Abstract

This experiment was conducted to investigate the effects of partial replacement of steam-flaked corn (SFC) with shredded sugar beet pulp (SBP) in the starter diet on selective intake (sorting), feeding and chewing behavior, blood biochemical parameters, and growth in newborn female Holstein dairy calves. A total of 48 calves (3 d old; 40.1 ± 0.84 kg body weight; mean ± SE) were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 feeding treatments containing 0 or 25% SBP (percentage of dry matter [DM]) in the starter diet. Calves were weaned on d 61 and remained in the study until d 81. Intake of starter feed and total intake of DM (milk DM + starter feed DM), crude protein, and neutral detergent fiber were increased (P < 0.05) by feeding SBP; however, intake of starch (P < 0.01) and total intake of ether extract (P = 0.03) were decreased with no apparent effect on total intake of ME. Average daily gain, feed efficiency, final weight, and skeletal growth also showed no significant changes. Circulating concentrations of glucose, total protein, and albumin were not affected by partial replacement of SBP with SFC; however, higher concentrations of blood urea-N (P = 0.01) and a lower albumin-to-globulin ratio (P = 0.03) were observed in SBP- vs. SFC-fed calves. Calves fed SBP sorted more for particles retained on the 4.75-mm sieve (P = 0.02) and against particles retained on the 0.6-mm sieve and bottom pan (P < 0.01). Intake of neutral detergent fibers and starch from particles retained on all sieve fractions was increased and decreased (P < 0.01), respectively, by replacing SFC with SBP. Replacement of SBP with SFC was associated with increased meal length and meal size and increased rumination frequency and length, but decreased intervals between rumination (P ≤ 0.01). Calves fed SBP spent more time eating, rumination, and standing and less time lying and non-nutritive oral behaviors (P < 0.01). In general, 25% replacement of SFC with SBP did not affect calf performance but increased time spent rumination and eating and decreased non-nutritive oral behaviors.

Keywords: Heifer raising, Selective consumption, Weight gain, Dairy calf, Sugar beet pulp

1. Introduction

The effects of variation in the physical form of starter diets (Pazoki et al., 2017; Omidi-Mirzaei et al., 2018) and different nutrient sources (Mirzaei et al., 2016; Moeinoddini et al., 2017; Kargar and Kanani, 2019) on rumen development and growth performance of dairy calves are well documented to develop new solid feed feeding strategies for calves before or after weaning. The main source of energy is cereal grains, which constitute a large proportion of calf starter diets when supplemented with starch (Habibi et al., 2019; Kargar et al., 2019). Feeding easily fermentable carbohydrates to dairy calves can increase the proportional production of propionate and butyrate in the rumen and stimulate rumen epithelial development (Beiranvand et al., 2014). However, dairy calves consuming grain-based starters were found to be at increased risk of sub-acute rumen acidosis and reduced calf performance (Gelsinger et al., 2020). Among the acceptable substitutes for cereal grains (corn and barley), beet pulp and citrus pulp have been used as energy sources for dairy calves on restricted milk diets from early life (Laarman et al., 2012; Maktabi et al., 2016; Oltramari et al., 2018). Beet pulp contains highly digestible dietary fiber (40.6% of dry matter [DM]; Kargar and Kanani, 2019; Naderi et al., 2019) and pectic substances (23.5% of DM; NRC, 2001), which are highly digestible in the rumen and can be used to provide fermentable dietary fiber. In addition, the high cation exchange capacity and K content of beet pulp (McBurney et al., 1983; NRC, 2001) can buffer organic acids produced during rumen fermentation (Marounek et al., 1985). Substitution of beet pulp with grain or corn silage has been shown to be effective in reducing dietary starch content and improving rumen fluid pH, rumen health, and feeding behavior in lactating (Asadi-Alamouti et al., 2009; Pang et al., 2018; Naderi et al., 2019) or non-lactating (Mahjoubi et al., 2009) dairy cows. From a sustainable production perspective, there is potential to use beet pulp as a fermentable non-forage fiber source to improve feed costs and animal health; however, the nutritional and behavioral value of shredded sugar beet pulp (SBP) as a replacement for grain in starter diets of dairy calves has yet to be determined. This is because feeding behavior can influence rumen health and digestion and therefore animal performance.

In an earlier study, Murdock and Wallenius (1980) found no difference in weight gain of calves fed a diet containing 34% SBP for the first 3 months of life. In another study, Maktabi et al. (2016) fed a starter diet containing SBP (10% of the diet DM; as a replacement for mainly barley grain) and observed improved feed intake and weight gain before weaning; however, the benefit in weight gain was not observed when calves were fed SBP at 20% of the diet DM, which was due to lower intake of starter feed. Recently, Dennis et al. (2018) reported lower weight and skeletal gain in weaned dairy calves fed high-concentration (corn-based) diets containing SBP (up to 30% of the diet DM). To our knowledge, there are very little data on the effects of feeding SBP early in life on calf performance and behavior, especially during the pre-weaning period. Therefore, the objectives of the present experiment were to characterize dairy calf responses to selective intake, feeding, and chewing behavior, selected blood traits, and growth on SBP as a replacement for SFC (at 25% of the diet DM) in the initial feeding. Beet pulp as a fermentable non-forage fiber source has the potential to enable the formulation of high neutral detergent fiber (NDF), high energy density diets (Maktabi et al., 2016; Naderi et al., 2019), and its inclusion in starter diets may minimize the negative effects of increased starch fermentation without increasing the filling effect of the diet to the level commonly observed in forages (Maktabi et al., 2016). Accordingly, it was hypothesized that reducing dietary starch content by partially replacing SFC with SBP would not have negative effects on growth performance but could alter the feeding and chewing behavior of dairy calves.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Calves, treatments, and management

This study was conducted in Ali-Naghian Dairy Complex, Isfahan, Iran. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shiraz University (Shiraz, Iran) according to the Iranian Council of Animal Care (1995). Newborn calves were assigned to individual pens for 12 consecutive days (4 calves daily; 2 calves/treatment per day). A total of 48 female Holstein calves (3 d old; 40.1 ± 0.84 kg body weight [BW]; mean ± SE) were randomly housed in an open-sided barn with individual pens (1.6 m × 1.4 m × 1.1 m; length × width × height). Fresh wood shavings were used as bedding and replenished daily, and manure was disposed of daily to keep pens visibly clean and dry. Calves consumed 7.0 L of colostrum within the first 2 h of life (3.5 L) and 8 h after the first feeding (3.5 L). On the second day of life, calves received transition milk (6 L) in 2 equally sized meals (09:00 and 19:00). From d 3 of life, calves were individually fed milk replacer (adjusted to 12.5% DM; 6 L/d from d 1 to 56, 4 L/d from d 57 to 58, and 2 L/d from d 59 to 60 of the study; containing 22% crude protein [CP] and 19.5% crude fat on a DM basis) in steel buckets in 2 meals of equal volume daily (at 09:00 and 19:00). Animals were assigned to a dietary treatment containing either 0 or 25% SBP (percentage of diet DM) in the starter diet. All calves were weaned on d 61 and remained in the experiment until d 81. No forage source was fed to the calves during the experimental period. Table 1 shows the ingredients and nutrient composition of the experimental feed ingredients, diets, and their particle distributions.

