Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Natural vegetation, or greenness, is thought to improve health through its ability to buffer and reduce harmful environmental exposures as well as relieve stress, promote physical activity, restore attention, and increase social cohesion. In concert, these effects could help mitigate the detrimental effects of air pollution on reproductive aging in women.

METHODS:

Our analysis included 565 women attending the Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center (2004–2014) who had a measured antral follicle count (AFC), a marker of ovarian reserve. We calculated peak residential greenness in the year prior to AFC using 250m2 normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) from the Terra and Aqua satellites operated by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Validated spatiotemporal models estimated daily residential exposure to particulate matter <2.5μm (PM2.5) for the 3 months prior to AFC. Poisson regression models with robust standard errors were used to estimate the association between peak greenness, average PM2.5 exposure, and AFC adjusted for age, BMI, smoking status, education, year, and season.

RESULTS:

Women in our study had a mean age of 35.2 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 4.3 years (min: 20 years, max: 45 years). The peak residential NDVI ranged from 0.07 to 0.92 with a SD of 0.18. There was no statistically significant association between peak residential greenness and AFC; however, higher exposure to PM2.5 was associated with lower AFC (−6.2% per 2 μg/m3 [1 SD increase] 95% CI −11.8, −0.3). There was a significant interaction between exposure to PM2.5 and peak greenness on AFC (P-interaction: 0.03). Among women with an average PM2.5 exposure of 7 μg/m3, a SD increase in residential peak greenness was associated with a 5.6% (95% CI −0.4, 12.0) higher AFC. Conversely, among women with a PM2.5 exposure of 12 μg/m3, a SD increase in residential peak greenness was associated with a 5.8% (95% CI −13.1, 2.1) lower AFC.

CONCLUSIONS:

Residing in an area with high levels of greenness may slow reproductive aging in women only when exposure to PM2.5 is low.

Keywords: greenness, air pollution, built environment, fertility, ovarian aging

1. INTRODUCTION

The association between greenness, a measure of vegetation surrounding a residence or occupational setting, and health is a growing area of scientific interest.1 Over the past 10 years, evidence has mounted demonstrating a potentially beneficial effect of exposure to residential greenness on chronic diseases such as type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome,2–5 as well as pregnancy and birth outcomes.4,6–10 The proposed mechanisms underlying the positive health effects of greenness include dampening the negative impacts of other environmental exposures (such as heat, noise, and air pollution), providing relief for mental and physiologic stress, and promoting physical and social activities.11 Although these pathways are also implicated in the etiology of reproductive aging,12–14 less research has focused on this outcome. By 2050 an estimated 66% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas,15 with limited access to natural vegetation. During this same time period, an increasing number of women are expected to delay pregnancy until their later reproductive years,16 when a sharp decline in ovarian function occurs. Therefore, understanding environmental factors, such as greenness, that may accelerate or slow ovarian aging is becoming increasingly relevant.

Ovarian reserve is a marker of reproductive aging and fertility in women17 and can be measured either directly via an antral follicle scan or indirectly via serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) or serum follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) levels.17,18 Previous epidemiological studies have linked a variety of environmental containments to reduced ovarian reserve including higher exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals such as bisphenol A, parabens, and phthalates19 and air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter (PM2.5).20,21 In addition, a small cross-sectional study (n=67) from Iran found a positive association between the amount of greenness surrounding a woman’s home and ovarian reserve;22 however, given the low levels of greenness (and high levels of particulate matter air pollution) observed in this study, it is unclear how generalizable these results are to high-income countries.22

Therefore, we sought to further evaluate the association between greenness and ovarian reserve using a cohort of women in the United States where antral follicle count (AFC), a direct marker of ovarian reserve, was measured. Given the complicated interaction between greenspace and air pollution, we were particularly interested in exploring potential effect modification by PM2.5 exposure,18 as this may shed insight into the potential mechanisms of action and the best ways to maximize any potential health benefits of residential greenness.

2. MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1. Study Population.

Participants were part of the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study,23 a prospective cohort designed to evaluate how the environment affects fertility.23 Women, 18 to 45 years old, attending the Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center for infertility evaluation and treatment were invited to enroll in the study. Upon entry, participants completed a detailed questionnaire concerning their demographics, medical history, environmental exposures, diet, lifestyle, and reproductive health. Physical activity was self-reported on this questionnaire using a validated assessment24 and was summarized as total hours per week. Height and weight were measured by a research assistant at study entry and used to calculate BMI (kg/m2). Participants provided their residential address for reimbursement purposes which were then used for geospatial analysis. To be eligible for this analysis, women had to have undergone an antral follicle scan on or before December 2014, when greenness data was available (n=757). From there, we excluded women with incomplete scans, women on Lupron (a Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist), women with polycystic ovary syndrome, or women missing air pollution exposure information (Figure 1). Most of the women underwent one antral follicle scan, thus we also excluded repeated scans from women. The institutional review boards at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health approved this study. Participants provided written informed consent.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of study sample and exclusion criteria

2.2. Ovarian Reserve.

We used AFC as a maker of ovarian reserve. AFC was measured by a trained reproductive endocrinologist using transvaginal ultrasonography. Scans took place on the 3rd day of an unstimulated menstrual cycle or the 3rd day following a progesterone withdrawal bleed. Only follicles above 2mm in diameter were included in the count. We examined AFC as continuous outcome but to reduce the influence of very high counts, we truncated AFC at 30 (12 women, 2.1% of population).

