Abstract

Objectives

To identify factors associated with COVID-19 test positivity and assess viral and antibody test concordance.

Design

Observational retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Optum de-identified electronic health records including over 700 hospitals and 7000 clinics in the USA.

Participants

There were 891 754 patients who had a COVID-19 test identified in their electronic health record between 20 February 2020 and 10 July 2020.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Per cent of viral and antibody tests positive for COVID-19 (‘positivity rate’); adjusted ORs for factors associated with COVID-19 viral and antibody test positivity; and per cent concordance between positive viral and subsequent antibody test results.

Results

Overall positivity rate was 9% (70 472 of 771 278) and 12% (11 094 of 91 741) for viral and antibody tests, respectively. Positivity rate was inversely associated with the number of individuals tested and decreased over time across regions and race/ethnicities. Antibody test concordance among patients with an initial positive viral test was 91% (71%–95% depending on time between tests). Among tests separated by at least 2 weeks, discordant results occurred in 7% of patients and 9% of immunocompromised patients. Factors associated with increased odds of viral and antibody positivity in multivariable models included: male sex, Hispanic or non-Hispanic black or Asian race/ethnicity, uninsured or Medicaid insurance and Northeast residence. We identified a negative dose effect between the number of comorbidities and viral and antibody test positivity. Paediatric patients had reduced odds (OR=0.60, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.64) of a positive viral test but increased odds (OR=1.90, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.23) of a positive antibody test compared with those aged 18–34 years old.

Conclusions

This study identified sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 test positivity and provided real-world evidence demonstrating high antibody test concordance among viral-positive patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, molecular diagnostics, public health, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This large retrospective cohort study of >800 000 patients contributes to COVID-19 test surveillance data and targeted studies by identifying factors associated with viral and antibody test positivity among those tested.

This study provides important real-world evidence concerning antibody test concordance following a positive viral test among patients who received both types of tests.

We captured COVID-19 viral and antibody tests in adults and paediatric patients and identified novel findings related to positivity by test type and age.

Electronic health records provide a broad set of sociodemographic and clinical data but do not provide complete and salient information such as exposure, preclinical symptoms, testing outside of the healthcare system and living situation.

The electronic health records did not include information on the specific tests used that would have allowed for an assessment of test characteristics.

Background

The global COVID-19 pandemic has taken an enormous toll on human health and the economy. As of 22 June 2021, surveillance in the USA estimated approximately 33.5 million cases and 600 000 deaths across the nation with one of the highest incidence rates in the world.1 2

SARS-CoV-2 testing is a critical but challenging component of both surveillance and treatment decisions. Variable test access, quality and reliability have been key considerations in our understanding of COVID-19.3–9 Public health surveillance and targeted studies provide important information related to patient characteristics and symptoms experienced during active COVID-19 infections.10–18 As we enter a new stage in the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions ease due to successful vaccination efforts, viral testing remains an important tool for rapid identification of active infections and reducing transmission. Antibody testing is also important because it helps us understand immunity to COVID-19 at both the individual and community level.19 Information regarding antibody testing in clinical practice is sparse and concordance between viral and antibody tests has largely focused on assessment of test characteristics and seroconversion among special populations.20–22 Thus, we sought to generate real-world evidence related to factors associated with COVID-19 viral and antibody testing and positivity, as well as assessment of test concordance in routine clinical practice in the USA.

Our specific study objectives were to: use electronic health records (EHRs) to characterise patients tested for COVID-19 according to test type (viral, antibody) and test result; to assess temporal trends in testing and positivity rates (PRs) and evaluate antibody test concordance following a positive viral test among patients who received definitive results for both tests; and lastly, to estimate the relative odds of a positive COVID-19 test result compared with a negative test by test type via multivariable logistic regression.

Methods

Data source

We used the Optum de-identified COVID-19 EHR dataset, containing patient-level health records from 20 February 2019 through 10 July 2020, to identify patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 antibodies. This dataset was sourced from Optum’s longitudinal EHR repository derived from a national sample of inpatient and outpatient medical records from more than 700 hospitals and 7000 clinics. The COVID-19 EHR dataset included patients who had documented clinical care with a diagnosis of COVID-19 or acute respiratory illness after 1 February 2020 and/or COVID-19 antibody or viral testing. Data were de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Expert Determination Method and managed according to Optum customer data use agreements. The EHRs did not capture detailed information on the specific subtype or manufacturer for COVID-19 viral and antibody tests that would have enabled assessment of test sensitivity and/or specificity. Further, the EHRs did not capture detailed information related to residence, such as zip code or independent versus institutional setting (eg, nursing home).

Patient and public involvement

This study did not include patient or public involvement in the design, conduct or choice of outcomes.

Study population

We included patients of all ages if they satisfied the criteria required for entry into one or more of the below test cohorts and the index date occurred between 20 February 2020 and 10 July 2020.

Cohort definitions

Cohort 1 (C1) consisted of patients with a laboratory test or procedural code for either a viral (molecular or antigen test) or antibody test based on Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), Current Procedural Terminology Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, Proprietary Laboratory Analyses codes or string search for test names (online supplemental file A). We considered the C1 index date as the first COVID-19 test, regardless of type (viral or antibody).

bmjopen-2021-051707supp001.pdf (821.3KB, pdf)

As a subset of C1, we defined cohort 2 (C2) as patients whose first observed COVID-19 test was a viral test and indexed them on the date of this test.

As a subset of C1, we indexed cohort 3 (C3) patients on the first antibody test received based on laboratory or procedural data source as previously described. We identified C3 patients regardless of prior viral test to enable full characterisation of antibody testing and assessment of concordance between viral and antibody tests.

Data analysis

For C2 and C3 patients, we classified test results as positive, negative and not definitive.

