Abstract

Background

Malaria in pregnancy remains a major public health problem in endemic countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Existing interventions such as intermittent preventive therapy in pregnancy (IPTp) using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) are effective against placental malaria. However, low uptake of this intervention is a challenge in SSA. This study assessed factors affecting IPTp-SP uptake among pregnant women as well as their health care providers, including health system-related factors.

Methods

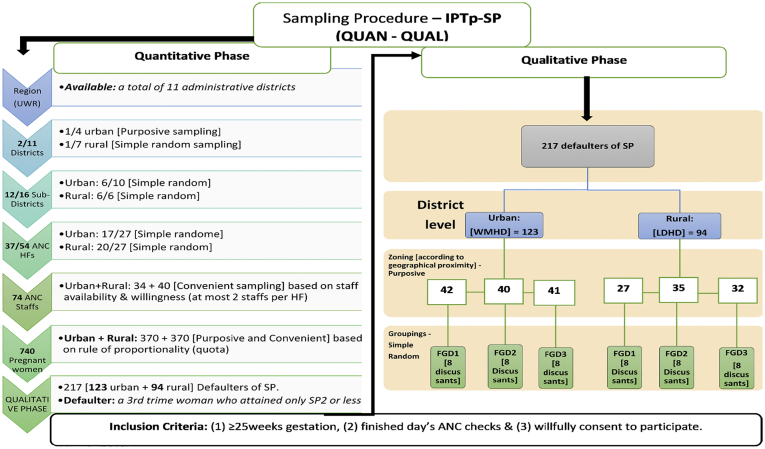

From November 2018 until May 2019 a mixed-methods study was conducted in one urban and one rural district of the Upper West Region of Ghana. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to recruit 740 3rd trimester pregnant women and 74 health service providers from 37 antenatal care (ANC) facilities. Quantitative data was collected through a standard questionnaire from pregnant women and ANC service providers. Three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in each district with pregnant women who had defaulted on their IPTp doses to collect information about the challenges in accessing IPTp-SP. The primary outcome was the uptake of IPTp-SP during antenatal care visits. In addition, the health care provider and health system-related factors on the administration of SP were assessed, as well as details of folic acid (FA) supplementation. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and Poisson regression.

Results

Responses from 697 pregnant women were analysed. Of these, 184 (26.4%) had taken the third dose of SP (SP3) in line with international guidelines. IPTp-SP uptake was low and significantly associated with the number of maternal ANC contacts and their gestational age at 1st ANC contact. Most pregnant women were regularly co-administered SP together with 5 mg of FA, in contrast to the international recommendations of 0.4 mg FA. The main challenges to IPTp-SP uptake were missed ANC contacts, knowledge deficiencies among pregnant women of the importance of IPTp, and frequent drug stock outs, which was confirmed both from the ANC providers as well as from the pregnant women. Further challenges reported were provider negligence/absenteeism, adverse drug reactions, and mobile residency of pregnant women.

Conclusions

The uptake of IPTp-SP in the study area is still very low, which is partly explained by frequent drug stock outs at health facilities, staff absenteeism, knowledge deficiencies among pregnant women, and missed ANC contacts. The high dosing of co-administered FA is against international recommendations. These observations need to be addressed by the national public health authorities.

Keywords: Malaria, Pregnancy, Intermittent-preventive therapy, Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, Mixed-methods, Folic acid

Highlights

-

•

High dose FA co-administered with SP is counterintuitive for malaria endemic areas.

-

•

Discrepancy between international and national IPTp-SP and FA policy is problematic.

-

•

Stock outs of SP in the peripheral health facilities is a major challenge.

-

•

Urban residency can motivate poor uptake of IPTp-SP among pregnant women.

-

•

Mixed-method designs augment reliability of original research findings.

1. Background

Malaria in pregnancy remains a major public health problem in malaria-endemic countries. Each year about 50 million pregnancies are at risk of malaria infection, the majority occurring in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Gosling et al., 2010; Odjidja et al., 2017a).

Intermittent preventive therapy in pregnancy (IPTp) using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) provides between 65% and 85% protection against placental malaria infection (Garner and Gülmezoglu, 2006; Shulman et al., 1999). However, information regarding the global coverage of IPTp-SP in pregnant women is not comprehensive (Onyebuchi et al., 2014). Data from SSA indicate that only about 22% of pregnant women living in endemic areas receive at least two doses of SP during their pregnancy (van Eijk et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2017). A Lancet study reported that 83% of 47 countries studied had adopted and implemented the World Health Organization (WHO) malaria IPT policy. However, only 25% of pregnant women in these countries received at least one dose of treatment (Brieger, 2012; Thiam et al., 2013). Coverage of IPTp was 55% lower than the Abuja 2000 target for 2010 and even worse in high-transmission areas of malaria (Thiam et al., 2013). According to the 2017 World Malaria report, 36 SSA countries adopted the policy, out of which 23 reported a 19% IPTp-SP coverage of at least three doses in 2016 compared to 18% in 2015 and 13% in 2014 (World Health Organization, 2010).

The WHO recommends IPTp-SP to be given at each scheduled ANC contact but only from 16 weeks of gestation onwards when quickening starts, and doses at least spaced one month apart (WHO, 2018a). To access the optimum number of SP doses, a pregnant woman needs to make regular and enough (≥7) ANC contacts because the SP is usually administered at the ANC based on directly observed therapy.

Consequently, the importance of ANC services to safe motherhood cannot be overemphasized: it entails systematic medical assessment of the pregnant woman from conception through to delivery either by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery or via caesarean section (Asah-Opoku et al., 2019). ANC provides preventive and curative health services for the pregnant woman and the fetus through identification and management of risks associated with poor maternal and perinatal outcomes (Cunningham and Gary, 2014). Thus, ANC should ensure a safe outcome of every wanted pregnancy for the baby and for the mother (Mbuagbaw et al., 2014). The main types of antenatal care are the traditional and the focused antenatal care (FANC) (Asah-Opoku et al., 2019). The traditional ANC model is structured into monthly visits for the first six months of gestation, a visit every two to three weeks for the next two months, and then weekly visits thereafter until delivery (Villar et al., 2001). The Ghana Health Service ANC policy originally adopted the WHO's traditional version (Birungi et al., 2006). In 2002 the WHO replaced the traditional ANC with the FANC model, which involves fewer visits. These visits with its targeted interventions are considered sufficient to meet antenatal needs (WHO, 2002). Ghana adopted FANC in 2002 and recommended that the first ANC contact should preferably occur prior to the 16th week of gestation (Asah-Opoku et al., 2019). The second and third contacts should occur between 20 and 24 weeks and 28 to 32 weeks respectively, while the fourth contact at 36 to 40 weeks (Birungi et al., 2006). The WHO recommends to integrate IPTp-SP with FANC in the malaria endemic areas of Africa and to base schedules on the specific situation and the individual assessment of each woman (WHO, 2013). According to a WHO evidence review from 2012, three or more doses of IPTp-SP, compared to only two doses, were found to reduce placental malaria significantly, and such regimens were also associated with a 20% relative risk reduction for low birth weight (LBW) and anaemia in pregnancy (WHO, 2012). However, the cause of anaemia during pregnancy extends beyond malaria in pregnancy.