2.3. Greenness exposure.

We geocoded the women’s residential address information using ArcGIS StreetMap USA (ESRI; Redlands, CA), a nationwide street network for map visualization, geocoding, and routing. Match scores (on a scale of 0–100) were reviewed to determine the reason for scores <100. In all of the women with match scores below 90%, we manually checked and confirmed their address. Most often, lower scores were the result of slight misspellings of street names or incorrect street type abbreviations. To assess residential greenness, we used remote sensing data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites operated by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) values, the most widely used satellite-derived indicator of greenness, were derived from these data at a 250 m2 resolution.1 The NDVI quantifies vegetation by measuring the difference between near-infrared (which vegetation strongly reflects) and red light (which vegetation absorbs). NDIV measures greenness on the ground ranging between −1 and 1, with 1 representing maximal vegetation, 0 representing barren areas of rock, sand, or snow, and −1 indicating bodies of water. We chose 250 m2 resolution to capture local and accessible residential greenness. We selected a single buffer closest to the residence because a prior study observed the strongest relationship between greenness and ovarian reserve hormones at the closest buffer (100 m around the geocoded residential address).22 Since NDVI reaches its maximum and highest level of geographic variation during the height of the summer, we used the greenness estimate from the most recent July prior to the woman’s antral follicle scan date as our main exposure of interest and we referred to this exposure as peak greenness. Using a time-varying NDVI dataset containing measurements from January, April, July, and October of each year, we also calculated a woman’s average greenness exposure in the year prior to scan.

2.4. Air pollution exposure.

Using the participant’s residential address, we estimated daily PM2.5 exposure starting 3 months prior to the date of AFC scan. A 3-month window was selected given the antral follicle development window is approximately 2 to 4 months.18 To estimate daily PM2.5, we used a validated hybrid model of satellite and land use data25 with a 1 km2 spatial resolution. These models used satellite-derived aerosol optical depth data, Multi-Angle Implementation of Atmospheric Correction algorithms from MODIS, land use data (e.g. measures of population density, elevation, traffic, percentages of land use, normalized difference vegetation index, and point and source pollutant emissions) from the US Geological Survey National Land Cover dataset, as well as meteorological conditions (e.g. air temperature, wind speed, daily visibility, sea land pressure, and relative humidity) to estimate ground-level exposure. We then averaged the daily values for the 3-month window prior to the participant’s scan date. Based on our previous work showing that PM2.5 had a negative, linear association with AFC in this population,21 we modelled this variable as a continuous variable per standard deviation (SD) increase (approximately 2 μg/m3).

2.5. Covariates.

We selected covariates a priori based on biological relevance. Covariates included age at scan (continuous), body mass index (continuous), smoking status (never vs. ever smoked), education (less than a college degree, college degree, vs. graduate/advanced degree), year of the scan (continuous) and season (Jan-Mar, Apr-Jun, Jul-Sept, vs. Oct-Dec). Because air pollution exposure is often negatively correlated with greenness, average PM2.5 exposure was evaluated as both a confounder and effect modifier of the relationship between residential greenness and AFC.

2.6. Statistical Analysis.

We used basic descriptive statistics, frequency distributions and means and standard deviations (SD), by quartiles of peak greenness, to describe the sample. We were concerned with potential overdispersion in AFC. We tested for overdispersion by fitting a negative binomial distribution and testing to see if the negative binomial dispersion parameter was equal to zero. Our test indicated overdispersion in AFC. To account for overdispersion, we used unadjusted and adjusted Poisson regression models with robust standard errors to assess the association between peak greenness and AFC. Non-linearity was assessed using restricted cubic splines. A likelihood ratio test was used to compare the model with the linear term to the model with the linear and the cubic spline terms.26 We examined effect modification (e.g. multiplicative interaction) by average PM2.5 exposure on the relationship between peak greenness and AFC by including a cross-product term in the adjusted models. To visualize the interaction effects, we used a contour plot and a slice plot. We also provide the percent change in mean AFC for a one SD increase in peak greenness at the 10th and 90th percentile of PM2.5 exposure (7 μg/m3 and 12 μg/m3 respectively).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results. First, we included physical activity as a confounder in the adjusted model because physical activity could be used as a proxy for time outdoors which may influence exposure to greenness and PM2.5. Physical activity was not included in the main analysis because, while the relationship between physical activity and exposure to greenness is clear, we were concerned that physical activity might represent more of a mediator or pathway through which greenness affects health rather than a true confounder. We also examined effect modification by physical activity (stratified by the median: <4.5 vs. ≥4.5 hours/week). Next, we evaluated the associations between the average greenness exposure in the year prior to the scan (instead of peak greenness prior to scan) and AFC. We also examined effect modification by age (<35 vs. ≥35 years) and infertility diagnosis (female, male, vs. unexplained) as these are two of the strongest predictors of AFC. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

