Abstract

Objectives

In alcohol intoxicated patients, the decision for or against airway protection can be challenging and is often based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Primary aim of this study was to analyse the aspiration risk in relation to the GCS score and clinical parameters in patients with severe acute alcohol monointoxication. Secondary aim was the association between the blood alcohol level and the GCS score.

Setting

Single-centre, retrospective study of alcoholised patients admitted to a German intensive care unit between 2006 and 2020.

Participants

A total of n=411 admissions were eligible for our analysis.

Clinical measures and analysis

The following data were extracted: age, gender, admission time, blood alcohol level, blood glucose level, initial GCS score, GCS score at admission, vital signs, clinical signs of aspiration and airway management measures. The empirical distribution of continuous and categorical data was calculated. Binary multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify possible risk factors for aspiration.

Results

The mean age was 35 years. 72% (n=294) of the admissions were male. The blood alcohol level (mean 2.7 g/L±1.0, maximum 5.9 g/L) did not correlate with the GCS score but with the age of the patient. In univariate analysis, the aspiration risk correlated with blood alcohol level, age, GCS score, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate and blood glucose level and was significantly higher in male patients, on vomiting, and in patients requiring airway measures. Aspiration rate was 45% (n=10) in patients without vs 6% (n=3) in patients with preserved protective reflexes (p=0.0001). In the multivariate analysis, only age and GCS score were significantly associated with the risk of aspiration.

Conclusion

Although in this single-centre, retrospective study the aspiration rate in severe acute alcohol monointoxicated patients correlates with GCS and protective reflexes, the decision for endotracheal intubation might rather be based on the presence of different risk factors for aspiration.

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, substance misuse, toxicology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We provide an analysis of the so far largest homogeneous cohort of alcohol monointoxicated non-traumatic intensive care unit patients for risk factors of aspiration.

Since the aspiration pneumonia could have developed after the discharge of the patient from the hospital in cases with short-time in-hospital care, we might have missed some aspiration events.

Since a minority of patients were admitted to the hospital more than once, we analysed admissions instead of patients as single events.

Within our cohort of limited sample size we identified risk factors for aspiration which could help to guide clinical diagnostic and therapeutic workup.

However, due to the retrospective nature of this single-centre study, we cannot provide direct clinical recommendations.

Introduction

Patients with acute ethanol intoxication frequently require medical treatment, observation and diagnostics by paramedics, emergency physicians, emergency departments as well as intensive care units (ICU).1 Up to 12% of the attendances at the emergency department of an innercity hospital in the UK were alcohol related, mostly due to acute intoxication.2 In Ontario, Canada, 5.1% of visits to the emergency department were attributable to alcohol use.3 Besides respiratory depression, an elevated risk of aspiration due to impaired consciousness after alcohol consumption can cause life-threatening complications.4 5 In patients with trauma with impaired consciousness, a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or less is widely accepted as an indication for an airway protection by endotracheal intubation.6 Although alcohol intoxicated patients often present with impaired consciousness and a GCS score of less than 8, the reported intubation rate of 0%–2.3% is low compared with the overall intubation rate of 3%–5% in prehospital emergencies.7–11 The clinical benefit of intubating intoxicated patients with a GCS score ≤8 in order to prevent aspiration is still controversially discussed.8 9 12–14 Apart from adverse events like hypotension and cardiac arrest, prehospital intubation bears a risk of approx. 8% for the development of an intubation-related aspiration pneumonia.15 Therefore, the risk–benefit ratio of prehospital invasive airway measures needs to be carefully considered. Differences of aspiration and intubation rates between mixed intoxications and alcohol monointoxications suggest that these clinical conditions might not be comparable regarding the necessity for airway protection. In contrast to mixed intoxication, data regarding airway impairment in acute alcohol monointoxication are very scarce.

The primary aim of this study was to search for risk factors for aspiration in adolescent and adult atraumatic patients who required admission to our ICU due to severe acute alcohol monointoxication. As a secondary aim, we analysed the association between the blood alcohol level and the GCS score.

