Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia worldwide, yet the dearth of readily accessible diagnostic biomarkers is a substantial hindrance towards progressing to effective preventive and therapeutic approaches. Due to a long delay between cerebral amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation and the onset of cognitive impairments, biomarkers that reflect Aβ pathology and enable routine screening for disease progression are of urgent need for application in the clinical diagnosis of AD. According to accumulating evidences, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma offer windows to the brain as they allow monitoring of biochemical changes in the brain. Considering the high availability and accuracy in depicting Aβ deposition in the brain, Aβ levels in CSF and plasma are regarded as promising fluid biomarkers for the diagnosis of AD patients at an early stage. However, clinical data with intra- and interindividual variations in the concentrations of CSF and plasma Aβ implicate the need to reevaluate current Aβ detection methods and establish a standardized operating procedure. Therefore, this review introduces three bias-generating factors in biofluid Aβ measurement that may hamper the accurate Aβ quantification and how such complications can be overcome for the widespread implementation of fluid Aβ detection in clinical practice.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid-β, Cerebrospinal fluid, Plasma, Fluid biomarker

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the misfolding of amyloid-β (Aβ) in the brain, leading to a progressive decline in learning and memory [1]. Aβ is an enzymatic cleavage product of amyloid precursor protein (APP), which can be processed in one of the two pathways: nonamyloidogenic or amyloidogenic pathway. The nonamyloidogenic processing of APP involves cleavage by α-secretase followed by γ-secretase, and the products of this pathway are widely believed to be non-pathogenic and possess no significant physiological function [2]. On the other hand, the amyloidogenic pathway occurs through the sequential cleavage by β-secretase and γ-secretase, generating Aβ peptides that are 36–43 amino acids in length [3]. Among varied Aβ species, Aβ40 is the most abundant form, while Aβ42 is the aggregation-prone, neurotoxic species [4, 5]. During the early stages of AD, Aβ oligomers are formed, which aggregate further into protofibrils and fibrils, eventually forming insoluble senile plaques [6]. Accumulation of Aβ plaques impairs surrounding dendritic spines as a result of altered structural plasticity and disrupts synaptic transmission by enhancing synaptic depression, resulting in synaptic dysfunction [7, 8]. Aggregation of Aβ also increases reactive oxidative stress, leading to plaque-associated microglial infiltration and initiation of local inflammatory responses. Chronic glial activation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines contribute to increased neurotoxicity [9, 10]. Consequently, these detrimental effects of Aβ aggregation are strongly associated with the learning and memory impairments in AD, making Aβ a core candidate biomarker [5]. In addition to insoluble Aβ plaques, soluble oligomers are regarded as highly toxic and pathogenic forms of Aβ. Aβ oligomers are fibril-free Aβ structures found in the earlier stages of AD pathogenesis, and their levels are elevated in both AD mouse models and human patients. Aβ oligomers induce plasticity dysfunction, synapse deterioration, and oxidative stress, accounting for the onset of neuronal damage leading to AD [11]. The ameliorative effects of Aβ oligomer-specific antibodies on cognitive dysfunctions in transgenic AD mouse models further provide supporting evidence on the critical role of oligomeric Aβ on the pathogenesis and progression of AD [12, 13]. Therefore, Aβ oligomers can be considered as a potential target of early diagnosis.

Significant advances in the understanding of AD pathogenesis and the development of noninvasive imaging technologies promoted the employment of brain imaging modalities and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers in the diagnosis of AD [14, 15]. Brain imaging methods currently available for AD diagnosis include fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET), amyloid-PET, tau-PET, and structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). FDG-PET assesses the spatial distribution of glucose metabolism and detects functional brain changes, and amyloid-PET scans are used to distinguish AD from other forms of dementia, with specificity for the detection of Aβ deposits using Aβ plaque-associated radioligands [16, 17]. Tau-PET specifically detects neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, another molecular hallmark of AD [18]. Structural and functional MRI are utilized to provide information on the neurodegenerative aspect of AD through the characterization of brain atrophy and connectivity [19–21]. However, the high economic burden and limited accessibility of these imaging technologies leave a large proportion of worldwide AD patients diagnosed late or not at all [22].

In contrast, fluid biomarkers are credible indicators of AD with distinct advantages compared to brain imaging in affordability and accessibility. As CSF is in direct contact with the extracellular space of the brain, the biochemical changes in the brain are reflected in the CSF, making it a reliable source of biomarkers [23, 24]. In fact, the correlation between the levels of CSF Aβ and amyloid deposition in the brain facilitated CSF Aβ quantification to be incorporated into the standard diagnostic guidelines for AD [25–31]. Among the different isoforms of Aβ found in CSF, the ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 concentrations is considered to be more effective than Aβ42 level alone in identifying AD patients [32]. However, for Aβ quantification to be readily utilized as a regular screening method for preclinical AD, a more accessible and less invasive method is necessary. This makes plasma Aβ detection highly attractive for clinical application. Across the blood–brain barrier, Aβ in the brain can be transported to and from the blood by the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 and the receptor for advanced glycation end products, respectively, allowing the measurement of Aβ in the plasma separated from the blood [33, 34]. In addition to higher accessibility and cost-efficiency, clinical evidences demonstrating the capability of plasma Aβ level to successfully mirror amyloid deposition in the brain assessed by amyloid-PET scans make plasma Aβ concentration a promising candidate biomarker for early disease diagnosis [35].

