Abstract

Blind mole rats (BMRs) are small rodents, characterized by exceptionally long lifespan (> 21 years) and resistance to both spontaneous and induced tumorigenesis. Here we report that cancer resistance in the BMR is mediated by retrotransposable elements (RTEs). BMR cells and tissues express very low levels of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1). Upon cell hyperplasia, the BMR genome DNA loses methylation, resulting in activation of RTEs. Up-regulated RTEs form cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids, which activate cGAS-STING pathway to induce cell death. Although this mechanism is enhanced in the BMR, we show that it functions in mice and human. We propose that RTEs were coopted to serve as tumor suppressors that monitor cell proliferation and are activated in premalignant cells to trigger cell death via activation of innate immune response. RTEs activation is a double-edged sword, serving as a tumor suppressor but in late life contributing to aging via induction of sterile inflammation.

Naturally cancer resistant animals provide powerful models to uncover novel anti-cancer mechanisms which may be applicable to humans1. The blind mole rats, Spalax (BMR), are small, long-lived subterranean rodents found in the Middle East, with the maximum lifespan of >21 years 2, 3, 4. BMR displays strong resistance to both spontaneous and induced tumorigenesis2, 3. Our previous study demonstrated that BMR prevents cancer through a mechanism termed CCD, which is triggered by the secretion of interferon-β after 7–20 population doublings (PDs) to prevent hyperplasia2. However, the mechanism by which CCD is induced had remained unknown.

Transposable elements (TEs) are mobile repetitive sequences and major components of eukaryotic genomes5. In mammals, TEs make up 45% of the human genome6 and 37.5% of the mouse genome7, 8. The process of retrotransposition may potentially cause mutations by interrupting a gene sequence, and/or leave cleaved genome unrepaired9, 10, 11. RTEs are epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation12, 13. The DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) is responsible for maintenance of DNA methylation. DNMT1 recognizes hemimethylated CpG sites and methylates the unmethylated DNA14, 15. Multiple other mechanisms have evolved to silence RTEs (reviewed in 5). Activation of L1 due to loss of epigenetic silencing during aging and senescence has been shown to trigger sterile inflammation and cell death due to formation of cytoplasmic RTE copies that activate innate immune response16, 17, 18. Therefore, the active retrotransposition has been associated with aging and aging-related diseases.

RTEs have been investigated for their potential role in driving tumorigenesis. Large scale sequencing efforts identified multiple de novo somatic insertions in human tumors19, 20, 21. Some insertions into tumor suppressor genes such as APC in colon cancer22 and PTEN in endometrial carcinoma20 have been found and linked to the development of the cancer. However, the majority of de novo insertions in cancers appear to be passenger events23. On the contrary, emerging evidence suggests that RTEs serve as tumor suppressors. Treatment of cancer cells with demethylating agents, or LSD ablation which removes RTE silencing, triggered cell death via activation of ERVs and dsRNA sensing pathway24, 25. These studies suggest that forced reactivation of RTEs can have an antitumor effect. Recently, it was shown that L1s serve as tumor suppressors by triggering genomic instability in myeloid leukemia26.

Here we investigated the mechanisms of tumor resistance in the naturally tumor resistant rodent, the BMR. We discovered that BMR has naturally low DNMT1 activity. This results in loss of methylation on RTEs upon cell hyperplasia, leading to formation of cytoplasmic RTE RNA/DNA and cell death via the activation of cGAS-STING-interferon pathway. Furthermore, we show that this mechanism functions in mice and in human xenografts. Analysis of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database revealed that L1 activation in human cancer cells correlates positively with the number of mutations in cGAG-STING-interferon pathway providing further evidence that L1s act as tumor suppressors in human. Our study reveals a novel beneficial function of RTEs as tumor suppressors.

Results

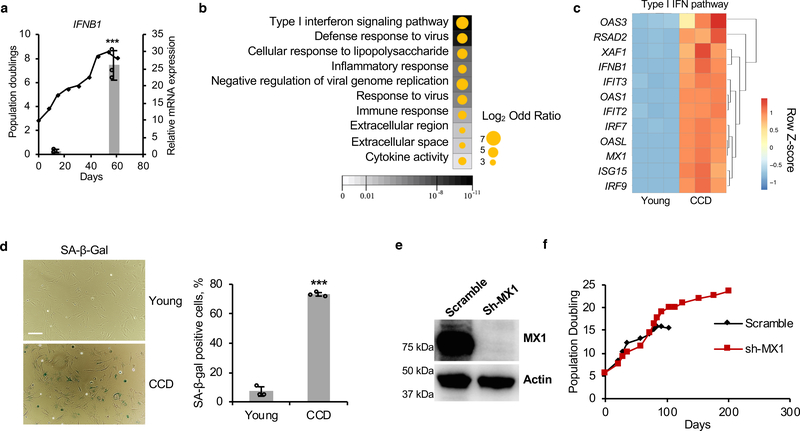

Type I IFN Pathway is Activated in BMR cells Undergoing CCD

Upon hyperproliferation primary BMR cells trigger CCD via an unknown mechanism2. To understand the mechanisms triggering CCD we compared transcriptomes of the BMR fibroblasts undergoing CCD to low passage, growing cells. The mRNA level of IFNB1 gene, which encodes interferon-β, dramatically increased before the onset of CCD (Figure 1a). Whole transcriptome RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) confirmed that type I interferon, inflammation, and immune response pathways are enriched within the most up-regulated genes (Figure 1b). A total of 12 genes from type I interferon pathway were exclusively up-regulated (Figure 1c). Immediately prior (~2 days) to the onset of CCD, the cells entered cell cycle arrest and displayed characteristics of cellular senescence as determined by senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (SA-β-Gal; Figure 1d) and expression of senescence markers and senescence-associated secretory phenotype genes (SASP; Extended Data Figures 1a, b). One of the most up-regulated genes MX1 is an interferon-inducible gene responsible for inducing cell death27. Knocking down of MX1 rescued CCD (Figures 1e, f). Therefore, CCD is triggered by type I interferon response.

Figure 1. Activation of IFN response in over-proliferating BMR cells triggers CCD.

(a) Up-regulation of IFNB1 gene expression before CCD. (b) A dot map of the top 10 Go terms of the most up-regulated genes (Fold change > 10 and false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.05) between Young versus CCD cells. Background colour represents FDR and dot size represents odd ratio (log2 transformed). (c) A heatmap showing the relative expression of all 12 up-regulated genes, by Z-scores, from Type I interferon pathway between Young and CCD cells. (d) Images and quantification of senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (SA-β-Gal) of Young and CCD cells. Scale bar, 10 μM. (e) Western blot showing knockdown of the interferon-induced gene MX1 by shRNA. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (f) Growth curve showing that knockdown of MX1 rescued CCD. Data are mean ± SD (a and d); ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

In BMR tissues, multiple immunity-related pathways are expressed at lower levels compared to mice (Extended Data Figure 1c). These pathways include CGAS, STING, multiple IRF genes from IFN pathway and Nfkb1 from the canonical NF-κB pathway (Extended Data Figure 1d). In contrast, Irf2 gene and the non-canonical NF-κB pathway gene Nfkb2, both of which negatively regulate the activation of IFN28, 29, 30, had higher expression in BMR tissues than in mice (Extended Data Figure 1d). Interestingly, many of these lower expressed genes were up-regulated in BMR CCD cells, including Nfkb1 gene and IFN pathway genes, whereas the higher expressed Nfkb2 gene was down-regulated during CCD (Figure 1c and Extended Data Figure 1e), showing opposite trend compared with normal tissues. This result suggests IFN related genes are repressed in normal BMR tissues to prevent accidental activation of CCD.

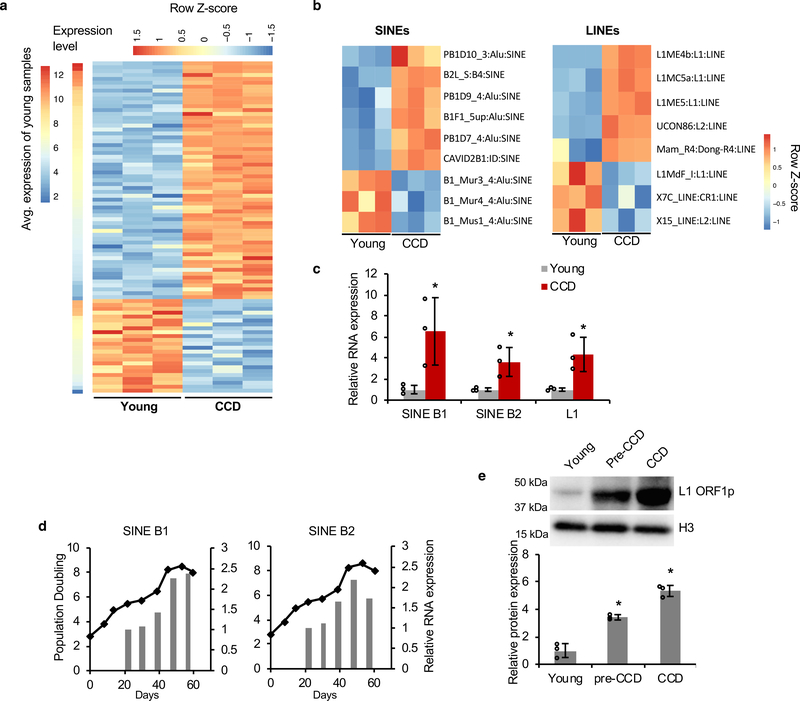

RTEs Are Activated in BMR Cells Before the Onset of CCD

Type I interferon is a major component of innate immune response. Typically, the type I interferon pathway is activated during viral infection. It can also be triggered by nuclear DNA leaking into the cytoplasm as a result of chromatin degradation or retrotransposon activity16, 17, 31. We therefore examined whether RTEs are activated during CCD. Expression of RTEs was analyzed using RNA-seq comparing low passage cells to cells entering CCD. Many RTEs were up-regulated before the onset of CCD (Figure 2a), including ERVs, SINEs and LINEs (Figure 2b). As SINEs and LINEs are highly repetitive elements, consensus sequences of SINE B1, B2, and LINE-1 (L1) were detected by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to confirm the up-regulation (Figure 2c). The PCR primers were designed to detect the consensus sequences of the major RTEs, therefore the results reflect the expression of multiple RTE groups. When tracking the expression of RTEs with the cellular proliferation, we noticed that their expression levels gradually increased with the onset of CCD (Figure 2d). We also detected increased expression of L1 ORF1 protein, which indicates that active, autonomous L1 elements, which provide reverse transcriptase for other RTEs were also derepressed (Figure 2e). To further confirm that the increase in SINE and LINE transcripts is not caused by read-through transcription, we performed 5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and found that most of the transcriptional start sites of SINE B1 are very close to its consensus Pol III promoter start site, and that of L1 are within the 5’ untranslated region (UTR) (Extended Data Figure 2).

Figure 2. Retrotransposons are activated in over-proliferating BMR cells to trigger IFN and CCD due to naturally weak DNMT1.

(a) A heatmap for differential expression of transposable elements (TEs; p-value < 0.01 & fold change > 1.5) between Young and CCD cells. TEs were sorted based on average basal expression level in Young cells for up-regulated and down-regulated TEs, separately. FDR-adjusted P values were used to determine significant differences. (b) Heatmaps showing differential expression of retrotransposons SINEs and LINEs between Young and CCD cells. For SINE elements, the number after the name of subfamily (e.g., “3” in “PB1D10_3:Alu:SINE”) indicates the number of CpGs in this element, by which instances of B1 subfamilies were further divided into sub-groups. To distinguish different instances of the same type of TE, a sequential number was manually added to the instances of the same type of TE. (c) Increased expression of SINE B1, B2 and LINE1 in BMR CCD cells. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using primers targeting the consensus sequence of rodent SINE B1, B2, and LINE1 (L1MdaI) ORF1. (d) qRT-PCR showing accumulation of SINE B1 and B2 with proliferation of BMR cells. (e) Western blot detecting L1 ORF1 showing accumulation of L1 with proliferation of BMR cells. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

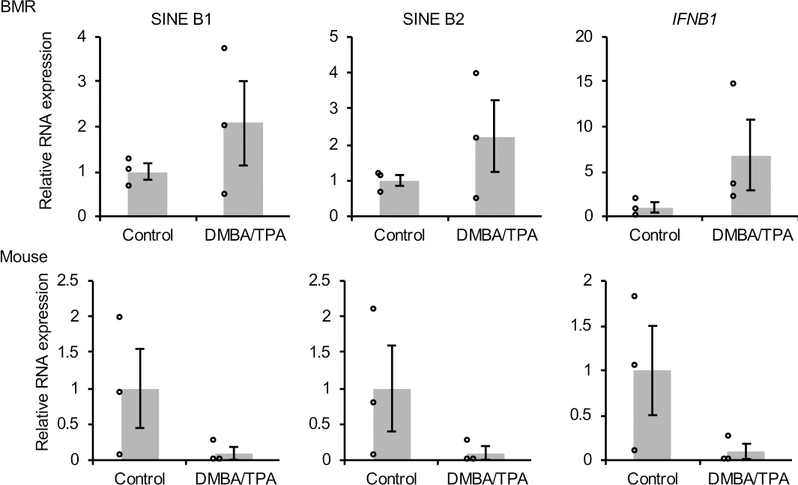

A topical tumorigenic 7,12-Dimethylbenz(a)anthracene/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (DMBA/TPA) treatment, which fails to induce skin cancer in BMR, also resulted in a general activation of RTEs and IFN expression in the treated BMR skin (Extended Data Figure 3), suggesting the IFN response observed in cell culture is involved in cancer resistance of BMR in vivo.

