Abstract

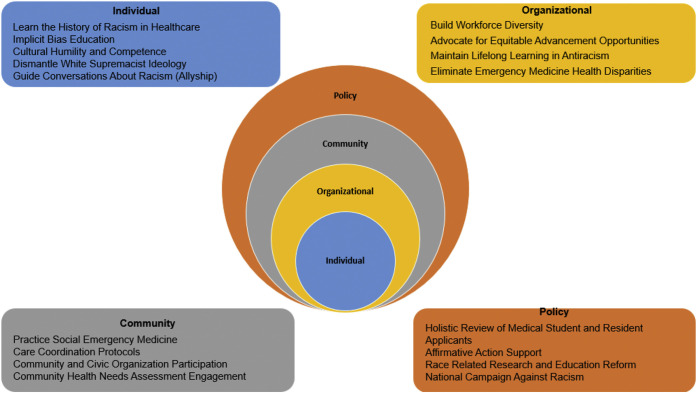

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the ongoing pandemic of racial injustice. In the context of these twin pandemics, emergency medicine organizations are declaring that “Racism is a Public Health Crisis.” Accordingly, we are challenging emergency clinicians to respond to this emergency and commit to being antiracist. This courageous journey begins with naming racism and continues with actions addressing the intersection of racism and social determinants of health that result in health inequities. Therefore, we present a social-ecological framework that structures the intentional actions that emergency medicine must implement at the individual, organizational, community, and policy levels to actively respond to this emergency and be antiracist.

Background

Emergency medicine was born as a specialty from the efforts of pioneering physicians who saw the need for quality emergency care. This emergency care would be available to all patients at all times, day or night.1 As a specialty whose primary purpose is to address emergency care, emergency medicine must address the acute and chronic emergency of racism. It is imperative to understand that race is a social construct and not a biological determinant. Racism is a system of structured opportunity and assignment of value that intentionally disadvantages individuals based on the color of their skin.2, 3, 4 The trauma of blatant direct individual racist actions and racism on individuals and our community cannot be understated. The responsibility to be antiracist is to advocate for racial equality and actively identify and change policies, practices, and organizational structures that support racism.5 National emergency medicine organizations publicly issuing a statement of “Racism is a Public Health Crisis” is a first step.6, 7, 8 In taking the next step, emergency clinicians and organizations can be informed by the social-ecological model for the prevention of violence, a public health tool. This public health tool considers the intersection of causes of violence at multiple levels and how factors at one level influence factors at another level. We propose that emergency clinicians and organizations apply this tool to consider the intersection of causes of the trauma of racism and implement antiracist actions for emergency clinicians to follow at the individual, organizational, community, and policy levels.9

A direct benefit of emergency clinicians and organizations embracing the responsibility of being antiracist is the advancement of health equity through actions mitigating racial health disparities. Health equity is defined as the equal opportunity for everyone to be healthy and is founded on the ethical principle of justice—fair and equitable distribution of health care resources. Health disparities represent health differences that are closely linked with social, economic, or environmental disadvantages and adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health.10 In emergency medicine, health disparities exist despite our founding principle to provide quality care for all people and the mandate to provide that care equitably.11, 12, 13 The ideal state for emergency medicine to address racism and health disparities entails having a culturally competent emergency medicine workforce that reflects the patients served; feedback regarding disparities in decisionmaking and outcomes; organizational and community collaboration for solutions to address the disproportionate distribution of social determinants of health; and enforced policy to ensure health care, academic, community practice, and emergency medicine organizations comply with these goals. The challenge begins with asking the question, “How is racism operating here?”2 We advocate that emergency medicine asks this question at every level of the socio-ecological model proposed (Figure , Table 1 ) as the framework for emergency medicine to be antiracist and to actively work to achieve health equity for patients.

Figure.

The social-ecological model for antiracism in emergency medicine.

Table 1.

