Abstract

When one individual helps another, it benefits the recipient and may also gain a reputation for being cooperative. This may induce others to favour the helper in subsequent interactions, so investing in being seen to help others may be adaptive. The best-known mechanism for this is indirect reciprocity (IR), in which the profit comes from an observer who pays a cost to benefit the original helper. IR has attracted considerable theoretical and empirical interest, but it is not the only way in which cooperative reputations can bring benefits. Signalling theory proposes that paying a cost to benefit others is a strategic investment which benefits the signaller through changing receiver behaviour, in particular by being more likely to choose the signaller as a partner. This reputation-based partner choice can result in competitive helping whereby those who help are favoured as partners. These theories have been confused in the literature. We therefore set out the assumptions, the mechanisms and the predictions of each theory for how developing a cooperative reputation can be adaptive. The benefits of being seen to be cooperative may have been a major driver of sociality, especially in humans.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘The language of cooperation: reputation and honest signalling’.

Keywords: cooperation, partner choice, reputations, indirect reciprocity

1. Introduction

(a) The benefits of being seen to help

Helping involves one individual paying a cost to benefit a recipient. The costs can be repaid in terms of indirect fitness if the helper and recipient are genetically related [1], or they can be repaid directly, for example if the recipient reciprocates [2,3] or if the helper has a stake in the recipient's welfare [4–6]. Another way helpers might increase their direct fitness is by gaining a reputation for being helpful. A ‘good’ reputation may induce others to favour the helper in subsequent interactions. As a result, investing in a reputation for being seen to help others may be adaptive. This would potentially provide an explanation for helping others that goes beyond the domain of theories of kinship and direct reciprocity.

The best-known theory of how individuals might benefit from being seen to help others is indirect reciprocity (IR), in which paying a cost c to benefit another by b makes the helper more likely to receive a reciprocal benefit from an observer, and thereby to make a net gain when b > c [7]. A large number of theoretical models (e.g. [8–10] and some experiments (e.g. [11–14] have studied this possibility. Unfortunately, reputation building has tended to be equated with IR [12,15–18]. This focus has overshadowed the fact that IR is not the only theory for how individuals may get a return on a cooperative reputation. Different theories have been presented in the literature but have not always been clearly distinguished. We therefore set out the assumptions, mechanisms and predictions of the main theories for how developing a cooperative reputation can be adaptive. The psychological adaptations underlying reputation-based cooperation are considered elsewhere [19].

We use the term ‘reputation’ where individuals use information acquired by observation or gossip to learn about and predict how another individual will behave in the future. There is a spectrum of ways in which the term ‘reputation’ has been applied in understanding cooperative behaviour. This spectrum can be seen in figure 1 where we classify routes to cooperation using reputations. In the simplest sense, ‘reputation’ can be used to describe the observation of a partner's behaviour. However, we prefer to follow typical practice and reserve the term for where third-party observation and/or gossip comes into play. As such, we consider reputations to be more than simply a record of an individual's behaviour that could have been gained by a partner in a dyadic relationship. This distinguishes ‘reputation-based behaviour’ from responses found within directly reciprocating partnerships, mutualisms or among kin. We therefore focus on helping behaviours that are performed outside of the context of repeated dyadic partnerships and on how individual reputations for being helpful mediate the emergence and maintenance of cooperative societies. Our focus is on humans where the concern for reputation appears most developed, but we have in mind a broader perspective encompassing other animals where some reputational concerns have been reported [19].

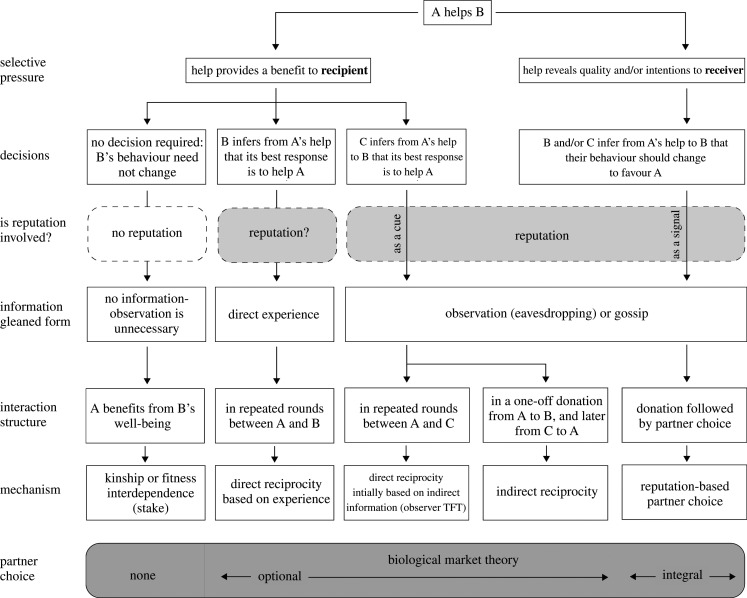

Figure 1.

Reputations: their origins and consequences. The figure illustrates how when one individual (A) helps another (B) then it can both provide a benefit to the recipient but can also reveal its quality and/or intentions to a receiver, who may be the recipient or an observer. See text for the full explanation. Adapted and extended from [20].

(b) . A spectrum of reputation

In figure 1, we show schematically how individuals might develop reputations for helping, and how others might respond to these reputations in a manner that makes reputation building adaptive. Following [20], we distinguish the selective pressures behind why an individual A helps individual B in the presence of individual C. These mechanisms can be divided into whether they act primarily through the actual benefits to the recipient(s) or through the information that the helping act conveys. We discuss each of these in turn.

The first selective pressure on A's helping is via the benefits to B, which may mean that the recipient B, or a third-party C, are more likely to provide a return benefit to A. These routes to cooperation are direct reciprocity [3] and IR [7], respectively. IR is based on the ‘observer’ picking up cues, either by their own observation or via gossip, which increase their likelihood of paying a cost to benefit the original actor. As the name implies, it is explicitly based on reciprocation of the costs and benefits of helping. This is a crucial point: IR is not a catch-all term for benefitting through third parties.

