Abstract

Purpose

Prematurity Immunology in Mothers living with HIV and their infants Study (PIMS) is a prospective cohort study in South Africa investigating the association between antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, preterm delivery (PTD) and small-for-gestational age (SGA) live births. PIMS main hypotheses are that ART initiation in pregnancy and ART-induced hypertension are associated with PTD and SGA respectively and that reconstitution of cellular immune responses in women on ART from before pregnancy results in increases in PTD of GA infants.

Participants

Pregnant women (n=3972) aged ≥18 years regardless of HIV status recruited from 2015 to 2016 into the overall PIMS cohort (2517 HIV-negative, 1455 living with HIV). A nested cohort contained 551 women living with HIV who were ≤24 weeks’ GA on ultrasound: 261 initiated ART before pregnancy, 290 initiated during the pregnancy.

Findings to date

Women in the overall cohort were followed antenatally through to delivery using routine clinical records; further women in the nested cohort were actively followed up until 12 months post partum, with data collected on maternal health (HIV care and ART use, clinical care and intercurrent clinical history). Other procedures conducted on the nested cohort included physical examinations (anthropometry, blood pressure measurement), assessment of fetal growth (ultrasound), maternal and infant phlebotomy for storage of plasma, RNA and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, collection of delivery specimens (placenta and cord blood) and infant 12-month developmental assessment. Preliminary findings have contributed to our understanding of risk factors for adverse birth outcomes, and the relationship between pregnancy immunology, HIV/ART and adverse birth outcomes.

Future plans

Using specimens collected from study participants living with HIV throughout pregnancy and first year of life, the PIMS provides a valuable platform for answering a variety of research questions focused on temporal changes of immunology markers in women whose immune status is altered by HIV infection, and how ART initiated during the pregnancy affects immune responses. The relationship between these immunological changes with adverse birth outcomes as well as possible longer-term impact of exposure to ART in fetal and early life will be explored. Additionally, further active and passive follow-up of mothers and their infants is planned at school-going age and beyond to chart growth, morbidity and development, as well as changes in family circumstances.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, epidemiology, immunology, maternal medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Robust measurement of gestational age (GA) early in pregnancy by research sonographer for the GA assessment in women ≤24 weeks when ultrasound is highly reproducible and accurate.

Ability to track patients using the Western Cape unique identifier across different health and laboratory services, enables passive long-term follow-up of women and their infants; with available data including patient-level data (administrative, demographic and clinical), visit-level data (clinical observations and findings), laboratory tests and medication.

Maternal biological specimens, collected three or four times over pregnancy for the cohort of women living with HIV enrolled before 20 weeks gestation, enable immunological, metabolomic and placental investigations will inform understanding of mechanisms underlying adverse birth outcomes in women living with HIV.

One of the first studies to combine metabolomic and immunological assessments in infant biological specimens which will provide an integrated model of the immune-metabolism association in HIV-exposed infants and the consequences of maternal metabolic dysregulation for the immune responses of the infant.

Absence of HIV-uninfected or antiretroviral therapy (ART)-unexposed comparator groups for immunological investigations, which could hinder distinguishing ART exposure from HIV disease.

Introduction

Antiretroviral drugs in pregnant women living with HIV (WLHIV) prevent mother-to-child transmission and delay HIV disease progression. WHO guidelines now recommend antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all, immediately on HIV diagnosis, including for WLHIV during the pregnancy and breastfeeding, to be continued lifelong.1 However, infants born to WLHIV would be exposed to multidrug ART regimen for prolonged periods at a crucial time during their development,2 which could result in decreased health, developmental and survival outcomes.3 4 In high maternal HIV prevalence settings, the increasing population of ART-exposed infants could make the goal of under-five mortality reduction less likely.

Adverse birth outcomes contribute significantly to under-five mortality, as well as infant health and developmental problems.5 There is an ongoing debate regarding the association between exposure to maternal ART during fetal life and adverse birth outcomes, following reports from Europe,6–9 USA10 and Africa11–14 of possible ART-associated increased risk of preterm delivery (PTD), small-for-gestational age (SGA) or low birthweight (LBW) infants. Furthermore, these exposed infants are also at increased risk of acquiring viral infections,15 16 as well as the negative impact of ART on fetal brain development and function.17 Interpretation of findings from various studies, especially from African settings, is hindered by the reliability of gestational assessment, with ultrasound (US) dating in early pregnancy usually unavailable.

There is limited understanding of general pregnancy-related immune changes in high HIV prevalence settings. Successful pregnancies require intricate fetal–maternal (FM) immune balances, to enable maternal tolerance of the semiallogeneic fetus; this FM tolerance is primarily maintained by the placenta.18 19 Consequently, adverse birth outcomes could be hypothesised to be due to placental interface FM tolerance disruption because of cytokine shifts associated with ART initiation causing early initiation of uterine contractions.20 Additionally, there are suggestions that adverse birth outcomes could also be associated with ART-induced dysregulation of maternal and infant metabolism. In order to meet the specific needs during the pregnancy and infancy, metabolism is tightly regulated, but ART is known to interfere with lipid metabolism.21 The emerging field of immunometabolism has shown that alterations in the lipid profile increases susceptibility to viral infections by skewing immune responses towards an inflammatory profile. The complex interplay between pregnancy, HIV/ART, host immunity, adverse birth outcomes and long-term child health is poorly understood as detailed data are sparse and often related to drug combinations which are no longer be in use. Further research is required to examine epidemiological and immunological associations and inform understandings of underlying biological mechanisms giving rise to adverse birth outcomes.

An increase in PTD rates, and especially of SGA infants, could impact on the long-term growth and development of children, and would have consequences for the health and well-being of their families and population more widely. We, therefore, aimed to improve understanding of maternal immune profiles during the pregnancy in the context of ART use during gestation, adverse birth outcomes and long-term child health in Cape Town, South Africa, an area of high HIV prevalence.

This manuscript presents the details of the setting up of the cohort, including aims and objectives and a description of baseline findings along with other preliminary findings.

Aim and objectives

The primary focus of the Prematurity Immunology in Mothers living with HIV and their infants Study (PIMS) was to investigate and quantify the risk of preterm and SGA deliveries; with underlying hypotheses that (1) timing of ART use (from before or during the pregnancy) is associated with increased risk of PTD, (2) ART-induced hypertension during the pregnancy results in increased risk of SGA and (3) reconstitution of cellular immune responses during ART in pregnancy results in increases in PTD of appropriate-for-GA (AGA) infants. Our secondary focus was to determine long-term (first 5 years of life) child health outcomes of PTD infants (by weight at GA and maternal HIV/ART status). Our hypotheses are that (1) throughout childhood SGA infants are disadvantaged in terms of growth and development compared with preterm AGA infants and (2) ART use alters maternal and fetal lipid metabolism resulting in susceptibility to infections and alterations in vaccine responses in childhood.

Cohort description

Setting

Between April 2015 and October 2016, we enrolled pregnant women (aged ≥18 years) at their first antenatal care (ANC) visit in a prospective cohort study, at a single large public sector primary care facility (Gugulethu Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU)) in a low-income high HIV-prevalence subdistrict of Cape Town, South Africa.

Study design

The overall prospective, observational design includes two ‘nested’ groups of pregnant women:

Group 1: the overall population of pregnant women (≥18 years) seeking ANC services at Gugulethu MOU during an 18-month period; within this group, a subset of women thought to be ≤24 weeks’ gestation based on history or examination (clinical GA) underwent US scan by a research sonographer for more accurate gestation estimation; enrolled into observation group.

