Abstract

Bone skeletal alterations are no longer considered a rare event in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), especially at more advanced stages of the disease. This study is aimed at elucidating the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. Bone marrow stromal cells, induced to differentiate toward osteoblasts in osteogenic medium, appeared unable to complete their maturation upon co-culture with CLL cells, CLL-cell-derived conditioned media (CLL-cm) or CLL-sera (CLL-sr). Inhibition of osteoblast differentiation was documented by decreased levels of RUNX2 and osteocalcin mRNA expression, by increased osteopontin and DKK-1 mRNA levels, and by a marked reduction of mineralized matrix deposition. The addition of neutralizing TNFα, IL-11 or anti-IL-6R monoclonal antibodies to these cocultures resulted in restoration of bone mineralization, indicating the involvement of these cytokines. These findings were further supported by silencing TNFα, IL-11 and IL-6 in leukemic cells. We also demonstrated that the addition of CLL-cm to monocytes, previously stimulated with MCSF and RANKL, significantly amplified the formation of large, mature osteoclasts as well as their bone resorption activity. Moreover, enhanced osteoclastogenesis, induced by CLL-cm, was significantly reduced by treating cultures with the anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody infliximab. An analogous effect was observed with the use of the BTK inhibitor, ibrutinib. Interestingly, CLL cells co-cultured with mature osteoclasts were protected from apoptosis and upregulated Ki-67. These experimental results parallel the direct correlation between amounts of TNFα in CLL-sr and the degree of compact bone erosion that we previously described, further strengthening the indication of a reciprocal influence between leukemic cell expansion and bone structure derangement.

Introduction

In patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) skeletal erosion can be demonstrated by computed tomography scans of long bone shafts in subjects with more advanced disease (Binet C vs. Binet A).1,2 Moreover a few cases of CLL/smallcell lymphocytic lymphoma show osteolysis along with hypercalcemia.3-7 Axial bone structure alterations appear more frequently in CLL patients than in age-matched controls.8 However, the mechanisms underlying bone erosion in CLL patients have not been elucidated so far, and may be part of a complex set of events participating in disease pathogenesis. Recent evidence demonstrated that mutual interactions between stromal and leukemic cells facilitate survival and expansion of the neoplastic clone9-13 and contemporarily affect functions of microenvironmental cells. We previously described a direct correlation between the levels of RANKL (nuclear factor-κB ligand) expression on CLL cells and the degree of bone erosion in CLL patients.2

We suggested that leukemic cells, progressively infiltrating bone marrow, may affect the differentiation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, ultimately leading to alterations of physiological bone remodeling. RANKL, expressed by osteoblasts, is the major cytokine regulating osteoclast differentiation after binding to RANK+ monocytes. Osteolytic bone lesions are considered a hallmark of multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cells show high RANKL expression and secretion; in this disease, the interactions between malignant plasma cells, releasing RANKL, and the bone microenvironment progressively undermine the integrity of bone structures due to stimulation of osteoclast activity and subsequent excessive bone resorption. 14-16 RANKL is also expressed at high levels in malignant CLL cells but, at difference from multiple myeloma cells, CLL cells release it only in exceptional cases.17 Borge et al. detected high levels of plasma RANKL (800 pg/mL) in one CLL patient with lytic bone lesions and demonstrated that, in vitro, leukemic B cells released large amounts of RANKL (1,600 pg/mL) after stimulation with CpG.3 However, RANKL stimulation induces the production of pro-osteoclastic cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 by CLL cells.17,18 Therefore, several growth factors may contribute to the microenvironment/leukemic B-cell crosstalk that governs bone homeo stasis.

Based on these premises we investigated whether cytokines secreted by leukemic cells participate in bone alterations in CLL patients. Some evidence, reported here, indicates that released CLL cytokines prevent osteoblastinduced bone formation and contemporarily stimulate the expansion of osteoclast progenitors or of fully mature osteoclasts. Collectively, these observations suggest that the disruption of the physiological bone marrow niche may create favorable conditions for CLL-cell expansion. The demonstration that the survival/expansion of leukemic cells appears to be promoted by activated osteoclasts is relevant to this notion.

Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Genoa, Italy). Forty-five patients were included in the study: 19 had Binet stage A, 17 had stage B and 9 had stage C. MEC-1 cells, obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (German cell line collection) were used in selected experiments. Details of all the Methods are provided in the Online Supplementary File.

Osteoblast generation

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC), previously expanded,12 were osteogenically induced, co-cultured with CLL B cells (contact/ transwell), CLL-cell conditioned media (CLL-cm) or CLL sera (CLL-sr) for 5 more days (Online Supplementary Figure S1), detached and processed.

Messenger RNA extraction, reverse transcription and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to assess the expression of GAPDH, osteopontin (OP), osteocalcin (OC), RUNX2, Dikkpof-1 (DKK-1), cathepsin K (Cat-K), NFATc-1 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9).

Evaluation of matrix deposition

Alizarine staining was performed, using a commercial kit, on paraformahaldeyde-fixed cultures of osteo-induced BMSC, under different treatments.

Short-interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of specific cytokines in MEC-1 or CLL cells

All the short-interfering RNA (siRNA) used, (non-specific and specific for TNFα, IL-6, and IL-11) were obtained commercially.

Osteoclast generation

Monocytes purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy donors or from CLL patients were induced to differentiate toward osteoclasts and then cultured under different conditions (Online Supplementary Figure S1): CLL-cm with/without neutralizing anti-cytokine/receptor monoclonal antibodies, ibrutinib, denosumab, or from cytokine-silenced CLL cells.

TRAP staining and bone resorption assay

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) was detected using a commercial kit. Osteoclast activity was evaluated by sizing resorption pits produced in an inorganic crystalline material.

Viability and cell cycle evaluation of CLL B cells co-cultured with osteoclasts

Osteoclasts derived at 14 days were co-cultured with CLL cells and apoptosis of leukemic cells was determined through DiOC6 staining19 or by propidium iodide cell cycle-phase distribution through multiparameter flow cytometric analysis.20 Ki-67 expression was also determined by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemical analyses of bone biopsies

B5-fixed, decalcified and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned, de-paraffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 5% H2O2; serial sections were immunostained for TRAP and CD79a.

Cytokine levels in cultured-cell media and murine CLL sera

Human TNFα levels in media from osteo-induced BMSC and CLL cells were determined using a Millipore Milliplex kit. We further determined human TNFα levels in sera of mice displaying documented bone loss after human CLL-cell engraftment.2 The amounts of TNFα in co-cultures of monocytes, differentiating toward osteoclasts under various conditions – with monocyte colony-stimulating factor (MCSF)+RANKL, MCSF+RANKL+CLLcm or MCSF+CLL-cm only – were assessed through a qualitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and compared. The levels of TNFα, IL-11 or IL-6 in conditioned medium of CLL-cm, per se, or upon cytokine-knockdown, were determined using the same approach.

Gene expression profiling

Gene expression of B cells from CLL samples and normal peripheral blood lymphocytes was profiled on a GeneChip Gene 1.0 ST array.21

Statistics

Two-sided Student t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests with Fisher correction were used. All the data sets had a normal distribution. The levels of statistical significance are denoted by *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01 or ***P≤0.001.

