Abstract

Background:

Participation in elite-level soccer predisposes athletes to injuries of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), resulting in variable durations of time lost from sport.

Purpose:

To (1) determine the rate of return to play (RTP) and timing after MCL injuries, (2) investigate MCL reinjury incidence after RTP, and (3) evaluate the long-term effects of MCL injury on future performance.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Methods:

Using publicly available records, we identified athletes who had sustained MCL injury between 2000 and 2016 across the 5 major European soccer leagues (English Premier League, Bundesliga, La Liga, Ligue 1, and Serie A). Injured athletes were matched to controls using demographic characteristics and performance metrics from the season before injury. We recorded injury severity, RTP rate, reinjury incidence, player characteristics associated with RTP within 2 seasons of injury, player availability, field time, and performance metrics during the 4 seasons after injury.

Results:

A total of 59 athletes sustained 61 MCL injuries, with 86% (51/59) of injuries classified as moderate to severe and surgical intervention performed in 14% (8/59) of athletes. After injury, athletes missed a median of 33 days (range, 3-259 days) and 4 games (range, 1-30 games). Overall, 71% (42/59) of athletes returned successfully at the same level, with multivariable regression demonstrating no athlete characteristic predictive of RTP. MCL reinjury was reported in 3% (2/59) of athletes. Midfielders demonstrated decreased field time after RTP when compared with controls (P < .05). No significant differences in player performance for any position were identified out to 4 seasons after injury. Injured athletes had a significantly higher rate of long-term retention (P < .001).

Conclusion:

MCL injuries resulted in a median loss of 33 days in elite European soccer athletes, with the majority of injuries treated nonoperatively. RTP remained high, and few athletes experienced reinjury. While midfielders demonstrated a significant decrease in field time after RTP, player performance and long-term retention were not compromised. Future studies are warranted to better understand athlete-specific and external variables predictive of MCL injury and reinjury, while evaluating treatment and rehabilitation protocols to minimize time lost and to optimize athlete safety and health.

Keywords: return to play, medial collateral ligament (MCL), Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), soccer, player performance

Soccer is the most popular sport globally, and its popularity continues to rise with each successive year.22 Injuries are detrimental to the performance and health of soccer athletes and teams across all levels, becoming increasingly impactful as the level of competition increases. Owing to the requirements of the game, elite soccer athletes are particularly prone to knee injuries, including medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries.26 MCL injuries generally occur when a valgus stress is applied to the knee through direct contact, with tackling and being tackled being the most commonly reported injury mechanisms in soccer athletes.25 As such, the MCL is the most commonly injured knee ligament, with a reported injury rate of 0.33 per 1000 player-hours.4,26 Although the majority of MCL injuries are treated nonoperatively with physical therapy and bracing,3 MCL injuries represent the most common traumatic knee injury resulting in time lost in professional soccer.25

The incidence of MCL injuries in male soccer athletes has been reported to be twice that of female athletes,38 resulting in a mean of 23 to 24 days lost from play.25,26 However, the effect of MCL injuries on future athletic performance after recovery is largely unknown. As elite soccer athletes are at high risk for sustaining MCL injuries, it is important to better understand the effect of MCL injuries on time lost and the potential consequences on subsequent performance after return to play (RTP).24,33 The aims of the present study were to examine athletes from the 5 major European soccer leagues to (1) determine RTP rate and timing after MCL injuries, (2) investigate MCL reinjury incidence after RTP, and (3) evaluate the long-term effects of MCL injury on future performance.

Methods

Player Identification

A retrospective review of male soccer athletes participating in the 5 major European soccer leagues (English Premier League, Bundesliga, Serie A, La Liga, and Ligue 1) from 2000 to 2016 was conducted using a publicly available database, as established in previous investigations.6,7,10,21,27–33,35 Injury reports were collected from http://transfermarkt.co.uk, uefa.com, official team websites, injury reports, official team presses releases, personal websites, and professional sports statistical websites. Two authors (O.Z.L.-G. and E.M.F.) then cross-referenced sources for accuracy. Inclusion criteria consisted of any athlete sustaining an MCL injury who was drafted or signed to a roster during a season in which the team was ranked within 1 of the 5 major European soccer leagues, who played in at least 1 game before the index injury, and who had a minimum 1 season of follow-up after the season of injury. Athletes with no history of a reported injury to the lower extremity were identified for inclusion in the control cohort. Athletes with inconsistent or unclear injury reports were excluded from both the injured and control cohorts.