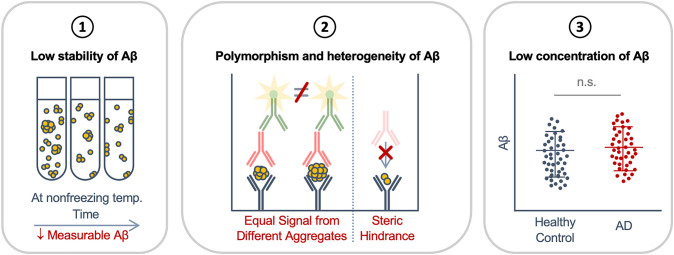

However, even with continuous efforts to integrate CSF and plasma Aβ quantification in AD diagnosis, they are not yet widely accepted for routine clinical practice. One of the main reasons behind this is the high variability between the levels of Aβ measured in different studies. Such interassay and interlaboratory discrepancies are due to the lack of universal protocols with standardized preanalytical factors linked to sample collection, handling and processing, and analytical factors involving Aβ detection mechanisms. In this review, we discuss three bias-generating elements of CSF and plasma Aβ detection that may affect Aβ quantification (Fig. 1) and how these complications can be resolved for the accurate measurement of Aβ concentration in these samples (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Bias-generating factors in the measurement of CSF and plasma Aβ for AD diagnosis. (1) The low stability of Aβ complicates the accurate quantification of Aβ level. Storage of Aβ-containing sample at nonfreezing temperatures for an extended period of time may lead to reductions in the amount of measurable Aβ due to degradation of Aβ within the samples and adsorption of Aβ to the surfaces of the tube. (2) The polymorphic and heterogeneous nature of Aβ aggregates in CSF and plasma calls for attention in the measurement of Aβ levels utilizing ELISA or other conventional immunoassays, which are not able to distinguish the different forms of Aβ aggregates or detect low-order oligomers of Aβ due to steric hindrance. (3) Aβ is present at extremely low concentrations in CSF and plasma, which necessitates advanced technology for accurate quantification. temp., temperature; n.s., not significant

Fig. 2.

Recommended protocol of Aβ detection in CSF and plasma. (1) After CSF and blood collection, plasma should be isolated from whole blood immediately after collection, and CSF must be centrifuged and separated if contaminated with blood. The samples must be processed, stored, or analyzed within two hours. (2) Aβ aggregates in CSF and plasma need to be dissociated to obtain homogenous Aβ for the accurate measurement of Aβ level. (3) Ideal quantification of CSF and plasma Aβ requires an ultrasensitive device with a low LOD, identifying the disease stage of the patient among preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, or AD dementia

Low stability of Aβ in CSF and plasma

The time delay in sample acquisition, processing, storage, and analysis is a commonly varied confounding preanalytical factors [36, 37], although it must be cautiously controlled. The delay can significantly alter the measurement of Aβ concentration as a result of protein degradation within CSF and plasma. CSF Aβ concentration is reported to maintain a stable level up to 24 hours at room temperature, while storage of CSF at 4, 18, and 37 °C for two days led to the reduction of Aβ level by at least 20% when compared to that of CSF immediately frozen to − 80 °C after collection [38, 39]. At − 20 °C, CSF Aβ concentration begins to decline after 14 days of storage [40]. In comparison, Aβ level in CSF is stable for up to six years when frozen at − 80 °C immediately after CSF acquisition [41]. For plasma Aβ, the concentration decreases by 26% after 24 hours and by an additional 14% in the next 24 hours of storage at room temperature [42]. Rapid degradation of Aβ in plasma was further supported by another study reporting that Aβ concentration of freshly separated plasma is stable until three hours after centrifugation and decreases by 5% after six hours and 10% after 24 hours. The stability of Aβ in plasma frozen and thawed once was lower, where Aβ concentration decreased by 5–7% after six hours at 4 °C and 15–18% after six hours at room temperature. After 24 hours, 8–10% and 40% reductions were observed at 4 °C and room temperature, respectively. Conversely, plasma Aβ level exhibits stability for more than five years when stored at -80 °C, while storage of plasma at − 20 °C is not appropriate for long-term storage [43, 44]. Aβ level is most unstable in whole blood, where a 24-hour delay between blood draw and plasma separation led to the loss of 50% of the measurable amount of Aβ [45]. The accurate quantification of Aβ from stored samples might also be hindered due to the tendency of Aβ peptides to adsorb to the surfaces of certain types of plastic tubes. Exposure of CSF to polystyrene tubes leads to 20–50% reduction in Aβ concentration due to adherence. As a result, it has been established that polypropylene tubes should be used for CSF collection and storage [46–48]. In the case of blood and plasma samples, polypropylene and polyethylene terephthalate tubes did not result in altered plasma Aβ levels [45].