Material and methods

Study design and population

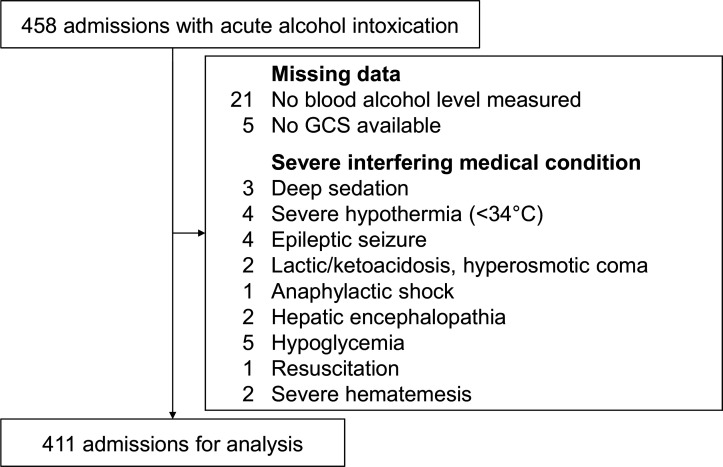

For this retrospective study, all patients who had been admitted to the ICU of the Department of Gastroenterology at the University Hospital of Heidelberg between January 2006 and December 2020 were screened for acute mono-intoxication with alcohol (ethanol). Mixed intoxication was assumed when reported by the patient or relatives or in case of indicative prehospital scenarios (empty blisters, visible injection signs) or positive toxicology screening on admission to the hospital (see the ‘Measurements’ section). These patients were excluded from the study. Alcohol intoxication was defined as impaired consciousness due to a blood alcohol level ≥0.8 g/L, which is the legal definition for alcohol intoxication in many countries.16 Patients with missing data regarding blood alcohol level or GCS score were excluded, as well as patients with severe comorbidities or medical conditions interfering with consciousness, airway situation, aspiration risk or breathing rate. Details of excluded patients are given in figure 1. Deep therapeutic sedation was defined as sedation by the emergency physician resulting in an iatrogenic GCS score ≤8. Severe hypothermia was defined by a core temperature ≤34°C. Hypoglycaemic was defined as any blood glucose level <65 mg/dL as the lower level of normal regarding our standard point-of-care-testing (POCT) devices. Concomitant use of common medication at therapeutic doses was permitted. The following data were extracted from the medical records: age, gender, admission time, blood alcohol level, blood glucose level, initial GCS score (first GCS), GCS score at admission to the hospital (second GCS), initial (prehospital) vital signs (systolic blood pressure, heart rate, breathing rate, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2)), clinical and prehospital signs of aspiration and airway management measures. When patients were prehospitally intubated, only the first GCS score before intubation was recorded, since the second GCS score was narcosis-induced (usually GCS score=3). Aspiration was rated positive if proven by bronchoscopy or if clinical suspicion was supported by at least one of the following factors: coughing up aspirate, coarse crackles on auscultation, new opacities on chest X-ray, development of fever or laboratory signs of inflammation (C reactive protein, leukocytosis) without other overt reasons. Patients without clinical signs of aspiration or normal bronchoscopy were rated negative.

Figure 1.

Composition of the study cohort. From the initial cohort of 458 atraumatic patients with acute alcohol monointoxication, 47 admissions were excluded due to missing data or severe interfering medical conditions, resulting in 411 admissions eligible for the final analysis. In three cases, two different exclusion criteria were present. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Measurements

Except for prehospital measurements of blood glucose levels by POCT according to the emergency medical service, blood samples were obtained immediately after the patient’s admission to our hospital for venous blood gas analysis (RAPIDLab 1200, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Eschborn, Germany), measurement of blood alcohol level and standard laboratory tests including glucose. When indicated by the patient’s history or clinical data, a qualitative urine toxicology screen (Triage 8 Drugs of Abuse Panel, Alere Diagnostics, Cologne, Germany) was performed to exclude mixed intoxications. This test detects the following components: amphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, methadone, opiates, tetrahydrocannabinol, and tricyclic antidepressants. Due to the low specificity, sensitivity and clinical benefit, urine toxicology test was not performed on a regular basis.17

Statistical analysis

Data entry was performed with help of Microsoft Excel (V.14.0), for the statistical analysis SAS V.9.4 WIN (SAS Institute) was used. The empirical distribution of continuous data was described with mean, SD and range, in case of categorical data with absolute and relative frequencies. Spearman‘s correlation coefficient was calculated to describe associations between blood alcohol level and laboratory values. Possible differences between patients with and without aspiration were tested with t-test for continuous data and χ2-tests for categorical data. Binary multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to find possible risk factors for aspiration. Statistical graphics were used to visualise the findings.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

A total of n=411 admissions to our ICU for acute alcohol monointoxication comprising n=360 different patients were eligible for our analysis. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients and their vital parameters are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population at admission

| Total no of admissions | 411 |

| No of different patients | 360 |

| Patients with more than one admission | 33 |

| Patients with two admissions | 21 |

| Patients with three admissions | 7 |

| Patients with four admissions | 4 |

| Patients with five admissions | 1 |

| Gender, males/females (%) | 294/117 (72%/28%) |

| Age, mean±SD, (range) (years) | 35±15 (15–74) |

| Blood alcohol level, mean±SD, (range) (g/L) | 2.7±1.0 (0.9–5.9) |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation, mean±SD, (range) (%) | 96±6 (47–100) |

| Heart rate, mean±SD (range) (bpm) | 92±20 (35–180) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ±SD (range) (mm Hg) |