-

Group 2: all pregnant WLHIV seeking ANC who are ≤24 weeks’ gestation at US at their first ANC visit, regardless of current ART use at the first ANC visit (nested within group 1). Enrolled into longitudinal cohort with data collection through questionnaires, clinical assessments and phlebotomy spanning pregnancy to early infancy.

This study design enables quantification of the risk of adverse birth outcomes in the overall cohort, as well as the more detailed group 2 also enabling investigation of the consequences of the immune response following ART initiation in pregnancy for onset of labour and PTD.

Patient public involvement

No patient involvement.

Routine care services

As part of routine ANC services, GA was estimated based on date of last menstrual period (LMP) and symphysis-fundal height (SFH) by public sector midwives. All women without a previous HIV diagnosis underwent HIV testing, with universal ART eligibility. WLHIV conceiving while on ART continued their current regimen throughout pregnancy; regimens included non-nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) such as efavirenz (EFV) or protease inhibitor (PI, predominantly used after failure of first-line therapy). For women initiating ART in pregnancy, a fixed-dose combination of tenofovir (TDF)+emtricitabine (FTC)+EFV was used throughout.

Recruitment

Following screening of all women attending their first ANC visit, those ≥18 years were eligible and approached to participate in the study. Following screening, ineligible women were referred back to their ANC clinics in line with the Western Cape Department of Health’s healthcare model. Women who agreed to participate had their routinely collected LMP-based GA and SFH-based GA reviewed by the counsellor; women estimated to be ≤24 weeks were referred for a research US scan for formal pregnancy dating by a research sonographer blinded to the midwife assessment. WLHIV who were ≤24 weeks’ gestation on US were then recruited into a nested cohort (group 2); half of these had initiated lifelong ART prior to conception and half initiated ART during the pregnancy.

All participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation, with reconsenting of mother–infant pairs at the first postpartum visit for paediatric follow-up. Consent for study participation included data abstraction from routine clinical records through the pregnancy and postpartum period.

Participant baseline characteristics

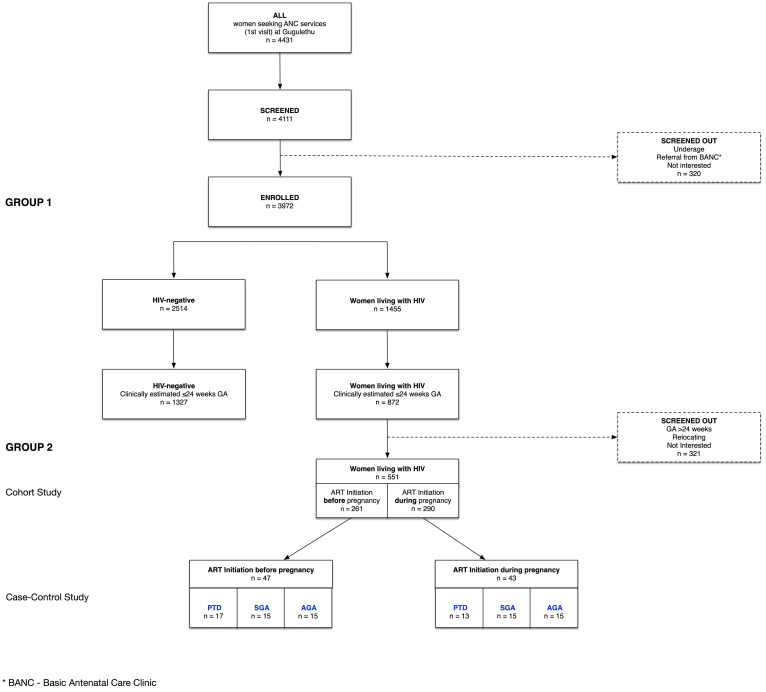

A total of 4431 women registered for ANC during the study recruitment period, of whom 4111 (93%) were screened for the study and 3972 (90%) enrolled; all delivered by May 2017 (figure 1). Main reasons for being screened out were under-age, referrals from Basic Antenatal Clinics or not being interested. Of the enrolled women, 2517 (63.4%) were HIV-negative and 1455 (36.6 %) WLHIV (table 1); 2199 (55.4%) were referred for US based on their clinical GA, 1327 (60.3%) were HIV-negative and 872 (39.7%) living with HIV.

Figure 1.

Cohort profile. AGA, appropriate-for-gestational age; ART, antiretroviral therapy; GA, gestational age; PTD, preterm delivery; SGA, small-for-gestational age.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of group 1 women at first antenatal care visit (n=3972)

| Total N=3972 |

HIV-negative N=2517 |

Living with HIV N=1455 |

P value | Living with HIV N=1455 |

P value | ||

| Initiated before pregnancy N=722 |

Initiated during pregnancy N=733 |

||||||

| Age, years | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| <24 | 1273 (32) | 987 (39) | 286 (20) | 112 (16) | 174 (24) | ||

| 25–29 | 1108 (28) | 702 (28) | 406 (28) | 157 (22) | 249 (34) | ||

| >30 | 1591 (40) | 828 (33) | 763 (52) | 453 (63) | 310 (42) | ||

| Median | 28 (23–32) | 26 (22–31) | 30 (25–34) | 31 (27–35) | 28 (25–32) | ||

| Height, cm | 0.221 | 0.562 | |||||

| ≤155 | 1173 (30) | 723 (29) | 450 (31) | 220 (30) | 230 (31) | ||

| 156–161 | 1344 (34) | 873 (35) | 471 (32) | 245 (34) | 226 (31) | ||

| ≥162 | 1049 (26) | 661 (26) | 388 (27) | 190 (27) | 198 (27) | ||

| Missing | 406 (10) | 256 (10) | 147 (10) | 67 (9) | 79 (11) | ||

| Median | 158 (154–162) | 158 (154–162) | 158 (154–162) | 158 (154–162) | 158 (154–162) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.666 | 0.535 | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 26 (0.7) | 15 (0.6) | 11 (0.7) | 8 (1) | 3 (0.4) | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 718 (18) | 457 (18) | 261 (18) | 124 (17) | 137 (19) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1007 (25) | 625 (25) | 381 (26) | 202 (28) | 180 (25) | ||

| Obese (>30.0) | 1790 (55) | 1148 (47) | 801 (55) | 313 (43) | 329 (55) | ||

| Missing | 431 (11) | 272 (11) | 159 (11) | 75 (10) | 84 (11) | ||

| Median | 30 (26–35) | 30 (26–35) | 30 (26–35) | 30 (26–35) | 30 (25–35) | ||

| Gravidity | <0.0001 | 0.002 | |||||

| 1 | 967 (24) | 726 (29) | 241 (17) | 100 (14) | 141 (19) | ||

| 2 | 1347 (34) | 849 (34) | 498 (34) | 238 (33) | 260 (35) | ||

| ≥3 | 1567 (39) | 887 (35) | 680 (47) | 368 (51) | 312 (43) | ||

| Missing | 91 (2) | 55 (2) | 36 (3) | 16 (2) | 20 (3) | ||

| Median | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | ||

| Parity | <0.0001 | 0.011 | |||||

| 0 | 1194 (30) | 865 (34) | 329 (23) | 147 (20) | 182 (25) | ||

| 1 | 1458 (37) | 898 (36) | 560 (38) | 270 (37) | 290 (40) | ||

| ≥2 | 1228 (31) | 699 (28) | 529 (36) | 289 (40) | 240 (33) | ||

| Missing | 92 (2) | 55 (0.1) | 37 (3) | 16 (2) | 21 (3) | ||

| Median | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | ||

| Previous preterm | 0.013 | 0.617 | |||||

| Yes | 280 (7) | 159 (6) | 121 (8) | 63 (9) | 58 (8) | ||

| Haemoglobin g/L | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Normal (≥110) | 1446 (36) | 961 (38) | 485 (33) | 289 (40) | 196 (27) | ||