In addition to the quantification of total Aβ, the measurement of Aβ oligomers may be critical for the accurate diagnosis of AD, considering the toxicity of oligomeric Aβ and its role in the pathogenesis of AD. The CSF and plasma levels of Aβ oligomers correlate well with the severity of amyloid deposition in the brain and the degree of cognitive impairments measured by the Mini-Mental State Exam, making them credible biomarkers for assessing the stage of AD [49–51]. However, as intermediates in the formation of higher-order aggregates, Aβ oligomers are highly transient in terms of size and conformation. Although the exact half-life of Aβ oligomers in collected CSF and plasma is not reported, it is well established that Aβ oligomers dissociate into monomers or aggregate further into fibrils in vitro [52]. Accordingly, the degree of aggregation of Aβ oligomers might change over time in CSF and plasma after sample acquisition. Therefore, the level of Aβ oligomer quantified a long time after sample collection might not properly reflect the level of Aβ oligomers in the subject’s brain.

Collectively, these findings show that the time delay between sample collection and processing, storage, or analysis greatly affects the result of Aβ quantification. For the accurate measurement of Aβ concentration, collected samples should be centrifuged, frozen, or analyzed immediately after acquisition, and the type of collection tube must be unified to prevent possible adsorption of Aβ peptides to the surfaces of the collection tube. A universal protocol considering these confounding factors must be established to reduce the intra- or interindividual variability in Aβ concentrations.

Polymorphism and heterogeneity of Aβ

Variations in the structure and number of monomers in Aβ aggregates found in CSF and plasma may complicate the accurate measurement of Aβ levels [53, 54]. Diversified assembly pathways of Aβ aggregation produce Aβ oligomers and fibrils without shared structures [53, 55, 56]. Moreover, circulating Aβ species found in the CSF and plasma are heterogeneous, ranging from low-order oligomers to high-order fibrils, all composed of a different number of Aβ monomers [54]. Aβ quantification in CSF and plasma commonly utilizes enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and other immunoassays that require at least one epitope for antibody binding. Such working mechanism can pose difficulty in measuring the exact level of Aβ as the polymorphic and heterogeneous nature of Aβ may produce aggregates with no detectable epitope exposed, leading to false quantification results with undetected Aβ aggregates. Even supposing the aforesaid aggregates are detected, the Aβ peptides located in the core regions of the aggregates may not be quantified, resulting in less signal than the total number of Aβ peptides present in the sample. Collectively, these properties of Aβ aggregation and immunoassays make direct Aβ quantification from unprocessed fluid samples inaccurate, leading to intra- and interindividual fluctuations in CSF and plasma Aβ levels.

The hardships posed by the polymorphic and heterogeneous nature of Aβ in CSF and plasma may be overcome by homogenizing Aβ aggregates prior to detection. Dissociating aggregated Aβ species into monomers would promote accurate quantification of total Aβ in the sample without any Aβ peptide undetected. However, quantification of monomeric Aβ using ELISA or other immunoassays is difficult as the size difference between Aβ (4.5 kDa) and the antibodies used in ELISA (approximately 150 kDa) produces steric hindrance between them. This challenges one-to-one interaction between Aβ monomer and a set of single capture and detection antibody. Thus, devising novel detection methods to quantify Aβ monomers without the use of antibodies would assist the accurate measurement of Aβ concentration in CSF and plasma. One way of resolving the issue of steric hindrance is spiking Aβ-containing samples with synthetic Aβ followed by a long incubation time to amplify Aβ oligomers. Spiked Aβ can be measured by a detection platform with two antibodies that target an overlapping epitope. By using such antibodies, Aβ species with at least two identical epitopes, which must be composed of more than two Aβ peptides, are selectively detected. This technique has proven effectiveness in measuring the level of oligomeric Aβ in plasma to distinguish AD patients from healthy control subjects with a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 90% [50, 57]. Another study suggested a novel method to detect the true concentration of plasma Aβ, considering the presence of diversified oligomeric species in the samples. In this method, a small molecule that can disaggregate oligomeric Aβ is used to dissociate the Aβ aggregates in plasma [58]. Producing a homogeneous pool of Aβ and comparing the levels of Aβ by self-standard method, the true concentration of plasma Aβ could be measured. Continuous efforts in the investigation of detection devices that target oligomeric Aβ in CSF and plasma are expected to greatly promote accurate diagnosis of AD patients when oligomeric Aβ are generated, at which point, abundant deposition of senile plaques in the brain is still absent.

