Abstract

Alcohol and cannabis are the most widely used substances among young people. This study identifies alcohol and cannabis (AC) trajectory classes, and examines class differences on adult role transitions and functioning during emerging adulthood. Participants (n = 3,265) completed six annual surveys (ages 16 to 22) on frequency of past month alcohol and cannabis use. Parallel process growth mixture models were used to model simultaneous trajectories of use and identify latent trajectory classes based on AC co-use. Trajectory classes were compared on age 23 outcomes. Analyses identified four trajectory classes of co-use: Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use (85%); Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking (5%); Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (3%); and Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (7%). The two trajectory classes with early AC co-use were less likely to have made certain role transitions, and reported poorer functioning in emerging adulthood, but in distinct ways. For example, the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class was less likely to graduate from college, and reported more AC consequences and related problems, whereas the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class was less likely to be employed full-time, and reported poorer mental health. The Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class tended to fall between the Initial AC Abstainer class and the two early AC co-use trajectory classes on outcomes. Results indicate the ways in which AC co-use can affect functional outcomes and the timing of role transitions during the transition to young adulthood.

Keywords: alcohol, cannabis, marijuana, co-use, trajectories, adolescence, emerging adulthood

Emerging adulthood is a developmental period, encompassing ages 18–25, characterized by instability, transition, and self-exploration (Arnett, 2000; 2005). Substance use reaches its peak during emerging adulthood (Schulenberg et al., 2020), with 55% of 18–25 year olds reporting past month alcohol use, and 35% reporting past year cannabis use (SAMHSA, 2019). Further, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that the co-use of alcohol and cannabis (in this case, use of both substances within a certain time frame) among emerging adults has increased annually from 2002 to 2018, with the most recent data indicating that about 25% of 18–22 year olds reported using both substances in the past year (McCabe et al., 2020). For emerging adults, alcohol and cannabis co-use is occurring at a critical time when they are trying to navigate the transition from adolescence to adulthood, and thus it is important to better understand how co-use may affect adult role transitions and functioning (e.g., employment, relationships and family formation, life satisfaction) during this critical developmental period.

Consequences and Problems Associated with Alcohol and Cannabis Co-Use

The term “co-use” encompasses different types of behavior such as the use of both substances, but on separate occasions (often defined as concurrent co-use in the literature); the use of one product right after the other so that their effects overlap (defined as sequential use); and the use of both substances by mixing them together (defined as co-administration). Compared to young adults who only use alcohol or cannabis, those who co-use both products (whether concurrently, sequentially, or by co-administration) tend to report heavier and more frequent use - and, perhaps as a result, tend to experience more negative consequences from use (Yurasek, Aston, & Metrik, 2017). Alcohol and cannabis co-use may have serious adverse effects on functioning during emerging adulthood and affect role transitions, although there has been little longitudinal work in this area. One study of a predominantly White cohort from disadvantaged areas in Quebec reported adolescents who used alcohol and cannabis at the same time in the past year at grade 10 had a higher likelihood of experiencing three or more substance-related problems (e.g., legal, academic, relational, health) in grade 11, even after controlling for baseline problems in grade 10 (Brière, Fallu, Descheneaux, & Janosz, 2011). Another prospective study of a predominantly Black cohort of youth from an urban community, which used a longitudinal latent profile analysis to model the frequency of past year alcohol and cannabis use from 8th-12th grade, reported that heavy co-use across adolescence was associated with more negative outcomes during emerging adulthood, including substance use dependence, not graduating from high school, lower income, and criminal justice system involvement (Green et al., 2016). Although heavy co-use was not associated with full-time employment in the Green et al. (2016) study, cross-sectional data from a national sample of adults age 18 and older indicate that those who used alcohol and cannabis at the same time in the past year were more likely to be unemployed, as well as less likely to be partnered, compared to those who had only used alcohol (Subbaraman & Kerr, 2015). Still other studies show that using alcohol and cannabis at the same time is associated with engagement in various risk behaviors among young people, such as impaired driving (Duckworth & Lee, 2019; Terry-McElrath, O’Malley, & Johnston, 2014) and condomless sex (Egan et al., 2019; Parks, Collins, and Derrick, 2012), and that individuals who report using both substances in the past 30 days also report poorer mental health (Cohn et al., 2018). Young people who use alcohol and cannabis at the same time tend to experience more problems than those who use both substances independently (Cummings, Beard, Habarth, Weaver, & Haas, 2019); however, both sequential and concurrent co-use are associated with experiencing a greater number of negative consequences compared to using only one of the substances, even after controlling for heaviness of use (Jackson, Sokolovsky, Gunn, & White, 2020; Subbaraman & Kerr, 2015).

Developmental Trajectories of Alcohol and Cannabis Use

Use of alcohol and cannabis typically begins in adolescence and steadily increases over time, reaching its highest peak during the period of emerging adulthood (Chen & Kandel, 1995); however, not all young people follow this general pattern. Studies of heterogeneity in developmental trajectories of alcohol and cannabis use from adolescence to emerging adulthood often identify several distinct subgroups: consistently low/moderate use that never appreciably escalates over time; early escalation of use during adolescence; delayed escalation of use until emerging adulthood; decreasing use from initially high levels; and consistently high use (e.g., Jackson & Sartor, 2016; Thompson, Merrin, Ames, & Leadbeater, 2018; Tucker, Ellickson, Orlando, Martino, & Klein, 2005). Focusing on these varied developmental trajectories of alcohol and cannabis use is important as it can help identify specific ages during which prevention programs may be optimally effective for each substance, as well as identifying subgroups that may be of particular interest to researchers or practitioners (e.g., those experiencing difficulties during the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood). In general, trajectories characterized by early and persistently high use tend to show poorer health and behavioral outcomes (Jackson & Sartor, 2016).

