Abstract

Childhood economic disadvantage is associated with lower cognitive and social-emotional skills, reduced educational attainment, and lower earnings in adulthood. Despite these robust correlations, it is unclear whether family income is the cause of differences observed between children growing up in poverty and their more fortunate peers, or whether these differences are merely due to the many other aspects of family life that co-occur with poverty. Baby’s First Years (BFY) is the first randomized controlled trial in the U.S. designed to identify the causal impact of poverty reduction on children’s early development. One thousand low-income mothers of newborns were enrolled in the study, and began receiving an early childhood monthly unconditional cash gift. Mothers were randomized to receive either a large monthly cash gift or a nominal monthly cash gift. All monthly gifts are administered via debit card, and may be freely spent with no restrictions. BFY aims to answer whether poverty reduction in early childhood (1) improves children’s developmental outcomes and brain functioning, and (2) improves family functioning and better enable parents to support child development. Here we present the rationale and design of the study, as well as potential implications for science and policy.

Article summary:

The Baby’s First Years study is the first randomized controlled trial designed to identify the causal impact of poverty reduction on early childhood development.

Introduction

Early life experience has a profound and enduring influence on the developing child. Family economic resources shape the nature of many early experiences, which may explain the negative correlations between child poverty and cognitive skills, educational attainment and earnings in adulthood, as well as self-regulation and other socio-emotional skills.2 Despite robust correlations, it is unclear whether family income is the cause of cognitive and behavioral differences observed between children growing up in poverty and their more fortunate peers, or whether differences are the product of other aspects of family life that co-occur with poverty.

Social science research has generated considerable evidence that supports such causal inferences 3. In the U.S. and Canada, quasi-experimental studies that take advantage of boosts in income from casino disbursements4 and tax credits5, 6 find that the resulting increases in income are associated with improved achievement and schooling outcomes for low-income students. Welfare-to-work policy experiments found that a $4,000 increase in annual income (in current dollars) for 2–3 years led to increased school achievement by .16 standard deviations.7

Globally, conditional cash transfers (CCTs), which reward meeting certain behavioral benchmarks with cash payments, have been shown to increase school attendance and preventive medical care.8 While CCTs often produce improvements in children’s education and health, it is unclear whether this is due to completing the targeted benchmarks or to the payments themselves. Unconditional cash transfers, in which money is paid with no strings attached, also show promise in reducing material hardship and increasing entrepreneurial and educational investments,9, 10 but effects on child well-being are not well understood.

The question of whether poverty has a causal effect on child development has also been informed by neuroscience, in identifying plausible biological pathways related to the experience of poverty.11 Studies have documented associations between family income and children’s language, memory, executive function and socio-emotional processing early in childhood.11–15 Extensions of this work have examined the extent to which poverty is related to the structure and function of brain networks that support these skills16–20. Several large studies have reported a positive association between family income and the surface area of the cerebral cortex, particularly in regions supporting children’s language and executive functioning21, 22. This association is strongest among the most economically disadvantaged families, suggesting that modest differences in family income among economically disadvantaged families may be associated with disproportionately greater differences in brain structure.21

Research in both the social sciences and neuroscience find strikingly consistent associations between family income and children’s achievement, behavior and brain development.23 However, correlational or quasi-experimental studies cannot provide unequivocal evidence that increasing family income would support children’s developmental trajectories.24 Establishing whether poverty reduction has a causal impact on child development is of crucial importance for policy and practice: Should interventions and policies target poverty reduction directly, or should policies focus on other aspects of family life experienced by children living in poverty? A careful randomized control trial (RCT) is ideal for answering this causal question. Although it would be unethical to assign some families to reside in poverty and others not, it is feasible to provide different levels of cash support to randomly assigned groups of low-income families. The Baby’s First Years study is doing just that.

Baby’s First Years (BFY; www.babysfirstyears.com) is the first RCT in the U.S. designed to identify the causal impact of poverty reduction on early childhood development. It does so by randomizing low-income mothers of newborns to receive a monthly unconditional cash gift of either $333/month or $20/month for the first several years of their child’s life. BFY aims to answer whether providing a large unconditional cash gift to low-income mothers (1) improves children’s developmental outcomes, and (2) better enables parents to support child development.

