Abstract

Daidzein has been found to significantly inhibit the proliferation of lung cancer cells, while its potential molecular mechanisms remain unclear. To determine the molecular mechanism of daidzein on lung cancer cells, the Capital Bio Technology Human long non-coding (lnc) RNA Array v4, 4×180K chip was used to detect the gene expression profiles of 40,000 lncRNAs and 34,000 mRNAs in a human cancer cell line. Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR analysis was performed to detect the expression levels of target lncRNA and mRNAs in the H1299 cells treated with and without daidzein, using the lncRNA and mRNA gene chip. Bioinformatics analysis was performed to determine the differentially expressed genes from the results of the chip assays. There were 119 and 40 differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs, respectively, that had a 2-fold change in expression level. A total of eight lncRNAs were upregulated in the H1299 lung cancer cells, while 111 lncRNAs were downregulated. Furthermore, five mRNAs were upregulated, and 35 mRNAs were downregulated. A total of six differentially expressed lncRNAs (ENST00000608897.1, ENST00000444196.1, ENST00000608741.1, XR_242163.1, ENST00000505196.1 and ENST00000498032.1) were randomly selected to validate the microarray data, which were consistent with the RT-qPCR analysis results. Differentially expressed mRNAs were enriched in important Gene Ontology terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. Taken together, the results of the present study demonstrated that daidzein affected the expression level of lncRNAs in lung cancer cells, suggesting that daidzein may have potential effects on lung cancer cells.

Keywords: daidzein, long non-coding RNA, microarray analysis, NSCLC, differential expression

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies, that threatens the health and life of those affected. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality in both men and women; it is estimated that there were 2.1 million new diagnosed cases and 1.8 million mortalities in 2018 worldwide (1,2). Lung cancer is classified into two major pathohistological subtypes, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (3). NSCLC accounts >85% of all cases of lung cancer (4). Despite major advancements in diagnosis and treatment, the incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer has remained high in recent years (5). Thus, it remains critical to identify and develop potential therapeutic targets in the hope of decreasing the risk of lung cancer.

A previous study demonstrated that consumption of legumes decreased the risk of lung cancer by 23% (6). Isoflavones, coumarins and lignin were reported to be the three main phytochemicals in soybeans (7). Currently, there is a focus on the potential health benefits of isoflavones, including genistein and daidzein. The effect of soybeans and their ingredients on tumors has become a hot topic (8), which could provide evidence on the preventive and protective effects of soybeans and their products for lung cancer.

Several long non-coding (lnc) RNAs and their biological functions have been identified with the use of high throughput technology (9). For example, BCYRN1 was found to function as a competing endogenous RNA to inhibit glioma progression by sponging microRNA-619-5p to regulate CUEDC2 expression and the PTEN/AKT/p21 pathway (10). Zhu et al (11) identified key lncRNAs in rectal adenocarcinoma using RNA sequencing and dysregulation of lncRNAs have been associated with lung cancer initiation and progression. lncRNAs play a vital role in regulating biological processes through epigenetic, transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (12–15). Abnormal expression of lncRNAs have been associated with apoptosis, invasion and metastasis of lung cancer, which is conducive to the progression of lung cancer (16–18), and it has been demonstrated that lncRNAs act as effective markers for the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with lung cancer (19). Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the potential functions of daidzein on H1299 lung cancer cells by analyzing lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles, using microarray analysis. The results provide novel insight into the molecular mechanism of daidzein in lung cancer cell lines.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The human H1299 lung cancer cells were purchased from Wuhan University (Hubei, China). The cells were maintained in high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Haoyang Biological Products Technology Co., Ltd.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Extraction of RNA from H1299 cells and RNA quality control

Total RNA was extracted from the H1299 cells using TRIzol® (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 4 ml medium, supplemented with dimethyl sulfoxide (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to the cells in the control group for 24 h at 37°C, while 4 ml 10 µM daidzein (Shanxi Huike Plant Development Co., Ltd.) was added to the cells in the treatment group for 24 h at 37°C. The RNA was extracted from the cells in both groups after 24 h. The purity and concentration of the RNA was determined from optical density 260/280 ratio using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA integrity was determined by 1% formaldehyde denaturing gel electrophoresis.

RNA labeling and microarray hybridization

cDNA labeled with fluorescent dyes (Cy5 and Cy3-dCTP) was produced using they Eberwine's linear RNA amplification method and subsequent enzymatic reaction, as previously described (20), which has also been improved using CapitalBio cRNA Amplification and Labeling kit (CapitalBio Technology, Inc.) to produce higher yields of labeled cDNA.

In detail, double-stranded cDNA (containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence) was synthesized from 1 µg total RNA using the CbcScript reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (CapitalBio Technology, Inc.), with T7 Oligo (dT) and T7 Oligo (dN). Following double-stranded cDNA synthesis using DNA polymerase and RNase H, the products were purified using a PCR NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel, GmbH and Co., KG) and eluted with 30 µl elution buffer. The eluted double-stranded cDNA products were then vacuum evaporated to 16 µl and reverse transcribed at 37°C for 14 h using a T7 Enzyme Mix. The amplified cRNA was purified using the RNA Clean-up kit (MN). The Klenow enzyme labeling method was used following RT using CbcScript II reverse transcriptase. Briefly, 2 µg amplified RNA was mixed with 4 µg random nanomer, denatured at 65°C for 5 min, then cooled on ice. Subsequently, 5 µl 4X first-strand buffer, 2 µl 0.1M DTT and 1.5 µl CbcScript II reverse transcriptase was added, then the samples were incubated at 25°C for 10 min, and 37°C for 90 min. The cDNA products were purified using a PCR NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel, GmbH and Co., KG), then vacuum evaporated to 14 µl. The cDNA was mixed with 4 µg random nanomer, heated to 95°C for 3 min, then snap cooled on ice for 5 min. Next, 5 µl Klenow buffer, dNTP and Cy5-dCTP or Cy3-dCTP (GE Healthcare) was added to a final concentration of 240 µM each for the dNTPs and 40 µM Cy-dCTP. A total of 1.2 µl Klenow enzyme was then added and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. The labeled cDNA was purified with a PCR NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel, GmbH and Co., KG) and resuspended in elution buffer. The labeled controls and test samples labeled with Cy5-dCTP and Cy3-dCTP were dissolved in 80 µl hybridization solution containing 3XSSC, 0.2% SDS, 5X Denhardt's solution and 25% formamide. The DNA in the hybridization solution was denatured at 95°C for 3 min prior to loading onto a microarray. The arrays were hybridized in an Agilent Hybridization Oven (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) overnight at a rotation speed of 20 rpm at 42°C then washed with two consecutive solutions (0.2% SDS and 2X SSC at 42°C for 5 min, then 0.2X SSC for 5 min at room temperature).