| Mild anaemia (90–109) |

1067 (27) | 638 (25) | 429 (29) | 177 (25) | 252 (34) | ||

| Moderate anaemia (70–89) |

229 (6) | 109 (4) | 120 (8) | 47 (7) | 73 (10) | ||

| Severe anaemia (<70) | 5 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Missing | 1225 (31) | 805 (32) | 420 (29) | 209 (29) | 211 (29) | ||

| Gestational age assessment | |||||||

| LMP | 3479 (88) | 2219 (88) | 1260 (87) | 0.150 | 642 (89) | 618 (84) | 0.010 |

| Median (weeks) | 17 (12–22) | 17 (12–23) | 16 (11–22) | 15 (11–22) | 17 (12–22) | ||

| SFH | 2327 (59) | 1447 (57) | 880 (60) | 0.065 | 403 (56) | 477 (65) | <0.0001 |

| Median (weeks) | 23 (18–28) | 23 (19–28) | 22 (17–27) | 22 (16–27) | 23 (18–28) | ||

| US | 2334 (59) | 1411 (56) | 923 (63) | <0.0001 | 433 (60) | 490 (67) | 0.006 |

| Median (weeks) | 16 (12–21) | 16 (12–21) | 15 (11–20) | 14 (10–19) | 17 (12–21) | ||

n (%).

LMP, last menstrual period; SFH, symphysis fundal height; US, ultrasound.

Median age at enrolment was 28 years (IQR 23–32), with HIV-negative women younger than WLHIV women, and those initiating ART preconception older than WLHIV initiating ART during the pregnancy. In line with age differences, WLHIV were of higher gravidity than HIV-negative women, but the difference in parity was small; women who initiated ART prepregnancy were of a higher gravidity than those initiating during the pregnancy. A quarter (25%) of all women were overweight, while over half (55%) were obese, with little or no difference between groups. Having previously had a PTD was more common among WLHIV than HIV-negative women. Mild anaemia was relatively common in all groups, especially in women initiating ART during the pregnancy (table 1). Overall, 3479 (87.6%) women had gestation estimated by LMP, 2327 (58.6%) by SFH and 2334 (58.8%) by US; with estimated median GA at enrolment visit varying by assessment method (table 1).

There were 1455 WLHIV in group 1; 718 (49.3%) were ≤24 weeks on US, of whom 551 were enrolled into group 2 (figure 1). The likelihood of inclusion into group 2 did not differ by baseline characteristics (table 2). In comparison to group 1 participants, group 2 participants differed in age, gravidity, parity and previous PTD, likely driven by the HIV-negative women (table 3). In multivariable regression allowing for HIV infection, the only difference that persisted between these groups was age (table 4). When group 2 women were compared with other WLHIV (not enrolled in group 2), they were slightly older, more likely to have normal haemoglobin levels (≥110 g/L) and lower GA (table 3). In multivariable regression the only difference between these groups that persisted was GA, which was a group 2 inclusion criterion (table 4).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of group 2 eligible but not enrolled versus group 2 women at first antenatal care visit

| Group 2 eligible N=718 |

P value | ||

| Not enrolled N=167* |

Enrolled N=551 |

||

| Age, years | 0.274 | ||

| <24 | 37 (22) | 92 (17) | |

| 25–29 | 44 (26) | 156 (28) | |

| >30 | 86 (52) | 303 (55) | |

| Median | 30 (25–33) | 30 (26–34) | |

| Height, cm | 0.395 | ||

| ≤155 | 53 (32) | 166 (33) | |

| 156–161 | 54 (32) | 191 (35) | |

| ≥162 | 33 (20) | 145 (26) | |

| Missing | 27 (16) | 49 (9) | |

| Median | 157 (153–161) | 158 (154–162) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.920 | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1 (0.01) | 5 (0.01) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 32 (19) | 103 (19) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 35 (21) | 134 (24) | |

| Obese (>30.0) | 71 (43) | 255 (46) | |

| Missing | 28 (17) | 54 (10) | |

| Median | 30 (25–34) | 30 (25–36) | |

| Gravidity | 0.204 | ||

| 1 | 35 (21) | 90 (16) | |

| 2 | 57 (34) | 184 (33) | |

| ≥3 | 67 (40) | 263 (48) | |

| Missing | 8 (5) | 14 (3) | |

| Median | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | |

| Parity | 0.290 | ||

| 0 | 48 (29) | 129 (23) | |

| 1 | 62 (37) | 222 (40) | |

| ≥2 | 49 (29) | 185 (34) | |

| Missing | 8 (5) | 15 (3) | |

| Median | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | |

| Previous preterm† | 0.100 | ||

| Yes | 9 (6) | 52 (9) | |

| Haemoglobin g/dL | 0.084 | ||

| Normal (≥11.0) | 46 (28) | 232 (42) | |

| Mild anaemia (9–10.9) | 44 (26) | 153 (28) | |

| Moderate anaemia (7–8.9) | 11 (7) | 26 (5) | |

| Severe anaemia (<7) | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing | 66 (40) | 140 (25) | |

| ART status | 0.577 | ||

| Initiated before pregnancy | 55 (92) | 290 (53) | |

| Initiated during pregnancy | 75 (45) | 261 (47) | |

| Gestational age assessment | |||

| LMP | 148 (89) | 481 (87) | 0.648 |

| Median (weeks) | 13 (10–17) | 13 (9–17) | |

| SFH | 87 (57) | 258 (47) | 0.232 |

| Median (weeks) | 17 (14–20) | 17 (14–20) | |

| US | 167 (100) | 551 (100) | |

| Median (weeks) | 14 (10–18) | 13 (10–17) | |

n (%).

*Eligible for group 2 based on US, but not enrolled into group 2.

†Among women with a previous pregnancy.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; LMP, last menstrual period; SFH, symphysis fundal height; US, ultrasound.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of group 1 versus group 2 women at first antenatal care visit

| Group 1 | Group 2 | P value Group 1 vs group 2 |

P value HIV+ vs group 2 |

||

| HIV-negative N=2517 |

*Living with HIV N=904 |

Living with HIV N=551 |

|||

| Age, years | <0.0001 | 0.078 | |||

| <24 | 987 (39) | 194 (21) | 92 (17) | ||

| 25–29 | 702 (28) | 250 (28) | 156 (28) | ||

| >30 | 828 (33) | 460 (51) | 303 (55) | ||

| Median | 26 (22–31) | 30 (25–33) | 30 (26–34) | ||

| Height, cm | 0.726 | 0.465 | |||

| ≤155 | 723 (29) | 284 (31) | 166 (30) | ||

| 156–161 | 873 (35) | 280 (31) | 191 (35) | ||

| ≥162 | 661 (26) | 243 (27) | 145 (26) | ||

| Missing | 260 (10) | 97 (11) | 49 (9) | ||

| Median | 158 (154–162) | 158 (154–163) | 158 (154–162) | ||

| Body mass idex, kg/m2 | 0.756 | 0.456 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 15 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 5 (1) | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 457 (18) | 158 (17) | 103 (19) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 625 (25) | 248 (27) | 134 (24) | ||

