Abstract

Viral infections have often been associated with subacute (De Quervain) thyroiditis. Rare cases of subacute thyroiditis have been reported after vaccines. Various vaccines have been developed with different techniques against SARS-CoV-2. This case report presents a rare case of subacute thyroiditis after the inactive SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine, CoronaVac.

Keywords: thyroiditis, COVID-19, vaccination/immunisation

Background

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that caused a global pandemic. Although its destructive results continue to increase, vaccination studies have created hope for treatment. Various vaccines have been developed for SARS-CoV-2. CoronaVac, an inactivated virus vaccine, is one of them.1 Two doses of CoronaVac were first administered to healthcare workers within Turkey’s framework of the vaccination programme. Subacute thyroiditis (SAT) is an inflammatory disease that occurs secondarily to viral or postviral responses and causes damage to the thyroid gland. Cases of SAT after various vaccines have been reported.2

Case presentation

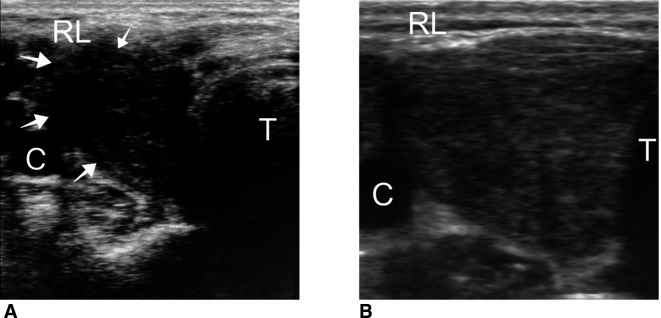

A 38-year-old female physician was admitted to the endocrinology outpatient clinic with reports of swelling in the neck, pain, fatigue, loss of appetite and sweating in the evening 2 weeks after being administered with the second dose of CoronaVac vaccine. The CoronaVac vaccine was administered on the first day and the 28th day. The patient stated that a slight pain and tenderness occurred in the thyroid lodge after the first dose, but it passed within a few days, and she did not consult a doctor during this period. The patient had no prior illness, previous vaccination or drug use. Physical examination revealed stage 2 goitre, and there was pain in the right thyroid lobe when it was touched. In laboratory tests, thyrotropin (TSH): 0.008 uIU/mL (normal: 0.27–4.2), free T3: 12.88 pg/mL (normal: 2–4), free T4: 4.65 ng/dL (normal: 0.93–1), anti-Tpo: 9.49 IU/mL (normal: 0–34), anti-Tg: 81.58 IU/mL (normal: 0–115), C reactive protein: 8.76 mg/L (normal: 0–0.8), sedimentation: 78 mm/hour (normal: 0–20) were detected. COVID-19 PCR testing was not performed as there were no COVID-related symptoms except SAT findings. Thyroid ultrasonography (USG) revealed an increased size of the right thyroid lobe, an irregularly demarcated hypoechoic area of approximately 3 cm in diameter compatible with thyroiditis starting from the capsule in the lateral and progressing into the lobe (white arrow in figure 1A). SAT diagnosis was established with a high acute phase, thyrotoxicosis and USG findings. Naproxen sodium 2×275 mg and propranolol 2×20 mg peroral treatment was initiated. Following treatment, the neck pain was alleviated. The patient stated that on the 14th day of the follow-up, her problems had mostly disappeared. The baseline and follow-up values of the patient are given in table 1.

Figure 1.

Thyroid ultrasound image taken during (A) initial stage and (B) after 45 days. RL, right lobe of the thyroid; T, trachea.

Table 1.

Laboratory results

| Measure | Unit | Reference range | 25 February 2021 | 11 March 2021 | 24 March 2021 | 8 April 2021 |

| fT4 | ng/dL | 0.93–1.7 | 4.65 | 1.34 | 0.608 | 0.78 |

| fT3 | pg/mL | 2–4.4 | 12.88 | 3.39 | 2.03 | 2.68 |

| TSH | uIU/mL | 0.27–4.2 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 24.68 | 20.9 |

| TgAb | IU/mL | 0–115 | 81.58 | |||

| TPOAb | IU/mL | 0–34 | 9.49 | |||

| White cell count | x103/uL | 4.5–11 | 10.4 | 7.9 | 8.06 | 7.98 |

| Haemogloblin | g/L | 117–155 | 107 | 111 | 110 | 113 |

| Platelet | x109/L | 150–450 | 575 | 466 | 361 | 319 |

| ESR | mm/h | 0–20 | 78 | 57 | 28 | 19 |

| CRP | mg/dL | 0–0.8 | 8.76 | 0.4 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine; TgAb, thyroglobulin antibodies; TPOAb, thyroperoxidase antibodies; TSH, thyrotropin.

Outcome and follow-up

On the 30th day, levothyroxine started to be administered at 25 μg/day due to a high TSH level (24.68 uIU/mL) and decreased free T4. As TSH was 20 uIU/mL on the 45th day, the levothyroxine dose was increased to 50 μg/day. On the 45th day, USG revealed partial recovery of the thyroid gland (figure 1B). Moreover, the patient had no reports other than the biochemical findings of hypothyroidism.

Discussion

SAT is a self-limiting inflammatory thyroid disease characterised by neck pain, fever and thyroid dysfunction.3 There is usually a history of upper respiratory tract infection before SAT. Viral agents can cause SAT with an indirect immunological reaction, and there are some reports that viruses can cause SAT by direct tissue invasion. Many viruses have been reported as potential causative agents.4 However, an evident infectious agent can rarely be demonstrated in most patients. SAT cases have been reported following the SARS-CoV-2 infection. The general features of these are similar to SAT cases reported in other aetiologies. Most of them are seen in young women; pain in the thyroid region is usually the first presenting complaint, and an increase in inflammatory markers and thyrotoxicosis have been reported in other cases.5 In SAT cases, clinical and USG findings can provide a specific diagnosis, and a radioactive iodine uptake study is often not required, as was the case in this instance.6 The patient was a young woman diagnosed with typical symptoms and SAT USG findings.

