Abstract

Habitat loss due to climate change may cause the extinction of the clonal species with a limited distribution range. Thus, determining the genetic diversity required for adaptability by these species in sensitive ecosystems can help infer the chances of their survival and spread in changing climate. We studied the genetic diversity and population structure of Sambucus wightiana—a clonal endemic plant species of the Himalayan region for understanding its possible survival chances in anticipated climate change. Eight polymorphic microsatellite markers were used to study the allelic/genetic diversity and population structure. In addition, ITS1–ITS4 Sanger sequencing was used for phylogeny and SNP detection. A total number of 73 alleles were scored for 37 genotypes at 17 loci for 8 SSRs markers. The population structural analysis using the SSR marker data led to identifying two sub-populations in our collection of 37 S. wightiana genotypes, with 11 genotypes having mixed ancestry. The ITS sequence data show a specific allele in higher frequency in a particular sub-population, indicating variation in different S. wightiana accessions at the sequence level. The genotypic data of SSR markers and trait data of 11 traits of S. wightiana, when analyzed together, revealed five significant Marker-Trait Associations (MTAs) through Single Marker Analysis (SMA) or regression analysis. Most of the SSR markers were found to be associated with more than one trait, indicating the usefulness of these markers for working out marker-trait associations. Moderate to high genetic diversity observed in the present study may provide insurance against climate change to S. wightiana and help its further spread.

Subject terms: Biodiversity, Climate-change ecology

Introduction

Climate warming is affecting the biodiversity and functioning of plant communities across the globe, and in response to this changing climate, species are now shifting their geographical distributions and expanding their ranges across elevational and latitudinal gradients1,2. This range expansion can increase the survival chances of species that might get affected by climate change driven shrinkage of suitable habitats; however, individual species' range responses vary greatly, with some species changing their ranges and/or local abundances rapidly while others do so slowly or not at all3,4. A growing body of literature seeks to explain this variation in range shifts using species’ ecological and life-history traits, with expectations that these shifts are determined by the capacity of species to disperse, establish new populations, and proliferate in the new environments5,6. In this race for survival, clonal plants appear to be at a particular disadvantage due to their limited mobility and limited capacity for adaptation7. Although, clonal plants have persisted for thousands, or even millions of years during past environmental changes8, the future climate change is predicted to advance much faster than during post-glacial times9. If a species can neither adapt to the modified environmental conditions nor migrate fast enough, then population extirpation or in the worst-case extinction of entire species is expected10,11. This extinction can be avoided if the populations undergo evolutionary adaptation12–14; however, the evolutionary potential of a population in turn depends on the pre-existing genetic variation within the species, and a high level of standing variation may allow a faster response to environmental changes15,16. Thus, empirical studies that estimate genetic diversity in clonal species with limited distribution ranges are important for understanding their possible survival chances in anticipated climate change.

Although the advent of new molecular tools had a major impact on the study of clonality in plant species, the results from genotyping have quite often been interpreted without consideration of the restrictions of the genetic markers used17, probably resulting in biased estimation of the extent of clonality. Moreover, the low resolution of allozyme markers often leads to an overestimation of the extent of clonality18. On the other hand, due to failure to account for small differences between multi-locus genotypes because of PCR and scoring errors or somatic mutations, the use of high-resolution markers such as Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphisms (AFLPs) may lead to an under-estimation of the extent of clonality19. Some molecular markers, e.g., Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) have been the marker of choice due to their high polymorphism detection, high reproducibility, co-dominant nature, cost-effectiveness, and ease of study20. In addition to molecular markers, Internal Transcriber Spacers (ITS) have been frequently used for phylogenetic analysis21 and the study of genetic diversity. ITS ribosomal DNA length variants have been reported for several plant species22,23. In the present study, eight SSR markers, initially designed for Sambucus nigra, and ITS1–ITS4 region Sanger sequencing, were used to quantify the genetic diversity of Sambucus wightiana (an endemic clonal plant species) to predict its survival chances and potential spread during anticipated climate change. The species is commonly found in forest gaps making way into the canopy, threatening the suitable habitat of many important medicinal plants, decreasing understory plant diversity, and potentially hindering the natural regeneration of conifer saplings.

Results

Allelic and gene diversity

SSR markers used during the present study successfully amplified expected genomic regions in a set of 37 S. wightiana accessions/genotypes. Multiple loci were amplified by most of the SSR markers as evident by the fact that these 8 SSR makers amplified 17 loci ranging from 1 locus to 3 loci with an average of 2.12 loci per SSR marker. While counting the number of alleles per marker, it was revealed that a total of 73 alleles were amplified by all the 8 SSR markers using 37 S. wightiana genotypes. The number of alleles varied from 7 for SSR marker “EMSn016” and “EMSn003” to 1 for SSR marker “EMSn023” and “EMSn025” with an average of 9.12 alleles/marker. The average number of alleles detected per loci was 4.29 (Total alleles = 73/Total loci = 17) and the percent polymorphic loci was 70.59%. The analysis of gene diversity data revealed moderate gene diversity (He) noticed for all SSR marker loci, which varied from 0 (for monomorphic loci) and 0.818 with an average of 0.526 (SE = 0.086). Except for the monomorphic loci of Sn023 and Sn025 the average He was high with an average of 0.745. The mean values uHe and I were 0.534 (SE = 0.087) and 1.086 (SE = 0.179) respectively (Table 1). Further analysis of marker data based on 37 genotypes of 7 watersheds is presented in Table 2. The analysis revealed that the average number of alleles (Na) ranged from 1.412 for sub-population 6, 7 to 3.059 for sub-population 1. The private alleles were found in only 2 populations: Pop1 and Pop4 with 0.143 and 0.167 frequency with an overall mean of 0.11. The mean effective number of alleles ranged from 1.412 to 2.458, which were comparable to the average number of alleles. The gene diversity (He) and uHe values ranged from 0.206 to 0.445 and 0.275 to 0.475 respectively. Also, Shannon’s information index (I) was calculated for populations with the highest diversity found in Pop1 (I = 0.828, SE = 0.151) and lowest in Pop6 (I = 0.285, SE = 0.085).

Table 1.

Genetic diversity estimates for Sambucus wightiana at seventeen loci and averaged over all sub-populations.

| Primer | Primer sequences | Locus | N | Na | Ne | I | He | uHe | nP | PIC = 2 × F (1 − F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMSn002 | F | AACACTAGAAACATAAATTCAAAGTGG | Sn002a | 33 | 5 | 3.351 | 1.369 | 0.702 | 0.712 | 0 | 0.2571 |

| R | TAATTCTCATTCGCGGTTCG | Sn002b | 23 | 5 | 3.861 | 1.458 | 0.741 | 0.757 | 0 | 0.3403 | |

| Sn002c | 37 | 5 | 3.283 | 1.397 | 0.695 | 0.705 | 0 | 0.2337 | |||

| EMSn003 | F | TCGTCTTTTCCGACTCTAAAGC | Sn003a | 36 | 7 | 5.492 | 1.811 | 0.818 | 0.829 | 0 | 0.3133 |

| R | CTGGACATTTGCGATCTGG | Sn003b | 35 | 5 | 3.267 | 1.39 | 0.694 | 0.704 | 0 | 0.2449 | |

| EMSn010 | F | ACATCAAACCCTGCAACACC | Sn010a | 34 | 5 | 3.959 | 1.473 | 0.747 | 0.759 | 0 | 0.2509 |

| R | TCGCTCTAATTCCAACATTGC | Sn010b | 34 | 5 | 3.026 | 1.32 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.2509 | |

