Abstract

Background

Social distancing measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 may profoundly impact young people’s relationships. This study compared adolescent and young adults’ romantic relationships and sexual activity before and after social distancing policies were enacted.

Methods

In June 2020, 351 youth participating in an ongoing intervention study in Fresno County, California completed an online survey about their experiences related to COVID-19. The survey included open and closed-ended questions about their romantic relationships, sexual activity, and online romantic or sexual interactions before and during social distancing restrictions. We used the chi-square test of independence to compare adolescent (ages 13–17) and young adults’ (ages 18–21) responses. Results were also compared to responses in the intervention study’s baseline survey.

Results

One-third (37%) of youth were dating or in a romantic relationship and 28% spent time in person with a partner early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Among those dating or in a relationship, 34% physically distanced from their partner due to parental restrictions related to COVID-19. Youth also spent less time in person with their partners during the pandemic than before. Although most youth (69%) were not sexually active before or during the pandemic, 22% had sex during the social distancing period. Young adults were more likely to spend time with their partners and have sex during the restrictions than adolescents. Most youth were not involved in sexting or online dating, before or during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Adolescents and young adults have continued to engage in sexual and romantic relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic, although many reported physical distancing from their partners. Results suggest that youth continue to need access to sexual health education and services during emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Adolescent, COVID-19, Social distancing, Sexual activity, Young adult, Romantic relationships

Background

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, state and local governments throughout the United States recommended minimizing contact between people, leading to the closure of schools and nonessential businesses, and shelter-in-place orders to reduce the spread of the disease. In some states, including California, these restrictions continued, particularly school closures. These social distancing measures have profoundly impacted the social lives of adolescents and young adults.

Social distancing from friends and romantic partners may be particularly challenging during adolescence, which is a period marked by a greater need for social connection and peer acceptance and increased risk taking [1, 2]. Popular and news media have portrayed young people as careless and unconcerned about becoming infected with COVID-19 [3, 4]. However, a growing body of research has found concern about COVID-19, support for social distancing guidelines, and participation in social distancing among adolescents and young adults [5–7].

Very little is known about how the pandemic has affected young people’s romantic and sexual relationships, which can have potential implications for positive, as well as negative, developmental outcomes [8, 9]. Researchers have posited that social distancing and stay-at-home guidelines have resulted in less partnered sex for most young people as they face increased parental monitoring and reduced privacy [10]. Studies in adult populations have found evidence of significant declines in sexual activity during the pandemic, although adults did not completely stop engaging in sexual activities [11–14], as well as evidence of increased romantic relationship conflict [15, 16]. Comparatively few studies in this area have included adolescent or young adult populations. In one study of adolescent sexual minority males, participants reported seeing their sexual partners less often during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. In another study with college students aged 18–25, most students reported a decrease in sexual activity [18]. Just as patterns of relationship involvement and sexual activity vary between adolescence and young adulthood [19, 20], additional research is needed to compare the pandemic’s impact on romantic and sexual relationships by age.

COVID-19 and social distancing guidelines may lead to an increase in young people’s online romantic or sexual interactions. Previous research has found that some adolescents initiate new relationships online [21–23], and young people often communicate with their partners through phone or text, including sexting [24, 25]. During the pandemic, youth may have turned more to forms of digital communication for romantic or sexual interactions, including online dating, sexting, virtual sex and other activities [10]. Research has found an increase in pornography viewing in the pandemic [26], including an increase in pornography use among adolescent sexual minority males [17].

The purpose of this study is to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on romantic relationships and sexual activity among an understudied population of predominantly Latino young people in Fresno County, California. Specifically, we ask if the pandemic resulted in: 1) physical distancing from romantic partners, 2) less sexual activity, and 3) more romantic or sexual interactions online. We also compared the impact of the pandemic on romantic relationships and sexual activity between adolescents and young adults.

Methods

Setting

Fresno County, located in the Central Valley of California, is the most productive agricultural county in the state and nation [27]. Despite this, the county has significantly higher percentages of total (61%) and youth (78%) concentrated poverty compared to the state averages of 30 and 46%, respectively [28]. Over a quarter of Fresno County’s population is aged 18 and younger (28%) and 54% of the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino [29].