The social-ecological model for antiracism in emergency medicine.

| Focus | Individual | Organizational | Community | Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audience | EM clinicians (physicians, advanced practice providers, paramedics, nurses, learners) | Academic medicine, ACEP, SAEM, AAEM, ABEM, CORD, AAMC, ACGME, EM clinician practice groups, hospitals | EM practice groups, EM supported clinics (free standing, urgent care), emergency medical services, hospitals | EM supported advocacy groups, medical schools, EM practice groups, research institutions |

| Attention | Personally mediated racism, Internalized racism | Systemic racism | Systemic racism | Systemic racism |

| Action | Learn the history of racism in health care Implicit bias education Cultural humility and competence Dismantle white supremacist ideology Guide conversations about racism (allyship) |

Build workforce diversity Advocate for equitable advancement opportunities Maintain lifelong learning in antiracism Eliminate EM disparities |

Practice social EM Care coordination protocols Community and civic organization participation CHNA engagement |

Holistic review of medical school and residency applicants Affirmative action support Race-related research and education reform National campaign against racism |

AAEM, American Academy of Emergency Medicine; AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ABEM, American Board of Emergency Medicine; ACEP, American College of Emergency Physicians; ACGME, American Council for Graduate Medical Education; CHNA, Community Health Needs Assessment; CME, Continuous Medical Education; CORD, Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine; EM, emergency medicine; SAEM, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine; SDoH, Social Determinants of Health.

Individual Level

Learn the History of Racism in Health Care

To actively become or remain an antiracist individual, one must start with history and examine its impact. The history of racism in the Americas began with the treatment of the Indigenous people and of Africans and their descendants as property by White colonizers during slavery. This foundational philosophy that Blacks were subhuman led to mischaracterization, experimentation, and exploitation by Whites. Medicine significantly benefited from these actions for over 400 years. This history touches clinical practice, medical education, research, and health care resource allocation for patients and clinicians of color.14 The American Medical Association was deeply rooted in the perpetuation of this philosophy, rendering an apology just 12 years ago and finally declaring strategies for the house of medicine to be actively antiracist in 2020.15 , 16 The breadth and depth of the history of racism, including how individuals have been influenced by this historical construct, must be learned and acknowledged (Table 2 ). Miller et al17 developed practice recommendations for addressing racism that are adaptable strategies for emergency medicine individuals. These include validating the reality of racism, critically examining privilege and racial attitudes, developing positive identity, and externalizing and minimizing self-blame. Dismantling personally mediated racism and internalized racism, intentional or unintentional, requires that individuals examine their experiences in the context of the history of racism. This is a complex task for everyone and warrants guided education on recognizing and counteracting racism.

Table 2.

Resources for learning the history of racism in health care and health equity.

| Resource | Link |

|---|---|

Association of American Medical Colleges

|

|

American Medical Association

|

|

MedEdPORTAL: The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources

|

|

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

|

|

Highlighted books

|

|

AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges.

Implicit Bias Education

Implicit biases stem from racial profiling, lack of familiarity with other cultures, perpetuated and sensationalized stereotyping in the media, misinformation passed within social circles, and lived experiences of advantage or disadvantage. Furthermore, implicit bias of clinicians of all backgrounds contributes to the generational trauma of distrust in health care by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. This tradition of distrust by Black Americans specifically is rightfully passed down among generations, and despite health care providers’ efforts to move forward, the inhumane legacy of the Tuskegee Experiment still prevails.18 Accordingly, only 42% of Black Americans were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine in November of 2020.19 This distrust remained even when individual physicians were not directly involved in the care in question. Thus, acknowledging these historical actions and the resulting distrust is an important step to reshape individual implicit bias in medicine.20, 21, 22

In addition, emergency clinicians should adopt the Trauma-Informed Medical Education (TIME) model, acknowledging that bias and discrimination inflict trauma on their targets through emotional injury.23 TIME fosters awareness that students and trainees can experience trauma from a biased system and culture and advocates for the establishment of policies and practices that support learners to prevent further retraumatization. Identification of personal implicit bias is a key part of being antiracist. Continuous implicit bias education raises awareness of blind spots regarding medical decisions that contribute to health disparities, sharpens the lens of our experiences, and can improve relationships with our patients, colleagues, and communities.24

Cultural Humility and Competence

Emergency clinicians must be accepting of others and interact effectively with all patients to optimize patient experience and outcomes. Cultural humility challenges us to self-reflect and continually critique our ability to understand others who are different, recognizing that culture encompasses more than race and ethnicity and relates to all affinity groups. Cultural competence is more than a skill to achieve; it implies accountability to the antiracist action of striving to know more about all communities with whom we work. Cultural humility and cultural competence have been used to promote self-reflection regarding dimensions of diversity that are characterized by inequities in power, privilege, and justice. These concepts stress the need to challenge the institutions and systems that enable these injustices to continue.25 Cultural humility and competence begin with the individual clinician embracing the benefits of attaining a mutual understanding of health beliefs with patients and families and committing to continuous awareness. Proposed cultural competence techniques—such as cultural immersion programs or inclusion of family and community health workers in decisionmaking to address racial/ethnic health disparities—support the socio-ecological model of antiracism for emergency medicine.26

