Abstract

Cancer genomes frequently harbor structural chromosomal rearrangements that disrupt the linear DNA sequence order and copy number. To date, diverse classes of structural variants have been identified across multiple cancer types. These aberrations span a wide spectrum of complexity, ranging from simple translocations to intricate patterns of rearrangements involving multiple chromosomes. Although most somatic rearrangements are acquired gradually throughout tumorigenesis, recent interrogation of cancer genomes have uncovered novel categories of complex rearrangements that arises rapidly through a one-off catastrophic event, including chromothripsis and chromoplexy. Here we review the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to the formation of diverse structural rearrangement classes during cancer development. Genotoxic stress from a myriad of extrinsic and intrinsic sources can trigger DNA double-strand breaks that are subjected to DNA repair with potentially mutagenic outcomes. We also highlight how aberrant nuclear structures generated through mitotic cell division errors, such as rupture-prone micronuclei and chromosome bridges, can instigate massive DNA damage and the formation of complex rearrangements in cancer genomes.

Keywords: cancer genomes, genomic instability, chromosome rearrangements, chromothripsis, DNA damage, DNA repair, micronuclei, mitosis

1. INTRODUCTION

In the early 1900’s, Theodor Boveri postulated that a scrambled chromosomal content – presumably arising from uncontrolled cell division – can underlie cancer development (Boveri 2008). This was reaffirmed in the mid-1900’s by the discovery of the first recurrent cytogenetic rearrangement in leukemia patients harboring a chromosome 9 and 22 translocation, which generates an oncogenic gene fusion product (Nowell 1962; Rowley 1973). A century after Boveri’s initial hypothesis, the international Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium led a series of large-scale, systematic efforts characterizing the mutational features of >2,600 primary cancer genomes spanning 38 tumor types. Alongside somatic driver mutations, patterns of structural variation (SV) emerged, presenting a comprehensive overview of the genomic rearrangement landscape across diverse malignancies (Consortium 2020; Li et al. 2020; Rheinbay et al. 2020). These alterations are at least 50 nucleotides in length but can scale to megabase-sized genomic regions or even affect entire chromosomes (Sudmant et al. 2015). Additionally, SVs can be categorized into a broad spectrum of classes (Li et al. 2020) as dozens of distinct SVs comprising diverse forms of simple and complex rearrangement types have been identified across a range of cancers.

Rearrangements in the linear chromosomal sequence order can promote tumorigenesis through multiple routes, including DNA copy number changes resulting in the deletion of tumor suppressor genes or amplification of oncogenes (Yang et al. 2013; Zack et al. 2013). Rearrangement breakpoints occurring nearby or within genes and their regulatory elements can disrupt gene function and regulation (Zhang et al. 2020). Moreover, novel gene products can be formed when a rearrangement juxtaposes two normally-distant loci in close proximity to encode dysregulated or gain-of-function oncogenic fusion proteins (Tomlins et al. 2005). Hundreds of protein-coding gene fusions have been reported to date, some of which can directly drive tumorigenesis and/or serve as potent therapeutic vulnerabilities (Mertens et al. 2015). Structural rearrangements can also remodel the three-dimensional organization of the genome (Akdemir et al. 2020), further impacting gene regulation and genomic integrity.

Although SVs comprise a source of genetic variation (Collins et al. 2020) and can be causative of human congenital disorders (Carvalho and Lupski 2016), here we focus on the cellular and molecular mechanisms governing genomic rearrangement formation in the context of cancer development (Figure 1). Our current understanding of how diverse forms of rearrangements are generated in cancer genomes and their implications for clonal selection during tumorigenesis are highlighted. We also discuss how cells acquire DNA damage and the different forms of DNA repair pathways that are utilized in response to DNA breakage. Finally, we conclude with a discussion on how mitotic cell division errors can act as an initial trigger for catastrophic forms of complex genomic rearrangements.

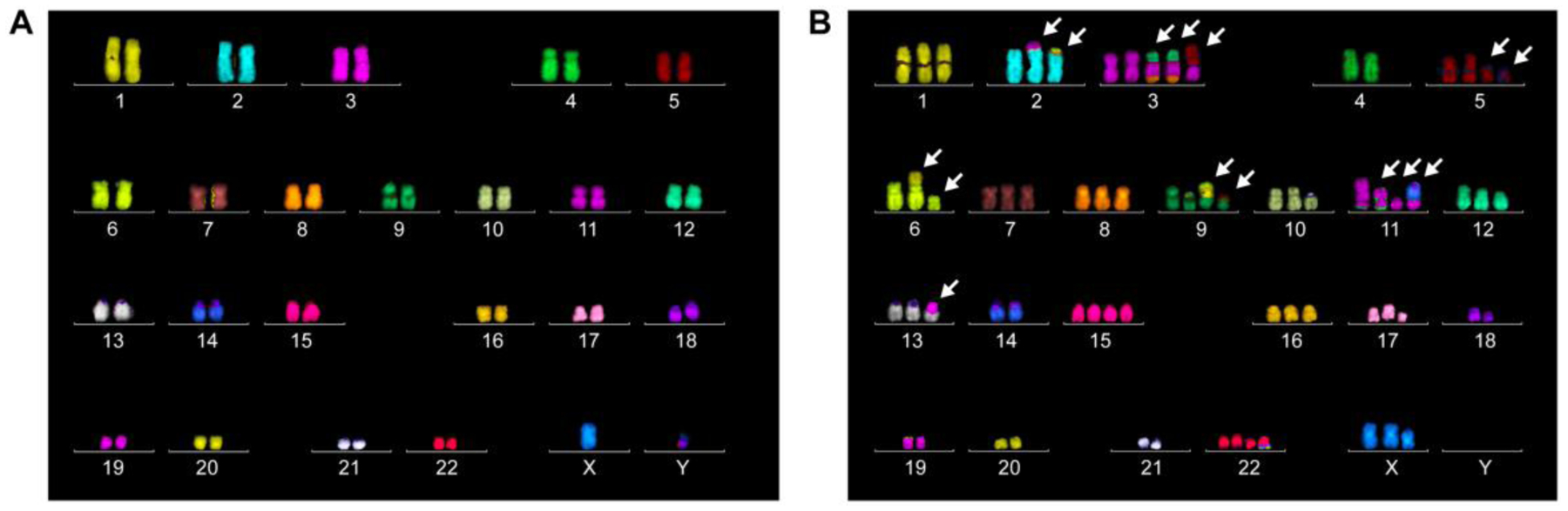

Figure 1. Karyotypic differences between normal and cancer genomes.

Representative multi-color DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of metaphase spreads derived from A) non-transformed diploid human epithelial cells or B) aneuploid human cervical cancer cells (HeLa). Arrows indicate chromosomes with detectable cytogenetic abnormalities.

