Abstract

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis was applied to detect allelic variation and multilocus genotypes (electrophoretic types [ETs]) among 43 Escherichia coli isolates from weaned pigs suffering from edema disease or from diarrhea. ETs were analyzed in relation to O serogroups and virulence genes (sta, stb, lt, stx2, and f18) by DNA hybridization. Genomic diversity was the lowest in serogroup O138, while virulence genes (stx2 and f18) were the most uniform in serogroup O139. In general, the serogroups or toxin and F18 fimbria types were not related to selected ETs, suggesting that the toxin and f18 fimbria genes in E. coli isolates from pigs with postweaning diarrhea or edema disease occur in a variety of chromosomal backgrounds.

Major factors influencing bacterial pathogenicity are the families of attachment factors (comprised of fimbriae) and toxins often encoded on plasmid DNA, thereby moving horizontally among the population of Escherichia coli. It has been clearly demonstrated that the adherence factors and toxins of enterotoxigenic E. coli that infect farm animals, namely, calves and pigs, occur in isolates from a limited number of serotypes (13, 15, 16, 25, 29), suggesting host specificity of adhesin-receptor interactions and genetic links between determinants of O types and adhesin and toxin types. It has been shown that porcine postweaning diarrhea (PWD) strains often carry enterotoxin genes and express F4 (and occasionally also F5, F6, or F41) fimbriae (29), whereas edema disease (ED) isolates tend to be F4, F5, F6, and F41 negative and strains often produce Shiga-like toxin 2v (2, 9, 14), detectable on Vero cells, also called verotoxigenic E. coli. The application of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) to the study of E. coli populations has demonstrated that the O serogroups associated with infectious diseases occur in a variety of chromosomal backgrounds (21).

The purpose of the present study was to assess the diversity of chromosomal backgrounds and to characterize the distribution of virulence factors of PWD and ED strains of E. coli lacking the fimbriae described above. To this end, we characterized a variety of porcine PWD and ED strains by MLEE, DNA probe assays, and serological tests. In addition to testing for toxigenicity, attention was directed to the newly described fimbriae F18ab (F107) and F18ac (2134P and 8813), adhesins recently associated with ED and PWD isolates as described by Bertschinger et al. (3), Casey et al. (4), Nagy et al. (18), and Salajka et al. (23) respectively, and proven to be variants of F18 fimbriae (10, 19, 22).

A total of 43 E. coli isolates were obtained from the small-intestinal contents or the feces of weaned pigs suffering from PWD or ED and were selected on the basis of producing no K88 (F4), K99 (F5), 987P (F6), or F41 fimbriae. Strains with four-digit number designations (except strain 2228) were isolated in Hungary and were partially characterized earlier (17), whereas strains with six-digit number designations were isolated in the United States and represent a subset of strains from an earlier study (30). Each strain was isolated from a different pig except for strains 2155 and 2156. Strain 2228 is a Swiss isolate, kindly provided by A. O’Brien (Bethesda, Md.). The strains were serotyped by standard methods at the Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark, or at the E. coli Reference Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pa. The presence of F18ac fimbriae was analyzed by fluorescent microscopy (18) using monoclonal antibodies as described previously (5) for testing bacteria grown on Iso-Sensitest agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) with alizarin yellow (Fluka AG, Buchs, Switzerland) added, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere as described by Wittig et al. (31). Enterotoxin genes sta, stb, and lt as well as Shiga-like toxin (stx2) and fimbrial (f18) genes were detected by colony hybridizations performed according to the method of Grunstein and Hogness (6). The stb probe was prepared from the recombinant plasmid pRAS-1, the sta probe was prepared from the recombinant plasmid pSTP6, and the lt probe was prepared from the recombinant plasmid pWD299. The f18 probe that detects both F18ab and F18ac (8, 10, 22) was obtained from strain 4748, and the stx2 probe that detects both Stx2 and Stx2v toxin genes was obtained from the recombinant plasmid pNN111-19 (20) by the method of Lee et al. (12). The probes were labeled by nick translation with [32P]dATP. MLEE was applied to detect allelic variation at 20 enzyme loci by the methods described by Whittam et al. (28). Strains were characterized by their multilocus array of alleles and classified into distinct electrophoretic types (ETs). The genetic relationships among isolates were assessed by groupings inferred from cluster analysis (24, 28).

