Abstract

Objective

This review will examine the clinical relevance and pathophysiology of Boston keratoprosthesis (B-KPro)-related corneal keratolysis (cornea melt) and to describe a novel method of preventing corneal melt using ex vivo crosslinked cornea tissue carrier.

Methods

A review of B-KPro literature was performed to highlight cases of corneal melt. Studies examining the effect of corneal collagen crosslinking on the biomechanical properties of corneal tissue are summarized. The use of cross-linked corneal tissue as carrier to the B-KPro is illustrated with a case.

Results

Corneal melting after B-KPro is a relatively rare event, occurring in 3% of eyes during the first three years of postoperative follow-up. The risk of post-KPro corneal melting is heightened in eyes with chronic ocular surface inflammation such as eyes with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and mucous membrane pemphigoid. This chronic inflammation results in high tear levels of matrix metalloproteinases, the enzymes responsible for collagenolysis and corneal melt. Crosslinked corneal tissue has been shown to have stiffer biomechanical properties and to be more resistant to degradation by collagenolytic enzymes. We have previously optimized the technique for ex vivo corneal collagen crosslinking and are currently studying its impact on the prevention of corneal melting after B-KPro surgery in high-risk eyes. Crosslinked carrier tissue was used in a 52 year-old male with familial aniridia and severe post-KPro corneal melt. The patient maintained his visual acuity and showed no evidence of corneal thinning or melt in the first postoperative year.

Conclusion

Collagen crosslinking was previously shown to halt the enzymatic degradation of corneal buttons ex vivo. This study demonstrates the safety and potential benefit of using crosslinked corneal grafts as carriers for the B-KPro, especially in eyes at higher risk of postoperative melt.

Keywords: corneal collagen crosslinking, keratoprosthesis, keratolysis, aniridia

CORNEA MELTING & THE BOSTON KERATOPROSTHESIS

Corneal melting, or sterile keratolysis, is an uncommon, but potentially sight-threatening complication following Boston keratoprosthesis type I (B-KPro) surgery. Corneal melting is reported to occur in 3 to 18% of eyes in the most recent case series.1-4 The importance of this complication is highlighted by the fact that corneal melting is responsible for 43 to 82% of cases of KPro removal or replacement.1,4 Furthermore, severe melting may lead to the spontaneous extrusion of the KPro, which may be accompanied by infection or loss of the intraocular contents. Such devastating complications abolish future hopes of visual rehabilitation.

The high variability in melt rates is explained by the fact that certain diagnoses have a significantly higher risk of post-KPro melting. Cicatricial autoimmune diseases, such as mucous membrane pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, have long been recognized as having a worse prognosis following B-KPro surgery.5 In these eyes, smoldering ocular surface inflammation may persist for years after disease onset. Notably, high levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a pro-inflammatory cytokine and potent inducer of MMPs, has been found in the conjunctiva of eyes with mucous membrane pemphigoid.6 Autoimmune eyes with mucous membrane pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome also have high levels of tear film biomarkers of inflammation such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-8, MMP-9, myeloperoxidase when compared to controls.7 MMP-8, MMP-9 and myeloperoxidase remain elevated in the tear film of autoimmune eyes several years after B-KPro implantation.8 As MMPs are the enzymes responsible for the breakdown of extracellular matrix involved in corneal melt, the constitutively elevated levels of MMP are thought to explain the higher risk of melt in these diseases. For example, aqueous leak or device extrusion occurred in 62.5% of eyes implanted with B-KPro type I for mucous membrane pemphigoid.9 Similarly, a 25% rate of aqueous leak in eyes with either B-KPro type I or type II was reported for Stevens-Johnson syndrome-related keratopathy.10

While corneal melting is most likely to occur in eyes with persistent inflammation of the ocular surface, some cases of post-KPro melt occur in eyes with non-inflammatory and non-cicatricial diagnoses. For example, retroprosthetic membrane (RPM) has recently been identified as a factor contributing to sterile keratolysis.11 It is hypothesized that, much like the previous PMMA backplate without fenestrations, RPM acts as a barrier to nutrient diffusion from the aqueous humor to the corneal stroma. As such, thicker RPM are much more likely to cause nutrient deficiency of keratocytes and its consequent sterile melting. While the rate 30 to 50% of RPM formation following B-KPro remains significant, the frequency of RPM is expected to decrease with the more widespread use of titanium back plates.1,2,12,13 More recently, the use of oversized 9.5 mm titanium back plates has proven to be a promising strategy toward the elimination of RPM.14

