Abstract

Background

Whole‐systems approaches (WSAs) are well placed to tackle the complex local environmental influences on overweight and obesity, yet there are few examples of WSAs in practice. Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach (AHWA) is a long‐term, municipality‐led program to improve children's physical activity, diet, and sleep through action in the home, neighborhood, school, and city. Adopting a WSA, local political, physical, social, educational, and healthcare drivers of childhood obesity are viewed as a complex adaptive system. Since 2013, AHWA has reached >15,000 children. During this time, the estimated prevalence of 2–18‐year‐olds with overweight or obesity in Amsterdam has declined from 21% in 2012 to 18.7% in 2017. Declining trends are rarely observed in cities. There is a need to formally articulate AHWA program theory in order to: (i) inform future program evaluation which can interpret this decline within the context of AHWA and (ii) contribute a real‐life example of a WSA to the literature.

Methods

This study aimed to formally document the program theory of AHWA to permit future evaluation. A logic framework was developed through extensive document review and discussion, during program implementation.

Results

The working principles of the WSA underpinning AHWA were made explicit in an overarching theory of change, articulated in a logic framework. The framework was operationalized using an illustrative example of sugar intake.

Conclusions

The logic framework will inform AHWA development, monitoring, and evaluation and responds to a wider need to outline the working principles of WSAs in public health.

Keywords: childhood obesity, childhood overweight, diet, inequalities, physical activity, whole‐systems approach

1. INTRODUCTION

Growing evidence suggests key modifiable influences on overweight and obesity lie in our local environments.1, 2, 3, 4 While local environments are also shaped by global and national influences such as industry and trade laws, local influences—such as healthy food availability or social norms for physical activity—can be conceptualized as a complex adaptive system of distal and proximal influences which work together to produce patterns of behavior underpinning overweight and obesity.5 The foresight report illustrates the dense and extensive web of influences which are widely considered to foster overweight and obesity through the fundamental features of a complex adaptive system: long, nonlinear causal chains which over time produce emergent properties and unintended effects in a dynamic system.6

Whole‐systems approaches (WSAs) are well placed to tackle the complex adaptive system of local environmental influences on overweight and obesity.7 While acting within this system, programs adopting a WSA can also be understood as indivisible from the complex adaptive system. In comparison to traditional approaches which introduce predefined health interventions to targeted contexts or populations, we broadly characterize the working principles of a WSA as:

Multi‐level action to address multiple, interacting factors influencing the outcome of interest within a specific context or population (e.g., intervening simultaneously at the level of the individual, home, and school to promote fruit and vegetable intake—rather than using isolated actions at any one level—to ensure there is simultaneous capability, opportunity, and motivation to perform the desired behavior)

Cross‐sectoral working with diverse actors across government, public (academia, charity, community), and private organizations to develop and implement multilevel action (e.g., creating a healthy food environment at sports events is likely to require the action of policymakers to mandate or advise for healthy environments, researchers to understand what constitutes a healthy food environment, and private and public operators of sports facilities to implement required changes), implementing health‐in‐all‐policies (HiAP) is a core facilitatory aspect of cross‐sectoral working

Capacity for responsive adaptation to achieve sustainable impact: action within a system must respond to emergent relationships which manifest due to systems change (e.g., introduction of healthy school canteens may inadvertently strengthen a relationship between social norms around fast food consumption and proximity of fast food outlets to schools, requiring responsive action to address this emergent relationship).8, 9 Responsive adaptation could entail a change of program focus, implementation, or content

While a number of programs have delivered suites of multilevel interventions (e.g., packages of predefined actions across individual, environmental, and political settings) to tackle overweight and obesity, Bagnall et al.'s 2019 review found no examples of an “authentic” WSA encompassing a systems‐based approach to problem identification and program design.8 More recently, innovative programs have designed obesity prevention strategies from a complex systems perspective (e.g., The Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity 10 in Australia and Childhood Obesity Trailblazers Programme 11 informed by Public Health England guidance12). However, to our knowledge, there are no examples of long‐running, city‐wide WSAs which attempt to prevent childhood overweight and obesity through working principles which foster capacity for responsive adaptation. In other words, while the first two working principles of WSAs have been applied, the third principle has not, meaning the relationship between the WSA and the complex adaptive system in which it operates has not been the focus of the program.8, 9 As a result, the literature documents the theoretical value of “authentic” WSAs but provides limited detail on their description and operationalization using concrete examples from practice.13 This impedes understanding of such approaches and arguably contributes to the continued conception and design of obesity prevention programs as packages of isolated actions rather than coordinated actions that are indivisible from a complex adaptive system.14, 15

Insights from an existing WSA to obesity prevention, with specific attention for the working principle of responsive adaptation, could inform the design of others and contribute to current discussion around methods to evaluate WSAs, which—being neither predefined nor assumed to cause predictable and static outcomes—are not amenable to traditional evaluative methods such as controlled trials.16

Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach (AHWA or Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme; Amsterdamse Aanpak Gezond Gewicht in Dutch) aims to promote healthy weight development in children living in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, by stimulating healthy diet, physical activity, and sleep. AHWA constitutes a WSA since it adopts the following working principles:

Multi‐level actions aiming to modify the local political, physical, social, health education, and care environment in multiple settings (the home, neighborhood, school, health care, and city)

Cross‐sectoral working across municipal sectors (responsible for public health, spatial planning, sport, education, welfare, poverty reduction, economic affairs, youth, and neighborhood work) and public, private, and community partners to develop and implement actions

A learning approach to enable program adaptation in response to change in the complex adaptive system comprising the local environment (i.e., Amsterdam)

Using this approach, AHWA focuses on transforming the local environment to provide the optimal conditions for healthy patterns of diet, sleep, physical activity, and sedentary behavior. These behaviors are direct influences on energy‐balance and body weight in childhood, in addition to being important contributors to social and economic disparities.1, 17, 18 AHWA is therefore a public health promotion program conducted across multiple settings (including healthcare) which aims to prevent children of healthy weight gaining excess weight due to obesogenic environments and to treat children with overweight and obesity through clinical practice and reduction of risk from obesogenic environments. While program content is specific to these groups, the WSA it adopts is considered applicable to any systemic public health issue requiring a holistic approach across settings.