Results

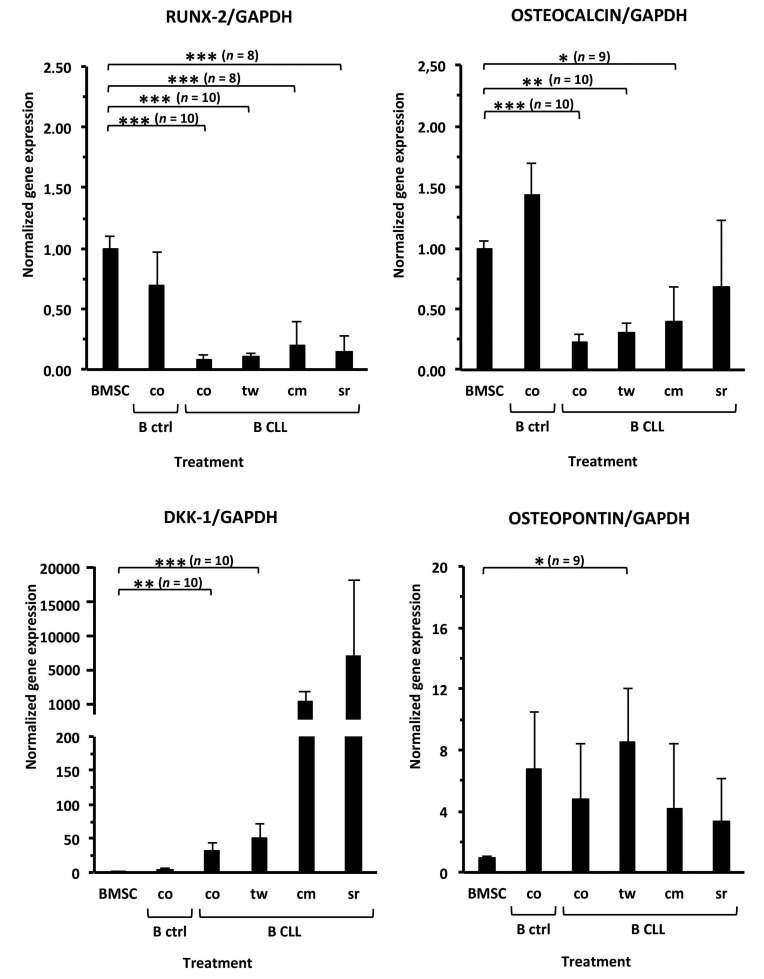

The terminal differentiation of osteo-induced bone marrow stromal cells is inhibited by the addition of CLL cells, CLL-conditioned media or CLL-sera

Normal donor BMSC were induced to differentiate toward osteoblasts and then co-cultured with CLL cells (contact/transwell), CLL-cm or CLL-sr (Online Supplementary Figure S1A). After 5 days of co-culture, osteoinduced BMSC were evaluated for RUNX2, osteocalcin, DKK1 and osteopontin mRNA levels by quantitative RTPCR. RUNX2, the master gene regulating the osteoblastogenic cascade, appeared significantly downregulated by the presence of CLL cells, CLL-cm or CLL-sr, but not by normal B cells (Figure 1). Osteocalcin levels, which are normally high in fully differentiated osteoblasts, were also significantly reduced. In contrast, DKK-1, a canonical WNT inhibitor, appeared highly upregulated with a clear trend in all the experimental conditions. Osteopontin mRNA was also enhanced, although even by the presence of normal B cells. Collectively, these findings indicate that CLL cells affect the expression of the major osteoblast-related genes and inhibit differentiation of BMSC towards osteoblasts.

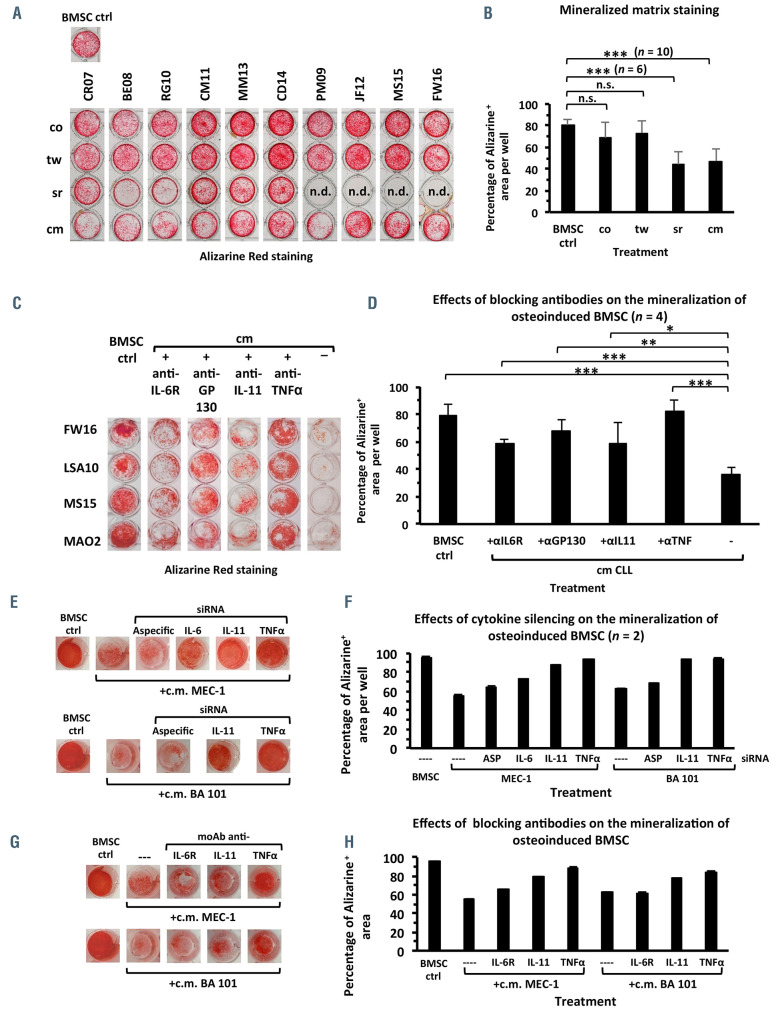

Reduced extracellular matrix deposition by osteo-induced bone marrow stromal cells cultured with CLL cells, CLL-conditioned media or CLL sera

The inhibition of osteoblast differentiation by CLL cells was also confirmed through the evaluation of matrix mineralization levels. According to Alizarine Red staining, mineralized areas appeared consistently reduced, with the strongest inhibition of matrix deposition occurring in the presence of CLL-cm or CLL-sr (Figure 2A, B). Based on literature data22-24 we investigated whether IL-6, IL-11 and TNFα could represent candidate cytokines mediating the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation. The effect of an anti-GP130 monoclonal antibody was also tested because this molecule, shared by different cytokines of the IL-6 family, is pivotal in signal transduction. Monoclonal antibodies neutralizing the above mentioned cytokines (IL-11, TNFα) or blocking binding to their receptors (IL-6R, GP130) were thus added, together with CLL-cm, to cultures of osteoinduced BMSC. All these monoclonal antibodies, but not an isotype-specific control (Online Supplementary Figure S2A), counteracted suppression of in vitro mineralized matrix deposition, which was significantly higher after the addition of infliximab (Figure 2C, D). Cultures of osteo-induced BMSC with conditioned media from the TNFα-, IL-6-, or IL-11- RNA-silenced MEC-1 cell line or primary leukemic cells (BA101), further confirmed involvement of these cytokines in the impairment of osteoblast differentiation (Figure 2E-H and Online Supplementary Figure S2A, B). Moreover the increase in mineralized matrix deposition, detected in osteo-induced BMSC cultured with CLL-cm + neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, was paralleled by the restoration of higher levels of both RUNX2 and osteocalcin mRNA (Online Supplementary Figure S2C, D). Evidence of decreased pSTAT3(ser727) and AKT expression in CLL-cm-treated BMSC versus CLL-cm + Infliximab or in basal conditions, suggests the participation of these signaling pathways in the regulation of osteogenesis by CLL-released TNFα (Online Supplementary Figure S2E, F).

The observation of higher mRNA expression for IL-11 and IL-11 receptor A (IL-11RA) in CLL cells than in control B cells, by gene expression profiling analysis, highlight IL-11 as a cytokine released by CLL cells (Online Supplementary Figure S4). An association between increased levels of IL-6 produced by CLL cells and worse clinical outcomes has been reported recently.25 The substantial amounts of TNFα, present in conditioned media derived from CLL cells cultured alone (basal conditions: Control), but significantly reduced in media from CLL/BMSC co-cultures (Online Supplementary Figure S5), suggest that TNFα, constitutively secreted by CLL cells and metabolically active, plays a role in suppressing osteoblast differentiation.

