Abstract

Background:

People recently released from prison are at increased risk of preventable death; however, the impact of the current overdose epidemic on this population is unknown. We aimed to document the incidence and identify risk factors for fatal overdose after release from provincial prisons in British Columbia.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective, population-based, open cohort study of adults released from prisons in BC, using linked administrative data. Within a random 20% sample of the BC population, we linked provincial health and correctional records from 2010 to 2017 for people aged 23 years or older as of Jan. 1, 2015, who were released from provincial prisons at least once from 2015 to 2017. We identified exposures that occurred from 2010 to 2017 and deaths from 2015 to 2017. We calculated the piecewise incidence of overdose-related and all-cause deaths after release from prison. We used multivariable, mixed-effects Cox regression to identify predictors of all-cause death and death from overdose.

Results:

Among 6106 adults released from prison from 2015 to 2017 and followed in the community for a median of 1.6 (interquartile range 0.9–2.3) years, 154 (2.5%) died, 108 (1.8%) from overdose. The incidence of all-cause death was 16.1 (95% confidence interval [CI] 13.7–18.8) per 1000 person-years. The incidence of overdose deaths was 11.2 (95% CI 9.2–13.5) per 1000 person-years, but 38.8 (95% CI 3.2–22.6) in the first 2 weeks after release from prison. After adjustment for covariates, the hazard of overdose death was 4 times higher among those who had been dispensed opioids for pain.

Interpretation:

People released from prisons in BC are at markedly increased risk of overdose death. Overdose prevention must go beyond provision of opioid agonist treatment and naloxone on release to address systemic social and health inequities that increase the risk of premature death.

Overdose continues to be a serious public health issue in British Columbia that has lowered life expectancy in the province.1 Since the declaration of a public health emergency in 2016, more than 5000 people have died of overdose in BC, and nonfatal overdose events continue to rise. Irrespective of population overdose trends, people recently released from prison are at increased risk of death from overdose.2 A key causal mechanism is thought to be reduced drug tolerance, such that most (although not all)3,4 studies observe a spike in mortality rate immediately after release.2,5,6

To date, only 2 studies have explored deaths after release from prison in Canada. One study used data linkage to follow a cohort of 48 166 adults who were incarcerated in Ontario in 2000, for up to 12 years. The rate of overdose deaths in the first 2 weeks after release from prison was 56 times higher than in the age- and sex-matched general population; falling to 29 times higher in weeks 3–4 after release.7 A second study linked all overdose deaths in Ontario between 2006 and 2013 with provincial correctional records; 10% of overdose deaths in the province occurred within a year of release from prison, and 20% of these deaths occurred within 1 week of release.8 The impact of the current overdose epidemic on death after release from prisons in BC is unknown.

Evidence that people released from prison are at increased risk of overdose is insufficient to inform targeted prevention. Internationally, few studies of this phenomenon have been able to identify risk and protective factors, largely because of the limitations of available linked administrative data.6 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that authorities provide opioid agonist treatment in prison, and make both opioid agonist treatment and naloxone available on release, as cornerstones of prevention.5 However, these measures alone may be inadequate. Physical and mental health comorbidities may also contribute to the risk of fatal overdose, 9–11 and growing evidence suggests that people released from prison with co-occurring substance use disorder and mental illness — also known as dual diagnosis — are particularly at risk of poor health outcomes.12 More evidence on risk and protective factors is needed to inform targeted, evidence-based prevention.

We aimed to compare the risk of overdose-related and of nonoverdose deaths in different time periods after release from incarceration, and to identify individual and socioenvironmental characteristics associated with overdose-related deaths and all-cause deaths after release from incarceration.