Microarray imaging and data analysis

The lncRNA + mRNA array data was analyzed for data summarization, normalization and quality control using the GeneSpring software v13.0 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). To select the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs fold-change (FC) ≥2 and ≤-2 and P<0.05 (unpaired t-test). The data was log2 transformed and the median value was determined using the Adjust Data function in the CLUSTER v3.0 software (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm), then further analyzed using hierarchical clustering with average linkage (21). Finally, tree visualization was performed using Java Treeview (Stanford University School of Medicine). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and Gene Ontology (GO) (http://www.geneongoloty.org/) analyses were performed to determine the function of differentially expressed mRNAs in biological pathways and GO terms (with a cut-off of P<0.05). After gene annotation function, STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins; http://string-db.org/) was used to identify the relationship between protein expression levels, in which a protein-protein interaction network was created.

Co-expression analysis and transcription factor prediction

Co-expression analysis is used to perform correlation analysis on the signal value trend of differential expressed lncRNA and mRNA in all samples (experimental group and control group) after comparison. Correlation, >0.99 or <-0.99 was used as the screening criteria, with P<0.05. The lncRNA/mRNA relationship pair, that met the aforementioned conditions was considered to have a co expression relationship. Transcription factor prediction (TFs_predict), which uses the Match-1.0 Public (http://gene-regulation.com/pub/programs.html%23match) transcription factor prediction tool, was used to predict the binding sites of TFs, 2,000 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the start site of each lncRNA based on the co-expression results, and network diagrams are created using Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/download.php) software.

RT-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from the cell cultures was extracted using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), reverse transcribed into cDNA using the EasyScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 15 min at 42°C, 5 sec at 85°C, then stored at 4°C until further use. qPCR was performed on a CFX Connect Real-Time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with TransStart® Top Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. GAPDH served as an internal control and was included in the same PCR reaction with differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs for RT-qPCR. The primer sequences used for the qPCR of the lncRNAs and mRNAs are listed in Table I. Relative expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method (22).

Table I.

Primer sequences used for lncRNAs and mRNAs in reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Name | Forward primer sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ENST00000608897.1 | GTGCAAATACAGGCCAAGTCAG | TCCCCAAAAAGATGCCAAGG |

| ENST00000444196.1 | TCGTGTGATCTGCCAGTTTC | TGGAAGGCAGGATTTTGACC |

| ENST00000608741.1 | TCTTCCTGGTGCACTCAGATG | TTGCAGTCCTAACGCGACTC |

| XR_242163.1 | CATACGAGATGGAGATATCATCC | CAAATTCTTCTTCTCTAAGATG |

| ENST00000505196.1 | AGCCCGGAAATAAGAATGGC | TTCTGGCCTGTGATGAACTCC |

| ENST00000498032.1 | TCAAGAGACCGAGACCATCC | CTCACTACAAGCTCCGCCT |

| ROPN1L | TGTGCCTGCCGAAGGAAAAAT | GTTCAAGGACCCACCAAGCAT |

| FANCC | CTGCCATATTCCGGGTTGTTG | AGCACTGCGTAAACACCTGAA |

| FAM149B1 | ATCTACTGAAGGAAGCTCGGAC | CACACTCAACTTCTGCTCATACA |

| TRHR | CCAAACACAGCTTCAGCCAC | GGCTCACCAGGTAGCAGTTT |

| IGF1 | GCTCTTCAGTTCGTGTGTGGA | GCCTCCTTAGATCACAGCTCC |

| TTN | CCCCATCGCCCATAAGACAC | CCACGTAGCCCTCTTGCTTC |

| GAPDH | GGAGTCCACTGGCGTCTTCA | GTCATGAGTCCTTCCACGATACC |

lnc, long non-coding.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp.). The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Differences between groups were assessed using a two tailed unpaired t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

In vitro experiments

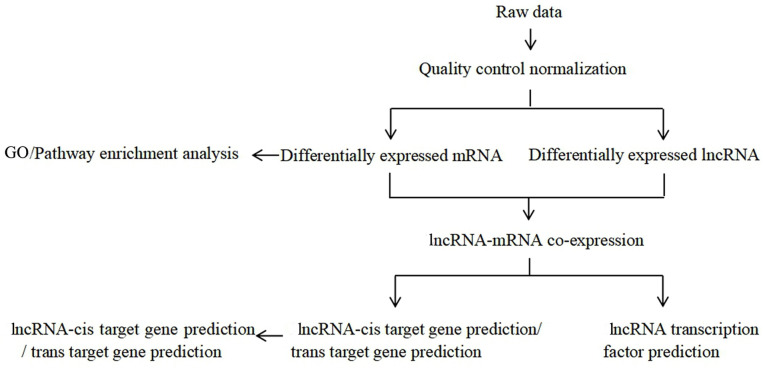

The preliminary in vitro experiments showed that daidzein had the strongest inhibitory effect on the proliferation of H1299 cells (data not shown); therefore, these cells were used for further experiments. The soybean isoflavones were extracted, which are the active ingredients in legumes, and daidzein and its derivatives were synthesized and purified. The experimental flow chart of the present study is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the analysis performed in the present study. lnc, long non-coding; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Overview of lncRNAs and mRNAs profiles