We hypothesized two main pathways that may mediate a causal relationship between poverty reduction and children’s development. First, families with higher incomes may be better able to purchase or produce high-quality inputs to support young children’s development.25 This investment pathway suggests that children may experience more enriching early environments when their families have more financial resources. Second, economic disadvantage can impair child development through a stress pathway. This includes effects on parents’ well-being and mental health, the quality of family relationships and interactions,26–28 and biological indices of chronic stress.29–32 These hypothesized pathways differ in developmental mechanisms, but overlap with and reinforce one another. For example, both increased material resources and improved parental mental health may result in higher quality care, more cognitively enriching and nurturing parenting, and more visits for preventive medical care. Moreover, downstream effects may be bidirectional; e.g., when children are more verbal, parents may be more likely to talk and read books with them.33

The BFY intervention

The BFY intervention was designed by an interdisciplinary team of economists, neuroscientists, and developmental psychologists. The group first met in August, 2012, nearly six years before study enrollment began, and, in early 2013, began holding weekly meetings focused on study design and fundraising from both federal and private sources. (The cash gifts were funded exclusively through private philanthropic charities.) In 2014, we also conducted a 30-mother pilot study to demonstrate feasibility34.

The BFY intervention consists of a monthly cash gift disbursed to low-income mothers of newborns. The gifts began shortly after the birth of the child, at which time they were told the gifts would continue for the first 40 months of the child’s life. (As described below, the gifts are now being extended for an additional year.) Mothers in the treatment group (termed the “high-cash gift group”) receive monthly gifts of $333 (approximately $4,000/year). The cash gift is automatically loaded on an electronic debit card, branded as the “4MyBaby card,” and is disbursed on the day of the month of the child’s birthday. To put the magnitude of these gifts in context, an extra $4,000/year in cash gifts would increase the annual income of a family of three residing in poverty by approximately 20%. The control group (termed the “low-cash gift group”) also receives a cash gift on a debit card in the amount of $20/month, or $240/year, delivered in the same manner. A debit card is used for both groups to minimize confounding the effect of the monthly gift with the experience of having a debit card – which could, for example, promote connections with financial institutions.

The debit cards can be used widely at ATMs or for any point-of-sale transaction in person or online. Mothers receive a text message each month when the gift is automatically loaded onto the card. The receipt of these monthly gifts for approximately four years corresponds to a medium-term time horizon for mothers’ decision-making around spending or saving. The capstone child outcome data collection (a lab-based data collection, described below) is scheduled to occur before the final cash gift is disbursed.

The difference between the amount received by the high-cash gift group versus the low-cash gift group amounts to $313/month, or $3,756/year. This amount would increase the annual income of the average family in our study at baseline by approximately 21%, and was chosen because it is similar in magnitude (in today’s dollars) to annual amounts received by families in welfare-to-work experiments, which produced improvements of .15 to .20 standard deviations on the achievement of preschool to school-aged children.7, 35 Studies of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which on average is a $3,200 lump sum income transfer to families with children, also show similar impacts on children’s cognitive outcomes.5

The cash gift carries no spending restrictions, nor is it coupled with services such as financial literacy or mental health counseling. These choices were deliberate, as placing limitations on how the money is awarded or spent, or coupling the cash gift with other services, would compromise our ability to pinpoint the causal impact of poverty reduction.

Study Design

Site selection and point of recruitment.

Participating mothers were recruited from 12 hospitals in four metropolitan areas: New York City, New Orleans, the greater Omaha metropolitan area, and the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Selection of these metropolitan areas, termed “sites,” was guided by a desire to enroll a racially and ethnically diverse sample of low-income mothers across geographic regions that vary in cost of living and generosity of state safety net programs. We chose sites that had local neuroscience expertise for the capstone data collection, and where we could secure approvals from state or local officials to ensure that participants would not lose eligibility for public benefits due to the cash gift, including TANF, SNAP, Medicaid, child care subsidies, and Head Start. In two of the sites, we secured state legislation to ensure this; in the other sites, we relied on other administrative strategies.

Mothers were recruited from the hospitals where they gave birth, allowing us to disburse cash gifts to all recruited mothers a day or two after childbirth, and maximizing the likelihood that families were representative of low-income communities served by the hospital. We elected not to recruit prenatally as engagement with prenatal care varies, whereas the vast majority of births occur in hospitals.35

Inclusion criteria.

BFY sample recruitment was restricted to mothers of newborns whose self-reported income in the prior calendar year below the federal poverty line. Additional study inclusion criteria were: (1) mother was of legal age for informed consent (age 18 or older in NY, MN and LA; 19 or older in NE); (2) infant was admitted to the newborn nursery, and not the NICU; (3) mother was residing in the state of recruitment (needed to ensure the cash gift would not count for eligibility for public benefits); (4) mother reported not being “highly likely” to move to a different state or country within 12 months; (5) infant was discharged in the custody of the mother; and (6) mother spoke either English or Spanish (necessary for measurement of some child outcomes).

