Abstract

Background:

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence with high-definition, three-dimensional imaging systems is emerging as the latest strategy to reduce trauma and improve surgical outcomes during oncosurgery.

Materials and Methods:

This is a prospective study involving 100 patients with carcinoma endometrium who underwent robotic-assisted Type 1 pan-hysterectomy, with ICG-directed sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy from November 2017 to December 2019. The aim was to assess the feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of SLN algorithm and to evaluate the location and distribution of SLN in pelvic, para-aortic and unusual areas and the role of frozen section.

Results:

The overall SLN detection rate was 98%. Bilateral detection was possible in 92% of the cases. Right side was detected in 98% of the cases and left side was visualised in 92% of the cases. Complete node dissection was done where SLN mapping failed. The most common location for SLN in our series was obturator on the right hemipelvis and internal iliac on the left hemipelvis. SLN in the para-aortic area was detected in 14% of cases. In six cases, SLN was found in atypical locations, that is pre-sacral area. Eight patients had SLN positivity for metastasis and underwent complete retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Comparison of final histopathological report with frozen section reports showed no false negatives.

Conclusions:

SLN mapping holds a great promise as a modern staging strategy for endometrial cancer. In our experience, cervical injection was an optimal method of mapping the pelvis. ICG showed a high overall detection rate, and bilateral mapping appears to be a feasible alternative to the more traditional methods of SLN mapping in patients with endometrial cancer. The ICG fluorescence imaging system is simple and safe and may become a standard in oncosurgery in view of its staging and anatomical imaging capabilities. This approach can reduce the morbidity, operative times and costs associated with complete lymphadenectomy while maintaining prognostic and predictive information.

Keywords: Carcinoma endometrium, indocyanine green fluorescence, para-aortic lymphadenectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, robotic surgery, sentinel node mapping

INTRODUCTION

Modern surgical strategies aim to improve surgical outcomes without compromising on oncological principles. Technological advancements have revolutionised surgery, resulting in reduced surgical trauma while improving outcomes without losing out on important prognostic and staging information. Robotic surgery was introduced at our centre in 2011 and has now become the preferred modality for endometrial cancer surgery. Our initial experience with the details of the learning curve has been published earlier.[1]

The standard treatment modalities for early endometrial cancer include extrafascial hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), peritoneal cytology and regional lymph node (LN) assessment. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy has been included in the surgical staging criteria for endometrial cancer since 1988.[2] As per the current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging, positive cytology has to be reported separately without changing the stage.

LN status has far-reaching implications in endometrial cancer. It is the most important predictor of survival, which provides prognostic assessment and also guides in adjuvant treatment.[3] Surgical staging of clinically uterine-confined endometrial cancers with comprehensive pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic lymphadenectomy (RPLND) has traditionally been performed in order to accurately stage and triage patients that might benefit from adjuvant therapies. However, systematic RPLND procedures have been associated with increased morbidity including lymphocoeles, lymph oedema and neuralgia.[4] Although many studies have failed to show the survival benefit of lymphadenectomy, the adjuvant treatment and prognosis depends on the nodal status, hence omitting it is not an option. RPLND may be an overtreatment in low-risk cases, causing unnecessary surgical morbidity, but omitting it may result in undertreatment in high-risk patients as it may miss patients with nodal metastasis, who could benefit from adjuvant therapy.[5,6]

Whether a lymphadenectomy is merely diagnostic or has a therapeutic value remains unclear, but it is very important to find a balance between under- or over-treatment.[7,8,9] Therefore, there is an increasing need for reducing the surgical morbidity of lymphatic assessment without compromising its prognostic and predictive values. Sentinel LN (SLN) mapping has been recognised as a viable option. Various agents have been evaluated for SLN mapping. Indocyanine green (ICG) is a vital dye with the distinctive feature of being fluorescent when used with near-infrared (NIR) imaging.[10,11,12] This simple, radiation-free, innovative technique is used in oncology as an intraoperative tool for lymphatic mapping, vascularity assessment and tissue delineation.[13,14,15,16,17] ICG and NIR fluorescence mapping provides detailed anatomical information with functional imaging in real time and has been used for mapping endometrial cancers.[18,19,20]

In this prospective study, the aim was to evaluate the feasibility and accuracy of sentinel node mapping in women with carcinoma endometrium using Da Vinci firefly robotic technology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study involving patients with carcinoma endometrium who underwent robotic-assisted extrafascial hysterectomy with ICG-directed SLN biopsy (SLNB) and staging.