Dismantle White Supremacist Ideology

White supremacist ideology, which is a false belief in a hierarchy of human value based on race where Whites are at the top, is a cultural and societal barrier to achieving health equity that must be dismantled by antiracist action.27 White privilege is a manifestation of this ideology and reveals itself in health care as discrimination demonstrated by bias, prejudice, racist comments, stereotyping, and race-based decisionmaking. White clinicians can use the work of Peggy McIntosh28 to recognize how they benefit from racial privilege. Additionally, they should join all clinicians in speaking out against these social norms of racial advantage that ultimately affect patients.29 The Institute of Medicine report “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” provides evidence to support the disparate delivery of quality health care based on discrimination at the individual provider level.30 Dismantling this ideology begins with antiracist change at the individual level so that change on the organizational, community, and policy levels can be achieved and sustained. Individuals must also be held accountable to policies directing structural change through transparent tracking of progress.

Guide Conversations About Racism (Allyship)

Allies from the racially advantaged group who take an active role in eradicating unfair practices they witness leads to successful conversations about racism that extend beyond the disadvantaged group.31 An “ally” who supports the disadvantaged group typically has an internal commitment to social justice that needs no credit and is open to feedback from those they support. Although similar to a “bystander” who can identify racist practices and behaviors, an “ally” understands their own privilege in the conversation about race.32 In addition, becoming an ally is an intentional quest that requires active learning about racism and individual implicit biases and listening to and accepting criticism in uncomfortable conversations.33 Emergency clinicians must recognize their individual contributions to the trauma of racism when standing by and its persistence if bystanders do not invest in becoming allies.

Organizational Level

Build Workforce Diversity

At the organizational level, antiracist actions begin with diversifying the workforce. Diverse physicians improve the delivery of quality care provided to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, impacting medication adherence, shared decisionmaking, wait times for treatment, and patient perceptions of treatment decisions.34, 35, 36, 37, 38 The representation of Black, Indigenous, and nurses or clinical support staff of color on the care team substitutes for the presence of a Black, Indigenous, or physicians of color to achieve similar outcomes.39 Currently, Whites make up most of the emergency physician workforce in the practicing physician (69.2%), active resident (57%), and emergency medicine applicant (61%) groups.40 Pipeline programs in the health professions and affirmative action initiatives have proven to be important strategies for increasing Black, Indigenous, and students of color in medicine.41, 42, 43 Just as with students, recruitment and retention of Black and Indigenous emergency clinicians and those of color into practice groups must be deliberate to include mentorship and an inclusive work environment.44 Inclusion strategies, such as the provision of a safe space (affinity groups, targeted retreats, and counseling support) for individuals with like experiences to voice concerns and receive nonjudgmental support, are effective for racial/ethnic groups in all sectors of the workplace. It is also critical that leaders model behaviors that support bias recognition, address micro- and macroaggressions, and ensure equitable opportunities in the work environment. Workplace diversity also succeeds with intentionally designated diversity leaders and organizational leaders that model fair and equitable performance evaluation practices.45

Advocate for Equitable Advancement Opportunities

From medical school to residency, faculty appointment to promotion, as well as clinical directorship and executive leadership, a commitment must be made by hiring organizations to ensure equitable advancement opportunities for diverse clinicians. Strategies include assembling a diverse hiring and promotions committee, educating these committees about minimizing and mitigating their implicit biases, and utilizing a standardized letter of recommendation for students to decrease race-based bias.46 Intentionally including more than one Black, Indigenous, or person of color in a candidate pool also increases the odds of hiring a Black, Indigenous, or person of color and is another strategy for equitable advancement.47 Efforts such as salary equity studies and flexible appointment policies should be instituted and adhered to by organizations to address gaps related to the “minority tax,” which devalue work contributions by Black and Indigenous clinicians and those of color.48, 49, 50 Increasing diversity at the entry level must be followed by intentional antiracist practices by the hiring organization to provide equitable advancement opportunities for Black and Indigenous clinicians and clinicians of color.