| Obese (>30.0) | 1148 (47) | 387 (43) | 255 (46) | ||

| Missing | 272 (11) | 105 (12) | 54 (10) | ||

| Median | 30 (26–35) | 30 (26–35) | 30 (25–34) | ||

| Gravidity | <0.0001 | 0.820 | |||

| 1 | 726 (29) | 151 (17) | 90 (16) | ||

| 2 | 849 (34) | 314 (35) | 184 (33) | ||

| ≥3 | 887 (35) | 417 (46) | 263 (48) | ||

| Missing | 55 (2) | 22 (2) | 14 (3) | ||

| Median | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | ||

| Parity | 0.004 | 0.236 | |||

| 0 | 865 (34) | 200 (22) | 129 (23) | ||

| 1 | 898 (36) | 338 (37) | 222 (40) | ||

| ≥2 | 699 (28) | 344 (38) | 185 (34) | ||

| Missing | 55 (0.1) | 22 (2) | 15 (3) | ||

| Median | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | ||

| Previous preterm† | <0.0001 | 0.182 | |||

| Yes | 159 (6) | 69 (8) | 52 (9) | ||

| Haemoglobin g/L | 0.007 | <0.0001 | |||

| Normal (≥110) | 961 (38) | 253 (28) | 232 (42) | ||

| Mild anaemia (90–109) | 638 (25) | 276 (31) | 153 (28) | ||

| Moderate anaemia (70–89) | 109 (4) | 94 (10) | 26 (5) | ||

| Severe anaemia (<70) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | ||

| Missing | 805 (32) | 280 (31) | 140 (25) | ||

| Gestational age assessment | |||||

| LMP | 2219 (88) | 779 (86) | 481 (87) | 0.823 | 0.542 |

| Median (weeks) | 17 (12–23) | 19 (13–24) | 13 (9–17) | ||

| SFH | 1447 (57) | 622 (69) | 258 (47) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Median (weeks) | 23 (19–28) | 25 (21–29) | 17 (14–20) | ||

| US | 1411 (56) | 376 (42) | 551 (100) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Median (weeks) | 16 (12–21) | 21 (13–25) | 13 (10–17) | ||

n (%).

*All women living with HIV not included in group 2.

†Among women with a previous pregnancy.

LMP, last menstrual period; SFH, symphysis fundal height; US, ultrasound.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics associated with inclusion in group 2 at first antenatal care (ANC) visit

| OR Group 1 (ref) vs group 2* |

OR Group 1 HIV+ (ref) vs group 2† |

|||||||

| OR | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | OR | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <24 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 25–29 | 2.10 (1.60–2.76) | <0.0001 | 2.23 (1.64 to 3.05) | <0.0001 | 1.32 (0.96–1.81) | 0.091 | 1.09 (0.65 to 1.83) | 0.758 |

| >30 | 3.02 (2.36–3.86) | <0.0001 | 3.37 (2.45 to 4.63) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.04–1.85) | 0.025 | 1.09 (0.66 to 1.81) | 0.740 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 0.70 (0.26–1.91) | 0.489 | 0.75 (0.27 to 2.06) | 0.573 | 0.78 (0.23–2.63) | 0.691 | 1.02 (0.14 to 7.37) | 0.988 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.64 (0.24–1.74) | 0.386 | 0.60 (0.22 to 1.65) | 0.324 | 0.65 (0.19–2.16) | 0.481 | 1.34 (0.19 to 9.65) | 0.773 |

| Obese (>30.0) | 0.70 (0.26–1.87) | 0.474 | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.52) | 0.255 | 0.79 (0.24–2.62) | 0.701 | 1.10 (0.15 to 7.84) | 0.923 |

| Gravidity | ||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 2 | 1.54 (1.18–2.01) | 0.001 | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.34) | 0.929 | 0.98 (0.72–1.35) | 0.917 | 1.08 (0.64 to 1.82) | 0.765 |

| ≥3 | 1.97 (1.52–2.53) | <0.0001 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.30) | 0.716 | 1.05 (0.78–1.43) | 0.715 | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.86) | 0.746 |

| Previous preterm‡ | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.50 (1.09–2.06) | 0.012 | 1.19 (0.84 to 1.68) | 0.318 | 1.29 (0.89–1.88) | 0.183 | 1.25 (0.69 to 2.26) | 0.468 |

| ART status | – | – | – | |||||

| Initiated during pregnancy | – | – | – | Reference | Reference | |||

| Initiated before pregnancy | – | – | – | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) | 0.180 | 1.07 (0.76 to 1.51) | 0.705 | |

| Gestational age | – | – | – | |||||

| Weeks | – | – | – | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | <0.0001 | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) | <0.0001 | |

*Comparison between all enrolled pregnant women (≥18 years) seeking ANC services at Gugulethu MOU (group 1) (n=3421) vs pregnant women living with HIV ≤24 weeks’ gestation enrolled into cohort (group 2) (n=551).

†Comparison between all enrolled pregnant women living with HIV (≥18 years) seeking ANC services at Gugulethu MOU (group 1) not enrolled in cohort (n=167) vs pregnant women living with HIV ≤24 weeks’ gestation enrolled into cohort (group 2) (n=551).

‡Among women with a previous pregnancy.

§aOR - adjusted Odds Ratio

aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; ART, antiretroviral therapy; MOU, midwife obstetric unit.

Of the 551 WLHIV in group 2, 261 (47%) initiated before pregnancy and 290 (53%) initiated during the pregnancy (table 5). Women who initiated ART during the pregnancy were on average younger, and of lower gravidity. Overall, three-quarters of group 2 women were overweight or obese, with little difference by ART status. Of the women who initiated ART during the pregnancy, the majority (64%) had tested HIV positive in the index pregnancy; the rest had previously tested positive although were not on ART at conception. In line with local and WHO treatment guidelines, most women (91%) were on a regimen of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (TDF +FTC), plus NNRTI EFV. PI usage in this cohort was low, at only 9% of women who initiated pre-pregnancy and 1% of women who initiated during the pregnancy. Median CD4 count was 433 cells/µL overall, 527 cells/µL in women who initiated ART before pregnancy and 373 cells/µL in women initiating at the first antenatal visit. There were no differences in smoking or drug usage between these two groups of women, but women who initiated during the pregnancy were more likely to have ever consumed alcohol or consumed in the last 30 days (table 5).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of group 2 women at first antenatal care (ANC) visit (n=551)

| Total N=551 |

Living with HIV | P value | ||

| Initiation before pregnancy N=261 |

Initiation during pregnancy N=290 |

|||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | <0.0001 | |||

| ≤24 | 92 (17) | 25 (10) | 67 (23) | |

| 25–29 | 156 (28) | 58 (22) | 98 (34) | |

| ≥30 | 303 (55) | 178 (68) | 125 (43) | |

| Median (IQR) | 30 (26–34) | 32 (28–36) | 29 (25–32) | |

| Education (finished high school) | 164 (30) | 96 (33) | 69 (26) | 0.088 |

| Employment status | 0.767 | |||

| Employed | 238 (46) | 114 (44) | 124 (43) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1) | 0 | |

| Socio-economic Status | 0.694 | |||

| Lowest | 175 (32) | 82 (31) | 93 (32) | |

| Medium | 175 (32) | 88 (34) | 87 (30) | |

| Highest | 189 (34) | 87 (33) | 102 (35) | |

| Missing | 12 (2) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) | |

| Obstetric characteristics | ||||

| Gravidity | <0.0001 | |||

| 1 | 88 (16) | 29 (11) | 59 (20) | |

| 2 | 187 (34) | 78 (30) | 109 (38) | |

| ≥3 | 276 (50) | 154 (59) | 122 (42) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (2–3) | |

