Abstract

Given growing concerns of im/migrant women’s access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, we aimed to (1) describe inequities and determinants of their engagement with SRH services in Canada; and (2) understand their lived experiences of barriers and facilitators to healthcare. Using a comprehensive review methodology, we searched the quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed literature of im/migrant women’s access to SRH care in Canada from 2008 to 2018. Of 782 studies, 38 met inclusion criteria. Ontario (n = 18), British Columbia (n = 6), and Alberta (n = 6) were primary settings represented. Studies focused primarily on maternity care (n = 20) and sexual health screenings (n = 12). Determinants included health system navigation and service information; experiences with health personnel; culturally safe and language-specific care; social isolation and support; immigration-specific factors; discrimination and racialization; and gender and power relations. There is a need for research that compares experiences across diverse groups of racialized im/migrants and a broader range of SRH services to inform responsive, equity-focused programs and policies.

Keywords: Sexual health, Reproductive health, Immigrant health, Health service access, Health inequities

Introduction

Global migration is escalating, especially among women fleeing humanitarian crises and sexual violence [1–4]. Refugee claims are increasing [5–7], and approximately half of migrants globally are women [8]. Im/migrant women face barriers to health, including insufficient health insurance coverage, discriminatory policies, and inadequate support—yet the structural determinants of im/migrant women’s healthcare access remain poorly understood [9–11], with previous research relying on acculturation, the ‘healthy immigrant effect’, and individual and behavioural explanations for differences among im/migrants [43, 44]. In this study, the term “im/migrant women” includes the diversity of international migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, temporary workers, long-term and recent arrivals, and individuals with and without legal immigration status [12] who self-identify as women (trans-inclusive).

Canada is a key destination for im/migrants globally, who represented 20.6% of its population in 2011, the highest proportion of G8 countries [13]. Im/migrants are projected to represent nearly half of Canada’s population by 2036 [14], continuing to primarily reside in Ontario (32.9%) and British Columbia (BC) (32.3%) [14, 15]. About 20% of women in Canada are im/migrants, most of whom are of reproductive age(15–49 years) and racialized [16, 17], with a projected rise to 27% by 2031 [18]. Women have migrated for reasons including better economic and working conditions, and refuge from hostile and xenophobic policy environments [6, 19]. Despite Canada’s growing im/migrant women population, relatively little is known about their access to and engagement in sexual and reproductive health(SRH) care [20].

Im/migrant women in Canada may face unique migration-related disparities in maternal health care [20–23], pregnancy care [24, 25], mental health support [26–30], contraception [31, 32], sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV testing [33–36], and cervical cancer screening [37–39]; however, diverse migration and SRH experiences, along with varying migrant categorizations, definitions and conceptualizations, make it difficult to compare and draw conclusions to inform policy and practice. Prior reviews of im/migrant health in Canada have infrequently considered gendered inequities in health access [40, 41] such as unequal power dynamics and intimate partner violence. Previous quantitative research has shown differences in perinatal health outcomes across ethnic groups and countries of origin, demonstrating diverse impacts of migration on health [42]. However, there is a need for research to also consider qualitative understandings of women’s lived experiences and the impacts of a wider range of migration experiences (e.g., migration duration, language, immigration status, xenophobia) and types of SRH care.

This analysis was informed by a structural determinants of health approach [46], considering the impacts of macro-structural factors (e.g., policies), im/migration-specific factors (e.g., immigration status, migration duration), health service use and delivery (e.g., system navigation), and individual-level factors (e.g., age, gender) [47] shaping SRH access. This was complemented by intersectionality theory to attend to the cumulative effect of various intersecting forms of marginalization and axes of oppression in influencing health access, such as racism, xenophobia, and ‘othering’ [43–45]. Finally, we drew from frameworks of the multi-staged nature of migrant health [3, 44] to highlight the influence of diverse and complex migration experiences, exposures, and engagement in care in destination, transit, and origin locations. Given gaps in existing research and evidence of SRH inequities among im/migrant women in Canada and globally, this review drew upon 10 years of peer-reviewed literature to (1) describe inequities and determinants of engagement in SRH services among im/migrant women in Canada, and (2) understand their lived experiences of barriers and facilitators.

Methods

Search Strategy

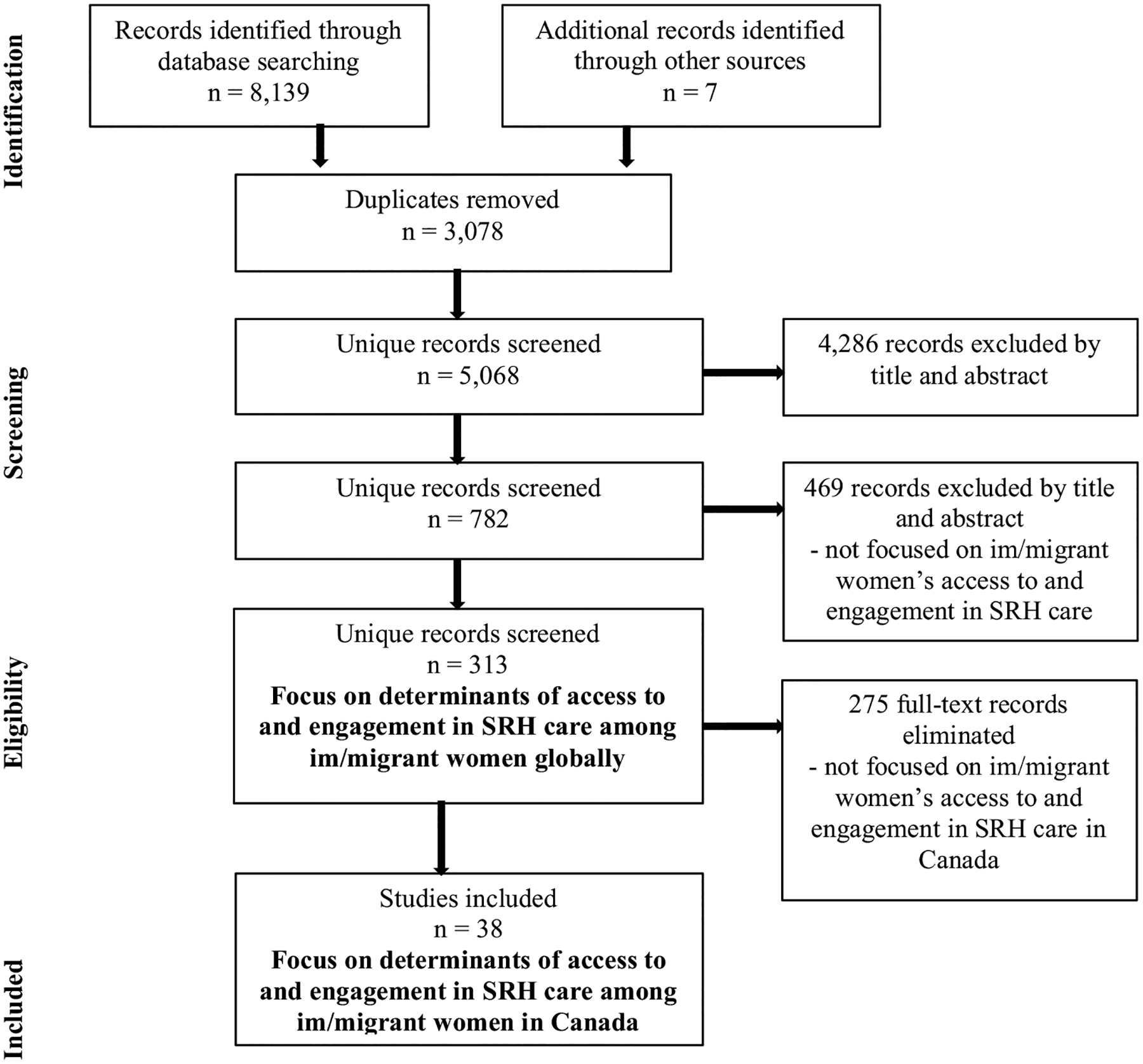

Our search began by exploring SRH inequities faced by im/migrant women globally. As this yielded a large number of records (n = 313), we narrowed our scope to the Canadian context at the final stage of screening using a comprehensive review methodology (see PRISMA diagram [48], Fig. 1). We searched the peer-reviewed literature for qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies describing the determinants and lived experiences of SRH inequities amongst im/migrant women. The review methodology was designed by SM and SG, in consultation with MW; a UBC librarian with specialized skills in systematic reviews also supported development of the search strategy. We searched four databases (Ovid Medline, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Sciences Citation Index, and CINAHL) using combinations of terms related to SRH, migration, women and research methodologies (Appendix A), subsequently cross-referencing articles and hand-searching to ensure no key studies were missed. These databases were selected based on the scope and topics covered by the comprehensive review. For example, Ovid Medline was selected as an appropriate tool for conducting comprehensive reviews of medical literature, CINAHL for including studies on SRH, migration and women, and SSCI for ensuring coverage of social sciences literature. A limiter was used to identify articles published between 2008 and 2018. Guided by the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1), we: (1) reviewed titles and abstracts to ensure their relevance to our initial objectives that were globally-focused; (2) reviewed abstracts and narrowed focus to studies describing determinants and lived experiences of SRH access amongst im/migrant women; (3) reviewed full texts to include only Canadian studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram of screening process for studies on determinants of access to and engagement in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services among im/migrant women in Canada (2008–2018) based on searches in Ovid Medline, Social Sciences Citation Index, Sciences Citation Index, and CINAHL