Maintain Lifelong Learning in Antiracism

For emergency clinicians to become and remain proficient in antiracism actions, intentional instruction about the history of racism in medicine must begin in medical school. Opening discussion on this topic is the first step in a healing process that will help people grow together generally and as health professionals.51 Active learning during and after residency in all educational forums is also necessary for emergency clinicians to make sustainable change. Leveraging continuing medical education forums as a maintenance of certification requirement, however, has mixed results with regard to effectiveness.51 , 52 Discussing the “isms” (racism, sexism, etc) through the more transformative approach of intercultural education opens conversations among health professionals and educators to the critical importance of addressing racism and all the “isms” across the learning continuum.51 This will prevent the unintended consequence of “checking the box” of attestation of a mandated continuing medical education activity to address racism. Academic institutions, professional organizations, and hospital credentialing committees should provide these learning opportunities and reward active antiracist practices.

Eliminate Emergency Medicine Disparities

The persistence of health disparities reflects the lack of progress in addressing health equity. Factors impacting care provided by an individual, practice group, or medicine specialty are numerous and should be systematically addressed to ensure accountability. Research in emergency medicine has identified racial disparities in care related to emergency department (ED) wait times, pain management administration, and imaging utilization.53 Emergency clinicians can lead antiracist practices by creating dashboards to stratify data from insurance claims data repositories, registry data such as that from the Clinical Emergency Data Registry, and hospital outcomes and ED quality metrics by race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health to identify health disparity gaps.54 This action provides awareness of disparities to the organization and supports prioritization in the strategic planning process to apply resources for meaningful solutions. An example of examining data by race and ethnicity to bring awareness to health disparities in health care access leveraged Medicare claims data to evaluate ambulance transport decisions.55 Examined race and ethnicity data regarding which medical centers patients were transported by emergency medical services (EMS) resulted in destination disparities noted in larger urban areas with multiple hospitals and EDs within the vicinity.55 Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be transported to a “safety net” hospital compared to White patients from the same zip code.55 Identifying the root cause of such a disparity starts with ensuring that the steps of the intended process are executed. In this example, recording the patients’ destination choices can further inform how EMS transport patterns contribute to the disparity. Another method of evaluating disparities in health care access is stratifying ED arrival mode data by race and zip code, where census data on transportation can be accessed. Once the root cause of a health disparity is identified, the design of tailored solutions that partner with community resources to address potential social needs and risks is key. Evaluating outcome data in this manner shows that organizations are attuned to the intentional work that is necessary to achieve equity in emergency medicine outcomes.56

Community Level

Practice Social Emergency Medicine

Biases in medicine affect patients on an individual level but also systematically through the distribution of resources. Through discrimination in education, housing, and employment, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color have decreased access to financial growth, healthy lifestyle practices, healthy food options, health insurance, and preventive health care.13 , 57, 58, 59 Practicing social emergency medicine involves actively considering these factors as social risks and also considering social needs along with medical needs. Identifying social risks, specific adverse social conditions associated with poor health specific to the individual, and social needs, determined by an individual’s preferences and priorities, presents the opportunity to actively engage with individual patients and communities on interventions.60 Emergency medicine professional societies and academic and community practice groups are responding to this call to action of evolving emergency medicine practice to include social emergency medicine in education, research, and advocacy. Organizational support of the practice of social emergency medicine addresses structural racism through actions aimed at positively impacting health outcomes and patient experiences and reducing costs to improve population health. Providing emergency clinicians with training and tools to navigate potentially difficult conversations about patient social needs without inducing additional trauma is critical to the patient experience and complements the cultural humility and competence required for effective shared decisionmaking.61 Social emergency medicine promotes humanity by incorporating social context in emergency medicine practice and advocates for leveraging hospital and community resources to address health inequities.

Care Coordination Protocols

The best practice of protocolized trauma and stroke teams has led to timely and effective patient care in the ED. A protocolized team strategy can be applied to care coordination in the ED to identify and intervene with the appropriate level of resources. A standardized tool for assessing patient social needs and social risks guides decisionmaking and is important for emergency clinicians to facilitate access to community resources for individual patients and to inform hospital and community partners on additional opportunities to address gaps.62 Furthermore, emergency clinicians must be armed with links to community resources in the disposition workflow and have access to social workers, case managers, or community health workers for additional support. Assessing social needs and social risks during care in the ED empowers emergency clinicians to be antiracist by actively ensuring that equitable care is rendered despite the disparate distribution of resources. ED directors should also work with hospital/health systems leaders to implement cost-benefit solutions that enhance patient flow and streamline utilization of the ED, considering the social needs and risks of patients.63

