Abstract

The efficiency of the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) can be facilitated by the presence of proton-transfer groups in the vicinity of the catalyst. A systematic investigation of the nature of the proton-transfer groups present and their interplay with bulk proton sources is warranted. The HERs electrocatalyzed by a series of iron porphyrins that vary in the nature and number of pendant amine groups are investigated using proton sources whose pKa values vary from ~9 to 15 in acetonitrile. Electrochemical data indicate that a simple iron porphyrin (FeTPP) can catalyze the HER at this FeI state where the rate-determining step is the intermolecular protonation of a FeIII-H− species produced upon protonation of the iron(I) porphyrin and does not need to be reduced to its formal Fe0 state. A linear free-energy correlation of the observed rate with pKa of the acid source used suggests that the rate of the HER becomes almost independent of pKa of the external acid used in the presence of the protonated distal residues. Protonation to the FeIII-H− species during the HER changes from intermolecular in FeTPP to intramolecular in FeTPP derivatives with pendant basic groups. However, the inclusion of too many pendant groups leads to a decrease in HER activity because the higher proton binding affinity of these residues slows proton transfer for the HER. These results enrich the existing understanding of how second-sphere proton-transfer residues alter both the kinetics and thermodynamics of transition-metal-catalyzed HER.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Reactions that require both protons and electrons are abundant in nature and are involved in both generation and storage of energy. Of these, reactions like O2 reduction/generation,1–6 H2 generation/oxidation7–10 and COx/SOx/NOx reduction11–18 are of keen contemporary interest because of the ongoing pursuit for clean energy and environment. Efficient catalysts are required for the conversion of electricity from renewable energy sources like solar and wind to chemical energy for storage in the form of chemical fuels. Natural enzymes have evolved to include sophisticated active sites where, apart from the inner coordination sphere of the metal, the noncovalent secondary interactions like hydrophobicity, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics play a major role in defining the reactivity of these active sites.19,20 The protein scaffold surrounding the enzyme active sites often controls the bond formation and cleavage by means of electron-transfer, proton-transfer, and atom-transfer reactions, imparting them the desired rate and selectivity.19,21–23 Emulating these finer attributes of metalloenzyme catalysis in bioinspired small molecules has been a major area of focus in recent records.24–27 The role of proton relays is being actively investigated in reactions that require multiple protons and electrons, e.g., H+ reduction,28,29 O2 reduction,30,31 CO2 reduction,32,33 H2 oxidation,34–36 and H2O oxidation.37–39 These results all stress the importance of the precise positioning of proton-transfer groups in promoting proton transfer, proton-coupled electron transfer, and hydrogen-bond formation, which are involved in the key steps in catalysis.

The reduction of protons to produce molecular hydrogen by means of storing energy is catalyzed most efficiently by the natural enzyme hydrogenase.34,40 To attain efficient HER and hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR), several groups have attempted to incorporate proton shuttles in mononuclear complexes using first-row transition metals (e.g., iron, nickel, and cobalt).41–45 Such efforts are inspired by the bridging azadithiolate ligand present in the binuclear active site of [Fe–Fe]hydrogenase.34,46,47 Few research groups have investigated the kinetic and thermodynamic advantage of utilizing outer-coordination-sphere proton relays in artificial complexes during catalysis.42,48,49 Conceivably, a proton-transfer residue can shuttle protons, lowering the barrier, and/or act as a local source of proton, lowering the entropic cost involved in protonating the catalytic metal center. Thus, these phenomena entail interplay between the pKa values of the metal center, of these second-sphere residues, and of the bulk acid source (pH in water). DuBois and coworkers had demonstrated that the incorporation of a nitrogenous base in a diphosphine ligand backbone, forming the complex [Ni(PNP)2]2+, readily binds hydrogen and shows faster electrochemical hydrogen oxidation at lower overpotential than the analogous [Ni(depp)2]2+ complex with no tethered base.43 Later, these ligands were modified by increasing the chain length and number of bases in [Ni(PR2NR’2)2]2+ to allow better access of the nitrogenous proton shuttle to the nickel center, resulting in very high turnover rates for electrocatalytic HER in the nickel catalyst [Ni(PPh2NPh)2](BF4)2 (PPh2NPh = 1,3,6-triphenyl-1-aza-3,6-diphosphacycloheptane).50–52 Shaw and coworkers established that the arginine amino acid in a water-soluble [Ni(PCy2NArg2)2]8+ complex enhances the electrocatalytic activity when these residues were protonated.36 In the above case, the guanidium groups on the outer sphere of the molecule were proposed to shuttle protons via the Grotthuss mechanism.36 Graham and Nocera introduced a hanging carboxylic acid/pendant base in the second coordination sphere of iron porphyrins, hangman porphyrins, to channel protons to the active site to exhibit enhanced catalytic HER activity compared to nonhangman analogues.53 The thermodynamic advantage of reducing the overpotential for HER was also evidenced by having a hanging carboxylic acid in a cobalt hangman porphyrin.48 Similarly, while iron porphyrins were reported to catalyze HER in their formal Fe0 state,8 the presence of four hydrogen-bond donor triazole moieties (pKa in acetonitrile is ~8)54 along with four ferrocene groups in a mononuclear iron porphyrin FeFc4 allowed the protonation of iron(I) porphyrins, reducing the overpotential of HER by 50% in the presence of strong acids in both aqueous and organic solvents.55 Very recently, Artero and co-workers reported HER catalyzed by a [Co(bapbpy)Cl]+ complex containing a redox-active bipyridine ligand with associated pendant proton relays.56 The electrocatalytic behavior in response to systematic variation in pKa of the acid source suggests that the CoI state becomes activated for HER depending upon pKa of the acid sources used. Conversely, systematic variations in pKa and the number of the pendant bases along with variation of pKa of the acid source are necessary to complement these investigations and advance the current understanding of the roles played by these proton shuttles.

In this paper, electrocatalytic HER catalyzed by a series of mononuclear iron meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (FeTPP) derivatives (Figure 1) using acid sources over a range of pKa = 8.64–14.98 in acetonitrile is investigated. It has been suggested computationally that intramolecular proton transfer results in a reduced energy barrier.57 Using unsubstituted FeTPP as a control, electrocatalysis by the iron porphyrins with pendant bases is investigated. The iron porphyrins are appended with arms bearing basic residues, which vary in both their pKa values and numbers. The results obtained suggest that pendant basic residues, which get protonated in the presence of bulk acid sources, can act as local proton sources and lower the barrier of protonation of the FeI state of the catalyst. The effect of variation in the pKa value and number of pendant bases is discussed in detail using a series of iron porphyrins, where both pKa value of the pendant base and number of bases are systematically varied.

Figure 1.

Representative molecular structures of the iron porphyrins [FeTPP (A), FeL3 (B), FeL2 (C), and 6LFe (D)] studied here.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution by FeTPP.

