL scores, any of the following were defined as stable scores: improvement (≥ 10-point increase in score) confirmed by a < 10-point change at the next visit, < 10-point change in score confirmed by a < 10-point change at the next visit, or a < 10-point change in score and confirmed by an improvement (≥ 10-point increase in score) at the next visit. For patients without improved or stable scores, deterioration was defined as a ≥ 10-point decrease in score from baseline. In addition, an exploratory sub-analysis of the proportion of patients with improved, stable or deteriorated GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores was conducted in patients classified as responders based on objective response [patients with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)] in comparison with non-responders [patients with stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD)], as assessed by blinded independent central review using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1). For the EQ-5D-5L, a ≥ 7-point change from baseline in VAS and a ≥ 0.06 change from baseline in EQ-5D-5L utility index was considered to be a minimally important difference [29].

Statistical Analyses

The HRQoL analysis population included all patients who received ≥ 1 dose of pembrolizumab and had HRQoL assessments at both baseline and at least once after baseline. The exact binomial method was used to assess the overall proportion of patients with improved, stable or deteriorated GHS/QoL and physical functioning relative to baseline. No imputation for missing data was performed. HRQoL analyses were conducted using the interim analysis data cutoff of 8 April 2019.

Results

Patient Disposition and Characteristics

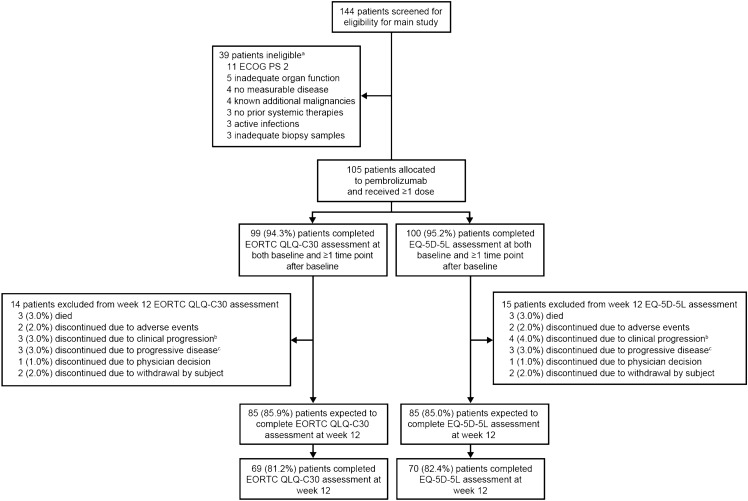

The interim analysis included patients enrolled between 26 October 2017 and 15 June 2018. Of 144 patients screened, 105 with R/M cSCC were allocated to treatment and received ≥ 1 dose; 39 patients were ineligible, and additional detail regarding reasons for ineligibility are presented in the figure and footnotes (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 99 (94.3%) completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 and 100 (95.2%) completed the ED-5D-5L assessments at both baseline and at least once after baseline and were included in the HRQoL analysis populations (Fig. 1). Most of the patients with R/M cSCC who completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 were elderly; the median age was 73 years, 69 (69.7%) were aged ≥ 65 years, and 15 (15.2%) were aged ≥ 80 years (ESM Table S2). Most patients were male [n = 75 (75.8%)], and 63 patients (63.6%) had a baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1; 81 patients (81.8%) had stage IV disease, and 73 (73.7%) had previously received radiation therapy. Most patients were heavily pre-treated; 14 (14.1%) received pembrolizumab as first-line therapy, and 85 (85.9%) had received ≥ 1 prior systemic therapy. The baseline characteristics of patients who completed the EQ-5D-5L assessment were similar to those who completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 (ESM Table S2). The median follow-up was 11.4 months (range 0.4–16.3 months) [14].