Methods

Design

We conducted a retrospective, population-based, open cohort study of adults released from prisons in BC. The cohort was constructed from a random 20% sample of the BC population, linked with provincial health and correctional records. The BC Centre for Disease Control Provincial Overdose Cohort (http://www.bccdc.ca/our-services/programs/provincial-overdose-cohort) comprises linked, province-wide administrative data. A detailed description of the cohort is available elsewhere.13 We used data from 13 linked administrative data sources (Appendix 1, Supplementary Table S1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/3/E907/suppl/DC1). These administrative health data have been widely used for research purposes in BC and Canada.13,14 We measured exposures during an accrual period from Jan. 1, 2010, until Dec. 31, 2017, and measured outcomes during an observation period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2017.

Setting and participants

We drew our 20% random sample from the client roster of health insurance in BC, which is mandatory and therefore provides almost complete coverage of BC residents. Within this random sample, we selected all people who were aged 23 years or older on Jan. 1, 2015, and who had at least 1 record of release from a BC prison (remand or sentenced) between Jan. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2017. BC Corrections is responsible for 10 correctional centres throughout the province, holding around 2600 inmates on any given day. Inmates may be on remand (pretrial detention) or serving a sentence of up to 2 years, less a day.

Outcome

We identified deaths from 2015 to 2017 using linked administrative health data available in the BC Provincial Overdose Cohort. We defined overdose deaths as those identified by BC Vital Statistics as being caused by an opioid overdose (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] codes T40.0, T40.1, T40.2, T40.3, T40.4, T40.6), deaths identified by the BC Coroners Service as being caused by unintentional illicit drug toxicity or deaths from any cause that occurred within 24 hours of an overdose event as identified from linked ambulance, emergency department or hospital data (for details, see Appendix 1). We define nonoverdose deaths as all deaths not caused by overdose. All-cause deaths refer to deaths from any cause, including overdose.

Exposures

Our selection of exposures was informed by a review of the literature.6,15–17 Using linked administrative data, we identified exposures from Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2017, including age, sex, length of most recent incarceration, number of previous incarcerations, co-occurring substance use disorder and mental illness, physical comorbidity, dispensing of benzodiazepines and dispensing of opioids for the treatment of pain (for details, see Appendix 1).

From BC provincial correctional records, we identified the number of times participants had been released from prison from 2010 to 2014, and obtained all dates of incarceration and release from prison from 2015 to 2017. Using these data, we calculated the number of times each cohort member had been incarcerated, and calculated the duration in days of each episode of incarceration. Given evidence from previous research that the risk of death after release from prison is greater for those who have spent less time in custody,2,6 we modelled the association between duration of most recent incarceration (≤ 3, 4–15, 16–60, > 60 days) and death.

From hospital and outpatient records, we used ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to identify people with evidence of substance use disorder or mental illness, defined as having had 2 or more relevant outpatient visits within 1 year, or 1 relevant hospitalization record during the accrual period 2010–2017. We considered people with both a substance use disorder and mental illness during the accrual period to have a dual diagnosis.

We coded hospital records for chronic disease comorbidity using an adapted version of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.18 For each of 31 chronic disease groups, if we identified a disease, we set the index for this group as “1”; otherwise, we set the index as “0”. The sum of the indexes for the 31 groups forms the comorbidity index. For the analyses presented here, we removed 4 disease groups, reflecting substance use and mental illness, to avoid collinearity with the dual diagnosis variable. We dichotomized the adapted index score (0, ≥ 1).

We identified dispensation of opioids for pain and dispensation of benzodiazepines during the accrual period using provincial pharmaceutical data (PharmaNet), which contain all records of dispensed prescription medications in community pharmacies in the province. We excluded opioids used for treatment of opioid use disorders.

Statistical analyses

Each observation period commenced on the date of a release from custody during the 2015–2017 period, and was censored at reincarceration, at death or on Dec. 31, 2017, whichever came first. Consequently, each person could have multiple observations. We calculated the rate of all-cause and overdose-related deaths per 1000 person-years, expressed as the number of deaths in the community divided by person-years at risk in the community, multiplied by 1000. We calculated mortality rates for the full sample, and according to characteristics at the time of each release. We calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) for mortality rates using the exact method (POIS.EXACT in R) under the assumption of a Poisson distribution.