In between the concepts of direct and IR is the possibility that individuals could pick up cues of how others have behaved (perhaps by eavesdropping [21]) so that they can then use this to inform their helping decision when they meet the observed party for directly reciprocal interaction. This strategy has been termed observer tit-for-tat (OTFT) by [22] in one of the leading game-theoretical papers to explicitly consider the role of reputations. Some confusion has arisen here because [23] referred to IR as direct reciprocity occurring in the presence of others. Although OTFT encapsulates Alexander's verbal description, it is not a strategy of IR: individuals with good reputations benefit from directly reciprocal interactions.

The second selective pressure we consider is that by being helpful, individuals reveal information about themselves. It may then pay to invest in reputations so as to be seen to be helpful. In this sense, reputations for helping function as signals, where signals are defined as phenotypic traits adapted to change the behaviour of a receiver in a way that is beneficial to the signaller [24]. We note that the receiver of the signal may or may not be the recipient of the act of help, and that the ‘help’ need not strictly even be beneficial to anyone [25] to function as a signal, although we are concerned here with signals that do help others. The idea that help is selected for as a signal contrasts with typical models of help which work through the benefits to recipients (e.g. [2,26]. To put this in other words, IR could be conceived as involving individuals changing the behaviour of others so that they are more likely to help them. However, this conception does not change the basic nature of IR as involving reciprocation. By contrast, signal receivers do not simply reciprocate a helpful act, but change their behaviour in a way that is beneficial to the signaller yet does not necessarily incur a net cost to the signal receiver. This means that signalling models of help [27] are formulated in a fundamentally different way than models based on reciprocity.

We focus in this paper on how a signal receiver may be more likely to choose the signaller for mutually beneficial interactions. This process was initially defined as ‘competitive altruism’ by [28] through comparison with the term ‘reciprocal altruism’ [3]. The term has been widely adopted (e.g. [29–37]). Nevertheless, here we follow [38] in using the more descriptive term ‘reputation-based partner choice’ (RBPC). When specifically referring to the escalation of pro-social behaviour owing to competition for partners, we use the term ‘competitive helping’ [39,40] to avoid the term ‘altruism’ which is reserved by some biologists for where there is a net lifetime fitness cost [41].

The role of partner choice is integral to the concept of competitive helping, and this provides a link with the theory of biological markets [42,43] which has been developed to understand, for example, between-species mutualisms. We illustrate this in figure 1 as a dimension representing whether individuals have a choice of partner.

We now consider IR and RBPC in more detail.

2. Indirect reciprocity

(a) . Theoretical basis

IR has been reviewed elsewhere [8,44] so we focus here on the basic structure of IR theory and models to allow comparison with other theories of reputation-based cooperation (figures 1 and 2). IR occurs when one individual pays a cost to benefit another and then an ‘observer’ pays a cost to benefit the original donor. For simplicity, we include in the term ‘observer’ those who witness the helping as a third-party [45] and those who are recipients of ‘gossip’ about it [46]. Provided the benefits exceed the costs then a helper makes a net profit via the observer [7]. This process is best understood by comparison with direct reciprocity: whereas direct reciprocity involves one individual paying a cost to benefit a second individual, in IR the reciprocal donation comes from an observer. IR, like its direct counterpart, works when cooperators are rewarded and defectors are sanctioned. This principle was applied to repeated games with changing partners by [47].

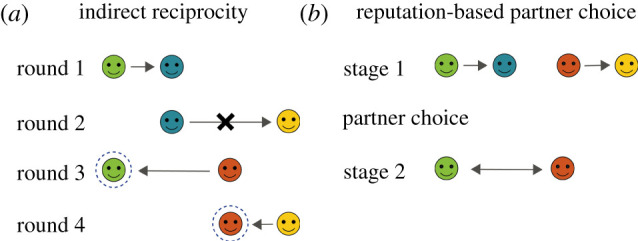

Figure 2.

Comparing IR with reputation-based partner choice. (a) IR consists of a series of donations, each with a cost c to the donor and a benefit b to the recipient. In round 1, green donates to blue (as illustrated by the arrow) but in round 2, blue does not help yellow (as indicated by the ‘x’). Green gains a positive reputation index, typically designated a ‘positive image score’. If this image score increases its probability of receiving, in this case from red in round 3, then green makes a net profit. (b) In RBPC, individuals interact synchronously with some helping others, in this case, green and red helping blue and yellow, respectively. Individuals can then select partners for the second stage. Here, green and red select each other as partners on the basis that they each have invested in reputations for helping others. If the cooperative relationship between green and red is mutually beneficial, then this can outweigh the costs of investing in a reputation by helping in stage 1. (Online version in colour.)

Much of the theoretical work on IR has involved computer simulation of strategies. Among these, a well-known candidate was ‘image scoring’, a simple mechanism in which a reputation index was incremented when individuals donated and decremented when they did not [26]. However, this strategy is not evolutionarily stable because it does not allow for ‘justified defections’ when individuals meet non-cooperators [48,49]. Defecting on a defector harms an individual's image score, meaning that the unhelpful individual will not be helped by a third-party. This weakness means that individuals are incentivized to reward all players, regardless of whether they cooperate, simply to protect their own reputation. Cooperation can collapse as a result. A prior solution to this problem is if individuals use a ‘standing’ strategy [50], whereby justified defection is still rewarded by third parties. An extension of this approach, analysing a large number of possible strategies [51], found that ‘stern-judging’ was most successful [52,53]. This strategy helps helpers and (crucially) sanctions defectors; essentially what [47] showed.

(b) . Empirical evidence

While most interest in IR remains theoretical, experiments have provided evidence that people give preferentially to those with positive image scores [54–57]. IR has since been considered as the main reason why individuals, especially humans, care about being seen to help others. Some authors have also argued that IR provides the selective pressure behind the evolution of language and morality [8,51,53]. However, IR theory requires that people discriminate between justified and unjustified defection, and although there is some evidence for this [14], other studies have failed to find such an effect [54,58,59]. Evidence of IR in real-world settings has also been claimed [18,60] (but see [61,62] for critiques).