The management algorithm for corneal melt post-KPro includes the optimization of ocular surface lubrication, the use of anti-collagenases and reparative surgery. Collagenase inhibitors in current use are limited to topical (0.1%) and systemic doxycycline as well as topical medroxyprogesterone (1%). Systemic immunosuppression may be warranted to suppress the inflammatory cascade leading to collagenase activation.15 With severe melting, surgical intervention is often necessary. Several approaches to reparative surgery have been reported. These include lamellar or full thickness tectonic grafts,15 amniotic membrane transplantation16,17 and mucous membrane grafts.18 In relentlessly progressive cases, B-KPro explantation and replacement by a full-thickness corneal graft may be the only way to prevent B-KPro extrusion and loss of the globe.15

The B-Kpro design and management continue to evolve to decrease the incidence of cornea melts. For example, the introduction of a fenestrated polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) back plate led to a five-fold decrease in the rate of melting.19 Extended wear contact lens are also used to prevent ocular surface dessication.19,20 Despite these efforts, cornea melts persist. An ideal approach would be to avoid melting altogether through the use of highly resistant corneal carriers. For this purpose, the preoperative corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) of the graft tissue to be used as a carrier to B-KPro is a promising technique which has been used in a few patients to date.21

THE BIOMECHANICAL IMPACT OF CORNEAL COLLAGEN CROSSLINKING

Corneal collagen crosslinking using riboflavin and ultraviolet A (UVA) light is used in several countries to arrest progression of corneal ectasias such as keratoconus.22 The procedure involves imbibition of the corneal stroma with 0.1% riboflavin followed by exposure to UVA light. Riboflavin acts as a photosensitizer, which upon exposure to UVA light, leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species. It is postulated that singlet oxygen-dependent chemical reactions lead to the formation of intrafibrillar and interfibrillar covalent bonds, but not interlamellar ones.23 The strengthening of several biomechanical properties of the cornea supports the formation of such crosslinks. Crosslinked corneas are stiffer,24,25 have collagen fibers of larger diameter,26,27 as well as decreased tissue permeability.28 Moreover, crosslinked corneas show a higher resistance to enzymatic digestion.29,30

The standard protocol for corneal collagen crosslinking was developed in Dresden, Germany. This protocol includes epithelial debridement and application of 0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran for 5 minutes prior to and every 5 minutes during irradiation with UVA light. UVA irradiation using light of 370 nm and 3 mW/cm2 irradiance placed at 1 cm from the corneal was performed for 30 minutes.22 Several modifications have been applied to the Dresden protocol. For example, longer exposure to riboflavin prior to irradiation,31 trans-epithelial crosslinking,32,33 the application of riboflavin through an intrastromal pocket 34,35 as well as higher fluence, shorter duration protocols36 have been described. Each of these modifications in protocol may alter the clinical and biomechanical impact of crosslinking. For example, transepithelial crosslinking may be less effective in halting the progression of keratoconus when compared to the traditional epithelium-off technique.37 Similarly, the intrastromal application of riboflavin using a femtosecond laser-created pocket leads to a 50% reduction in biomechanical stiffening when compared to de-epithelialization and instillation of riboflavin drops.35 Further, the crosslinking reaction appears to be non-linear, with possible collagen damage with longer UVA exposures. In one study, the application of standard fluence UVA for 60 minutes instead of 30 minutes did not improve the stress-strain curve when compared to untreated corneas.38 More recently, high irradiance/short duration UVA exposure was shown to induce less stiffening than standard fluence treatments in an ex vivo porcine corneal model.39 These findings highlight the limitations of the Bunsen-Roscoe law, which has previously been used to validate the implementation high irradiance/short duration crosslinking protocols. This law states that the biological effect of a photochemical reaction is directly proportional to the total energy dose and is independent of irradiance and exposure time. Within other fields of photobiology, the Bunsen-Roscoe law is known to operate within relatively narrow conditions.40 In corneal collagen crosslinking, the limited rate of oxygen diffusion through corneal tissue is likely to impact the formation of reactive oxygen species and ultimately, the amount of crosslinks formed. Thus, further studies are required to determine a safe crosslinking protocol that optimizes both the biomechanical and biochemical stability of the cornea as well as the efficiency of application into clinical practice.