Clinical context/setting variables, including symptoms and vital signs (0–7 days pre-index), were defined using diagnostic codes (online supplemental file B). We chose a window 0–7 days to ensure that identified symptoms were related to the reason for testing. Additionally, we adapted a definition of time since first COVID-like illness (CLI) based on the CLI definition endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists23 (online supplemental file C). We identified comorbidities using diagnostic codes (≥1 code in any position 0–365 days pre-index; online supplemental file D) among patients with at least 365 days of database history. We used string searches and LOINC codes to evaluate laboratory tests for respiratory isolates (0–7 days pre/post-index).

Descriptive analysis

We evaluated the distribution of variables and PRs by cohort and definite test result. To assess the representativeness of our study population, we compared the distribution of key sociodemographic factors in our study cohorts to all Optum beneficiaries and the 2019 US census population.

We evaluated temporal trends in several variables (including PR), assessed co-occurring symptoms/conditions among viral-positive patients, and estimated concordance between test results for patients who received a positive initial viral test and definitive subsequent antibody results.

Models to identify factors impacting test positivity

Multivariable logistic regression models were fit to assess factors impacting test positivity for the following binary outcomes: (a) positive initial viral test compared with a negative initial viral test among C2 patients and (b) positive initial antibody test compared with a negative initial antibody test among C3 patients.

Models were limited to the subset of patients who had a definite test result and >365 days pre-index database history to ensure capture of existing comorbidities. Candidate variables for the models included those identified from prior research and commonly (>3% of patients) occurring symptoms. Non-significant interactions and collinear variables were not included. In both models, multiple imputation was used to address missing data for variables with <25% of missingness using multivariate imputation by chained equations (online supplemental files E and F).

The final models included sociodemographics, clinical/setting variables, comorbidities, region and study week. Additionally, the C2 model included a variable for coinfections and an interaction term between region and study week. The C3 model also included prior viral test results to assess the role of a clinically recognised active infection on subsequent immune response to COVID-19 and to allow other factors to be evaluated independent from viral positivity.

Results

Descriptive

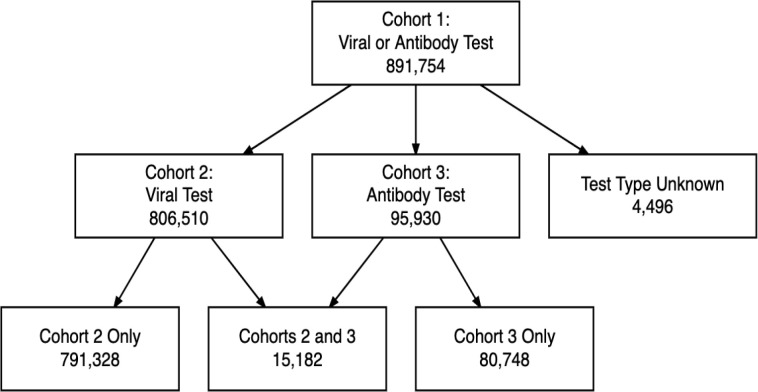

We identified 891 754 patients in our overall study population (n=806 510 in C2 with a first viral test; n=95 930 in C3 with an antibody test at any time; n=15 182 in both C2 and C3; n=4496 in C1 but not in C2 or C3 due to unknown test type) (figure 1). These patients were predominantly adult, female, non-Hispanic white, commercially insured and Midwest/Northeast residents (table 1). A majority of patients had no CLI identified (77%, 76%, and 83% C1, 2 and 3, respectively) nor underlying comorbidity (43%, 42%, and 54% C1, 2, and 3, respectively) (online supplemental files G and H). Paediatric patients were under-represented in our study population relative to both the Optum and census populations.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study population.

Table 1.

Description of study population (cohorts 1–3) and comparison with source population(s)

| Variable | Level | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Optum* | 2019 US census projections† |

| n | 891 754 | 806 510 | 95 930 | 105 632 445 | ||

| Years in database (median (IQR)) | 7.5 (3.3–11.7) | 7.6 (3.3–11.8) | 6.3 (3.4–9.5) | |||

| Age (min, Q1, median, Q3, max)‡ | (0, 35, 52, 67, 89) | (0, 34, 52, 67, 89) | (0, 38, 53, 65, 89) | |||

| Age (category) (%) | <18 | 42 458 (4.8) | 39 691 (4.9) | 2962 (3.1) | 16 314 768 (15.4) | 73 039 150 (22.3) |

| 18–34 | 176 594 (19.8) | 163 959 (20.3) | 15 197 (15.8) | 22 654 539 (21.4) | 76 159 527 (23.2) | |

| 35–44 | 123 393 (13.8) | 110 559 (13.7) | 15 290 (15.9) | 13 843 370 (13.1) | 41 659 144 (12.7) | |

| 45–54 | 132 459 (14.9) | 117 575 (14.6) | 16 882 (17.6) | 13 198 315 (12.5) | 40 874 902 (12.5) | |

| 55–64 | 161 578 (18.1) | 142 687 (17.7) | 20 943 (21.8) | 14 524 592 (13.8) | 42 448 537 (12.9) | |

| 65+ | 255 244 (28.6) | 232 017 (28.8) | 24 649 (25.7) | 24 513 127 (23.2) | 54 058 263 (16.5) | |

| Unknown | 28 (0.0) | 22 (0.0) | 7 (0.0) | 583 734 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sex (%) | Female | 518 193 (58.1) | 467 798 (58.0) | 57 655 (60.1) | 56 464 965 (53.5) | 166 582 199 (50.8) |

| Male | 372 835 (41.8) | 338 043 (41.9) | 38 213 (39.8) | 48 524 416 (45.9) | 161 657 324 (49.2) | |

| Unknown | 726 (0.1) | 669 (0.1) | 62 (0.1) | 643 064 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race (%) | African American | 103 822 (11.6) | 98 509 (12.2) | 6418 (6.7) | 9 943 721 (9.4) | 44 075 086 (6.6) |

| Asian | 20 211 (2.3) | 17 846 (2.2) | 3439 (3.6) | 2 241 484 (2.1) | 19 504 862 (2.9) | |