Community and Civic Organization Participation

Community service expands beyond the direct care of patients in the ED or hospital for clinicians. Emergency clinicians bring unique voices to the board rooms, city councils, school boards, or civic committees responsible for decisions regarding distribution of resources. Active participation in volunteer organizations allows the development of programming with community partnerships that can direct resources to address gaps in social determinants of health.64 Although emergency medicine professional societies advocate for emergency medicine practice at the state and national levels, the ability to create change at the community level is within reach of the emergency clinicians, nurses, advanced practice providers, and EMS providers working as an affinity group or through local professional societies. Organizations can further empower this activity through incentives or academic promotion credit or by providing certification credit for activities aimed at social justice and antiracism. Health care systems, emergency medicine practice groups, and academic institutions must also leverage their networks of influence on key issues by fundraising and working with grateful patients to secure funding for interventions that support care coordination services for patients in the ED.

Community Health Needs Assessment Engagement

Hospitals with tax-exempt status are required by the Affordable Care Act to perform community health needs assessments and implement strategies to provide community benefits that meet their communities’ needs. Hospitals collaborate with public health experts to perform the assessment, develop strategies, and complete the report every 3 years.65 Since the ED is a site of primary care for many patients, utilization patterns of the ED also guide the community health needs assessment. Hospitals should leverage EDs to inform population health targeted strategies that engage patients and collaborate with community resources on program intervention design. Hospitals should also invest in EDs to implement actions from the community health needs assessment that specifically address racial disparities connected to social needs and risks. Population health management takes into consideration patient social needs and risks and provides another antiracist opportunity for emergency medicine to improve the quality of care provided through implementation of the hospital’s community health needs assessment.

Policy Level

Holistic Review of Medical School and Residency Applicants

Holistic review is an antiracist action requiring organizations to consider an applicant’s experiences, attributes, academic performance, and potential value collectively. The American Association of Medical Colleges provides resources for academic and community-based organizations to implement policies and practices that consider the “whole” applicant and not focus disproportionately on any one metric for admission or selection criteria.66 Studies have shown discrepancies in standardized test scores between students who are Black, Indigenous, and People of color and White students.67 , 68 However, these discrepancies are attributed to differences in opportunities and not differences in aptitude.69 These differences in opportunities are rooted in systemic racism that have led to disparities in housing, criminal justice, health outcomes, educational opportunities, and access to participation in gifted and talented programs.69, 70, 71, 72, 73 To combat systemic racism in medical school and residency program admissions processes, institutions must reexamine the role of standardized test scores. They are merely one aspect of applicants’ portfolios and not a measure of clinical abilities or potential for significant contributions to the field. Promoting holistic review at this level of the clinician pipeline provides the critical human resources needed downstream to ensure that a diverse workforce can be attained and sustained.

Affirmative Action Support

The Supreme Court upholds its decision on affirmative action and the use of race as a factor in school admissions.74 Affirmative action allows for consideration of an individual’s race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and immigrant status. Diverse student bodies correlate with the increased academic success, retention, and community involvement of all students.74 In addition to fostering academic success, affirmative action’s contribution to racial and ethnic diversity in the health care workforce promotes organizational cultural competence.34 Providers who are culturally competent can better care for Black and Indigenous patients and patients of color.34 Emergency medicine can level the playing field and improve patient outcomes by supporting and maintaining affirmative action policies.

Race-Related Research and Education Reform

Inaccurate assumptions of race-based differences in physiology and pathology, such as differences in sensation of pain, pulmonary function, and kidney function, continue to be perpetuated in medical literature and built into metrics for race corrections or “ethnic adjustments” in medical calculators.75, 76, 77 As recently as 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration approved a race-specific drug called BiDil to treat heart failure in Black Americans, despite lack of comparison with other racial groups.78, 79, 80, 81 Differences found between racial categories in research studies may be inaccurate due to poorly defined standards for categorizing race and should be understood as social or geographic differences rather than biological ones.82 Perpetuating race-based medical beliefs is racist and supports the misconception that there are innate biological differences between races that lead to health disparities while ignoring the structural racism that contributes to these disparities.83 Abolishing unsubstantiated race-based medical practices and correcting historical misconceptions in medical school curricula, residency training, and continuing medical education is an antiracist action that allows clinicians to be appropriately educated on the impact of racism in medicine. Additionally, discontinuing support of perpetuated misconceptions of race-based research found in study design, funding, and publication is an antiracist action that supports equitable care provision. The National Institute of Health’s commitment to ending structural racism acknowledges this issue and models antiracist action.84