Table 1.

Ingredients and chemical composition (% of DM unless otherwise noted) of the experimental diets as well as their physical characteristics.

| Item | Ingredients |

Starter diet1 |

P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn grain | Soybean meal | SBP | SFC | SBP | SEM | ||

| Ingredient composition | |||||||

| Corn grain, steam-flaked2 | 65.7 | 43.5 | |||||

| Shredded beet sugar pulp, dried | 25.0 | ||||||

| Soybean meal | 30.4 | 28.0 | |||||

| Vitamin and mineral mixture3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |||||

| Calcium carbonate | 1.4 | 1.0 | |||||

| Salt | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||||

| Chemical composition | |||||||

| Dry matter (DM) | 89.0 | 91.0 | 94.6 | 90.0 | 91.4 | ||

| Crude protein (CP) | 8.3 | 48.0 | 11.7 | 20.0 | 20.0 | ||

| Non-fibrous carbohydrate (NFC)4 | 76.4 | 31.5 | 39.9 | 61.9 | 54.0 | ||

| Starch | 79.1 | 31.2 | 3.0 | 42.7 | 29.3 | ||

| Sugar | 20.9 | 31.2 | 36.5 | 13.5 | 13.3 | ||

| Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) | 9.5 | 11.5 | 40.1 | 9.7 | 17.4 | ||

| Ether-extract (EE) | 4.2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 2.6 | ||

| Ash | 1.6 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 5.1 | 5.9 | ||

| Calcium | 0.70 | 0.75 | |||||

| Phosphorus | 0.41 | 0.35 | |||||

| Metabolizable energy, Mcal/kg of DM | 3.26 | 3.07 | |||||

| DM retained on sieves, % | |||||||

| 4.75 mm | 48.5 | 47.6 | 3.74 | 0.86 | |||

| 2.36 mm | 21.4 | 23.5 | 1.76 | 0.44 | |||

| 1.18 mm | 13.2 | 14.5 | 0.84 | 0.33 | |||

| 0.6 mm | 9.6 | 8.5 | 0.87 | 0.44 | |||

| Pan | 7.3 | 5.9 | 1.52 | 0.54 | |||

| pef>2.365 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.63 | |||

| pef>1.185 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 0.32 | |||

| pef>0.65 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.46 | |||

| peNDF>2.365 | 7.0 | 12.8 | 0.38 | <0.01 | |||

| peNDF>1.185 | 8.2 | 14.7 | 0.26 | <0.01 | |||

| peNDF>0.65 | 8.8 | 15.9 | 0.17 | <0.01 | |||

| Xgm,6 mm | 3.0 | 3.1 | 0.16 | 0.68 | |||

| SDgm,7 mm | 2.6 | 2.5 | |||||

SFC: starter diet containing SFC (65.7% of DM) without SBP; SBP: starter diet containing SBP (25% of DM) as replacement for SFC (43.5% of DM).

Flake density ≈ 550 g/L.

Contained per kilogram of supplement: 1,000,000 IU of vitamin A, 20,000 IU of vitamin D, 10,000 IU of vitamin E, 100 mg of vitamin B7, 245,000 mg of Ca, 180,690 mg of Zn, 18,350 mg of Mg, 14,000 mg of Mn, 4,665 mg of Cu, 200 mg of I, 100 mg of Co, 76 mg of Se, and 2,000 mg of monensin.

NFC = 100 - (CP + NDF + EE + Ash); ME = Total digestible nutrients × 0.04409 × 0.82; both calculated according to NRC (2001).

pef>2.36, 1.18, and 0.6: physical effectiveness factor determined as the proportion of particles retained on 2 (4.75 and 2.36 mm), 3 (4.75, 2.36, and 1.18 mm), and 4 (4.75, 2.36, 1.18, and 0.6 mm) sieves; peNDF>2.36, 1.18, and 0.6: physically effective neutral detergent fiber (NDF) determined as the NDF concentration of the starter feed retained on each sieve multiplied by pef>2.36, 1.18, and 0.6, respectively.

Geometric mean particle size (Xgm), calculated according to ASAE (1995) method S424.1.

Geometric standard deviation of particle size (SDgm), calculated according to ASAE (1995) method S424.1.

2.2. Growth and skeletal measurements

Calves were weighed at the beginning of the experiment and 10-d intervals thereafter before morning feeding, and average daily gain (ADG; kg BW/d) was calculated as the difference between BW recorded at 10-d intervals divided by 10. Feed efficiency (FE) was calculated as kilogram BW again per total DM intake (DMI; milk replacer DM + starter feed DM) or total intake ME. Body measurements, including heart girth (circumference of chest), withers height (distance from base of front feet to withers), body length (distance between points of shoulder and rump), body barrel (circumference of the paunch before feeding), hip height (distance from the base of the hind feet to the hook bones) and hip-width (distance between the points of the hook bones) of the calves were recorded at the beginning of the experiment and every 10 d thereafter according to Kargar and Kanani (2019).

2.3. Feed sampling and analyses

To determine the individual feed intake of each calf, the weight of starter feed offered and refused (collected daily at 09:00 before fresh starter feed was issued) was recorded daily. Representative samples of baseline starter feed (n = 8; pooled by diet within the experimental period) and individual refusals (n = 8 per calf; pooled by calf within treatment every 10 d) were collected immediately prior to morning feeding every 10 d during the study to measure DM and chemical analyses. A forced-air oven was used to quantify the DM concentration of the samples by drying at 100 °C for 24 h (AOAC International, 2002; Method 925.40). After mixing, the samples were ground in a Wiley mill (Ogawa Seiki Co., Ltd.) to a point where they passed a 1-mm sieve, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed in triplicate at CP using the Kjeldahl method (Kjeltec 1030 Auto Analyzer, Tecator, Höganäs, Sweden; AOAC International, 2002; Method 955.04), ether extract (EE; AOAC International, 2002; Method 920.39), crude ash (AOAC International, 2002; Method 942.05), NDF with a heat-stable α-amylase (100 μL in 0.5 g sample) and sodium sulfite (Van Soest et al., 1991), and sugars and starches (Hall et al., 1999). The percentage of non-fibrous carbohydrates (NFC) was calculated as 100 - (CP + NDF + ether extract + ash) (NRC, 2001).

