Abstract

Choosing spermatozoa with an optimum fertilizing potential is one of the major challenges in assisted reproductive technologies (ART). This selection is mainly based on semen parameters, but the addition of molecular approaches could allow a more functional evaluation. To this aim, we used sixteen fresh sperm samples from patients undergoing ART for male infertility and classified them in the high- and poor-quality groups, on the basis of their morphology at high magnification. Then, using a DNA sequencing method, we analyzed the spermatozoa methylome to identify genes that were differentially methylated. By Gene Ontology and protein–protein interaction network analyses, we defined candidate genes mainly implicated in cell motility, calcium reabsorption, and signaling pathways as well as transmembrane transport. RT-qPCR of high- and poor-quality sperm samples allowed showing that the expression of some genes, such as AURKA, HDAC4, CFAP46, SPATA18, CACNA1C, CACNA1H, CARHSP1, CCDC60, DNAH2, and CDC88B, have different expression levels according to sperm morphology. In conclusion, the present study shows a strong correlation between morphology and gene expression in the spermatozoa and provides a biomarker panel for sperm analysis during ART and a new tool to explore male infertility.

1. Introduction

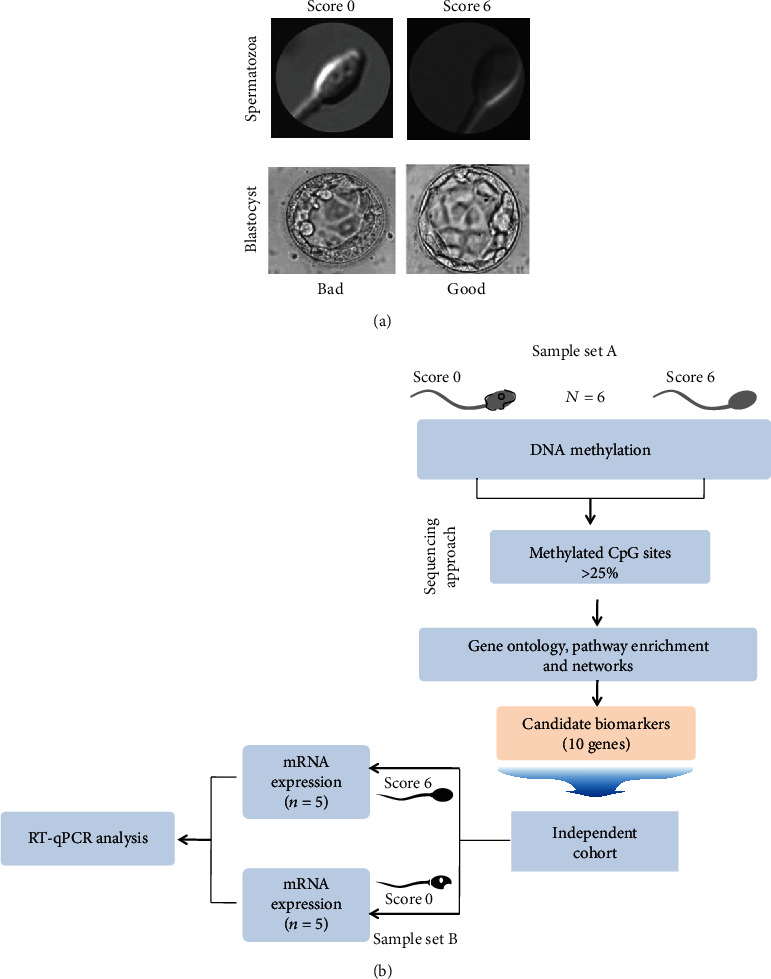

Male infertility affects roughly 30 million men worldwide and contributes to 50% of all infertility cases (15% of the 60 to 80 million couples trying to conceive) [1, 2]. Different causes of male infertility have been identified (e.g., hormonal, mechanical, postinfectious, chromosomal, and genetic) [3, 4], but in about 50% of cases, the origin remains unknown. Routine sperm analysis includes the evaluation of sperm volume, pH, concentration, motility, vitality, and morphology [5]. The current treatment for male infertility associated with abnormal sperm parameters is fertilization by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [6] after selection of motile and morphologically normal spermatozoa. Indeed, the injection of individual sperm cells with abnormal or subnormal morphology can reduce fertilization and implantation rates [7]. However, some spermatozoa that appear morphologically normal at ×200 or ×400 magnification present abnormalities when examined at higher magnification (×6100). Therefore, in 2009, we introduced a new classification of living spermatozoa with a scoring scale ranging from 0 to 6 based on strict morphologic criteria [8]. Briefly, the spermatozoa with a total score of 6 points display normal head shape (normal head, with symmetrical nuclear no extrusion and/or no invagination of the nuclear membrane = 2 points) without any vacuole (3 points), and normal base (the third inferior part of the sperm head to the neck where the centrosome is localized = 1 point). The spermatozoa with a total score 0 (0 point) display head abnormalities, vacuoles, and abnormal base (Figure 1(a)). Fertilization rates and number of good-quality blastocysts at day 5 (according to Gardner's classification [9]; Figure 1(a)) are significantly higher when using the spermatozoa with score 6 (6 points) [8, 10]. Similarly, other studies showed higher implantation and pregnancy rates and lower miscarriage rates when performing ICSI with the spermatozoa of good morphology selected by microscopy analysis at high magnification [11, 12]. Moreover, a meta-analysis suggests an increased risk of birth defects in children conceived by ICSI compared with those born after in vitro fertilization (IVF) or spontaneous conception [13]. However, the rate of major malformations is significantly reduced when ICSI is performed after sperm selection at very high magnification [14, 15], highlighting the importance of sperm selection. In addition, the approaches currently used for sperm selection are still not fully adequate [16], emphasizing the need of a strategy that takes into account not only morphological features but also functional. For instance, genome alterations, chromatin structure, DNA fragmentation, and epigenetic profile (e.g., DNA and histone methylation patterns) of the sperm contribute to proper embryo development and healthy live birth [17]. The spermatozoa play a crucial role by delivering a novel epigenetic signature to the egg [18]. In previous studies, we evaluated the relationship between sperm head morphology at high magnification and its chromatin/DNA content in sperm samples from men harboring a reciprocal or a Robertsonian translocation. However, we did not detect any relationship between high-magnification morphology and balanced/unbalanced chromosomal content [19, 20]. This could be related to the fact that in carriers of chromosomal rearrangements, all spermatozoa, and not only those with chromosomal unbalance, display an abnormal nuclear chromosomal architecture [21]. We also showed that score 0 spermatozoa are associated with high levels of sperm chromatin decondensation, but not with DNA fragmentation [22, 23]. Other studies showed a correlation between vacuole size and DNA fragmentation [24–31]. All these studies emphasize the evident correlation between sperm head morphology at very high magnification and its chromatin status [32] and highlight the heterogeneity of spermatozoa from the same ejaculate that consequently will not give the same outcome after oocyte fertilization. They carry the same genetic DNA information, but in a differently packaged chromatin with different degrees of compaction and possibly different degrees of protection against external microenvironment. Moreover, variations in the DNA/histone methylation profile among spermatozoa might have crucial consequences for gene expression and possibly for early embryo development and ART outcome [33, 34]. In agreement, we previously reported lower DNA methylation levels in the spermatozoa with score 6 than with score 0 from the same sample. This allows selecting the spermatozoa without abnormal DNA methylation levels and thus reducing the risk of birth defects [35]. It is generally accepted that the incidence of major malformations is lower after spontaneous conception than after ART [36]. All these data establish correlations between head morphology at high magnification and chromatin/DNA status and suggest that there may be also a link with gene expression.