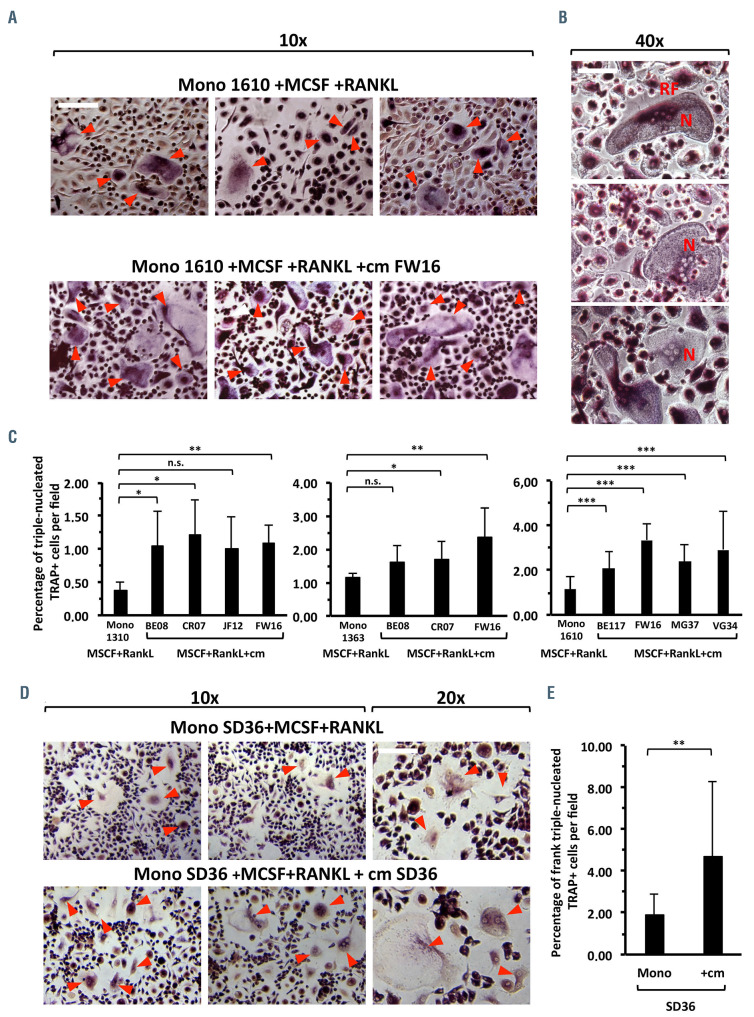

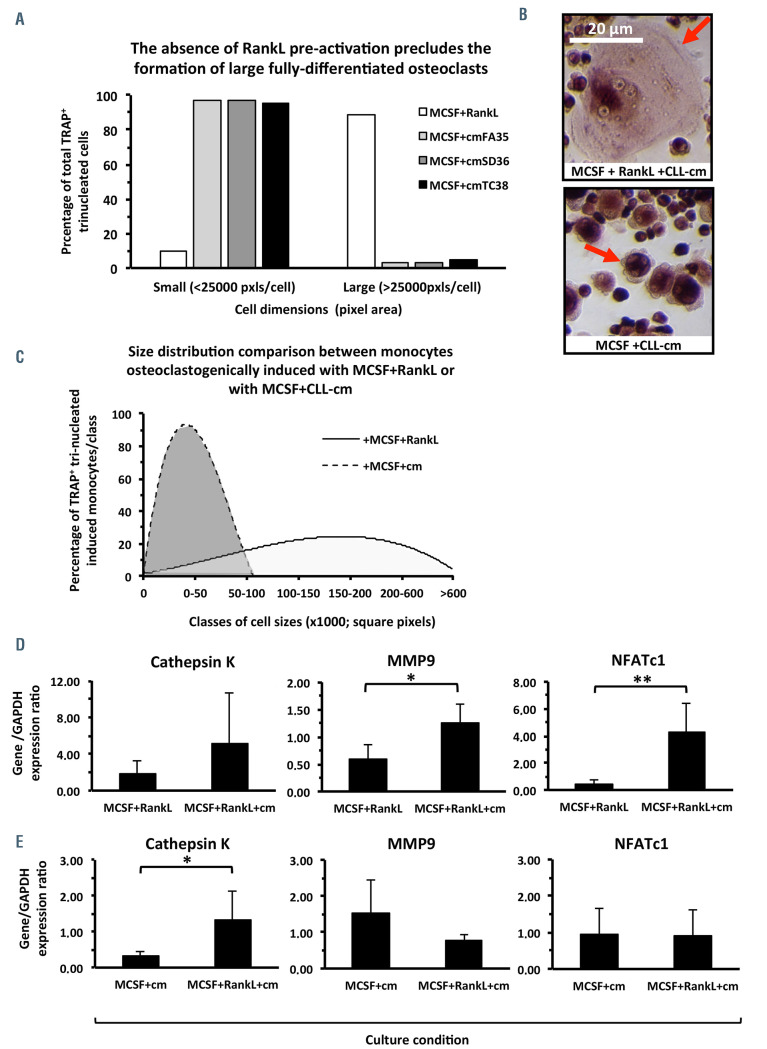

Enhancement of differentiation of allogeneic or autologous monocytes into osteoclasts by CLL-conditioned media

Next we investigated whether the presence of CLL-cm could affect osteoclastogenic differentiation of monocytes in vitro. Purified and pre-activated monocytes, from peripheral blood of healthy donors or of CLL patients, were challenged with CLL-cm, or medium only, for 7 days (Online Supplementary Figure S1). The number of osteoclasts, evaluated by counting the number of TRAP+ cells with three or more nuclei, increased significantly after the addition of CLL-cm (Figure 3A, C). Moreover osteoclasts derived under this condition appeared larger than those in control cultures, fully differentiated and characterized by multiple nuclei: a canonical ruffle border was sometimes evident (Figure 3B). The enhancement in osteoclast differentiation was also detectable when the same experiment was performed in an autologous setting (Figure 3D, E). A considerable reduction in the number of large multinucleated cells was however observed when monocytes were stimulated without RANKL in the induction phase (MCSF+CLLcm only). Under this condition, a consistent number of trinucleated TRAP+ cells appeared drastically smaller, in comparison to osteoclasts present in control cultures derived with exogenous RANKL. We were thus prompted to evaluate the relative proportions of TRAP+ tri-nucleated small or large cells. Figure 4A and B show that, while pre-stimulation of monocytes with MCSF+RANKL, with or without CLL-cm, led to their complete maturation, inducing a higher number of typical, multinucleated osteoclasts, the addition of MCSF+CLL-cm alone failed to achieve the same effect, consistently impairing the generation of large osteoclasts (Figure 4C and Online Supplementary Figure S6). Low levels of soluble RANKL, found in media derived from cultured CLL cells (n=10; data not shown), could thus promote initial osteoclast differentiation only. It is however evident that factors released by CLL cells synergize with RANKL, when exogenously added, thus causing a significant amplification of osteoclastogenesis. This observation also appears to be sustained by the finding that mRNA expression of cathepsin K, MMP9, and NFATc1, which are pivotal in osteoclast differentiation, is higher in monocytes stimulated with MCSF+RANKL and CLL-cm than in monocytes treated with MCSF+RANKL only (Figure 4D). A statistically significant reduction was also observed in cathepsin K transcript levels when the culture condition included CLLcm but was devoid of RANKL (Figure 4E).