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible studies at the final stage of screening included primary, peer-reviewed studies that met the following criteria: (i) in English, (ii) published from January 2008 to July 2018, and (iii) focused on im/migrant women’s access to SRH care in Canada. We focused on studies in the last 10 years to ensure relevance to the current im/migration context and provide recent, updated evidence of factors shaping im/migrant women’s SRH access in Canada. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included to capture patterns of SRH service access, such as how often and frequently SRH services were used, as well as determinants of women’s access to and engagement in SRH care. The study population included all im/migrants who self-identify as women (trans-inclusive) of reproductive age, defined by the World Health Organization as 15–49 years. Studies on internal migration and men im/migrants were excluded. Secondary research, grey literature, and studies with no explicit focus on SRH and im/migrant women were also excluded.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Retrieved studies were managed in standard reference management software. We tabulated study characteristics (Table 1) and the following data when available: barrier or facilitator, type of SRH care needed or accessed, qualitative narratives, and epidemiological associations (Appendix B). Tabulated groupings were decided based on similar approaches reported in the literature [49, 50]. We synthesized findings by grouping studies until a comprehensive understanding of key themes (Appendix B) that emerged from both qualitative and quantitative studies was generated. For qualitative studies, we extracted narrative exemplars based on key barriers and facilitators that determined whether and how women accessed SRH care. For quantitative studies, we extracted epidemiological data of relevance to our objectives, such as proportions that described how often and frequently SRH services were accessed, as well as statistical associations (e.g., odds ratios). Finally, we grouped both qualitative and quantitative findings according to determinants of SRH access and engagement amongst im/migrant women in Canada. We interpreted findings considering the various contributions of macro-structural factors, immigration-specific factors, health service use and delivery, and individual-level factors.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies (N = 38) on determinants of access to and engagement in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services amongst im/migrant women in Canada (2008–2018)

| Type of SRH care | Canadian Province | Study design | Immigration variables | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad et al. [56] | Ontario | Qualitative | South Asian born in India (68%), Pakistan (27%), and Bangladesh (5%) Mean years lived in Canada: 14.3 |

Social stigma, rigid gender roles, marriage obligations, expected silence, loss of social support, limited knowledge about available resources, myths about partner abuse, and children’s wellbeing delayed help-seeking for GBV. Aspects of HCPs including trust, judgmental, gender, regular inquiries about abuse, and availability of supportive services determined access |

| Alaggia et al. [79] | Ontario | Qualitative | Immigrants and refugees from Punjab, Bengal, South Asia and South America | Barriers to disclosure/reporting GBV: Cultural practices; reluctance of police intervention; isolation; staying for the children; economic barriers; fear of immigration status repercussions Immigration laws and policies contained systemic and structural barriers (e.g., unrealistic criteria required for immigration applications in cases of sponsorship due to IPV) |

| Amankwah et al. [37] | Canada | Quantitative | Chinese, South Asian, Filipino, Other Asian, Black, and Latin American, most of whom lived in Canada for > 10 years | Visible minority women were > 2 × as likely to not get a Pap test. Recent arrivals who did not have a regular doctor were at highest risk for not having a Pap test. Risk AOR for women never having a Pap test: Those living in Canada for < 10 years (AOR 2.2) compared to those living in Canada for > 10 years (AOR 1.1). Not having a regular doctor (AOR 2.8) |

| Chang et al. [52] | British Columbia | Qualitative | Chinese (93.3%) and Taiwanese (7.7%) who migrated in the last 5 years. Lived in Canada for 4–6 years (53.8%) and 1–3 years (46.2%) | Barriers to traditional postpartum practices included a lack of social support, and formal institutional structures. Help from Chinese family members, friends and informed healthcare providers were facilitators. Issues included unregulated/unreliable paid helpers, uninformed/insensitive providers, financial constraints, and structural limitations |

| Donnelly [66] | Canada | Qualitative | Vietnamese Canadian | Challenges included HCPs’ lack of cultural awareness about the private body, patients’ low socioeconomic status, the HCP-patient relationship, and limited institutional support |

| Ganann et al. [65] | Ontario | Quantitative | Immigrants: English and French Canadian, Chinese, South Asian, Jewish, Italian, Portuguese, Other | Immigrant women were significantly more likely to experience fair/poor postpartum health status, higher risk for postpartum depression, and rate community health services as fair/poor (12.2% vs. 3.6%), and were less likely to be able to access care for emotional health problems (5.1% vs. 1.0%) |

| Grewal et al. [53] | British Columbia | Qualitative | Immigrants from Punjab who lived in Canada for 2 years on average | Traditional health beliefs and practices related to the perinatal period included diet, lifestyle, and rituals. The role of family members was important in supporting women during perinatal experiences. Both positive and negative interactions were had with HCPs in the Canadian health system |

| Guruge and Humphreys [70] | Ontario | Qualitative | Sri Lankan Tamil immigrants | Negative GBV support experiences were shaped by services that were unfamiliar, inappropriate, not culturally and linguistically appropriate, uncoordinated, not confidential, and had discriminatory and racist practices |

| Higginbottom et al. [76] | Alberta | Qualitative | Sudanese immigrants who migrated from Sudan, Egypt, and Lebanon in the last 5 years | Pregnancy and delivery were believed to be natural events related to personal agency, without a need for special attention or health interventions. Sub-Saharan culture supported ideology of patriarchy. Pregnancy and birth reflected empowerment for women, which may not have been respected by husbands |

| Higginbottom et al. [80] | Alberta | Qualitative | Immigrant women who spoke Arabic, Urdu, Tagalog, French, Swahili, Hassaniya or Tigriniya | Verbal communication; unshared meaning; non-verbal communication to build relationships based on trust; trauma, culture and open communication determined maternity care experiences, and were impacted by pre-migration histories, cultural factors, accessible healthcare and health outcomes |

| Higginbottom et al. [61] | Alberta | Qualitative | Sudanese (n = 12), Filipino (n = 8), Chinese (n = 6), Colombian (n = 2), n = 1 Tajikistan, India, Mauritania, Pakistan, Eritrea | Accessibility of maternity services was determined by communication barriers, lack of social support, cultural beliefs, lack of information, inadequate health care, and cost of medicines. Determinants of client satisfaction included cultural shock, stereotypes, discrimination, immediate discharge, short consultation time, lack of confidentiality, and lack of consent |

| Hulme et al. [58] | Ontario | Qualitative | Mandarin and Bengali-speaking women | Varied perceptions of risk and preventative health for breast and cervical cancer. Barriers to health system engagement and screening were related to ‘navigating newness’, including transportation, language, time off work, and childcare; fear of screening and cancer; painful or traumatic experiences; access to female providers. Women were generally willing to be screened |

| Jarvis et al. [64] | Quebec | Quantitative | 96% of uninsured women had precarious status; 4% were Canadian citizens; 57.7% were undocumented; 9.9% were visitors or students; 28% were asylum seekers | Uninsured women had fewer prenatal visits than insured women (6.6 vs. 10.7, p = 0.05). Uninsured women presented later in pregnancy and had fewer routine prenatal screening tests. Most uninsured women had inadequate prenatal care utilization (61.9% vs. 11.7%, p < 0.001). There were significant differences in adequacy of services between insured and uninsured women |

| Khadilkar and Chen [82] | Ontario | Quantitative | Recent immigrants (< 10 years) and non-recent immigrants (> 10 years) | Recent immigrant women were less likely to have had a Pap test in the past 3 years than those who were Canadian-born (PR 0.77; 95% CI 0.71, 0.84). Both groups showed similar results for recommended Pap testing intervals. Higher income and level of education, younger age, and being married were independently associated with better Pap testing rates |