On March 19, 2020, California issued the first statewide shelter-in-place order to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, directing all residents to stay home except to go to an essential job or seek basic necessities, such as food, prescriptions, and health care [30]. At the end of May 2020, California had approved Fresno County to begin reopening some sectors, including curbside retail, manufacturing, offices, childcare, and restaurants [31]. Businesses wishing to reopen were required to implement safety precautions such as masking indoors, limiting capacity, and screening employees daily for respiratory illness. However, rising COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations led to a statewide mandate for all Californians to wear masks in public on June 18, 2020, and to close most businesses again in mid-July, 2020 [32]. Virtually all of the schools in Fresno remained closed to in-person instruction throughout the majority of the 2020–21 academic year, offering distance learning instead. Compared to the rest of California, Fresno and other Central Valley counties have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Throughout the summer of 2020, Fresno County had significantly higher rates of COVID-19 compared to California, and the test positivity rate as of February 2021 remained higher than the state average [33].

Participants and procedures

Participants were selected from a sample of youth enrolled in a five-year, cluster randomized controlled trial of a sexual health education intervention in Fresno County, California [34]. Participants were initially recruited from 49 different sites, including alternative schools, foster homes, and afterschool programs. Youth were initially eligible to participate in the larger study if they lived in Fresno County, were aged 13–19, and spoke English or Spanish. The original study procedures included completing online surveys at baseline and at 3 and 9 months after baseline. Participants received a $10–$20 gift certificate after completing each survey. Passive parental or guardian consent, meaning parents or guardians needed to sign and return the consent form for refusal, was used per state guidelines for all sexual health education offered to youth [35]. Participants completed a consent/assent form at initial recruitment and prior to each subsequent survey.

In June 2020, 797 participants (out of 1260 who enrolled in the larger study) were invited to complete a supplemental online survey. We did not send the supplemental survey to 463 participants who were due to complete the 3-month or 9-month follow-up survey for the larger study. Non-respondents received reminder emails and/or text messages, and study researchers called a subset of participants (n = 30) who had started the survey to encourage them to complete it. Before starting the online survey, participants reviewed information about the study and checked a box confirming informed consent. The survey included questions on how COVID-19 had changed participants’ living arrangements and employment, use of technology, education, relationships, sexual and reproductive health, and health service use. The median time to complete the survey was 13 min. All participants received a $10 electronic gift card after completing the survey. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco.

Measures

All of the measures used in the analyses were collected in the supplemental survey, except where noted below.

Physical distancing from intimate partners

Participants were asked if they had “dated or been in a romantic or sexual relationship with anyone” in the last 3 months. If so, they were asked if they “spent time in person with someone you dated or were in a romantic or sexual relationship with” in the last 3 months and if they began living with someone they were dating as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Two items assessed how often they spent time in person with an intimate partner; one item asked, “BEFORE the coronavirus restrictions, how often (on average) did you do the following: Spend time with a date or romantic partner (in person)” and another item asked, “In the last 3 MONTHS (during the coronavirus restrictions), how often (on average) did you do the following: Spend time with a date or romantic partner (in person).” Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (daily).

Reasons for physical distancing from intimate partners

If participants reported an intimate relationship in the past 3 months, they were asked, “In the last 3 MONTHS, did you NOT spend time in person with someone you were dating or in a romantic or sexual relationship with for any of the following reasons? Check ALL that apply.” The response options are shown in Table 3. Participants also were asked to rate their agreement with the statement: “If you’re only dating one person, it’s okay to see each other during shelter-in-place.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree).

Table 3.

Among participants in a sexual or romantic relationship in the past 3 months, reasons for not spending time in person with their partner

| Total (n = 118) | Ages 13–17 (n = 69) | Ages 18–21 (n = 49) | P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| My parents wouldn’t let me go out because of the coronavirus | 40 | 33.9 | 30 | 43.5 | 10 | 20.4 | 0.009 |

| My date/partner’s parents wouldn’t let them go out because of the coronavirus | 20 | 17.0 | 16 | 23.2 | 4 | 8.2 | 0.032 |

| I was worried about getting the coronavirus | 14 | 11.9 | 8 | 11.6 | 6 | 12.2 | 0.914 |

| My date/partner was worried about getting the coronavirus | 8 | 6.8 | 7 | 10.1 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.084 |

| Lack of transportation | 25 | 21.2 | 13 | 18.8 | 12 | 24.5 | 0.459 |

| We broke up/stopped dating | 10 | 8.5 | 7 | 10.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 0.439 |

| I didn’t have time | 17 | 14.4 | 8 | 11.6 | 9 | 18.4 | 0.302 |

* p-value based on chi-square test comparing adolescents (ages 13–17) and young adults (ages 18–21)

Sexual activity

In the baseline and supplemental surveys, participants reported if they had ever had oral, vaginal, or anal sex and if they had had oral, vaginal, or anal sex in the past 3 months. Two items assessed how often participants had sex before the COVID-19 restrictions and in the last 3 months. The response options ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (daily).

