Abstract

Background

Previous reports have revealed inadequate resident education and textbook representation of dermatological conditions in patients with skin of color (SoC). This suggests that the literature and continuing medical education are important alternative dermatology educational resources to aid in diagnosing and treating patients of color.

Objective

This study develops criteria to assess and examine the prevalence of SoC-related publications among top dermatology journals.

Methods

We developed the first-ever prespecified criteria that allow for the assessment of diversity in the dermatologic literature. The archives of 52 dermatology journals from January 2018 to October 2020, selected based on Scopus ranking, were analyzed for journal characteristics and content regarding skin and hair of color, diversity and inclusion, and socioeconomic/health care disparities that affect underrepresented populations with SoC.

Results

Our study reveals that the average percentage of overall publications relevant to SoC is quite low. The percent of SoC articles ranged from 2.04% to 16.8% with a mean of 16.3%. The top-performing dermatology journals in SoC were, not surprisingly, from countries with populations with SoC; however, the Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy, Australasian Journal of Dermatology, and Journal of the American Academy of Dermatol Case Reports were among the top 10. Research and higher-impact journals were among the lowest in SoC rankings, including the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Experimental Dermatology, and Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, and had <5% of articles on SoC.

Conclusion

We believe that the criteria we established could be used by journal editors to include at least 16.8% of SoC-relevant articles in each issue. Increasing SoC content in the dermatological literature, and particularly in high-impact journals, will serve as an invaluable educational resource and aid in promoting excellence in the care of patients with SoC.

Keywords: Diversity, skin of color, equity and inclusion, medical education, dermatology education, medical literature, journal analysis

Introduction

Alongside medical training, resources such as textbooks, the research literature, and continuing medical education (CME) courses contribute to the fund of knowledge that dermatologists draw on to treat patients with skin of color (SoC). According to a 2011 report, nearly half of dermatologists believe they have had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types (Buster, 2011). Most practicing dermatologists completed their residency during a time when the diagnosis and treatment of SoC was not emphasized throughout training. A 2006 study revealed that from 1996 to 2005, only 2% of teaching events at the American Academy of Dermatology focused on SoC (Ebede and Papier, 2006). The current study, as well as a 2020 study, surveyed images in textbooks of skin disease and discovered that only 4% to 19% of photographs documented diseases in darker skin types (Adelekun et al., 2021; Ebede and Papier, 2006). Given that most textbooks lack adequate clinical photographs of dermatological conditions in SoC (Ebede and Papier, 2006), research and CME are particularly valuable sources of information for diagnosing and treating SoC.

Although prior studies have assessed the presence of SoC-related topics in dermatology textbooks and educational opportunities offered through the American Academy of Dermatology, to our knowledge, there are no studies to date assessing peer-reviewed dermatology publications for content associated with SoC (Adelekun et al., 2021; Buster, 2011; Ebede and Papier, 2006). This study aimed to develop criteria to assess SoC-related publications, as well as examine the SoC content published in the dermatological literature over the past 3 years.

Methods

The archives of 52 dermatology journals from January 2018 to October 2020 were reviewed. Fifty of the 52 journals were selected based on their Scopus rating. We excluded wound care and burn journals, dermatopathology journals, and journals that did not have English abstracts and titles. The criteria were developed to assess journals for journal classification and SoC relevance.

Journal category classification criteria

The journals were classified as international if one of the following criteria was met: 1) Journal's title has the word “international” in the title; 2) journal's title specifies a continent—however, if the title specifies a specific country, the journal does not meet the definition of “international” and is not categorized as such (e.g., the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology is international because the journal does not belong to a national society and instead represents multiple European countries); and 3) journal belongs to an international society—however, if a journal specifically belongs to a national society, then it is considered national and not international (e.g., Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology is American and British Journal of Dermatology is British; thus, these are national). Also, the website homepage of journals whose title did not include a continent, country, or the term “international” were searched to see if the journal belonged to a national society. If the journal did not belong to a specific national society, it was considered international.

Journals were classified as covering SoC if they came from a country where the majority of the population has Fitzpatrick skin type III or higher.

Journals were classified as scientific if the title of the journal included one of the following words: science, immunology, research, physiology, investigative, or experimental. If a journal did not meet the criteria for the scientific classification, it was designated as a clinical journal.