There is a need to formally describe AHWA program theory to instruct the development, monitoring, and evaluation of AHWA, in the context of changes in childhood overweight and obesity prevalence in Amsterdam,19 and communicate AHWA program theory with interested parties. As such, a formal description of AHWA program theory can inform WSAs for overweight and obesity11, 20 by outlining what constitutes a WSA when the “spirit and ethos” is translated to practice.14 This insight will also be of value to multisectoral or healthcare practitioners who are tangentially involved in WSAs to obesity prevention by illustrating how these approaches call on or benefit from their expertise.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to articulate AHWA in a plausible and comprehensive logic framework which captures the working principles of its WSA.21, 22, 23 In articulating the approach and design of AHWA rather than detailing the actions implemented within the program, we do not aim to speculate on the effectiveness or clinical utility of the program, but to communicate AHWA program theory. This is needed to inform program development and evaluation, which, in due course, will measure the program's success in reducing childhood overweight and obesity in Amsterdam. A formal description of the development and implementation of a WSA to obesity prevention will address a noted gap in the literature.8

2. METHOD

AHWA was established by the Municipality of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, in 2012 to tackle a recognized problem of overweight and obesity in Amsterdam. Routine data from the youth healthcare department from 2012 showed that approximately 21% of the city's approx. 135,000 children (2–18‐year‐olds) were classified as overweight or obese, with unequal distribution of overweight and obesity across the city. The program delivers and coordinates initiatives in Amsterdam to sustainably transform the way the city as a whole supports healthy weight in children. The objective of AHWA is to reduce the percentage of children with overweight and obesity in Amsterdam so the city average does not deviate negatively from the national average by more than 5% and to rectify the inequitable distribution of overweight and obesity across the city. In 2019, AHWA received €4.6 million of funding and was operated by a team of approximately 80 staff (∼55 full‐time‐equivalent), including the Programme Manager (KdH), municipal researchers, and program staff.

AHWA views public health as emerging from a system of political, environmental, and individual determinants embedded in a version of Dahlgren & Whitehead's socio‐ecological model of health,24 adapted for local populations and settings (Figure S1). Accordingly, it conducts initiatives (referred to as “actions”) at the level of the individual, home, neighborhood, organization (school, healthcare), and city, targeting local political, physical, social, and health education environments within preventive and curative (i.e., children with overweight and obesity) streams. AHWA aims to reduce inequality in overweight and obesity between neighborhoods by targeting those with the highest burden;25, 26 therefore, in addition to universalist actions, at its core, the program can be understood in terms of proportionate universalism.27 In line with a WSA, AHWA works across sectors, pursuing the principle of HiAP decision‐making. HiAP implies an integrated policy response to public health issues across municipal sectors and public and private partners, recognizing the increased capacity for effective action and resulting benefit for traditionally “non‐health” policy portfolios such as transport, education, or welfare.28

AHWA is organized in thematic working clusters (e.g., school, environment, neighborhood and community, curative approaches) in which community‐supported actions are developed and implemented by AHWA or commissioned to private and community organizations. AHWA encompasses established programs such as the school‐based JUMP‐in program,29, 30 as well as community‐supported actions such as one‐day festivals focused on specific issues (e.g., healthy meal planning). Twelve individual‐level behavioral goals for diet, sleep, physical activity, and sedentary behavior are communicated to the public and support the objective of achieving a higher proportion of children with a healthy weight through behavior change.

AHWA is linked to routine data from Youth Health Care registrations, enabling use of annual city‐wide data to identify groups for targeted action (e.g., those with the highest burden of overweight and obesity, by sex, socioeconomic status [SES], age, ethnicity, and neighborhood) and monitoring long‐term outcomes at city level (e.g., number and distribution of children meeting behavioral goals). Program‐level data (e.g., participation rates, network building) are also used to monitor program performance against implementation and impact targets. This information feeds into experimentation and incremental learning to enable a responsive form of action development, informed by evidence‐ and practice‐based knowledge. More information can be found at https://www.amsterdam.nl/sociaaldomein/blijven‐wij‐gezond/ or for example.31, 32

2.1. Logic framework development: Data collection

A logic framework outlines program components in order to identify program resources, actions, and expected outcomes intended to achieve stated objectives; it can be used to inform program planning, implementation, and evaluation. A theory of change is the articulation of the causal model (and accompanying assumptions) underpinning the program. In this study, a logic framework was developed to articulate the WSA working principles of AHWA in order to inform program development, monitoring, and evaluation and contribute to the literature. Methods were designed around previous examples of developing logic frameworks and models for public health program.20, 33 The framework was developed initially in 2019, after AHWA's initiation (in 2012) but during program implementation (from 2013) and prior to formal program evaluation; the framework could therefore inform the continual development monitoring and evaluation of the 20‐year program. The framework was developed in four stages:

Formalize AHWA's vision of anticipated program success (i.e., program objectives)

Articulate the overarching theory of change

Develop a program logic framework articulating WSA working principles and components underpinning AHWA

Provide an illustrative example of operationalization of the logic framework using selected program actions

In order to develop the framework, information on AHWA was gathered by an external researcher (AS) from extensive document review of program material, including target documents, implementation and work plans, output monitors, annual reports, aggregated performance monitors, and external (inter)national reports on AHWA. An external, independent research report on the core characteristics of the program in terms of funding, design, and implementation was a key source of information.25 Data on AHWA were collected between November 2018 and April 2019, during program implementation; any relevant program documentation published after April 2019 was identified by the authors for inclusion (i.e., 19). Discussions between external researchers (AS, KS) and AHWA team members (including KdH, AV, VB) sense‐checked extracted data and ensured all appropriate materials were accessed. Discussions were also used to document additional detail and definition of program actions and timelines and identify less tangible strategic actions (e.g., cultivating and nurturing cross‐sectoral collaboration, strategic management) which may not be listed in program material. A full list of materials can be made available upon request to the corresponding author; many of these materials are publicly available at https://www.amsterdam.nl/sociaaldomein/blijven‐wij‐gezond/ (the results of this study will also be disseminated using this website).

2.2. Logic framework development: Data analysis

Data on the program were classified as follows: whole‐system attributes, inputs, processes, outputs, short‐term outcomes, intermediate outcomes, or impact. It was anticipated that in future evaluations, outcomes across the whole system (cascading across different levels such as child, household, environments, and policy) would be captured using these classifications.