| Caucasian | 627 697 (70.4) | 561 756 (69.7) | 72 187 (75.2) | 62 416 126 (59.1) | 250 522 190 (37.6) | |

| Unknown | 140 024 (15.7) | 128 399 (15.9) | 13 886 (14.5) | 30 987 769 (29.3) | 352 424 973 (52.9) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | Hispanic | 57 556 (6.5) | 55 279 (6.9) | 2881 (3.0) | 6 760 109 (6.4) | 60 572 237 (18.5) |

| Not Hispanic | 681 960 (76.5) | 615 521 (76.3) | 73 774 (76.9) | 65 041 424 (61.1) | 267 667 286 (81.5) | |

| Unknown | 152 238 (17.1) | 135 710 (16.8) | 19 275 (20.1) | 33 787 567 (32.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | Non-Hispanic white | 543 846 (61.0) | 486 204 (60.3) | 62 602 (65.3) | ||

| Asian | 17 821 (2.0) | 15 930 (2.0) | 2852 (3.0) | |||

| Hispanic | 23 403 (2.6) | 22 213 (2.8) | 1442 (1.5) | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 92 704 (10.4) | 88 262 (10.9) | 5313 (5.5) | |||

| Unknown | 213 980 (24.0) | 193 901 (24.0) | 23 721 (24.7) | |||

| Region (%) | Midwest | 440 256 (49.4) | 409 462 (50.8) | 32 203 (33.6) | 44 002 759 (42.9) | 68 329 004 (20.8) |

| Northeast | 252 563 (28.3) | 209 676 (26.0) | 53 807 (56.1) | 15 414 025 (15.0) | 55 982 803 (17.1) | |

| South | 105 666 (11.8) | 96 808 (12.0) | 6509 (6.8) | 25 105 142 (24.4) | 125 580 448 (38.3) | |

| West | 65 625 (7.4) | 64 569 (8.0) | 1652 (1.7) | 10 678 628 (10.4) | 78 347 268 (23.9) | |

| Unknown | 27 644 (3.1) | 25 995 (3.2) | 1759 (1.8) | 7 472 962 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Insurance type (%) | Commercial | 493 302 (55.3) | 441 114 (54.7) | 61 118 (63.7) | ||

| Medicaid | 109 133 (12.2) | 104 537 (13.0) | 4947 (5.2) | |||

| Medicare | 163 346 (18.3) | 146 890 (18.2) | 17 267 (18.0) | |||

| Other payor type | 47 538 (5.3) | 45 417 (5.6) | 2399 (2.5) | |||

| Uninsured | 4902 (0.5) | 4851 (0.6) | 38 (0.0) | |||

| Unknown | 73 533 (8.2) | 63 701 (7.9) | 10 161 (10.6) | |||

| Index setting (%) | Ambulatory | 363 066 (40.7) | 317 100 (39.3) | 54 785 (57.1) | ||

| Inpatient | 252 939 (28.4) | 251 064 (31.1) | 2563 (2.7) | |||

| Lab | 93 962 (10.5) | 82 673 (10.3) | 12 645 (13.2) | |||

| Other | 124 085 (13.9) | 111 630 (13.8) | 13 570 (14.1) | |||

| Unknown | 57 702 (6.5) | 44 043 (5.5) | 12 367 (12.9) | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Score (%) | 0 | 386 110 (43.3) | 340 416 (42.2) | 51 374 (53.6) | ||

| 1 | 165 058 (18.5) | 146 543 (18.2) | 20 547 (21.4) | |||

| 2 | 82 845 (9.3) | 75 803 (9.4) | 8080 (8.4) | |||

| 3 | 49 290 (5.5) | 46 174 (5.7) | 3691 (3.8) | |||

| 4 | 31 553 (3.5) | 30 211 (3.7) | 1677 (1.7) | |||

| 5 | 20 945 (2.3) | 20 294 (2.5) | 844 (0.9) | |||

| 6 | 13 350 (1.5) | 13 038 (1.6) | 440 (0.5) | |||

| 7+ | 14 485 (1.6) | 14 290 (1.8) | 321 (0.3) | |||

| Insufficient (≤365 days) of database history§ | 128 118 (14.4) | 119 741 (14.8) | 8956 (9.3) | |||

| BMI (%) | Normal | 129 668 (14.5) | 114 657 (14.2) | 17 576 (18.3) | ||

| Underweight | 25 684 (2.9) | 23 974 (3.0) | 1981 (2.1) | |||

| Overweight | 235 020 (26.4) | 207 080 (25.7) | 31 326 (32.7) | |||

| Obese | 280 185 (31.4) | 254 521 (31.6) | 28 055 (29.2) | |||

| Unknown | 221 197 (24.8) | 206 278 (25.6) | 16 992 (17.7) |

*Race/ethnicity data delivered in August 2020, other data delivered in June 2020.

†Based on the 2019 US census population estimates by age group, sex, race and Hispanic origin.

‡0, 25th, 50th, 75th and 100th percentiles.

§Patients with ≤365 days of database history were not considered for comorbidities.

BMI, body mass index.

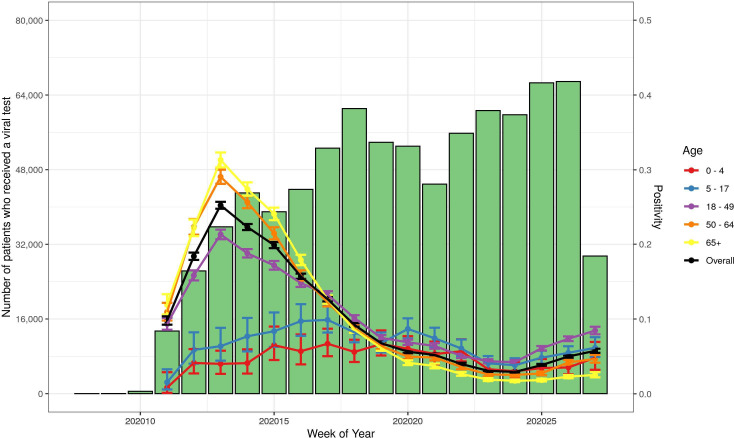

SARS-CoV-2 viral test reporting increased steadily in the week of 11 March 2020 with PRs peaking 2 weeks later driven primarily by data from the Northeast. Antibody test reporting began the week of 22 April 2020 with a concurrent modest peak in PRs, again driven largely by Northeast data. PR was inversely associated with the number of individuals tested and decreased over time across regions and race/ethnicities (online supplemental file I).