Simultaneous Trajectories of Alcohol and Cannabis Use

Just as there is heterogeneity in developmental patterns for use of individual substances, the few studies that have modeled trajectories of multiple substances have identified distinct patterns as well. For example, our recent work modeling simultaneous trajectories of tobacco and cannabis use from ages 16 to 21 in a diverse California cohort identified four co-use trajectory classes: young people who consistently engaged in little or no tobacco and cannabis use; those who began engaging in both tobacco and cannabis use during adolescence; those who delayed engaging in tobacco and cannabis use until the transition to young adulthood; and those who quit tobacco use over time, but maintained their cannabis use (Dunbar et al., 2020). Compared to the consistently no-low use class, the other trajectory classes tended to report more poly-tobacco use, poly-cannabis use, use of both tobacco and cannabis on the same occasion, and mixing tobacco with cannabis in emerging adulthood. However, the class that rapidly escalated to co-use of both substances in adolescence reported the worst outcomes. There is little analogous research examining simultaneous trajectories of alcohol and cannabis co-use and associated outcomes in emerging adulthood. One study modelled the use of past year marijuana and alcohol use from grade 8 to grade 12 among urban Black youth, identifying four co-use trajectory classes (Green et al., 2016): adolescents who consistently engaged in little or no use; those who increased to moderate alcohol use and high cannabis use by high school; those who increased to moderate alcohol use in high school, but maintained consistently low cannabis use; and those who rapidly escalated to high co-use of both substances by 10th grade. The class that rapidly escalated to high co-use use during adolescence also reported worse outcomes by emerging adulthood (e.g. substance dependence, criminal justice system involvement) compared to the two trajectory classes that escalated to moderate alcohol use. Further, among the two trajectory classes that escalated to moderate alcohol use, the one that also increased to high cannabis use had worse outcomes than the one that maintained consistently low cannabis use. Together, these studies illustrate that there is considerable heterogeneity in patterns of alcohol and cannabis co-use, with early escalation in co-use during adolescence associated with both the highest levels of use and worst outcomes by emerging adulthood.

Purpose of the Present Study

The present study extends the limited existing literature on alcohol and cannabis co-use and associated outcomes in two important respects. First, we use data from six annual surveys assessing frequency of using each substance in the past 30 days to model simultaneous trajectories of alcohol and cannabis use to identify distinct developmental patterns of co-use of these two substances from ages 16 to 22. Thus, we are examining co-use in general (whether both substances were used in the past 30 days), rather than specific subtypes of co-use such as concurrent, sequential, or co-administration. Second, we compare these distinct trajectory classes in terms of several adult role transitions and functional outcomes by age 23, which were selected based on existing literature such as that cited above. The selected indicators of functioning at age 23, which likely portend whether these young people will experience difficulties as they continue transitioning into adulthood, include substance-related problems (consequences from use, driving under the influence, selling cannabis), socioeconomic status (lower income, food insecurity, homelessness), engagement in risk behaviors (delinquency, condomless sex), social functioning (peer relationship quality), and mental health (life satisfaction, depression, anxiety). The five key adult role transitions include graduating from college, being full-time employed, living independently, being in a committed relationship, and having children. This study complements our prior work with this same cohort that has examined how changes over time in adolescent alcohol use and cannabis use (separately) are each associated with different high school outcomes (D’Amico et al., 2016), as well as more recent work examining early and late adolescent factors that predict alcohol and cannabis concurrent and sequential co-use in emerging adulthood (D’Amico et al., 2020).

Method

Sample and Procedures

Participants were from two cohorts of 6th and 7th grade students enrolled in 2008 (wave 1: mean age 11.5; n = 6,509) and subsequently followed through 2020 (wave 12: mean age 22.6; n = 2,532). Participants were recruited from 16 middle schools across three school districts in Southern California, which were selected to obtain a diverse sample, as part of an evaluation of the voluntary after-school substance use prevention program called CHOICE (D’Amico et al. 2012). Middle school students who participated in CHOICE were representative of students in their schools with respect to demographics and substance use risk (D’Amico et al. 2012). Participants completed waves 1–5 (wave 1: Fall 2008; wave 2: Spring 2009; wave 3: Fall 2009; wave 4: Spring 2010; wave 5: Spring 2011) through paper-pencil surveys during PE classes at schools, with follow-up rates ranging from 74–90% (excluding new youth that could have come in at a subsequent wave) during this time period. Following wave 5, participants transitioned from these middle schools to over 200 high schools. At that point they were re-contacted and re-consented to complete annual web-based surveys, with 61% of the sample participating in wave 6 (Spring 2013-Spring 2014). Wave-to-wave retention rates average 84% across all 12 waves, and 91% from age 18 forward (waves 8–12). Participants who do not complete a particular wave of data collection remain eligible to complete all subsequent waves. That is, they do not “dropout” of the study once they miss a survey wave; rather, we field the full sample at every wave so that all participants have an opportunity to participate in each individual survey. Based on multivariate logistic regression analyses, retention from wave 11 to wave 12 was not predicted by wave 11 past month substance use (alcohol, cannabis, or cigarettes); however, females were more likely to be retained than males (93.41% vs. 90.53%, respectively); Hispanics (93.28%) and Asians (92.93%) were more likely to be retained than Whites (90.87%), Blacks (82.76%), or others (90.11%); and those retained were slightly younger than those who were not (mean age = 21.57 vs. 21.85, respectively). Participants are paid $50 for completing each web-based survey. Study procedures are reported in detail elsewhere (D’Amico et al. 2012). All participants consented to the study and procedures were approved by the study’s Institutional Review Board. The current study uses data from wave 6 (2014–2015) through wave 12 (2019–2020), which corresponds to the period from high school to emerging adulthood (analytic sample N = 3,265). The analytic sample has a mean age of 16.2 years at wave 6, and is 53.2% female, 46.2% Hispanic, 23.9% non-Hispanic white, 21.3% Asian, 2.4% non-Hispanic black, and 6.3% multi-racial/other.

Measures

Background covariates.

Variables included self-reported gender, mother’s education, and race/ethnicity. Participants were classified into one of five racial/ethnic groups: Hispanic, non-Hispanic white (reference group), non-Hispanic black, Asian, and multi-racial/other. Although the CHOICE program, conducted over 10 years ago, did not show intervention effects beyond one year, we controlled for intervention status.

Alcohol and cannabis use trajectories from Waves 6 through 11.

