Abstract

Background

Chemotherapy-induced premature menopause leads to some consequences, including infertility. We initiated this randomized phase III trial to determine whether a cyclophosphamide-free adjuvant chemotherapy regimen would increase the likelihood of menses resumption and improve survival outcomes.

Methods

Young women with operable estrogen receptor-positive HER2-negative breast cancer after definitive surgery were randomly assigned to receive adjuvant epirubicin and cyclophosphamidefollowed by weekly paclitaxel (EC-wP) or epirubicin and paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel (EP-wP). All patients received at least 5-year adjuvant endocrine therapy after chemotherapy. Two coprimary endpoints were the rate of menstrual resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy and 5-year disease-free survival in the intention-to-treat population. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01026116). All statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

Between January 2011 and December 2016, 521 patients (median age = 34 years; interquartile range = 31-38 years) were enrolled, with 261 in the EC-wP group and 260 in the EP-wP group. The rate of menstrual resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy was 48.3% in EC-wP (95% confidence interval [CI] = 42.2% to 54.3%) and 63.1% in EP-wP (95% CI = 57.2% to 68.9%), with an absolute difference of 14.8% (95% CI = 6.37% to 23.2%, P < .001). The posthoc exploratory analysis by patient-reported outcome questionnaires indicated that pregnancy might occur in fewer women in the EC-wP group than in the EP-wP group. At a median follow-up of 62 months, the 5-year disease-free survival was 78.3% (95% CI = 72.2% to 83.3%) in EC-wP and 84.7% (95% CI = 79.3% to 88.8%) in EP-wP (stratified log-rank P = .07). The safety data were consistent with the known safety profiles of relevant drugs.

Conclusions

The cyclophosphamide-free chemotherapy regimen might be associated with a higher probability of menses resumption.

Young age is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer (1). Adjuvant chemotherapy has been firmly established as an effective treatment for breast cancer in previous meta-analyses, especially in patients with young age and higher cancer burden (2). Cyclophosphamide, which is widely used in combination with anthracycline and/or taxane as adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer, may directly damage oocytes in primordial follicles, and premature menopause induced by cyclophosphamide-containing chemotherapy leads to sexual dysfunction, vasomotor symptoms, and infertility (3).

According to the updated European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology guidelines and European Society for Medical Oncology Clinical Practice guidelines, luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonists (LHRHa) during chemotherapy is recommended to reduce the risk of chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure (4,5), and other approaches are needed. Cyclophosphamide is strongly associated with chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian failure, whereasthe addition of a taxane might exert less of an effect on amenorrhea (6). The substitution of cyclophosphamide with paclitaxel might result in a reduced incidence of ovarian failure and an increased likelihood of early menses resumption. It has been reported that the substitution of paclitaxel for cyclophosphamide results in comparable efficacy in a general population but might produce greater benefits in high-risk patients (7).

Therefore, we designed the present clinical trial to investigate 2 coprimary endpoints in young women with ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer. The first endpoint compares the menstrual resumption rate of the standard regimen (epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel [EC-wP]) with the cyclophosphamide-free chemotherapeutic regimen (epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel [EP-wP]), and the second investigates the disease-free survival (DFS) between the patients treated with the 2 regimens.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Substitution of Paclitaxel for Cyclophosphamide on Survival Outcomes and Resumption of Menses in Young Women with ER-Positive Breast Cancer trial is a randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase III trial performed at 8 hospitals in China. It was designed to compare the difference in menses resumption rates, as well as in DFS, between the EC-wP and EP-wP groups in young women.

Women aged 18 to 40 years with unilateral operable primary invasive ER-positive HER2-negative breast cancer were eligible for enrollment following definitive surgery. Because platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy might be an effective treatment for triple-negative breast cancer (8), and anti-HER2 treatments are pivotal for HER2-positive disease, we excluded young patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive cancers and focused on women with ER-positive and HER2-negative disease.

Patients were required to have pathologically confirmed regional node-positive disease or node-negative disease with high-risk factors (primary tumor diameter >10 mm when histological grade III or tumor diameter >20 mm when histological grade II). ER, progesterone receptor, and HER2 statuses were identified locally at each participating center based on immunohistochemistry of tumor sections. The immunohistochemical cutoff for ER-positive or progesterone receptor–positive statuswas 1% or more staining in nuclei (9). HER2-negative status was defined as immunohistochemistry score 0 or 1 or the absence of HER2 amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (10). The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was required to be 0 or 1.