Romantic or sexual interactions online

Participants were asked, “As a result of the coronavirus and shelter-in-place restrictions, how has the amount of time you spend doing the following changed,” followed by a list of online activities. The activities included “sexting (sending sexually explicit photos or messages),” “online dating/hook up sites (such as Bumble, Tinder, Hot or Not),” and “watching porn.” Response options were more time, about the same, less time, and I do not do this/does not apply.

Open-ended question

Participants were asked the open-ended question, “How has COVID-19 affected your dating or romantic or sexual relationships?”

Age group

We created a binary variable for developmental age group at the time of the supplemental survey. Adolescents were defined as ages 13–17 and young adults as ages 18–21.

COVID-19 attitudes

Participants reported whether they personally knew someone infected by the coronavirus, and they were asked to rate their concern about becoming infected with COVID-19 on a scale from 1 (very worried) to 3 (not worried at all).

Other participant characteristics

Participants reported their race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation in the baseline survey and their school enrollment, employment status, and living arrangement in the supplemental survey.

Analysis

We used the chi-square test of independence to compare outcomes by age group, gender identity, sexual orientation, knowing someone infected by COVID-19, and concern about becoming infected. All analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX), version 16.

To qualitatively analyze the open-ended question about the impact of the pandemic on their romantic relationships, we used a modified form of grounded theory in which an initial set of potential themes were identified based on the research’s key areas [36]. Two researchers reviewed the responses, created new codes based on emerging themes, and coded responses by theme. Researchers met to review the process, clarify codes, and make minor modifications to the coding to improve reliability. Responses were also classified by age, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

Results

Sample characteristics

Overall, 351 of 797 individuals responded to the supplemental COVID-19 survey (44% response rate), with 205 providing responses to the open-ended question about the effects of COVID-19 on their romantic relationships. Respondents to the supplemental survey were significantly younger, more likely to be female, Hispanic, have Internet access at home and on their phone, and less likely to be sexually experienced than non-respondents.

The majority of participants were female (72%), Hispanic (75%), and straight/heterosexual (83%), and the average age was 16.8 years (Table 1). Most participants (59%) were in middle or high school, 16% were in college, and 25% were no longer in school. Adolescents were significantly more likely to be in school and less likely to have a job than young adults. Most participants lived with their parents, including 95% of adolescents and 83% of young adults (p < 0.001). One quarter knew someone who had been infected by COVID-19, and most were very worried (17%) or somewhat worried (56%) about becoming infected themselves.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample (N = 351)

| Total (N = 351) | Ages 13–17 (n = 223, 63.5%) | Ages 18–21 (n = 128, 36.5%) | P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.130 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 260 | 75.1 | 171 | 78.1 | 89 | 70.1 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 16 | 4.6 | 10 | 4.6 | 6 | 4.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 16 | 4.6 | 6 | 2.7 | 10 | 7.9 | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 54 | 15.6 | 32 | 14.6 | 22 | 17.2 | |

| Gender | 0.073 | ||||||

| Female | 250 | 71.6 | 168 | 75.7 | 82 | 64.6 | |

| Male | 94 | 26.9 | 50 | 22.5 | 44 | 34.7 | |

| Transgender | 3 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Gender-queer/Non-binary | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.569 | ||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 285 | 82.9 | 179 | 81.7 | 106 | 84.8 | |

| LGBQ | 46 | 13.4 | 30 | 13.7 | 16 | 12.8 | |

| Questioning/not sure | 13 | 3.8 | 10 | 4.6 | 3 | 2.4 | |

| School enrollment | < 0.001 | ||||||

| In middle/high school | 206 | 59.0 | 191 | 86.0 | 15 | 11.8 | |

| In college | 57 | 16.3 | 9 | 4.1 | 48 | 37.8 | |

| Not in school | 86 | 24.6 | 22 | 9.9 | 64 | 50.4 | |

| Full or part-time job | 70 | 20.2 | 23 | 10.4 | 47 | 37.3 | < 0.001 |

| Living with parents | 320 | 91.4 | 215 | 96.4 | 105 | 82.7 | < 0.001 |

| Knows someone infected by coronavirus | 84 | 25.1 | 54 | 25.1 | 30 | 25.0 | 0.981 |

| How worried are you that you will catch COVID-19? | 0.465 | ||||||

| Very worried | 59 | 17.7 | 35 | 16.4 | 24 | 20.0 | |

| Somewhat worried | 188 | 56.3 | 119 | 55.6 | 69 | 57.5 | |

| Not at all worried | 87 | 26.1 | 60 | 28.0 | 27 | 22.5 | |

* p-value based on chi-square test comparing adolescents (ages 13–17) and young adults (ages 18–21)

Physical distancing from intimate partners during the COVID-19 pandemic

More than a third (37%) were dating or in a romantic relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic, including 33% of adolescents and 43% of young adults (p = 0.080) (Table 2). More than a quarter (28%) of all youth and 75% of those in a relationship spent time in person with their partner in the last 3 months. Young adults were more likely to spend time with a partner than adolescents (38% vs. 23%, p = 0.003). Eleven participants moved in with their partner in the last 3 months as a result of the pandemic, including eight young adults and three adolescents (not shown).