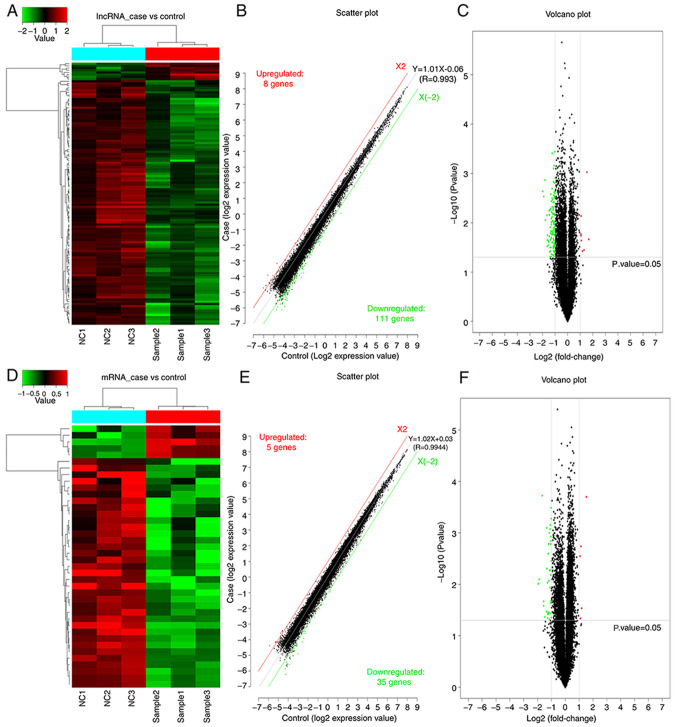

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of daidzein on H1299 cells. Gene cluster analysis of the mRNAs and lncRNAs was performed following treatment with daidzein. The clustering map demonstrated similarities between the samples.

As presented in Fig. 2, a significant difference in both mRNAs and lncRNAs was observed between the experimental group of cells treated with daidzein and the control group of untreated with daidzein. Following the addition of daidzein, the expression level of eight lncRNAs was upregulated in the H1299 cells, while 111 lncRNAs were downregulated. In addition, five mRNAs were upregulated and 35 mRNAs were downregulated. In Fig. 2A and D, the top sample tree represents the similarity clustering relationship between the different samples. The top color block represents the expected grouping of the samples manually set prior to the cluster analysis, and the samples of the same color indicate that the experiment is expected to be a group. The red line in Fig. 2B and E, X2, is the threshold boundary line of the upregulated lncRNA/mRNAs, while the green line X (−2) is the threshold boundary line of the downregulated lncRNA/mRNAs, and the middle gray line is the fitted line of the overall expression amount. The equation in is the fitted line equation, and R represents the correlation coefficient between the two sets of samples.

Figure 2.

Sample analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs from the H1299 cell line treated with and without daidzein. (A and D) lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles. Each column represents a sample, while each row represents the degree of expression of a lncRNA or mRNA in a different sample. Red denotes high expression level, while green denotes low expression. (B and E) Scatter plots of the up- and downregulated lncRNA and mRNAs with equations and log-converted values. The number of up- and downregulated lncRNA and mRNAs are presented in the upper left and lower right corners, respectively. (C and F) Volcano plots showing the up- and downregulated lncRNA/mRNAs. The abscissa is -log10 (P-values) and the ordinate is log2 (fold-change). Red denotes the upregulated lncRNA/mRNAs, while green denotes the downregulated lncRNA/mRNAs, and black denotes no significant difference in gene expression. NC, non-treated control; lnc, long non-coding.

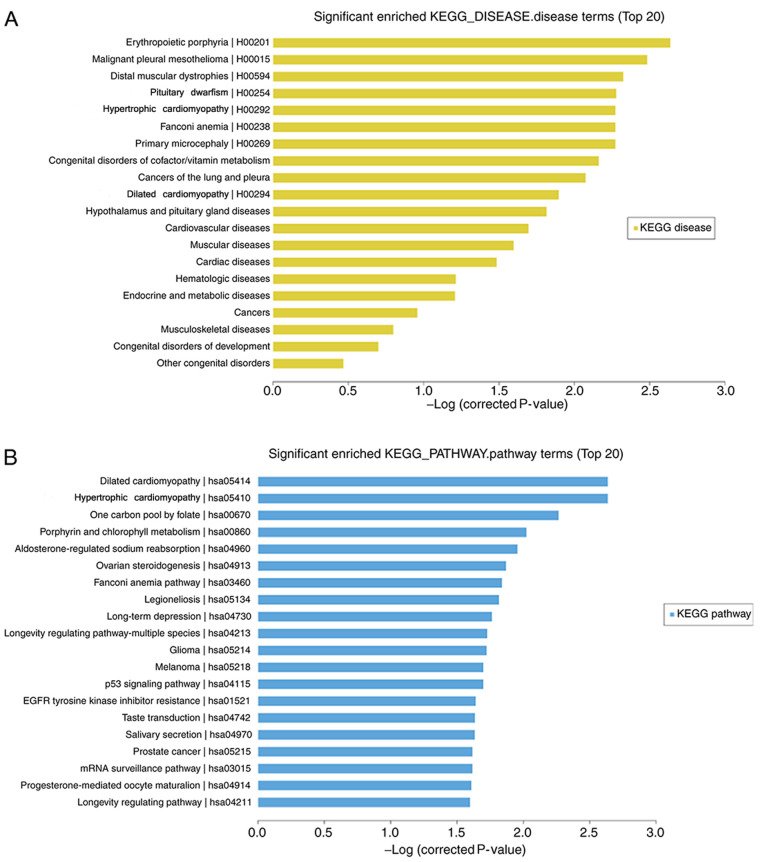

KEGG pathway enrichment and GO analysis

Microarray analysis revealed that 40 mRNAs (5 upregulated and 35 downregulated) were significantly differentially expressed in the H1299 cell line treated with daidzein compared with that in the cells treated without daidzein (FC≥2.0; P<0.05). The top 20 significantly enriched KEGG pathway and disease terms were selected. The top three terms that were enriched for gene-affected diseases following daidzein treatment were: ‘Erythropoietic protoporphyrin’, ‘malignant pleural mesothelioma’ and ‘distal myopathy’. The addition of daidzein also affected the genes involved in diseases, including cancer of the lung and pleura, the results of which were consistent with the research model (Fig. 3A). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that ‘dilated cardiomyopathy’ (hsa05414), ‘hypertrophic cardiomyopathy’ (hsa05410), ‘long-term depression’ (hsa04730), ‘p53 signaling pathway’ (hsa04115) were included in the top 20 pathways (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs. The top 20 significantly enriched (A) disease terms and (B) pathway terms were selected. The-log (corrected P-value) indicates the significance of the KEGG disease terms and pathways. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