Beside malaria, there are other parasite infections (e.g. hookworm, schistosomiasis) as well as chronic infections such as tuberculosis (TB) and HIV and haemoglobinopathies that contribute to anaemia in pregnancy (WHO, 2018b). Anaemia is also often associated with iron, folate and vitamin A deficiencies (Getachew et al., 2018; Ba et al., 2019). Anaemia is estimated to affect 38.2% of pregnant women globally, with the highest prevalence in the WHO regions of South-East Asia (48.7%) and SSA (46.3%) (WHO, 2018b). Therefore, iron and folic acid (FA) supplementation in combination with IPTp (in malaria endemic areas) is the main strategy for prevention and control of anaemia in pregnancy and to decrease the risk for neural tube defects (WHO, 2009). The effectiveness of IPTp-SP against malaria anaemia depends on the dose and adherence to iron and FA (WHO, 2009). Meanwhile information on the use of iron and FA supplementation during ANC is either not available (Getachew et al., 2018), or the adherence to it is still low (28.7%) in most of SSA, contributing to avoidable morbidity and mortality (Ba et al., 2019).

Among Ghanaian pregnant women, malaria accounts for 28.1% of out-patient hospital attendance, 13.7% of hospital admissions and 9.0% of maternal deaths (Ghana Health Service, 2015). In 2016, national IPTp-SP uptake in Ghana was 64.1% for SP1, 51.6% for SP2, 36.7% for SP3, 16.7% for SP4, and 6.7% for SP5 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2017). Compared to other regions in Ghana, the Upper West Region (UWR) recorded rather low IPTp-SP uptake rates (Ghana Statistical Service, 2017). This study investigated primarily the factors which influence the uptake of IPTp-SP in the UWR.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area and study period

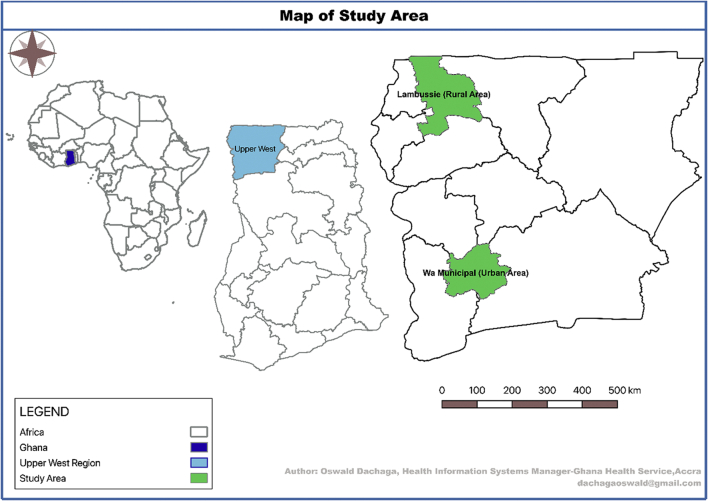

The research was conducted in the UWR, one of the poorest regions in the north-west of Ghana (Fig. 1). Malaria is highly endemic in this area but seasonal, with most transmission occurring from April to November (Nonvignon et al., 2016). The total population of the UWR is about 830,000 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2014). An estimated 47% of the total female population in the region were women in fertility age, with 24,810 expected pregnancies in 2018 (WMHD_GHS, 2017). The study was conducted between November 2018 and May 2019.

Fig. 1.

Map of study area.

2.2. Study scope and design

The study compared 3rd trimester pregnant women in one urban (Wa Municipality) and one rural (Lambussie District) district in the UWR of Ghana. In this study, third trimester ranged from the last week of the second trimester till the end of the pregnancy. The range of ≥25 weeks was considered on the estimation that, a pregnant woman transitioning from week 25 would have received or be due for at least the third dose of SP (SP3) to be a non-defaulter. The sequential explanatory mixed-method model of a quantitative-qualitative design was adopted (Ishtiaq, 2019a).

2.3. Selection of study districts and health facilities

A multi-stage sampling approach was used (Ishtiaq, 2019b). Two of eleven administrative districts in the region – 1 urban (purposive) and 1 rural (simple random) – were selected for comparison (Oduro et al., 2010). The oldest, most populated, and comparatively more resourced of the four urban districts was selected and compared with one of seven rural districts. There were 27 health facilities offering ANC services in the rural district of Lambussie and 27 in the urban district of Wa Municipality. Through a mix of purposive and simple random sampling, we selected 20/27 health facilities (HFs) in Lambussie and 17/27 HFs in Wa Municipality – a total of 37/54 HFs from both districts. The main HF in each sub-district, usually the highest referral center in that district, was automatically included in the sampled HFs; all other HFs were selected through simple random sampling. Prior to the random selection of the HFs, we adopted the simple majority rule of sampling ‘50% + 1’ of all eligible HFs in each sub-district, as used elsewhere (National Archives and Records Administration, 2002). Thus, we sampled at least 50% of the total eligible HFs in each sub-district. The 50% + 1 rule was used because it was not feasible due to time and other resource requirements to cover all HFs in all selected sub-districts. Based on the total number of eligible HFs in each of the six sub-districts, the sum of 50% + 1 of all eligible HFs added up to 20 and 17 HFs for the rural and the urban districts, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of the selected study districts, sub-districts, HFs & ANC Staffs.

| Country: Ghana Region: UWR | Districts selected | Sub-districts selected | ANC HFs available | ANC HFs selected | ANC Staffs at post | ANC Staffs selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana/Upper Wes Region | Wa Municipal (Urban) | Bamahu | 7 | 4 | Specifics could not be accessed but ranged from 1 to 5 each | 8 |

| Busa | 3 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Charia | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Wa North | 6 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Wa South | 5 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Kambali | 4 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Sub-total | 27 | 17 | 34 | |||

| Lambussie District (Rural) | Billaw | 5 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Hamile | 7 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Karne | 4 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Lambussie Main | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Piina | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Samoa | 7 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Sub-total | 27 | 20 | 111a | 40 | ||

| Total | 2/11 | 12/16 | 54 | 37 | 74 |

Means the specific numbers in each sub-district could not be confirmed.

2.4. Sample size calculation

Given the current information on the proportions of SP uptake in the urban and rural districts (26.1% and 17.6%, respectively) (WMHD_GHS, 2017), the sample size was estimated with a two-sample proportions test. A sample size of 740 pregnant women (i.e. 370 for each district) was arrived at, assuming 80% power and 5% alpha (Wang, 2000).

2.5. Survey in pregnant women

The study collected primary data through semi-structured interviews and secondary data through a review of respondents' ANC records. The data included respondents' socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics, their IPTp-SP uptake, and the characteristics of SP and FA co-administration. Inclusion criteria were (1) gestational age ≥ 25 weeks, (2) completion of routine ANC on the day of the interview, and (3) informed written consent. Twelve student nurses (5 in the urban and 7 in the rural study area) were trained to administer the questionnaires. The 12 student nurses were offering voluntary services at various health facilities while waiting to officially assume their role in Ghana Health Service. On the contrary, any pregnant woman who (1) was <25 weeks gestion, (2) was at the facility for any services other than the routine ANC schedule, and (3) objected to consent for the study, was excluded.

2.6. Survey of ANC nurses

All 74 ANC nurses and midwives who participated in this study were chosen by convenience from the 17 urban HFs (n1 = 34) and 20 rural HFs (n2 = 40), of which 64 (n1 + n2 = 28 + 36) were used for the data analysis after data cleaning. Ten staff members were not included, because of missing or incomplete information regarding their professional background. Data on professional characteristics of nurses were collected. In addition, open questions related to the health system related challenges in implementing the IPTp-SP policy and how they manage them were asked. The participating nurses and midwives were recruited and interviewed by the 12 student nurses as research assistants, using a semi-structured questionnaire.