Cohort 2: viral test

C2 consisted largely of adult (95%), female (58%), non-Hispanic (77%), white (70%), residents of the Midwest (51%) and those who had commercial insurance (55%; online supplemental file J). Approximately 50% of patients with >1 year of database history had a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)=0 compared with approximately 40% of US adults,24 while 77% of our study population (with non-missing body mass index (BMI)) were overweight or obese compared with approximately 72% of US adults.25 Information on the type of specimen collected for a viral test was missing in 81% of patients.

The overall PR in C2 was 9% (70 472 of 771 278). Viral test results and PRs for each of the measured cofactors are provided in online supplemental file J.

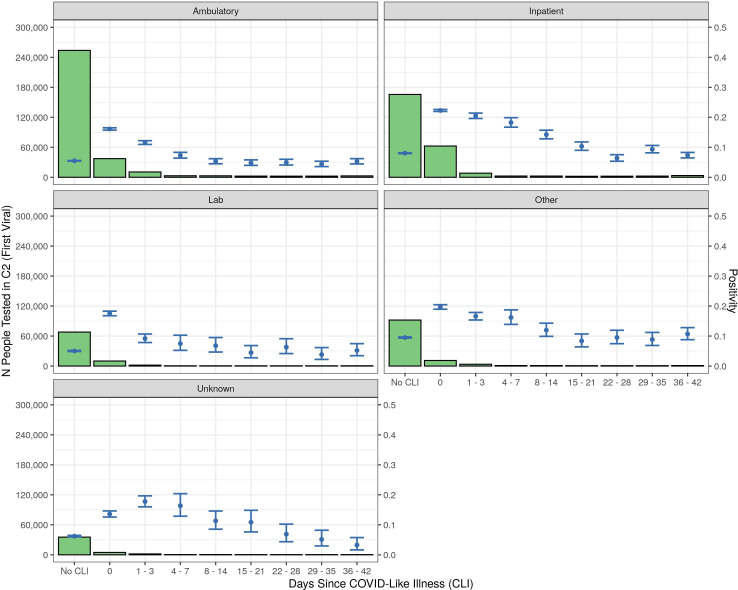

Most C2 patients did not have a CLI recorded in the 6 weeks prior to their test (76% of C2 patients and 57% viral-positive patients; figure 2; online supplemental file J). Among those with a prior CLI, the median interval between reported CLI and initial definitive test was 0 days and 83% occurred ≤7 days of their test result. Coinfections were rare (<0.1%).

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 viral test positivity and days since COVID-like illness by setting. C2, cohort 2.

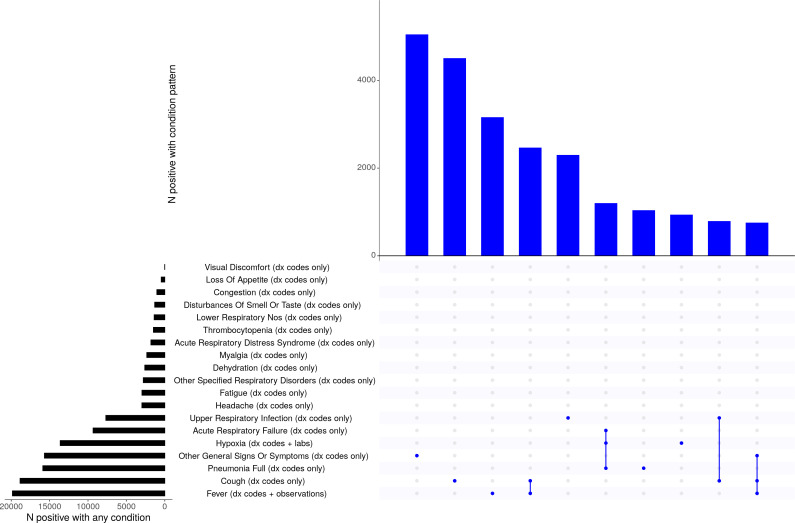

Figure 3 displays common symptoms and intersecting sets of these symptoms in patients who had a positive viral test in C2.

Figure 3.

Frequency and co-occurrence of common conditions in patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 via viral test.

Cohort 3: antibody test

Similar to C2, C3 patients were predominantly adult (97%), female (60%), non-Hispanic (77%), white (75%) and commercially insured (64%; online supplemental file K). Slightly more than half of the patients lived in the Northeast (56% vs 26% for C2). Approximately 75% of patients (with a reported BMI) were overweight or obese and 59% of patients with >1 year of database history had a CCI score=0.

Among C3, the overall PR was 12% (11 094 of 91 741). Antibody test results and PRs for each of the measured cofactors are provided in online supplemental file K.