Data Collection

Data collected for each individual athlete included demographic data (age, height, position [attacker, midfielder, defender, goalkeeper], and playing experience based on years), time lost after injury (days and games missed), and subsequent performance as evaluated by field time metrics (total time played in the season, games played, and average minutes played per game) and performance metrics (goals scored, assists, and points per game) for up to 4 seasons after injury. Goals and assists were standardized to 90 minutes of play to account for differences in total field time between athletes.

Injury Severity

Owing to the absence of official medical record data, days missed served as a proxy for MCL injury severity; we used the same classification as in prior epidemiological studies published by the Union of European Football Association (UEFA).5,11,26 This classification differentiates between minor (1-7 days missed), moderate (8-28 days), and severe (>28 days) injuries.12,13 There were no athletes with reported reinjury within 12 weeks of the primary injury.

Case-Control Matching

A matched-cohort analysis was utilized to compare the performance metrics of athletes with a recorded MCL injury versus control athletes without a reported lower extremity injury. Athletes with MCL injury were matched to the control cohort in a 1:1 ratio using an optimized matching frontier methodology, a technique with concepts derived from k-nearest neighbor imputation.18–21 Athletes were matched by both demographic characteristics and baseline performance metrics. Demographic characteristics consisted of age, height, playing experience (within 1 year), and position, whereas performance metrics consisted of total field time, goals scored per 90 minutes of play, and assists per 90 minutes of play, which were recorded from 1 season before the year of injury for the MCL injury cohort.31–33 The acceptable ranges of matching for playing experience, goals, and assists were selected based on the calculated variability of these features before any data processing. Goalkeepers were included in the descriptive analysis but were excluded from the case-control analysis owing to the small number of injured athletes, preventing any meaningful analysis with long-term follow-up.24,25

Statistical Analysis

Player characteristics associated with RTP within 2 seasons of injury were investigated by use of a logistic multivariable regression. The log-rank test was utilized to compare player retention in the league between the control and injured cohorts during the follow-up period. Seasonal field time and performance metrics were collected from 3 seasons before the season of MCL injury through 4 seasons after injury. Overall differences between the control and injured cohorts were assessed for each metric and timepoint combination, with subsequent subgroup analysis based on player position. Univariate 2-group comparisons were performed using independent 2-group t tests and independent Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, where appropriate. Chi-square tests were utilized to compare categorical data. Factors in multivariable regression included demographic characteristics (age, player experience in the league, position of play) and performance metrics 1 season before injury (games played, time played, goals per 90 minutes of play, and assists per 90 minutes of play). Statistical significance was set at P < .05; all analyses were performed using R Studio software, Version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Post Hoc Analysis of Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Management of Meniscal Tear

After identification of the injured players who underwent a knee operation for treatment of MCL tear, the cohort of injured players was classified into surgical and nonsurgical cohorts. Identification of surgical management was pursued in the same manner as above by cross-referencing player injury reports with official league reports, official team websites, injury reports, official team press releases, personal websites, and professional statistical websites. Players with unknown management were categorized into the nonsurgical cohort. Comparative analysis of overall field time and performance metrics between cohorts was conducted in the same manner as that utilized for the a priori case-control analysis, followed by subgroup analysis by player position.

Results

Demographics

A total of 59 elite soccer athletes participating in 1 of the 5 major European soccer leagues were identified as having sustained an MCL injury between 2000 and 2016. Mean age at the time of injury was 27.05 ± 3.55 years, with injured athletes having played an average of 8.19 ± 4.31 years in the league at the time of injury. Case-control matching was satisfactory, with no significant differences in athlete demographics or baseline metrics 1 season before the season of injury (Table 1). Overall, 86% (51/59) of athletes had MCL injuries classified as moderate or severe, whereas 14% (8/59) of injuries required surgical intervention (Table 2).

Table 1.