121±22 (70–200) |

| Respiratory rate, mean±SD (range) (1/min) | 15±5 (0–35) |

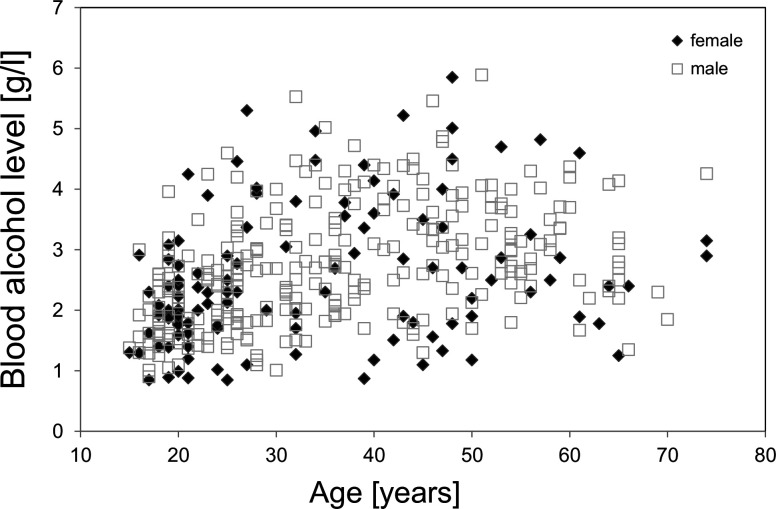

The mean blood alcohol level did not significantly differ between male (2.7±1.0 g/L) and female (2.5±1.1 g/L) patients (p=0.132). The maximum blood alcohol level was 5.9 g/L and 5.9 g/L in male and female patients, respectively. In figure 2, the blood alcohol levels are shown according to age and gender. The blood alcohol level strongly correlated with patient’s age (r=0.43, p<0.0001) in the total population, as well as in male (r=0.46, p<0.0001) and female patients (r=0.33, p=0.003).

Figure 2.

Blood alcohol levels at admission are plotted as a function of age, separately for n=294 admission of male (□) and n=117 admissions of female (♦) patients.