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition in the health-related quality of life population. CNS central nervous system, cSCC cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, EORTC QLQ-C30 European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, EQ-5D-5L European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 5-Level, RECIST v1.1 Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours version 1.1. aParticipants may have been excluded for more than one reason. Reasons not listed included no metastatic disease or previously treated locally recurrent disease (n = 2), another histologic type of skin cancer other than invasive squamous cell carcinoma as the primary disease (n = 2), diagnosed with and/or treated for additional malignancy within the past 5 years (n = 2), known active central nervous system metastases and/or carcinomatous meningitis (n = 2), no histologically confirmed cSCC as the primary site of malignancy (n = 1), not willing to provide informed consent (n = 1), history of (non-infectious) pneumonitis that required treatment with steroids or had current pneumonitis (n = 1), and another inclusion/exclusion criterion that prevented enrolment in the study (n = 1). bClinical progression was defined as worsening of clinical status with or without radiographic progression of disease. cProgressive disease was defined as radiographically diagnosed disease progression per RECIST v1.1 criteria

HRQoL Instrument Completion and Compliance

At week 12, compliance rates were 81.2% for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and 82.4% for the EQ-5D-5L (Fig. 1; ESM Table S3). The compliance rates remained ≥ 78% for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and ≥ 80% for the EQ-5D-5L at all post-baseline time points except week 42. Completion rates decreased at each time point as participants discontinued the study, primarily due to disease progression or death. The completion rates at week 12 were 69.7% and 70.0% for EORTC QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D-5L, respectively.

Mean Change from Baseline in HRQoL Scores

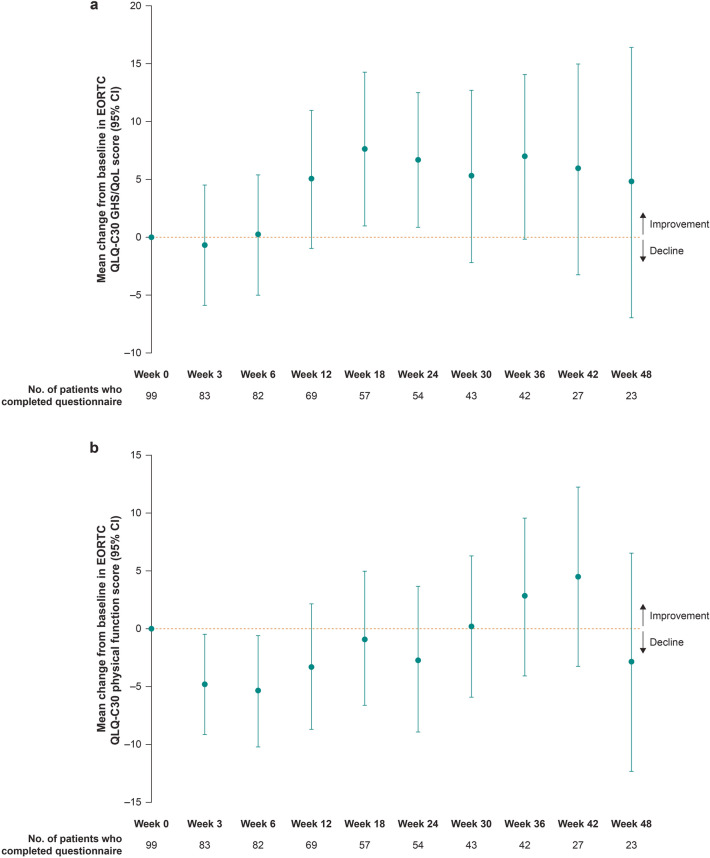

For patients who remained on study at week 12, the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL and physical function scores remained stable over 12 weeks of treatment; the mean change from baseline was 4.95 points (95% CI −1.00 to 10.90) and −3.38 points (95% CI −8.80 to 2.04) for GHS/QoL and physical functioning, respectively (Table 1). Descriptive analyses of mean change from baseline further revealed that the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores remained stable over time through week 48 for those who were on study and able to complete questionnaires (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Mean change from baseline in European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) and physical functioning scores for patients on study at week 12

| GHS/QoLa (N = 69) | Physical functioninga (N = 69) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 60.99 (23.68) | 74.78 (21.08) |

| Week 12, mean (SD) | 65.94 (22.08) | 71.40 (22.64) |

| Change from baseline to week 12, mean (95% CI) | 4.95 (–1.00 to 10.90) | –3.38 (–8.80 to 2.04) |

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation

aFor GHS/QoL scores and all functioning scales, a higher score denotes better health-related quality of life or function. A ≥ 10-point change from baseline in the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scores was considered clinically meaningful [28]

Fig. 2.