Skin of color relevance criteria

The titles and available abstracts of the 52 journals were surveyed for association with skin and hair of color, diversity and inclusion, and socioeconomic/health care disparities that affect underrepresented populations with SoC. We developed the first-ever prespecified criteria that allow for the assessment of SoC and diversity in the dermatologic literature. We created two tiers of publications to assess the available literature.

Tier 1 was further separated into five subtiers:

A) Journal title specifically addresses SoC, skin type, or race and ethnicity (i.e., Asian, Hispanic, Latino, Black, African-American, Middle-Eastern)

B) Title specifically addresses a country or continent in which the majority of the population has Fitzpatrick skin type III to VI. Case reports from countries in which most of the population has skin type III to VI were also included in this category (e.g., cases from Korea, Iran, Kenya)

C) Title specifically addresses socioeconomic/health disparities that are relevant to underrepresented populations with SoC

D) Title specifically addresses issues regarding diversity and inclusion within the field of dermatology

E) Case reports in which the text or an image presents a patient with SoC in a non-SOC country (i.e., patient with SoC presented in countries in which the majority of the population has Fitzpatrick skin type I to II, such as Sweden or the United States, or a case report from France presenting a Black patient)

For tier 2, the journal title specifically addresses pigmentary skin and hair diseases that are particularly relevant to patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III to VI because of hair type (curl pattern types 3-4) and pigmentation presence in the skin. Conditions meeting this criterion and captured in this study include skin and hair discoloration, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, vitiligo, erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, folliculitis decalvans, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, tinea barbae, and Mongolian spot. Note that we did not include topics that may have a predilection toward patients with SoC if the skin or hair condition itself was not directly related to the patient's pigmentary skin or hair curl type. For this reason, conditions such as discoid lupus, atopic dermatitis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and hidradenitis suppurativa, were not included in this study.

Using these criteria, all journals were classified and examined for SoC-relevant articles and CME. All statistical analyses were conducted in R statistical software, version 4.0.2.

Results

Journal characteristics

Fifty-two academic dermatology journals were included in our study. Scopus CiteScore information was publicly available for all journals, with the exception of Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. The majority of journals originated from multiple continents (30.8%), North America (26.9%), or Europe (25.0%). Based on the described criteria, seven journals (13.5%) were classified as covering SoC, 33 journals (63.5%) as international, and 11 journals (21.2%) as scientific, while 41 journals (78.8%) focused on clinical topics.

Skin of color relevance

Journals were ranked by their total percentage of articles on SoC relative to the total number of articles published from 2018 to 2020 (Table 1). Across all journals, the mean percentage of articles on SoC was 16.8% and ranged from 2.04% to 61.81%. In four journals, the percentage of articles on SoC published was within 0.05% of or >50%: Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology; Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy; and Leprosy Review. These top-ranked journals were all classified as having a clinical focus. Two of the four journals originated from Asia. Ten journals exhibited SoC article percentages of <5%. Ten journals, none of which were from countries with populations with SoC and the majority of which originated from Europe and North America, exhibited the lowest SoC article percentages of <5%.

Table 1.

Journals ranked by percentage of articles on SoC from 2018 to 2020, with relevant characteristics

| SoC rank | Scopus CiteScore | Journal | Continent | SoC | Intl | Category | Total articles | SoC articles | SoC articles, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Indian Journal of Dermatology | Asia | Y | N | Clinical | 364 | 225 | 61.81 |

| 2 | 2.5 | Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology | Asia | Y | N | Clinical | 568 | 317 | 55.81 |

| 3 | 2 | Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 195 | 106 | 54.36 |

| 4 | 1 | Leprosy Review | Europe | Y | Y | Clinical | 140 | 69 | 49.29 |

| 5 | 0.1 | Hong Kong Journal of Dermatology and Venereology | Asia | Y | N | Clinical | 73 | 34 | 46.58 |

| 6 | 4.2 | Journal of Dermatology | Asia | N | N | Clinical | 1401 | 486 | 34.69 |

| 7 | 2.9 | Australasian Journal of Dermatology | Oceania | N | N | Clinical | 637 | 216 | 33.91 |