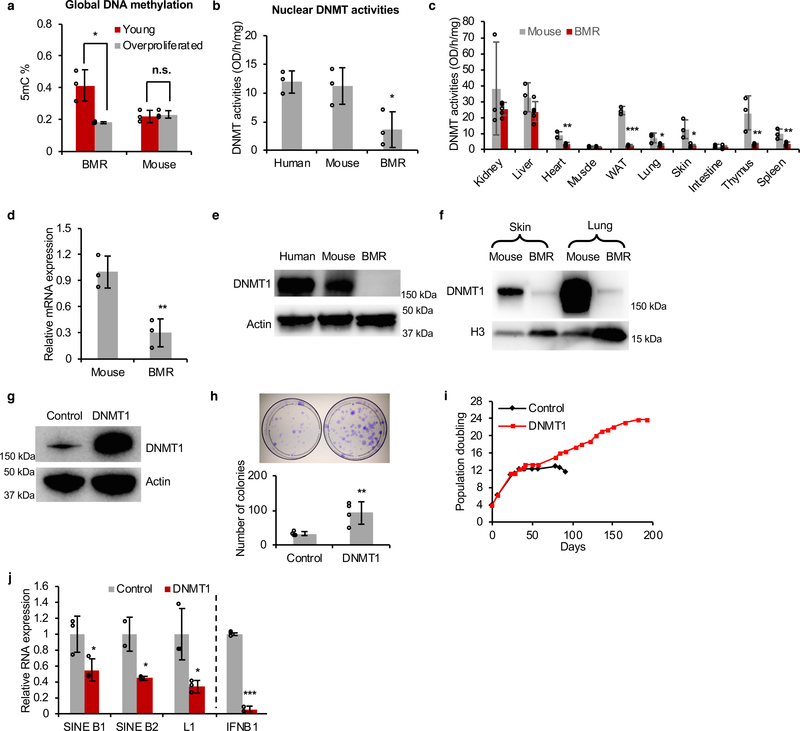

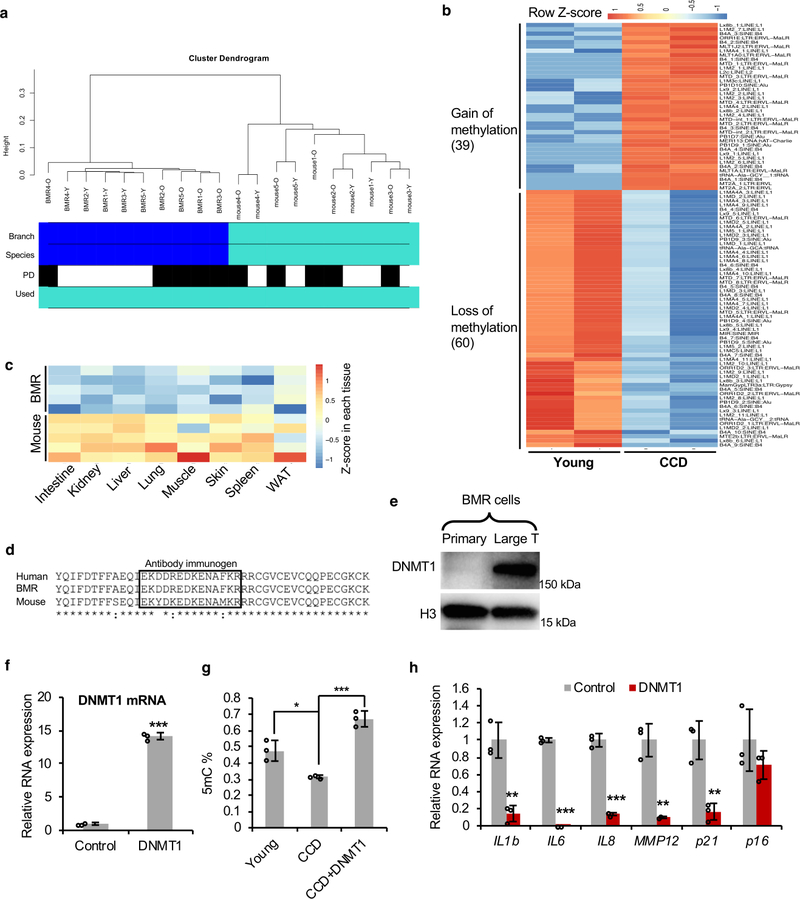

Activation of RTEs in BMR is due to Low Expression of DNMT1

As induction of RTEs may lead to genomic instability, RTEs are epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation12, 13. The spontaneous activation of RTEs in over-proliferating BMR cells indicated the loss of epigenetic silencing. Indeed, when comparing to the young cells, the global DNA methylation levels in cells undergoing CCD dropped sharply, while it remained the same in proliferating mouse fibroblasts at the same PD (Figure 3a). Using HorvathMammalMethylChip40 which profiles about 37K highly conserved CpG probes across mammals, we compared the general methylation profiles between BMR and mouse in an unbiased manner. An unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis reveals that high PD BMR cells are globally distinct from those of low PD cells, suggesting a dramatic epigenetic change with proliferation of BMR cells. In contrast, no clustering effect can be detected in mouse cells (Extended Data Figure 4a). In order to ensure the coverage of TEs, Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) was performed and confirmed that a majority of RTEs, especially SINEs and LINEs, were hypomethylated in dying BMR cells (Extended Data Figure 4b), corresponding to the up-regulation of RTEs shown by RNA-seq (Figures 2a, b). Particularly, the master sequence of SINE B1, the PB1D9 family32, was up-regulated and demethylated in CCD cells (Figures 2a, b and Extended Data Figure 4b). In mammals, DNMT1 is responsible for maintenance of DNA methylation14, 15. We compared the DNMT activities in the nuclear extracts of human, mouse, and BMR fibroblasts. While human and mouse cells had comparable nuclear DNMT activities, BMR nuclear extract had much weaker activity (Figure 3b). Nuclear extracts from multiple tissues of BMR also had weaker DNMT activities than mouse tissues (Figure 3c). Furthermore, the mRNA and protein levels of DNMT1 in BMR cells were significantly lower than those of mouse and human (Figure 3d, e). The low expression of DNMT1 was also observed in both skin and lung tissues (Figure 3f). To rule out the inter-species influence for antibody recognition, multiple alignment of DNMT1 protein was performed. The sequence of the antibody immunogen is highly conserved across human, mouse, and BMR, with identical sequences between human and BMR (Extended Data Figure 4d). Furthermore, endogenous DNMT1 from BMR cells transfected with SV40 Large T antigen (LT), which is known to elevate DNMT1 expression33, was easily detected (Extended Data Figure 4e). RNA-seq comparing between BMR and mice showed lower expression of DNMT1 mRNA of BMR in different tissues (Extended Data Figure 4c). These results suggest that BMR has naturally low expression of DNMT1.

Figure 3. Naturally weak DNMT1 in BMR is responsible for RTE induction and CCD.

(a) Lost of global DNA methylation with proliferation of BMR cells. Experiments were performed using three independent cell lines from each species. (b) DNMT activities from nuclear extract of human, mouse, and BMR fibroblasts. Experiments were performed using three independent cell lines from each species. (c) BMR has generally weaker DNMT activities in tissues. DNMT activities were detected from nuclear extract of different tissues from mouse and BMR. Experiments were performed using tissues from five BMRs and three mice. (d-e) Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (d) and western blot (e) showing that BMR cells have naturally low DNMT1 level. Experiments were performed using three independent cell lines from each species. (f) Western blot showing naturally lower level of DNMT1 protein in BMR skin and lung tissues compared with mouse. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (g) Western blot showing overexpression of human DNMT1 in BMR cells. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (h) Overexpression of DNMT1 enhanced BMR cell growth. Clonogenic assay was performed with crystal violet staining. Quantification was based on four independent experiments. (i) Overexpression of DNMT1 rescued CCD. Experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results. (j) qRT-PCR showing that overexpression of DNMT1 repressed expression of retrotransposons SINE B1, SINE B2, and LINE1 (L1), as well as IFNB1, from three independent cell lines. Data are mean ± SD. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

To investigate if the naturally weak DNMT1 is responsible for the proliferation-induced activation of RTEs, we stably overexpressed human DNMT1 with the piggyBac transposon system in the BMR fibroblasts (Figure 3g and Extended Data Figure 4f). Ectopic expression of DNMT1 not only enhanced BMR cell growth as determined by clonogenic assay (Figure 3h), but also rescued CCD (Figure 3i). As expected, DNMT1 rescued cells had restored global DNA methylation levels (Extended Data Figure 4g) and repressed expression of SINE B1, B2, L1, IFNB1 gene, and senescence factors (Figure 3j and Extended Data Figure 4h). Collectively, these results suggest that the naturally weak DNMT1 of the BMR is responsible for activated RTEs-mediated IFN response and CCD.

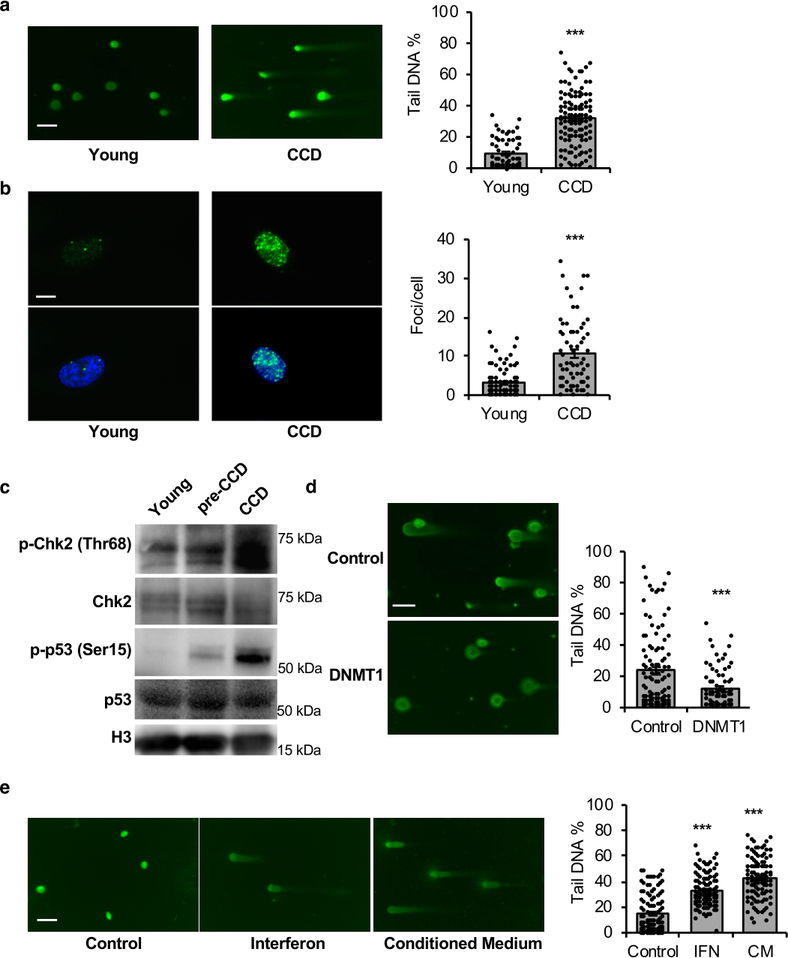

As CCD involves a transient senescence-like state, we tested whether senescence was associated with DNA damage. Cells prior to entering CCD showed elevated γH2AX foci and DNA fragmentation, as measured by comet assay (Extended Data Figures 5a, b). Consistently, typical DNA damage response was observed as determined by increased phosphorylation of Chk2 (Thr68) and p53 (Ser15) before CCD (Extended Data Figure 5c). Notably, DNMT1 rescued cells displayed reduced DNA damage (Extended Data Figure 5d). To determine if the DNA damage is a cause or consequence of IFN response, we treated young, growing cells with either medium enriched with BMR interferon, or conditioned medium from dying BMR cells. Both treatments induced DNA damage to young cells (Extended Data Figure 5e), suggesting that the observed DNA damage is at least partly a consequence of IFN response.