| EMSn016 | F | GGCGCAGACCAATTATAACATAG | Sn016a | 31 | 6 | 5.491 | 1.744 | 0.818 | 0.831 | 0 | 0.3122 |

| R | TCCACCATTCTTCCTTCTGC | Sn016b | 27 | 7 | 4.893 | 1.726 | 0.796 | 0.811 | 2 | 0.3841 | |

| Sn016c | 33 | 6 | 5.161 | 1.705 | 0.806 | 0.819 | 0 | 0.2975 | |||

| EMSn017 | F | GGTATTGCTTGAACAATCATCG | Sn017 | 33 | 6 | 3.138 | 1.441 | 0.681 | 0.692 | 0 | 0.2975 |

| R | GCCTTTTGCCCAAACTATCC | ||||||||||

| EMSn019 | F | GGTGAAACTTGAAAATCCTAGCC | Sn019 | 37 | 6 | 4.43 | 1.63 | 0.774 | 0.785 | 0 | 0.2717 |

| R | GGTCCGAAATAGAACACTAAAGC | ||||||||||

| EMSn023 | F | TGGCATTTGTTTAATGATCACG | Sn023a | 28 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0689 |

| R | TTTAAAGAAGGGGTGAACACG | Sn023b | 28 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0689 | |

| EMSn025 | F | AATGCATCGCAAGAAAAAGG | Sn025a | 31 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0624 |

| R | GGTAAGATAAATGATACAATGTTTTGG | Sn025b | 31 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0624 | |

| Sn025c | 30 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0644 | |||

| Mean | 31.82 | 4.294 | 3.197 | 1.086 | 0.526 | 0.534 | 0.11 | 0.222 | |||

| SE | 0.92 | 0.554 | 0.402 | 0.179 | 0.086 | 0.087 | 0 |

N; Sample size, Na; No. of Alleles, Ne; No. of Effective Alleles, I; Information Index, He; Expected Heterozygosity, uHe; Unbiased Expected Heterozygosity, nP; Number of Private Alleles and PIC; Polymorphic Information Content.

Table 2.

Mean allelic patterns across populations of Sambucus wightiana.

| Population | Na (SE) | Na Freq. > = 5% (SE) | Ne (SE) | I (SE) | Np (SE) | No. LComm alleles (< = 50%) (SE) | He (SE) | uHe (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop1 | 3.059 (0.406) | 3.059 (0.406) | 2.458 (0.316) | 0.828 (0.151) | 0.059 (0.059) | 1.529 (0.298) | 0.445 (0.078) | 0.475 (0.083) |

| Pop2 | 2.294 (0.306) | 2.294 (0.306) | 2.140 (0.292) | 0.647 (0.136) | – | 1.059 (0.218) | 0.384 (0.075) | 0.443 (0.086) |

| Pop3 | 2.235 (0.291) | 2.235 (0.291) | 1.786 (0.192) | 0.554 (0.124) | – | 0.882 (0.270) | 0.324 (0.070) | 0.345 (0.075) |

| Pop4 | 2.529 (0.344) | 2.529 (0.344) | 2.136 (0.273) | 0.687 (0.136) | 0.059 (0.059) | 1.000 (0.257) | 0.397 (0.072) | 0.429 (0.078) |

| Pop5 | 1.706 (0.187) | 1.706 (0.187) | 1.647 (0.183) | 0.422 (0.107) | – | 0.471 (0.194) | 0.278 (0.068) | 0.337 (0.083) |

| Pop6 | 1.412 (0.123) | 1.412 (0.123) | 1.412 (0.123) | 0.285 (0.085) | – | 0.471 (0.174) | 0.206 (0.062) | 0.275 (0.082) |

| Pop7 | 1.412 (0.173) | 1.412 (0.173) | 1.412 (0.173) | 0.367 (0.086) | – | 0.471 (0.151) | 0.265 (0.062) | 0.353 (0.083) |

Na = No. of Different Alleles.

Na (Freq > = 5%) = No. of Different Alleles with a Frequency > = 5%

Ne = No. of Effective Alleles = 1/(Sum pi^2).

I = Shannon's Information Index = − 1* Sum (pi * Ln (pi)).

No. Private Alleles = No. of Alleles Unique to a Single Population.

No. LComm Alleles (< = 25%) = No. of Locally Common Alleles (Freq. > = 5%) Found in 25% or Fewer Populations.

No. LComm Alleles (< = 50%) = No. of Locally Common Alleles (Freq. > = 5%) Found in 50% or Fewer Populations.

He = Expected Heterozygosity = 1 − Sum pi^2.

uHe = Unbiased Expected Heterozygosity = (2 N/(2 N − 1)) * He.

Clustering and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA)

To understand the patterns of variations of genetic diversity by SSR data, two multivariate methods were employed; clustering and principal coordinate analysis.

Clustering

The clustering analysis of the 37 genotypes collected across the geographical spectrum of the S. wightiana in the Kashmir valley revealed three main clusters (Fig. 1). Cluster I contain two small sub-clusters Ia (Samb-1 and Samb-3) and sub-cluster Ib. The sub-cluster Ib is further divided into 2 more small clusters Ib1 (Samb-13 and Samb-32) and Ib2 (Samb-33, 34, and 36). Cluster II is sub-divided into two clusters, sub-cluster IIa (Samb-25, 26, and 27) and sub-cluster IIb. The sub-cluster IIb is further divided into two small clusters cluster IIb1 (Samb-7, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 21) and IIb2 (Samb-11, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24) with several smaller sub-clusters. Cluster III is divided into two sub-clusters, sub-cluster IIIa and sub-cluster IIIb. Sub-cluster IIIa is further divided into two smaller clusters cluster IIIa1 (samb-11, 12, and 35) and cluster IIIa2 (Samb-8, 9, 10, and 28). Sub-cluster IIIb is further divided into IIIb1 (Samb-2) and IIIb2 (samb-4, 5, 6, 29, 30, 31, and 37). The clustering does not show any rigid correspondence between genotypes and their geographic location.

Figure 1.

UNJ dendrogram showing clustering pattern of S. wightiana Samples (DARwin ver. 6.0; http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin).

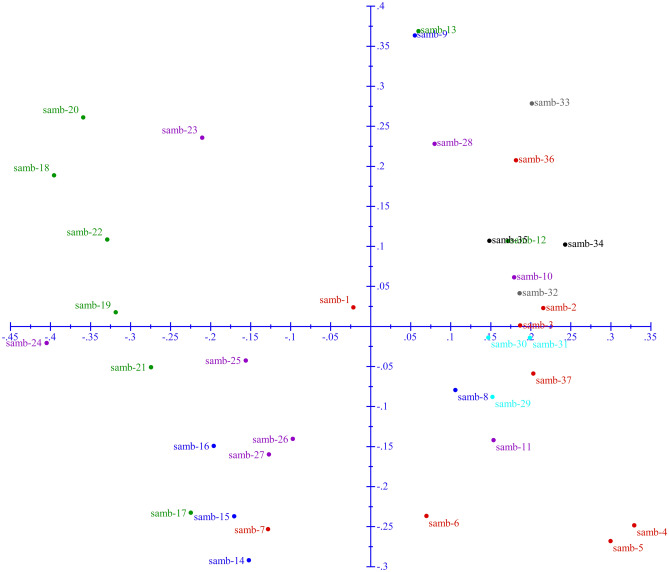

Principal co-ordinate analysis (PCoA)

Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was carried by using the data matrix/scores (1-presence and 0-absence) of all 8 SSR markers that led to the uniform spread of all 37 S. wightiana genotypes into all 4 coordinates (Fig. 2). Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) could not identify significant isolation in populations as all genotypes were widely distributed in all the quadrants (I and IV) of factorial analysis. PCoA could not identify any significant isolation and rigid assemblies of genetic proximity to spatial distribution.

Figure 2.

Results of the principal coordinates analysis of 17 microsatellite loci in S. wightiana (DARwin ver. 6.0; http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin).

The analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA)

AMOVA was carried to analyze the distribution of genetic variation among sub-population from 7 different watersheds representing the different populations and among and within individuals/accessions/genotypes. The AMOVA revealed that the majority of the genetic variation is partitioned among individuals (i.e., within site/population) i.e., 90% and only 10% variation is present among populations (Table 3). Based on AMOVA the genetic differentiation values for global Fst, Fst max, and F’st were 0.104, 0.403, and 0.258 respectively indicating a moderate level of genetic differentiation among populations. Pairwise Fst genetic distances between each pair of population/subpopulations were also estimated. The values for pairwise Fst between populations/ sub-populations 1–4 and 6–7 were high (0.125 and 0.417 respectively) with an average of 0.285 (Table 4). Pairwise Nei’s Genetic Distance, Nei’s Genetic identity, and corresponding unbiased Nei’s Genetic Distance and Nei’s Genetic identity values (Table 5) were in agreement with pairwise Fst calculations reflecting a moderate genetic differentiation among populations. Chi-Square Tests for Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium revealed the probability at all loci except for 2 monomorphic loci; Sn023 and Sn025 were statistically significant (Table 6) confirming the deviation from the HWE and nonrandom mating of S. wightiana with subtle signs of inbreeding.