| 8 | 1.9 | Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia | South America | Y | N | Clinical | 568 | 189 | 33.27 |

| 9 | 1.3 | JAAD Case Reports | North America | N | N | Clinical | 1079 | 359 | 33.27 |

| 10 | 1.8 | Annals of Dermatology | Asia | Y | N | Clinical | 438 | 143 | 32.65 |

| 11 | 1.3 | Dermatologica Sinica | Asia | Y | N | Clinical | 183 | 53 | 28.96 |

| 12 | 2 | Pediatric Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 730 | 207 | 28.36 |

| 13 | 2.4 | Clinical and Experimental Dermatology | Europe | N | N | Scientific | 899 | 220 | 24.47 |

| 14 | 5.6 | Mycoses | Europe | N | Y | Clinical | 396 | 77 | 19.44 |

| 15 | 2.9 | Photodermatology Photoimmunology and Photomedicine | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 197 | 38 | 19.29 |

| 16 | 0.8 | Cutis | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 709 | 132 | 18.62 |

| 17 | 4.5 | Acta Dermato-Venereologica | Europe | N | Y | Clinical | 848 | 147 | 17.33 |

| 18 | 2.9 | International Journal of Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 1318 | 209 | 15.86 |

| 19 | 2 | Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 930 | 143 | 15.38 |

| 20 | 3 | Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 267 | 38 | 14.23 |

| 21 | 2.4 | Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 390 | 55 | 14.10 |

| 22 | 9.2 | JAMA Dermatology | North America | N | N | Clinical | 941 | 132 | 14.03 |

| 23 | 6.1 | Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 209 | 28 | 13.40 |

| 24 | 1.8 | Dermatologic Therapy | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 1216 | 154 | 12.66 |

| 25 | 3.5 | Contact Dermatitis | Europe | N | Y | Clinical | 669 | 82 | 12.26 |

| 26 | 2.2 | Journal of Drugs in Dermatology | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 594 | 67 | 11.28 |

| 27 | 2.9 | Skin Research and Technology | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 331 | 37 | 11.18 |

| 28 | 6.6 | Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology | Europe | N | Y | Clinical | 2011 | 222 | 11.04 |

| 29 | 3.4 | International Journal of Cosmetic Science | Europe | N | Y | Scientific | 203 | 22 | 10.84 |

| 30 | 2.1 | International Journal of Women's Dermatology | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 309 | 30 | 9.71 |

| 31 | 4.8 | Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 181 | 16 | 8.84 |

| 32 | 0.7 | Journal of Cosmetic Science | North America | N | Y | Scientific | 76 | 6 | 7.89 |

| 33 | 5.3 | Lasers in Surgery and Medicine | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 323 | 23 | 7.12 |

| 34 | 6.3 | Journal of Dermatological Science | Asia | N | N | Scientific | 466 | 33 | 7.08 |

| 35 | 4.8 | Clinics in Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 247 | 17 | 6.88 |

| 36 | 2.4 | European Journal of Dermatology | Europe | N | Y | Clinical | 677 | 46 | 6.79 |

| 37 | 3.2 | Dermatologic Surgery | North America | N | Y | Clinical | 970 | 64 | 6.60 |

| 38 | 4.1 | Archives of Dermatological Research | North America | N | Y | Scientific | 264 | 17 | 6.44 |

| 39 | 3.5 | Journal of Dermatological Treatment | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 460 | 29 | 6.30 |

| 40 | 7.6 | American Journal of Clinical Dermatology | North America | N | N | Clinical | 221 | 13 | 5.88 |

| 41 | 9.8 | British Journal of Dermatology | Europe | N | N | Clinical | 2796 | 162 | 5.79 |

| 42 | 4.6 | Dermatitis | North America | N | N | Clinical | 252 | 14 | 5.56 |

| 43 | 6.7 | Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology | North America | N | N | Clinical | 1797 | 88 | 4.90 |

| 44 | 5.4 | Dermatology and Therapy | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 226 | 11 | 4.87 |

| 45 | 8.1 | Journal of Investigative Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 1198 | 53 | 4.42 |

| 46 | 5.4 | Experimental Dermatology | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 547 | 24 | 4.39 |

| 47 | 1.5 | Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia | Europe | N | N | Clinical | 433 | 17 | 3.93 |