For particle size separation, additional samples of the basal starter diet (n = 8; 1 sample per starter diet every 10 d over the experimental period) and individual refusals (n = 3; pooled by calf every 10 d over the experimental period starting on d 51 until the end of the experimental period) were collected and separated into 5 fractions using a 4-sieve (4.75, 2.36, 1.18, and 0.6 mm) particle separator (model 120; Automatic Sieve Shaker, Techno Khak, Khavaran, Tehran, Iran) (Beiranvand et al., 2019). After sieving, the DM concentration of the individually separated fraction was determined by drying at 100°C in a forced-air oven for 24 (AOAC International, 2002; Method 925.40). The physical effectiveness factor (pef) was calculated as the DM proportion of particles retained on sieves 2 (pef >2.36), 3 (pef >1.18), and 4 (pef >0.6). The physically effective NDF of sieves 2 (peNDF >2.36), 3 (peNDF >1.18), and 4 (peNDF >0.6) was calculated by multiplying the NDF concentration of the feed retained on each sieve by the fraction of pef >2.36, pef >1.18, and pef >0.6, respectively. The geometric mean particle size of the starter feeds was calculated according to ASAE (1995; Method S424.1).

2.4. Feed preference and chewing behavior

To determine if the calves sorted the starter feed for each particle size fraction, a sorting index was established per calf per 10 d, beginning on d 51 and continuing until the end of the experiment. The sorting index was calculated as the ratio of actual intake to expected intake for particles retained on each sieve (Leonardi and Armentano, 2003). The predicted intake of a single fraction was calculated as the product of the DMI of the total feed multiplied by the DM percentage of that fraction in the starter feed fed. Values equal to 100% indicated no sorting, 100% indicated selective refusals (sorting against), and 100% indicated preferential intake (sorting for).

All calves were visually observed (every 5 min) for eating, rumination, resting, standing, lying, drinking, and non-nutritive oral behaviors (NNOB; when the animal licked any surface, or consumed wood-shavings, etc.) for a period of 6 h (between 09:00 and 15:00) once on 3 consecutive days before weaning (d 46 to 48 of the study) and once on 3 consecutive days after weaning (d 78 to 80 of the study; Kargar and Kanani, 2019). An observation of (at least) eating activity that occurred after at least 5 min without eating was considered an eating period. Meal frequency was defined as the number of bouts during a 6-h period. Meal duration (min/meal) was calculated as the time from the start of the first feeding event to an interval between events averaged for each calf. Inter-feeding event intervals (min) were calculated from the end of feeding event to the beginning of the next and averaged for each calf. Meal size (g DMI of starter feed during a 6-h period/number of meals during the given period) was the total amount of DMI of starter diet ingested during each meal. Rumination pattern was calculated using the same procedure.

2.5. Blood sampling and analyses

Four h after morning feeding, calves were bled from the jugular vein, and samples were collected in vacuum serum separation tubes (BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing spray-coated silica at baseline and every 10 d thereafter throughout the study period. Samples were immediately placed on an ice pack for further processing in the laboratory. Samples were then immediately centrifuged (1,006 × g for 20 min at 4 °C), and 1.5 mL of serum was decanted into 2-mL microtubes and immediately transferred to −20 °C for upcoming analyses. The concentrations of blood metabolites were determined spectrophotometrically (UNICCO, 2100, Zistchemi, Tehran, Iran) using commercially available kits (Pars Azmoon Co., Tehran, Iran; catalog numbers: Glucose (1-500-017), Blood Urea N (1-400-029), Total Protein (1-500-028), and Albumin (1-500-001)) determined according to the manufacturer's instructions. Globulin concentrations were determined by subtracting albumin from total protein.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Data on daily nutrient intake and growth performance, skeletal gain (d 1 to 81), feeding and chewing behavior, sorting activity and actual particle size fraction intakes of nutrient (d 51 to 81), and blood variables (d 1 to 81) were subjected to ANOVA using the MIXED procedure of SAS with times (1- or 10-d period) as repeated measures. Data were checked for normality before analyses using the UNIVARIATE procedure (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Data (blood metabolites) not being normally distributed were transformed logarithmically. Calf was considered as a random effect, and birth order of calves, treatment (Treat; the partial replacing SFC with SBP), Period (1- or 10-d period), Treat × Period, as fixed effects. Three variance-covariance structures (auto-regressive type 1, compound symmetry, and Toeplitz) were tested, and the auto-regression structure (type 1) with minimized Akaike information criterion (AIC) was accordingly modeled. The SLICE statement of the MIXED procedure (PROC MIXED) of SAS was used to conduct partitioned analyses of the LSM for interaction between Treat and Period when required. Initial BW, blood variables, and starter feed DMI were used as covariates in the BW, blood metabolites, and ADG models, respectively. To test whether sorting occurred, sorting activity for each fraction was tested for a difference from 100% using the t-test procedure of SAS. Also, data for particle size distribution, pef, peNDF of starter feed diets, and geometric mean particle size were analyzed by including a starter feed diet as a fixed effect and period as a random effect. The threshold of significance was set at P ≤ 0.05; trends were declared at 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Intake and growth performance

