Abstract

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a potentially fatal hypermetabolic syndrome that occurs when susceptible individuals are exposed to triggering agents. Variability in the order and time of occurrence of symptoms often makes clinical diagnosis difficult. A late diagnosis or misdiagnosis of delayed-onset MH may lead to fatal complications. We herein report a case of delayed-onset MH in the postoperative recovery room. A 77-year-old man awoke from anesthesia and was transferred to the recovery room. Ten minutes after his arrival, his mental status became stuporous and he developed masseter muscle rigidity, hyperventilation, and a body temperature of 39.8°C. The patient was suspected to have MH, and 60 mg of dantrolene sodium (1 mg/kg) was administered via intravenous drip with symptomatic treatment. Within 10 minutes of dantrolene administration, the patient’s clinical signs subsided. This case report demonstrates that rapid diagnosis and treatment are crucial to ensure a good prognosis for patients with MH. A high level of suspicion based on clinical symptoms and early administration of therapeutic drugs such as dantrolene will also improve the clinical course. Therefore, suspicion and prompt diagnosis are absolutely essential. This case report emphasizes the importance of continuous education in the diagnosis and treatment of MH.

Keywords: Malignant hyperthermia, sevoflurane, dantrolene, anesthesia, case report, clinical diagnosis

Introduction

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a potentially fatal hypermetabolic syndrome that develops when susceptible individuals are exposed to triggering agents such as any inhalation anesthetic agent available for general anesthesia (e.g., desflurane, sevoflurane, isoflurane, halothane, or methoxyflurane) and the depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent succinylcholine.1–3 The estimated incidence of MH is 1 per 5000 to 100,000 patients, and the estimated mortality rate may reach 70% to 80% without appropriate treatment. The diagnosis of MH is based on clinical symptoms or laboratory testing. The principal diagnostic features of MH are unexplained elevation of the end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) concentration, hyperthermia, tachycardia, muscle rigidity, and rhabdomyolysis. The prognosis of MH depends on how quickly it is diagnosed and how soon treatment begins. The development of patient monitoring systems has enabled early diagnosis and thus rapid treatment. In addition, treatment with dantrolene sodium was recently reported to reduce the mortality rate to less than 10%.4 Because MH usually occurs immediately after exposure to the triggering factors, symptoms can be seen during the operation, allowing for rapid diagnosis through a variety of monitoring equipment. However, variability in the order and time of occurrence of symptoms often makes clinical diagnosis somewhat difficult. MH that occurs after the end of the operation is particularly difficult to diagnose. In addition, symptoms such as tachycardia and fever should be distinguished from bacteremia, febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, and postsurgical pain. A late diagnosis or misdiagnosis of delayed-onset MH may lead to fatal complications. We herein report a case of postoperative delayed-onset MH that developed in the recovery room. The reporting of this study conforms to the CARE guidelines.5

Case report

A 77-year-old man (155.4 cm in height, 54.4 kg in weight) was diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia with symptoms of nocturia and increased frequency. He was hospitalized to undergo holmium laser enucleation of the prostate with prostate biopsy. His underlying diseases were hypertension and fatty liver. The patient had developed hemiparesis due to an acute infarction of the basal ganglia in 2015, but he had no remaining sequelae. Cilostazol was discontinued 2 weeks before surgery. The patient had no history of general anesthesia, and none of his family members had ever exhibited symptoms of MH. Laboratory tests, a chest X-ray examination, electrocardiography, and pulmonary function testing showed no abnormalities. Transthoracic echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 60.4%, mild to moderate aortic regurgitation, mild aortic stenosis, and mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. On the morning of the patient’s operation, his antihypertensive medication was stopped and his vital signs were stable (blood pressure, 120/70 mmHg; heart rate, 78 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; and body temperature, 36.7°C).

After routine monitoring (pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, and noninvasive blood pressure measurement), general anesthesia was induced with an intravenous bolus injection of propofol (50 mg) and rocuronium (30 mg). Remifentanil was continuously injected at a rate of 0.2 µg/kg/hour. After laryngeal mask airway insertion, anesthesia was maintained using 1.5% sevoflurane and continuous infusion of remifentanil. The patient was mechanically ventilated at a constant tidal volume of 400 mL, and his respiratory rate was 12 breaths/minute during the operation. Immediately after induction of anesthesia, his blood pressure was 114/63 mmHg, heart rate was 60 beats/minute, oxygen saturation was 99%, EtCO2 was 30 mmHg, and bispectral index was 30. The total anesthesia time was 85 minutes. The patient’s vital signs before the end of anesthesia were as follows: blood pressure, 180/90 mmHg; heart rate, 89 beats/minute; body temperature, 37.8°C; oxygen saturation, 99%; and EtCO2, 31 mmHg.