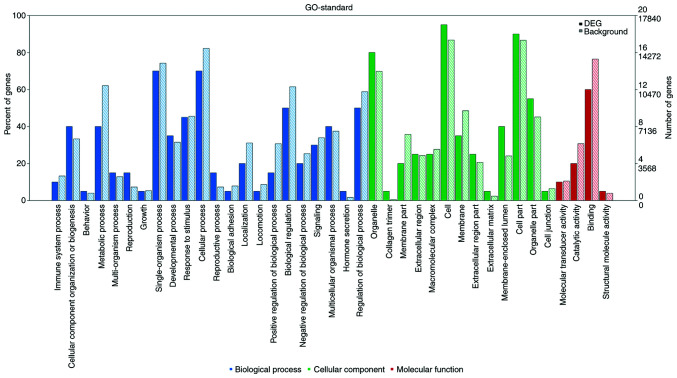

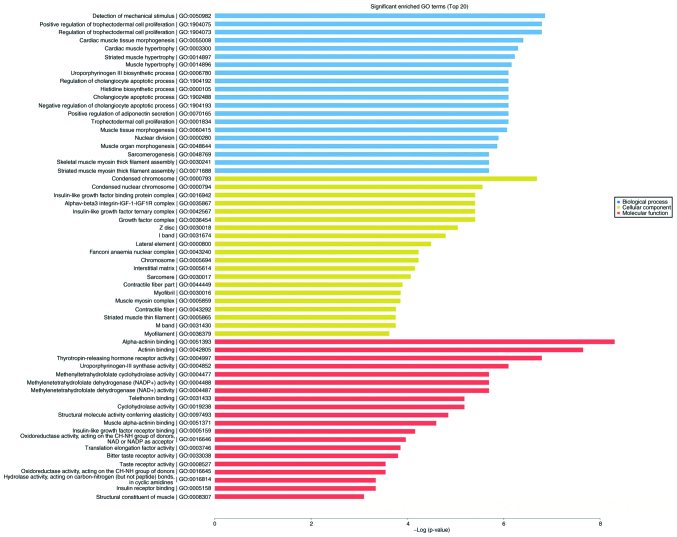

As shown in Fig. 4, numerous differentially expressed mRNAs, compared with that to the background mRNAs, were enriched in biological processes, molecular function and cellular component categories, and the top 20 significantly enriched terms were selected from GO analysis. The results (Fig. 5) indicated that the most significantly enriched GO terms associated with the differentially expressed mRNAs were ‘detection of mechanical stimulus’ (biological processes; GO:0050982; P=0.0010488989), ‘condensed chromosome’ (cellular component; GO:0000793; P=0.0012408009), ‘α-actinin binding’ (molecular function; GO:0051393; P=0.0002475636). Several of the differentially expressed genes were localized in the cytoplasm and altered the expression of molecular functional genes associated with ‘binding’.

Figure 4.

GO analysis of the differentially expressed mRNAs. Frequency analysis graph of secondary items of GO analysis includes biological processes, cellular component and molecular function. The percentage and number of the genes is shown on the left and right vertical axis respectively. GO, Gene Ontology.

Figure 5.

GO enrichment analysis results (top 20) for BP, MF and CC of differentially expressed mRNAs in H1299 lung cancer cells treated with daidzein. P-values are shown.

Co-expression analysis

Co-expression analysis was performed to determine the association between lncRNA and mRNA pairs, with similar expression profiles, at the genomic level. The association between differentially expressed mRNAs and lncRNAs following the addition of daidzein is presented in Fig. S1A. Following the addition of daidzein, the co-expressed mRNAs with differentially expressed lncRNAs included: XLOC_I2_013457, LOC284825, CIQTNF3, FILP1, FANCC, SPATA4, FLJ41455, ANKRD12, SYCP2, RTKN2 and MTHFD2L.

Transcription factor prediction

The transcription factor was predicted (TFs_predict) using the Match-1.0 Public transcription factor prediction tool (Fig. S1B). Based on the co-expression results, the binding of transcription factors, 2,000 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of each lncRNA initiation sites was predicted. The relevant transcription factors of differentially expressed lncRNAs, following the addition of daidzein to the H1299 cells, included Oct-1, HNF-1, HNF-4, Pax-4, COMP1, Pax-6, FOXD3 and FOXJ2.

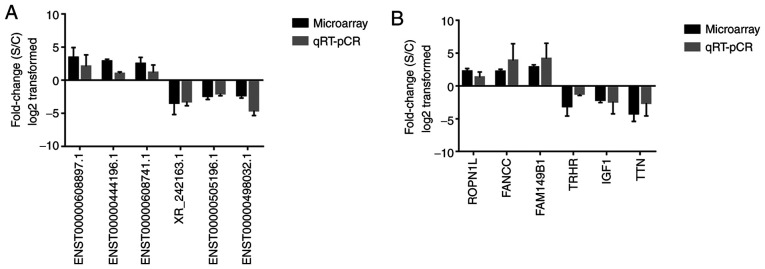

RT-qPCR validation of microarray data

A total of six differentially expressed lncRNAs and six mRNAs were randomly selected to validate the microarray data. RT-qPCR analysis was performed to determine the fold changes of selected lncRNAs and mRNAs, respectively (Fig. 6). The fold-change was positive when the expression was upregulated and negative when the expression was downregulated. Thus, the RT-qPCR results were consistent with the microarray data.