Player Demographicsa

| Control (n = 56) | MCL Injury (n = 59) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control match | |||

| Number of players | .416 | ||

| Attacker | 12 | 12 | |

| Midfielder | 19 | 19 | |

| Defender | 25 | 25 | |

| Goalkeeper | 0 | 3 | |

| Calendar year of season of play | 2011 ± 4.87 | 2012 ± 2.99 | ≥.999 |

| Total years played in league | 6.96 ± 3.8 | 8.19 ± 4.31 | .999 |

| Height (m) | 1.82 ± 0.05 | 1.82 ± 0.07 | .923 |

| Age during season, y | 27.09 ± 3.57 | 27.05 ± 3.55 | .948 |

| Baseline metricsb | |||

| Games played | 26.54 ± 5.53 | 27.18 ± 3.59 | .712 |

| Total time played (minutes) | 1820.08 ± 695.14 | 1916.64 ± 508.07 | .667 |

| Goals scoredc | 0.22 ± 0.16 | 0.18 ± 0.16 | .554 |

| Assists recordedc | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | .487 |

aData are reported as No. of players or mean ± SD. MCL, medial collateral ligament.

bMetrics 1 season before the index timepoint.

cStandardized to 90 minutes of play.

Table 2.

Injury Characteristics (n = 59)a

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| MCL injury severity | |

| Mild-minor | 8 (14) |

| Moderate | 24 (41) |

| Severe | 27 (45) |

| Surgical intervention | 8 (14) |

| Primary injury | |

| Days missed | 33 [17-59] |

| Games missed | 4 [3-8] |

| RTP | |

| At any timepoint | 42 (71) |

| By 1 season after injury | 38 (64) |

| By 2 seasons after injury | 40 (68) |

| By 3 seasons after injury | 41 (69) |

| By 4 seasons after injury | 42 (71) |

| Secondary injury | |

| Number of MCL retears | 2 (3) |

| Time to MCL retear, years | 1 ± 0 |

| Days missed | 34 [17-56]b |

| Games missed | 3 [2-5]c |

aData are reported as No. of players (%) except for data with a non-Gaussian distribution, expressed as median [interquartile range]. MCL, medial collateral ligament; RTP, return to play.

bP = .270 compared with primary injury.

cP = .154 compared with primary injury.

Return to Play

Overall, 71% (n = 42/59) of players with MCL injury were reported to RTP successfully at the same level of competition. Of these, 64% (n = 38/42) returned within 1 season of injury. Injured athletes missed a median of 33 days (range, 3-259 days) and 4 games (range, 1-30 games). Of those returning to play, 3% (n = 2/59) of athletes experienced a repeat MCL injury, with no significant difference in days or games missed as compared with primary injury (Table 2). There were no player characteristics associated with rate of RTP on multivariable regression (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Regression of RTP at the Same Level Within 2 Seasons of Injurya

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| <21 | Reference | |

| 21-25 | 1.26 (0.63-2.51) | .52 |

| 26-30 | 1.60 (0.79-3.25) | .20 |

| >30 | 1.45 (0.66-3.17) | .36 |

| Time in league, y | ||

| <3 | Reference | |

| 3-5 | 1.24 (0.74-2.09) | .42 |

| 6-8 | 1.27 (0.76-2.10) | .37 |

| >8 | 0.96 (0.57-1.62) | .87 |

| Player position | ||

| Attacker | Reference | |

| Midfielder | 1.29 (0.77-2.17) | .33 |

| Defender | 1.05 (0.63-1.74) | .86 |

| Goalkeeper | 0.56 (0.29-1.09) | .09 |

| Games playedb | ||

| <10 | Reference | |

| 10-19 | 0.63 (0.22-1.87) | .41 |

| 20-29 | 1.33 (0.47-3.82) | .60 |

| >30 | 1.73 (0.49-6.02) | .40 |

| Time played, minb | ||

| <1000 | Reference | |

| 1000-1999 | 0.59 (0.20-1.70) | .33 |

| 2000-2500 | 0.72 (0.24-2.12) | .55 |

| >2500 | 0.58 (0.15-2.20) | .43 |

| Goalsb | ||

| <3 | Reference | |

| 3-6 | 0.90 (0.57-1.43) | .67 |

| 7-9 | 1.03 (0.36-2.92) | .96 |

| >9 | 0.99 (0.42-2.30) | .98 |

| Assistsb | ||

| 0-3 | Reference | |

| >3 | 1.59 (0.93-2.70) | .10 |

aOR, odds ratio.

bOverall metrics for 1 season before the index timepoint.

