Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily routines and family functioning, led to closing schools, and dramatically limited social interactions worldwide. Measuring its impact on mental health of vulnerable children and adolescents is crucial.

Methods

The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT – www.coh-fit.com) is an on-line anonymous survey, available in 30 languages, involving >230 investigators from 49 countries supported by national/international professional associations. COH-FIT has thee waves (until the pandemic is declared over by the WHO, and 6–18 months plus 24–36 months after its end). In addition to adults, COH-FIT also includes adolescents (age 14–17 years), and children (age 6–13 years), recruited via non-probability/snowball and representative sampling and assessed via self-rating and parental rating. Non-modifiable/modifiable risk factors/treatment targets to inform prevention/intervention programs to promote health and prevent mental and physical illness in children and adolescents will be generated by COH-FIT. Co-primary outcomes are changes in well-being (WHO-5) and a composite psychopathology P-Score. Multiple behavioral, family, coping strategy and service utilization factors are also assessed, including functioning and quality of life.

Results

Up to June 2021, over 13,000 children and adolescents from 59 countries have participated in the COH-FIT project, with representative samples from eleven countries.

Limitations

Cross-sectional and anonymous design.

Conclusions

Evidence generated by COH-FIT will provide an international estimate of the COVID-19 effect on children's, adolescents’ and families’, mental and physical health, well-being, functioning and quality of life, informing the formulation of present and future evidence-based interventions and policies to minimize adverse effects of the present and future pandemics on youth.

Keywords: Covid-19, Pandemic, Mental health, Physical health, Resilience, Children, Adolescents

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has infected over 101 million people around the world, caused over 2,180,000 deaths by January 28th, 2021 (Johns Hopkins University 2020). Beyond pulmonary complications and deaths, the pandemic has also impacted mental and physical health of the general population, and especially of certain subgroups at risk (Chi et al., 2020; Salazar de et al., 2020). Moreover, changes in healthcare delivery have occurred worldwide (Kinoshita et al., 2020). While children and adolescents are at a lower risk of contracting COVID-19, they are nevertheless impacted by indirect consequences of the pandemic and related restrictions. A recent systematic review which pooled data from over 50,000 children and adolescents across 63 studies, showed that loneliness and disease containment measures increased the risk of depression short-term, and up to 9 years after containment for other-than-COVID-19 reasons in previously healthy children and adolescents (Loades et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). One further evidence synthesis effort focusing specifically on studies after the COVID-19 breakout has shown that the pandemic affects children and adolescents differently (Marques de Miranda et al., 2020). Rates of anxiety and relevant depressive symptoms increased from age 7–17 (Marques de Miranda et al., 2020). The largest meta-analysis published to date on the prevalence of mental health concerns during the pandemic has shown that the anxiety prevalence among children and adolescents is as high as 19% (95% confidence interval 14% to 25%, data from 22 studies), and depression as high as 15% (95%CI 10% to 21%, data from 16 studies) (Dragioti et al., 2021). Besides children and adolescents of the general population, those suffering from mental disorders are in need of special adjustment of usual care during the pandemic (Cortese et al., 2020). Furthermore, evidence suggests that children with physical conditions, such as cancer, are suffering from lower quality of care due to health system changes during the pandemic (Vasquez et al., 2020). Families in general, and in particular those with children or adolescents affected by a mental disorder, are struggling to cope with the pandemic-related restrictions, and in particular in managing homeschooling of their children while working from home at the same time (Becker et al., 2020). Beyond the general population and service users, health services require adaptation to the current pandemic. For instance, telemedicine and use of technology increased worldwide, and are needed to cope with uneasiness of access to care, which is due both to services shifting resources to COVID-19 related care, and service users avoiding clinical contact to minimize infection risk (Davis et al., 2020).

In this context, the Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT -www.coh-fit.com) project was launched in April 26th, 2020, aiming to measure the COVID-19 pandemic impact on well-being, mental and physical health, functioning and access to care of the general population. Specifically, COH-FIT-Children and Adolescents (COH-FIT-C&A), targets children, adolescents, their parents and families to identify subgroups of children and adolescents at increased risk of struggling during the pandemic, in order to ascertain potential modifiable risk factors to tackle and protective factors to empower, and to assess, which coping strategies are most important to successfully deal with infection spread and related restrictions. Aiming to generate possibilities to pool or, at least, compare data across large studies, COH-FIT employs the same time frame used in the coronavirus health and impact survey (CRISIS) (Nikolaidis et al., 2020), with both projects asking about symptoms during the last two weeks at the moment of survey participation, and the last two weeks before the pandemic. Also, both survey projects collect data on youth via both parental rating and self-report questions. While CRISIS uses more parental report, COH-FIT includes broader pediatric self-report.