We calculated the piecewise incidence rate of overdose-related and nonoverdose deaths during each 2-week period in the first 8 weeks after release from prison, and for all community follow-up, using all releases during follow-up. To identify characteristics associated with overdose-related and all-cause death, we constructed mixed-effects Cox models (COXME in R), adjusting for the correlation between an individual’s multiple releases, to calculate unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding 95% CIs. This approach to data analysis permitted the value of all covariates (except for sex) to differ for each release. We conducted all analyses using the R statistical computing environment (version 3.5.2).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this project was not required as it was conducted as part of BC Centre for Disease Control Provincial Overdose Cohort’s overdose surveillance and advanced analytics mandate.

Results

The sample included 6106 people released from a BC prison at least once from 2015 to 2017. Of these, 108 (1.8%) people died from overdose-related causes, and 154 (2.5%) died from any cause (including overdose), during 9633 person-years of community follow-up. The median duration of community follow-up per person was 1.6 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.9–2.3) years, and the median duration per episode of follow-up was 0.3 (IQR 0.1–1.0) years. During the 3-year follow-up period, the number of people with 1, 2, 3 and more than 3 episodes of incarceration were 3310 (54.2%), 1121 (18.4%), 974 (16.0%) and 701 (11.5%), respectively.

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of people who did and did not die from overdose-related causes, and from any cause, during community follow-up. Compared with people who did not die from overdose-related causes, those who died from overdose-related causes were significantly more likely to have been incarcerated multiple times, to have a history of mental illness or dual diagnosis, to have a history of physical comorbidities, and to have been dispensed benzodiazepines or dispensed opioids for pain. The pattern was similar for all-cause death.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the cohort at first release from custody, stratified by mortality status during the 3-year follow-up period

| Variable | No. (%) of participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Overdose-related death | All-cause death | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| No n = 5998 |

Yes n = 108 |

p value* | No n = 5952 |

Yes n = 154 |

p value* | |

| Age group, yr | 0.985 | 0.129 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 18–34 | 3132 (52.2) | 56 (51.9) | 3116 (52.4) | 72 (46.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 35–44 | 1512 (25.2) | 28 (25.9) | 1503 (25.3) | 37 (24.0) | ||

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 45 | 1354 (22.6) | 24 (22.2) | 1333 (22.4) | 45 (29.2) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.334 | 0.717 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Male | 5241 (87.4) | 91 (84.3) | 5199 (87.3) | 133 (86.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 757 (12.6) | 17 (15.7) | 753 (12.7) | 21 (13.6) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Length of most recent incarceration, d | 0.331 | 0.557 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 3 | 1594 (26.6) | 37 (34.3) | 1583 (26.6) | 48 (31.2) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 4–15 | 1665 (27.8) | 28 (25.9) | 1653 (27.8) | 40 (26.0) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 16–60 | 1251 (20.9) | 21 (19.4) | 1239 (20.8) | 33 (21.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| > 60 | 1488 (24.8) | 22 (20.4) | 1477 (24.8) | 33 (21.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| No. of previous incarcerations | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 1 | 3428 (57.2) | 40 (37.0) | 3413 (57.3) | 55 (35.7) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 2–3 | 1224 (20.4) | 24 (22.2) | 1218 (20.5) | 30 (19.5) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 4–7 | 950 (15.8) | 31 (28.7) | 935 (15.7) | 46 (29.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 8 | 396 (6.6) | 13 (12.0) | 386 (6.5) | 23 (14.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| SUD and mental illness | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| None | 3225 (53.8) | 25 (23.1) | 3212 (54.0) | 38 (24.7) | ||