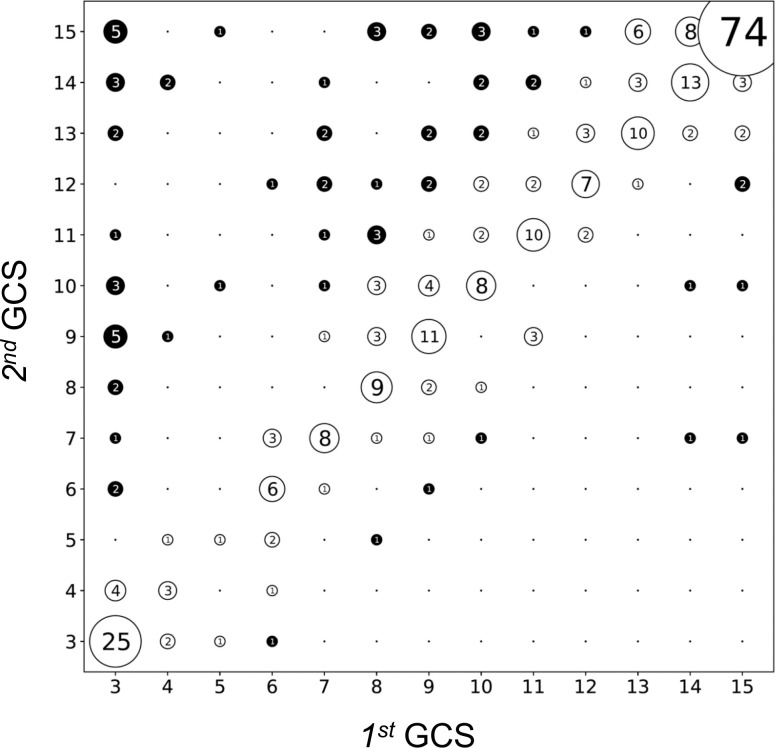

In order to analyse the fluctuating consciousness in acute alcohol intoxication, we compared the first GCS score of the patient on arrival of the emergency team with the second GCS score at admission to the hospital approximately 30–60 min later. The median GCS score improved from 10 to 13 between prehospital presentation and admission to the ICU. Figure 3 visualises the strong correlation between the first and second GCS score (r=0.77, p<0.0001). Dots on the diagonal line correspond to patients with identical first and second GCS scores. We considered a change of ±3 GCS points (ΔGCS) as clinically relevant. Most patients (n=258, 79%) did not show a relevant change of the GCS score (−2 ≤ ΔGCS ≤+2). While n=61 admissions (19%) demonstrated an improvement of their consciousness level during their transport to the hospital (ΔGCS score ≥+3), only n=10 patients (3%) showed a relevant deterioration (ΔGCS score ≤ −3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between the first GCS score at prehospital presentation and the second GCS score at hospital admission (n=336 complete data sets). The diagonal represents patients with no change in GCS score during their prehospital treatment. The number of patients is inscribed within each dot and reflected by the dot size. A change of ±2 points between first and second GCS score was considered clinically irrelevant (unfilled circles). Patients with changes of their GCS score of 3 or more points are considered clinically relevant (filled circles). GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

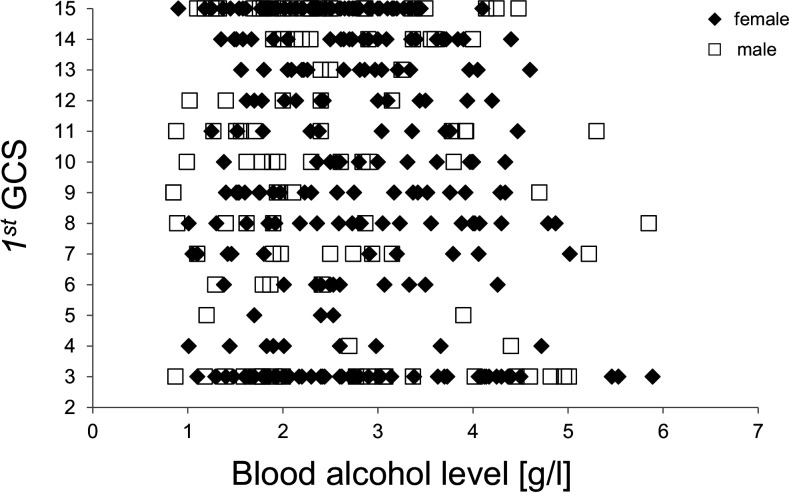

To rule out any bias due to mixed GCS records (ie, pooled first and second GCS scores), all following analyses regarding GCS scores were performed with the first GCS score only. The median first GCS score did not differ between male and female patients (10 vs 10, p=0.864). Blood alcohol levels did neither correlate with the initial GCS score in the general population (r=−0.05, p=0.279), nor for male (r=−0.05, p=0.331) or female (r=−0.04, p=0.673) patients. Nevertheless, very high blood alcohol levels (>5 g/L) were measured only in patients with a first GCS score ≤11 (figure 4). The highest blood alcohol levels of 5.9 and 5.9 g/L were found in 2 patients with a GCS score of 3 and 8, respectively.

Figure 4.

Correlation between first GCS score and blood alcohol level for male (□) and female (♦) patients. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Within the total population of n=411 patients, aspiration was found in n=21 (5%). Aspiration was diagnosed by a positive bronchoscopy in n=5 (24%) of these patients. In the remaining n=16 patients, diagnosis of aspiration was based on the presence of at least one of the following criteria: coarse crackles on auscultation (n=9), new opacities on chest X-ray (n=6), development of fever or laboratory signs of inflammation (n=6). In order to identify risk factors for aspiration in alcohol intoxicated patients, we compared the cohorts with and without aspiration regarding demographic characteristics, vital signs, blood alcohol level, blood glucose level and airway management. In univariate analysis of continuous risk factors for aspiration, patients with aspiration were significantly older (mean age 47 vs 35 years), had a higher blood alcohol level (mean 3.4 vs 2.6 g/L), a lower first GCS score (median 3 vs 11), a lower (SpO2, mean 90 vs 96%), a lower respiration rate (mean 13 /min vs 15 /min) and a higher blood glucose level (139 vs 109 mg/dL) (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of continuous risk factors for aspiration

| Parameter | Patients without aspiration Mean±SD (range) |

Eligible patients | Patients with aspiration Mean±SD (range) |

Eligible patients | P value |

| Age (years) | 34.6±14.5 (15–74) | 390 | 47.4±9.3 (32–65) | 21 | <0.0001 |

| Blood alcohol level (g/L) | 2.6±1.0 (0.9–5.9) | 390 | 3.4±1.3 (1.7–5.5) | 21 | 0.017 |

| Initial GCS score | 11 (median) ±4 (3–15) | 378 | 3 (median) ±2 (3–9) | 20 | <0.0001 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96±6 (47–100) | 365 | 90±8 (73–100) | 21 | 0.006 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 121±22 (70–200) | 371 | 122±20 (96–160) | 21 | 0.772 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 92±20 (35–180) | 377 | 89±20 (50–120) | 21 | 0.580 |

| Respiratory rate (1/min) | 15±5 (0–35) | 302 | 13±3 (8–18) | 19 | 0.014 |

| Blood glucose level (mg/dL) | 109±40 (65–487) | 388 | 139±60 (72–335) | 21 | 0.028 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