Given the unprecedented disruption of daily routine and already demonstrated or highly suspected negative impact of COVID-19 on the general population, including adults, parents, children and adolescents, as well as family systems, both in the short and in the long-term, our hypothesis is that the pandemic is adversely affecting children and adolescents regarding a variety of relevant outcomes, ranging from mental to physical health, well-being and functioning. We further hypothesize that such negative impact differs across various pediatric and family subgroups in terms of type and number of affected domains, severity and chronicity of the impairment, as well as support structures, care and coping mechanisms available/utilized. For instance, depressive symptoms might have increased in adolescents, yet alcohol or other substance abuse use might have decreased. Identifying specific risk and protective factors, as well as actionable items to minimize the pandemic's impact across specific subgroup of children and adolescents will inform tailored intervention and prevention opportunities. For instance, evidence that youth affected by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism or mental retardation are those suffering the most from the pandemic-related restrictions could provide guidance to governments, which might consider modification of the type or implementation of restrictions for these fragile populations and their families.

We also hypothesize that the self-perceived and parentally rated quality of life and functioning of youth will substantially differ, providing evidence in support of decisions on whether parental or self-rated measures should be selected for screening campaigns to identify the most vulnerable or affected subgroups during infection times. For instance, children or adolescents might not disclose the severity of their distress to their parents, especially if they are distressed too, who might therefore not be fully aware of the extent to which the pandemic is affecting their daughters’ and sons’ mental and physical health.

Overall, COH-FIT aims to comprehensively capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being, mental health, physical health, family, personal and social functioning of children, adolescents, and their families. The expectation is that the amount of collected data will inform who the most fragile groups are among children and adolescents, and what might be the actionable items to improve their health and functioning during present and future infection times.

In this article, the structure of COH-FIT-C&A is described, consisting of COH-FIT for adolescents (COH-FIT-AD) and for children (COH-FIT-C).

2. COH-FIT development and design

COH-FIT follows a pre-planned and published protocol (Identifier: NCT04383470). The project was initiated on April 1st, 2020, by the two co-Principal Investigators (MS, CUC). Over few weeks, a large number of world-class researchers have joined the project, reaching to date over 220 researchers from all six continents (http://www.coh-fit.com/Collaborators). COH-FIT is endorsed and supported by the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Prevention of Mental Disorders and Mental Health Promotion Thematic Working Group, the European Psychiatric Association, the World Association of Social Psychiatry and the Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health among many other important international and national scientific associations, non-profit organizations, universities and institutions (http://www.coh-fit.com/partners). Website costs, and representative sample collection are entirely covered by non-profit foundations and researchers’ institutions, and no funding by the industry of any kind has supported COH-FIT.

COH-FIT survey data are collected, stored and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software tool hosted at the Department of Neurosciences of the University of Padua, Italy, as well at Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (Harris et al., 2009).

COH-FIT is an on-line anonymous survey (www.coh-fit.com) for adults as well as, after guardian e-consent, for adolescents (14–17years) and children (6–13years). Participants can respond via a laptop, tablet, or smartphone. COH-FIT has a multi-wave structure. Wave 1 began on April 27th, 2020 and will continue until the pandemic will be declared over by the WHO. Waves 2 and 3 will last 6–18 months and from 24 to 36 months onwards after the pandemic's official end. While it is a cross-sectional survey at the respondent level, COH-FIT is a longitudinal survey at the population level with continuous data collection during each wave, capturing responses at different infection/mortality rates, restrictions, etc.

Data and outcomes are deliberately broad to provide a fine-grained and transdiagnostic physical, emotional, behavioral and interactional picture of the pandemic's impact on children, adolescents, and families, ranging from well-being, mental health, physical health to health-service access/utilization, treatment adherence, interpersonal and family functioning, school and work performance, financial loss, emotions, sleep, etc. Moreover, instead of assessing a limited group of symptoms with validated instruments including many questions, we selected 1–2 items from validated questionnaires. For instance, instead of using the nine questions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-915 to measure depressive symptoms, COH-FIT only uses two items (one for depressed mood, one for loss of interest). With this approach, COH-FIT aims to measure a wide transdiagnostic symptomatic profile with a limited number of questions. Specifically, COH-FIT items were extracted from PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006), Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al., 2015), Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (BOCS) (Susanne et al., 2014), Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale,19 Prodromal Questionnaire-16 (Ising et al., 2012).

COH-FIT has been translated into 30 languages (https://www.coh-fit.com//take-survey/).