| Parity | 0.061 | |||

| 0 | 123 (22) | 49 (18) | 74 (26) | |

| 1 | 220 (40) | 99 (38) | 121 (42) | |

| ≥2 | 208 38) | 113 (43) | 95 (33) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | |

| Height, cm | 0.858 | |||

| ≤155 | 130 (24) | 64 (25) | 66 (23) | |

| 156–161 | 208 (38) | 96 (37) | 112 (39) | |

| ≥162 | 208 (38) | 99 (38) | 109 (38) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 160 (156–164) | 159 (155–163) | 160 (156–164) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.591 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 6 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 110 (20) | 47 (18) | 63 (22) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 148 (27) | 76 (29) | 72 (25) | |

| Obese (>30.0) | 282 (51) | 133 (51) | 149 (51) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 30 (26–35) | 30 (26–34) | 30 (25–35) | |

| Median gestation (completed weeks) | 14 (11–18) | 13 (11–17) | 14 (10–18) | 0.054 |

| HIV | ||||

| First tested HIV positive | <0.0001 | |||

| In this pregnancy | 186 (34) | 0 | 186 (64) | |

| Before this pregnancy | 365 (66) | 261 (100) | 104 (36) | |

| ART use history | <0.0001 | |||

| Newly diagnosed | 186 (34) | 0 | 186 (64) | |

| Known HIV+, no ART | 104 (19) | 0 | 104 (36) | |

| Known HIV+, on ART | 261 (47) | 261 (100) | 0 | |

| Current ART regimen, self-report | <0.0001 | |||

| TDF-3TC-EFV | 499 (91) | 220 (84) | 279 (96) | |

| TDF-3TC-NVP | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Other NNRTI-based regimen | 23 (4) | 16 (6) | 7 (2) | |

| PI-based regimen | 25 (4) | 23 (9) | 2 (1) | |

| CD4 cell count, cells/µL* | <0.0001 | |||

| ≤200 | 53 (10) | 13 (5) | 40 (14) | |

| 201–350 | 111 (20) | 37 (14) | 74 (26) | |

| 351–500 | 122 (22) | 53 (20) | 69 (24) | |

| >500 | 194 (34) | 120 (46) | 74 (26) | |

| Missing | 71 (13) | 38 (15) | 33 (11) | |

| Median (IQR) | 433 (298–600) | 527 (368–638) | 373 (246–519) | |

| VL, copies/mL* | 0.015 | |||

| <400 | 458 (83) | 234 (90) | 224 (77) | |

| 401–1000 | 14 (3) | 5 (2) | 9 (3) | |

| >1000 | 64 (12) | 21 (8) | 43 (15) | |

| Missing | 15 (3) | 1 (0.4) | 14 (5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 20 (20–67) | 20 (20–20) | 20 (20–100) | |

| Substance use | ||||

| Substance use, ever | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.014 | |||

| Yes | 357 (65) | 155 (59) | 202 (70) | |

| No | 189 (34) | 103 (39) | 86 (29) | |

| Missing | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Smoking | 0.123 | |||

| Yes | 56 (10) | 21 (8) | 35 (12) | |

| No | 490 (89) | 237 (91) | 253 (87) | |

| Missing | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Drugs | 0.146 | |||

| Yes | 11 (2) | 2 (1) | 9 (3) | |

| No | 534 (97) | 256 (98) | 278 (96) | |

| Missing | 6 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Substance use, last 30 days | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.061 | |||

| Yes | 105 (19) | 41 (16) | 64 (22) | |

| No | 439 (80 | 216 (83) | 223 (77) | |

| Missing | 7 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Smoking | 0.101 | |||

| Yes | 33 (6) | 11 (4) | 22 (7) | |

| No | 512 (93) | 246 (94) | 266 (92 | |

| Missing | 6 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Drugs | 0.101 | |||

| Yes | 3 (1) | 0 | 3 (1) | |

| No | 542 (98) | 257 (98) | 285 (98) | |

| Missing | 6 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | |

n (%).

*CD4 and VL results abstracted from routine records and are the nearest in time to the first ANC visit.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; NNRTI, Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NVP, Nevirapine; PI, protease inhibitor; 3TC, Lamivudine; VL, viral load.

Study follow-up

At baseline, all women (group 1) had clinical and medical history, routine first ANC visit physical examination, screening tests and GA assessment data collected via abstraction of the Maternity Case Record (MCR) booklet (table 5), which is a standardised patient-held maternity record used by all facilities providing maternity services to record clinical data from the antenatal through to postpartum period, including labour. The MCR also serves as a referral letter, thus serving as a link between antenatal and labour care. In addition, the National Health Laboratory Services database was searched for CD4, viral load results and other laboratory values not recorded in the MCR. Further follow-up for women in group 1, not eligible for group 2, was through data abstraction of the MCR following discharge from the postnatal ward (MCR retained at delivery facility). Data were abstracted from follow-up ANC notes, clinical notes during labour and newborn assessments (table 5).

Women in group 2 participated in up to eight scheduled study visits, from the start of ANC through to 12 months post partum. Women on ART from before pregnancy had three antenatal visits at <24 weeks, 28 and 34 weeks; women who initiated ART during the pregnancy had an additional study visit 2 weeks after the ART initiation (which in most women took place on the same day, or close to, the first study visit). Following delivery, women were reconsented for infant participation, and study visits were conducted <7 days, 10 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post partum. At all study visits, data were collected on maternal health (HIV care and ART use, clinical care and intercurrent clinical history). Other procedures included physical examinations (anthropometry, blood pressure measurement), phlebotomy (50 mL) for storage of plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and RNA; a follow-up US was conducted at 28 weeks to assess fetal growth (table 5).

At postpartum study visits, additional data were collected on infant health (including infant feeding and intercurrent clinical history) and physical examination of infants was conducted (basic anthropometry). At the 12-month visit, developmental assessment was conducted using the Ages and Stages questionnaire22—a general developmental screening tool testing five key areas: personal social, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving and communication skills. Infant specimen collection included Dried Blood Spot sampling and storage at 10 weeks study visit, and phlebotomy (2 mL) for measurement of immunological functioning and antibody responses to routine childhood immunisations (rotavirus and measles) at 12-month study visit. In addition, data on infant health status, including vaccinations, chemoprophylaxis use (including nevirapine and cotrimoxazole) and routine HIV PCR testing, was abstracted from Road-to-Health Booklets—patient-held booklet taken to all clinical and immunisation visits used to monitor infant growth and development until age 5 years (table 6).

Table 6.

Group 1 and group 2 measurements

| Phase | Measurements group 1 | Measurements group 2 |

| Baseline |

Routine care clinical record (MCR) abstraction:

|

Routine care clinical record (MCR) abstraction:

Study-specific data collection

|

| Follow-up |

Routine care clinical record abstraction:

MCR

|

Routine care clinical record abstraction: MCR

Infant Road-to-Health Booklet

Study-specific data collection Maternal

Infant

|

DBS, dried blood spots; MCR, maternity case record; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.;

Further active follow-up of the women and their infants will occur at school-going age and beyond to chart growth, morbidity and development, as well as changes in family circumstances. It is envisaged that subsequent to this, longer term follow-up will be passive through the use of routinely collected data. The Western Cape Provincial Department of Health’s public-sector patient administration systems all share unique health identifier23; data relating to participants health service contacts, health conditions and health outcomes for specific conditions will be obtained from the Provincial Health Data Centre, which consolidates person-level clinical data across government services.24

Data collection

An overview of the main included data collection instruments is presented in table 6, covering self-reported information on clinical history, ART use and adherence, and medical events; as well as information obtained from routinely collected data.