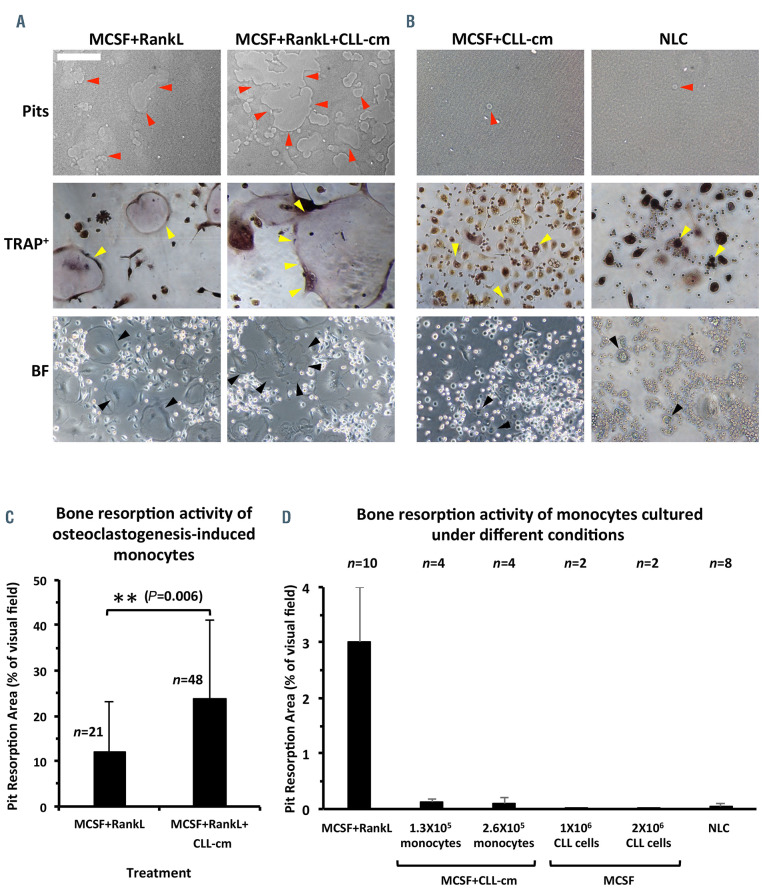

Osteoclasts derived in the presence of MCSF+RANKL and CLL-conditioned media show higher bone resorption activity

We then observed that only large, fully differentiated and multinucleated osteoclasts, derived after MCSF+RANKL stimulation, show significant bone resorption activity and larger erosion areas were detected when CLL-cm was concomitantly added in these cultures (Figure 5A-C). Small tri-nucleated cells, generated with MCSF+CLL-cm only, although TRAP+, produced very small detectable erosion pits (Figure 5B). Similar results were obtained when an increased number of RANKL+ CLL cells (from 1x106 to 2x106/well) were added with MCSF, instead of the conditioned medium, attempting to compensate for the lack of soluble RANKL. Incrementation of the number of seeded monocytes (from 1.3x105/well to 2.6x105/well), cultured with MCSF+CLL-cm, also failed to give rise to mature osteoclasts that were fully competent at matrix erosion. The ability to erode bone does, therefore, appear to be strictly related to the presence of large, fully differentiated osteoclasts, characterized by a typical sealing zone. Nurse-like cells, tumor-associated macrophages typically found in the CLL microenvironment,11,26 although TRAP+, were also devoid of bone surface resorbing activity (Figure 5D).

Figure 1.

The addition of CLL conditioned media, CLL sera or CLL cells to osteo-induced bone marrow stromal cells impairs their differentiation. The addition of CLL conditioned medium (cm), CLL sera (sr) or CLL cells, in contact (co) or in transwell (tw), to cultures of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC), induced to differentiate in standard osteogenic medium, inhibited their complete differentiation to osteoblasts. RUNX2 and osteocalcin transcript levels were significantly decreased. In contrast, DKK-1 and osteopontin mRNA levels were increased when CLL-cm, CLL-sr or CLL cells were added to the cultures, as compared with levels when control BMSC were cultured with osteogenic medium only. Given the extremely high average and corresponding standard deviation values of DKK-1 mRNA levels, statistical significance was not achieved for CLL-cm and CLL-sr treatment. The mRNA expression of the same genes of interest was also evaluated in co-cultures of B cells purified from normal controls (B ctrl). n: number of cases examined for each experimental condition.

Figure 2.

The addition of CLL conditioned media, CLL sera or CLL cells to osteo-induced bone marrow stromal cells impairs mineralized matrix deposition, as revealed by Alizarine Red staining. (A, B) When CLL conditioned media (cm), CLL sera (sr) or CLL cells, in contact (co) or in transwell (tw), were added to bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) induced to differentiate in standard osteogenic medium a reduced deposition of mineralized matrix was detected. This effect was particularly and significantly evident in the presence of CLL-cm or CLL-sr (P<0.001). (C, D) The inhibition of mineralized matrix deposition, due to the addition of CLL-cm derived from four CLL patients (FW16, LSA01, MS15, MAO2), was counteracted by neutralizing anti-TNFα, anti-IL-11 monoclonal antibodies (moAb) or anti-IL-6R,and anti- GP130 moAb. The anti-TNFα moAb infliximab showed a higher efficiency in restoring mineralization. (E, F) The addition of conditioned medium (cm) derived from cultures of IL-6-, IL-11-, or TNFα-silenced MEC-1 cells or leukemic CLL cells (BA101) restored mineralization by osteo-induced BMSC, as shown in a representative well of two assessed. (G, H) In parallel, neutralizing moAb for the same cytokines rescued matrix mineralization. Histogram bars depict the percentage of Alizarinepositive area of each well.

Figure 3.

Enhancement of osteoclast differentiation following the addition of CLL conditioned media to cultures of monocytes, from healthy donors or CLL patients, pre-stimulated with MCSF+RANKL. (A) The addition of CLL conditioned medium (cm) enhances osteoclast differentiation of healthy monocytes pre-stimulated with MCSF and RANKL, as shown here with conditioned medium from a representative case (cm FW16). The number of osteoclasts was determined by counting the number of TRAP+ cells which were at least tri-nucleated. (B) Osteoclasts generated with the addition of CLL-cm show a typical morphology of multinucleated (N) large cells with a ruffle border (RF). (C) The addition of CLL-cm derived from cultures of CLL cells from different patients (BE08, CRO7, JF1h2, FW16, BE117, MG37, VG34) to monocytes purified from three healthy donors (1310, 1363, 1610) significantly increased the differentiation of monocytes, previously stimulated with MCSF+RANKL, to osteoclasts. (D, E) CLL-cm from CLL patient SD36 was added to autologous monocytes, previously stimulated with MCSF+RANKL: also in this auto - logous setting, a significant enhancement of osteoclast differentiation was observable. For the images magnified 10X, 20X or 40X, the bars represent 25, 12.5 or 6.25 μm, respectively.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the size of osteoclasts derived from monocytes cultured with MCSF and CLL-conditioned media in the presence or absence of RANKL, and of the mRNA expression of key molecules involved in this process. (A, B) TRAP+ cells, at least tri-nucleated, derived in the presence of MCSF+CLL-conditioned media (cm) (n=3; FA35, SD36, TC38) were smaller than osteoclasts classically derived with MCSF+RANKL or MCSF+RANKL+CLL-cm. (C) Size distribution of osteogenically induced monocytes with MCSF+RANKL or MCSF+CLL-cm. The curves depict the percentages of cells that fall within the limits of each class size (square pixels). (D) Cathepsin K, MMP9 and NFAT-C1 mRNA levels were higher in osteoclasts derived with CLL-cm. (E) The levels of cathepsin K mRNA expression were significantly higher in osteoclasts derived with CLL-cm in the presence of RANKL than without RANKL.

Figure 5.

The addition of CLL-conditioned media enhances the resorption activity of MCSF+RANKL-derived osteoclasts. (A) Osteoclasts derived in the presence of CLLconditioned media (cm) showed a significant enhancement in bone resorption activity in comparison with controls derived with only MCSF+RANKL. Images are representative of two different experiments with CLL-cm derived from three CLL patients. (B) On the other hand, osteoclasts derived in the presence of MCSF+CLL-cm, without RANKL pre-activation, created a few pits of resorption. Nurse-like cells (NLC), although TRAP+, did not resorb bone. Images are representative of two experiments. (C) The addition of CLL-cm to MCSF-RANKL pre-stimulated monocytes significantly increased the ability of osteoclasts to resorb bone; n: number of visual fields assessed in two different experiments and CLL-cm derived from three CLL patients. (D) Increasing the number of seeded monocytes (1.3x105 or 2.6x105/well) stimulated with MCSF only did not result in enhanced resorption activity. Increasing the number of CLL cells (1x106 or 2x106/well) expressing RANKL on their surface was also not sufficient to compensate for the lack of soluble RANKL. NLC did not display bone resorbing activity n: number of visual fields assessed in two experiments.