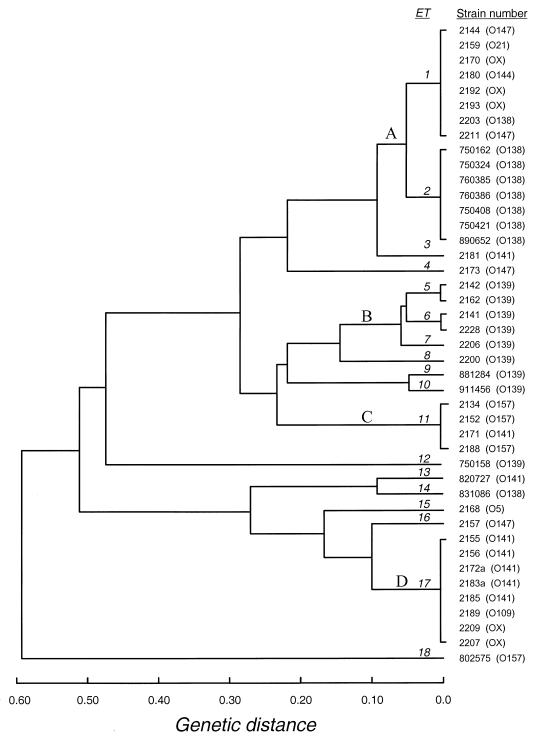

The 43 strains were allotted to serogroups O157, O147, O141, O139, O138, O109, O21, O5, and OX. The association of the serogroups with the virulence genes sta, stb, lt, stx2 and f18 and the ETs is provided in Table 1. The f18 fimbria gene was detected in all major serogroups. Although most serogroups represented closely related ETs (Fig. 1), not all members of a serogroup shared the same virulence genes nor did they express the same surface fimbriae.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of E. coli isolates from pigs with PWD and ED

| Strain | Serogroupa | Characteristicd

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stab | stbb | ltb | stx2b | F18acc | f18b | ET | ||

| 2134P | O157 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 11 |

| 2152 | O157 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 11 |

| 2188 | O157 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 11 |

| 802575 | O157 | + | − | + | − | − | − | 18 |

| 2211 | O147 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 1 |

| 2144 | O147 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 1 |

| 2173 | O147 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 4 |

| 2157 | O147 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 16 |

| 2185 | O141 | + | + | − | +/− | + | + | 17 |

| 2172 | O141 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 17 |

| 2171 | O141 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 11 |

| 2155 | O141 | − | + | + | − | − | + | 17 |

| 2180 | O141 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 1 |

| 2181 | O141 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 3 |

| 2183 | O141 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 17 |

| 820727 | O141 | + | − | − | − | − | − | 13 |

| 2156 | O141 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 17 |

| 2142 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 5 |

| 2200 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 8 |

| 2162 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 5 |

| 2141 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 6 |

| 2206 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 7 |

| 2228 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 6 |

| 750158 | O139 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 12 |

| 881284 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 9 |

| 911456 | O139 | − | − | − | + | − | + | 10 |

| 2203 | O138 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 1 |

| 750162 | O138 | + | + | − | − | − | + | 2 |

| 750324 | O138 | + | + | − | + | − | + | 2 |

| 750408 | O138 | + | + | − | + | − | + | 2 |

| 750421 | O138 | − | + | − | + | − | − | 2 |

| 760385 | O138 | − | − | − | − | − | + | 2 |

| 760386 | O138 | − | + | − | + | − | − | 2 |

| 831086 | O138 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 14 |

| 890652 | O138 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 2 |

| 2189 | O109 | + | + | − | − | − | − | 17 |

| 2159 | O21 | − | + | − | − | + | + | 1 |

| 2168 | O5 | − | − | − | + | − | − | 15 |

| 2170 | OXe | + | + | + | − | − | + | 1 |

| 2192 | OX | + | + | − | − | + | + | 1 |

| 2193 | OX | + | + | − | − | + | + | 1 |

| 2209 | OX | + | + | − | − | − | + | 17 |

| 2207 | OX | + | + | − | − | + | + | 17 |

All except two of the O139 Hungarian strains were from pigs with ED.

Detected by use of a gene probe.

Detected by use of a monoclonal antibody.

+, present; −, absent; +/−, equivocal result.