Low concentration of Aβ in CSF and plasma

The low concentration of Aβ in CSF and plasma increases the difficulty of accurate quantification as it demands detection tools with extremely high sensitivity. While the exact Aβ concentrations differ depending on the assays and protocols used, Aβ exists in CSF at pg/mL scale, ranging from 300 to 700 pg/mL [28, 31, 59–63]. Moreover, CSF Aβ levels of AD patients are decreased compared to healthy individuals as Aβ plaques in AD brains act as “sinks” that impede the movement of soluble Aβ between the brain and CSF. As a result, 40–50% reductions of CSF Aβ are observed in AD patients compared to healthy controls, while the difference is less marked in patients at preclinical stage or with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [27, 64–68]. For CSF Aβ quantification to be implemented as a diagnostic tool for AD at early stages, the minute fluctuations in Aβ levels must be accurately detected, enabling the stratification of preclinical AD and MCI patients into those with low or high risk for future development of AD. This may be challenging as detection of small differences at low concentrations requires highly sensitive devices with a low limit of detection (LOD). Precise quantification of Aβ in plasma is even more difficult as Aβ is found at lower concentrations in plasma compared to CSF, ranging between 10 and 20 pg/mL [35, 69, 70]. Similar to the case of CSF, plasma Aβ concentrations of AD patients are lower than that of healthy individuals [35, 69, 71]. However, the reduction is less pronounced than in CSF Aβ concentrations, increasing the demand for sensitive Aβ quantification tools that can detect extremely small differences.

Unlike the declining trend of CSF Aβ levels in line with AD progression, the concentration of soluble oligomers of Aβ is reported to increase in the CSF of AD patients [49, 72, 73]. However, the level of Aβ oligomers in CSF is significantly lower than that of other forms of Aβ as oligomer concentration ranges between 0.1 and 10 pg/mL, necessitating the development of ultrasensitive detection devices with high sensitivity and specificity to oligomeric Aβ [72, 74, 75]. Although the absolute concentrations of oligomeric Aβ in plasma vary due to differences in detection methods, oligomeric Aβ in the plasma is also increased in AD patients compared to healthy individuals and corresponds with the level of brain amyloid deposition [50, 51]. As the amount of oligomeric Aβ may be an effective indicator of Aβ-induced damages in the brain, its accurate measurement will greatly facilitate the identification of AD patients at early stages.

In summary, accurate measurement of Aβ in CSF and plasma demands detection devices with high sensitivity that quantify Aβ at pg/mL scale and distinguish small differences in Aβ concentrations. Current commercially available immunoassays have LOD in the range of tens of pg/mL [76–80]. Considering CSF and plasma Aβ concentrations at pg/mL scale, LOD must be lower than 1 pg/mL to be able to detect differences in Aβ concentrations between samples. Moreover, considering the relevance of CSF and plasma Aβ oligomer level with the severity of Aβ pathology in AD brains, diagnostic approaches targeting quantification of Aβ with specificity to oligomeric species may provide more accurate means of detecting AD.

Conclusion

The long asymptomatic phase of AD calls for the development of diagnostic tools that enable the discrimination of AD patients from nondemented individuals before the onset of cognitive impairments. With clinical data demonstrating a strong correlation between Aβ deposition in the brain and reduced CSF and plasma Aβ levels, continuous efforts have been made to incorporate CSF and plasma Aβ detection into the clinical diagnosis of AD. However, the lack of ultrasensitive assays and standardized protocols for CSF and plasma Aβ detection continues to impede progress, resulting in dependence on MRI and amyloid-PET scans in clinical diagnosis despite their high cost and limited accessibility. In this review, we presented three confounding factors that can complicate the accurate detection and measurement of Aβ in CSF and plasma (Fig. 1) and provide solutions to overcome these issues (Fig. 2).