Table 3.

Summary of analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA).

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var | Variation explained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 6 | 96.302 | 16.050 | 0.588 | 10.5 |

| Among Indiv | 30 | 303.705 | 10.123 | 5.059 | 89.4 |

| Within Indiv | 37 | 0.220 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.1 |

| Total | 73 | 400.226 | 5.653 | 100 |

Table 4.

Pairwise population Fst values.

| Pop1 | Pop2 | Pop3 | Pop4 | Pop5 | Pop6 | Pop7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop1 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Pop2 | 0.161 | 0.000 | |||||

| Pop3 | 0.182 | 0.224 | 0.000 | ||||

| Pop4 | 0.125 | 0.198 | 0.146 | 0.000 | |||

| Pop5 | 0.212 | 0.295 | 0.311 | 0.271 | 0.000 | ||

| Pop6 | 0.299 | 0.354 | 0.381 | 0.387 | 0.317 | 0.000 | |

| Pop7 | 0.269 | 0.382 | 0.405 | 0.306 | 0.348 | 0.417 | 0.000 |

Maximum and minimum Fst values are given in bold.

Table 5.

Genetic Diversity Indices analyzed in S. wightiana populations; Pairwise Population Matrix of (a) Nei’s Genetic Distance, (b) Nei’s Unbiased Genetic Distance, (c) Nei’s Genetic Identity and (d) Nei’s Unbiased Genetic Identity.

| Pop1 | Pop2 | Pop3 | Pop4 | Pop5 | Pop6 | Pop7 | Pop1 | Pop2 | Pop3 | Pop4 | Pop5 | Pop6 | Pop7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | ||||||||||||||

| Pop1 | 0 | Pop1 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Pop2 | 0.316 | 0 | Pop2 | 0.238 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Pop3 | 0.307 | 0.357 | 0 | Pop3 | 0.264 | 0.29 | 0 | ||||||||

| Pop4 | 0.248 | 0.372 | 0.194 | 0 | Pop4 | 0.194 | 0.294 | 0.15 | 0 | ||||||

| Pop5 | 0.356 | 0.49 | 0.517 | 0.444 | 0 | Pop5 | 0.286 | 0.396 | 0.458 | 0.374 | 0 | ||||

| Pop6 | 0.48 | 0.555 | 0.613 | 0.682 | 0.358 | 0 | Pop6 | 0.408 | 0.46 | 0.552 | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0 | ||

| Pop7 | 0.343 | 0.636 | 0.616 | 0.416 | 0.361 | 0.496 | 0 | Pop7 | 0.339 | 0.609 | 0.623 | 0.412 | 0.341 | 0.474 | 0 |

| c | d | ||||||||||||||

| Pop1 | 1 | Pop1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Pop2 | 0.729 | 1 | Pop2 | 0.788 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Pop3 | 0.735 | 0.7 | 1 | Pop3 | 0.768 | 0.748 | 1 | ||||||||

| Pop4 | 0.78 | 0.689 | 0.824 | 1 | Pop4 | 0.824 | 0.745 | 0.86 | 1 | ||||||

| Pop5 | 0.7 | 0.613 | 0.596 | 0.642 | 1 | Pop5 | 0.751 | 0.673 | 0.632 | 0.688 | 1 | ||||

| Pop6 | 0.619 | 0.574 | 0.542 | 0.505 | 0.699 | 1 | Pop6 | 0.665 | 0.632 | 0.576 | 0.543 | 0.763 | 1 | ||

| Pop7 | 0.71 | 0.529 | 0.54 | 0.659 | 0.697 | 0.609 | 1 | Pop7 | 0.712 | 0.544 | 0.537 | 0.662 | 0.711 | 0.622 | 1 |

Maximum and minimum values for different diversity indices; a, b, c, and d are highlighted in bold.

Table 6.

Summary of chi-square tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

| Pop | Locus | DF | ChiSq | Prob | Signif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop1 | Sn016a | 15 | 155.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn016b | 21 | 162.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn016c | 15 | 165.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn010a | 10 | 136.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn010b | 10 | 136.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn017 | 15 | 165.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn019 | 15 | 185.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn023a | Monomorphic | |||

| Pop1 | Sn023b | Monomorphic | |||

| Pop1 | Sn025a | Monomorphic | |||

| Pop1 | Sn025b | Monomorphic | |||

| Pop1 | Sn025c | Monomorphic | |||

| Pop1 | Sn02a | 10 | 132.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn02b | 10 | 92.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn02c | 10 | 148.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn03a | 21 | 216.000 | 0.000 | *** |

| Pop1 | Sn03b | 10 | 140.000 | 0.000 | *** |

Key: ns = not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

ITS region sequence analysis

The Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region that lies between nuclear small rDNA and nuclear large rDNA is considered most important for phylogenetic inference at the generic and intrageneric levels in plants (Alvarez and Wendel 2003). The ITS sequence data has been used in ~ 66% of studies to analyze the phylogeny and 34% of all published phylogenetic hypotheses have been based exclusively on ITS sequences23,24. Therefore, efforts have been made during the present study to sequence the ITS region of 37 S. wightiana accessions/genotypes collected from the North-Western Himalayas of Jammu and Kashmir. The sequence data generated during the present study was also compared with ITS region sequencing data of 18 other Sambucus species including S. wightiana. The analysis of sequencing data led to the identification of 10 SNPs (SNP density: 1 SNP/ 57.2 bp) in the 645 bp sequence of 37 S. wightiana genotypes. Among the 10 SNPs, five SNPs were found very promising (Table 7), and the frequency of these SNPs was either 20% or > 20%. In addition, one insertion has also been noticed with a frequency of 34%. A large number of SNPs were also noticed while comparing the S. wightiana genotypes with the ITS sequences of 18 other Sambucus species. One large insertion of ~ 25 bp was identified in S. wightiana or deletion of 25 bp in other 18 Sambucus species. Sequence variation between different genotypes has been identified at ITS sequence in several earlier studies in different plants including Cinnamomum25, Jujube26, Common bean21,24, Coneflowers and Relatives27, and Sambucus and Adoxa28. The important SNPs identified during the present study could be converted into user-friendly PCR-based markers for species discrimination, genetic characterization, and phylogeny analysis.

Table 7.

List of SNPs detected in the ITS sequences of S. wightiana.