CORNEAL COLLAGEN CROSSLINKING TO PREVENT CORNEAL MELTS

Shortly after the introduction of collagen crosslinking for ectatic disorders of the cornea, similar protocols were applied to the treatment of infectious corneal ulceration. Successful outcomes have been reported in the setting of aggressive ulcers that were unresponsive to medical therapy.41-45 The success rate in bacterial keratitis appears to be higher than in fungal, protozoal and viral etiologies.46,47 Notably, a case of progressive and severe corneal melting with impending perforation has been described following collagen crosslinking for herpetic keratitis.48 To our knowledge, there are no published reports regarding the use of collagen crosslinking in cases of active sterile corneal melting.

There are two main putative mechanisms of action for riboflavin/UVA inhibition of infectious corneal ulceration. The first mechanism involves direct damage to the microbial genome through the formation of reactive oxygen species.49 The second mechanism involves the enhanced resistance of crosslinked tissue to microbial invasion and to digestion by microbial and host-derived collagenases.29 This second mechanism is of relevance to the current review. Indeed, a few in vitro studies have demonstrated that collagen crosslinking confers heightened resistance against enzymatic digestion to the corneal stroma.29,30

Spoerl et al investigated the resistance of crosslinked porcine cornea to enzymatic digestion by pepsin, trypsin and collagenase.29 The crosslinking protocol involved corneal epithelial debridement and application of 0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran for 5 minutes before irradiation and every 5 minutes during UVA exposure. UVA light with an irradiance of either 1, 2 or 3 mW/cm2 was applied at a 1 cm distance from the cornea for 30 minutes. Enzymatic digestion of the control, non-crosslinked corneas occurred earlier than in the crosslinked corneas. A dose-response was evident as the time to digestion for crosslinked corneas followed the level UVA irradiance: corneas exposed to 3 mW/cm2 irradiance exhibited the strongest resistance to degradation for all three of the tested enzymes.

In a study designed to investigate the optimal ex vivo preparation of corneal tissue for use as carriers to the B-KPro and tectonic procedures, different corneal collagen crosslinking protocols were assessed with regards to the time to complete tissue digestion by collagenase A.30 Human corneal donors were placed on an artificial anterior chamber, de-epithelialized and pre-treated with 0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran every 2 minutes for 15 minutes. Riboflavin application continued every 5 minutes during UVA application. The UVA light source was place 54 mm from the cornea and had a fixed irradiance of 3 mW/cm2. UVA exposure to the anterior corneal surface varied from 7.5 to 90 minutes. UVA treatment of the posterior corneal surface as well as crosslinking of gamma-irradiated corneal tissue was also investigated. Optimal resistance to collagenase A-mediated keratolysis was obtained following the 30-minute UVA exposure, where the time to tissue dissolution was increased by a factor of three when compared to control. No difference in resistance was seen between the 30-minute group and those with longer UVA exposures. Crosslinking of the posterior corneal surface did not yield any additional benefit and interestingly, prior gamma-irradiation seemed to cancel the anti-collagenolytic effect of riboflavin/UVA crosslinking.

Collagen crosslinking-induced resistance to corneal melt was demonstrated in vivo using a rabbit model of corneal alkali burn.50 In this study, corneal collagen crosslinking was performed using a standard protocol (0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran applied every 5 minutes for 30 minutes followed by every 3 minutes during exposure to UVA 3 mW/cm2, 45 mm from cornea for 30 minutes) after induction of the alkali burn using 1 M sodium hydroxide. Corneal crosslinking was associated with reductions in collagen fiber damage and inflammatory cells tissue infiltration. As well, corneal melting occurred in a smaller proportion of crosslinked corneas (10% versus 80% in the non-crosslinked control group) and showed decreased severity and delayed onset of melting.