3. Reputation-based partner choice

(a) . Theoretical basis

The concept of RBPC emerged from modelling which showed how generosity and choosiness can co-evolve [63]. RBPC is based on conceptualizing individuals in a social group making decisions about interaction partners, for example a bird choosing a mate, or a person choosing a friend. It posits that individuals invest in cooperative reputations so that they will be more likely to be chosen for profitable partnerships [28,37]. This approach contrasted with that of reciprocity within set partnerships where cooperation was seen as being difficult to evolve.

RBPC theory has some key assumptions:

-

(i)

individuals vary in quality and/or intentions as potential social or sexual partners;

-

(ii)

individuals perform helpful acts that provide public information which others can observe to judge quality and/or intentions (signals); and

-

(iii)

individuals can choose their partners for further interactions (individuals may play one or both roles).

Individuals benefit from choosing partners who are either high quality or have good intentions (i.e. they are both able and willing to confer benefits; [30]). We then infer that those seen to be most helpful will either assortatively partner with each other (in the case of social selection [64–66]) or will be preferentially selected by sexual partners (in the case of sexual selection). This hypothesis of assortative pairing arises from models of the correlation between generosity and choosiness [63,67]. Once paired, individuals form a cooperative relationship which may be of direct reciprocity, by-product benefits, or other mechanisms involving interdependence between the two partners. The signaller benefits from their investment in signalling and the receiver of the signal benefits from being choosy. Figure 2b illustrates these processes in a simple case and where signallers are also receivers and where receivers are also recipients.

Where individuals compete for access to partners, RBPC theory proposes that displays of increasingly costly behaviour will be used as signals to attract the best partners, hence helping is ‘competitive’ because what matters most is how much one helps relative to others [28–30,37]. In this way, helpful acts that are not directly reciprocated can be explained not as part of a system of IR, but as ways of enhancing a reputation which, through assortative partner choice, will lead to profitable relationships. RBPC theory provides a functional explanation for helping when the benefits arising from increased access to profitable partnerships exceed the costs of investing in a reputation (e.g. [39]).

RBPC theory assumes that individuals honestly signal their quality as a strategic investment which changes receiver behaviour [24]. When RBPC theory was developed, the best-known theory of honest signalling was Zahavi's handicap principle [68–71]. This theory encapsulates the idea that the cost of a trait (or ‘handicap’) ensures its honesty because only the highest quality individuals can afford such a cost. It was applied to sexually selected traits such as the classic peacock's train, but also to helping [72]. Zahavi's idea was that competition over pro-social behaviours such as mobbing predators led to increased ‘social prestige’. RBPC theory built on the concept of honest signalling, but stressed the role of signals in choosing partners for cooperative interactions, and not their role in competing for social prestige. More recently the term ‘handicap principle’ has been disfavoured relative to the more generic ‘costly signalling theory’ [27]. We prefer to use the term ‘honest signalling’ rather than ‘costly signalling’ to avoid the misconception that the cost itself makes signalling systems honest. Signal honesty arises when the marginal benefits differ, typically between types such as low- and high-quality individuals [73,74].

The use of helping as a costly signal of quality has since been formalized in a game-theoretic framework [27]. This holds that there will be a separating equilibrium at which high-quality types signal while low-quality types do not. Cooperative reputations then allow observers to correctly deduce the underlying quality of the signaller [75]. The use of helping as a costly signal of quality means that selection acts on how well the signal functions to change the behaviour of receivers, and not via the fitness effects of benefits given to recipients. Indeed it has been shown that ‘costly but worthless' gifts may be the product of selection [25], such as an investment of time [76]. If it pays high-quality types to signal (and low-quality types not to) then this can lead to unconditional helping instead of direct reciprocity [77].

In formalizing RBPC as a two-stage process, we implicitly assume that a helper's actions can predict future ability or willingness to help. Such a relationship seems reasonable if signals reflect physical ability which remains stable over time; or if the stake that one individual has in another is stable [78]; or alternatively if there is a cost to behavioural flexibility [79]. We also assume that helping improves an individual's reputation, although Dumas et al. [80] show how this can be context dependent. Further development of the RBPC approach should consider more explicitly the range of joint-action games, because these can lead to either enhancement or suppression of cooperation [81].

(b) . Sexual selection

Sexual selection is a process in which individuals compete for matings, often by producing signals of quality (such as the iconic peacock's train). A cornerstone of the concept of competitive helping was that just as individuals might compete for social partners using signals of cooperation, so these signals might also be used in competition for sexual partners. Helping might be a sexually selected signal revealing differences in quality. This theory remains outside of the mainstream cooperation literature but has been supported by several studies (see below).

(c) . Signalling intentions

An alternative or additional hypothesis is that costly investments might be honest signals of intent. That is, those who develop a reputation for helping might be more likely to be more cooperative and so may be preferred as partners [28,30,37,42,75,82]. The notion that reputations might signal future intent (rather than underlying quality) has been stated verbally by several of these authors, has been applied in multiple contexts like food sharing [83] and has only recently been developed theoretically [84–86]; these models add an important dimension in understanding how reputations can be rewarded. Several studies support the idea that there are signalling benefits of generosity—that those who are more generous are trusted more [87–89]. One issue with costly signalling as an explanation for helping is that the theory fails to predict what costs should be spent on—whether on helpful acts or simply wasteful ones. This problem of ‘equilibrium selection’ might be solved if cues of cooperative behaviour have evolved into signals [90].

(d) . Evidence for reputation-based partner choice

We consider that evidence for RBPC requires the following:

-

(i)

actors invest in a reputation by helping more when their contributions are made public to potential partners (but see below);

-

(ii)

those who give more are more likely to be chosen as partners; and

-

(iii)

those investing in a reputation and chosen as partners have higher net pay-offs.