|

| ||||||

| SUD | 696 (11.6) | 15 (13.9) | 688 (11.6) | 23 (14.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mental illness | 702 (11.7) | 12 (11.1) | 696 (11.7) | 18 (11.7) | ||

|

| ||||||

| SUD and mental illness | 1375 (22.9) | 56 (51.9) | 1356 (22.8) | 75 (48.7) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidity index | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 5526 (92.1) | 84 (77.8) | 5497 (92.4) | 113 (73.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 1 | 472 (7.9) | 24 (22.2) | 455 (7.6) | 41 (26.6) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Dispensed benzodiazepines | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 4528 (75.5) | 49 (45.4) | 4503 (75.7) | 74 (48.1) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 1470 (24.5) | 59 (54.6) | 1449 (24.3) | 80 (51.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Dispensed opioids for pain | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 3136 (52.3) | 14 (13.0) | 3129 (52.6) | 21 (13.6) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 2862 (47.7) | 94 (87.0) | 2823 (47.4) | 133 (86.4) | ||

Note: SUD = substance use disorder.

p values derived from χ2 tests.

Tables 2 and 3 show the incidence, and the unadjusted and adjusted HRs of overdose-related and all-cause death, according to characteristics at release. During community follow-up, the incidence of overdose-related death was 11.2 (95% CI 9.2–13.5) per 1000 person-years. In the unadjusted models, the hazard of overdose-related death was higher among people who had been incarcerated 4 or more times, those with a history of substance use disorder, mental illness or dual diagnosis, those with a history of physical comorbidity, and those who had been dispensed benzodiazepines or dispensed opioids for pain. In the fully adjusted model, the hazard of overdose-related death was 4 times higher among those who had been dispensed opioids for pain.

Table 2:

Incidence and hazard of overdose-related death after release from prison, according to characteristics at release

| Variable | Incidence per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 11.2 (9.2–13.5) | – | – |

| Age group, yr | |||

| 18–34 | 11.2 (8.4–14.6) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 35–44 | 11.7 (7.8–16.7) | 1.06 (0.67–1.66) | 0.85 (0.54–1.34) |

| ≥ 45 | 10.8 (6.9–16.0) | 1.04 (0.65–1.66) | 0.83 (0.51–1.35) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10.9 (8.7–13.3) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 13.6 (7.9–21.8) | 0.76 (0.45–1.28) | 0.98 (0.57–1.68) |

| Length of most recent incarceration, d | |||

| ≤ 3 | 12.1 (8.1–17.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 4–15 | 8.4 (5.4–12.7) | 0.67 (0.38–1.16) | 0.60 (0.34–1.04) |

| 16–60 | 14.0 (9.5–19.9) | 1.03 (0.62–1.72) | 0.80 (0.48–1.34) |

| > 60 | 10.9 (7.1–15.9) | 0.83 (0.48–1.41) | 0.74 (0.43–1.26) |

| No. of previous incarcerations | |||

| 1 | 5.8 (3.6–8.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2–3 | 10.1 (6.7–14.7) | 1.71 (0.97–3.01) | 1.28 (0.72–2.28) |

| 4–7 | 15.7 (10.8–22.1) | 2.48 (1.43–4.30) | 1.59 (0.90–2.82) |

| ≥ 8 | 21.4 (14.1–31.1) | 3.00 (1.67–5.39) | 1.59 (0.86–2.95) |

| SUD and mental illness | |||

| None | 4.8 (3.1–7.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| SUD | 13.5 (7.6–22.3) | 2.74 (1.46–5.16) | 1.26 (0.64–2.45) |

| Mental illness | 10.8 (5.6–18.9) | 2.19 (1.10–4.36) | 1.34 (0.66–2.72) |

| SUD and mental illness | 25.0 (18.9–32.5) | 4.73 (2.94–7.62) | 1.69 (0.97–2.97) |

| Comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 9.5 (7.6–11.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≥ 1 | 31.1 (19.9–46.3) | 3.10 (1.97–4.88) | 1.61 (0.99–2.61) |

| Dispensed benzodiazepines | |||

| No | 6.8 (5.0–9.0) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 24.5 (18.6–31.6) | 3.31 (2.27–4.84) | 1.41 (0.91–2.18) |

| Dispensed opioids for pain | |||

| No | 2.8 (1.5–4.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 20.3 (16.4–24.8) | 6.77 (3.86–11.89) | 4.01 (2.14–7.52) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, Ref. = reference, SUD = substance use disorder.