| Genotype | SNP/insertion position | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 108 | 157 | 195 | 451 | 453 | 454 | 457 | 461 | 462 | Insertion at 447 | |

| Samb-32 | G | A | C | T | G | C | T | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-28 | G | G | C | T | G | C | T | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-30 | T | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-26 | G | G | C | T | G | A | G | T | A | T | – |

| Samb-14 | G | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-5 | G | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-8 | G | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-3 | T | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-9 | T | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-16 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-27 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-35 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-15 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-2 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | – |

| Samb-36 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | – |

| Samb-4 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | – |

| Samb-20 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-17 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-18 | G | G | C | T | A | C | T | G | A | C | T |

| Samb-24 | G | G | C | T | A | C | T | G | A | C | G |

| Samb-19 | G | G | C | T | A | C | T | G | A | T | G |

| Samb-13 | T | G | C | T | A | C | T | G | G | C | T |

| Samb-12 | T | G | G | T | A | C | T | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-29 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-22 | T | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-23 | T | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-21 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-25 | G | G | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | T |

| Samb-37 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | G | T | – |

| Samb-10 | G | A | C | C | G | C | G | G | G | T | – |

| Samb-6 | G | A | C | T | G | C | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-33 | G | A | C | T | G | C | T | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-7 | G | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-31 | G | A | C | T | G | A | G | G | A | T | – |

| Samb-34 | G | A | C | T | G | A | T | T | A | T | – |

| 28 | 20 | 34 | 34 | 30 | 25 | 26 | 33 | 21 | 32 | 23 | |

| SNP/insertion counts | 7 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 14 | 3 | 10 + 2 |

| SNP frequency | 20.00 | 42.86 | 2.86 | 2.86 | 14.29 | 28.57 | 25.71 | 5.71 | 40.00 | 8.57 | 34.28 |

| Total sequence length | 630 bp | ||||||||||

| Total SNPs/insertions | 11 | ||||||||||

| SNP density | I SNP/57.2 bases | ||||||||||

ITS sequences in phylogenetic analysis of S. wightiana

‘Fasttree’, built using online software tool “Clustal W”, with slow NNI and MLACC = 3 based on phylogenetic reconstructions using the function ‘build’ of ETE3 v.3.1.1 was comparable to MEGA 6 results. The optimal tree by MEGA 6 was constructed with the sum of branch length for ITS1 (0.48689146 for NJ and 0.52255238 for UPGMA) and ITS4 (1.61554106 for NJ and 1.80660053 for UPGMA). Both NJ and UPGMA methods show similar results, yet UPGMA showed the best fit results (Suppl S2 and S3). The results didn’t show any geographic-specific clustering among the genotypes.

The sequences of 17 other species of Sambucus and one S. wightiana sequence downloaded from gene bank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) were used as outgroups genotype during the analysis. The cluster analysis led to a clear-cut separation of 17 Sambucus species from S. wightiana (Suppl S4). It is important to note that our genotypes clustered with the out-group S. wightiana genotype sequence downloaded from the gene bank. The results of the present study show the diverse nature of S. wightiana genotypes growing wild in the natural habitats of the North-Western Himalayas.

Structure analysis

The analysis of the population structure of 37 S. wightiana genotypes revealed the presence of two sub-populations (Fig. 3). Sub-population one possesses 17 genotypes, and the second sub-population possesses 20 genotypes. Among 37 genotypes, a set of 4 genotypes were found admixed i.e., their affiliation probability with a particular sub-population is < 80% and these individuals tend to have mixed ancestry and tend to group with different sub-populations. The information of population structure is particularly important for working out marker-trait association and avoiding spurious associations.

Figure 3.

Estimation of the number of groups based on output from STRUCTURE-software (STRUCTURE 2.3.4; https://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structuresoftware/releaseversions/v2.3.4/html/structure.html). (a) ΔK over K from 1 to 10 with the 8 SSR markers. (b) Bar plot showing grouping of 37 genotypes into two different groups.

Marker-trait associations (MTAs)

The study of MTAs using the General Linear Model (GLM) and Mixed Linear Model (MLM) was analyzed in the software program TASSEL led to the identification of a total of 5 SSR markers associated with 11 traits in S. wightiana. Through GLM, one allele/marker each was found associated with plant height, leaf weight, and INL, two alleles/markers with RGR, stem weight, plant weight, MSL, MA, and TL, and three alleles/markers with fruit weight and rhizome weight. Marker SN-04 was found associated with 8 traits, marker SN-07 was found associated with three traits, marker SN-08 was found associated with 5 traits, marker SN-12 with 3 traits, and marker SN-06 with only one trait (Table 8), while as through MLM approach, only one marker (SN-12) was found associated with two different traits (stem weight and fruit weight). The marker SN-12 found associated with 3 traits through GLM and two traits through MLM is the most important marker/genomic loci for S. wightiana.

Table 8.

Association of marker alleles with phenotypic traits using GLM and MLM.

| S. No | Trait | Marker | Allele | F ratio | P value | R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLM | ||||||

| 1 | Height | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 8.098 | 0.0015 | 29.1360 |

| 2 | RGR | SN_7 | SN_7.3 | 6.414 | 0.0047 | 25.5010 |

| SN_8 | SN_8.2 | 6.524 | 0.0043 | 25.8085 | ||

| 3 | Rhizome weight | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 7.583 | 0.0021 | 25.8065 |

| SN_8 | SN_8.3 | 5.868 | 0.0069 | 21.5713 | ||

| SN_12 | SN_12.6 | 7.710 | 0.0091 | 15.2519 | ||

| 4 | Stem weight | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 8.767 | 0.0010 | 29.2205 |

| SN_7 | SN_7.3 | 7.017 | 0.0031 | 25.2056 | ||

| SN_7.4 | 6.536 | 0.0043 | 23.9905 | |||

| SN_7.5 | 7.074 | 0.0029 | 25.3467 | |||

| 5 | Leaf weight | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 5.729 | 0.0076 | 20.8308 |

| 6 | Fruit weight | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 6.471 | 0.0045 | 22.2525 |

| SN_8 | SN_8.3 | 6.353 | 0.0049 | 21.9648 | ||

| SN_12 | SN_12.6 | 10.185 | 0.0032 | 18.2416 | ||

| 7 | Plant weight | SN_7 | SN_7.4 | 5.872 | 0.0069 | 21.5924 |

| SN_7 | SN_7.5 | 5.385 | 0.0098 | 20.2637 | ||

| 8 | MSL | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 8.550 | 0.0011 | 28.4979 |

| SN_8 | SN_8.3 | 5.530 | 0.0088 | 21.0799 | ||

| 9 | MA | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 5.388 | 0.0098 | 20.5485 |

| SN_12 | SN_12.6 | 9.005 | 0.0052 | 17.4950 | ||

| 10 | TL | SN_4 | SN_4.2 | 10.244 | 0.0004 | 31.7693 |

| SN_8 | SN_8.3 | 5.708 | 0.0078 | 21.4884 | ||

| 11 | INL | SN_6 | SN_6.1 | 6.916 | 0.0033 | 27.4183 |

| MLM | ||||||

| 1 | Stem weight | SN_12 | SN_12.6 | 9.198 | 0.0046 | 24.5906 |

| 2 | Fruit weight | SN_12 | SN_12.6 | 8.848 | 0.0054 | 23.1308 |

With P value = < 0.01.

Discussion

Type of reproduction has an important effect on the maintenance of particular populations and species persistence in time and space. This trait significantly influences the ecological and genetic structure of populations and in consequence the evolution of species29. The prevailing opinion is that clonality reduces genetic diversity30. Many studies document lower levels of genetic variation in clonal species preceding repeated genetic bottlenecks leading to a prolonged lag phase31,32 and in populations of such species extinction is prevented with more intense vegetative reproduction with extensive human-mediated propagule dispersal33–36. In contrast to this opinion, comparable, or even higher genetic variation for 21 clonal plant species has been documented than non-clonal ones37. The results of many other studies also confirm this assertion, concerning the high level of genetic variation and genotypic diversity of species with clonal reproduction35,38,39. The most plausible explanation for high levels of genetic variation in populations of clonal plants is the presence of gene flow via long-distance dispersal and multiple introductions reducing the ecological and environmental constraints on genetic diversity whereas enhancing the potential of sexual reproduction, even if it is periodic and meagre40–43. Thus clonality helps in the maintenance and expansion of existing populations while the occurrence of sexual reproduction helps in the recruitment of new individuals/ populations however maintaining the genetic diversity44. Clonal plants are more successful in heterogeneous environments benefiting from clonal integration, which may enhance sexual fitness45. However, clonality does not substitute sexual mode of reproduction and genetic rather than ecological factors prove crucial for long term success46–48.

The well-known genetic paradox of how spreading species maintain genetic diversity despite going through founder effects and genetic bottlenecks during the range expansion49. However, some studies have shown spreading plant species can maintain a remarkable level of genetic diversity across distances, in such cases the gene flow via long-range seed dispersal or pollen might be more important than commonly suggested50,51. This may be also associated with the multiple introductions leading to diverse genetic admixtures52–56. Local adaptation to environmental conditions is also considered one among the other dependent factors providing an advantage to spreading species57–62. Genetic variation plays important role in the evolution-related traits for local adaptation63. Also, evolutionary modifications to reproductive systems provide the spreading capability for widespread species64.