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) of FeTPP is well documented in the literature58–60 and exhibits three responses, corresponding to the FeIII/II, FeII/I, and FeI/0 redox couples at −0.68, −1.5, and −2.07 V (Figure S1), respectively (with respect to Fc+/Fc0), with peak-to-peak separations (ΔEp) of 61, 67, and 71 mV, respectively, at a 100 mV/s scan rate (ν) in acetonitrile. In the presence of acids with a wide range of pKa values [e.g., tosic acid (TsOH; pKa = 8.64), p-bromoanilinium tosylate (BA-H+; pKa = 9.43), diisopropylanilinium tosylate (DIPA-H+; pKa = 10.62), N,N-diethylanilinium tosylate (DEA-H+; pKa = 11.42), and collidinium tosylate (Col-H+; pKa = 14.98)] into the acetonitrile solution of 1 mM FeTPP, an electrocatalytic HER is observed (the tosylate salts of the conjugate acids are generated in situ by adding TsOH to the corresponding amine).61–63 The FeIII/II potential is not affected in the presence of these bases because they are all noncoordinating due to the presence of bulky groups around the potentially coordinating nitrogen atom (Figure S1). This is in contrast to recent investigations using iron porphyrins, where coordinating axial ligands were demonstrated to substantially affect the kinetics of the HER.64

The data suggest that the electrochemical response along with the HER current is dependent on the pKa value of the external acid source used. For the addition of a strong acid like TsOH (pKa = 8.64) in 1 mM FeTPP [0.1 M tetrabutylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) in acetonitrile], the FeII/I redox wave becomes irreversible and HER is observed with a peak potential of −1.50 V. This HER current corresponds to the process where a FeI species is protonated to form FeIII-H−, which is then reduced to FeII-H− and becomes further protonated to evolve H2 similar to previously reported steps in related systems.48,65–67 There are irreversible processes between the FeIII/II and FeII/I redox couples (Figure 2A), which are due to protonation of the meso-carbon in the porphyrin ligand (also known as phlorin) by a strong acid.8,68,69 However, closer inspection of the data reveal that the HER current overlays the reduction of FeII to FeI at −1.50 V, which indicates H2 formation via protonation of the FeIII-H− species.

Figure 2.

CV diagrams of 1 mM FeTPP in an acetonitrile solution with a glassy carbon working electrode using 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte for the HER using four different acid sources: (A) TsOH; (B) BA-H+; (C) DIPA-H+; (D) DEA-H+; (E) Col-H+. The scan rate is 100 mV/s. A platinum wire is used as a counter electrode. All potentials are reported with respect to the Fc+/Fc0 couple using ferrocene as an internal standard.

When the acid source is changed from TsOH to weaker acids like BA-H+ (pKa = 9.43), DIPA-H+ (pKa = 10.62), DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42), and Col-H+ (pKa = 14.98), the catalytic process originating from the FeI oxidation state at −1.30 V is retained, but the irreversible electrochemical response, due to protonation of the porphyrin ring, is not observed. Furthermore, the catalytic current arising from protonation of the FeI species at the FeII/I potential gets saturated; i.e., the HER current becomes independent of the substrate [BH]+ concentration. For example, with BA-H+ and DIPA-H+, the catalytic HER current from the FeI state becomes saturated at 5 equiv of acid. The further addition of acid into the same solution results in another redox process at more negative potential corresponding to HER by the protonation of FeII-H− species (Figure 2B,C) produced by the reduction of its FeIII-H− precursor. When the acid source is changed to DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42), which has higher pKa value than DIPA-H+, the catalytic activity of the FeI state is substantially reduced, as indicated by the diminished catalytic current at the FeII/I potential, and the catalytic current corresponding to HER obtained by the FeII-H− species dominates (Figure 2D).

Using the Col-H+ as the acid source (pKa = 14.98), the CV diagram of the FeII/I redox process remains unaltered and the HER proceeds mostly through the FeII-H− species at −1.82 V under the same condition. CV at very slow scan rates shows a loss of reversibility of the FeII/I CV response (Figure 4) and minimal current enhancement. Instead, the HER proceeds via FeII-H−, implying protonation of the FeI state but not the resulting FeIII-H− species. Thus, the electrochemical data presented here clearly demonstrate that there are two possible routes to the formation of H2 catalyzed by simple iron porphyrins like FeTPP. For acid sources having pKa ≤ 11.42 (BA-H+, DIPA-H+, DEA-H+, and TsOH), the FeI state is protonated to form a FeIII-H− species, which then accepts another proton to generate H2 without further reduction. As was already established, another possible route to HER after saturation of the catalytic current or in the absence of catalysis from the FeII/I redox state is reduction of the FeIII-H− species, generating a FeII-H− species, which is further protonated to eliminate H2. The latter process was investigated in detail earlier8,64,66,67,70 and is not the focus of this investigation, which is directed to the HER from the FeI state.

Figure 4.

Scan rate dependence plot of 1 mM FeTPP in an acetonitrile solution containing 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte with a glassy carbon working electrode and platinum wire as a counter electrode. All potentials were reported versus Fc+/Fc using ferrocene as an internal standard using 5 equiv of collidinium (Col-H+) as the acid source.

The changes in the electrochemical response in FeTPP with a change of pKa of the acid source reflect the pKa values of different protonation events in FeTPP. Considering the discussion further and as depicted in the mechanistic scheme of Figure 3, there are four different protonation events under HER conditions that manifest themselves through distinct electrochemical responses. The CV responses allow an estimation of the approximate pKa values for these processes. The processes and their effect on the CV response are as follows (note that pKa of the metal center refers to pKa of the species before protonation or pKa of the acid source required to protonate because protonation of the same are irreversible):

Protonation of the porphyrin ring (pKa1) results in irreversible processes between the formal FeIII/II and FeII/I redox couples.

Protonation of FeI (pKa2) to form FeIII-H− results in an irreversible nature of the FeII/I redox couple.

Protonation of FeIII-H− (pKa3) results in a HER current at the FeII/I redox potential (−1.48 V).

Protonation of the FeII-H− species (pKa4) results in a HER current at a more cathodic potential, that beyond the FeII/I redox process (−1.86 V).

Figure 3.

Left: CV overlay of 1 mM FeTPP in an acetonitrile solution with a glassy carbon working electrode using 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte at a scan rate of 100 mV/s for HER using four different acid sources: (A) TsOH (pKa = 8.7; associated with protonation steps 1–3); (B) BA-H+ (pKa = 9.43; associated with protonation steps 2–4); (C) DIPA-H+ (pKa = 10.62; associated with protonation steps 2–4; (D) DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42; associated with protonation steps 2–4); (E) Col-H+ (pKa = 14.98; associated with protonation steps 2 and 4). Platinum wire was used as a counter electrode, and all potentials were reported versus Fc+/Fc using ferrocene as an internal standard. Right: Proposed mechanism of HER for FeTPP with probable pathways in the presence of variable acid sources with different pKa values.

Protonation of the porphyrin ring can occur in the presence of a strong acid like TsOH (pKa = 8.64) and does not occur in BA-H+ (pKa = 9.43), indicating that pKa of the porphyrin ring lies below 9.43 (pKa1) and above 8.64. Protonation of the FeII-H− species (pKa4), resulting in the catalytic HER current, can be achieved even with Col-H+, specifying that the FeIII-H− species is formed and reduced to generate FeII-H− species; the pKa value of the FeII-H− species (>14.98) is greater than those of all of the acid sources investigated here. The FeII/I redox process is visible in the presence of Col-H+ and becomes irreversible only at very slow scan rates (Figure 4), suggesting that the protonation of FeI is slow (does not occur at scan rates higher than 100 mV/s) and pKa2 is greater than 14.98. Despite protonation of FeI at slow scan rates, HER is not observed at the FeII/I potential via the protonation of FeIII-H− produced but rather HER is observed upon its reduction to FeII-H−. Thus, the pKa3 value of FeIII-H− must be lower than 14.98, and/or the rate-determining step of HER by an iron(I) porphyrin must be the second protonation step, i.e., protonation of the FeIII-H− species. Alternatively, FeTPP shows a small catalytic current from the FeI state in the presence of DEA-H+, suggesting that the pKa3 value of FeIII-H− is >11.42. Note that the fact that pKa of the monoanionic FeI species is higher than that of the neutral FeIII-H− species, i.e., pKa2 > pKa3, is logical. Having established the basic pKa values of the species involved in HER catalyzed by a simple FeTPP, the effect of pendant amine groups has been investigated and is now discussed.