Table 2.

Adolescent and young adults’ romantic relationships, physical distancing, and sexual activity during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Total (N = 351) | Ages 13–17 (n = 223) | Ages 18–21 (n = 128) | P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Romantic relationships and physical distancing | |||||||

| Had an intimate partner in the past 3 months | 120 | 36.5 | 70 | 33.0 | 50 | 42.7 | 0.080 |

| Spent time in person with an intimate partner in the past 3 months | 92 | 27.9 | 48 | 22.5 | 44 | 37.6 | 0.003 |

| Sexual activity | |||||||

| Ever had oral, vaginal, or anal sex | 105 | 31.9 | 54 | 25.5 | 51 | 43.6 | 0.001 |

| Had oral, vaginal, or anal sex in the past 3 months | 74 | 22.3 | 37 | 17.3 | 37 | 31.4 | 0.003 |

* p-value based on chi-square test comparing adolescents (ages 13–17) and young adults (ages 18–21)

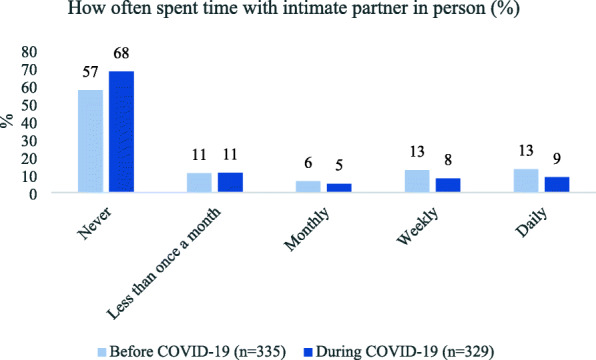

Youth spent time with a partner in person less often during the pandemic than before (Fig. 1). The percentage who saw a partner weekly declined from 13 to 8%, while those who saw a partner daily declined from 13 to 9%. A greater percentage of young adults than of adolescents spent time with a partner daily before COVID-19 (22% vs. 8%, p = 0.004) and during the pandemic (18% vs. 3%, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of spending time with an intimate partner, before and during COVID-19 restrictions

In response to the open-ended question, several participants mentioned they had not dated anyone since the start of shelter-in-place restrictions. One youth stated, “I was finally starting to get around to dating, but COVID-19 really put a stop on that” (female, lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer [LGBQ], age 19). Among those who were currently in a relationship, the majority said they had reduced or stopped spending time together in person. One responded, “I haven’t seen my boyfriend and when I have I had to wear a mask” (female, straight, age 16).

Several participants also commented that being physically apart from their partners negatively affected their relationships, fueling more arguments. One explained, “It’s made things more difficult; we’ve become more distant and fought way more than usual” (female, straight, age 18). However, others mentioned that they increased the amount of time communicating in other ways such as via FaceTime, texts, and calls. One youth explained, “It makes it hard for me and my boyfriend but we text every day and try to make the most of it” (transgender, pansexual, age 16). Another participant stated, “At first it ruined it due to me being on a stay at home order and couldn’t see them, but later on it helped the both of us a lot in ways that we maybe needed that time apart and even got to learn to communicate better” (female, straight, age 19).

Reasons for physical distancing from partners

Among the participants who were dating or in a romantic or sexual relationship, one third (34%) did not spend time in person with their partner because their parents would not let them go out due to COVID-19 (34%) (Table 3). In addition, 17% said that their partner’s parents would not let them go out because of the pandemic. Twelve percent felt worried about becoming infected, and 7% cited their partner’s concerns about becoming infected. One-fifth (21%) had not seen their partner due to lack of transportation.

Compared to young adults, adolescents were more likely to physically distance from their partners due to rules of their parents (44% vs. 20%, p = 0.098) or their partner’s parents (23% vs. 8%, p = 0.032). As expected, youth who were worried about getting the coronavirus were more likely to physically distance from partners due to concerns about infection. Among young adults, the most common reason for physically distancing from partners was lack of transportation (25%).