To begin with, the stability of Aβ in CSF and plasma must be considered for accurate Aβ detection. Rapid reduction of measurable Aβ levels in CSF and plasma due to degradation calls for attention in keeping storage and analysis time to the minimum. Studies on the effects of preanalytical variables on CSF proteome profile report that CSF processing within two hours does not generate artifactual results [81, 82]. Moreover, while there is no guideline on the time nonfrozen CSF samples can be stored before analysis of Aβ levels, it is recommended to centrifuge the CSF samples immediately after collection to avoid protein degradation as a result of blood contamination possibly due to remaining white blood cells [46, 83, 84]. Stability of Aβ is lower in plasma, and most ongoing protocols in blood-based biomarker studies for AD require a total processing time to be 2 hours or less [85]. Another factor to be addressed is the polymorphism and heterogeneity of Aβ, in which the diversity of circulating Aβ in its molecular structure and level of aggregation raises doubt whether all Aβ peptides can be properly quantified. To overcome this issue, monomerization of the heterogeneous Aβ aggregates in CSF and plasma would ensure that all Aβ peptides are detected, allowing for accurate measurement of Aβ concentration [58, 86]. Considering the critical role of oligomeric species of Aβ in AD pathogenesis as the most toxic Aβ species, future investigation on oligomer-specific detection tools may focus on distinguishing between fibrillar and oligomeric aggregates. Simultaneous characterization of the size and conformation of Aβ oligomers would aid the better understanding of the entire Aβ population in an AD patient, providing more information on the risks of disease progression. Lastly, the low concentration of Aβ challenges accurate quantification and necessitates a precise detection tool with low LOD. As CSF and plasma Aβ concentrations are at pg/mL levels, assays with LOD lower than 1 pg/mL, preferably in fg/mL scale, would be required to accurately identify AD patients. High sensitivity is required not only to discriminate AD patients from healthy individuals but also to identify patients at preclinical and MCI stages by detecting small reductions in Aβ levels. The steric hindrance associated with the size difference between Aβ monomer and antibodies in ELISA must also be considered in the development of Aβ detection device, as it is one of the critical factors that affect thorough detection of total Aβ.

In addition to improving CSF and plasma Aβ detection for AD diagnosis, consideration of the aforementioned factors would be equally important in the precise measurement of other fluid biomarkers for the diagnosis of AD. Moreover, the confounding elements mentioned in this article must be regarded in the detection and quantification of other misfolding proteins that are causative of different neurodegenerative disorders. Future investigations on highly sensitive Aβ detection devices and preanalytical factors in CSF and plasma Aβ quantification will permit the establishment of a consolidated protocol that can be universally implemented for accurate fluid Aβ detection.