Alcohol use and cannabis use were assessed by separate items asking: “During the past month (30 days), how many days did you use… at least one drink of alcohol; marijuana (pot, weed, grass, hash, bud, sins)?” Response options at Waves 6–10 were: 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3–5 days, 6–9 days, 10–19 days, and 20–30 days, whereas a continuous measure was used at Wave 11 (0–30 days). Responses were recoded as 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more days for each substance due to infrequent responses at high levels of use.

Adult role transitions at wave 12.

We assessed whether participants: (a) had graduated from college (AA degree or higher; yes/no); (b) were currently employed full-time (yes/no); (c) were in a committed romantic relationship (yes/no; defined as being married, engaged, living with a partner but not married or engaged, or dating one person exclusively for six months or longer); (d) were living independently (yes/no; defined as not currently living with any family members); and (e) had any children (yes/no; includes stepchildren and adopted children).

Substance-related problems at Wave 12.

Negative consequences in the past year due to alcohol use (9 items) and cannabis use (10 items) were assessed with items drawn from the RAND Adolescent/Young Adult Panel Study (Bogart, Collins, Ellickson, Martino, & Klein, 2005; Ellickson, D’Amico, Collins, & Klein, 2005) and the Cannabis Consequences Questionnaire (Simpson, Dvorak, Merrill, & Read, 2012). Sample items include missing school, work, or other obligations; getting into trouble; and doing something they later felt sorry for (1 = never to 7 = 20 or more times). For each substance, items were summed (alcohol: range = 0 to 63, mean = 13.05, SD = 6.82; cannabis: range = 0 to 70, mean = 12.69, SD = 6.66). Separate items assessed past year frequency of driving under the influence of alcohol and cannabis, which were averaged (r = .37), and past year frequency of selling cannabis/hashish. These three items were rated on a scale of 0 = not at all to 5 = 30 or more times and recoded into pseudo-continuous variables that represent number of instances in the past year.

Risk behavior at wave 12.

Four items asked about frequency with which participants engaged in various problem behaviors in the past year (being involved in fights, stealing, property damage, graffiti), each rated on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all to 6 = 20 or more times). Scores were summed, with higher values indicating greater engagement in delinquent behaviors in the past year (range = 1–24, mean = 4.40, SD = 1.63). In addition, the proportion of condomless sexual events in the past 30 days was assessed by first asking the number of times the participant had sex with a steady partner and a casual partner in the past 30 days, and then asking the number of those times that a condom was used. The proportion of condomless sexual events was then calculated for each partner type and averaged; participants who were not sexually active in the past 30 days were coded as 0.

Socioeconomic status at wave 12.

Participants indicated how much income they earned from a full- or part-time job in the past 30 days. In addition, we assessed food insecurity and experiences of homelessness (Sontag-Padilla et al., 2017). Food insecurity was assessed with two items asking how often the following was true in the past 12 months: “I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more” and “The food that I bought just didn’t last, and I didn’t have money to get more.” Both were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = always true to 4 = never true) and averaged (r = .82), such that higher scores indicated less food insecurity (range = 1 – 4, mean = 3.60, SD = 0.73). Experiences of homelessness were assessed with items asking whether, in the past 12 months, the participant had slept at a friend’s and/or family member’s home because they had nowhere else to stay, or spent the night in each of the following places because of nowhere else to stay: youth or adult shelter; public place, such as a train or bus station, restaurant, or office building; an abandoned building; outside in a park, on the street, under a bridge or overhead, or on a rooftop; in a subway or other public place underground; with someone you did not know because you needed a place to stay; or in a car, truck or van. A dichotomous indicator was derived indicating whether they had endorsed any of these items (yes/no).

Social functioning at wave 12.

Past month peer relationship quality was assessed using eight items from the PROMIS Peer Relationships Short Form item bank (DeWalt et al., 2013). Sample items include “I was able to count on my friends” and “I felt accepted by other kids/other people my age,” each rated on a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = always; α = 0.95). Scores of 0 to 35 were transformed to a z-score per the scoring instructions, with higher values indicating better social functioning (range = 19.30 – 69.79, mean = 50, SD = 10).

Mental health at wave 12.

We assessed overall life satisfaction with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985; α = 0.92), which includes 5 items that are rated on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree and summed (range = 5–35, mean = 22.31, SD = 7.82). Two other measures assessed mental health symptoms in the past two weeks on a scale from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day. The Patient Health Questionnaire – 8 item (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009; α = 0.91) assessed eight symptoms of depression such as feeling down, depressed, or hopeless and having little interest or pleasure in doing things (range = 0–24, mean = 5.58, SD =5.59). The Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 item (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006; α = 0.95) assessed seven symptoms of anxiety such as feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge and not being able to stop or control worrying (range = 0–21, mean = 5.16, SD = 5.57).

Analytic Plan

Parallel process growth mixture models (PP-GMM: Hix-Small, Duncan, Duncan, & Okut, 2004; Wu, Witkiewitz, McMahon, & Dodge, 2010) were used to simultaneously model heterogeneity in alcohol and cannabis co-use from waves 6 to 11. The PP-GMM combines parallel process latent growth modeling with latent class analysis in order to group individuals whose trajectories of both alcohol and cannabis use are similar, thereby grouping respondents based on their patterns of use of both products across time. The latent class variable was defined by alcohol and cannabis use growth factors (i.e., intercept and slope). A series of PP-GMMs were estimated in Mplus v8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012–2018) using robust maximum likelihood estimation, which can accommodate categorical and ordinal data, missing data, and provide unbiased and consistent estimates (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Further, because our data modeled growth of ordinal data, we used a Monte Carlo Integration algorithm with 1000 random starts. GMMs allow for variation in growth trajectories yielding separate growth models for each resultant latent class, each with unique parameter estimates (e.g., means, variance, and co-variance, and residual variance). A series of models were estimated with one to five trajectory classes, and fit was evaluated using several indicators: lower values of negative two log likelihood (−2LL), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), the sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (aBIC), and a non-significant Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio test (VLRT), Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LRT), and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) indicating better model fit.