OX, not typeable with standard O antisera.

FIG. 1.

Genetic relationships of 43 ETs of porcine strains isolated from pigs with PWD or ED. The dendrogram was generated by average-linkage cluster analysis, using genetic distance matrix based on the numbers of allelic mismatches between ETs.

Among the four serogroup O157 strains evaluated, three had identical phenotypes, e.g., each carried sta and stb enterotoxin and f18 genes, while the other strain 802575, was positive for sta and lt genes and lacked the f18 gene (Table 1). Interestingly, strain 802575 belongs to clone ET18, which is not related (genetic distance, D = 0.580) to the ET that defines the other three O157 isolates namely ET11 (Fig. 1). The nine O141 isolates displayed similar toxin and fimbria patterns. Seven strains carried sta or stb, all except one carried f18, and one strain (strain 2155) was positive for lt and stb genes. However, this serogroup (O141) was associated with five distinct clones, ET1, ET3, ET11, ET13, and ET17, which were represented in three clusters, A, C, and D (Fig. 1). Eight of nine O139 strains reacted with the f18 gene probe, whereas none expressed the F18ac fimbria. Only one strain failed to react with the stx2 probe, and none were positive for enterotoxin genes. In contrast to O141, the O139 strains represented by ET5, ET6, ET7, ET8, ET9, and ET10 formed a tight cluster related at a D of 0.1, except for strain 750158 (ET12), which is related at a D of 0.45 (Fig. 1). Six of nine O138 strains were positive for the f18 gene. Six of nine, five of nine, and seven of nine isolates reacted with stx2, sta, and stb gene probes, respectively. With the exception of one isolate, strain 831086, the serogroup O138 strains comprised a tight cluster, cluster A, containing ET1 and ET2 that are related at a D of 0.05. Importantly, strain 831086 was negative for all virulence factors tested in reference to cluster A strains that carry sta, stb, stx2, and f18 genes (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Serogroups infrequently associated with PWD, namely, O109, O21, and O5, and serogroup OX were represented by three clonal types, ET1, ET15, and ET17. These clonal types were represented among the serogroups most commonly associated with ED and PWD. The majority of this group of isolates was positive for the heat-stable toxin genes; only one strain carried the heat-labile toxin gene, and six of eight were positive for the f18 gene (Fig. 1).

Enteric disease in the neonatal and preweaned pig is often associated with E. coli strains that express STa, STb, LT toxins, and K88 (F4), K99 (F5), 987P (F6), or F41 fimbria virulence factors. Recently, the identified adhesins F107 (F18ab) and 2134P (F18ac), as well as a Shiga toxin variant (Stx2v), have been associated with isolates from pigs with ED and PWD (2, 5, 8, 9, 11, 17, 18). The two adhesin factors F18ab and F18ac have been found most frequently associated with serogroups O138, O139, O141, O147, and O157 (19, 22).

Through the application of MLEE to the study of E. coli population genetics, Ochman et al. (21) have shown that animal E. coli strains of the same serotype can be represented in diverse genetic backgrounds. On the other hand, Whittam et al. (27) provided strong genetic evidence that E. coli O157:H7, the causative agent of hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome belongs to a pathogenic clone that occurs throughout North America. Furthermore, we have previously shown that the O157:H7 isolates are related at the serogroup level to the O157 serogroup of pigs but they are not closely related genetically (26).

The genetic diversity of E. coli strains isolated from pigs with PWD (overwhelmingly enterotoxigenic and 39% F4+) in Australia has been recently reported by Hampson et al. (7). Using MLEE, they found 57 different ETs among 79 isolates of serogroups O8, O138, O141, O149, and O157. Cluster analysis resulted in 14 subclusters at a D of 0.2 that showed that only a few isolates in the four main serogroups were closely related. It was surprising that the diversity of serogroup O138 was very high for these Australian isolates (7). Their data suggested that strains causing PWD represent a variety of E. coli strains that may carry virulence factors associated with disease of older pigs. However, they did not test for virulence factors other than K88 (F4).

In our study focusing on F18+ E. coli and virulence genes, we found 18 distinct ETs among the 43 isolates based upon genetic variation at 20 enzyme loci. There was a strong genetic homogeneity in serogroups O157 and O138, whereas the other serogroups evaluated were comprised of diverse ETs, with a D of >0.2 between them.