Backward and forward processes allowed progressive integration of collected data into a framework. Aforementioned staggered discussions between external researchers (AS and KS) and AHWA team members enabled the authors to refine, review, and achieve consensus on the framework. Finally, for illustrative purposes, the framework for the whole program was operationalized for a single example: actions targeting sugar intake which were implemented between 2010 and 2018 (encompassing initiation of AHWA in 2012). Details for specific actions targeting sugar intake were obtained from AHWA team members and program documentation. In practice, program staff will operationalize the logic framework for multiple process and impact outcomes; there was neither the space nor resources to do this here, so a single illustrative example is provided.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Vision of program success

The vision of AHWA success was articulated as: targeted, sustainable, and responsive action delivered across municipal sectors and partners to create environments which stimulate norms and behaviors for equitable healthy weight maintenance throughout childhood, reducing levels of childhood overweight and obesity and inequalities herein in Amsterdam in the long term. This vision of success was underpinned by an overarching theory of change which was further articulated in the logic framework.

3.2. Overarching theory of change

The theoretical basis of AHWA was observed as drawing on three conceptually complementary theoretical positions. First, Hawe et al.'s conceptualization of systems change poses intervention as an event in a complex adaptive system of factors, rather than an introduction into the system.34 Such an event, or series of events, can target specific factor(s) in the system, the interactions between factors or the function of the system as a whole in producing outcomes, ultimately leading to system transformation.34 Second, the complex adaptive system in which AHWA operates is conceptualized using a multilevel model of health adapted from Dahlgren & Whitehead's model,24 acknowledging the influence of political, economic, physical, social, and individual factors on children's health behavior and outcomes. Third, change within the system of influences on overweight and obesity is conceptualized as facilitating behavior change using the COM‐B model of behavior change; this states that capability, opportunity, and motivation to perform a behavior are requisite for behavior change; both automatic and reflective psychological processes are considered to underlie individual behavior.35

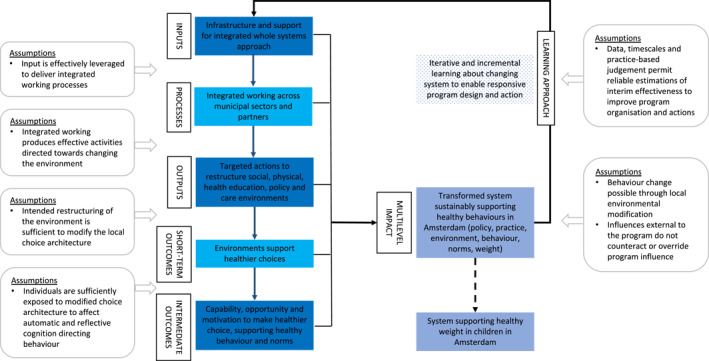

Figure 1 shows the overarching theory of change for AHWA, specifying “inputs,” “processes,” “outputs,” “short‐term outcomes,” “intermediate outcomes,” and “multilevel impact.” It was hypothesized that policy infrastructure and support for a WSA (inputs) permits integrated, cross‐sectoral working (processes) to deliver targeted action (outputs) to elicit changes in the local environment (short‐term outcomes), which increases children's exposure to health‐promoting environments (intermediate outcomes) and facilitates sustainable behavior change through improved capability, opportunity, and motivation (individual level impact) and a transformed system underpinning childhood weight in Amsterdam (multilevel impact). Assumptions underlying the theory of change are presented in Figure 1 and will need to be substantiated through future program evaluation.

FIGURE 1.

Overarching theory of change. Terms included in the figure are defined in Table 1

The local environment is conceptualized as five domains: social (e.g., social norms, social support, parental and cultural attitudes, and beliefs), physical (e.g., accessibility and availability of (un)healthy foods or sports, walking, cycling and play infrastructure, or facilities), health education (e.g., knowledge, skills, resources), policy (e.g., transport, education, healthcare, and commercial policy), and healthcare (e.g., care pathways for the identification and clinical treatment of children with overweight or obesity). The health education environment has been conceptualized as an environmental domain rather than an individual domain as it pertains to health‐related information and resources available in the child's environment (e.g., parental skills, educators' knowledge, caregivers' resources).

Incremental transformation of the system underlying healthy weight in Amsterdam is achieved through “multilevel impact” at the level of policy (resources and support for integrated, cross‐sectoral working processes), practice (sustained action to create healthier environments), local environments (fewer barriers to health‐promoting norms and environments), and the individual (healthier behaviors supported by the environment).

Progress toward incremental system transformation is enabled by an analytical “learning approach” whereby AHWA creates a continuous feedback loop between practice, policy, and academic research. Hereby, it aligns contemporaneous data at city‐ and program‐level to learn about program effectiveness and design. This includes information on individuals (e.g., weight, behaviors, inequalities across groups), environments (e.g., healthy menu provision), practice (e.g., coordination of community events around healthy behaviors, training for professionals), and processes (e.g., stakeholder networks). This learning continuously feeds back into the program as “inputs” to inform responsive action and future iterations (“phases”) of program design.

The learning approach—supported by program leadership—is delivered by several specific teams. For example, the Excellence of Professionals Team focus on development of professionals and influencing curricula and organizations that educate them. The Research and Development Team is formed of researchers who act as knowledge‐brokers for the AHWA in connecting science, practice and policy and work in close collaboration with several knowledge institutes. Outcome monitors using city‐wide data collected by the municipality (within AHWA, or existing municipal data collection such as Youth Health Care registrations) and data from the Sarphati cohort (https://sarphaticohort.nl), monitor behavioral and weight outcomes by SES, age, sex, ethnicity, and neighborhood. Program data comes from implementation monitors collecting information on the implementation and reach of actions, with input from AHWA practitioners. Responsive changes to the program are captured in multiannual implementation plans and can also lead to changes in data collection procedures (e.g., collection of newly relevant data).

Ultimately, this recursive learning and responsive action is how the program moves towards sustainable alignment of a system which supports healthier behavior and environments for children in Amsterdam. An example of responsive adaption was the later addition of sleep as a targeted behavioral outcome, following information from academic partners, AHWA practitioners, and municipal data on its relevance to health in children and older children in Amsterdam. Such information was gathered due to development in academia, but also as an emergent realization due to other work within AHWA observing the lifestyles of children. The inclusion of sleep led to collaboration with new municipal partners.