Experimental studies have used a two-stage design: first a game where individuals may signal by contributing more to potential partners, then a game where they can interact with a chosen partner. Several studies have used this design [31,33,38]. Such studies show that contributions in social dilemmas increase not only when they are made public, but also further, when people are told that partners may be chosen for later interactions. The strategy of investing in a cooperative reputation reaps rewards in that better contributors obtain more profitable partnerships. Other experimental economic games have also been employed, e.g. both Chiang [91] and Debove et al. [92] found ultimatum game players prefer partners who make more generous offers and that this can result in fairness. A link between charitable or blood donation and reputation has been found by for example [93,94] and between blood donation and generosity [95]. Furthermore, competition for partners leads individuals to share honest gossip about others [96]. There is evidence that generosity is displayed publicly [97], but whether individuals do choose the most cooperative others as alliance partners seems context dependent [98]. In fact the prediction that individuals will ostentatiously display higher generosity is simplistic, because it may then be apparent that the helper is motivated by strategic gains rather than a cooperative disposition. There is evidence that people either do not help when it is public or hide their beneficent acts from others [99].

Generosity is well known to be a desirable trait in mate choice [100]. A few experimental studies have also found evidence that helping is used as a display to attractive members of the opposite sex [101,102] is deemed attractive [103,104], or results in higher mating success [105]. Yet despite this, sexual selection is rarely invoked in explaining cooperation, and a high profile review does not include it as one of the routes to cooperation [106]. An analysis of online charity donations reveals that when males make large donations to attractive female fundraisers, other males respond in kind, providing field evidence for competitive helping in which helpful acts are used as a display to attract partners [40].

(e) . Indirect reciprocity versus reputation-based partner choice

Having described the processes of IR and of RBPC we compare their domains, assumptions, requirements and predictions. Some key differences between IR and RBPC are summarized below and in figure 2.

(i) . The structure of interactions

RBPC is explicitly based on a two-stage model of cooperative interactions in which individuals first build up cooperative reputations and then choose partners for further interactions (figure 2). The significance of this structure with two separate stages each involving different processes and having different pay-offs is that whereas reciprocity must be evolutionarily stable within multiple rounds of donation games, RBPC can involve a loss in one stage (building a reputation by helping) in order to make a profit in a second stage involving a different kind of game (a mutually beneficial pairwise relationship).

(ii) . The role of signalling

Signalling works when it changes a receiver's behaviour [24]. Receivers may or may not be recipients of any benefits resulting from the costs invested in a signal. RBPC theory explicitly incorporates signalling theory. By contrast, there has been some confusion in the literature about the relationship between IR and signalling. The image scoring model has been explicitly described as involving Zahavi's handicap principle [8,26,107]. It has been said that IR can explain behaviours such as the competition for status described by Zahavi in Arabian babblers [71]. Of course, donating in IR is costly, but models such as that of image scoring explicitly model it as operating through the transfer of benefits to a recipient and do not include or require any signalling function. IR is therefore entirely independent of Zahavi's handicap principle: there is no condition dependence or communication of differences in quality. Help that is indirectly reciprocated need be no more Zahavian than that which is directly reciprocated. It could be argued that donation acts as a signal in IR; however, the most parsimonious interpretation is that models of IR work through individuals picking up cues which provide information that is fed into the strategy of how to respond (figure 1).

(iii) . Who benefits from the help

IR can only work when donations provide a benefit to the recipient. In RBPC, it is important to distinguish the receiver of the signal and the recipient of the donation. These may be the same or different individuals. Furthermore, there may actually be no benefit to any other individual [25,78,108–110]. A good example of helping as a signal with no benefit is where people contribute to step-level public goods games even when their contribution makes no additional effect on the provision of the public good: they just seem to be motivated to be seen to be contributing [111]. Similarly, donating in economic games regardless of benefit has been dubbed ‘ineffective altruism’ to contrast with ‘effective altruism’ in which philanthropic acts are encouraged to have maximum impact.

(iv) . Selective benefit to the helper

In both IR and RBPC, individuals invest in a reputation in order to make a net direct fitness benefit. The difference is that in IR the benefit comes via a reciprocal donation game, whereas in RBPC the benefit comes via a mutually beneficial relationship. In the case of choosing a sexual partner, the benefits of investing in a good reputation and being chosen by a good partner may come through increased breeding success. This is not a form of reciprocity.

(v) . Conditionality

For any form of cooperation to work there must be some form of assortment: cooperators must interact more with other cooperators. In reciprocity, this happens through discrimination, whereas in RBPC, it works through assortative partner choice. IR is explicitly conditional in that it can only operate where individuals help those who help others and do not help those who do not help others. RBPC has no such conditionality. Individuals help others as a signal of abilities and/or cooperativeness [112]. They benefit from then being more likely to be chosen for profitable partnerships. The issue of conditionality is a key reason why IR cannot explain acts that cannot be conditional upon whether the recipient has donated, such as when giving to charity.

(vi) . Partner choice

The theory of IR involves no partner choice. However, it can be extended so that individuals can select who to give to [113,114]. This can have a crucial effect in making the simple strategy of image scoring more stable because partner choice (or recipient selection) avoids the problem of whether image scorers would enhance their own reputation at the cost of discrimination by giving to non-donors. However, IR cannot be extended to involve choosing a partner for repeated interaction as this would become direct reciprocity [45] because individuals would then be helping in order to be more likely to receive a directly rather than an indirectly reciprocated benefit.