Player Availability After RTP

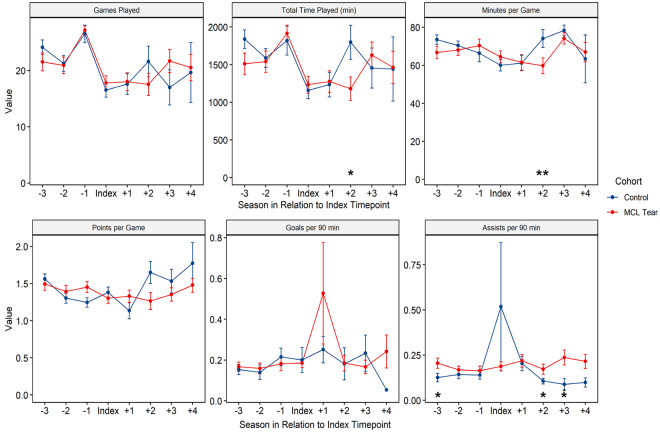

Long-term player availability during the 4-year follow-up period was significantly higher in athletes sustaining MCL injury as compared with controls (P < .001) (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in total years played in either the injured or control cohorts with case-control matching (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Player retention in the leagues by injury status during the study follow-up period. MCL, medial collateral ligament.

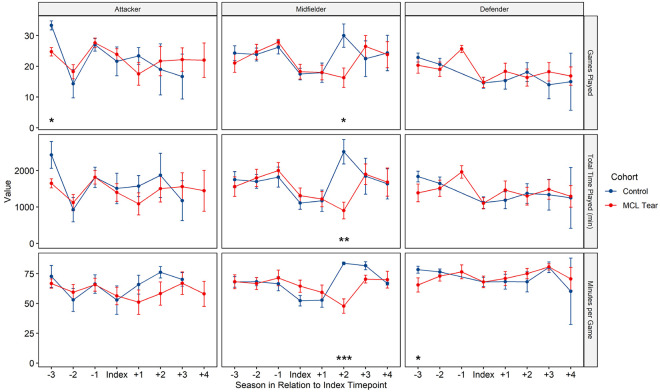

Player Performance

At 2 seasons after RTP, players who sustained MCL injury played 1688 fewer total minutes (P < .05) and 14 fewer minutes per game (P < .01) when compared with control athletes (Figure 2). Injured players demonstrated similar performance metrics, recording 0.06 more assists per game 2 seasons after RTP (P < .05), with similar points and goals per game when compared with control athletes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall player performance and field time. Significant difference between cases and controls: *P < .05, **P < .01. MCL, medial collateral ligament.

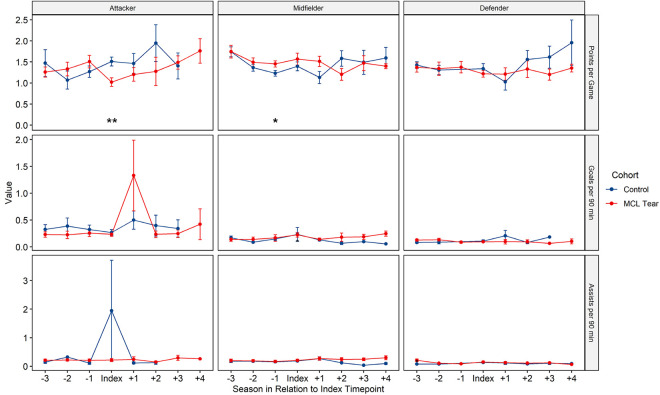

Field Time by Position

At 2 seasons after RTP, midfielders who sustained MCL injury played 14 fewer games per season (P < .05), 1616 fewer total minutes per season (P < .01), and 36 fewer minutes per game (P < .001) as compared with controls (Figure 3). No significant differences between injured and control athletes classified as attackers and defenders were identified based on games played, total time played, or minutes per game at any timepoint (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Field time by position. Significant difference between cases and controls: *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MCL, medial collateral ligament.