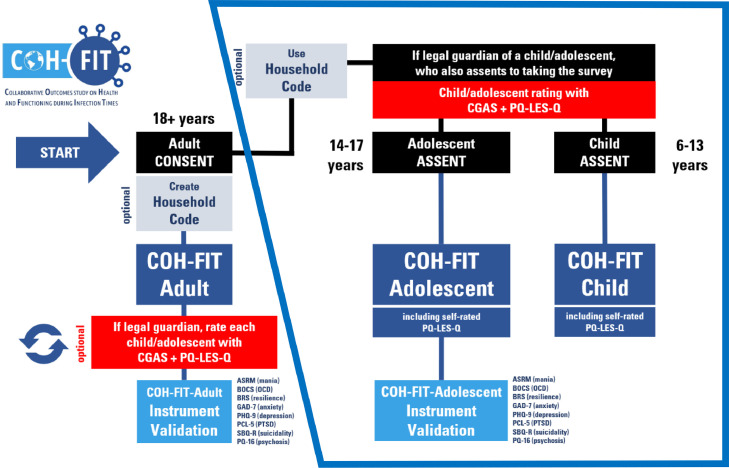

Two different instruments compose COH-FIT-AD and COH-FIT-C, (Fig. 1 ). For both COH-FIT-AD and COH-FIT-C, parental consent is needed, and parental rating on functioning and quality of life is collected. After e-consent, parents/ guardians are asked to provide information on age, gender, and presence of physical/mental comorbidities of their children/adolescent. Then, parents/guardians are asked to rate the child's/adolescent's functioning on the anchored children's global assessment scale (CGAS) (Shaffer et al., 1983), and quality of life with the pediatric quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q) (Endicott et al., 2006). After parental/guardian rating, the adolescent takes the COH-FIT-AD survey, which is identical to the adult survey (COH-FIT-A) without a question regarding sexual activity. The child takes the COH-FIT-C survey, which has abbreviated/condensed content and simplified language.

Fig. 1.

COH-FIT-Adolescents and COH-FIT-Children survey flow.

Legend. ASRM, Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (Altman et al., 1997); BOCS, Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Bejerot et al., 2014); BRS, Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008); CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale (Shaffer et al., 1983); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (Spitzer et al., 2006); OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-517; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (Kroenke et al., 2001); PQ-LES-Q, Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Endicott et al., 2006); PQ-16, Prodromal Questionnaire-1620; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; SBQ-R, Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (Osman et al., 2001).

Given that children/adolescents share the same household with other individuals who may be interested in participating in the survey, respondents can generate, input and store a non-identifiable 10-character password (“household code”) that can be shared with and used by all individuals living in the same household, allowing household-based analyses.

Both surveys (COH-FIT-AD/C) have an adaptive format, in that they prompt/do not prompt the respondent with additional questions depending on previous answers. Moreover, if participants want to interrupt the survey and come back to it later on, a “Return code” is generated. This code is sent automatically to an individually imputed e-mail address of preference (which is not stored in the database), requesting to rejoin and complete the saved questionnaire.

Both non-representative sampling via snowball/non-probabilistic approach and representative samples purchased via polling institutes are being collected.

2.1. COH-FIT-Children

Children aged 6–13 years can take the COH-FIT-C, which has a simpler/developmentally appropriate language, and is shorter covering only a subgroup of relevant items.

The two COH-FIT co-primary outcomes are well-being (modified version of World Health Organization – 5 (WHO-5) (Topp et al., 2015) with each item scored on a VAS 0–100 scale, rather than a six-point Likert-scale), and a composite psychopathology score, C-P-Score, composed of the following domains: anxiety, depression, post-traumatic, stress, sleep, concentration. Items composing the C-P-Score have been selected a-priori based on clinical judgement.

Key secondary outcomes are the C-P-Extended Score composed of C-P-Score plus helplessness, loneliness, anger, as well as self-rated quality of life, assessed with the modified PQ-LES-Q (Endicott et al., 2006) rated on a VAS 0–100 scale, plus global physical health, global mental health, and global health and parentally rated C-GAS (Shaffer et al., 1983) and PQ-LES-Q (Endicott et al., 2006).

Secondary outcomes include frustration, anger, boredom, as well as suicidality (suicidal thoughts and attempts), number of episodes witnessing, enduring, or perpetrating aggressive behavior, substance abuse (alcohol, cannabinoids, others), gambling. COH-FIT also measures daily screen activities (social media use, gaming, watching TV or movies), as well as satisfaction with relationships and daily routine within the family, and how the child gets along with friends. Prosocial activities and resilience are further outcomes of interest. Coping strategies are ranked by the respondent by importance for successfully dealing with the coronavirus breakout. Ease and modality of access to care, and access and adherence to medications are also asked. In addition to analyzing the child's responses by themselves, we will also compare the child's and parental ratings on the difference in PQ-LES-Q.