The variables considered included the uptake of IPTp-SP as the outcome variable, measured as a count. The following were considered as the explanatory variables and measured as categorical: marital status, occupation, educational attainment, marital category, ownership of an ITN, and maternal knowledge of malaria in pregnancy. Other explanatory variables which were considered but as count variables included maternal age, average monthly income, gestational age at first ANC, gestational age at interview, parity, household size, and the number of ANC contact.

2.7. Focus group discussions with pregnant women

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were organized according to standard recommendations (Morgan, 1996; Kruger and Casey, 2000) and conducted with defaulters defined as third trimester pregnant women who had only reached SP2 or less. A total of 217 (123 urban, 94 rural) defaulters were identified. Three each FGDs were conducted in both the urban and the rural study district, respectively. Clusters of defaulters were built according to the distance to their health facility. Out of the clusters, participants were randomly chosen (“hat picking”). Eight adult pregnant women above age 18 participated in each of the FGDs.

Data were collected using a FGD guide, an audio recorder, and note pads (Van Eeuwijk and Angehrn, 2017). The FGD guide was validated by pre-testing on a group of selected defaulters for SP in the Wa-Dobile community, which was not part of this study. The FGD guide contained three main themes: (1) participants' basic understanding of malaria and pregnancy; (2) the challenges they encounter in accessing the IPTp-SP intervention; and (3) if they had any suggestion to improve the IPTp-SP intervention. The FGDs were conducted in the local languages (Dagaare/Waale) of the study areas. The sampling procedure is conceptualized in the Annex section of this work (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sampling procedure.

2.8. Data analyses

In 5.8% (43/740) of the interviewed women, data on the outcome of the study were missing and therefore not considered. Quantitative data were compiled and cleaned using SPSS version 20 and analysed using Stata software (version 14.0). First, socio-demographic, obstetric and gynaecological characteristics of pregnant women were described. Second, Poisson regression was used to analyse determinants of SP uptake (number of SP doses taken) by estimating adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR). Possible over dispersion was corrected using Pearson chi-squared. FGD recordings were transcribed into English. Then, content analysis was performed: transcripts were coded manually applying a mix of deductive and inductive coding, applying predefined themes from the questionnaire, and creating new codes as emerging from the transcripts. Synthesis of themes/codes was performed using Microsoft Excel.

2.9. Ethical aspects

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Commissions of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University Hospital in Germany (S-775/2019) and the Navrongo Health Research Center (NHRC) in Ghana (CHRCIRB312). All study participants provided written informed consent. Even though few of our participants were younger than the legal adult age of 18 years, they were not compelled to attend ANC with older relatives or parent but by themselves. Our study, therefore, considered them eligible if they willingly agreed to have understood our protocol and consented to participate.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of pregnant women

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the interviewed pregnant women. The mean age was 27 (range 15–45) years. Most women were Muslims, married, lived in households with 4–6 persons, had low (primary or junior high) education (47.8%), and worked as petty traders (63.4%). Roughly, 90% of pregnant women reported having their own ITN. There were no major differences between the rural and urban study areas.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women.

| Variable | Full sample |

Urban |

Rural |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age groups (in years) | ||||||

| 15–20 | 85 | 12.2 | 36 | 10.2 | 49 | 14.2 |

| 21–25 | 230 | 33.0 | 123 | 34.8 | 107 | 31.1 |

| 26–30 | 188 | 27.0 | 107 | 30.3 | 81 | 23.5 |

| 31–35 | 143 | 20.5 | 66 | 18.7 | 77 | 22.4 |

| 36–40 | 28 | 4.0 | 17 | 4.8 | 11 | 3.2 |

| 41–45 | 23 | 3.3 | 4 | 1.1 | 19 | 5.5 |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Farming | 79 | 11.3 | 7 | 2.0 | 72 | 20.9 |

| Public service | 50 | 7.2 | 35 | 9.9 | 15 | 4.4 |

| Petty trading | 442 | 63.4 | 225 | 63.7 | 217 | 63.1 |

| Unemployed | 126 | 18.1 | 86 | 24.4 | 40 | 11.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 648 | 93 | 340 | 96.3 | 308 | 89.5 |

| Single | 49 | 7.0 | 13 | 3.7 | 36 | 10.5 |

| Religious affiliation | ||||||

| Muslim | 453 | 65.0 | 271 | 76.8 | 182 | 52.9 |

| Christian | 222 | 31.8 | 82 | 23.2 | 140 | 40.7 |

| ATR⁎ | 22 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 6.4 |

| Family category | ||||||

| Polygamy | 195 | 28.0 | 80 | 22.6 | 115 | 33.4 |

| Monogamy | 453 | 65.0 | 260 | 73.7 | 193 | 56.1 |

| Not married | 49 | 7.0 | 13 | 3.7 | 36 | 10.5 |

| Level of formal education | ||||||

| Primary/none | 251 | 36.0 | 107 | 30.3 | 144 | 41.9 |

| Junior high | 82 | 11.8 | 54 | 15.3 | 28 | 8.1 |

| Senior high | 238 | 34.1 | 120 | 34.0 | 118 | 34.3 |

| Tertiary | 126 | 18.1 | 72 | 20.4 | 54 | 15.7 |

| Household size | ||||||

| 1–3 persons | 281 | 40.3 | 149 | 42.2 | 132 | 38.4 |

| 4–6 persons | 303 | 43.5 | 147 | 41.6 | 156 | 45.3 |

| ≥6 persons | 113 | 16.2 | 57 | 16.2 | 56 | 16.3 |

| Own ITN | ||||||

| No | 76 | 10.9 | 46 | 13.0 | 30 | 8.7 |

| Yes | 621 | 89.1 | 307 | 87.0 | 314 | 91.3 |

| Total | 697 | 100 | 353 | 100 | 344 | 100 |

ATR means African Traditional Religion.

Table 2 shows the obstetric and gynaecological characteristics of 3rd trimester pregnant women, including the dosing of IPTp-SP and FA. About three-quarters of the respondents were multigravida (gravida 2 or more), with more multigravida women in the rural compared to the urban area. Roughly, 63% of the pregnant women attended the ANC service for the first time in their second trimester. 58% of pregnancies were within the first five weeks of their 3rd trimester. The mean number of ANC attendances was 4.7 (range 1–8, standard deviation 1.6) and 92% of all ANC contacts were routine contacts. The number of SP doses taken for the current pregnancy ranged from zero to six doses (mean 3.2, standard deviation 1.3). 79% of the pregnant women had received SP combined with FA tablets (74% in the rural and 84% in the urban area). Stockout of SP at the health facilities constituted 26% (16% in the urban, 36% in rural study area) of the reasons why pregnant women missed their SP doses. Another reason was missed ANC contacts as an important factor to poor SP uptake, which dominated in the urban study area.

Table 2.