Mean change from baselinea in a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) score and b EORTC QLQ-C30 physical function score for patients on study at each time point.b CI confidence interval, HRQoL health-related quality of life. aFor GHS/QoL scores and all functioning scales, a higher score denotes better HRQoL or function. A ≥ 10-point change from baseline in the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scores was considered clinically meaningful [28]. bThese analyses are purely descriptive given the smaller proportion of patients who completed questionnaires after week 12

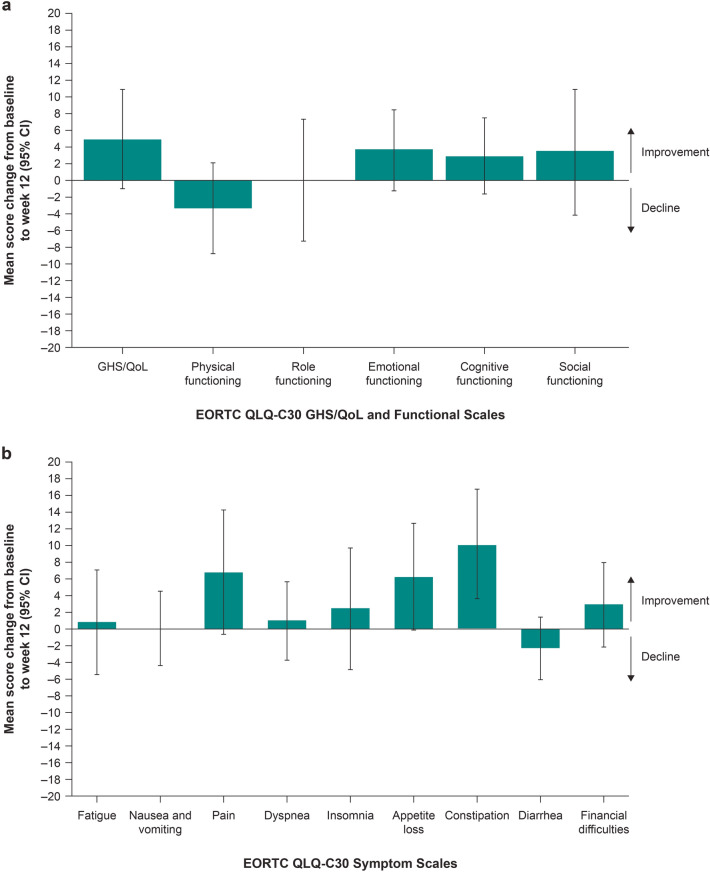

Patients who remained on study at week 12 generally exhibited stable scores for the other functioning and symptom scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Fig. 3). A clinically meaningful improvement relative to baseline in constipation score was observed at week 12. Similarly, for patients who remained on study at week 12, the EQ-5D-5L VAS and utility scores remained stable from baseline to week 12, with a mean change of 1.97 points (95% CI −3.85 to 7.79) and −0.01 points (95% CI −0.07 to 0.06), respectively (ESM Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Mean change from baselinea for patients on study at week 12 in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) a global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) and functioning scales and b symptom scales. HRQoL health-related quality of life, R/M recurrent and/or metastatic. aFor GHS/QoL scores and all functioning scales, a higher score denotes better HRQoL or function. Symptom scales were reverse-scored to simplify presentation, such that a higher score also denotes better symptoms. A ≥ 10-point change from baseline in the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scores was considered clinically meaningful [28]

Proportion with Improved, Stable or Deteriorated HRQoL Scores

Overall, most patients experienced stable or improved EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QoL (70.7%; 95% CI 60.7–79.4) and physical functioning (64.6%; 95% CI 54.4–74.0) scores relative to baseline (Table 2). The proportion with improved post-baseline scores was 29.3% (95% CI 20.6–39.3) for GHS/QoL and 17.2% (95% CI 10.3–26.1) for physical functioning. Descriptive analyses according to treatment response showed a greater proportion of responders (CR or PR) experienced improved GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores relative to baseline compared with non-responders (SD or PD). Among responders (n = 36), 55.6% (95% CI 38.1–72.1) had improved GHS/QoL scores relative to baseline compared with 16.1% (95% CI 7.6–28.3) among non-responders (n = 56). Similarly, 36.1% (95% CI 20.8–53.8) of responders had improved physical functioning scores, compared with 7.1% (95% CI 2.0–17.3) of non-responders.