The aims of the study were to:

Assess the feasibility of sentinel node mapping in women with carcinoma endometrium using Da Vinci firefly robotic technology

Assess the distribution of sentinel nodes and their positivity rate

Assess the accuracy of frozen section.

The study was conducted at Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Centre, Bengaluru, from November 2017 to December 2019. The study was approved by the institutional review board. The robotic surgery data for the study was compiled from the Vattikuti Collective Quality Initiative (VCQI). Patients with biopsy-proven carcinoma endometrium with clinical FIGO Stage I–II disease who were suitable for surgery were included in the study. The extent of myometrial and/or cervical invasion was determined by expert vaginal ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging. Patients with allergy to iodine were not included in the study. All the patients included in the study were explained regarding SLNB and lymphadenectomy including a small possibility of false-negative results with SLNB. Patients gave consent after understanding the benefits and limitations of the procedure. The procedure of sentinel node mapping and biopsy with frozen section analysis and the need for complete pelvic and para-aortic node dissection if the frozen section report was positive for metastasis was explained to the patients. A written informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled women. All the women underwent robotic extrafascial hysterectomy, BSO, ICG SLNB and peritoneal cytology with the Da Vinci X Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All the surgical procedures were performed by the same surgical team.

Procedure

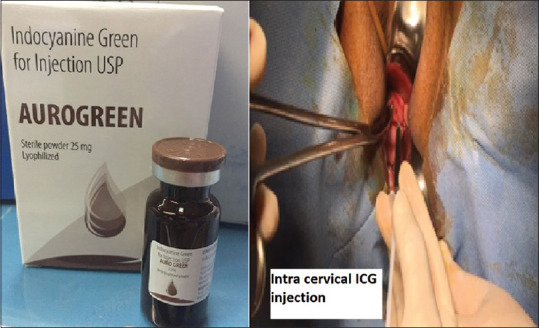

The vial containing ICG dye (Aurogreen, Aurolab, No 1, Sivagangai Main Road, Veerapanjan, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India) was diluted with 10ml of sterile water and a dose of 2.5-mg/ml was aspirated from the vial for cervical injection. Half the volume was injected submucosally, while the remaining half was injected into the cervical stroma. Deep injections are known to be drained by para-aortic chain of lymphatics which guides to find para-aortic sentinel nodes. V-care (Vaginal-Cervical Ahluwalia’s Retractor Elevator, CONMED, Utica, New York, USA) uterine manipulator with endocervical balloon was used for manipulation. The robot was docked with centro-side docking [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