After applying exclusion criteria, the final analytical sample included 565 women with complete data on greenness and AFC (Figure 1). Peak NDVI ranged from 0.07 to 0.92 (Table 1) with a mean of 0.59. Participant age varied by quartile of peak greenness with an average age of 36.0 years among women in the highest quartile of greenness compared to 34.8 years among women in the lowest quartile of greenness. Average PM2.5 exposure also differed by greenness quartile. The highest average PM2.5 exposure (9.4 μg/m3) was among women in the second quartile of greenness whereas women in the first quartile had the lowest exposure (8.9 μg/m3); however, the Spearman correlation between exposures to peak greenness and average PM2.5 indicated little linear association (ρ=−0.01). Greenness also varied slightly according to year of the antral follicle scan (ρ=−0.18). All other demographic and reproductive characteristics were similar across quartiles of peak greenness.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographic and reproductive characteristics by quartiles of residential peak NDVI greenness prior to AFC among 565 women in the EARTH Study, Massachusetts, United States.

| Quartile (Range) | Total Cohort | Peak NDVI Greenness Prior to AFC | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Number of Women | (0.07, 0.92) 565 | (0.07, 0.47) 141 | (0.47, 0.59) 141 | (0.59, 0.75) 142 | (0.75, 0.92) 141 | |

|

| ||||||

| Demographics a | ||||||

| Age, years | 35.2 (4.3) | 34.8 (4.1) | 35.1 (4.4) | 34.7 (4.2) | 36.0 (4.3) | 0.05 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.10 | |||||

| White | 477 (84.6) | 115 (81.6) | 120 (85.1) | 123 (86.6) | 119 (84.4) | |

| Black | 17 (3.0) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 6 (4.2) | 5 (3.6) | |

| Asian | 47 (8.3) | 21 (14.9) | 9 (6.4) | 6 (4.2) | 11 (7.8) | |

| Other | 23 (4.1) | 3 (2.1) | 8 (5.7) | 7 (4.9) | 5 (3.6) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.5 (4.6) | 24.0 (4.3) | 25.0 (5.1) | 24.6 (4.5) | 24.3 (4.3) | 0.36 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.20 | |||||

| Never smoked | 416 (73.6) | 106 (75.2) | 99 (70.2) | 99 (69.7) | 112 (79.4) | |

| Ever smoked | 149 (26.4) | 35 (24.8) | 42 (29.8) | 43 (30.3) | 29 (20.6) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.41 | |||||

| < College | 43 (7.6) | 10 (7.1) | 14 (9.9) | 12 (8.5) | 7 (5.0) | |

| College graduate | 241 (42.7) | 52 (36.9) | 60 (42.6) | 61 (43.0) | 68 (48.2) | |

| Graduate degree | 281 (49.7) | 79 (56.0) | 67 (47.5) | 69 (48.6) | 66 (46.8) | |

| Total physical activity (hr/week) | 6.5 (8.2) | 7.8 (11.6) | 5.9 (6.5) | 6.2 (7.5) | 6.1 (6.1) | 0.57 |

| Reproductive characteristics | ||||||

| History of being pregnant, n (%) | 250 (44.3) | 67 (47.5) | 57 (40.4) | 68 (47.9) | 58 (41.1) | 0.43 |

| Previous infertility exam, n (%) | 455 (80.5) | 115 (81.6) | 109 (77.3) | 114 (80.3) | 117 (83.0) | 0.66 |

| Previous infertility treatment, n (%) | 294 (52.0) | 66 (46.8) | 70 (49.7) | 79 (55.6) | 79 (56.0) | 0.32 |