Obstetric & gynaecological characteristics of 3rd trimester pregnant women, including the dosing of IPTp-SP and FA.

| Variable | Full sample |

Urban |

Rural |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 697 | % | N = 353 | % | N = 344 | % | |

| Gravidity | ||||||

| Gravida 1 | 174 | 24.9 | 108 | 30.6 | 66 | 19.2 |

| Gravida 2 or more | 523 | 75.1 | 245 | 69.4 | 278 | 80.8 |

| Gestational age at first ANC contact | ||||||

| ≤12 weeks | 218 | 31.2 | 100 | 28.3 | 118 | 34.3 |

| >12 to 24 weeks | 436 | 62.6 | 230 | 65.2 | 206 | 59.9 |

| ≥25 weeks | 43 | 6.2 | 23 | 6.5 | 20 | 5.8 |

| Gestational age (on the day of interview) | ||||||

| 25–30 weeks | 405 | 58.1 | 211 | 59.8 | 194 | 56.4 |

| 31–36 weeks | 230 | 33.0 | 113 | 32.0 | 117 | 34.0 |

| 37–42 weeks | 62 | 8.9 | 29 | 8.2 | 33 | 9.6 |

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 183 | 26.2 | 115 | 32.6 | 68 | 19.8 |

| Primiparous | 172 | 24.7 | 104 | 29.5 | 68 | 19.8 |

| Multiparous | 327 | 46.9 | 131 | 37.1 | 196 | 56.9 |

| Grand multiparous (≥5) | 15 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.8 | 12 | 3.5 |

| ANC contacts | ||||||

| 1 | 25 | 3.6 | 12 | 3.4 | 13 | 3.8 |

| 2 | 24 | 3.4 | 13 | 3.7 | 11 | 3.2 |

| 3 | 97 | 13.9 | 58 | 16.4 | 39 | 11.3 |

| 4 | 192 | 27.6 | 93 | 26.4 | 99 | 28.8 |

| 5 | 126 | 18.1 | 66 | 18.7 | 60 | 17.4 |

| 6 | 106 | 15.2 | 58 | 16.4 | 48 | 14.0 |

| 7 | 112 | 16.1 | 48 | 13.6 | 64 | 18.6 |

| 8 | 15 | 2.1 | 5 | 1.4 | 10 | 2.9 |

| Reason for missed SP doses (only those who had ≤SP2) | ||||||

| Missed ANC schedule | 52 | 24.0 | 21 | 17.1 | 30 | 31.9 |

| SP Shortage at facility | 73 | 33.6 | 24 | 19.5 | 47 | 50.0 |

| Others (‘not eaten’, staff absenteeism, sickness) | 92 | 42.4 | 78 | 63.4 | 17 | 18.1 |

| Number of SP doses taken for current pregnancy | ||||||

| None (0) | 9 | 1.3 | 5 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.2 |

| SP1 | 35 | 5.0 | 15 | 4.2 | 20 | 5.8 |

| SP2 | 173 | 24.8 | 103 | 29.2 | 70 | 20.3 |

| SP3 | 184 | 26.5 | 96 | 27.2 | 88 | 25.6 |

| SP4 | 177 | 25.4 | 80 | 22.7 | 97 | 28.2 |

| SP5 | 100 | 14.3 | 47 | 13.3 | 53 | 15.4 |

| SP6 | 19 | 2.7 | 7 | 2.0 | 12 | 3.5 |

| Administered SP & 5 mg Folic Acid (FA) | ||||||

| Yes | 549 | 78.8 | 295 | 83.6 | 254 | 73.8 |

| No | 148a | 21.2 | 58a | 16.4 | 90a | 26.2 |

Indicated that FA was not taken on the day of the ANC contact. There is no scientific evidence of how long apart SP should be withheld if 5 mg FA is given, even though 2 weeks is suggested (WHO, 2014).

3.2. Characteristics of ANC nurses and midwives

Information on the professional background and service-related challenges of the 64 ANC nurses interviewed is provided in Table 3. The majority were either trained as community health nurses or as midwives. Roughly three quarters of the nurses in the urban area had provided ANC services for four years at most as compared to 86% of the nurses in the rural area. 88% of the nurses had experienced stock outs of SP every other week or at least monthly (about 90% across urban and rural area). 18% had experienced stock outs even on a daily or weekly basis. Nurses also reported that it usually takes longer than one week to restock the SP. Some of the staffs indicate that the FA usually comes already packaged in 5 mg blisters. In the urban area, 62% of the nearest referral facilities were within 5 km distance. In contrast, in the rural area the majority of the referral facilities were more than 15 km away.

Table 3.

Professional background and service-related characteristics of ANC nurses.

| Parameter | Full sample N = 64(%N) | Urban N = 26(%N) | Rural N = 38(%N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional background per training | |||

| Midwife | 27(42.2) | 14(53.9) | 13(34.2) |

| Community Health Nurse (CHN) | 27(42.2) | 7(26.9) | 20 (52.6) |

| Other | 10(15.6) | 5(19.2) | 5(13.2) |

| Any midwifery related training on the job (Yes/No) | 23(35.9)/41(64.1) | 10(38.5)/16(61.5) | 13(34.2)/25(65.8) |

| Years of work on this role (ANC) | |||

| ≤2 yrs | 28(43.8) | 9(34.6) | 19(50.0) |

| ≤4 yrs | 25(39.0) | 11(42.3) | 14(36.8) |

| ≥5 yrs | 11(17.2) | 6(23.1) | 5(13.2) |

| Distance to the nearest referral facility | |||

| ≤5 Km | 19(29.7) | 16(61.5) | 2(5.3) |

| 6 Km–10 Km | 9(14.1) | 2(7.7) | 6(15.8) |

| 11 Km–15 Km | 10(15.6) | 4(15.4) | 7(18.4) |

| ≥15 Km (−45 Km) | 26(40.6) | 4(15.4) | 23(60.5) |

| Have experienced SP stock out (Yes/No) | 56(87.5)/8(12.5) | 23(88.5)/3(11.5) | 33(86.8)/5(13.2) |

| Frequency of stock out | N = 56 | N = 23 | N = 33 |

| Daily | 4(7.1) | 1(4.3) | 3(9.1) |

| Weekly | 6(10.8) | 5(21.7) | 1(3.0) |

| Other (every other week or more) | 46(82.1) | 17(73.9) | 29(87.9) |

3.3. Determinants of SP uptake among pregnant women

Table 4 presents the results of the Poisson model on the SP uptake as the outcome variable among pregnant women. The number of maternal ANC contacts (IRR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.221–1.299) and their gestational age at 1st ANC (IRR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.623–1.127) were significantly associated with SP uptake as expected. This means that pregnant women who registered for ANC early enough (within the first trimester of pregnancy) were much more likely to receive optimum SP doses compared to late registrants.

Table 4.