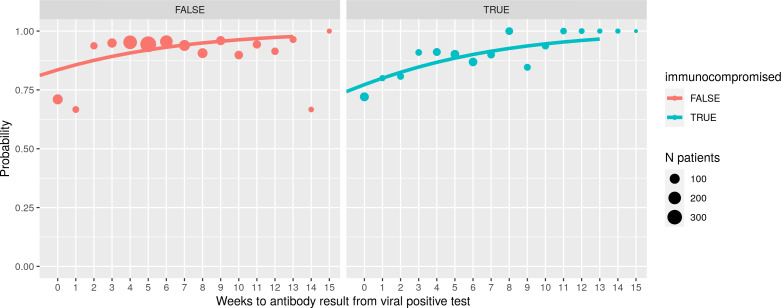

Concordance between positive initial viral test and subsequent antibody test

Among patients who received a positive viral test followed by (or on the same day as) a definitive antibody test (n=2035), overall concordance was 91%. Discordant test results due to lack of seroconversion or inaccurate test(s) were assessed via a positive viral test followed by a negative antibody test. Discordant results were more common when the tests were performed <2 weeks apart (0 weeks apart=28.6%, 1 week apart=28.2%) compared with patients who had tests spaced at least 2 weeks apart (2 weeks=12.1%, 3 weeks=5.9%, 4 weeks=5.4%, 5 weeks=6.2%, 6 weeks=6.5%, 7 weeks=7.0%, 8 weeks=6.6%, 9 weeks=7.0% and 10 weeks=8.8%). Restricting the analysis to patients who had tests separated by at least 2 weeks (n=1828), discordant results occurred in 6.5% (119 of 1828) of all patients and 8.8% (35 of 399) of immunocompromised patients (ie, those with any cancer, HIV/AIDS, rheumatic disease or renal disease). Figure 4 depicts the probability of agreement between the initial viral positive test and subsequent antibody positive test over time and according to immunocompromised status.

Figure 4.

Density of agreement among patients who received an initial viral positive test and subsequent antibody positive test by weeks between tests and immunocompromised status.

Paediatric patients (<18 years)

Paediatric patients were under-represented in our study population (C1=4.8%, C2=4.9%, C3=3.1%) relative to both the underlying Optum (15.4%) and census populations (22.3%), suggesting lower testing rates in this population. Paediatric patients had a viral PR of 6% and, while the PR was consistently lower among paediatric patients compared with the overall C2 population (9%), Hispanic, underweight and Medicaid-insured children were more likely to be tested (online supplemental files J and L). Paediatric patients had an antibody PR of 17% compared with overall C3 PR of 12% with a particularly high PR among patients with Medicaid insurance, prior positive viral test and >7 days since CLI (online supplemental file M). Of note, those underweight and/or hospitalised were more frequently tested compared with the overall C3 (online supplemental files K and M).

Multivariable logistic model results

Cohort 2: viral test

Of the 806 510 patients in C2, 657 112 (81%) fit the criteria for the model of viral test positivity (>1 year of database history and a definite first viral test).

Sociodemographic

The odds of a positive test were not meaningfully different among adults of different ages, when mutually adjusted for other factors (figure 5, online supplemental file N); however, paediatric patients had a markedly decreased odds of a positive test relative to young adults (18–34 years) (OR=0.60, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.64).

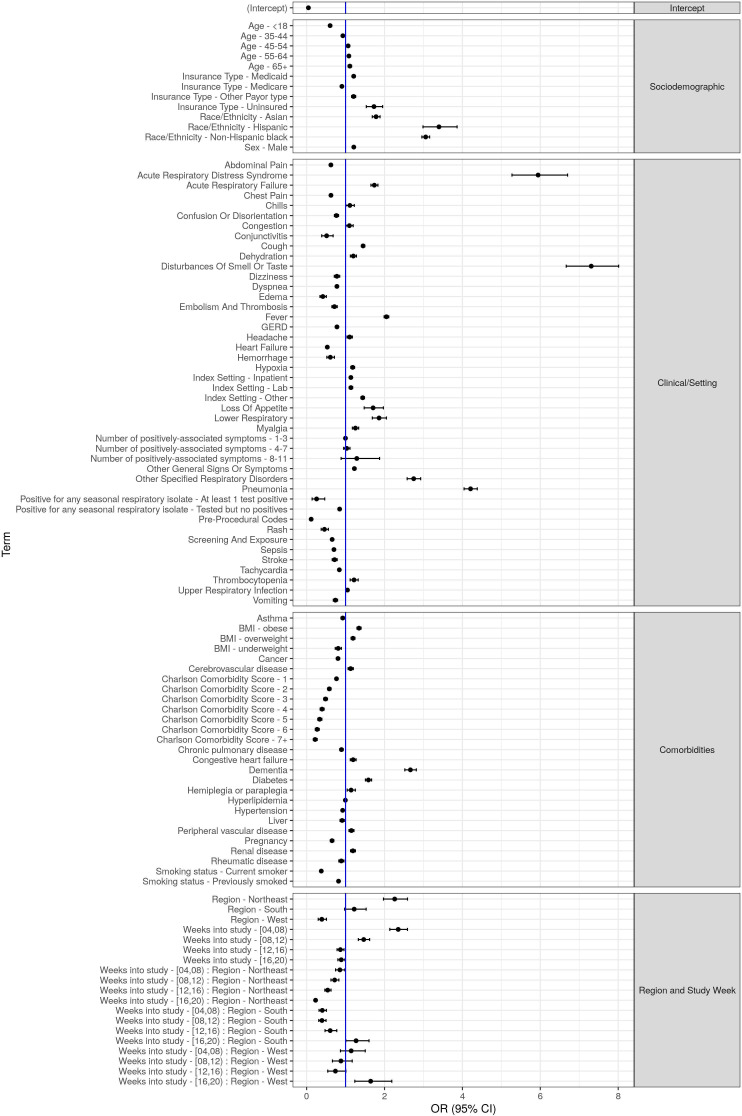

Figure 5.

ORs and 95% CIs of SARS-CoV-2-positive viral test obtained via multivariable logistic regression. BMI, body mass index; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Hispanic, non-Hispanic black and Asian patients had increased odds of viral positivity compared with non-Hispanic white patients (OR and 95% CI=3.40 (2.99 to 3.86); 3.06 (2.96 to 3.16); and 1.78 (1.69 to 1.89), respectively). Uninsured patients and those with Medicaid had moderately increased odds of testing positive, while Medicare patients had a decreased odds, relative to patients with commercial insurance (OR and 95% CI=1.73 (1.53 to 1.95); 1.21 (1.17 to 1.25); and 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94), respectively). Men had an increased odds of positivity relative to women (OR=1.21, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.24).