To assess menstrual status accurately, eligible participants should take no estrogens, antiestrogens, selective estrogen-receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors, LHRHa, or hormonal contraceptives within the month before enrollment. Patients had regular menstrual cycles and normal menses before surgery. The regular menstrual cycles should occur every 21 to 35 days, with menstruation lasting 2 to 7 days (11-13). Patients who underwent hysterectomy or bilateral salpingectomy, oophorectomy, or salpingo-oophorectomybefore enrollment were ineligible because they were not evaluable for menses. A complete description of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the protocol (available in Supplementary Methods, available online).

The independent institutional review boards of the participating centers approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. We performed the study according to the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01026116).

Randomization and Masking

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) using a web-response system. A permuted-block randomization scheme was used with stratification according to pathological node status (negative vs positive), tumor size (pT1 vs pT2-3), and age (≤35 years vs 35-40 years). The stratification factors were used for stratified analyses unless indicated otherwise.

Procedures

The participants’ baseline characteristics were recorded at random assignment. The concurrent use of taxane and anthracycline might increase the toxicity, such as febrile neutropenia (14). Therefore, we modified the dose of epirubicin to 75 mg/m2 rather than the standard dosage of 90-100 mg/m2. Epirubicin 75 mg/m2 was considered an acceptable dosage based on the EORTC 10994/BIG 1–00 trial, where the survival efficacy of epirubicin 75 mg/m2 was not compromised and the toxicity was reduced compared with epirubicin 100 mg/m2 (15). We also balanced the total dose of epirubicin between the 2 regimens to increase the comparability.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive epirubicin (75 mg/m2) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) for 12 weeks (EP-wP) or epirubicin (75 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) for 12 weeks.

After chemotherapy, all patients were recommended to receive 20 mg/d of tamoxifen for at least 5 years. If an ovarian suppression treatment was administered after adjuvant chemotherapy, the patients should have experienced at least 1 menstruation and be diagnosed as premenopausal according to the follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol levels (16). In 2015, the SOFT and TEXTtrials showed that, for women who were at sufficient recurrence risk and remained premenopausal, the use of ovarian suppression (LHRHa) with tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor would improve survival (17). For ethical reasons, after 2015, the high-risk young patients were permitted to be treated with ovarian suppression before the apparent menses resumption after chemotherapy. Patients were told of their potential choice of endocrine therapy regimens before random assignment, and the type of endocrine therapy was mainly determined by physicians according to the patients’ risk. However, we were near the end of our patient recruitment in 2015, and only approximately 5% of patients used upfront ovarian suppression with an aromatase inhibitor.

Outcomes

The 2 coprimary endpoints were the rate of menstrual resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy and the 5-year DFS in the intention-to-treat population.

Resumption of menses was defined as at least 2 consecutive menstruations or at least 1 menstruation with a confirmed premenopausal level of follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol after chemotherapy (18). Patients with no results for menstrual resumption (because of a loss to follow-up, early intervention of ovarian suppression, or any recurrence event if it occurred first) were treated as nonresumed in the menses analysis. DFS was defined as the time from random assignment to breast cancer recurrence, second primary breast and other cancers, and death from any cause.

Secondary endpoints included distant DFS, overall survival, and toxicity. Toxicity was graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.0. All reported serious adverse events were judged by an independent data safety and monitoring board.

The posthoc exploratory analysis of pregnancy within 48 months was performed in May 2020. Pregnancy outcomes were assessed by patient-reported outcome questionnaires via telephone survey because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Statistical Analysis

Two coprimary endpoints were investigated, and the study was considered positive if either the DFS and/or the menstrual resumption results were statistically significant.

To address multiple endpoint-related multiplicity problems, we used the unequally weighted Bonferroni method by dividing the overall α into unequal portions (19). The type I error (α = 0.05) was controlled and split between the analyses of DFS (α = 0.04) and menstrual resumption rate (α = 0.01). Interim analysis was not planned, because the EP-wP and EC-wP had been previously investigated in the Loesch study (7), and it showed that the toxicity of the 2 regimens is manageable and tolerable. Long-term observation time is needed to observe menses resumption and pregnancy.

To detect an absolute 15% improvement in the menstrual resumption rate between EC-wP (assumed 65%) and EP-wP (assumed 80%), a 2-sided test of resumption rates with 80% power required 440 patients to achieve a .01 level of statistical significance. To detect an absolute 8% improvement in the 5-year DFS rate between the EC-wP group (assumed 80%) and EP-wP group (assumed 88%), a 2-sided log-rank test with 80% power required 480 patients (240 for each arm) to show a .04 statistical significance level, with approximately 90 DFS events expected after a median 5-year follow-up. Considering a 5% loss to follow-up, we calculated approximately 500 patients required.