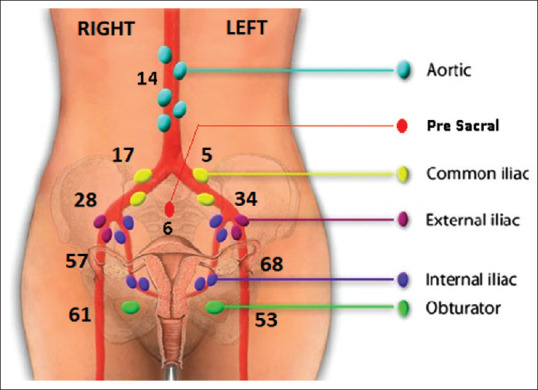

Sentinel lymph node distribution

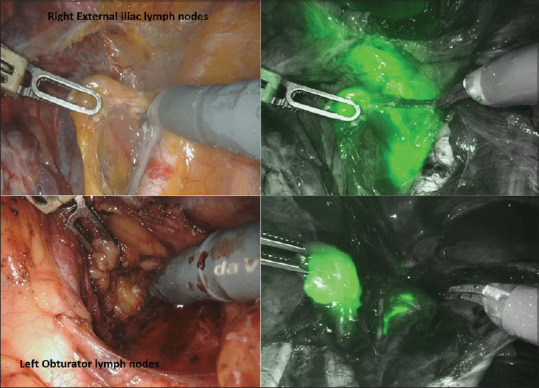

Following creation of pneumoperitoneum, the peritoneal cavity was inspected and washings were taken for cytology. Literature search revealed that time for the ICG uptake by the SLN has not been mentioned in any studies. In our series, time taken for SLN illumination following the intracervical ICG injection was about 5 to 7 minutes (during the ports application and docking). We believe that the average time for dye uptake for SLN is 5–7 min. The retroperitoneal SLN detection and distribution were mapped using the Da Vinci Firefly technique (LED illuminator and high-definition, three-dimensional camera system). The SLN protocol was based on the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC) algorithm, which allows for a systematic approach to incorporating lymphatic mapping in the surgical staging of endometrial cancer.[21] The lymphatic pathways were kept intact by opening the avascular para-vesical and para-rectal planes, and ICG glow was identified. To minimise disturbance from leaking dye, removal of SLNs was first performed along the lower para-cervical pathways followed by caudal pathways. ICG-positive LN in the external, internal, common iliac, obturator and other pelvic areas was dissected and excised. The para-aortic and para-caval areas were inspected for fluorescent-illuminating nodes. All nodes were labelled for exact location and laterality and sent for frozen section analysis. Any suspiciously enlarged or firm LNs were also removed irrespective of the mapping results. Type I radical hysterectomy was done and sent for frozen analysis for assessing the high-risk features, that is grade, type and depth of invasion. In case of failure of SLN mapping (no ICG illuminating nodes), then side-specific pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed. SLN was considered positive if it contained macro-metastasis on frozen section and completion lymphadenectomy was performed on the respective side [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Intraoperative sentinel lymph node identification

After frozen section analysis, all SLN tissues were embedded and ultra-sectioned to a minimum thickness of 3 μm. All adverse events occurring after the injection of ICG were registered, and their relation to the different steps of the surgical procedure was noted. Complications up to 30 days post-operatively were classified according to the Clavien–Dindo classification.[22]

RESULTS

A total of 100 women were enrolled and included in the study. The procedure was successfully completed in all patients without conversion to open laparotomy, and no intraoperative or post-operative complications occurred. None of the patients had allergic reaction to ICG. The median docking time was 4 min (range 2–7 min). The demographic and clinical data are presented in Table 1. The age ranged from as young as 35 to 88 years with a mean age of 60 years. The average body mass index (BMI) was 29.58. All patients were grouped based on ESMO risk stratification model.[23]

Table 1.

Patients’ clinicopathological demographics

| Variable | n=100 cases |

|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 60 (35-88) |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) (range) | 29.58 (23-55) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 79 |

| 1 | 21 |

| FIGO stage | |

| IA | 54 |

| IB | 32 |

| II | 14 |

| Pathology type | |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 90 |

| Non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 10 |

| Serous carcinoma | 2 |

| Clear cell type | 6 |

| De-differentiated | 2 |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 18 |

| 2 | 52 |

| 3 | 30 |

| Uterine risk factors | |

| Low risk | 27 |

| Intermediate risk | 48 |

| High risk | 25 |

BMI: Body mass index, ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FIGO: Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

SLN mapping was successful in 98 out of the 100 patients. In two cases, no sentinel mapping could be performed because there was gross flushing of dye of the lymph nodal and parametrial areas. Hence, SLN mapping was abandoned and bilateral RPLND was done. Out of the 98 patients, bilateral SLN detection was possible in 92 patients. Unilateral SLN detection was not possible in six patients. In these patients, pelvic lymphadenectomy was done on the side where SLN was not detected. The anatomic distribution of SLN is shown in Figure 2. The most common location for SLN was the obturator area on the right side and the internal iliac on the left side. Para-aortic SLN was detected in 14 patients. An unusual location of SLN in our series was the pre-sacral area in six patients [Table 2 and Figure 3].