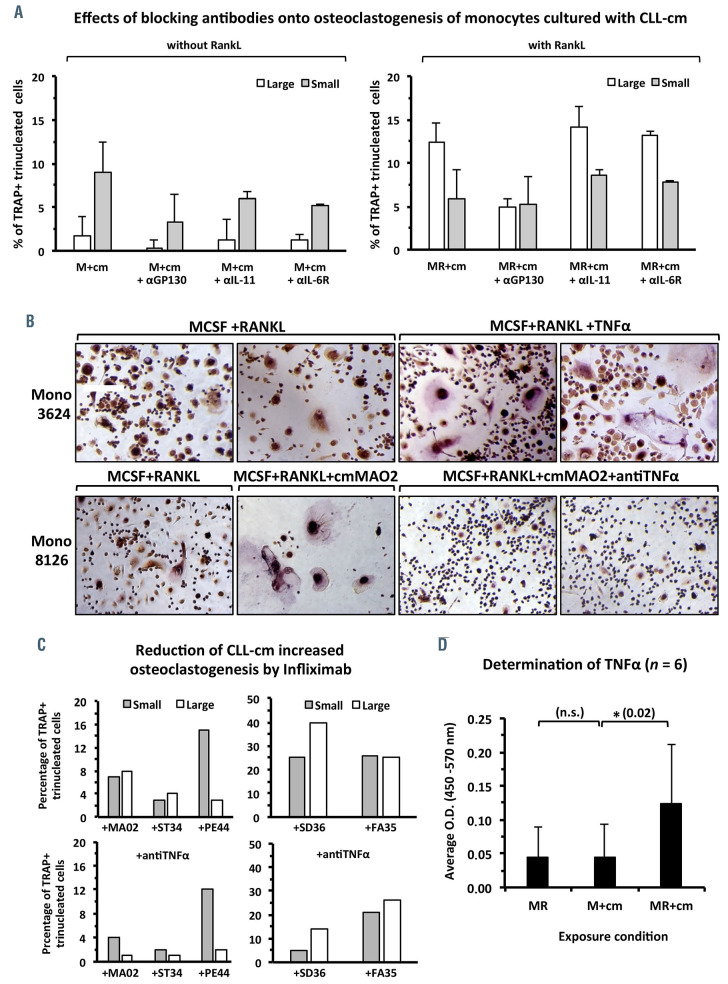

Involvement of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-11 in enhanced osteoclast maturation by CLL-conditioned media

To assess whether TNFα, IL-6 and IL-11 could be involved in enhanced formation of osteoclasts by CLL-cm, we added neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for TNFα and IL-11 or anti-IL-6R and anti-GP130 monoclonal antibodies to cultures of monocytes stimulated with MCSF+CLL-cm, with or without previous RANKL activation. Anti-IL-6R and anti-IL-11 monoclonal antibodies reduced monocyte osteoclastogenesis in the absence of RANKL pre-stimulation only, while the anti-GP-130 mono clonal antibody also acted in the presence of RANKL (Figure 6A). Infliximab (anti-TNFα), on the other hand, inhibited differentiation of large, multinucleated osteoclasts, previously activated with MCSF+RANKL (Figure 6B, C). Together, these observations suggest that IL-6 and IL-11 drive monocytes toward an initial stage of osteoclast maturation, while TNFα, in synergy with RANKL, plays a key role in the differentiation of fully competent, multi - nucleated osteoclasts. Conditioned media from TNFα- silenced MEC-1 cells weakly decreased the formation of large osteoclasts and increased the number of small trinucleated TRAP+ cells (Online Supplementary Figure S7). Higher levels of TNFα were also detected in media recovered from MCSF+RANKL-activated monocytes cultured in the presence of CLL-cm than in any of the other experimental conditions (Figure 6D). Data derived from experiments in a CLL mouse model, which results in derangement of bone structure following leukemic cell engraftment, 2 appear in line with these observations. Moreover TNFα levels, found in mouse sera but of human source, appeared increased from the third to the sixth weeks after CLL cell injection (Online Supplementary Figure S8). Collectively these observations suggest that TNFα may have a key role in impairment of physiological bone remodeling in CLL patients. Of note, the concentration of TNFα in sera directly correlated with the degree of bone erosion in CLL patients.2

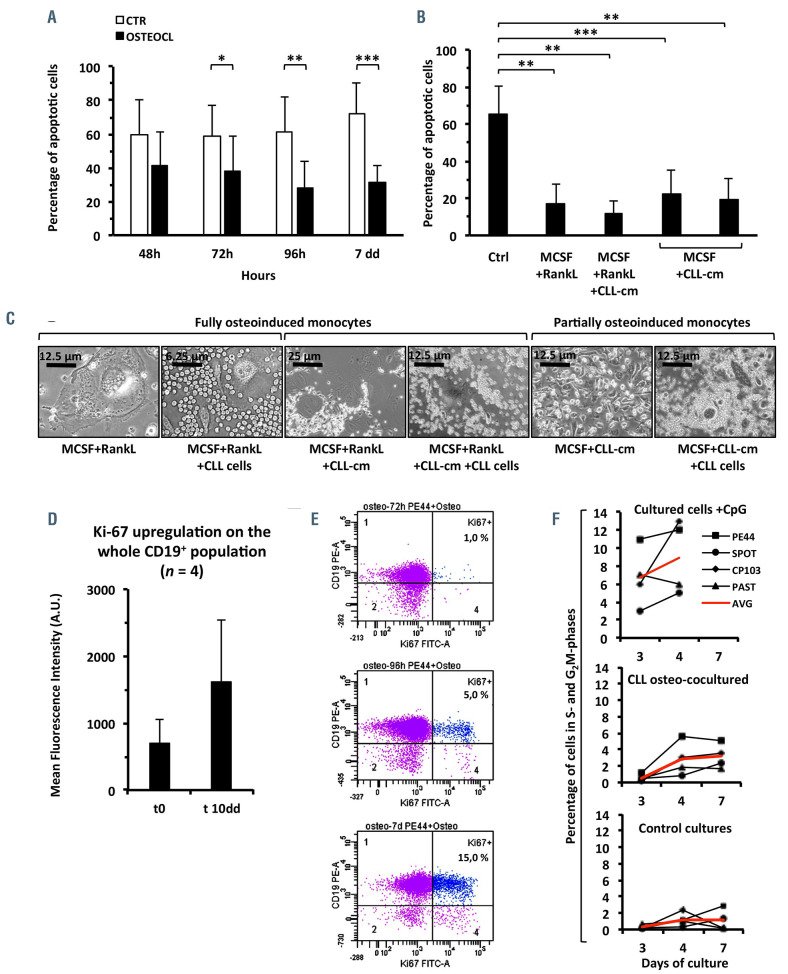

Osteoclasts support CLL viability in vitro

To investigate whether osteoclasts support leukemic cell viability we generated fully differentiated osteoclasts and then co-cultured them with CLL cells, while measuring apoptosis during time-course experiments. Osteoclasts significantly prevented CLL cells from spontaneous apoptosis (Figure 7A). Interestingly also small, TRAP+, trinucleated cells, derived by treating monocytes with MCSF and CLL-cm, without RANKL, displayed analogous effects (Figure 7B). Bright field images (Figure 7C) show viable leukemic B cells surrounding large classical osteoclasts or smaller osteoclast precursors in in vitro coculture. While assessing whether osteoclasts could stimulate CLL-cell proliferation, we determined that, after coculture with osteoclasts, Ki-67 was upregulated on the whole leukemic population but scored markedly positive in a limited fraction of cells (Ki-67 bright: Figure 7D, E). Accordingly, only a limited number of cells was induced by the osteoclasts to progress through the cell cycle along the experiment (Figure 7F).