Ten minutes after the patient arrived in the recovery room, he began shivering and developed severe anxiety that did not improve after intravenous injection of a bolus of pethidine (25 mg) and fentanyl (50 µg). His mental status deteriorated to a stupor, and he developed rigidity of the masseter muscles and both arms as well as sudden hyperventilation. He was treated with an oxygen mask (5 L/minute), and his vital signs changed as follows: blood pressure, 220/168 mmHg; heart rate, 134 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 30 breaths/minute; body temperature, 38.1°C; and oxygen saturation, 98%. After 10 minutes, the patient was suspected to have MH with an increased body temperature (39.8°C) and worsening of masseter muscle rigidity. The patient’s MH clinical classification score was 53 points (Tables 2 and 3) before administration of dantrolene sodium, and his diagnosis of MH was classified as “almost certain.” The patient was therefore treated for MH. Aggressive cooling was performed with an ice bag and cold saline, and 100 mg of esmolol in 100 mL of 0.9% normal saline was intravenously administered for heart rate control. An arterial blood gas analysis performed immediately after radial artery cannulation revealed compensated metabolic acidosis [pH, 7.35; partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2), 33 mmHg; partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2), 79 mmHg; and bicarbonate, 18.2 mmol/L]. Follow-up biochemical tests showed increased concentrations of creatine phosphokinase (1735 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase (487 U/L), and myoglobin (2968 ng/mL).

Table 2.

Clinical classification scale for malignant hyperthermia.

| Pathophysiological process | Indicators | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Muscle stiffness | a) Generalized | a) 15 |

| b) Masseter after succinylcholine | b) 15 | |

| 2) Muscle destruction | a) CPK of >20,000 IU/L with succinylcholine | a) 15 |

| b) CPK of >10,000 IU/L without succinylcholine | b) 15 | |

| c) Dark urine | c) 10 | |

| d) Myoglobinuria (myoglobin of >60 µg/L) | d) 5 | |

| e) Myoglobinemia (myoglobin of >170 µg/L) | e) 5 | |

| f) Hyperkalemia (potassium of >6 mEq/L) | f) 5 | |

| 3) Respiratory acidosis | a) PETCO2 of >55 mmHg at proper MPV | a) 15 |

| b) PETCO2 of >60 mmHg in spontaneous ventilation | b) 15 | |

| c) PaCO2 of >60 mmHg at proper MPV | c) 15 | |

| d) PaCO2 of >65 mmHg in spontaneous ventilation | d) 15 | |

| e) Inappropriate hypercapnia | e) 15 | |

| f) Inappropriate tachypnea | f) 15 | |

| 4) Hyperthermia | a) Rapid and inappropriate rise in temperature | a) 15 |

| b) Temperature of >38.8°C (inappropriate) | b) 10 | |

| 5) Heart rhythm | a) Inappropriate sinus tachycardia | a) 3 |

| b) Tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation | b) 3 | |

| 6) Administration of dantrolene | a) Rapid reversal of symptoms | a) 5 |

| 7) Acidemia | a) Arterial base excess (−8 mEq/L) | a) 10 |

| b) Arterial pH of <7.25 | b) 10 | |

|

Score |

Risk |

Rating |

| 0 | Risk 1 | Almost impossible |

| 3–9 | Risk 2 | Unlikely |

| 10–19 | Risk 3 | Less than likely |

| 20–34 | Risk 4 | More than likely |

| 35–49 | Risk 5 | Fairly likely |

| ≥50 | Risk 6 | Almost certain |

CPK, creatine phosphokinase; PETCO2, partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide; MPV, mechanical pulmonary ventilation; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

Table 3.

Clinical indicators of malignant hyperthermia in the present case based on clinical classification scale.

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Pathophysiological process | |

| 1. Generalized muscle stiffness | 15 |

| 2. Muscle destruction Myoglobinemia (>170 µg/L) | 5 |

| 3. Respiratory acidosisInappropriate tachypnea | 15 |

| 4. HyperthermiaRapid and inappropriate rise in temperature | 15 |

| 5. Heart rhythmInappropriate sinus tachycardia | 3 |

| 6. Administration of dantroleneRapid reversal of symptoms | 5 |

| Total score | 58 |

| Probability | Risk of malignant hyperthermia: 6 (almost certain) |

After we obtained consent for treatment from the patient’s legal guardian, 60 mg of dantrolene sodium (1 mg/kg) was prepared and administered by intravenous drip. Within 10 minutes of dantrolene sodium administration, dramatic changes were observed: the patient’s body temperature decreased from 38.3°C to 36.8°C, and his systemic muscle rigidity completely disappeared.