Table 2.

Sentinel lymph node detection, distribution and metastasis

| Variable | n=100 cases, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SLN detection rate | 98/100 (98) | |

| SLN mapping failure | 2/100 | |

| SLN detected patients - laterality of mapping (n=98) | ||

| Bilateral SLN mapping | 92/98 (93.9) | |

| Unilateral SLN mapping only | 6/98 (6.1) | |

| Median number of SLNs harvested per patient (range) | 4 (1-7) | |

|

| ||

| Location of SLN | Right | Left |

|

| ||

| Pelvic | ||

| Obturator | 61 (62.2) | 53 (54.1) |

| Internal iliac | 57 (58.2) | 68 (69.9) |

| External iliac | 28 (28.6) | 34 (34.7) |

| Common iliac | 17 (17.3) | 5 (5.1) |

| Para aortic | 14 (14.3) | |

| Unusual site (pre-sacral) | 6 (6.1) | |

| Number of patients with SLN metastasis (n+) | 8/98 | |

SLNs: Sentinel lymph nodes

Figure 3.

Intracervical indocyanine green injection (Aurogreen)

The median SLN count of pelvic sentinel nodes was 4 (range 2–7) and that of para-aortic was 2 (range 1–3). Eight patients had metastatic deposits, with the SLN being the only positive node in two patients. Two patients had bilateral node positivity. As per the institutional protocol, complete pelvic and para-aortic node dissection was performed in all the eight cases, with nodes being positive on frozen section. Isolated para-aortic LN metastasis was not observed in any of the cases. There was no discrepancy between the frozen section and final pathology. The diagnostic accuracy of frozen section was 100%. No micro-metastasis was found by ultra-staging. No major post-operative complications occurred in the 30-day post-operative period.

All the patients with lymph nodal metastatic disease had high-risk or intermediate-risk disease. Out of the eight patients, three were in the intermediate-risk group and five were in the high-risk group. The risk factors associated in nodal metastatic patients are summarised in Table 3.[23]

Table 3.

Risk factor association in node positivity

| Risk parameters | n=8 |

|---|---|

| Tumour size (cm) | |

| <2 | 1 |

| >2 | 7 |

| Myometrial invasion (%) | |

| <50 | 2 |

| >50 | 6 |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 |

| LVI | |

| Present | 3 |

| Absent | 5 |

| Pathological type | |

| Endometrioid | 6 |

| Non-endometrioid | 2 |

LVI: Lympho vascular invasion

DISCUSSION

Over the last two decades, minimally invasive surgery for endometrial cancer has been gaining popularity and now, it is accepted as a standard of care.[24] The integration of SLN mapping techniques has enhanced the utility of this surgical modality.

SLN mapping has been proposed as a method to potentially reduce the morbidity of surgical staging while maintaining prognostic and predictive information. A recent comprehensive review on SLN mapping showed that SLN mapping with ICG gives higher overall and bilateral detection rates compared with the standard radiocolloid and blue dye technique.[25,26] Another meta-analysis revealed that the SLN detection rates and the bilateral SLN detection rates with ICG appear to be comparable with or better than those with blue dye only or with radiocolloid.[9] Other dyes and radiotracers have also demonstrated high overall SLN detection rates but did not significantly improve bilateral mapping rates, hence ICG is considered the preferred mapping agent for SLN mapping of endometrial cancer. SLN mapping by MSKCC algorithm has a high rate of SLN detection, a high sensitivity for detection of metastasis and a low false-negative rate.[27,28,29] By adopting MSKCC algorithm, Barlin et al. were able to show a significant reduction in false-negative rates which dropped from 15% to 2.5%, while the sensitivity was 98.1% and negative predictive value (NPV) was 99.8%.[30]

A recent multicentric, prospective trial demonstrated high degree of diagnostic accuracy of SLNB in detecting endometrial cancer metastases. SLN detection rates ranged from 62% to 96% for overall and from 19% to 88% for bilateral detection rate in endometrial cancer.[31]