The non-availability of any data on genetic diversity and the aggressive clonal nature led to the perception of low diversity in S. wightiana. Against the anticipated low genetic diversity in clonal plants, S. wightiana showed a remarkable genetic diversity which is consistent with some other studies65,66. The number of alleles per marker is a good indicator of genetic variability67. The detection of 73 alleles in 37 S. wightiana genotypes by 8 SSR primers with 70.59 percent polymorphic loci indicates moderate to high levels of genetic diversity. The high value of average gene diversity for all polymorphic loci (He = 0.74) also points to a good amount of overall genetic variability. Also, the variable ITS regions are used as a standard to measure genetic variability for a long time. The identification of several SNPs among different S. wightiana genotypes with SNP density of 1 SNP/57.2 bp also indicates high diversity in S. wightiana at the sequence level. The present study revealed a good magnitude of genetic diversity and a moderate differentiation with no geographical pattern among populations68.

Our study does not find any geographically distinct clustering of S. wightiana individuals from both clusterings, PCoA by SSR scores and phylogeny by ITS markers69. This can be attributed to the mixing of the genotypes across the regions via gene flow between populations70. AMOVA showed that most of the variation is due to individuals/ genotypes only i.e., 90 percent and only 10 percent of the variation between geographically distant populations. These results suggest the recruitment of new genotypes into the populations with equivalent genetic differentiation as of non-clonal species. Yet clonality remains a vital strategy, shown by the deviance from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for the studied microsatellite loci71. Clonality associated with perineal growth can moderate the negative effects of stochastic population events like genetic drifts, etc.72. This magnitude of polymorphism at the studied microsatellite loci and the resultant genetic diversity may point to the spreading success of this clonal species. The potential for both sexual and clonal reproduction of a species provides the greater ability for landscape spread47. Significant pairwise Fst values (0.125–0.417) were observed which agree with the Nei’s genetic distance and identity parameters, indicating the substantial differentiation between the populations73.

The structure analysis using SSR marker data during the present study revealed different sub-populations (two sub-populations) in our collection of 37 S. wightiana genotypes. The presence of two sub-populations indicated differences in allele frequency and population differentiations in different sub-populations, indicating a good diversity available in S. wightiana genotypes in the Western Himalayas. The analysis of genotypic data in combination with trait data of the traits led to the identification of genomic loci/genomic regions that are associated with these traits. Using different models (GLM and MLM) 5 markers/loci were found associated with 11 traits, with some markers controlling more than one trait (pleiotropy). The markers controlling more than one trait are considered the most important markers/genomic loci and may be due to pleiotropy or linkage of multiple genes. Identification of more genomic loci through GLM than MLM is attributed to more stringent criteria and incorporation of kin-ship matrix into the analysis in MLM, in addition to genotypic data, trait data, and population structure matrix. In GLM association analysis, only genotypic data, trait data, and population structural matrix are used to work out MTAs. The genes/genomic regions/loci identified will prove useful in future Sambucus breeding programs and provided insights into the genetics of these traits and the kind of gene action in Sambucus.

Conclusion

Clonal endemic plant species like S. wightiana can acquire a moderate amount of genetic diversity, creating a wider genetic base that can withstand the stress environments like the conditions created by changing climate of the North-Western Himalaya. In this study, no particular genotype was found dominant across the regions. Lack of correlation between genetic diversity and geographic distances in S. wightiana could be associated with successful sexual reproduction between genets followed by long-range seed dispersion by human or animal agents, and subsequent recruitment in isolated S. wightiana populations enabling the gene flow between populations and forming diverse genetic admixtures74. The present study also found the successful transferability of these microsatellite markers, which could be used for further studies at a finer scale.

Methods

Plant species

Sambucus wightiana Wall. Ex Wight & Arn. is a clonal sub-shrub, mostly found in the forests of Kashmir valley within an altitudinal range of 1700–3300 m.a.s.l. Commonly called Kashmir elder, the species is a rhizomatous geophyte growing up to 2 m in height with white or yellowish-white flowers. The umbels consist of orange or red individual berries that reach full ripeness in late summer. The species is native to the North-Western Himalaya and the primary range spans from Indian administered Kashmir to Chitral in Pakistan75. Recently the species has been reported from other parts of the Indian Himalayas like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim76, pointing towards its spread due to adaptive evolution in response to climate change61. Sambucus wightiana is closely allied to S. adnata Wall., from which it differs in its glabrous or almost glabrous inflorescence.

Study area

The present study was carried out in the Kashmir Himalaya (32° 20′ to 34° 54′ N and 73° 55′ to 75° 35′ E, total area of 15,948 km2), that represents a unique biogeographical province in the Indian Himalayan region77. The altitude of the region ranges from 1600 m.a.s.l. at Srinagar to 5420 m.a.s.l. at Kolahoi peak. Within this altitudinal range, Kashmir elder is found from 1700 to 3300 m.a.s.l. in the forests of Kashmir valley. The climate of the region is predominantly of a continental temperate type with wet and cold winters and relatively dry and hot summers. The temperature ranges from an average daily maximum of 31 °C and minimum of 15 °C during summer to an average daily maximum of 4 °C and minimum of − 4 °C during winter. The region has been reported to be a hotspot for climate change due to its complex topography, enormous glacial and water resources, and quick responding watersheds with intense seasonal and climatic variability over a small spatial scale78.

For the present study, we sampled 37 S. wightiana individuals (Table 9) from seven watersheds (Vishaw, Ferozpur, Lidder, Sindh, Doodhganga, Pohru, and Brinji) across Kashmir Himalaya, aiming to cover a wide geographic area and range of elevations (Fig. 4). The samples from each watershed were clubbed as populations for further analysis.

Table 9.

Description of the sampling sites.

| Sub-populationsa | Sampling site | Sample code | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (m.a.s.l.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vishav (Pop1) | Sedow Forest | Samb-1 | 33° 40.226′ | 74° 49.281′ | 2279 |

| Sagum Aharbal | Samb-2 | 33° 37.537′ | 74° 46.369′ | 2365 | |

| Aharbal | Samb-3 | 33° 39.099′ | 74° 47.188′ | 2258 | |

| Nandimarg | Samb-4 | 33° 33.354′ | 74° 56.186′ | 2280 | |

| Awil | Samb-5 | 33° 36.580′ | 74° 52.471′ | 2066 | |

| Dather | Samb-6 | 33° 33.425′ | 75° 00.341′ | 2070 | |

| Sedow | Samb-7 | 33° 39.574′ | 74° 46.729′ | 2390 | |

| Sagum Aharbal | Samb-36 | 33° 37.900′ | 74° 46.354′ | 2344 | |

| Sagum Aharbal | Samb-37 | 33° 37.900′ | 74° 46.354′ | 2341 | |

| Ferozpur (Pop2) | Khilanmarg | Samb-8 | 34° 1.9572′ | 74° 22.0194′ | 3076 |

| Khilanmarg | Samb-9 | 34° 1.9572′ | 74° 22.0194′ | 3076 | |

| Khilanmarg | Samb-14 | 34° 1.8706′ | 74° 22.080′ | 3042 | |

| Gulmarg | Samb-15 | 34° 3.1098′ | 74° 20.3683′ | 2704 | |

| Tangmarg | Samb-16 | 34° 3.5978′ | 74° 25.6727′ | 2150 | |

| Lidder (Pop3) | Mandlan | Samb-12 | 34° 04.545′ | 75° 16.147′ | 2351 |

| Mandlan | Samb-13 | 34° 04.545′ | 75° 16.147′ | 2351 | |

| Chandanwari | Samb-17 | 34° 04.807′ | 75° 25.102′ | 2986 | |

| Aru | Samb-18 | 34° 05.660′ | 75° 15.954′ | 2456 | |

| Lidroo | Samb-19 | 33° 57.422′ | 75° 18.319′ | 2030 | |

| Hapatnar | Samb-20 | 33° 50.031′ | 75° 20.194′ | 2070 | |

| Langanbal | Samb-21 | 33° 58.053′ | 75° 18.506′ | 2022 | |

| Laddi | Samb-22 | 33° 56.143′ | 75° 16.930′ | 2002 | |

| Sindh (Pop4) | Hungpark Gagangair | Samb-10 | 34° 17.719′ | 75° 13.780′ | 2508 |