Most youth agreed (47%) or strongly agreed (12%) that “it is okay for intimate partners to spend time together in person during shelter-in-place if they are only dating one person,” while 29% disagreed and 13% strongly disagreed with this statement (not shown). Attitudes towards physically distancing from partners were similar across age groups.

Reasons for physical distancing in the open-ended responses also included parents’ restrictions and concern about becoming infected or infecting others. One youth stated, “At first, we didn’t see each other for over a month just for the fact to be safe because we both work around a lot of people” (female, straight, age 20). Another said, “I was afraid of seeing my partner because I was still visiting my sibling” (female, straight, age 19). A couple participants mentioned that school closures meant they could not see their partners on campus. As one explained, “School isn’t happening and I don’t get to see my boyfriend every day” (female, straight, age 17).

Sexual activity during the COVID-19 pandemic

In the supplemental survey, a third of youth (32%) indicated that they had ever had oral, vaginal, or anal sex, and 22% had sex in the past 3 months during the COVID-19 pandemic. When we compared reports of sexual activity in the past 3 months from the baseline and supplemental COVID-19 surveys, 69% were not sexually active before or during the pandemic, 14% of participants were sexually active in both periods, 9% were sexually active before COVID-19 only, and 8% were during the pandemic only.

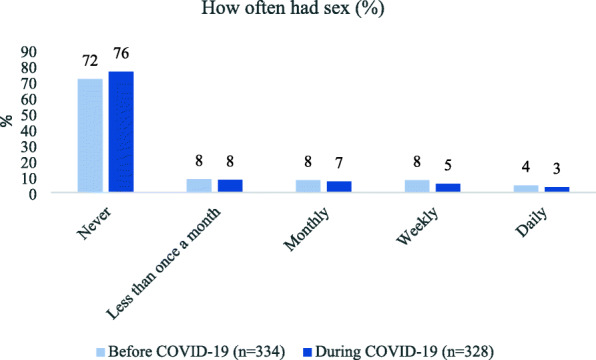

Compared to adolescents, young adults were significantly more likely to have ever had sex (44% vs. 26%, p = 0.001) and sex in the past 3 months (31% vs. 17%, p = 0.003). Compared to youth who identified as straight/heterosexual, LGBQ youth were more likely to ever have had sex (53% vs. 28%, p < 0.001) and sex in the past 3 months (34% vs. 20%, p = 0.024). Participants had sex slightly less often during the pandemic. The percentage of participants who had sex monthly declined from 8 to 7%, weekly declined from 8 to 5%, and daily declined from 4 to 3% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of having sex, before and during COVID-19 restrictions

In the open-ended responses, few focused on sexual activity, though one did mention that it affected her “relationship by not allowing contact and intimacy” (female, LGBQ, age 15). Another explained, “I haven’t had a extremely sexual relationship because I have strict parents. I seen my partner once ever[y] week so there wasn’t a huge impact” (female, LGBQ, age 17). One respondent noted, “some people want to wait until the coronavirus is over before they hangout so it blocks the act from happening” (female, straight, age 18).

Romantic or sexual interactions online

Overall, youth were not pursuing romantic or sexual relationships online during the pandemic. Three-quarters of youth (75%) indicated that they are not involved in sexting (Table 4). Eight percent of participants reported that they spend more time sexting, 6% spend less time, and 11% spend the same amount of time sexting due to COVID-19 and shelter-in-place restrictions. Compared to young adults, adolescents were more likely to report that they do not sext (81% vs. 62%, p = 0.002) and less likely to report more time sexting due to COVID-19 and shelter-in-place (11% vs. 6%, p = 0.002).

Table 4.

Self-reported change in the amount of time on online romantic or sexual interactions due to COVID-19 and shelter-in-place

| Total (N = 351) | Ages 13–17 (n = 223) | Ages 18–21 (n = 128) | P-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sexting | 0.002 | ||||||

| More time | 25 | 7.7 | 12 | 5.7 | 13 | 11.2 | |

| About the same | 36 | 11.0 | 15 | 7.1 | 21 | 18.1 | |

| Less time | 21 | 6.4 | 12 | 5.7 | 9 | 7.8 | |

| I do not do this/does not apply | 245 | 74.9 | 172 | 81.5 | 73 | 62.9 | |

| Online dating/hook up sites | < 0.001 | ||||||

| More time | 15 | 4.6 | 4 | 1.9 | 11 | 9.3 | |

| About the same | 14 | 4.3 | 5 | 2.4 | 9 | 7.6 | |

| Less time | 14 | 4.3 | 5 | 2.4 | 9 | 7.6 | |

| I do not do this/does not apply | 285 | 86.9 | 196 | 93.3 | 89 | 75.4 | |

| Watching porn | 0.061 | ||||||

| More time | 35 | 10.7 | 21 | 10.1 | 14 | 12.0 | |

| About the same | 35 | 10.7 | 18 | 8.6 | 17 | 14.5 | |

| Less time | 25 | 7.7 | 12 | 5.7 | 13 | 11.1 | |

| I do not do this/does not apply | 231 | 70.9 | 158 | 75.6 | 73 | 62.4 | |

* p-value based on chi-square test comparing adolescents (ages 13–17) and young adults (ages 18–21),