Clinical/setting

To assess severity, symptomatic status and viral test positivity, we investigated the importance of healthcare setting and symptoms. We observed modest significant associations between healthcare setting and positivity (OR=1.14, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.17) for patients tested in the hospital compared with outpatient setting.

We identified several symptoms/co-occurring diagnoses that were significantly associated with a positive test, including: disturbance of smell and/or taste (OR=7.31, 95% CI 6.67 to 8.01), acute respiratory distress (OR=5.94 to 95% CI 5.27 to 6.70), pneumonia (OR=4.21, 95% CI 4.04 to 4.38), lower respiratory infection (OR=1.86, 95% CI 1.69 to 2.05), loss of appetite (OR=1.71, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.97) and cough (OR=1.45, 95% CI 1.41 to 1.49). Other conditions with modestly significant positive and negative associations are shown in figure 5 and online supplemental file N.

Comorbidities

We found an inverse dose–response relationship between CCI score and viral positivity indicating that patients with more comorbidities had lower odds of a positive result. However, assessment of individual conditions identified an increased odds of a positive test among patients with dementia (OR=2.66, 95% CI 2.52 to 2.82) and diabetes (OR=1.59, 95% CI 1.51 to 1.67) that persisted in mutually exclusive exploratory models restricted to 65+ years suggesting limited residual confounding by age. Modest significant associations were identified for patients with conditions such as renal disease (OR=1.19, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.25) and congestive heart failure (OR=1.20, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.27) (figure 5; online supplemental file N). Further, overweight and obese patients had an increased odds of a positive test (OR=1.19, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.24 and OR=1.34, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.40, respectively) relative to patients with normal BMI.

Region and study week

There was a significant interaction between region and study week on the odds of a positive test. Our model reflects high transmission in the Northeast region early in the pandemic with attenuated effects in this region over time suggesting transmission control relative to other regions such as the Midwest (figure 5). Conversely, the South experienced increased ORs in interaction terms with study week, while the West experienced a J-shaped curve with the highest OR in the final study week.

Cohort 3: antibody test

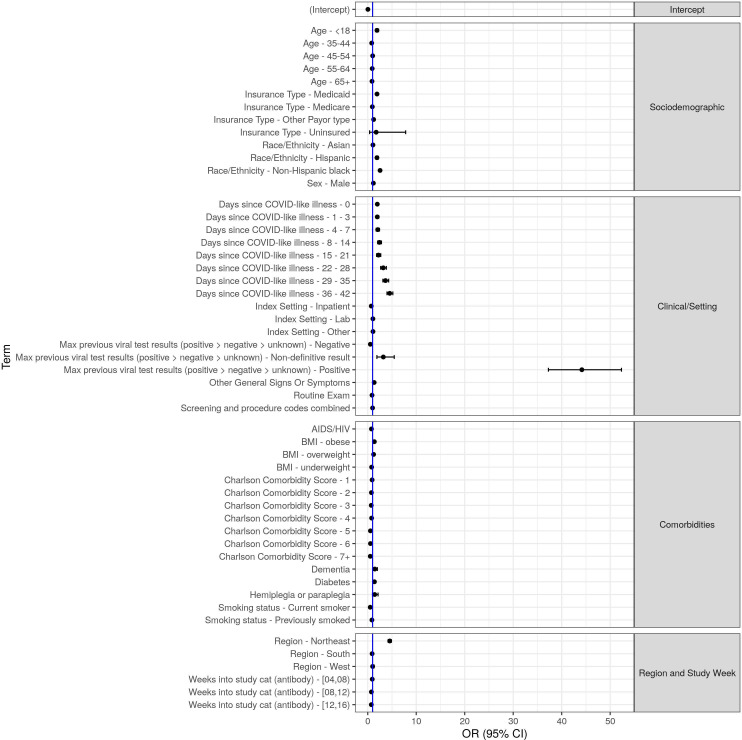

Of the 95 930 patients in C3, 83 184 (87%) fit the eligibility criteria for the logistic model of antibody test positivity (figure 6; online supplemental file O).

Figure 6.

ORs and 95% CIs of COVID-19-positive antibody test obtained via multivariable logistic regression. BMI, body mass index.

Sociodemographic

We detected increased odds of a positive antibody test among patients who: were <18 years (OR=1.90, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.23 compared with 18–34 years); had Medicaid or no insurance (OR=1.91, 95% CI 1.75 to 2.08 and OR=1.73, 95% CI 0.38 to 7.82 compared with patients with commercial insurance); were non-Hispanic black or Hispanic patients (OR=2.54, 95% CI 2.32 to 2.77 and OR=1.90, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.21 compared with non-Hispanic white); lived in the Northeast region (OR=4.53, 95% CI 4.22 to 4.86 compared with the Midwest); or were male (OR=1.16, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.22).

Clinical/setting

As expected, the odds of a positive antibody test among patients with a prior viral positive test were particularly high (OR=44.16, 95% CI 37.26 to 52.33) and low (OR=0.54, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.58) for patients with a prior negative viral test compared with patients who did not receive a prior viral test. The odds of a positive antibody test increased with the number of days since CLI (ORs ranged from 1.97, 95% CI 1.81 to 2.14; to 4.53, 95% CI 3.97 to 5.18) relative to patients without a prior CLI.

The odds of a positive test were lower among patients tested in the hospital relative to ambulatory setting (OR=0.73, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.92). Similar to C2 findings, C3 patients who had a routine general medical examination recorded were less likely to have a positive test result compared with patients without such a code (OR=0.88, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.94).

Comorbidities

Our assessment of the relationship between CCI score and antibody test positivity was consistent with results from C2. Specifically, we identified an inverse dose effect between CCI score and test positivity (OR ranged from 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.95; to 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.80 as the number of comorbidities increased from 1 to ˃7 relative to patients with a CCI score of 0). The significantly positive association between dementia, diabetes and BMI persisted in C3.