The cumulative incidence estimates of menstrual resumption were calculated, and the between-group differences were compared by the stratified Miettinen and Nurminen method (20). Stratified logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of menses resumption. Fine-Gray competing risk regression model (Stata command: stcrreg) was used to calculate the odds ratio of menses recovery, accounting for DFS events as competing risk events (21). In the sensitivity analysis, the proportion of menses resumption between groups was compared using the stratified Mantel-Haenszel test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate DFS, and survival rates were compared using the stratified log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a stratified Cox proportional hazards model.

The findings of secondary endpoints should be interpreted as exploratory because of the potential for type I error from multiple comparisons. For other continuous and categorical variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and χ2 test were used to evaluate differences between the 2 groups, respectively. All statistical tests were 2-sided, a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and analyses were performed using STATA 16.0 software (StataCorp LLC).

Results

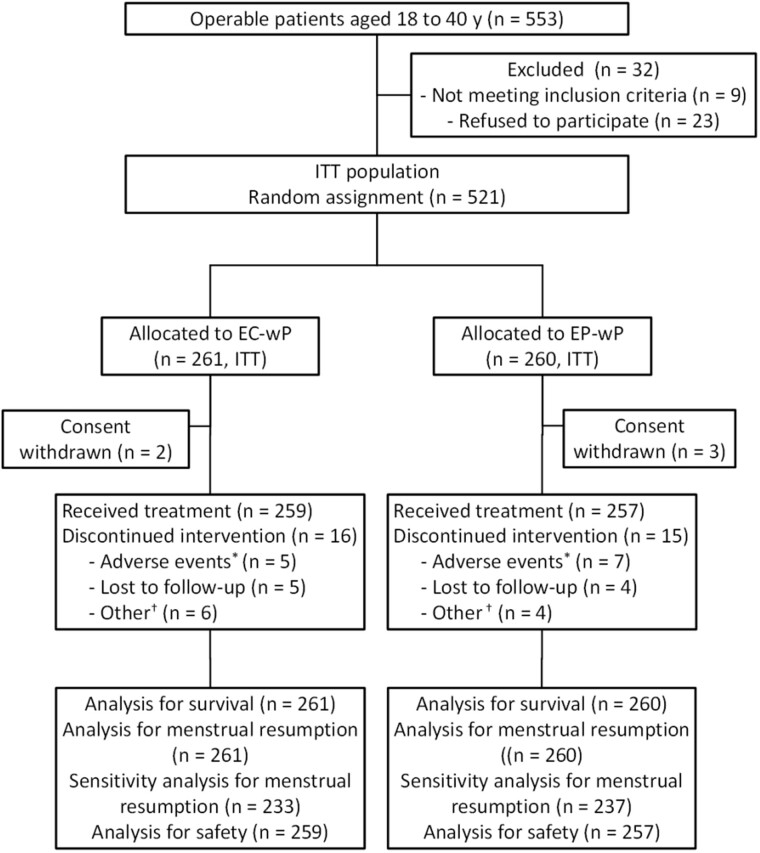

From January 2011 to December 2016, 521 patients (median age = 34 years, interquartile range = 31-38 years) with ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer were enrolled, with 261 in the EC-wP group and 260 in the EP-wP group. Figure 1 shows the trial profile. Chemotherapy was completed by 93.9% of patients in the EC-wP group and 94.2% of those in the EP-wP group. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics were well balanced between treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile. *Adverse events indicate grade 3 and 4 events; †Other reasons except for adverse events. EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel; ITT, intention to treat.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by treatment group

| Characteristics | Total (n = 521) | EC-wP (n = 261) | EP-wP (n = 260) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Median age (interquartile range), y | 35 (31-38) | 35 (32-38) | 35 (31-37) |