2. REORGANIZING THE CANCER GENOME

2.1. Diverse spectrum of chromosomal rearrangements

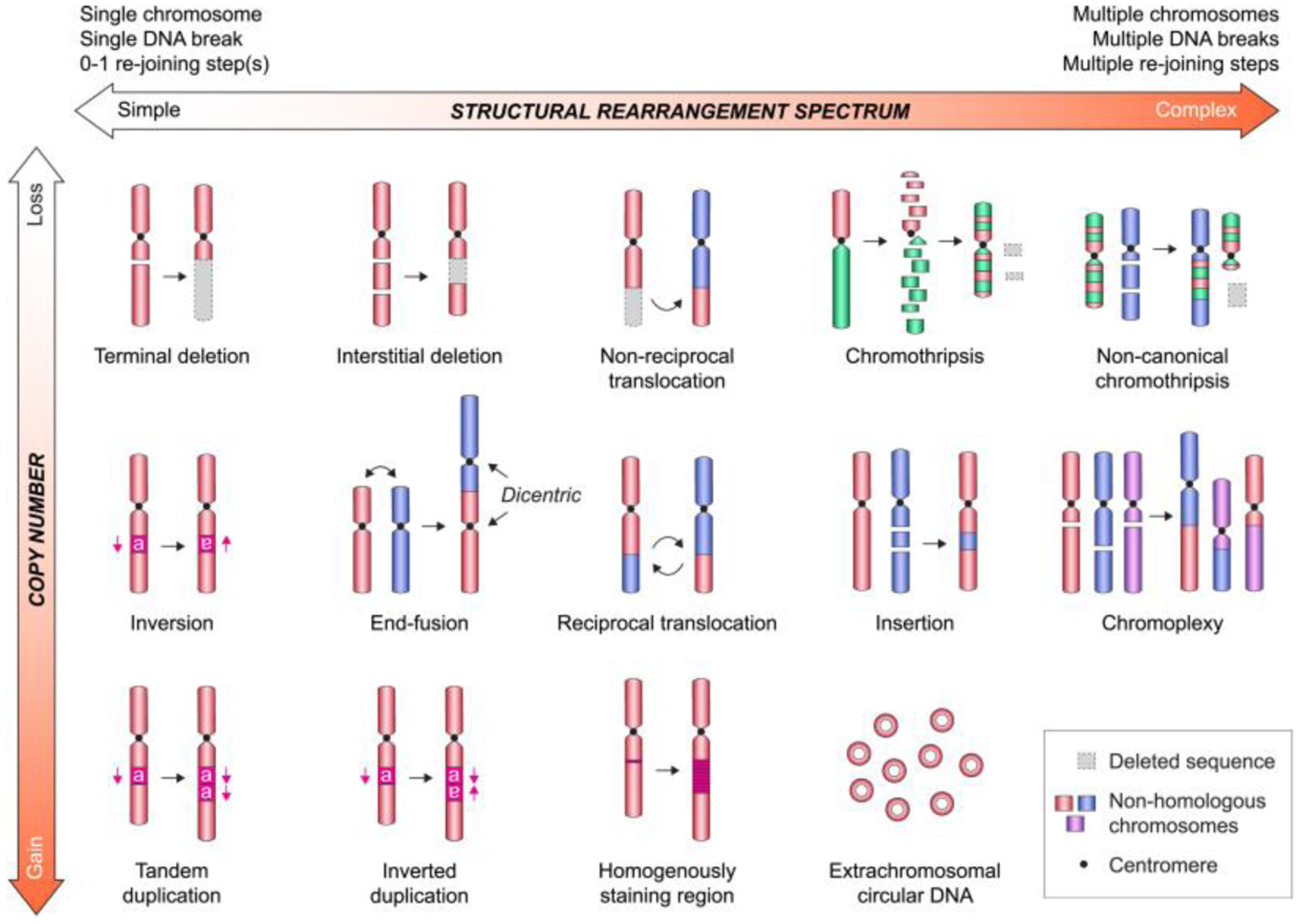

Genomic rearrangements can be loosely categorized on a spectrum that ranges from simple to complex based on the number of chromosomes and rearrangement breakpoints involved (Figure 2). At one end of the spectrum, simple rearrangements comprise relatively few breakpoints on one or two chromosome(s), commonly manifesting as deletions, duplications, translocations, insertions, and inversions. Terminal deletions, for example, are considered simple as it involves a single chromosome break without the involvement of a DNA repair step, although the capture of telomeric sequences may be required for genetic stability. Rearrangements can be further divided into unbalanced or balanced depending on whether DNA copy number has been affected (Weckselblatt and Rudd 2015). Whereas unbalanced rearrangements result in the net loss or gain of genetic material, balanced rearrangements alter only the linear DNA sequence order without changes in copy number. Examples of unbalanced SVs include deletions, duplications, and non-reciprocal translocations – the latter being defined by the unequal swapping of genetic material between two non-homologous chromosomes.

Figure 2. Diverse spectrum of chromosome rearrangements types in cancer.

Examples of structural rearrangement types shown in relative order of increasing complexity with or without DNA copy number changes. Note that variation in each rearrangement type is frequent in cancer and will shift its relative location on the spectrum.

On the other end of the spectrum, complex rearrangements frequently involve multiple breakpoints and/or several chromosomes, which are capable of generating intricate genomic patterns. Complex rearrangements are often challenging to detect using cytogenetic or array-based approaches that are incapable of recognizing submicroscopic or balanced alterations, respectively. Next-generation DNA sequencing offers higher sensitivity and resolution for the identification of complex rearrangements, although detecting the entire SV spectrum using any single method is challenging. The combination of various approaches coupled to technological and computational advancements have accelerated the discovery and annotation of novel SV classes in cancer genomes (Hu et al. 2020).

2.2. Complex genomic rearrangements

Genome sequencing has identified several distinct categories of complex rearrangements, including chromothripsis (Stephens et al. 2011) and chromoplexy (Berger et al. 2011) in cancer, as well as chromoanasynthesis (Liu et al. 2011) in genomic disorders. The term “chromoanagenesis” has been proposed to describe these catastrophic rearrangements regardless of their underlying mutational mechanism (Holland and Cleveland 2012). These rearrangements appear to form through a rapid burst of genomic instability, offering a divergent and accelerated route to tumorigenesis compared the established model of gradual cancer progression. Complex rearrangements can arise when numerous DNA breaks are concurrently present within the cell, capable of generating tens to hundreds of breakpoints. It is likely that additional rearrangement types are awaiting discovery. For example, recent exploration of cancer genomes has uncovered three classes of complex rearrangements – referred to as rigma, pyrgo, and tyfonas – each of which are associated with specific cancer types (Hadi et al. 2020). The mechanistic origins of these new SV classes remain unexplored.

2.2.1. Chromothripsis

Chromothripsis was first described in 2011 from a leukemia patient harboring 42 genomic rearrangements clustered on chromosome 4q, resulting in an oscillating DNA copy number pattern restricted to a 100 Mb region (Stephens et al. 2011). Rearrangement breakpoints were typically confined to only one or a few chromosomes or regions, and in one extreme case, >230 localized rearrangements were observed on a single chromosome in a colorectal cancer sample (Stephens et al. 2011). Computational simulations led to the prediction that chromothripsis arises during a single catastrophic event in which a chromosome shatters into multiple fragments followed by a haphazard attempt to reassemble these fragments. The outcome is often severe; multiple chromosomal regions are lost and the stitched-up chromosome becomes scrambled into a nearly unrecognizable configuration harboring a large number of rearrangements.

Over the last decade, there has been mounting interest in understanding the prevalence and biology of chromothripsis as a novel rearrangement class in cancer. Initial estimates leveraging genomic arrays reported an overall frequency of chromothripsis-like profiles in the range of 1–4% in human cancer cell lines (Stephens et al. 2011) and samples (Kim et al. 2013; Cai et al. 2014). The PCAWG Consortium recently provided comprehensive measurements from whole-genome sequencing data across 38 tumor types, and using a defined scoring criteria, chromothripsis was found to be pervasive across a wide range of tumor types with an overall frequency approaching 22% (Consortium 2020) and 29–40% (Cortés-Ciriano et al. 2020) from >2,600 cancer samples. These two independent pan-cancer measurements are consistent with more in-depth analysis of individual tumor types, for example, in pancreatic and renal cell cancers (Notta et al. 2016; Mitchell et al. 2018). Using a separate cohort of >600 adult cancer samples, whole-genome and -exome sequencing efforts reported a prevalence of 49% across 28 adult tumor types (Voronina et al. 2020).

Several criteria were proposed to rigorously infer chromothripsis, including oscillations between two to three DNA copy number states, clustering of breakpoints, and seemingly random patterns of rearrangements (Korbel and Campbell 2013). Non-canonical examples of chromothripsis are also frequent in which chromosomes exhibit elevated DNA copy number states (more than three) and/or the involvement of rearrangements with additional chromosomes (Cortés-Ciriano et al. 2020; Voronina et al. 2020). In addition, signatures of templated insertions and replication-associated processes were also observed (Cortés-Ciriano et al. 2020), suggesting that the complexity of genomic outcomes from chromothripsis may be driven by multiple mutational mechanisms.

Chromothripsis can impact multiple cancer-associated genes simultaneously; for example, by concurrently disrupting CDKN2A, WRN and FBXW7 in a chordoma sample (Stephens et al. 2011) or driving the formation of oncogenic fusion genes in lung adenocarcinomas (Lee et al. 2019). In addition, chromothripsis is observed in two-thirds of pancreatic tumors, suggesting a punctuated evolutionary trajectory that simultaneously perturbs multiple genes during cancer progression (Notta et al. 2016). It is important to note that punctuated and gradual routes to tumorigenesis are not mutually exclusive. During clear cell renal cell carcinoma development, chromothripsis can be an early, initiating event occurring through adolescence followed by the somatic loss of tumor suppressor genes many years later (Mitchell et al. 2018).

2.2.2. Chromoplexy

Shortly after the discovery of chromothripsis, sequencing efforts to characterize somatic DNA alterations in prostate cancer genomes unexpectedly identified a class of chained rearrangements called chromoplexy (Baca et al. 2013). In contrast to chromothripsis in which relatively few chromosomes are affected, chromoplexy describes an intricate series of loop-like rearrangements that seemingly connects multiple (up to seven) chromosomes. Although largely balanced in nature, numerous DNA rearrangements and segmental deletions between their breakpoints were reported to simultaneously dysregulate multiple cancer genes, supporting a punctuated evolution model of prostate tumorigenesis (Berger et al. 2011; Baca et al. 2013). Notably, chromoplexy in prostate cancer is strongly associated with gene fusions involving members of the ETS family of transcription factors. More recently, chromoplexy was also characterized in Ewing sarcoma in which the rearrangements generated frequent oncogenic fusion genes that are associated with increased aggressiveness (Anderson et al. 2018). Thus, chromoplexy can impact multiple cancer-associated genes to provide a proliferative or selective advantage to cancer cells. The mechanistic origins of chromoplexy are not fully understood but could potentially involve DSBs triggered at actively transcribed regions (Lin et al. 2009; Haffner et al. 2010). It is plausible that DSBs or perhaps transcription itself can facilitate repositioning of normally-distant loci in close three-dimensional proximity within the nucleus.

2.2.3. Chromoanasynthesis

Initially identified from genomic disorders, chromoanasynthesis is another catastrophic form of complex rearrangements (Liu et al. 2011) that share several features with chromothripsis in cancer genomes. Like chromothripsis, rearrangements from chromoanasynthesis are usually clustered into a local region or chromosome. The junctions of these rearrangement breakpoints, however, often harbor short templated insertions and exhibit higher microhomology usage. Notably, chromoanasynthesis generates a higher DNA copy number profile compared to chromothripsis, including frequent duplications and triplications (Liu et al. 2011). This has been attributed to defects during DNA replication, such as fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS) or MMBIR (Liu et al. 2011). In nematodes, clustered rearrangements resembling chromoanasynthesis were induced through exposure to chemical crosslinking agents, suggesting that initial genotoxic damage could perhaps trigger these replicative defects (Meier et al. 2014). Among the catastrophic rearrangements categorized as chromoanagenesis, however, chromoanasynthesis is the least understood in regards to its role and prevalence in human cancer. Despite distinctions in the underlying mechanism(s) driving these various forms of chromoanagenesis, its cellular consequences are similar – all three events result in the rapid acquisition of complex rearrangements generating highly scrambled chromosomes.