Most youth (87%) were not using online dating/hook up sites before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. Five percent said they spend more time online dating, 4% about the same amount of time, and 4% less time online dating due to the pandemic. Online dating was more common among young adults than adolescents (25% vs. 7%, p < 0.001) and among male than female participants (25% vs. 9%, p < 0.001).

The majority of youth (71%) indicated that they do not watch porn. One in ten participants (11%) spent more time watching porn due to COVID-19, 8% spent less time, and 11% spent the same amount of time. There were no significant age differences in time spent watching porn due to COVID-19, although watching porn was almost twice as common among males than females (46% vs. 23%, p < 0.001) and among straight/heterosexual than LGBQ participants (49% vs. 25%, p < 0.001).

Only two participants mentioned online dating and none discussed porn in the open-ended responses. One stated, “I feel like nobody has anything better to do at home [so] guys have been more bold recently and I’ve been getting way more messages on social media than I usually would” (female, straight, age 16). Another explained, “I wanted to try tinder or the other dating app so that I could go on dates but the dates would have to be online now” (female, LGBQ, age 19).

Discussion

This study examined how social distancing measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 early in the pandemic affected youth’s involvement in romantic and sexual relationships. We found that youth who were in romantic relationships spent less time in person with their partners during the COVID-19 pandemic than before, and one quarter spent no time in person with their partner during the first 3 months of social distancing. Romantic relationships are central to adolescent development [8, 9] and prolonged separation may have lasting impacts on youth. Studies have shown elevated levels of depression and anxiety among youth during the pandemic [37–39], suggesting that many will need ongoing mental health support. At the same time, our qualitative findings suggest that being apart led to improved communication in some youth relationships.

We did not find evidence that social distancing measures resulted in less partnered sex or increased online dating among youth, as others have posited [10]. In fact, most youth surveyed were not sexually active, participating in online dating, or sexting, before or during the pandemic. Previous studies in adult populations found significant declines in sexual activity during the pandemic, although adults did not completely stop engaging in sexual activity [11–14]. Further research is needed to understand the impact of the end of pandemic restrictions on adolescents’ romantic relationships and sexual behaviors, as researchers have posited there may be a “catch-up period” in which sexual behavior increases [10].

Experiences in romantic and sexual relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic varied between adolescents and young adults, which suggests the importance of studying the impact of the pandemic and other emergencies through a developmental perspective. Young adults were more likely to spend time with their partner and to be sexually active before and during the pandemic than adolescents. These results are consistent with the increase in autonomy that typically occurs in the transition to adulthood, along with other changes such as moving away from family and entering the labor market [40].

Study findings reinforce the importance of ensuring that young people have continued access to sexual and reproductive health care during the ongoing pandemic. While some youth have continued to be sexually active, due to shelter-in-place restrictions and limitations to in-person clinical services, contraception and other services have become more difficult to access [41–43]. Many healthcare providers have quickly adapted to offer services through telemedicine during the pandemic, although more research is needed to improve the reach and appropriateness of telemedicine among adolescents and young adults [44, 45]. Researchers have posited that sexually transmitted infections may have declined due to increased isolation and less casual sex during the pandemic, although others are concerned that the lack of testing and treatment may lead to an increase in transmission [46, 47]. Health providers need to heighten efforts to provide testing to adolescents and consider home-based or self-testing. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted potential strategies to reduce barriers to access including telemedicine visits, home-based testing, and online prescriptions that could continue as clinics resume in-person visits [48].

With fewer resources and the increased demands on schools due to the pandemic and transition to remote instruction, sexual health education may be of lower priority. However, adolescents continue to need accurate and age-appropriate sexual health information from a trusted source. Schools and community-based organizations may need support to proceed with sexual health education in an online or digital format. These alternative formats may be applicable in the future when other health concerns or emergencies, such as wildfires, cause school closures.