Finally, a recent case series supports the long-term safety and efficacy regarding the application of crosslinked corneas as carriers for the B-KPro. Kanellopoulos and Asimellis treated 11 patients with B-KPro using a crosslinked carrier.21 Most of these patients had a high risk of melt because of underlying inflammatory ocular surface disease such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (36%) and chemical burn (18%). Interestingly, a novel CXL treatment protocol was applied to donor corneas mounted on an artificial anterior chamber. This protocol involved two separate riboflavin/ high fluence UVA applications. To target the posterior corneal stroma, riboflavin was injected into a deep femtosecond laser-dissected stromal pocket. After a first application of UVA (30 mW/cm2 for 4 minutes), the donor epithelium was debrided and riboflavin was applied topically, thus targeting the anterior stroma. Despite a very long mean follow-up of 7.5 years, melting of the carrier cornea did not occur in any of the cases.

CROSSLINKED CARRIERS FOR THE B-KPRO: A CASE REPORT

A 52-year old male patient with familial aniridia complicated by corneal blindness and chronic angle closure glaucoma had been managed at our center with bilateral KPro implantation. A PMMA back plate was used for the left eye. The right eye, which was operated 7 months later, received a titanium back plate. The patient had significant meibomian gland dysfunction, which was treated with continuous use of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. His initial postoperative eye drops included vancomycin 14 mg/mL, polymyxin B sulfate/trimethoprim, prednisolone acetate 1% four times daily as well as brimonidine twice daily.

Postoperatively, the patient wore colored contact lenses (CL, 8.3 mm base curve, 15 mm diameter, black iris with 5 to 6 mm pupil, Kontur Kontact Lens, Hercules, CA) to manage photophobia and maintained a visual acuity (VA) between 20/100-20/200 in both eyes. The patient developed RPM bilaterally, requiring Neodymium: yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser membranectomy at postoperative month (POM) 34 for the right eye and POM 20 and 64 for the left eye. As well, borderline intraocular pressures (IOP) and increased optic nerve cupping were noticed 5 years after the initial surgery, warranting the cessation of prednisolone acetate 1% and the addition of dorzolamide and timolol eye drops.

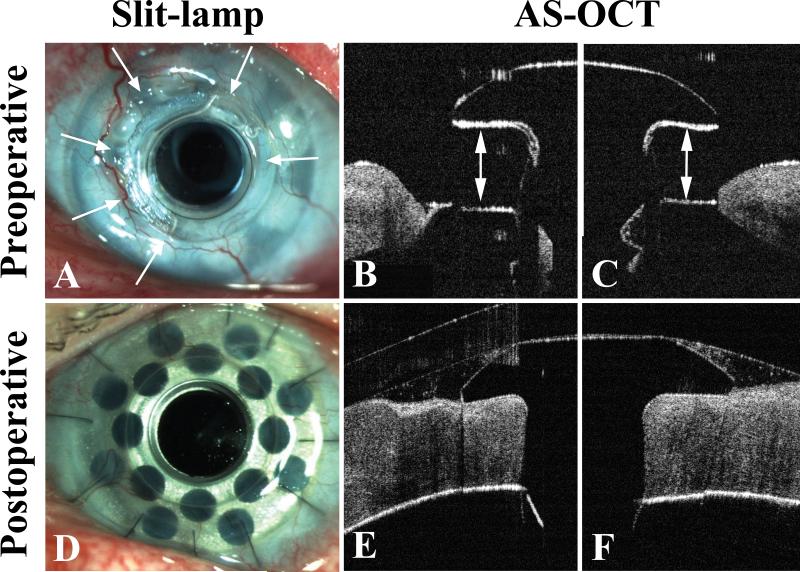

At postoperative 6 years and 3 months, significant melting of the superonasal periprosthetic carrier graft of the left eye was noted on routine clinical exam (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, the onset of the melting remained unclear as the patient denied any ocular symptoms and many of the prior exams had been performed without removal of the colored CL. The melting led to exposure of the backplate and underlying RPM. The identification of RPM as a factor contributing to sterile keratolysis is important and explains, in part, why sterile melting occurred in this patient with aniridia, a non-inflammatory and non-cicatricial diagnosis.11 Indeed, aniridia has been identified as a risk factor for RPM formation following B-KPro.13

Figure 1.