| 48 | 5.4 | Dermatologic Clinics | Multiple | N | Y | Clinical | 167 | 5 | 2.99 |

| 49 | NA | Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft | Europe | N | N | Clinical | 555 | 15 | 2.70 |

| 50 | 4.3 | Melanoma Research | Multiple | N | Y | Scientific | 267 | 7 | 2.62 |

| 51 | 2.2 | Postepy Dermatologii I Alergologii | Europe | N | N | Clinical | 388 | 9 | 2.32 |

| 52 | 4.3 | Skin Pharmacology and Physiology | Europe | N | Y | Scientific | 98 | 2 | 2.04 |

intl, international; N, no; SoC, skin of color; Y, yes

Analysis of skin of color article tiers

We calculated the percentage of articles on SoC in each SoC tier across all journals (Fig. 1). Nearly two-thirds (61.88%) of all articles on SoC were Tier 1B, meaning they originated from a country with a population where the majority of people had SoC. A significantly lower percentage of SoC publications came from non-SoC countries (Tier 1E) compared with SoC countries (tier 1B: 61.88% vs. tier 1E: 12.07%; p < .05). The next most frequent tier types were Tier 1A (12.21%) and Tier 2 (12.13%), corresponding to articles with titles specifically addressing SoC, skin type, or race and ethnicity and titles specifically addressing pigmentary skin and hair diseases that are particularly relevant to patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III to VI, respectively.

Fig 1.

Tier percentages for articles on skin of color (all journals).

Similar results were found in a subgroup analysis based on journal category (Table 2). In every journal category, Tier 1B articles comprised the largest proportion of publications relevant to SoC. Tier 1C and Tier 1D articles were the least common across all categories, representing <2% of articles on SoC. Interestingly, the percentage of Tier 1A articles was lowest in journals covering SoC (5.44%). The proportion of Tier 2 articles differed substantially between non-SoC and SoC journals, as well as between non-international and international journals.

Table 2.

Tier percentages for articles on SoC

| Journal category | SoC articles, % total articles | Tier 1A, % | Tier 1B, % | Tier 1C, % | Tier 1D, % | Tier 1E, % | Tier 2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-SoC country | 13.33 | 14.03 | 54.74 | 1.44 | 0.70 | 15.24 | 13.85 |

| SoC country | 44.13 | 5.44 | 88.64 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 5.73 |

| Noninternational | 19.19 | 9.53 | 69.05 | 1.33 | 0.44 | 11.64 | 8.01 |

| International | 12.57 | 15.71 | 52.63 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 12.60 | 17.41 |