3. DNA DAMAGE DRIVING GENOME REARRANGEMENTS

How do diverse forms of simple and complex genomic rearrangements arise? A critical intermediate is the presence of broken DNA followed by the repair of such lesions by one or more intrinsic DNA repair pathways. Cells are continuously exposed to conditions that can damage DNA, representing a major threat to genome integrity. For example, a single DSB left unrepaired throughout the cell cycle and persisting into mitosis can result in terminal chromosomal deletions. To overcome this, cells have evolved a variety of robust DNA damage response (DDR) pathways to recognize diverse types of DNA lesions and repair the damage (Jackson and Bartek 2009).

3.1. Exogenous and endogenous sources of DNA damage

DNA is a highly reactive molecule that is vulnerable to chemical modifications by both exogenous and endogenous agents (Hoeijmakers 2009). Exogenous genotoxins are abundant in the environment, such as ionizing radiation, ultraviolet light, and diverse chemical mutagens (Tubbs and Nussenzweig 2017). Radiation exposure can induce a variety of DNA lesions, including DNA base alterations, clustered DNA damage, and single- and double-stranded breaks (Lomax et al. 2013). These lesions can result in a broad spectrum of genomic alterations (Huang et al. 2003; Suzuki et al. 2003), such as chromothripsis-like rearrangements (Morishita et al. 2016; Mladenov et al. 2018) and three-dimensional genome organization changes (Sanders et al. 2020). Ultraviolet light exposure also causes a wide range of DNA damage by inducing the formation of pyrimidine dimers (Douki et al. 2003), DNA–protein crosslinks (Gueranger et al. 2011), and oxidative base damage (Kvam and Tyrrell 1997). Chemical agents that cause DNA damage can also be utilized to target rapidly dividing cancer cells for chemotherapy. Alkylating agents induce DNA damage by generating covalent DNA adducts (Fu et al. 2012), while radiomimetic agents, such as bleomycin, can directly induce DSBs (Chen et al. 2008). Environmental mutagens and chemotherapeutic drugs such as DNA crosslinking agents can generate toxic DNA interstrand crosslinks that have the potential to form aberrant radial chromosomes when processed by specific DNA repair pathways (Deans and West 2011; Huang and Li 2013).

DNA damage can also be inflicted by a myriad of endogenous sources. Reactive oxygen species generated through normal cellular physiology and metabolic processes represent a major source of oxidative stress-induced single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) lesions (Mani et al. 2016). During DNA synthesis, ssDNA breaks can become converted into DSBs upon encountering a replication fork (Kuzminov 2001) and disassembly of the replisome (Vrtis et al. 2021). Replication stress can be caused by several factors – such as oncogene activation, DNA polymerase inhibition, and collision between the replication fork with the transcriptional machinery – that can promote replication fork stalling or collapse leading to DSB formation. For example, mild replication stress through low dose treatment with the DNA polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin can cause breakage of common fragile sites in the genome (Glover et al. 1984). Oncogene activation can also provoke DNA damage; for example, high expression of the E2F transcription factor drives premature cell cycle entry into S-phase with a depleted nucleotide pool, in turn triggering DNA replication stress (Bester et al. 2011). Lastly, defects in specific DNA repair pathways can result in a predisposition to chromosomal alterations. Tandem duplications ~10 kb in size are associated with BRCA1-deficiency in breast and ovarian cancers (Nik-Zainal et al. 2016; Menghi et al. 2018), which mechanistically arises from stalled replication forks in the absence of BRCA1 (Willis et al. 2017).

3.2. DNA repair and its consequences on genome integrity

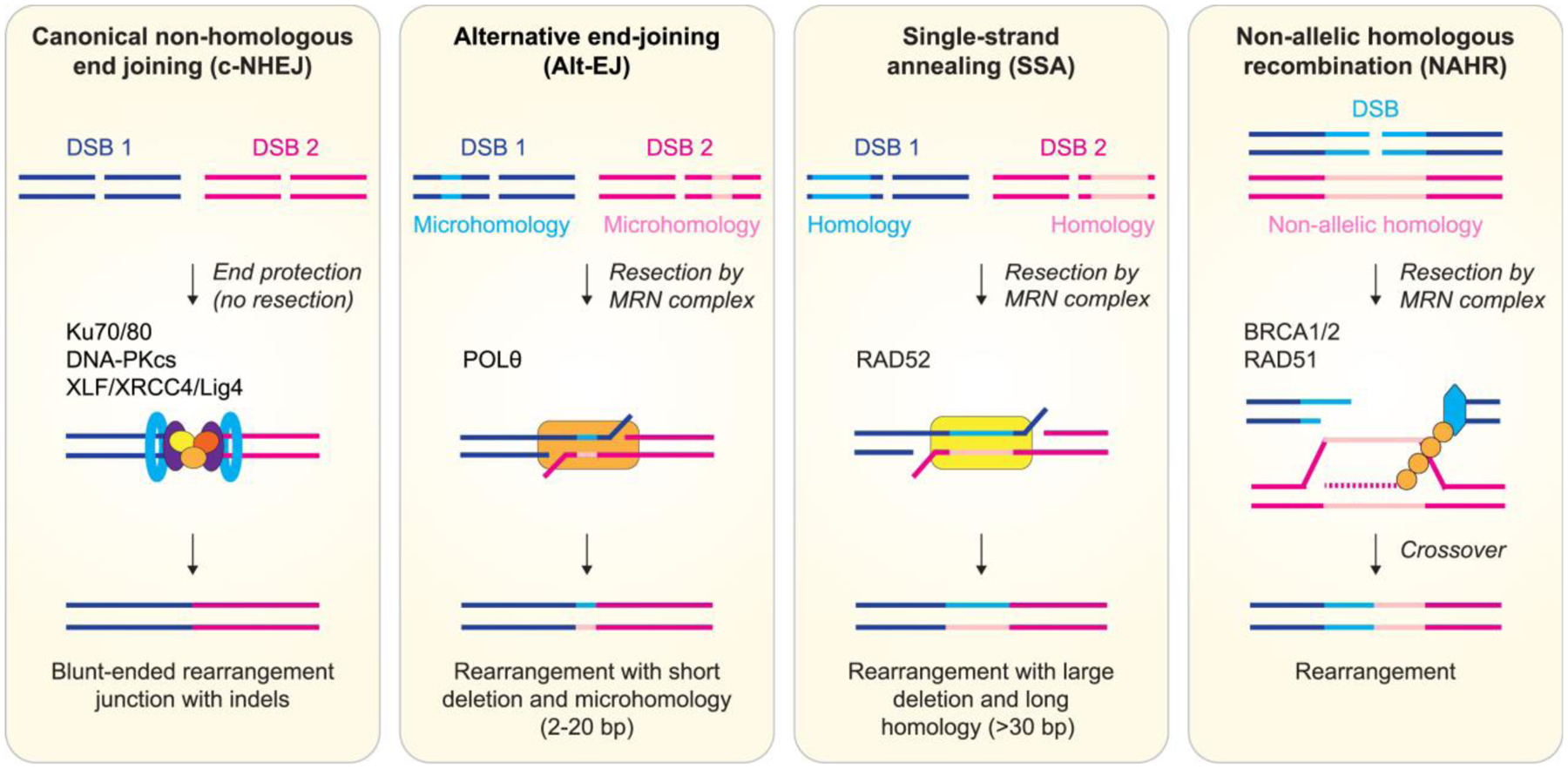

DNA damage can be repaired through a variety of mechanisms (Jackson and Bartek 2009). Here we focus on the major DNA repair pathways for DSBs as they represent a critical intermediate for generating chromosomal rearrangements (Figure 3) (Richardson and Jasin 2000). These DSBs are primarily repaired through two major routes involving DNA end-joining or recombination. The choice between distinct DSB pathways is determined by multiple factors, including the nature and environment of the break with respect to cell cycle stage, chromatin status, and position within the nucleus. Although some DNA repair pathways are considered intrinsically accurate, virtually all modes of repair have some capacity to form mutagenic rearrangements.

Figure 3. Mutagenic repair outcomes of DNA double-strand breaks.

Major DNA double-strand break repair pathways operative in mammalian cells are shown with an emphasis on their repair outcomes to generate chromosomal rearrangements. Blue and pink lines depict distinct DNA double-strand breaks arising from different genomic loci that are simultaneously present. Light shaded lines represent stretches of microhomologous or homologous sequence.

3.2.1. End joining-mediated DSB repair

Canonical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ) is a dominant DSB repair pathway that directly ligates DSB ends in a manner that is independent of homology or microhomology. In this pathway, the Ku70/Ku80 complex binds to DSBs and initiates the ligation process through the recruitment of DNA-PKcs, XLF, and LIG4–XRCC4 (Pannunzio et al. 2018). Although c-NHEJ is active at all phases throughout the cell cycle, it is the major repair pathway during G1 phase (Symington and Gautier 2011) where it encounters less competition for DSB ends by other repair mechanisms. C-NHEJ is an error-prone repair pathway due to its ability to promiscuously ligate any two compatible DSB ends in non-specific fashion, which can promote the formation of chromosomal rearrangements if multiple DSBs are present (Ghezraoui et al. 2014). In addition, processing of DSB ends through c-NHEJ can result in short insertion and deletion mutations at breakpoint junctions (Bhargava et al. 2018).