| Kingston et al. [51] | Canada | Quantitative | Recent immigrant women (< 5 years) (7.5%), non-recent (> 5 years) (16.3%) and Canadian-born women (76.2%) | Immigrant women were more likely to report high levels of postpartum depression symptoms (13.2% vs. 6.0%), and less likely to have access to social support (74.1% vs. 90% during pregnancy, 67.8% vs. 87.1% during postpartum), and to rate their own/infant’s health as optimal Duration of residence in Canada was a key determinant |

| Lee et al. [54] | Ontario | Qualitative | Women (n = 10) from Hong Kong (n = 3) and Taiwan (n = 2) | Preference for linguistically and culturally competent HCPs, with obstetricians over midwives. Women built strategies to deal with inconveniences of Canada’s healthcare system, and have multiple resources of pregnancy information. Some merits of the Canadian healthcare system, but a need for culturally sensitive care and understandings of Chinese women’s experiences |

| Lofters et al. [73] | Ontario | Quantitative | Global immigrant women who were family sponsored, refugees, economic migrants, and other | Being born in a Muslim-majority country was significantly associated with lower likelihood of being up-to-date on Pap testing after adjustment for region of origin, neighborhood income, and primary care-related factors [ARR 0.93; 95% CI 0.92–0.93]. ARRs were lowest for women with no access to primary care (ARR 0.28; 95% CI 0.27–0.29) |

| Lofters et al. [39] | Ontario | Quantitative | Women were economic migrants (44.3%), family sponsored (40.9%) and refugees (14.2%). 15.1% lived in Canada for < 10 years | Appropriate cervical cancer screening occurred for 61.1% of women. Living in low-income areas was associated with lower rates of cervical cancer screening (ARR 0.88, 95% CI.0.88–0.88) Recent arrival was associated with lower rates (ARR 0.81, 95% CI 0.8–0.81). Cervical cancer screening rate was 53.1% over a 3-year period for immigrant women living in urban areas, lower than expected |

| Logie et al. [57] | Ontario | Quantitative | ACB women living with HIV. Citizens (36%), immigrants (34.8%), asylum seekers (16.8%), refugees (8.1%), undocumented (3.1%) and visa holders (1.2%) | Age was not significantly associated with variables, while income was associated with significantly higher overall quality of life scores, social environments and relationships. Determinants included engagement in and continuity of HIV care, including access, needs-based care, communication with health professionals, and appointment time-keeping |

| Merry et al. [62] | Ontario and Quebec | Qualitative | Asylum seekers from Nigeria, Mexico, India, Colombia, and St. Vincent who lived in Canada for < 2 years | Determinants to postpartum care included isolation; difficulties reaching mothers postpartum; language barriers; low health literacy; lack of psychosocial assessments, support and referrals; and IFHP being limited and confusing |

| Merry et al. [81] | Quebec | Quantitative | Women in Canada for < 5 years. Economic and temporary residents, family sponsored, refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented | Predictors of unplanned caesareans included being from sub-Saharan Africa/Caribbean (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.02–5.51) and admission for delivery in early labour (OR 5.43, 95% CI 3.17–9.29). Among women living in Canada for < 2 years (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.98–3.20), predictors were also being a refugee, asylum seeker, or undocumented (OR 4.24, 95% CI 1.16–15.46) |

| Mumtaz et al. [23] | Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba | Quantitative | Newcomer women (n = 140) included landed immigrants, refugees, students, visitors and temporary workers | Few received information on emotional and physical changes during pregnancy (87% vs. 95%)—more from books (27% vs. 17%) and nurses (20% vs. 13%), and less from family doctors (10% vs. 15%) and friends (10% vs. 20%). Rates of C-sections were higher for newcomers (36.1% vs. 24.7%), who were also less likely to report “very satisfied” with care |

| Ng and Newbold [75] | Ontario | Qualitative | No participant socio-demographic information | Determinants of prenatal care included language; cultural sensitivity and type of care; complexity of delivering care; cultural awareness; provider type; and level of professionalism |

| Newbold and Willinsky [71] | Ontario | Qualitative | No participant socio-demographic information | Barriers to family planning and reproductive health care included language; role of gender in decision-making; misconceptions or a lack of knowledge about family planning; and cultural sensitivity. There were complexities in experiences with professional and non-professional interpreters, and HCP misunderstandings about other cultures |

| Ochoa and Sampalis [69] | Quebec | Qualitative | Permanent residents (n = 11), asylum seekers (n = 10), citizens (n = 1), denied refugee status (n = 2), tourists (n = 1). Lived in Canada for 2–3 years (32%), 6–12 months (24%), 4–5 years (24%) | HIV/STI care experiences characterised by uncertainty, deception and fraud, and included family separation and discrimination. Risk was related to unequal gendered power Vulnerability was determined by experiences across the life course; migratory status; sexual and occupational abuse; language barriers; a lack of social support; and ability to access health services |

| O’Mahony and Donnelly [26] | Canada | Qualitative | Non-European immigrant and refugee women living in Canada for < 10 years | Immigration policy and gender roles were key barriers to postpartum care. Structural barriers, including precarious status and emotional and economic dependence sometimes left women vulnerable and disadvantaged in protecting themselves against postpartum depression |

| O’Mahony et al. [28] | Canada | Qualitative | Women from Central and South America, China, Middle East, and South Asia, and lived in Canada for < 2 years (n = 14), 2–5 years (n = 9), and 6–10 years (n = 7) | Determinants of postpartum depression and seeking for support and treatment included cultural influences (e.g., meaning of postpartum depression, community beliefs), socioeconomic influences (e.g., seeking employment, workplace discrimination), and spiritual and religious beliefs. Social stigma determined decision-making about health practices and coping |

| Pelaez et al. [74] | Quebec | Qualitative | HCPs serving newly arrived im/migrant women No socio-demographic information on im/migrant women | Barriers to maternity care were related to HCP expectations and communication and access to appropriate care. This was influenced by background and social positions and how HCPs balanced women’s needs with the perceived requirement to adhere to standard procedures and regulations |

| Redwood-Campbell et al. [68] | Ontario | Qualitative | Newly immigrated (living in Canada for < 5 years) women and Canadian-born women who spent 0.5–16 years in Canada | Determinants of cervical cancer screening: Knowledge gaps and needs; attitudes towards screening; role of HCPs and health system; culture. Women indicated a strong need for information on screening, and had positive feelings about being proactive. Some differences regarding preferences for female clinicians, which was a higher priority than language |

| Reitmanova and Gustafson [78] | Newfoundland and Labrador | Qualitative | Immigrant Muslim women. Some were Canadian citizens | Women experienced discrimination, insensitivity and a lack of knowledge about religious and cultural practices by providers in accessing pregnancy care, labour and delivery, and postpartum care. Barriers to emotional support and culturally and linguistically appropriate information were further complicated by adjustments associated with immigration |

| Sou et al. [59] | British Columbia | Quantitative | Migrant sex workers from China (76.9%), U.S. (3.8%), and Philippines (2.2%). 41.8% moved to Canada in the last 5 years | Structural determinants of inconsistent condom use included servicing in formal indoor venues (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.07–0.41), sex work as primary source of income (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.09–0.76) and difficulty accessing condoms in the workplace (OR 4.75, 95% CI 1.49–15.15). These were independently correlated with increased odds of inconsistent condom use |

| Sou et al. [60] | British Columbia | Quantitative | 10.5% of women were recent im/migrants (< 5 years) and 13.8% were long-term im/migrants (> 5 years) at baseline | In the final model, recent immigration (AOR 3.23, 95% CI 1.93–5.40), long-term immigration (AOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.22–2.96), police harassment including arrest (AOR 1.57; 95% CI 1.15–2.13), and lifetime abuse/trauma (AOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.05–1.99) remained significantly and independently associated with elevated odds of unmet health needs in the last 6 months |

| Vahabi and Lofters [67] | Ontario | Qualitative | Muslim landed immigrants and Canadian citizens from Iran, Pakistan and India. Lived in Canada for > 10 years (n = 18, 60%), 5–9 years (n = 5, 17%), 0–4 years (n = 7, 23%) | Barriers to cervical cancer screening included beliefs and health practices of home countries; limited knowledge about guidelines; a lack of culturally appropriate health information and knowledge about the Canadian health system; access to female physicians; language and ethnic mismatch; long wait times; access to transportation, and time constraints |

| Vanthuyne et al. [77] | Quebec | Quantitative | HCPs and service providers serving immigrant populations No socio-demographic information of im/migrant women |