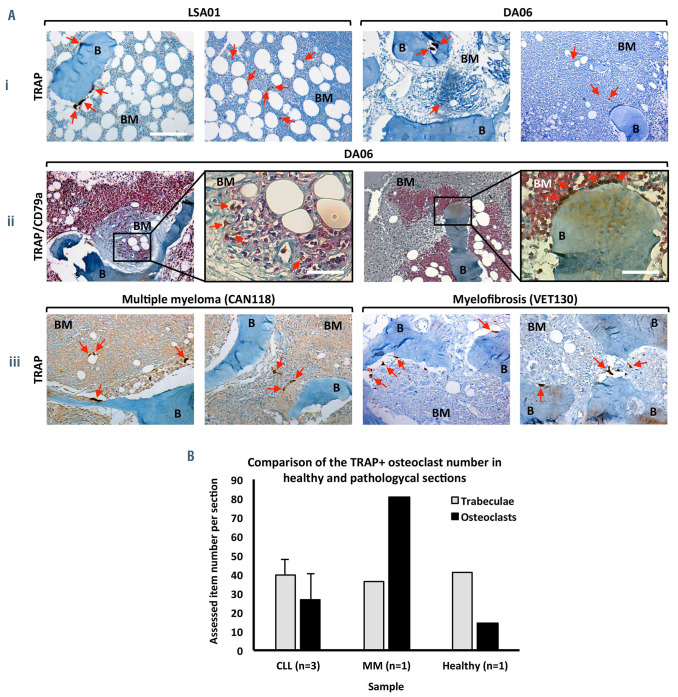

Bone biopsies from CLL patients show the presence of small and large TRAP+ osteoclasts

The presence of osteoclasts was further investigated in bone marrow biopsies from two CLL patients. Classical large cells, immuno-challenged for TRAP positivity, appeared in close contact with bone trabeculae, but much smaller TRAP+ cells were also detectable (Figure 8A); the former, canonical and differentiated osteoclasts, were located on bone surfaces, while the latter, activated TRAP+ monocytes possibly representing immature osteoclasts, were mostly observable within the bone marrow stroma of the biopsies (Figure 8Ai). Moreover, in coimmunostaining experiments, CD79a+ leukemic B cells often appeared in strict vicinity of large TRAP+ cells (Figure 8Aii), further indicating that direct crosstalk between the two cell types may take place in vivo. Additionally, as shown in Figure 8B, the number of osteoclasts found in bone biopsies from three CLL patients appeared higher than in normal controls.

Ibrutinib inhibits increased osteoclastogenesis induced by CLL-conditioned media

B-cell receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib, represent the gold standard therapy for CLL patients. BTK, a member of the TEC kinase family, integrates RANK/RANKL and ITAM pathways along osteoclast formation and activity.27 We determined that ibrutinib significantly inhibited the enhanced generation of large, mature osteoclasts when added contemporarily with CLL-cm to previously activated monocyte cultures (Online Supplementary Figure S9). Ibrutinib treatment may thus counteract survival stimuli provided by the bone microenvironment.

Discussion

In recent years it has become increasingly clear that the bi-directional crosstalk28 between CLL cells and cellular components of the microenvironment plays a relevant role in disease progression. We have demonstrated here that CLL cells affect the differentiation of the two major bone components: osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Indeed CLL cells, through the release of soluble factors, on the one hand inhibit osteoblast differentiation and on the other hand they increase osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. TNFα, IL-6 and IL-11 appear to be involved in the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation: cytokine knockdown, the use of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or blocking binding to their receptors significantly counteracted the inhibition of extracellular matrix deposition when osteo-induced BMSC were cultured in the presence of CLL-cm. Restoration of bone matrix deposition, particularly evident after the addition of the anti- TNFα monoclonal antibody infliximab, suggests a major role of TNFα in the CLL cell-driven impairment of osteoblastogenesis. Indeed TNFα affects osteoblast function and differentiation through the inhibition of the production of extracellular matrix components (i.e., type I collagen), or downmodulating the expression of osteocalcin and alkaline phosphatase.29 TNFα also inhibits the expression of the osteoblast differentiation factor RUNX2.30 Accordingly, neutralization of TNFα in CLL-cm rescued levels of RUNX2 and osteocalcin mRNA in osteoinduced BMSC, paralleling the increase of matrix mineralization. Moreover, a contribution of pSTAT3 and AKT, as downstream molecules involved in bone remodeling signals31 by leukemic cells, may be envisaged through decreased levels of these molecules in BMSC treated with CLL-cm only, as compared with TNFα-neutralized CLL-cm. Interestingly, gene expression profile analysis of available in silico datasets32 highlights that, in human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), different molecules, involved in the regulation of osteoblast differentiation, become modulated after co-culture with CLL cells: a trend to a decrease in RUNX2 and significant decreases in the expression of collagen 1A, BMP-4 and BMP-6, along with increases in DKK-1 and osteopontin have been demonstrated (Online Supplementary Figure S10). These observations further point to interactive crosstalk between CLL cells and MSC possibly leading to niche modifications. Suppression of osteoblast differentiation by leukemic cells has been reported in acute lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma33-35 through alteration of the NOTCH signaling pathway.

Figure 6.

Anti-IL-11 or anti-IL-6R monoclonal antibodesAbs reduce the differentiation of osteoclast precursors. Infliximab (anti-TNFα) inhibits the generation of mature authentic osteoclasts derived in the presence of RANKL. In parallel, higher levels of TNFα were detected in culture media (cm) of monocytes pre-stimulated with RANKL and then with CLL-cm. (A) Neutralization of IL-11 and of IL-6 inhibits the differentiation of TRAP+ tri-nucleated cells derived in the presence of MCSF+CLLcm (M+cm), putatively representing osteoclast precursors, but not of those reaching terminal differentiation, derived in the presence MCSF+RANKL+CLL-cm (MR+cm). Anti-GP130 monoclonal antibodies affected both the number of putative precursors and mature osteoclasts. Large and small indicate the size of the cells as defined in Figure 4. Values were derived from three different experiments and three CLL cases. (B) TNFα, added to cultures of MCSF+RANKL-pre-activated healthy monocytes, stimulated the number of differentiated osteoclasts which also appeared larger than those in control experiments. The addition of CLL-cm from one CLL patient (MAO2) enhanced osteoclast formation, while the neutralizing anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody markedly reduced the enhanced osteoclastogenesis observed. Size bar: 25 μm. (C) Histograms depict the number of large and small osteoclasts derived in the presence of CLL-cm, with or without neutralizing anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody, from five different CLL cases, as assayed in different experiments. The addition of infliximab markedly reduced the number of large, fully differentiated osteoclasts. (D) The amount of TNFα was increased in cultures of monocytes pre-activated with MCSF+RANKL (MR) and then with CLL-cm (MR+cm).

Figure 7.

Fully differentiated osteoclasts, as well as osteoclast precursors, support CLL-cell survival. A limited number of CLL cells further upregulate Ki-67 and reactivate cycling after osteoclast co-culture. (A) Apoptosis of CLL cells was prevented by co-culturing leukemic cells with fully mature osteoclasts for 24 h to 7 days (8 CLL cases at each time-point). (B) Apoptosis of CLL cells was also prevented after their co-culture with osteoclasts derived from healthy monocytes stimulated with MCSF+RANKL, with MCSF+RANKL+CLL-cm or with MCSF+CLL-cm only (putative osteoclast precursors). The percentage of apoptosis was evaluated by DiOC6 staining after 7 days of co-culture. (C) Bright field images show the viability of CLL cells co-cultured with fully differentiated osteoclasts derived in the presence of RANKL (with or without added CLL-cm) or with osteoclast precursors derived in the presence of MCSF+CLL-cm only. (D) Ki-67 was upregulated on CLL cells after their co-culture with mature osteoclasts (4 CLL cases examined). (E) Ki-67 appeared brightly expressed on a limited number of cells. Ki-67+ leukemic cells progressively increased from 72 h to 7 days (1%-15%). (F) A small population of CLL cells was stimulated to enter into S and G2M phases after their co-culture with osteoclasts. CLL cells were stimulated with CpG as controls (4 cases analyzed), AVG: average.