RBPC explicitly involves partner choice for profitable relationships. The process may be likened to a biological market [43], although a market is based on trade between two different classes of individuals, those buying and those selling goods or services, whereas in mutual partner choice, all ‘suppliers’ are also ‘consumers’. The key concepts of buyers and sellers and of shifting trading prices with supply and demand have helped elucidate behaviour such as where baboons exchange grooming for access to infants [115]. Biological market theory (BMT) has been developed and reviewed in [30,39,42]. Both BMT and RBPC emphasize the importance of partner choice. Where BMT differs from RBPC is that it is not explicitly about signalling: individuals make offers so as to be chosen as partners, but BMT is based on those offers being competitive in a marketplace. It is not about making offers that signal information, it is about making offers that provide benefits to recipients: for example in the baboon grooming system, more subordinate females need to spend longer grooming others to get access to infants [115]. One way to think of this is that BMT assumes buyers and sellers will maximize profits within a single ‘game’ scenario, whereas signalling assumes a combination of two ‘games’, the first in which players make a strategic loss so as to gain in the second game when chosen as a partner for trade.

(vii) . Constraints

It has been recognized that those with cooperative strategies may not always have the resources to cooperate. These so-called ‘phenotypic defectors’ have been included in models of IR and actually stabilize cooperation by maintaining discrimination in the system [116,117]. Differences in state have also been considered by [48]. Such differences between individuals are integral to the theory that individuals can choose between potential partners of differing quality [28].

(viii) . Dynamics

A corollary of choosing between partners on the basis of their reputations for helping is that those potential partners may then compete to be chosen. The prediction that this competition will lead to escalation in helping behaviour lies behind the theory of ‘competitive altruism’ [28,63,67,118]. This kind of escalation has been demonstrated in experimental economic games [29,31,38] and in charitable donations [40,84]. Importantly, this escalation shows that RBPC is explicitly built to deal with graded helping behaviour, either because individuals can vary the amount of help they give or because choosers evaluate the number of helping acts when decisions are binary.

(ix) . Humans and other animals

We have focused on reputation-based helping in humans while maintaining a broader theoretical perspective encompassing other animals. However, is IR and/or RBPC found in non-human animals? There are a few examples of reputational concerns in non-human animals. For example, cleaner fish Labroides dimidiatus behave cooperatively towards client fish by removing ectoparasites when observed by bystanders [119]. We do not know of specific examples of IR in non-human animals, and the examples that there are seem better explained as cases where individuals invest in a positive reputation and benefit from being chosen as a partner. It does seem that a concern for reputation is much more common in humans than in other animals. One hypothesis is that while signals of quality may be common in non-human animals in the contexts of aggression and courtship, the signals of intent involved in cooperative interactions may be more stable when supported by the human capacities for language and gossip [86].

(x) . Evolution

The initial evolution of IR, like direct reciprocity, is likely to depend upon reciprocators being close kin [2]. It can be speculated that RBPC could have evolved from a system in which those seeking partners eavesdropped on cues. Once audiences attend to a cue of quality or intent, signallers will start investing in displaying that cue. This kind of process has been modelled by [90]. In this way, honest signals that have evolved from related cues could evade the equilibrium selection problem whereby costly signals could evolve to be non-cooperative [27].

4. Discussion

We have reviewed the essential features of different functional explanations for how individuals benefit from being seen to help others. We have argued that although IR has been the focus of much interest, it is just one possible explanation for reputation building. IR has sometimes been wrongly used as an umbrella term for benefits arising through third parties. Just as individuals may benefit in ways other than direct reciprocity from recipients of help, so they can also benefit in ways other than IR from third parties. A set of other theories, which might be united under the label of ‘strategic signalling’, offer explanations for why individuals might benefit from being seen to be helpful.

We have emphasized the role of partner choice in driving such signalling. We suggest that more research should be directed towards the theoretical underpinnings and empirical evidence for reputations as signals that are used in partner choice, as opposed to what strategy to play in IR games. This work may have broader significance in assessing whether the use of language and gossip, and the development of moral systems are indeed tied to IR, as has been suggested, or whether they have a function in choosing partners.

More empirical work is needed that clearly distinguishes IR from RBPC. One experiment suggested that RBPC is more effective in inducing strategic reputation building than is IR and can thereby provide a more robust mechanism for maintaining cooperation in social dilemmas [120]. This is consistent with the hypothesis that where reputations are really important is when making decisions about partnerships. In table 1, we set out some of the differences which may allow us to distinguish between systems of IR and of RBPC.

Table 1.

Expected differences between reputation systems based on IR versus RBPC.

| IR | RBPC | |

|---|---|---|

| can individuals choose partners? | optional | integral |

| how many rounds are required? | multiple, for reciprocation | a single two-stage round can be sufficient |

| do helpers interact again with the recipient? | no (becomes direct reciprocity) | not required |

| must the ‘helping’ benefit the recipient? | yes | not required |

| are the return benefits costly to confer? | yes | no |

| what are return benefits based upon? | helper's past actions | helper's inferred future value |

| do individuals differ in quality and/or intentions? | not assumed | yes |

| do the theories take account of constraints? | can be incorporated as ‘phenotypic defectors’ | helping can honestly signal quality within constraints |

| do helping acts escalate in magnitude? | no | yes |

Theoretical interest in IR has focused on solving the problem of why individuals might cooperate with each other even when they never meet again. As a result, IR has come to be seen as the primary explanation for why individuals might benefit from cooperative reputations. However, the formalization of IR makes it an unlikely solution to real-world issues such as how cooperation is sustained in large, fluid societies. In such societies, it is unlikely that individuals who never meet again will nevertheless know the reputations of those with whom they will have one-off interactions. By contrast, the RBPC approach came out of formalizing how animals interact socially and form relationships. We have argued that we are more likely to invest in a reputation in the context of choosing partners for cooperative relationships than we are to follow the IR rule of ‘help those who help others’. We therefore argue that the RBPC approach may be more productive in practice for explaining how acts of apparent selflessness such as donations to charity, heroism in humans or courtship feeding in birds are integral to long-term social and sexual partnerships with repeated interactions. It may be that while theoretical focus within the cooperation literature has been on solving the hardest problems, real-world behaviour may be explicable by the simpler processes of choosing among partners that display their qualities and intentions.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

G.R. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Competing interests

N.R. is the author of the 2021 book, The social instinct: how cooperation shaped the world.