We did not exclude or oversample certain subpopulations, including first-time mothers, because there is no theoretical basis for anticipating the impact of the cash gift to differ between such subpopulations. On one hand, the target child may benefit more from the monthly gift if there are fewer children in the household. Additionally, because first-time parents tend to be younger and more likely to be employed in entry-level jobs, the economic conditions of first-birth children are, on average, worse than for higher-parity children. The cash gift may thus be particularly helpful for these families. However, because first-time parents tend to be younger, they may have less experience with finances and family budgets than older mothers of higher-parity births. These competing considerations, coupled with the desire to maximize generalizability, led us to opt for full representation of children irrespective of birth parity.

Ethical issues.

The Institutional Review Board of Teachers College, Columbia University has served as the single IRB of record for most of the study sites. To meet local requirements, stand-alone IRB reviews were conducted in 5 of the 12 recruitment hospitals.

To address ethical concerns regarding the possibility that cash gifts might coerce mothers to participate in research-based data collections, informed consent to participate in the research was uncoupled from agreement to receive the monthly cash gift. Interviewers first described the longitudinal research study focused on child development and family life. After mothers consented to participate and were compensated for completing the baseline survey, the mothers were offered the opportunity to receive a monthly cash gift. Mothers who agreed then learned their treatment group assignment, and their debit card was activated. We sought optional consent to collect state and local administrative data regarding parental employment, utilization of public benefits such as Medicaid and SNAP, and involvement in child protective services, as well as consent to track financial transactions on the debit card. In a debriefing at the end of the hospital visit, mothers were told that the study randomly assigned $333 or $20 monthly cash gifts.

In each site, we established a Community Engagement Board to promote communication about the study with local community stakeholders. The goal of these Boards is to facilitate feedback from the local communities on study procedures and findings as they emerge, in the context of local communities and audiences.

Data collection waves.

The study was designed to collect data from families in four waves. Original plans included a baseline wave of data collection in the hospital shortly after the child was born, an in-person home visit at child ages 12 and 24 months, and a university-based lab visit at child age 36 months. (Modifications in light of the pandemic are described below.)

To understand how poverty reduction affects child development and family life, these data collection activities were organized around the theory of change described above. Specifically, the measures of the investment pathway focused on what money might buy, while measures of the stress pathway focused on maternal stress, mental health, and well-being. Both the investment and stress pathways were expected to impact parenting practices (Table 1). Child outcomes include children’s cognitive, emotional, and neurobiological development, including stress physiology and brain function. Survey self-report was intended to be combined with objective measures and assessments, including biological samples to assess stress physiology, video-recorded interactions of the mother and child, and assessment of child brain function, as indexed by electrophysiological measures (resting electroencephalography and event-related potentials). Participants could elect not to participate in all or part of a research wave; unless they formally opt out of the study altogether, contact will still be attempted for the next wave. They were told explicitly that opting out of part or all of the research would not lead to cessation of the cash gift.

Table 1:

Child Outcomes and Conceptually-Related Family Processes

| CHILD OUTCOMES |

|---|

| Language Development |

| Social-Emotional Development |

| Executive Function and Self-Regulation |

| Child Health |

| Child Sleep |

| IQ |

| Brain Function |

| FAMILY INVESTMENT PATHWAY MEASURES |

| Economic well-being |

| Household income |

| Indicators of economic hardship |

| Food insufficiency |

| Assets and debt |

| Household expenditures |

| Receipt of social services and public benefits |

| Neighborhood quality |

| Neighborhood poverty |

| Perceptions of neighborhood safety (safety, victimization) |

| Excessive residential mobility |

| Housing quality |

| Crowding/number of rooms |

| Type of housing |

| FAMILY STRESS PATHWAY MEASURES |

| Family stress |

| Chaos in the home |

| Maternal perceived stress |

| Parenting stress |

| Global happiness |

| Maternal agency |

| Mother-father relationship |

| Maternal hair cortisol |

| Maternal cognitive bandwidth |

| Maternal depression |

| Maternal anxiety |

| Maternal substance use |

| Sensitivity of parenting |

| Index of positive parenting behaviors (affection and responsiveness) |

| Spanking discipline strategy |

| Child stress measures |

| Child hair cortisol |

| Child epigenetic age and DNA methylation |

| RELATED FAMILY PROCESSES AND OTHER MEASURES |

| Mother demographics |

| Father demographics |

| Household roster |

| Maternal education and training |

| Parental work histories and schedules |

| Total hours (full or part time) |

| Number of jobs |

| Days worked |

| Regularity of work schedule |

| Maternity leave (time to labor market reentry after giving birth) |

| Breastfeeding practicesCHILD OUTCOMES |

| Home language exposure |

| Maternal physical health |

| Maternal reproductive health |

| Maternal experience of Covid-19 |

| Experience of structural racism |

Because of the pandemic, data collection has been modified in several ways. For some participants in the 12-month data collection wave and all participants in the 24-month wave, data collection has been limited to phone interviews. In addition, we added a number of survey questions to better understand families’ pandemic-related experiences, including changes in health and employment. While the pandemic changed the context of the study in complicated ways, the experimental design ensures the ability to estimate the causal impact of the cash support provided to participants. We will attempt to understand pandemic-related differences in family life and economic disruptions, noting the analytical challenges around disambiguating the onset of these changes from the change of in-person data collection to phone interviews.

As of this writing, we have raised funds to extend the cash gifts for an additional year, enabling us to separate the capstone wave of data collection – originally planned for 36 months – into a phone survey that will be administered at 36 months, and a lab-based in-person assessment that will take place approximately a year later, around the child’s 4th birthday. This was necessary because the pandemic rendered uncertain our ability to carry out high-quality, in-person data collection as originally planned at 36 months. The capstone visit will include lab-based assessments of children’s cognitive development and brain functioning, maternal and child stress physiology, and maternal and child BMI, along with survey-based measures of maternal and child health and well-being.

In addition to the four planned follow-up waves of quantitative data collection, qualitative semi-structured interviews are being conducted with 80 randomly selected mothers in two of the four sites. Three interviews will occur over the course of the study, with a final interview scheduled after the cessation of the gifts. The goal of these interviews is to capture mothers’ voices and their views and experiences of the cash gift in an open-ended narrative format.

Table 1 includes the child outcomes measured, as well as investment and stress pathway measures. Pre-registration details can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03593356. In keeping with best open science practices, data are being deposited with the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR).

Statistical power.

Striking a balance between statistical power and project costs, we allocated 40% of the sample to receive the $333 monthly cash gifts and 60% to receive the $20 monthly gifts. With the sample size of n=1,000 mother-infant-dyads, and after accounting for a predicted 20% attrition by the capstone wave of data collection, the anticipated sample size of 800 dyads will provide 80% power to detect a .207 sd impact at p <.05 in a two-tailed test on cognitive functioning and family process outcomes, noting that the literature on income effects on family process measures is much less extensive than the literature on child outcomes, reviewed above.