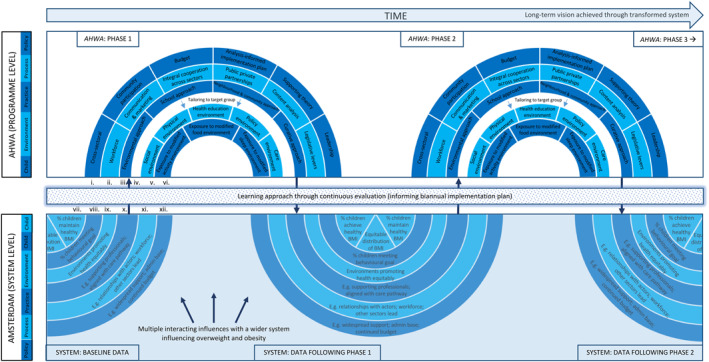

3.3. Dynamic logic framework

The logic framework presented in Figure 2 translates the overarching theory of change to program logic for instigating systems change, that is, multilevel, integrated, and responsive action within a complex adaptive system influencing overweight and obesity. Individual components of the logic framework are defined in Table 1. The logic framework (Figure 2) depicts AHWA in a dynamic form as a “wave” to reflect continual feedback between the program (upper wave) and the wider system of the Amsterdam context (lower wave) through the program's learning approach. In line with the overarching theory of change (Figure 1), the program (upper wave) is depicted as—from the outer arc inwards: policy infrastructure and support for a WSA (input), integrated program processes, cross‐sectoral practice outputs, environmental outcomes, and individual outcomes. System components (lower wave) illustrate multilevel impact in Amsterdam (at the level of: policy, processes, practice, environment, and the individual) and are conceptualized as being influenced by both program action and wider external factors in the Amsterdam context.

FIGURE 2.

Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach (AHWA) logic framework. Depicted program phases are a snapshot of continuous action at the program level. Data on changes in the system (due to the program and other, external influences) are likewise collected as snapshots of a continually evolving complex adaptive system. Snapshots of the program and system are sequential (here: 1–3 for the program and baseline‐2 for the system) as data from the previous snapshots inform the next phase of the program. The program and system level are depicted separately for the purposes of clarity; in reality, the program is embedded within the wider system. Upper wave (corresponding to boxes in the theory of change): (i) inputs at policy level, (ii) processes at program level, (iii) outputs at practice level, (iv) targeting of action to vulnerable groups, (v) short‐term outcomes at environmental level, and (vi) intermediate outcomes at individual level. Lower wave (corresponding to impact box in the theory of change): (vii) impact on individual health, (viii) impact on individual behavior, (ix) impact on environments, (x) impact on practice, (xi) impact on processes, and (xii). impact on policy infrastructure and support

TABLE 1.

Characterization of logic framework components in AHWA

| Component | Characterization in AHWA | Example in AHWA |

|---|---|---|

| Components are necessary and stable across the program life‐course | Characterization of components is stable across the program life‐course but viewed as varying between WSAs, depending on program coordinators, context and scope | Illustrative example of operationalization in AHWA 25, 31, 36, 37 |

| Inputs at policy level: Infrastructure and support for a cross‐sectoral WSA | ||

| Cross‐sectoral working | Remit for collaboration across municipal sectors; encouragement for other sectors to lead action where appropriate | Interdepartmental responsibility for addressing childhood overweight and obesity; first program plan written by official from municipal departments of Social Development. Employment, Sport, Participation and Income, and the Public Health Service |

| Community participation | Working with local communities and community leaders to prioritize and endorse actions | Working with local partners, local businesses, community leaders, religious leaders, and other neighborhood citizens |

| Budget | Budgetary commitment for >20 years, permitting appropriate timeframes to achieve impact and adopt learning approach | Ear‐marked budget for integrated approach over 20 years. Budget in 2019 of €4.6 million; budget split between the municipality and the national government |

| Analysis‐informed implementation plan | City‐level data informs multiannual implementation plans and program design | Outcome monitors using city‐wide data collected by the municipality and cohort data from Sarphati Amsterdam, monitors behavioral and weight outcomes by SES, age, sex, ethnicity, and neighborhood. Implementation monitors collect information on implementation |

| Supporting theory | Programmatic WSA informed by complex adaptive system theory. Program's long‐term vision achieved through transformed system supporting healthy behavior in Amsterdam | Development of logic framework articulating complex adaptive system theory28 and intervention development informed by Dahlgren & Whitehead's socio‐ecological model of health24 and the COM‐B model of behavior change35 |

| Leadership | Political–administrative basis with central and local leadership to facilitate an integrated approach; strategic change management with reach across executive, political, and administration actors | Administrative leadership from the Alderman for Care and Welfare. Official program leadership from the program manager, with broad municipal experience and expertise. Program management requires expertise in strategic change management (e.g., interrogation of existing processes) and short lines of communication across municipal sectors and with the Alderman |

| Processes at program level: Integrated working across municipal sectors and partners | ||

| Workforce | Motivated and knowledgeable professionals in municipality and in partner organizations | 80 program staff (approx. 55 full‐time equivalent);>200 trained health ambassadors in neighborhoods; >500 affiliated healthcare/youth professionals |

| Communication and marketing | Advocating the program through clear communication to stakeholders; positive and inclusive program materials for public awareness | AHWA corporate identity tailored to different target groups and intermediaries. Simple language, graphics, and mottos are used to strengthen the recognition of the program objectives, purposefully focusing on child, family, and community health rather than weight |

| Integral cooperation across sectors | Transparent collaboration across municipal sectors | AHWA actions embedded in other municipal organizations when stringent conditions are met, currently: actions for healthier urban design are covered by Active City program in the City Planning and Sustainability unit and actions in the digital approach and healthcare innovation is embedded in the Public Health Service (GGD) |

| Public–private partnerships | Establish collaborative, clearly defined working agreements with public and private organizations/stakeholders | Objective (2018–2021) for at least 48 businesses in Healthy Amsterdam Business Network, including large and small retailers |

| Content analysis | Intervention development and identification of target groups | Intervention development and identification of target groups in collaboration with Sarphati Amsterdam and knowledge institutes, using biannual reviews reporting city‐level and cohort data and supported by original research |

| Legislative levers | Ability to shape or effectively advocate relevant local, national, and European subsidies, frameworks, laws, rules, and policies | AHWA worked with “Stop Unhealthy Food Marketing to Kids Coalition,” achieving a ban on marketing in sports events. Lobbying the food industry and working with national government for legislation on marketing and food formulation or product sizing are AHWA objectives |

| Outputs at practice level: Delivery of actions to restructure environments conducted in thematic working clusters | ||