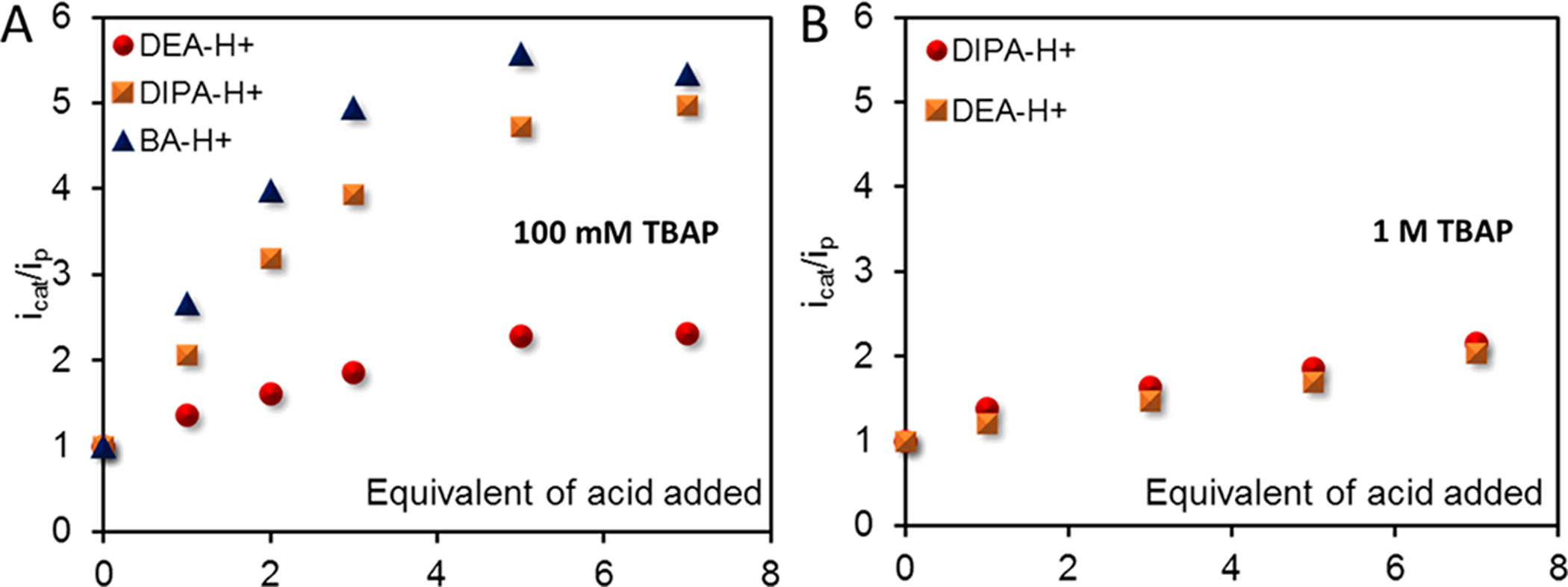

The protonation of FeI to form FeIII-H− occurs in the presence of all acids (pKa = 9.43–14.98) used here, and subsequent protonation of FeIII-H− (11.42 < pKa3 < 14.98) to produce H2 results in the catalytic HER current at the FeII/I potential. A feature of the catalytic behavior that had eluded past investigations that used strong acids is saturation of the HER current originating from the FeI species. Such a behavior is suggestive of a fast precatalytic equilibrium binding step between the FeIII-H− species and substrate, proton source, involved. This is supported by a plot of icat/ip versus equivalents of acid used, which shows that saturation is achieved at a much lower concentration for acids having a lower pKa (Figure 5A), i.e., better hydrogen-bond donors. This situation is characteristic of Michaelis–Menten-type enzyme kinetics, where a pre-equilibrium enzyme substrate binding step precedes the rate-determining step and saturation of the rate is observed at higher substrate concentration. Because the TPP ligand framework does not offer a distinct binding site for these anilinium ions from the acid source, it is likely that the FeIII-H− species associates with the anilinium ion of the corresponding conjugate acid in solution via intermolecular dihydrogen bonding interaction before catalysis occurs. Such interactions are weakened in the presence of electrolytes. Accordingly, saturation behavior of the HER current is lost when the concentration of the electrolyte is increased to 1 M (Figures 5B and S2).

Figure 5.

icat/ip plot for the catalytic wave at the FeII/I redox potential with the addition of equivalents of four different acids for FeTPP in the presence of (A) 100 mM TBAP and (B) 1 M TBAP.

Effect of a Distal Base on the Electrochemical HER.

The porphyrins are grouped in two classes: (a) varying the pKa value of the distal base; (b) varying the number of basic residues having the same pKa.

a. Effect of the pKa Value of the Distal Base.

The approximate pKa value of the acidic forms of pyridine in FeL2 is 13.11, and that of the primary amine in FeL3 is 16.9 in acetonitrile.62,63 In acetonitrile, the HER by FeL2 and FeL3 is probed in the presence of 5 equiv of [BH+]-OTs, where the pKa value of the conjugate acid is varied from 9.43 to 14.98. Protonation of the ring (i.e., step 1 in Figure 3, right), which has pKa < 9.43, is not observed in any of these cases for the acid sources having pKa ≥ 9.43. The FeIII/II CV for FeL2 moves anodically by 60 mV once the pKa value of the acid is lowered below the pKa value of the pendant pyridine (13.11), suggesting protonation of the pendant pyridine by the acid source in the solvent accompanying the reduction. Similarly, the FeIII/II CV for FeL3 is shifted anodically by 60 mV even when Col-H+ is used as the acid source because the pKa value of the pendant amine in FeL3 (16.9) is higher than that of Col-H+ (14.98). The protonation of FeII-H− (pKa > 14.98) resulting in a HER current at potentials below that of the FeII/I redox process is observed for all of these acids. The protonation of FeI (pKa > 14.98), as is evident by a slight anodic shift and the irreversible nature of the FeII/I redox wave, is observed for all of the acids used here (Figure 6). In these cases, the HER current gradually increases in intensity and shifts anodically as the pKa value of the acid source is lowered (Figure 6). The electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution by FeIII-H− protonation remarkably slows in FeTPP when using a weaker acid source like DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42), but significant catalytic current enhancement occurs in these two catalysts bearing pendant bases. The HER from Col-H+ results in a small catalytic current in FeL2 with a pendant pyridine but is clearly observed with the pendant alkyl amine in FeL3. Unlike FeTPP, the HER by FeI is observed with Col-H+ (pKa = 14.98) even under high scan rates in FeL2 and FeL3 (Figure S3), suggesting that pKa of FeIII-H− produced in these systems is higher than or similar to (due to hydrogen bonding with the pendant group) those of the pendant bases (pyridine in FeL2 and amine for FeL3) in these porphyrins. Similarly, pKa enhancement by hydrogen bonding was observed in the same system for an axial −OOH ligand.31 Thus, the protonation of FeIII-H−, which is completely inhibited in FeTPP, is enabled in the presence of pendant bases from Col-H+, allowing HER in FeL2 and FeL3. Note that a blank glassy carbon electrode does not show HER at these potentials with these acid sources in the absence of a catalyst under similar experimental conditions (Figure S7), but rather a HER current is observed at more negative potentials, as previously reported.71

Figure 6.

CV overlay of 1 mM FeL2, FeL3, and 6LFe in an acetonitrile solution for HER with a glassy carbon working electrode and a platinum wire counter electrode using 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte at a scan rate of 100 mV/s with respect to a Fc+/Fc0 couple using four different acid sources: (A) TsOH (pKa = 8.64) associated with protonation steps 1–4 for all; (B) BA-H+ (pKa = 9.43) associated with protonation steps 2–4 for all; (C) DIPA-H+ (pKa = 10.62) associated with protonation steps 2–4 for all; (D) DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42) associated with protonation steps 2–4 (Figure 3, right) for FeL2 and FeL3 and processes 2 and 4 for 6LFe; (E) Col-H+ (pKa = 14.98) associated with mainly processes 2 and 4 for all of the complexes except for FeL3, where the protonation step 3 is involved.