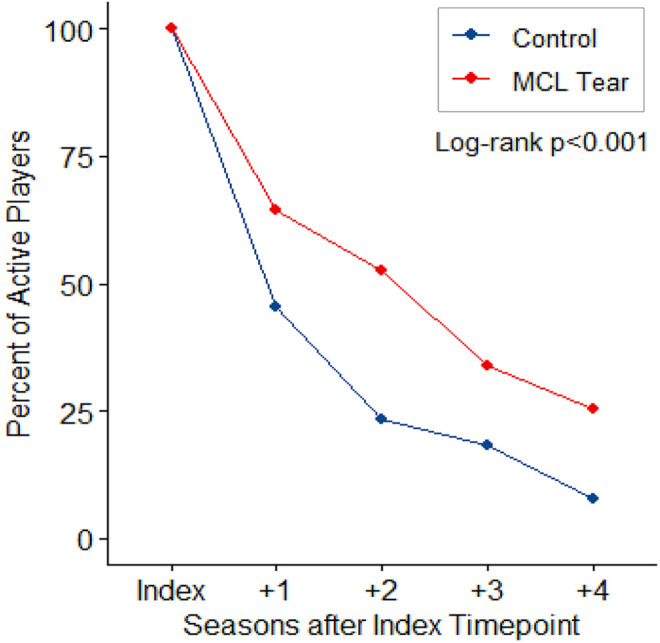

Player Performance by Position

No attackers, midfielders, or defenders demonstrated any significant difference in points, goals, or assists per game as compared with control athletes based on position at any timepoint (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Performance metrics by position. Significant difference between cases and controls: *P < .05, **P < .01. MCL, medial collateral ligament.

Post Hoc Analysis: Field Time and Performance by Injury Management

Athletes undergoing surgical treatment for MCL injuries did not demonstrate any significant differences in field time (games played, total time played, minutes per game) or performance metrics (points per game, goals per 90 minutes, assists per 90 minutes) when compared with athletes treated nonoperatively. Similarly, subgroup analysis between athletes treated surgically versus nonoperatively based on player position demonstrated no significant differences in field time or performance metrics.

Discussion

The principal finding from this investigation was that after MCL injury, 71% of European professional male soccer athletes were able to RTP successfully, missing a median of 33 days and 4 games. The incidence of MCL reinjury was low (3%), and midfielder was the only playing position associated with decreased field time when compared with control athletes 2 seasons after injury. Meanwhile, injured athletes demonstrated equivalent performance metrics after RTP when compared with control athletes. No significant differences in field time or performance metrics were identified in athletes with MCL injuries managed surgically versus nonoperatively.

In this series, 86% of MCL injuries were classified as moderate or severe, whereas only 14% of patients underwent surgery. This is consistent with the current management recommendation for MCL injuries, emphasizing a nonoperative approach for the majority of injuries, even in the case of grade 3 MCL injuries.16,17,24,38 Current recommendations for MCL rehabilitation propose a recovery period of 1 to 4 weeks for grade 1 or 2 MCL injuries, and 5 to 7 weeks for grade 3 MCL injuries.17 Successful nonsurgical treatment of MCL injuries has been attributed to the substantial healing potential of the MCL due to its high vascularity and growth factor–rich environment.24 Current management recommendations for most MCL injuries propose a trial of nonoperative therapy before consideration of any surgical intervention.38 Physical therapy, intraligamentous steroid injections, and bracing have all been reported methods of nonoperative treatment yielding excellent clinical results.9,14,16,17,24,25,38 However, the optimal protocol to assist elite athletes to RTP remains unclear, with some interventions shown to delay RTP without apparent clinical benefit.25 As such, further investigations evaluating the effect of various nonoperative treatment measures and protocols on RTP timing after MCL injury are warranted.

Surgical intervention for isolated MCL injuries remains rare in high-level and elite athletes, with surgery reserved only for severe injuries or those failing nonoperative management.1,2,25,3,6,13 Results from our investigation show that operative versus nonoperative MCL management did not result in significant differences in field time or performance metrics in injured athletes. Traditional indications for surgical management of MCL injuries include severe, full-thickness (grade 3) MCL tears, distal avulsion, and MCL injuries with multiligamentous or bony injury, as well as injuries failing nonoperative management.39 In a study of National Football League athletes, no significance difference in field time metrics was reported between athletes who underwent operative versus nonoperative management for isolated MCL injuries.23 When surgery is indicated, primary repair and autograft or allograft reconstruction with or without internal bracing augmentation are the surgical techniques utilized commonly.15,36,37 Moreover, a recent meta-analysis of 10 studies reported no significant difference in either range of motion or patient-reported outcomes when examining outcomes between isolated MCL reconstruction and MCL reconstruction with concomitant fixation or reconstruction for concurrent injuries within the knee.37