| Environment approach | Action to modify physical, social, and health education environments at the level of the city, neighborhood, and family. | Fifty additional water fountains; 14 healthy sports canteens; 67 healthy school playgrounds; all new developments or re‐developments built in accordance with healthy planning guidelines. |

| School approach | School and day‐care policies and programs | One hundred and twenty JUMP‐IN schools reaching 25,000 children; Four primary schools for children with additional educational needs participating in AHWA |

| Neighborhood and community approach | Action with neighborhood‐based organizations, for example, sports clubs, religious institutions, community organizations and workplaces | Eleven neighborhoods have signed a local Healthy Weight Pact; 300 local health ambassadors highlight AWHA |

| Curative approach | Professionals in care and welfare providing linked‐up care pathway for children with, and infants at increased risk of, overweight or obesity | Establishment of network with maternity care, midwives, youth healthcare and parent and child teams; 130 pediatric nurses trained in AHWA approach; collaboration with Youth Health Care Service to identify children with overweight and obesity |

| Targeted action for vulnerable groups (identified via learning process) | ||

| Tailoring or targeting, unless a universalist approach is taken | Identification of groups for tailored or intensified action, by SES, ethnicity, sex, age, additional needs, or neighborhood, adopting a proportionate universalist approach. | Action tailored for the following groups: 0–2 year‐olds, 12+ year‐olds, children with special educational needs, children in ethnic groups with highest levels of overweight and obesity and children in lowest socioeconomic groups and neighborhoods |

| Short‐term outcomes at environment level: Environments support the capability, opportunity, and motivation to perform healthy behaviors | ||

| Social environment | Modified attitudes, beliefs, and perceived norms | To be evaluated following the development of indicators, guided by the logic framework |

| Physical environment | Modified indoor and outdoor built and natural environments | |

| Health education | Improved accessibility of evidence‐based written materials, or knowledge‐ and skills‐based training; reduced accessibility to marketing for unhealthy behaviors aimed at children | |

| Policy environment | Improved implementation or reformulation of relevant local, national, and European subsidies, frameworks, laws, rules, and policies | |

| Care environment | Improved care pathways for children with overweight and obesity, from identification to treatment | |

| Intermediate outcomes at individual level: Capability, opportunity, and motivation to make healthier choice | ||

| Exposure to modified activity, food, and sleep environment | Physical, social, health education, policy, and care environments modified through action to support physical activity, healthy diet, and sleep | To be evaluated following the development of indicators, guided by the logic framework |

| Multilevel impact to sustainably transform the system supporting healthy behaviors | ||

| Impact on policy infrastructure and support | Support for health‐promoting environments across stakeholders (municipal, private, and public); politically legitimated and scientifically validated program approach and theoretical basis | To be evaluated following the development of indicators, guided by the logic framework |

| Impact on processes | Establish cross‐sectoral cooperation to achieve HiAP | |

| Impact on practice | Networks, actors across settings, and organizations deliver action to encourage healthy behaviors and discourage unhealthy behaviors | |

| Impact on environments | Physical environment increases capability, opportunity, and motivation for healthy behaviors: Information resources enable informed‐decision making; norms of attitudes, beliefs, and perceived peer behavior motivate healthy behavior; all children with overweight/obesity in care with central providers | |

| Impact on individual behavior | Higher percentage of children meeting AHWA behavioral goals, higher rate of increase in target groups | Between 2012/13 and 2014/15 breastfeeding rates increased and in primary school children: Intake of breakfast, vegetables and fruit, daily exercise, and sports club membership significantly increased; and snacking, sugary drink intake, and sedentary time decreased; differences were reported by sex. Contribution to effects from AHWA will be ascertained from evaluation guided by the logic framework |

| Impact on individual health | Higher percentage of children with a healthy BMI | 18.7% children with overweight and obesity in 2017 (falling from 21% in 2012); however, differences in effect were found by age, ethnicity, and sex. Contribution to effect from AHWA will be ascertained from evaluation guided by the logic framework |

| Whole‐systems working principles | ||

| Responsive adaptation | Learning approach integrated in the design of the program; consideration of need to respond to influences external to the program | AHWA Research and Development Team and practitioners use city‐ and program‐level data on weight and behavior (stratified by age, SES, ethnicity, neighborhood) and implementation to inform biannual implementation plans. Examples of adaptation include gradual shifts in focus on: 0–2 year‐olds and 12+ year‐olds (from 4–12 year‐olds), community participation (e.g., local health ambassadors, engagement with local religious leaders), health education in schools, and modified training curricula for new teachers, physical education professionals, dieticians, and youth workers |

| Multilevel action | Outputs at practice level through action in the: environment, school, neighborhood and community, and curative approaches | See relevant components above |

| Cross‐sectoral working | Input at policy level through “cross‐sectoral working” and process at program level through ”integral cooperation across sectors,” ”public private partnerships,” and “content analysis” | See relevant components above |

Abbreviations: AHWA, Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach; SES, socioeconomic status; WSA, whole‐systems approach.

The program is initially informed by city‐level data assessing the “baseline” system of influences on overweight and obesity in Amsterdam, for example, baseline policies, practices, or environments which influence childhood weight. The first phase of the program is an event in the system which aims to achieve change at every level in the lower wave. Resultant changes in the system are acknowledged by the learning approach using data at city level and program level (as previously described). This informs the second phase of program action and/or program design. For example, the learning approach may identify groups with the highest levels of overweight or obesity, environments which promote unhealthy behaviors, or unintended consequences of action and thereby inform continued or adapted action. Likewise, program monitoring identifies opportunities to improve, alter or scale‐up specific actions, enabling an experimental and responsive approach to action development.

Importantly, while the content or organization of components in the framework can vary across phases, the WSA working principles (and underlying assumptions) governing AHWA are standardized and stable throughout the life‐course of the program. Together, these principles pertain to the development and implementation of multilevel action through integrated, cross‐sectoral working, and conceptualization of the program as indivisible from, and responsive to, the complex adaptive system in which it operates. Furthermore, although the wave presents the phases of the program as a regular wave, it is worth noting that in practice the wave manifests more irregularly due to disruptions and unexpected influences on program implementation, and the depicted phases are a snapshot of a continuous program and contextual system.