Funding

N.R. was supported by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship and by the Leverhulme Trust. H.M.M. wants to thank Professor Álvaro Arrizabalaga and the MINECO project with reference HAR2017-82483-C3-1-P for financial support. P.B. was supported by the Social Science & Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC grant no. 430287). R.B. was supported by the Swiss Science Foundation (grant no. 310030_192673). A.F. was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (AdG agreement no. 785635; PI Carsten K.W. De Dreu).

References

- 1.Hamilton WD. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1-52. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod R, Hamilton WD. 1981. The evolution of cooperation. Science 211, 1390-1396. ( 10.1126/science.7466396) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trivers RL. 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35-57. ( 10.1086/406755) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aktipis A, et al. 2018. Understanding cooperation through fitness interdependence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 429-431. ( 10.1038/s41562-018-0378-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Queller DC. 2011. Expanded social fitness and Hamilton's rule for kin, kith and kind. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 108(Supp. 2), 10792. ( 10.1073/pnas.1100298108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts G. 2005. Cooperation through interdependence. Anim. Behav. 70, 901-908. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.02.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. 1989. The evolution of indirect reciprocity. Soc. Net. 11, 213-236. ( 10.1016/0378-8733(89)90003-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. 2005. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature 437, 1291-1297. ( 10.1038/nature04131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohtsuki H, Iwasa Y. 2005. How should we define goodness? Reputation dynamics in indirect reciprocity (vol 231, pg 107, 2004). J. Theor. Biol. 232, 451. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsuki H, Iwasa Y, Nowak MA. 2009. Indirect reciprocity provides only a narrow margin of efficiency for costly punishment. Nature 457, 79-82. ( 10.1038/nature07601) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milinski M. 2016. Reputation, a universal currency for human social interactions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 1687. ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. 2002. Reputation helps solve the 'tragedy of the commons'. Nature 415, 424-426. ( 10.1038/415424a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockenbach B, Milinski M. 2006. The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature 444, 718-723. ( 10.1038/nature05229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swakman V, Molleman L, Ule A, Egas M. 2016. Reputation-based cooperation: empirical evidence for behavioral strategies. Evol. Hum. Behav. 37, 230-235. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.12.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark D, Fudenberg D, Wolitzky A. 2020. Indirect reciprocity with simple records. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11344. ( 10.1073/pnas.1921984117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rand DG, Nowak MA. 2013. Human cooperation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 413-425. ( 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitaker RM, Colombo GB, Rand DG. 2018. Indirect reciprocity and the evolution of prejudicial groups. Sci. Rep. 8, 13247. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-31363-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoeli E, Hoffman M, Rand DG, Nowak MA. 2013. Powering up with indirect reciprocity in a large-scale field experiment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10424. ( 10.1073/pnas.1301210110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manrique HM, Zeidler H, Roberts G, Barclay P, Walker M, Samu F, Fariña A, Bshary R, Raihani N. 2021. The psychological foundations of reputation-based cooperation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200287. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0287) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts G, Sherratt TN. 2007. Cooperative reading: some suggestions for integration of the cooperation literature. Behav. Processes 76, 126-130. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.12.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covas R, McGregor PK, Doutrelant C. 2007. Cooperation and communication networks. Behav. Processes 76, 149-151. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.12.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollock GB, Dugatkin LA. 1992. Reciprocity and the evolution of reputation. J. Theor. Biol. 159, 25-37. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80765-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander RD. 1987. The biology of moral systems. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maynard Smith J, Harper D. 2003. Animal signals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sozou PD, Seymour RM. 2005. Costly but worthless gifts facilitate courtship. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 1877-1884. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3152) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. 1998. Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature 393, 573-577. ( 10.1038/31225) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gintis H, Smith EA, Bowles S. 2001. Costly signaling and cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 213, 103-119. ( 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2406) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts G. 1998. Competitive altruism: from reciprocity to the handicap principle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 427-431. ( 10.1098/rspb.1998.0312) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barclay P. 2004. Trustworthiness and competitive altruism can also solve the "tragedy of the commons". Evol. Hum. Behav. 25, 209-220. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.04.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barclay P. 2013. Strategies for cooperation in biological markets, especially for humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 164-175. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.02.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barclay P, Willer R. 2007. Partner choice creates competitive altruism in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 749-753. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Böhm R, Regner T. 2013. Charitable giving among females and males: an empirical test of the competitive altruism hypothesis. J. Bioecon. 15, 251-267. ( 10.1007/s10818-013-9152-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardy CL, Van Vugt M. 2006. Nice guys finish first: the competitive altruism hypothesis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 1402-1413. ( 10.1177/0146167206291006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann E, Engelmann JM, Tomasello M. 2019. Children engage in competitive altruism. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 179, 176-189. ( 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macfarlan SJ, Remiker M, Quinlan R. 2012. Competitive altruism explains labor exchange variation in a dominican community. Curr. Anthropol. 53, 118-124. ( 10.1086/663700) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts G. 2015. Human cooperation: the race to give. Curr. Biol. 25, R425-R427. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Vugt M, Roberts G, Hardy C. 2007. Competitive altruism: development of reputation-based cooperation in groups. In Handbook of evolutionary psychology (eds Dunbar R, Barrett L). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sylwester K, Roberts G. 2010. Cooperators benefit through reputation-based partner choice in economic games. Biol. Lett. 6, 659-662. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barclay P. 2011. Competitive helping increases with the size of biological markets and invades defection. J. Theor. Biol. 281, 47-55. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.04.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raihani NJ, Smith S. 2015. Competitive helping in online giving. Curr. Biol. 25, 1183-1186. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A. 2007. Social semantics: altruism, cooperation, mutualism, strong reciprocity and group selection. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 415-432. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01258.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barclay P. 2016. Biological markets and the effects of partner choice on cooperation and friendship. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 7, 33-38. ( 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noë R, Hammerstein P. 1994. Biological markets: supply and demand determine the effect of partner choice in cooperation, mutualism and mating. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 35, 1-11. ( 10.1007/BF00167053) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okada I. 2020. A review of theoretical studies on indirect reciprocity. Games 11, 27. ( 10.3390/g11030027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts G. 2008. Evolution of direct and indirect reciprocity. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 173-179. ( 10.1098/rspb.2007.1134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sommerfeld RD, Krambeck HJ, Semmann D, Milinski M. 2007. Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17 435-17 440. ( 10.1073/pnas.0704598104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kandori M. 1992. Social norms and community enforcement. Rev. Econ. Stud. 59, 63-80. ( 10.2307/2297925) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leimar O, Hammerstein P. 2001. Evolution of cooperation through indirect reciprocity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 745-753. ( 10.1098/rspb.2000.1573) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panchanathan K, Boyd R. 2003. A tale of two defectors: the importance of standing for evolution of indirect reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 224, 115-126. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00154-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugden R. 1986. The economics of rights, cooperation and welfare. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohtsuki H, Iwasa Y. 2006. The leading eight: social norms that can maintain cooperation by indirect reciprocity. J. Theor. Biol. 239, 435-444. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.08.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacheco JM, Santos FC, Chalub F. 2006. Stern-judging: a simple, successful norm which promotes cooperation under indirect reciprocity. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2, 1634-1638. ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020178) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santos FP, Santos FC, Pacheco JM. 2018. Social norm complexity and past reputations in the evolution of cooperation. Nature 555, 242. ( 10.1038/nature25763) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milinski M, Semmann D, Bakker TCM, Krambeck HJ. 2001. Cooperation through indirect reciprocity: image scoring or standing strategy? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 2495-2501. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1809) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seinen I, Schram A. 2006. Social status and group norms: indirect reciprocity in a repeated helping experiment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 50, 581-602. ( 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.10.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semmann D, Krambeck HJ, Milinski M. 2004. Strategic investment in reputation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 56, 248-252. ( 10.1007/s00265-004-0782-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wedekind C, Milinski M. 2000. Cooperation through image scoring in humans. Science 288, 850-852. ( 10.1126/science.288.5467.850) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samu F, Számadó S, Takács K. 2020. Scarce and directly beneficial reputations support cooperation. Sci. Rep. 10, 11486. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-68123-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto H, Suzuki T, Umetani R. 2020. Justified defection is neither justified nor unjustified in indirect reciprocity. PLoS ONE 15, e0235137. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0235137) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lange F, Eggert F. 2015. Selective cooperation in the supermarket field experimental evidence for indirect reciprocity. Hum. Nat. 26, 392-400. ( 10.1007/s12110-015-9240-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bshary R, Raihani NJ. 2017. Helping in humans and other animals: a fruitful interdisciplinary dialogue. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170929. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0929) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raihani NJ, Bshary R. 2015. Why humans might help strangers. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 39. ( 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherratt TN, Roberts G. 1998. The evolution of generosity and choosiness in cooperative exchanges. J. Theor. Biol. 193, 167-177. ( 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0703) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lyon BE, Montgomerie R. 2012. Sexual selection is a form of social selection. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 2266-2273. ( 10.1098/rstb.2012.0012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nesse R. 2009. Runaway social selection for displays of partner value and altruism. In The moral brain (eds Verplaetse J, Schrijver J, Vanneste S, Braeckman J), pp. 211-231. Berlin, Germany: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 66.West-Eberhard MJ. 1983. Sexual selection, social competition, and speciation. Q. Rev. Biol. 58, 155-183. ( 10.1086/413215) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McNamara JM, Barta Z, Fromhage L, Houston AI. 2008. The coevolution of choosiness and cooperation. Nature 451, 189-192. ( 10.1038/nature06455) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grafen A. 1990. Biological signals as handicaps. J. Theor. Biol. 144, 517-546. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80088-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zahavi A. 1975. Mate selection: a selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 53, 205-214. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zahavi A. 1977. The cost of honesty (further remarks on the handicap principle). J. Theor. Biol. 67, 603-605. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(77)90061-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zahavi A. 1997. The handicap principle. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zahavi A. 1995. Altruism as a handicap: the limitations of kin selection and reciprocity. J. Avian Biol. 26, 1-3. ( 10.2307/3677205) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lachmann M, Számadó S, Bergstrom CT. 2001. Cost and confilict in animal signals and human language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13 189-13 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Penn DJ, Számadó S. 2020. The handicap principle: how an erroneous hypothesis became a scientific principle. Biol. Rev. 95, 267-290. ( 10.1111/brv.12563) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bird B, Smith R, Eric A. 2005. Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Curr. Anthropol. 46, 221-248. ( 10.1086/427115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seymour RM, Sozou PD. 2009. Duration of courtship effort as a costly signal. J. Theor. Biol. 256, 1-13. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.09.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lotem A, Fishman MA, Stone L. 2003. From reciprocity to unconditional altruism through signalling benefits. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 199-205. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.2225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barclay P, Bliege Bird R, Roberts G, Számadó S. 2021. Cooperating to show that you care: costly helping as an honest signal of fitness interdependence. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200292. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0292) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McNamara JM, Barta Z. 2020. Behavioural flexibility and reputation formation. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201758. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1758) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dumas M, Power E, Barker J. 2021. When does reputation lie? Dynamic feedbacks between costly signals, social capital, and social prominence. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200298. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McNamara JM, Doodson P. 2015. Reputation can enhance or suppress cooperation through positive feedback. Nat. Commun. 6, 6134. ( 10.1038/ncomms7134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Silk JB. 2002. Grunts, girneys, and good intentions: the origins of strategic commitment in non-human primates. In Commitment: evolutionary perspectives (ed. Nesse R), pp. 138-157. New York, NY: Russell Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bird RB, Ready E, Power EA. 2018. The social significance of subtle signals (review paper). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 452-457. ( 10.1038/s41562-018-0298-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barclay P, Barker JL. 2020. Greener than thou: people who protect the environment are more cooperative, compete to be environmental, and benefit from reputation. J. Environ. Psychol. 72, 101441. ( 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101441) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quillien T. 2020. Evolution of conditional and unconditional commitment. J. Theor. Biol. 492, 110204. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roberts G. 2020. Honest signaling of cooperative intentions. Behav. Ecol. 31, 922-932. ( 10.1093/beheco/araa035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diekmann A, Jann B, Przepiorka W, Wehrli S. 2013. Reputation formation and the evolution of cooperation in anonymous online markets. Am. Sociol. Rev. 79, 65-85. ( 10.1177/0003122413512316) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fehrler S, Przepiorka W. 2013. Charitable giving as a signal of trustworthiness: disentangling the signaling benefits of altruistic acts. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 139-145. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.11.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Przepiorka W, Liebe U. 2016. Generosity is a sign of trustworthiness: the punishment of selfishness is not. Evol. Hum. Behav. 37, 255-262. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.12.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Biernaskie JM, Perry JC, Grafen A. 2018. A general model of biological signals, from cues to handicaps. Evol. Lett. 2, 201-209. ( 10.1002/evl3.57) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chiang YS. 2010. Self-interested partner selection can lead to the emergence of fairness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 31, 265-270. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.03.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Debove S, André JB, Baumard N. 2015. Partner choice creates fairness in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20150392. ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.0392) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bereczkei T, Birkas B, Kerekes Z. 2007. Public charity offer as a proximate factor of evolved reputation-building strategy: an experimental analysis of a real-life situation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 277-284. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.04.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. 2002. Donors to charity gain in both indirect reciprocity and political reputation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 881-883. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.1964) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lyle H, Smith E, Sullivan R. 2009. Blood donations as costly signals of donor quality. J. Evol. Psychol. 7, 263-286. ( 10.1556/JEP.7.2009.4.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Giardini F, Vilone D, Sánchez A, Antonioni A. 2021. Gossip and competitive altruism support cooperation in a Public Good Game. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200303. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0303) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith EA, Bird RB, Bird DW. 2003. The benefits of costly signaling: Meriam turtle hunters. Behav. Ecol. 14, 116-126. ( 10.1093/beheco/14.1.116) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smith KM, Apicella CL. 2020. Partner choice in human evolution: the role of cooperation, foraging ability, and culture in Hadza campmate preferences. Evol. Hum. Behav. 41, 354-366. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Raihani NJ, Power EA. 2021. No good deed goes unpunished: the social costs of prosocial behaviour. Evol. Hum. Sci. 3, E40. ( 10.1017/ehs.202135) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miller GF. 2007. Sexual selection for moral virtues. Q. Rev. Biol. 82, 97-125. ( 10.1086/517857) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Farrelly D, Lazarus J, Roberts G. 2007. Altruists attract. Evol. Psychol. 5, 313-329. ( 10.1177/147470490700500205) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Iredale W, Van Vugt M, Dunbar RIM. 2008. Showing off in humans: male generosity as a mating signal. Evol. Psychol. 6, 386-392. ( 10.1177/147470490800600302) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barclay P. 2010. Altruism as a courtship display: some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions. Br. J. Psychol. 101, 123-135. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McAndrew FT, Perilloux C. 2012. Is self-sacrificial competitive altruism primarily a male activity? Evol. Psychol. 10, 147470491201000107. ( 10.1177/147470491201000107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arnocky S, Piché T, Albert G, Ouellette D, Barclay P. 2017. Altruism predicts mating success in humans. Br. J. Psychol. 108, 416-435. ( 10.1111/bjop.12208) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nowak MA. 2006. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314, 1560-1563. ( 10.1126/science.1133755) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ferriere R. 1998. Evolutionary biology: help and you shall be helped. Nature 393, 517-518. ( 10.1038/31102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bolle F. 2001. Why to buy your darling flowers: on cooperation and exploitation. Theory Dec. 50, 1-28. ( 10.1023/A:1005261400484) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Power EA. 2017. Discerning devotion: testing the signaling theory of religion. Evol. Hum. Behav. 38, 82-91. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.07.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sosis R. 2004. The adaptive value of religious ritual: rituals promote group cohesion by requiring members to engage in behavior that is too costly to fake. Am. Sci. 92, 166-172. ( 10.1511/2004.46.928) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van Vugt M, Hardy CL. 2009. Cooperation for reputation: wasteful contributions as costly signals in public goods. Group Process. Intergroup Relations 13, 101-111. ( 10.1177/1368430209342258) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Samu F, Takács K.2021. Evaluating mechanisms that could support credible reputations and cooperation: cross-checking and social bonding. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 202002302. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0302) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ghang W, Nowak MA. 2015. Indirect reciprocity with optional interactions. J. Theor. Biol. 365, 1-11. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.09.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Roberts G. 2015. Partner choice drives the evolution of cooperation via indirect reciprocity. PLoS ONE 10, e0129442. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0129442) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Barrett L, Henzi SP, Weingrill T, Lycett JE, Hill RA. 2000. Female baboons do not raise the stakes but they give as good as they get. Anim. Behav. 59, 763-770. ( 10.1006/anbe.1999.1361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lotem A, Fishman MA, Stone L. 1999. Evolution of cooperation between individuals. Nature 400, 226-227. ( 10.1038/22247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sherratt TN, Roberts G. 2001. The role of phenotypic defectors in stabilizing reciprocal altruism. Behav. Ecol. 12, 313-317. ( 10.1093/beheco/12.3.313) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Roberts G, Sherratt TN. 1998. Development of cooperative relationships through increasing investment. Nature 394, 175-179. ( 10.1038/28160) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bshary R, Grutter AS. 2006. Image scoring and cooperation in a cleaner fish mutualism. Nature 441, 975-978. ( 10.1038/nature04755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sylwester K, Roberts G. 2013. Reputation-based partner choice is an effective alternative to indirect reciprocity in solving social dilemmas. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 201-206. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.11.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.