Poisson regression of determinants of SP uptake in pregnant women of northern Ghana.

| SP uptake | IRR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age(years) | 1.000 | 0.993 | 1.008 | 0.931 |

| Marital status | 0.502 | |||

| Married | ref | |||

| Not married | 1.067 | 0.883 | 1.289 | |

| Occupation | 0.932 | |||

| Farming | ref | |||

| Public/civil service | 1.027 | 0.816 | 1.293 | |

| Private/personal business | 0.977 | 0.833 | 1.146 | |

| Unemployed | 0.970 | 0.802 | 1.173 | |

| Formal education | 0.928 | |||

| Any | ref | |||

| None | 1.004 | 0.911 | 1.107 | |

| Income | 0.910 | |||

| Below minimum wage (≤ 299) | ref | |||

| On minimum wage (300 to 599) | 0.974 | 0.811 | 1.169 | |

| Above minimum wage (≥ 600–1800) | 0.956 | 0.743 | 1.23 | |

| Gestational age at 1st ANC | 0.006 | |||

| ≤12 weeks | ref | |||

| >12 to 24 weeks | 1.132 | 1.023 | 1.253 | |

| ≥25 weeks | 0.838 | 0.623 | 1.127 | |

| Parity | 0.329 | |||

| Nulliparous | ref | |||

| Primiparous | 1.084 | 0.961 | 1.222 | |

| Multiparous (2–3) | 1.017 | 0.901 | 1.149 | |

| Grand multiparous (4–8) | 1.145 | 0.938 | 1.399 | |

| Household size (1 to 12) | 0.994 | 0.973 | 1.017 | 0.614 |

| Own ITN | 0.659 | |||

| No | ref | |||

| Yes | 1.033 | 0.896 | 1.195 | |

| Knowledge score (1 to 7) | 1.002 | 0.965 | 1.04 | 0.935 |

| ANC contacts (1 to 8) | 1.255 | 1.212 | 1.299 | <0.001 |

| District | 0.892 | |||

| Urban area (WMHD) | ref | |||

| Rural area (LDHD) | 1.006 | 0.917 | 1.104 | |

Knowlegde_MiP = knowledge of risks of malaria in pregnancy IRR = Incidence risks ratio.

3.4. Pregnant women's knowledge about malaria in pregnancy

The responses from the six FGDs were categorized according to the themes as shown in Table 5 in the Annex. Defaulting pregnant women had fair knowledge regarding the cause of malaria and measures to prevent mosquito bites: answers generally contained phrases such as ‘…through mosquito bites’, ‘…by a mosquito’, ‘if I get malaria, it can affect my baby because the baby is inside me’. However, on few instances, responses such as ‘it is caused by the food we eat’, ‘through cold food’, ‘through dirty water or dirty environment’, also indicate that there is a measure of poor knowledge about the cause of malaria among defaulting pregnant women.

Table 5.

Qualitative findings from FGDs in urban (WMHD) and rural (LDHD) districts (April–May 2019).

| Theme | Sub-code | Verbatim quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Good knowledge | “If I get malaria, it [malaria] can affect my baby in the womb because the baby [fetus] is exposed to any sickness I get. So, we should worry because of the child in the womb” (Participant, FGD3_LDHD) |

| “Some of us either sleep under the mosquito net or spray the rooms to prevent mosquitoes. Some of us also cover ourselves with clothes to prevent mosquito bites or use the mosquito coils…” (Participant, FGD2_WMHD) | ||

| Poor knowledge | “Malaria is caused by the kind of food we eat, or living in [an] environment in which there is filth or dirty water” (Participant, FGD1 LDHD) | |

| Sometimes too eating cold food can cause malaria: so, we are always told not to be eating very cold foods during pregnancy” (Participant, FGD2_WMHD) | ||

| “For me, I think it is because of ignorance of some of us. If the nurses talk to us, some will change but not all because others will not take it anyway” (Participant, FGD2_LDHD). | ||

| Challenges in accessing IPTp-SP | Provider negligence | “Sometimes it is from the nurses! Since I have been going to the facility, it is only once they [nurses] gave it [SP] to me. Meanwhile I am almost due to give birth. They did not tell me to take it or not, I didn't also remind them.” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD). |

| “For me, I do not feel anything bad when I take it. I feel completely ok with it, because of that, I always remind the nurses anytime they forget to give me. The last time, I kept reminding them that I have not taken my second dose until they gave me” (Participant, FGD3_WMHD). | ||

| “If the nurses can always be present to attend to us, it will be good. At times, we struggle in the hot sun to come here on foot, but we do not meet any nurse to talk to us. If I do not have any coin to buy drinking water… I will intentionally forget the next visit” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD). | ||

| SP stockout | “Sometimes too when we struggle to come here [health facility], they [nurses] say the medicine [SP drug] is finished, so you should return the next week or sometimes too they write for you to go and buy. Do you know how I come here or if I have the money to buy it or not?” (Participant, FGD2_WMHD) | |

| Change of residence | “For me, the only reason why I skipped was because I was away. I got pregnant in Niger and came back here to Ghana, so the change of environment distracted the dosage in-take” (Participant, FGD2_WMHD). | |

| Adverse drug reaction | “It [SP] disturbs my body and makes me either shiver or vomit. Anytime I take it I feel that my body is shaking” (Participant, FGD3_LDHD) | |

| “It [SP] also makes you feel like you have malaria, but when you complain the nurses still encourage you to take it [SP]. They [health providers] say though it gives symptoms like malaria, it also prevents malaria” (Participant, FGD3_LDHD) | ||

| Improving uptake to IPTp-SP | Health education | “When you know the benefits, you will sacrifice whatever it takes for the goodness of your unborn child…. Who doesn't want comfort?” (Participant, FGD1_WMHD). |

| Encouragement | “For me, I think the nurses should always insist we take it. The last time I went to the facility, they stood on me until I swallowed it [the SP]; I had to buy water that day when I told them I didn't have water” (Participant, FGD3_LDHD) | |

| “They should always insist that we take [the drug] at the facility. The way it [SP] disturbs when you take it, it is not easy, because of that it is good they insist that we take it” (Participant, FGD1_WMHD). | ||

| Improve monitoring and evaluation | “The nurses should make sure the SP drug is always available. They should also prescribe it for us to buy it in case it is not available at the facility.” (Participant, FGD1_WMHD). | |

| “…I am not a nurse, but I believe that what we go through at ‘Nogyug’ hospital [name changed for privacy reasons] when we go for the ultrasound scan is not right: nothing there is covered by the [health] insurance. Aside that, at the ANC they [nurses] usually sell to us a little container [disposable specimen tube] to bring our urine for testing. Instead of letting us dispose the container with the urine afterwards, they ask every one of us [pregnant women] to drop the container into a basin of soapy water. A nurse then wears hand gloves and washes the containers and re-sell them to other pregnant women the following day, meanwhile they have collected our monies meant for drinking water. I have complained severally but no one supports me.” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD). | ||

| Individual circumstance | “Sometimes too it is because you have not eaten anything. So, we feel reluctant in such occasions because you may feel weaker and uncomfortable taking it in a hungry stomach” (Participant, FGD1_WMHD) | |

| “It is better to always take it [SP] home. Else, some of us cannot swallow drugs without putting it in the TZ [a local meal of cereal flour]; we cannot swallow it with water. So, it is difficult for us whenever we are asked to take it and swallow immediately” (Participant, FGD2_LDHD) |

3.5. Challenges in accessing and adhering to IPTp-SP

Under the theme ‘challenges in accessing IPTp-SP’, frequent shortage of SP was mentioned. Many women were told they need to buy the drugs from the private market or return on a scheduled date to receive it. A mother's response summarizes this challenge:

“Sometimes too when we struggle to come here [health facility], they [nurses] will check you alright but say the medicine [SP drug] is finished, so you should return the next week or sometimes too they write for you to go and buy. Do you know how I come here or if I have the money to buy it [the SP drug] or not?” (Participant, FGD2_WMHD).

Participants also mentioned discomfort (nausea, vomiting, weakness…) as signs of adverse drug reactions) as their reason for defaulting. Other reason for poor uptake to IPT-SP was ‘negligence by the service provider’ supported by comments like ‘service provider absenteeism’, or ‘their poor knowledge of the importance of SP’. Participants also complained that their men do not join them on ANC days to be informed about the cost of services and other expectations:

“You also see something, hmmm… our husbands too, ehmm… our husbands don't believe us when we pass messages to them at home; so, if usually they are involved with for the ANC, it would be easier for them understand and support us better” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD).