Aarestrup et al. (1) used ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiling to show how ED strains (O139, F18, and Stx2e) from different countries were related. Based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles, the Danish isolates were closely related and different from isolates from other countries (Switzerland, Hungary, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden), suggesting an association of Danish strains with the movement of animals between breeding and finishing facilities. In our study, most of the O139 strains from Hungary and the United States formed a relatively tight cluster (including seven clones), and had the most uniform virulence genes (f18 and stx2), consistent with the findings of the Danish study (1). Several of our ED and PWD strains were recently investigated for F18 and Stx phenotypes and showed patterns similar to the phenotypes of the Danish strains (19).

Bertschinger et al. (3) have shown that inheritance of susceptibility to intestinal colonization with F107 (F18ab) fimbriae appears to be a single recessive trait. It has also been shown that F18ab and F18ac most likely share the same receptors (19, 22). Pathogenic E. coli with these fimbriae would more likely be isolated from a select group of pigs and, theoretically, could represent a genetically more homogeneous group of strains. However, our data indicate the existence of a diverse population of f18+ E. coli isolates with similar serotypes associated with PWD and ED. In our study, only eight of the strains were neither phenotype F18ac positive nor f18 gene positive.

The strains selected for the present study represent a subset of strains from our earlier study (30). In the previous study, we tested 325 E. coli strains selected from the Reference Center that had been isolated from pigs diagnosed with PWD or ED in the United States and in Hungary by using MLEE as in the present study. We have shown that the serotypes associated with diarrhea (PWD) have very diverse genetic backgrounds even though the serotypes appear to be limited and that among the four major serogroups the fimbriae and toxins in general are not related to selected genotypes. Our earlier observations (30) concur with the data reported here, that the toxin and f18 fimbria genes of PWD strains occur in a variety of genetic backgrounds and suggest that such strains have converged by selection or recombination to these major phenotypes. In contrast, f18+ ED strains seem to be characterized by somewhat more genetic homogeneity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Hungarian Basic Science Fund OTKA T4758 and A312.