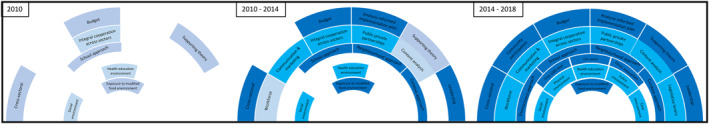

The logic framework is operationalized in Figure 3 using example AHWA actions targeting sugar intake. In the interest of clarity, only program‐level adaption is illustrated, rather than contemporaneous change in the system which induced program‐level adaptation, or resulted from program action. When introduced, the program absorbed existing activity in Amsterdam around reducing sugar intake (a snapshot of which is provided for 2012): the school‐based JUMP‐IN program stimulated school nutrition policy,29, 30 and cross‐sectoral cooperation was established between the municipal Department of Sports and the Public Health Service.

FIGURE 3.

Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach (AHWA) responsive evolution informed by the learning approach: actions conducted between 2010 and 2018 to reduce sugar intake, before and after formal initiation of the program in 2012. Presentation of components at each phase indicates implementation of action; darker shading implies greater intensity of action

Between 2013 and 2014, formal initiation of AHWA provided, among other things: increased budget, centralized leadership, and strategic management of AHWA, engagement with WSA working principles as a basis for program delivery, a dedicated program workforce, a centralized communications team and Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) with healthcare providers. These changes in policy and process would permit targeted action around sugar intake. The learning approach informed the decision to include multibehavioral targets in action development and prescribed implementation of actions in schools, neighborhoods, and the care environment, for example, delivery of JUMP‐IN as an all‐or‐nothing program prohibiting cherry‐picking while also promoting leadership from schools. Multibehavioral targets in action development and JUMP‐IN delivery meant that actions could target sugar intake alongside other diet and physical activity behaviors.

Between 2014 and 2018, as planned and based on city‐level data, AHWA gradually shifted its attention to 0–2‐year‐olds and 12+‐year‐olds instead of having a main focus on primary school‐aged children (4–12‐year‐olds). New insights from city‐level data, practice, policy, and (complex systems) science also stimulated: a focus on community participation (e.g., local health ambassadors), expansion to target the health education environment in schools and more structural research to guide program development and evaluation. In line with this, the theoretical conceptualization of AHWA as operating within a complex adaptive system was further integrated and communicated in program plans and materials through strategic program management and collaboration with academic partners and Sarphati Amsterdam. In addition, continued effort was directed towards: new private partner networks (e.g., a healthy entrepreneur network to innovate healthier food and drink retail environments), professional development (e.g., integrating the AHWA message in professional training opportunities for teachers, dieticians and health professionals), strengthening cross‐sectoral practice to implement HiAP (for example, an alliance against marketing unhealthy food products to children, allowing only healthy food offerings at municipality‐supported sports events. This was facilitated by established cooperation between the municipal Department of Sports and Public Health Service and a stronger corporate brand for AHWA communications.

Such changes permitted further action, outputs, and outcomes related to sugar intake. By this period, the following outputs were achieved: 50 additional water fountains installed in public spaces, 1734 healthy eating consultations, 2 published neighborhood recipe books, 300 health ambassadors to promote healthy lifestyles, 14 healthy sports canteens, 11 neighborhoods committed to a joint Healthy Weight Pact including objectives to reduce sugar intake, 25,000 children attending schools participating in the JUMP‐IN nutrition policy, and a ban on unhealthy marketing to children at sports events. AHWA data showed that between 2012/13 and 2014/15 there was a significant increase in the number of 10‐year‐olds drinking no more than two glasses of sugary drinks/day (61% to 72%); a similar trend was observed in 5‐year‐olds but was not statistically significant (65% to 75%). More recent data for the city of Amsterdam suggest the number of children meeting this target continues increase, but statistical significance has not been tested: in 2017/18, 86% of 10‐year‐olds and 89% of year‐olds drank no more than two glasses of sugary drinks/day (https://amsterdam.ggdgezondheidinbeeld.nl).

4. DISCUSSION

AHWA, termed “the Dutch Approach,”32, 38, 39 is a long‐term, municipality‐led WSA to reducing childhood overweight and obesity in Amsterdam. Based on extensive document review and discussion, a dynamic logic framework was developed to articulate, for the first time, the working principles of AHWA and inform program development, monitoring, and evaluation. This is a novel contribution to the literature in that it formally describes the program logic—from problem identification to program implementation and development—of an WSA to obesity prevention which embodies the three working principles of an WSA: multilevel action, cross‐sectoral working, and responsive adaptation.8

The AHWA logic framework builds on previous models for multilevel approaches, such as the EPODE logic model,33 by embracing the dynamism of WSAs through the adoption of a collaborative learning approach. In doing so, it is able to articulate the theorized unfolding of a real‐world WSA and how it might achieve multilevel impact: from healthier childhood behaviors to wider practice of HiAP or effective use of PPPs. What it adds to previous models is in particular the articulation of responsive adaption (through a learning approach) as a core working principle (alongside multi‐level action and cross‐sectoral working) and representation of the relationship between the program and the system in which it operates. Further research is needed to ensure the framework is valid and sufficiently robust as the program evolves and to test program fidelity to WSA principles presented in the framework.

The scope of this research was to specify the logic underpinning AHWA and not to provide detailed description of unique aspects of the program. Other WSAs will be different in their characterization and operationalization; for example, specific political conditions or the content of actions will diverge across contexts and populations. In this respect, we provide limited information on the unique aspects of AHWA development and design. Instead, we address calls in the literature for explication of the theoretical function and practical basis of WSAs such as AHWA.8, 40

Development of the AHWA logic framework underscores working principles of a WSA that necessitate novel approaches to program design, implementation, and evaluation (as alluded to in the Introduction).