| Clinical | 16.60 | 11.41 | 63.47 | 1.21 | 0.50 | 12.48 | 10.93 |

| Scientific | 2.04 | 50.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 |

SoC, skin of color

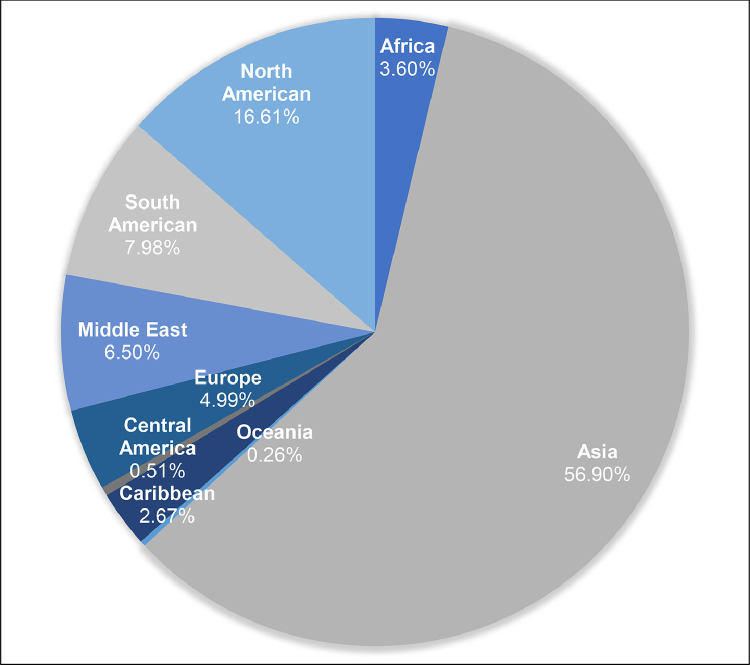

Geographical analysis of published articles on skin of color

We analyzed the geographical origins of all publications on SoC and their patient cohorts (Fig. 2). The large majority (56.90%) of all articles originated from and/or pertained to populations in Asia, followed by North America (16.61%). Less than 5% of articles originated from and/or pertained to populations in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean, and <1% in Central America and Oceania. We found similar results when stratifying journals by category (Table 3). In every journal category, >50% and up to 65.93% of articles on SoC originated from and/or pertained to populations in Asia. The second and third most frequent geographies were North America and Europe, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Country of origin percentages for articles on skin of color (all journals).

Table 3.

Geographical origin percentages for articles on SoC

| Journal category | Tier 1, % total articles | Africa, % | Asia, % | Australia, % | Caribbean, % | Central America, % | Europe, % | Middle East, % | South America, % | North America, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SoC country | 11.49 | 4.01 | 56.00 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 5.87 | 6.73 | 5.03 | 21.31 |

| Non-SoC country | 41.60 | 2.16 | 59.94 | 0.00 | 10.81 | 0.82 | 2.06 | 5.66 | 18.13 | 0.41 |

| International | 17.85 | 1.63 | 61.46 | 0.36 | 4.42 | 0.44 | 3.55 | 5.62 | 8.77 | 13.75 |

| Noninternational | 10.38 | 6.32 | 50.53 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.61 | 7.04 | 7.71 | 6.88 | 20.58 |

| Clinical | 14.79 | 3.43 | 55.94 | 0.23 | 2.92 | 0.54 | 4.76 | 6.30 | 8.38 | 17.49 |

| Scientific | 8.12 | 5.15 | 65.93 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 7.35 | 8.33 | 4.17 | 8.09 |

SoC, skin of color

For all Tier 1 articles in North America, we further evaluated the ethno-racial composition of such studies (Fig. 3). Across these articles, 39.80% of all SoC-relevant studies originating from North America included nonwhite patients belonging to multiple and/or unspecified racial groups. Of the remaining articles that provided this information, 33.94% included Black patients, 14.66% Latino patients, 9.50% Asian patients, and 2.09% Middle Eastern patients (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Patient race/ethnicity percentages for North America tier 1 articles on skin of color (all journals).

Table 4.

Patient race/ethnicity percentages for North American tier 1 articles on SoC

| Journal type | North America tier 1, % total articles | Asian, % | Black, % | Latino, % | Middle Eastern, % | Multiple and/or unspecified, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SoC country | 2.45 | 9.55 | 34.13 | 14.33 | 2.11 | 39.89 |

| Non-SoC country | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 75.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 |

| International | 2.45 | 9.86 | 32.75 | 13.62 | 2.61 | 41.16 |

| Noninternational | 2.14 | 9.16 | 35.04 | 15.63 | 1.62 | 38.54 |

| Clinical | 2.59 | 9.96 | 33.82 | 15.08 | 2.05 | 39.09 |

| Scientific | 0.66 | 0.00 | 36.36 | 6.06 | 3.03 | 54.55 |

SoC, skin of color

Analysis of skin of color–relevant content between journal categories

The total percentage of articles on SoC was compared between journal categories (Table 2). Journals covering SoC (M = 12.3%) and clinical journals (M = 9.9%) had significantly greater SoC article percentages than non-SoC journals (M = 44.1%) and basic science journals (M = 19.1%), respectively (p = .0003; p = .006). Noninternational journals (M = 23.0%) had a higher mean SoC article percentage than international journals (M = 13.2%), which approached but did not reach significance (p = .052).