| Initial infertility diagnosis, n (%) | 0.74 | |||||

| Male factor | 153 (27.1) | 40 (28.4) | 35 (24.8) | 39 (27.5) | 39 (27.7) | |

| Female factor | 187 (33.1) | 44 (31.2) | 49 (34.8) | 49 (34.5) | 45 (31.9) | |

| DOR | 62 (11.0) | 10 (7.1) | 16 (11.4) | 18 (12.7) | 18 (12.8) | |

| Endometriosis | 35 (6.2) | 9 (6.4) | 6 (4.3) | 9 (6.3) | 11 (7.8) | |

| Ovulation Disorders | 50 (8.9) | 15 (10.6) | 14 (9.9) | 12 (8.5) | 9 (6.4) | |

| Tubal | 32 (5.7) | 8 (5.7) | 9 (6.4) | 9 (6.3) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Uterine | 8 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Unexplained | 222 (39.3) | 57 (40.4) | 57 (40.4) | 53 (37.3) | 55 (39.0) | |

| Year of AFC | 2009.9 (2.5) | 2010.5 (2.4) | 2009.9 (2.3) | 2010.0 (2.6) | 2009.2 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Season of AFC, n (%) | 0.38 | |||||

| Jan-Mar | 159 (28.1) | 34 (24.1) | 40 (28.4) | 43 (30.3) | 42 (29.8) | |

| Apr-Jun | 130 (23.0) | 39 (27.7) | 34 (24.1) | 22 (15.5) | 35 (24.8) | |

| Jul-Sept | 112 (19.8) | 27 (19.2) | 23 (16.3) | 32 (22.5) | 30 (21.3) | |

| Oct-Dec | 164 (29.0) | 41 (25.0) | 44 (26.8) | 45 (27.4) | 34 (20.7) | |

| Average PM2.5 Exposure, μ/m3 | 9.2 (1.8) | 8.9 (1.7) | 9.4 (1.8) | 9.2 (2.0) | 9.1 (1.9) | 0.06 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or number of women (%); Abbreviations: AFC, antral follicle count; DOR, diminished ovarian reserve;

Numbers may not add up to the total due to missing values (i.e. 3 women missing infertility diagnosis).

We did not observe evidence of a nonlinear relationship between peak greenness and AFC (P for non-linearity: 0.26). After multivariable adjustment, a one SD increase in peak greenness was associated with a 1.1% (95% CI −3.3, 5.7) higher AFC; however, this association was not statistically significant (Table 2). In contrast, a 2 μg/m3 increase in average PM2.5 exposure was associated with a 6.2% (95% CI −11.8, −0.3) lower AFC.

Table 2.

Association between residential peak NDVI greenness and antral follicle counts (AFC) among 565 women in the EARTH Study.

| Unadjusted % Change in AFC | Adjusted % Change in AFCa | |

|---|---|---|

| Per SD increase in Peak Greenness | −0.7 (−5.1, 3.9) | 1.1 (−3.3, 5.7) |

| Per 2 μg/m 3 increase in PM 2.5 | −7.3 (−11.2, −3.3) | −6.2 (−11.8, −0.3) |

All regression models were run using a Poisson distribution and robust standard errors.

Adjusted models accounted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever, never), education (<college, college, graduate school), year of AFC (continuous), season of AFC (Jan-Mar, Apr-Jun, Jul-Sept, Oct-Dec), and average PM2.5 exposure in 3 months prior to AFC (continuous).