Alternative end joining (alt-EJ) refers to one or more distinct modes of end joining-mediated DSB repair that do not involve the core c-NHEJ machinery. The best characterized alt-EJ pathway is often referred to as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), which appears to be most active throughout S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle (Yu et al. 2020). The physiological role of alt-EJ in DSB repair remains to be fully understood, although it was originally discovered as a backup or minor repair system in the absence of a functional c-NHEJ pathway (Kabotyanski et al. 1998). Alt-EJ is an intrinsically mutagenic pathway that generates deletions flanking re-ligated DSB ends. This is initiated by DSB end resection involving the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex along with CtIP, which uncovers internal microhomology sequences on ssDNA overhangs that becomes aligned and annealed across two DSB ends. This is subsequently followed by synthesis of the resected ends by DNA polymerase theta (Polθ) (Chan et al. 2010) and ligation by LIG3 (Audebert et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2005). Whereas breakpoint junctions repaired by c-NHEJ carry 0–2 nucleotides of microhomology, those repaired by alt-EJ exhibit longer microhomology (up to 25 nucleotides in length), variable sized insertions and deletions, and an elevated frequency of chromosomal rearrangements (Simsek et al. 2011; Zhang and Jasin 2011; Mateos-Gomez et al. 2015).

3.2.2. Single-strand annealing

Single-strand annealing (SSA) is a repair pathway for DSBs flanked by longer tracts of repeat sequences compared to microhomology utilized by alt-EJ. SSA relies on extensive end resection and bridging of DSB ends through the annealing of long homologous sequence shared by both ends of the DSB. RAD52 mediates synapsis of the annealing intermediates during SSA repair (Mortensen et al. 1996; Stark et al. 2004). Due to extensive end resection, the outcome of SSA is a deletion between the two repeats coupled to the loss of one repeat. These deletions are usually larger than those caused by alt-EJ, with >25 kb deletions mediated by SSA events detected in yeast (Vaze et al. 2002).

3.2.3. Recombination-mediated DSB repair

Homologous recombination (HR) is usually considered an error-free repair pathway and involves a multi-step process stimulated by a DSB. First, BRCA1 blocks the 53BP1-Shieldin complex at DSBs to initiate end resection by the MRN complex to generate ssDNA (Escribano-Diaz et al. 2013). These ssDNA tails are coated with RPA, and with assistance of the BRCA complex (BRCA1-PALB2-BRCA2), RAD51 displaces RPA to form RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments. These filaments mediate homology search throughout the genome and strand invasion, which is a major differentiating step for HR compared to other repair pathways. HR is accurate when it utilizes homologous sequence from an allelic sister chromatid to serve as a template for DNA synthesis. However, HR can be mutagenic when somatic recombination occurs between non-allelic regions with high sequence similarity, homologous chromosomes (LaRocque et al. 2011), or heterologous sequences (Leon-Ortiz et al. 2018). In addition, HR can generate complex rearrangements when ssDNA invades more than one donor sequence, a recently described process termed multi-invasion-induced rearrangements (Piazza et al. 2017).

Break-induced replication (BIR) is a subtype of HR employed in the repair of one- or two- -ended DSBs that only share one side of homology with the template (Kramara et al. 2018). BIR has an important role in repairing broken or collapsed replication forks generated by replication stress (Costantino et al. 2014; Sotiriou et al. 2016); however, this pathway can be hyper-mutagenic. BIR can produce extensive mutations and loss-of-heterozygosity due to its conservative mode of DNA synthesis (Smith et al. 2009; Deem et al. 2011; Donnianni and Symington 2013; Saini et al. 2013). The long-lived ssDNAs generated during BIR could also induce mutation clusters that resemble localized hypermutation termed kataegis (Sakofsky et al. 2014; Elango et al. 2019). Moreover, BIR is capable of provoking gross chromosomal rearrangements such as genomic duplications and non-reciprocal translocations (Bosco and Haber 1998; Costantino et al. 2014). Microhomology-mediated BIR (MMBIR) increases the possibility of mutagenic outcomes as template switching can occur between ssDNA tails from the broken replication fork to any microhomologous sequence (Hastings et al. 2009), in turn generating complex rearrangements reminiscent of those observed in human cancers and disorders (Lee et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2009; Mayle et al. 2015).

4. COMPLEX REARRANGEMENTS FROM CELL DIVISION ERRORS

4.1. Mitotic errors generating aberrant nuclear structures

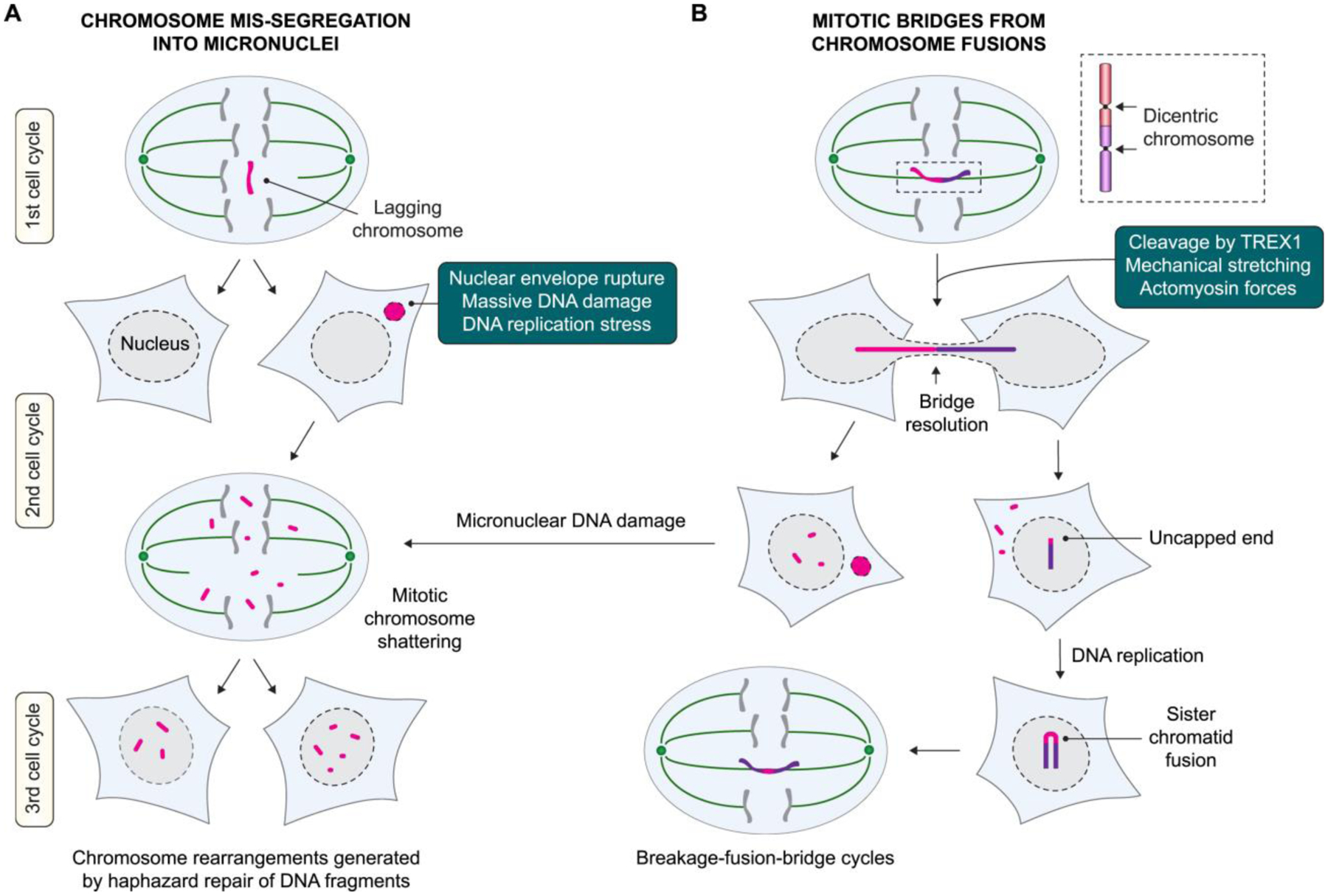

The goal of cell division is to achieve accurate segregation of the duplicated genome to generate two genetically identical daughter cells. The mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint acts as a safeguard to delay chromosome segregation at anaphase onset until all sister chromatid pairs have properly attached to bipolar spindle microtubules. Defects in these tightly controlled processes can promote genomic instability by driving chromosome segregation defects, which has long been recognized as the major source of aneuploidy, an abnormal number of chromosomes. However, mitotic errors have more recently emerged as a trigger for structural aberrations. This was initially reported a decade ago when lagging chromosomes trapped in the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis were shown to be susceptible to DNA damage and the formation of chromosomal translocations (Janssen et al. 2011). In addition, chromosome missegregation can generate abnormal nuclear structures, including micronuclei when chromosomes are improperly aligned during metaphase and/or lag behind during anaphase (Thompson and Compton 2011). DSBs persisting unrepaired into mitosis can also produce micronuclei from the missegregation of acentric chromosome fragments (Leibowitz et al. 2020). In parallel, chromosome bridges are formed when a single chromosome is erroneously pulled in opposing directions toward both mitotic spindle poles. Here we describe recent findings on how micronuclei (Figure 4a) and chromosome bridge (Figure 4b) formation can rapidly instigate catastrophic genomic rearrangements, highlighting the importance of chromosome segregation fidelity during mitosis.