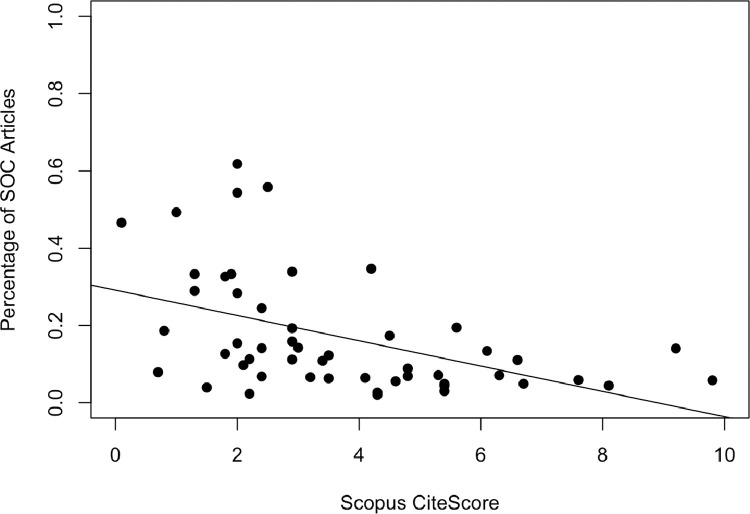

Skin of color–relevant articles and Scopus ranking analysis

To evaluate the relationship between Scopus ranking measures and the total percentage of articles on SoC, we divided journals based on their Scopus CiteScore. After excluding one journal that did not have Scopus information, we labeled the top 26 Scopus CiteScore journals as high and the bottom 25 Scopus CiteScore journals as low. An independent t test showed that journals in the lower half of Scopus CiteScores had a significantly greater percentage of articles on SoC (t = -5.140; p = .0002). A Spearman's correlation was also conducted to assess the relationship between the total percentage of articles on SoC and Scopus CiteScore and Scopus Percentile, two measures of Scopus rank. There was a moderate negative correlation between SoC percentage and Scopus CiteScore, which was statistically significant (rs = –0.33; p = .00436; Fig. 4). Similarly, there was a statistically significant moderate negative correlation between SoC percentage and Scopus Percentile (rs = –0.382; p = .005).

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot of Scopus CiteScore versus percentage of articles on skin of color (all journals).

Discussion

Journal category classification

We stratified by SoC population majority country to understand the percentage of diverse publications from SoC countries versus non-SoC countries. This is important because the effort for SoC countries to include patients with SoC would potentially be different from those efforts in non-SoC countries. The lack of diversity is probably most apparent and most urgent in non-SoC countries, where the majority of patients does not lead to a high percentage of publications on SoC. Journals were stratified by scientific versus clinical focus to better elucidate the basic science and clinical research dedication to SoC. Our findings suggest that SoC content is more prevalent within clinical research compared with basic science research. Given the foundational nature of basic science research, it is important that diversity and inclusion begin at the basic science level and are reinforced by epidemiological and larger clinical studies with diverse patient cohorts so that future research results are both pertinent to and reflective of true, diverse patient populations.

Skin of color relevance

To understand the dedication of each dermatology journal to SoC, journals were examined using the criteria we developed to identify SoC content. Journals were then ranked by the percentage of articles on SoC published. Of note, the percentage of articles on SoC varied greatly across journals, with a mean of 16.8%. No standard has been previously set with regard to establishing an appropriate amount of SoC content to be included in dermatology journal issues for comparison. Perhaps predictably, SoC countries published much higher percentages of articles on SoC compared with non-SoC countries. However, many non-SoC countries have large patient populations with SoC; thus, such countries must continue to investigate and publish any dermatological disparities associated with underrepresented populations of SoC to provide comprehensive care to diverse patient populations.

Of note, Clinics in Dermatology and Cutis are two of the journals surveyed that have implemented initiatives to devote a portion of their publications to the topic of SoC. Clinics in Dermatology dedicated one issue per year as a SoC issue, and Cutis designated an SoC section in each issue, yet Clinics in Dermatology was well below the 16.8% average in terms of proportion of articles on SoC. Clinics in Dermatology had 6.88% articles on SoC; however, the vast majority of those articles were in the dedicated yearly issue, and the journal published almost no articles related to SoC on a regular basis outside the dedicated issue. Although the yearly issue increases the overall number of articles on SoC published, this also separates the articles from the journal's other articles and may make them less accessible to those who are not actively seeking out publications on SoC. Cutis’ SoC section in each issue is a promising idea and led to 132 publications on SoC, accounting for 18.62% of the journal's total articles over the past 3 years. Both journals’ initiatives are a starting point and should be expanded and improved upon. Based on our findings, we recommend that journals strive to meet a minimum quota of 16.8% articles on SoC per issue, which can be supplemented with dedicated yearly or special-edition issues. Including ≥16.8% SoC content will help promote equitable dermatological care for our diverse patient population.