-

1)

As a series of events in a complex adaptive system (i.e., the local context), AHWA is indivisible from a complex system which is in a state of constant adaption to influences from AHWA and external factors. Therefore, the program must evolve in response to a changing system and program effectiveness cannot be examined in isolation from the system

-

2)

As a result, while the type of available program actions is relatively stable (i.e., actions to modify the environment), the specific content and implementation of actions is not a predetermined, stable “treatment” to which participants are exposed. Methods used to design and evaluate WSAs should acknowledge this non‐linearity and unpredictability23

-

3)

Relatedly, as WSAs are designed to target specific systems of factors influencing childhood overweight and obesity, generalization to other contexts may be difficult41

Consideration of these challenges is necessary to respond to wider calls for the design, evaluation, and scaling of WSAs to reduce overweight and obesity and other public health issues.40 We address each of these points in turn. Firstly, owing to the integration of program and context, we believe program evaluation should focus on its contribution to system change rather than attempting to attribute direct causality. Expected contribution is established from a well‐reasoned theory of change defining iterative and long chains of events which can be progressively verified: actions were implemented (outputs), leading to environmental change (short‐term outcomes), to which individuals were exposed (intermediate outcomes) and modified their behavior (impact).42

The AHWA logic framework supports the operationalization of program components in a specific logic model, enabling the development of relevant monitoring indicators to assess changes in policy, practice, and local environments. In doing so, it is possible to ascertain, in sufficient resolution, AHWA's contribution to system change, compared with the contribution of external action. Mixed‐methods will be valuable in ascertaining contribution: while qualitative data can highlight program actions and external influences, quantitative data can help to assess whether the expected contribution from program action is achieved. Qualitative systems mapping using iterative causal loop diagramming also provides opportunities embedded in a systems perspective.10, 16

This is a substantial divergence from traditional epidemiological methods of evaluation and does not guarantee the same degree of certainty in ascertaining impact using effect size and confidence intervals. However, in viewing obesity as an emergent outcome of an obesogenic complex adaptive system (encompassing micro, meso, and macro environments), it is entirely plausible that WSAs are best able to achieve sustainable changes to the system; we posit that traditional methods are not applicable to the evaluation of WSAs and the research community must develop and refine suitable methods. The Lifestyle Innovations based on youths' Knowledge and Experience program is associated with AHWA and aims to use developmental evaluation and iterative causal loop diagramming to understand the contribution of actions implemented by AHWA within selected neighborhoods in the east of Amsterdam.16

Second, appropriate timeframes are needed to acknowledge program evolution and permit realization of effects along long causal chains including short‐term and intermediate outcomes.43 Movement towards a long‐term view of achieving impact through WSAs must be teamed with adequately monitored and resourced action.44 The AHWA logic framework acknowledges the importance of political and budgetary input as well as city‐wide program support and data availability that enables measurement of all relevant factors across appropriate timeframes. As program content is neither stable nor predetermined, WSA working principles become a greater focus for evaluation. Articulation and specific operationalization of working principles (such as responsive action via a learning approach) is necessary to guide evaluation and delineate hypothesized long causal chains.

Third, generalization of WSAs should focus on program effectiveness in terms of both content and function. The latter pertains to generalizing effective working principles and methods (e.g., successful ways to achieve and apply cross‐sectoral working) which, in isolation or combination, have a function to contribute to system change. For example, while PPPs might be used to encourage intake of healthy snacks at sport events (function), the content of the action will be specific to the system in which it operates. In one system (city A at time‐point 1), PPPs with local sports clubs may inform city‐wide policy on healthy snack provision and help to promote healthy social norms by only admitting healthy retailers in sports clubs. In another system (city A at time‐point 2, or city B at time‐point 1), PPPs with local food retailers may be used to reach retailers in a targeted neighborhood to initiate a local competition for the healthiest retailer. In both instances, function is the same while content (i.e., components of the intervention) differs. In AHWA, articulation of and commitment to WSA working principles for problem definition and program design and evaluation provides opportunities for mid‐range generalizability of effective working principles and methods, despite their manifestation as system‐specific action. Indeed, an AHWA objective for 2018–2021 is to create a learning network of ≥4 other (inter)national cities which intend to reduce health inequalities using WSAs. In collaboration with knowledge institutes, this network will share learning and challenges around these approaches.31

The logic framework can be used to formulate relevant research questions on the effect of WSAs on system change. Using the aforementioned examples: to assess effectiveness of program actions (content), program‐level data could be used to test an effect of a healthiest retailer competition on unhealthy snack intake at sport events. To assess contribution of program actions to system change (i.e., function), program‐level data can be used to progressively verify long causal chains: engagement of sport clubs (processes), admittance of healthy snack retailers in sport clubs (output), changes in social norms for healthy snack intake (short‐term outcome), and available food choices at sports clubs (intermediate outcome). Understanding whether unintended consequences or external influences suppressed effects (e.g., sales of unhealthy snacks outside sport club gates) is also of consequence. In this example, evidence of multilevel impact on the system could be assessed using city‐level data: widespread support for PPPs (political infrastructure and support), sustained PPPs (processes), type of retailers at all sport clubs (practice), increased city‐wide social norms and healthy food provision (environments), healthier food choices at sport events (individual behavior), lower levels of overweight and obesity (individual health).

This study addresses a gap in the literature by describing a real‐world WSA to prevent childhood overweight and obesity.8 The AHWA logic framework also enables the operationalization of program theory and thereby facilitates (i) gap analysis of current actions, in order to inform program development and (ii) the formulation of testable hypotheses, in order to inform program monitoring and evaluation, within the context of declining childhood overweight and obesity prevalence in Amsterdam.19

There is keen international interest in using WSAs to achieve sustainable systems change36 and in AHWA as a program.32, 38, 39 The current research contributes to a paradigm shift in how public health issues are defined and targeted by communicating the underpinning the whole‐systems logic of this innovative, real‐world WSA.21, 43, 45 Rigorous evaluation of the standardized AHWA working principles will further contribute to the field. Future research on WSAs should be bold and communicative in finding ways to design, implement, evaluate, and generalize such approaches which embrace, rather than eschew, the complexity of the contexts in which public health issues persist.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have completed the ICMJE COI disclosure form (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: Alexia Sawyer, Karen den Hertog, Arnoud P Verhoeff, and Vincent Busch had financial support from Public Health Service (GGD), City of Amsterdam, for the submitted work; Karien Stronks received no specific funding for the submitted work. Public Health Service (GGD), City of Amsterdam, is a governmental organization; as the submitted work articulates the development and implementation of an existing program, the interests in the outcome of the work is low. Authors had no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 36 months and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Alexia Sawyer conducted the initial document review, and all authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results of the review. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and reviewed the final version.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Wilma Waterlander, Janneke Harting, Amanda Burke, and Alice Dalton for their thoughtful comments on previous versions of this manuscript. We would like to acknowledge everyone who has co‐created, worked on or otherwise contributed to the Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach since 2012; we are grateful for their dedication, passion, critical thinking, innovative ideas, and their direct or indirect input into this manuscript. Alexia Sawyer, Karen den Hertog, Arnoud P Verhoeff, and Vincent Busch had financial support from Public Health Service (GGD), City of Amsterdam, for the submitted work.