| Age, y | |||

| ≤35 | 284 (54.5) | 145 (55.6) | 139 (53.5) |

| >35 | 237 (45.5) | 116 (44.4) | 121 (46.5) |

| Pathologic tumor size | |||

| pT1 | 231 (44.3) | 115 (44.1) | 116 (44.6) |

| pT2-3 | 290 (55.7) | 146 (55.9) | 144 (55.4) |

| Pathologic node status | |||

| Negative | 216 (41.5) | 110 (42.1) | 106 (40.8) |

| Positive | 305 (58.5) | 151 (57.9) | 154 (59.2) |

| Histological grade | |||

| I-II | 279 (53.6) | 143 (54.8) | 136 (52.3) |

| III | 242 (46.4) | 118 (45.2) | 124 (47.7) |

| Surgery | |||

| BCS | 168 (32.2) | 83 (31.8) | 85 (32.7) |

| Mastectomy | 353 (67.8) | 178 (68.2) | 175 (67.3) |

| Adjuvant radiation | |||

| No | 212 (40.7) | 109 (41.8) | 103 (39.6) |

| Yes | 309 (59.3) | 152 (58.2) | 157 (60.4) |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | |||

| Tamoxifen | 409 (78.5) | 200 (76.7) | 209 (80.4) |

| LHRHa + tamoxifena | 62 (11.9) | 33 (12.6) | 29 (11.2) |

| LHRHa + aromatase inhibitor | 27 (5.2) | 16 (6.1) | 11 (4.2) |

| LHRHa alone | 15 (2.9) | 7 (2.7) | 8 (3.1) |

| No endocrine treatment | 8 (1.5) | 5 (1.9) | 3 (1.1) |

Included LHRHa + tamoxifen followed by an aromatase inhibitor. BCS = breast conservative surgery; EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel; LHRHa = luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist.

For the primary endpoint of menstrual resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy, the rates were 48.3% (95% CI = 42.2% to 54.3%) for the EC-wP group and 63.1% (95% CI = 57.2% to 68.9%) for the EP-wP group, and the absolute difference was 14.8% (95% CI = 6.37% to 23.2%, P < .001; Table 2) with an estimated odds ratio of 1.83 (95% CI = 1.29 to 2.60). When accounting for DFS events by competing risk, the adjusted odds ratio was 1.55 (95% CI = 1.23 to 1.95, P < .001). We further conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding case patients with unknown information on menses resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy (Table 2). Among the 470 patients (233 in the EC-wP group and 237 in the EP-wP group), menses had resumed in 126 patients (54.1%) in EC-wP group and 164 patients (69.2%) in the EP-wP group, with an odds ratio of 1.94 (95% CI = 1.33 to 2.84, P < .001).

Table 2.

Menstrual resumption rate by treatment group

| Outcomes | EC-wP |

EP-wP |

Estimated differencea, % (95% CI) |

P b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./total | % (95% CI) | No./total | % (95% CI) | |||

| Menstrual resumption at 12 moc | ||||||

| Intention-to-treat analysis | 126/261 | 48.3 (42.2 to 54.3) | 164/260 | 63.1 (57.2 to 68.9) | 14.8 (6.4 to 23.2) | <.001d |

| Sensitivity analysis | 126/233 | 54.1 (47.7 to 60.5) | 164/237 | 69.2 (63.3 to 75.1) | 15.1 (6.4 to 23.8) | <.001e |

| Pregnancy outcomes | ||||||

| Considered pregnancy at enrollment | 34/113 | 30.1 (21.6 to 38.5) | 33/115 | 28.7 (20.4 to 37.0) | −1.4 (−13.2 to 10.4) | .82 |

| Attempted pregnancy within 48 mo | 11/113 | 9.7 (4.3 to 15.2) | 19/115 | 17.4 (10.5 to 24.3) | 7.7 (−1.2 to 16.5) | .09 |

| Achieved pregnancy within 48-month | 3/113 | 2.7 (0 to 5.6) | 11/115 | 9.6 (4.2 to 14.9) | 6.9 (0.7 to 13.0) | .03 |

aThe estimated treatment difference was calculated, and the between-group difference was tested by the stratified Miettinen and Nurminen method. CI = confidence interval; EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel.

bP values were based on χ2 test and were 2-sided, if not specified.

cResumption time is calculated from the last dose of adjuvant chemotherapy. In the intention-to-treat analysis, patients with no results of menstrual resumption, because of loss to follow-up, early intervention of ovarian suppression, or any recurrence event if it occurred first, were treated as nonresumed. The cases with no results of menstrual resumption were excluded in the sensitivity analysis.

dThe rate of menstrual resumption at 12 months after chemotherapy is the coprimary endpoint, and the statistical significance level is .01. The P value was based on the stratified Miettinen and Nurminen method and was 2-sided.

eIn the sensitivity analysis, comparisons of the resumption rate between groups used the stratified Mantel-Haenszel testand the P value was 2-sided.