Figure 4. Complex rearrangements formed through cell division errors and aberrant nuclear structures.

A) Whole-chromosome segregation errors during mitosis can generate micronuclei, which acquire extensive DNA damage to trigger catastrophic shattering. Chromosome fragments that are reintegrated into daughter cell nuclei activate the DNA damage response and serve as substrates for error-prone DNA repair. B) Chromosome fusions producing a dicentric chromosome can form a bridge during mitosis when pulled toward opposing spindle poles. These bridges connect both daughter cells and become resolved during interphase, which can trigger micronucleus formation, subsequent cycles of breakage-fusion-bridge, and/or additional complex DNA rearrangements.

4.2. DNA damage in micronuclei and chromosome fragmentation

At the exit of mitosis, the nuclear envelope (NE) is reassembled to encapsulate the contents of the newly formed nucleus. If lagging or misaligned chromosomes are spatially separated from the primary genomic mass during NE assembly, a distinct NE will form surrounding the missegregated chromosome to generate a micronucleus, which appears as a small, nucleus-like structure located adjacent to the primary nucleus. Micronuclei are defective in several biological processes that become further exacerbated by the sudden and irreversible loss of nuclear membrane integrity, a process termed NE rupture (Hatch et al. 2013). Rupturing triggers the loss of nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization, causing micronuclear contents to spill out into the cytoplasm, and conversely, cytoplasmic components to leak into the micronucleus (Hatch et al. 2013). In turn, NE rupture coincides with a reduction in transcriptional activity, defective DNA replication, and the acquisition of micronuclear DSBs during interphase (Crasta et al. 2012; Hatch et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2017). Thus, chromosomes partitioned into micronuclei are highly unstable, providing a mechanistic source for localized DNA damage caused by an initial error during mitosis (Ly and Cleveland 2017).

Why are micronuclei prone to NE rupture? Improper assembly of the NE surrounding lagging chromosomes can mediate loss of specific NE components on micronuclear membranes (Liu et al. 2018). The extreme curvature of micronuclei also enables the accumulation of ESCRT-III, the membrane fission machinery that is critical for the maintenance of NE stability. This unrestrained recruitment and activity of ESCRT-III mediates deformities in the membrane and subsequent NE collapse (Vietri et al. 2020). The exact cause(s) of DNA damage within micronuclei are poorly understood. The ER-associated exonuclease TREX1 has been suggested to trigger micronuclear DNA damage following NE rupture (Mohr et al. 2021). However, micronuclei can still acquire DNA damage in cells lacking TREX1, indicating the involvement of other nuclease(s) and/or nuclease-independent mechanisms for facilitating micronuclear DNA damage.

Micronuclear chromosomes are susceptible to catastrophic shattering, which produces dozens of chromosome fragments that are detectable on metaphase spreads (Crasta et al. 2012; Ly et al. 2017). This is likely triggered by the presence of multiple DSBs and/or incomplete DNA replication intermediates owing to delayed DNA synthesis persisting into mitosis. Disassembly of the NE during early mitosis unloads chromosome fragments from micronuclei into the mitotic cytoplasm, although it remains unclear how these DNA fragments, most of which lack a centromere, are segregated between daughter cells. After reincorporation into daughter cell nuclei at the completion of mitosis, these DNA fragments reassemble to form a derivative chromosome harboring the characteristics of canonical and non-canonical chromothripsis (Zhang et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2019). DNA repair by both c-NHEJ and alt-EJ have been implicated in the reassembly process to generate chromothripsis (Zhang et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2017; Ratnaparkhe et al. 2018; Ly et al. 2019), consistent with the presence of minimal sequence homology at chromothriptic junctions in cancer genomes (Stephens et al. 2011; Kloosterman et al. 2012; Cortés-Ciriano et al. 2020). Several features remain difficult to fully explain from micronuclei-mediated mechanisms – including rearrangements spanning multiple chromosomes, unexpected DNA copy number increases, and templated insertions –possibly suggesting the involvement of mutagenic events beyond chromosome fragmentation and reassembly.

In addition to chromothripsis, diverse chromosomal alterations can arise from the reassembly of chromosome fragments derived from micronuclei, including a wide spectrum of simple and complex rearrangements (Ly et al. 2019) (Figure 2). This is perhaps mediated by several factors, including the degree of DNA damage acquired within the micronucleus, how chromosome fragments are partitioned into the daughter cells during mitosis, and the DNA repair pathway choice for reassembling these DNA fragments. The presence of additional DSBs elsewhere in the genome may also serve as substrates for fragment repair, which may underlie the origins of inter-chromosomal rearrangements with properly segregating, non-micronuclear chromosomes. Interestingly, these chromosome fragments can self-ligate into circular extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) structures (classically referred to as double minutes) (Zhang et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2019; Shoshani et al. 2020), which can vary in size from hundreds of kilobases to a megabase. In cancer, ecDNAs frequently harbor one or more oncogenes (Kim et al. 2020) and/or genes conferring resistance to chemotherapy (Nathanson et al. 2014), the amplification of which could provide a selective benefit and promote tumor heterogeneity (Turner et al. 2017). In addition, some chromothripsis-mediated rearrangements are accompanied by the signatures of kataegis (Maciejowski et al. 2015; Ly et al. 2019; Maciejowski et al. 2020), which describes hypermutation hotspots consisting of C>T-specific substitutions (Nik-Zainal et al. 2012). Thus, in relatively few cell cycles, chromothripsis generated from micronuclei can instigate genomic features associated with cancer development and/or anti-cancer therapies.

4.3. Genome complexity from chromosome bridges

Chromosome bridges are another source of abnormal nuclear structures that can promote the formation of complex rearrangements (Figure 4b). The ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes are comprised of telomeres, nucleoprotein structures that are capped by the shelterin complex to protect against recognition and activation of the DDR (De Lange 2005). Telomeric DNA sequences are subjected to progressive shortening during each replication cycle, and once critically short, telomeres become uncapped through the loss of shelterin and resemble DSBs. Dysfunctional telomeric ends can be repaired by c-NHEJ or alt-EJ to generate abnormal fusions between two non-homologous chromosomes or replicated sister chromatids (Rai et al. 2010; Liddiard et al. 2016; Liddiard et al. 2019). These fusion events can produce a dicentric chromosome harboring two functional centromeres, both of which are capable of binding to the mitotic spindle apparatus. Chromosome bridges subsequently arise when the dicentric chromosome is simultaneously pulled towards opposite spindle poles during anaphase. Although chromosome bridges can be detected in the midzone during cytokinesis, they infrequently break and instead survive as strands of DNA connecting incompletely separated daughter cells (Maciejowski et al. 2015).

Throughout interphase, DNA bridges can be resolved by microtubule forces (Pampalona et al. 2016), bridge stretching caused by cell migration, actomyosin-dependent mechanical force, (Umbreit et al. 2020) and/or attack by the TREX1 exonuclease (Maciejowski et al. 2015; Maciejowski et al. 2020). Different mutational outcomes have been reported to arise depending on the nature of bridge breakage. Complex breaks, which are perhaps mediated by TREX1 cleavage, can cause fragmentation of the bridged region to generate arm-level chromothripsis (Maciejowski et al. 2015; Maciejowski et al. 2020). By contrast, simple breaks followed by DNA replication can provoke the fusion of broken sister chromatid ends to initiate a second round of chromosome bridge formation (Shoshani et al. 2020; Umbreit et al. 2020) – a process termed breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) (McClintock 1941; McClintock 1942). Ensuing cycles of BFB over multiple cell cycles can generate a series of inverted amplifications on the initially fused chromosome (Bianchi et al. 2019). Bridge resolution can also produce DNA stubs that manifest as abnormal structures such as nuclear bulges and micronuclei, which itself can experience additional DNA damage and/or defective DNA replication, presumably mediated by BIR or MMBIR (Cleal et al. 2019; Shoshani et al. 2020; Umbreit et al. 2020). Furthermore, these chromosomes exhibit a reduction in critical centromere- and kinetochore-associated components, indicating that they may be prone to further instability (Soto et al. 2018; Umbreit et al. 2020). Thus, repeated cycles of BFB, micronucleation, and chromothripsis can contribute to the complex landscape of cancer genomes, including the formation of oncogene-containing ecDNAs (Shoshani et al. 2020) and potentially large supernumerary accessory chromosomes known as neochromosomes (Garsed et al. 2014).

Ultra-fine bridges (UFBs) represent a separate class of chromosome bridges and have been recognized as a potential source of chromosomal instability in cancer genomes (Naim and Rosselli 2009; Tiwari et al. 2018). Under conditions of replication stress, UFBs can originate at common fragile sites from under-replicated DNA. The failure to properly resolve late DNA intermediates prior to cell division causes bridging of sister chromatids (Chan et al. 2009). UFBs are compositionally different from dicentric chromosome bridges as they lack detectable histones but instead associate with Bloom’s syndrome helicase proteins, including BLM and PICH, and the ssDNA-binding protein RPA (Baumann et al. 2007; Chan et al. 2007). UFBs arising from recombination intermediates are susceptible to breakage and the formation of chromosome fusions (Chan et al. 2018).

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

SVs are a hallmark feature of cancer genomes, capable of rearranging DNA at diverse scales that range from the disruption of a single gene locus to reconfiguring entire chromosomes. Cytogenetic- and array-based approaches have long established many simple rearrangement types that are recurrent in human cancer, such as specific chromosomal translocations and deletions. Advancements in DNA sequencing technologies and computational analyses have heralded the discovery of previously unrecognized rearrangement patterns across multiple cancer types. This includes classes of catastrophic rearrangements that support a ‘punctuated evolution’ route to tumorigenesis, which has broadly reshaped our perspectives on tumor evolution over the past decade.