Class differences on distal outcomes (e.g., alcohol/cannabis consequences, risk behavior, mental health) were tested using the manual three-step auxiliary BCH approach (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014) which yields a pseudo-class Wald chi-square test assessing mean differences between trajectory classes. Similarly, for categorical distal outcomes (e.g., committed relationship, independent living, college degree), the manual three-step auxiliary approach was performed, however, using the categorical function (DCAT). The three-step procedure fixes latent class parameters to ensure that covariates do not influence measurement of trajectory classes.

Results

The sample was 53.2% female, with an average age of 16.2 (SD=0.7) at wave 6 and 22.6 (SD=0.8) at wave 12. The sample was diverse with 23.9% non-Hispanic white, 46.2% Hispanic, 2.4% non-Hispanic black, 21.3% Asian, and 6.3% multi-racial/other. Descriptive statistics on outcome variables by class are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Class differences on young adult role transitions and functioning outcomes

| Overall sample | Class 1: Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use |

Class 2: Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking |

Class 3: Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking |

Class 4: Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking |

Significant group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult role transitions | ||||||

| Has college degree | 0.55 (0.01) | 0.56 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.05) | 0.57 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.04) | 4<1 |

| Is employed full-time | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.04) | 0.39 (0.06) | 0.34 (0.04) | 2<1,3 |

| Is living independently | 0.34 (0.01) | 0.32 (0.01) | 0.43 (0.05) | 0.43 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.04) | 4>1; 2>1 |

| In committed relationship | 0.42 (0.01) | 0.41 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.05) | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.51 (0.04) | 4>1 |

| Has child(ren) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.03) | ns |

| Functional outcomes | ||||||

| Alcohol consequences | 13.05 (0.14) | 12.40 (0.13) | 16.31 (0.90) | 15.90 (1.04) | 17.76 (0.87) | 4,3,2>1 |

| Cannabis consequences | 12.69 (0.13) | 12.13 (0.13) | 14.57 (0.81) | 13.42 (0.83) | 18.46 (0.97) | 4>3,2,1; 2>1 |

| Driving under influence | 0.94 (0.06) | 0.73 (0.06) | 1.80 (0.36) | 0.93 (0.29) | 3.15 (0.44) | 4>3,2,1; 2>1 |

| Cannabis selling | 0.35 (0.04) | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.30) | 0.42 (0.25) | 1.57 (0.40) | 4>3,1 |

| Delinquency | 4.40 (0.03) | 4.31 (0.03) | 4.90 (0.24) | 4.38 (0.12) | 5.16 (0.27) | 4>3,1; 2>1 |

| Condomless sex | 22.6 (0.57) | 20.81 (0.61) | 32.10 (2.93) | 29.18 (3.63) | 34.49 (2.66) | 4 3,2>1 |

| Income | 2054.24 (132.47) | 2090.95 (151.90) | 1521.96 (173.96) | 3263.92 (1272.76) | 1603.62 (267.17) | 2<1 |

| Lower food insecurity | 3.60 (0.04) | 3.62 (0.02) | 3.57 (0.07) | 3.65 (0.10) | 3.43 (0.07) | 4<1 |

| Homelessness (yes/no) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.11 (0.03) | 3<2,4a |

| Peer social functioning | 49.99 (0.20) | 49.84 (0.22) | 49.91 (0.93) | 51.95 (1.09) | 50.73 (0.83) | ns |

| Life satisfaction | 22.31 (0.57) | 22.32 (0.17) | 21.81 (0.81) | 22.41 (1.03) | 22.42 (0.67) | ns |

| Depression (PHQ) | 5.58 (0.11) | 5.47 (0.12) | 6.66 (0.59) | 5.43 (0.61) | 6.38 (0.52) | 2>1 |

| Anxiety (GAD) | 5.16 (0.11) | 4.99 (0.12) | 6.43 (0.54) | 5.88 (0.68) | 5.98 (0.53) | 2>1 |

Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use (85% of sample); Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking (5%); Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (3%); and Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (7%). Table is reporting M(SE) and proportions(SE).

p = .051

Alcohol and Cannabis Parallel Process Growth Mixture Models

PP-GMM models were fit starting with a one-class model through a five-class model. Fit indices determined the best fitting model (see Table 1). Based on non-significant LRT and BLRT values for the five-class solution, we determined that the four-class solution fit the data best. Additionally, the four class solution had lower values for AIC, BIC, and −2LL relative to the solutions with fewer classes. Growth factor means and correlations for the four-class solution are presented by class in Table 3.

Table 1.

Model fit statistics for parallel process growth mixture for alcohol and cannabis use

| Class No. | −2LL | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | VLRT | p | LMRT | p | BLRT | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 79284.8 | 79336.8 | 79495.2 | 79412.6 | |||||||

| 2 | 74648.8 | 74710.8 | 74899.6 | 74801.1 | 0.97 | 4636.0 | <0.00 | 4524.2 | <0.00 | 4636.0 | <0.0 |

| 3 | 71977.0 | 72049.0 | 72268.2 | 72153.9 | 0.96 | 2671.8 | 0.031 | 2607.4 | 0.03 | 2671.8 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 70993.9 | 71075.9 | 71325.7 | 71195.4 | 0.96 | 983.0 | <0.00 | 959.3 | <0.00 | 983.0 | 1.0 |

| 5 | 69999.8 | 70091.8 | 70372.0 | 70225.9 | 0.95 | 994.1 | 0.05 | 970.1 | 0.06 | 994.1 | 1.0 |

Note. −2LL = −2*Log-likelihood; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; aBIC = Sample size-adjusted BIC; BLRT = Parametric Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test; LMRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test

Table 3.