Table 2.

Overall proportion with improved, stable or deteriorateda European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) and physical functioning scores relative to baseline, by treatment response

| Overall (N = 99) |

Responders (CR or PR)b (N = 36) |

Non-responders (SD or PD)b (N = 56) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95% CI)c | n | % (95% CI)c | n | % (95% CI)c | |

| GHS/QoL | ||||||

| Non-deterioratedd | 70 | 70.7 (60.7–79.4) | 34 | 94.4 (81.3–99.3) | 36 | 64.3 (50.4–76.6) |

| Improved | 29 | 29.3 (20.6–39.3) | 20 | 55.6 (38.1–72.1) | 9 | 16.1 (7.6–28.3) |

| Stable | 41 | 41.4 (31.6–51.8) | 14 | 38.9 (23.1–56.5) | 27 | 48.2 (34.7–62.0) |

| Deteriorated | 29 | 29.3 (20.6–39.3) | 2 | 5.6 (0.7–18.7) | 20 | 35.7 (23.4–49.6) |

| Physical functioning | ||||||

| Non-deterioratedd | 64 | 64.6 (54.4–74.0) | 31 | 86.1 (70.5–95.3) | 33 | 58.9 (45.0–71.9) |

| Improved | 17 | 17.2 (10.3–26.1) | 13 | 36.1 (20.8–53.8) | 4 | 7.1 (2.0–17.3) |

| Stable | 47 | 47.5 (37.3–57.8) | 18 | 50.0 (32.9–67.1) | 29 | 51.8 (38.0–65.3) |

| Deteriorated | 35 | 35.4 (26.0–45.6) | 5 | 13.9 (4.7–29.5) | 23 | 41.1 (28.1–55.0) |

CI confidence interval, CR complete response, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, RECIST v1.1 Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours version 1.1, SD stable disease

aOverall improvement was defined as a ≥ 10-point increase in score from baseline at any time during the trial with confirmation at the next visit [28]. For patients who did not achieve improved health-related quality of life scores, stable scores were defined by a < 10-point worsening in score from baseline, and deterioration was defined as a ≥ 10-point decrease in score from baseline at any time during the trial and confirmed at the next consecutive visit

bResponse per RECIST v1.1 by blinded independent central review. Response was not evaluable in two patients and not assessed in eight patients

cBased on the exact method for binomial data

dIncludes improved + stable scores

Discussion

Efficacious therapies with manageable tolerability that do not negatively affect HRQoL in patients with R/M cSCC are needed. Pembrolizumab demonstrated durable anti-tumour activity and acceptable safety in patients with R/M cSCC in the first interim analysis of KEYNOTE-629 [14]. However, because patients with R/M cSCC tend to be fragile due to advanced age, it is particularly important to assess the impact of pembrolizumab treatment on HRQoL in this population. In this pre-specified exploratory HRQoL analysis of KEYNOTE-629, patients treated with pembrolizumab who remained on study at week 12 demonstrated stable overall GHS/QoL, functioning and symptom scores; in addition, a correlation was observed between HRQoL benefit and response to pembrolizumab. Furthermore, the descriptive trend in stable GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores extended for as long as 48 weeks. These findings support the benefit of pembrolizumab monotherapy in this elderly patient population.