2.2. COH-FIT-Adolescents

Adolescents aged 14 to 17 can participate in COH-FIT-AD.

Co-primary outcomes of COH-FIT-AD are well-being, measured with WHO-523 as in COH-FIT-C, and a composite psychopathology measure, “AD-P-Score” that is composed of the same items composing the co-primary P-Score outcome in adults (COH-FIT-A) (Solmi et al., 2021). Briefly, domains composing the P-score in COH-FIT-A were selected based on their correlation with the respective full validated questionnaires (Pearson correlation threshold r ≥ 0.5), among anxiety, depression, post-traumatic symptoms, psychosis, mania, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, stress, sleep, and concentration.

Key secondary outcomes are AD-P-Extended Score, which is composed of the same items composing the P-Extended Score in adults, and precisely of AD-P-Score plus items not correlating enough to make it to P-Score, plus helplessness, loneliness, anger, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and manic symptoms. Other key secondary outcomes are global physical health, global mental health, global health, as well as parentally rated C-GAS (Shaffer et al., 1983) and PQ-LES-Q (Endicott et al., 2006).

Secondary outcomes are individual psychopathology domains (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic, obsessive-compulsive, manic symptoms, mood swings, delusions, hallucinations), as well as panic, and sleep problems. Other secondary outcomes include self-injurious behaviors and suicidality (suicidal thoughts/attempts), number of episodes witnessing, enduring or perpetrating aggressive behaviors, other psychological experiences (helplessness, fear of infection, boredom, frustration, stress, cognition, anger, loneliness, substance use), other (gambling) addictive behaviors, as well as family, interpersonal, self-care functioning, social interactions, hobbies/free-time, work/school functioning, body mass index, pain, resilience, social altruism, and other daily behaviors (e.g., time spent on social media, internet, gaming, watching TV, reading, listening to music) and exercising. Ease and modality of access to care, adherence and access to medications are also asked.

2.3. COH-FIT-C&A analyses

Analyses will be run with STATA (Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 2017) and/or R (https://www.R-project.org) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna AURL. R Core Team 2019) with α<0.05. A detailed description of the general analytic plan is available elsewhere (Solmi et al., 2021). In addition to analyzing the child's/adolescent's responses, we will also compare the child's/adolescent's self-ratings on the PQ-LES-Q with the parental ratings of the child/adolescent and, in those who provided a household code, compare results across family members.

Briefly, to maximize representativeness of the estimates, weighting procedures will be applied. Within each country, estimates will be weighted according to official representative quota of age and sex (https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population). Furthermore, an additional adjustment factor will be considered in key secondary outcomes by continent analyses, which will be derived by the direct comparison of representative vs non-representative estimates at continent level.

Moreover, in analyses where countries are pooled together, each country will be assigned an adjustment factor accounting for the responses/country population ratio.

The association between explanatory factors and co-primary, key secondary, and secondary outcomes will be tested with multivariable linear or logistic regression analyses (depending on outcome of interest). Backward model selection and/or LASSO will be used to select the best multivariable model (Heinze et al., 2018), together with literature-based relevant factors. Analyses will also account for date/country matched COVID-19 metrics made available by Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins University 2020), and restriction information drawn from survey responses and/or national/regional databases.

Finally, alternative analytic strategies will be implemented according to hypotheses to be tested.

2.4. Strengths and limitations of the COH-FIT study

Among strengths of COH-FIT are the many languages the survey is available in, collecting data also from linguistic and ethnic minorities, ensuring inclusivity. Also, collecting data in several countries across different continents allows to compare countries among each other as well as providing a global picture. Furthermore, COH-FIT assesses a wide spectrum of outcomes, going beyond mental health and has a 3-wave design, collecting also long-term data, as well as longitudinal data at the population level, despite being a cross-sectional survey. More specifically, the multi-wave design together with the continuous data collection during the entire duration of the pandemic until it is declared over by the World Health organization in wave 1, and for 12 months each in waves 2 and 3, as well as the retrospective assessment of health and functioning during the last two weeks of respondents’ regular life before the pandemic can provide information on the longitudinal course of health and functioning at the population level. Main limitations include its cross-sectional design at the individual level, reliance on self-reports, limited parental report, and optional creation of the household survey that allows family-based analyses.