Adjusted for all other variables in this table.

Table 3:

Incidence and hazard of all-cause death after release from prison, according to characteristics at release

| Variable | Incidence per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 16.1 (13.7–18.8) | – | – |

| Age group, yr | |||

| 18–34 | 14.4 (11.3–18.2) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 35–44 | 15.3 (10.8–21.0) | 1.10 (0.74–1.63) | 0.89 (0.59–1.33) |

| ≥ 45 | 20.6 (15.1–27.5) | 1.60 (1.11–2.30) | 1.23 (0.84–1.82) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 16.0 (13.4–18.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 16.8 (10.4–25.7) | 0.94 (0.59–1.49) | 1.14 (0.70–1.86) |

| Length of most recent incarceration, d | |||

| ≤ 3 | 16.9 (12.0–23.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 4–15 | 12.9 (9.0–17.9) | 0.74 (0.46–1.16) | 0.64 (0.40–1.03) |

| 16–60 | 19.9 (14.5–26.7) | 1.13 (0.74–1.72) | 0.85 (0.55–1.31) |

| > 60 | 15.5 (10.9–21.3) | 0.87 (0.55–1.36) | 0.74 (0.47–1.17) |

| No. of previous incarcerations | |||

| 1 | 8.3 (5.6–11.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2–3 | 15.0 (10.7–20.4) | 1.86 (1.16–2.97) | 1.43 (0.88–2.30) |

| 4–7 | 21.9 (16.0–29.2) | 2.55 (1.60–4.06) | 1.68 (1.04–2.73) |

| ≥ 8 | 30.9 (22.0–42.2) | 3.32 (2.03–5.43) | 1.83 (1.09–3.08) |

| SUD and mental illness | |||

| None | 7.5 (5.4–10.3) | Ref. | Ref. |

| SUD | 20.8 (13.2–31.2) | 2.66 (1.61–4.42) | 1.20 (0.70–2.07) |

| Mental illness | 16.3 (9.6–25.7) | 2.01 (1.15–3.52) | 1.21 (0.67–2.16) |

| SUD and mental illness | 33.5 (26.3–42.0) | 4.03 (2.73–5.94) | 1.47 (0.93–2.35) |

| Comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 12.9 (10.6–15.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≥ 1 | 53.2 (38.2–72.1) | 3.87 (2.69–5.57) | 2.03 (1.37–3.02) |

| Dispensed benzodiazepines | |||

| No | 10.4 (8.2–13.0) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 33.2 (26.3–41.3) | 3.00 (2.19–4.11) | 1.26 (0.87–1.82) |

| Dispensed opioids for pain | |||

| No | 4.4 (2.8–6.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 28.7 (24.0–34.0) | 6.07 (3.89–9.48) | 3.67 (2.22–6.07) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, Ref. = reference, SUD = substance use disorder.

Adjusted for all other variables in this table.

During community follow-up, the incidence of all-cause death was 16.1 (95% CI 13.7–18.8) per 1000 person-years (Table 3). In the unadjusted models, the hazard of all-cause death was higher among people who were aged 45 years or older, those who had been incarcerated 2 or more times, those with a history of substance use disorder, mental illness or dual diagnosis, those with a history of physical comorbidities, and those who had been dispensed benzodiazepines or dispensed opioids for pain. In the fully adjusted model, the hazard of all-cause death was greater among those with a history of 4 or more incarcerations, those with physical comorbidities and those who had been dispensed opioids for pain.