In the rural district, FGD participants also reported ‘mistreatments’ and ‘extortions’ they encountered at a facility where they need to go for ultrasound scans, and other blood tests at least once during their pregnancy. This is reflected in a mother's quote on the quality of services she received (like reused urine containers) and extra costs of services at a facility:

“…I am not a nurse, but I believe that what we go through at ‘Nogyug’ hospital [name changed for privacy reasons] when we go for the ultrasound scan is not right: at the ANC they [nurses] usually sell to us a little container [disposable specimen tube] to put our urine for testing. Instead of letting us dispose the container with the urine afterwards, they ask every one of us [pregnant women] to drop the container into a basin of soapy water. A nurse then wears hand gloves and washes the containers; they then re-sell the same containers to other pregnant women the following day. Meanwhile they have collected our monies meant for drinking water. I have complained severally but no one supports me. If this practice can be checked, it will encourage some of us to attend ANC there regularly.” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD).

“We also pay for everything; even though my insurance [referring to public health insurance] is active. You need about 115 cedis [$19.8] every time you go for scan, and sometimes you must sleep overnight to get your results before you come home; and it is not only once you have to go there before you deliver. Where should that money come from?” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD).

The complaint of poor quality and cost of service appeared as a shared experience among the participants in this focus group as they unanimously confirmed their colleague's concern loudly, followed with what seemed like a competition to each narrate their ordeal at this facility. Participants also revealed their frustration with staff absenteeism coupled with the fact that they, as direct beneficiaries, do not know the significance of the IPTp-SP. These were captured in mothers' comments as presented in the following quotes:

“If you people [referring to FGD moderators] can also make sure that the nurses are always present every time to attend to us, it will be really good. There are times some of us will stop our work at home and struggle in the hot sun to come here on foot, but we do not meet any nurse to talk to us. If I do not even have any coin to buy water to drink, will I come again the next time? I will intentionally forget” (Participant, FGD1_LDHD).

“When you know the benefits, you will sacrifice whatever it takes for the goodness of your unborn child, but when you do not know, then you won't. Who doesn't want comfort?” (Participant, FGD1_WMHD).

4. Discussion

Pregnant women are the most at-risk adult population for malaria, which justifies IPTp administration (Population Reference Bureau, 2001; WHO, 2017). WHO recommendations call for at least three doses of IPTp-SP to be given to women in the malaria endemic areas of SSA during pregnancy, but overall uptake remains low (WHO, 2018c). In 2016, SP3 was been achieved by only one-fifth of eligible African pregnant women (World Health Organization, 2018). The main finding from our study points to this also being the case in northern Ghana, as only 26.4% of the pregnant women had received SP3. This coverage is even much lower compared to the findings from another study conducted in northern Ghana (Anto et al., 2019). The uptake level of SP3 in our study population is also much lower than the 60% national average of SP3 in Ghana (Yaya et al., 2018). Factors identified in our study which affected SP uptake were frequent stock outs of SP in the local health facilities, poor maternal knowledge of the importance of the IPTp intervention, missed ANC contacts, and staff absenteeism. These data support similar observations from other countries in (Rassi et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2013). A potentially effective intervention to increase IPTp coverage could be the involvement of community health workers, as recently shown in a cluster randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso (Gutman et al., 2020).

Maternal commitment to the uptake of IPTp-SP plus the right dose of FA throughout pregnancy in malaria endemic areas has a double benefit for pregnant women and their new-borns: it reduces maternal and fetal anaemia, low birth weight and neonatal mortality through the reduction in maternal malaria episodes and placental malaria parasitaemia by 65 to 85% (Shulman et al., 1999; Population Reference Bureau, 2001). Another important finding from this study was the fact, that IPTp-SP was frequently co-administered by a high dose (5 mg) of FA, which is clearly against the national and international policy recommendations to only provide 0.4 mg FA (Ghana Health Service, 2016; National Malaria Control Programme, 2016). FA at a daily dose equal to or above 5 mg should not be given together with SP in malaria endemic areas as this reduces the antimalarial efficacy of SP and is considered as an independent risk factor for SP treatment failure (WHO, 2018a; WHO, 2013; Ghana Health Service, 2016; Carter et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2007). 5 mg of FA per day is only recommended for peri-conceptional supplementation in women who had a previous pregnancy with a child with a neural tube defect (NTD) (De-Regil et al., 2015). A review about the availability of 0.4 mg FA on the Ghana national emergency medicine lists revealed that FA at a dose of 0.4 mg is only available in combination with iron. In addition, the price for this combination (0.41 GHC) is much higher than the price for 5 mg FA tablets (0.02 GHC) or 60 mg ferrous sulphate tablet (0.05 GHC) in Ghana (National Health Insurance Scheme, 2020). Currently there is no scientific consensus, whether high doses of FA should be withheld (and for how long) following the dose of SP in malaria endemic areas where only high-dose FA is available (WHO, 2018b). It is a general policy that pregnant women are administered the SP therapy, unlike the FA, as directly observed therapy (DOT) at the ANC consultation. The FA, however, is prescribed to be taken daily, self-administered at home, until the next ANC contact (WHO, 2018b). This has also been discussed in the 2016 desk review report on barriers of IPTp-SP uptake in Ghana (GHS-NMCP, 2016). One more problem could be that according to WHO, in areas where the prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy is higher than 20%, a high dose of 5 mg FA is still recommended (Ba et al., 2019; WHO, 2009). However, this contradicts the IPTp-SP recommendation of 0.4 mg FA daily (WHO, 2013; WHO, 2018b; Peters et al., 2007). Meanwhile, the scientific community currently has no agreement on how long is an appropriate timing between SP and administering FA of 5 mg or more (WHO, 2014). The current practice in many countries is two weeks following administration of 5 mg FA, and even that is considered by expert opinion to be too short between treatments (WHO, 2014). There is clearly a need for making pre-packaged combinations of SP plus low-dose FA more accessible in SSA.

Our data demonstrated that pregnant women with more ANC contacts are more likely to get their SP compared to those with fewer ANC contacts. This has also been shown by (Chepkemoi Ng’etich Mutulei, 2013) and is not surprising because SP is administered only at the ANC as DOT. Moreover, pregnant women whose gestational ages at first ANC were within the first trimester had received significantly more SP doses compared to those who started ANC contacts later, again supporting findings from other studies (Anto et al., 2019; Azizi, 2020). According to the ANC nurses interviewed in our study, the biggest challenges for IPTp-SP uptake were the frequent SP stock outs and significant delays in restocking; this is also reported elsewhere (Muhumuza et al., 2016; Ameh et al., 2016). This finding was confirmed by many of the pregnant women in the FGDs.

Data from the qualitative phase of this study also reveal that lack of spousal support is one hindrance to early and regular ANC attendance. Considering that the socio-cultural environment of the study is patriarchal in nature, most women depend on their husbands for financial and other social support to make the most of their health decisions. This finding is similar to reports of lack of decision-making autonomy among women in other areas (Sumankuuro et al., 2019; Ampim, 2013). The non-involvement of men in the ANC activities of the pregnant women thus hamper smooth communication and understanding, often resulting in less ANC attendance and less SP uptake. Other challenges for IPTp-SP uptake identified from the FGDs included staff absenteeism, especially in the rural area as recorded elsewhere (Odjidja et al., 2017b; Arnaldo et al., 2019). The factor of staff absenteeism in this study could be due to work fatigue, especially in the rural areas where due to less capacity and long distance to the facility, providers are often few and hardly run shifts.