Furthermore, univariate results of binary risk factors revealed a significantly higher risk for aspiration for male patients, patients with documented airway measures as listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of binary risk factors for aspiration

| Parameter | Manifestation | Patients without aspiration (%) (n) | Patients with aspiration (%) (n) | Evaluable patients (n) | P value |

| Gender | Male | 93.5 (275) | 6.5 (19) | 294 | 0.048 |

| Female | 98.3 (115) | 1.7 (2) | 117 | ||

| Vomiting | No | 96.4 (317) | 3.7 (12) | 329 | 0.017 |

| Yes | 89.9 (71) | 10.1 (8) | 79 | ||

| Oxygen supply | No | 99.2 (262) | 0.8 (3) | 265 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 86.9 (126) | 13.1 (19) | 145 | ||

| Guedel tube application | No | 95.5 (382) | 4.5 (18) | 400 | 0.0003 |

| Yes | 70.0 (7) | 30.0 (3) | 10 | ||

| Mask ventilation | No | 95.8 (383) | 4.2 (17) | 400 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 60.0 (6) | 40.0 (4) | 10 | ||

| Protective airway reflexes (at GCS score ≤8) | No | 54.6 (12) | 45.4 (10) | 22 | 0.0001 |

| Yes | 94.2 (49) | 5.8 (3) | 52 | ||

| Secretion suction | No | 96.5 (382) | 3.5 (14) | 396 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 46.1 (6) | 53.9 (7) | 13 | ||

| Intubation | No | 98.4 (377) | 1.6 (7) | 384 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 44.4 (12) | 55.6 (15) | 27 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Intubated patients showed a significantly higher aspiration rate than patient’s without intubation (56% vs 2%). Since many emergency physicians base their decision for intubation in patients with a GCS score ≤8 on the presence or absence of the swallowing and gag reflex, the presence of these protective reflexes was correlated with the risk of aspiration. A total of n=152 patients had a first GCS score ≤8. Data regarding protective reflexes were available in n=74 (49%) of these patients. Protective reflexes in patients with GCS score ≤8 were present in n=52 (70%), but absent in n=22 (30%). The absence of protective reflexes was significantly associated with a higher risk of aspiration: 45% aspiration rate in patients without vs 6% in patients with protective reflexes (p=0.0001, table 3).

On multivariate analysis of the risk factors gender, age, blood alcohol level, first GCS score, and SpO2, only age (OR 1.06) and GCS score (OR 0.71) significantly correlated with the risk of aspiration (table 4).

Table 4.

OR estimates in multivariate analysis of risk factors for aspiration

| Risk factor | OR | 95% CIs | P value |

| Gender (male vs female) | 3.29 | 0.67 to 16.03 | 0.141 |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.10 | 0.005 |

| Blood alcohol level | 1.26 | 0.80 to 2.00 | 0.320 |

| First GCS score | 0.71 | 0.60 to 0.84 | <0.0001 |

| Oxygen saturation | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.03 | 0.397 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

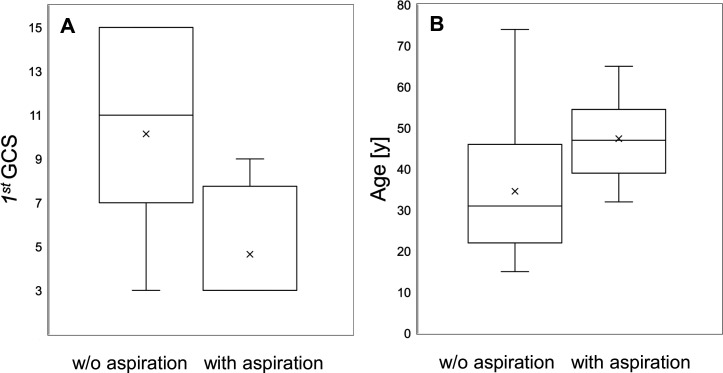

Due to the low number of complete data sets, presence of protective reflexes could not be included in the multivariate analysis. The difference of age and GCS score between aspirated and non-aspirated patients is visualised as box plots in figure 5A, B. However, a GCS score=3 had a low sensitivity (60%) and a moderate specificity (83%) for aspiration, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of only 16% and very high negative predictive value (NPV) of 98%. Since information on the preservation of protective airway reflexes in these patients were rather scarce, the PPV and NPV were calculated for a GCS score=3, irrespective of the gag reflex.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the first GCS score (A) and age (B) for patients without aspiration versus proven aspiration, presented as box plots. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Discussion

Acute alcohol intoxication constitutes a frequent medical problem with a considerable socioeconomic and healthcare system burden. The demographic analysis of our cohort shows a predominance of young male patients, which is comparable to other demographic studies.18 19 However, our ICU cohort showed a younger age distribution than another retrospectively analysed cohort of patients admitted to an emergency department.1 With a mean alcohol level of 2.7 g/L, our cohort showed higher blood alcohol levels than many other studies,20–23 which might be due to the selection of ICU patients. In contrast to Vereslt et al,1 a higher age was associated with a higher blood alcohol level in our cohort.