Growing evidence from immunotherapy trials has shown that monotherapy with PD-1 inhibitors provides efficacy and safety benefits while maintaining or improving HRQoL in several tumour types [30]. The results of KEYNOTE-629 and a phase 2 trial of cemiplimab further support the benefits of PD-1 inhibitors in cSCC, with both studies reporting durable responses with stable or improved HRQoL in patients with advanced cSCC receiving treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor [13, 14, 31]. In the exploratory analysis of HRQoL in the phase 2 trial of cemiplimab, patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic cSCC had a clinically meaningful reduction in pain at cycle 5 of cemiplimab (administered at 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 12 cycles or 350 mg every 3 weeks for 6 cycles), with most patients having stable or a trend toward improved HRQoL scores across the other EORTC QLQ-C30 domains [31]. The generally stable or improved HRQoL with pembrolizumab and cemiplimab is particularly notable given the advanced and primarily elderly populations that were studied. The limitations of the current HRQoL analysis include the single-arm design of KEYNOTE-629. To our knowledge, HRQoL analyses have not been published for other treatments that are commonly used for R/M cSCC, such as epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, and therefore, the effect of these agents on HRQoL is unclear.

Conclusions

In this study, the stability of HRQoL in patients with R/M cSCC treated with pembrolizumab showed that HRQoL was not negatively affected by adverse events. Most patients exhibited stable overall HRQoL and physical functioning scores over time. Furthermore, improvements in HRQoL scores were positively correlated with treatment response, with a greater proportion of responders (CR or PR) experiencing improved GHS/QoL and physical functioning scores relative to baseline compared with non-responders (SD or PD). This result shows that the efficacy of pembrolizumab can translate into tangible benefit in elderly patients with R/M cSCC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families and all investigators and site personnel. In addition, the authors thank Zhi Jin Xu for statistical analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. The study sponsor also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: Olga Vornicova, Diana Chirovsky, Ramona F. Swaby; Methodology: Brett G. M. Hughes, Olga Vornicova, Abhishek Joshi, Josep M. Piulats, Diana Chirovsky, Pingye Zhang, Burak Gumuscu, Ramona F. Swaby, Jean-Jacques Grob; Formal analysis and investigation: Brett G. M. Hughes, Rene Gonzalez Mendoza, Nicole Basset-Seguin, Olga Vornicova, Abhishek Joshi, Nicolas Meyer, Florent Grange, Josep M. Piulats, Jessica R. Bauman, Diana Chirovsky, Pingye Zhang, Burak Gumuscu, Ramona F. Swaby, Jean-Jacques Grob; Writing—original draft preparation: Brett G. M. Hughes, Abhishek Joshi, Nicolas Meyer, Josep M. Piulats, Jessica R. Bauman, Diana Chirovsky, Pingye Zhang, Burak Gumuscu, Ramona F. Swaby, Jean-Jacques Grob; Writing—review and editing: Brett G. M. Hughes, Rene Gonzalez Mendoza, Nicole Basset-Seguin, Olga Vornicova, Jacob Schachter, Abhishek Joshi, Nicolas Meyer, Florent Grange, Josep M. Piulats, Jessica R. Bauman, Diana Chirovsky, Pingye Zhang, Burak Gumuscu, Ramona F. Swaby, Jean-Jacques Grob; Funding acquisition: None. Resources: Brett G. M. Hughes, Olga Vornicova, Jean-Jacques Grob; Supervision: Brett G. M. Hughes, Olga Vornicova, Josep M. Piulats, Jessica R. Bauman, Diana Chirovsky, Burak Gumuscu, Ramona F. Swaby, Jean-Jacques Grob.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Jemimah Walker, PhD, and Doyel Mitra, PhD, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Disclosures