Growth factor means and correlations

| Class 1: Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use |

Class 2: Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking |

Class 3: Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking |

Class 4: Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ||||

| CInt | 0.001, p<.001 | 1.347, p<.001 | 0.007, p<.001 | 2.99, p<.001 |

| CSlp | 0.154, p<.001 | 0.041, p<.001 | 0.273, p<.001 | −0.243, p<.001 |

| AInt | 0.049, p<.001 | 1.389, p<.001 | 2.541, p<.001 | 1.821, p<.001 |

| ASlp | 0.304, p<.001 | 0.213, p<.001 | −0.053, p<.001 | 0.112, p<.001 |

| Correlations | ||||

| CInt, CSlp | 0.105, p<.001 | 0.027, p=.738 | 0.008, p=.934 | −0.219, p=.001 |

| AInt, ASlp | 0.455, p<.001 | −0.106, p=.193 | −0.281, p=.004 | −0.013, p=.847 |

| CInt, AInt | 0.571, p<.001 | 0.464, p<.001 | −0.226, p=.020 | 0.393, p<.001 |

| CSlp, ASlp | 0.741, p<.001 | 0.667, p<.001 | 0.544, p<.001 | 0.684, p<.001 |

Note. C = Cannabis, A = Alcohol, Int = Intercept, Slp = Slope

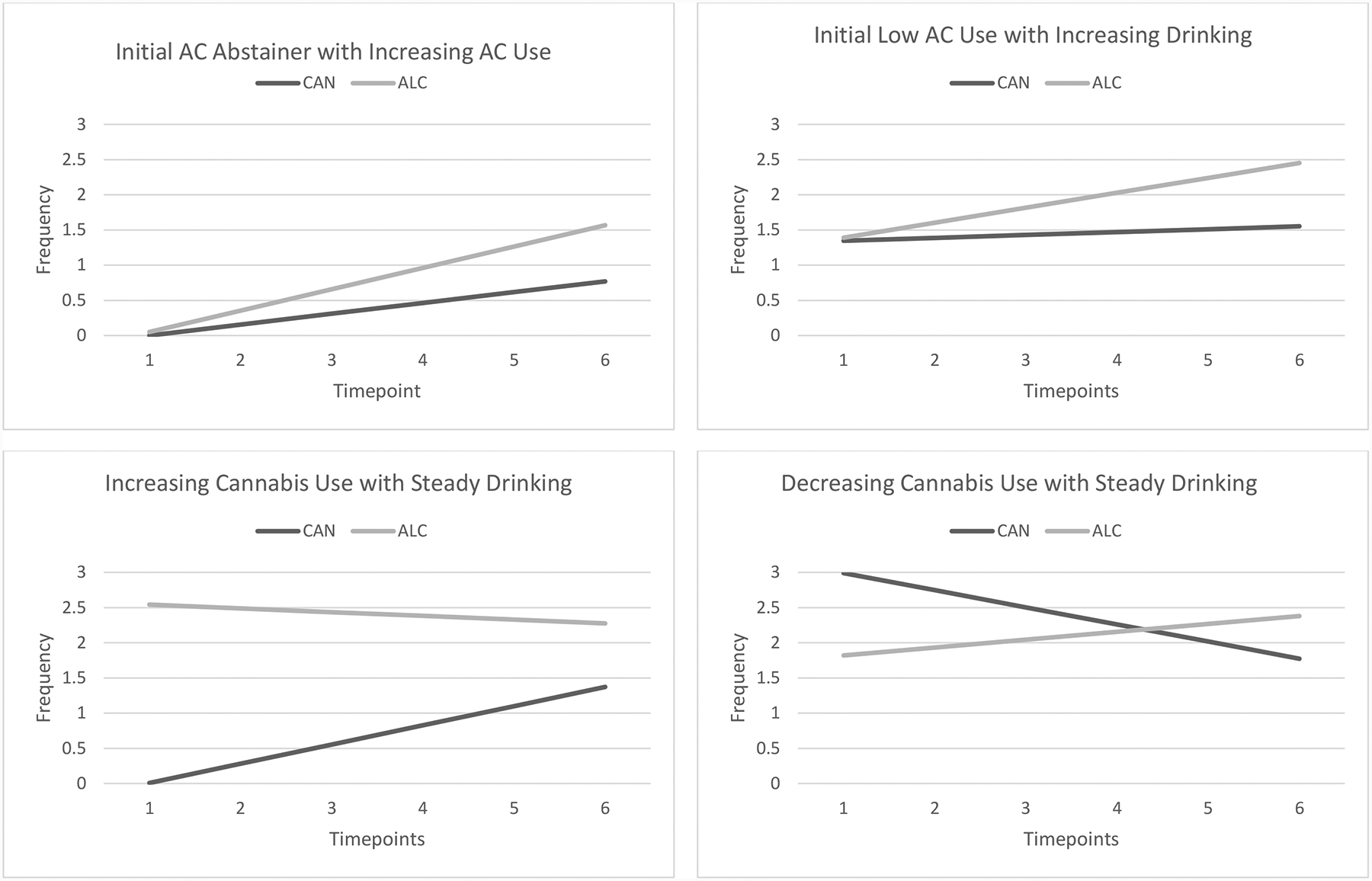

Figure 1 presents co-use trajectories for the four emergent trajectory classes. Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use (n = 2782; 85% of sample) represents individuals who initially did not or minimally used both alcohol and cannabis in the past month; however, over time they increased their use of both substances, but with a more pronounced increase in alcohol consumption. Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking (n = 152; 5%) includes youth who had low initial use of both alcohol and cannabis in the past month; however, they reported increased alcohol use over time, whereas their cannabis use remained stably moderate. Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (n = 106; 3%) represents youth who reported high initial alcohol consumption and no-to-low cannabis use in the past month; however, they remained relatively stable in alcohol use whereas their cannabis use in the past month increased over time. Lastly, Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking (n = 225; 7%) includes individuals whose initial past month use was high for both alcohol and cannabis, and remained consistently high across time. However, there was a reversal in use status over time such that cannabis was used more frequently than alcohol initially, but declined somewhat such that alcohol was used more frequently than cannabis by the final assessment wave.

Figure 1.

Past month frequency (0, 1, 2, 3 or more days) of alcohol and cannabis use from waves 6 to 11 by class. This figure shows co-use trajectory patterns for each class based upon parallel process growth mixture models. CAN = cannabis; ALC = alcohol.