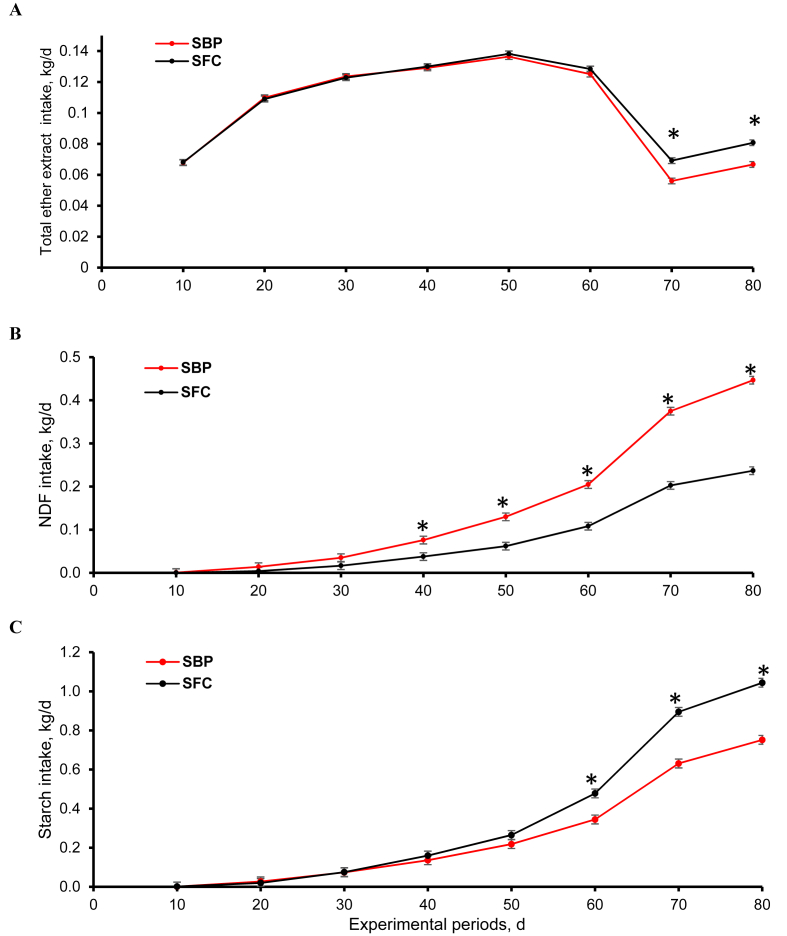

Partial replacement of SBP with SFC was associated with increased intake of starter diet DM (P = 0.03), total DMI (P = 0.03), total CP (P = 0.03), and NDF (P < 0.01), but with decreased intake of total ether extract (P = 0.03) and starch (P < 0.01), and with no apparent effect on total intake ME (mean 5.22 Mcal/d across all groups; Table 2). Diet and time interacted (P < 0.01) to affect total intake of ether extract (d 70 and 80; Fig. 1A), NDF (from d 40 to 80; Fig. 1B), and starch (from d 60 to 80; Fig. 1C). The lower intake of starch and total EE, but higher NDF contents in SBP than in SFC calves might be due to the lower starch and EE, but higher NDF contents in the SBP diet than in the SFC diet along with the differences in starter intake. The present result on starter feed intake does not agree with the findings of Dennis et al. (2018) who found comparable starter feed intake in weaned calves fed SBP (15% and 30% based on an as-fed basis) in highly concentrated diets compared to those fed SFC diets. In addition, Maktabi et al. (2016) reported no differences in starter feed intake of dairy calves up to 7 weeks of age fed 10% (vs 0) SBP diets. A possible reason for this discrepancy between experiments could be the level of supplementation of BP and time devoted to eating, as well as differences in ingredient particle size and processing of starter diets (cracked, rolled, or steam-flaked).

Table 2.

Nutrient intake and growth performance influenced by partial substitution of shredded beet pulp (SBP) for steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in female Holstein dairy calves (n = 24).

| Item | Treatment (Treat)1 |

SEM |

P-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC | SBP | Treat | Period | Treat × Period | ||

| Starter feed DM intake, kg/d | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| Total DMI, kg/d | 1.37 | 1.44 | 0.02 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| Total ME intake, Mcal/d | 5.20 | 5.25 | 0.07 | 0.68 | <0.01 | 0.95 |

| Total CP intake, kg/d | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.004 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| Total ether extract intake, kg/d | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NDF intake, kg/d | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.003 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NFC intake, kg/d | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.07 | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Starch intake, kg/d | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.008 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sugar intake, kg/d | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.003 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Average daily gain (ADG), kg/d | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.63 | <0.01 | 0.54 |

| ADG/total DM intake2 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.63 | <0.01 | 0.60 |

| ADG/total ME intake2 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.003 | 0.22 | <0.01 | 0.80 |

| Overall BW, kg | 94.0 | 95.3 | 1.90 | 0.63 | ─ | ─ |

| Heart-girth gain, cm | 27.9 | 27.0 | 0.85 | 0.48 | ─ | ─ |

| Withers-height gain, cm | 23.8 | 22.6 | 0.62 | 0.13 | ─ | ─ |

| Body-length gain, cm | 16.0 | 16.5 | 0.54 | 0.40 | ─ | ─ |

| Body-barrel gain, cm | 40.6 | 38.5 | 1.21 | 0.25 | ─ | ─ |

| Hip-height gain, cm | 22.2 | 21.2 | 0.54 | 0.19 | ─ | ─ |

| Hip-width gain, cm | 14.4 | 14.8 | 0.32 | 0.36 | ─ | ─ |

SEM = standard error of the mean; DM = dry matter; Total DMI = total DM intake; ME = metabolizable energy; CP = crude protein; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; NFC = non-fibrous carbohydrate.

SFC: starter diet containing SFC (65.7% of DM) without SBP; SBP: starter diet containing SBP (25% of DM) as replacement for SFC (43.5% of DM).

Feed efficiency was calculated by dividing average daily gain by average total DM intake (milk replacer DM + starter feed DM) or total ME intake (milk replacer ME + starter feed ME).

Fig. 1.

Intake of (A) total ether extract (SEM = 0.001; effects in the model: treatment (Treat), P = 0.03; Period, P < 0.01; Treat × Period, P < 0.01), (B) neutral detergent fiber (NDF; SEM = 0.003; effects in the model: Treat, P < 0.01; Period: P < 0.01, Treat × Period, P < 0.01) and (C) starch (SEM = 0.008; effects in the model: Treat, P < 0.01; Period, P < 0.01; Treat × Period, P < 0.01) influenced by partial substitution of shredded beet pulp (SBP) for steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in female Holstein dairy calves (n = 24). For each time point, ∗ denotes a significant difference at P ≤ 0.05. SEM = standard error of the mean.

Although partial replacement of SBP with SFC was associated with higher starter feed intake and total DMI in the current study, ME intake was unaffected, resulting in similar calf ADG and skeletal growth (Table 2). Although we did not evaluate nutrient digestibility of rumen volatile fatty acid profile in the present study, it was shown, that feeding 10% (vs. 0) beet pulp or 32% and 64% citrus pulp (as a replacement for a grain source) to newborn Holstein dairy calves did not affect nutrient digestibility, rumen fluid pH, or total volatile fatty acid profile, and thus did not affect overall performance (Maktabi et al., 2016; Oltramari et al., 2018). This result contradicts that of Dennis et al. (2018) who reported that calf ADG and change in hip-width decreased linearly with increasing SBP (from 0 to 30%) by decreasing the digestibility of the diet. Dennis et al. (2018) fed an additional 5% chopped grass hay in their starter diet, sufficient effective fiber may have already been provided such that increasing beet pulp did not improve calf performance. The feed efficiency and final BW were not affected by partial replacement of SBP with SFC in the present work, which is consistent with Dennis et al. (2018) who found no differences in feed efficiency or final BW of calves fed SBP vs. SFC diets.