Figure 6.

Expression level of lncRNAs and mRNAs from the H1299 cell line treated with and without daidzein. The validation of six (A) lncRNAs and (B) mRNAs using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. lnc, long non-coding; S, sample (H1299 cells treated with daidzein); C, control (H1299 cells without treatment); RT-qPCR; reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

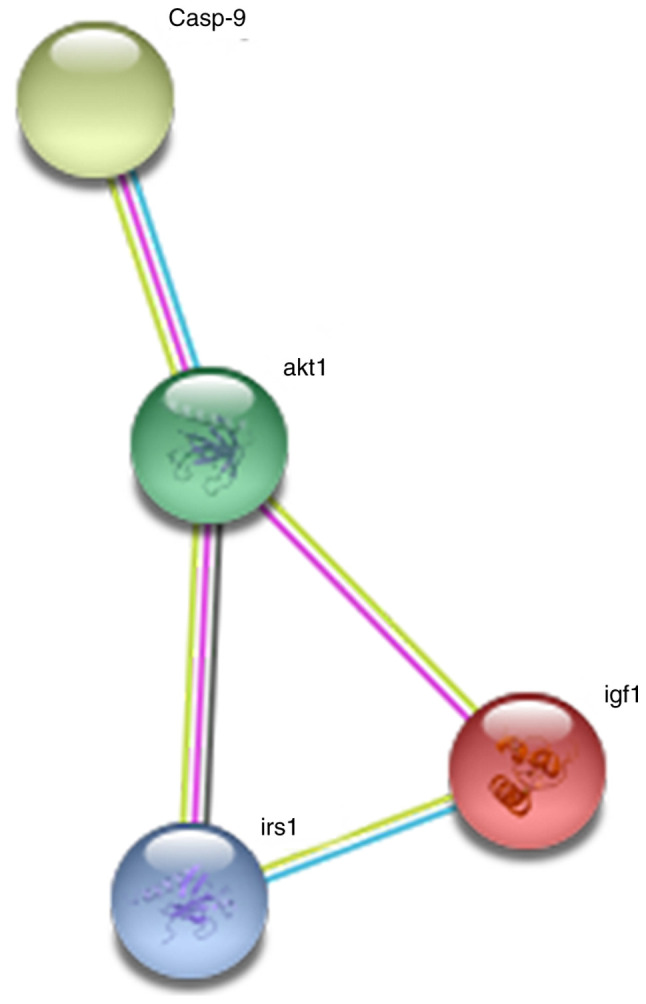

Construction of core gene interaction protein association

As presented in Fig. 7, the somatostatin C protein encoded by the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) gene interacted directly with the IGF1 receptor, IRS, AKT and caspase-9 proteins. Collectively, these results suggested that the IGF1 gene plays an important role in the development of tumors.

Figure 7.

Protein-protein interaction network of the pathways from the differentially expressed mRNAs.

Discussion

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors, that threatens the health and life of those affected (23). Due to the complexity of its molecular mechanisms, there has been an increased effort to identify early and accurate prevention, diagnosis and treatment to decrease the mortality rate (24). Previous studies have demonstrated that soy products inhibit tumor development (25–30). An epidemiological study reported that soy-related foods can decrease the risk of lung cancer mortality (31). A previous study demonstrated that isoflavones were also associated with a decreased risk of lung cancer, both in vivo and in vitro (32); however, the specific molecular mechanism remains unclear. In addition, gene chip technology has enabled the investigation of differential gene expression, particularly in the identification of tumor differential genes (33,34).

A previous study reported that lncRNAs were differentially expressed in normal and cancer cells (35). lncRNAs are non-coding RNA molecules, ~200 nucleotides in length (36). Aberrant lncRNA expression is a major characteristic of several types of cancer, which has been demonstrated to play an important role in promoting the development and progression of human cancer (37). For example, upregulated expression of the carcinogenic lncRNA, HOTAIR has been associated with breast, colorectal and liver cancers (38,39). Zhang et al (40) demonstrated that overexpression of lncRNA, UFC1 promoted the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. The association between lncRNA and lung cancer has also been extensively investigated (41–43). However, there is lack of research into the molecular mechanism of action of soybean and its products on lung cancer cells, using the expression profile data of microarray.

The present study analyzed the difference in mRNA and lncRNA expression levels between daidzein-treated and -untreated H1299 lung cancer cells, based on the original results of the gene chip. Bioinformatics (KEGG enrichment and GO analyses) and RT-qPCR were performed to observe the expression of differential genes to further investigate the molecular mechanism of soy isoflavones and their derivatives in NSCLC. Sample clustering demonstrated that there was a significant difference between the experimental and the control groups, suggesting that daidzein could significantly affect the lncRNA and mRNA expression levels in lung cancer cells. The results of this experiment demonstrated that following treatment with daidzein, eight and 11 lncRNAs were up- and downregulated in H1299 lung cancer cells, respectively. In addition, five and 35 mRNAs were up- and downregulated, respectively. To obtain preliminary insights into lncRNA target gene function, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed using the lncRNA target gene pool. KEGG analysis of the differentially expressed lncRNAs identified the top 20 diseases associated, which included cancers of the lung and pleura and malignant pleural mesothelioma diseases. KEGG analysis also demonstrated that the addition of daidzein affected the pathways involved in cancer-associated genes, namely the P53 signaling pathway, suggesting that the addition of daidzein could affect tumor proliferation. GO analysis revealed that the genes involved in stress-related biological processes changed following addition of daidzein to lung cancer cells. Several of the differentially expressed genes were localized in the cytoplasm and altered the expression of molecular functional genes associated with ‘binding’. Collectively, these results suggested that the molecular mechanism of action of daidzein in the lung cancer cells may be associated with the alteration of molecular functions associated with ‘binding’ in the cytoplasm. RT-q PCR was performed using six randomly selected lncRNAs and mRNAs in samples from a lung cancer cell line to validate the microarray results. A total of six lncRNAs and mRNAs identified in the microarray analysis were confirmed to be aberrantly expressed in lung cancer cells via RT-qPCR analysis.