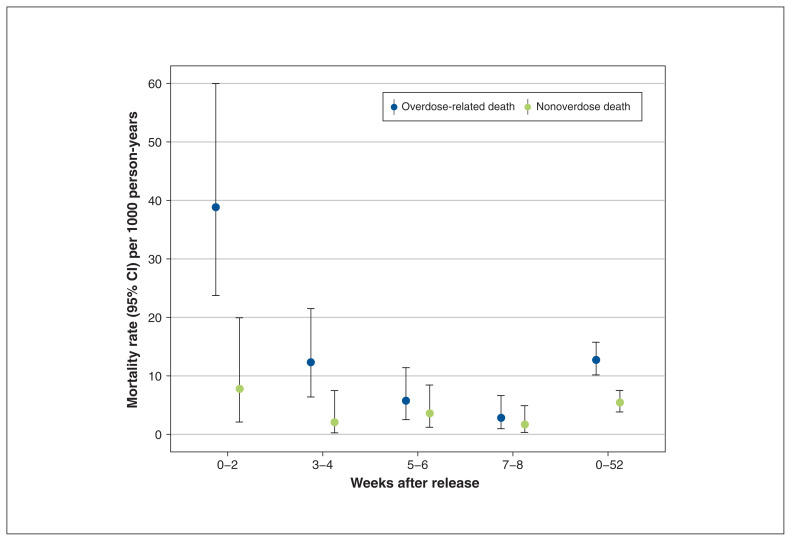

Figure 1 shows the piecewise incidence of overdose-related and nonoverdose death after release from incarceration. The incidence of overdose-related death was markedly elevated in the first 2 weeks after release (incidence rate 38.8, 95% CI 23.7–59.9, per 1000 person-years). The incidence of nonoverdose death was also elevated in the first 2 weeks after release, although not to the same extent (incidence rate 7.8, 95% CI 2.1–19.9).

Figure 1:

Piecewise incidence of overdose-related and nonoverdose deaths according to time since release from prison. Note: CI = confidence interval. Data used to construct Figure 1 are provided in Appendix 1, Supplementary Table S2.

Interpretation

In a large, representative sample of people released from prisons in BC, we found that 70% of observed deaths were related to overdose. The incidence of overdose-related death was markedly elevated in the first 2 weeks after release from prison and, after adjustment for covariates, the risk of fatal overdose was 4 times higher among people dispensed opioids for pain.

In the context of an overdose epidemic that is disproportionately affecting people released from prison, there is a clear and pressing need to implement evidence-based overdose prevention efforts at scale. BC provides opioid agonist treatment in all of its prisons and, more recently, has made naloxone widely available on release.19 Although these efforts are commendable and in line with international evidence, 5 our findings show that they have not been sufficient to stem the tide of overdose deaths in this highly vulnerable segment of the population. The recent transition of prison health care in BC from the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General to the Ministry of Health is consistent with WHO recommendations5 and may have facilitated better continuity of care, potentially reducing overdoses after release from custody. However, this hypothesis requires independent evaluation.20

Complex morbidity and disadvantage are normative among people who experience incarceration.15 In our study, we found that these co-occurring health and social problems were associated with risk of overdose-related and all-cause death. In addition to opioid agonist treatment and naloxone, enhanced efforts to prevent untimely deaths after release from prison should consider targeting these co-occurring risk factors. People with a history of multiple incarcerations were at an increased risk of both overdose-related death and all-cause death. Although this association was attenuated after adjustment for covariates, it remained a significant predictor of all-cause death, suggesting that efforts to minimize the use of incarceration through prevention and diversion may both be cost-effective and help prevent untimely deaths.