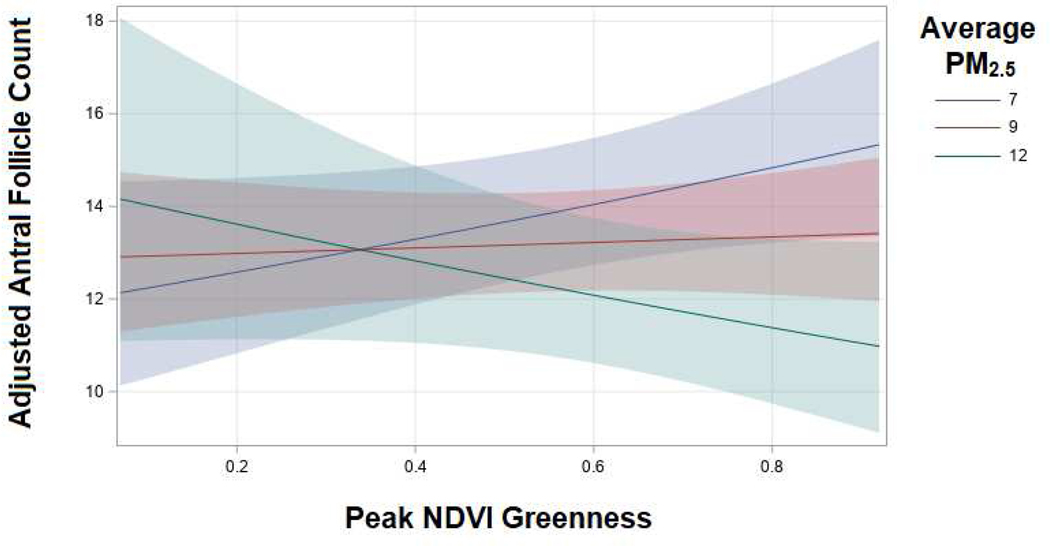

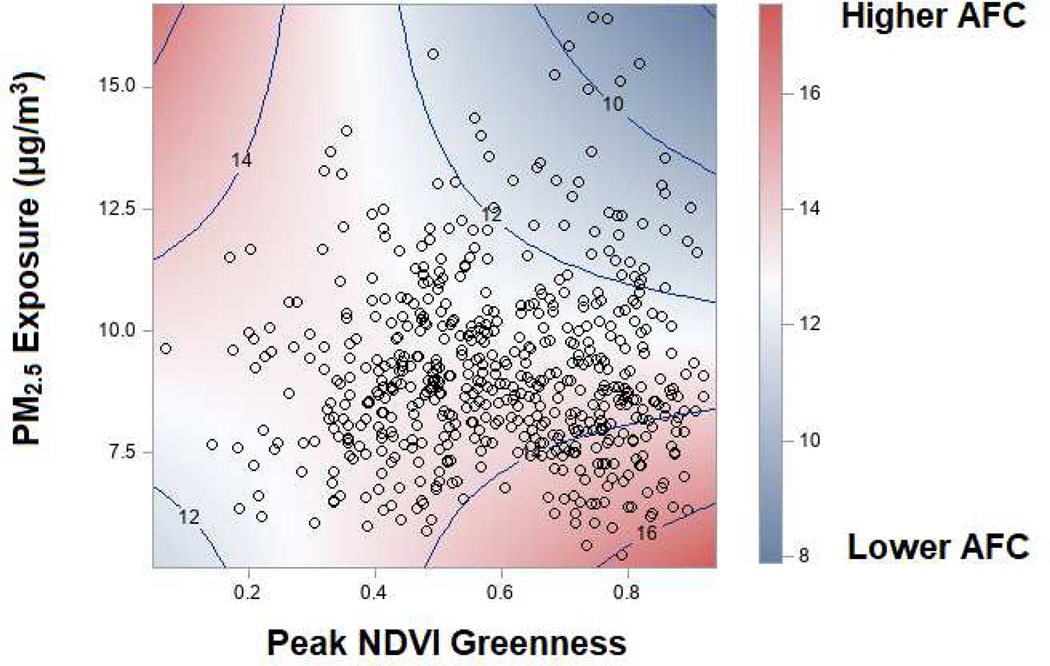

When we used a model with a cross-product term between average PM2.5 exposure and peak greenness, we found evidence of a statistically significant multiplicative interaction (P interaction: 0.03). Among women with an average PM2.5exposure of 7 μg/m3, a SD increase in peak greenness was associated with a 5.6% (95% CI −0.4, 12.0) higher AFC. Conversely, among women with an average PM2.5 exposure of 12 μg/m3, a SD increase in residential peak greenness was associated with a 5.8% (95% CI −13.1, 2.1) lower AFC (Figure 2). In general, women with high exposure to greenness and low exposure to PM2.5 tended to have the highest AFCs while women with high exposure to both greenness and PM2.5 had the lowest AFCs (Figure 3). There was a suggestion that women with low exposure to greenness and high exposure to PM2.5 also had higher AFCs although as indicated by the lack of dots in this corner of the contour plot, but this was based on very sparse data.

Figure 2.

Slice plot displaying the interaction between peak greenness and average PM2.5 exposures on adjusted mean AFC in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study, 2005–2014.

Average PM2.5 exposures of 7, 9, and 12 μg/m3 represent the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles in our population. The adjusted models account for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever, never), education (<college, college, graduate school), year of AFC (continuous), season of AFC (Jan-Mar, Apr-Jun, Jul-Sept, Oct-Dec), average PM2.5 exposure in 3 months prior to AFC (continuous), and a cross-product between peak NDVI exposure and average PM2.5 exposure.

Figure 3.

Contour and scatter plot displaying the interaction between PM2.5 and peak greenness exposures on adjusted mean AFCs in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study, 2005–2014.

Adjusted models account for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever, never), education (<college, college, graduate school), year of AFC (continuous), season of AFC (Jan-Mar, Apr-Jun, Jul-Sept, Oct-Dec), average PM2.5 exposure in 3 months prior to AFC (continuous), and a cross-product between peak NDVI exposure and average PM2.5 exposure.