Figure 1.

Study design. (a) Morphological criteria are used to score spermatozoa at high magnification (6100x) and to assess blastocyst quality under an inverted microscope. (A) Representative images of a spermatozoon with “score 0” (top) and the bad-quality blastocyst obtained by ICSI using this spermatozoon. (B) Representative images of a spermatozoon “score 6” and the good-quality blastocyst obtained. (b) Simplified flowchart of the strategy to identify candidate biomarkers of good-quality spermatozoa. DNA from sperm samples (n = 3 with “score 0” and n = 3 with “score 6”) is sequenced to identify an initial set of genes that are differentially methylated in spermatozoa with good (score 6) and poor (score 0) morphology. The correlation between the expression profiles of candidate genes and spermatozoon morphology is then evaluated by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using RNA from an independent set of sperm samples (n = 5 with “score 0” and n = 5 with “score 6”) from different patients with infertility.

The aim of the present study was to (i) compare the DNA methylation profile, assessed by whole-genome sequencing, in the spermatozoa classified according to their high-magnification morphology (score 6 versus score 0) to identify genes that are differentially methylated in these two categories and (ii) to compare the expression of some of these differentially methylated genes in the spermatozoa classified according to their morphology score (score 6 versus score 0). As coding transcripts contribute to the production, morphology, and function of viable human sperm, we hypothesized that their methylation pattern and expression levels in morphologically scored spermatozoa could be used as biomarkers to select high-quality sperm in term of ART outcome.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sample Collections and Sperm Parameters

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, the members of which are part of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Société d'andrologie de langue Française (IORG0010678). The study protocol was carried out in the ART Unit of the Drouot Laboratory, Paris, France. All participants signed an informed consent form before inclusion in the study. They were informed that after the clinical tests, the semen sample would be analyzed at high magnification and using molecular biology approaches. The patients' confidentiality was ensured by data anonymization before analysis. This analysis did not lead to any additional costs for the patients and did not affect their treatment in any way.

For this study, 16 couples were enrolled in our IVF unit for different (female or/and male) infertility problems. In these 16 couples, men were divided in two groups on the basis of the percentage of sperm with score 6 (good sperm quality) and score 0 (bad sperm quality): (i) one group of men with good sperm quality (5%-15% of spermatozoa with score 6 and less than 30% of spermatozoa with score 0). In an internal study of 1000 ejaculates with good sperm parameters, not more than 15% of spermatozoa had score 6; (ii) the other group of men with bad sperm quality (90% of spermatozoa with score 0 and 0% with score 6).

The analysis concerned 16 fresh sperm samples from 16 men (39 ± 5.6 years) selected according to the sperm morphological scores: 6 samples (three with score 6 and three with score 0) were used for the DNA methylation analysis by whole-genome bisulfite sequencing to select candidate genes and 10 (five with score 6, and five with score 0) for the gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR. The parameters of these 16 samples are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Sperm Preparation

Motile spermatozoa were isolated and purified by bilayer concentration density gradient in conical tubes containing 45% and 90% of ISolate Sperm Separation Medium (Cat. no. 99264; Fujifilm Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA). Tubes were centrifuged at 300×g for 15 min. Then, the supernatant was discarded, and sperm pellets were washed in the modified Human Tubal Fluid (mHTF) medium (Cat. no. 90126; Fujifilm Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA) and centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min. Pellets were then resuspended in 500 μl mHTF medium, counted under a light microscope high magnification, and selected according to concentration of the score. All motile spermatozoa were sorted at high magnification (×6100) according to strict morphological criteria [5] combined with the previously described scoring scale. The 16 samples were frozen and stored at -80°C for DNA isolation.

2.3. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing and Methylation Analysis

The SeqCap Epi Enrichment System (ROCHE NimbleGene), a solution-based capture method, was chosen because it allows the enrichment of bisulfite-converted DNA in a single tube and sequenced on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina) according to manufacturing protocol. Raw data were mapped to the human reference genome (Homo sapiens genome build GRCh37 (hg19) with the BSMAP (v 2.89) software, using the methylKit R package [37]. Potential differentially methylated regions were identified with strict filters (q value < 0.01 and methylation difference percentage > 25%).

2.4. Gene Ontology Analysis and Functional Enrichment

Targeted gene function was assessed with Gene Ontology (GO), the PANTHER tool (http://pantherdb.org), and the Genomatrix software suite (Genomatix Software GmbH, Munich, Germany). The OmicsNet tool was used for network creation and visual exploration [38]. Data (differentially methylated genes) were integrated with molecular interactions using the ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) software application (http://www.ingenuity.com). Each gene symbol was mapped to the corresponding gene object in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Gene networks were algorithmically generated based on their connectivity and assigned a score. The score is a numerical value used to rank networks according to their relevance to the genes in the input dataset but may not be an indication of the network quality or significance. The score takes into account the number of focus genes in the network and the network size to approximate how relevant the network is to the original list of focus genes.