Young Adulthood Outcomes

Adult Roles Transitions by Age 23

Class differences in adult role transitions (graduating college, full-time employment, living independently, being in a committed relationship, and being a parent) are presented at the top of Table 2. Compared to the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class, the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class was less likely to have a college degree (p = .02), but more likely to be living independently (p < .01) and in a committed relationship (p = .04). Compared to the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class, the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking was also more likely to be living independently (p = .02), but less likely to be employed full-time (p = .01). Finally, the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class was less likely to be working full-time than the Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class (p = .03). The four trajectory classes did not significantly differ with respect to parenthood.

Functioning at Age 23

Class differences in young adult functioning are presented at the bottom of Table 2. The Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class reported greater cannabis-related consequences and frequency of driving under the influence than all other trajectory classes (all p’s ≤ .02). Furthermore, the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class reported more cannabis selling and greater delinquency than the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use and Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking trajectory classes (all p’s ≤ .01). The Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class reported fewer alcohol-related consequences and lower frequency of condomless sex than all other trajectory classes (all p’s ≤ .02). The Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class reported greater depression, anxiety, delinquency, driving under the influence, and cannabis-related consequences than the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class (all p’s < .05). The Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class reported higher monthly income than the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class (p = .01), but also indicated greater food insecurity than the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class (p = .01). In terms of experiencing homelessness in the past year, both the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class (p = .02) and the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class (marginally significant; p = .051) were more likely to report experiencing homelessness in the past year compared to the Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class. The four trajectory classes did not significantly differ in terms of the perceived quality of their peer relationships or their overall life satisfaction.

Discussion

Emerging adulthood is often described as the period bridging the end of adolescence and the beginning of full-fledged adulthood. Alcohol and cannabis use reach their highest levels during emerging adulthood (Schulenberg et al., 2020), while at the same time, young people are starting to navigate the challenges of transitioning to young adulthood and the “milestone events” that have typically been considered as marking this transition such as finishing secondary school, obtaining stable employment, living independently, partnering, and parenting (Arnett, 2014). In examining these types of transitions in our diverse California cohort, by age 23 more than half of the sample (56%) had graduated from college, whereas less than half reported being employed full-time (33%), living independently (34%), or being in a committed relationship (42%). Fewer than 1 in 10 were parenting by this age, which is not surprising given national trends indicating that the transition to parenthood is occurring at a later age compared to previous generations (Matthews, & Hamilton, 2016). The goal of the present study was to model simultaneous trajectories of alcohol and cannabis use from age 16 to 22 and examine whether different trajectory classes of co-use predicted the likelihood of transitioning to adult roles by age 23, as well as functional outcomes in the domains of substance use-related problems, socioeconomic status, risk behavior, social functioning, and mental health.

We identified four distinct trajectory classes of alcohol and cannabis co-use from mid-adolescence to emerging adulthood. Similar to prior studies identifying trajectories of use for single substances (Jackson & Sartor, 2016), we found a class that consistently reported relatively low levels of alcohol and cannabis use over time (although with some increase in use), as well as a class that consistently reported co-use of both substances at relatively high levels from mid-adolescence to emerging adulthood (although with some decrease in cannabis use). We also identified two trajectories that exhibited more distinct changes in use over time. One of these trajectory classes did not engage in early alcohol and cannabis co-use at age 16, but rather showed steady high alcohol use, coupled with increased cannabis use that never reached the level of their alcohol use. The other class exhibited early alcohol and cannabis co-use at age 16, and then continued to steadily escalate their drinking over the next several years. Interestingly, and similar to prior work (Green et al., 2016), we did not find a trajectory class that used cannabis in the absence of at least moderate levels of drinking. These four trajectory classes had similar (and relatively high) levels of peer social functioning and life satisfaction by age 23. However, for the three trajectory classes characterized by more than minimal alcohol and cannabis co-use over time, although they ended up with similar levels of substance use by age 22, their different pathways of co-use from adolescence to emerging adulthood appear to have important implications for role transitions and functioning by age 23.

Most of the sample was in a class (labelled Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use) characterized by little to no past month use of alcohol and cannabis at age 16, followed by a modest increase in past month cannabis use and somewhat more pronounced increase in past month alcohol use over time. However, their use of these substances never exceeded that of the other three trajectory classes. Differences between the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class and the other trajectory classes on functioning were mostly related to consequences from use and risk behavior, with the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class tending to fare better in terms of experiencing fewer negative consequences from their use and engaging less frequently in behaviors such as driving under the influence, selling cannabis, and condomless sex. In terms of role transitions, the distinguishing feature of the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class is that they were the least likely to be living independently by age 23. Although our measure of use focused on frequency rather than quantity, this finding is consistent with cross-sectional results from the national Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which found that 18–23 year olds who lived at home were significantly less likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking (although not necessarily cannabis use) compared to those who were living independently (Patrick, Wightman, Schoeni, & Schulenberg, 2012). It may be the case that emerging adults in the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class are less interested in the freedoms of living away from home given their low level of alcohol and cannabis use, or living at home may have a dampening effect on their use of these substances. Although we cannot untangle these (and other) possible explanations, our results suggest that the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class, while modestly increasing their use of both substances over time, appears to be functioning relatively well in emerging adulthood compared to the other trajectory classes.

As mentioned earlier, the other three trajectory classes took very different pathways to their comparable levels of alcohol and cannabis use by age 22, with each of these pathways having a distinct profile in terms of role transitions and functional outcomes. The only class that showed early high levels of both alcohol and cannabis use (Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking) is distinguished from the other trajectory classes at age 23 in terms of experiencing more consequences and more use-related problems (e.g., driving under the influence, selling cannabis, delinquency). Given that young people who co-use alcohol and cannabis tend to report heavier and more frequent use compared to those who use only one of these substances (Yursasek et al., 2017), it is perhaps not surprising that the class with consistently higher use of both substances from ages 16 to 22 (albeit with some decrease in cannabis use over time) would experience the most difficulties in these areas. In terms of role transitions, another distinguishing feature of the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class was their lower rate of college graduation by age 23. Findings from Monitoring the Future (MTF) data indicate that graduating from college is predicted by certain types of substance use among high school seniors, such as cannabis and other illicit drug use (Patrick, Schulenberg, O’Malley, 2016). This suggests that the early cannabis use exhibited by the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class in high school, perhaps in conjunction with the use of alcohol, may have contributed to their lower likelihood of college graduation by age 23.