Both FeL2 (Figure 7A–D) and FeL3 (Figure 8A–D) show a clear saturation of the HER current catalyzed by the FeI state using the different acid sources. Controlled potential electrolysis experiments at −1.2 V (vs Ag/AgCl reference electrode) confirm the release of H2 gas during a headspace gas analysis in gas chromatography (GC; Figure S4). Although the HER current saturates in FeL2 and FeL3 with increasing concentration of [BH+] like FeTPP, the saturation and activity is not lost for FeL2 in the presence of 1 M electrolyte (Figure S5). Thus, saturation of the HER current from the FeI state in these neutral iron(I) porphyrins having protonated bases does not involve a precatalytic bonding/association equilibrium of FeIII-H− with the external proton source [BH]+ but rather reflects an intramolecular proton transfer from the protonated pendant base to FeIII-H−. Protonation of the pendant base in the presence of these conjugate acids is evident from the shift in the FeIII/II CV depending on the pKa value of the acid source and equivalents of the external acid source needed to protonate the pendant base and to reach saturation of the catalytic current at the FeII/I potential; unsurprisingly, increase with its pKa (Figure S6). For example, 3 equiv of BA-H+ (pKa = 9.43) is enough to protonate the pendant pyridine in FeL2 (pKa = 13.11), while 5 equiv of DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42) is required to achieve the same (Figure S6).

Figure 7.

CV diagrams of 1 mM FeL2 in an acetonitrile solution with a glassy carbon working electrode using 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte for HER using four different acid sources: (A) BA-H+; (B) DIPA-H+; (C) DEA-H+; (D) Col-H+. The scan rate is 100 mV/s. Platinum wire is used as the counter electrode. All potentials are reported with respect to a Fc+/Fc0 couple using ferrocene as an internal standard.

Figure 8.

. CV diagrams of 1 mM FeL3 in an acetonitrile solution with a glassy carbon working electrode using 0.1 M TBAP as the electrolyte for HER using four different acid sources: (A) BA-H+; (B) DIPA-H+; (C) DEA-H+; (D) Col-H+. The scan rate is 100 mV/s. Platinum wire is used as the counter electrode. All potentials are reported with respect to a Fc+/Fc0 couple using ferrocene as an internal standard.

The results presented above clearly demonstrate the advantage of having a pendant base in iron porphyrins during HER, where these bases allow the protonation and/or proton translocation to its FeIII-H− center, resulting in higher HER currents at the FeII/I potential than FeTPP for the same acid source. Given that the pendant base is protonated by external acid sources having pKa values of less than that of the pendant base and considering the fact that the rate-determining step is H+ transfer to the FeIII-H− species, these results may imply that the pendant bases facilitate the electrcatalytic HER via enhancement of the protonation rate of the FeIII-H− species produced, and the fact that this HER current becomes independent of the external conjugate acid concentration, further indicates that this protonation step is likely intramolecular. Further insight into this is obtained from the catalytic rates presented in a later section.

b. Effect of the Number of Bases on the HER.

The number of pendant bases was varied from one pyridine to three pyridines for complexes FeL2 and 6LFe, respectively (Figure 1). The CV data for the FeL2, FeL3, and 6LFe complexes with 1 mM catalyst concentration were recorded in an acetonitrile solution using the same set of acids (pKa = 8.64 − 14.98). The CV of these catalysts without any acid showed the FeIII/II, FeII/I, and FeI/0 redox processes (peak separation of 75 ± 10 mV) having potentials similar to FeTPP, indicating that the incorporation of these bases in the porphyrin ligand does not alter the electronic structure of the iron center. Note that the CV response of the 6LFe complex is inherently complicated because of the counteranion dissociation and coordination of one of the free pyridines to the FeIII and FeII states, likely that previously established.72,73 The large potential shifts and multiple catalytic waves of FeIII/II and FeII/I redox couples in the presence of BA-H+ and DIPA-H+ can be attributed to the protonation of pyridine (Figure S8). Because there are three pyridines, there is the possibility of multiple protonations in 6LFe. This is the case for BA-H+ and DIPA-H+ (Figure 6, green and red lines) where the shifts in the FeIII/II and FeII/I processes are more than that observed for DEA-H+ and Col-H+ (Figures 6, blue and yellow lines, and S8). Furthermore, for DEA-H+ and Col-H+, the shifts become saturated upon using 1 equiv of acid, suggesting that in these two cases only one proton binds and the binding of this proton is more favorable than in FeL2, which has a single pendant pyridine but requires more than 1 equiv of acid that has pKa > 10, suggesting that the three pyridines in 6LFe form a “proton sponge” with a very high first pKa. For these acid sources, the catalytic current of HER increases because of protonation of the FeIII-H− species; i.e., the FeI state can catalyze HER similar to that in FeL2 and FeL3. The magnitude of the HER current from the FeIII-H− species is smaller in 6LFe relative to FeL2. In fact, while FeL2 shows a catalytic current at FeII/I redox potential from DEA-H+ (pKa = 11.42), 6LFe having three pyridines does not show such a current enhancement from the FeI state and the CV diagram of the FeII/I redox wave becomes irreversible owing to the protonation and formation of a FeIII-H− species (Figure S8). Thus, 6LFe, which features a greater number of pendant bases relative to FeL2, shows a weaker catalytic current for HER. This is because the three pyridines together can act as proton sponge, causing the intramolecular protonation of FeIII-H− to be slow (see DFT Calculations).

Rate Determination Using the Foot-of-the-Wave Analysis (FOWA).

The catalytic rates of HER from the FeI state can be determined either by using the FOWA of the kinetic region developed by Costentin and Savéant at which the HER current depends on the substrate concentration (acid)74 or by analyzing icat/ip at acid concentrations where the scan-rate-independent HER current plateaus.75–77 In our cases, the electrochemical processes deviate from the ideal S-shaped behavior, and the catalytic rates are analyzed under purely kinetic conditions at the foot of the wave in the absence of any side phenomena. Here, we have evaluated the reaction rates for the heterolytic reaction pathway (ECCE mechanism) from the slope of the linear fit of i/ip versus [1 + exp(F/RT)(E − Ecat/2)]−1 (Figures S9–S13) using eq 1 by which the FOWA expression can be generally represented.78,79

| (1) |

where n = number of electrons transferred from the electrode, T is the temperature, R is the gas constant, ip = CV peak current of one electron-transfer process, i = catalytic peak current, k is the second-order rate constant of the rate-determining step, F is the Faraday constant, CA0 is the acid concentration, kCA0 = kobs is the first-order rate, ν is the scan rate, and E − Ecat/2 is the difference between the applied potential (E) and the potential of the half-peak catalytic current (Ecat/2) in the presence of a substrate.