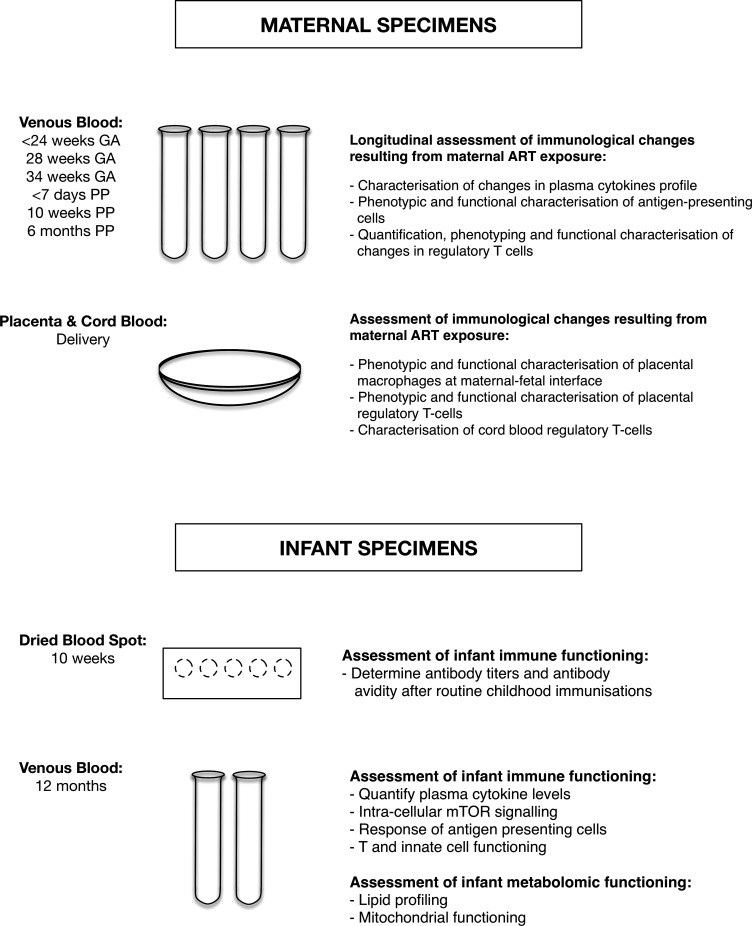

Specimen collection

To investigate the proposed hypothesis that immunological changes resulting from maternal ART exposure are associated with adverse birth outcomes, women enrolled into the follow-up cohort were intensively sampled, with repeated phlebotomy throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period for immunological investigations (table 7). Using samples from all antenatal plasma, inflammatory markers (C reactive protein, serum amyloid A and CCL10 (IP-10) in women are being measured. Further, following a nested case–control design in group 2 (n=90), investigations compare women who delivered preterm (PTD cases) or had SGA infants (SGA cases) and those from appropriate controls (term AGA) (matched for GA and ART status) (figure 1). Investigations include longitudinal quantification of plasma cytokine profiles, phenotypic and functional characterisation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), antigen-presenting cells and metabolites associated with mitochondrial functioning and lysophospholipids (figure 2). The combined studies of these immune parameters will inform understanding of ART use during the pregnancy on the areas of the immune system that have been shown to be critically involved in regulating maternal immune tolerance to the fetus and their associations with onset of labour and PTD.

Table 7.

Number of available specimens per study visit

| Specimen type | Specimen storage | Visits* | ||||||||

| A1 | A1.5 | A2 | A3 | Del | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | ||

| Maternal | ||||||||||

| PBMC | Sodium heparin | 463 | 227 | 445 | 419 | 405 | 412 | 403 | 364 | |

| EDTA | 466 | – | – | – | 344 | – | – | – | ||

| Plasma | Sodium heparin | 483 | 236 | 452 | 424 | 407 | 413 | 404 | 366 | |

| EDTA | 499 | – | – | – | 345 | – | – | – | ||

| PAXGene | 493 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Delivery | ||||||||||

| Placenta | Block | 229 | ||||||||

| OCT | 190 | |||||||||

| RNA sequencing | 176 | |||||||||

| RNA later | 146 | |||||||||

| Cord blood | ||||||||||

| PBMC | Sodium heparin | 161 | ||||||||

| Plasma | Sodium heparin | 161 | ||||||||

| Infant | ||||||||||

| DBS | – | – | 228 | 67 | 18 | |||||

| PBMC | Sodium heparin | – | – | – | 225 | |||||

| Plasma | Sodium heparin | – | – | – | 228 | |||||

*Study visits—A1 Enrolment; A1.5—2 weeks post-ART initiation; A2—28 weeks gestation; A3—34 weeks gestation; P1—7 days post partum, P2—10 weeks post partum; P3—6 months postpartum; P4—12 months postpartum.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DBS, dried blood spots; OCT, optimal cutting temperature; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Figure 2.

Maternal and infant specimens. GA, gestational age; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PP, post partum.

At delivery, placentas and cord bloods were collected whenever possible, a scoring algorithm was developed which graded placentas and dictated specimen processing according to membrane completeness and time received in laboratory relative to delivery time (table 8). Using flow cytometry and tissue immunostaining techniques the following investigations will be conducted: examination of the effect of HIV infection/ART exposure on the phenotypic characteristics and functionality of placental macrophages (Hofbauer cells and decidual macrophages) at the maternal–fetal interface and placental Tregs and their association with adverse birth outcomes. Characterisation of cord blood Tregs and correlation of their frequency, function and phenotype with placental Tregs and birth outcomes (figure 2).

Table 8.

Placenta scoring algorithm for histopathology and laboratory analyses

| Score | Description | Membranes | Time received* | Lab action |

| 1a | Good | Complete | <7 hours | Process

|

| 1b | Good | Incomplete | ||

| 2a | Good | Complete | 7–12 hours | |

| 2b | Good | Incomplete | ||

| 3 | Variable | Complete/incomplete | 12–24 hours | Process

|

| 4 | Variable | Complete/incomplete | 24–36 hours | Variable

|

| 5 | Variable | Complete/incomplete | >36 hours | Do not process 1. Fix for pathological analysis |

| 6 | Bad | Complete/incomplete | Do not process 2. Fix in formalin and discard |

*Relative to delivery time.