3.2. Blood metabolites

Blood concentrations of glucose, total protein, and albumin were not affected by partial replacement of SBP with SFC; however, calves receiving SBP had higher concentrations of BUN (P = 0.01) and lower albumin/globulin ratios (P = 0.03) compared with calves receiving SFC (Table 3). Blood concentration of BUN reflects the balance between dietary energy and nitrogen for microbial protein synthesis (Habibi et al., 2019). The concentration of BUN decreases when the amount of fast fermenting carbohydrates increases (DePeters and Cant, 1992; Habibi et al., 2019). The lower concentration of BUN, observed for SFC could be related to better release of energy (synchronized) for bacterial utilization due to higher ruminal fermentability of starch and consequently lower BUN in calves fed SFC compared to SBP. In the present study, the lower BUN concentrations in calves fed SFC compared with SBP diets might reflect lower CP or higher starch intake, and thus, uptake N with higher efficiency; however, we did not perform measurements of ruminal NH3–N or microbial protein synthesis to substantiate the observed effect. In addition, partial replacement of corn grain with sucrose in dairy cow diets has been reported to tend to increase (Penner and Oba, 2009) or BUN (McCormick et al., 2001). Data from the present study suggest that partial replacement of starch with sugar beet pulp does not necessarily improve N utilization. However, no similar published data are available for comparison.

Table 3.

Blood metabolites influenced by partial substitution of beet pulp (BP) for steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in Holstein dairy calves (d 1 to 81, n = 24).

| Item | Treatment (Treat)1 |

SEM |

P-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC | SBP | Treat | Period | Treat × Period | ||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 90.2 | 89.1 | 2.22 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 22.4 | 23.8 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.37 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 5.60 | 5.68 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.39 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.80 | 3.76 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| Globulin, g/dL | 1.77 | 1.94 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| Albumin:globulin | 2.48 | 2.09 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.83 |

SEM = standard error of the mean; BUN = blood urea nitrogen.

SFC: starter diet containing SFC (65.7% of DM) without SBP; SBP: starter diet containing SBP (25% of DM) as replacement for SFC (43.5% of DM).

The globulin fraction is composed of enzymes, carrier proteins, and immunoglobulins. The concentrations in blood are an indicator of immune system activity, and higher concentrations may indicate an immune response (Kargar and Kanani, 2019). In addition, blood globulin and albumin: globulin ratio have been used to assess systemic immune function during periods of high metabolic demands (Habibi et al., 2019). Based on a constant albumin level between treatment groups, a numerically lower blood globulin concentration in calves fed SFC resulted in an increase (P = 0.03) in albumin: globulin ratio in these calves, indicating a failure of passive transfer immunity in calves fed SFC or the presence of infection and chronic inflammation in calves fed SBP. There was no difference in total blood protein between treatment groups at baseline (mean 6.29 g/dL), indicating the achievement of adequate immunity. However, the incidence of diarrhea tended to be greater (0.7 times) in SBP-fed calves compared with SFC-fed calves, and SBP-fed calves also had a longer time (+2.8 d) of diarrhea compared with SFC-fed calves (data not shown). Accordingly, the lower albumin/globulin ratio in calves fed SBP may indicate that changes in demand and competition for amino acids have occurred, which in turn challenges the hepatic synthesis of globulin needed to maintain normal immune function.

3.3. Sorting index and behavior

Sorting index and intake of nutrients (CP, NDF, NFC, starch and sugar) for particles retained on the different sieves (4.75, 1.18, 0.6, 2.36 mm, and Pan) in Table 4 and Fig. 2. With the exception of the treatment group, calves sorted for particles retained on the 4.75- (average 107%) and 2.36- (average 103%) mm sieves and against feed materials retained on the 1.18- (average 96.1%) and 0.6- (average 83.2%) mm sieves and on the bottom pan (average 69.2%; Table 4). This type of sorting is expected to maximize fiber intake; therefore, calves may also be expected to prefer physically active ration particles once a forage-free starter is offered. It has been suggested that dairy calves can sort feed particles at an early age, and sorting activity in calves may depend on previous experience and dietary requirements (Costa et al., 2016; Kargar and Kanani, 2019), forage inclusion rate (Miller-Cushon and DeVries, 2017), and physical forms of rations (Terré et al., 2016).

Table 4.

Sorting index and particle size intake influenced by partial substitution of shredded beet pulp (SBP) for steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in female Holstein dairy calves (n = 24).

| Item | Treatment (Treat)1 |

SEM |

P-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC | SBP | Treat | Period | Treat × Period | ||

| Sorting index2 (d 51 to 81), % | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 105.6∗ | 107.4∗ | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| 2.36 mm | 102.9∗ | 103.1∗ | 0.51 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.42 |

| 1.18 mm | 96.3∗ | 95.8∗ | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| 0.6 mm | 85.9∗ | 80.5∗ | 1.09 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Pan | 74.5∗ | 63.9∗ | 1.60 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| CP intake, g/d | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 220 | 234 | 6.92 | 0.12 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 mm | 94 | 102 | 2.97 | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.79 |

| 1.18 mm | 54 | 60 | 1.68 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 0.6 mm | 35 | 29 | 1.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Pan | 27 | 16 | 0.76 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NDF intake, g/d | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 106 | 203 | 4.70 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 mm | 46 | 89 | 2.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 1.18 mm | 27 | 52 | 1.21 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 0.6 mm | 17 | 25 | 0.75 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Pan | 13 | 15 | 0.52 | 0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NFC intake, g/d | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 675 | 631 | 20.22 | 0.13 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 mm | 289 | 276 | 8.65 | 0.25 | <0.01 | 0.71 |

| 1.18 mm | 168 | 162 | 4.86 | 0.41 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 0.6 mm | 107 | 78 | 3.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Pan | 82 | 44 | 2.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Starch intake, g/d | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 466 | 343 | 12.84 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 mm | 200 | 150 | 5.46 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 1.18 mm | 116 | 88 | 3.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 0.6 mm | 74 | 42 | 1.91 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Pan | 57 | 24 | 1.42 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sugar intake, g/d | ||||||

| 4.75 mm | 147 | 156 | 4.64 | 0.22 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 mm | 63 | 68 | 1.99 | 0.11 | <0.01 | 0.79 |

| 1.18 mm | 37 | 40 | 1.12 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 0.6 mm | 23 | 19 | 0.70 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Pan | 18 | 11 | 0.51 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

SEM = standard error of the mean. CP = crude protein; NDF = neutral detergent fiber; and NFC = non-fibrous carbohydrate.