Since the short period of prehospital care of alcoholised patients impedes a relevant alcohol degradation, one would expect—if at all—a deterioration of the GCS between the first patient contact and the admission to the hospital due to an ongoing alcohol resorption in the alimentary tract. However, 19% of our patients showed an improvement of more than 2 GCS score points during their prehospital care, but only 3% of patients showed a relevant deterioration. Overall, we found a strong correlation between the first and second GCS score. The prehospital blood alcohol level is not routinely available to the emergency team. Therefore, we can neither provide data on its kinetics, nor does the clinical decision rely on these data. The GCS score of head injured trauma patients with additional alcohol intoxication also improved between prehospital care and the emergency department.24 This implies that the measurement time point of the GCS score during the prehospital care should be exactly defined and pooling of GCS data from different phases of care should be avoided. Slight changes in GCS score might not necessarily reflect a clinically relevant change of consciousness level of alcoholised patients. We, therefore, considered only an arbitrarily defined ΔGCS of ≥3 as clinically relevant.

Most data on the influence of alcohol on the GCS score were derived from trauma patients. Some studies showed a correlation between blood alcohol level and GCS score,25 while others did not.26–28 In our study on non-traumatic alcoholised patients, the blood alcohol level did not correlate with the GCS score even at a considerably high mean blood alcohol level of 2.7 g/L. In adolescent patients (13–17 years of age) with rather mild alcohol intoxication (mean 1.6 g/L), Mick et al20 found a significant correlation between the blood alcohol level and the GCS score. One might speculate that adolescents and younger adults have not yet undergone habituation to regular alcohol consumption. However, even in the youngest subgroup (15–25 years) of our study, there was no significant correlation between blood alcohol level and GCS score (n=136 patients, mean blood alcohol level 2.1 g/L, median GCS score 10, p=0.061).

One of the most challenging clinical problems in unconscious alcohol-intoxicated patients is the decision for or against airway protection by intubation. Many studies were performed in heterogeneous cohorts of mixed intoxication,7 9 29–31 in patients with trauma8 32 or without any data on the risk of aspiration.8 29 While some authors and recommendations refer to a GCS score ≤8 as an indication for intubation in alcohol intoxicated patients, the association of a low GCS score with a higher risk of aspiration has not been sufficiently substantiated in these patients. In their prospective observational study, Duncan et al7 did not find a higher rate of aspiration in patients with a GCS score ≤8. However, only n=22 of 73 patients had alcohol monointoxication and only n=12 patients of their entire cohort demonstrated a GCS score ≤8. Comparing n=12 intubated (mean GCS score 5.9) with n=14 not-intubated (mean GCS score 5.5) patients with mixed intoxication, Donald et al9 did not detect a difference in laboratory or physiological parameters. However, the aspiration rate was not analysed. None of the intubated patients had an alcohol intoxication. In patients with a mixed intoxication, the risk of aspiration pneumonia did not significantly differ between patients with a GCS score ≤8 vs a GCS score >8.13 In another prospective study on n=224 drug-intoxicated patients, there was no correlation between the GCS score and the risk of aspiration.31 A GCS score ≤8 was not considered as essential for an increased risk of aspiration. However, the aspiration rate in that drug-intoxicated cohort was very high (29%) compared with our study (5%). This indicates that mixed intoxication and alcohol monointoxication might not be comparable regarding the risk of aspiration.

In our study on non-traumatic alcohol-monointoxicated patients, we found a strong correlation between the GCS score and the risk of aspiration, even in a multivariate regression model. However, n=133 of the 152 patients (88%) with GCS score ≤8 did not aspirate. Thus, even for a GCS score=3 the PPV is too low (16%) to guide the decision for intubation. However, Sauter et al8 described that a GCS score ≤8 was the main reason for emergency teams to decide for intubation in intoxicated patients. In our cohort, emergency physicians—according to their emergency protocols—made a more differentiated decision for intubation based on GCS score, presence of the gag reflex, vomiting and the suspicion of aspiration.