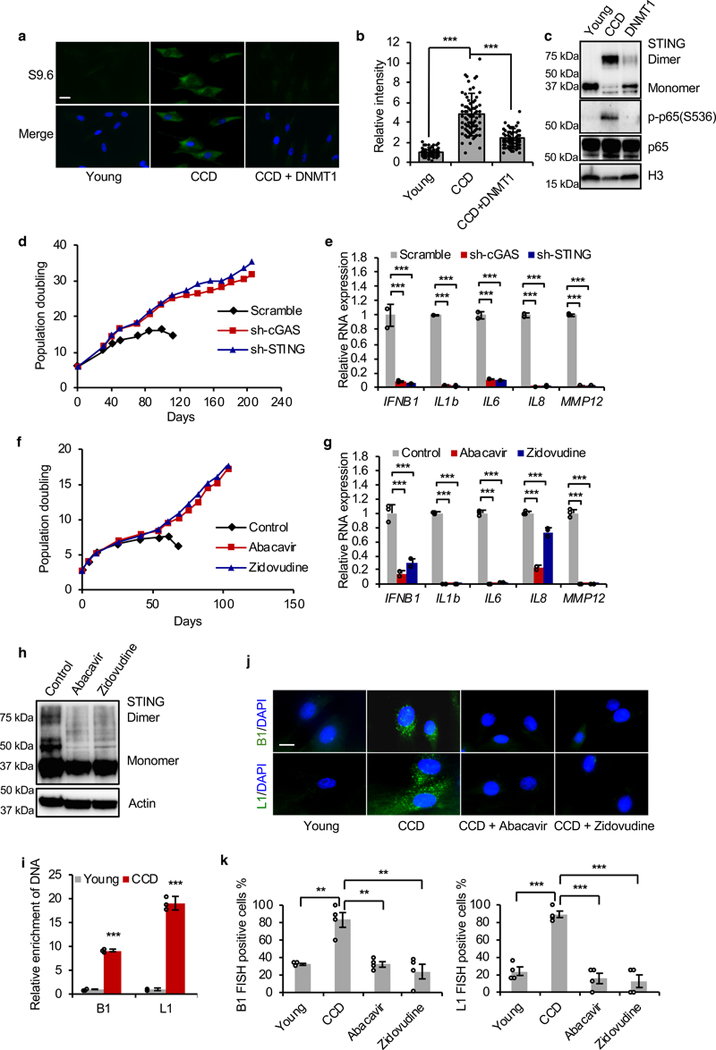

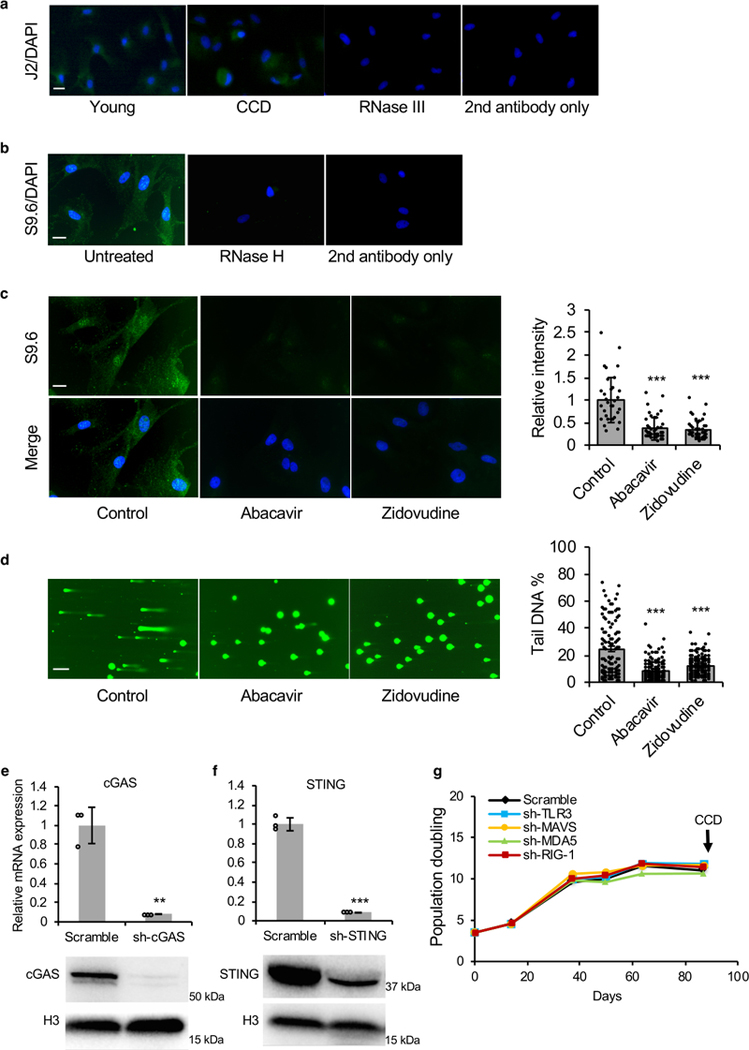

RTEs form Cytoplasmic RNA/DNA Hybrids and induce cGAS-STING

We next investigated the mechanism by which the RTEs induce IFN response. Activated RTEs induce IFN response by triggering accumulation of cytoplasmic RTE DNA copies which activate cytoplasmic DNA sensors16, 17. The RTE-derived cytoplasmic nucleic acids can be of different types including double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), double-stranded (dsRNA), or RNA/DNA hybrids, depending on the types of RTEs that are activated5. As BMR cells contain many activated retrotransposons (SINEs and LINEs) before CCD, we detected the presence of both dsRNA and RNA/DNA hybrids. While no difference was observed for dsRNA (Extended Data Figure 6a), RNA/DNA hybrids were dramatically increased in CCD cells as determined by immunofluorescence (Figures 4a, b). Cells treated with RNase H, which specifically degrades RNA/DNA hybrids, and cells incubated with secondary antibody only lost cytoplasmic staining signals (Extended Data Figure 6b), confirming that the observed signals represent specifically RNA/DNA hybrids. Strikingly, the signal of RNA/DNA hybrids was significantly reduced in DNMT1 rescued cells, suggesting the causal role of weak DNMT1 for RTE-derived cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids (Figures 4a, b).

Figure 4. cGAS-STING pathway is activated in over-proliferating BMR cells by RNA/DNA hybrid and is required to induce IFN response and CCD.

(a) Immunofluorescence images of cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids stained by S9.6 antibody comparing young, CCD, and DNMT1 overexpressing BMR cells. Scale bar, 5 μM. (b) Quantification of cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids. About 100 cells from each group were quantified for intensity. (c) Activation of cGAS-STING-NF-κB pathway in BMR CCD cells. Western blot showing STING dimer and phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (Ser536), which were repressed by overexpression of DNMT1. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (d) Knockdown of cGAS or STING rescued CCD of BMR cells. Experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results. (e) Knockdown of cGAS or STING in BMR cells repressed expression of IFNB1 and SASP genes. N = 3 technical replicates. (f) Treatment of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) rescued CCD. Cells were grown in media containing 4 μM Abacavir or 1 μM Zidovudine, respectively. (g) Treatment of NRTIs repressed expression of IFNB1 and SASP genes. N = 3 technical replicates. (h) Western blot showing reduced STING dimer in BMR cells treated with NRTIs. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (i) cGAS-bound DNA is enriched with B1 and L1 retrotransposons in dying BMR cells. Immunoprecipitation of cGAS from young and dying BMR cells shows an average 9- and 19-fold enrichment for B1 and L1 DNA respectively. Abundance of cGAS-bound DNA was normalized to 5S rDNA. N = 3 technical replicates. (j) Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showing accumulation of B1 and L1 cDNA in cytoplasm before CCD, which is abrogated by NRTIs treatment. cDNA of B1 and L1. Scale bar, 5 μM. (k) Quantification of B1 and L1 cDNA positive cells. Fluorescence foci positive cells from 4 random areas were counted. Data are mean ± SD. ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

RNA/DNA hybrids have been shown to activate cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase)-STING (stimulator of interferon genes) pathway34. Considering that both IFN and SASP were induced in dying BMR cells, we hypothesized that cGAS-STING-NF-κB pathway is activated to trigger CCD. Indeed, homo-dimer of STING, hallmark of STING activation, and phosphorylated NF-κB p65 Ser-536 were observed in CCD cells, both of which were abrogated in DNMT1 rescued cells (Figure 4c). To further confirm cGAS-STING pathway is responsible for CCD induction, we knocked down cGAS or STING with short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs; Extended Data Figures 6e, f); both cGAS and STING knockdowns rescued CCD and inhibited the expression of IFNB1 and SASP genes (Figures 4d, e). As expected, knockdown of dsRNA sensing genes did not rescue CCD (Extended Data Figure 6g).

It was shown previously16, 17 that the treatment of human or mouse cells with nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) prevents accumulation of cytoplasmic RTE DNA. NRTIs were developed as anti-HIV drugs, but also inhibit L1 reverse transcriptase35. We treated BMR cells with two NRTIs, Abacavir and Zidovudine. As expected, both treatments reduced cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids (Extended Data Figure 6c). More importantly, NRTIs treatment rescued CCD (Figure 4f), repressed the expression of IFNB1 and SASP genes (Figure 4g), and reduced DNA damage (Extended Data Figure 6d). Furthermore, NRTIs also inhibited cGAS-STING pathway by abrogating STING dimer (Figure 4h). To determine the specific DNA elements that bind and trigger cGAS, we performed an immunoprecipitation of cGAS. cGAS-bound DNA was purified and enrichment of SINE B1 and L1 was quantified by qPCR. B1 and L1 sequences were enriched by 9-fold and 19-fold respectively in the CCD cells relative to young cells (Figure 4i). Furthermore, we directly detected B1 and L1 cDNA in the cytoplasm of CCD cells with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), using probes against consensus SINE B1 and L1 of BMR. The cytoplasmic B1 and L1 cDNA was abrogated by NRTIs treatment (Figures 4j, k). Collectively, these results suggest that activated RTEs in dying BMR cells are responsible for cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids-induced CCD via cGAS-STING-IFN pathway.