This study has limitations. First, the use of retrospective and single-item measures increased the risk of measurement error. Second, the study used a sample of youth participating in an ongoing study in Fresno County, California, and the sample is not representative of youth in the county or California. Respondents to the supplemental survey were significantly younger, more likely to be female, Hispanic, have Internet access at home and on their phone, and less likely to be sexually experienced than non-respondents. The level of sexual activity during the COVID-19 pandemic may be higher in the general population of youth. Third, because of the limited sample size, the results of comparisons by gender and sexual orientation must be interpreted cautiously, and we were unable to examine other important characteristics, such as housing status. A higher response rate may have been achieved with additional time and efforts at follow up and/or a gift certificate of greater value. However, the results highlight the experiences of a predominately Hispanic population who are often underrepresented in research and media depictions of COVID-19.

As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves over time, so will its impact on youth and their relationships. It will be important to continue to study the short and long-term impacts of the pandemic on youth relationships and their sexual health. Future research should assess if the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a lasting shift in relationship development among adolescents and young adults, including changes in their approach to casual sex, communication styles, and use of online dating. In addition, future research should examine not only the negative impacts of the pandemic, but also young people’s resiliency and post-pandemic growth in their relationships and lives.

Conclusions

This is one of the first studies to examine the immediate impacts of social distancing requirements on young people’s romantic and sexual relationships, asking about their experiences during the first 3 months of the shelter-in-place restrictions. We found that adolescents and young adults have continued to engage in sexual and romantic relationships during the pandemic, although many reported physical distancing from their partners. Most youth were not sexually active before or during the pandemic, yet nearly a quarter had sex during this period. The results demonstrate that youth continue to need access to sexual health education and services during emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Personal Responsibility Education Innovative Strategies research grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, Family and Youth Services Bureau under contract # 90AP2688. The authors are grateful to Melissa Saphir, PhD for her feedback on the survey instrument, Ushma Upadhyay, PhD, MPH and participants in the UCSF Bixby Center Early Career Investigators Work in Progress Seminar for their feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript, and youth who have participated in this study.

Authors’ contributions

MD, AGG, and JY contributed to the conception and design of the study. AGG completed all data collection and contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript. JY and SH conducted data analysis and wrote the first version of the manuscript. MD contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Personal Responsibility Education Innovative Strategies research grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, Family and Youth Services Bureau [contract number 90AP2688]. The sponsors were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, Family and Youth Services Bureau.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board for the Human Research Protection Program of the University of California, San Francisco approved this study (IRB# 17–22381). All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Helsinki Declaration for Human Studies. Informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants in the study. In addition, passive informed consent from parents or guardians was solicited for those aged less than 18 years.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Yarger, Email: jennifer.yarger@ucsf.edu.

Abigail Gutmann-Gonzalez, Email: abigail.gutmann-gonzalez@ucsf.edu.

Sarah Han, Email: sarah_han@berkeley.edu.

Natasha Borgen, Email: natasha.borgen@ucsf.edu.

Martha J. Decker, Email: mara.decker@ucsf.edu

References

- 1.Andrews JL, Foulkes L, Blakemore S-J. Peer influence in adolescence: public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakemore S-J. Avoiding social risk in adolescence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2018;27(2):116–122. doi: 10.1177/0963721417738144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll R. Coronavirus is a threat to young people too, U.S. official Fauci tells NBA star Curry. Reuters; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg L. Opinion: expecting students to play it safe if colleges reopen is a fantasy. The New York Times. 2020.

- 5.Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, Shook N. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler MÉ, Tynan MA, Howard ME, Honeycutt S, Fulmer EB, Kidder DP, et al. Public attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs related to COVID-19, stay-at-home orders, nonessential business closures, and public health guidance: United States, New York City, and Los Angeles, May 5–12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):751–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cohen AK, Hoyt LT, Dull B. A descriptive study of COVID-19-related experiences and perspectives of a national sample of college students in spring 2020. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60(1):631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. p. 3–22.