A) Anterior segment slit-lamp photography showing sterile melting of periprosthetic carrier graft from 7 to 2 o'clock. Basal extrusion of the Boston Keratoprosthesis type 1 (KPro) can be seen as the KPro front plate is elevated from the surrounding corneal tissue. A faint retroprosthetic membrane (RPM) is visible through the optical cylinder while a denser RPM is seen obstructing the fenestrations of the backplate. B) and C) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) at 9 (B) and 12 o'clock (C) illustrating severe keratolysis with exposure of the KPro backplate. Arrows indicate the area of melt. D) Anterior segment slit-lamp photography showing an intact KPro and carrier graft 3 months after KPro exchange using a crosslinked corneal donor. E) and F) AS-OCT at 9 (E) and 12 o'clock (F) demonstrating complete re-epithelialization, excellent graft-PMMA apposition and no evidence of periprosthetic melting or thinning at postoperative 1 year.

Since the IOP was maintained at 10-15 mm Hg and there was no active leak, the patient was initially managed with topical medroxyprogesterone 1% and doxycycline 0.1% four times daily. After 6.5 months of topical therapy, there appeared to be no filling of the corneal defect. Indeed, the melting seemed to have progressed slowly and now extended over 5 contiguous clock hours. Surgical intervention was deemed necessary at this point. KPro exchange using a crosslinked corneal graft as carrier to limit the risk of recurrent melt was offered. This procedure was approved by the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Human Studies Committee and written informed consent from the patient was obtained.

The CXL was performed under sterile conditions on the day of surgery. The corneoscleral rim was placed on an artificial anterior chamber and bathed in balanced salt solution. A 0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran solution was applied to the de-epithelialized cornea every 2 to 3 minutes for 15 minutes. A CMB VEGA X-linker (CSO, Florence, Italy) was used as ultraviolet A (UVA) source. The donor cornea was irradiated at a distance of 54 mm with 5.4 joules/cm2 using a wavelength of 370 nm with a radiance of 3 mW/cm2. Total treatment time was 30 minutes, with additional riboflavin drops instilled every 5 minutes during UVA exposure.30 The donor tissue was the placed in optisol GS for the next hour in preparation for surgery.

The KPro implantation, which was combined with pars plana vitrectomy and implantation of an Ahmed glaucoma drainage device, was uneventful. As customary, central trephination of the donor was performed using a 3 mm dermatologic punch and a small amount of Healon (AMO, Abbott Park, IL) was used to lubricate the stem prior to KPro-donor assembly. The snap-on KPro design with a 8.5 mm titanium backplate and locking ring was used. The assembly of the KPro and donor graft was very similar to that using a non-crosslinked carrier. The only difference was a notable increase in the corneal stroma's resistance to suture passage. A Kontur contact lens (9.8 mm base curve, 16 mm diameter) was placed at the end of surgery.