At our centre, by adopting the recommended surgical algorithm, the results of SLN procedure were comparable to that of international reports. Our SLN detection rate and bilateral detection rate of 98% and 93.9% are comparable to that of other studies. In 2% of patients, there was diffuse flushing of the dye in the parametrium and SLN detection was not possible, hence comprehensive nodal clearance of the bilateral pelvic nodes was done. The results of the FIRES trial showed that the sensitivity of SLN mapping with cervical ICG injection for finding LN positivity was 97.2% with an NPV of 99.6% and recommended that SLN could replace lymphadenectomy in the staging of endometrial cancer.[32] Even in high-risk cancer patients, the SHREC trial demonstrated a sensitivity to identify pelvic node metastasis of 100% with 95% bilateral mapping rate and 98% sensitivity.[33]

The multi-institutional SENTI-ENDO study and other studies found no difference in long-term recurrence-free survival between sentinel node negative for metastasis and those with positive sentinel node metastasis.[34,35] The detection rate of the sentinel node was 93.9% on both sides and 98% on at least one side. The detection rate was 92% when a side was taken as a unit of analysis (6% patients only unilateral detection was possible) and 98% when patient was taken as a unit. No LN recurrence has been observed during follow-up.

The location of the sentinel nodes of our series was compared with the FIRES trial; The findings were as follows external iliac (31%) compared to the FIRES Trial (38%), obturator 56% versus 25%, para-aortic (14% vs. 15%), common iliac (11% vs. 8%), internal iliac (62.5% vs. 10%) and pre-sacral (6% vs. 3%). According to our institutional protocol, the SLN was submitted for frozen section analysis followed by regular pathological analysis and ultra-staging. Enhanced pathologic analysis with serial sectioning and ultra-staging increases the detection of metastasis compared to that of routine haematoxylin and eosin examination.[36,37,38]

Eight patients had nodal metastases. Pelvic and para-aortic node dissection was performed in all these eight cases as per the institutional protocol. We did not have any cases of isolated para-aortic-positive cases. The risk factors associated with positive nodes were assessed with risk stratification according to the ESMO guidelines. Positive nodes were seen in two high-risk patients and in one intermediate-risk patient. Node positivity was associated with positive lymphovascular invasion. None of the Grade 1 lesions had metastatic-positive nodes. Among metastatic nodes, 6% were in Grade 3 lesions, 2% in Grade 2 lesions and 2% in serous cancer. All the positive nodes were found in cases having lesions with depth of invasion >50% of the myometrium.

While early results for SLN mapping in endometrial cancer are promising, other research has raised concerns about the adequacy of nodal detection for para-aortic nodes.[39,40] BMI may limit the lymphatic spread of tracers used in SLN mapping, which could limit its efficacy in endometrial cancer.[41]

In our study, because completion pelvic dissection was not done for cases with negative nodes on frozen section, the sensitivity and NPV could not be calculated. Moreover, our data are not mature enough to ascertain the recurrence pattern and survival in SLN-negative group. Large multicentric studies comparing SLN with complete RPLND to predict the sensitivity and accuracy of technique are needed with a longitudinal follow-up to establish the complications or recurrence pattern.

This study has brought out two important questions. The first is that in low-risk cases, if bilateral mapping is not seen, then should complete pelvic lymphadenectomy be done? The other question is in case SLN nodes are positive on frozen section, should complete lymphadenectomy be done? Our data showed no LN metastases in low-risk cases. To establish the role of complete lymphadenectomy in SLN-positive cases, randomised trials comparing SLN alone versus lymphadenectomy would be needed. However, if node positivity is only considered a criterion for staging and defining adjuvant therapy, then SLN status alone could suffice.