Study retention

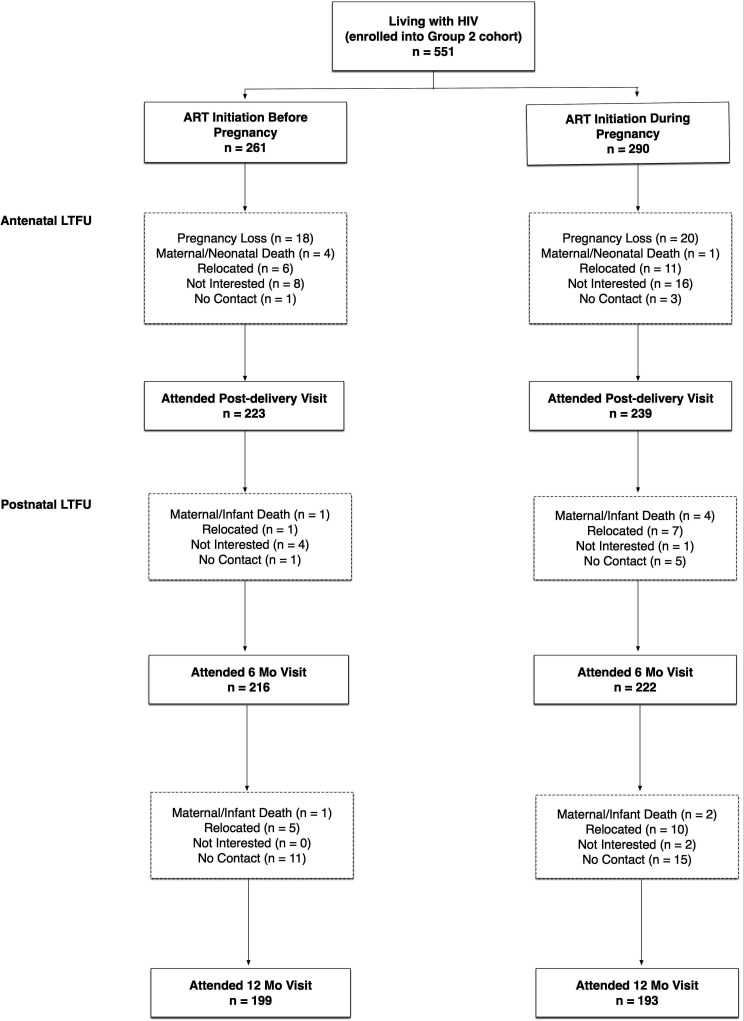

Lost to follow-up was categorised based on the last visit before the woman was lost; in total 158 (29%) women were lost to follow-up (LTFU) (figure 3). Women lost before the postdelivery study visit (n=88), either experienced pregnancy losses (n=37), were no longer interested in participating (n=24) or relocated out of the study area (n=17). For women LTFU between delivery and the 6-month postpartum visit (n=24), reasons included relocation (n=8), not contactable (n=6), no longer interested in participating (n=5) and maternal/infant death (n=5) (figure 2). For women LTFU between 6 months and 12 months post partum (n=46), reasons included relocation (n=15), not contactable (n=26), no longer interested in participating (n=2) and maternal/infant death (n=3).

Figure 3.

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) in group 2 cohort. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

There were no appreciable differences by ART status in women LTFU before postdelivery visit (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.19). However, women who initiated ART before pregnancy were less likely to be LTFU between delivery and 6 months postpartum (RR0.44, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.04) and between 6 months and 12 months post partum (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.02). No baseline characteristics were associated with LTFU.

Findings to date

GA assessment

In the overall cohort, 1787 women with live singleton births were included in the analysis of the association between HIV status and timing of ART initiation and PTD by GA assessment method used (LMP, measurement of SFH and US. Using US-GA, PTD risk was associated with maternal HIV infection and ART use, with WLHIV, on ART from before or early pregnancy, almost twice as likely to deliver preterm than HIV-negative women.25 A weaker association was observed when GA assessment was based on SFH; while with LMP-GA the difference by HIV status was minimal. We did not find any appreciable differences in the PTD risk for WLHIV by timing of ART initiation across all three assessment methods.25 Our findings (in both the overall cohort and in women with all three assessments) suggest that methods of GA assessment explain at least partially the heterogeneity of findings from previous studies on the association between ART use and adverse birth outcomes, suggesting that care should be taken when interpreting results from such studies.

Obesity

In the overall cohort, 2921 women with live singleton births were included in the analysis of the association between maternal body mass index and adverse birth outcomes. In a subset cohort the association between gestational weight gain (GWG) and adverse birth outcomes was examined. Maternal obesity was associated with increased likelihood of having high birthweight and large size for GA infants. In the subset cohort, GWG was associated with increased likelihood of spontaneous PTD and high birthweight infants.26 Obesity during the pregnancy is prevalent in this setting and appears associated with increased risk of adverse birth outcomes in both WLHIV and HIV-negative women.

Placental pathology

Preliminary analysis of placental histopathology from a subset of women enrolled in the prospective cohort showed significant associations between placental pathology and adverse birth outcomes: presence of focal infarction was associated with increased risk of LBW; the lower the weight of the basal plate weight lead to increased risk of LBW, PTD and SGA; and prolonged meconium exposure was associated with increased risk of SGA. These findings suggest that adverse birth outcomes are driven primarily by placental abnormalities which do not appear to be associated with the ART initiation timing.27 Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry staining were performed on these wax blocks to identify regulatory T cells along with macrophages. Further analysis is ongoing.

Within the placenta, investigation of the distribution of pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) placental macrophages at the maternal–fetal interface showed no differences in the tissue density of these macrophages within the decidual membranes and villous tissue according to timing of ART initiation. Data suggest that the Hofbauer cells (which are fetal macrophages) are not polarised into M1/M2 phenotypes but are rather ‘intermediate’ types.28

Strengths and limitations

Key strengths of the PIMS study include the recruitment of a large community-based cohort in an area of high HIV prevalence; the observational nature of the study provides good external validity of experiences of a public sector primary care population over pregnancy. A further strength lies in the use of a research sonographer for the GA assessment in women ≤24 weeks when US is highly reproducible and accurate (while routinely used clinical assessments are less reliable) which is particularly important when studying associations with adverse birth outcomes, as compromises in outcome ascertainment methods can affect the detection of the magnitude of associations.

Additionally, the maternal biological specimen from Group 2 at three or four times (depending on ART status group) throughout pregnancy and at delivery is an important strength because it enables immunological, metabolomic and placental investigations to inform understanding of mechanisms underlying adverse birth outcomes in in WLHIV. As pregnancy is a state of immunoregulation requiring tolerance of a semiallogeneic fetus, the assessment of placentas of enrolled women provides a unique opportunity to investigate the link between HIV, ART and adverse birth outcomes. Collection of infant specimens further strengthens the study as it is one of the first studies combining metabolomic and immunological assessments. This will provide an integrated model of the immune-metabolism association in HIV-exposed infants and the consequences of maternal metabolic dysregulation for the immune responses of the infant. Furthermore, the developmental assessments carried out in the infants provides the opportunity to consider the association between maternal immune function during the pregnancy and early childhood immunological and developmental outcomes.

PIMS has valuable subdesigns in addition to the observational study design with the overall cohort stratified by maternal HIV status, ART use, and related risk factors, with all details to be analysed by timing of ART initiation in line with the main PIMS objectives. One subdesign is the cohort study in women living with HIV, who have data collection through questionnaires, clinical assessments and phlebotomy spanning pregnancy to early infancy. This study design enables quantification of the risk of adverse birth outcomes in the overall cohort, as well as the more detailed group 2 group also enabling investigation of the consequences of the immune response following ART initiation in pregnancy for onset of labour and PTD. Another subdesign is the nested case–control study which will enable immunological investigations in women who did and did not delivery preterm/SGA infant. The ability to track patients using the Western Cape unique identifier across different health and laboratory services, enables the passive long term follow-up of the group 2 women and their infants; with available data including patient-level data (administrative, demographic and clinical), visit-level data (clinical observations and findings), laboratory tests and medication.

A limitation of the study is while HIV-negative women are included in group 1, providing a comparison group for birth outcome and various maternal characteristics, group 2 did not include HIV-negative or ART-unexposed comparator groups. As such the detailed immunological analyses over pregnancy are limited to WLHIV, with timing of ART initiation a main explanatory variable. Additionally, we do not have full detailed information on all group 1 women and were instead limited by routinely collected data in medical notes some information relating to maternal characteristics was based on self-report and thus subject to potential biases. In order to address this limitation, routinely collected data were also collected to confirm data on birth outcomes.