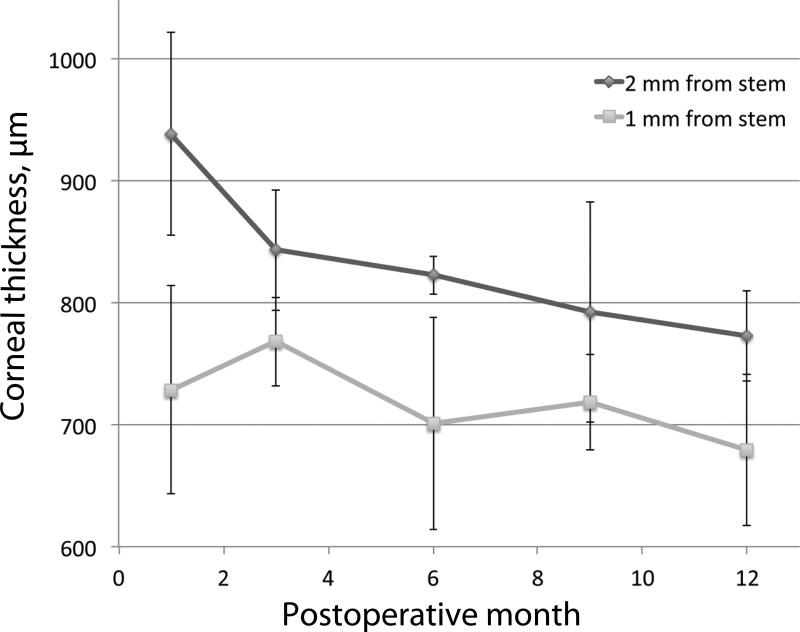

The patient did well postoperatively. Vancomycin 14 mg/mL, polymyxin B – trimethoprim and prednisolone acetate 1% were used four times daily. He continued the brimonidine, dorzolamide, timolol and doxycycline as prescribed preoperatively. Complete corneal re-epithelialization was achieved within the first postoperative month. Vancomycin was discontinued at POM 2. The polymyxin B – trimethoprim was tapered to twice daily and the prednisolone acetate to once daily by POM 4. The doxycycline eye drops were stopped at POM 11 as there was no evidence of recurrent melt. However, an early RPM had developed by POM 9. At 1 year of follow-up, the patient had maintained his pre-melt VA of 20/150. Serial slit-lamp photographs and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT; RTVue, Optovue, Fremont, CA) performed over the first year of follow-up showed no evidence of inflammation or stromal thinning (Fig. 1). The AS-OCT images demonstrate excellent apposition at the KPro-donor junction up to 1 year postoperatively. Corneal thickness was measured at predetermined locations (1 and 2 mm from the KPro stem at 3, 6, 9 and 12 o'clock) using the RTVue software. The evolution of corneal thickness over the first postoperative year is shown (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Average carrier graft thickness over the first year of postoperative follow-up. Average corneal thickness was calculated at each visit using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) measurements made 1 and 2 mm away from the KPro stem at 3, 6, 9 and 12 o'clock. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Conclusion

The use of crosslinked corneas for KPro has multiple advantages. The carrier, made highly resistant to local collagenases,29,30 may be better suited for eyes at high risk of melt or with ongoing melt. Indeed, this resistance to collagenases may be crucial to allow the graft to survive until post-surgical surface re-epithelialization occurs. Furhter, the use of crosslinked carriers does not expose the patient to risks higher than those of standard KPro surgery. Corneal haze and endothelial damage, both possible complications of collagen crosslinking, are of no consequence when relating to B-KPro.51 The crosslinking procedure is performed ex vivo prior to KPro surgery, with no patient or operating room staff exposure to UVA. The assembly of the KPro-crosslinked donor has proven to be feasible and quite straightforward when compared to the use non-crosslinked tissue.

In conclusion, this review describes the clinical significance of corneal melt after B-KPro and addresses the mechanical and biological properties of crosslinked corneal tissue relevant to the use of crosslinked donor corneas as carriers to B-KPro. The feasibility and safety of using crosslinked corneal donors as carrier for the B-KPro is illustrated through the use of a case report. This procedure is an interesting, sight-saving procedure in eyes at high risk of sterile melting following B-KPro or as a rescue procedure for ongoing B-KPro-related melt. In addition, ex vivo crosslinking may have benefits beyond the B-KPro. The use of crosslinked, collagenase-resistant corneal transplants may also offer hope to patients with recurrent or persistent ulcerative keratitis that require tectonic or conventional keratoplasty. Further investigation in the form of a prospective controlled trial is warranted to demonstrate efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by NEI 1K08EY019686-01 (JBC), Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund (JBC), New England Cornea Transplant Fund (JBC), Kpro Fund (JBC) and by a Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc (JBC).