As further revealed in the findings of this study, stock outs of freely supplied essential medicines such as SP in peripheral health facilities appears to be a persistent problem across many malaria endemic countries in SSA (Marchant et al., 2008; Kanté et al., 2014; Arnaldo et al., 2019; Amankwah and Anto, 2019; Bajaria et al., 2019). Identified health system challenges associated with stock outs of essential drugs in Ghana were a limited local pharmaceutical capacity, grossly underfunding by international donors, as well as the bureaucratic demands on importing drugs (Odjidja et al., 2017a). However, it has also been observed that SP stock out is frequently due to its non-recommended use as a monotherapy in clinical malaria cases (WHO, 2013).

4.1. Limitations of the study

The study is limited in the context of its scope of audience: it covered pregnant women rather than post-natal women as has been done by other studies. Moreover, the study reports only data from the Upper West Region and may thus not be representative of the whole of Ghana.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the uptake of IPTp-SP in the study area is still very low. The major factors for the low uptake include frequent drug stock outs at health facilities, knowledge deficiency among pregnant women of the importance of IPTp, and missed ANC contacts. The discrepancy between international and national recommendations for IPTp-SP and FA is another important finding of this study. These observations need to be addressed by the national public health authorities.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to publish this paper.

Availability of data and materials

All data are made available to the readers.

Funding

Funding for this study was received through a scholarship from the Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer-Dienst (KAAD).

Authors' contributions

FD conceived and discussed the study idea with OM. FD, OM, PM, CB, VW, and NK structured the study design into context. FD, OM, PM, and JA oversaw the field implementation of the study. FD, VW, NK, JA, and CB conducted the data analyses while FD, JA, NK, and PM drafted the manuscript. All authors read, commented, and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the funding of KAAD, the time and information from our study participants and field assistants, the support from the Ghana Health Service at the Region and selected district health directorates of the study, Mr. Oswald Dachaga who produced the map of the study area with his GIS expertise, and the insightful contributions from the Bergheim Working Group at the HIGH in Germany.

Contributor Information

Frederick Dun-Dery, Email: kuanufred@gmail.com, frederick.dundery@uni-heidelberg.de.

Peter Meissner, Email: meissnerulm@gmail.com.

Claudia Beiersmann, Email: beiersmann@uni-heidelberg.de.

Naasegnibe Kuunibe, Email: nkuunibe@uds.edu.gh.

Volker Winkler, Email: volker.winkler@uni-heidelberg.de.

Jahn Albrecht, Email: albrecht.jahn@uni-heidelberg.de.

Olaf Müller, Email: olaf.mueller@urz.uni-heidelberg.de.

References

- Amankwah S., Anto F. Factors associated with uptake of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in private health facilities in Tema Metropolis, Ghana. J. Trop. Med. Aug. 2019;2019:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2019/9278432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameh S. Barriers to and determinants of the use of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in Cross River State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. Dec. 2016;16(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0883-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampim G.A. Universitas Bergensis; 2013. Men’s Involvement in Maternal Healthcare in Accra, Ghana. From Household to Delivery Room. [Google Scholar]

- Anto F., Agongo I.H., Asoala V., Awini E., Oduro A.R. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: assessment of the sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine three-dose policy on birth outcomes in rural northern Ghana. J. Trop. Med. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/6712685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldo P. Access to and use of preventive intermittent treatment for Malaria during pregnancy: a qualitative study in the Chókwè district, Southern Mozambique. PLoS One. Jan. 2019;14(1):e0203740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asah-Opoku K. Adherence to the recommended timing of focused antenatal care in Accra, Ghana. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019;33:1–15. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.33.123.15535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi S.C. Uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria during pregnancy with Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine in Malawi after adoption of updated World Health Organization policy: an analysis of demographic and health survey 2015–2016. BMC Public Health. Dec. 2020;20(1):335. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08471-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba D.M. Adherence to Iron supplementation in 22 sub-Saharan African countries and associated factors among pregnant women: a large population-based study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. Dec. 2019;3(12):1–8. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaria S., Festo C., Mrema S., Shabani J., Hertzmark E., Abdul R. Assessment of the impact of availability and readiness of malaria services on uptake of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) provided during ANC visits in Tanzania. Malar. J. Dec. 2019;18(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2862-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birungi H. 2006. Acceptability and feasibility of introducing the WHO focused antenatal care package in Ghana. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brieger W. Control of malaria in pregnancy: an elusive target. Afr. Health. 2012;34(January 2012):15–18. http://www.africa-health.com/articles/january_2012/Malaria.pdf [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- Carter J.Y., Loolpapit M.P., Lema O.E., Tome J.L., Nagelkerke N.J.D., Watkins W.M. Reduction of the efficacy of antifolate antimalarial therapy by folic acid supplementation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;73(1):166–170. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepkemoi Ng’etich Mutulei A. Factors influencing the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy: evidence from Bungoma East District, Kenya. Am. J. Public Heal. Res. May 2013;1(5):110–123. doi: 10.12691/ajphr-1-5-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham . In: Williams: obstetrica (23a. ed.) 24th ed. Gary F., editor. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2014. Williams Obstetrics 24/E; pp. 21–35. no. May. [Google Scholar]

- De-Regil L.M., Peña-Rosas J.P., Fernández-Gaxiola A.C., Rayco-Solon P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. Dec. 2015;14(January) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007950.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner P., Gülmezoglu A.M. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getachew M., Abay M., Zelalem H., Gebremedhin T., Grum T., Bayray A. Magnitude and factors associated with adherence to Iron-folic acid supplementation among pregnant women in Eritrean refugee camps, northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. Dec. 2018;18(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1716-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Health Service The Health System in Ghana, facts and Figures. 2015. http://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Facts-and-figures-2015.pdf Accra, Ghana. [Online]. Available: internal-pdf://0240438844/Facts-and-figures-2015_GHS.pdf.

- Ghana Health Service National Malaria Control Program. 2016. http://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/2016-Annual_Bulletin.pdf Accra, Ghana. Accessed: Dec. 06, 2017. [Online]. Available.

- Ghana Statistical Service 2010 Population & Housing Census: Lawra District Analytical Report. Oct. 2014. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010_District_Report/Upper West/LAWRA.pdf Accra, Ghana. Accessed: Dec. 21, 2015. [Online]. Available.

- Ghana Statistical Service Key Malaria indicators from the 2016 Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey. 2017. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/publications/Ghana MIS 2016 KIR - 06March2017.pdf Accra, Ghana. Accessed: Dec. 04, 2017. [Online]. Available.

- GHS-NMCP Ghana Malaria Control Programme Periodic Bulletin. 2016. http://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/2016-Annual_Bulletin.pdf Accra, Ghana. Accessed: Dec. 04, 2017. [Online]. Available.