RTE-cGAS-STING Pathway Suppresses Tumor Growth in BMR

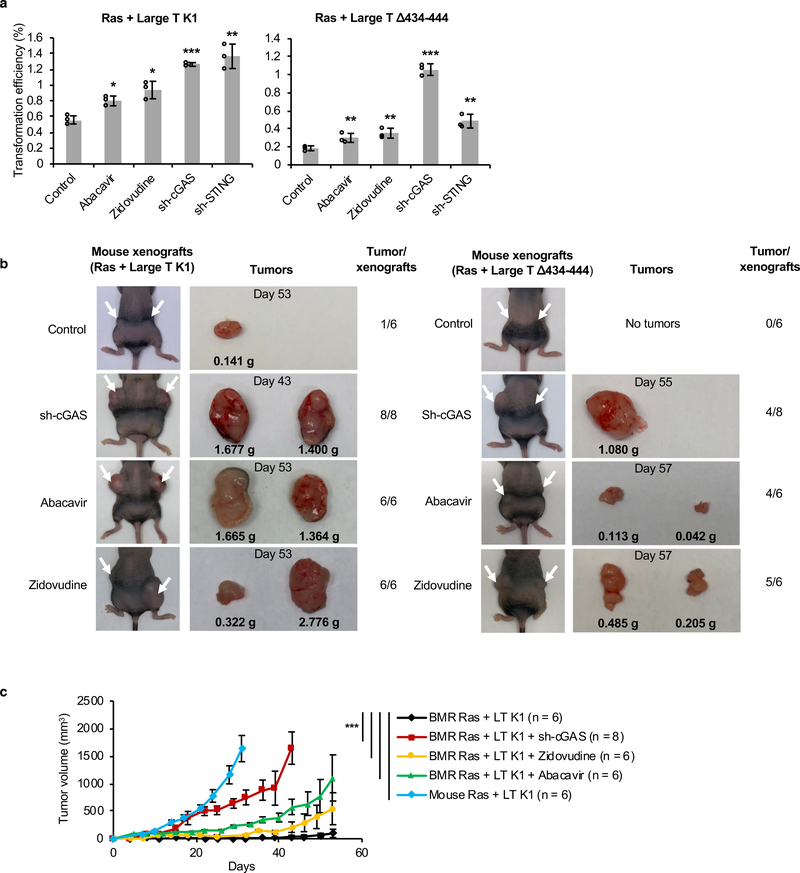

We then tested if the activated RTEs-cGAS-STING pathway in BMR cells is responsible for the cancer resistance of BMRs. SV40 Large T antigen (LT) is an oncoprotein that inactivates two major tumor suppressor pathways, p53 and Rb. LT has two mutant derivatives, LTK1 (K1), which inactivates only p53, and LTΔ434–444 (Δ434), which inactivates only Rb and its family members36. Mouse cells can be malignantly transformed with high efficiency by a combination of H-Ras V12 (Ras) with either K1 or Δ43437. However, BMR cells require inactivation of both p53 and Rb for efficient transformation37. To test the role of RTE-cGAS-STING pathway in BMR resistance to malignant transformation, we transfected BMR fibroblasts with Ras combined with either K1 or Δ434 and cultured them in soft agar with or without the presence of NRTIs Abacavir or Zidovudine. Consistent with the previous observations, the combination of Ras with either K1 or Δ434 yielded only a small number of colonies in soft agar. However, treatment with either Abacavir or Zidovudine, significantly enhanced proliferation for both Ras + K1 and Ras + Δ434 cells in soft agar (Figure 5a). Furthermore, knocking down either cGAS or STING also dramatically increased proliferation (Figure 5a). These results suggest that NRTI treatment and cGAS/STING knockdown make BMR cells susceptible to malignant transformation.

Figure 5. NRTIs treatment or knockdown of cGAS or STING enhances malignant transformation of BMR cells.

(a) Soft agar assays of anchorage-independent growth. BMR cells were transfected with SV40 LT (LT) mutant derivatives K1 or Δ434–444, and H-Ras V12 (Ras), and plated in soft agar. Cells were grown for 4 weeks in soft agar, and colonies were stained and counted. For NRTIs groups, cells were grown in soft agar containing 4 μM Abacavir or 1 μM Zidovudine. The efficiency of transformation was calculated as: no. colonies (no. seeded cells × transfection efficiency). The experiments were repeated 3 times. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test. (b) Mice xenograft experiment with BMR fibroblasts with cGAS knockdown or NRTIs treatment. NIH III immunodeficient nude mice were injected with BMR lung fibroblasts expressing Ras V12 and LT K1 or LT Δ434–444, with either control or shRNA targeting cGAS. For NRTIs groups, mice were fed with 1mg/mL Abacavir or 0.5mg/mL Zidovudine in drinking water. Mouse transformed cells were injected as a positive control. Cells were allowed to grow for 8 weeks or until the tumors reach 20 mm in the longest dimension. Images of injected mice, tumors incised, and numbers of tumors were shown. (c) Growth curve of tumors. The volume of tumor was calculated as D × d × d /2 (mm3), where D and d are the longest and shortest diameter of the tumors in mm. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as determined by unpaired two-sided t-test (a) or two-way ANOVA (c).

To further confirm this finding in vivo, we performed xenograft experiment. We generated BMR cell lines harboring Ras with either K1 or Δ434 and a stable knock down of cGAS with shRNA lentivirus. The cells were injected into immunodeficient nude mice and allowed to grow for 8 weeks. For NRTI treatment, mice were fed with Abacavir or Zidovudine in drinking water. For cells expressing Ras + K1 with control shRNA, only 1 out of 6 injections resulted in a small tumor, while all injections of the cells with cGAS knockdown and that in NRTI treated mice developed into large tumors (Figures 5b, c). With Ras + Δ434, no tumors were formed with control shRNA, and 4 out of 8 injections of cGAS knockdown cells, 4 out of 6 injections with Abacavir treatment, and 5 out of 6 injections with Zidovudine treatment formed tumors (Figure 5b). These results suggest the critical role of RTE-cGAS-STING pathway in BMR cancer resistance.

RTEs Function as Tumor Suppressors in Human and Mouse

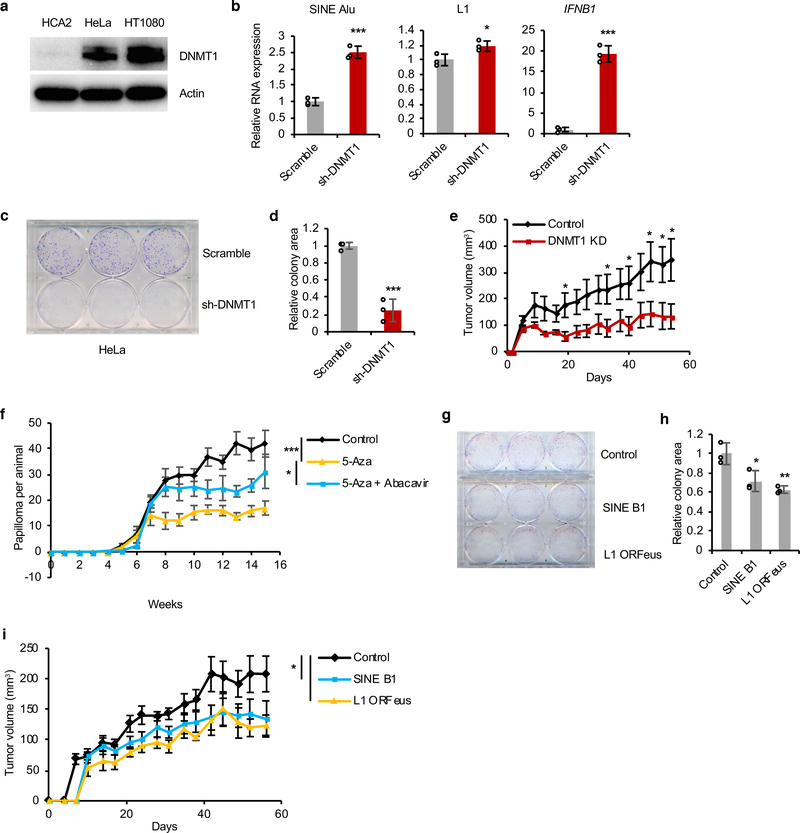

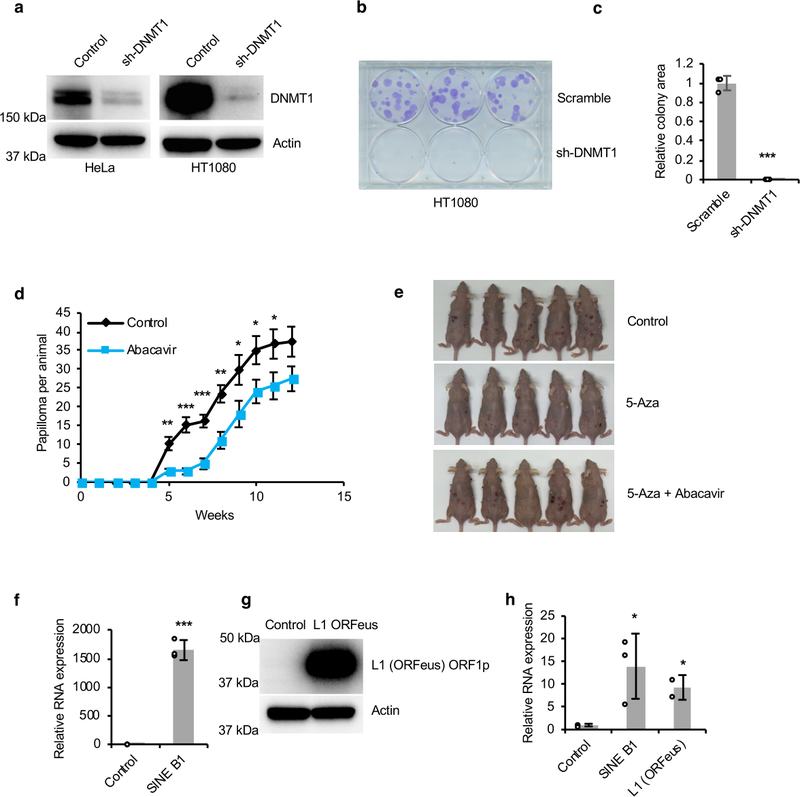

Demethylating agents have been reported to trigger death of human cancer cells via activation of RTEs and nucleic acid sensors24, 38. It is possible, that as a normal tumor suppressor mechanism, DNMT1 activity becomes limiting upon hyperplasia triggering activation of RTEs in pre-malignant cells. Notably, DNMT1 is overexpressed in malignant tumors that escaped this barrier to transformation39. To test if the mechanism revealed from BMR applies broadly to other mammals, we used two common human cell lines, HeLa and HT1080. Compared with primary human skin fibroblasts, both HeLa and HT1080 cell lines had significantly higher DNMT1 protein levels (Figure 6a). Knockdown of DNMT1 (Extended Data Figure 7a) activated expression of SINE Alu (human homologue of rodent SINE B1), L1, and IFNB1 (Figure 6b). The proliferation of both HeLa and HT1080 cells was repressed by DNMT1 knockdown as determined by clonogenic assay (Figures 6c, d and Extended Data Figures 7b, c). Xenograft experiments in nude mice confirmed that the tumor growth of HeLa cells was repressed by DNMT1 knockdown (Figure 6e). We next investigated if, like in the BMR, RTEs serve as tumor suppressors in mice. As many inbred mouse strains carry a nonfunctional MX1 allele, a gene important for CCD in BMR (Figures 1e, f), we used a hairless immunocompetent outbred SKH1 mice strain40. The mice were subjected to DMBA/TPA-induced tumorigenesis. When administered Abacavir in drinking water, the number of DMBA/TPA-induced papilloma was lower than that of control group (Extended Data Figure 7d). This is possibly due to the side-effect of NRTI including anti-angiogenesis and inhibition of telomerase. Meanwhile, the abundant endogenous DNMT1 in mice tissues may have inhibited the activation of RTEs. We therefore injected the mice with demethylating agent 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza), followed by DMBA/TPA treatment. 5-Aza treated mice had dramatically lower numbers of papilloma (Figure 6f). Strikingly, when Abacavir was administered in combination with 5-Aza, the papilloma numbers were increased (Figure 6f and Extended Data Figure 7e). This result suggests that the protective role of demethylation against tumorigenesis depends largely on activation of RTEs, particularly L1.

Figure 6. Transposons can act as tumor suppressors.

(a) Western blot showing higher expression of DNMT1 in cancer cell lines HeLa and HT1080 than primary human skin fibroblasts. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (b) qRT-PCR showing that knockdown of DNMT1 in HeLa cells elevated expression of human retrotransposons SINE Alu, L1, and IFNB1 gene. N = 3 technical replicates. Experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (c-d) Knockdown of DNMT1 repressed proliferation of HeLa cells in vitro. Clonogenic assay was performed with crystal violet staining and colonies areas were quantified. N = 3 technical replicates. Experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (e) Knockdown of DNMT1 inhibited the proliferation of HeLa cells in nude mice xenograft. N = 6 independent xenograft injections. (f) Demethylation reagent 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) repressed DMBA/TPA-induced tumorigenesis, which is restored by NRTI. Experiment was performed using five animals for each group. (g-h) Clonogenic assay showing repressed proliferation of HeLa cells overexpressing SINE B1 and L1. HeLa cells were stably transfected with a SINE B1 or a codon-optimized human L1 (ORFeus) and were then subjected to clonogenic assay with crystal violet. N = 3 technical replicates. Experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (i) Overexpression of B1 and L1 repressed the proliferation of HeLa cells in nude mice xenograft. N = 6 independent xenograft injections. Data represent mean values for all figures. Data are mean ± SD (b, d, and h) or mean ± SEM (e, f, and i). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as determined by unpaired two-sided t-test (b, d, e, and h) or two-way ANOVA (f and i).

We next tested if RTEs directly inhibit cancer cells proliferation. HeLa cells were stably transfected with either SINE B1 sequence or a codon-optimized L1 (ORFeus). Both B1 and L1 overexpression activated IFNB1 (Extended Data Figures 7f-h). Clonogenic assays and xenograft experiments showed that both B1 and L1 overexpression inhibited HeLa cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo (Figures 6g-i). These results suggest that RTEs can exhibit tumor-suppressive effect in human and mouse cells.