Baseline recruitment and data collection

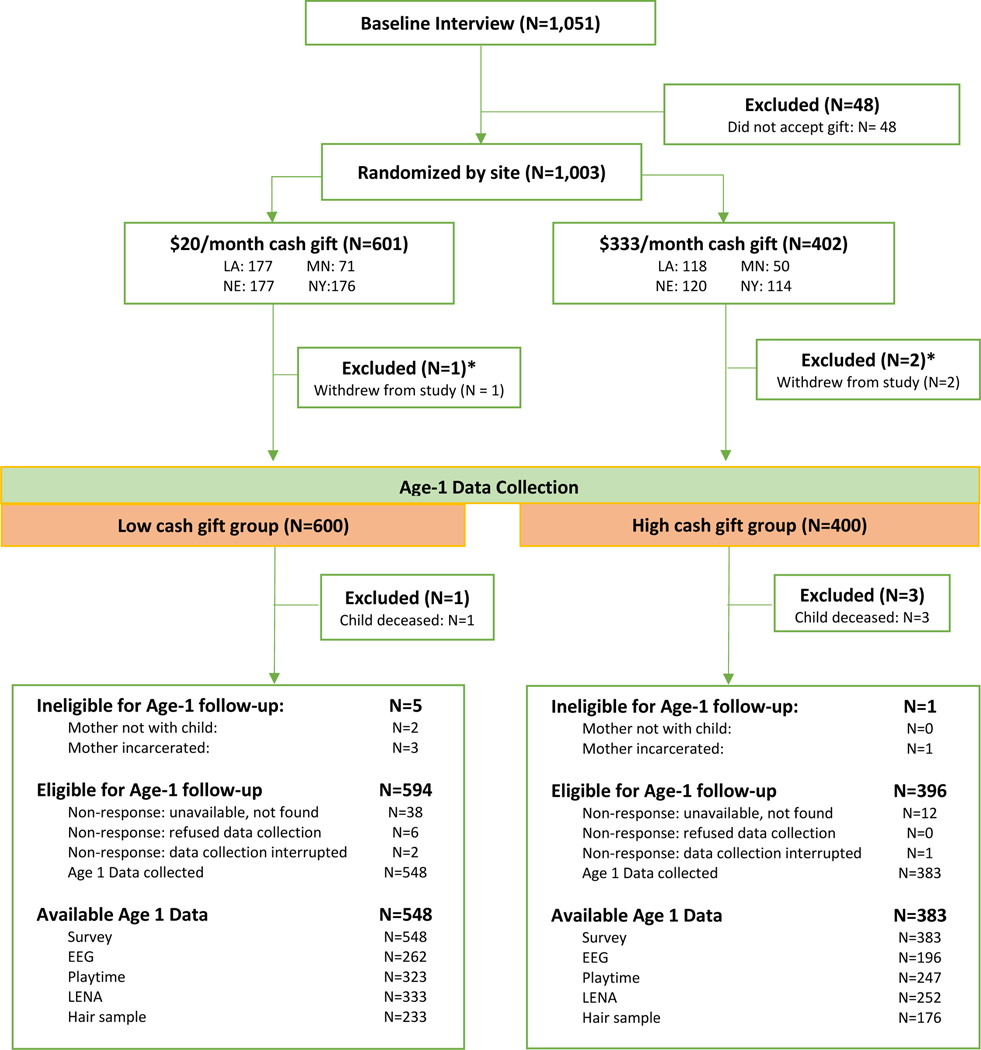

Between May 2018 and June 2019, all 1,000 mother-infant-dyads were recruited. The baseline CONSORT diagram details how the sample was constructed (Appendix Figure 1). Recruitment took place at each recruitment hospital several days per week over the course of the year. On recruitment days, nurses in the well-baby nurseries of the hospitals were asked for a list of all admitted mothers who had given birth at that hospital within the past three days, excepting any mothers who, for medical or other reasons, they felt should not be approached to participate in research. A total of 13,483 mothers were identified, 8,243 of whom agreed to be assessed for eligibility through a brief screener. Of these, 6,839 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 341 declined to consent. A baseline interview was completed with the remaining 1,051 mothers. Of these 1,051 mothers, 1,003 agreed to receive cash gifts and were randomized into the high-cash or low-cash gift groups. Randomization into the high-cash or low-cash group occurred at the site level. Of the 1,003 mothers who were randomized, 3 were excluded because they notified the interviewer within two days after completing the baseline interview that they wanted to withdraw and stop receiving cash gifts. The result is our final sample of 1,000 mothers and infants.

Our intention was to recruit 250 mother-infant-dyads in each of the four sites. Owing to a number of IRB and hospital-related recruiting challenges, the sample is distributed as follows: 295 mother-infant pairs in New Orleans, 295 in the greater Omaha area, 289 in New York, and 121 from the Twin Cities. For the qualitative interviews, 60 mothers were drawn from New Orleans and 20 from the Twin Cities. As described below, the majority of participants are women of color.

Baseline equivalence of the high- and low-cash gift groups.

Appendix Table 1 shows means (and, for continuous variables, standard deviations), plus sample sizes, of preregistered baseline characteristics. Standardized mean differences between treatment and control groups are indicated by Hedge’s g for continuous variables and by Cox’s index for dichotomous variables. The p-values shown in the final column were generated from regressing cash gift group status on covariates generated from the baseline data, including site fixed effects, with robust standard errors. Of the 26 individual tests, two have a p < .05. The best indicator of overall baseline balance is given by the p-value of a joint test of orthogonality from a probit model with robust standard errors and site-level fixed effects. As shown in Appendix Table 1, the p-value is .238, indicating that high- and low-cash-gift groups were very similar to one another at baseline. All baseline covariates are included in our pre-specified intent-to-treat models.

Appendix Table 1. Baseline Balance across Baseline Measures Between High and Low Cash Gift Groups.