The first-order rates (kCA0) of HER for all of these complexes are determined at 5 equiv of acid concentration with respect to the catalyst concentration (Table 1), where the pendant bases are protonated (see above). The rate of HER for FeTPP drops from 4.9 ± 0.5 to 1.2 ± 0.3 s−1 when the pKa value of the acid source is increased from 9.43 in BA-H+ to 11.42 in DEA-H+. This is due to stronger N–H bonds in acids having higher pKa, which would result in higher activation energies for the rate-determining protonation step by the acid [BH+]-OTs−, leading to H2 release. The rates of HER are, in general, estimated to be higher for iron porphyrins with pendant bases like FeL2 and FeL3 relative to FeTPP for any acid source including Col-H+, where the rate for FeTPP is not measurable. Overall, these pendant bases help to accelerate the catalytic current for HER compared to that for FeTPP. For structurally analogous complexes FeL2 and FeL3 (the distance between the proton bearing a base and iron is the same), the rate is always higher in FeL2, which has a lower pKa (13.11) for the pendant group than does FeL3 as long as the pKa value of the acid source is less than that of the pendant base; i.e., the pendant base is protonated. This is due to the stronger N–H bond strength of the protonated amine with higher pKa in FeL3 (pKa = 16.9), which makes it a weaker proton donor relative to the protonated pyridine in FeL2 (pKa = 13.11). When Col-H+ is used as the acid source, the rate of FeL3 (higher pKa than Col-H+) is greater than that of FeL2 (lower pKa than Col-H+) because the pendant base is protonated in the former and only partially (with ΔpKa ~ 1.6 of pendant bases Py-H+ and Col-H+) in the latter. The CV experiments suggest that the rate-determining step for HER is the protonation of FeIII-H− species. Normally, FOWA yields the rate of the chemical step after the redox event, leading to the formation of an active catalyst (EC), i.e., FeI + H+ → FeIII-H−. However, if the redox event is followed by two consecutive chemical steps (ECC), FOWA should reflect the rate of the second step if that is lower than the rate of the first chemical step, which is the case here (i.e., FeIII-H− + H+ → FeIII + H2).

Table 1.

First-Order Reaction Rate kCA0 (s−1)

| acid (pKa) | FeTPP | FeL2 (13.11) | FeL3 (16.9) | 6LFe (13.11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA-H+ (9.42) | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 10.4 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| DIPA-H+ (10.62) | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| DEA-H+ (11.42) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| Col-H+ (14.98) | ND | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | ND |

The relationship between ΔG (Gibbs free energy of the reaction) and ΔG⧧ (Gibbs free energy of activation) describing the transition state (TS) can be approximated as

| (2) |

where α is the extent of conversion from the reactant to the product and C is the constant.

The rate constant (k) and equilibrium constant (K) are related to ΔG⧧ and ΔG, respectively.

| (3) |

| (4) |

When eqs 3 and 4 are combined in eq 2 and its logarithmic form is taken, the expression becomes

| (5) |

Again, pKa = −ln K.

| (6) |

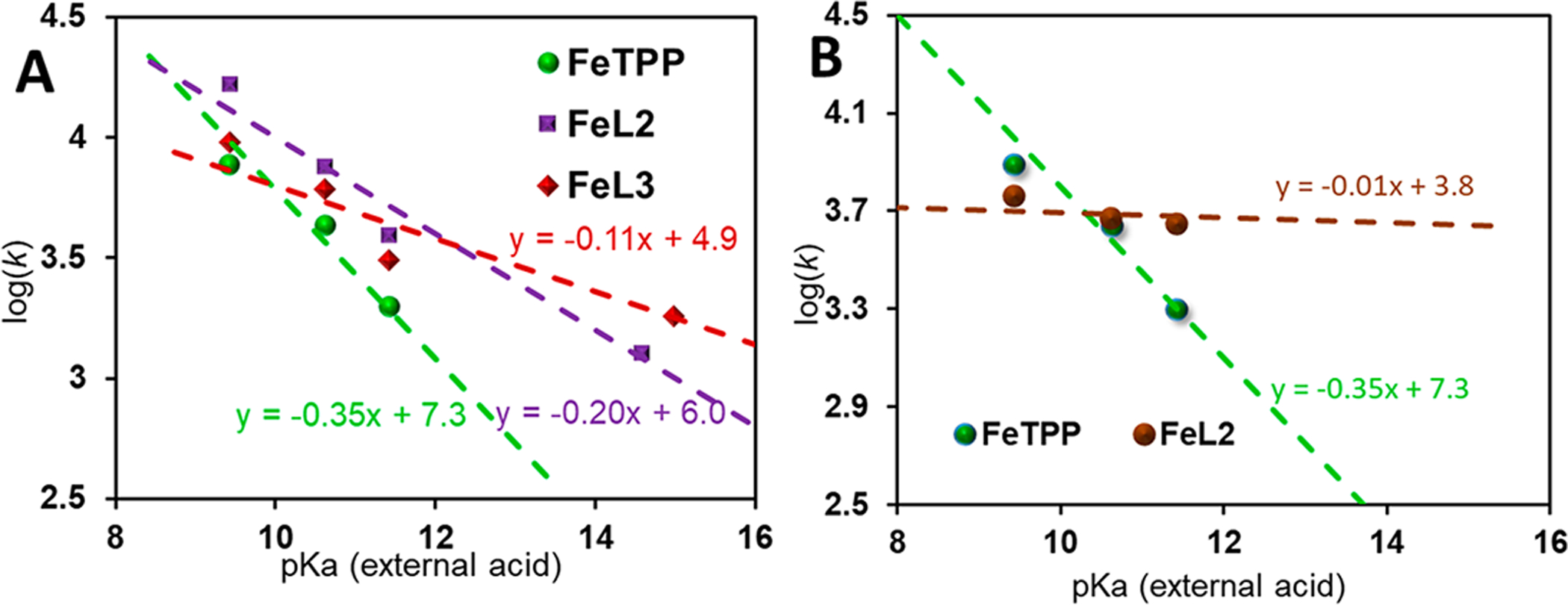

For the set of iron porphyrin complexes used here, FeTPP (Figure 9A, green), FeL2 (Figure 9A, violet), and FeL3 (Figure 9A, red), the log of the rate constant varies linearly with pKa of the acid sources. The slopes obtained from the linear free energy plots are different for these complexes using the same conjugate acid sources having different pKa values. The slopes of the lines are 0.35, 0.20, and 0.11 for FeTPP, FeL2, and FeL3, respectively. The slope of the plot of log(k) versus pKa is indicative of the nature of TS involved in the protonation of a FeIII-H− species according to the previously established assumption where a smaller slope indicates a reactant-like early TS;80 i.e., the extent of proton transfer is less to the FeIII-H− center. The magnitude of the slope is lowest for FeL3, where pKa of the pendant base is the highest (intramolecular proton transfer irrespective of the external acid sources used) and FeTPP, without pendant groups (intermolecular proton transfer), exhibits the highest slope (green trace, Figure 9A,B). Although, qualitatively, the generalization of the pKa dependence of log(rate) seems reasonable, neither FeL2 nor FeL3 shows rates that are independent of pKa of the external acids to suggest purely intramolecular control of the rate-determining FeIII-H− protonation step. To limit any association of the external acid with FeL2 and FeL3 akin to FeTPP, the HER rates were obtained for FeL2 (slope 0.20 in Figure 9A) using 1 M TBAP (Figure S13 and Table S1). The resulting log(k) versus pKa plot for FeL2 approaches linearity (slope 0.01; brown trace, Figure 9B), indicating mostly intramolecular proton transfer to FeIII-H− in the rate-determining step; i.e., the rate of HER becomes almost independent of pKa of the external proton source. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations are used to understand proton transfer to FeIII-H− from the protonated pendant group to obtain insight into the difference in the intramolecular H–H bond formation step between FeL2, FeL3, and 6LFe.

Figure 9.

Plot of log(rate) versus pKa of the external acid source for FeTPP (green), FeL2 (violet), and FeL3 (red) in the presence of 100 mM TBAP (A) and the same for FeTPP (green) and FeL2 (brown) with 100 mM TBAP and 1 M TBAP, respectively (B).

DFT Calculations.