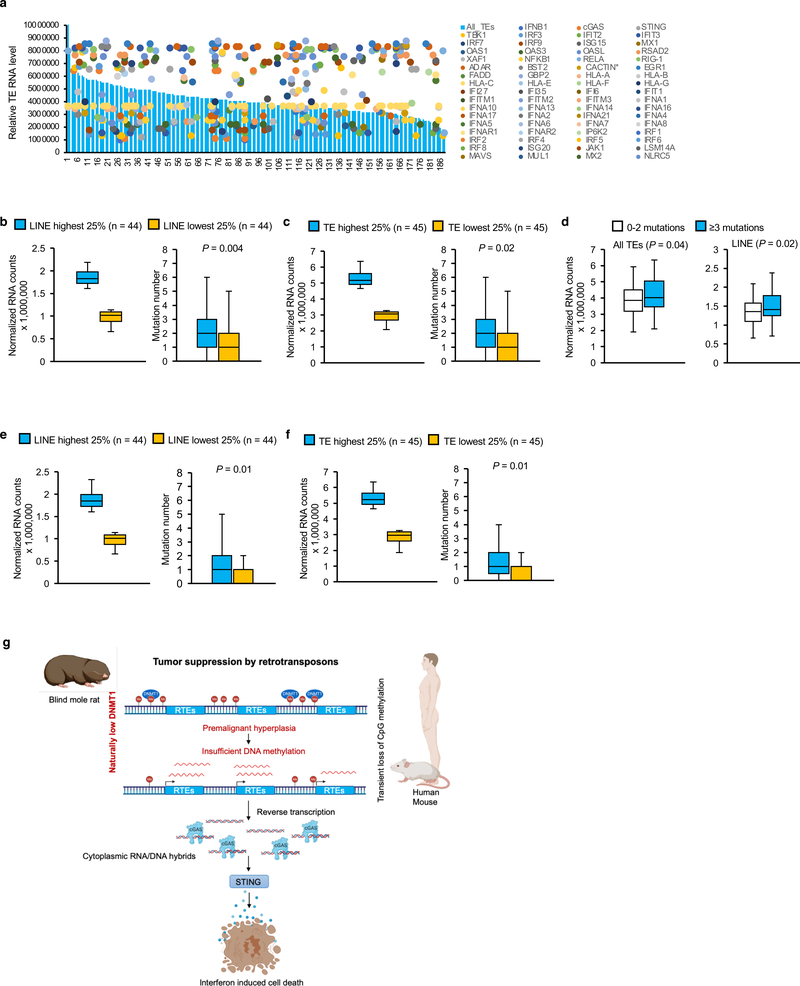

Cancer Cells with High RTEs Carry More IFN Pathway Mutations

A seemingly contradictory observation is that many cancer cells have high expression of RTEs including L1. We hypothesize that in established tumors, the IFN pathway is mutated, which allows for unabated RTE activation. To test this, we analyzed the RNA-seq data in 188 lung cancer cell lines from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database and analyzed the correlation between the expression level of different families of TEs using TEtranscripts 41 and mutations in a total of 73 genes from type I IFN pathway plus cGAS, STING, and NF-κB genes (Figure 7a and Supplementary Data 1). Cell lines in the top 25% of LINEs expression had significantly more mutations in IFN pathway than the bottom 25% (Figure 7b). Similar result was obtained when comparing the top 25% of all RTE expression with the bottom 25% (Figure 7c). Alternatively, when the cell lines were grouped based on mutation numbers, the average expression levels of both LINE and RTEs were significantly higher in the cell lines with 3 or more mutations in IFN pathway (Figure 7d). When we further narrowed down the gene list to only the genes that are directly involved in and enhancing/enhanced by IFN (Supplementary Data 1), the result remains the same (Figure 7e-g). These results confirm that in human cancers high RTE expression is associated with mutations in IFN pathway.

Figure 7. Cancer cells with higher expression of TEs tend to carry more mutations in type I IFN pathway.

(a) Correlation of TE expression levels and mutation numbers in type I IFN pathway in cancer cell lines. TE expressions were extracted from RNA-seq data of 188 lung cancer cell lines from CCLE. Cell lines were sorted by TE expression levels, and mutations of each gene from each cell line were plotted. (b-c) Analysis of correlation between LINE or all TE expression level and mutation numbers in type I IFN pathway genes from Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database. Cell lines with the highest 25% and lowest 25% of LINE (b) or all TE (c) expression were grouped (left lane) and the corresponding mutation numbers were plotted (right lane). (d) Lung cancer cell lines with ≥3 mutations in IFN pathway have higher expression of all TEs and LINEs than cell lines with 0–2 mutations. (e-f) Analysis of correlation between LINE or all TEs expression levels and mutation numbers in genes that are directly involved in IFN pathway and are positively regulating/regulated by IFN. The number of mutations in cell lines with the highest 25% and lowest 25% of LINE (e) or all TE (f) expression were plotted. For boxplots (b-f), Center lines represent median, bounds of box are the 1st quartile and 3rd quartile, and whiskers indicate 1.5 × interquartile above the third quartile or 1.5 × interquartile below the first quartile. P value was determined by unpaired two-sided t-test. (g) Model of BMR cancer resistance and its generalization to human and mice. BMR has naturally low DNMT1. Loss of DNA methylation activates RTEs in hyperplastic cells. Similarly, transient loss of DNA methylation in hyperplastic lesions in human and mice also activates RTEs. Activated RTEs form cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids that trigger cGAS-STING-IFN, which kills premalignant cells.

Discussion

Our study uncovered a novel anticancer mechanism in a tumor-resistant rodent, the BMR. We showed that a naturally low expression of DNMT1 in the BMR fails to maintain DNA methylation on RTEs during rapid cell proliferation. This results in de-repression of RTEs, which form cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids, and trigger IFN response through nucleic acid sensors cGAS-STING pathway. This mechanism eliminates hyperplastic pre-malignant cells and prevents cancer progression.

Interestingly, genome-wide analysis revealed that the TEs constitute 43.9% of BMR genome. This percentage is similar to that of human (45%), and higher than other rodents including mouse (37.5%) and rat (40%)8, 42, 43. This higher percentage of TEs may enhance the anticancer activity of the RTEs in the BMR. The possible reason that BMR adopted a weak DNMT1 as anti-cancer strategy is that it carries a mutant p53 gene. BMR inhabits subterranean burrows, enduring extreme hypoxia. The p53 of BMR carries an Arg174Lys mutation mimicking human tumor mutation44. This mutation abrogated its pro-apoptotic activity as an adaptation to hypoxia-induced cell death. As p53 restrains transposons, this mutant p53 in BMR may have unleashed the transposition. This can also partly explain the reason of TEs expansion in BMR genome. We hypothesize that the low level of DNMT1 have co-evolved with the mutant p53 and expanded TEs to trigger IFN pathway in over-proliferating cells, acting as a compensatory strategy.

Persistent activation of RTEs can cause mutations and inflammation, and therefore needs to be tightly regulated. In mammals, multiple mechanisms have evolved to repress transposons, including DNA methylation, heterochromatin, small RNAs, and KRAB zinc-finger proteins5, 45. DNMT1 is responsible for maintenance of DNA methylation 14, 15. After DNA replication, DNMT1 scans the genome to methylate hemi-methylated regions 46. Most cells in somatic tissues are in G0 phase and only occasionally proliferate in response to extrinsic stimuli including wound healing. The naturally weak DNMT1 in BMR provides suffcient function for the normal cells, but becomes limiting upon fast proliferation and hyperplasia. In this way, only hyperplastic cells lose methylation and activate RTEs triggering a suicidal IFN response. In vivo this response may be limited to the vicinity of the pre-neoplastic lesion as IFN acts in a paracrine manner. Additionally, IFN related genes are repressed in normal BMR tissues as revealed by our transcriptomic analysis, which can further prevent unintended activation of IFN in the BMR.

It has been shown that DNA demethylating agents activate ERVs, another type of RTEs, in human cancer cells, which form dsRNA24, 38. The dsRNA sensing pathway is an inducer of IFN, as demonstrated in Alu-derived dsRNA47, and the loss of ADAR, a dsRNA-editing enzyme in cancer cells48. However, LINE1 activation in both human and mouse triggers IFN response via cytoplasmic DNA-cGAS-STING pathway16, 17 suggesting that activation of cGAS-STING pathway by cytoplasmic DNA is a common feature of non-LTR elements in both BMR, mouse and human. In our study, we did not observe increased dsRNA during CCD, but only RNA/DNA hybrids. Consistently, knocking down dsRNA sensors TLR3, MAVs, MDA-5, and RIG-1 failed to rescue CCD. This is possibly due to the expansion of SINEs in BMR genome42 combined with the dramatic derepression of L1. During CCD, both LTR RTEs (ERVs) and non-LTR RTEs (LINEs and SINEs) are activated, but up-regulated LINEs and SINEs have higher basal levels, are more abundant and thus may provide greater biological influence. This does not exclude the possibility of additional roles played by other types of TEs in BMR cancer resistance.

Strikingly, although enhanced in BMR, we found this mechanism is also applicable to humans and mice. DNMT1 tends to be overexpressed in malignant tumors that escaped the barrier to transformation39. This was also confirmed in our experiments with human cancer cells. Knocking down of DNMT1 in human cancer cells triggered similar response to that happened in BMR cells during CCD, including elevated SINEs and LINE1, induction of IFN, and reduced cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Similarly, mice treated with DNMT1 inhibitor 5-Aza dramatically repressed papillomas induced by DMBA/TPA. This repression is at least partly due to activated RTEs confirmed by the restoration of papilloma by NRTI treatment. Notably, treating the mice with NRTI alone did not increase papillomas; instead, NRTI treatment reduced papillomas. This is possibly because NRTI has some anti-cancer effects through inhibiting telomerase (another type of reverse transcriptase in cells)49 and anti-angiogenesis50, 51, 52. These results suggest that RTEs acting as tumor suppressors is not limited in BMR, but is applicable to other mammals.

It has been argued that RTEs are highly expressed in some cancer cells, and thus RTEs drive carcinogenesis 53. We showed that in cancer cell lines with higher expression of RTEs, more genes of IFN pathway were mutated. Therefore, the selective pressure against RTE activation had been lost in these cancer cells. Interestingly, the p53 tumor suppressor which is lost or mutated in over 50% of human cancers represses RTEs54. Thus, RTE-mediated cell death can provide a back-up barrier to stop proliferation for cells that lost p53.

RTEs are selfish elements highly abundant in mammalian genomes where they may acquire functional roles through “domestication”55. Here we propose that transposable elements were coopted to serve as tumor suppressors by gauging cell over-proliferation and triggering death of hyperplastic cells via activation of cytoplasmic nucleic acid sensors. This finding assigns a new beneficial function to RTEs and may explain why mammalian genomes have not eliminated these elements. Interestingly, other anticancer mechanisms such as apoptosis56, 57 and cellular senescence58, 59 display antagonistic pleiotropy, where they contribute to aging pathologies in late life. Similarly, persistent RTE activation contributes to aging by promoting sterile inflammation16, 17. However, as derepressed RTEs in aging is not specific to tumors, age-related activation of RTEs does little to reduce cancer risk in the elderly. Additionally, other pro-tumorigenic changes that occur with age such as metabolic changes and accumulation of mutations may overpower the tumor suppressive effect of RTEs.

Our study points to RTE activation as a useful target for cancer treatment. Additionally, NRTIs are broadly used as antivirals for HIV treatment or prevention. While the benefits of NRTIs clearly outweigh the risks in HIV patients, our study suggest that potential cancer risks associated with NRTIs warrant further investigation when NTRIs are chronically administered to healthy people. In summary, our study demonstrates that studying naturally cancer-resistant animals provides a strategy for identification of novel mechanisms broadly applicable to humans.

Methods

Data Availability

Most data are included in the figures. The exact p values, if applicable, are included in the source data. RNA-seq and MeDIP data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession no. GSE181413. Normalized methylation values of Illumina microarray (HorvathMammalMethylChip40) are available at GEO under accession no. GSE181732. RNA-seq data of 188 lung cancer cell lines were obtained from Broad Institute (https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/). Cell line mutation information was obtained from http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Harmonizome/.

Animals

Compliance with ethical regulations and all animal experiments were approved by University Committee on Animal Resources of University of Rochester. The blind mole rats (BMRs, Spalax galili) were wild caught from Upper Eastern Galilee Mountains, Israel, and were housed individually. C57BL/6 mice of both sexes were purchased from Taconic Biosciences, Inc. NIH III Nude mice (Crl:NIH-Lystbg-JFoxn1nuBtkxid) and SKH1 hairless mice (Crl:SKH1-Hrhr) were purchased from Charles river Laboratories Inc.