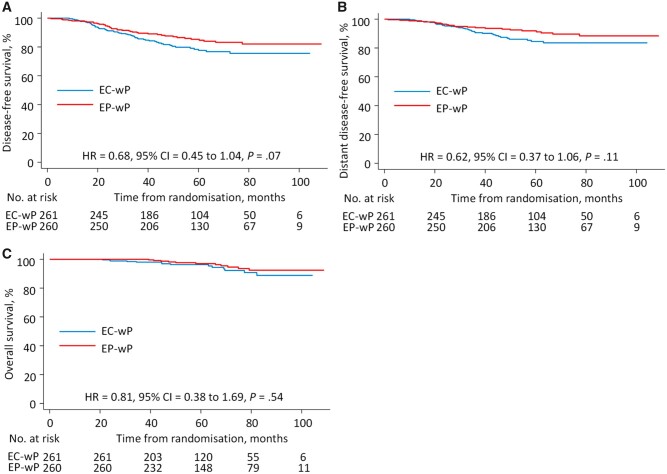

Regarding the other primary endpoint of DFS, at a median follow-up of 62 months (interquartile range = 45-82 months), 92 DFS events were observed in the intention-to-treat population, including 53 (20.3%) in the EC-wP group and 39 (15.0%) in the EP-wP group (Table 3). The 5-year DFS rate was 78.3% (95% CI = 72.2% to 83.3%) in the EC-wP group and 84.7% (95% CI = 79.3% to 88.8%) in the EP-wP group (stratified log-rank P = .07) (Figure 2, A), with a stratified hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI = 0.45 to 1.04). No statistically significant differences in distant DFS (HR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.37 to 1.06, P = .11) or overall survival (HR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.38 to 1.69, P = .54) were observed (Figure 2, B and C).

Table 3.

First disease-free survival event by treatment groupa

| Disease-free survival event | EC-wP (n = 261) | EP-wP (n = 260) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Local and regional recurrence | 10 (3.8) | 7 (2.7) |

| Distant metastasis | 34 (13.0) | 23 (8.8) |

| Contralateral breast tumor | 5 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) |

| Second primary malignancy | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.5) |

| Death | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 53 (20.2) | 39 (14.9) |

EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel.

Figure 2.

Survival outcomes. Kaplan-Meier plots for disease-free survival (A), distant disease-free survival (B), and overall survival (C) are shown. P values were based on the stratified log-rank test and were 2-sided. CI = confidence interval; EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel; HR = hazard ratio.

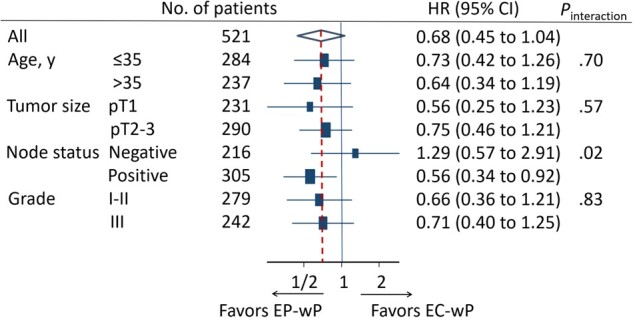

In posthoc exploratory analysis of pregnancy outcomes (within 48 months) in the 228 patients who completed the questionnaire survey, 11 of 113 (9.7%, 95% CI = 4.3% to 15.2%) patients in the EC-wP group and 19 of 115 (17.4%, 95% CI = 10.5% to 24.3%) patients in the EP-wP group reported an attempt to become pregnant (P = .09). Successful pregnancy occurred in fewer women in the EC-wP group than in the EP-wP group (2.7% vs 9.6%, P = .03; Table 2). The median time interval between random assignment and pregnancy was 42 months. In exploratory subgroup analyses of DFS, patients with the node-positive disease appeared to benefit more from EP-wP treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of subgroup analysis of disease-free survival. All statistical tests were 2-sided. CI = confidence interval; EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel; HR = hazard ratio.

Patients who received at least 1 cycle of chemotherapy were included in the safety analysis (259 in EC-wP and 257 in EP-wP). Treatment-related grade 3 to 4 adverse events are listed in Table 4. Both treatments were generally well tolerated, and all serious adverse events were resolved and were nonfatal.

Table 4.