After entry into the intensive care unit, the patient’s consciousness was restored (Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale score of 1) and no remnant muscle rigidity was observed. Although the patient complained of general weakness, his respiratory pattern remained stable. His body temperature on that day was maintained between 36.7°C and 37.5°C. Urinalysis was performed, but the patient was treated with continuous saline irrigation via a Foley catheter after holmium laser enucleation of the prostate, and myoglobinuria was not confirmed because the urine was diluted. The urine was a sanguineous color on gross examination.

On postoperative day 1, the patient developed a mild fever that gradually increased from 37.2°C to 38.2°C. An anteroposterior chest radiograph obtained on the same day revealed mild pulmonary edema. On blood testing, the patient had a white blood cell count of 28,700/µL (neutrophils, 97.2%), hemoglobin concentration of 10.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 31%, platelet count of 74,000/µL, and C-reactive protein concentration of 10.51 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.48, PaCO2 of 28 mmHg, PaO2 of 66 mmHg, bicarbonate concentration of 20.9 mmol/L, and oxygen saturation of 94%. The patient had no muscle rigidity or fever-associated tachycardia, but evidence of infection was found on the laboratory tests. Therefore, antibiotics were started under suspicion of bacteremia.

On postoperative day 2, the patient’s body temperature varied from 37.7°C to 38.6°C. Renal function testing showed improvement in the blood urea nitrogen concentration (19.3 mg/dL) and creatinine concentration (1.15 mg/dL), and the urine was sanguineous in color. The patient’s status continued to improve, and an oral diet was started on postoperative day 4. Klebsiella pneumoniae was identified in blood cultures performed on the day of surgery. He was transferred to the general ward on postoperative day 6 and discharged on postoperative day 12.

The patient was given an explanation of his treatment history before discharge and was informed that MH may recur if general anesthesia is required in the future. Because the patient was elderly, his legal guardians were also given this explanation. We strongly recommended that they inform the medical staff of the patient’s history of MH if general anesthesia is required.

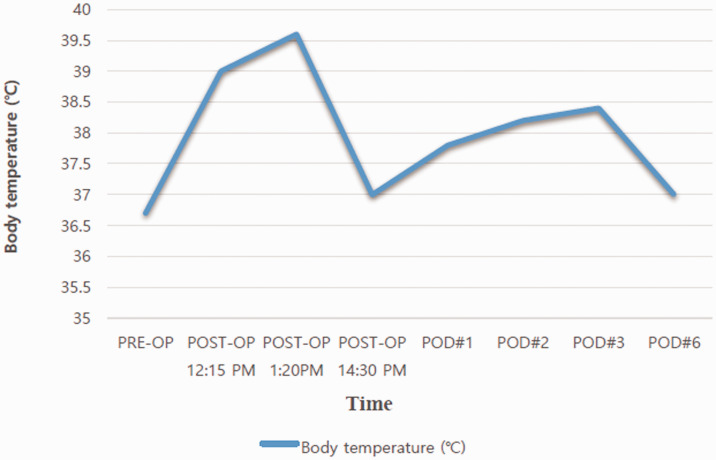

Figure 1 shows the patient’s clinical manifestations and the time course of the therapeutic interventions. Table 1 and Figure 2 show the changes in the patient’s laboratory tests. Figure 3 shows the changes in the body temperature.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the patient’s clinical course. The patient’s clinical manifestations and the time course of the therapeutic interventions are shown.

PACU, postanesthetic care unit; ICU, intensive care unit; RASS-1, Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale score of 1; BT, body temperature; NS, normal saline; M/S, mental status; Dx. r/o, diagnosis rule-out.

Table 1.

Changes in body temperature and laboratory results.

| Variable | Pre-OP | Post-OP |

POD#1 | POD#2 | POD#3 | POD#6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12:15 | 13:20 | 14:30 | ||||||

| pH | 7.44 | 7.35 | 7.43 | 7.41 | ||||

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 35.0 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 35.0 | ||||

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 103.0 | 79.0 | 99.0 | 101.0 | ||||

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 23.8 | 18.2 | 21.9 | 22.2 | ||||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 | 140 | 141 | 141 | 142 | 135 | ||

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.5 | ||

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 14.3 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 8.3 | ||

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.7 | 39.0 | 39.6 | 37.0 | 37.8 | 38.2 | 38.4 | 37.0 |

| AST/ALT (U/L) | 24/13 | 242/114 | 220/137 | 101/73 | 84/64 | 22/27 | ||

| CPK (U/L) | 1735 | 2664 | 687 | 560 | 40 | |||

| LDH (U/L) | 487 | 815 | 546 | 146 | 336 | |||

| BUN/Cr (mg/dL) | 11.7/1.02 | 11.4/1.12 | 15.9/1.23 | 22.4/1.08 | 23.2/1.07 | 16.5/0.87 | ||

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 2968 | 66.48 | ||||||

Pre-OP, preoperatively; Post-OP, postoperatively; POD, postoperative day; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine.

Figure 2.

Changes in laboratory findings.

POST-OP, postoperatively; POD, postoperative day; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Figure 3.

Changes in body temperature.

PRE-OP, preoperatively; POST-OP, postoperatively; POD, postoperative day.

Discussion

MH is diagnosed by the patient’s clinical presentation or laboratory test results. However, clinical symptoms of MH can vary widely depending on the individual, making diagnosis difficult. Most cases of MH develop immediately after exposure to the trigger factors, but delayed onset (from 30 minutes to even 1 week after induction of anesthesia) is rarely reported. Hopkins6 reported that sevoflurane was more likely than other inhalation agents to cause delayed-onset MH (median, 60 minutes; range, 10–210 minutes). In our case, sevoflurane was suspected to be a trigger factor for MH. Symptoms of MH appeared 95 minutes after exposure to the trigger factor. In other words, general anesthesia was performed without any problem prior to the development of MH-like reactions. In addition, the patient was no longer exposed to the trigger when he showed manifestations (Figure 2). His symptoms began to develop 10 minutes after arriving in the recovery room; no residual sevoflurane remained at this time. These points are distinguished from the general pattern of MH, and we diagnosed the patient with delayed-onset MH.

In the North American Malignant Hyperthermia Registry from 1987 to 2006, the most common early symptoms of MH were hypercapnia (92%), sinus tachycardia (73%), and masseter muscle rigidity (27%).7 In this case, the patient had two initial symptoms that led us to strongly suspect MH: sinus tachycardia and masseter muscle rigidity, and these were accompanied by a high fever. The role of hypercapnia, known as the most common initial symptom, was not clear in this case. During intraoperative mechanical ventilation, hypercapnia was associated with the occurrence of atypical tachycardia but increased very mildly. In the recovery room, where other symptoms of MH fully developed, it was difficult to accurately measure the EtCO2 because the patient was under spontaneous mask ventilation. Compensation of PaCO2 and EtCO2 due to hyperventilation may have also disturbed the results. In the arterial blood gas analysis, the PaCO2 was decreased to 33 mmHg because of hyperventilation. Tracheal intubation was considered, but the oxygen mask was maintained because the patient had a good respiratory pattern despite muscle rigidity, and the accompanying acidosis was not severe. The muscle rigidity was initially confined to the masseter muscle but spread systemically over time.

This case illustrates that delayed-onset MH may also occur in the postoperative period when the patient is not immediately exposed to the trigger factor. Rapid diagnosis and treatment are crucial to ensure a good prognosis for patients with MH. Atelectasis, sepsis, and transfusion complications may require differential diagnosis if late symptoms occur. Hypercapnia, which is a commonly known early symptom, is also useful for detection of MH during intraoperative mechanical ventilation; however, it is difficult to measure during postoperative spontaneous ventilation and may be disturbed by various factors. Another important clinical symptom, cola-colored urine, could not be observed in this case because the urine was diluted with irrigation fluid administered during prostatic surgery. Therefore, symptoms such as hypercapnia, fever, muscle rigidity, tachycardia, muscle breakdown, the patient’s history, and the type of surgery should be considered together to achieve a diagnosis. In this case, MH was initially suspected because of the clinical presentation of muscle rigidity, hyperthermia, hypertension, tachypnea, and tachycardia after inhalation anesthesia. The rapid increase in body temperature and oxygen consumption provided strong evidence for suspected MH. The timing of a post-procedure fever can guide the provider’s differential diagnosis and management decisions. In a prospective study involving 81 patients with idiopathic postoperative fever, Garibaldi et al.8 found that 80% of patients who had a fever on the first postoperative day were free of infection. Considering the incidence rate, fever due to infection was excluded in the present case. Other differential diagnoses, such as muscle disease, thyroid toxicity, pheochromocytoma, and withdrawal overdose due to substance abuse, were also excluded based on the preoperative evaluation. The patient’s stable vital signs throughout the operation and in the immediate postoperative period ruled out an iatrogenic cause of the rise in temperature and blood pressure. Postoperative sepsis progresses rapidly as a secondary injury, whereas MH progresses more rapidly and is life-threatening. In the present case, early suspicion and treatment improved the clinical course and prognosis.

Use of a clinical grading scale may help to achieve a diagnosis. Importantly, individualized patient assessment is needed to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis. We established our patient’s treatment protocol based on a clinical diagnosis using the clinical classification scale for MH7 (Table 2). Our patient had sinus tachycardia (unexplained sinus tachycardia, 3 points), muscle rigidity (generalized rigidity, 15 points), muscle destruction (myoglobinemia, 5 points), respiratory acidosis (inappropriate tachypnea, 15 points), and an increased body temperature (>38.8°C, 15 points). Thus, the patient had a raw score of 53 points with an MH rank of 5 (“almost certain”) before administration of dantrolene sodium (Table 3). The diagnosis was particularly suspicious based on the rapid relief of symptoms immediately after administration of dantrolene sodium. If MH is clinically suspected, it is recommended to initiate treatment for MH. Laboratory examinations, urinalysis, chest X-rays, and other tests should be subsequently carried out. Even if a correct diagnosis is made, other accompanying diseases may be masked by MH. Other possibilities need to be assessed even after dantrolene sodium has improved the patient’s symptoms.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of MH is the in vivo contracture test through biopsy. In Korea, however, there are limitations of cost and facilities, and the gold standard test is therefore replaced by clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, institutions that can provide specialized treatments for MH are present in the West, but no such facilities are present in Korea. In the present case, a confirmation test was not performed because of its high cost and patient refusal.

Dantrolene sodium was administered only once in our patient according to the recommendations of the European Malignant Hyperthermia Group, which states that dantrolene should be administered over a period of 4 to 6 hours with a maintenance dose of 1 mg/kg when the initial symptoms are being controlled.9 Our patient’s body temperature rapidly decreased, and his muscle rigidity resolved within 10 minutes. Because of the improvement in his symptoms and development of muscle weakness, which is the most common complication of dantrolene, no additional dose was given.

Conclusion

Episodes of MH are very rare, and modern anesthetic techniques such as increased use of non-triggering intravenous anesthetics and non-use of succinylcholine can degrade clinicians’ awareness of MH. When MH was first identified as an anesthetic complication, the mortality rate was 70% to 80%. However, the introduction of various monitoring methods and the use of dantrolene have dramatically reduced mortality. Although the mortality rates of MH are low, the morbidity rate of MH is still 34.8% according to a recent study.7 This clinical course highlights the importance of continuous education regarding the most effective diagnosis and treatment of MH. It is difficult to differentiate between MH and other diseases after surgery. A high level of suspicion based on clinical symptoms and early administration of therapeutic drugs such as dantrolene can improve the patient’s clinical course. Therefore, high suspicion and prompt diagnosis by physicians are absolutely essential. We hope that the present case report will help clinicians to suspect MH when encountering similar cases.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: JY Min: wrote the final manuscript. SH Hong, SJ Kim: collected and analyzed the data. MY Chung: wrote the manuscript as a corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This is a case report; therefore, ethics approval was not required. We treated the patient according to an established regimen with no complications. The patient’s legal guardian provided written informed consent for the treatment. The patient’s details were de-identified; therefore, patient consent for publication was not required.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Mee Young Chung https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1450-8724

References

- 1.Smith JL, Tranovich MA, Ebraheim NA.A comprehensive review of malignant hyperthermia: preventing further fatalities in orthopedic surgery. J Orthop 2018; 15: 578–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferhi F, Dardour L, Tej A, et al. Malignant hyperthermia in a 4-year-old girl during anesthesia induction with sevoflurane and succinylcholine for congenital ptosis surgery. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2019; 33: 183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumitani M, Uchida K, Yasunaga H, et al. Prevalence of malignant hyperthermia and relationship with anesthetics in Japan: data from the diagnosis procedure combination database. Anesthesiology 2011; 114: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glahn K, Ellis FR, Halsall PJ, et al. Recognizing and managing a malignant hyperthermia crisis: guidelines from the European Malignant Hyperthermia Group. Br J Anaesth 2010; 105: 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagnier JJ, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus‐based clinical case reporting guideline development 2013; Wiley Online Library. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins P.Malignant hyperthermia: pharmacology of triggering. Br J Anaesth 2011; 107: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larach MG, Gronert GA, Allen GC, et al. Clinical presentation, treatment, and complications of malignant hyperthermia in North America from 1987 to 2006. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garibaldi RA, Brodine S, Matsumiya S, et al. Evidence for the non-infectious etiology of early postoperative fever. Infect Control 1985; 6: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg H, Pollock N, Schiemann A, et al. Malignant hyperthermia: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015; 10: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]