Full Sample (n = 1000)

| Full Sample (n = 1000) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Low Cash Gift | High Cash Gift | Std Mean Difference | |||||

| Mean (sd) | N | Mean (sd) | N | Hedges’ g | Cox’s Index | p-value | |

|

| |||||||

| Child is female | 0.50 | 600 | 0.48 | 400 | −0.06 | 0.458 | |

| Child weight at birth (pounds) | 7.13 | 599 | 7.09 | 399 | −0.04 | 0.567 | |

| (1.08) | (1.01) | ||||||

| Child gestational age (weeks) | 39.09 | 596 | 39.04 | 399 | −0.04 | 0.512 | |

| (1.25) | (1.24) | ||||||

| Mother age at birth (years) | 26.80 | 600 | 27.38 | 400 | 0.10 | 0.113 | |

| (5.82) | (5.86) | ||||||

| Mother education (years) | 11.88 | 593 | 11.88 | 398 | −0.00 | 0.978 | |

| (2.83) | (2.96) | ||||||

| Mother race/ethnicity: white, non-Hispanic | 0.11 | 600 | 0.09 | 400 | −0.17 | 0.128 | |

| Mother race/ethnicity: Black, non-Hispanic | 0.40 | 600 | 0.44 | 400 | 0.11 | 0.091 | |

| Mother race/ethnicity: multiple, non-Hispanic | 0.04 | 600 | 0.03 | 400 | −0.18 | 0.369 | |

| Mother race/ethnicity: other or unknown | 0.05 | 600 | 0.03 | 400 | −0.37 | 0.066 | |

| Mother race/ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.41 | 600 | 0.41 | 400 | 0.01 | 0.594 | |

| Mother marital status: never married | 0.42 | 600 | 0.49 | 400 | 0.18 | 0.024 | |

| Mother marital status: single, living with partner | 0.26 | 600 | 0.22 | 400 | −0.14 | 0.119 | |

| Mother marital status: married | 0.21 | 600 | 0.21 | 400 | 0.02 | 0.791 | |

| Mother marital status: divorced/separated | 0.05 | 600 | 0.03 | 400 | −0.37 | 0.064 | |

| Mother marital status: other or unknown | 0.06 | 600 | 0.04 | 400 | −0.18 | 0.400 | |

| Mother health is good or better | 0.88 | 600 | 0.92 | 400 | 0.25 | 0.041 | |

| Mother depression (CESD) | 0.68 | 600 | 0.69 | 400 | 0.02 | 0.805 | |

| (0.45) | (0.46) | ||||||

| Cigarettes per week during pregnancy | 5.05 | 595 | 3.45 | 397 | −0.09 | 0.111 | |

| (21.17) | (11.76) | ||||||

| Alcohol drinks per week during pregnancy | 0.17 | 598 | 0.03 | 399 | −0.11 | 0.052 | |

| (1.63) | (0.39) | ||||||

| Number of children born to mother | 2.40 | 600 | 2.53 | 400 | 0.09 | 0.146 | |

| (1.38) | (1.41) | ||||||

| Number of adults in household | 2.12 | 600 | 2.03 | 400 | −0.09 | 0.156 | |

| (1.00) | (0.96) | ||||||

| Biological father lives in household | 0.40 | 600 | 0.35 | 400 | −0.12 | 0.154 | |

| Household combined income | 22,466 | 562 | 20,918 | 370 | −0 | 0.219 | |

| (21,360) | (16,146) | ||||||

| Household income unknown | 0.06 | 600 | 0.07 | 400 | 0.14 | 0.482 | |

| Household net worth | −1,981 | 531 | −3,308 | 358 | −0 | 0.423 | |

| (28,640) | (20,323) | ||||||

| Household net worth unknown | 0.12 | 600 | 0.10 | 400 | −0.09 | 0.644 | |

|

| |||||||

| Joint Test: Chi2(30)= 34.02, p-value= 0.238, n=1000. | |||||||

Notes: P-values were derived from a series of OLS bivariate regressions in which each respective baseline characteristic was regressed on the treatment status indicator using robust standard errors and site-level fixed effects. The bivariate regressions were also run without site-level fixed effects, and the p-values differed on average by 0.011. The p-values without fixed effects do not appear in the table. The joint test of orthogonality was conducted using a probit model with robust standard errors and site-level fixed effects.

Standardized mean differences were calculated using Hedges’ g for continuous variables and Cox’s Index for dichotomous variables.

If there were more than 10 missing cases for a covariate, missing data dummies were included in the table and the joint test. If fewer than 10 cases were missing, missing data dummies were not included in the table but were included in the joint test.

Chi-square tests of independence were conducted for the two categorical variables: mother race/ethnicity and mother marital status. For both tests, p>0.05

Contributions to science

The Baby’s First Years study is the first large-scale U.S. experiment involving unconditional cash transfers to low-income families with young children. As such, BFY is poised to provide the strongest evidence to date as to whether family income in and of itself is the cause of many of the negative outcomes faced by children living in poverty. BFY improves on prior research by employing a rigorous RCT design, which directly tests the impact of income – disbursed without restrictions or instructions – on child development and family life. Further, by targeting families during children’s earliest years, BFY will provide important evidence of the effect of income during a time when children’s brains are particularly sensitive to experience.