Conclusion

We characterised sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 testing and positivity in over 800 000 patients across the USA. Our study provides real-world clinical data that complement surveillance data and identifies novel findings related to patients, testing, and concordance between a viral positive test and subsequent antibody test.

We identified an imbalance in viral testing according to race/ethnicity and insurance status due to low proportion of tests and high PRs in minority populations and among patients with suboptimal insurance (online supplemental files I and J), as well as heightened positivity in our multivariable model (figure 5). The significance of race/ethnicity and insurance status in our C2 modelling suggests these effects are independent of symptoms, comorbidities, date, region and setting. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating the importance of societal and economic inequities, differential exposure and access to tests over the course of the pandemic.9 13 16 26–36

Our assessment of antibody test concordance among patients who received a prior positive viral test demonstrated high concordance particularly for patients who had an antibody test at least 2 weeks after a positive viral test reflecting the expected time needed for patients to mount an immune response to a SARS-CoV-2 infection and the clinical sensitivity of such tests.21 37 However, the precise time of infection relative to testing was impossible to identify given the data source used in this study. Discordant results assessed among patients with at least 2 weeks between a positive viral test and subsequent antibody test may reflect lack of seroconversion as well as suboptimal test characteristics or timing of the test(s). However, our findings were comparable with a prior study of healthcare workers and first responders that reported 6% of the patients did not have antibodies following infection.38 We identified slightly lower concordance among immunocompromised patients.

We identified notable differences in PRs among paediatric patients depending on the type of test compared with the overall C2 and C3 patients, namely lower viral PR and higher antibody PR among paediatric patients compared with patients of all ages. Our findings may reflect variable test patterns and results due to differences in clinical presentation, symptomatic status, severity, immune response and detection in children, which is consistent with national surveillance data (figure 7).39–42

Figure 7.

Number of patients tested and per cent positive for initial SARS-CoV-2 viral test by age.

While EHRs may lack sensitivity for capturing symptoms, our findings support the importance of symptoms generally acknowledged in the existing literature, such as olfactory dysfunction, fever, cough and lower respiratory infections, and viral positivity.14 17 18 43 44

While patients with poor underlying health may be at higher risk of severe COVID-19, the negative association between multimorbidities and both viral and antibody test positivity is consistent with prior studies and may reflect reduced exposure due to behavioural changes and/or lower test thresholds.15 45–48 Exceptions were noted for patients in both C2 and C3 with obesity, diabetes and dementia, which are also associated with severe disease and have been identified in prior research.49–51 The increased odds of a positive test among patients with dementia may relate to increased exposure due to institutional living and to symptoms of dementia lowering compliance with prevention guidelines and increased testing by caregivers; however, we were unable to directly assess these possibilities within our data.

We recognise that differential access to, and thresholds for, testing exist and that not all EHRs are complete.51 We did not require a minimum follow-up period for inclusion into our study given our interest in test results that did not require extended follow-up and our desire to be as inclusive as possible. We assessed the representativeness of our study population to the Optum and census populations, and used days since CLI as a proxy for time since symptom onset. While we compared our study population with source populations, we were unable to directly describe the base population due to the nature of the de-identified Optum COVID-19 EHR data, nor were we able to assess test characteristics according to timing of infection or symptom onset, test manufacturer or specimen type.8 47

In summary, this large national study systematically identified sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 viral and antibody testing and positivity. We identified an imbalance in both viral and antibody tests among minority and underinsured patients. Our findings provide real-world evidence supporting high concordance between positive viral and subsequent antibody tests when tests were performed at least 2 weeks apart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xin Chen, Devika Chawla, Vince Yau, Tripthi Kamath and Jenny Chia for their review and input into this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LL, MHS and SR wrote the main manuscript text and MHS prepared the figures. LL, MHS, SR, DSK, FY and LT contributed to the study protocol and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: Genentech and Roche Diagnostics funded employee/s’ time for this research.

Competing interests: LL, MHS, SR, DSK and LT are employed by and hold shares in Genentech. FY is employed by and holds shares in Roche Diagnostics.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Optum but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Optum.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The protocol for this study is in line with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008). The authors conducted secondary research using de-identified data licensed from Optum in compliance with 45 CFR 164.514(a)–(c). The data had identifying information removed and were coded in such a way that the data could not be linked back to subjects from whom they were originally collected. This research used the data licensed by Optum and described above, does not require IRB or ethics review, as analyses with these data do not meet the definition of ‘research involving human subjects’ as defined within 45 CFR 46.102(f) which stipulates human subjects as living individuals about whom an investigator obtains identifiable private information for research purposes. Neither the provider of the data nor the researchers were able to link the data with identifiable individuals. Consent to participate was not applicable in this retrospective observational study of de-identified data.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC data covid tracker. Available: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days [Accessed 22 Jun 2021].

- 2.Johns Hopkins University Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center . COVID-19 data in motion: current date. Available: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ [Accessed 22 Jun 2021].

- 3.U.S Food and Drug Administration . In vitro diagnostics EUAs. individual EUAs for molecular diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. Available: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics-euas#individual-molecular [Accessed 10 Dec 2020].

- 4.Ward S, Lindsley A, Courter J, et al. Clinical testing for COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;146:23–34. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scohy A, Anantharajah A, Bodéus M, et al. Low performance of rapid antigen detection test as frontline testing for COVID-19 diagnosis. J Clin Virol 2020;129:104455. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak GC, Cheng PK, Lau SS, et al. Evaluation of rapid antigen test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. J Clin Virol 2020;129:104500. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lisboa Bastos M, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:M2516. 10.1136/bmj.m2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD013652. 10.1002/14651858.CD013652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman-Cribbin W, Tuminello S, Flores RM, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. Am J Prev Med 2020;59:326–32. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Information for health departments on reporting cases of COVID-19. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/reporting-pui.html [Accessed 10 Dec 2020].