Acknowledgements

All images are created by the authors of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project (Grant Number: HU21C0161) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) and Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC), and Basic Science Research Program (Grant Number: NRF-2018R1A6A1A03023718) and Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science Program (Grant Number: NRF-2018M3C7A1021858) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea. This research was also supported by Amyloid Solution and POSCO Science Fellowship of POSCO TJ Park Foundation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: a complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181919a48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang YW, Thompson R, Zhang H, Xu H. APP processing in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Brain. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy MP, LeVine H., III Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masters CL, Selkoe DJ. Biochemistry of amyloid β-protein and amyloid deposits in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen GF, Xu TH, Yan Y, Zhou YR, Jiang Y, Melcher K, Xu HE. Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017 doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar GM, Walsh DM. Alzheimer's disease: synaptic dysfunction and Aβ. Mol Neurodegener. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiwari S, Atluri V, Kaushik A, Yndart A, Nair M. Alzheimer's disease: pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019 doi: 10.2147/IJN.S200490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fakhoury M. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease: implications for therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018 doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170720095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viola KL, Klein WL. Amyloid β oligomers in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao C, Davis FJ, Chauhan BC, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Velasco PT, Klein WL, Chauhan NB. Brain transit and ameliorative effects of intranasally delivered anti-amyloid-β oligomer antibody in 5XFAD mice. J Alzheimer's Dis (JAD) 2013 doi: 10.3233/JAD-122419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao M, Wang SW, Wang YJ, Zhang R, Li YN, Su YJ, Zhou WW, Yu XL, Liu RT. Pan-amyloid oligomer specific scFv antibody attenuates memory deficits and brain amyloid burden in mice with Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014 doi: 10.2174/15672050113106660176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jack CR, Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus C, Mena E, Subramaniam RM. Brain PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2014 doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice L, Bisdas S. The diagnostic value of FDG and amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease—a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamura N, Harada R, Furumoto S, Arai H, Yanai K, Kudo Y. Tau PET imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang XY, Yang ZL, Lu GM, Yang GF, Zhang LJ. PET/MR imaging: new frontier in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damoiseaux JS. Resting-state fMRI as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease? Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1186/alzrt106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vemuri P, Jack CR. Role of structural MRI in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1186/alzrt47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KA, Fox NC, Sperling RA, Klunk WE. Brain imaging in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Fagan AM. Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anoop A, Singh PK, Jacob RS, Maji SK. CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/606802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seppälä TT, Nerg O, Koivisto AM, Rummukainen J, Puli L, Zetterberg H, Pyykkö OT, Helisalmi S, Alafuzoff I, Hiltunen M, Jääskeläinen JE, Rinne J, Soininen H, Leinonen V, Herukka SK. CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer disease correlate with cortical brain biopsy findings. Neurology. 2012 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563bd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teunissen CE, Chiu MJ, Yang CC, Yang SY, Scheltens P, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Plasma Amyloid-β (Aβ42) correlates with cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018 doi: 10.3233/jad-170784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, LaRossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M, Förstl H, Henriksen G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Shiga T, Wester HJ, Kurz A, Drzezga A. Beta amyloid in Alzheimer's disease: increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strozyk D, Blennow K, White LR, Launer LJ. CSF Abeta 42 levels correlate with amyloid-neuropathology in a population-based autopsy study. Neurology. 2003 doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000046581.81650.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tapiola T, Alafuzoff I, Herukka SK, Parkkinen L, Hartikainen P, Soininen H, Pirttilä T. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolboom N, van der Flier WM, Yaqub M, Boellaard R, Verwey NA, Blankenstein MA, Windhorst AD, Scheltens P, Lammertsma AA, van Berckel BN. Relationship of cerebrospinal fluid markers to 11C-PiB and 18F-FDDNP binding. J Nucl Med. 2009 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.064360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansson O, Lehmann S, Otto M, Zetterberg H, Lewczuk P. Advantages and disadvantages of the use of the CSF Amyloid β (Aβ) 42/40 ratio in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deane R, Sagare A, Zlokovic BV. The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood–brain barrier Abeta clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008 doi: 10.2174/138161208784705487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood–brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003 doi: 10.1038/nm890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, van Westen D, Jeromin A, Song L, Hanlon D, Tan Hehir CA, Baker D, Blennow K, Hansson O. Plasma β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease. Sci Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanderstichele H, Bibl M, Engelborghs S, Le Bastard N, Lewczuk P, Molinuevo JL, Parnetti L, Perret-Liaudet A, Shaw LM, Teunissen C, Wouters D, Blennow K. Standardization of preanalytical aspects of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis: A consensus paper from the Alzheimer's Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teunissen CE, Petzold A, Bennett JL, Berven FS, Brundin L, Comabella M, Franciotta D, Frederiksen JL, Fleming JO, Furlan R, Hintzen RQ, Hughes SG, Johnson MH, Krasulova E, Kuhle J, Magnone MC, Rajda C, Rejdak K, Schmidt HK, van Pesch V, Waubant E, Wolf C, Giovannoni G, Hemmer B, Tumani H, Deisenhammer F. A consensus protocol for the standardization of cerebrospinal fluid collection and biobanking. Neurology. 