The addition of self-reported physical activity as a covariate to the multivariable model did not change the associations between peak greenness and AFC or average PM2.5 exposure and AFC (Supplemental Table 1). We also found no evidence of effect modification physical activity (P interaction: 0.93). When we used average greenness exposure in the year prior to antral follicle scan as our primary exposure, we observed similar associations (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). This was likely due to the high correlation between peak and average greenness exposures (ρ=0.90). For example, among women with an average exposure of 7 μg/m3 PM2.5, a SD increase in average greenness exposure in the year prior was associated with a 5.2% (95% CI −2.5, 13.5) higher AFC. Conversely, among women with a PM2.5 exposure of 12 μg/m3 PM2.5, a SD increase in residential average greenness exposure in the year prior was associated with a 6.9% (95% CI −15.2, 2.2) lower AFC. We found no evidence effect modification by age (P interaction: 0.67) or infertility diagnosis (P interaction: 0.35) (Supplemental Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

We observed that higher amounts of greenness surrounding a woman’s home was associated with higher AFC, but only when exposure to PM2.5 was low (≤9 μg/m3). At high levels of PM2.5 exposure (≥12 μg/m3), there was a suggestion that the relationship was negative, although this was based on sparse data as few women in our study had high exposure to PM2.5 and low exposure to greenness.

Only one other study has examined greenness and particulate matter exposure in relation to markers of ovarian reserve. In this study, serum concentrations of FSH and AMH were used to quantify ovarian reserve among 67 women in Sabzevar, Iran.22 Women with higher levels of greenness in the 100 m buffer around their home had higher AMH levels. Moreover, higher annual exposure to PM2.5 was negatively associated with AMH. Both associations persisted after adjustment for age, BMI, education, menstrual cycle regularity, parity and smoking.22 FSH concentrations were unaffected by greenness and PM2.5 exposure. Our results are somewhat in line with these findings, given that both studies observed negative associations between PM2.5 exposure and ovarian reserve and beneficial associations between greenness and AFC (although ours was only among women with low exposure to PM2.5). However, differences between the two studies are worth noting. While the demographics of women were quite similar, their environmental exposures were drastically different. The median (IQR) exposure to greenspace and PM2.5 were 0.07 (0.01) and 42.2 (7.9) μg/m3 in the study by Abareshi et al. compared to 0.59 (0.29) and 8.9 (2.2) μg/m3 in our study. Therefore, the results are hard to directly compare since we had no women with similar environmental exposure profiles. Indirect evidence in support of our findings also comes from a prospective European study, which found that among 1955 premenopausal women at baseline, those with higher exposure to residential greenness during follow-up had an older age at menopause.27 While there is conflicting evidence on whether markers of ovarian reserve correlate with timing of reproductive senescence, our study provides one potential biological pathway through which greenness may decelerate reproductive aging.

Of note, neither of these past studies investigated the potential interaction between greenness and PM2.5 exposure despite biological plausibility. In support of our finding of an interaction, several other studies have observed a similar interaction between air pollution and greenness.28–31 For example, a recent prospective study from China found a beneficial association between residential greenness exposure and lower risk of gestational diabetes that was strongest among pregnant women with the lowest exposure to air pollution.28 In a case-crossover study, the detrimental effect of PM2.5 exposure on cardiovascular mortality progressively weakened with increasing exposure to NDVI in areas of lower socioeconomic status.29 Similarly, in a case-crossover study from Hong Kong, elevated greenness around the patient’s home significantly attenuated the association between PM2.5 exposure and increased risk of pneumonia mortality.30

Several pathways have been proposed to explain the positive associations observed between greenness and a variety of health outcomes including; (1) reducing harm, (2) restoring capacity, and (3) building capacity.11 In the reducing harm pathway, greenness exposure may potentially mitigates some of the negative influence of air pollution and other environmental/neighborhood exposures on ovarian reserve.20,21 Our results support this hypothesis given the differing responses we observed of greenness at various PM2.5 concentrations on mean AFC. For example, in our results, we observed that increasing greenness exposure was associated with higher AFCs but only when PM2.5 exposure was low. However, additional studies are needed to confirm the differential associations between levels of greenness exposure and PM2.5 exposure on ovarian reserve and other reproductive health outcomes. Restoring capacity, specifically through reduced stress, is another possible pathway mediating the association between greenness and ovarian reserve.11 In previous studies, higher exposure to greenness has been linked to lower psychosocial stress and lower psychosocial stress has been also linked to higher ovarian reserve.12–14,32–34 The third proposed pathway, building capacity though physical activity or social cohension,11 could influence ovarian reserve but evidence is currently lacking for this mechanism. In our study, physical activity neither confounded nor modified the association between greenness and AFC indicating that building capacity through physical activity did not play a major role in this relationship. Future studies are needed to confirm these proposed pathways.