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Cases, data, and surveillance. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/index.html [Accessed 10 Dec 2020].

- 12.Lan F-Y, Filler R, Mathew S, et al. COVID-19 symptoms predictive of healthcare workers' SARS-CoV-2 PCR results. PLoS One 2020;15:e0235460. 10.1371/journal.pone.0235460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jehi L, Ji X, Milinovich A, et al. Individualizing risk prediction for positive coronavirus disease 2019 testing: results from 11,672 patients. Chest 2020;158:1364–75. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perotte R, Sugalski G, Underwood JP, et al. Characterizing COVID-19: a chief complaint based approach. Am J Emerg Med 2021;45:398–403. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Bear T. Proposed clinical indicators for efficient screening and testing for COVID-19 infection using classification and regression trees (CART) analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020;20:1–4. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1822135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chadeau-Hyam M, Bodinier B, Elliott J, et al. Risk factors for positive and negative COVID-19 tests: a cautious and in-depth analysis of UK biobank data. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:1454–67. 10.1093/ije/dyaa134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudre CH, Lee KA, Lochlainn MN, et al. Symptom clusters in COVID-19: a potential clinical prediction tool from the COVID symptom study APP. Sci Adv 2021;7. 10.1126/sciadv.abd4177. [Epub ahead of print: 19 03 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:1037–40. 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim guidelines for COVID-19 antibody testing. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.html [Accessed 22 Jun 2021].

- 20.Milani GP, Dioni L, Favero C, et al. Serological follow-up of SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic subjects. Sci Rep 2020;10:20048. 10.1038/s41598-020-77125-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller TE, Garcia Beltran WF, Bard AZ, et al. Clinical sensitivity and interpretation of PCR and serological COVID-19 diagnostics for patients presenting to the hospital. Faseb J 2020;34:13877–84. 10.1096/fj.202001700RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakkar A, Pradhan K, Jindal S, et al. Patterns of seroconversion for SARS-CoV-2 IgG in patients with malignant disease and association with anticancer therapy. Nat Cancer 2021;2:392–9. 10.1038/s43018-021-00191-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020 interim case definition, 2020. Available: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/case-definition/2020/08/05/ [Accessed 15 Nov 2020].

- 24. Buttorff, Christine, Ruder T. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Obesity and overweight. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm [Accessed 10 Dec 2020].

- 26.Lamb MR, Kandula S, Shaman J. Differential COVID-19 case positivity in New York City neighborhoods: socioeconomic factors and mobility. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2021;15:209–17. 10.1111/irv.12816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003379. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muñoz-Price LS, Nattinger AB, Rivera F, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcomes among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2021892. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misa NY, Perez B, Basham K. Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 disease burden & mortality among emergency department patients in a safety net health system. Am J Emerg Med 2020;S0735-6757:30845–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baidal JW, Wang AY, Zumwalt K, et al. Social determinants of health and COVID-19 among patients in New York City. Res Sq 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-70959/v1. [Epub ahead of print: 15 Sep 2020]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin CA, Jenkins DR, Minhas JS, et al. Socio-demographic heterogeneity in the prevalence of COVID-19 during lockdown is associated with ethnicity and household size: results from an observational cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2020;25:100466. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittle RS, Diaz-Artiles A. An ecological study of socioeconomic predictors in detection of COVID-19 cases across neighborhoods in New York City. BMC Med 2020;18:271. 10.1186/s12916-020-01731-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang CH, Schwartz GG. Spatial disparities in coronavirus incidence and mortality in the United States: an ecological analysis as of may 2020. J Rural Health 2020;36:433–45. 10.1111/jrh.12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chamie G, Marquez C, Crawford E. SARS-CoV-2 community transmission disproportionately affects latinx population during shelter-in-place in San Francisco. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1101/2020.06.15.20132233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html [Accessed 10 Dec 2020].

- 36.La Marca A, Capuzzo M, Paglia T, et al. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in-vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod Biomed Online 2020;41:483–99. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen LR, Sami S, Vuong N. Lack of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in a large cohort of previously infected persons. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr 2020;109:1088–95. 10.1111/apa.15270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leeb RT, Price S, Sliwa S, et al. COVID-19 trends among school-aged children - United States, March 1-September 19, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1410–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisberg SP, Connors TJ, Zhu Y, et al. Distinct antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in children and adults across the COVID-19 clinical spectrum. Nat Immunol 2021;22:25–31. 10.1038/s41590-020-00826-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tosif S, Neeland MR, Sutton P, et al. Immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in three children of parents with symptomatic COVID-19. Nat Commun 2020;11:5703. 10.1038/s41467-020-19545-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corsini Campioli C, Cano Cevallos E, Assi M, et al. Clinical predictors and timing of cessation of viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol 2020;130:104577. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pang KW, Chee J, Subramaniam S, et al. Frequency and clinical utility of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2020;20:76. 10.1007/s11882-020-00972-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nystad W, Hjellvik V, Larsen IK. Underlying conditions in adults with COVID-19. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2020;140. 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission - United States, march-august 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1695–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woolford SJ, D'Angelo S, Curtis EM, et al. COVID-19 and associations with frailty and multimorbidity: a prospective analysis of UK biobank participants. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:1897–905. 10.1007/s40520-020-01653-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Evidence used to update the list of underlying medical conditions that increase a person’s risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/ [Accessed 10 Dec 2020]. [PubMed]

- 48.Tartof SY, Qian L, Hong V, et al. Obesity and mortality among patients diagnosed with COVID-19: results from an integrated health care organization. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:773–81. 10.7326/M20-3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, et al. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2:782–92. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H. Delirium: a suggestive sign of COVID-19 in dementia. EClinicalMedicine 2020;26:100524. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crabb BT, Lyons A, Bale M, et al. Comparison of international classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision codes with electronic medical records among patients with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2017703. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051707supp001.pdf (821.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Optum but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Optum.