Skin of color article tiers

The vast majority of SoC-related publications in our study were published in SoC countries, while a significantly lower percentage of these publications came from non-SoC countries (tier 1B: 61.88% vs. tier 1E: 12.07%). We believe that most articles fell in the tier 1B category because tier 1B was the most broadly inclusive criteria, in that it included both articles in which the title mentioned an SoC country or continent in addition to all case reports in which the authors came from an SoC country. Additionally, SoC countries by definition have a predominant population with SoC; thus, an SOC country is expected to include patients with SoC in their clinical trials and case reports.

Tier 1D, which focuses primarily on diversity and inclusion, had the lowest percent of articles (0.55%). Although tier 1D articles made up the lowest number of articles, a study comparing the number of dermatology publications on diversity to other specialties from January 2008 to July 2019 found that dermatology had the greatest number of publications focused on diversity compared with other specialties (Bray et al., 2020). The increase in publications seen over the past 4 years in this 2020 study may be due to the amplified emphasis on diversity and cultural competence in dermatology and the racial unrest plaguing the United States in recent years (Bray et al., 2020). This suggests that, although more articles focusing on diversity and inclusion within the field of dermatology are necessary, dermatology is setting an excellent example for other medical specialties because increasing diversity in the workforce is imperative to improve both access and outcomes for underrepresented patients with SoC (Bray et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2016).

The percent of tier 2 articles focusing on diseases highly pertinent to patients with SoC due to skin pigment and hair curl pattern was significantly lower than the percent of tier 1 articles. Although this is expected given the breadth of subcategories included in tier 1, this value is still quite low. This may be due to the decreased access to dermatological care in the SoC community, leading to limited research dedicated to topics commonly affecting patients with SoC.

Geographical origin of articles on skin of color and patient cohorts

Of all the non-SoC continents, North America had the greatest number of populations with SoC (16.61%) compared with Europe (4.99%) and Oceania (0.26%). When focusing on the data from North America outlined in Figure 3, it was particularly heartening to see that the majority of articles on SoC (48.6%) focused on historically underserved populations with SoC: Blacks (33.94%) and Latinos (14.66%). The diverse array of patients with SoC represented in the multiple and/or unspecified category is encouraging because this suggests that studies are including diverse patient cohorts that may reflect local demographics.

Skin of color-relevant articles and Scopus ranking analysis

Interestingly, there was a moderately negative relationship between two measures of Scopus rank (Scopus CiteScore and Scopus Percentile) and the percentage of publications on SoC. This suggests that from 2018 to 2020, higher-ranked journals tended to publish a smaller proportion of articles on SoC compared with lower-ranked journals. If journals publishing the highest proportion of articles on SoC are cited less frequently, research on SoC may be less widely disseminated and thus SoC topics less visible in the dermatology literature.

Another particularly surprising observation from this study was the large number of case reports featuring patients with SoC. When factoring in the number of case reports focusing on patients with SoC, journals like Cutis (5.08%-18.62%), Pediatric Dermatology (4.52%-28.36%), and Contact Dermatitis (4.19%-12.26%) experienced significant increases in their percentage of publications on SoC. If we had not surveyed the abstracts of all case reports published, this is a finding that would likely have been overlooked. It is likely that there were more case reports that featured patients with SoC but were missed due to race not being specified and/or images being inaccessible. Journals such as Annals of Dermatology that featured a thumbnail image preview for all publications likely were ranked highly because missing a patient of color was less likely owing to the availability of preview images for all articles. Additionally, to promote equity and inclusion within the dermatological literature, we recommend that any publication featuring a person with SoC use the keyword “skin of color” to help readers better identify literature that could aid in the treatment of patients with SoC.