Some HCPs perceived uninsured migrants as “deserving” of universal access to healthcare, while most viewed those uninsured as “undeserving” of free care. For most, the right to healthcare for immigrants with precarious status was perceived as a “privilege” |

| Vigod et al. [29] | Ontario | Quantitative | Immigrant women (13% refugees, over 50% from Asia). 40% migrated in the last 5 years, 30% 5–10 years ago, and 32% over 10 years ago | Compared to long-term residents, im/migrant women were less likely to use postpartum mental health services (14.1% vs 21.4%, OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.59–0.61). Hospitalization risk was similar and did not change much after adjusting for variables/covariates. 19.4% used mental health services within 1 year postpartum |

| Wiebe [72] | British Columbia | Quantitative | Women born in 75 different countries—38.1% born in Asia and 46.6% born in Canada | Immigrant women presenting for abortion were less likely to be using hormonal contraception when they got pregnant (12.5% vs 23.5%, P < .0.001), had more negative attitudes towards it (62.6% vs 51.6%, P < 0.003), and reported more barriers (24.8% vs 15.3%, P < 0.001). Those who spent more time in Canada were more likely to have similar responses to Canadian-born women |

| Wilson-Mitchell and Rummens [63] | Ontario | Quantitative | South Asian mothers who were asylum seekers, Canadian born and landed immigrants, temporary workers, and visitors | Most uninsured women received less than adequate prenatal care. Over 50% received inadequate prenatal care and 6.5% received none. Uninsured mothers experienced more C-sections due to abnormal fetal heart rates. The number of prenatal visits reported for the uninsured group (mean = 6.04, t = − 6.173, α = 0) was significantly lower than for the insured (mean = 8.70) |

| Winn et al. [55] | Alberta | Qualitative | HCPs providing care for refugee women No socio-demographic information of im/migrant women | Key barriers to maternity care included language, navigating the health system, and culture. Strategies to manage barriers included team-based approaches to care, service coordination, paying out of pocket, and donations to provide care for uninsured. Federal funding cuts left many without coverage, and further strained limited resources |

Results

Our search yielded 782 studies describing SRH inequities faced by im/migrant women globally to determine eligibility, of which we excluded 469 after reviewing abstracts. We hand-reviewed full-texts of 313 potentially eligible studies that focused on access to and engagement in SRH care for im/migrant women globally (Fig. 1). Of 38 Canadian studies that met inclusion criteria, most were conducted in Ontario (n = 18), followed by BC (n = 6), Alberta (n = 6), Quebec (n = 5), Saskatchewan (n = 1), Manitoba (n = 1), and Newfoundland and Labrador (n = 1). Most studies did not differentiate between im/migration categories, and characterized participants as “immigrant women”, “newcomers”, or by ethnicity and/or religion (n = 28). Where immigration status was specified, most studies focused on sponsored refugees and asylum seekers (n = 17); others included temporary workers and students (n = 7), permanent residents (n = 5), visitors (n = 5), family sponsored (n = 3), and undocumented women (n = 3). Only two studies recruited participants below the age of 20 [37, 51].

Of 38 studies, 23 were qualitative and 15 were quantitative (Table 1). No mixed-methods studies met our inclusion criteria. Most studies focused on maternity care (n = 20), followed by sexual health screenings (cervical cancer, HIV/STI) (n = 12), contraception (n = 3), and gender-based violence (GBV) support (n = 3) (Appendix B). While all studies discussed barriers faced by im/migrant women, only seven identified facilitators [52–58].

Our findings are organized by eight determinants of SRH access and engagement, which we identified by grouping and categorizing key barriers and facilitators highlighted in each study (Appendix C): (i) health system navigation and access to SRH service information; (ii) positive and negative experiences with health personnel; (iii) availability of culturally safe care; (iv) language barriers and availability of language-specific care; (v) social isolation and support; (vi)immigration-specific factors; (vii) stigma, discrimination and racialization; and, (viii) gender inequities and power relations. We synthesized quantitative data (e.g., descriptive statistics, odd ratios) to understand determinants of SRH care access, and synthesized narratives and themes reported in qualitative studies to understand inequities and lived experiences of barriers and facilitators to SRH services faced by im/migrant women. Although eligibility included all im/migrants who self-identified as women, few studies specified gender identities [59, 60].

Determinants of SRH Access and Engagement

Our analysis found that existing literature on im/migrant women’s access to and engagement in SRH care in Canada has primarily focused on health service use and delivery, and less on macro-structural and immigration-specific factors.

Health System Navigation and Access to SRH Service Information

Nineteen studies described links between health system navigation challenges and limited access to maternity care [23, 54, 55, 61–65], sexual health screenings (cervical cancer [37, 39, 58, 66–68], HIV/STIs [69]), GBV support [56, 70], and contraception [71, 72].

Qualitative and quantitative studies described the Canadian health system as inconvenient and inadequate due to institutional health system barriers, including challenges finding a family doctor, long wait times, quick hospital discharges, limited and confusing health insurance coverage, and high costs [37, 55, 58, 61, 64, 66, 74]. In a Quebec study, a permanent resident accessing HIV/STI testing during pregnancy explained, “We signed up for a family doctor[…] four years ago, and they still have not called me[…] I had already had two miscarriages and I had a baby with a high-risk pregnancy and I am still waiting”(p. 421) [69]. While few studies described greater access to women providers in Canada compared to home countries [54], accessing women doctors was reported as a key barrier [37, 38, 55, 58, 65–68, 74, 75] for providers, as well as im/migrant women who expressed discomfort with men physicians [55, 58, 66, 75]. Government-funded provincial health insurance influenced access to sexual health screenings and maternity care in several studies [39, 55, 62–64]. In Ontario, for example, rates of cervical cancer screening were low among low-income im/migrant women with health insurance for the last 10 years (31.0%) compared to high-income women who lived in Ontario longer (70.5%) [39].

Health system differences between countries of origin and Canada, as well as limited availability of SRH service information, were common concerns and often limited uptake [56, 61, 63, 76]. Some women feared hospital-based deliveries in Canada, believing caesarean sections were the preferred method of delivery [73], and others’ unfamiliarity with Canadian guidelines for cervical cancer screening determined whether they accessed this service. However, women expressed the desire to learn and made recommendations to raise awareness of available services and health information, such as electronic annual reminders for routine cervical cancer screening, information sessions on available services and referral requirements, and resource booklets [68].

Positive and Negative Experiences with Health Personnel

Sixteen qualitative and quantitative studies identified negative experiences with HCPs for racialized im/migrants– notably judgmental attitudes, insensitive care, and violations of privacy and consent—as barriers to maternity care [52, 53, 55, 61, 62, 73, 75–78], cervical cancer screening [58, 66], HIV/STI [60] testing, GBV support [56, 70], and family planning [71].

Violations of privacy and consent were reported across qualitative studies [61, 66, 69, 70] and negatively impacted healthcare experiences. A woman in Newfoundland & Labrador explained, “I asked nurses if they can knock before they enter so I can get dressed. I also put a sign on the door but they didn’t respect it. This man came and saw me. I was very upset and crying” (p. 106) [78]. In a situation where consent had not been appropriately obtained due to inadequate translation support and rushed interactions, patients who were unclear of the conditions of consent still underwent a procedure [61]. An HCP in Alberta noted, “You’re trying to offer them an operation for what you feel are correct reason[s], so whether they understand English or don’t […] their consent is perhaps not optimal in a stressful situation.” (p. 9) [61].

Unequal power dynamics between providers and patients were also shown to strongly influence im/migrant women’s SRH experiences, and sometimes prevented women from asking for critical health information [66]. Encouragingly, in Ontario and BC, experiences with HCPs were often perceived as culturally safe, supporting im/migrant women’s engagement in maternity care [52, 53, 55], GBV support [56], and sexual health screenings (cervical cancer [58], HIV [57]). In a quantitative study with African, Caribbean and Black im/migrant women living with HIV, tailored, needs-based care and clear communication were positively associated with enhanced quality of life and increased engagement in and continuity of care [57].

Where available, providers with specialized training and experience in refugee health described active, im/migrant-sensitive referrals and collaboration with settlement organizations as critical for facilitating patient engagement with SRH services. In Alberta, HCPs described tailored knowledge of refugee needs and culturally safe models of maternity care, highlighting the ways in which they endeavoured to address complex structural factors influencing im/migrant women’s health access (e.g., transportation, knowledge of available services, language issues [55]). Other HCPs reflected on their unfamiliarity with im/migrant health and expressed a desire for increased training in culturally safe and im/migrant-specific care [55].