- 10.Lindberg LD, Bell DL, Kantor LM. The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(2):75–79. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2024–2032. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02894-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li GJ, Tang DD, Song B, Wang C, Shen QS, Xu C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on partner relationships and sexual and reproductive health: cross-sectional, online survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e20961. 10.2196/20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Coombe J, Kong FYS, Bittleston H, Williams H, Tomnay J, Vaisey A, Malta S, Goller JL, Temple-Smith M, Bourchier L, Lau A, Chow EPF, Hocking JS. Love during lockdown: findings from an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual health of people living in Australia. Sex Transm Infect. 2020;97(5):357–362. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig-Kuhn MC, Schmidt N, Scott G, Jr, Gomes G, TatahMentan M, Enaholo O, et al. Changes in sexual behavior related to the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders among young black men who have sex with women in New Orleans. LA Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(8):589–594. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luetke M, Hensel D, Herbenick D, Rosenberg M. Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(8):747–762. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1810185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SJ, Ward KP, Rodriguez CM. Longitudinal analysis of short-term changes in relationship conflict during COVID-19: a risk and resilience perspective. J Interpers Violence. 2021:088626052110063. 10.1177/08862605211006359. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Nelson KM, Gordon AR, John SA, Stout CD, Macapagal K. “Physical sex is over for now”: impact of COVID-19 on the well-being and sexual health of adolescent sexual minority males in the US. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(6):756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firkey MK, Sheinfil AZ, Woolf-King SE. Substance use, sexual behavior, and general well-being of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a brief report. J Am Coll Heal. 2020:1–7. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1869750. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Martinez GM, Abma JC. Sexual activity and contraceptive use among teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States, 2015–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 366. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed]

- 20.Meier A, Allen G. Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Sociol Q. 2009;50(2):308–35. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lykens J, Pilloton M, Silva C, Schlamm E, Wilburn K, Pence E. Google for sexual relationships: mixed-methods study on digital flirting and online dating among adolescent youth and young adults. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2019;5(2):e10695. doi: 10.2196/10695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blunt-Vinti HD, Wheldon C, McFarlane M, Brogan N, Walsh-Buhi ER. Assessing relationship and sexual satisfaction in adolescent relationships formed online and offline. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korchmaros JD, Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Adolescent online romantic relationship initiation: differences by sexual and gender identification. J Adolesc. 2015;40:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, Zimmerman M. Sexting among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi HJ, Mori C, Van Ouytsel J, Madigan S, Temple JR. Adolescent sexting involvement over 4 years and associations with sexual activity. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mestre-Bach G, Blycker GR, Potenza MN. Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(2):181–183. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2017 Census of Agriculture, County Profile: Fresno County, California 2017. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/County_Profiles/California/cp06019.pdf. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

- 28.California Department of Health, Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health, Fresno County, 2016. 2018. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DMCAH/CDPH%20Document%20Library/Data/Adolescent/County-Profile-Fresno_2016.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- 29.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Fresno County, California. 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fresnocountycalifornia. Accessed 14 Aug 2020.

- 30.State of California, Executive Department. Executive Order N-33-20. 2020. https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/3.19.20-attested-EO-N-33-20-COVID-19-HEALTH-ORDER.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- 31.County of Fresno, California. Fresno County to advance further into Stage 2 of reopening [press release]. 2020. https://www.co.fresno.ca.us/Home/Components/News/News/587/1557. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

- 32.Procter R. Remember when? Timeline marks key events in California’s year-long pandemic grind. CalMatters. 2021. https://calmatters.org/health/coronavirus/2021/03/timeline-california-pandemic-year-key-points/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- 33.State of California . Tracking COVID-19 in California. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decker MJ, Gutmann-Gonzalez A, Price M, Romero J, Sheoran B, Yarger J. Evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention integrating technology and in-person sexual health education for adolescents (In the Know): protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(8):e18060. 10.2196/18060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.California Healthy Youth Act, California Education Code §§ 51930–51939.

- 36.Dey I. Grounding grounded theory: guidelines for qualitative inquiry. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(32):1049. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magson NR, Freeman JY, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(1):44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Miranda DM, da Silva Athanasio B, de Sena Oliveira AC, Silva ACS. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;101845:101845. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindberg LD, VandeVusse A, Mueller J, Kirstein M. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the 2020 Guttmacher survey of reproductive health experiences. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2020.

- 42.Lin TK, Law R, Beaman J, Foster DG. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic security and pregnancy intentions among people at risk of pregnancy. Contraception. 2021;103(6):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis R, Blake C, Shimonovich M, Coia N, Duffy J, Kerr Y, et al. Disrupted prevention: condom and contraception access and use among young adults during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. An online survey. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2021. 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Barney A, Buckelew S, Mesheriakova V, Raymond-Flesch M. The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: challenges and opportunities for innovation. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):164–71. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Wood SM, White K, Peebles R, Pickel J, Alausa M, Mehringer J, Dowshen N. Outcomes of a rapid adolescent telehealth scale-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Döring N. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting our sexualities? An overview of the current media narratives and research hypotheses. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(8):2765–2778. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01790-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alpalhão M, Filipe P. The impacts of isolation measures against SARS-CoV-2 infection on sexual health. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2258–2259. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02853-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mmeje OO, Coleman JS, Chang T. Unintended consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual and reproductive health of youth. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):326–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.