An alternative parameter to estimate the risk for aspiration is the presence of the gag or cough reflex. However, in a very small cohort of patients with pharmacologically induced coma the cough reflex did not correlate with the GCS score, as n=4 of 12 patients (33%) with a GCS score=3 had an unimpaired cough reflex. On the other hand, three of five patients (60%) with a GCS score=8 had an impaired cough reflex.29 These data are supported by the detection of a depressed gag reflex in drug-intoxicated patients even at a GCS score ≥8.30 Of note, none of these studies has been performed in alcohol monointoxicated patients. In our study we could obtain information on the gag or cough reflex in n=74 patients. The absence of protective airway reflexes did significantly correlate with an increased risk of aspiration in a univariate analysis (table 3). Furthermore, all airway measures significantly correlated with the rate of aspiration (table 3). For instance, the necessity of secretion suction or intubation (on the discretion of the emergency physician) were each associated with an aspiration rate of >50%. Our data are in line with a smaller retrospective study on n=155 patients with mixed intoxication in which patients with reduced GCS scores or an impaired gag reflex had a higher risk for an aspiration pneumonitis.12 An absent or reduced gag reflex was found in 96% of their patients with aspiration. However, the high aspiration rate of 15% in their cohort of mixed intoxication might be related to the application of gastric lavage and charcoal administration which is not applied in alcohol monointoxication. Our study impressively shows that the execution of some airway measures (eg, oxygen supply) or encountered vomiting indicated only a low risk of aspiration, while other measures (eg, mask ventilation, secretion suction, intubation) and the lack of protective airway reflexes indicate a high aspiration incidence in these patients. This would imply a thorough diagnostic (eg, X-ray, bronchoscopy) or therapeutic (eg, antibiotic treatment) workup in these high-risk patients on ICU admission. However, a GCS score ≤8 alone should not warp the emergency physician into endotracheal intubation.

Although herewith we present—to the best of our knowledge—the most comprehensive analysis of the aspiration risk in alcohol monointoxicated patients, our study has some limitations. Due the retrospective nature of our study, we cannot provide direct clinical recommendations. Since protective airway reflexes were evaluated by the emergency team only in a subset of patients, there might be a bias towards reporting rather impaired than normal reflexes. However, since both preserved and impaired protective reflexes were listed as the reason against and in favour of intubation, respectively, we could not detect unilateral under-reporting or over-reporting. Since we focused on severely alcohol-intoxicated patients admitted to the ICU of our hospital, our finding might not be extrapolated to the general population with alcohol monointoxication in an emergency department.

Conclusion

In our retrospective study, we found that the blood alcohol level did correlate with the patient’s age but not with the GCS score. However, both age and GCS score did correlate with the risk of aspiration. A GCS score=3 has a very low PPV for aspiration. We identified risk factors for aspiration in alcohol monointoxicated patients: Guedel tube application, mask ventilation, loss of protective airway reflexes, secretion suction, intubation. These patients might benefit from an aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic workup. Since only 6% of patients with preserved gag reflexes had aspirated, in this patient subgroup the risk of intubation might prevail its benefits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank Dr Thomas Koschny for assistance and support of graphical data representation.

Footnotes

Contributors: MC, AH, EP and RK planned the study and performed the data acquisition. Statistical analysis was performed by TB. Manuscript writing and editing was performed by MC, AH, EP, TB and RK. The manuscript was submitted by MC.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Deidentified participant data are available from the corresponding autor on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local ethics board of Heidelberg University (S-329/2013).