Availability of Culturally Safe Care

Eleven studies identified disparities in culturally safe services as barriers to maternity care [26, 28, 54, 63, 65, 73], contraception [71, 72], sexual health screenings (cervical cancer [67], HIV/STI [69]), and GBV support [70]. Socio-cultural differences in SRH norms between home countries and Canada, including gender expectations, sexuality, GBV, and mental health, had profound impacts on access to and engagement in SRH services [26, 66–68, 75]. Community stigma limited knowledge of available GBV support as related discussions were ‘taboo’ and avoided [56]. Anticipated stigma around mental illness in the context of pregnancy was also commonly described as a challenge related to accessing support [26, 74]. Some experienced negative interactions with physicians from the same culture due to fears of confidentiality violations or negative assumptions [66, 67], whereas seeing doctors of the same culture facilitated conversations around SRH for others [67]. A woman accessing cervical cancer screening in Ontario explained how her appearance led to preconceived assumptions: “I’m wearing hijab but maybe I am sexually active so they should not assume.” (p.8) [67].

Language Barriers and Availability of Language-Specific Care

Fourteen studies identified language barriers and disparities in language-specific services as barriers to maternity care(54,63,65), sexual health screenings (cervical cancer [37, 58, 66], HIV/STI [57, 69]), GBV support [70], and family planning [71].

Several studies described the availability of interpretation services as critical to address language barriers faced by different communities of im/migrant women, and highlighted challenges associated with different modalities (e.g., phone, in-person) [54, 55, 63, 69–71, 77, 78]. These included limited time and resources, potentially limited knowledge of medical terminology among interpreters, and concern of stigma or breaches in confidentiality by interpreters with shared cultural backgrounds or communities [63, 70, 71, 77, 78]. An HCP described time constraints: “When you’re in the delivery and there’s an acute situation, and you’ve got to do a vacuum or the obstetrics[…], sometimes there’s not time to go get the language line phone, and then be put on hold, having to have a back and forth conversation translated, back to do you understand what the risks are…” (p. 6) [55]. Although analyses of interpretation services in the context of HIV/STI care were limited, a Quebec study found that im/migrant women often brought members of their social network to appointments when translation services were unavailable; however, this sometimes led to confidentiality issues within smaller communities [69].

Conversely, some women felt that a wide range of SRH services expanded options for language-specific care and enhanced engagement. A Chinese woman in Ontario explained, “My OB didn’t provide me with much pregnancy related information. The nurse[…] can only speak English[…] I can get similar information from the community health centre.”(p. 5) [54]

Social Isolation and Support

Twelve studies identified social isolation as a barrier to maternity care [51, 52, 61, 62, 78], GBV support [56, 79], and sexual health screenings (HIV/STI [69]) attributed to disconnections from family, friends, and community due to migration [56]. Quantitative studies found that im/migrant women were less likely than their Canadian-born peers to have access to social support during pregnancy (74.1% vs. 90%) and postpartum (67.8% vs. 87.1%) [51]. Isolation among im/migrant women experiencing postpartum depression (PPD) also commonly limited health access [51, 52, 62, 78]. Qualitative studies found that social isolation enhanced im/migrant women’s vulnerability to GBV, and providers and advocates explained that immigration policies created significant challenges in reporting GBV for women who lacked social support. For example, in addition to written reports from police or medical services, immigration officials required women to be “settled” in Canada [79]. However, given challenges related to isolation and other factors, an immigration lawyer in Ontario explained, “They have to be these “super women”, so despite being abused, they have to have worked throughout the abuse,[…] established an extensive social network and community ties,[…] it’s a little unrealistic.”(p. 338) [79]. On a positive note, few studies found that support from family members, friends, providers and community organizations mitigated language barriers and fear through accompaniment for appointments and emotional support, enhancing access to healthcare for some [52, 53, 58].

Immigration-Specific Factors

Thirteen studies identified pre-migration experiences, immigration status, and migration duration as determinants of access to maternity care [26, 62–64, 74, 80, 81], sexual health screenings (cervical cancer [37, 73, 82], HIV/STIs [69]), contraception [72], and GBV support [79].

Few studies highlighted differences in SRH access based on immigration status [64, 69, 73], where permanent residents had greater access to services and asylum seekers and undocumented women faced additional barriers [69]. A quantitative study found that compared to insured women, uninsured undocumented women had fewer routine screening tests (93.7% vs. 100%, p = 0.045) and presented later in pregnancy (25.6 vs. 12.0 weeks, p < 0.001) [64]. Asylum seekers and refugees have access to government programmes in Canada, whereas undocumented individuals are somewhat ‘invisible’ in the eyes of the government and healthcare system. Additionally, while some services for asylum seekers are covered by Canada’s Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) there remain numerous disparities, including pre-approval required from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to access some mental health services, impeding access to needed care upon arrival [62]. Qualitative studies found that fear of negative consequences related to having precarious immigration status (i.e. status marked by the absence of rights and entitlements normally associated with permanent residence and citizenship), such as deportation and family separation, prevented women from accessing SRH support [80]. An undocumented woman experiencing PPD explained, “I don’t have insurance. It’s been nine months that I have given birth[…] I need a pap smear but I just don’t have support. I don’t have papers[…] I don’t have the money[…]” (p. 719) [26]. HCPs echoed similar concerns, including high costs of services for those without health insurance [74].

Migration duration also influenced im/migrant women’s access to SRH care [37, 60, 72, 82] where some studies demonstrated improvements in SRH access over integration in Canada [60, 82], while others showed additional barriers for recently arrived im/migrant women. A BC study found that the odds of unmet health needs were highest for recent im/migrants(AOR 3.23, 95% CI 1.93–5.40) [long-term im/migrants (AOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.22–2.96)] [60], while others found that that recent im/migrants (< 10 years in Canada) were at higher risk for never having a Pap test (AOR 2.2) than long-term im/migrants (AOR 1.1) [37], and less likely to have had a Pap test in the past three years (PR 0.77, 95% CI 0.71–0.84) [82] compared to Canadian-born women.

Stigma, Discrimination and Racialization

Eight studies described how experiences of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination based on gender and religion limited im/migrant women’s access to maternity care [26, 61, 78], GBV support [56, 70], and HIV/STI services [60, 69].

A Quebec study with HCPs providing care for uninsured pregnant im/migrant women (N = 237) found that most believed they were “undeserving” of healthcare due to xenophobic and discriminatory perceptions of im/migrants, and an unwillingness to provide care for those with precarious status [77]. Negative interactions with HCPs reported across studies were often due to racial or religious prejudice and resulted in inadequate care, incomplete assessments and culturally unsafe approaches [58, 62, 66, 74, 75, 78]. In a study of asylum seekers, a participant explained, “Here they say that there is no discrimination, well this is the easiest way to be discriminated against, because you have no status. In all situations, you need to take out your papers and they see that you are not a tourist, nor are resident, you are nothing.” (p. 419) [69].

GBV survivors reported that racialization, stigma and shame from community, family members [56] and HCPs [66, 70] often delayed access to support. Narratives of HCPs in some studies reflected discriminatory, or ‘othering’ attitudes towards im/migrants from particular immigration classes or regions of origin: “mostly refugees, I think they come to Canada and [expect] everything to be given to them[…] some of them are very demanding[…] They are all quite easy except for the [ethnic group name]” (p. 10) [68]. One study found that HCPs perceived discrimination to be an instinctive response, as opposed to a structural issue [66], while others were more sensitive to racism and xenophobia faced by im/migrant women, and used approaches that were culturally safe and patient-centered [61].

Gender Inequities and Unequal Power Relations

Five qualitative studies showed that gender inequities undermined access to maternity care [83], sexual health screenings (HIV/STI [60, 69]), GBV support [56], and family planning [71]. Across studies, gender norms related to women’s status and social positioning strongly shaped access to and engagement in SRH care. Studies demonstrated that unequal gendered power dynamics increased unsafe sexual behaviours and exploitation, increasing barriers to SRH support. A Latin American woman needing HIV/STI care explained, “He told me[…] what I want is to sleep with you whether you want it or not, I told him no, […] he got so angry with me that he fired me.” (p. 420) [69].

Unequal gender roles and power dynamics especially hindered access to GBV support, resulting in silence and hidden abuse [56]. One study reported that financial dependence on abusive partners who had control over their immigration status posed additional healthcare barriers [60]. An HCP demonstrated the extent to which women covertly sought birth control: “the women are saying ‘please don’t tell my husband’ or they have come here on the sly[…] they are like, ‘quick, give me a Depo Provera injection and don’t tell him’” (p. 376) [71].

Discussion

This review sheds light on alarming inequities in SRH care for im/migrant women in Canada. Key findings demonstrated that structural challenges associated with health system navigation and knowledge of SRH services, experiences of racism and xenophobia within and outside the health system, and insufficient culturally safe and language-specific services posed the most significant barriers to healthcare. We found that while positive experiences with health personnel and social support facilitated SRH access for some women, social isolation, precarious immigration status, and discrimination and stigma by community members and HCPs presented severe challenges for others. Our study echoes prior research calling for attention to the impacts of immigration-specific factors (e.g., duration of migration, changes across migration, immigration status) on health access [42, 44], and provides unique insights on research gaps and findings regarding SRH access for im/migrant women.