Grade 3 to 4 treatment-related adverse events

| Adverse events | EC-wPa (n = 259) | EP-wPa (n = 257) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia | 195 (75.3) | 203 (79.0) |

| Leukopenia | 169 (65.3) | 159 (61.9) |

| Anemia | 8 (3.1) | 5 (1.9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (1.9) | 4 (1.6) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Neuropathy and paresthesiab | 12 (4.6) | 25 (9.7) |

| Arthralgia and myalgia | 26 (10.0) | 21 (8.2) |

| Nausea | 22 (8.5) | 13 (5.1) |

| Fatigue | 16 (6.2) | 22 (8.6) |

| Vomitingc | 19 (7.3) | 8 (3.1) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) |

| Allergic | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) |

| Edema | 8 (3.1) | 16 (6.2) |

| Stomatitis | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Constipation | 8 (3.1) | 2 (0.8) |

| Laboratory-assessed items | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 5 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 6 (2.3) | 6 (2.3) |

| Hyperglycemia | 3 (1.2) | 5 (1.9) |

EC-wP = epirubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel; EP-wP = epirubicin/paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel.

2-sided P = .02 by χ2 test.

2-sided P = .03 by χ2 test.

Discussion

The Substitution of Paclitaxel for Cyclophosphamide on Survival Outcomes and Resumption of Menses in Young Women with ER-Positive Breast Cancer trial was designed to determine whether EP-wP is superior to standard EC-wP and whether the elimination of cyclophosphamide would result in a higher menstrual resumption rate at 12 months after chemotherapy in young patients with ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial to compare 2 adjuvant chemotherapy regimens specifically in young patients with ER-positive breast cancer.

Recent guidelines have recommended LHRHa given concurrently with chemotherapy as a strategy to reduce the risk of premature menopause (4,5). For the first time, to our knowledge, we demonstrate that a cyclophosphamide-free regimen could increase the rate of menses recovery without comprising survival. Our results are consistent with the findings from the NSABPB-30 trial, in which 76.4% of patients in the doxorubicin-docetaxel group experienced amenorrhea for at least 6 months compared with 89.5% of patients in the doxorubicin-docetaxel-cyclophosphamide group (22). It seems that the menstrual resumption rate in our study is somewhat lower than the data reported elsewhere. In the ZORO trial, the reappearance of menstruation at 6 months was 70% for the LHRHa group and 57% for the chemotherapy-only group (11). Another study indicates that the rate of 12-month menstrual resumption in young breast cancer women was up to 85% (23). A potential explanation is the common use of tamoxifen in our enrolled ER-positive patients. It has been reported that menstrual pattern changes, including amenorrhea, were more frequent in patients on tamoxifen treatment (24).

In our trial, the primary endpoint was the menstrual resumption rate, and 2 other trials, POEMS and PROMISE-GIM6 (25,26), chose the ovarian failure rate and the early menopause incidence, respectively. Nevertheless, regular menses resumption is a clinically relevant outcome and is a requirement for subsequent fertility. Our trial’s posthoc exploratory analysis indicated that pregnancy occurred in more women in the EP-wP group than in the EC-wP group.

In the era of molecular oncology, a better approach is to analyze patients with high-risk ER-positive breast cancer and subsequently perform translational research using tissue samples to provide more precise genetic or genomic information. In 2011 when the trial was initiated, gene expression arrays were not popular for subtype classification and optimal treatment determination. The results of a prospective trial of 21 genes(TAILORx) were published in 2015 (27), and those of 70 genes (MINDACT) were published in 2016 (28). We tried our best to restrict our study to high-risk patients. According to the inclusion criteria of our trial, all the patients enrolled were defined as clinically high-risk patients based on the modified version of Adjuvant! Online in the MINDACT design (28). These young and clinically high-risk patients might not avoid adjuvant chemotherapy even when with the genomic low-risk disease according to the updated analysis of the MINDACT trial (29).

Currently, young high-risk patients with ER-positive breast cancer are likely to receive 5-year ovarian suppression. A cyclophosphamide-free regimen, which is associated with ovarian protection, is not contradictory to a subsequent ovarian suppression strategy during endocrine therapy. In routine clinical practice, patients who have yet to complete their 5-year ovarian suppression period are not recommended candidates for pregnancy. However, it is noteworthy that our findings can be extrapolated to patients with other subtypes of breast cancer, such as triple negative or HER2 enriched, because the effect of paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide on menstrual resumption is not cancer subtype specific.