Geometry-optimized DFT calculations are used to investigate the interaction between the protonated distal base and FeIII-H−. Optimized structures show that the FeIII-H− species in both FeL2 and FeL3 show strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between the protonated distal base and hydride ligand (Figure 10A–B) with H---H distances of 1.39 and 1.30 Å, respectively. This interaction is also referred to as a dihydrogen bonding.55,81 The energy difference between the hydrogen-bonded structure and the structure where the hydrogen-bonding BH+ group is rotated away is 8–17 kcal/mol in the gas phase (Figure S14). A similar energy for dihydrogen bonding was estimated for the active site of the mononuclear active site of mononuclear Fe-hydrogenase.81 The optimized structure of the hydrogen-bonded FeIII-H− in a singly protonated 6LFe molecule reveals that the dihydrogen-bonding distance is 3.35 Å (Figure 10C) relative to 1.39 Å (Figure 10A) in FeL2. In fact, the proton appears to be nicely lodged in the proton sponge created by the three pyridines. Logically, this dihydrogen-bonding interaction is weak and is unlikely to contribute to proton transfer to the FeIII-H− species for the catalytic HER. Consistently, 6LFe with three pyridines is much slower toward the catalytic activity from the FeI state than that of FeL2 with only one pyridine (Table 1).

Figure 10.

DFT-optimized structures of (A) FeIIIL2-H−, (B) FeIIIL3-H−, and (C) 6LFeIII-H− with protonated distal bases.

SUMMARY

The pKa values of the different possible protonation events in HER by iron porphyrins are estimated using proton sources with varying pKa values. Protonation of the FeIII-H− species by an external proton source is likely to be the rate-determining step of the HER catalyzed by FeTPP. The role of pendant bases in HER are investigated using a series of synthetic iron porphyrins where both the pKa and number of bases are systematically varied. The results show that the rate-determining step of HER is intramolecular proton transfer from the protonated pendant nitrogen base to a FeIII-H− species. Having pendant residues covalently attached to the porphyrin facilitates this rate-determining protonation step by providing a local source of proton mimicking the desired roles played by such residues in naturally occurring enzyme active sites. The rate of proton transfer is, however, lower for pendant bases with high pKa because of stronger N–H bonds, resulting in more reactant like TS. Importantly, increasing the number of bases results in a lowering of the catalytic rate due to a competing proton sponge effect.

EXPERIMENTAL DETAILS

Materials.

All reagents were of the highest grade commercially available and were used without further purification unless mentioned. The reagents for the synthesis and other chemicals like ferrocene, p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH), bromoaniline, N,N-diethylaniline, 2,6-diisopropylaniline, collidine, and tetrabutylammonium perchlorate (TBAP, [Bu4N][ClO4)]) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The nitrogenous bases were freshly distilled and used after purification whenever it was required, and acetonitrile was dried using the Pure Process Technology solvent system. All of the bases and solvent were degassed using a freeze–pump–thaw technique and stored in an inert-atmosphere glovebox.

Electrochemical Measurement.

All electrochemical experiments were performed using a CH Instruments model CHI710D bipotentiostat electrochemical analyzer. A platinum wire electrode was used as a counter electrode. The measurements were made against a silver wire reference electrode using ferrocene as an internal standard. Anaerobic experiments were performed inside a glovebox under a nitrogen atmosphere. The glassy carbon electrode was used as a working electrode, which was freshly polished to remove all contamination before every use. The polished electrode was then rinsed with water and the solvent used for electrochemical measurements. The electrodes used for homogeneous electrochemistry were purchased from CH Instruments.

Synthesis.

The catalysts (FeL2 and FeL3) were synthesized in our laboratory following an earlier reported procedure.31 6LFe was synthesized in Prof. Karlin’s laboratory following a previous literature report.82 These catalysts are pictorially represented in Figure 1.

CV.

Homogeneous CV experiments were carried out in an acetonitrile solution of a 1 mM/0.5 mM catalyst with 100 mM TBAP (supporting electrolyte) in an electrochemical cell. The scan rate was 100 mV/s in most cases unless mentioned otherwise. An internal standard ferrocence was dissolved in the electrolytic solution, and the potentials are reported with respect to a Fc+/Fc0 couple. A stock solution of ferrocene was prepared, which was added to the solution of the complex before electrochemical measurements. Then two stock solutions of equal strength (250 mM/500 mM) were prepared for the base (B) used and the acid (TsOH). In order to perform the catalysis with different acids, 10 equiv (with respect to the catalyst) of the base to the solution and then increasing equivalents of acid was gradually added up to 10 equiv so that in situ generated conjugate acid [BH+]OTs− behaves as the required acid source. The direct reduction of anilinium is sufficiently negative on glassy carbon such that it does not interfere in the analyzed region.

Bulk Electrolysis and Hydrogen Detection by GC.

Hydrogen evolution was confirmed by controlled potential electrolysis at −1.2 V versus Ag/AgCl in acetonitrile at room temperature. Headspace gas analysis was performed by GC fitted with a thermal conductivity detector using helium as the carrier gas in a sealed electrochemical cell containing a 0.5 mM solution of FeL2, 50 equiv of DEAH+ as a substrate, a glassy carbon working electrode with a large surface area (1 cm2), a platinum counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl/1 M KCl reference electrode. Here, we performed electrolysis at a fixed potential for a certain period under the conditions mentioned above and obtained a substantial amount of H2, which was confirmed by GC.

DFT Calculations.

DFT calculations of the complexes were carried out using the BP86 functional with unrestricted formalism.83–86 For these complexes, a split basis set (6–311g* on the iron atom and 6–31g* on carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms) was used. The frequencies were calculated on the optimized structures. An energy minimum is confirmed by performing frequency calculations on the fully optimized structure using the same basis set as that used for optimization to ensure no imaginary mode is present. The final energy calculations were performed using the 6–311+g* basis set on all atoms in the PCM model using acetonitrile as a solvent and a convergence criterion of 10−10 hartree.87,88 The energies reported are the total free energies computed using zero-point energies and entropy (298 K).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is funded by DST-SERB Grants EMR/2016/008063 and DST/TMD/HFC/2K18/90. S.B. and A.R. acknowledge the Integrated Ph.D. program of IACS. S.H. and K.D.K. acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (USA) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01079.

Additional experimental data, electrochemical data, and optimized coordinates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01079

Contributor Information

Sarmistha Bhunia, School of Chemical Science, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata 700032, India.

Atanu Rana, School of Chemical Science, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata 700032, India;.

Shabnam Hematian, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina 27402, United States;.

Kenneth D. Karlin, Department of Chemistry, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, United States;.

Abhishek Dey, School of Chemical Science, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata 700032, India;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Dogutan DK; Stoian SA; McGuire R; Schwalbe M; Teets TS; Nocera DG Hangman Corroles: Efficient Synthesis and Oxygen Reaction Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nocera DG Chemistry of Personalized Solar Energy. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 10001–10017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lewis NS; Nocera DG Powering the planet: Chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 15729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Fukuzumi S; Yamada Y; Karlin K Hydrogen Peroxide as a Sustainable Energy Carrier: Electrocatalytic Production of Hydrogen Peroxide and the Fuel Cell. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 82, 493–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Boulatov R; Collman JP; Shiryaeva IM; Sunderland CJ Functional Analogues of the Dioxygen Reduction Site in Cytochrome Oxidase: Mechanistic Aspects and Possible Effects of CuB. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 11923–11935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Nocera DG The Artificial Leaf. Acc. Chem. Res 2012, 45, 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).McKone JR; Marinescu SC; Brunschwig BS; Winkler JR; Gray HB Earth-abundant hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 865–878. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bhugun I; Lexa D; Savéant J-M Homogeneous Catalysis of Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution by Iron(0) Porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 3982–3983. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Baffert C; Artero V; Fontecave M Cobaloximes as Functional Models for Hydrogenases. 2. Proton Electroreduction Catalyzed by Difluoroborylbis(dimethylglyoximato)cobalt(II) Complexes in Organic Media. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 1817–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Dey S; Rana A; Dey SG; Dey A Electrochemical Hydrogen Production in Acidic Water by an Azadithiolate Bridged Synthetic Hydrogenese Mimic: Role of Aqueous Solvation in Lowering Overpotential. ACS Catal 2013, 3, 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bhugun I; Lexa D; Saveant J-M Ultraefficient selective homogeneous catalysis of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide by an iron(0) porphyrin associated with a weak Broensted acid cocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 5015–5016. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stolzenberg AM; Strauss SH; Holm RH Iron(II, III)-chlorin and -isobacteriochlorin complexes. Models of the heme prosthetic groups in nitrite and sulfite reductases: means of formation and spectroscopic and redox properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 4763–4778. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rahman MH; Ryan MD Redox and Spectroscopic Properties of Iron Porphyrin Nitroxyl in the Presence of Weak Acids. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 3302–3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Maia LB; Moura JJG How Biology Handles Nitrite. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 5273–5357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kuehnel MF; Orchard KL; Dalle KE; Reisner E Selective Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction in Water through Anchoring of a Molecular Ni Catalyst on CdS Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7217–7223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chen L; Guo Z; Wei X-G; Gallenkamp C; Bonin J; Anxolabéhère-Mallart E; Lau K-C; Lau T-C; Robert M Molecular Catalysis of the Electrochemical and Photochemical Reduction of CO2 with Earth-Abundant Metal Complexes. Selective Production of CO vs HCOOH by Switching of the Metal Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10918–10921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Azcarate I; Costentin C; Robert M; Savéant J-M Through-Space Charge Interaction Substituent Effects in Molecular Catalysis Leading to the Design of the Most Efficient Catalyst of CO2-to-CO Electrochemical Conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 16639–16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Thauer RK The Wolfe cycle comes full circle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 15084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Poulos TL Heme Enzyme Structure and Function. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3919–3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Karlin S; Zhu ZY; Karlin KD The extended environment of mononuclear metal centers in protein structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997, 94, 14225–14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ragsdale SW Metals and Their Scaffolds To Promote Difficult Enzymatic Reactions. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3317–3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lubitz W; Ogata H; Rüdiger O; Reijerse E Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 4081–4148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Babcock GT How oxygen is activated and reduced in respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96, 12971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Collman JP; Sunderland CJ; Boulatov R Biomimetic Studies of Terminal Oxidases: Trisimidazole Picket Metalloporphyrins. Inorg. Chem 2002, 41, 2282–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Higuchi T; Uzu S; Hirobe M Synthesis of a highly stable iron porphyrin coordinated by alkylthiolate anion as a model for cytochrome P-450 and its catalytic activity in oxygen-oxygen bond cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 7051–7053. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Shaw WJ The Outer-Coordination Sphere: Incorporating Amino Acids and Peptides as Ligands for Homogeneous Catalysts to Mimic Enzyme Function. Catal. Rev.: Sci. Eng 2012, 54, 489–550. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bhakta S; Nayek A; Roy B; Dey A Induction of Enzyme-like Peroxidase Activity in an Iron Porphyrin Complex Using Second Sphere Interactions. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 2954–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ahmed ME; Dey S; Darensbourg MY; Dey A Oxygen-Tolerant H2 Production by [FeFe]-H2ase Active Site Mimics Aided by Second Sphere Proton Shuttle. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12457–12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bediako DK; Solis BH; Dogutan DK; Roubelakis MM; Maher AG; Lee CH; Chambers MB; Hammes-Schiffer S; Nocera DG Role of pendant proton relays and proton-coupled electron transfer on the hydrogen evolution reaction by nickel hangman porphyrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111, 15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).McGuire R Jr; Dogutan DK; Teets TS; Suntivich J; Shao-Horn Y; Nocera DG Oxygen reduction reactivity of cobalt(ii) hangman porphyrins. Chem. Sci 2010, 1, 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bhunia S; Rana A; Roy P; Martin DJ; Pegis ML; Roy B; Dey A Rational Design of Mononuclear Iron Porphyrins for Facile and Selective 4e−/4H+ O2 Reduction: Activation of O–O Bond by 2nd Sphere Hydrogen Bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9444–9457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Nichols EM; Derrick JS; Nistanaki SK; Smith PT; Chang CJ Positional effects of second-sphere amide pendants on electrochemical CO2 reduction catalyzed by iron porphyrins. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 2952–2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Margarit CG; Schnedermann C; Asimow NG; Nocera DG Carbon Dioxide Reduction by Iron Hangman Porphyrins. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Vincent KA; Parkin A; Armstrong FA Investigating and Exploiting the Electrocatalytic Properties of Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 4366–4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhang S; Appel AM; Bullock RM Reversible Heterolytic Cleavage of the H–H Bond by Molybdenum Complexes: Controlling the Dynamics of Exchange Between Proton and Hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7376–7387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dutta A; Roberts JAS; Shaw WJ Arginine-containing ligands enhance H2 oxidation catalyst performance. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 6487–6491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Dogutan DK; McGuire R; Nocera DG Electocatalytic Water Oxidation by Cobalt(III) Hangman β-Octafluoro Corroles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 9178–9180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Baran JD; Grönbeck H; Hellman A Analysis of Porphyrines as Catalysts for Electrochemical Reduction of O2 and Oxidation of H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 1320–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Dogutan DK; Bediako DK; Graham DJ; Lemon CM; Nocera DG Proton-coupled electron transfer chemistry of hangman macrocycles: Hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2015, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Frey M Hydrogenases: Hydrogen-Activating Enzymes. ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rakowski DuBois M; DuBois DL The roles of the first and second coordination spheres in the design of molecular catalysts for H2 production and oxidation. Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Ginovska-Pangovska B; Dutta A; Reback ML; Linehan JC; Shaw WJ Beyond the Active Site: The Impact of the Outer Coordination Sphere on Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Production and Oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2621–2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wilson AD; Newell RH; McNevin MJ; Muckerman JT; Rakowski DuBois M; DuBois DL Hydrogen Oxidation and Production Using Nickel-Based Molecular Catalysts with Positioned Proton Relays. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Liu T; Chen S; O’Hagan MJ; Rakowski DuBois M; Bullock RM; DuBois DL Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity of Fe Complexes Containing Cyclic Diazadiphosphine Ligands: The Role of the Pendant Base in Heterolytic Cleavage of H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 6257–6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Wiedner ES; Yang JY; Dougherty WG; Kassel WS; Bullock RM; DuBois MR; DuBois DL Comparison of Cobalt and Nickel Complexes with Sterically Demanding Cyclic Diphosphine Ligands: Electrocatalytic H2 Production by [Co(PtBu2NPh2)-(CH3CN)3](BF4)2. Organometallics 2010, 29, 5390–5401. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Fontecilla-Camps JC; Volbeda A; Cavazza C; Nicolet Y Structure/Function Relationships of [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 4273–4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Nicolet Y; de Lacey AL; Vernède X; Fernandez VM; Hatchikian EC; Fontecilla-Camps JC Crystallographic and FTIR Spectroscopic Evidence of Changes in Fe Coordination Upon Reduction of the Active Site of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 1596–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lee CH; Dogutan DK; Nocera DG Hydrogen Generation by Hangman Metalloporphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 8775–8777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rakowski Dubois M; Dubois DL Development of Molecular Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction and H2 Production/Oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42, 1974–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Stewart MP; Ho M-H; Wiese S; Lindstrom ML; Thogerson CE; Raugei S; Bullock RM; Helm ML High Catalytic Rates for Hydrogen Production Using Nickel Electrocatalysts with Seven-Membered Cyclic Diphosphine Ligands Containing One Pendant Amine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 6033–6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Klug CM; Cardenas AJP; Bullock RM; O’Hagan M; Wiedner ES Reversing the Tradeoff between Rate and Overpotential in Molecular Electrocatalysts for H2 Production. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 3286–3296. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Cardenas AJP; Ginovska B; Kumar N; Hou J; Raugei S; Helm ML; Appel AM; Bullock RM; O’Hagan M Controlling Proton Delivery through Catalyst Structural Dynamics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 13509–13513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Graham D; Nocera D Electrocatalytic H2 Evolution by Proton-Gated Hangman Iron Porphyrins. Organometallics 2014, 33, 4994–5001. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Tshepelevitsh S; Kütt A; Lõkov M; Kaljurand I; Saame J; Heering A; Plieger PG; Vianello R; Leito I On the Basicity of Organic Bases in Different Media. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2019, 2019, 6735–6748. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Rana A; Mondal B; Sen P; Dey S; Dey A Activating Fe(I) Porphyrins for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Using Second-Sphere Proton Transfer Residues. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Queyriaux N; Sun D; Fize J; Pécaut J; Field MJ; Chavarot-Kerlidou M; Artero V Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution with a Cobalt Complex Bearing Pendant Proton Relays: Acid Strength and Applied Potential Govern Mechanism and Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Wang Y; Wang M; Sun L; Ahlquist MSG Pendant amine bases speed up proton transfers to metals by splitting the barriers. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 4450–4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).The Electrochemistry of Metalloporphyrins in Nonaqueous Media. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; Wiley, 1986; pp 435–605. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Lexa D; Rentien P; Savéant JM; Xu F Methods for investigating the mechanistic and kinetic role of ligand exchange reactions in coordination electrochemistry: Cyclic voltammetry of chloroiron(III)tetraphenylporphyrin in dimethylformamide. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem 1985, 191, 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- (60).DeSilva C; Czarnecki K; Ryan MD Reaction of low-valent iron porphyrins with alkyl containing supporting electrolytes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1994, 226, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Kaljurand I; Rodima T; Leito I; Koppel IA; Schwesinger R Self-Consistent Spectrophotometric Basicity Scale in Acetonitrile Covering the Range between Pyridine and DBU. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 6202–6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Lõkov M; Tshepelevitsh S; Heering A; Plieger PG; Vianello R; Leito I On the Basicity of Conjugated Nitrogen Heterocycles in Different Media. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2017, 2017, 4475–4489. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Sooväli L; Kaljurand I; Kutt A; Leito I Uncertainty estimation in measurement of pKa values in nonaqueous media: A case study on basicity scale in acetonitrile medium. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 566, 290–303. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Margarit CG; Asimow NG; Thorarinsdottir AE; Costentin C; Nocera DG Impactful Role of Cocatalysts on Molecular Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Production. ACS Catal 2021, 11, 4561–4567. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Dempsey JL; Brunschwig BS; Winkler JR; Gray HB Hydrogen Evolution Catalyzed by Cobaloximes. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42, 1995–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Grass V; Lexa D; Savéant J-M Electrochemical Generation of Rhodium Porphyrin Hydrides. Catalysis of Hydrogen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 7526–7532. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Rountree ES; Martin DJ; McCarthy BD; Dempsey JL Linear Free Energy Relationships in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: Kinetic Analysis of a Cobaloxime Catalyst. ACS Catal 2016, 6, 3326–3335. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Solis BH; Maher AG; Honda T; Powers DC; Nocera DG; Hammes-Schiffer S Theoretical Analysis of Cobalt Hangman Porphyrins: Ligand Dearomatization and Mechanistic Implications for Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Catal 2014, 4, 4516–4526. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Solis BH; Maher AG; Dogutan DK; Nocera DG; Hammes-Schiffer S Nickel phlorin intermediate formed by proton-coupled electron transfer in hydrogen evolution mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Costentin C; Dridi H; Savéant J-M Molecular Catalysis of H2 Evolution: Diagnosing Heterolytic versus Homolytic Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 13727–13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).McCarthy BD; Martin DJ; Rountree ES; Ullman AC; Dempsey JL Electrochemical Reduction of Brønsted Acids by Glassy Carbon in Acetonitrile—Implications for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 8350–8361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Ghiladi RA; Karlin KD Low-Temperature UV–Visible and NMR Spectroscopic Investigations of O2 Binding to (6L)FeII, a Ferrous Heme Bearing Covalently Tethered Axial Pyridine Ligands. Inorg. Chem 2002, 41, 2400–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Ju TD; Ghiladi RA; Lee D-H; van Strijdonck GPF; Woods AS; Cotter RJ; Young VG; Karlin KD Dioxygen Reactivity of Fully Reduced [LFeII···CuI]+ Complexes Utilizing Tethered Tetraarylporphyrinates: Active Site Models for Heme-Copper Oxidases. Inorg. Chem 1999, 38, 2244–2245. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Costentin C; Drouet S; Robert M; Savéant J-M Turnover Numbers, Turnover Frequencies, and Overpotential in Molecular Catalysis of Electrochemical Reactions. Cyclic Voltammetry and Preparative-Scale Electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 11235–11242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Nicholson RS; Shain I Theory of Stationary Electrode Polarography. Single Scan and Cyclic Methods Applied to Reversible, Irreversible, and Kinetic Systems. Anal. Chem 1964, 36, 706–723. [Google Scholar]