National Campaign Against Racism

Efforts to address antiracism have existed at the international level since 1965. Emergency medicine should advocate for policies supporting the recommendations from the 2014 United Nations Committee to Eliminate Racial Discrimination. These include addressing racial profiling, residential segregation, differential access to health care, the achievement gap in education, and disproportionate incarceration and dismantling structural racism.2 Also, as trauma and injury care experts, emergency medicine workers are uniquely positioned to impact public health in this space. For example, at the individual level, emergency medicine clinicians can become proficient in deescalation techniques to mitigate interpersonal violence that may be fueled by bias and racial profiling in the ED and in the field while working with first responders. At the organizational level, emergency medicine injury prevention researchers should evaluate “how racism is operating here” when the root cause of the violence is identified and recommendations are made. Emergency clinicians, along with hospital and health systems, can stratify injury data by race, ethnicity, and social determinants to work with community leaders at the zip code level regarding the impact the environment places on these potential avoidable encounters. Finally, at the policy level, just as emergency clinicians were called to engage and advocate for injury prevention regarding motor vehicle safety beyond the clinical care environment, emergency clinicians can advocate for demonstrable policy change, collaborating with government and industry regarding injury prevention related to racism.85 It is critical for emergency medicine to strategically get involved in targeted solutions to participate in a national campaign against racism to fulfill the pledge to treat this public health emergency.

Conclusion

Dismantling racism and moving toward being antiracist is an emergency that emergency clinicians and organizations must address. The Social-Ecological Model for Antiracism in Emergency Medicine is a tool for this emergency, and the time is now.

Footnotes

Supervising editor: Richelle J. Cooper, MD, MSHS. Specific detailed information about possible conflict of interest for individual editors is available at https://www.annemergmed.com/editors.

All authors attest to meeting the 4 ICMJE.org authorship criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND (3) Final approval of the version to be published; AND (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Fundingandsupport: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Suter R.E. Emergency medicine in the United States: a systemic review. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3:5–10. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones C.P. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a National Campaign against Racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28:231–234. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones C.P. Invited commentary: “race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:299–304. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones C.P. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendi I.X. One World; 2019. How to Be an Antiracist. [Google Scholar]

- 6.AACEM Statement on Systemic Racism. https://www.saem.org/docs/default-source/aacem/aacem-statement-on-systemic-racism-21june2020-ln.pdf?sfvrsn=98f001fd_0 Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine. Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 7.ACEP Statement on Structural Racism and Public Health. https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/press-releases/2020/5-30-20-acep-statement-on-structural-racism-and-public-health American College of Emergency Physicians. Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 8.AAEM Releases Statement with SAEM on the Death of George Floyd. https://www.aaem.org/current-news/death-of-george-floyd American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 9.The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 10.Braveman P.A., Kumanyika S., Fielding J., et al. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:S149–S155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heron S.L., Stettner E., Haley L.L. Racial and ethnic disparities in the emergency department: a public health perspective. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24:905–923. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cone D.C., Richardson L.D., Todd K.H., et al. Health care disparities in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1176–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard J.C., Haywood Y.C., Scott C. Racial and ethnic disparities in health: an emergency medicine perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1289–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas S.B., Casper E. The burdens of race and history on Black people’s health 400 years after Jamestown. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:1346–1347. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis R.M. Achieving racial harmony for the benefit of patients and communities: contrition, reconciliation, and collaboration. JAMA. 2008;300:323–325. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama-racism-threat-public-health American Medical Association. Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 17.Miller M.J., Keum B.T., Thai C.J., et al. Practice recommendations for addressing racism: a content analysis of the counseling psychology literature. J Couns Psychol. 2018;65:669–680. doi: 10.1037/cou0000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banisky S. The Baltimore Sun; 1997. A SURVIVOR'S GRACE: At 95, Tuskegee study participant Herman Shaw prefers reconciliation to recrimination, forgiveness to bitterness. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hostetter M., Klein S. Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: Accessed April 24, 2021.