Transmembrane protease serine-2 (TMPRSS-2) and ACE-2 receptors allow the SARS-CoV-2 to enter human cells.7 8 ACE-2 and TMPRSS-2 are expressed in thyroid follicular cells, and their expression is higher than in lung cells, especially in women.9 These situations may explain why SARS-CoV-2 causes SAT in women more frequently.

Inactive virus vaccines contain many proteins belonging to the pathogen virus and similar antigenic parts.10 The increased affinity of the SARS-CoV-2 towards the thyroid suggests that this inactive vaccine may also affect the thyroid tissue. Few cases of SAT have been reported after various vaccinations in the literature. It is noteworthy that these cases are mostly seen after an inactivated virus vaccination. There are cases reported with SAT after an inactive virus vaccine: seasonal influenza vaccine,2 11 12 H1N1 vaccine13 and hepatitis B vaccine.14

Besides viral proteins, adjuvant substances used in the vaccine to increase immunological reactions may also trigger autoimmune reactions.15 The CoronaVac vaccine contains aluminium hydroxide as an adjuvant. A condition called the autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA syndrome) was previously reported following various vaccines.16 However, the CoronaVac vaccine has been related to causing the ASIA syndrome and SAT in a recent article.17

In our case, the milder thyroiditis findings after the first dose of vaccine and typical SAT findings after the second dose are noteworthy. The aetiology of SAT remains unclear in many cases, but given the typical USG image and the temporal relationship between vaccination and the onset of thyrotoxicosis, as in this case, CoronaVac can probably be associated with SAT. Therefore, clinicians should be aware that thyroid symptoms can potentially be associated with the CoronaVac vaccine; however, such a side effect should never preclude vaccination.

Learning points.

Subacute thyroiditis should be considered in a patient presenting with neck pain, fever and thyroid dysfunction.

COVID-19 is a multisystemic disease, and even an inactive vaccine can cause inflammatory reactions in extrapulmonary tissues.

Cases of subacute thyroiditis can occur after any vaccination.

Besides viral proteins, adjuvant substances used in the vaccine to increase immunological reactions may also trigger autoimmune reactions.

Clinicians should be aware of thyroid symptoms being potentially associated with the inactive SARS- CoV-2 vaccine.

Footnotes

Contributors: ESS and EK designed the case report. ESS collected the data. ESS performed the data analyses and interpretation. ESS and EK prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Doroftei B, Ciobica A, Ilie O-D, et al. Mini-Review Discussing the reliability and efficiency of COVID-19 vaccines. Diagnostics 2021;11. 10.3390/diagnostics11040579. [Epub ahead of print: 24 03 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altay FA, Güz G, Altay M. Subacute thyroiditis following seasonal influenza vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:1033–4. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1117716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishihara E, Ohye H, Amino N, et al. Clinical characteristics of 852 patients with subacute thyroiditis before treatment. Intern Med 2008;47:725–9. 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desailloud R, Hober D. Viruses and thyroiditis: an update. Virol J 2009;6:5. 10.1186/1743-422X-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron P. Thyroiditis and SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a review. Endocrine 2021;72:326–31. 10.1007/s12020-021-02689-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhuo L, Nie Y, Ma L, et al. Diagnostic value of nuclear medicine imaging and ultrasonography in subacute thyroiditis. Am J Transl Res 2021;13:5629–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rotondi M, Coperchini F, Ricci G, et al. Detection of SARS-COV-2 receptor ACE-2 mRNA in thyroid cells: a clue for COVID-19-related subacute thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest 2021;44:1085–90. 10.1007/s40618-020-01436-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazartigues E, Qadir MMF, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Endocrine significance of SARS-CoV-2's reliance on ACE2. Endocrinology 2020;161. 10.1210/endocr/bqaa108. [Epub ahead of print: 01 09 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M-Y, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang X-S, et al. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty 2020;9:45. 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roper RL, Rehm KE. Sars vaccines: where are we? Expert Rev Vaccines 2009;8:887–98. 10.1586/erv.09.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passah A, Arora S, Damle NA, et al. Occurrence of subacute thyroiditis following influenza vaccination. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2018;22:713–4. 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_237_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsiao J-Y, Hsin S-C, Hsieh M-C, et al. Subacute thyroiditis following influenza vaccine (Vaxigrip) in a young female. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2006;22:297–300. 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70315-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girgis CM, Russo RR, Benson K. Subacute thyroiditis following the H1N1 vaccine. J Endocrinol Invest 2010;33:506. 10.1007/BF03346633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toft J, Larsen S, Toft H. Subacute thyroiditis after hepatitis B vaccination. Endocr J 1998;45:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jara LJ, García-Collinot G, Medina G, et al. Severe manifestations of autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants (Shoenfeld's syndrome). Immunol Res 2017;65:8–16. 10.1007/s12026-016-8811-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bragazzi NL, Hejly A, Watad A, et al. Asia syndrome and endocrine autoimmune disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;34:101412. 10.1016/j.beem.2020.101412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.İremli BG, Şendur SN, Ünlütürk U. Three cases of subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: postvaccination Asia syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:dgab373:2600–5. 10.1210/clinem/dgab373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]