Past reviews of im/migrant women’s SRH access have focused on specific sub-populations (e.g., refugees, internally displaced migrants) [40, 49, 84, 85] and services (e.g., maternal health, HIV/STIs) [20, 40, 42, 50, 84, 86–88]; our findings build on this work by providing a comprehensive overview of inequities and determinants of access to a broader range of SRH services (e.g., sexual health screenings, GBV) amongst im/migrant women in Canada. Consistent with gaps identified in previous literature, heterogeneous definitions of immigrants across studies limited comparisons and understandings of diverse SRH access experiences [42]. Amongst studies that focused on specific populations, most included sponsored refugees and asylum seekers, and few made comparisons between the experiences of diverse groups. However, evidence demonstrated severe SRH inequities based on immigration status where available, highlighting the need for future research unpacking the impacts of immigration status on SRH experiences [69].

Most studies were conducted in Ontario, and limited information was found from other key destination provinces (i.e., BC, Alberta, Quebec). Most studies focused on maternity care and cervical cancer screening, with a dearth of research on contraception services, GBV support, or other types of sexual health screenings. This presents a need for greater understandings of inequities faced by im/migrant women across the full spectrum of SRH services. Some studies included both im/migrant women and provider perspectives, highlighting several multi-level opportunities to address challenges and strengthen supports. For example, women’s preference to see women doctors to avoid potential re-traumatization of sexual violence [80] speaks to a critical need for trauma-informed care in health and settlement settings. Insights provided by immigration lawyers, legal advocates and HCPs demonstrate the impacts of macro-structural factors and the need to include other stakeholders (e.g., settlement workers, government officials) in research to address structural challenges in SRH care.

Qualitative and quantitative findings complemented one another and provided unique insights regarding inequities and determinants of SRH access for im/migrant women. Quantitative findings highlighted statistical descriptions of im/migrant women’s use and access to SRH care, which was explained by various determinants of SRH access highlighted by qualitative findings. However, most studies were cross-sectional, and research using longitudinal methods to understand women’s SRH access over time, across arrival and settlement, is needed.

Although most literature continues to focus on health service use and delivery environments, several studies that did identify macro-structural and immigration-specific determinants of SRH care highlighted the critical influence of immigration status on limited health insurance coverage and other barriers to SRH care. Policies that exacerbate barriers for women experiencing pre-migration trauma or PPD, for example, demonstrate structural inequities that ignore intersecting forms of marginalization based on gender, race, age, and poverty. Most studies did not focus on the roles of macro-structural factors such as stigma, ‘othering’ [43], and immigration policies or the nuances of how these may influence whether and how im/migrant women engage with SRH services [43, 45].

Research gaps identified by our review include a limited focus on SRH access experiences of younger women, undocumented women, and women who speak languages other than English. Although reproductive age is understood to begin at the age of 15, only two studies included women below the age of 20 [37, 51]. While only three studies included undocumented women, one excluded this population [79] and others did not specify explicit inclusion or exclusion of certain subgroups. A large number of studies excluded women who could not communicate in English [56, 61, 67, 70, 77, 80], presenting significant inequities as available evidence demonstrated severe language barriers.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, our findings are the first to highlight the heterogeneous experiences of different im/migrant women sub-groups across a wide spectrum of SRH care. Our review also uniquely builds on past work by highlighting the nuances of how immigration-specific factors, including how variations based on the duration and type of migration, interact with cross-cutting factors such as gender and socioeconomic status [3, 44, 89], to shape im/migrant women’s SRH access in Canada. However, limitations exist. The studies included may not have captured the many, diverse experiences of im/migrant women’s access to SRH care in Canada. Articles that examined the health access of both im/migrant men and women and that did not have a clear focus on SRH were excluded, thus potentially missing some information on im/migrant women’s SRH access.

Recommendations for Future Research

The findings of this review call for additional research in im/migrant women’s health to highlight the nuanced ways in which structural and intersectional experiences shape SRH access, particularly in the context of maternity care and cervical cancer screening. Future research must engage a broader diversity of im/migrant populations, including youth, undocumented women, and asylum seekers, whose experiences remain underrepresented; this is critical to generate comparable data to inform im/migrant-sensitive health services and system planning. Narratives from stakeholders also demonstrate value in consulting service providers, policymakers and community advocates to understand varied perspectives on im/migrant women’s health access. Certain parts of Canada (e.g., Ontario) were better represented in the literature, and there remains a need for additional research particularly in BC, Alberta, and Quebec. Finally, longitudinal and mixed-methods designs are recommended to examine changes in health experiences and access over time and triangulate epidemiological findings with lived experiences.

Conclusions

The findings of this review highlighted important issues in SRH services faced by racialized im/migrant women in Canada across different types of SRH care, and pointed to key roles of macro-structural, immigration-specific factors, health service use and delivery, and individual-level factors in shaping inequities. Our analysis helps draws on both quantitative and lived experiences of im/migrant women, and points to the need for different types of interventions. Findings provide a comprehensive overview of challenges and supports faced by im/migrant women accessing SRH care in Canada; future research that compares and includes experiences of different im/migrant groups, addresses a wider spectrum of SRH services, and includes marginalized sub-groups is needed. This is essential to expand existing understandings of the diverse and shared needs and realities of im/migrant women to develop responsive, equity-oriented policies and interventions.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Vancouver Foundation, and Simon Fraser University (SFU). SG is partially supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award and the National Institutes of Health (NIDA). MW is partially supported by a Research Trainee award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. AES is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NICHD). SM is supported by a Doctoral Fellowship from SFU. We thank the Centre for Gender & Sexual Health Equity for research and administrative support, including Megan Bobetsis and Colette Ryan. We also thank Ursula Ellis, Reference Librarian at UBC’s Woodward Library, for her guidance.

Appendix A

See Table 2.

Table 2.

Combination of search terms used to explore and understand determinants of access to and engagement in sexual and reproductive health(SRH) services amongst im/migrant women in Canada (2008–2018) based on searches in Ovid Medline, Social Sciences Citation Index, Sciences Citation Index, and CINAHL

| Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) | “sexual health” OR “reproductive health” OR “SRH” OR “HIV” or “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “AIDS” or “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “STI*” OR “sexually transmitted infection*” OR “STD*” OR “sexually transmitted disease*” OR “contracept*” OR “miscarriage*” OR “abortion*” OR “stillb*” OR “live birth*” OR “antenatal” OR “prenatal” OR “postnatal” OR “perinatal” OR “postpartum” OR “pregnanc*” OR “maternal mortalit*” OR “maternal health” OR “maternal morbidit*” OR “sexual violence” OR “gender-based violence” OR “violence against women” OR “intimate partner violence” OR “IPV” OR “GBV” OR “reproductive coercion” |

| Migration | “migrant*” OR “migration” OR “immigrant*” OR “immigration” OR “refugee*” OR “asylum seeker*” OR “asylee*” OR “mobile population*” OR “displaced person*” OR “displacement” OR “IDP” OR “newcomer*” OR “deport*” OR “cross-border” OR “across borders” OR “binational” OR “transnational” OR “transmigration” OR “transmigra*” OR “traffick*” OR “undocumented” OR “foreign-born” OR “foreigner*” |

| Women | “women” OR “woman” OR “female*” OR “mother*” OR “maternal” OR “girl*” |

| Methodology | “qualitative” OR “interview*” OR “narrative*” OR “grounded theory” OR “focus group*” OR “ethnograph*” OR “quantitative” OR “epidemiolog*” OR “cross-sectional” OR “cohort” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT” OR “longitudinal” |

Appendix B

See Table 3.

Table 3.

Types of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services accessed by im/migrant women in Canada (2008–2018)

| Type of SRH care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternity care | Sexual health screenings and treatment | Gender-based violence support | Family planning and contraception |

| Prenatal and pregnancy [23, 51, 54, 55, 61, 75–77, 78, 80, 81] | Cervical cancer [37, 39, 58, 66–68, 73, 82] | GBV reporting and help-seeking (including intimate partner violence) [56, 70, 79] | Family planning [71, 72] |

| Postpartum [23, 26, 27, 29, 52, 62, 90] | HIV [57, 60, 69] | Condom use [59] | |

| Perinatal [53, 63] | STIs [60, 69] |

Appendix C

See Table 4.

Table 4.