References

- 1.Verelst S, Moonen P-J, Desruelles D, et al. Emergency department visits due to alcohol intoxication: characteristics of patients and impact on the emergency room. Alcohol Alcohol 2012;47:433–8. 10.1093/alcalc/ags035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pirmohamed M, Brown C, Owens L, et al. The burden of alcohol misuse on an inner-city General Hospital. QJM 2000;93:291–5. 10.1093/qjmed/93.5.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myran DT, Hsu AT, Smith G, et al. Rates of emergency department visits attributable to alcohol use in Ontario from 2003 to 2016: a retrospective population-level study. CMAJ 2019;191:E804–10. 10.1503/cmaj.181575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krumpe PE, Cummiskey JM, Lillington GA. Alcohol and the respiratory tract. Med Clin North Am 1984;68:201–19. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)31250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vonghia L, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:561–7. 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentleman D, Dearden M, Midgley S, et al. Guidelines for resuscitation and transfer of patients with serious head injury. BMJ 1993;307:547–52. 10.1136/bmj.307.6903.547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan R, Thakore S. Decreased Glasgow coma scale score does not mandate endotracheal intubation in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2009;37:451–5. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauter TC, Rönz K, Hirschi T, et al. Intubation in acute alcohol intoxications at the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2020;28:11. 10.1186/s13049-020-0707-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald C, Duncan R, Thakore S. Predictors of the need for rapid sequence intubation in the poisoned patient with reduced Glasgow coma score. Emerg Med J 2009;26:510–2. 10.1136/emj.2008.064998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernhard M, Bein B, Böttiger BW, et al. Handlungsempfehlung Zur prähospitalen Notfallnarkose beim Erwachsenen. Notfall + Rettungsmedizin 2015;18:395–412. 10.1007/s10049-015-0041-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luckscheiter A, Lohs T, Fischer M, et al. [Preclinical emergency anesthesia : A current state analysis from 2015-2017]. Anaesthesist 2019;68:270–81. 10.1007/s00101-019-0562-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eizadi-Mood N, Saghaei M, Alfred S, et al. Comparative evaluation of Glasgow coma score and Gag reflex in predicting aspiration pneumonitis in acute poisoning. J Crit Care 2009;24:470.e9–470.e15. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montassier E, Le Conte P. Aspiration pneumonia and severe self-poisoning: about the necessity of early airway management. J Emerg Med 2012;43:122–3. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orso D, Vetrugno L, Federici N, et al. Endotracheal intubation to reduce aspiration events in acutely comatose patients: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2020;28:116. 10.1186/s13049-020-00814-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driver BE, Klein LR, Schick AL, et al. The occurrence of aspiration pneumonia after emergency endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:193–6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zehtabchi S, Sinert R, Baron BJ, et al. Does ethanol explain the acidosis commonly seen in ethanol-intoxicated patients? Clin Toxicol 2005;43:161–6. 10.1081/CLT-53083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenenbein M. Do you really need that emergency drug screen? Clin Toxicol 2009;47:286–91. 10.1080/15563650902907798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulse GK, Robertson SI, Tait RJ. Adolescent emergency department presentations with alcohol- or other drug-related problems in Perth, Western Australia. Addiction 2001;96:1059–67. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967105915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano E, Pollini RA. Patterns of drug use in fatal crashes. Addiction 2013;108:1428–38. 10.1111/add.12180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mick I, Gross C, Lachnit A, et al. Alcohol-Induced impairment in adolescents admitted to inpatient treatment after heavy episodic drinking: effects of age and gender. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2015;76:493–7. 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tõnisson M, Tillmann V, Kuudeberg A, et al. Plasma glucose, lactate, sodium, and potassium levels in children hospitalized with acute alcohol intoxication. Alcohol 2010;44:565–71. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shavit I, Konopnicki M, Winkler K, et al. Serum glucose and electrolyte levels in alcohol-intoxicated adolescents on admission to the emergency department: an unmatched case-control study. Eur J Pediatr 2012;171:1397–400. 10.1007/s00431-012-1766-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lien D, Mader TJ. Survival from profound alcohol-related lactic acidosis. J Emerg Med 1999;17:841–6. 10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00093-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahin H, Gopinath SP, Robertson CS. Influence of alcohol on early Glasgow coma scale in head-injured patients. J Trauma 2010;69:1176–81. discussion 81. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181edbd47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rundhaug NP, Moen KG, Skandsen T, et al. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: effect of blood alcohol concentration on Glasgow coma scale score and relation to computed tomography findings. J Neurosurg 2015;122:211–8. 10.3171/2014.9.JNS14322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange RT, Iverson GL, Brubacher JR, et al. Effect of blood alcohol level on Glasgow coma scale scores following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2010;24:919–27. 10.3109/02699052.2010.489794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sperry JL, Gentilello LM, Minei JP, et al. Waiting for the patient to "sober up": Effect of alcohol intoxication on glasgow coma scale score of brain injured patients. J Trauma 2006;61:1305–11. 10.1097/01.ta.0000240113.13552.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuke L, Diaz-Arrastia R, Gentilello LM, et al. Effect of alcohol on Glasgow coma scale in head-injured patients. Ann Surg 2007;245:651–5. 10.1097/01.sla.0000250413.41265.d3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moulton C, Pennycook AG. Relation between Glasgow coma score and cough reflex. Lancet 1994;343:1261–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92155-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moulton C, Pennycook A, Makower R. Relation between Glasgow coma scale and the gag reflex. BMJ 1991;303:1240–1. 10.1136/bmj.303.6812.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adnet F, Baud F. Relation between Glasgow coma scale and aspiration pneumonia. Lancet 1996;348:123–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64630-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vadeboncoeur TF, Davis DP, Ochs M, et al. The ability of paramedics to predict aspiration in patients undergoing prehospital rapid sequence intubation. J Emerg Med 2006;30:131–6. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified participant data are available from the corresponding autor on reasonable request.