The limitations of our study are worth noting. First, while our data came from a prospective cohort study, we only had a single measurement of AFC. Therefore, we were limited to evaluating the association between greenness and AFC across women rather than evaluating changes within a woman over time. We also only evaluated most recent peak greenness and past year average greenness exposure due to the lack of information on women’s residential history. Since women are born with all of their oocytes and this number declines over her lifetime, other time windows of exposure could be of interest. Ideally, future longitudinal studies with multiple assessments of greenness and ovarian reserve will be conducted to further this area of research. Second, while NDVI is the most commonly used metric to assign greenness exposure, it is a limited measure as it does not provide information on the specific types of vegetation such as trees, grass, or shrubs, nor does it describe the quality or accessibility of green spaces.35 Additional measures of greenness exposure could be utilized by future studies including the Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI2), Vegetation Continuous Field (VCF), or distance to major greenspaces. By using 250 m2 as the spatial resolution, we also assumed that pathways through which greenness influences AFC were limited to the women’s activity in the immediate area surrounding their residence. While findings from the sole prior study on this topic suggest that greenspace in more proximate residential buffers were better predictors of ovarian reserve, additional studies are needed to help determine the optimal scale.22 Next, because this is an observational study, there is the potential for residual confounding. Even though we included several important demographic, lifestyle, and reproductive characteristics in our adjusted models and performed several sensitivity analyses to address this concern, the potential still remains. Another potential source of bias is reserve causality but the likelihood of this bias occurring in this study is low for several reasons.

Specifically, the EARTH study was prospective in nature and women are unlikely to know their AFC prior to assessment, and even if it was known, there is limited evidence on environmental exposures influencing ovarian reserve so it is unlikely women would move to areas with high levels of greenness or low levels of PM2.5 to improve their AFC. Finally, due to the sole inclusion of subfertile women undergoing infertility treatment at a single fertility clinic in New England, who were predominantly of older reproductive age, White, and of high socioeconomic status, it may not be possible to generalize our findings to all women. While the homogeneity of our study participants does potentially restrict the generalizability, it also reduces the potential for confounding by these characteristics. Additionally, because the study participants were recruited from an infertility clinic, there is a concern for selection bias. However, for this type of bias to be present, selection into our cohort would have had to been associated with both exposure and outcome, which we do not think is likely. Previous work has demonstrated that AFCs are similar between women who do and do not report a history of infertility.36 There is also little reason to believe characteristics of a women’s residential built environment are strongly associated with her likelihood of seeking infertility treatment. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths including its prospective design, large size, validated air pollution models, an objective measure of greenness, and gold standard assessment of ovarian reserve.18 Additionally, we had the ability to account for a comprehensive set of reproductive and lifestyle factors as potential confounders and effect mediators.

5. CONCLUSION

Higher exposure to residential greenness was associated with higher ovarian reserve but only in the context of low PM2.5 exposure. These preliminary results suggest that residential greenness, a vital aspect of a woman’s built-environment, may play a small but potentially important role in dictating the pace of reproductive aging in women. If confirmed by other studies, these findings could provide valuable information to women when choosing where to live to enhance their reproductive health and to city planners on the best ways to design a built environment to maximize reproductive longevity in a rapidly urbanizing world. Additional longitudinal studies with repeated assessments of exposure and outcome are needed to confirm this association, further evaluate measures of greenspace quality and utilization, and clarify the mechanisms between greenness and health.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Overall, residential greenness was not associated with antral follicle count (AFC).

However, we observed a significant interaction between greenness and particulate matter (PM2.5) on AFC.

Among women with lower PM2.5 exposure, greenness was positively associated with AFC.

Among women with higher exposure to PM2.5, the association between greenness and AFC reversed.

Residential greenness may slow reproductive aging but only when PM2.5 exposure levels are low.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We would like to thank all members of the EARTH study team, specifically our research nurse Jennifer B. Ford, senior research staff Ramace Dadd, the physicians and staff at Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center, and all the EARTH study participants.

FUNDING: This work was supported by grants ES009718, ES022955, ES000002, and R00ES026648 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and R01HL150119 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This publication was also made possible by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA): RD-834798 and RD-83587201. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. EPA. Further, U.S. EPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AFC