Additional exemplars and findings of determinants of access to and engagement in sexual and reproductive health(SRH) services amongst im/migrant women in Canada (2008–2018)

| Theme | Population | Main finding | Qualitative exemplars of women’s lived experiences of barriers and facilitators to SRH care | Quantitative findings of barriers and facilitators to SRH care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health system navigation and access to SRH service information | Chinese newcomer women N = 13 |

Positive experiences navigating the Canadian health system facilitated access to maternity care [54] | “Here in Canada it is better because it’s one-to-one when your doctor examines you at prenatal visits. Back home there were often some other women waiting inside the examining room and overheard the conversation between you and your doctor.” (p. 5) | |

| HCPs N = 10 |

Inadequate health insurance coverage, costs and limited understanding of the health system created barriers to maternity care [55] | “P2: We heavily involved like, social work to figure it out [levels of coverage], like all of the front staff, and they had to be like on the ball. And then things kept on changing […] so it just made it very confusing […]” (p. 8) | ||

| “P2: Some did have their kids in the NICU and one even had their child die, and then and they ended up being presented with a massive bill, massive bill. So, it’s just you know, it’s tragic on a personal level, and then to have the added financial burden on top of it, it was cruel. And the babies are Canadian, if they’re born here, they’re born as Canadians.” (p. 9) | ||||

| “P6: So, we had a walk-in in clinic at the Travelodge and I was one of the [health care workers] mandated at the walk-in clinic […] and if they came to me and they were prenatal, I would definitely call the clinic that day and say we need an appointment for this pre- natal patient, can we fit her in? Literally fit her in. So, then we would require some rearranging of appointments, and scheduling and all that stuff…” (p. 9) | ||||

| Immigrant women from 9 different countries N = 33 Social service providers/stakeholders N = 18 HCPs N = 8 |

Inadequate care, high costs, and quick discharge led to poor satisfaction and quality of maternity care [61] | “It’s hard to find a family doctor because I phoned everyone … it took me for a while, and then you can’t go with him because his appointment [book] was full. I phoned a lot of clinics and then they cannot accommodate. (IW-Rural Town) It might take up to one year to find a family doctor. Moreover, after finally getting a family doctor and referral to a specialist clinic there was often another long waiting period because of the shortage of gynecologists or obstetricians. Some women complained that they received their first appointments in the advanced stages of their pregnancy. The issue of long wait periods was a great barrier to accessing care at an appropriate time.” (p. 8) | ||

| “She preferred to stay in the hospital a little bit longer, maybe one more day or anything. But [the] OB didn’t care and sent her home and then she actually fainted or lost consciousness at home and then her husband would have to call 911 and send her back to the hospital.” (IW-Urban Town) (p. 9–10) | ||||

| Latin American immigrant women N = 25 [permanent residents (N = 11), refugee status claimants (N = 10)] |

Shortage of doctors, delays, and a lack of referrals created barriers to accessing HIV/STI services [69] | “I had a high-risk pregnancy, they told me that I had to see a gynaecologist, and that there was a waiting list…. Many women tell me that they come to term in their pregnancy without ever seeing a gynaecologist. I was under a lot of stress because I was already four months pregnant and no one had seen me. I was bleeding eight days in my home, I would go to the health centre and they told me to go home, until the eighth day, I lost the baby.” (p. 422) | ||

| Chinese newcomer women N = 15 |

‘Inconvenient’ health system created barriers to maternity care [54] | “My OB wasn’t on duty and I had another OB that was ‘on call’ and he did not know anything about me and my pregnancy. It was difficult, especially, I had DM (diabetic mellitus) during pregnancy and my labour lasted sixteen hours.” (p. 4) | ||

| Muslim, West and South Asian immigrant women N = 30 |

Lack of knowledge of Canadian health system created challenges in accessing cervical cancer screening [67] | “For an immigrant there are lots of things that you don’t have enough information and you need someone to help you, and fortunately I have friends and family here and ask them to help me, and I chose my family doctor by their recommendation. But if they weren’t here, I think maybe I had a lot of problems, because we are not familiar with this system, it takes time to know how you can do many things”. (p. 7) | ||

| Immigrant women N = 4,55,864 |

Health insurance and characteristics of health providers were predictors of access to cervical cancer screening [39] | Appropriate cervical cancer screening occurred for 61.1% of women. Screening rates were low among women aged 25–49 and living in low-income areas (Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)) = .88 CI = .88–.88) | ||

| Cervical cancer screening was low amongst women registered with Ontario’s universal health insurance plan in the last 10 years (mainly recent immigrants) | ||||

| Refugee claimant women from five different countries N = 112 |

Difficulties reaching women, and limited and confusing health insurance coverage created barriers to postpartum care [62] | “I called several times. She was unavailable. It was difficult to locate her. A worker states she has left the shelter. ‘Jessica’, a person who lived at the shelter, knows the client and gave me her phone number.” (35 y.o., Nigeria, 7 mos in Canada) (p. 288) | ||

| “Paediatrician refused to see baby because she had no medicare. One month later the paediatrician gave her an appointment but when mother said she still had no medicare then he cancelled it.” (36 y.o., Mexico, 6 mos in Canada, Montreal) (p. 289) | ||||

| Uninsured and insured new immigrant and refugee claimant women N = 437 |

A lack of health insurance negatively influenced perinatal experiences for both mothers and infants [63] | Most uninsured pregnant women received less than adequate prenatal care. More than half received clearly inadequate prenatal care, and 6.5% received no prenatal care. Insurance status related to type of HCP, reason for caesarean section, neonatal resuscitation rates, and maternal length of hospital stay. Uninsured mothers experienced more caesarian sections due to abnormal fetal heart rates, and required more neonatal resuscitations | ||

| Chinese immigrant women N = 13 |

Multiple resources to obtain pregnancy information facilitated access to maternity care [54] | “My own mother couldn’t come due to a visa issue and my husband didn’t know how to cook, so we hired a Yue-Sao. She stayed three hours every morning for a month to cook Zuo Yue Zi meals for me. She was a nurse back home, so she is professional and knowledgeable. She is my consultant for postnatal practices.” (p. 6) | ||

| Immigrant women from 9 different countries N = 33 Social service providers/stakeholders N = 18 HCPs N = 8 |

Limited and inadequate health information negatively influenced access to maternity health services [61] | “The thing is, when people come here, because they have no idea about community resources, they don’t go. They don’t come” (HCP-Rural Town), (p. 7) | ||

| Newcomer women N = 140 Canadian-born women N = 1137 |

Low levels of pregnancy knowledge negatively influenced pregnancy outcomes and experiences [23] | No differences in newcomer ability to access prenatal care compared to Canadian-born women, but fewer received information regarding emotional and physical changes during pregnancy (87% vs. 95%, p < 0.001)—less from friends (10% vs. 20%), more from books (27% vs. 17%), more from nurses (20% vs. 13%), less from family doctors (10% vs. 15%). Rates of C-sections higher for newcomers (36.1% (95% CI 28.2, 44.8) vs. 24.7% (95% CI 22.2, 27.5), p = 0.02), and more likely to be placed in stirrups for birth and have an assisted birth | ||

| Less likely to report “very satisfied” with care received since birth (p = 0.03) | ||||

| Muslim, West and South Asian immigrant women N = 30 |

Limited knowledge about cervical cancer and screening guidelines limited access to screening [67] | “I have a question, what do you mean by screening? Is it a different program than when we go to family doctor and we do a check-up, we do blood testing?” (p. 5) | ||

| “So my family doctor has to ask me to do this? May be sometimes I’m not at risk so my doctor does not do it. Right?” (p. 5) | ||||

| Positive and negative experiences with health personnel | Chinese im/migrant women N = 13 |