The rearrangements of chromoanagenesis appear consistent with such a punctuated model whereby multiple genetic lesions are generated during a transient burst of genomic instability. Chromoanagenesis can accelerate cancer genome evolution by concurrently instigating multiple tumor-promoting events in one catastrophic event, which can span relatively few cell cycles, as is the case for chromothripsis and likely chromoplexy. Defects in cell cycle checkpoints, such as the p53 pathway, could potentially predispose cells to chromothripsis by circumventing cell cycle arrest in response to mitotic errors, massive DNA damage, and/or structural chromosomal alterations (Thompson and Compton 2010; Santaguida et al. 2017; Soto et al. 2017). Indeed, in some tumor contexts, chromothripsis appears to be correlated with p53 deficiency (Rausch et al. 2012). Cells that can tolerate and recover from chromothripsis can potentially acquire the proper set of oncogenic alterations that enables a selective fitness advantage for clonal propagation (Mardin et al. 2015; Kneissig et al. 2019).

While much insight into the mechanisms of chromothripsis has been recently obtained from a variety of experimental systems, it remains unclear precisely how chromoplexy and chromoanasynthesis arises. In addition, it is feasible that as-of-yet identified rearrangement types still await discovery in the genomes of human cancers. A deeper exploration of the mechanisms generating diverse forms of SVs and their contributions to tumorigenesis will be essential for understanding the origins of complex cancer genomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth Maurais and Alison Guyer for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R00CA218871 to P.L.), Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR180050 to P.L.), and UT Southwestern Circle of Friends Research Award (to P.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akdemir KC, Le VT, Chandran S, Li Y, Verhaak RG, Beroukhim R, Campbell PJ, Chin L, Dixon JR, Futreal PA et al. 2020. Disruption of chromatin folding domains by somatic genomic rearrangements in human cancer. Nat Genet 52: 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ND, de Borja R, Young MD, Fuligni F, Rosic A, Roberts ND, Hajjar S, Layeghifard M, Novokmet A, Kowalski PE. 2018. Rearrangement bursts generate canonical gene fusions in bone and soft tissue tumors. Science 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audebert M, Salles B, Calsou P. 2004. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining. J Biol Chem 279: 55117–55126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, Park K, Kitabayashi N, MacDonald TY, Ghandi M. 2013. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell 153: 666–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann C, Körner R, Hofmann K, Nigg EA. 2007. PICH, a centromere-associated SNF2 family ATPase, is regulated by Plk1 and required for the spindle checkpoint. Cell 128: 101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Sboner A, Esgueva R, Pflueger D, Sougnez C. 2011. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature 470: 214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester AC, Roniger M, Oren YS, Im MM, Sarni D, Chaoat M, Bensimon A, Zamir G, Shewach DS, Kerem B. 2011. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell 145: 435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava R, Sandhu M, Muk S, Lee G, Vaidehi N, Stark JM. 2018. C-NHEJ without indels is robust and requires synergistic function of distinct XLF domains. Nature Communications 9: 2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi JJ, Murigneux V, Bedora-Faure M, Lescale C, Deriano L. 2019. Breakage-fusion-bridge events trigger complex genome rearrangements and amplifications in developmentally arrested T cell lymphomas. Cell Reports 27: 2847–2858. e2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco G, Haber JE. 1998. Chromosome break-induced DNA replication leads to nonreciprocal translocations and telomere capture. Genetics 150: 1037–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri T 2008. Concerning the origin of malignant tumours by Theodor Boveri. Translated and annotated by Henry Harris. Journal of Cell Science 121: 1–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Kumar N, Bagheri HC, von Mering C, Robinson MD, Baudis M. 2014. Chromothripsis-like patterns are recurring but heterogeneously distributed features in a survey of 22,347 cancer genome screens. BMC Genomics 15: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. 2016. Mechanisms underlying structural variant formation in genomic disorders. Nature Reviews Genetics 17: 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, North PS, Hickson ID. 2007. BLM is required for faithful chromosome segregation and its localization defines a class of ultrafine anaphase bridges. The EMBO Journal 26: 3397–3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Palmai-Pallag T, Ying S, Hickson ID. 2009. Replication stress induces sister-chromatid bridging at fragile site loci in mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 11: 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SH, Yu AM, McVey M. 2010. Dual roles for DNA polymerase theta in alternative end-joining repair of double-strand breaks in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 6: e1001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YW, Fugger K, West SC. 2018. Unresolved recombination intermediates lead to ultra-fine anaphase bridges, chromosome breaks and aberrations. Nature Cell Biology 20: 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ghorai MK, Kenney G, Stubbe J. 2008. Mechanistic studies on bleomycin-mediated DNA damage: multiple binding modes can result in double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 3781–3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleal K, Jones RE, Grimstead JW, Hendrickson EA, Baird DM. 2019. Chromothripsis during telomere crisis is independent of NHEJ, and consistent with a replicative origin. Genome Res 29: 737–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Brand H, Karczewski KJ, Zhao X, Alfoldi J, Francioli LC, Khera AV, Lowther C, Gauthier LD, Wang H et al. 2020. A structural variation reference for medical and population genetics. Nature 581: 444–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium ITP-CAoWG. 2020. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 578: 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Ciriano I, Lee JJ-K, Xi R, Jain D, Jung YL, Yang L, Gordenin D, Klimczak LJ, Zhang C-Z, Pellman DS. 2020. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nature Genetics 52: 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino L, Sotiriou SK, Rantala JK, Magin S, Mladenov E, Helleday T, Haber JE, Iliakis G, Kallioniemi OP, Halazonetis TD. 2014. Break-Induced Replication Repair of Damaged Forks Induces Genomic Duplications in Human Cells. Science 343: 88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D. 2012. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature 482: 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange T 2005. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes & Development 19: 2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans AJ, West SC. 2011. DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 11: 467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deem A, Keszthelyi A, Blackgrove T, Vayl A, Coffey B, Mathur R, Chabes A, Malkova A. 2011. Break-Induced Replication Is Highly Inaccurate. PLOS Biology 9: e1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnianni RA, Symington LS. 2013. Break-induced replication occurs by conservative DNA synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110: 13475–13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Reynaud-Angelin A, Cadet J, Sage E. 2003. Bipyrimidine photoproducts rather than oxidative lesions are the main type of DNA damage involved in the genotoxic effect of solar UVA radiation. Biochemistry 42: 9221–9226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elango R, Osia B, Harcy V, Malc E, Mieczkowski PA, Roberts SA, Malkova A. 2019. Repair of base damage within break-induced replication intermediates promotes kataegis associated with chromosome rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribano-Diaz C, Orthwein A, Fradet-Turcotte A, Xing M, Young JT, Tkac J, Cook MA, Rosebrock AP, Munro M, Canny MD et al. 2013. A cell cycle-dependent regulatory circuit composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP controls DNA repair pathway choice. Mol Cell 49: 872–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD. 2012. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nature Reviews Cancer 12: 104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsed DW, Marshall OJ, Corbin VD, Hsu A, Di Stefano L, Schroder J, Li J, Feng ZP, Kim BW, Kowarsky M et al. 2014. The architecture and evolution of cancer neochromosomes. Cancer Cell 26: 653–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezraoui H, Piganeau M, Renouf B, Renaud J-B, Sallmyr A, Ruis B, Oh S, Tomkinson AE, Hendrickson Eric A, Giovannangeli C et al. 2014. Chromosomal Translocations in Human Cells Are Generated by Canonical Nonhomologous End-Joining. Molecular Cell 55: 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover TW, Berger C, Coyle J, Echo B. 1984. DNA polymerase alpha inhibition by aphidicolin induces gaps and breaks at common fragile sites in human chromosomes. Hum Genet 67: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueranger Q, Kia A, Frith D, Karran P. 2011. Crosslinking of DNA repair and replication proteins to DNA in cells treated with 6-thioguanine and UVA. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 5057–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi K, Yao X, Behr JM, Deshpande A, Xanthopoulakis C, Tian H, Kudman S, Rosiene J, Darmofal M, DeRose J et al. 2020. Distinct Classes of Complex Structural Variation Uncovered across Thousands of Cancer Genome Graphs. Cell 183: 197–210 e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner MC, Aryee MJ, Toubaji A, Esopi DM, Albadine R, Gurel B, Isaacs WB, Bova GS, Liu W, Xu J et al. 2010. Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nat Genet 42: 668–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PJ, Ira G, Lupski JR. 2009. A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet 5: e1000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch EM, Fischer AH, Deerinck TJ, Hetzer MW. 2013. Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei. Cell 154: 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JHJ. 2009. DNA Damage, Aging, and Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 361: 1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. 