Athletes who sustained MCL injury missed a median of 33 days (range, 3-259 days) and 4 games (range, 1-30 games) during injury recovery. These results are notably longer than the prior epidemiologic UEFA injury study by Lundblad et al,26 who reported a median of 16 days missed in athletes because of MCL injury. This difference is likely attributable to the methodology of the current investigation, which is less likely to capture minor MCL injuries associated with relatively short absences. Other investigations have reported time lost after MCL injury to be as low as 16 days in young military academy athletes and 14 days in rugby athletes.1,34 Several studies have correlated MCL injury grade with time to RTP, reporting a median 13.5 days lost for grade 1 injuries compared with a median 29 days lost for grade 2 and 3 injuries.23,34 Although MCL injury severity could not be confirmed with associated radiographic imaging in the present study, the majority (86%) of athletes were reported to sustain moderate or severe injuries as defined by the UEFA model of injuries in professional soccer players.11

Attackers and defenders did not demonstrate significant differences in field time or performance after MCL injury, whereas midfielders played significantly fewer minutes per game, total games, and total minutes per season postinjury. Midfielders spend a substantial proportion of game-time traveling up and down the field, having to change direction on several occasions during the course of the game. A recent kinematic study reported that the demand on midfielders places athletes playing this position at higher risk for persistent MCL injury symptoms or reinjury.40 It is beyond the scope of the current investigation to determine whether coaches and athletes decreased field time in midfielders as a prevention measure or as a consequence of residual injury symptoms. Nonetheless, injured midfielders demonstrated equivalent performance metrics when compared with control athletes. Similar outcomes have been observed in American football players, with MCL-injured players demonstrating equivalent performance and a significantly higher long-term retention, regardless of surgical versus nonsurgical treatment.23

This study is not without limitations. Public data sources were utilized to identify athletes sustaining MCL injury, leading to the possibility of a selection bias toward inclusion of more severe injuries and possible omission of athletes with minor MCL sprain injuries. Despite possible skewing of data toward more severe injuries, the results of this study do not support a significant difference in performance between injured and control athletes. As a result of the small population of elite soccer players, only a relatively small cohort of injured athletes was identified, potentially limiting the results of this investigation. The reason players did not return to the same level of competition was rarely reported. Players may have returned to play in lower league levels or chose to retire for a reason unrelated to the injury, such as contract status. It was not possible to determine the specific degree of injury severity, along with individual differences in treatment and rehabilitation, because of the absence of access to official medical record documentation and radiographic imaging or reports. However, several prior studies have correlated MCL injury grade with length of time lost,17,23,34 with player absence having been established as a reliable proxy variable within the ongoing UEFA injury study.8

Conclusion

We found that injuries to the MCL remain relatively uncommon in elite European soccer athletes, and the majority of injuries are treated nonoperatively with a median loss of 33 days. RTP remains high, with few athletes experiencing reinjury, and although midfielders demonstrated a significant decrease in field time after RTP, player performance and long-term retention was not compromised. Future studies are warranted to better understand athlete-specific and external variables predictive of MCL injury and reinjury, while evaluating treatment and rehabilitation protocols to minimize time lost and to optimize athlete safety and health.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted April 14, 2021; accepted May 4, 2021.

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: B.F. has received research support from Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, and Stryker; consulting fees from Stryker; education payments from Medwest; and personal fees from Elsevier and Stryker; and has stock/stock options in Jace Medical stock. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval was not sought for the present study.