Cell culture

Primary fibroblasts were isolated from lung and skin of BMRs and mice of at least three individuals. All the BMR fibroblast cell lines have similar growth characteristics and the occurrence of concerted cell death (CCD). Human primary skin fibroblasts HCA2 were a gift from O. Pereira-Smith. Fibroblasts were maintained at 37 °C incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 3% O2 on treated polystyrene culture dishes (Corning) in EMEM media (ATCC) with 15% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS). HeLa and HT1080 cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. For all cell cultures, 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco) were added.

Plasmids and lentivirus

Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) of human DNMT1, SV40 Large T (LT), LTK1 (K1), LTΔ434–444 (Δ434), and codon-optimized L1(ORFeus) were PCR amplified from corresponding plasmids (Addgene) and subcloned into a piggyBac (pPB) expression vector under the CAG promoter. For overexpression, all pPB plasmids were co-transfected with a piggyBac transposase (pBase) plasmid, followed by puromycin selection. pWZL-hygro-H-Ras V12 (Addgene 18749) was linearized by NotI before transfection to enhance the genomic integration, followed by hygromycin selection. For B1 overexpression, consensus sequence of mouse SINE B1 was ligated into a piggyBac shRNA vector. SINE B1 RNAs will be expressed by the vector’s H1 promoter without forming shRNA.

For shRNA-mediated knockdown, shRNAs against BMR MX1, cGAS, and STING were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology (IDT): MX1: TCCACGGAAAGTCAGAAAGAACAGCCTGA; cGAS: GACTCTAGACGTGTAAGGACAACTTGGAA; STING: TGCTGTCTGGTTGAAGAACTATGCCACGT. The sequences were ligated into an iLenti-siRNA-GFP lentiviral Vector (abm). Lentiviral vectors were co-transfected with packaging plasmids psPAX2 (Addgene 12260) and VSV-G (Addgene 14888) to HEK293T cells. Viral supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. To infect target cells, viral supernatant was supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene, and applied to cells. The infected cells were selected with puromycin.

Transfection

BMR, mouse of human fibroblasts were seeded at 5 ×105 cells per 10mm plate and allowed growing for 5 days before transfection. For transfection, 106 cells were harvested and transfected with 5 μg plasmid DNA using Amaxa Nucleofector II on program T-020 and NHDF solution (Amaxa). Media was changed 24 h after transfection to remove dead cells.

Conditioned media and interferon (IFN) treatment

For conditioned media, BMR lung or skin fibroblasts undergoing CCD were maintained in complete EMEM media for 5 days. Media was the collected and centrifuged to remove cell debris. For BMR IFN enriched media, human skin fibroblasts HCA2 cells were transfected with a pPB expression vector ligated with BMR IFN cDNA, and selected with puromycin for 1 week to obtain integrated colonies. Stably transfected cells were pooled and allow growing for 5 days. Media was collected and centrifuged. Conditioned media or IFN enriched media was applied to young, growing BMR cells mixed with 1 volume of fresh complete EMEM media to provide sufficient nutrients. After 2 weeks of incubation, cells were collected for comet assay.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from cells and tissues were extracted with a Quick-RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo), with a DNase I on column digestion to remove genomic DNA contamination. Reverse transcription was performed using an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR was performed using a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Results were normalized by β-actin.

To identify the active L1 sequence in BMR, a protein sequence of L1 orf1 from mouse L1MdaI family was used as the query to perform tblastn search against BMR genome (GCA_000622305.1). As most of the hits harbor ORF-disrupting mutations, a homemade Perl script was used to screen hits without disrupting mutations. Complete orf1 proteins from these hits were predicted by GeneWise 60 using corresponding genomic sequence with 2000bp flanking sequences and mouse L1MdaI protein sequence. Transcriptome was used to determine expressed and potentially functional orf1 proteins in BMR cells. More than 20000 loci with >1000bp sequence covered by transcriptomic reads were selected to predict orf1 protein sequences by GeneWise using corresponding genomic sequence with 6000bp flanking sequences and previously predicted BMR orf1 protein sequence. As a result, 44 predicted orf1 protein sequences with at least 200 amino acids were obtained, two of which have highest conservation with mouse L1MdaI.

Primers for SINE B1 and B2 were designed based on rodent consensus sequences obtained from SIENBase. LINE1 primers were designed based on the sequence of the 2 BMR L1 closest to mouse L1Mda1 ORF1. Primers for all other genes were designed according to annotated BMR corresponding genes crossing exon-intron junctions. The following primers were used: IFNB1: ACCTTGCTCCTTCTGTGCT, AACTGCTGTTGGTGCTTGA; DNMT1: GAAACCGCCACAACCACTG, ACTCACGCACGCTCACCA; SINE B1: CGCCTTTAATCCCAGCAC, GCTGTCCTGGAACTCACT; SINE B2: GAGATGGCTCAGTGGGTAA, GCAGAGGTCAGAAGAGGG; LINE-1: TCCTCTAGAGACAATGCAGGACA, TCATTCAGAAGTTTATCC; IL1b: TGATGCACCCCTTCGACTTC, CAAGGCCACAGGTGTTTTGT; IL6: GAACCCTCCATCCTCTTGCC, GGCCTCGTCATTGTTCAAGC; IL8: GAACTTCGATGCCAGTGCAAG, CAAAACCCTCTGCACCCACTT; MMP12: AGTGCCCGATGTTCAGCATT, AATGTCAGCCTCGCCTTCAT; P21 (CDKN1A): TGGTGTCTCACTCCCCTGAG, CCTCTTAGAGAAGACCAGCCG; P16 (CDKN2A): CATGGAGCGGACCCCAACT, TCCTCACCTGAGGGAGCTTT; CGAS (MB21D1): GTCAGACGACTGGAATCCCC, GCCAGGTCTTTGAACTCCGA; STING (TMEM173): AGCTTGGTGATCCTTTCGGG, GGTACCTGGATTGGACGTGG; GAPDH: TGGCCTTCCGTGTTCCTACC, ACCAGAGACAAGCCCAGCTC; 5s rDNA: CTCGTCTGATCTCGGAAGCTAAG, GCGGTCTCCCATCCAAGTAC.

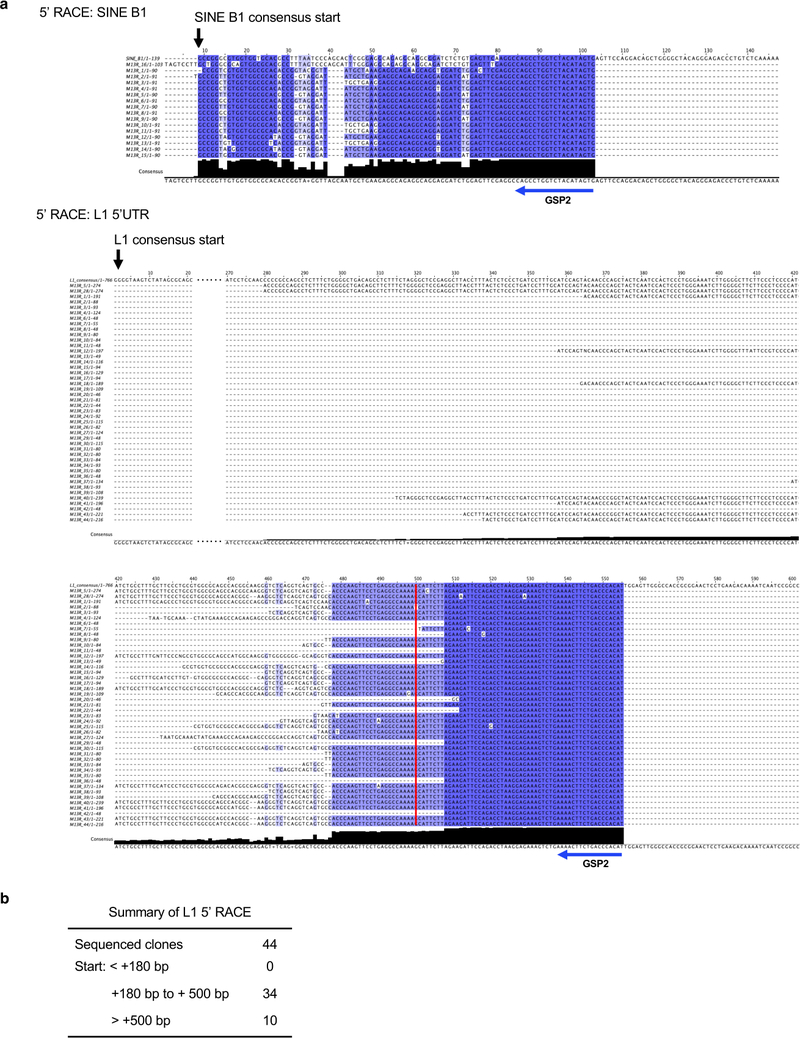

5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)

Total RNA was collected from BMR fibroblasts entering CCD. For each reaction, 1 μg total RNA was subjected to the 5’RACE system (Thermo Fisher 18374–058). Two antisense gene-specific primers (GSPs) for B1 and L1 were used. B1-GSP1: TGTAGCCCTGGCTGTCCT; B1-GSP2: CACTATGTAGACCAGGCTGGCC; L1-GSP1: TCATTCAGAAGTTTATCC; L1-GSP2: ATGTGGGTCAGAAGTTTTCAGACTTTCTCCTTA. Amplification products were ligated into pCR2.1 vector and transformed to One Shot TOP10 chemically competent Escherichia coli (Thermo Fisher, C404010). Totally 60 clones of both B1 and L1 were sequenced using M13R primer by Genewiz. Multiple alignment with consensus B1 and L1 5’UTR sequences was performed using Clustal Omega and visualized using Jalview. To predict the consensus start site of L1 5’UTR, The genomic regions harboring L1 5’ UTR were determined by blastn program using the sequences from 5’ RACE assays. Genomic sequences 1000bp upstream of the top10 blastn hits were extracted and aligned with ClustalW. A highly conserved region (~600bp) and a short adenine nucleotide rich region at the 5’ end of this conserved region was observed. This adenine nucleotide rich region hints that it may contain target site duplication (TSD) sequences. To identify the paired TSD in each L1 copy, 30bp sequence covering the A polymer were used to search against the 2000bp genomic sequences 6000bp downstream of adenine nucleotide rich region using blastn program. Paired TSD sequences were successfully identified in 6 copies with no more than 2 mis-matches and others failed due to the incomplete genomic sequences. Among these 6 paired TSD sequences, all upstream TSD are followed by G nucleotide and all downstream TSD are preceded by polyA-like sequences, suggesting the histories of L1 retrotransposition. Therefore, we used this highly conserved region following the TSD to infer the 5’ UTR consensus sequence.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: DNMT1 (Abcam ab13537; 1:1000), cGAS (Millipore ABF124; 1:1000 for western blot), STING (Thermo Fisher Scientific PA5–70420; 1:1000 for western blot), MX1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific PA5–22149; 1:1000 for western blot), p65 (Cell Signaling Technology 8242; 1:1000 for western blot), p-p65 S536 (Cell Signaling Technology 3033; 1:1000 for western blot), Chk2 (Cell Signaling Technology 2662; 1:1000 for western blot), p-Chk2 T68 (Cell Signaling Technology 2661; 1:1000 for western blot), p53 (Cell Signaling Technology 2524: 1:500 for western blot), p-p53 S15 (Cell Signaling Technology 12571: 1:500 for western blot), S9.6 (Kerafast ENH001: 1:500 for immunofluorescence), J2 (Kerafast ES2001: 1:60 for immunofluorescence), LINE-1 ORF1p (Millipore MABC1152; 1:1000 for western blot), γH2AX (Millipore 05–636-I; 1:1000 for western blot).

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described 61 with slight modifications. Cells were harvested and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and then mixed with 1 volume of 2× Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad). Extracts were boiled and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. For STING dimers, cells were harvested and washed with PBS for 3 times. Cell pellets were then incubated with 2mM disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) for 30 min at room temperature before protein extraction. Protein samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), and incubated indicated primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Abcam) secondary antibodies were used. Proteins were visualized using an ECL kit (Bio-Rad). Quantification of bands was performed using ImageJ.