- 20.Sidhu J. ProPublica; 2008. Exploring the AMA’s History of Discrimination.https://www.propublica.org/article/exploring-the-amas-history-of-discrimination716 Available at: Accessed December 30 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuriddin A., Mooney G., White A.I. Reckoning with histories of medical racism and violence in the USA. Lancet. 2020;396:949–951. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acosta D., Karp D.R. Restorative justice as the Rx for mistreatment in academic medicine: applications to consider for learners, faculty, and staff. Acad Med. 2018;93:354–356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClinton A., Laurencin C.T. Just in TIME: Trauma-Informed Medical Education. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:1046–1052. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00881-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez C.M., Deno M.L., Kintzer E., et al. Patient perspectives on racial and ethnic implicit bias in clinical encounters: implications for curriculum development. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:1669–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene-Moton E., Minkler M. Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21:142–145. doi: 10.1177/1524839919884912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brach C., Fraserirector I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones C.P. Center for Primary Care, Harvard Medical School; 2020. Seeing the Water: Seven Values Targets for Anti-Racism Action.http://info.primarycare.hms.harvard.edu/blog/seven-values-targets-anti-racism-action Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntosh P. White privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. Peace and Freedom. 1989 https://psychology.umbc.edu/files/2016/10/White-Privilege_McIntosh-1989.pdf Available at: Accessed January 28 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romano M.J. White privilege in a white coat: how racism shaped my medical education. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:261–263. doi: 10.1370/afm.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . In: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Smedley B.D., Stith A.Y., Nelson A.R., editors. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sue D.W., Alsaidi S., Awad M.N., et al. Disarming racial microaggressions: microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. Am Psychol. 2019;74:128–142. doi: 10.1037/amp0000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scully M., Rowe M. Bystander training within organizations. JIOA. 2009;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamont A. Guide to allyship: What is an ally? https://guidetoallyship.com/#what-is-an-ally Available at: Accessed April 24, 2021.

- 34.Jackson C.S., Gracia J.N. Addressing health and health-care disparities: the role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:57–61. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall W.J., Chapman M.V., Lee K.M., et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e60–e76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mensah M.O., Sommers B.D. The policy argument for healthcare workforce diversity. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1369–1372. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3784-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osseo-Asare A., Balasuriya L., Huot S.J., et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723. e182723-e182723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper L.A., Roter D.L., Johnson R.L., et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huerto R., Lindo E. Minority patients benefit from having minority doctors, but that’s a hard match to make. https://theconversation.com/minority-patients-benefit-from-having-minority-doctors-but-thats-a-hard-match-to-make-130504 Available at: Accessed April 23, 2021.

- 40.Ehrhardt T, Shepherd A, Kinslow K, et al. Diversity and inclusion among US emergency medicine residency programs and practicing physicians: towards equity in workforce. Am J Emerg Med. Published online August 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Smith S.G., Nsiah-Kumi P.A., Jones P.R., et al. Pipeline programs in the health professions, part 1: preserving diversity and reducing health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:836–851. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith S.G., Nsiah-Kumi P.A., Jones P.R., et al. Pipeline programs in the health professions, part 2: the impact of recent legal challenges to affirmative action. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:852–863. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gasman M., Smith T., Ye C., et al. HBCUs and the production of doctors. AIMS Public Health. 2017;4:579–589. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2017.6.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heron S., Haley L.L., Jr. Diversity in emergency medicine—a model program. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choo E.K., Kass D., Westergaard M., et al. The development of best practice recommendations to support the hiring, recruitment, and advancement of women physicians in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/acem.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powers A., Gerull K.M., Rothman R., et al. Race-and gender-based differences in descriptions of applicants in the letters of recommendation for orthopaedic surgery residency. JB JS Open Access. 2020;5 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00023. e20.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson S.K., Hekman D.R., Chan E.T. If there’s only one woman in your candidate pool, there’s statistically no chance she’ll be hired. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;26 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez J.E., Campbell K.M., Pololi L.H. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell K.M., Rodríguez J.E. Addressing the minority tax: perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94:1854–1857. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dandar V.M., Lautenberger D.M., Garrison G.E. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. Promising Practices for Understanding and Addressing Salary Equity at US Medical Schools. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carter K.R., Crewe S., Joyner M.C., et al. NAM Perspectives, Commentary. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2020. Educating Health Professions Educators to Address the “isms”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardeman R.R., Medina E.M., Boyd R.W. Stolen breaths. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:197–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soares W.E., III, Knowles K.J., Friedmann P.D. A thousand cuts: racial and ethnic disparities in emergency medicine. Med Care. 2019;57:921–923. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clinical Emergency Data Registry American College of Emergency Physicians. https://www.acep.org/cedr/ Available at: Accessed December 28, 2020.