The current guidelines do not yet recommend SLN mapping as the standard of care in the staging of this malignancy, although national societies and organisations that define treatment standards are increasingly recognising the utility of this staging approach. SLN procedure has been included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for early-stage endometrial at highly specialised centres, experienced in SLN mapping.[42] The Society of Gynaecologic Oncology has also recommended that SLN mapping can be performed instead of routine pelvic Lymphnode dissection for patients with early-stage endometrial cancers.[38]

CONCLUSIONS

ICG-based NIR fluorescence SLN mapping in endometrial cancer is a promising staging strategy. It is accurate with high overall and bilateral detection rates and helps in tailoring adjuvant treatment. Surgeons’ expertise in SLN mapping field allows obtaining excellent detection rates and should be done in institutions with expertise in this procedure. Intracervical injection of ICG is an optimal method of mapping the LNs in the pelvis. SLN in the para-aortic area and at atypical locations can also be detected, which would have otherwise been missed.

The ICG fluorescence imaging system is a simple, safe, practical and easily reproducible technique. This approach can reduce the morbidity, operative times and costs associated with complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy without compromising prognostic and predictive information.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Vattikuti Foundation for their support and providing the Vattikuti Collective Quality Initiative (VCQI) global robotic surgery database.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacob SS, Somashekhar SP, Jaka R, Ashwin KR, Kumar R. Robotic-Assisted Pelvic and High Para-aortic Lymphadenectomy (RPLND) for Endometrial Cancer and Learning Curve. Indian J Gynecol Oncolog. 2016;14:32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-016-0058-0. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd JH. Revised FIGO staging for gynaecological cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:889–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb03341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindqvist E, Wedin M, Fredrikson M, Kjølhede P. Lymphedema after treatment for endometrial cancer-A review of prevalence and risk factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;211:112–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma C, Deutsch I, Lewin SN, Burke WM, Qiao Y, Sun X, et al. Lymphadenectomy influences the utilization of adjuvant radiation treatment for endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:562.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogani G, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, Ghezzi F, Rossetti D, Mariani A. Role of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer: Current evidence. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:301–11. doi: 10.1111/jog.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto Lissoni A, Signorelli M, Scambia G, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs.no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: Randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1707–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ASTEC study group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): A randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creasman WT, Mutch DE, Herzog TJ. ASTEC lymphadenectomy and radiation therapy studies: Are conclusions valid? Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:293–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka K, Mori R, Kawamura A, Nakashizuka H, Wakatsuki Y, Yuzawa M. Comparison of OCT angiography and indocyanine green angiographic findings with subtypes of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:51–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senders JT, Muskens IS, Schnoor R, Karhade AV, Cote DJ, Smith TR, et al. Agents for fluorescence-guided glioma surgery: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical results. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:151–67. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-3028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler HO, Cranston WI, Meltzer JI. Hepatic uptake and biliary excretion of indocyanine green in the dog. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1958;99:11–4. doi: 10.3181/00379727-99-24229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugie T, Ikeda T, Kawaguchi A. Sentinel lymph node biopsy using indocyanine green fluorescence in early-stage breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:11–7. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-1064-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buda A, Papadia A, Zapardiel I, Vizza E, Ghezzi F, De Ponti E, et al. From conventional radiotracer Tc-99(m) with blue dye to indocyanine green fluorescence: A comparison of methods towards optimization of sentinel lymph node mapping in early stage cervical cancer for a laparoscopic approach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2959–65. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin H, Ding Z, Kota VG, Zhang X, Zhou J. Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46601–10. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnier P, Niddam J, Bosc R, Hersant B, Meningaud JP. Indocyanine green applications in plastic surgery: A review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:814–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handgraaf HJ, Boogerd LS, Höppener DJ. Long-term follow-up after near-infrared fluorescence-guided resection of colorectal liver metastases: A retrospective multicenter analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geppert B, Lönnerfors C, Bollino M, Persson J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer-Feasibility, safety and lymphatic complications. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:491–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Rustum NR, Khoury-Collado F, Pandit-Taskar N, Soslow RA, Dao F, Sonoda Y, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping for grade 1 endometrial cancer: Is it the answer to the surgical staging dilemma? Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinelli F, Ditto A, Bogani G, Signorelli M, Chiappa V, Lorusso D, et al. Laparoscopic sentinel node mapping in endometrial cancer after hysteroscopic injection of indocyanine green. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson J, Geppert B, Lönnerfors C, Bollino M, Måsbäck A. Description of a reproducible anatomically based surgical algorithm for detection of pelvic sentinel lymph nodes in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendifallah S, Canlorbe G, Raimond E, Hudry D, Coutant C, Graesslin O, et al. A clue towards improving the European Society of Medical Oncology risk group classification in apparent early stage endometrial cancer? Impact of lymphovascular space invasion. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2640–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabinovich A. Minimally invasive surgery for endometrial cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:302–7. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abu-Rustum NR. Sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer: A modern approach to surgical staging. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:288–97. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson AG, Beavis A, Soslow RA, Zhou Q, Abu-Rustum NR, Gardner GJ, et al. A Comparison of the detection of sentinel lymph nodes using indocyanine green and near-infrared fluorescence imaging versus blue dye during robotic surgery in uterine cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:743–7. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidal F, Leguevaque P, Motton S, Delotte J, Ferron G, Querleu D, et al. Evaluation of the sentinel lymph node algorithm with blue dye labeling for early-stage endometrial cancer in a multicentric setting. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1237–43. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829b1b98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrisman J, Secord AA, Berchuck A, Lee PS, Di Santo N, Lopez-Acevedo M, et al. Performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in high-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;17:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagen B, Valla M, Aune G, Ravlo M, Abusland AB, Araya E, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging of lymph nodes during robotic-assisted laparoscopic operation for endometrial cancer. A prospective validation study using a sentinel lymph node surgical algorithm. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:479–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlin JN, Khoury-Collado F, Kim CH, Leitao MM, Jr, Chi DS, Sonoda Y, et al. The importance of applying a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm in endometrial cancer staging: Beyond removal of blue nodes. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bedynska M, Szewczyk G, Klepacka T, Sachadel K, Maciejewski T, Szukiewicz D, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping using indocyanine green in patients with uterine and cervical neoplasms: Restrictions of the method. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:1373–84. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi EC, Kowalski LD, Scalici J, Cantrell L, Schuler K, Hanna RK, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): A multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:384–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persson J, Salehi S, Bollino M, Lonnerfors C, Falconer H, Geppert B. Pelvic sentinel lymph node detection in high-risk endometrial cancer (SHREC-trial) – The final step towards a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballester M, Dubernard G, Lécuru F, Heitz D, Mathevet P, Marret H, et al. Detection rate and diagnostic accuracy of sentinel-node biopsy in early stage endometrial cancer: A prospective multicentre study (SENTI-ENDO) Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:469–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlappe BA, Weaver AL, McGree ME, Ducie J, Eriksson AG, Dowdy SC, et al. Multicenter study comparing oncologic outcomes after lymph node assessment via a sentinel lymph node algorithm versus comprehensive pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with serous and clear cell endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim CH, Soslow RA, Park KJ, Barber EL, Khoury-Collado F, Barlin JN, et al. Pathologic ultrastaging improves micrometastasis detection in sentinel lymph nodes during endometrial cancer staging. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:964–70. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182954da8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holloway RW, Gupta S, Stavitzski NM, Zhu X, Takimoto EL, Gubbi A, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping with staging lymphadenectomy for patients with endometrial cancer increases the detection of metastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baiocchi G, Mantoan H, Kumagai LY, Gonçalves BT, Badiglian-Filho L, de Oliveira Menezes AN, et al. The Impact of Sentinel Node-Mapping in Staging High-Risk Endometrial Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3981–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang S, Yoo HJ, Hwang JH, Lim MC, Seo SS, Park SY. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: Meta-analysis of 26 studies. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cormier B, Rozenholc AT, Gotlieb W, Plante M, Giede C. Communities of Practice (CoP) Group of Society of Gynecologic Oncology of Canada (GOC). Sentinel lymph node procedure in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and proposal for standardization of future research. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanner EJ, Sinno AK, Stone RL, Levinson KL, Long KC, Fader AN. Factors associated with successful bilateral sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Uterine neoplasms Version 1. 2019 – October 17. 2018. [[Last accessed on 2020 Dec 14]]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf .