Abstract

Background

Accumulating evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected global mental health and well-being. However, the impact amongst homeless persons has not been fully evaluated. The ECHO study reports factors associated with depression amongst the homeless population living in shelters in France during the spring of 2020.

Methods

Interview data were collected from 527 participants living in temporary and/or emergency accommodation following France's first lockdown (02/05/20 – 07/06/20), in the metropolitan regions of Paris (74%), Lyon (19%) and Strasbourg (7%). Interviews were conducted in French, English, or with interpreters (33% of participants, ∼20 languages). Presence of depression was ascertained using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

Results

Amongst ECHO study participants, 30% had symptoms of moderate to severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10). Multivariate analysis revealed depression to be associated with being female (aOR: 2.15; CI: 1.26–3.69), single (aOR: 1.60; CI: 1.01–2.52), chronically ill (aOR: 2.32; CI: 1.43: 3.78), facing food insecurity (aOR: 2.12; CI: 1.40–3.22) and participants’ region of origin. Persons born African and Eastern Mediterranean regions showed higher levels of depression (30–33% of participants) than those migrating from other European countries (14%). Reduced rates of depression were observed amongst participants aged 30–49 (aOR: 0.60; CI: 0.38–0.95) and over 50 (aOR: 0.28; CI: 0.13–0.64), compared to 18–29-year-olds.

Limitations

These data are cross-sectional, only providing information on a given moment in time.

Conclusions

Our results indicate high levels of depression amongst homeless persons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Predicted future instability and economic repercussions could particularly impact the mental health of this vulnerable group.

Keywords: Depression, Mental health, COVID-19, Homeless, Migrant, France

1. Introduction

The instability and poor living conditions of both homeless people and migrants are known risk factors for depression, with rates higher than the general population (Foo et al., 2018; Guardia et al., 2017; Hossain et al., 2020; Laporte et al., 2018). Although estimates vary considerably, studies have found the prevalence of depression within homeless populations to range from 11 to 58% (Fazel et al., 2008), with figures amongst migrants dependant on the host country (Lindert et al., 2009), time since arrival (Foo et al., 2018) and reason for departure (Heeren et al., 2014). Moreover, the number of homeless persons (INSEE and INED, 2012; Yaouancq and Duée, 2014) and the proportion of migrants amongst them (The Fondation Abbé Pierre, 2018; Roze et al., 2020) is increasing in France as in other European countries, with the forecasted economic recession following the pandemic likely to only accentuate this further (Flaming et al., 2021).

Unstable housing negatively impacts mental health both directly and indirectly. Influences extend from structural problems, such as crowding and poor lighting (Campagna, 2016; Liddell and Guiney, 2015; Lima et al., 2020), to social isolation and a lack of social support (Suglia et al., 2011), feelings of unsafety (Clark et al., 2008; Hernández, 2016; 2019), social stigma and a lack of control (Swope and Hernández, 2019). The relationship between homelessness and depression is also partly bidirectional, with mental health problems precipitating social exclusion and financial insecurity (Suglia et al., 2011). When combined with the challenges of migration, such as leaving family and loved ones, as well as difficulties in cultural integration which many migrants experience, even fewer supporting factors for good mental health remain (Pannetier et al., 2017).

Within the general population, mental health is of particular concern in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with research showing increased levels of depression (Fancourt et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2020; Shevlin et al., 2020; Vizard et al., 2020), anxiety (Sigdel et al., 2020), post-traumatic stress (Rossi et al., 2020) and sleep problems (Daly et al., 2020). Amongst homeless persons, risk factors for depression may have been exacerbated during the health crisis; however current available data on this issue are scarce. In the present study, we examine the prevalence of depression and associated risk factors amongst persons living in homeless shelters and temporary accommodation across the metropolitan areas of Paris, Lyon and Strasbourg during the spring of 2020, a large majority of whom were migrant.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The ECHO study is a cross-sectional investigation conducted from May to June (02/05/20 – 07/06/20) amongst persons living in temporary or emergency housing following the first lockdown period in France (17/03/2020 – 10/05/2020). During this period, the French Government actively housed persons residing on the street as a preventative measure against COVID-19, thereby providing a unique recruitment opportunity. Centres used for recruitment were located in the regions of Paris (n = 12), Lyon (n = 5) and Strasbourg (n = 1). Interviews were conducted both in person (98%) or by telephone (2%), in French, English or participants’ chosen language, with the help of independent interpreters to minimise bias due to language barriers (33% of total sample). Over 20 languages were used, most frequently Arabic, Pashto and Dari. Participants were excluded if aged under 18 years, significantly inebriated or presenting cognitive disorders that prevented consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the University of Paris (CER-2020–41).

2.2. Sample

Overall, the shelters used for recruitment were host to 929 persons, of which 669 were present and able to consent. Amongst those invited to participate, 80% (535) agreed to participate and 20% refused. Participants with insufficient depression (PHQ-9) data (1%) were also excluded from the following analyses.

2.3. Assessment of depression

To determine symptoms of depression, the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), validated for use in multicultural settings (Arthurs et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2006), was used. Subjects were asked to report the frequency of their symptoms over the preceding two weeks, rated via a 4-part Likert scale. Participants’ depression score was calculated via the sum of responses to all nine items. As supported by previous literature (Manea et al., 2012), a cut-off score of 10 was used to define a depressed (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) group for subsequent analyses. Whilst the PHQ-9 does not provide a definitive diagnosis of depression, this cut-off score shows good predictive performance when compared to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (Udedi et al., 2019).

2.4. Relevant variables

Explanatory variables were selected based on review of the literature relevant to depression within homeless or migrant populations. Potential risk factors of depression included in the analyses were the following: age (18–29; 30–49; 50 years or more), sex (male; female), partnership status (stable partner; single), family status (no children; currently living with children; has children but living separately), highest completed education level, employment (none; only before lockdown; both before and during lockdown), region of origin based on the World Health Organization categories (World Health Organization, 2004) (Africa; Eastern Mediterranean; America; South-East Asian; Western Pacific; Europe excluding France; France), duration of stay in France (< 6 months; 6–12 months; 1–3 years; 3–5 years; 5+ years, including French natives), French language aptitude (low; moderate; fluent), administrative status (French native; residence permit holder; asylum seeker; no residence permit; other), health insurance (yes; no), chronic illness (yes; no), food insecurity (yes; no), feelings of safety (yes; no), exposure to theft or assault (yes; no), contact with friends/family (yes; no), and participants previous accommodation (other centre/association; unestablished shelter (e.g. camps, squats); street; friends/ family/ other).

French language aptitude was calculated from the sum score of self-reported French speaking, reading and writing ability, each rated on a 4-part Likert scale. Degree of loneliness was measured based on the UCLA loneliness scale (Hughes et al., 2004). In supplementary analyses, we aimed to describe associations between depression and worries surrounding: coronavirus in general; becoming ill; friends or family falling ill; social isolation; job insecurity; complications with administrative procedures; future uncertainty; and, if unwell, being rejected or being unable to receive treatment. Participants were also questioned on their willingness to cooperate with the following preventative measures: visiting a doctor; isolating if unwell; respecting another lockdown; and getting vaccinated.

2.5. Data analysis

The internal reliability between PHQ-9 questions was estimated via Cronbach's Alpha (Gliem and Gliem, 2003). To study associations between participants’ characteristics and the likelihood of depression, generalised logistic regression models were used. Participants from American (n = 6), South-East Asian (n = 5), and Western Pacific (n = 1) regions were excluded due to insufficient sample size, resulting in a final sample of 515 participants. Variables relevant for inclusion in the multivariate statistical model were determined via univariate Chi-square (X²) analysis, as supported by Hosmer and Lemeshow (2002; 2013). A 75% confidence limit was used, based on Bursac et al. (2008), to prevent the arbitrary exclusion of important variables (Bendel and Afifi, 1977; Mickey and Greenland, 1989). McFadden's Pseudo R² was also generated to show the respective fit of each variable (McFadden, 1973). Highly collinear variables were removed based on associations at 99% significance, and subsequently checked using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) with a limit of VIF < 3. Additionally, centre type was included as a random effect in all models.

Missing covariate values were imputed using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011). Post-hoc X² analysis was performed with 95% confidence intervals. All data analysis was performed on R Version 4.0.3.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Participants interviewed were primarily non-French (89%), male (76%), had been in France for less than 3 years (72%), were unemployed (71%), single or without a stable partner (61%), and scored low (vs moderate or high) on ratings for French language aptitude (54%). Roughly half (54%) of study participants had children, although only 19% were currently living with at least one them.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ECHO study participants according to depression status (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10). France, n = 527, May-June 2020. Chi-square, p-value and McFadden Pseudo R².

| Non-depressed(%, n = 371) | Depressed(%, n = 156) | p | Pseudo R² | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 72.3 (289) | 27.8 (111) | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Female | 64.6 (82) | 35.4 (45) | ||

| Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 65.1 (151) | 34.9 (81) | * | 0.01 |

| 30-49 | 72.3 (159) | 27.7 (61) | ||

| 50+ | 81.3 (61) | 18.7 (14) | ||

| Partnership status | ||||

| No stable partner | 67.1 (216) | 32.9 (106) | * | 0.06 |

| Yes, has a stable partner | 77.6 (142) | 22.4 (41) | ||

| Family status | ||||

| No children | 71.0 (174) | 29.0 (71) | 0.75 | 0.09 |

| Currently living with children | 75.0 (75) | 25.0 (25) | ||

| Not living with children | 71.9 (105) | 28.1 (41) | ||

| Highest education level | ||||

| No school/ incomplete primary education | 72.1 (106) | 27.9 (41) | 0.48 | 0.02 |

| Primary or high school education | 72.0 (144) | 28.0 (56) | ||

| College/ Higher education | 66.9 (113) | 33.1 (56) | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 69.4 (258) | 30.6 (114) | 0.20 | 0.05 |

| Employed before lockdown | 72.5 (74) | 27.5 (28) | ||

| Employed before and during lockdown | 83.3 (30) | 16.7 (6) | ||

| Perceived food insecurity | ||||

| Food insecure | 60.9 (123) | 39.1 (79) | ⁎⁎⁎ | 0.05 |

| Not food insecure | 76.8 (242) | 23.2 (73) | ||

| Accommodation before lockdown | ||||

| Other centre/charity | 68.6 (70) | 31.4 (32) | 0.90 | 0.00 |

| Unestablished shelter/squat | 68.8 (88) | 31.3 (40) | ||

| Street | 71.6 (154) | 28.4 (61) | ||

| Friends/family/other | 72.0 (59) | 28.0 (23) | ||

| Region of birth | ||||

| French native | 68.4 (39) | 31.6 (18) | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Africa | 67.0 (135) | 33.0 (66) | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean1 | 70.4 (141) | 29.6 (59) | ||

| Europe (other than France) | 86.0 (49) | 14.0 (8) | ||

| Other | 58.3 (7) | 41.7 (5) | ||

| Administrative status | ||||

| French native | 68.4 (39) | 31.6 (18) | 0.25 | 0.01 |

| Residence permit | 65.9 (93) | 34.1 (27) | ||

| Asylum seeker | 77.5 (110) | 22.5 (57) | ||

| No residence permit | 75.0 (92) | 25.0 (43) | ||

| Other | 68.1 (33) | 31.9 (11) | ||

| Health status | ||||

| Chronic illness (yes) | 61.2 (82) | 38.8 (52) | ⁎⁎ | 0.04 |

| Chronic illness (no) | 73.8 (281) | 26.2 (100) | ||

| Healthcare | ||||

| Medically insured/covered2 | 73.1 (258) | 26.9 (95) | * | 0.01 |

| Uninsured | 64.7 (112) | 35.3 (61) | ||

| French aptitude (self-reported) | ||||

| Fluent | 66.1 (76) | 33.9 (39) | 0.47 | 0.01 |

| Moderate | 73.0 (89) | 27.0 (33) | ||

| Low | 71.2 (203) | 28.8 (82) | ||

| Duration of stay in France | ||||

| < 6 months | 67.8 (101) | 32.2 (48) | 0.78 | 0.02 |

| 6 months - 1 year | 73.6 (53) | 26.4 (19) | ||

| 1 - 3 years | 69.8 (74) | 30.2 (32) | ||

| 3 - 5 years | 66.0 (35) | 34.0 (18) | ||

| 5+ years or French native | 73.0 (100) | 27.0 (37) | ||

| Loneliness | ||||

| Currently lonely | 63.2 (227) | 36.8 (132) | ⁎⁎⁎ | 0.06 |

| Not currently lonely | 85.9 (140) | 14.1 (23) | ||

| Loneliness since lockdown | ||||

| Increase in loneliness | 59.3 (115) | 40.7 (79) | ⁎⁎⁎ | 0.04 |

| No increase in loneliness | 76.8 (252) | 23.2 (76) | ||

| Social contact | ||||

| In regular contact with friends and family | 70.8 (323) | 29.2 (133) | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| No contact with friends and family | 69.2 (45) | 30.8 (20) | ||

| Safety | ||||

| Felt unsafe since lockdown | 62.3 (96) | 37.7 (58) | * | 0.02 |

| Has not felt unsafe since lockdown | 73.4 (268) | 26.6 (97) | ||

| Exposure to crime | ||||

| Exposed to theft or assault since lockdown | 67.7 (37) | 32.3 (25) | * | 0.04 |

| No exposure to theft or assault | 72.3 (324) | 27.7 (124) |

based on WHO categories (Organisation, 2004) (Eastern Mediterranean countries relevant to this sample: Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia).

Including State Medical Assistance (AME)for undocumented migrants. P-value scores: <0.05 = * ; <0.01 = ** ; <0.001 = ***

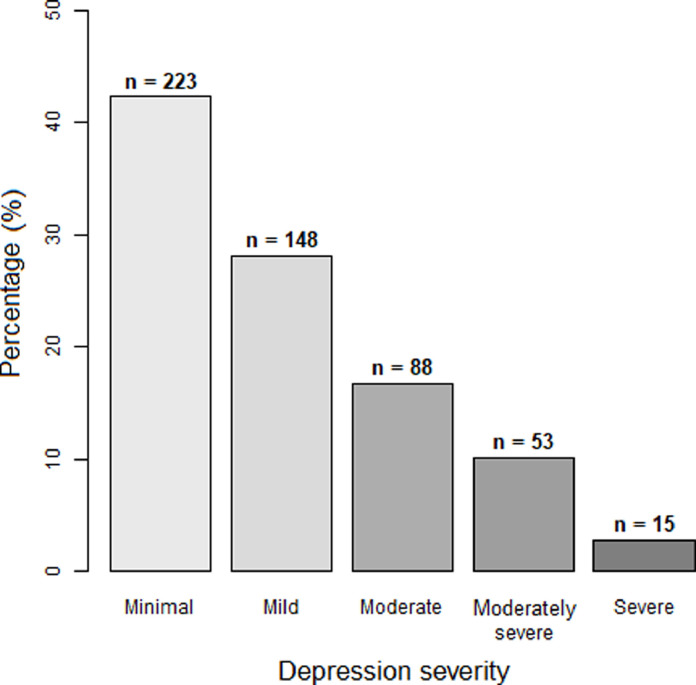

The severity of depression in the ECHO sample is shown in Fig. 1 . Internal consistency between PHQ-9 questions was good (α = 0.82). Less than half of participants (42%) showed no symptoms of depression, 28% had mild symptoms, 17% had moderate symptoms, 10% had moderately severe symptoms and 3% had severe symptoms.

Fig. 1.

The severity of depression amongst ECHO study participants during the Spring 2020 (n = 527), based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Depression categories: Minimal = 0–4; Mild = 5–9; Moderate = 10–14; Moderately Severe = 15–19; Severe 20–27.

3.2. Factors associated with depression

In binary analyses, characteristics associated with depression were being female (p = 0.1), young (p < 0.05), or without a stable partner (p < 0.05) and currently experiencing unemployment (p = 0.2), chronically illness (p < 0.01), food insecurity (p < 0.001) and feelings of unsafety (p < 0.05). Association was also seen for exposure to theft or assault since lockdown (p < 0.05), alongside participants region of origin (p = 0.07), administrative status (p = 0.25) and medical insurance status (p < 0.05).

Collinearity tests revealed significant associations between (a) administrative status and both employment and medical insurance, as well as (b) lack of safety and exposure to theft/assault. Therefore, only participants’ administrative status and lack of safety were retained for the final model.

As shown in Table 2 , in a multivariate regression model, being female (aOR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.26–3.69), chronically ill (aOR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.43: 3.78), food insecure (aOR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.40–3.22) or without a stable partner (aOR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.01–2.52) were risk factors for depression. Lower rates of depression were seen amongst those aged 30–49 (aOR: 0.60; CI: 0.38–0.95) and 50+ (aOR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.13–0.64), when compared to ages 18–29 years.

Table 2.

Factors associated with depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) amongst adults living in temporary and/or emergency accommodation during the initial French lockdown period: ECHO, May-June 2020 (n = 515). Multivariate logistic regression

| n | aOR | CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 391 | 1 | |

| Female | 124 | 2.15 | 1.26-3.69 | |

| Age group | 18-29 | 229 | 1 | |

| 30-49 | 216 | 0.60 | 0.38-0.95 | |

| 50+ | 70 | 0.28 | 0.13-0.64 | |

| Partnership status | Has a stable partner | 185 | 1 | |

| No stable partner | 330 | 1.60 | 1.01-2.52 | |

| Chronic illness | No | 384 | 1 | |

| Yes | 131 | 2.32 | 1.43-3.78 | |

| Food insecurity | No | 311 | 1 | |

| Yes | 204 | 2.12 | 1.40-3.22 | |

| Region of origin | France | 57 | 1 | |

| Africa | 201 | 0.71 | 0.31-1.62 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean1 | 200 | 0.70 | 0.30-1.63 | |

| Europe (ex. France) | 57 | 0.25 | 0.08-0.75 | |

| Administrative status | Residence permit² | 172 | 1 | |

| Asylum seeker | 169 | 1.41 | 0.79-2.52 | |

| No residence permit | 131 | 1.15 | 0.61-2.16 | |

| Other | 43 | 0.98 | 0.40-2.35 | |

| Lack of safety | No | 362 | 1 | |

| Yes | 153 | 1.44 | 0.93-2.23 |

Based on WHO categories (Organisation, 2004) (Eastern Mediterranean countries relevant to this sample: Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia).

Including French citizenship. aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

Compared to French participants, the rate of depression was significantly lower amongst non-French Europeans (aOR: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.08–0.75). Regarding administrative status, compared to persons who were French or had a residence permit, both asylum seekers (aOR: 1.41; 95% CI: 0.79–2.52) and participants without residence permits (aOR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.61–2.16) had higher rates of depression, however neither were significant.

The estimated variance associated with the centre type (n = 18), was 0.01 +/- 0.07, suggesting a negligible effect on depression frequency.

3.3. Worries regarding the pandemic and depression

Associations between rates of depression and participants feelings surrounding the pandemic are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Participants with symptoms of depression had higher levels of worry surrounding coronavirus (p < 0.001), getting sick (p < 0.01), being rejected if sick (p < 0.05), future uncertainty (p < 0.01), isolation (p < 0.001), and access to treatment (p < 0.05) or friends and family (p < 0.01). Worries regarding administrative procedures (p < 0.01) were also seen amongst non-French participants. In comparison to the non-depressed group, depressed participants expressed greater reluctance towards respecting future lockdowns (p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

Within the ECHO study, consisting of homeless persons residing in temporary and/or emergency accommodation during the spring of 2020, 30% had moderate to severe depression. Associated risk factors for depression were being female, single, chronically ill or facing food insecurity. Moreover, persons who were French, or migrating from African or Eastern Mediterranean regions, had higher levels of depression than persons migrating from Europe. Depression was associated with multiple worries and reluctance towards future lockdowns. These findings highlight the frequency of mental health difficulties and the importance of mental health care amongst persons experiencing severe socioeconomic disadvantage, which should be accounted for in strategies aiming to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in vulnerable groups. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies on the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst homeless persons in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

Several limitations which may influence our findings must be acknowledged. Firstly, our study is cross-sectional, making it impossible to establish the longitudinal course of participants' depression or the duration of symptomology. Thus, it may be that participants were already depressed prior to the pandemic. Further analyses using longitudinal samples are necessary to understand the chronology of mental health difficulties within this population, as well as the impact of homelessness on individuals’ symptoms. Secondly, our study population is unrepresentative of France's total homeless population, consisting exclusively of those in temporary accommodation. Persons residing in alternative living situations, such as camps, squats, or the street, were not accounted for. Our findings may therefore disproportionally represent the prevalence of depression within this vulnerable population. Recruitment also consisted primarily of persons residing within two large cities (Paris and Lyon) and surrounding suburbs. Previous research has found increased loneliness during lockdown amongst adults living in urban areas compared to rural environments (Bu et al., 2020b). For this reason, the inclusion of other regions of France would have proven interesting, particularly non-urban areas.

Nevertheless, our sample is balanced and, although based on shelters expanded as a measure against the COVID-19 pandemic, includes persons who were sheltered for both short and long periods. The variety of centres used for recruitment also provided a diverse range of family living situations compared to previous research, which has often focused on solely families (Roze et al., 2020; Vandentorren et al., 2016) or single persons (Roederer et al., 2021).

Another strong point of this study is the use of in-person interviews, which permitted the recruitment of those without access to a computer, smartphone, or internet connection. A key benefit to conducting interviews in person is the associated increase in participant response rate (Bowling, 2005) and the possibility to include participants with low literacy who could not complete self-reported questionnaires. Given the sensitive nature of some of the study questions, this study's low rate of missing data (1.3%) amongst variables used is commendable. Those with lower levels of education have been found to show higher rates of item non-response to health surveys, alongside males being less likely to respond to questions on depression (Tsiampalis and Panagiotakos, 2020); two factors in which this population saw a majority. The use of interpreters for those unable to respond in French or English is also likely to have greatly increased the inclusivity of our dataset. Finally, the ECHO questionnaire design benefitted from collaboration with the organisations managing the shelters included in our study.

4.2. Prevalence of depression

The rate of depression (30%) within the ECHO sample is higher than French national averages calculated within recent years (Gourier-Fréry et al., 2011; Léon et al., 2018; Sapinho et al., 2008) alongside more global estimates (Murray et al., 2012; World Health Organization, 2017). However, research on the rate of depression amongst homeless populations shows figures both higher (Bassuk et al., 1998; Tinland et al., 2018) and lower (Laporte et al., 2018; Vandentorren et al., 2016) than in our study. These disparities may result from differences in methodology. For example, our data collection occurred mostly in Paris and surrounding regions (74% of participants), in which homelessness often results from a lack of affordable housing and is less reflective of severe poverty (Roze et al., 2020). And whilst a Parisian study on homeless mental health observed a depression prevalence of 57% (Rondet et al., 2013), their recruitment took place in a free healthcare clinic. As prior illness is a known risk factor for depression (Chandola et al., 2020; Goodwin, 2006), this elevated prevalence of depression is not surprising. In comparison, our study consisted of persons receiving accommodation after periods of exceptional adversity, considering that 65% of our sample were staying in a camp, squat, or on the street prior to lockdown. This may be reflected in the lower rate of depression. In support of this, depression in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic was found to associate with living conditions (Ramiz et al., 2021).

Despite this, the rate of depression seen was still considerably higher than the French national average during lockdown (approximately 20%) (SantéFrance, 2021). One could argue that the rate of depression in this population might simply demonstrate a brief, transient stage during this period of instability. However, even after treatment, the risk of relapse for depression is high, with research suggesting a 10–80% rate of recurrent episodes (dependant on depression severity) (Holma et al., 2008; Kessler and Bromet, 2013; Kumagai et al., 2019; Köhler et al., 2015; Limosin et al., 2004). Therefore, identifying the risk factors for depression within this population may not only alleviate suffering during equivalent periods of precariousness, but further improve the chance of mental stability in later life. Studies conducted during the pandemic also indicate changes to important predictors for depression; Within the French population, depression was seen to associate with increased alcohol consumption (Guignard et al., 2021) and anxiety (Andersen et al., 2021). These factors are likely to both increase vulnerability to depression and impair rehabilitation.

4.3. Migrant status

The rate of depression amongst French natives was similar to that of African and Eastern Mediterranean participants (32%, 33% and 30%, respectively), and higher than those migrating from Europe (14%). This was surprising, as previous research amongst homeless populations has found depression to be more prevalent amongst migrants than local residents (Rondet et al., 2013). Moreover, despite the “healthy migrant effect”, a recurrent finding that migrants often have better health than native residents (Puschmann et al., 2017), recent data also suggests that migrants may actually be more vulnerable to mental health problems that non-migrants (Aldridge et al., 2018). However, the causes for homelessness are also likely to vary between migrants and local residents. Our findings may then be explained by mental health difficulties increasing the likelihood of being homeless more so within native populations. Whether these rates are due to the pandemic, or our sample consisting of solely those experiencing homelessness, is not possible to establish from our data. However, seeing as the pandemic increased the rate of financial insecurity and unemployment (Johnson et al., 2020), and therefore housing instability (Albon et al., 2020), these factors are likely to confound each other.

4.4. Demographic characteristics

Within our sample, women showed over double the risk for depression than men. It must be noted that depression was self-reported, which has previously been found to enable gender bias due to men underreporting symptoms (Sigmon et al., 2005). However, the association between sex and depression (with increased prevalence amongst women) is one of the most consistent findings amongst recent research, both in France (Fond et al., 2019) and globally (Muñoz et al., 2005; World Health Organization, 2008).

Contrary to pre-pandemic evidence (Arias de la Torre et al., 2021), older participants in our study showed lower rates of depression. Even more paradoxically, previous research has found that depression increased with age during the pandemic in association with higher levels of chronic illness (Chandola et al., 2020). Age is a known predictor of chronic illness (Divo et al., 2014), and within our study chronic illness increased the risk of depression significantly. One potential explanation for our findings may be that older participants felt less impacted by the pandemic. Younger subjects may be more concerned about their career, social life and future in general. Worries surrounding the future were significantly more common in depressed (75.7%) compared to non-depressed (61.2%) participants. Further research is needed to assess how the longitudinal effects of the pandemic differ between age groups. This is of particular relevance to migrants, as European Union statistics have found migrants to be, on average, much younger than a countries native population (Eurostat, 2020). This was echoed by our sample, in which the average age of French nationals was 12 years older than non-French subjects.

Relationship status also associated with depression, with single participants at greater risk. Albeit potentially linked to financial security, the positive effect of having a partner may result from associated comfort or support, thereby preventing loneliness. This is particularly relevant to the pandemic, with lockdown measures not only increasing loneliness (Bu et al., 2020a), but more severely so in those with low socioeconomic status (Bu et al., 2020b; Burchell et al., 2020). Within our population, increased loneliness since the start of lockdown was seen amongst 37% of subjects. This is considerably higher than figures from COVID-19 research on the US adult population, which saw loneliness increase from 11% in 2018 to 13.8% in April 2020 (McGinty et al., 2020). German data collected during spring 2020 also found roughly 50% of homeless persons were experiencing loneliness, compared to 11% of the national population (Bertram et al., 2021). Moreover, depressed participants within our study were significantly more likely to worry about remaining isolated. This may partly explain why depressed subjects were also less willing to accept another lockdown.

4.5. Socioeconomic status (SES)

Food insecurity positively associated symptoms of depression, however job loss did not. This was surprising, as literature on mental health during the pandemic found depression to associate significantly with job loss (Posel et al., 2021). However, our populations’ low rate of employment (27%) is likely to account for this disparity. Recent research on homeless families in Paris found food insecurity to be a major problem, affecting 77% of parents (Vandentorren et al., 2016). Whilst only 39% of our cohort declared food insecurity, as temporary accommodation for both winter and COVID-19 close, this figure is likely to increase. Lower SES has also been found to associate with increased depression during the pandemic (Sadarangani et al., 2021; Xue and McMunn, 2021), alongside greater levels of loneliness (Bu et al., 2020b; Burchell et al., 2020) and anxiety (Jia et al., 2020). Interestingly, several studies show parallel levels of depression between homeless populations and non-homeless cohorts with low SES (Fazel et al., 2005; Laporte et al., 2018). Together, these data demonstrate the evident benefit of reducing poverty to better mental health.

4.6. Health status

Chronic illness was found to significantly increase the rate of depression, which is consistent with other data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic (Riley et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). This is of particular concern for those without medical insurance (33% of the ECHO population), who may face greater difficulty getting treatment for both depression and chronic illness. Data collected from homeless persons during spring 2020 found physical pain to be the most frequent impediment to participants quality of life (47%), followed by depression or anxiety (32%) (van Rüth et al., 2021). Alongside this, psychiatric conditions are likely to confound each other, especially amongst low-income persons (Bassuk et al., 1998). Seeing as the COVID-19 pandemic has also been found to trigger both post-traumatic stress (Wong et al., 2021) and anxiety (Liu et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020), better targeting interventions for those most at-risk for all elements of chronic ill-health will likely support the prevention of depression.

4.7. Future applications

This research has applications relevant not only to the COVID-19 pandemic, but to future periods of mental health disparity resulting from immediate social or health crises. Much of the temporary accommodation this study recruited from, created in response to the pandemic, was, or will soon be, subsequently disbanded (Martin et al., 2020; Naik et al., 2020). The effects this may have on mental health warrant investigation. Moreover, due to data collection occurring in the very first stages of the pandemic, it is possible certain social and financial effects had not yet occurred. This may partly explain the lack of association seen between fiscal worries and depression. Further investigation within this population is needed to explore the relationship between mental health and financial disruption during later stages of the pandemic. We are currently (Spring 2021) conducting a second wave of the ECHO study in a similar population augmented with persons living on the street, to gain better understanding of long-term patterns of health within this population in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Conclusion

Moderate to severe depression was seen in almost a third of homeless persons interviewed, with women, young people, those without stable partners, and chronically unwell or food insecure persons at greatest risk. Increased loneliness was also seen in 37% of subjects since the start of lockdown, alongside higher levels of worry surrounding isolation amongst depressed participants. These findings can teach us about not only health inequalities in the context of COVID-19, but also how similar circumstances may affect the mental health of future populations with comparable disadvantage. Closer attention must be paid to those most at risk, as supporting good mental health within these communities will in turn increase the likelihood of their progression to stable housing and better living conditions in general.

Financial support

This work was supported by the French collaborative Institute on Migration, the French Public Health Agency, the French National Research Agency (ANR, Grant No. ANR-20-COV9–0005–01), and the European Commission Horizon 2020 H2020-SC1-PHE-CORONAVIRUS-2020–2 call (project PERISCOPE, grant no. 101,016,233).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Department of Social Epidemiology, Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all research participants who contributed to this project, as well as ISM interpreters without whom communication with study participants would have been impossible.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100243.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Albon D., Soper M., Haro A. Potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the homeless population. Chest. 2020;158(2):477–478. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge R.W., Nellums L.B., Bartlett S., Barr A.L., Patel P., Burns R., Hargreaves S., Miranda J.J., Tollman S., Friedland J.S., Abubakar I. Global patterns of mortality in international migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2553–2566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen A.J., Mary-Krause M., Bustamante J.J.H., Héron M., El Aarbaoui T., Melchior M. Symptoms of anxiety/depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown in the community: longitudinal data from the TEMPO cohort in France. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):381. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias de la Torre J., Vilagut G., Ronaldson A., Dregan A., Ricci-Cabello I., Hatch S.L., Serrano-Blanco A., Valderas J.M., Hotopf M., Alonso J. Prevalence and age patterns of depression in the United Kingdom. A population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthurs E., Steele R., Hudson M., Baron M., Thombs B. Are scores on english and french versions of the PHQ-9 comparable? An assessment of differential item functioning. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk E.L., Buckner J.C., Perloff J.N., Bassuk S.S. Prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among homeless and low-income housed mothers. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1561–1564. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendel R.B., Afifi A.A. Comparison of stopping rules in forward “stepwise” regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1977;72(357):46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram F., Heinrich F., Fröb D., Wulff B., Ondruschka B., Püschel K., König H.H., Hajek A. Loneliness among homeless individuals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(6):3035. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J. Public Health (Bangkok) 2005;27(3):281–291. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Loneliness during lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 35,712 adults in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.29.20116657. 2020.05.29.20116657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.14.20101360. 2020.05.14.20101360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchell, B., Wang, S., Kamerāde, D., Bessa, I., Rubery, J., 2020. Cut hours, not people: no work, furlough, short hours and mental health during COVID-19 pandemic. In: in the UK. University of Cambridge Judge Business School.

- Bursac Z., Gauss C.H., Williams D.K., Hosmer D.W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagna G. Linking crowding, housing inadequacy, and perceived housing stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016;45:252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Chandola T., Kumari M., Booker C.L., Benzeval M.J. The mental health impact of COVID-19 and pandemic related stressors among adults in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.05.20146738. 2020.07.05.20146738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Ryan L., Kawachi I., Canner M.J., Berkman L., Wright R.J. Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: a mental health hazard for urban women. J. Urban Health. 2008;85(1):22–38. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9229-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divo M.J., Martinez C.H., Mannino D.M. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44(4):1055. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . Eurostat; Luxembourg: 2020. Migration and Migrant Population Statistics. [Online]. (Accessed: [26/02/2021]) [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during enforced isolation due to COVID-19: longitudinal analyses of 59,318 adults in the UK with and without diagnosed mental illness. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20120923. 2020.06.03.20120923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M., Wheeler J., Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1309–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S., Khosla V., Doll H., Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(12):e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaming D., Orlando A., Burns P., Pickens S. Locked out: unemployment and homelessness in the COVID economy. SSRN. 2021 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3765109. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fond G., Lancon C., Auquier P., Boyer L. Prévalence de la dépression majeure en France en population générale et en populations spécifiques de 2000 à 2018 : une revue systématique de la littérature. Presse Méd. 2019;48(4):365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo S.Q., Tam W.W., Ho C.S., Tran B.X., Nguyen L.H., McIntyre R.S., Ho R.C. Prevalence of Depression among Migrants: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(9):1986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliem J., Gliem R. Proceedings of the Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education. 2003. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient for likert-type scales. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin G.M. Depression and associated physical diseases and symptoms. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006;8(2):259–265. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.2/mgoodwin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourier-Fréry C., Guignard R., Beck F. Vol. 23. Santé Publique; Vandoeuvre-Lès-Nancy, France: 2011. pp. S13–S29. (The Current State of Mental Health Surveillance in France). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardia D., Salleron J., Roelandt J.L., Vaiva G. [Prevalence of psychiatric and substance use disorders among three generations of migrants: results from French population cohort] Encephale. 2017;43(5):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignard R., Andler R., Quatremère G., Pasquereau A., du Roscoät E., Arwidson P., Berlin I., Nguyen-Thanh V. Changes in smoking and alcohol consumption during COVID-19-related lockdown: a cross-sectional study in France. Eur. J. Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren M., Wittmann L., Ehlert U., Schnyder U., Maier T., Müller J. Psychopathology and resident status - comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Compr. Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):818–825. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández D. Affording housing at the expense of health: exploring the housing and neighborhood strategies of poor families. J. Fam. Issues. 2016;37(7):921–946. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14530970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holma K.M., Holma I.A., Melartin T.K., Rytsälä H.J., Isometsä E.T. Long-term outcome of major depressive disorder in psychiatric patients is variable. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):196–205. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S., Sturdivant R.X. Vol. 398. John Wiley & Sons; 2013. (Applied Logistic Regression). [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S. Wiley; 2002. Applied Survival analysis: Regression Modelling of Time to Event Data. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.M., Sultana A., Tasnim S., Fan Q., Ma P., McKyer E.L.J., Purohit N. Prevalence of mental disorders among people who are homeless: an umbrella review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66(6):528–541. doi: 10.1177/0020764020924689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F.Y., Chung H., Kroenke K., Delucchi K.L., Spitzer R.L. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006;21(6):547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE), & Institut national d'études démographiques (INED) ADISP-CMH; 2012. Enquête Auprès Des Personnes Fréquentant Les Services D'hébergement Et Les Distributions De Repas Chauds. [Google Scholar]

- Jia R., Ayling K., Chalder T., Massey A., Broadbent E., Coupland C., Vedhara K. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: early observations. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.14.20102012. 2020.05.14.20102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.T., Johnson E.A., Webber L., Nettle D. Mitigating social and economic sources of trauma: the need for universal basic income during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S191–S192. doi: 10.1037/tra0000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Bromet E.J. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2013;34:119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S., Wiethoff K., Ricken R., Stamm T., Baghai T.C., Fisher R., Seemüller F., Brieger P., Cordes J., Malevani J., Laux G., Hauth I., Möller H.J., Zeiler J., Heinz A., Bauer M., Adli M. Characteristics and differences in treatment outcome of inpatients with chronic vs. episodic major depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;173:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Tajika A., Hasegawa A., Kawanishi N., Horikoshi M., Shimodera S., Kurata K.i., Chino B., Furukawa T.A. Predicting recurrence of depression using lifelog data: an explanatory feasibility study with a panel VAR approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):391. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2382-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte A., Vandentorren S., Détrez M.A., Douay C., Le Strat Y., Le Méner E., Chauvin P., Group T.S.R. Prevalence of mental disorders and addictions among homeless people in the greater paris area, France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(2):241. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léon C., Chan Chee C., Du Roscoät E., Andler R., Cogordan C., Guignard R., Robert M. Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire; 2018. La Dépression En France chez Les 18–75 ans: Résultats du Baromètre santé 2017; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liddell C., Guiney C. Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being. Public Health. 2015;129(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima N.N.R., de Souza R.I., Feitosa P.W.G., Moreira J.L.d.S., da Silva C.G.L., Neto M.L.R. People experiencing homelessness: their potential exposure to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limosin F., Loze J.Y., Zylberman-Bouhassira M., Schmidt M.E., Perrin E., Rouillon F. The course of depressive illness in general practice. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2004;49(2):119–123. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindert J., Ehrenstein O., Priebe S., Mielck A., Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;69:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.H., Zhang E., Wong G.T.F., Hyun S. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manea L., Gilbody S., McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012;184(3):E191–E196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Andrés P., Bullón A., Villegas J.L., de la Iglesia-Larrad J.I., Bote B., Prieto N., Roncero C. COVID pandemic as an opportunity for improving mental health treatments of the homeless people. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020950770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Frontiers in Econometrics. Academic Press, New York. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickey R.M., Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz M., Crespo M., Pérez-Santos E. Homelessness effects on men's and women's health. Int. J. Ment. Health. 2005;34(2):47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J., Vos T., Lozano R., Naghavi M., Flaxman A.D., Michaud C., Ezzati M., Shibuya K., Salomon J.A., Abdalla S. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S.S., Gowda G.S., Shivaprakash P., Subramaniyam B.A., Manjunatha N., Muliyala K.P., Reddi V.S.K., Kumar C.N., Math S.B., Gangadhar B.N. Homeless people with mental illness in India and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(8):e51–e52. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannetier J., Lert F., Jauffret Roustide M., du Loû A.D. Mental health of sub-saharan african migrants: the gendered role of migration paths and transnational ties. SSM Popul. Health. 2017;3:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Fondation Abbé Pierre, 2018.Third overview of housing exclusion in Europe 2018. FEANTSA, Brussels, Belgium.