Clonogenic assay

Clonogenic assay was performed as previously published protocol 62 with slight modifications. BMR cells were transfected with pPB-DNMT1 and pBase vectors selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin and allowed to grow for 3 weeks until colonies formed. Colonies were fixed with 10% Formalin for 5 min and then stained with a staining solution containing 0.5% crystal violet and 20% methanol for 5 min. For cancer cells, 500 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates, allow the cells to grow for 7 days before staining with crystal violet.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining

SA-β-gal staining was performed according to Campisi lab’s protocol 63. BMR fibroblasts at low and high population doublings (PDs) were seeded at ~40% confluence one day before staining to avoid false-positive staining due to over confluency. Cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS for twice, cells were stained with a staining solution containing 20mg/mL X-gal in dimethylformamide, 0.2M citric acid/Na phosphate buffer (pH6.0), 100 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 100 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 M NaCl2, and 1 M MgCl2. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h without CO2. For quantification, images were captured for 3 different areas of each sample and counted at least 100 cells for each area.

Immunofluorescence and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Cells were seeded in wells of chamber slides at the density of 3 × 104/well. One day later cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 37 °C for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. For cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) staining, cells were further incubated with 100% methanol at −20 °C overnight. Cells were then blocked with 5% BSA and 10% FBS in PBS with or without RNase H or RNase III at 37 °C for 4 h and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking reagent overnight at 4 °C. For γH2AX, cells in chamber slides were directly blocked after permeabilization, and primary antibody was incubated in blocking reagent. Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverted fluorescence microscope. All microscope exposures were set to be below saturation, and settings were kept constant for all images crossing samples taken in one experiment. Quantification of immunofluorescence intensity was performed using ImageJ.

For FISH, cells in chamber slides were fixed with 4% PFA at 37 °C for 10 min, and permeabilized with cold methanol for 10 min. Cells were then rehydrated with 70% ethanol for 10min. After removing ethanol, cells were treated with 1 mg/mL RNase A at room temperature for 30 min before 1M Tris (pH8.0) was added. After 5 min of Tris treatment, 2ng/μL Alexa-488 conjugated probes in hybridization buffer (1mg/mL yeast tRNA, 0.005% BSA, 10% dextran sulfate, 25% dionized formamide, and 2X SSC) were added. Chamber slides were subjected to heat shock at 78°C for 2 min and allowed to anneal by incubating at 37°C for 1h. Slides were washed once with 4x SSC for 5min, followed by 3 washes with 2x SSC for 5min. Slides were sealed with mounting media with DAPI. For BMR B1 and L1 DNA FISH, the following probes were used: B1 probe: TGCACGCCTTTAATCCCAGCACTC-Alexa488; L1 probe: TACAAGAAGCCTACAGAACTCCAA-Alexa488;

Immunoprecipitation of cGAS

Cells were seeded in plates and allowed to grow to 80% confluence. Cells were washed with PBS and crosslinked by 2500 J/m2 UV radiation using a Stratolinker UV system. Cells were then lysed by cytoplasmic lysis buffer (50mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 1mM DTT, 2mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 2.5% Digitonin), supplemented with salmon sperm DNA and incubated at 4°C for 5 min with shaking. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30min at 4 °C to remove nuclei, and precleared with 20μL of Agarose A beads with salmon sperm DNA. cGAS was pulled down by incubating with 5 μg cGAS antibody ABF124 (Millipore) overnight, followed by the addition of 30 μL of Agarose A beads with salmon sperm DNA and 2h incubation with rotating. Beads were washed 5 times with lysis buffer before DNA was isolated using a Zymo Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit. One ng of purified DNA was used as qPCR template. For B1 and L1 enrichment detection, qPCR was normalized to 5s rDNA to control nuclear DNA contamination during cell fractionation; additionally, qPCR using primers against GAPDH was performed to ensure no significant contamination from nuclear genomic DNA.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Total RNA from early passage and late passage BMR fibroblasts was extracted using a Quick-RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo), with a DNase I on column digestion to remove genomic DNA contamination. For tissues, 5 wild-caught mice and 5 BMRs were perfused with PBS and tissues were collected for total RNA extraction. The RNA samples were processed with the Illumina TruSeq stranded total RNA RiboZero Gold kit and then subjected to Illumina HiSeq 4000 paired-end 150bp sequencing at New York University Genome Technology Center. Over 50 million reads per sample were obtained. The RNA-seq experiment was performed in three biological replicates for cells and five biological replicates for tissues.

RNA-seq reads were firstly trimmed by Trim_Galore, which trimmed both low-quality base calls and adapter sequences. After the trimming, only reads longer than 50bp were used for alignment. STAR 64 was used for the alignment of paired-end reads onto the BMR genome (genome sequence and GFF annotation of genes were downloaded from Ensemble, release 91). Only alignment with less than 4% mismatch (--outFilterMismatchNoverLmax 0.04) were considered. Considering potential multiple instances of transposable elements, at most 100 multiple alignments were allowed for a red (--outFilterMultimapNmax 100). Genome wide annotation of transposable elements was generated by RepeatMasker(v4.07) 65 with RepBase repeat libraries (20170127) 66. With the sequence alignment, it was challenging to accurately evaluate the expression level of each instance of a transposable element. To overcome the challenge, TEtranscripts 41 was used to measure abundance at the resolution of the element level, combining transcripts of all instances of the same transposable element. Especially for B1 transposable elements, we found the changes of expression level, between young and CCD cells, were associated with CpG counts, so we divided instances of a transposable element into subgroups according to CpG counts in each instance. With the estimated read counts of genes and transposable elements from TEtranscripts, DESeq2 67 was used for differential analysis. During differential analysis, simple repeats, low complexity and rRNA transposable elements were ignored, and transposable elements with FDR < 0.01 and “fold change” > 1.5 were considered differentially expressed between young and CCD cells. Genes with “fold change” > 10 were considered the most up-regulated genes and were used for gene oncology (GO) term and pathway enrichment analysis. For tissues comparing BMR and mouse, high confident one-to-one orthologs (15,137 protein coding genes) between BMR and mouse were obtained from Ensembl BioMart (release 101) 68. All the genes in BMR tagged as high mouse orthology confidence by BioMart were retained for the following analysis (Minimum % of identity > 80%). If a gene in BMR can be aligned to multiple genes in the mouse genome, the gene with the highest sequence identity was kept for the following analysis. DESeq2 67 was used for differential expression analysis of orthologous genes between mouse and BMR. The main assumption in the library size factor calculation of DESeq2 is that the majority of genes remain unchanged. To model the dispersion based on expression level (mean counts of replicates), the dispersion for each gene is estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. Considering the orthologs may have different gene lengths between species, gene lengths were considered for read counts normalization between species by DESeq2. For gene expression pattern of Dnmt1 gene among tissues, Z-scores were calculated for each tissue based on normalized gene expression level of Dnmt1.

DNA methylation profiling array and Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq)

Genomic DNA samples from young and dying BMR fibroblasts as well as mouse fibroblasts of low or high PD were extracted using a Zymo Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit. For mammalian methylation array, DNA samples were sequenced using the custom Illumina chip “HorvathMammalMethylChip40”, which profiles about 37K CpGs that are highly conserved across mammals.

For MeDIP, genomic DNA was randomly sheared by sonication using the Covaris S2 (Covaris,Woburn, MA) to a median fragment size of 200bp. Using the NEBNext UltraII DNA Library Prep kit for Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, MA), fragments were subjected to end repair with subsequent 3’ adenylation to create 3’dA overhang suitable for adaptor ligation. Adapter-ligated DNA was purified without size selection using Ampure XP Beads. Methylated DNA was immunoprecipitated with the Zymo Methylated-DNA IP kit using a 1:10 ratio of DNA to antibody. Library enrichment was performed using 7 cycles of PCR. The resulting libraries were assessed for quantity and size. The amplified libraries were hybridized to the Illumina pair end flow cell and amplified using the cBot (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Pair end reads of 125nt were generated for each sample using the HiSeq 2500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at University of Rochester Genomics Research Center. The MeDIP-seq experiment was performed in two biological replicates.

MeDIP-seq reads were first trimmed by Trimmomatic 69 to remove adapter and other illumina-specific sequences, together with low quality bases, from the reads. The remaining high quality reads, with minimal length 15bp, were mapped to the BMR genome by STAR 64. The entire genome was tiled into 100bp windows, and then the aggregated methylation level for each sample in each window was measured. As the chromosome information of BMR genome is not available, only scaffolds with lengths > 10Kb were used. Differential methylation analysis was analyzed by edgeR, and genomic loci (i.e., 100bp windows) with FDR < 0.1 were considered differentially methylated regions. Then, adjacent differentially methylated windows were merged. Finally, the differentially methylated loci were functionally annotated according to their genomic loci (i.e., overlap with genes or transposable elements).

Comet assay

DNA damage was detected by using a commercial comet assay kit (Trevigen) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Basically, cells were embedded in agarose, fixed, and subjected to electrophoresis in a neutral buffer solution. Cells were stained with SYBR Gold and analyzed with microscopy. Images were acquired, and the percentage of tail DNA was quantified from about 100 cells per sample using CaspLab software.

DNA methylation and DNMT activities assay

Genomic DNA from BMR and mouse tissues or fibroblasts of different PDs was purified using a Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo). One hundred nanograms of purified genomic DNA were subjected to global DNA methylation measurement using an anti-5-methylcytosine (5-mC) antibody-based MethylFlash Methylated DNA Quantification Kit (EpiGentek). For DNMT activities, nuclear proteins from human, mouse, and BMR fibroblasts were extracted using an EpiQuik Nuclear Extraction Kit (EpiGentek). One microgram of nuclear protein of each sample was subjected to DNMT activities measurement using an EpiQuik DNMT Activity/Inhibition Assay Ultra Kit (EpiGentek).

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

NRTIs (zidovudine (also known as azidothymidine, AZT) and abacavir (ABC)) used in this study were USP grade and obtained from Sigma.

Anchorage-independent soft agar growth assay

One million BMR and mouse exponentially growing fibroblasts were transfected by Amaxa with plasmids of the following combinations: 5 μg linearized pWZL-hygro-H-Ras V12, 5 μg pPB-LT (K1 or Δ434), and 5 μg pBase vectors. After transfection, media was changed and cells were selected by 2 μg/mL puromycin and 15μg/mL hygromycin for 1 week to obtain integrated colonies. The colonies were pooled and infected with Lentivirus expressing sh-cGAS, sh-STING, or sh-Scramble. For soft agar, 1% autoclaved Difco Agar Novel (BD Biosciences) was mixed with equal volume of 2× MEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 30% FBS and 2% penicillin–streptomycin. A 3 mL of mixture was poured into a 6 cm plate and allowed to solidify. Cells were harvested and counted. Thirty thousand cells were mixed with 1.5 mL 2× complete MEM medium and then mixed with 1.5 mL 0.8% autoclaved agar liquid, making a final 0.4% agar/1× media solution, and poured on top of the solidified 0.5% medium agar and allowed to solidify at room temperature. Cells were grown for 4 weeks. To visualize colonies, plates were fixed by 70% cold ethanol for 1 h, washed with PBS for three times, followed by adding 2 mL 5μg/mL ethidium bromide staining solution. After staining for 2 h, photos were taken using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Imaging System under UV light. The experiments were repeated for 3 times.

Tumor xenograft assay

Xenograft assay was performed as previously described 70. Briefly, two months old female NIH III Nude mice (Crl:NIH-Lystbg-JFoxn1nuBtkxid) were purchased from Charles river Laboratories Inc. For each injection, 2 × 106 cells were collected and re-suspended in 100 μL of ice cold 50% Matrigel (BD Bioscience) in PBS. The mixed solution was injected subcutaneously into the flank in front of the hind legs with a 22-gauge needle. Cells were allowed to grow for 6 weeks or when the sizes reach 20 mm in the longest dimension before mice were sacrificed and tumors were excised and analyzed. The size and weight of tumors were recorded. If no signs of tumor growth were observed for 6 weeks, the mice were euthanized and dissected to verify the absence of tumors.

7,12-Dimethylbenz(a)anthracene/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (DMBA/TPA) treatment

Three BMRs and three C57BL/6 mice were topically treated with DMBA and TPA. A single dose of DMBA (7.8 mM dissolved in acetone) was topically treated to BMR and mice on dorsal trunk. Three days after, 0.4 mM of TPA was treated for 3 times per week. Two weeks after treatment, skin biopsy was obtained from treated area for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR. For tumorigenesis, hairless SKH1 mice were treated with the same initial dose of DMBA followed by 3 TPA treatments per week for 12–15 weeks. For demethylating agent treatment, mice were i.p. injected with or without 0.5mg/kg 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) 3 times per week. For NRTI treatment, mice were fed with 1mg/mL Abacavir in drinking water.