Even after adjusting for covariates, we found that people who had been prescribed opioids for pain were at markedly increased risk of overdose-related and all-cause death. There is a high prevalence of noncancer chronic pain among both people in prison21 and those receiving opioid agonist treatment; 22 opioid analgesics may be an appropriate treatment for these people. However, given our unsurprising finding that dispensing of opioids for pain was independently associated with a more than fourfold increase in risk of overdose-related death after release from prison, it appears that efforts to improve chronic pain management,23 and to enhance harm reduction measures, are warranted to ensure that medications intended to treat chronic pain do not result in preventable deaths in this medically complex population.

We found that co-occurring physical and mental health comorbidities increased the risk of both overdose-related and all-cause death. Again, after adjustment for covariates, this association attenuated to the null for overdose death, but physical comorbidity remained a significant predictor of all-cause death. Although the burden of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis) in prisons is now well recognized,24 less attention has been paid to the high rates of noncommunicable disease (NCD) in these settings.25 In addition to their direct contribution to death in people released from prison, certain NCDs, including those that result in hepatic or lung dysfunction, may increase the risk of overdose.26 As prison populations in Canada and elsewhere age,27 the importance of providing coordinated and continuous treatment for NCDs in people who experience incarceration will only increase.

Consistent with evidence that people with a dual diagnosis of substance use disorder and mental illness are at increased risk of injury after release from prison,12 we found that these people were more than 4 times more likely than those with neither disorder to die of overdose or any cause. These associations attenuated to the null in adjusted models; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that their effect was mediated by covariates. Future studies using prospective data linkage may have greater capacity to tease out the causal pathways between physical and mental health comorbidity, and death after release from prison.

Consistent with previous studies,2 we observed a spike in the incidence of overdose-related death in the first 2 weeks after release from prison, highlighting the importance of effective prevention in this high-risk period. However, in our study, most overdose deaths occurred more than 2 weeks after release, underscoring the importance of maintaining preventive efforts after this acute period. We also observed a modest spike in nonoverdose deaths in the 2 weeks after release from prison, suggesting that efforts to prevent untimely deaths after release from prison should not be restricted to overdose prevention.

Limitations

This study used linked health, correctional and mortality records to examine overdose death after release from prison. Key strengths include the population sampling frame, and use of linked health and correctional records to identify exposures. The study had six notable limitations. First, despite the large sample in our study, we observed a relatively small number of events, reducing the precision of our estimates. Future studies may benefit from longer accrual and follow-up periods, using full population samples rather than random samples from the population. Second, our study did not include people younger than 23 years on Jan. 1, 2015, among whom the elevation in risk of death after release from prison appears to be the greatest.28 Third, administrative data may underestimate some exposures of interest (e.g., substance use disorder, mental illness), which would have attenuated observed associations. Fourth, our accrual period began in 2010, such that we were unable to detect exposures before this date (e.g., incarceration, mental disorder). Again, this would attenuate associations. Fifth, although provincial health insurance records cover more than 95% of the BC population, we cannot exclude the possibility of modest sampling bias. Sixth, we were unable to identify transfers to federal prison, and as such, overestimated time at risk in the community, thereby underestimating the incidence of death in the community. Future studies that combine provincial and federal correctional records would provide a more complete picture of the epidemiology of overdose among people who experience incarceration in Canada.

Conclusion

People recently released from prisons in BC are at markedly increased risk of preventable death, mainly from overdose. As such, people transitioning from prison to the community should be a key target population for overdose prevention efforts. To be maximally effective, these efforts must go beyond provision of opioid agonist treatment and naloxone on release, to consider physical and mental health comorbidities, and psychosocial disadvantage. Effective overdose prevention for people who experience incarceration is critical to stemming the tide of overdose deaths in BC, and to mitigating the profound health inequalities experienced by this marginalized population.

Appendix

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Stuart Kinner, Amanda Slaunwhite and Wenqi Gan contributed to the conception and design of the work. Wenqi Gan was responsible for data management, analysis and interpretation. Stuart Kinner wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Stuart Kinner receives salary support from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT1078168).