It is also known that TNFα stimulates bone resorption. 36,37 In our model TNFα, acting in synergism with RANKL, increased differentiation of fully multinucleated osteoclasts and infliximab significantly blocked the enhancement in formation of fully mature osteoclasts treated with CLL-cm. This finding suggests that TNFα, released by leukemic cells, stimulates osteoclastogenesis. As previously reported, malignant CLL cells release TNFα,38 and the levels of plasma TNFα, higher in CLL patients than in healthy controls, correlate with disease stage, CD38 expression and chromosomal abnormalities (17p and 11q deletion).39 Interestingly, TNFα levels, significantly higher in sera from patients with advanced disease than in patients with stable disease (Binet C vs. Binet A; 36 cases studied), were directly proportional with the degree of appendicular bone erosion.2 Among CLL patients enrolled in our osteoclastogenesis studies, we further determined a direct correlation between TNFα serum levels and the unmutated IGVH status of the assessed patients (serum cut-off level: 9.0 pg/mL; χ2 test, P=0.0046). We also found that the same unmutated IGVH status of the CLL-cell donors correlated with an increased number of trinucleated TRAP+ cells when pre-activated monocytes were cultured with their CLL-derived conditioned media (χ2 test, P=0.0147) (Online Supplementary Figure S11).

Figure 8.

Typical TRAP+ large osteoclasts and also smaller TRAP+ cells are present in bone biopsies from CLL patients. (Ai) Large TRAP+ cells (brown; red arrows) were observed on trabeculae rims ‘B’ while smaller TRAP+ cells were detectable in the marrow stroma ‘BM’. Representative images from two CLL patients (LSA01, DA06) are shown. (Aii) TRAP and CD79a co-immunostaining revealed that TRAP+ osteoclasts (brown) are often proximal to CD79a+ leukemic B cells (pink), as shown in the enlargements. (Aiii) Positive controls for TRAP immunostaining: two patients with multiple myeloma and myelofibrosis. The bar represents 125 μm except in the inserts in which they represent 32 μm. (B) Number of TRAP+ osteoclasts, related to the number of bone trabeculae, as observed in bone biopsies sections from three patients with CLL (LSA01, DA06, BS13), one patient with multiple myeloma and one normal control. Among CLL patients, LSA01 and DA06 had unmutated IGVH and were in Binet stage B and C, respectively, while BS13 was in Binet stage C.

TNFα plays a key role in many inflammatory diseases characterized by bone damage and enhanced osteoclast differentiation (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis).40-42 It has been recently demonstrated that TNFα-promoted osteoclastogenesis is exerted solely in the contemporary presence of RANKL,43 as we also showed. Other cytokines released by leukemic cells, such as IL-6 and IL-11, may however contribute to monocyte differentiation and participate in the redundancy of osteoclastogenesis control. In the absence of RANKL prestimulation, neutralizing anti-IL-11 or anti-IL-6R and anti- GP130 monoclonal antibodies reduced the number of small tri-nucleated TRAP+ cells derived from monocytes cultured with MCSF and CLL-cm only. Hence cytokines present in CLL-cm (i.e., IL-6, IL-11) might prompt monocytes toward an early step of osteoclast differentiation, thus stimulating the expansion of precursor cells: low levels of soluble RANKL may further limit their ability to complete osteoclast differentiation. Observations by McCoy et al.44 appear to be in accordance with this suggestion: although IL-11 derived from breast tumor promoted the development of osteoclast progenitors, the enhancement of fully differentiated osteoclasts appeared to be dependent on subsequent RANKL addition. When provided alone, MCP1 also increased differentiation of monocytes in multinuclear TRAP+ cells without bone resorption activity. Nonetheless the same cells, after RANKL exposure, differentiated into authentic boneresorbing osteoclasts.45 The complex process of osteoclast differentiation involves the regulated expression of various molecules and their linked transduced signal. The interaction between RANKL, residing on osteoblasts, and RANK, expressed on activated monocytes, results in the recruitment of TNF receptor-associated factor-6 (TRAF-6) which in turn activates NF-κB, JNK, ERK, p38, Akt and NFATc1. In particular NFATc1 is considered the master transcription factor that regulates the expression of molecules such as MMP9, OSCAR, DC-stamp, TRAP and cathepsin K, which altogether define the functional osteoclast phenotype.46 We have shown here higher cathepsin K, MMP9, and NFATc1 mRNA expression in RANKL-activated monocytes cultured with CLL-cm than in controls: this finding may parallel the observed increment in the number of fully differentiated osteoclasts found after the addition of CLL-cm. The reduced levels of cathepsin K mRNA observed in monocytes stimulated with CLL-cm only may further suggest a blockade of their differentiation stage.

A high incidence of bone alterations, in various B-cell malignancies including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been previously reported.47 In bone biopsies from patients with such malignancies, a consistent number of TRAP+ monocytes are located near bone trabeculae and are smaller than the osteoclasts found in multiple myeloma. These small cells induce areas of micro-resorption and are found in the proximity of malignant lymphoid cells. Further evidence of the presence of minute, single bays facing small TRAP+ osteoclasts in eroded bone surfaces of patients with B-cell malignancies was subsequently provided.48 These findings suggest that, in B-cell malignancies, higher numbers of active small osteoclasts are needed to cause rates of resorption similar to those observed in patients with multiple myeloma. Interestingly, evaluation of the frequency distribution profile of osteoclast dimensions in bone sections from patients with B-cell malignancies has demonstrated the existence of a bimodal distribution of TRAP+ osteoclasts, characterized by two different average diameters, peaking at 10-15 μm and at 20-25 μm. In contrast, in multiple myeloma the distribution appeared homogenous and unimodal, with a single peak around 20-25 μm.49 Data obtained from our in vitro model of osteoclast generation, under different conditions, resemble these in vivo findings: consistent numbers of small tri-nucleated TRAP+ cells and only limited numbers of large mature osteoclasts could be derived when MCSF-activated monocytes were cultured with CLL-cm alone. In contrast, pre-stimulation with RANKL allowed the differentiation of monocytes into authentic, fully mature osteoclasts. Bone structure alterations might therefore be relatively common in CLL patients, but usually surmised, because extensive bone lesions do not occur frequently. Reasonably, in CLL patients, the multi-cytokine panel produced by leukemic cells stimulates the generation of osteoclast progenitors which, however, usually fail to mature completely. Hence the impaired bone homeostasis in CLL differs from that previously determined in multiple myeloma. In the former malignant plasma cells release RANKL, while in the latter CLL cells are incapable of shedding it.17 Exceptionally, some CLL cases, hypothetically characterized by more advanced disease stage and possibly by the presence of higher levels of RANKL and TNFα, might display osteolysis. The presence of neoplastic B cells, often close to osteoclasts, also appears of interest:50 small areas of bone micro-resorption could represent small niches of recovery and protection for neoplastic B cells. We confirmed that in bone biopsies from CLL patients, leukemic cells are detectable in strict vicinity of osteoclasts, thus suggesting their mutual interactions. The proof that fully differentiated osteoclasts, or their precursors, protect leukemic B cells from apoptosis, upregulate Ki-67 and stimulate their proliferation sustains the idea of an active interplay between these two populations of cells. Moreover, the disruption of CLL-cell-mediated osteoclast support by the BTK inhibitor, ibrutinib, is a novel finding. Finally, the observations in the present study highlight new relationships between neoplastic CLL cells and normal bone counterparts, evidence a mutually active alteration of the local pathological bone marrow microenvironment and suggest a widened perspective for novel therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. S. Zupo for providing supplementary CLL samples.

Funding Statement

Funding: Funding was provided by Ricerca Corrente line “Host-Cancer Interaction” (to CM, FF); CNR flagship program Interomics 2015 (to CM); Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC); 5 x mille n.9980 (to MF, AN) and by AIRC I.G. n.14326 (to MF) and n.15426 (to FF) and 16722, 10136 (to AN); and Compagnia San Paolo, Turin, Italy project 2017 0526 (to GC), and Italian Ministry of Health 5x1000 funds 2014 (to GC) and funds 2015 (to FF).