We are indebted to Michael Davis for serotyping, Kimberly Seebart for gene probe testing, Marie Wolfe for MLEE analysis, and Martha Tóth-Szekrényi for skilled technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup F M, Jorsal S E, Ahrens P, Jensen N E, Meyling A. Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli strains isolated from pigs with edema disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:20–24. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.20-24.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertschinger H U, Bachman M, Mettler C, Pospischil A, Schraner E M, Stamm M, Sydleer T, Wild P. Adhesive fimbriae produced in vitro by Escherichia coli O139:K12(B):H1 associated with enterotoxemia in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 1990;25:267–281. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertschinger H U, Stamm M, Vogeli P. Inheritance of resistance to oedema disease in the pig: experiments with an Escherichia coli expressing fimbriae 17. Vet Microbiol. 1993;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90117-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casey T A, Nagy B, Moon H W. Pathogenicity of porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli that do not express K88, K99, F41 or p987P adhesins. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:1488–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean-Nystrom E A, Casey T A, Schneider R A, Nagy B. A monoclonal antibody identifies 2134P fimbriae as adhesins on enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from postweaning pigs. Vet Microbiol. 1993;37:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90185-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunstein M, Hogness D S. Colony hybridization: a method for the isolation of cloned DNAs that contain a specific gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3961–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hampson D J, Woodward J M, Connaughton I D. Genetic analysis of porcine postweaning diarrhea. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:575–581. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imberechts H, DeGreve H, Schlicker C, Bouchet H, Pohl P, Charlier G, Bertschinger H U, Wild P, Vandekerckhove J, Van Damme J, Van Montagu M, Lintermans P. Characterization of F107 fimbriae of Escherichia coli 107/86, which causes edema disease in pigs, and nucleotide sequence of the F107 major fimbrial subunit gene, fedA. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1963–1971. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1963-1971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imberechts H, Bertschinger H U, Stamm M, Sydler T, Pohl P, DeGreve H, Hernalsteen J-P, Van Montagu M, Lintermans P. Prevalence of F107 fimbriae on Escherichia coli isolated from pigs with oedema disease or postweaning diarrhoea. Vet Microbiol. 1994;40:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imberechts H, Van Pelt N, DeGreve H, Lintermans P. Sequences related to the major subunit gene fedA of F107 fimbriae in porcine Escherichia coli strains that express adhesive fimbriae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennan R, Soderlind O, Conway P. Presence of F107, 2134P and AV24 fimbriae on strains of Escherichia coli isolated from Swedish piglets with diarrhoea. Vet Microbiol. 1995;43:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00093-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C H, Moseley S L, Moon H W, Whipp S C, Gyles C L, So M. Characterization of the gene encoding heat-stable toxin II and preliminary molecular epidemiological studies of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin II producers. Infect Immun. 1983;42:264–268. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.264-268.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund A. Serological, enterotoxin producing and biochemical properties of E. coli isolated from piglets with neonatal diarrhea in Norway. Acta Vet Scand. 1982;23:29–87. doi: 10.1186/BF03546824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques L R M, Peiris J S M, Cryz S J, O’Brien A D. Escherichia coli isolated from pigs with edema disease produce a variant of Shiga-like toxin II. FEMS Lett. 1987;44:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon H W, Kohler E M, Schneider R A, Whipp S C. Prevalence of pilus antigens, enterotoxin types, and enteropathogenicity among K88-negative enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli from neonatal pigs. Infect Immun. 1980;27:222–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.222-230.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris J A, Thorns C J, Boarer C, Wilson R A. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody to the K99 fimbrial adhesin produced by Escherichia coli enterotoxigenic for calves, lambs, and piglets. Res Vet Sci. 1985;39:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagy B, Casey T A, Moon H W. Phenotype and genotype of Escherichia coli isolated from pigs with postweaning diarrhea in Hungary. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:651–653. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.4.651-653.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagy B, Casey T A, Whipp S C, Moon H W. Susceptibility of porcine intestine to pilus-mediated adhesion by some isolates of piliated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli increases with age. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1285–1294. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1285-1294.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagy B, Whipp S C, Imberechts H, Bertschinger H U, Dean-Nystrom E A, Casey T A, Salajka E. Biological relationship between F18ab and F18ac fimbriae of enterotoxigenic and verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli from weaned pigs with oedema disease of diarrhoea. Microbiol Pathol. 1997;22:1–11. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newland J W, Neill R J. DNA probes for Shiga-like toxins I and II and for toxin-converting bacteriophages. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1292–1297. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.7.1292-1297.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochman H, Wilson R A, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Neonatal Diarrhea. Saskatoon, Canada: VIDO Publications, University of Saskatchewan; 1984. Genetic diversity within serotypes of Escherichia coli; pp. 202–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rippinger P, Bertschinger H U, Imberechts H, Nagy B, Sorg I, Stamm M, Wild P, Wittig W. Designations F18ab and F18ac for the fimbrial types F107, 2134-P and 8813 of E. coli isolated from porcine postweaning diarrhoea and from oedema disease. Vet Microbiol. 1995;45:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00141-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salajka E, Salajkova Z, Alexa P, Hornich M. Colonization factor different from K88, K99, F41, and 987P in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from postweaning diarrhea in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 1992;32:163–175. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selander R, Caugant D A, Ochman H, Musser K M, Gilmour M N, Whittam T S. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:873–884. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.5.873-884.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soderlind O, Möllby R. Enterotoxins, O-groups, and K88 antigen in Escherichia coli from neonatal piglets with and without diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1979;24:611–616. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.611-616.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittam T S, Wilson R A. Genetic relationships among pathogenic Escherichia coli of serogroup O157. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2467–2473. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2467-2473.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whittam T S, Wachsmuth I K, Wilson R A. Genetic evidence of clonal descent of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1988;6:1124–1133. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.6.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whittam T S, Wolfe M L, Wachsmuth I K, Orskov F, Orskov I, Wilson R A. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1619–1629. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1619-1629.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson R A, Francis D H. Fimbriae and enterotoxins associated with Escherichia coli serogroups isolated from pigs with colibacillosis. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson R A, Nagy B, Whittam T S. Proceedings of the 13th IPVS Congress, Bangkok, Thailand. 1994. Clonal analysis of weaned pig isolates of enterotoxigenic and verocytotoxigenic E. coli; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittig W, Prager R, Stamm M, Streckel W, Tschape H. Expression and plasmid transfer of genes coding for the fimbrial antigen F107 in porcine Escherichia coli strains. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1994;281:130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]