As lung cancer is a serious threat to human health, researchers have been investigating the molecular mechanisms that inhibit lung cancer from all aspects, including the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, autophagy and apoptosis of lung cancer cells (44–47). There are several studies investigating the apoptotic mechanism associated with the p53 gene (48–50). It is well-known that p53 plays a key role in inducing apoptosis in numerous types of cancer, such as lung, gastric and prostate cancers (51–53). In a previous study, daidzein inhibited the proliferation and NF-κB signaling pathway in lung cancer cells (54). Therefore, it was hypothesized that daidzein could promote the apoptosis of cancer cells via the P53 apoptosis pathway, which could inhibit the proliferation of lung cancer cells. From the microarray analysis, in the present study, the P53 pathway was included in the top 20 pathways with differential gene enrichment, which provides a potential mechanism for future research, to further identify the specific mechanism involved.

Previous studies have demonstrated that high IGF1 expression level was associated with an increased risk of breast, prostate, colorectal and lung cancers (55–58). In addition, the IGF-binding protein, that regulates the IGF1 gene, has been found to have proapoptotic activities, both dependent and independent of p53 (59). Zhang et al (60) reported that the IGF1 receptor plays a key role in radiation-induced apoptosis of lung cancer cells. Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that the occurrence of lung cancer is associated with the dysregulation of IGF1, which affects the tumor suppressor gene, p53 (61). Consistent with these previous findings, the results of the present study demonstrated that IGF1 was differentially expressed and the addition of daidzein to the lung cancer cell line affected the p53 signaling pathway.

The present study has two major limitations. First, the study only focused on the H1299 cell line of NSCLC; therefore, other NSCLC cell lines and those from SCLC will also be investigated in future research. Second, the present study lacks clinical data, which will be also be included in future studies to validate the results in the present study.

It has been hypothesized that IGF1 also plays a key role in the effects of daidzein in lung cancer. The present study constructed a protein-protein interaction network of the IGF1 gene using the STRING online database. The results suggested that IGF1 could mediate apoptosis by interacting with other genes in cancer-related pathways, thereby inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. This IGF1 protein forms a signaling pathway with the IGF1 receptor, IRS, AKT and caspase-9 proteins. Notably, IGF1 or a protein that interacted with IGF1 was involved in malignant tumors via the PI3K/pAKT pathway (62,63) AKT, also known as protein kinase B or Rac, is an oncogenic protein, that plays an important role in cell survival and apoptosis (64). Insulin growth factors and survival factors, including nerve growth factor and peptide trophic factors could activate the AKT signaling pathway (65). Abnormal expression of AKT and overactivation of AKT-associated pathways have been found to be involved in the development of different types of cancer, including lung, breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers, and have been associated with the proliferation and survival of lung cancer cells and apoptosis (66–69). Taken together, these findings suggested that the AKT signaling pathway could be used as a therapeutic target for lung cancer.

In mammalian cells, one of the endogenous pathways of apoptosis is the activation of caspase-9 (70). Caspases are proteolytic enzymes, that are involved in cell apoptosis. Caspase-9 is one of the most critical components of apoptosis in the caspase family (54). Previous studies have provided valuable insight for the potential of daidzein to induce apoptosis via different pathways and delay the progression of lung cancer (71,72). Thus, the IGF1 gene has been considered as a promising candidate gene, and the gene network should be the focus of follow-up research on the molecular mechanism of soybean action in lung cancer. Collectively, the results of the present study provide a novel biomarker for the treatment of lung cancer; however, further research is required to validate the results.

In conclusion, the results of the present study revealed a set of lncRNAs which were differentially expressed in lung cancer cells following treatment with daidzein. Taken together, these findings suggested that daidzein could significantly affect lncRNA expression in lung cancer cells. Furthermore, the results also demonstrated that the molecular mechanism of action of daidzein in lung cancer cells may be associated with the alteration of molecular functions associated with ‘binding’ in the cytoplasm. The results presented here provide novel insight into the molecular mechanism of daidzein in the H1299 lung cancer cell line. In addition, genes were also identified that were co-expressed with mRNAs, as well as transcription factors predicted by lncRNAs, and promising core genes and signaling pathways. Collectively, the present study provided novel insights into the molecular mechanism of lncRNAs associated with the effect of daidzein in lung cancer and suggested that daidzein may effectively delay the progression of lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor 1

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant no. 2020BAB206067).

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant no. 2020BAB206067).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The high-throughput sequencing data is publicly available from the GEO database (accession no. GSE181093).