CCLE analysis

RNA-seq data of 188 lung cancer cell lines were obtained from Broad Institute (https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/). Low-quality base calls and adapter sequences were trimmed by Trim_Galore. After trimming, reads longer than 50bp were mapped to the GRCh37 build of the human genome reference by STAR 64 (GFF annotation of genes was from Gencode, release 34 and GFF annotation of repeat elements was from http://labshare.cshl.edu/shares/mhammelllab/www-data/TEtranscripts/TE_GTF/GRCh37_GENCODE_rmsk_TE.gtf.gz). Alignments with less than 4% mismatch and at most 100 multiple alignments for a read were reported. Then TEtranscripts 41 was used to measure transcriptome abundance of transposable elements by combining transcripts of all instances of the same transposable element. Normalized read counts and expression level were generated by DESeq2 67. Cell lines associated with mutations on genes of type I IFN pathway (GOTERM_BP_ALL GO:0060337) were obtained from http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Harmonizome/. Mutations from both database of CCLE, COSMIC Cell Line Gene Mutation Profiles, and the report of Klijn et al 71 were collected. For outliers, firstly, the data was sorted by “# mutations”, the z-scores were calculated for each data point based on the average and standard deviation for the whole “# mutations” data set, and cell lines with z-score > ±3 for “# mutations” were excluded as outliers. Next, z-scores for “TE expression level” were calculated for each group of cell lines with the same number of mutations, and cancer lines with z-score > ±2 for “TE expression level” were excluded as outliers. The cell lines with highest 25% and with lowest 25% of all TE expression were grouped and compared. Alternatively, data was sorted by the sum of LINEs expression and analyzed in the same method. Anandakrsihnan et al 72 reported that three hits/mutations are required to develop lung adenocarcinoma, thus cell lines with mutation number ≥ 3 were separated with those with mutations < 2 for comparison. Boxplots were generated. For boxplots, the central rectangle ranges from the first quartile to the third quartile. The line in the rectangle shows exclusive median. The whiskers indicate 1.5 × interquartile above the third quartile or 1.5 × interquartile below the first quartile. Outliers were not displayed in the boxplots but were included in P value calculation. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Extended Data

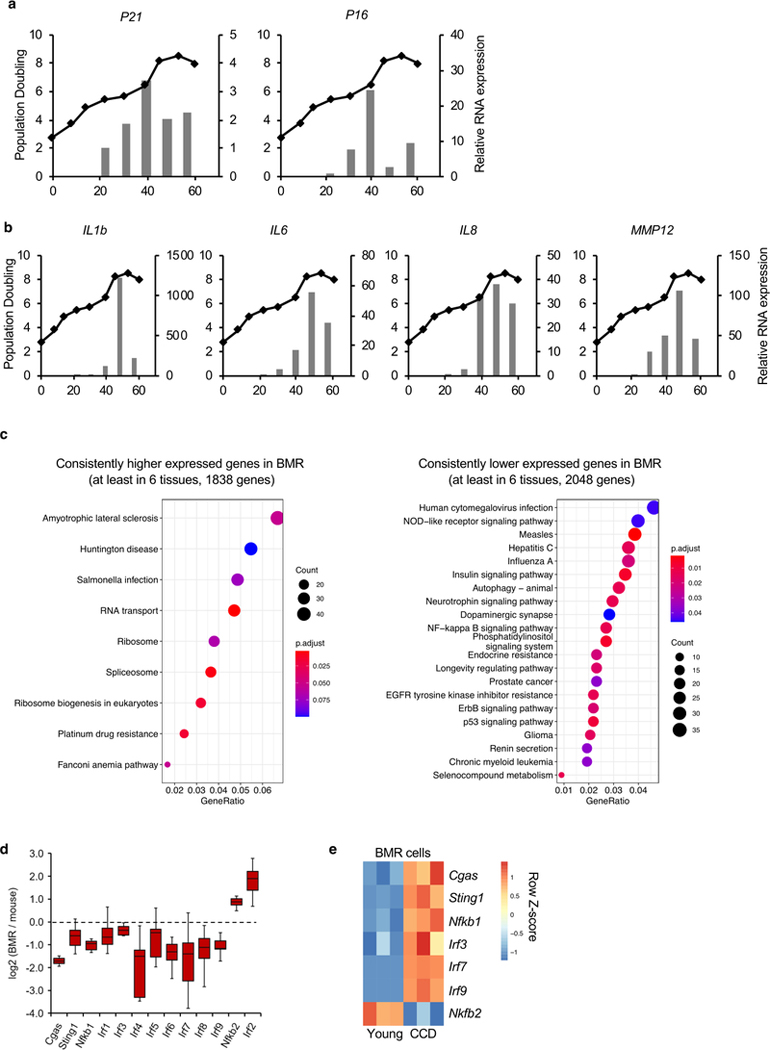

Extended Data Fig. 1. Activation of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in over-proliferating BMR cells and differential gene expression in BMR and mice tissues.

(a) qRT-PCR showing senescence markers P21 and P16 were increased with proliferation of BMR cells. (b) SASP factors IL1b, IL6, IL8, and MMP12 were increased with proliferation of BMR cells. (c) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of consistently up-regulated and down-regulated genes in the BMR tissues. RNA samples from 8 different tissues, including intestine, kidney, liver, lung, muscle, skin, spleen, and white adipose tissues (WAT) of BMR and mice were sequenced. A gene is defined as consistently up-regulated gene if it expresses higher in BMR than in mice in at least six tissues. P values were adjusted by FDR. (d) A boxplot showing different fold changes of genes from IFN and NF-κB pathways comparing BMR and mice tissues. Center lines represent median, bounds of box are the 1st quartile and 3rd quartile, and whiskers are drawn down to the 10th percentile and up to the 90th percentile. (e) A heatmap showing differential gene expression in BMR CCD cells.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Transcriptional start sites of B1 and L1 in BMR CCD cells.

(a) Transcriptional start sites of B1 and L1 in CCD cells of BMR. 5’ RACE was performed using BMR fibroblasts undergoing CCD. The RACE product was ligated into T vector and colonies were sequenced. A multiple alignment of the products was generated against the consensus SINE B1 sequence or a predicted active L1 family homologous to mouse L1MdaI, respectively. The alignment was generated with Clustal Omega and displayed by Jalview. The location of gene-specific primer 2 (GSP2) for both B1 and L1 were shown under the consensus sequence. (b) Summary of the mapping data of L1 5’ RACE. The location of transcription start sites were shown relative to the consensus start site.

Extended Data Fig. 3. RNA expression of SINE B1, B2 and IFNB1 in carcinogen DMBA/TPA treated BMR and mouse skin.

BMR and mice were topically treated with DMBA followed by treatment of TPA 3 days after DMBA. Two weeks after treatment, biopsy was taken from treated area, and RNA was extracted. Expression of SINE B1, B2 and IFNB1 was determined by qRT-PCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 biological replicates of 2 technical repeats.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Naturally low levels of DNMT1 result in loss of DNA methylation and SASP in over-proliferating BMR cells.

(a) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of DNA samples from BMR and mouse fibroblasts with low and high PDs. The Average linkage hierarchical clustering is based on the inter-array correlation coefficient (Pearson correlation). The cluster branches (first color band) correspond to species (second color band, blue = BMR, cyan = mouse). Third color band: high PD (O; black) versus low PD (Y; white). (b) A heatmap showing differentially methylated elements determined using Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP). Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were annotated against BMR genome. Totally 39 TE families were hyper-methylated and 60 TE families were hypo-methylated in dying BMR cells. Hypo-methylated TEs are enriched with B1 (especially PB1D9 family) and L1. (c) A heatmap showing generally lower expression levels of DNMT1 in 8 different tissues of BMR than mice. (d) alignment of partial sequence of human, mouse and BMR DNMT1 protein including immunogen recognized by the antibody used (Abcam ab13537). The immunogen is highly conserved across species, which is identical between human and BMR, and only 3 different amino acids different in mouse DNMT1. (e) Western blot detecting endogenous DNMT1 of primary and Large T transformed BMR cells. Large T is known to elevate DNMT1 expression. The significant band shows that the antibody is capable to detect BMR DNMT1. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (f) qRT-PCR showing overexpression of human DNMT1 in BMR cells. (g) Overexpression of DNMT1 restored global DNA methylation in BMR cells. (h) qRT-PCR showing repressed senescence factors by overexpression of DNMT1. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. BMR cells undergo DNA damage induced by IFN.

(a) Images and quantification of comet assay detecting DNA damage of BMR cells with proliferation. Scale bar, 10 μM. (b) Images and quantification of immunofluorescence detecting γH2AX foci of BMR cells with proliferation. Scale bar, 5 μM. (c) DNA damage response of BMR cells with proliferation. Western blot was performed to show the phosphorylation of Chk2 (Thr68) and p53 (Ser15). The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (d) Comet assay showing reduced DNA damage by overexpression of DNMT1. Scale bar, 10 μM. (e) Comet assay showing DNA damage induced by IFN. Young, growing BMR cells were treated with either medium containing BMR IFN or conditioned medium from old, dying BMR cells for 12 days before harvesting for comet assay. Scale bar, 10 μM. Tail DNA percentage (a, d, and e) or γH2AX (b) foci were quantified from 100 cells per group. Data are mean ±. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) treatment reduces RNA/DNA hybrids and represses cGAS-STING pathway.

(a) Images of cytoplasmic double-stranded (ds) RNA in young and dying BMR cells stained with J2 antibody. Cells treated with RNase III and with secondary antibody only lost the signals, confirming the specificity of J2 antibody recognizing dsRNA. Scale bar, 5 μM. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (b) Images of cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids in BMR cells stained with S9.6 antibody. Treatment of RNase H, which specifically degrades RNA/DNA hybrids, and with secondary antibody only didn’t yield signals, confirming that S9.6 antibody specifically recognizes RNA/DNA hybrids. Scale bar, 5 μM. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (c) Reduced cytoplasmic RNA/DNA hybrids by NRTIs treatment stained by S9.6 antibody in BMR cells. Scale bar, 5 μM. Immunofluorescence intensities were quantified from 30 cells per group. (d) Comet assay showing reduced DNA damage by NRTIs treatment in BMR cells. Scale bar, 10 μM. Tail DNA percentages were quantified from 100 cells per group. (e-f) knockdown of cGAS (e) and STING (f) were determined by qRT-PCR and western blot. (g) growth curve showing that knockdown of dsRNA sensing genes TLR3, MAVS, MDA5, and IRG-1 didn’t rescue CCD. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Roles of DNMT1 and RTEs in tumorigenesis in mice and human cells.

(a) Knockdown of DNMT1 in HeLa and HT1080 cancer cells as determined by Western blot. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (b-c) Knockdown of DNMT1 repressed proliferation of HT1080 cells in vitro. Clonogenic assay was performed with crystal violet staining and colonies areas were quantified (c). N = 3 technical replicates. Experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (d) Growth curve of DMBA/TPA-induced papilloma in mice treated with or without Abacavir. Abacavir treated alone repressed DMBA/TPA induced papilloma. Experiment was performed using eight animals for each group. (e) Images of SKH1 hairless mice with papilloma induced by DMBA/TPA. 5-Aza repressed formation of papilloma, while Abacavir restored this repression. (f) qRT-PCR showing overexpression of SINE B1 in HeLa cells. N = 3 technical replicates. (g) Western blot showing overexpression of L1 (ORFeus) in HeLa cells by detecting ORF1p. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. (h) qRT-PCR showing activation of IFNB1 in HeLa cells by overexpression of SINE B1 and L1 (ORFeus). N = 3 technical replicates. Data are mean ± SD (c, f, and h) or mean ± SEM (d). * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-sided t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health to Z.Zhang. (AG047200), A.S. (AG047200) and V.G. (AG047200; AG051449)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Seluanov A, Gladyshev VN, Vijg J & Gorbunova V Mechanisms of cancer resistance in long-lived mammals. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 433–441 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorbunova V et al. Cancer resistance in the blind mole rat is mediated by concerted necrotic cell death mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 19392–19396 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manov I et al. Pronounced cancer resistance in a subterranean rodent, the blind mole-rat, Spalax: in vivo and in vitro evidence. BMC Biol 11, 91 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nevo E Mosaic evolution of subterranean mammals : regression, progression, and global convergence. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourque G et al. Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome biology 19, 199 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lander ES et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mouse Genome Sequencing, C. et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pace JK 2nd & Feschotte C The evolutionary history of human DNA transposons: evidence for intense activity in the primate lineage. Genome Res 17, 422–432 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]