| Hungpark Gagangair | Samb-11 | 34° 17.719′ | 75° 13.780′ | 2508 | |

| Wangat | Samb-23 | 34° 19.657′ | 74° 57.142′ | 2090 | |

| Pathkhanan | Samb-24 | 34° 19.044′ | 74° 56.662′ | 2048 | |

| Burnabugh | Samb-25 | 34° 17.959′ | 74° 55.680′ | 2072 | |

| Prang | Samb-26 | 34° 16.836′ | 74° 52.295′ | 1723 | |

| Forest Check Point Gagangair | Samb-27 | 34° 17.957′ | 75° 12.832′ | 2424 | |

| Naranag | Samb-28 | 34° 35.236′ | 74° 97.484′ | 2271 | |

| Doodhganga (Pop5) | RaithanTraja-Khal | Samb-29 | 33° 52.897′ | 74° 37.733′ | 2674 |

| Dangerpora Doodhpathri | Samb-30 | 33° 51.905′ | 74° 34.202′ | 2780 | |

| Doodhpathri | Samb-31 | 33° 50.567′ | 74° 34.202′ | 2883 | |

| Pohru (Pop6) | Chokibal | Samb-32 | 34° 25.311′ | 73° 59.162′ | 2215 |

| Chokibal TP | Samb-33 | 34° 24.097′ | 73° 54.337′ | 2291 | |

| Brinji (Pop7) | Vailoo | Samb-34 | 33° 33.956′ | 75° 21.905′ | 2083 |

| Daksum | Samb-35 | 33° 36.672′ | 75° 26.469′ | 2410 |

aBased on the geographic location, all the samples from nearby locations were clubbed as populations for analysis.

Figure 4.

Study area showing sampling sites marked as black dots on the map inset (ArcGIS 10.2; http://resources.arcgis.com/en/help/main/10.2/index.html).

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from the freshly collected young foliar parts of 37 S. wightiana accessions/genotypes by Qiagen® DNeasy™ Plant mini kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and concentration of the DNA were determined by visual comparison with the known amount of λ DNA on 0.8% agarose gel.

Selection of SSR markers and PCR amplification

Eight polymorphic microsatellite (SSR) markers, previously developed from the S. nigra genome (EMSn002, 003, 010, 016, 017, 019 023, and 025) were selected, which have also been found informative in Sambucus canadensis79 (Table 1). Their sequences were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). The primers for these eight SSR markers were synthesized on contract from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore, India. The PCR was carried out in 15 µL reaction volume with the constituents: 2 µL 20 ng DNA template, 2µL (5.0 pmol) forward and reverse primers, 0.4 µL (2.5 mM) dNTPs, 0.3 µL (1.5 U) Taq Polymerase (Sigma), 1.5 µL buffer containing MgCl2 with a PCR profile of; 5 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 54 °C for 1 min 30 S of annealing temperature, 72 for 1 min and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min in a Peqlab PCR machine.

Selection of ITS1 and ITS4 primer sequences and their PCR

In addition to SSR markers, the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA region was amplified using primers (ITS1: 5-GTCCACTGAACCTTATCATTTAG-3 and ITS-4: 5-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3) synthesized on contract from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore (for more details about primer see Choudhary et al. 2018). The PCR was done in a 25 µL reaction volume with the following constituents: 25 ng DNA template, 5.0 pmol forward and reverse primers, 2.5 mM of each dNTPs, 1X buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, and 1.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma) by using the following PCR profile; 5 min at 94 °C, 45 cycles of 94 °C for 30 S, 52 °C for 45 S of annealing temperature, 72 °C for 1 min and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min in a Peqlab PCR machine.

Agarose/poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)

After successful amplification, the PCR products of both ITS1–ITS4 markers and all the eight SSR markers were tested on 1.6% agarose gel to check for any amplification errors and robustness of amplification (Suppl S1a). Amplification of ITS led to a single conspicuous band of about 750 bp. The PCR product was cleaned, and Sanger sequenced by ABI 3730xl sequencer at SciGenome Genomic Services facility, Cochin, Kerala (www.scigenome.com). All SSR amplifications for 37 S. wightiana genotypes were subjected to PAGE analysis using PeqLab Perfect Blue Dual Gel Vertical Electrophoresis system. The gels were silver stained and digitally photographed (Suppl S1b) and the data were scored manually.

SSR marker data analysis

For the characterization of genetic variation in the 37 S. wightiana genotypes and to test the transferable use of the microsatellite markers, a set of 8 SSR markers were selected. Out of the 8 SSR primers, 6 primers were polymorphic. Primers EMSn0023 and 0025 amplified a single monomorphic band. To determine the various parameters of genetic diversity, different software packages and online tools were used. The SSR marker data scored were analyzed using the software program DARwin ver. 6.0 (http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin) 80, for multivariate analysis (clustering and PCoA). Both clustering and PCoA were based on Jaccard’s dissimilarity co-efficient with 1000 bootstraps. Two clustering methods (UPGMA Hierarchical clustering and Neighbor-Joining clustering) were followed. The final inferences were made on the Unweighted Neighbor-Joining clustering (UNJ), which provided the best fit to the data, and a dendrogram was constructed81.

Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) based on 999 permutations using FST statistics was performed with the scored SSR fragment lengths (8 markers at 17 loci) to determine the segregation of total genetic variation between, among, and within populations using GenAlEx v.6.5 (https://biology-assets.anu.edu.au/GenAlEx/Welcome.html)82. The parameters included the number of alleles for a given locus (N), Number of effective alleles (Ne), Shannon’s Information Index (I), Observed Heterozygosity (Ho), Expected Heterozygosity (He), Unbiased Expected Heterozygosity (uHe), and Fixation Index (F) along with their mean and Standard Error (SE). GenAlEx was also used to calculate the mean allelic patterns across the populations with the above-mentioned parameters.

Since our study was confined to a small number of samples, pairwise Nei’s Genetic Distance, Nei’s Genetic identity, and corresponding unbiased Nei’s Genetic Distance and Nei’s Genetic identity values were calculated across populations83,84. Also, Chi-Square Tests for Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium were implemented in GenAlEx v.6.5. The Polymorphism Information Content (PIC) values of individual primers at all loci were calculated based on the formula PIC = 2 × F (1 − F)85.

An analysis of population structure was done using the software STRUCTURE v.2.3.4 (https://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structure_software/release_versions/v2.3.4/html/structure.html)86. Population structure was analyzed by setting the number of sub-populations (k-values) from 1 to 10 and each run was repeated five times. The program was set to 300,000 burn-in iterations, followed by 600,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) replications along with the admixture model. The STRUCTURE HARVESTER web version v0.6.94 (http://taylor0.biology.ucla.edu/structureHarvester/)87 was used to derive the appropriate number of sub-populations using a modified delta K (∆K) method88.

A study of Marker-Trait Associations (MTAs) was done using genotypic data, trait data, and population structure information using General Linear Models (GLM), and Mixed-Linear Model (MLM) in the software program TASSEL (https://tassel.bitbucket.io/)89. Kinship matrix was also used in addition to genotypic data, trait data, and population structure information. The kinship matrix was calculated from genotypic data using the software program TASSEL.