∗Sorting values differ from 100% (P ≤ 0.05).

SFC: starter diet containing SFC (65.7% of DM) without SBP; SBP: starter diet containing SBP (25% of DM) as replacement for SFC (43.5% of DM).

Sorting index = 100 × (Actual particle - Size fraction DM intake)/(Predicted particle - Size fraction DM intake). Values equal to 100% indicate no sorting, <100% indicate selective refusals (sorting against), and >100% indicate preferential consumption (sorting for).

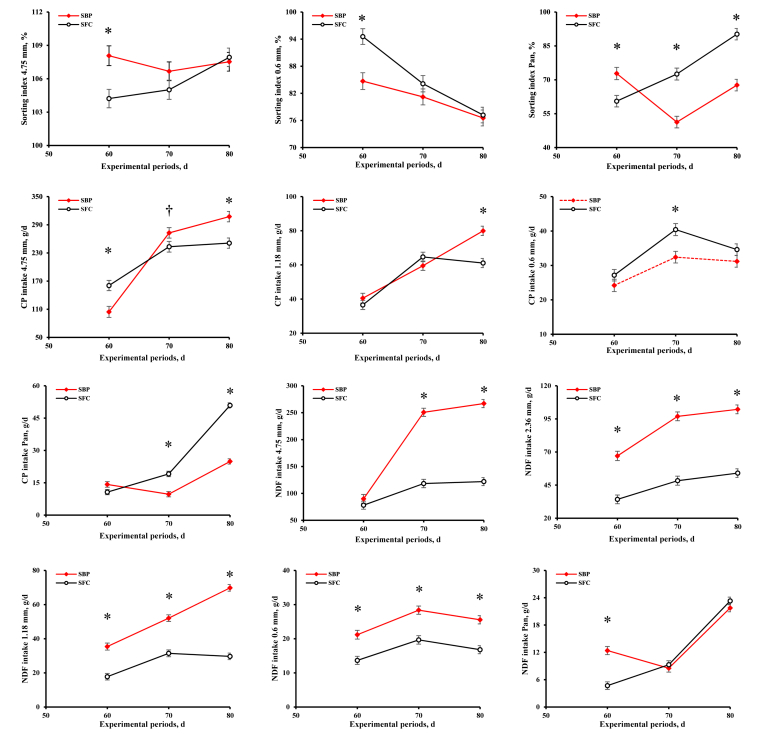

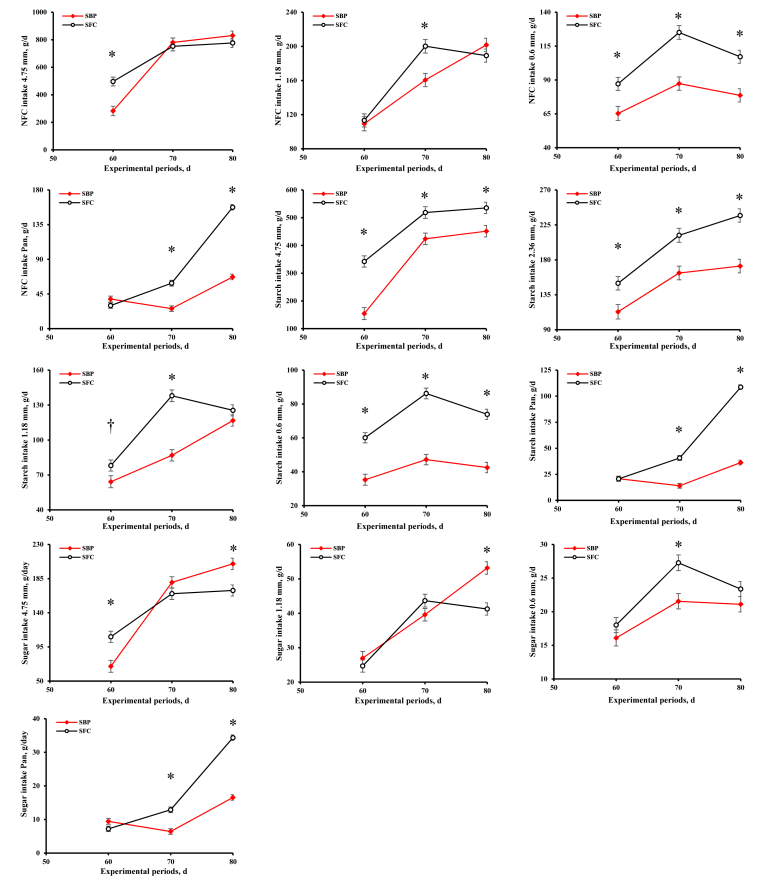

Fig. 2.

Sorting index and intake of nutrients (crude protein [CP], neutral detergent fiber [NDF], non-fibrous carbohydrate [NFC], starch and sugar) for particles retained on the different sieves (4.75, 1.18, 0.6, 2.36 mm and Pan) influenced by partial substitution of shredded beet pulp (SBP) with steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in female Holstein dairy calves (n = 24). For each time point, ∗ denotes a significant difference at P ≤ 0.05. SEM = standard error of the mean.

Particle distribution of the starter feed offered was similar between SBP and SFC diets in the current study (Table 4). Calves fed SBP sorted more (P = 0.02) for particles retained on the 4.75-mm sieve and more against feed materials retained on the 0.6-mm sieve (P < 0.01) and bottom pan (P < 0.01), but not for particles retained on the 2.36- and 1.18-mm sieves. This sorting activity resulted in lower NFC, starch, and sugar intake and increased CP and NDF intake in the SBP diets than in the SFC diets, possibly reflecting differences in component concentrations between the SBP and SFC diets. SFC calves sorted less against particles retained on the 0.6-mm sieve and bottom pan and had a higher selective intake of starch on the top sieve (4.75 mm) compared with other calves, although this sorting activity did not affect total intake ME and ADG. In adult cattle, Farsuni et al. (2017) found that dairy cows fed SBP (12% of DM) sorted in favor of particles on the top sieve and against particles in the bottom pan (1.18 mm) compared to cows fed barley grain.

Nutrients from particles retained on all sieve fractions (except 2.36 mm) were subjected to SBP-to-period interaction (Table 4; Fig. 2). Partial replacement of SBP with SFC resulted in increased CP intake of particles retained on the 2.36- (P = 0.05) and 1.18-mm sieves (P = 0.01), but decreased intake of particles retained on the 0.6-mm sieve (P < 0.01) and bottom pan (P < 0.01). Partial replacement of SFC with SBP was associated with increased uptake of NDF and decreased intake of starch from particles retained on all sieve fractions. Feeding SBP decreased the intakes of NFC and sugars from particles retained on the 0.6 mm sieve and bottom pan; however, higher sugar intake from particles retained on the 1.18 mm sieve was recorded when SBP was replaced with SFC (P = 0.03).