Sawyer A, den Hertog K, Verhoeff AP, Busch V, Stronks K. Developing the logic framework underpinning a whole‐systems approach to childhood overweight and obesity prevention: Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach. Obes Sci Pract. 2021;7(5):591‐605. doi: 10.1002/osp4.505

Alexia Sawyer and Karen den Hertog are joint first authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell MK. Biological, environmental, and social influences on childhood obesity. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:205‐211. 10.1038/pr.2015.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brug J, Chinapaw M. Determinants of engaging in sedentary behavior across the lifespan; lessons learned from two systematic reviews conducted within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:134. 10.1186/s12966-015-0293-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Millbank Q. 2009;87:123‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black JL, Macinko J. Neighborhoods and obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:2‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meadows D. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Sterling, VA: Earthscan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butland B, Jebb SA, Kopelam P, et al. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project Report. London: UK Government Foresight Programme; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGlashan J, Hayward J, Brown A, et al. Comparing complex perspectives on obesity drivers: action‐driven communities and evidence‐oriented experts. Obes Sci Pract. 2018;4:575‐581. 10.1002/osp4.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagnall AM, Radley D, Jones R, et al. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: a systematic review. BMC Publ Health. 2019;19:8. 10.1186/s12889-018-6274-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garside G, Pearson M, Hunt H, et al. Identifying the Key Elements and Interactions of a Whole System Approach to Obesity Prevention. London, UK: Peninsula Technology Assessment Group for National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allender S, Millar L, Hovmand P, et al. Whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity: WHO STOPS childhood obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1143. 10.3390/ijerph13111143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Local Government Association . Childhood Obesity Trailblazer Programme. London, UK: Local Government Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health Engaland . Whole Systems Approach to Obesity: A Guide to Support Local Approaches to Promoting a Healthy Weight. London, UK: Public Health England; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009002. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sautkina E, Goodwin D, Jones A, et al. Lost in translation? Theory, policy and practice in systems‐based environmental approaches to obesity prevention in the Healthy Towns programme in England. Health Place. 2014;29:60‐66. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerritsen S, Harré S, Swinburn B, et al. Systemic barriers and equitable interventions to improve vegetable and fruit intake in children: interviews with national food system actors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterlander WE, Pinzon AL, Verhoeff A, et al. A system dynamics and participatory action research approach to promote healthy living and a healthy weight among 10‐14‐year‐old adolescents in Amsterdam: the LIKE programme. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organisation . Consideration of the Evidence on Childhood Obesity for the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: Report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Science and Evidence for Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen LS, Danielsen KV, Sørensen TIA. Short sleep duration as a possible cause of obesity: critical analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Obes Rev. 2011;12:78‐92. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gemeente Amsterdam . Factsheet July 2019. Weight and Lifestyle of Children in Amsterdam. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gemeente Amsterdam; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harting J, van Assema P. Exploring the conceptualization of program theories in Dutch community programs: a multiple case study. Health Promot Int. 2011;26:23‐36. 10.1093/heapro/daq045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salway S, Green J. Towards a critical complex systems approach to public health. Crit Public Health. 2017;27:523‐524. 10.1080/09581596.2017.1368249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karacabeyli D, Allender S, Pinkney S, Amed S. Evaluation of complex community‐based childhood obesity prevention interventions. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1080‐1092. 10.1111/obr.12689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore GF, Evans R, Hawkins J, et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Education (Lond). 2018;25:23‐45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Koperen TM, van Wietmarschen M, Seidell JC, Hageraats R. Amsterdamse Aanpak Gezond Gewicht (Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach): Likely to Succeed? A Search for the Valuable Elements. Amsterdam, Netherlands: The Netherlands Youth Institute; VU University Amsterdam; Cupreifere Consult; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehead M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:473‐478. 10.1136/jech.2005.037242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:81. 10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters D, Harting J, van Oers H, Schuit J, de Vries N, Stronks K. Manifestations of integrated public health policy in Dutch municipalities. Health promot Int. 2016;31:290‐302. 10.1093/heapro/dau104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Meij JSB, Chinapaw MJM, van Stralen MM, van der Wal MF, van Dieren L, van Mechelen W. Effectiveness of JUMP‐in, a Dutch primary school‐based community intervention aimed at the promotion of physical activity. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:1052‐1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busch V, van Opdorp PAJ, Broek J, Harmsen IA. Bright spots, physical activity investments that work: JUMP‐in: promoting physical activity and healthy nutrition at primary schools in Amsterdam. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1299‐1301. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gemeente Amsterdam . Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme 2018‐2021 Multiannual Programme. Amsterdam Will Become the Healthiest City for Children! Time to Get Tough! Part 1. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gemeente Amsterdam; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookes C, Korjonen H. Health Equity Pilot Project (HEPP): Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme Case Study. London, UK: UK Health Forum; European Union; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Koperen TM, Jebb SA, Summerbell CD, et al. Characterizing the EPODE logic model: unravelling the past and informing the future. Obes Rev. 2013;14:162‐170. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:267‐276. 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gemeente Amsterdam . Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme 2018‐2021 Multiannual Programme. Amsterdam Will Become the Healthiest City for Children: Review 2012‐2017. Part 2. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gemeente Amsterdam; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gemeente Amsterdam . Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme: A Compex Adaptive Systems Approach on Tackling Childhood Obesity. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gemeente Amsterdam; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldon T. Whole city working against childhood obesity. BMJ. 2018;361:k2534. 10.1136/bmj.k2534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurst D. How Amsterdam Is Reducing Child Obesity. BBC News; 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/health‐43113760

- 40.Renzella JA, Demaio AR. It's time we paved a healthier path of least resistance. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:465‐466. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant RL, Hood R. Complex systems, explanation and policy: implications of the crisis of replication for public health research. Crit Public Health. 2017;27:525‐532. 10.1080/09581596.2017.1282603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayne J. Contribution Analysis: An Approach to Exploring Cause and Effect. The Institutional Learning and Change Initiative. Netherlands; 2008.

- 43.Foster‐Fishman PG, Nowell B, Yang H. Putting the system back into systems change: a framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am J Commun Psychol. 2007;39:197‐215. 10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:505‐514. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finegood DT, Merth TDN, Rutter H. Implications of the foresight obesity system map for solutions to childhood obesity. Obesity. 2010;18:S13‐S16. 10.1038/oby.2009.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material