Analysis of ITS1–ITS4 Sanger sequencing data

The Sanger sequences of ITS1 and ITS4 were manually checked for sequencing errors. The sequences were aligned using the online ClustalW tool (http://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) and phylogenetic reconstructions were performed using the function ‘build’ in ETE3 v.3.1.190, as implemented on the GenomeNet (http://www.genome.jp/tools/ete/). The tree was constructed using the function ‘fasttree’ with slow NNI and MLACC = 3 (to make the maximum-likelihood NNIs more exhaustive)91. The values at nodes are SH-like local support. To compare these tree results for validity and reliability, MEGA 6 (Build#: 6140226; https://www.megasoftware.net/)92 was also used for tree construction. The evolutionary history was inferred using the UPGMA method93 and Neighbor-Joining method94. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method95 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches96. Codon positions included were 1st + 2nd + 3rd + Noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 528 and 537 positions for ITS1 and ITS4 respectively in the final dataset. Also, the aligned sequences of all 37 accessions were analyzed in BioEdit v.7.2.6 (http://en.bio-soft.net/format/BioEdit.html)97,98 for SNP identification.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The financial support under No. 14/79/2013-RE provided to IR and ZAR by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change (MOEFCC), New Delhi is acknowledged. R.R. Mir is highly thankful to Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Govt. of India for providing funds under “Young Investigator Award” with grand No of SB/FT/LS-355/2012. The authors are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that helped to improve this manuscript.

Author contributions

I.A.S.: Data collection, Writing; I.R.: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition; J.Y.L.: Data collection; S.T.: Formal analysis; Z.A.R.: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition; R.R.M.: Methodology, Formal analysis.

Funding

The financial support under No. 14/79/2013-RE provided to IR and ZAR by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change (MOEFCC), New Delhi is acknowledged.

Data availability

Voucher specimen number 3750-KASH of Sambucus wightiana was deposited in the KASH herbarium of the University of Kashmir, which was identified by the curator, Mr. Akhtar H. Malik. The study complies with the national and international guidelines. Moreover, appropriate permission was obtained for the collection of plant material.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Irfan Rashid, Email: irfanrashid@uok.edu.in.

Reyazul Rouf Mir, Email: rrmir@skuastkashmir.ac.in.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-98648-8.

References

- 1.Chen IC, Hill JK, Ohlemüller R, Roy DB, Thomas CD. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science. 2011;333:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1206432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pecl GT, et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science. 2017;355:6332. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmesan C, Yohe G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature. 2003;421:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiens JJ, Litvinenko Y, Harris L, Jezkova T. Rapid niche shifts in introduced species can be a million times faster than changes among native species and ten times faster than climate change. J. Biogeogr. 2019;46:2115–2125. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estrada A, Morales-Castilla I, Caplat P, Early R. Usefulness of species traits in predicting range shifts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016;31:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLean SA, Beissinger SR. Species’ traits as predictors of range shifts under contemporary climate change: A review and meta-analysis. Global Chang. Biol. 2017;23:4094–4105. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler, E. & Fischer, M. The role of vegetative spread and seed dispersal for optimal life histories of clonal plants: A simulation study. In Ecology and Evolutionary Biology of Clonal Plants 59–79 (Springer, 2002).

- 8.Neiman M, Meirmans S, Meirmans P. What can asexual lineage age tell us about the maintenance of sex? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1168:185–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steffen W, et al. Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. PNAS. 2018;115:8252–8259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810141115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson TP, Jackson ST, House JI, Prentice IC, Mace GM. Beyond predictions: Biodiversity conservation in a changing climate. Science. 2011;332:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban MC. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science. 2015;348:571–573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann AA, Sgro CM. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature. 2011;470:479–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell G. Evolutionary rescue. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017;48:605–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capblancq T, Fitzpatrick MC, Bay RA, Exposito-Alonso M, Keller SR. Genomic prediction of (Mal) adaptation across current and future climatic landscapes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2020;51:245–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-020720-042553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett RD, Schluter D. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai YT, et al. Standing genetic variation as the predominant source for adaptation of a songbird. PNAS. 2019;116:2152–2157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813597116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonin A, et al. How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetics studies. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:3261–3273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honnay O, Jacquemyn H. A meta-analysis of the relation between mating system, growth form and genotypic diversity in clonal plant species. Evol. Ecol. 2008;22:299–312. doi: 10.1007/s10682-007-9202-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnaud-Haond S, et al. Assessing genetic diversity in clonal organisms: Low diversity or low resolution? Combining power and cost efficiency in selecting markers. J. Hered. 2005;96:434–440. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esi043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe, A. D. & Liston, A. Contributions of PCR-based methods to plant systematics and evolutionary biology. In Molecular systematics of plants II 43–86 (Springer, 1998).

- 21.Nicolè S, et al. Biodiversity studies in Phaseolus species by DNA barcoding. Genome. 2011;54:529–545. doi: 10.1139/g11-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin BG, et al. The ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA: A valuable source of evidence on angiosperm phylogeny. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1995;1:247–277. doi: 10.2307/2399880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Álvarez IJFW, Wendel JF. Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;29:417–434. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhary N, et al. Insight into the origin of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) grown in the state of Jammu and Kashmir of North-Western Himalayas. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018;65:963–977. doi: 10.1007/s10722-017-0588-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doh EJ, Kim JH, Oh SE, Lee G. Identification and monitoring of Korean medicines derived from Cinnamomum spp. by using ITS and DNA marker. Genes Genom. 2017;39:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s13258-016-0476-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh SK, Meghwal PR, Pathak R, Bhatt RK, Gautam R. Assessment of genetic diversity among Indian jujube varieties based on nuclear ribosomal DNA and RAPD polymorphism. Agric. Res. 2014;3:218–228. doi: 10.1007/s40003-014-0112-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbatsch LE, Baldwin BG, Donoghue MJ. Phylogeny of the coneflowers and relatives (Heliantheae: Asteraceae) based on nuclear rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences and chlorplast DNA restriction site data. Syst. Bot. 2000;1:539–565. doi: 10.2307/2666695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eriksson T, Donoghue MJ. Phylogenetic relationships of Sambucus and Adoxa (Adoxoideae, Adoxaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences and preliminary morphological data. Syst. Bot. 1997;1:555–573. doi: 10.2307/2419828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrero V, et al. Global patterns of reproductive and cytotype diversity in an invasive clonal plant. Biol. Invasions. 2020;3:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamrick, J. L. & Godt, M. J. Allozyme diversity in plant species. In Plant Population Genetics, Breeding and Genetic Resources 44–64 (Sinauer Associates Inc, 1989).