antral follicle count

- AMH

anti-Müllerian hormone

- EARTH

Environment and Reproductive Health Study

- FSH

follicle stimulating hormone

- NDVI

normalized difference vegetation index

- PM2.5

fine particulate matter

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weier J, Herring D. Measuring Vegetation (NDVI & EVI). NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/MeasuringVegetation. Published 2000. Updated 08/03/2000. Accessed September 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Avellaneda-Gómez C, Dadvand P, et al. Association of residential air pollution, noise, and greenspace with initial ischemic stroke severity. Environ Res. 2019;179(Pt A):108725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Keijzer C, Basagaña X, Tonne C, et al. Long-term exposure to greenspace and metabolic syndrome: A Whitehall II study. Environ Pollut. 2019;255(Pt 2):113231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res. 2018;166:628–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong KC, Hart JE, James P. A Review of Epidemiologic Studies on Greenness and Health: Updated Literature Through 2017. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018;5(1):77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres Toda M, Miri M, Alonso L, Gómez-Roig MD, Foraster M, Dadvand P. Exposure to greenspace and birth weight in a middle-income country. Environ Res. 2020;189:109866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anabitarte A, Subiza-Pérez M, Ibarluzea J, et al. Testing the Multiple Pathways of Residential Greenness to Pregnancy Outcomes Model in a Sample of Pregnant Women in the Metropolitan Area of Donostia-San Sebastián. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seabrook JA, Smith A, Clark AF, Gilliland JA. Geospatial analyses of adverse birth outcomes in Southwestern Ontario: Examining the impact of environmental factors. Environ Res. 2019;172:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanini MJ, Domínguez C, Fernández-Oliva T, et al. Urban-Related Environmental Exposures during Pregnancy and Placental Development and Preeclampsia: a Review. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(10):81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banay RF, Bezold CP, James P, Hart JE, Laden F. Residential greenness: current perspectives on its impact on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. 2017;158:301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleil ME, Adler NE, Pasch LA, et al. Psychological stress and reproductive aging among pre-menopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2720–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bleil ME, Adler NE, Pasch LA, et al. Depressive symptomatology, psychological stress, and ovarian reserve: a role for psychological factors in ovarian aging? Menopause. 2012;19(11):1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiranmayee D, Praveena T, Himabindu Y, Sriharibabu M, Kavya K, Mahalakshmi M. The Effect of Moderate Physical Activity on Ovarian Reserve Markers in Reproductive Age Women Below and Above 30 Years. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10(1):44–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundaram R, Mumford SL, Buck Louis GM. Couples’ body composition and time-to-pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(3):662–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS data brief, no 232. In. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Defining ovarian reserve to better understand ovarian aging. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broekmans FJ, de Ziegler D, Howles CM, Gougeon A, Trew G, Olivennes F. The antral follicle count: practical recommendations for better standardization. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(3):1044–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karwacka A, Zamkowska D, Radwan M, Jurewicz J. Exposure to modern, widespread environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and their effect on the reproductive potential of women: an overview of current epidemiological evidence. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2019;22(1):2–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.La Marca A, Spaggiari G, Domenici D, et al. Elevated levels of nitrous dioxide are associated with lower AMH levels: a real-world analysis. Hum Reprod. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaskins AJ, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Fong KC, et al. Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and Ovarian Reserve Among Women from a Fertility Clinic. Epidemiology. 2019;30(4):486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abareshi F, Sharifi Z, Hekmatshoar R, et al. Association of exposure to air pollution and green space with ovarian reserve hormones levels. Environ Res. 2020;184:109342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messerlian C, Williams PL, Ford JB, et al. The Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study: A Prospective Preconception Cohort. Hum Reprod Open. 2018;2018(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(5):991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kloog I, Chudnovsky AA, Just AC, et al. A New Hybrid Spatio-Temporal Model For Estimating Daily Multi-Year PM(2.5) Concentrations Across Northeastern USA Using High Resolution Aerosol Optical Depth Data. Atmos Environ (1994). 2014;95:581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8(5):551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triebner K, Markevych I, Hustad S, et al. Residential surrounding greenspace and age at menopause: A 20-year European study (ECRHS). Environ Int. 2019;132:105088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qu Y, Yang B, Lin S, et al. Associations of greenness with gestational diabetes mellitus: The Guangdong Registry of Congenital Heart Disease (GRCHD) study. Environ Pollut. 2020;266(Pt 2):115127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yitshak-Sade M, James P, Kloog I, et al. Neighborhood Greenness Attenuates the Adverse Effect of PM(2.5) on Cardiovascular Mortality in Neighborhoods of Lower Socioeconomic Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun S, Sarkar C, Kumari S, et al. Air pollution associated respiratory mortality risk alleviated by residential greenness in the Chinese Elderly Health Service Cohort. Environ Res. 2020;183:109139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kioumourtzoglou MA, Schwartz J, James P, Dominici F, Zanobetti A. PM2.5 and Mortality in 207 US Cities: Modification by Temperature and City Characteristics. Epidemiology. 2016;27(2):221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, Agarwal A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: taking control of your fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu XY, Chen HH, Zhang N, et al. Effects of chronic unpredictable mild stress on ovarian reserve in female rats: Feasibility analysis of a rat model of premature ovarian failure. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(1):532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao L, Zhao F, Zhang Y, Wang W, Cao Q. Diminished ovarian reserve induced by chronic unpredictable stress in C57BL/6 mice. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rugel EJ, Henderson SB, Carpiano RM, Brauer M. Beyond the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): Developing a Natural Space Index for population-level health research. Environ Res. 2017;159:474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hvidman HW, Bentzen JG, Thuesen LL, et al. Infertile women below the age of 40 have similar anti-Müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count compared with women of the same age with no history of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.