Of the remaining two trajectory classes, the one that did not exhibit early alcohol and cannabis co-use at age 16 (Increasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking) tended to fall in the middle of the other trajectory classes on most indicators of functioning. It may be that their lack of early co-use of these substances in high school had somewhat of a protective effect in terms of functional outcomes in emerging adulthood, despite their relatively high level of drinking in high school and increased cannabis use over time. In contrast, the class that exhibited early co-use of alcohol and cannabis at age 16, and then continued to steadily escalate their drinking over the next several years (Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking) reported more problems across a range of outcomes. First, they reported more substance use consequences and related problems compared to the Initial AC Abstainer with Increasing AC Use class. Similar to the Decreasing Cannabis Use with Steady Drinking class, this may be a function of their early and sustained co-use of alcohol and cannabis from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Second, the Initial Low AC Use with Increasing Drinking class is distinguished from the other trajectory classes in terms of relatively high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms. Given the association of heavier alcohol use with internalizing problems (Tembo, Burns, & Kalembo, 2017; Vanheusden et al., 2008), the greater mental health symptoms reported by this class may be tied to their pattern of co-use involving escalated drinking from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Third, this class reported more problems related to economic instability at age 23, such as lack of full-time employment, lower income, and experiencing homelessness. The comorbidity of substance use and mental health problems that characterizes this class may explain the greater challenges they were facing in this domain, as prospective research with young adults has shown that those with comorbid substance use and mental health problems have more difficulty achieving long-term adult economic stability compared to young adults without these problems (Lee, Herrenkohl, Kosterman, Small, & Hawkins, 2013).

Results from this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations and caveats. First, results are based on a predominantly California sample and may not generalize to young people in other geographic areas (especially those with different cannabis regulations). Second, the relatively small sample sizes for three of the four co-use trajectory classes may have resulted in certain differences between trajectory classes not being statistically significant, although potentially clinically meaningful. Third, information on specific subtypes of co-use (e.g., whether the substances were used at the same time so that their effects overlap) was not available at each wave; thus, the focus of this study is more generally on longitudinal patterns of using both substances in the past month. However, we expect that using both substances at the same time was common among those who reported co-use in our sample. For example, our prior work with this cohort at wave 10 (mean age=20.7) found that 20% of all participants reported using both alcohol and cannabis at the same time in the past 30 days (D’Amico et al., 2020). Further, a recent study of college students found that 75% of those who used both alcohol and cannabis in the past year reported at least one occasion of using them at the same time (Terry-McElrath & Patrick, 2018). Fourth, we were not able to incorporate information on quantity of use into the analyses; however, the measures of alcohol and cannabis consequences, which capture problems associated with use, may have more clinical significance. Fifth, we relied exclusively on self-report data, which is subject to the usual concerns about reporting bias; however, participants had little incentive to misrepresent their alcohol or cannabis use or emerging adult outcomes. Further, it is important to note that rates of substance use in the cohort over time have tracked rates reported from national surveys of similarly aged youth (Schulenberg et al., 2020). Finally, in interpreting the trajectory class differences in role transitions, it is important to consider that these outcomes were assessed at a relatively young age. We are not suggesting that still being in school, living at home, being single, and so forth should be considered a “negative outcome” at age 23. Rather, given that emerging adulthood is a period of preparing for role transitions that have important repercussions across the adult lifespan, we were interested in understanding how developmental patterns of alcohol and cannabis co-use were associated with the timing of these transitions (i.e., whether they occurred by age 23). It will be important for future research to extend our analyses by examining how AC co-use may affect role transitions and functioning at older ages, as well as examining cyclical and bidirectional relationships of AC co-use with these role transitions.

By identifying four distinct trajectory classes of alcohol and cannabis co-use from adolescence to emerging adulthood, this study illustrates the considerable heterogeneity in patterns of co-use of these two substances among young people, and how differences in these patterns may have consequences for the timing of role transitions, as well as functioning during the transition to young adulthood. Importantly, early co-use of both substances during adolescence was associated with the highest levels of use, a lower likelihood of certain role transitions, and poorer functioning by emerging adulthood. Further, early co-use of both substances coupled with escalated drinking appeared to put youth at additional risk for mental health problems and economic instability over time. Results suggest that screening for the co-use of alcohol and cannabis during adolescence may help identify youth who may need support in attaining certain role transitions (e.g., completing college, full-time employment) or who may be vulnerable to certain problems in functioning, and afford the opportunity for early brief interventions to reduce their use. In fact, one recent study found that a brief screen and 15 motivational interviewing intervention in primary care for adolescents age 12–18 reduced alcohol and cannabis use consequences one year later, and that adolescents with more severe use, such as cannabis use or alcohol use disorder were even more likely to benefit from the intervention (D’Amico et al., 2018; 2019). Of note, older adolescents with a history of alcohol and cannabis co-use may also need additional assistance as they prepare to graduate from high school in navigating young adult role transitions related to education, employment, independent living, and financial stability. Finally, our results suggest that the challenges associated with alcohol and cannabis co-use among young people may not be manifested in terms of poor peer social functioning or lower life satisfaction, suggesting that the other indicators of functioning examined in this study may be more informative indicators of overall functioning and fruitful targets for intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by three grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA016577, R01AA020883, R01AA025848; PI: D’Amico). The authors would like to thank the study participants and districts and schools who participated and supported the CHOICE project. We also thank Kirsten Becker and Jennifer Parker for overseeing the school survey administrations and the web-based surveys.