2.5. Preliminary participation data

Up to June 14th, 2021, overall 13,149 children and adolescents have participated in the survey (5,781 children, 7278 adolescents). Of these, 9,155were recruited via representative sampling (4550 children, 4605 adolescents). Responses have come so far from 11 countries with representative samples, namely Austria, Brazil, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, UK, USA, with Hungary being in the process of initiating recruitment of a representative pediatric sample, and 49 additional countries with non-probability sampling only. Such preliminary participation findings are of relevance when compared with the currently published literature on mental health outcomes of children and adolescents during the pandemic. A recent systematic review identified only 12 studies, reporting on a total of 12,262 children and adolescents, from China (seven studies), Italy (two studies), Poland, Turkey, and United States (one study each) (Nearchou et al., 2020). Overall, COH-FIT seems to be a unique resource to collect global evidence on health and functioning of children and adolescents during the pandemic, both in non-representative and representative samples.

3. Conclusions

Given the magnitude and reach of the global psychosocial stressor that the COVID-19 pandemic represents, understanding and mitigating the adverse effect of the pandemic on the health and well-being of youth is crucial. The COH-FIT project is well-suited to provide an international estimate of the impact of COVID-19 on children's, adolescents’ and families’ mental and physical health, well-being, functioning and quality of life. Such much needed data can inform the formulation of present and future evidence-based interventions and policies to minimize detrimental effects of the present and future pandemics on youth.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All conflict of interest statements of all authors are detailed below in supplementary Table 1.

Acknowledgements

All authors thank all respondents who took the survey so far, funding agencies and all professional and scientific national and international associations supporting or endorsing the COH-FIT project.

References

- Altman E.G., Hedeker D., Peterson J.L., Davis J.M. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale.; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Becker S.P., Breaux R., Cusick C.N., et al. Remote Learning During COVID-19: examining School Practices, Service Continuation, and Difficulties for Adolescents With and Without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Adolesc Heal. 2020;67(6):769–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerot S., Edman G., Anckarsäter H., et al. The Brief Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (BOCS): a self-report scale for OCD and obsessive-compulsive related disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68(8):549–559. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.884631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins C.A., Weathers F.W., Davis M.T., Witte T.K., Domino J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X., Becker B., Yu Q., et al. Prevalence and Psychosocial Correlates of Mental Health Outcomes Among Chinese College Students During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front psychiatry. 2020;11:803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S., Asherson P., Sonuga-Barke E., et al. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(6):412–414. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C., Ng K.C., Oh J.Y., Baeg A., Rajasegaran K., Chew C.S.E. Caring for Children and Adolescents With Eating Disorders in the Current Coronavirus 19 Pandemic: a Singapore Perspective. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(1):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragioti E., Li H., Tsitsas G., et al. A large scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychia. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27549. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Nee J., Yang R., Wohlberg C. Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q): reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(4):401–407. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000198590.38325.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze G., Wallisch C., Dunkler D. Variable selection – A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biometrical J. 2018;60(3):431–449. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201700067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising H.K., Veling W., Loewy R.L., et al. The validity of the 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1288–1296. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV). https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. Published 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

- Kinoshita S., Cortright K., Crawford A., et al. Changes in Telepsychiatry Regulations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: 17 Countries and Regions’ Approaches to an Evolving Healthcare Landscape. Psychol Med. 2020:1–33. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004584. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loades M.E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., et al. Rapid Systematic Review: the Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques de Miranda D., da Silva Athanasio B., Sena Oliveira A.C., Simoes-E-Silva A.C. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int J disaster risk Reduct IJDRR. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nearchou F., Flinn C., Niland R., Subramaniam S.S., Hennessy E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):1–19. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH17228479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidis A., Paksarian D., Alexander L., et al. The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. medRxiv Prepr Serv Heal Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.24.20181123. August2020.08.24.20181123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Bagge C.L., Gutierrez P.M., Konick L.C., Kopper B.A., Barrios F.X. The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8(4):443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna AURL. R Core Team. https://www.R-project.org/. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

- Susanne B., Gunnar E., Henrik A., Gunilla B., Christopher G., Björn H., et al. The Brief Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (BOCS): a Self-Report Scale for OCD and Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68(8) doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.884631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J., Catalan A., et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D., Gould M.S., Brasic J., Fisher P., Aluwahlia S., Bird H. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Roy D., Sinha K., Parveen S., Sharma G., Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M., Estrade A., Agorastos A., et al. The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times in Adults (COH-FIT-Adults): design and methods of an international on-line survey targeting physical and mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.048. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017.

- Topp C.W., Østergaard S.D., Søndergaard S., Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–176. doi: 10.1159/000376585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez L., Sampor C., Villanueva G., et al. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric cancer care in Latin America. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):753–755. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]