Contributions to policy

Findings will inform policy at the national, and state and local levels. The BFY cash gifts are structurally related to child allowances found in most industrialized nations.3 Historically, the U.S. has had a Child Tax Credit (CTC) for lower- and middle-income families but not for families with little or no taxable income. Since 2017, the CTC benefit amounted to $2,000 per child per year. The 2021 American Rescue Plan increased CTC benefit levels to $3,600 per year for children under 6, and $3,000 per year for children 6 years and older. Importantly, the legislation extended CTC payments to almost all low-income families, regardless of their taxable income, converting the CTC into a child allowance available to all but the wealthiest families.

BFY cash gifts differ in several key ways from the expanded CTC. Perhaps most notably, the BFY $4,000 annual payments are the same for all families regardless of the number of children, whereas the new federal policy provides a similarly-sized payment for each child in the family, and thus has the potential to increase family income much more than BFY payments. For BFY participants, the cash gifts are automatic, monthly and predictable, whereas the first year of federal payments consist of a combination of monthly and lump-sum payments, and will require families that have not previously paid taxes to formally file.

While BFY will provide some evidence on the likely impact of cash transfer policies in the first several years of life, several elements of the study limit its ability to inform debates over these kinds of policies. Our branding of the debit card with “4MyBaby” may shape mothers’ views about the money differently than a government-delivered refundable child tax credit. As with any research study, participants’ behavior may be altered because of their awareness of being observed.

The generalizability of findings from any study are limited by conditions and events during the study period. Most BFY newborns spent the two years of life in a booming economic environment, followed by a pandemic-induced shutdown that included two stimulus payments sent to most families. The impacts of BFY payments may well be reduced during favorable economic periods and enhanced during economic downturns.

The incomes of most families during the third and possibly subsequent years of BFY children’s lives will be boosted by the expanded CTC. Indeed, CTC payments for families with multiple children will be especially large. While this does not threaten the internal validity of the study, it is possible that the increased incomes of both high- and low-cash gift groups will mitigate impacts of the BFY cash gifts on child development. Past studies do not provide clear evidence on the family income threshold at which the added $4,000 of BFY money begins to matter less for children’s development. Additionally, some implementation details about the expanded CTC are unknown at the time of this writing, including likely uptake among families who have not previously paid taxes or who do not have a bank account.

Both the expanded CTC, as well as prior stimulus payments and other programs expanded through legislation, will have varied and complicated economic impacts. Critically, BFY’s randomized design means that, while the context of the BFY cash gift is shifting, we will still learn a great deal about whether providing reliable monthly financial support to low-income families will help their children have a healthier start in life.

A broader limitation is vital to bear in mind: Policies that provide financial resources to families are only one of many kinds of programs and policies that promote the well-being of children. Although we concentrate our attention on cash transfers, we note the vital role for programs and policies that provide health services, parenting support, early education36 and other services to low-income families with young children.

Bearing these limitations in mind, Baby’s First Years is the first study to provide clear, causal, U.S.-based evidence on the consequences of poverty reduction on early childhood development, with direct implications for policy. Traditionally, discussions of such policies in the U.S. have centered on effects on labor supply rather than child well-being. BFY will be important in shifting the focus of the conversation toward how best to support children.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge Lauren Meyer, for leadership and direction as the National Project Director of the study, as well as Andrea Karsh, for budgetary and organizational assistance. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Sonya V. Troller-Renfree, for invaluable assistance with piloting, training, and data analysis, as well as helpful edits of the current manuscript. We thank the University of Michigan Survey Research Center, our partners in recruitment and data collection. Finally, we recognize the state and local agencies and administrators who made it possible to distribute cash gifts while ensuring that study participants would not, as a result, lose eligibility for public benefits.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH R01HD087384–01, as well as by grants from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Brady Education Foundation, the Child Welfare Fund, the Ford Foundation, the Greater New Orleans Foundation, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, the JPB Foundation, the Louisiana Foundation, the New York City Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Perigee Fund, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Sherwood Foundation, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, the Valhalla Foundation, the Weitz Family Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and three anonymous donors.

The funders did not participate in the work.

Abbreviations:

- BFY

Baby’s First Years

APPENDIX

Appendix Figure 1. Age-1 Consort Diagram.