- 55.Hanchate A.D., Paasche-Orlow M.K., Baker W.E., et al. Association of race/ethnicity with emergency department destination of emergency medical services transport. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10816. e1910816-e1910816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin M.H. Advancing health equity in patient safety: a reckoning, challenge and opportunity. BMJ Qual Saf. Published online December. 2020;29 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shavers V.L., Shavers B.S. Racism and health inequity among Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:386–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brondolo E., Brady N., Thompson S., et al. Perceived racism and negative affect: analyses of trait and state measures of affect in a community sample. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2008;27:150–173. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feagin J. Routledge; 2013. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samuels-Kalow M.E., Ciccolo G.E., Lin M.P., et al. The terminology of social emergency medicine: measuring social determinants of health, social risk, and social need. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:852–856. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Screening for Social Needs Guiding Care Teams to Engage Patients. American Hospital Association. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/09/screening-for-social-needs-tool-value-initiative-rev-9-26-2019.pdf Available at: Accessed April 25, 2021.

- 62.Samuels-Kalow M.E., Boggs K.M., Cash R.E., et al. Screening for health-related social needs of emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fichtenberg C.M., Alley D.E., Mistry K.B. Improving social needs intervention research: key questions for advancing the field. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(Suppl 1):S47–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gruen R.L., Campbell E.G., Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296:2467–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Internal Revenue Service Community Health Needs Assessments for Charitable Hospitals. Department of the Treasury; 2013. Document Number 2013-07959. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/04/05/2013-07959/community-health-needs-assessments-for-charitable-hospitals Available at: Accessed January 5, 2021.

- 66.Holistic Review Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review#:∼:text=Holistic%20Review%20refers%20to%20mission,learning%2C%20practice%2C%20and%20teaching Available at: Accessed April 26, 2021.

- 67.LaVeist T.A., Pierre G. Integrating the 3Ds—docial determinants, health disparities, and health-care workforce diversity. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:9–14. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davis D., Dorsey J.K., Franks R.D., et al. Do racial and ethnic group differences in performance on the MCAT exam reflect test bias? Acad Med. 2013;88:593–602. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318286803a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucey C.R., Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351–356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pager D., Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:181–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Okonofua J.A., Walton G.M., Eberhardt J.L. A vicious cycle: a social-psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016;11:381–398. doi: 10.1177/1745691616635592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hahn R.A., Truman B.I., Williams D.R. Civil rights as determinants of public health and racial and ethnic health equity: health care, education, employment, and housing in the United States. SSM Popul Health. 2018;4:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riddle T., Sinclair S. Racial disparities in school-based disciplinary actions are associated with county-level rates of racial bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:8255–8260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808307116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas B.R., Dockter N. Affirmative action and holistic review in medical school admissions: where we have been and where we are going. Acad Med. 2019;94:473–476. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Staton L.J., Panda M., Chen I., et al. When race matters: disagreement in pain perception between patients and their physicians in primary care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:532–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoffman K.M., Trawalter S., Axt J.R., et al. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Braun L., Wentz A., Baker R., et al. Racialized algorithms for kidney function: erasing social experience. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113548. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Franciosa J.A., Taylor A.L., Cohn J.N., et al. African-American heart failure trial (A-HeFT): rationale, design, and methodology. J Card Fail. 2002;8:128–135. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.124730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sankar P., Kahn J. BiDil: race medicine or race marketing? Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:W5-455–W5-463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reverby S.M. “Special treatment”: BiDil, Tuskegee, and the logic of race. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kahn J. In: Race and the Genetic Revolution: Science, Myth, and Culture. Krimsky S., Sloan K., editors. Columbia University Press; 2011. BiDil and racialized medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Braun L., Fausto-Sterling A., Fullwiley D., et al. Racial categories in medical practice: how useful are they? PLoS Med. 2007;4:e271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bailey Z.D., Krieger N., Agénor M., et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ending Structural Racism. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/ending-structural-racism Available at: Accessed April 25, 2021.

- 85.Motor Vehicle Safety: An Update for Emergency Medicine Practitioners. American College of Emergency Physicians. Available at: https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/preps/motor-vehicle-safety-an-update-for-emergency-medicine-practitioners---prep.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.