Authors' contributions

LFL, SXH, XW and JL conceived and designed the present study. LFL drafted the initial manuscript. LFL performed the experiments, data collection, and wrote the manuscript. XWX and SXH contributed to the methodology, performed the experiments and analyzed the data. XBW contributed to data collection and analyzed the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. XWX and SXH obtained materials and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Current cancer epidemiology. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;9:217–222. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191008.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Sun K, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, Xia C, Yang Z, Li H, Zou X, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2014. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:1–12. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.01.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson MR, Gazdar AF, Clarke BE. The pivotal role of pathology in the management of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 5):S463–S478. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.08.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z, Fillmore CM, Hammerman PS, Kim CF, Wong KK. Non-small-cell lung cancers: A heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrc3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gridelli C, Rossi A, Maione P. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: State of the art and development of new biologic agents. Oncogene. 2003;22:6629–6638. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G, Shu XO, Chow WH, Zhang X, Li HL, Ji BT, Cai H, Wu S, Gao YT, Zheng W. Soy food intake and risk of lung cancer: Evidence from the shanghai women's health study and a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:846–855. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benassayag C, Perrot-Applanat M, Ferre F. Phytoestrogens as modulators of steroid action in target cells. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777:233–248. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andres S, Abraham K, Appel KE, Lampen A. Risks and benefits of dietary isoflavones for cancer. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41:463–506. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2010.541900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng F, Wang R, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Zhou W, Chang Z, Liang H, Zhao W, Qi L, Guo Z, Gu Y. Differential expression analysis at the individual level reveals a lncRNA prognostic signature for lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:98. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mu M, Niu W, Zhang X, Hu S, Niu C. LncRNA BCYRN1 inhibits glioma tumorigenesis by competitively binding with miR-619-5p to regulate CUEDC2 expression and the PTEN/AKT/p21 pathway. Oncogene. 2020;39:6879–6892. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01466-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu X, Wang D, Lin Q, Wu G, Yuan S, Ye F, Fan Q. Screening key lncRNAs for human rectal adenocarcinoma based on lncRNA-mRNA functional synergistic network. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3875–3891. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Yang B, Zhang M, Guo W, Wu Z, Wang Y, Jia L, Li S, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Xie W, Yang D. lncRNA epigenetic landscape analysis identifies EPIC1 as an oncogenic lncRNA that interacts with MYC and promotes cell-cycle progression in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:706–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauptman N, Glavač D. Long non-coding RNA in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:4655–4669. doi: 10.3390/ijms14034655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao Z, Yang Z, Huang Z, Zhou Y, Cui Q, Dong D. LncRNADisease 2.0: An updated database of long non-coding RNA-associated diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1034–D1037. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G, Wang Z, Wang D, Qiu C, Liu M, Chen X, Zhang Q, Yan G, Cui Q. LncRNADisease: A database for long-non-coding RNA-associated diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D983–D986. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokgun O, Tokgun PE, Inci K, Akca H. lncRNAs as potential targets in small cell lung cancer: MYC-dependent regulation. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2020;20:2074–2081. doi: 10.2174/1871520620666200721130700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu T, Wang Y, Chen D, Liu J, Jiao W. Potential clinical application of lncRNAs in non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:8045–8052. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S178431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai XN, Li J, Tang LB, Chen WT, Zhang L, Xiong LX. miRNAs and LncRNAs: Dual roles in TGF-β signaling-regulated metastasis in lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1193. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M, Ma X, Zhu C, Guo L, Li Q, Liu M, Zhang J. The prognostic value of long non coding RNAs in non small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:81292–81304. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson TA, Lobenhofer EK, Fulmer-Smentek SB, Collins PJ, Chu TM, Bao W, Fang H, Kawasaki ES, Hager J, Tikhonova IR, et al. Performance comparison of one-color and two-color platforms within the microarray quality control (MAQC) project. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1140–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QW, Ma L, Qiu B, Yang H, Zhu YJ, Qiang MY, Liu SR, Chen NB, Guo JY, Cai LZ, et al. Differential expression profiles of long noncoding RNAs in synchronous multiple and solitary primary esophageal squamous cell carcinomas: A microarray analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2018 Oct 15; doi: 10.1002/jcb.27536. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong WJ, Peng JB, Yin JY, Li XP, Zheng W, Xiao L, Tan LM, Xiao D, Chen YX, Li X, et al. Association between well-characterized lung cancer lncRNA polymorphisms and platinum-based chemotherapy toxicity in Chinese patients with lung cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:581–590. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao T, Jin F, Li J, Xu Y, Dong H, Liu Q, Xing P, Zhu G, Xu H, Miao Z. Dietary isoflavones or isoflavone-rich food intake and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tse G, Eslick GD. Soy and isoflavone consumption and risk of gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada K, Tsuji M, Tamura T, Konishi K, Kawachi T, Hori A, Tanabashi S, Matsushita S, Tokimitsu N, Nagata C. Soy isoflavone intake and stomach cancer risk in Japan: From the Takayama study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:885–892. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaheer K, Humayoun AM. An updated review of dietary isoflavones: Nutrition, processing, bioavailability and impacts on human health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:1280–1293. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.989958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Applegate C, Rowles J, Ranard K, Jeon S, Erdman J. Soy consumption and the risk of prostate cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10:40. doi: 10.3390/nu10010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo HD, Kim J. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroentero. 2013;19:1011–1019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nachvak SM, Moradi S, Anjom-Shoae J, Rahmani J, Nasiri M, Maleki V, Sadeghi O. Soy, soy isoflavones, and protein intake in relation to mortality from all causes, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119:1483–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan N, Mukhtar H. Dietary agents for prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;359:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan W. A comparative review of statistical methods for discovering differentially expressed genes in replicated microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:546–554. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Z, Fan C, Oh DS, Marron JS, He X, Qaqish BF, Livasy C, Carey LA, Reynolds E, Dressler L, et al. The molecular portraits of breast tumors are conserved across microarray platforms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu X, Ravindranath L, Tran N, Petrovics G, Srivastava S. Regulation of apoptosis by a prostate-specific and prostate cancer-associated noncoding gene, PCGEM1. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:135–141. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, Barrette TR, Prensner JR, Evans JR, Zhao S, et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2015;47:199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai M, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue X, Yang YA, Zhang A, Fong K, Kim J, Song B, Li S, Zhao JC, Yu J. LncRNA HOTAIR enhances ER signaling and confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:2746–2755. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazemzadeh M, Safaralizadeh R, Orang AV. LncRNAs: Emerging players in gene regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Genet. 2015;94:771–784. doi: 10.1007/s12041-015-0561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Liang W, Liu J, Zang X, Gu J, Pan L, Shi H, Fu M, Huang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA UFC1 promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating miR-498/Lin28b. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:134. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0803-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chi Y, Wang D, Wang J, Yu W, Yang J. Long non-coding RNA in the pathogenesis of cancers. Cells. 2019;8:1015. doi: 10.3390/cells8091015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen R, Li WX, Sun Y, Duan Y, Li Q, Zhang AX, Hu JL, Wang YM, Gao YD. Comprehensive analysis of lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles in lung cancer. Clin Lab. 2017;63:313–320. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei MM, Zhou GB. Long non-coding RNAs and their roles in non-small-cell lung cancer. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2016;14:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han Q, Lin X, Zhang X, Jiang G, Zhang Y, Miao Y, Rong X, Zheng X, Han Y, Han X, et al. WWC3 regulates the Wnt and Hippo pathways via dishevelled proteins and large tumour suppressor 1, to suppress lung cancer invasion and metastasis. J Pathol. 2017;242:435–447. doi: 10.1002/path.4919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao L, Li H, Chen J, Song H, Zhang Y, Wu F, Wang W, Zhang W, Wang F, Li H, Tang D. Irisin suppresses the migration, proliferation, and invasion of lung cancer cells via inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;485:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai X, Meng L, Sun H, Li Z, Zhang X, Hua S. MicroRNA-196b inhibits cell growth and metastasis of lung cancer cells by targeting Runx2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:757–767. doi: 10.1159/000481559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G, Pei F, Yang F, Li L, Amin AD, Liu S, Buchan JR, Cho WC. Role of autophagy and apoptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:367. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gan PP, Zhou YY, Zhong MZ, Peng Y, Li L, Li JH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes autophagy and apoptosis and reduces chemotherapy resistance in mutant p53 lung cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:133–151. doi: 10.1159/000484622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Su C, Zhao F, Tao J, Hu D, Shi A, Pan J, Zhang Y. Paclitaxel promotes lung cancer cell apoptosis via MEG3-P53 pathway activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;504:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu YH, Liu GH, Mei JJ, Wang J. The preventive effects of hyperoside on lung cancer in vitro by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation through Caspase-3 and P53 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldar S, Khaniani MS, Derakhshan SM, Baradaran B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2129–2144. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.6.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Li Q, Wei S, Sun J, Zhang X, He L, Zhang L, Xu Z, Chen D. ZNF143 suppresses cell apoptosis and promotes proliferation in gastric cancer via ROS/p53 axis. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:5863178. doi: 10.1155/2020/5863178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta A, Behl T, Heer HR, Deshmukh R, Sharma PL. Mdm2-P53 interaction inhibitor with cisplatin enhances apoptosis in colon and prostate cancer cells in-vitro. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20:3341–3351. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.11.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarfstein R, Nagaraj K, LeRoith D, Werner H. Differential effects of insulin and IGF1 receptors on ERK and AKT subcellular distribution in breast cancer cells. Cells. 2019;8:1499. doi: 10.3390/cells8121499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma JB, Bai JY, Zhang HB, Jia J, Shi Q, Yang C, Wang X, He D, Guo P. KLF5 inhibits STAT3 activity and tumor metastasis in prostate cancer by suppressing IGF1 transcription cooperatively with HDAC1. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:466. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2671-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu J, Liu X, Chi J, Che K, Feng Y, Zhao S, Wang Z, Wang Y. Expressions of IGF-1, ERK, GLUT4, IRS-1 in metabolic syndrome complicated with colorectal cancer and their associations with the clinical characteristics of CRC. Cancer Biomark. 2018;21:883–891. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YA, Sun Y, Palmer J, Solomides C, Huang LC, Shyr Y, Dicker AP, Lu B. IGFBP3 modulates lung tumorigenesis and cell growth through IGF1 signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:896–904. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furstenberger G, Senn HJ. Insulin-like growth factors and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:298–302. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H, Zhang C, Wu D. Activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor regulates the radiation-induced lung cancer cell apoptosis. Immunobiology. 2015;220:1136–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brambilla E, Gazzeri S, Gouyer V, Brambilla C. Mechanisms of lung oncogenesis. Rev Prat. 1993;43:807–814. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang LJ, Li QJ, Le Y, Ouyang HY, He MK, Yu ZS, Zhang YF, Shi M. Prognostic significance of sodium-potassium ATPase regulator, FXYD3, in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:3024–3030. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Velloso FJ, Bianco AF, Farias JO, Torres NE, Ferruzo PY, Anschau V, Jesus-Ferreira HC, Chang TH, Sogayar MC, Zerbini LF, Correa RG. The crossroads of breast cancer progression: Insights into the modulation of major signaling pathways. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:5491–5524. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S142154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chuang CH, Cheng TC, Leu YL, Chuang KH, Tzou SC, Chen CS. Discovery of Akt kinase inhibitors through structure-based virtual screening and their evaluation as potential anticancer agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:3202–3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms16023202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: A play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu X, Yuan Y, Zhi X, Teng B, Chen X, Huang Q, Chen Y, Guan Z, Zhang Y. Correlation between the protein expression of A-kinase anchor protein 95, cyclin D3 and AKT and pathological indicators in lung cancer tissues. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:1175–1181. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim BM, Kim DH, Park JH, Surh YJ, Na HK. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits constitutive activation of NF-kB signaling in human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells: ERK and akt as potential upstream targets. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:23–30. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2014.19.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bellacosa A, Testa JR, Moore R, Larue L. A portrait of AKT kinases: Human cancer and animal models depict a family with strong individualities. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:268–275. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng JQ, Lindsley CW, Cheng GZ, Yang H, Nicosia SV. The Akt/PKB pathway: Molecular target for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2005;24:7482–7492. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hirsch T, Marzo I, Kroemer G. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in apoptosis. Biosci Rep. 1997;17:67–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1027339418683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koo J, Cabarcas-Petroski S, Petrie JL, Diette N, White RJ, Schramm L. Induction of proto-oncogene BRF2 in breast cancer cells by the dietary soybean isoflavone daidzein. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:905. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1914-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo S, Wang Y, Li Y, Li Y, Feng C, Li Z. Daidzein-rich isoflavones aglycone inhibits lung cancer growth through inhibition of NF-kB signaling pathway. Immunol Lett. 2020;222:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The high-throughput sequencing data is publicly available from the GEO database (accession no. GSE181093).