- 31.Lee CE. Evolutionary genetics of invasive species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002;17:386–391. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02554-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crooks JA. Lag times and exotic species: The ecology and management of biological invasions in slow-motion1. Ecoscience. 2005;12:316–329. doi: 10.2980/i1195-6860-12-3-316.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peakall R, Beattie AJ. The genetic consequences of worker ant pollination in a self-compatible, clonal orchid. Evolution. 1991;45:1837–1848. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sydes MA, Peakall ROD. Extensive clonality in the endangered shrub Haloragodendron lucasii (Haloragaceae) revealed by allozymes and RAPDs. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00314.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brzosko E, Wróblewska A, Tałałaj I, Wasilewska E. Genetic diversity of Cypripedium calceolus in Poland. Plant Syst. Evol. 2011;295:83–96. doi: 10.1007/s00606-011-0464-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerra-García A, Golubov J, Mandujano MC. Invasion of Kalanchoe by clonal spread. Biol. Invasions. 2015;17:1615–1622. doi: 10.1007/s10530-014-0820-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellstrand NC, Roose ML. Patterns of genotypic diversity in clonal plant species. Am. J. Bot. 1987;74:123–131. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1987.tb08586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung MG, Epperson BK. Spatial genetic structure of clonal and sexual reproduction in populations of Adenophora grandiflora (Campanulaceae) Evolution. 1999;53:1068–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stehlik I, Holderegger R. Spatial genetic structure and clonal diversity of Anemone nemorosa in late successional deciduous woodlands of Central Europe. J. Ecol. 2000;88:424–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00458.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudoh H, Shibaike H, Takasu H, Whigham DF, Kawano S. Genet structure and determinants of clonal structure in a temperate deciduous woodland herb, Uvularia perfoliata. J. Ecol. 1999;87:244–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.1999.00355.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pornon A, Escaravage N, Thomas P, Taberlet P. Dynamics of genotypic structure in clonal Rhododendron ferrugineum (Ericaceae) populations. Mol. Ecol. 2000;9:1099–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brzosko E, Wróblewska A, Ratkiewicz M. Spatial genetic structure and clonal diversity of island populations of lady's slipper (Cypripedium calceolus) from the Biebrza National Park (northeast Poland) Mol. Ecol. 2002;11:2499–2509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AL, et al. Global gene flow releases invasive plants from environmental constraints on genetic diversity. PNAS. 2020;117:4218–4227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915848117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong MEI, Lu BR, Zhang HB, Chen JK, Li BO. Role of sexual reproduction in the spread of an invasive clonal plant Solidago canadensis revealed using intersimple sequence repeat markers. Plant Species Biol. 2006;21:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-1984.2006.00146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.You W, Fan S, Yu D, Xie D, Liu C. An invasive clonal plant benefits from clonal integration more than a co-occurring native plant in nutrient-patchy and competitive environments. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silvertown J. The evolutionary maintenance of sexual reproduction: Evidence from the ecological distribution of asexual reproduction in clonal plants. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2008;169:157–168. doi: 10.1086/523357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vallejo-Marín M, Dorken ME, Barrett SC. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of clonality for plant mating. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010;41:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uesugi A, Baker DJ, de Silva N, Nurkowski K, Hodgins KA. A lack of genetically compatible mates constrains the spread of an invasive weed. New Phytol. 2020;226:1864–1872. doi: 10.1111/nph.16496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allendorf FW, Lundquist LL. Introduction: Population biology, evolution, and control of invasive species. Conserv. Biol. 2003;1:24–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02365.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pluess AR, Stöcklin J. Population genetic diversity of the clonal plant Geum reptans (Rosaceae) in the Swiss Alps. Am. J. Bot. 2004;91:2013–2021. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.12.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bialozyt R, Ziegenhagen B, Petit RJ. Contrasting effects of long distance seed dispersal on genetic diversity during range expansion. J. Evol. Biol. 2006;19:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colautti RI, Grigorovich IA, MacIsaac HJ. Propagule pressure: A null model for biological invasions. Biol. Invasions. 2006;8:1023–1037. doi: 10.1007/s10530-005-3735-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roman J, Darling JA. Paradox lost: Genetic diversity and the success of aquatic invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dlugosch KM, Parker IM. Founding events in species invasions: Genetic variation, adaptive evolution, and the role of multiple introductions. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:431–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirk RY, Hamrick JL, Zhang C, Qiang S. Patterns of genetic diversity reveal multiple introductions and recurrent founder effects during range expansion in invasive populations of Geranium carolinianum (Geraniaceae) Heredity. 2014;112:497–507. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nobarinezhad MH, Challagundla L, Wallace LE. Small-scale population connectivity and genetic structure in Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) Int. J. Plant Sci. 2020;181:473–484. doi: 10.1086/706882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakai AK, et al. The population biology of invasive species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2001;32:305–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maron JL, Vilà M, Bommarco R, Elmendorf S, Beardsley P. Rapid evolution of an invasive plant. Ecol. Monogr. 2004;74:261–280. doi: 10.1890/03-4027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bossdorf O, et al. Phenotypic and genetic differentiation between native and introduced plant populations. Oecologia. 2005;144:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0070-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montague JL, Barrett SCH, Eckert CG. Re-establishment of clinal variation in flowering time among introduced populations of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria, Lythraceae) J. Evol. Biol. 2008;21:234–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prentis PJ, Wilson JR, Dormontt EE, Richardson DM, Lowe AJ. Adaptive evolution in invasive species. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colautti RI, Maron JL, Barrett SC. Common garden comparisons of native and introduced plant populations: Latitudinal clines can obscure evolutionary inferences. Evol. Appl. 2009;2:187–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colautti RI, Eckert CG, Barrett SC. Evolutionary constraints on adaptive evolution during range expansion in an invasive plant. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2010;277:1799–1806. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barrett SC, Colautti RI, Eckert CG. Plant reproductive systems and evolution during biological invasion. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:373–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pappert RA, Hamrick JL, Donovan LA. Genetic variation in Pueraria lobata (Fabaceae), an introduced, clonal, invasive plant of the southeastern United States. Am. J. Bot. 2000;87:1240–1245. doi: 10.2307/2656716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duchoslav M, Staňková H. Population genetic structure and clonal diversity of Allium oleraceum (Amaryllidaceae), a polyploid geophyte with common asexual but variable sexual reproduction. Folia Geobot. 2015;50:123–136. doi: 10.1007/s12224-015-9213-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nevo E. Genetic variation in natural populations: Patterns and theory. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1978;13:121–177. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(78)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gargiulo R, Ilves A, Kaart T, Fay MF, Kull T. High genetic diversity in a threatened clonal species, Cypripedium calceolus (Orchidaceae), enables long-term stability of the species in different biogeographical regions in Estonia. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2018;186:560–571. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/box105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xia L, Geng Q, An S. Rapid genetic divergence of an invasive species, Spartina alterniflora, in China. Front. Genet. 2020;11:284. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosenthal DM, Ramakrishnan AP, Cruzan MB. Evidence for multiple sources of invasion and intraspecific hybridization in Brachypodium sylvaticum (Hudson) Beauv, North America. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:4657–4669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lembicz M, et al. Microsatellite identification of ramet genotypes in a clonal plant with phalanx growth: The case of Cirsium rivulare (Asteraceae) Flora. 2011;206:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2011.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Young A, Boyle T, Brown T. The population genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation for plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:413–418. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lucardi RD, Wallace LE, Ervin GN. Patterns of genetic diversity in highly invasive species: Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) expansion in the invaded range of the southern United States (US) Plants. 2020;9:423. doi: 10.3390/plants9040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barbosa C, Trevisan R, Estevinho TF, Castellani TT, Silva-Pereira V. Multiple introductions and efficient propagule dispersion can lead to high genetic variability in an invasive clonal species. Biol. Invasions. 2019;21:3427–3438. doi: 10.1007/s10530-019-02057-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hutchinson J. Notes on the Indian species of Sambucus. Bull. Misc. Inf. 1909;1909:191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Acharya J, Mukherjee A. An account of Sambucus L. in the Himalayan regions of India. Indian J. Life Sci. 2014;4:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodgers WA, Panwar SH. Biogeographical Classification of India. New Forest; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shafiq MU, Rasool R, Ahmed P, Dimri AP. Temperature and precipitation trends in Kashmir Valley, North Western Himalayas. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019;135:293–304. doi: 10.1007/s00704-018-2377-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Clarke JB, Tobutt KR. Development of microsatellite primers and two multiplex polymerase chain reactions for the common elder (Sambucus nigra) Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:453–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01270.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DARwin software v. 6.0. http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin (2006).

- 81.Gascuel O. Concerning the NJ algorithm and its unweighted version, UNJ. Math. Hierarchies Biol. 1997;37:149–171. doi: 10.1090/dimacs/037/09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peakall ROD, Smouse PE. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. Am. Nat. 1972;106:283–292. doi: 10.1086/282771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89:583–590. doi: 10.1093/genetics/89.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anderson JA, Churchill GA, Autrique JE, Tanksley SD, Sorrells ME. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome. 1993;36:181–186. doi: 10.1139/g93-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pritchard JK, Wen X, Falush D. Documentation for STRUCTURE Software, Version 2.3. University of Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Earl DA. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012;4:359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bradbury PJ, et al. TASSEL: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2633–2635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huerta-Cepas J, Serra F, Bork P. ETE 3: Reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of phylogenomic data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1635–1638. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sneath PH, Sokal RR. Numerical Taxonomy. The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. W.H. Freeman and Company; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. PNAS. 2004;101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hall, T. A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. In Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 95–98 (Information Retrieval Ltd., c1979–c2000 1999).

- 98.Hall T, Biosciences I, Carlsbad C. BioEdit: An important software for molecular biology. GERF Bull. Biosci. 2011;2:60–61. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Voucher specimen number 3750-KASH of Sambucus wightiana was deposited in the KASH herbarium of the University of Kashmir, which was identified by the curator, Mr. Akhtar H. Malik. The study complies with the national and international guidelines. Moreover, appropriate permission was obtained for the collection of plant material.