Another critical and controversial issue raised was when and how to conceive after breast cancer. The standard duration of endocrine therapy is at least 5 years, and all the patients who had a pregnancy within 48 months interrupted their endocrine therapy. According to the St. Gallen Breast Cancer Consensus, for women contemplating pregnancy after breast cancer, the optimal timing and impact of interrupting endocrine therapy is unknown. However, the panel recommended a minimum of 18 months following diagnosis before anticipated pregnancy (30). Several clinical studies have investigated the optimal timing for pregnancy after breast cancer. In a matched case-control study, no DFS difference was observed between the pregnant and nonpregnant cohorts in ER-positive patients. In that study, approximately 60% of cases were pregnant after 2 years from surgery, though time to pregnancy had no statistically significant impact on survival (31,32). Another study showed a trend toward increased risk of recurrence in patients who conceived within 24 months after diagnosis (33). In our clinical practice, we asked women contemplating pregnancy to conduct restaging scans before attempting conception and suggested a minimum 24-month interval between diagnosis and anticipated pregnancy. The decision of pregnancy should be very discreet. Subsequent adequate follow-up among breast cancer survivors is crucial (34), and women who temporarily interrupt endocrine therapy due to pregnancy should be reminded to resume endocrine therapy following attempted or successful pregnancy.

Limitations of the trial included that we did not consider the rates of pregnancy or successful delivery as secondary endpoints due to the high probability of confounding factors. But we reported the posthoc exploratory analysis of pregnancy outcomes. Moreover, early intervention with LHRHa makes it impossible to observe menses resumption. We thus performed sensitivity analyses as complementary results to augment the main findings. We also did not report on the pattern of menstruation, and irregular menses might also lead to infertility. The fertility function should be further evaluated by measuring the levels of other markers, such as anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin. Anti-Müllerian hormone may help to separate patients with amenorrhea due to tamoxifen use from those with loss of ovarian reserve. In addition, contrasting pathological characteristics of breast cancer between Asian and American women suggest racial differences in biology (35), and whether our findings can be extrapolated to other races is unknown. Furthermore, the recurrence of ER-positive breast cancer occurs at a steady rate during 5 to 20 years, and an adequate follow-up is needed for more reliable survival outcomes (36). Finally, in the era of genetic testing, information on gene predisposition for early-onset patients might provide new insights. Although young women with triple-negative breast cancer have higher mutation rates in BRCA1/2, RAD51C, and RAD51D genes (8,37), the germline mutation spectrum in young women with ER-positive or HER2-negative breast cancer as well as its effect on chemotherapy sensitivity are unknown and warrant further study.

In conclusion, among young women with ER-positive breast cancer, the cyclophosphamide-free regimen might be associated with a statistically significantly higher probability of menses resumption.

Funding

Supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81672600, 81722032, 82072916, and 91959207), the 2018 Shanghai Youth Excellent Academic Leader, the Fudan ZHUOSHI Project, the Municipal Project for Developing Emerging and Frontier Technology in Shanghai Hospitals (grant SHDC12010116), the Cooperation Project of Conquering Major Diseases in the Shanghai Municipality Health System (grant 2013ZYJB0302), the Innovation Team of the Ministry of Education (grant IRT1223), and the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Breast Cancer (grant 12DZ2260100).

Notes

Role of the funders: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: No disclosures are reported.

Author contributions: KDY: Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing; Supervision. JGG: Project administration; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing. XYL: Project administration; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing. MM: Methodology; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing. MH: Methodology; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing. ZMS: Conceptualization; Project administration; Writing; Supervision. SI: Project administration; Writing. All authors were involved in writing (review and editing).

Acknowledgements: We thank Dr Jiong Wu, Guang-Yu Liu, Gen-Hong Di, Yi-Feng Hou, Zhen Hu, Can-Ming Chen, Zhen-Zhou Shen, Lei Fan, and Li Chen (Department of Breast Surgery, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center) for their efforts in the conduction of this trial. We also thank Dr Wen-Jin Yin (Department of Breast Surgery, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University) for the involvement in the original design of this trial.

The following investigators participated in the SPECTRUM trial, and their affiliations are listed: Xiao-Hua Zeng, Breast Center, Chongqing Cancer Hospital, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China; Ping-Qing He, Department of Breast Surgery, Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China; Ke-Jin Wu, Department of Breast Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China; Jie Wang, Department of Breast Surgery, The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital of China Welfare Institute, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China; Zhi-Gang Zhuang, Department of Breast Surgery, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, Shanghai Tongji University, Shanghai, China; Cheng Wang, Department of Breast Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Huangpu Branch, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China; and Xiao-Yan Lin, Department of Breast Surgery, Tongji University School of Medicine Yangpu Hospital, Shanghai, China.