Footnotes

Financial interest: None of the authors have any proprietary or financial interest in the products discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Aldave AJ, Sangwan VS, Basu S, et al. International Results with the Boston Type I Keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1530–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greiner MA, Li JY, Mannis MJ. Longer-term vision outcomes and complications with the Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis at the University of California, Davis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Paz M, Stoiber J, de Rezende Couto Nascimento V, et al. Anatomical survival and visual prognosis of Boston type I keratoprosthesis in challenging cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciolino JB, Belin M, Todani A, Al-Arfaj K, Rudnisky C, Boston Keratoprosthesis Type 1 Study Group Retention of the Boston keratoprosthesis type 1: multicenter study results. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaghouti F, Nouri M, Abad JC, Power WJ, Doane MG, Dohlman CH. Keratoprosthesis: preoperative prognostic categories. Cornea. 2001;20:19–23. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordero Coma M, Yilmaz T, Foster C. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in conjunctivae affected by ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:753–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arafat S, Suelves A, Spurr-Michaud S, et al. Neutrophil collagenase, gelatinase, and myeloperoxidase in tears of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert M, Arafat S, Spurr-Michaud S, Chodosh J, Dohlman C, Gipson I. Tear Matrix Metalloproteinases and Myeloperoxidase Levels Following Boston Keratoprosthesis Type I surgery. ARVO abstract. 2014 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000893. Program number 4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palioura S, Kim B, Dohlman CH, Chodosh J. The Boston keratoprosthesis type I in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Cornea. 2013;32:956–961. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318286fd73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayegh RR, Ang LPK, Foster CS, Dohlman CH. The Boston Keratoprosthesis in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;145:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivaraman KR, Hou JH, Allemann N, de la Cruz J, Cortina MS. Retroprosthetic Membrane and Risk of Sterile Keratolysis in Patients With Type I Boston Keratoprosthesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:814–822.e812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todani A, Ciolino JB, Ament JD, et al. Titanium back plate for a PMMA keratoprosthesis: clinical outcomes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1515–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1684-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudnisky CJ, Belin MW, Todani A, et al. Risk Factors for the Development of Retroprosthetic Membranes with Boston Keratoprosthesis Type 1. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:951–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruzat A, Shukla A, Dohlman C, Colby K. Wound anatomy after type 1 Boston KPro using oversized back plates. Cornea. 2013;32:1532–1536. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a854ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Utine C, Tzu J, Akpek E. Clinical Features and Prognosis of Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis-associated Corneal Melt. Ocular Immunology & Inflammation. 2011;19:413–418. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.621580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tay E, Utine CA, Akpek E. Crescenteric amniotic membrane grafting in keratoprosthesis-associated corneal melt. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:779–782. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navas A, Hernandez-Bogantes E, Serna-Ojeda J, Ramirez-Miranda A, Graue-Hernández E. Boston type I Keratoprosthesis assisted with intraprosthetic amniotic membrane (AmniotiKPro sandwich technique). Acta Ophthalmol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/aos.12423. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziai S, Rootman D, Slomovic A, Chan C. Oral buccal mucous membrane allograft with a corneal lamellar graft for the repair of Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis stromal melts. Cornea. 2013;32:1516–1519. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a480f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harissi-Dagher M, Khan BF, Schaumberg DA, Dohlman CH. Importance of nutrition to corneal grafts when used as a carrier of the Boston Keratoprosthesis. Cornea. 2007;26:564–568. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318041f0a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harissi-Dagher M, Beyer J, Dohlman CH. The role of soft contact lenses as an adjunct to the Boston keratoprosthesis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48:43–51. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318169511f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanellopoulos A, Asimellis G. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of High-Fluence Collagen Crosslinking of the Vehicle Cornea in Boston Keratoprosthesis Type 1. Cornea. 2014 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000176. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet A-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:620–627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Mazzota C, Kalinski T, Sel S. Interlamelar cohesion after corneal crosslinking using riboflavin and ultraviolet A light. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:876–880. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.190843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohlhaas M, Spoerl E, Schilde T, Unger G, Wittig C, Pillunat L. Biomechanical evidence of the distribution of cross-links in corneas treated with riboflavin and ultraviolet A light. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.12.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spoerl E, Huhle M, Seiler T. Induction of cross-links in corneal tissue. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:97–103. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wollensak G, Wilsch M, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Collagen fiber diameter in the rabbit cornea after collagen crosslinking by riboflavin/UVA. Cornea. 