Compared to SFC-fed calves, calves in the SBP treatment group showed greater meal length (3.3 vs. 2.5 min; P < 0.01), meal size (80.6 vs. 68.4 g starter feed DM; P = 0.01), starter feed DM intake (1,045.5 vs. 904.1 g in 6 h; P = 0.03), rumination frequency (4.1 vs. 3.7; P = 0.01) and rumination length (15.6 vs. 13.6 min; P = 0.004), although they had lower eating rate (24.4 vs. 27.4 g starter; P = 0.06) and intervals between rumination events (72.3 vs. 85.4 min; P < 0.01) in the present study (Table 5). Calf behavior, except for resting and drinking, was subject to an SBP-by-period interaction (P < 0.01; Table 5). Rumination activity is mainly influenced by peNDF intake (Welch and Smith, 1970); therefore, the difference in peNDF of the feeding treatments could correspond to the changes in rumination frequency and rumination length in this study. In the current experiment, meal frequency and meal interval were similar between SBP- and SFC-fed calves, suggesting that dairy calves ate the diets with similar ease. Calves fed the SBP diet spent more time on a given meal and consumed the starter feeds at a lower rate (trend) compared to calves fed the SFC diet. This could likely be due to differences in sorting activity and NDF intake of particles retained on the sieves, resulting in a longer meal and thus a longer eating time. It could also be due to a higher time required to discriminate particles resulting from a higher NDF intake of particles retained on all screen fractions. This concept has been previously discussed in dairy cows (Greter et al., 2008). Calves fed SBP diets were found to have higher intake peaks (larger meals) than calves fed SFC diets, which was associated with greater starter intake DM. In contrast, Maktabi et al. (2016) found no significant differences in total standing, lying, eating, rumination, and total chewing times in calves fed starter diets containing SBP compared to the control group.

Table 5.

Meal and rumination patterns, chewing behaviors (in 6 h), and times devoted to resting, standing, lying, drinking, and non-nutritive oral behaviors (NNOB) influenced by partial substitution of beet pulp (BP) for steam-flaked corn (SFC; SBP vs. SFC) in Holstein dairy calves (n = 24).

| Item | Treatment (Treat)1 |

SEM |

P-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC | SBP | Treat | Period | Treat × Period | ||

| Meal chewing in 6 h | ||||||

| Bouts (frequency) | 13.5 | 13.1 | 0.47 | 0.93 | <0.01 | 0.25 |

| Length, min | 2.5 | 3.3 | 0.11 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Interval, min | 24.4 | 24.4 | 2.90 | 0.58 | <0.01 | 0.83 |

| Eating rate, g of starter DM/min | 27.4 | 24.4 | 1.25 | 0.06 | <0.01 | 0.29 |

| Meal size, g of starter DM | 67.4 | 80.5 | 3.74 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.21 |

| Starter intake, g | 904.1 | 1045.5 | 46.31 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.17 |

| Rumination in 6 h | ||||||

| Bouts (frequency) | 3.7 | 4.1 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.78 |

| Length, min | 13.6 | 15.6 | 0.49 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Interval, min | 85.4 | 72.3 | 2.73 | <0.01 | 0.37 | 0.93 |

| Eating, min | 33.0 | 42.9 | 1.13 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Rumination, min | 49.0 | 64.1 | 1.87 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Resting, min | 50.0 | 39.8 | 2.50 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.48 |

| Standing, min | 60.9 | 73.2 | 1.64 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 |

| Lying, min | 113.8 | 99.3 | 2.78 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 |

| Drinking, min | 4.6 | 4.4 | 0.24 | 0.42 | <0.01 | 0.21 |

| NNOB, min | 48.8 | 36.4 | 1.47 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

SEM = standard error of the mean.

SFC: starter diet containing SFC (65.7% of DM) without SBP; SBP: starter diet containing SBP (25% of DM) as replacement for SFC (43.5% of DM).

Calves fed SBP spent more (P < 0.01) time eating, rumination, and standing and less (P < 0.01) time lying and non-nutritive oral behaviors (NNOB) than those fed the SFC diet (Table 5). Drinking time was unaffected by the treatments. The greater rumination activity of calves fed SBP diets compared to those fed SFC diets was the result of more rumination periods of longer duration, which could be due to the greater NDF content of SBP as well as the higher selective intake of NDF. Ingestion of physically effective fiber (forage NDF) is the main driver of time spent chewing the cud daily, as suggested in previous studies (Kargar and Kanani, 2019). Calves fed the SBP diet spent less time lying they spent more time eating, rumination and standing. Our results suggest that increasing eating and rumination time by partially replacing SFC with SBP may be beneficial for reducing NNOB in dairy calves.

4. Conclusions

These results indicate that partial replacement of SBP with SFC (25% of DM) did not affect starter intake, DM, ME, ADG, or feed efficiency of dairy calves, consistent with our hypothesis. The main findings of this study were that partial replacement of SBP with SFC in the diets is desirable because it can increase rumination and eating time and reduce NNOB without negative effects on growth performance. Based on the results on performance and feeding behavior, SBP can be recommended for SFC at 25% of the diet DM for dairy calves.

Author contributions

Shahryar Kargar: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology, validation, formal analyses, writing original draft, writing – review & editing. Zohre Kowsar: Investigation, methodology, data curation. Mehdi Poorhamdollah: Methodology, validation, writing – review & editing. Meysam Kanani: Investigation, validation, formal analyses, visualization, writing – review & editing. Kianoosh Asasi: Investigation, methodology. Morteza H. Ghaffari: Visualization, writing original draft, writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, and there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shiraz University (Shiraz, Iran) for providing suitable experimental conditions. The authors express their kind appreciation to the farm staff at Ali-Naghian Dairy Complex (Isfahan, Iran), for diligent animal care and their help in conducting this experiment.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Shahryar Kargar, Email: skargar@shirazu.ac.ir.

Morteza H. Ghaffari, Email: morteza1@uni-bonn.de.