*Participants withdrew from study prior to spending any money on card and only a few days after randomization. Thus, they were not considered as the target sample for future waves of data collection.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical Trial registry:

Data are deposited with the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37871.v2)1.

Contributor Information

Dr. Kimberly G. Noble, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Dr. Katherine Magnuson, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Dr. Lisa A. Gennetian, Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy.

Dr. Greg J. Duncan, University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Hirokazu Yoshikawa, New York University.

Dr. Nathan A. Fox, University of Maryland.

Dr. Sarah Halpern-Meekin, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- 1.Magnuson K, Noble KG, Duncan G, Fox NA, Gennetian LA, and Yoshikawa H. Baby’s First Years (BFY), New York City, New Orleans, Omaha, and Twin Cities, 2018–2019. Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research; [distributor]; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. American Psychologist. 2012;67(4):272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akee RKQ, Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Parents’ incomes and children’s outcomes: A quasi-experiment using transfer payments from casino profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2(1):86–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl G, Lochner L. The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from changes in the Earned Income Tax Credit. American Economic Review. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milligan K, Stabile M. Do child tax benefits affect the well-being of children? Evidence from Canadian child benefit expansions. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2011;3(3):175–205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan GJ, Morris PA, Rodrigues C. Does money really matter? Estimating impacts of family income on young children’s achievement with data from random-assignment experiments. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(5):1263–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiszbein A, Schady NR, Ferreira FH. Conditional cash transfers: reducing present and future poverty: World Bank Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird S, Ferreira FH, Woolcock M. Relative effectiveness of conditional and unconditional cash transfers for schooling outcomes in developing countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2013;9(8). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A, Duflo E, Goldberg N, Karlan D, Osei R, Parienté W, et al. A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science. 2015;348(6236):1260799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science. 2007;10(4):464–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble KG, Norman MF, Farah MJ. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Developmental Science. 2005;8(1):74–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farah MJ, Shera DM, Savage JH, Betancourt L, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, et al. Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Research. 2006;1110(1):166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisleder A, Fernald A. Talking to children matters: early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science. 2013;24(11):2143–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowe ML. Child-directed speech: relation to socioeconomic status, knowledge of child development and child vocabulary skill. Journal of Child Language. 2008;35(01):185–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomalski P, Moore DG, Ribeiro H, Axelsson EL, Murphy E, Karmiloff-Smith A, et al. Socioeconomic status and functional brain development – associations in early infancy. Developmental Science. 2013;16(5):676–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmony T, Marosi E, Díaz de León AE, Becker J, Fernández T. Effect of sex, psychosocial disadvantages and biological risk factors on EEG maturation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1990;75(6):482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brito NH, Fifer WP, Myers MM, Elliott AJ, Noble KG. Associations among family socioeconomic status, EEG power at birth, and cognitive skills during infancy. Developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2016;19:144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otero GA. Poverty, cultural disadvantage and brain development: A study of preschool children in Mexico. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1997;102:512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otero GA, Pliego-Rivero FB, Fernandez T, Ricardo J. EEG development in children with sociocultural disadvantages: a follow-up study. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114(10):1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, Bartsch H, Kan E, Kuperman JM, et al. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18(5):773–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDermott CL, Seidlitz J, Nadig A, Liu S, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, et al. Longitudinally Mapping Childhood Socioeconomic Status Associations with Cortical and Subcortical Morphology. Journal of Neuroscience. 2019;39(8):1365–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farah MJ. The Neuroscience of Socioeconomic Status: Correlates, Causes, and Consequences. Neuron. 2017;96(1):56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noble KG, Giebler MA. The neuroscience of socioeconomic inequality. Current opinion in behavioral sciences. 2020;36:23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker GS, Becker GS. A Treatise on the Family: Harvard university press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73(3):935–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):206–219. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist. 2004;59(2):77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1238–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Uum S, Sauvé B, Fraser LA, Morley-Forster P, Paul TL, Koren G. Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: A novel biomarker for stress. Stress. 2008;11(6):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dettenborn L, Tietze A, Kirschbaum C, Stalder T. The assessment of cortisol in human hair: associations with sociodemographic variables and potential confounders. Stress. 2012;15(6):578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8(04):597–600. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas NM, Yoshikawa H, Gennetian L, Lemus Rangel M, Melvin S, Noble K, et al. Exploring the experiences and dynamics of an unconditional cash transfer for low-income mothers: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Children and Poverty. 2020;26(1):64–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center https://pn3policy.org. Published 2021.