- (76).Saveant JM; Vianello E Potential-sweep chronoamperometry: Kinetic currents for first-order chemical reaction parallel to electron-transfer process (catalytic currents). Electrochim. Acta 1965, 10, 905–920. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Savéant JM; Vianello E Potential-sweep voltammetry: General theory of chemical polarization. Electrochim. Acta 1967, 12, 629–646. [Google Scholar]

- (78).Costentin C; Savéant J-M Multielectron, Multistep Molecular Catalysis of Electrochemical Reactions: Benchmarking of Homogeneous Catalysts. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar]

- (79).Rountree ES; McCarthy BD; Eisenhart TT; Dempsey JL Evaluation of Homogeneous Electrocatalysts by Cyclic Voltammetry. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 9983–10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Leffler JE Parameters for the Description of Transition States. Science 1953, 117, 340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Dey A Density Functional Theory Calculations on the Mononuclear Non-Heme Iron Active Site of Hmd Hydrogenase: Role of the Internal Ligands in Tuning External Ligand Binding and Driving H2 Heterolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 13892–13901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Obias HV; van Strijdonck GPF; Lee D-H; Ralle M; Blackburn NJ; Karlin KD Heterobinucleating Ligand Induced Structural and Chemical Variations in [(L)FeIII-O-CuII]+120 μ-Oxo Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 9696–9697. [Google Scholar]

- (83).Perdew JP Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1986, 33, 8822–8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Becke AD Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Becke AD Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- (86).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Mennucci B; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Caricato M; Li X; Hratchian HP; Izmaylov AF; Bloino J; Zheng G; Sonnenberg JL; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark M; Heyd JJ; Brothers E; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell A; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Rega N; Millam JM; Klene M; Knox JE; Cross JB; Bakken V; Adamo C; Jaramillo J; Gomperts R; Stratmann RE; Yazyev O; Austin AJ; Cammi R; Pomelli C; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Zakrzewski VG; Voth GA; Salvador P; Dannenberg JJ; Dapprich S; Daniels AD; Farkas Ö; Foresman JB; Ortiz JV; Cioslowski J; Fox D J Gaussian 09, C.02 ed.; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (87).Mouesca J-M; Chen JL; Noodleman L; Bashford D; Case DA Density Functional/Poisson-Boltzmann Calculations of Redox Potentials for Iron-Sulfur Clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 11898–11914. [Google Scholar]

- (88).Torres RA; Lovell T; Noodleman L; Case DA Density Functional and Reduction Potential Calculations of Fe4S4 Clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 1923–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.