2004;23:503–507. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000105827.85025.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mencucci R, Marini M, Paladini I, et al. Effects of riboflavin/UVA corneal cross-linking on keratocytes and collagen fibres in human cornea. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart J, Schultz D, Lee O, Trinidad M. Collagen cross-links reduce corneal permeability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1606–1612. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spoerl E, Wollensak G, Seiler T. Increased resistance of crosslinked cornea against enzymatic digestion. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29:35–40. doi: 10.1080/02713680490513182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arafat S, Robert M, Shukla A, Dohlman C, Chodosh J, Ciolino J. UV Crosslinking of Donor Corneas Confers Resistance to Keratolysis. Cornea. 2014 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000185. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittig-Silva C, Chan E, Islam F, Wu T, Whiting M, Snibson G. A randomized, controlled trial of corneal collagen cross-linking in progressive keratoconus: Three-year results. Ophthalmology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.028. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filippello M, Stagni E, O'Brart D. Transepithelial corneal collagen crosslinking: bilateral study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baiocchi S, Mazzotta C, Cerretani D, Caporossi T, Caporossi A. Corneal crosslinking: riboflavin concentration in corneal stroma exposed with and without epithelium. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiliç A, Kamburoglu G, Akinci A. Riboflavin injection into the corneal channel for combined collagen crosslinking and intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;38:878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollensak G, Hammer C, Spörl E, et al. Biomechanical efficacy of collagen crosslinking in porcine cornea using a femtosecond laser pocket. Cornea. 2014;33:300–305. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanellopoulos A. Long term results of a prospective randomized bilateral eye comparison triall of higher fluence, shorter duration ultraviolet A radiation, and riboflavin collagen cross linking for progressive keratoconus. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2012;6:97–101. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S27170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kocak I, Aydin A, Kaya F, Koc H. Comparison of transepithelial corneal collagen crosslinking with epithelium-off crosslinking in progressive keratoconus. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014;37:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanchares E, del Buey M, Cristobal J, Labvilla L, Calvo B. Biomechanical property analysis after corneal collagen cross-linking in realtion to ultraviolet A irradiation time. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1223–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammer A, Richos O, Arba Mosquera S, Tabibian D, Hoogewoud F, Hafezi F. Corneal biomechanical properties at different corneal cross-linking (CXL) irradiances. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:2881–2884. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schindl A, Rosado-Schlosser B, Trautinger F. [Reciprocity regulation in photobiology. An overview]. Hautarzt. 2001;52:779–785. doi: 10.1007/s001050170065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Micelli Ferrari T, Leozappa M, Lorusso M, Epifani E, Micelli Ferrari L. Escherichia coli keratitis treated with ultraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking: a case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:295–297. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morén H, Malmsjö M, Mortensen J, Ohrström A. Riboflavin and ultraviolet A collagen crosslinking of the cornea for the treatment of keratitis. Cornea. 2010;29:102–104. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31819c4e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Sabai N, Koppen C, Tassignon M. UVA/riboflavin crosslinking as treatment for corneal melting. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2010;315:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iseli H, Thiel M, Hafezi F, Kampmeier J, Seiler T. Ultraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking for infectious keratitis associated with corneal melts. Cornea. 2008;27:590–594. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318169d698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makdoumi K, Mortensen J, Sorkhabi O, Malmvall B, Crafoord S. UVA-riboflavin photochemical therapy of bacterial keratitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;250:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vazirani J, Vaddavalli P. Cross-linking for microbial keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:441–444. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price M, Tenkman L, Schrier A, Fairchild K, Trokel S, Price FJ. Photoactivated riboflavin treatment of infectious keratitis using collagen cross-linking technology. J Refract Surg. 2012;28:706–713. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20120921-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrari G, Iuliano L, Vigand M, Rama P. Impending corneal perforation after collagen cross-linking for herpetic keratitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:638–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martins S, Combs J, Noghera G, et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of riboflavin/UVA combination (365 nm) in vitro for bacterial and fungal isolates: a potential new treatment for infectious keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3402–3408. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao X, Zhao X, Li W, Zhou X, Liu Y. Experimental study on the treatment of rabbit corneal melting after alkali burn with collagen cross-linking. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012;5:147–150. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robert M-C, Biernacki K, Harissi-Dagher M. Boston keratoprosthesis type 1 surgery: use of frozen versus fresh corneal donor carriers. Cornea. 2012 May;31:339–345. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823e6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]