References

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2005). The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35, 235–253. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21, 329–341. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.915181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2010). Weighted least squares estimation with missing data. Mplus Technical Appendix, 2010, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Martino SC, & Klein DJ (2005). Effects of early and later marriage on women’s alcohol use in young adulthood: a prospective analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 729–737. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brière FN, Fallu J-S, Descheneaux A, & Janosz M (2011). Predictors and consequences of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 785–788. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, & Kandel DB (1995). The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Johnson AL, Rose SW, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, & Stanton C (2018). Population-level patterns and mental health and substance use correlates of alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use and co-use in US young adults and adults: Results from the Population Assessment for Tobacco and Health. The American Journal on Addictions, 27, 491–500. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C, Beard C, Habarth JM, Weaver C, & Haas A (2019). Is the sum greater than its parts? Variations in substance-related consequences by conjoint alcohol-marijuana use patterns. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51, 351–359. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2019.1599473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Parast L, Osilla KC, Seelam R, Meredith LS, Shadel WG, & Stein BD (2019). Understanding which teenagers benefit most from a brief primary care substance use intervention. Pediatrics, 144(2) e20183014. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Parast L, Shadel WG, Meredith LS, Seelam R, & Stein BD (2018). Brief motivational interviewing intervention to reduce alcohol and marijuana use for at-risk adolescents in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86, 775–786. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Rodriguez A, Tucker JS, Dunbar MS, Pedersen ER, Shih RA, Davis JP, & Seelam R (2020). Early and late adolescent factors that predict co-use of cannabis with alcohol and tobacco in young adulthood. Prevention Science, 21, 530–544. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01086-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Ewing BA, Shih RA, & Pedersen ER (2016). Alcohol and marijuana use trajectories in a diverse longitudinal sample of adolescents: Examining use patterns from age 11 to 17. Addiction, 111, 1825–1835. doi: 10.1111/add.13442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Zhou AJ, Shih RA, & Green HDJ (2012). Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after school program for middle school students: results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of CHOICE. Prevention Science, 13, 415–25. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Langer M, Morgan DE, Irwin D et al. (2013). PROMIS pediatric peer relationships scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychology, 32, 1093–1103. doi: 10.1037/a0032670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth JC, & Lee CM (2019). Associations among simultaneous and co-occurring use of alcohol and marijuana, risky driving, and perceived risk. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Davis JP, Tucker JS, Seelam R, Shih RA, & D’Amico EJ (2020). Developmental trajectories of tobacco/nicotine and cannabis use and patterns of product co-use in young adulthood. Tobacco Use Insights, 13, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1179173X20949271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KL, Cox MJ, Suerken CK, Reboussin BA, Song EY, Wagoner KG, & Wolfson M (2019). More drugs, more problems? Simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana at parties among youth and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202, 69–75. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, D’Amico EJ, Collins RL, & Klein DJ (2005). Marijuana use and later problems: when frequency of recent use explains age of initiation effects (and when it does not). Substance Use and Misuse, 40, 343–359. doi: 10.1081/ja-200049356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Johnson RM, Matson PA, Reboussin BA, & Ialongo NS (2016). Outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana and alcohol use among urban young adults: a prospective study. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hix-Small H, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, & Okut H (2004). A multivariate associative finite growth mixture modeling approach examining adolescent alcohol and marijuana use. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(4), 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, & Sartor CE (2016). The natural course of substance use and dependence. In Sher KJ (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders (p. 67–131). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sokolovsky AW, Gunn RL, & White HR (2020). Consequences of alcohol and marijuana use among college students: Prevalence rates and attributions to substance-specific versus simultaneous use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34, 370–381. doi: 10.1037/adb0000545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorder, 114, 163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JO, Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Small CM, & Hawkins JD (2013). Educational inequalities in the co-occurrence of mental health and substance use problems, and its adult socioeconomic consequences: A longitudinal study of young adults in a community sample. Public Health, 127. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, & Hamilton BE (2016). Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS data brief, no 232. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Arterberry BJ, Dickinson K, Evans-Polce RJ, Ford JA, Ryan JE, & Schepis TS (2020). Assessment of changes in alcohol and marijuana abstinence, co-use, and use disorders among US young adults from 2002 to 2018. JAMA Pediatrics. Online first publication. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012–2018). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Collins RL, & Derrick JL (2012). The influence of marijuana and alcohol use on condom use behavior: findings from a sample of young adult female bar drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 888–894. doi: 10.1037/a0028166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM (2016). High school substance use as a predictor of college attendance, completion, and dropout: A national multi-cohort longitudinal study. Youth and Society, 48, 425–447. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13508961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, & Schulenberg JE (2012). Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: A comparison across constructs and drugs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73, 772–782. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA & Patrick ME (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–60. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Available at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JS, Dvorak RD, Merrill JE, & Read JP (2012). Dimensions and severity of marijuana consequences: Development and validation of the Marijuana Consequences Questionnaire (MACQ). Addictive Behavior, 37, 613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag-Padilla L, Dunbar MS, Seelam R, Kase CA, Setodji CM, & Stein BD (2017). California Community College faculty and staff help address student mental health issues. RAND Research Report (RR-2248-CMHSA). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, & Lowe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, & Kerr WC (2015). Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the national alcohol survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 872–879. doi: 10.1111/acer.12698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54) Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Tembo C, Burns S, & Kalembo F (2017). The association between levels of alcohol consumption and mental health problems and academic performance among young university students. PLoS One, 12: e0178142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, & Patrick ME (2018). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among young adult drinkers: Age-specific changes in prevalence from 1977 to 2016. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42, 2224–2233. doi: 10.1111/acer.13879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2014). Alcohol and marijuana use patterns associated with unsafe driving among U.S. high school seniors: High use frequency, concurrent use, and simultaneous use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 378–389. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Merrin GJ, Ames ME, & Leadbeater B (2018). Marijuana trajectories in Canadian youth: Associations with substance use and mental health. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 50, 17–28. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Martino SC, & Klein DJ (2005). Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues, 35, 307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vanheusden K, van Lenthe FJ, Mulder CL, van der Ende J, van de Mheen D, Mackenbach JP, & Verhulst FC (2008). Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and internalizing and externalizing problems in young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 49–57. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Kilmer JR, Fossos-Wong N, Hayes K, Sokolovsky AW, & Jackson KM (2019). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among college students: Patterns, correlates, norms, and consequences. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43, 1545–1555. doi: 10.1111/acer.14072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Dodge KA, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2010). A parallel process growth mixture model of conduct problems and substance use with risky sexual behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111, 207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasek AM, Aston ER, & Metrik J (2017). Co-use of alcohol and cannabis: A review. Current Addiction Reports, 4, 184–193. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0149-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]