Informed HCPs improved access to postpartum care [52] | “My midwife… felt that I was relatively weak due to having a Caesarean, so in the ten days after giving birth, she came to my home three times, that’s why I did not need to go out to see the pediatrician on my own”(P8 (p. 390) | |

| “The community nurses here visit about one hour each time. They would recommend a better place to breast- feed, which posture is better, and they would check if the baby is feeding correctly. She would help you like a postpartum doula. The second time they will call first to ask if you need anything. If there is a need she will come again”(P1)(p. 390) | ||||

| Im/migrant women N = 15 HCPs N = 5 |

Positive interactions with HCPs facilitated perinatal experiences [53] | “…the women describing the nurses as playing a positive and important role in making the childbirth experience less scary by monitoring the women’s labor, encouraging and coaching the women, providing massage, and offering explanations about the stages of labor.”(p. 296–297) | ||

| HCPs N = 10 |

HCPs that specialized in refugee health and practice diverse strategies of care improved maternity care experiences [55] | “P8: [community-based organization] is extremely well supported with other disciplines. So, we work closely with the social workers and they’re very instrumental in helping provide supports, just resources, physical resources, but also trying to get the social supports in place to.”(p. 7) | ||

| African, Caribbean and Black women living with HIV N = 173 |

Factors influencing engagement in and continuity of HIV care subsequently affected quality of life (QOL) [57] | Bivariate correlation results: Age not significantly associated with QOL for African, Caribbean and Black women living with HIV, but income associated with significantly higher overall QOL and social environments and relationships | ||

| Engagement in and continuity of HIV care was significantly associated with QOL (p = 0.003) | ||||

| Chinese im/migrant women N = 13 |

Barriers to implementing traditional postpartum practices due to unregulated, unreliable paid helpers and uninformed, insensitive providers [52] | “[The postpartum doula] has been paid in cash already, and she does not have a license or belong to a postpartum organization, so it is completely non-binding. And we cannot do ten “zuo yue zis” in a lifetime…To Chinese people “zuo yue zi” is done once or twice, at most three times, so postpartum doulas do not mind whether they have recurring customers…You have heard a lot of bad reports. After all, in this market the supply is less than the demand, that is, there are more mothers seeking postpartum doulas and there are less postpartum doulas” (P8) (p. 390–391) | ||

| “[The nurse said]...“Why do you not take a shower?” I felt I was being judged and thought of as “How come you’re so dirty?” Not only was her facial expression clear, her tone of voice was quite obvious to make me feel very uncomfortable” (P8) (p. 391) | ||||

| Health and academic personnel N = 237 |

Negative perceptions of im/migrants by HCPs contribute to stigma and discrimination in maternity care [77] | “Some healthcare workers perceive uninsured migrants as “deserving” of universal access to healthcare | ||

| Negative perceptions of migrants coupled with pragmatic considerations push most workers to view the uninsured as “undeserving” of free care | ||||

| For most participants, the right to healthcare of precarious status immigrants has become a “privilege”, that as taxpayers, they are increasingly less willing to contribute to.” | ||||

| Im/migrant women N = 15 HCPs N = 5 |

Negative interactions with HCPs limited women’s access to perinatal services [53] | “I had lots of pain and I was not in condition to stand up but they said, “No, you have to stand up.” I tried [but] when I stood, I had so much pain that I fell down. The nurses don’t really care what happens to the patients. The nurses told me that you should do your things yourself.” (p. 297) | ||

| Im/migrant women from nine different countries N = 33 Social service providers/stakeholders N = 18 HCPs N = 8 |

Short consultation times, a lack of confidentiality and informed consent, and insensitivity from HCPs limited access to maternity care [61] | “I also have another client who has been hospitalized many times and people will come to visit her, and some people are curious and they will go to the front desk and ask: What happened to her? Why is she sick? And the nurse out loud told them.” (HCP-FGI-Urban Town) (p. 9) | ||

| “Oh. Okay. Do you feel painful?” “No.” “Okay, you can go.” Like I don’t care. That’s the information but, I don’t care about you. Just the doctor in this way, just cold.” (IW-Urban Town) (p. 9) | ||||

| South Asian im/migrant women N = 22 |

Lack of supportive services for intimate partner violence (e.g. trust, non-judgmental) prevented access to care [56] | “Everyone here is telling you more or less that they spoke to the doctors, I think that doctors should be part of the circle that if they get a clue that a lady is going to be abused he should double-check, or confirm. The doctors should be part of the system to check for woman abuse” (FG1, p. 11) (p. 619) | ||

| HCPs N = 10 |

Expectations of provider type and level of professionalism negatively influenced access to prenatal care [75] | “First-generation immigrants often avoid midwifery care, because they see midwifery care where they come from is the lowest level of obstetric care…. They come here, and they have access to the big shiny hospital and the big shiny obstetrician and, in their country, that is a symbol of status and success and probably does reflect good healthcare. So, why would you go to a midwife? You wouldn’t do that. You would go to the big shiny place.” (p. 567) | ||

| “Well, you’re a nurse. How can you be looking after me? You are not a doctor. I need to see the doctor.” And, “I am getting second-rate care because I am seeing a nurse, just a nurse.” (p. 567) | ||||

| Im/migrant Muslim women N = 6 |

Insufficient care provided by HCPs negatively influenced access to maternity health services [78] | “Some women felt that they received inadequate support or inattentive care. One participant reported that when she needed assistance, she found a nurse “reading a fashion magazine and drinking Tim Horton’s [coffee].” (p. 105) | ||

| Refugee claimant women from 5 different countries N = 112 |

Inadequate assessments by nurses created challenges in postpartum care [62] | “She did not mention it [skipping meals] because the [nurse] had not asked.” (p. 288) | ||

| HCPs N = 10 |

Lack of coordination, and HCP’s unfamiliarity with refugee health and inability to address needs created barriers to maternity care [55] | “P7: Not a lot of [health care professionals] take the extra step to look at what’s going to happen when the baby’s born […] sometimes you need the physician who’s the first point of care often for the patients, to recognize their social concerns in terms of you know social detenninants of health […] so that you can refer her to the proper resources because she is so vulnerable, and it’s really common that these women don’t get any services.” (p. 8) | ||

| “P9: Sometimes our [refugee] patients even ask us in triage like financial concerns, and I don’t know what to say at all. Like that’s something I would like to be more educated on, like what kind of services are available to you [refugees].” (p. 10) | ||||

| Language barriers, and availability of culturally safe and language-specific care | Family planning HCPs N = 9 |

Language barriers and judgment in family planning and reproductive health services limited access [71] | “Well, language is a huge barrier… A lot of times women, even if they speak a little bit of English, you know I try to encourage them to go to another clinic because they haven’t had a checkup for, you know, god knows how long. The thing is always that ‘there are some things I want to discuss that I won’t know how to say in English. I may not understand what they are telling me.” (Canadian health care worker) (p. 374) | |

| “I have two Afghani women … and both of them thought they might be pregnant and want abortions. So they came on their own, and they actually didn’t want interpreters because they were worried that the interpreters would judge them because they believed in their interpretation of their religion that you cannot have access to, well, abortion services in general.” (Physician at community health center) (p. 375) | ||||

| Im/migrant Muslim women N = 6 |

A lack of awareness of religious and cultural practices hindered access to maternity health services [78] | “Like when I was pregnant during Ramadan [the month of fasting] and I asked my doctor about fasting. She told me ‘I don’t like to tell you not to fast.’ I prefer if there can be some Muslim physician who can give them more information about such topics. They don’t understand it. If they have more ideas about the issue it will be better.” (p. 107) | ||

| Family planning HCPs N = 9 |

Misconceptions and a lack of knowledge impacted family planning access experiences [71] | “The other thing I find totally doesn’t fly with the immigrant women … a lot of them don’t look down there, they don’t touch down there, they are so ashamed…” (p. 377) | ||

| “So it has been an uphill battle to explain about birth control and family planning. The notion of actually being able to make those decisions is also quite new to many couples. Even as a couple, because often it is traditionally seen as God’s will… [T]hat’s over quite a range of countries throughout the world.” (p. 377) | ||||

| Sri Lankan Tamil community leaders and im/migrants, assisting im/migrant women’s access to formal support for abuse N = 16 |

Lack of knowledge of available services due to language barriers limited access to intimate partner violence support [70] | “Maybe the woman has language issues. If she is a woman who has contacts outside, who’s going outside, and being able to talk to someone, she will know about services. Other women have no way to know who does what and what helps.” (p. 72) | ||

| Latin American im/migrant women N = 25 [permanent residents (N = 11), refugee status claimants (N = 10)] |

Language barriers and a lack of appropriate translation services created challenges in HIV/STI services [69] | “Health centres sometimes offered translating services but when unavailable, women had to find someone who could accompany them to their appointments, which created confidentiality issues. Moreover, many women felt uncomfortable talking about sexual and reproductive health matters in the presence of a translator.” (p. 421) | ||

| Muslim, West and South Asian im/migrant women N = 30 |

Different religious and cultural beliefs, language barriers and a preference for female physicians negatively shaped cervical cancer screening experiences [67] | “Health Care Connect program only ask for location preference, where you live, and then they will try to match in your area. You couldn’t set up for any other preferences. We usually have to find female doctors through friends and family.” (p. 7) | ||

| “There are GP’s who, I guess there are less culturally sensitive. I guess that’s what it is—we go to the doctor with our moms, and I’m not married and I’m not comfortable when my GP says “are you sexually active?” and my mom is sitting beside me. No I’m not!! (Laughs). So, that’s why it’s nice for a lot of us to choose a GP that’s are from our own culture because they won’t ask questions like, “are you sexually active?” (p. 7) | ||||

| New im/migrant women N = 11 |