Data Availability

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article will be shared after de-identification. Data will be available 3 months after publication. Researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal might access the individual participant data. Proposals should be directed to yukeda@fudan.edu.cn. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Partridge AH, Hughes ME, Warner ET, et al. Subtype-dependent relationship between young age at diagnosis and breast cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3308–3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Increasing the dose intensity of chemotherapy by more frequent administration or sequential scheduling: a patient-level meta-analysis of 37 298 women with early breast cancer in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10179):1440–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen QN, Zerafa N, Liew SH, et al. Cisplatin- and cyclophosphamide-induced primordial follicle depletion is caused by direct damage to oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2019;25(8):433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambertini M, Peccatori FA, Demeestere I, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Fertility preservation and post-treatment pregnancies in post-pubertal cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1664–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson RA, Amant F, Braat D, et al. ESHRE guideline: female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(4):hoaa052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kado R, McCune WJ.. Ovarian protection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during cyclophosphamide therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;64(1):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loesch D, Greco FA, Senzer NN, et al. Phase III multicenter trial of doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel compared with doxorubicin plus paclitaxel followed by weekly paclitaxel as adjuvant therapy for women with high-risk breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):2958–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu KD, Ye FG, He M, et al. Effect of adjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin on survival in women with triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1390–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2784–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. ; College of American Pathologists. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3997–4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber B, von Minckwitz G, Stehle H, et al. ; German Breast Group Investigators. Effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist on ovarian function after modern adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: the GBG 37 ZORO Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2334–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiazze L Jr, Brayer FT, Macisco JJ Jr, et al. The length and variability of the human menstrual cycle. JAMA. 1968;203(6):377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Broder M, et al. The FIGO recommendations on terminologies and definitions for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(5):383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackey JR, Pieńkowski T, Crown J, et al. Long-term outcomes after adjuvant treatment of sequential versus combination docetaxel with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in node-positive breast cancer: BCIRG-005 randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnefoi H, Piccart M, Bogaerts J, et al. TP53 status for prediction of sensitivity to taxane versus non-taxane neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer (EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):527–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuzick J, Ambroisine L, Davidson N, et al. ; LHRH-agonists in Early Breast Cancer Overview group. Use of luteinising-hormone-releasing hormone agonists as adjuvant treatment in premenopausal patients with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised adjuvant trials. Lancet. 2007;369(9574):1711–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bines J, Oleske DM, Cobleigh MA.. Ovarian function in premenopausal women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(5):1718–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dmitrienko A, Tamhane AC, Bretz F.. Multiple Testing Problems in Pharmaceutical Statistics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miettinen O, Nurminen M.. Comparative analysis of two rates. Stat Med. 1985;4(2):213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ.. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swain SM, Jeong JH, Wolmark N.. Amenorrhea from breast cancer therapy--not a matter of dose. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(23):2268–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fornier MN, Modi S, Panageas KS, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced, long-term amenorrhea in patients with breast carcinoma age 40 years and younger after adjuvant anthracycline and taxane. Cancer. 2005;104(8):1575–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien AJ, Duralde E, Hwang R, et al. Association of tamoxifen use and ovarian function in patients with invasive or pre-invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;153(1):173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore HCF, Unger JM, Phillips KA, et al. Final analysis of the prevention of early menopause study (POEMS)/SWOG intergroup s0230. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambertini M, Boni L, Michelotti A, et al. ; GIM Study Group. Ovarian suppression with triptorelin during adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy and long-term ovarian function, pregnancies, and disease-free survival: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2632–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2005–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardoso F, van't Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. ; MINDACT Investigators. 70-gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardoso F, Veer L, Poncet C, et al. MINDACT: long-term results of the large prospective trial testing the 70-gene signature MammaPrint as guidance for adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl 15):506. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, P Winer E, E PW, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: The St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azim HA Jr, Kroman N, Paesmans M, et al. Prognostic impact of pregnancy after breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status: a multicenter retrospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambertini M, Kroman N, Ameye L, et al. Long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(4):426–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ives A, Saunders C, Bulsara M, et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer: population based study. BMJ. 2007;334(7586):194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruddy KJ, Herrin J, Sangaralingham L, et al. Follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(1):111–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin CH, Yap YS, Lee KH, et al. ; The Asian Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Contrasting epidemiology and clinicopathology of female breast cancer in Asians vs the US population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(12):1298–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, EBCTCG, et al. 20-Year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li N, McInerny S, Zethoven M, et al. Combined tumor sequencing and case-control analyses of RAD51C in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(12):1332–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article will be shared after de-identification. Data will be available 3 months after publication. Researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal might access the individual participant data. Proposals should be directed to yukeda@fudan.edu.cn. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.