2.5. RNA Isolation and Relative Gene Expression Analysis

RNA was extracted from sperm samples with the miRNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA templates were prepared by reverse transcription (RT) using the ReadyScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) starting from 100 ng total RNA following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA templates were 1 : 11 diluted in 0.1x TE before analysis by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). Two housekeeping genes were used as reference: β2 microglobulin (B2M) and protamine 1 (PRM1). The M values (i.e., the average gene expression stability) [39] were determined, and the M value cut-off for the reference genes was 0.25. The following ten genes (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay ID number) were selected for RT-qPCR analysis based on their potential function: AURKA (Hs01582072_m1), HDAC4 (Hs01041648_m1), SPATA18 (Hs01102818_m1), CCDC60 (Hs00905317_m1), CACNA1H (Hs01103527_m1), CCDC88B (Hs00989955_g1), DNAH2 (Hs01044842_m1), CACNA1C (Hs00167681_m1), CARHSP1 (Hs00183933_m1), CFAP46 (Hs00929098_m1), PRM1 (Hs00358158_g1), and B2M (Hs00187842_m1). All qPCR assays were carried out in 384-well plates in three technical replicates in 10 μl final reaction volume using the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (2x) and the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 20 seconds (enzyme activation), followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 3 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension with fluorescence measurement. The relative gene expression was calculated with the 2-ΔΔCp method [40]. Cp indicates the cycle threshold, i.e., the fractional cycle number when the fluorescent signal reaches the detection threshold. The normalized ΔCp value of each sample was calculated using the reference gene values with a Cp variation < 1 in all experiments.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Unless otherwise indicated, differences were considered significant when the unpaired two-tailed Bonferroni-adjusted p value (Q) was < 0.05. Fisher's exact test and unadjusted p values were used for the IPA and motif enrichment analyses and the Mann–Whitney test [41] to compare the RT-qPCR results (Cp values), in order to avoid reduction in variance and introducing dependence among the normalized values.

3. Results

The objective of the present study was to identify molecular biomarkers in human spermatozoa that correlate with a good morphological aspect (i.e., score = 6). To this aim, gene methylation/expression analyses were performed using a combination of DNA-seq and RT-qPCR methods (Figure 1(b)). This allowed identifying ten genes, the expression level of which was correlated with spermatozoa morphology. These genes might be used as biomarkers of sperm quality or as pharmacological targets to improve the fertilization potential of spermatozoa.

3.1. Identification of Regions with Differential DNA Methylation in Spermatozoa with Good and Poor Morphology by Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing

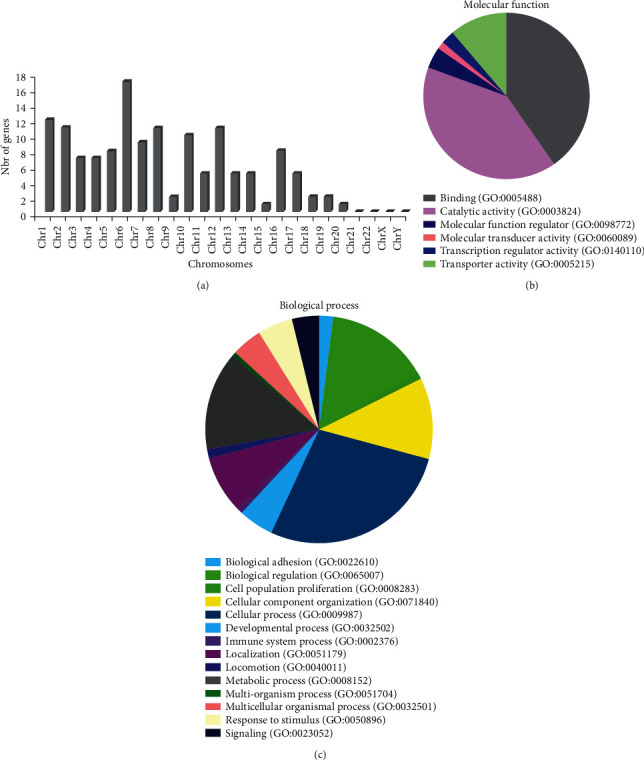

To determine the global DNA methylation profile of six human sperm samples (three with high-magnification morphology score 0 and three with score 6), first bisulfate conversion, DNA-sequencing analysis, and CpG methylation profiling at the single-base resolution were performed (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). The genome-wide DNA methylation analysis identified 17,544 methylation-variable positions with genome-wide significance (adjusted p < 0.05). By using a strict filter (q value < 0.01 and percentage of methylation difference between the score 0 and score 6 samples >25%) to detect potentially differentially methylated regions, 746 positions were identified, including 138 known genes (Supplementary Table S2) and 308 genomic loci. Differentially methylated CpG bases were detected in all chromosomes, except chromosomes 21, 22, X, and Y (Figure 2(a)). The list of differentially methylated genes (sperm methylation signature) included genes encoding proteins associated with sperm motility, flagellar assembly, and spermatogenesis (DNAH2, CFAP46, and SPATA18), coiled-coil domain (CCDC88B and CCDC60), many channel-mediating calcium and sodium entry (CACNA1C, CACNA1H, CACNA2D4, TRPM3, SCN8A, and ANO2), calcium-regulated proteins (CARHSP1, ATXBP5, and SMOC2), histones (HDAC4, JMJD1C, and SMYD3), E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (ZNFR4, CHFR, PARK2, MARCH6, SPSB1, and HECTD2), linked to the cytoskeleton molecular organization (SNTG2, PHACTR1, SYNE1, and DLGAP2), transporter activity (SLC2A1, SLC18A8, SLC35F3, and CLCN7), ATPase activity (ATP6V0A4, PFKP, CARKD, and NKAIN3), zinc finger proteins (ZNF239, ZFYVE28, and DPF3), transmembrane proteins (TMEM117, TMTC4, and LRTM2), transcription factors (SOX6 and GATA4), and genes associated with mitochondria (NDUFB4, TOP1MT, SDHA, and ADHFE1).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the differentially methylated genes. (a) Distribution of differentially methylated genes between score 0 and score 6 sperm samples in the human chromosomes. (b) Gene Ontology (GO) classification of the differentially methylated genes in molecular function categories. (c) GO classification of the differentially methylated genes in biological process categories. The two pie charts were generated with the PANTHER tool.

3.2. Functional Properties of the Genes Enriched in the Sperm Methylation Signature

Gene ontology (GO) annotations were used to identify the potential biological processes and functional properties of the genes included in the sperm methylation signature (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)). The top “biological processes” terms were locomotion (GO: 0040011), cellular process (GO: 0009987), cell population proliferation (GO: 0008283), metabolic process (GO: 0008152), cellular component organization (GO: 0071840), and response to stimulus (GO: 0050896). The most enriched “molecular function” terms were binding (GO: 0005488), catalytic activity (GO: 0003824), and transporters (GO: 0005215). The genes of the sperm methylation signature were also analyzed using the Genomatix Genome Analyzer to identify the most relevant molecular and cellular functions (Table 1). The functional categories identified were highly relevant to sperm function, such as calcium channel activity (p = 1.12E−03), enzyme binding (p = 2.56E−03), ATP-dependent microtubule motor activity (p = 3.41E−03), protein binding (p = 8.37E−03), passive transmembrane transporter activity (p = 8.64E−03), and cytoskeletal protein binding (p = 8.66E−03).

Table 1.

Functional classification of the methylated genes using Genomatix software.

| Functional categories | GO term ID | p value | List of genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium channel activity | GO:0005262 | 1.12E − 03 | CACNA1H, CACNA1C, CACNA2D4, TRPM3, JPH3 |

| Dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein mannosyltransferase activity | GO:0004169 | 1.37E − 03 | TMTC4, POMT2 |

| Enzyme binding | GO:0019899 | 2.56E − 03 | SLC9A3R2, ATP6V0A4, EXOC2, FRS2, EZR, CARHSP1, STXBP5, PHACTR1, CNST, RALGPS2, SH3BP4, AURKA, SMYD3, PRKN, SLC2A1, DENND3, RASGEF1A, JAKMIP3, MARCHF6, HDAC4, SYNE1, ARFGEF3, PSD3, MCF2L, GATA4 |

| Coreceptor activity | GO:0015026 | 2.83E − 03 | GPC6, CD80, RGMA |

| ATP-dependent microtubule motor activity | GO:1990939 | 3.41E − 03 | KIF26A, DNAH2, KIF17 |

| Isomerase activity | GO:0016853 | 4.29E − 03 | TXNDC5, NAXD, QSOX1, TOP1MT, PDIA6 |

| Ubiquitin-specific protease binding | GO:1990381 | 5.61E − 03 | PRKN, MARCHF6 |

| Tubulin binding | GO:0015631 | 5.95E − 03 | KIF26A, EZR, CCDC88B, TBCD, PRKN, JAKMIP3, KIF17 |

| Oxidoreductase activity, acting on a sulfur group of donors | GO:0016667 | 6.09E − 03 | QSOX1, PDIA6, NXN |

| ARF guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity | GO:0005086 | 6.25E − 03 | ARFGEF3, PSD3 |

| GTPase binding | GO:0051020 | 7.52E − 03 | EXOC2, STXBP5, RALGPS2, SH3BP4, DENND3, RASGEF1A, ARFGEF3, PSD3, MCF2L |

| Protein binding | GO:0005515 | 8.37E − 03 | TRIM2, CACNA1H, SPSB1, KIF26A, SLC9A3R2, ESPNL, AUTS2, TXNDC5, CACNA1C, TCAF2, ZFYVE28, SPON2, ATP6V0A4, MAD1L1, EXOC2, FRS2, DPF3, ERGIC1, SPATA18, CUX1, EZR, COLEC11, RPA3, GPC6, AHRR, MFAP3L, CARHSP1, DNAH2, ZNRF4, PFKP, BANP, CCDC88B, SCN8A, STXBP5, PHACTR1, CNST, RALGPS2, NAXD, TBCD, PRKG1, JMJD1C, USP10, LRTM2, ST8SIA5, CCDC60, DLGAP2, SH3BP4, AURKA, TG, LTBP2, SMYD3, PRKN, COL4A2, SLC2A1, IGHMBP2, DENND3, SDHA, HMGB4, CHFR, MPHOSPH10, SNTG2, RASGEF1A, JAKMIP3, PDIA6, PHLDB2, MARCHF6, FRK, HDAC4, TBL3, TLE1, SYNE1, ARFGEF3, PSD3, KIF17, ZNF239, FOXP4, MCF2L, FSTL4, ANO2, SOX6, GATA4, AGPAT4, CD80, SPPL2B, TERT, DAB1, RGMA |

| Passive transmembrane transporter activity | GO:0022803 | 8.64E − 03 | CACNA1H, CACNA1C, CLCN7, CACNA2D4, SCN8A, TRPM3, JPH3, ANO2 |

| Cytoskeletal protein binding | GO:0008092 | 8.66E − 03 | KIF26A, ESPNL, CACNA1C, EZR, CCDC88B, STXBP5, PHACTR1, TBCD, PRKN, SNTG2, JAKMIP3, SYNE1, KIF17 |

3.3. Regulatory Roles and Potential Networks Associated with the Identified Genes

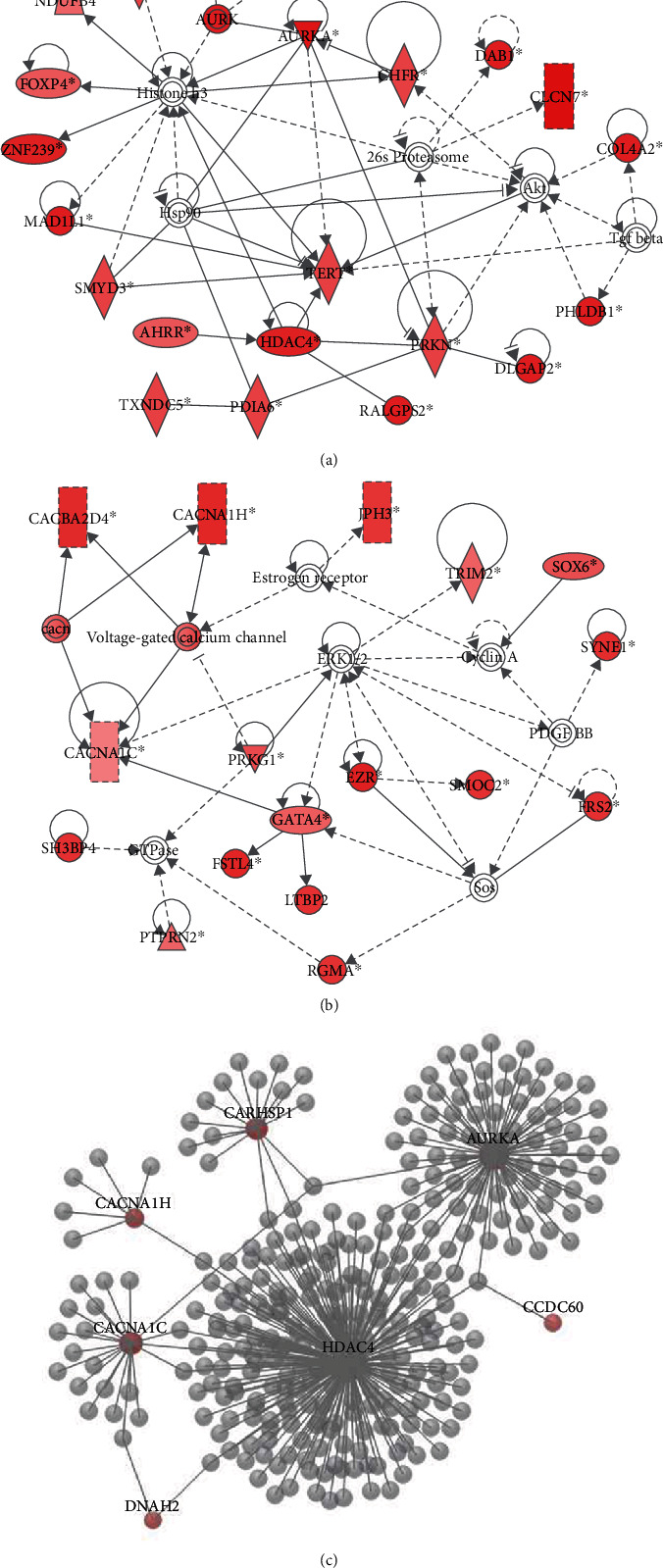

Then, IPA was used to explore the putative functions of genes and networks of the sperm methylation signature. This analysis identified two top networks (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Each network showed interactions with major signaling pathway molecules, including histones, AKT, ERK1/2, and cyclins. Functions associated with these networks included cell cycle, cellular assembly and organization, and organ development and function. The aurora kinase A AURKA-centered network (Figure 3(a)) functionally interacted with spermatogenesis-associated 18 (SPATA18), CHFR, INSYN2A, PRKN, TERT, and histones, forming a tightly connected network. Histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) also was related to histones and displayed direct interaction with TERT, AHRR, PRKN, and RALGPS2. The second network (Figure 3(b)) showed interactions with voltage-gated calcium channel genes (CACNA1H, CACNA1C, and CACNA2D4) and also between calcium channel components and PRKG1, GATA4, and ERK1/2, suggesting an operative role of channels that mediate calcium entry in the spermatozoa. To establish functional links among these molecules, the protein-protein interaction network was constructed. It showed that AURKA was highly connected with HDAC4 (Figure 3(c)) and gave results very similar to those obtained by the IPA function and pathway analysis. Dynein axonemal heavy chain 2 (DNAH2) and coiled-coil domain containing 60 (CCDC60), which are involved in ciliogenesis, were included in this network. In addition, most of the nodes forming this network were associated with proteins implicated in sperm motility and flagellar assembly (for instance, CACNA1C and CACNA1H) and calcium regulated heat stable protein 1 (CARHSP1).

Figure 3.

Top-ranked functional networks of the differentially methylated genes. (a) Top network identified by ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of differentially methylated genes related to cell cycle, cellular assembly, and organization. (b) Top network identified by IPA of differentially methylated genes related to organ development and function. Colored nodes indicate differentially methylated genes. Noncolored nodes were proposed by IPA and suggest potential targets functionally coordinated with the differentially methylated genes. Dashed lines represent indirect relationships, and solid lines indicate direct molecular interactions. In each network, edge types are indicatives: a line without arrowhead indicates binding only; a line finishing with a vertical line indicates inhibition; a line with an arrowhead indicates ‘acts on.' (c) Protein-protein interaction network of selected differentially methylated genes. Using the OmicsNet database, six genes (AURKA, HDAC4, CARHSP1, CACNA1H, CACNA1C, and DNAH2) were used to construct a top-ranked functional protein-protein interaction network.

3.4. Relationship between Gene Expression Pattern and Sperm Morphology

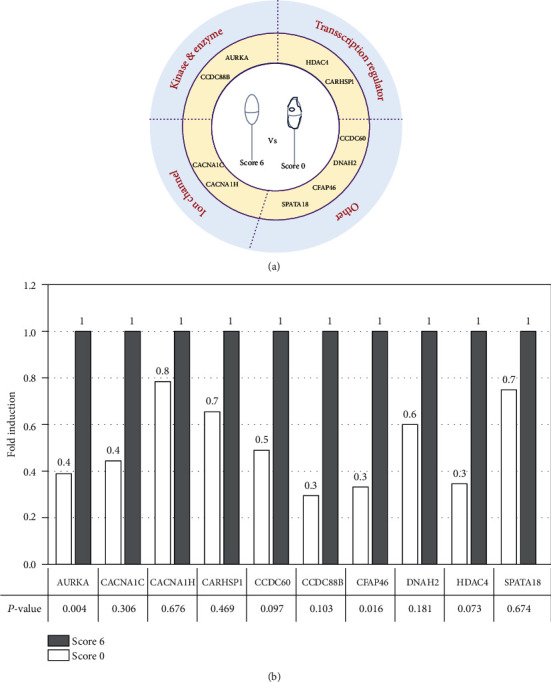

Then, to evaluate the relationship between gene expression and sperm morphology, the expression of ten genes included in the sperm methylation signature (HDAC4, AURKA, CFAP46, DNAH2, CCDC88B, CACNA1C, CACNA1H, SPATA18, and CARHSP1) was quantified in 10 sperm samples with poor and good morphology (n = 5 with score 0 and n = 5 with score 6, respectively) (Figure 1(b)). These genes were chosen because they participate in the regulatory mechanisms of physiological processes during spermatogenesis, such as cell cycle, locomotion and cell motility, cellular assembly and organization, and the calcium activation pathways, according to the IPA (Figure 4(a)). To increase the robustness of the RT-qPCR experiments, two reference genes (B2M and PRM1) were used to obtain the average expression stability of the reference genes using the M value method [39]. The two genes had M values < 0.2. The RT-qPCR results showed that the expression level of the 10 genes was higher in the morphologically good samples than in the morphologically poor samples (Figure 4(b)). This suggests that their expression is positively correlated with sperm morphology and that these genes might be candidate biomarkers of sperm quality and health to be used during the selection of spermatozoa for ICSI.

Figure 4.

Relative expression level of 10 genes that are differentially expressed in score 0 and score 6 spermatozoa. (a) Graphical representation of the gene types. (b) Gene expression was compared between score 0 (white) and score 6 (black; reference, set to 1) sperm samples by RT-qPCR analysis. p value were calculated with the Mann–Whitney test.

3.5. Expression in Various Human Tissues

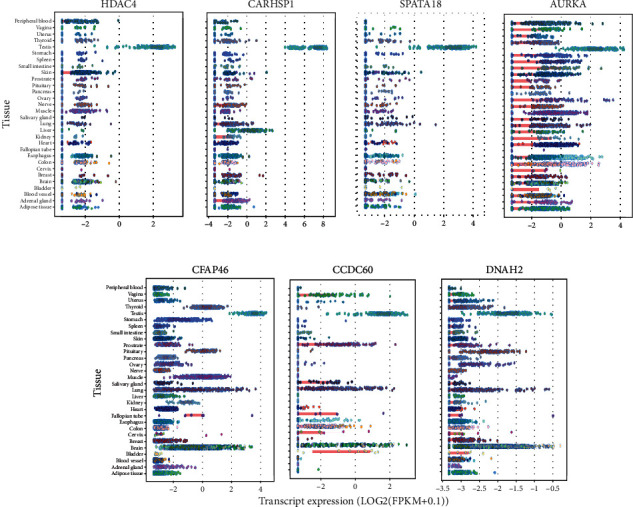

To determine whether these ten genes were testis-specific, their expression was analyzed in normal tissues using RNA-seq data (expressed as log reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM)) for 30 tissue types from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) repository [42, 43]. This analysis showed that HDAC4, CARHSP1, SPATA18, and AURKA were strongly expressed in testis tissue compared with other tissues (Figure 5). In contrast to HDAC4, CARHSP1, and SPATA18, AURKA is also highly expressed in the ovary, as well as in the lung, esophagus, and colon. CFAP46, CCDC60, and DNAH2 were strongly expressed in tissues that contain cilia, such as the testis, lung, and brain (Figure 5). The expression of CCDC88B and CACNA1H in the testis is rather low compared to most of the other tissues as shown in (Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, no difference in expression was observed for CACNA1C in the different tissue samples AURKA, HDAC4, and CARHSP1 could play a role during the maternal to embryonic genome transition and in embryonic genome activation [44]. Specifically, AURKA could be involved in cell division up to the embryonic genome activation. Future studies should determine whether alterations of AURKA and SPATA18 gene expressions affect human early embryo development.

Figure 5.

Expression profile of candidate genes in different human tissues. Expression values (in Log2 (RPKM)) of HDAC4, CARHSP1, SPATA18, AURKA, CCDC60, DNAH2, and CFAP46 in 30 tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) consortium. For each gene, the colored circle belonging to each tissue indicates the valid RPKM value of all samples in the tissue. RPKM: reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

4. Discussion

Male infertility is commonly associated with high rates of sperm DNA damage, and the quality of human sperm is one of the main determinants of ART success. Our previous studies focused on assessing the relationship between sperm head morphology and DNA methylation levels through detection of 5-methylcytosine residues by fluorescence microscopy [35]. Here, we used whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and methylation analysis to investigate the methylome of morphologically scored spermatozoa. First, we identified regions that are differentially methylated between score 6 and score 0 spermatozoa (good and poor morphology, respectively) and investigated their function and regulatory networks. We found that methylation differences varied among chromosomes. Chromosome 6 had the highest number of differentially methylated regions and chromosomes 21, 22, X, and Y had none. This might be related to the gene distributions in the different chromosomes. Additional studies are needed to understand the accurate mechanisms of epigenetic regulation.

Then, we investigated the relationship between the gene expression level and sperm morphology. We found that the expression of some genes with functions related to sperm motility, flagellar assembly, and spermatogenesis was affected, including spermatogenesis-associated 18 (SPATA18), cilia- and flagella-associated protein 46 (CFAP46), and dynein axonemal heavy chain 2 (DNAH2). SPATA18 transcription in mammalian seminiferous tubules is induced by p53 [45] that is implicated in meiosis during spermatogenesis and guarantees the appropriate quality of mature spermatozoa [46, 47]. SPATA18 transcriptional regulation is necessary for spermatogenesis progression [45]. CFAP46 is part of the central apparatus of the cilium microtubule-based cytoskeleton. In humans, alterations of cilia- and flagella-associated protein family genes (e.g., CFAP43, CFAP44, and CFAP251) have been associated with the multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella (MMAF) syndrome [48]. DNAH2 is essential for human ciliary function. The spermatozoa from patients with MMAF and DNAH2 mutations display loss of motility [49], and patients with DNAH2 gene variations show defects of the MMAF phenotype [50]. Although CFAP46 and DNAH2 are expressed primarily in testis, here, we found that they are expressed also in other tissues, such as the brain and lungs. Several studies have characterized ion channels in the sperm from the fertile and unfertile patients [51]. It has become clear that ion channel activities play a key role in sperm function. Our sequencing data revealed that many genes encoding channels that mediate calcium and sodium entry are differentially methylated in spermatozoa with good and poor morphology. Moreover, the genes encoding voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit alpha-1C and calcium channel subunit alpha-1H (CACNA1C and CACNA1H) and calcium-responsive heat-stable protein 1 (CARHSP1) are more strongly expressed in score 6 than in score 0 spermatozoa. The implication of CACNA1C and CACNA1H in many calcium-dependent processes (e.g., muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, cell motility, and cell death) and their association with different diseases [52–54] suggest that their dysfunction could significantly affect sperm function. The importance of the RNA-binding protein CARHSP1 (also called CRHSP-24) during spermatogenesis was previously reported in mice [55].

Our study also showed that the genes encoding aurora kinase A (AURKA) and histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) are differentially expressed in score 6 and score 0 spermatozoa and that they represent excellent candidate biomarkers. Aurora kinase A is implicated in the proper execution of various mitotic events, including centrosome maturation, separation, spindle formation, and mitotic entry [56]. Besides its function in dividing spermatogonia and spermatocytes, this kinase is involved in sperm development and motility, which are critical for male fertility [57]. Its activation involves many proteins that together affect primary cilia disassembly [58]. HDAC4, a class II histone deacetylase, acts by forming large multiprotein complexes and plays an important role in transcriptional regulation, cell cycle progression, and developmental events. HDAC6 (another class II histone deacetylase) promotes microtubule destabilization in vivo [59] and is phosphorylated in the presence of aurora kinase A [58]. Additionally, aurora kinase A activation in ciliary disassembly requires its interaction with Ca(2+) and calmodulin [60], leading to transient Ca2+ signals in ciliary disassembly via the AURKA–HDAC6 signaling cascade [60, 61].

Remarkably, analysis of the AURKA interactome highlighted interactions with HDAC4 and connection with calcium channel subunit alpha (CACNA1C and CACNA1H). This suggests that a defect in any components of the calcium flux- aurora kinase A-histone deacetylase signaling cascade might impact sperm function and consequently fertility. Additional research is required to understand the importance of AURKA, HDAC4, and channel-mediating calcium entry in spermatogenesis. Aurora kinase A is also implicated in the establishment of the achromatic spindle allowing chromosome migration for cell division during embryo development [62, 63]. This could explain the impaired development (slow kinetic, fragmented embryos with irregular blastomeres, and absence of expanded blastocysts) after ICSI with scores 0 spermatozoa. Moreover, we found that AURKA expression is higher during the early embryo cleavage stages, but then declines between the 4-cell and 8-cell stage, concomitantly with maternal genome degradation and embryonic genome activation. This suggests that AURKA might influence the maternal-embryonic genome transition. Future studies should determine whether altered AURKA expression in the spermatozoa affects human early embryonic development.

5. Conclusion

We found a significant differential DNA methylation and expression of many genes in sperm with poor and good morphology obtained from patients referred for ICSI for male infertility. This study provides a new panel of genes (AURKA, HDAC4, CACNA1C, CACNA1H, CARHSP1, CFAP46, SPATA18, CCDC60, DNAH2, and CDC88B) that could be used as biomarkers to assess sperm quality. Despite the study limitations (i.e., low sample size and the fact that samples used for DNA and RNA sequencing were not from the same patient), we identified a set of genes that might be candidate biomarkers of sperm morphology and new drug targets for the treatment of spermatozoa defect. Before any routine use, a large cohort of sperm samples should be analyzed by high-magnification microscopy and RT-qPCR approaches. Our work suggests that rapid molecular analysis of few genes in sperm samples might contribute to the selection of good-quality spermatozoa and could avoid chaotic or abnormal early embryo development after ICSI. The envisioned use of the RT-qPCR-based transcriptomic analysis to identify the spermatozoa with good gene expression profiles is described in Supplementary Figure S2.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the patients for participating in this study. We would like to thank the ART team for their assistance during this study. We thank Dr. Fernando Sanchez Martin and Dr. Pascual Sanchez Martin (Seville University, Spain) for their advice.

Contributor Information

Nino Guy Cassuto, Email: guycassuto@labodrouot.com.

Said Assou, Email: said.assou@inserm.fr.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

N.G.C. conceived the study, performed experiments, wrote the paper, and supervised the study. D.P performed experiments and analyzed data. D.P., F.B., L.L., N.L., G.H., L.R., D.B., J.P.S., and A. R helped in writing the paper, editing, and data analysis. S.A. conceived the study, analyzed the data, supervised the study, and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 Sample collected and sperm parameters. Supplementary Table S2: list of differentially methylated genes (n = 138) between score 6 and score 0 sperm samples

Supplementary Figure S1: expression values (in Log2 (RPKM)) of CCDC88B, CACNA1H, and CACNA1C in 30 tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) consortium. Supplementary Figure S2: envisioned sperm test for male infertility in ART.

References

- 1.Agarwal A., Mulgund A., Hamada A., Chyatte M. R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reproductive biology and endocrinology . 2015;13(1):p. 37. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0032-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal A., Majzoub A., Parekh N., Henkel R. A schematic overview of the current status of male infertility practice. The world journal of men's health . 2020;38(3):308–322. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.190068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poongothai J., Gopenath T. S., Manonayaki S. Genetics of human male infertility. Singapore Medical Journal . 2009;50(4):336–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krausz C., Riera-Escamilla A. Genetics of male infertility. Nature Reviews. Urology . 2018;15(6):369–384. doi: 10.1038/s41585-018-0003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez-Álvarez J., Cano-Corres R., Fuentes-Arderiu X. A complement for the WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen (first edition, 2010) EJIFCC . 2012;23(3):103–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palermo G., Joris H., Devroey P., Van Steirteghem A. C. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. The Lancet . 1992;340(8810):17–18. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos A., Van De Velde H., Joris H., Verheyen G., Devroey P., Van Steirteghem A. Influence of individual sperm morphology on fertilization, embryo morphology, and pregnancy outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertility and Sterility . 2003;79(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassuto N. G., Bouret D., Plouchart J. M., et al. A new real-time morphology classification for human spermatozoa: a link for fertilization and improved embryo quality. Fertility and Sterility . 2009;92(5):1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner D. K., Surrey E., Minjarez D., Leitz A., Stevens J., Schoolcraft W. B. Single blastocyst transfer: a prospective randomized trial. Fertility and Sterility . 2004;81(3):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanderzwalmen P., Hiemer A., Rubner P., et al. Blastocyst development after sperm selection at high magnification is associated with size and number of nuclear vacuoles. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2008;17(5):617–627. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knez K., Tomazevic T., Zorn B., Vrtacnik-Bokal E., Virant-Klun I. Intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection improves development and quality of preimplantation embryos in teratozoospermia patients. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2012;25(2):168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greco E., Scarselli F., Fabozzi G., et al. Sperm vacuoles negatively affect outcomes in intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection in terms of pregnancy, implantation, and live-birth rates. Fertility and Sterility . 2013;100(2):379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen J., Jiang J., Ding C., et al. Birth defects in children conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility . 2012;97(6):1331–1337.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaspard O., Vanderzwalmen P., Wirleitner B., et al. Impact of high magnification sperm selection on neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics . 2018;35(6):1113–1121. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1167-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassuto N. G., Hazout A., Bouret D., et al. Low birth defects by deselecting abnormal spermatozoa before ICSI. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2014;28(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy Z. P., Liu J., Joris H., et al. The result of intracytoplasmic sperm injection is not related to any of the three basic sperm parameters. Human reproduction . 1995;10(5):1123–1129. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colaco S., Sakkas D. Paternal factors contributing to embryo quality. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics . 2018;35(11):1953–1968. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller D., Brinkworth M., Iles D. Paternal DNA packaging in spermatozoa: more than the sum of its parts? DNA, histones, protamines and epigenetics. Reproduction . 2010;139(2):287–301. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassuto N. G., Le Foll N., Chantot-Bastaraud S., et al. Sperm fluorescence in situ hybridization study in nine men carrying a Robertsonian or a reciprocal translocation: relationship between segregation modes and high-magnification sperm morphology examination. Fertility and Sterility . 2011;96(4):826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chelli M. H., Ferfouri F., Boitrelle F., et al. High-magnification sperm selection does not decrease the aneuploidy rate in patients who are heterozygous for reciprocal translocations. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics . 2013;30(4):525–530. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-9959-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mebrek M. L., Clède S., de Chalus A., et al. Simple FISH-based evaluation of spermatic nuclear architecture shows an abnormal chromosomal organization in balanced chromosomal rearrangement carriers. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics . 2020;37(4):803–809. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boitrelle F., Ferfouri F., Petit J. M., et al. Large human sperm vacuoles observed in motile spermatozoa under high magnification: nuclear thumbprints linked to failure of chromatin condensation. Human Reproduction . 2011;26(7):1650–1658. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassuto N. G., Hazout A., Hammoud I., et al. Correlation between DNA defect and sperm-head morphology. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2012;24(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franco J. G., Mauri A. L., Petersen C. G., et al. Large nuclear vacuoles are indicative of abnormal chromatin packaging in human spermatozoa. International Journal of Andrology . 2012;35(1):46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe S., Tanaka A., Fujii S., et al. An investigation of the potential effect of vacuoles in human sperm on DNA damage using a chromosome assay and the TUNEL assay. Human Reproduction . 2011;26(5):978–986. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilding M., Coppola G., di Matteo L., Palagiano A., Fusco E., Dale B. Intracytoplasmic injection of morphologically selected spermatozoa (IMSI) improves outcome after assisted reproduction by deselecting physiologically poor quality spermatozoa. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics . 2011;28(3):253–262. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammoud I., Boitrelle F., Ferfouri F., et al. Selection of normal spermatozoa with a vacuole-free head (x 6300) improves selection of spermatozoa with intact DNA in patients with high sperm DNA fragmentation rates. Andrologia . 2013;45(3):163–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2012.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utsuno H., Oka K., Yamamoto A., Shiozawa T. Evaluation of sperm head shape at high magnification revealed correlation of sperm DNA fragmentation with aberrant head ellipticity and angularity. Fertility and Sterility . 2013;99(6):1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garolla A., Fortini D., Menegazzo M., et al. High-power microscopy for selecting spermatozoa for ICSI by physiological status. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2008;17(5):610–616. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perdrix A., Travers A., Chelli M. H., et al. Assessment of acrosome and nuclear abnormalities in human spermatozoa with large vacuoles. Human reproduction . 2011;26(1):47–58. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boitrelle F., Albert M., Petit J.-M., et al. Small human sperm vacuoles observed under high magnification are pocket-like nuclear concavities linked to chromatin condensation failure. Reproductive Biomedicine Online . 2013;27(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boitrelle F., Guthauser B., Alter L., et al. The nature of human sperm head vacuoles: a systematic literature review. Basic and clinical andrology . 2013;23(1):p. 3. doi: 10.1186/2051-4190-23-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaoqin G., Zhenghui Z., Xueqian Z., Yuan H. Epigenetic modifications in human spermatozoon and its potential role in embryonic development. Yi chuan= Hereditas . 2014;36(5):439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schagdarsurengin U., Paradowska A., Steger K. Analysing the sperm epigenome: roles in early embryogenesis and assisted reproduction. Nature Reviews. Urology . 2012;9(11):609–619. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassuto N. G., Montjean D., Siffroi J.-P., et al. Different levels of DNA methylation detected in human sperms after morphological selection using high magnification microscopy. BioMed research international . 2016;2016:7. doi: 10.1155/2016/6372171.6372171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinborg A., Henningsen A.-K. A., Malchau S. S., Loft A. Congenital anomalies after assisted reproductive technology. Fertility and Sterility . 2013;99(2):327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akalin A., Kormaksson M., Li S., et al. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome biology . 2012;13(10):p. R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou G., Xia J. Using OmicsNet for network integration and 3D visualization. Current protocols in bioinformatics . 2019;65(1):p. e69. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellemans J., Mortier G., De Paepe A., Speleman F., Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome biology . 2007;8(2):p. R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods . 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Neve J., Thas O., Ottoy J.-P., Clement L. An extension of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for analyzing RT-qPCR data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology . 2013;12(3):333–346. doi: 10.1515/sagmb-2012-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.GTEx Consortium, Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group, et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature . 2017;550(7675):204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science . 2015;348(6235):648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue Z., Huang K., Cai C., et al. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature . 2013;500(7464):593–597. doi: 10.1038/nature12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bornstein C., Brosh R., Molchadsky A., et al. SPATA18, a spermatogenesis-associated gene, is a novel transcriptional target of p53 and p63. Molecular and Cellular Biology . 2011;31(8):1679–1689. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01072-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raimondo S., Gentile T., Gentile M., et al. p53 protein evaluation on spermatozoa DNA in fertile and infertile males. Journal of human reproductive sciences . 2019;12(2):114–121. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_170_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almon E., Goldfinger N., Kapon A., Schwartz D., Levine A. J., Rotter V. Testicular tissue-specific expression of the p53 suppressor gene. Developmental Biology . 1993;156(1):107–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang S., Wang X., Li W., et al. Biallelic mutations in _CFAP43_ and _CFAP44_ cause male infertility with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella. American Journal of Human Genetics . 2017;100(6):854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y., Sha Y., Wang X., et al. DNAH2 is a novel candidate gene associated with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella. Clinical Genetics . 2019;95(5):590–600. doi: 10.1111/cge.13525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coutton C., Escoffier J., Martinez G., Arnoult C., Ray P. F. Teratozoospermia: spotlight on the main genetic actors in the human. Human Reproduction Update . 2015;21(4):455–485. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown S. G., Publicover S. J., Barratt C. L. R., Martins da Silva S. J. Human sperm ion channel (dys)function: implications for fertilization. Human Reproduction Update . 2019;25(6):758–776. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guauque-Olarte S., Messika-Zeitoun D., Droit A., et al. Calcium signaling pathway genes RUNX2 and CACNA1C are associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Circulation. Cardiovascular Genetics . 2015;8(6):812–822. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wemhöner K., Friedrich C., Stallmeyer B., et al. Gain-of-function mutations in the calcium channel _CACNA1C_ (Cav1.2) cause non-syndromic long-QT but not Timothy syndrome. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology . 2015;80:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scholl U. I., Stölting G., Nelson-Williams C., et al. Recurrent gain of function mutation in calcium channel CACNA1H causes early-onset hypertension with primary aldosteronism. eLife . 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wishart M. J., Dixon J. E. The archetype STYX/dead-phosphatase complexes with a spermatid mRNA-binding protein and is essential for normal sperm production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . 2002;99(4):2112–2117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251686198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marumoto T., Zhang D., Saya H. Aurora-A -- a guardian of poles. Nature Reviews. Cancer . 2005;5(1):42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson M. L., Wang R., Sperry A. O. Novel localization of Aurora A kinase in mouse testis suggests multiple roles in spermatogenesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2018;503(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pugacheva E. N., Jablonski S. A., Hartman T. R., Henske E. P., Golemis E. A. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell . 2007;129(7):1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsuyama A., Shimazu T., Sumida Y., et al. In vivo destabilization of dynamic microtubules by HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. The EMBO Journal . 2002;21(24):6820–6831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plotnikova O. V., Nikonova A. S., Loskutov Y. V., Kozyulina P. Y., Pugacheva E. N., Golemis E. A. Calmodulin activation of Aurora-A kinase (AURKA) is required during ciliary disassembly and in mitosis. Molecular Biology of the Cell . 2012;23(14):2658–2670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-12-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ke Y.-N., Yang W.-X. Primary cilium: an elaborate structure that blocks cell division? Gene . 2014;547(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asteriti I. A., De Mattia F., Guarguaglini G. Cross-talk between AURKA and Plk 1 in mitotic entry and spindle assembly. Frontiers in oncology . 2015;5:p. 283. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao L.-J., Zhong Z.-S., Zhang L.-S., Chen D.-Y., Schatten H., Sun Q.-Y. Aurora-A is a critical regulator of microtubule assembly and nuclear activity in mouse oocytes, fertilized eggs, and early embryos. Biology of Reproduction . 2004;70(5):1392–1399. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 Sample collected and sperm parameters. Supplementary Table S2: list of differentially methylated genes (n = 138) between score 6 and score 0 sperm samples

Supplementary Figure S1: expression values (in Log2 (RPKM)) of CCDC88B, CACNA1H, and CACNA1C in 30 tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) consortium. Supplementary Figure S2: envisioned sperm test for male infertility in ART.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and available from the corresponding author upon request.