Findings to date

Using data collected from study participants living with HIV throughout pregnancy and first year of life, PIMS provides a valuable platform for answering a variety of research questions related to maternal and child health. In particular, PIMS well equipped to investigate temporal changes of immunology markers in women whose immune status is altered by HIV infection, and how ART initiated during the pregnancy affects immune responses. The relationship between these immunological changes with adverse birth outcomes as well as possible longer-term impact of exposure to ART in fetal and early life will be explored. Additionally, through use of the Western Cape Department of Health unique identifier further active and passive follow-up of mothers and their infants is planned at school-going age and beyond to chart growth, morbidity and development, as well as changes in family circumstances.

The PIMS investigators welcome new collaborations with other investigators interested in using study data and stored specimens. Interested investigators should contact M-LN (M.Newell@soton.ac.uk) and LM (Landon.Myer@uct.ac.za) to obtain additional information and discuss collaborative opportunities. Proposed projects and data analyses plans will be reviewed to ensure no overlap with planned projects and efficient use of data and specimens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to all mothers who took part in this study. We acknowledge the Gugulethu Midwife Obstetric Unit staff and the whole research team including Hlengiwe Madlala, Colin Newell, Megan Mrubata and Lee-Ann Stemmet for their valuable input and contribution.

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published online. References 27 and 28 are now amended.

Collaborators: Mushi MatjilaThumbi N’DunguChristina Thobakgale Marcus AltveldMadeleine BundersHlengiwe MadlalaMax KroonGreg Petro

Contributors: TRM, LM, CG and M-LN: Conceptualisation and design of the study. TRM: Study conduct, data collection and statistical analysis. TRM and M-LN: Interpretation of data and writing the manuscript. TRM, LM, CG and M-LN: review and editing

Funding: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health grant number R01HD080385.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data collected in this study will be available to external investigators interested in collaboration upon submission and approval of a data analysis plan. The samples are being used by the named investigators, but remaining samples can be made available to external users. Requests for data and available samples within PIMS, or to submit a request for additional data collection, should be submitted to M.Newell@soton.ac.uk and Landon.Myer@uct.ac.za and will be reviewed by the study steering committee.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (UCT HREC 739/2014) and the University of Southampton Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (12542 PIMS).

References

- 1.WHO . Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva, Switzwerland: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS . On the fast-track to an AIDS-free generation 2016.

- 3.Brennan AT, Bonawitz R, Gill CJ, et al. A meta-analysis assessing all-cause mortality in HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected infants and children. AIDS 2016;30:2351–60. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.le Roux SM, Abrams EJ, Nguyen K, et al. Clinical outcomes of HIV-exposed, HIV-uninfected children in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2016;21:829–45. 10.1111/tmi.12716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015;385:430–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin F, Taylor GP. Increased rates of preterm delivery are associated with the initiation of highly active antiretrovial therapy during pregnancy: a single-center cohort study. J Infect Dis 2007;196:558–61. 10.1086/519848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibiude J, Warszawski J, Tubiana R, et al. Premature delivery in HIV-infected women starting protease inhibitor therapy during pregnancy: role of the ritonavir boost? Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:1348–60. 10.1093/cid/cis198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorne C, Patel D, Newell M-L. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in HIV-infected women treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe. AIDS 2004;18:2337–9. 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and premature delivery in diagnosed HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom and ireland. AIDS 2007;21:1019–26. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328133884b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter AM, Garcia AG, Duthely ML, et al. Is antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, or stillbirth? J Infect Dis 2006;193:1195–201. 10.1086/503045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. J Infect Dis 2012;206:1695–705. 10.1093/infdis/jis553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler MG, Qin M, Fiscus SA, et al. Benefits and risks of antiretroviral therapy for perinatal HIV prevention. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1726–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1511691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li N, Sando MM, Spiegelman D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in relation to birth outcomes among HIV-infected women: a cohort study. J Infect Dis 2016;213:jiv389. 10.1093/infdis/jiv389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powis KM, Kitch D, Ogwu A, et al. Increased risk of preterm delivery among HIV-infected women randomized to protease versus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HAART during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 2011;204:506–14. 10.1093/infdis/jir307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slogrove AL, Cotton MF, Esser MM. Severe infections in HIV-exposed uninfected infants: clinical evidence of immunodeficiency. J Trop Pediatr 2010;56:75–81. 10.1093/tropej/fmp057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotton MF, Slogrove A, Rabie H. Infections in HIV-exposed uninfected children with focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33:1085–6. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Doaré K, Bland R, Newell M-L. Neurodevelopment in children born to HIV-infected mothers by infection and treatment status. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1326–44. 10.1542/peds.2012-0405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Varea A, Pellicer B, Perales-Marín A, et al. Relationship between maternal immunological response during pregnancy and onset of preeclampsia. J Immunol Res 2014;2014:1–15. 10.1155/2014/210241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svensson-Arvelund J, Mehta RB, Lindau R, et al. The human fetal placenta promotes tolerance against the semiallogeneic fetus by inducing regulatory T cells and homeostatic M2 macrophages. J Immunol 2015;194:1534–44. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiore S, Newell M-L, Trabattoni D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy-associated modulation of Th1 and Th2 immune responses in HIV-infected pregnant women. J Reprod Immunol 2006;70:143–50. 10.1016/j.jri.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontas E, van Leth F, Sabin CA, et al. Lipid profiles in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy: are different antiretroviral drugs associated with different lipid profiles? J Infect Dis 2004;189:1056–74. 10.1086/381783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Squires J, Bricker DD, Twombly E. Ages & stages questionnaires. Baltimore, MD, USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck EJ, Shields JM, Tanna G, et al. Developing and implementing National health identifiers in resource limited countries: why, what, who, when and how? Glob Health Action 2018;11:1440782. 10.1080/16549716.2018.1440782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulle A, Heekes A, Tiffin N, et al. Data centre profile: the provincial health data centre of the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Int J Popul Data Sci 2019;4:1143. 10.23889/ijpds.v4i2.1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaba TR, Newell M-L, Madlala H, et al. Methods of gestational age assessment influence the observed association between antiretroviral therapy exposure, preterm delivery, and small-for-gestational age infants: a prospective study in Cape Town, South Africa. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28:893–900. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madlala HP, Malaba TR, Newell M-L, et al. Elevated body mass index during pregnancy and gestational weight gain in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Cape Town, South Africa: association with adverse birth outcomes. Trop Med Int Health 2020;25:702–13. 10.1111/tmi.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray C M, Ross M C, Chanzu N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy is associated with increased placental inflammation and small for gestational age neonates: a prospective study. IAS, ed. Paris: 9th IAS Conference on HIV Science, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zulu MZ, Chanzu N, Fick L, et al. Differential distribution of M1 and M2 Macrophages in the decidua and chorionic villi of placentas from HIV-1 infected mothers on combination antiretroviral therapy. IAS, ed. Paris: 9th IAS Conference on HIV Scienc, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data collected in this study will be available to external investigators interested in collaboration upon submission and approval of a data analysis plan. The samples are being used by the named investigators, but remaining samples can be made available to external users. Requests for data and available samples within PIMS, or to submit a request for additional data collection, should be submitted to M.Newell@soton.ac.uk and Landon.Myer@uct.ac.za and will be reviewed by the study steering committee.