- Posel D., Oyenubi A., Kollamparambil U. Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: evidence from South Africa. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puschmann P., Donrovich R., Matthijs K. Salmon bias or red herring?: Comparing adult mortality risks (Ages 30-90) Between natives and internal migrants: stayers, returnees and movers in rotterdam, the Netherlands, 1850–1940. Hum. Nat. 2017;28(4):481–499. doi: 10.1007/s12110-017-9303-1. Hawthorne, N.Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiz L., Contrand B., Rojas Castro M.Y., Dupuy M., Lu L., Sztal-Kutas C., Lagarde E. A longitudinal study of mental health before and during COVID-19 lockdown in the French population. Global. Health. 2021;17(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00682-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E.D., Dilworth S.E., Satre D.D., Silverberg M.J., Neilands T.B., Mangurian C., Weiser S.D. Factors associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety among women experiencing homelessness and unstable housing during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roederer T., Mollo B., Vincent C., Nikolay B., Llosa A.E., Nesbitt R., Vanhomwegen J., Rose T., Goyard S., Anna F., Torre C., Fourrey E., Simons E., Hennequin W., Mills C., Luquero F.J. Seroprevalence and risk factors of exposure to COVID-19 in homeless people in Paris, France: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(4):e202–e209. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00001-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondet C., Cornet P., Kaoutar B., Lebas J., Chauvin P. Depression prevalence and primary care among vulnerable patients at a free outpatient clinic in Paris, France, in 2010: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013;14(1):151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Socci V., Talevi D., Mensi S., Niolu C., Pacitti F., Di Marco A., Rossi A., Siracusano A., Di Lorenzo G. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11(790) doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze M., Melchior M., Vuillermoz C., Rezzoug D., Baubet T., Vandentorren S. Post-traumatic stress disorder in homeless migrant mothers of the Paris region shelters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(13):4908. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadarangani T., Zhong J., Vora P., Missaelides L. Advocating every single day” so as not to be forgotten: factors supporting resiliency in adult day service centers amidst COVID-19-related closures. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2021.1879339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SantàFrance, Publique, 2021. CoviPrev: A survey to track changes in behavior and mentalhealth during the COVID-19 epidemic. Santé Publique France, Paris, France.

- Sapinho D., Chan-Chee C., Briffault X., Guignard R., Beck F. Mesure de l’épisode dépressif majeur en population générale: apports et limites des outils. Bull. Épidémiol. Hebd. 2008;35:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M., McBride O., Murphy J., Miller J.G., Hartman T.K., Levita L., Mason L., Martinez A.P., McKay R., Stocks T.V.A., Bennett K.M., Hyland P., Karatzias T., Bentall R.P. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(6):e125. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigdel A., Bista A., Bhattarai N., Pun B.C., Giri G., Marqusee H., Thapa S. Depression, anxiety and depression-anxiety comorbidity amid covid-19 pandemic: an online survey conducted during lockdown in Nepal. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.30.20086926. 2020.04.30.20086926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon S.T., Pells J.J., Boulard N.E., Whitcomb-Smith S., Edenfield T.M., Hermann B.A., LaMattina S.M., Schartel J.G., Kubik E. Gender differences in self-reports of depression: the response bias hypothesis revisited. Sex Roles. 2005;53(5):401–411. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-6762-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia S.F., Duarte C.S., Sandel M.T. Housing quality, housing instability, and maternal mental health. J. Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1105–1116. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9587-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swope C.B., Hernández D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: a conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;243 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinland A., Boyer L., Loubière S., Greacen T., Girard V., Boucekine M., Fond G., Auquier P. Victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder in homeless women with mental illness are associated with depression, suicide, and quality of life. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018;14:2269–2279. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s161377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiampalis T., Panagiotakos D.B. Missing-data analysis: socio- demographic, clinical and lifestyle determinants of low response rate on self- reported psychological and nutrition related multi- item instruments in the context of the ATTICA epidemiological study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020;20(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udedi M., Muula A.S., Stewart R.C., Pence B.W. The validity of the patient health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2062-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S., Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3) [Google Scholar]

- van Rüth V., König H.H., Bertram F., Schmiedel P., Ondruschka B., Püschel K., Heinrich F., Hajek A. Determinants of health-related quality of life among homeless individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2021;194:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandentorren S., Le Méner E., Oppenchaim N., Arnaud A., Jangal C., Caum C., Vuillermoz C., Martin-Fernandez J., Lioret S., Roze M., Le Strat Y., Guyavarch E. Characteristics and health of homeless families: the ENFAMS survey in the Paris region, France 2013. Eur. J. Public Health. 2016;26(1):71–76. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizard T., Davis J., White E., Beynon B. Office for National Statistics; Great BritainLondon: 2020. Coronavirus and Depression in Adults. June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.M.Y., Hui C.L.M., Wong C.S.M., Suen Y.N., Chan S.K.W., Lee E.H.M., Chang W.C., Chen E.Y.H. Prospective prediction of PTSD and depressive symptoms during social unrest and COVID-19 using a brief online tool. Psychiatry Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Heath Organization (WHO) World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. List of Member States. [Google Scholar]

- World Heath Organization (WHO) World Health Organization; 2008. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. [Google Scholar]

- World Heath Organization (WHO) World Health Organization; 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Jia X., Shi H., Niu J., Yin X., Xie J., Wang X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;281:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B., McMunn, A, 2021. Gender differences inthe impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK. PLoS One 16(3), e0247959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yaouancq F., Duée M. France Portrait Social; 2014. Les Sans-Domicile En 2012: Une Grande Diversité De Situations. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Department of Social Epidemiology, Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.