- Gosling R.D., Cairns M.E., Chico R.M., Chandramohan D. Intermittent preventive treatment against malaria: an update. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2010;8(5):589–606. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman J.R. A cluster randomized trial of delivery of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy at the community level in Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 2020;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. Factors affecting the delivery, access, and use of interventions to prevent malaria in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishtiaq M. Book Review Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. English Lang. Teach. 2019;12(5):40. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n5p40. Apr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishtiaq M. Book Review Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. English Lang. Teach. 2019;12(5):40. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n5p40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanté A.M. The contribution of reduction in malaria as a cause of rapid decline of under-five mortality: evidence from the Rufiji Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in rural Tanzania. Malar. J. Dec. 2014;13(1):180. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger A.R., Casey M.A. 3rd ed. Sage Publications, Inc; Califonia: Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant T. Individual, facility and policy level influences on national coverage estimates for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in Tanzania. Malar. J. Dec. 2008;7(1):260. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw L., Habiba Garga K., Ongolo-Zogo P. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Mbuagbaw L., editor. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2014. Health system and community level interventions for improving antenatal care coverage and health outcomes. vol. 2014, no. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L.D. Focus groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996;22:129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhumuza E., Namuhani N., Balugaba B.E., Namata J., Kiracho E.E. Factors associated with use of malaria control interventions by pregnant women in Buwunga subcounty, Bugiri District. Malar. J. 2016;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1407-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Archives and Records Administration . In: Food and Drugs: 21 CFR 800.10. 4th–1st–02. Mosley R.A., editor. Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration; Washington DC: 2002. Code of federal regulations: containing a codification of documents of general applicability and future effect; p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Insurance Scheme . Accra; Ghana: 2020. National Health Insurance Scheme Medicines List for Level ‘ c ’ Facilities (District Hospital) [Google Scholar]

- National Malaria Control Programme . Ghana Health Service; Accra, Ghana: 2016. Malaria 1ST quarter bulletin - 2016: national malaria control surveillance bulletin – issue 5.http://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/1st Quarter Malaria Bulletin - 2016_14th July 2016.pdf Issue-5. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2016. [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- Nonvignon J. Cost-effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention in upper west region of Ghana. Malar. J. Dec. 2016;15(1):367. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1418-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odjidja E.N., Kwanin C., Saha M. Low uptake of intermittent preventive treatment in Ghana; an examination of health system bottlenecks. Heal. Syst. Policy Res. 2017;4(3) doi: 10.21767/2254-9137.100079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odjidja E.N., Kwanin C., Saha M. Low uptake of intermittent preventive treatment in Ghana; an examination of health system bottlenecks. Heal. Syst. Policy Res. 2017;4(3):58. 10.21767/2254-9137.100079 Sep. [Google Scholar]

- Oduro A.R. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine-based intermittent preventive treatment, bed net use, and antenatal care during pregnancy: demographic trends and impact on the health of newborns in the Kassena Nankana District, northeastern Ghana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. Jul. 2010;83(1):79–89. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyebuchi A.K., Lawani L.O., Iyoke C.A., Onoh C.R., Okeke N.E. Adherence to intermittent preventive treatment for malaria with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and outcome of pregnancy among parturients in South East Nigeria. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2014;8:447–452. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S61448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters P.J., Thigpen M.C., Parise M.E., Newman R.D. Safety and toxicity of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine: implications for malaria prevention in pregnancy using intermittent preventive treatment. Drug Saf. 2007;30(6):481–501. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau . Population Reference Bureau; Washington DC: 2001. Malaria Continues to Threaten Pregnant Women and Children.https://www.prb.org/malariacontinuestothreatenpregnantwomenandchildren/# [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- Rassi C., Graham K., King R., Ssekitooleko J., Mufubenga P., Gudoi S.S. Assessing demand-side barriers to uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy: a qualitative study in two regions of Uganda. Malar. J. 2016;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1589-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman C.E. Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) Feb. 1999;353(9153):632–636. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumankuuro J., Mahama M.Y., Crockett J., Wang S., Young J. Narratives on why pregnant women delay seeking maternal health care during delivery and obstetric complications in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. Dec. 2019;19(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2414-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiam S., Kimotho V., Gatonga P. Why are IPTp coverage targets so elusive in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review of health system barriers. Malar. J. 2013;12 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eeuwijk P., Angehrn Z. How to Conduct a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) Methodological Manual. 2017. https://www.swisstph.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/SwissTPH/Topics/Society_and_Health/Focus_Group_Discussion_Manual_van_Eeuwijk_Angehrn_Swiss_TPH_2017_2.pdf Basel. [Online]. Available:

- van Eijk A.M. Coverage of intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide-treated nets for the control of malaria during pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis and meta-analysis of national survey data, 2009-11. Lancet Infect. Dis. Dec. 2013;13(12):1029–1042. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J. WHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet. May 2001;357(9268):1551–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04722-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker P.G.T., Floyd J., ter Kuile F., Cairns M. Estimated impact on birth weight of scaling up intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy given sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in Africa: a mathematical model. PLOS Med. Feb. 2017;14(2):e1002243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Confidence intervals for the ratio of two binomial proportions by Koopman's method. Stata Technical Bulletin 58: 16–19. Reprinted in Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints. 2000. http://www.stata-press.com/data/r13/auto [Online]. Available:

- WHO . WHO/RHR/01.30; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. WHO Programm to Map Best reproductive Health Practices.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42513/WHO_RHR_01.30.pdf [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Weekly iron-folic acid supplementation (WIFS) in women of reproductive age: its role in promoting optimal maternal and child health the who global expert consultation weekly iron and folic acid supplementation consultation recommendations. 2009. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/89743/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_09.2_eng.pdf [Online]. Available. [PubMed]

- WHO WHO Evidence Review Group: Intermittent Preventive Treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) with Sulfadoxine - Pyrimethamine (SP) 2012. http://www.who.int/malaria/mpac/sep2012/iptp_sp_erg_meeting_report_july2012.pdf?ua=1 [Online]. Available.

- WHO . WHO/HTM/GMP/2014.4; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP)http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/iptp-sp-updated-policy-brief-24jan2014.pdf Accessed: Jan. 28, 2018. [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- WHO WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) 2014. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/iptp-sp-updated-policy-brief-24jan2014.pdf Accessed: Dec. 09, 2017. [Online]. Available.

- WHO . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. Malaria in pregnant women.https://www.who.int/malaria/areas/high_risk_groups/pregnancy/en/ [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2018. Implementing malaria in pregnancy programs in the context of World Health Organization recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO Reprod. Heal. Libr., no. March. 2018. WHO recommendation on daily oral iron and folic acid supplementation | RHL; pp. 1–8.https://extranet.who.int/rhl/topics/preconception-pregnancy-childbirth-and-postpartum-care/antenatal-care/who-recommendation-daily-oral-iron-and-folic-acid-supplementation [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- WHO World Malaria Report 2018. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275867/9789241565653-eng.pdf Geneva, Nov.. [Online]. Available.

- WMHD_GHS . Wa Municipality; 2017. Antenatal Care Register: 2015–2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO/HTM/GM, no. December. 2017th ed. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. World Malaria Report. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Malaria Policy Advisory Committee Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland. 2018. 10+1 Approach- An intensified effort to reduce malaria cases and deaths Getting back on track to achieve the morbidity and.https://www.who.int/malaria/mpac/mpac-october2018-session5-10plus1-approach.pdf [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- Yaya S., Uthman O.A., Amouzou A., Bishwajit G. Use of intermittent preventive treatment among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from malaria indicator surveys. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018;3(1) doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are made available to the readers.