Study limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. We intentionally limited our tier 2 criteria to include diseases that commonly affect patients with SoC due to the pigmentation of their skin or the curl pattern of their hair. However, in doing so, we may have failed to capture other articles on dermatological conditions that are particularly relevant to people with SoC, such as discoid lupus, hidradenitis suppurativa, atopic dermatitis, and sarcoidosis. Furthermore, case reports that did not provide race/ethnicity demographic information or include a photo of a patient with SoC were not included and may have resulted in further uncaptured articles. Similarly, it is plausible that in including case reports with most authors from an SoC country in tier 1B, we are overcalculating the number of case reports focused on patients with SoC, and, although unlikely, it is possible that a case report from an African country featured a White patient.

Additionally, our criteria included nonoriginal articles (e.g., CME, letters from the editor, corrections, and retractions), which may have inflated the total number of articles and resulted in a lower percentage of articles on SoC. Alternatively, we included case series that presented one patient with SoC even if the remainder or majority of cases in the series were non-SoC to ensure that we captured all SoC-relevant publications. Finally, similar to how including race/ethnicity in clinical patient presentations is becoming increasingly discouraged (Acquaviva and Mintz, 2010), it is possible that authors are intentionally withholding race/ethnicity from their case presentations and that some relevant studies were thus uncaptured based on our criteria. With respect to the complexity of this limitation, we encourage practitioners and researchers to include Fitzpatrick skin type when presenting dermatology patients clinically and within the literature to avoid practicing race-based medicine, while still acknowledging and appreciating the inherent biological differences found in different skin colors (Taylor, 2002).

Conclusion

The dermatological literature is one of the key sources of information for treating patients with SoC. The results of this study document the current standing of the dermatological literature with respect to publishing SoC-relevant content. Our findings suggest that the percentage of overall publications relevant to SoC is quite low, and higher-ranked journals tended to publish a smaller proportion of articles on SoC compared with lower-ranked journals.

Our research highlights the areas of greatest need and encourages the inclusion and reporting of diverse patient cohorts in future dermatological publications. Based on our findings, we outline our specific recommendations:

-

1.

We encourage journal editors to use the criteria that we developed to evaluate submissions for content on SoC and to provide guidance for publication invitations that are dedicated to SoC topics, aiming for at least 16.8% SoC-relevant content in each issue.

-

2.

Given that dedicating one issue or a section of each issue alone has not been shown to result in a large proportion of SoC-relevant articles, we recommend that journals publish special editions on SoC only in addition to including at least 16.8% SoC-relevant articles in each issue.

-

3.

We encourage high-impact journals to publish more SoC-relevant content to increase accessibility to SoC-relevant articles within the dermatological literature.

-

4.

To promote equity and inclusion within the dermatological literature, we recommend that any publication featuring a person with SoC use the keyword “skin of color” to help readers better identify literature that could aid in the treatment of SOC.

-

5.

We encourage practitioners and researchers to include Fitzpatrick skin type when presenting dermatology patients clinically and within the literature to avoid practicing race-based medicine, while still acknowledging and appreciating the inherent biological differences found in different skin colors. The authors recognize that this is a misappropriation of Fitzpatrick skin type, but to date, there is no better metric that allows us to describe different skin colors. We hope that this piece will encourage the American Academy of Dermatology to dedicate a task force focused on creating such a metric.

We hope that the recommendations developed from this study will advance the field of dermatology in its continuous and noteworthy efforts to become a more inclusive and diverse specialty and to provide the highest quality of care to all patients, regardless of skin type and racial and ethnic background.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article. Dr. Jenny E. Murase has participated in advisory boards for Genzyme/Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Dermira, and UCB, as well as disease statement management talks for Regeneron and UCB. She also provided dermatologic consulting services for UpToDate.

Funding

None.

Study approval

The author(s) confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

References

- Acquaviva KD, Mintz M. Perspective: Are we teaching racial profiling? The dangers of subjective determinations of race and ethnicity in case presentations. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):702–705. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d296c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: An updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):194–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JK, McMichael AJ, Huang WW, Feldman SR. Publication rates on the topic of racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology versus other specialties. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(3):13030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buster KJ, Yang L, Elmets CA. Are dermatologists confident in treating skin disease in African-Americans? J Invest Dermatol. 2011:35. [Google Scholar]

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M, Bae GH, Khosravi H, Huang SJ. Changes in sex and racial diversity in academic dermatology faculty over 20 years. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(6):1252–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: Biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 Suppl Understanding):S41–S62. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]