References

- Asadi-Alamouti A., Alikhani M., Ghorbani G.R., Zebeli Q. Effects of inclusion of neutral detergent soluble fibre sources in diets varying in forage particle size on feed intake, digestive processes, and performance of mid-lactation Holstein cows. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2009;154:9–23. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International . 17th ed. AOAC International; Arlington, VA: 2002. Official methods of analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Beiranvand H., Ghorbani G.R., Khorvash M., Nabipour A., Dehghan-Banadaky M., Homayouni A., Kargar S. Interactions of alfalfa hay and sodium propionate on dairy calf performance and rumen development. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:2270–2280. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiranvand H., Khani M., Ahmadi F., Omidi-Mirzaei H., Ariana M., Bayat A.R. Does adding water to a dry starter diet improve calf performance during winter? Animal. 2019;13:959–967. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118002367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J.H.C., Adderley N.A., Weary D.M., von-Keyserlingk M.A.G. Short communication: effect of diet changes on sorting behavior of weaned dairy calves. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:5635–5639. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis T.S., Suarez-Mena F.X., Hill T.M., Quigley J.D., Schlotterbeck R.L., Lascano G.J. Short communication: effect of replacing corn with beet pulp in a high concentrate diet fed to weaned Holstein calves on diet digestibility and growth. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:408–412. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePeters E.J., Cant J.P. Nutritional factors influencing the nitrogen composition of bovine milk: a review. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:2043–2070. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77964-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsuni N.E., Amanlou H., Silva del Rio N., Mahjoubi E. Responses of fresh cows to three feeding strategies that reduce starch levels by feeding beet pulp. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:4575–4586. doi: 10.2527/jas2017.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelsinger S.L., Coblentz W.K., Zanton G.I., Ogden R.K., Akins M.S. Physiological effects of starter-induced ruminal acidosis in calves before, during, and after weaning. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103:2762–2772. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-17494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greter A.M., DeVries T.J., von Keyserlingk M.A.G. Nutrient intake and feeding behavior of growing dairy heifers: effects of dietary dilution. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:2786–2795. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi Z., Karimi-Dehkordi S., Kargar S., Sadeghi M. Grain source and chromium supplementation: effects on health, metabolic status, and glucose-insulin kinetics in Holstein heifer calves. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:8941–8951. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M.B., Hoover W.H., Jennings J.P., Webster T.K.M. A method for partitioning neutral detergent soluble carbohydrates. J Sci Food Agric. 1999;79:2079–2086. [Google Scholar]

- Iranian Council of Animal Care . vol. 1. Isfahan University of Technology; Isfahan, Iran: 1995. (Guide to the care and use of experimental animals). [Google Scholar]

- Kargar S., Kanani M. Substituting corn silage with reconstituted forage or nonforage fiber sources in the starter feed diets of Holstein calves: effects on intake, meal pattern, sorting, and health. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:7168–7178. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargar S., Habibi Z., Karimi-Dehkordi S. Grain source and chromium supplementation: effects on feed intake, meal and rumination patterns, and growth performance in Holstein dairy calves. Animal. 2019;13:1173–1179. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118002793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laarman A.H., Sugino T., Oba M. Effects of starch content of calf starter on growth and rumen pH in Holstein calves during the weaning transition. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:4478–4487. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi C., Armentano L.E. Effect of quantity, quality, and length of alfalfa hay on selective consumption by dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:557–564. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoubi E., Amanlou H., Zahmatkesh D., Ghelich Khan M., Aghaziarati N. Use of beet pulp as a replacement for barley grain to manage body condition score in over-conditioned late lactation cows. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2009;153:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Maktabi H., Ghasemi E., Khorvash M. Effects of substituting grain with forage or nonforage fiber source on growth performance, rumen fermentation, and chewing activity of dairy calves. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;221:70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Marounek M., Bartos S., Brezina P. Factors influencing the production of volatile fatty acids from hemicellulose, pectin and starch by mixed culture of rumen microorganisms. Z für Tierphysiol Tierernaehrung Futtermittelkd. 1985;53:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- McBurney M.I., Van Soest P.J., Chase L.E. Cation exchange capacity and buffering capacity of neutral detergent fibres. J Sci Food Agric. 1983;34:910–916. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M.E., Redfearn D.D., Ward J.D., Blouin D.C. Effect of protein source and soluble carbohydrate addition on rumen fermentation and lactation performance of Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84:1686–1697. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Cushon E.K., DeVries T.J. Feed sorting in dairy cattle: Causes, consequences, and management. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:4172–4183. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M., Khorvash M., Ghorbani G.R., Kazemi-Bonchenari M., Riasi A., Soltani A., Moshiri B., Ghaffari M.H. Interactions between the physical form of starter (mashed versus textured) and corn silage provision on performance, rumen fermentation, and structural growth of Holstein calves. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:678–686. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeinoddini H.R., Alikhani M., Ahmadi F., Ghorbani G.R., Rezamand P. Partial replacement of triticale for corn grain in starter diet and its effects on performance, structural growth and blood metabolites of Holstein calves. Animal. 2017;11:61–67. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock F.R., Wallenius R.W. Fiber sources for complete calf starter rations. J Dairy Sci. 1980;63:1869–1873. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)83153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naderi N., Ghorbani G.R., Sadeghi-Sefidmazgi A., Kargar S., Ghaffari M.H. Substitution of corn silage with shredded beet pulp affects sorting behaviour and chewing activity of dairy cows. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2019;103:1351–1364. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC . 7th rev. Natl. Acad. Press; Washington, DC: 2001. Nutrient requirements of dairy cattle. [Google Scholar]

- Oltramari C.E., Nápoles G.G.O., De-Paula M.R., Silva J.T., Gallo M.P.C., Soares M.C., Bittar C.M.M. Performance and metabolism of dairy calves fed starter feed containing citrus pulp as a replacement for corn. Anim Prod Sci. 2018;58:561–567. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi-Mirzaei H., Azarfar A., Kiani A., Mirzaei M., Ghaffari M.H. Interaction between the physical forms of starter and forage source on growth performance and blood metabolites of Holstein dairy calves. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:6074–6084. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang D., Yan T., Trevisi E., Krizsan S.J. Effect of grain- or by-product-based concentrate fed with early- or late-harvested first-cut grass silage on dairy cow performance. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:7133–7145. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazoki A., Ghorbani G.R., Kargar S., Sadeghi-Sefidmazgi A., Drackley J.K., Ghaffari M.H. Growth performance, nutrient digestibility, ruminal fermentation, and rumen development of calves during transition from liquid to solid feed: effects of physical form of starter feed and forage provision. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2017;234:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Penner G.B., Oba M. Increasing dietary sugar concentration may improve dry matter intake, ruminal fermentation, and productivity of dairy cows in the postpartum phase of the transition period. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:3341–3353. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terré M., Devant M., Bach A. The importance of calf sensory and physical preferences for starter concentrates during pre- and postweaning periods. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:7133–7142. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest P.J., Robertson J.B., Lewis B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch J.G., Smith A.M. Forage quality and rumination time in cattle. J Dairy Sci. 1970;53:797–800. [Google Scholar]