2009 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c47cc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjerke M, Portelius E, Minthon L, Wallin A, Anckarsäter H, Anckarsäter R, Andreasen N, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, Blennow K. Confounding factors influencing amyloid Beta concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/986310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoonenboom NSM, Mulder C, Vanderstichele H, Van Elk E-J, Kok A, Van Kamp GJ, Scheltens P, Blankenstein MA. Effects of processing and storage conditions on Amyloid β (1–42) and Tau concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid: implications for use in clinical practice. Clin Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.039735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simonsen AH, Bahl JM, Danborg PB, Lindstrom V, Larsen SO, Grubb A, Heegaard NH, Waldemar G. Pre-analytical factors influencing the stability of cerebrospinal fluid proteins. J Neurosci Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schipke CG, Jessen F, Teipel S, Luckhaus C, Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, Frölich L, Maier W, Rüther E, Heppner FL, Prokop S, Heuser I, Peters O. Long-term stability of Alzheimer's disease biomarker proteins in cerebrospinal fluid. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011 doi: 10.3233/jad-2011-110329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bibl M, Welge V, Esselmann H, Wiltfang J. Stability of amyloid-β peptides in plasma and serum. Electrophoresis. 2012 doi: 10.1002/elps.201100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiu MJ, Lue LF, Sabbagh MN, Chen TF, Chen HH, Yang SY. Long-term storage effects on stability of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and total tau proteins in human plasma samples measured with immunomagnetic reduction assays. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2019 doi: 10.1159/000496099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toledo JB, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ. Plasma amyloid beta measurements—a desired but elusive Alzheimer's disease biomarker. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1186/alzrt162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rózga M, Bittner T, Batrla R, Karl J. Preanalytical sample handling recommendations for Alzheimer's disease plasma biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.del Campo M, Mollenhauer B, Bertolotto A, Engelborghs S, Hampel H, Simonsen AH, Kapaki E, Kruse N, Le Bastard N, Lehmann S, Molinuevo JL, Parnetti L, Perret-Liaudet A, Sáez-Valero J, Saka E, Urbani A, Vanmechelen E, Verbeek M, Visser PJ, Teunissen C. Recommendations to standardize preanalytical confounding factors in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers: an update. Biomark Med. 2012 doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewczuk P, Beck G, Esselmann H, Bruckmoser R, Zimmermann R, Fiszer M, Bibl M, Maler JM, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J. Effect of sample collection tubes on cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of tau proteins and amyloid beta peptides. Clin Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.058776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andreasen N, Minthon L, Davidsson P, Vanmechelen E, Vanderstichele H, Winblad B, Blennow K. Evaluation of CSF-tau and CSF-Aβ42 as diagnostic markers for alzheimer disease in clinical practice. Arch Neurol. 2001 doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santos AN, Ewers M, Minthon L, Simm A, Silber R-E, Blennow K, Prvulovic D, Hansson O, Hampel H. Amyloid-β oligomers in cerebrospinal fluid are associated with cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang MJ, Yi S, Han J, Park SY, Jang J-W, Chun IK, Kim SE, Lee BS, Kim GJ, Yu JS, Lim K, Kang SM, Park YH, Youn YC, An SSA, Kim S. Oligomeric forms of amyloid-β protein in plasma as a potential blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0324-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou L, Chan KH, Chu LW, Kwan JSC, Song YQ, Chen LH, Ho PWL, Cheng OY, Ho JWM, Lam KSL. Plasma amyloid-β oligomers level is a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michaels TCT, Šarić A, Curk S, Bernfur K, Arosio P, Meisl G, Dear AJ, Cohen SIA, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, Linse S, Knowles TPJ. Dynamics of oligomer populations formed during the aggregation of Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide. Nat Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tycko R. Amyloid polymorphism: structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De S, Whiten DR, Ruggeri FS, Hughes C, Rodrigues M, Sideris DI, Taylor CG, Aprile FA, Muyldermans S, Knowles TPJ, Vendruscolo M, Bryant C, Blennow K, Skoog I, Kern S, Zetterberg H, Klenerman D. Soluble aggregates present in cerebrospinal fluid change in size and mechanism of toxicity during Alzheimer’s disease progression. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0777-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Colletier J-P, Laganowsky A, Landau M, Zhao M, Soriaga AB, Goldschmidt L, Flot D, Cascio D, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D. Molecular basis for amyloid-β polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112600108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldsbury C, Frey P, Olivieri V, Aebi U, Müller SA. Multiple assembly pathways underlie amyloid-β fibril polymorphisms. J Mol Biol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.An SSA, Lee B-S, Yu JS, Lim K, Kim GJ, Lee R, Kim S, Kang S, Park YH, Wang MJ, Yang YS, Youn YC, Kim S. Dynamic changes of oligomeric amyloid β levels in plasma induced by spiked synthetic Aβ(42) Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0310-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim Y, Yoo YK, Kim HY, Roh JH, Kim J, Baek S, Lee JC, Kim HJ, Chae M-S, Jeong D, Park D, Lee S, Jang H, Kim K, Lee JH, Byun BH, Park SY, Ha JH, Lee KC, Cho WW, Kim J-S, Koh J-Y, Lim SM, Hwang KS. Comparative analyses of plasma amyloid-β levels in heterogeneous and monomerized states by interdigitated microelectrode sensor system. Sci Adv. 2019 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Andreasson U, Londos E, Minthon L, Blennow K. Prediction of Alzheimer's disease using the CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007 doi: 10.1159/000100926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lehmann S, Delaby C, Boursier G, Catteau C, Ginestet N, Tiers L, Maceski A, Navucet S, Paquet C, Dumurgier J, Vanmechelen E, Vanderstichele H, Gabelle A. Relevance of Aβ42/40 ratio for detection of Alzheimer disease pathology in clinical routine: the PLM(R) Scale. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baiardi S, Abu-Rumeileh S, Rossi M, Zenesini C, Bartoletti-Stella A, Polischi B, Capellari S, Parchi P. Antemortem CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio predicts Alzheimer's disease pathology better than Aβ42 in rapidly progressive dementias. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1002/acn3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewczuk P, Lelental N, Spitzer P, Maler JM, Kornhuber J. Amyloid-β 42/40 cerebrospinal fluid concentration ratio in the diagnostics of Alzheimer's disease: validation of two novel assays. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015 doi: 10.3233/jad-140771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koychev I, Galna B, Zetterberg H, Lawson J, Zamboni G, Ridha BH, Rowe JB, Thomas A, Howard R, Malhotra P, Ritchie C, Lovestone S, Rochester L. Aβ42/Aβ40 and Aβ42/Aβ38 ratios are associated with measures of gait variability and activities of daily living in mild Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018 doi: 10.3233/jad-180622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer's disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, Andreasen N, Parnetti L, Jonsson M, Herukka S-K, van der Flier WM, Blankenstein MA, Ewers M, Rich K, Kaiser E, Verbeek M, Tsolaki M, Mulugeta E, Rosén E, Aarsland D, Visser PJ, Schröder J, Marcusson J, de Leon M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Pirttilä T, Wallin A, Jönhagen ME, Minthon L, Winblad B, Blennow K. CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2009 doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andreasen N, Hesse C, Davidsson P, Minthon L, Wallin A, Winblad B, Vanderstichele H, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid β-Amyloid(1–42) in Alzheimer disease: differences between early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease and stability during the course of disease. Arch Neurol. 1999 doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hertze J, Minthon L, Zetterberg H, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K, Hansson O. Evaluation of CSF biomarkers as predictors of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical follow-up study of 4.7 years. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sala A, Nordberg A, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I Longitudinal pathways of cerebrospinal fluid and positron emission tomography biomarkers of amyloid-β positivity. Mol Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00950-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fan D-Y, Sun H-L, Sun P-Y, Jian J-M, Li W-W, Shen Y-Y, Zeng F, Wang Y-J, Bu X-L. The correlations between plasma fibrinogen with amyloid-beta and tau levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.625844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lue L-F, Sabbagh MN, Chiu M-J, Jing N, Snyder NL, Schmitz C, Guerra A, Belden CM, Chen T-F, Yang C-C, Yang S-Y, Walker DG, Chen K, Reiman EM. Plasma levels of Aβ42 and tau identified probable Alzheimer’s dementia: findings in two cohorts. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pomara N, Willoughby LM, Sidtis JJ, Mehta PD. Selective reductions in plasma Aβ 1–42 in healthy elderly subjects during longitudinal follow-up: a preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 doi: 10.1097/00019442-200510000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Savage MJ, Kalinina J, Wolfe A, Tugusheva K, Korn R, Cash-Mason T, Maxwell JW, Hatcher NG, Haugabook SJ, Wu G, Howell BJ, Renger JJ, Shughrue PJ, McCampbell A. A sensitive Aβ oligomer assay discriminates Alzheimer's and aged control cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosci. 2014 doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1675-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herskovits AZ, Locascio JJ, Peskind ER, Li G, Hyman BT. A Luminex assay detects Amyloid β oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hölttä M, Hansson O, Andreasson U, Hertze J, Minthon L, Nägga K, Andreasen N, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Evaluating Amyloid-β oligomers in cerebrospinal fluid as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sung W-H, Hung J-T, Lu Y-J, Cheng C-M. Paper-based detection device for Alzheimer’s disease—detecting β-amyloid peptides (1–42) in human plasma. Diagnostics. 2020 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10050272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ellis TA, Li J, Leblond D, Waring JF. The relationship between different assays for detection and quantification of amyloid beta 42 in human cerebrospinal fluid. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/984746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pérez-Grijalba V, Fandos N, Canudas J, Insua D, Casabona D, Lacosta AM, Montañés M, Pesini P, Sarasa M. Validation of immunoassay-based tools for the comprehensive quantification of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in plasma. J Alzheimer's Dis (JAD) 2016 doi: 10.3233/JAD-160325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mehta PD, Pirttilä T, Mehta SP, Sersen EA, Aisen PS, Wisniewski HM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid β proteins 1–40 and 1–42 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000 doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heo Y, Shin K, Park MC, Kang JY. Photooxidation-induced fluorescence amplification system for an ultra-sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Sci Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85107-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berven FS, Kroksveen AC, Berle M, Rajalahti T, Flikka K, Arneberg R, Myhr KM, Vedeler C, Kvalheim OM, Ulvik RJ. Pre-analytical influence on the low molecular weight cerebrospinal fluid proteome. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007 doi: 10.1002/prca.200700126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jimenez CR, Koel-Simmelink M, Pham TV, van der Voort L, Teunissen CE. Endogeneous peptide profiling of cerebrospinal fluid by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: optimization of magnetic bead-based peptide capture and analysis of preanalytical variables. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007 doi: 10.1002/prca.200700330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rosenling T, Slim CL, Christin C, Coulier L, Shi S, Stoop MP, Bosman J, Suits F, Horvatovich PL, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Vreeken R, Hankemeier T, van Gool AJ, Luider TM, Bischoff R. The effect of preanalytical factors on stability of the proteome and selected metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) J Proteome Res. 2009 doi: 10.1021/pr9005876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.You J-S, Gelfanova V, Knierman MD, Witzmann FA, Wang M, Hale JE. The impact of blood contamination on the proteome of cerebrospinal fluid. Proteomics. 2005 doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O'Bryant SE, Gupta V, Henriksen K, Edwards M, Jeromin A, Lista S, Bazenet C, Soares H, Lovestone S, Hampel H, Montine T, Blennow K, Foroud T, Carrillo M, Graff-Radford N, Laske C, Breteler M, Shaw L, Trojanowski JQ, Schupf N, Rissman RA, Fagan AM, Oberoi P, Umek R, Weiner MW, Grammas P, Posner H, Martins R. Guidelines for the standardization of preanalytic variables for blood-based biomarker studies in Alzheimer's disease research. Alzheimers Dement. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Englund H, Degerman Gunnarsson M, Brundin RM, Hedlund M, Kilander L, Lannfelt L, Ekholm PF. Oligomerization partially explains the lowering of Aβ42 in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. Neurodegener Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1159/000225376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]