Brett G. M. Hughes reports serving as an advisor for Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD), and receiving an institutional research grant from Amgen. Rene Gonzalez Mendoza has nothing to disclose. Nicole Basset-Seguin and Olga Vornicova report being investigators for MSD. Jacob Schachter reports receiving personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb. Abhishek Joshi reports receiving grants from Novartis, Roche, Ipsen, AstraZeneca, and Bristol Myers Squibb. Nicolas Meyer reports being an investigator and/or consultant and/or speaker and/or received research grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Roche, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Merck GmbH, AbbVie, and Sun Pharma. Florent Grange has nothing to disclose. Josep M. Piulats reports receiving grants from MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb, BeiGene, and Janssen, and personal fees from MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb, BeiGene, Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Astellas, and Sanofi-Genzyme. Jessica R. Bauman reports serving as a consultant/advisor for Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Kura, and Bayer. Diana Chirovsky reports employment at MSD and is a shareholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Pingye Zhang and Burak Gumuscu report employment at MSD. Ramona F. Swaby was an employee of MSD at the time of the conduct of the study; she reports current employment at Prelude Therapeutics, 200 Powder Mill Road, Wilmington, DE 19803, USA. Jean-Jacques Grob reports serving as an advisor for MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Pierre Fabre, Merck, Pfizer, and Sun Pharma and reports receiving travel funding or speaker fees from MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pierre Fabre. Ramona F. Swaby was an employee of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA at the time the study was conducted.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study protocol and amendments were conducted in accordance with the ethics principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the appropriate ethics review committees (ESM Table S1). All patients gave written informed consent.

Data Availability

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD) is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymised data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the USA and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country- or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.

Prior Presentation

This work was presented as a poster at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium 2020; February 27–29, 2020; Scottsdale, AZ, USA.

Footnotes

Ramona F. Swaby was affiliated to Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA at the time the study was conducted.

References

- 1.Burton KA, Ashack KA, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review of high-risk and metastatic disease. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(5):491–508. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Garcovich S, Colloca G, Sollena P, et al. Skin cancer epidemics in the elderly as an emerging issue in geriatric oncology. Aging Dis. 2017;8(5):643–661. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749–1768. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdon-Jones D, Thomas P, Baker R. Quality of life issues in nonmetastatic skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang AY, Palme CE, Wang JT, et al. Quality of life assessment in patients treated for metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(Suppl 2):S39–47. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerring RC, Ott CT, Curry JM, Sargi ZB, Wester ST. Orbital exenteration for advanced periorbital non-melanoma skin cancer: prognostic factors and survival. Eye. 2017;31(3):379–388. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherecheanu AP, Stana D, Ungureanu E, et al. Comparative survival rate, ocular quality of life and social quality of life in patients with malignant T3–T4 orbito-sinusal tumors treated with exenteration vs. conservative procedures. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;78:360–4.

- 9.McNab AA, Francis IC, Benger R, Crompton JL. Perineural spread of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma via the orbit. Clinical features and outcome in 21 cases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(9):1457–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Stratigos AJ, Garbe C, Dessinioti C, et al. European interdisciplinary guideline on invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Part 1. Epidemiology, diagnostics and prevention. Eur J Cancer. 2020;128:60–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Squamous Cell Skin Cancer. Version 1.2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 12.Migden MR, Khushalani NI, Chang ALS, et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):341–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grob JJ, Gonzalez R, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm phase II trial (KEYNOTE-629) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(25):2916–2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehra R, Seiwert TY, Gupta S, et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: pooled analyses after long-term follow-up in KEYNOTE-012. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(2):153–159. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0131-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauml J, Seiwert TY, Pfister DG, et al. Pembrolizumab for platinum- and cetuximab-refractory head and neck cancer: results from a single-arm, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(14):1542–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen EEW, Soulieres D, Le Tourneau C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):156–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rischin D, Harrington KJ, Greil G, et al. Protocol-specified final analysis of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-048 trial of pembrolizumab (pembro) as first-line therapy for recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15 suppl):6000.

- 19.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1915–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2542–2552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Food and Drug Administration approves pembrolizumab for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. June 24, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma. Accessed 24 June 2021.

- 22.Keytruda® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. 08/2021. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA; 2021.

- 23.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference values. Brussels, Belgium: EORTC Groups; 2008.

- 25.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D user guide. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/. Accessed 24 June 2021.

- 27.Pickard AS, Law EH, Jiang R, et al. United States valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states using an international protocol. Value Health. 2019;22(8):931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel-Rahman O, Oweira H, Giryes A. Health-related quality of life in cancer patients treated with PD-(L)1 inhibitors: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(12):1231–1239. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1528146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Migden MR, Rischin D, Sasane M, et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) treated with cemiplimab: post hoc exploratory analyses of a phase II clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 suppl):10033.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD) is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymised data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the USA and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country- or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.