References

- 1.Awwad GEH, Coleman JH, Dunkley CJ, Dewar DC. An analysis of knee injuries in rugby league: the experience at the Newcastle Knights professional rugby league team. Sports Med Open. 2019;5(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakshi NK, Khan M, Lee S, et al. Return to play after multiligament knee injuries in National Football League athletes. Sports Health. 2018;10(6):495–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Kim PD, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee: current treatment concepts. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(2):108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(7):553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Waterman BR, Griffin JW, Romeo AA. Performance and return to sport in elite baseball players and recreational athletes following repair of the latissimus dorsi and teres major. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(11):1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erickson BJ, Harris JD, Heninger JR, et al. Performance and return-to-sport after ACL reconstruction in NFL quarterbacks. Orthopedics. 2014;37(8):e728–e734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller CW, Ekstrand J, Junge A, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(3):193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannotti BF, Rudy T, Graziano J. The non-surgical management of isolated medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14(2):74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grassi A, Rossi G, D’Hooghe P, et al. Eighty-two per cent of male professional football (soccer) players return to play at the previous level two seasons after Achilles tendon rupture treated with surgical repair. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(8):480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Bahr R, Ekstrand J. Methods for epidemiological study of injuries to professional football players: developing the UEFA model. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins RD, Fuller CW. A prospective epidemiological study of injuries in four English professional football clubs. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33(3):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins RD, Hulse MA, Wilkinson C, Hodson A, Gibson M. The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(1):43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided suture tape augmentation and stabilization of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7(3):e205–e210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopper GP, Jenkins JM, Mackay GM. Percutaneous medial collateral ligament repair and posteromedial corner repair with suture tape augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9(5):e587–e591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones L, Bismil Q, Alyas F, Connell D, Bell J. Persistent symptoms following non operative management in low grade MCL injury of the knee – the role of the deep MCL. Knee. 2009;16(1):64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim C, Chasse PM, Taylor DC. Return to play after medial collateral ligament injury. Clin Sports Med. 2016;35(4):679–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King G, Lucas C, Nielsen RA. The balance-sample size frontier in matching methods for causal inference. Am J Polit Sci. 2017;61(2):473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 19.King G, Nielsen R. Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Polit Anal. 2018;27(4):435–454. [Google Scholar]

- 20.King G, Zeng L. The dangers of extreme counterfactuals. Polit Anal. 2017;14(2):131–159. [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeBrun DG, Tran T, Wypij D, Kocher MS. How often do orthopaedic matched case-control studies use matched methods? A review of methodological quality. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(3):655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Licciardi A, Grassadonia G, Monte A, Ardigo LP. Match metabolic power over different playing phases in a young professional soccer team. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020;60(8):1170–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan CA, Murphy CP, Sanchez A, et al. Medial collateral ligament injuries identified at the National Football League scouting combine: assessment of epidemiological characteristics, imaging findings, and initial career performance. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(7):2325967118787182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan CA, O’Brien LT, LaPrade RF. Post operative rehabilitation of grade III medial collateral ligament injuries: evidence based rehabilitation and return to play. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(7):1177–1190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundblad M, Hägglund M, Thomeé C, et al. Medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee in male professional football players: a prospective three-season study of 130 cases from the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(11):3692–3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundblad M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, Karlsson J, Ekstrand J. The UEFA injury study: 11-year data concerning 346 MCL injuries and time to return to play. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(12):759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mai HT, Chun DS, Schneider AD, et al. Performance-based outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in professional athletes differ between sports. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(10):2226–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansournia MA, Jewell NP, Greenland S. Case-control matching: effects, misconceptions, and recommendations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(1):5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall NE, Keller RA, Lynch JR, Bey MJ, Moutzouros V. Pitching performance and longevity after revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niederer D, Engeroff T, Wilke J, Vogt L, Banzer W. Return to play, performance, and career duration after anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a case-control study in the five biggest football nations in Europe. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(10):2226–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okoroha KR, Fidai MS, Tramer JS, et al. Length of time between anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport does not predict need for revision surgery in National Football League players. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(1):158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okoroha KR, Kadri O, Keller RA, et al. Return to play after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in National Football League players. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(4):2325967117698788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okoroha KR, Taylor KA, Marshall NE, et al. Return to play after shoulder instability in National Football League athletes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roach CJ, Haley CA, Cameron KL, et al. The epidemiology of medial collateral ligament sprains in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiffner E, Latz D, Grassmann JP, et al. Fractures in German elite male soccer players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019;59(1):110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stannard JP. Medial and posteromedial instability of the knee: evaluation, treatment, and results. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2010;18(4):263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varelas AN, Erickson BJ, Cvetanovich GL, Bach BR, Jr. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction in patients with medial knee instability: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(5):2325967117703920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wijdicks CA, Griffith CJ, Johansen S, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Injuries to the medial collateral ligament and associated medial structures of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1266–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson TC, Satterfield WH, Johnson DL. Medial collateral ligament “tibial” injuries: indication for acute repair. Orthopedics. 2004;27(4):389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zago M, Esposito F, Bertozzi F, et al. Kinematic effects of repeated turns while running. Eur J Sport Sci. 2019;19(8):1072–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]