2012. Chromoanagenesis and cancer: mechanisms and consequences of localized, complex chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Medicine 18: 1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Maurais EG, Ly P. 2020. Cellular and genomic approaches for exploring structural chromosomal rearrangements. Chromosome Res 28: 19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Snyder AR, Morgan WF. 2003. Radiation-induced genomic instability and its implications for radiation carcinogenesis. Oncogene 22: 5848–5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li L. 2013. DNA crosslinking damage and cancer - a tale of friend and foe. Transl Cancer Res 2: 144–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Bartek J. 2009. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 461: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen A, van der Burg M, Szuhai K, Kops GJ, Medema RH. 2011. Chromosome segregation errors as a cause of DNA damage and structural chromosome aberrations. Science 333: 1895–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabotyanski EB, Gomelsky L, Han JO, Stamato TD, Roth DB. 1998. Double-strand break repair in Ku86- and XRCC4-deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 5333–5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Nguyen NP, Turner K, Wu S, Gujar AD, Luebeck J, Liu J, Deshpande V, Rajkumar U, Namburi S et al. 2020. Extrachromosomal DNA is associated with oncogene amplification and poor outcome across multiple cancers. Nat Genet 52: 891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TM, Xi R, Luquette LJ, Park RW, Johnson MD, Park PJ. 2013. Functional genomic analysis of chromosomal aberrations in a compendium of 8000 cancer genomes. Genome Res 23: 217–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman Wigard P, Tavakoli-Yaraki M, van Roosmalen Markus J, van Binsbergen E, Renkens I, Duran K, Ballarati L, Vergult S, Giardino D, Hansson K et al. 2012. Constitutional Chromothripsis Rearrangements Involve Clustered Double-Stranded DNA Breaks and Nonhomologous Repair Mechanisms. Cell Reports 1: 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneissig M, Keuper K, de Pagter MS, van Roosmalen MJ, Martin J, Otto H, Passerini V, Sparr AC, Renkens I, Kropveld F. 2019. Micronuclei-based model system reveals functional consequences of chromothripsis in human cells. Elife 8: e50292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbel JO, Campbell PJ. 2013. Criteria for inference of chromothripsis in cancer genomes. Cell 152: 1226–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramara J, Osia B, Malkova A. 2018. Break-Induced Replication: The Where, The Why, and The How. Trends Genet 34: 518–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzminov A 2001. Single-strand interruptions in replicating chromosomes cause double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 8241–8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam E, Tyrrell RM. 1997. Induction of oxidative DNA base damage in human skin cells by UV and near visible radiation. Carcinogenesis 18: 2379–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRocque JR, Stark JM, Oh J, Bojilova E, Yusa K, Horie K, Takeda J, Jasin M. 2011. Interhomolog recombination and loss of heterozygosity in wild-type and Bloom syndrome helicase (BLM)-deficient mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: 11971–11976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. 2007. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell 131: 1235–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Park S, Park H, Kim S, Lee J, Lee J, Youk J, Yi K, An Y, Park IK et al. 2019. Tracing Oncogene Rearrangements in the Mutational History of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cell 177: 1842–1857 e1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz ML, Papathanasiou S, Doerfler PA, Blaine LJ, Yao Y, Zhang C-Z, Weiss MJ, Pellman D. 2020. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. bioRxiv: 2020.2007.2013.200998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Ortiz AM, Panier S, Sarek G, Vannier JB, Patel H, Campbell PJ, Boulton SJ. 2018. A Distinct Class of Genome Rearrangements Driven by Heterologous Recombination. Mol Cell 69: 292–305 e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Roberts ND, Wala JA, Shapira O, Schumacher SE, Kumar K, Khurana E, Waszak S, Korbel JO, Haber JE. 2020. Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Nature 578: 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddiard K, Ruis B, Kan Y, Cleal K, Ashelford KE, Hendrickson EA, Baird DM. 2019. DNA Ligase 1 is an essential mediator of sister chromatid telomere fusions in G2 cell cycle phase. Nucleic Acids Research 47: 2402–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddiard K, Ruis B, Takasugi T, Harvey A, Ashelford KE, Hendrickson EA, Baird DM. 2016. Sister chromatid telomere fusions, but not NHEJ-mediated inter-chromosomal telomere fusions, occur independently of DNA ligases 3 and 4. Genome Research 26: 588–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Yang L, Tanasa B, Hutt K, Ju BG, Ohgi K, Zhang J, Rose DW, Fu XD, Glass CK et al. 2009. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell 139: 1069–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Erez A, Nagamani SCS, Dhar SU, Kołodziejska KE, Dharmadhikari AV, Cooper ML, Wiszniewska J, Zhang F, Withers MA. 2011. Chromosome catastrophes involve replication mechanisms generating complex genomic rearrangements. Cell 146: 889–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Kwon M, Mannino M, Yang N, Renda F, Khodjakov A, Pellman D. 2018. Nuclear envelope assembly defects link mitotic errors to chromothripsis. Nature 561: 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax ME, Folkes LK, O’Neill P. 2013. Biological Consequences of Radiation-induced DNA Damage: Relevance to Radiotherapy. Clinical Oncology 25: 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Brunner SF, Shoshani O, Kim DH, Lan W, Pyntikova T, Flanagan AM, Behjati S, Page DC, Campbell PJ. 2019. Chromosome segregation errors generate a diverse spectrum of simple and complex genomic rearrangements. Nature Genetics 51: 705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Cleveland DW. 2017. Rebuilding Chromosomes After Catastrophe: Emerging Mechanisms of Chromothripsis. Trends Cell Biol 27: 917–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Teitz LS, Kim DH, Shoshani O, Skaletsky H, Fachinetti D, Page DC, Cleveland DW. 2017. Selective Y centromere inactivation triggers chromosome shattering in micronuclei and repair by non-homologous end joining. Nat Cell Biol 19: 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejowski J, Chatzipli A, Dananberg A, Chu K, Toufektchan E, Klimczak LJ, Gordenin DA, Campbell PJ, de Lange T. 2020. APOBEC3-dependent kataegis and TREX1-driven chromothripsis during telomere crisis. Nat Genet 52: 884–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejowski J, Li Y, Bosco N, Campbell PJ, de Lange T. 2015. Chromothripsis and kataegis induced by telomere crisis. Cell 163: 1641–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani RS, Amin MA, Li X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Veeneman BA, Wang L, Ghosh A, Aslam A, Ramanand SG, Rabquer BJ et al. 2016. Inflammation-Induced Oxidative Stress Mediates Gene Fusion Formation in Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep 17: 2620–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardin BR, Drainas AP, Waszak SM, Weischenfeldt J, Isokane M, Stütz AM, Raeder B, Efthymiopoulos T, Buccitelli C, Segura‐Wang M. 2015. A cell‐based model system links chromothripsis with hyperploidy. Molecular Systems Biology 11: 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Gomez PA, Gong F, Nair N, Miller KM, Lazzerini-Denchi E, Sfeir A. 2015. Mammalian polymerase theta promotes alternative NHEJ and suppresses recombination. Nature 518: 254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayle R, Campbell IM, Beck CR, Yu Y, Wilson M, Shaw CA, Bjergbaek L, Lupski JR, Ira G. 2015. Mus81 and converging forks limit the mutagenicity of replication fork breakage. Science 349: 742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B 1941. The Stability of Broken Ends of Chromosomes in Zea Mays. Genetics 26: 234–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B 1942. The fusion of broken ends of chromosomes following nuclear fusion. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences of the United States of America 28: 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier B, Cooke SL, Weiss J, Bailly AP, Alexandrov LB, Marshall J, Raine K, Maddison M, Anderson E, Stratton MR et al. 2014. C. elegans whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational signatures related to carcinogens and DNA repair deficiency. Genome Res 24: 1624–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menghi F, Barthel FP, Yadav V, Tang M, Ji B, Tang Z, Carter GW, Ruan Y, Scully R, Verhaak RGW et al. 2018. The Tandem Duplicator Phenotype Is a Prevalent Genome-Wide Cancer Configuration Driven by Distinct Gene Mutations. Cancer Cell 34: 197–210 e195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens F, Johansson B, Fioretos T, Mitelman F. 2015. The emerging complexity of gene fusions in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 15: 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TJ, Turajlic S, Rowan A, Nicol D, Farmery JHR, O’Brien T, Martincorena I, Tarpey P, Angelopoulos N, Yates LR et al. 2018. Timing the Landmark Events in the Evolution of Clear Cell Renal Cell Cancer: TRACERx Renal. Cell 173: 611–623 e617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mladenov E, Saha J, Iliakis G. 2018. Processing-Challenges Generated by Clusters of DNA Double-Strand Breaks Underpin Increased Effectiveness of High-LET Radiation and Chromothripsis. in Chromosome Translocation (ed. Zhang Y), pp. 149–168. Springer Singapore, Singapore. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr L, Toufektchan E, von Morgen P, Chu K, Kapoor A, Maciejowski J. 2021. ER-directed TREX1 limits cGAS activation at micronuclei. Mol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita M, Muramatsu T, Suto Y, Hirai M, Konishi T, Hayashi S, Shigemizu D, Tsunoda T, Moriyama K, Inazawa J. 2016. Chromothripsis-like chromosomal rearrangements induced by ionizing radiation using proton microbeam irradiation system. Oncotarget 7: 10182–10192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen UH, Bendixen C, Sunjevaric I, Rothstein R. 1996. DNA strand annealing is promoted by the yeast Rad52 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 10729–10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim V, Rosselli F. 2009. The FANC pathway and BLM collaborate during mitosis to prevent micro-nucleation and chromosome abnormalities. Nature Cell Biology 11: 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson DA, Gini B, Mottahedeh J, Visnyei K, Koga T, Gomez G, Eskin A, Hwang K, Wang J, Masui K et al. 2014. Targeted therapy resistance mediated by dynamic regulation of extrachromosomal mutant EGFR DNA. Science 343: 72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings LA et al. 2012. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 149: 979–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J, Ramakrishna M, Glodzik D, Zou X, Martincorena I, Alexandrov LB, Martin S, Wedge DC et al. 2016. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534: 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notta F, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Lemire M, Li Y, Wilson GW, Connor AA, Denroche RE, Liang S-B, Brown AM, Kim JC. 2016. A renewed model of pancreatic cancer evolution based on genomic rearrangement patterns. Nature 538: 378–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell PC. 1962. The minute chromosome (Phl) in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blut 8: 65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampalona J, Roscioli E, Silkworth WT, Bowden B, Genescà A, Tusell L, Cimini D. 2016. Chromosome bridges maintain kinetochore-microtubule attachment throughout mitosis and rarely break during anaphase. PloS One 11: e0147420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannunzio NR, Watanabe G, Lieber MR. 2018. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293: 10512–10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza A, Wright WD, Heyer W-D. 2017. Multi-invasions Are Recombination Byproducts that Induce Chromosomal Rearrangements. Cell 170: 760–773.e715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R, Zheng H, He H, Luo Y, Multani A, Carpenter PB, Chang S. 2010. The function of classical and alternative non‐homologous end‐joining pathways in the fusion of dysfunctional telomeres. The EMBO Journal 29: 2598–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnaparkhe M, Wong JKL, Wei PC, Hlevnjak M, Kolb T, Simovic M, Haag D, Paul Y, Devens F, Northcott P et al. 2018. Defective DNA damage repair leads to frequent catastrophic genomic events in murine and human tumors. Nat Commun 9: 4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch T, Jones DT, Zapatka M, Stutz AM, Zichner T, Weischenfeldt J, Jager N, Remke M, Shih D, Northcott PA et al. 2012. Genome sequencing of pediatric medulloblastoma links catastrophic DNA rearrangements with TP53 mutations. Cell 148: 59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheinbay E, Nielsen MM, Abascal F, Wala JA, Shapira O, Tiao G, Hornshoj H, Hess JM, Juul RI, Lin Z et al. 2020. Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes. Nature 578: 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C, Jasin M. 2000. Frequent chromosomal translocations induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 405: 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JD. 1973. A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature 243: 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini N, Ramakrishnan S, Elango R, Ayyar S, Zhang Y, Deem A, Ira G, Haber JE, Lobachev KS, Malkova A. 2013. Migrating bubble during break-induced replication drives conservative DNA synthesis. Nature 502: 389–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakofsky Cynthia J, Roberts Steven A, Malc E, Mieczkowski Piotr A, Resnick Michael A, Gordenin Dmitry A, Malkova A. 2014. Break-Induced Replication Is a Source of Mutation Clusters Underlying Kataegis. Cell Reports 7: 1640–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JT, Freeman TF, Xu Y, Golloshi R, Stallard MA, Hill AM, San Martin R, Balajee AS, McCord RP. 2020. Radiation-induced DNA damage and repair effects on 3D genome organization. Nat Commun 11: 6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S, Richardson A, Iyer DR, M’Saad O, Zasadil L, Knouse KA, Wong YL, Rhind N, Desai A, Amon A. 2017. Chromosome Mis-segregation Generates Cell-Cycle-Arrested Cells with Complex Karyotypes that Are Eliminated by the Immune System. Dev Cell 41: 638–651 e635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshani O, Brunner SF, Yaeger R, Ly P, Nechemia-Arbely Y, Kim DH, Fang R, Castillon GA, Yu M, Li JSZ et al. 2020. Chromothripsis drives the evolution of gene amplification in cancer. Nature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek D, Brunet E, Wong SY-W, Katyal S, Gao Y, McKinnon PJ, Lou J, Zhang L, Li J, Rebar EJ et al. 2011. DNA Ligase III Promotes Alternative Nonhomologous End-Joining during Chromosomal Translocation Formation. PLOS Genetics 7: e1002080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Lam AF, Symington LS. 2009. Aberrant Double-Strand Break Repair Resulting in Half Crossovers in Mutants Defective for Rad51 or the DNA Polymerase δ Complex. Molecular and Cellular Biology 29: 1432–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Llorente B, Symington LS. 2007. Template switching during break-induced replication. Nature 447: 102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriou SK, Kamileri I, Lugli N, Evangelou K, Da-Re C, Huber F, Padayachy L, Tardy S, Nicati NL, Barriot S et al. 2016. Mammalian RAD52 Functions in Break-Induced Replication Repair of Collapsed DNA Replication Forks. Mol Cell 64: 1127–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M, Garcia-Santisteban I, Krenning L, Medema RH, Raaijmakers JA. 2018. Chromosomes trapped in micronuclei are liable to segregation errors. J Cell Sci 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M, Raaijmakers JA, Bakker B, Spierings DCJ, Lansdorp PM, Foijer F, Medema RH. 2017. p53 Prohibits Propagation of Chromosome Segregation Errors that Produce Structural Aneuploidies. Cell Rep 19: 2423–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark JM, Pierce AJ, Oh J, Pastink A, Jasin M. 2004. Genetic steps of mammalian homologous repair with distinct mutagenic consequences. Mol Cell Biol 24: 9305–9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA. 2011. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 144: 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudmant PH, Rausch T, Gardner EJ, Handsaker RE, Abyzov A, Huddleston J, Zhang Y, Ye K, Jun G, Fritz MH et al. 2015. An integrated map of structural variation in 2,504 human genomes. Nature 526: 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Ojima M, Kodama S, Watanabe M. 2003. Radiation-induced DNA damage and delayed induced genomic instability. Oncogene 22: 6988–6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington L, Gautier J. 2011. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annual Review of Genetics 45: 247–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, Compton DA. 2010. Proliferation of aneuploid human cells is limited by a p53-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol 188: 369–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, Compton DA. 2011. Chromosome missegregation in human cells arises through specific types of kinetochore-microtubule attachment errors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 17974–17978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Jones OA, Chan K-L. 2018. 53BP1 can limit sister-chromatid rupture and rearrangements driven by a distinct ultrafine DNA bridging-breakage process. Nature Communications 9: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, Varambally S, Cao X, Tchinda J, Kuefer R et al. 2005. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 310: 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs A, Nussenzweig A. 2017. Endogenous DNA Damage as a Source of Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cell 168: 644–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KM, Deshpande V, Beyter D, Koga T, Rusert J, Lee C, Li B, Arden K, Ren B, Nathanson DA et al. 2017. Extrachromosomal oncogene amplification drives tumour evolution and genetic heterogeneity. Nature 543: 122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbreit NT, Zhang C-Z, Lynch LD, Blaine LJ, Cheng AM, Tourdot R, Sun L, Almubarak HF, Judge K, Mitchell TJ. 2020. Mechanisms generating cancer genome complexity from a single cell division error. Science 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaze MB, Pellicioli A, Lee SE, Ira G, Liberi G, Arbel-Eden A, Foiani M, Haber JE. 2002. Recovery from Checkpoint-Mediated Arrest after Repair of a Double-Strand Break Requires Srs2 Helicase. Molecular Cell 10: 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vietri M, Schultz SW, Bellanger A, Jones CM, Petersen LI, Raiborg C, Skarpen E, Pedurupillay CRJ, Kjos I, Kip E. 2020. Unrestrained ESCRT-III drives micronuclear catastrophe and chromosome fragmentation. Nature Cell Biology: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina N, Wong JK, Hübschmann D, Hlevnjak M, Uhrig S, Heilig CE, Horak P, Kreutzfeldt S, Mock A, Stenzinger A. 2020. The landscape of chromothripsis across adult cancer types. Nature Communications 11: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrtis KB, Dewar JM, Chistol G, Wu RA, Graham TGW, Walter JC. 2021. Single-strand DNA breaks cause replisome disassembly. Mol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Rosidi B, Perrault R, Wang M, Zhang L, Windhofer F, Iliakis G. 2005. DNA ligase III as a candidate component of backup pathways of nonhomologous end joining. Cancer Res 65: 4020–4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weckselblatt B, Rudd MK. 2015. Human structural variation: mechanisms of chromosome rearrangements. Trends in Genetics 31: 587–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis NA, Frock RL, Menghi F, Duffey EE, Panday A, Camacho V, Hasty EP, Liu ET, Alt FW, Scully R. 2017. Mechanism of tandem duplication formation in BRCA1-mutant cells. Nature 551: 590–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Luquette LJ, Gehlenborg N, Xi R, Haseley PS, Hsieh CH, Zhang C, Ren X, Protopopov A, Chin L et al. 2013. Diverse mechanisms of somatic structural variations in human cancer genomes. Cell 153: 919–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Lescale C, Babin L, Bedora-Faure M, Lenden-Hasse H, Baron L, Demangel C, Yelamos J, Brunet E, Deriano L. 2020. Repair of G1 induced DNA double-strand breaks in S-G2/M by alternative NHEJ. Nat Commun 11: 5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhsng CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH et al. 2013. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet 45: 1134–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CZ, Spektor A, Cornils H, Francis JM, Jackson EK, Liu S, Meyerson M, Pellman D. 2015. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature 522: 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Khajavi M, Connolly AM, Towne CF, Batish SD, Lupski JR. 2009. The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nature Genetics 41: 849–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen F, Fonseca NA, He Y, Fujita M, Nakagawa H, Zhang Z, Brazma A, Group PTW, Group PSVW et al. 2020. High-coverage whole-genome analysis of 1220 cancers reveals hundreds of genes deregulated by rearrangement-mediated cis-regulatory alterations. Nat Commun 11: 736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Jasin M. 2011. An essential role for CtIP in chromosomal translocation formation through an alternative end-joining pathway. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 18: 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]