Data sharing: The data used in this paper come from the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) Provincial Overdose Cohort. Access to the data is strictly regulated, in accordance with the provisions of the Public Health Act. Individuals interested in accessing the data should contact Dr. Amanda Slaunwhite (amanda.slaunwhite@bccdc.ca).

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/3/E907/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Romeo R, Knapp M, Scott S. Economic cost of severe antisocial behaviour in children — and who pays it. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:547–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrall ELC, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105:1545–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaulding AC, Sharma A, Messina LC, et al. A comparison of liver disease mortality with HIV and overdose mortality among Georgia prisoners and releasees: a 2-decade cohort study of prisoners incarcerated in 1991. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e51–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsyth SJ, Alati R, Ober C, et al. Striking subgroup differences in substance-related mortality after release from prison. Addiction. 2014;109:1676–83. doi: 10.1111/add.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preventing overdose deaths in the criminal justice system. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinner SA, Forsyth S, Williams GM. Systematic review of record linkage studies of mortality in ex-prisoners: Why (good) methods matter. Addiction. 2013;108:38–49. doi: 10.1111/add.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, Wobeser W, et al. Mortality over 12 years of follow-up in people admitted to provincial custody in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E153–61. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groot E, Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, et al. Drug toxicity deaths after release from incarceration in Ontario, 2006–2013: review of coroner’s cases. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariminia A, Law MG, Butler TG, et al. Factors associated with mortality in a cohort of Australian prisoners. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:417–28. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsyth SJ, Carroll M, Lennox N, et al. Incidence and risk factors for mortality after release from prison in Australia: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2018;113:937–45. doi: 10.1111/add.14106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spittal MJ, Forsyth S, Borschmann R, et al. Modifiable risk factors for external cause mortality after release from prison: a nested case-control study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28:224–33. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young JT, Heffernan E, Borschmann R, et al. Dual diagnosis and injury in adults recently released from prison: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e237–48. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDougall L, Smolina K, Otterstatter M, et al. Development and characteristics of the Provincial Overdose Cohort in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pencarrick Hertzman C, Meagher N, McGrail KM. Privacy by design at population data BC: a case study describing the technical, administrative, and physical controls for privacy-sensitive secondary use of personal information for research in the public interest. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:25–8. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinner SA, Young JT. Understanding and improving the health of people who experience incarceration: an overview and synthesis. Epidemiol Rev. 2018;40:4–11. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinner SA, Binswanger IA. Mortality after release from prison. In: Bruinsma GJN, Weisburd DL, editors. Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. Washington (DC): Springer; 2014. pp. 3157–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox AD, Moore A, Kinner SA, et al. Deaths in custody and following release. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2019;41:45–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearce LA, Mathany L, Rothon D, et al. An evaluation of Take Home Naloxone program implementation in British Columbian correctional facilities. Int J Prison Health. 2019;15:46–57. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-12-2017-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLeod KE, Butler A, Young J, et al. Global prison healthcare governance and health equity: a critical lack of evidence. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:303–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croft M, Mayhew R. Prevalence of chronic noncancer pain in a UK prison environment. Br J Pain. 2015;9:96–108. doi: 10.1177/2049463714540895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. 2003;289:2370–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leece P, Shantharam Y, Hassam S, et al. Improving opioid guide-line adherence: evaluation of a multifaceted, theory-informed pilot intervention for family physicians. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e032167. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolan K, Wirtz A, Moazen B, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016;388:1089–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379:1975–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner-Smith M, Darke S, Lynskey M, et al. Heroin overdose: causes and consequences. Addiction. 2001;96:1113–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kouyoumdjian FG, Andreev EM, Borschmann R, et al. Do people who experience in-carceration age more quickly? Exploratory analyses using retrospective cohort data on mortality from Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dooren K, Kinner SA, Forsyth S. Risk of death for young ex-prisoners in the year following release from adult prison. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37:377–82. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.