References

- 1.Fiz F, Marini C, Piva R, et al. Adult advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia: computational analysis of whole-body CT documents a bone structure alteration. Radiology. 2014;271(3):805-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marini C, Bruno S, Fiz F, et al. Functional activation of osteoclast commitment in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a possible role for RANK/RANKL pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borge M, Delpino MV, Podaza E, et al. Soluble RANKL production by leukemic cells in a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with bone destruction. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(10):2468-2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hua J, Ide S, Ohara S, et al. Hypercalcemia and osteolytic bone lesions as the major symptoms in a chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma patient: a rare case. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2018;58(4):171-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz H, Sagun S, Griswold D, Alsharedi M.Solitary lytic bone metastasis: a rare presentation of small lymphocytic leukemia. Case Rep Hematol. 2018;2018:6154709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMillan P, Mundy G, Mayer P.Hypercalcaemia and osteolytic bone lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br Med J. 1980;281(6248):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soni P, Aggarwal N, Rai A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a rare cause of pathological fracture of the femur. J Invest Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017;5(4):1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olszewski AJ, Gutman R, Eaton CB. Increased risk of axial fractures in patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a population-based analysis. Haematologica. 2016;101(12):e488-e491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burger JA, Gandhi V.The lymphatic tissue microenvironments in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: in vitro models and the significance of CD40-CD154 interactions. Blood. 2009;114(12):2560-2561; author reply 2561-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burger JA, Ghia P, Rosenwald A, Caligaris-Cappio F. The microenvironment in mature B-cell malignancies: a target for new treatment strategies. Blood. 2009;114(16):3367-3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannoni P, Pietra G, Travaini G, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia nurse-like cells express the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET) and indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase and display features of immunosuppressive type 2 skewed macrophages. Haematologica. 2014;99(6):2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannoni P, Scaglione S, Quarto R, et al. An interaction between hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor (c-MET) prolongs the survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemic cells through STAT3 phosphorylation: a potential role of mesenchymal cells in the disease. Haematologica. 2011;96(7):1015-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagneaux L, Delforge A, Bron D, De Bruyn C, Stryckmans P.Chronic lymphocytic leukemic B cells but not normal B cells are rescued from apoptosis by contact with normal bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 1998;91(7):2387-2396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bataille R, Chappard D, Marcelli C, et al. Mechanisms of bone destruction in multiple myeloma: the importance of an unbalanced process in determining the severity of lytic bone disease. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(12):1909-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roodman GD. Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valentin-Opran A, Charhon SA, Meunier PJ, Edouard CM, Arlot ME. Quantitative histology of myeloma-induced bone changes. Br J Haematol. 1982;52(4):601-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmiedel BJ, Scheible CA, Nuebling T, et al. RANKL expression, function, and therapeutic targeting in multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):683-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Secchiero P, Corallini F, Barbarotto E, et al. Role of the RANKL/RANK system in the induction of interleukin-8 (IL-8) in B chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207(1):158-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Totero D, Meazza R, Zupo S, et al. Interleukin-21 receptor (IL-21R) is up-regulated by CD40 triggering and mediates proapoptotic signals in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2006;107(9):3708-3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruno S, Ghiotto F, Tenca C, et al. N-(4- hydroxyphenyl)retinamide promotes apoptosis of resting and proliferating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and potentiates fludarabine and ABT-737 cytotoxicity. Leukemia. 2012;26(10):2260-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morabito F, Mosca L, Cutrona G, et al. Clinical monoclonal B lymphocytosis versus Rai 0 chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a comparison of cellular, cytogenetic, molecular, and clinical features. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(21):5890-5900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes FJ, Turner W, Belibasakis G, Martuscelli G.Effects of growth factors and cytokines on osteoblast differentiation. Periodontol 2000. 2006;41:48-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manolagas SC. The role of IL-6 type cytokines and their receptors in bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:194-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims NA. Cell-specific paracrine actions of IL-6 family cytokines from bone, marrow and muscle that control bone formation and resorption. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;79: 14-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang HQ, Jia L, Li YT, Farren T, Agrawal SG, Liu FT. Increased autocrine interleukin-6 production is significantly associated with worse clinical outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(8):13994-14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burger JA, Tsukada N, Burger M, Zvaifler NJ, Dell'Aquila M, Kipps TJ. Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 2000;96(8):2655-2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinohara M, Koga T, Okamoto K, et al. Tyrosine kinases Btk and Tec regulate osteoclast differentiation by linking RANK and ITAM signals. Cell. 2008;132(5):794-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding W, Nowakowski GS, Knox TR, et al. Bi-directional activation between mesenchymal stem cells and CLL B-cells: implication for CLL disease progression. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(4):471-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gowen M, MacDonald BR, Russell RG. Actions of recombinant human gammainterferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha on the proliferation and osteoblastic characteristics of human trabecular bone cells in vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(12):1500-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert L, He X, Farmer P, et al. Expression of the osteoblast differentiation factor RUNX2 (Cbfa1/AML3/Pebp2alpha A) is inhibited by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(4):2695-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H, Newnum AB, Martin JR, et al. Osteoblast/osteocyte-specific inactivation of Stat3 decreases load-driven bone formation and accumulates reactive oxygen species. Bone. 2011;49(3):404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulze-Edinghausen L, Durr C, Ozturk S, et al. Dissecting the prognostic significance and functional role of progranulin in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancers. 2019;11(6): 822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delgado-Calle J, Anderson J, Cregor MD, et al. Bidirectional notch signaling and osteocyte- derived factors in the bone marrow microenvironment promote tumor cell proliferation and bone destruction in multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2016;76(5):1089-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar A, Anand T, Bhattacharyya J, Sharma A, Jaganathan BG. K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells modify osteogenic differentiation and gene expression of bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Commun Signal. 2018;12(2):441-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangolini M, Ringshausen I.Bone marrow stromal cells drive key hallmarks of B cell malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertolini DR, Nedwin GE, Bringman TS, Smith DD, Mundy GR. Stimulation of bone resorption and inhibition of bone formation in vitro by human tumour necrosis factors. Nature. 1986;319(6053):516-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nanes MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene. 2003;321:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foa R, Massaia M, Cardona S, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: a possible regulatory role of TNF in the progression of the disease. Blood. 1990;76(2):393-400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrajoli A, Keating MJ, Manshouri T, et al. The clinical significance of tumor necrosis factor-alpha plasma level in patients having chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100(4):1215-1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colucci S, Brunetti G, Cantatore FP, et al. Lymphocytes and synovial fluid fibroblasts support osteoclastogenesis through RANKL, TNFalpha, and IL-7 in an in vitro model derived from human psoriatic arthritis. J Pathol. 2007;212(1):47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimitroulas T, Nikas SN, Trontzas P, Kitas GD. Biologic therapies and systemic bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(10):958-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fantuzzi F, Del Giglio M, Gisondi P, Girolomoni G.Targeting tumor necrosis factor alpha in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12(9):1085-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo G, Li F, Li X, Wang ZG, Zhang B.TNFalpha and RANKL promote osteoclastogenesis by upregulating RANK via the NFkappaB pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(5):6605-6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCoy EM, Hong H, Pruitt HC, Feng X.IL- 11 produced by breast cancer cells augments osteoclastogenesis by sustaining the pool of osteoclast progenitor cells. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim MS, Day CJ, Selinger CI, Magno CL, Stephens SR, Morrison NA. MCP-1-induced human osteoclast-like cells are tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, NFATc1, and calcitonin receptor-positive but require receptor activator of NFkappaB ligand for bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(2):1274-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amarasekara DS, Yun H, Kim S, Lee N, Kim H, Rho J.Regulation of osteoclast differentiation by cytokine networks. Immune Netw. 2018;18(1):e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcelli C, Chappard D, Rossi JF, et al. Histologic evidence of an abnormal bone remodeling in B-cell malignancies other than multiple myeloma. Cancer. 1988;62(6):1163-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chappard D, Rossi JF, Bataillle R, Alexandre C.Osteoclast cytomorphometry and scanning electron microscopy of bone eroded surfaces during leukemic disorders. Scanning Microsc. 1990;4(2):323-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chappard D, Rossi JF, Bataille R, Alexandre C.Osteoclast cytomorphometry demonstrates an abnormal population in B cell malignancies but not in multiple myeloma. Calcif Tissue Int. 1991;48(1):13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi JF, Chappard D, Marcelli C, et al. Micro-osteoclast resorption as a characteristic feature of B-cell malignancies other than multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1990;76(4):469-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.