Significance

How much are we in control of our decisions? The current study explores how goal-relevant (top-down) and perceptual features (bottom-up) govern the distribution of attention in risky choice. Findings from participants’ choices, eye movements, and computational modeling analysis show that while salient perceptual features can influence the acquisition of information, their influence on choice is limited to situations in which those features are tied to potential outcomes of the decision. When such features are not tied to outcomes, their influence is suppressed by top-down control. These results suggest, contrary to popular accounts, that perceptual salience can induce bottom-up effects of overt selection, but the perceived value of information is the crucial arbiter of intentional control over choice.

Keywords: top-down, bottom-up, risky choice, extreme outcomes, selective attention

Abstract

We examine how bottom-up (or stimulus-driven) and top-down (or goal-driven) processes govern the distribution of attention in risky choice. In three experiments, participants chose between a certain payoff and the chance of receiving a payoff drawn randomly from an array of eight numbers. We tested the hypothesis that initial attention is driven by perceptual properties of the stimulus (e.g., font size of the numbers), but subsequent choice is goal-driven (e.g., win the best outcome). Two experiments in which task framing (goal driven) and font size (stimulus driven) were manipulated demonstrated that payoffs with the highest values and the largest font sizes had the greatest impact on choice. The third experiment added a number in large font to the array, which could not be an outcome of the gamble (i.e., a distractor). Eye movement and choice data indicated that although the distractor attracted attention, it had no influence on option selection. Together with computational modeling analyses, the results suggest that perceptual salience can induce bottom-up effects of overt selection but that the perceived value of information is the crucial arbiter of intentional control over risky choice.

Several recent studies demonstrate that attended information is more likely than unattended information to influence choice (e.g., refs. 1–4). A question arising from this work is how different properties of a stimulus drive attentional allocation and subsequent choice. For example, when choosing among a variety of snacks displayed on a supermarket shelf, which property is more likely to attract one’s attention and influence choice: the brand name that is associated with prior knowledge of the product or the size of the logo design that influences its distinctiveness on the shelf?

A long-running tradition distinguishes between two types of processes that govern attention. One is top-down attention—driven by higher-level cognition such as the decision maker’s goals, intentions, and previous knowledge (i.e., the brand name in the supermarket example) (5, 6). The other is bottom-up attention—driven by lower-level perceptual properties of the stimulus, such as color or size, which determine the stimulus’ physical salience and hence distinctiveness in the environment (i.e., the logo design in the example) (refs. 7 and 8; for a review, see ref. 9). Here, we investigate how these two types of processes govern the distribution of attention when sampling information about various properties within gamble options. We draw a distinction between encoding the presence of an item and sampling that item (i.e., evaluating it as a potential outcome in a way that influences choice). Our main goal is to present a detailed description of how attention is employed to sample information about the goodness of a choice option with multiple properties, in which some properties are presumably more relevant for choice than others. Using converging evidence from participants’ choices, eye movements, and computational modeling analysis, we illustrate the way in which top-down and bottom-up attention interact to determine risky choice.

It is commonly assumed that our goals and intentions govern choice. However, recent evidence suggests that there can be bottom-up effects on decision making, such as the impact of perceptual properties, like the color of options, that are less relevant for the outcome of choice (e.g., refs. 10 to 14). For example, Towal, Mormann, and Koch (4) tested preference for snack foods and found that both the products’ value and visual saliency influenced choice, with eye movement data suggesting that the salience of the products’ visual features biased choice by modulating attention. Visually salient aspects of the stimuli in these studies were often tied to a potential outcome of the decision (e.g., the salient stimuli were snacks that could be chosen and won). As such, it is difficult to determine whether these bottom-up effects on option selection arise due to less relevant perceptual properties (wherein participants pick the visually salient option because it is more salient independent of its status or value as a possible choice) or as part of a top-down strategy to prioritize visually salient stimuli in sampling and processing because they are “easier” to attend to. We investigate this issue by testing the influence of a visually salient stimulus that is either tied to a potential outcome (Experiments 1 and 2) or is irrelevant—that is, framed as a distractor, which participants are instructed to ignore (Experiment 3). If the perceptual properties of a visually salient stimulus still influence choice even when participants know that the stimulus can never be a valid outcome, this would suggest that visual salience exerts a “pure” bottom-up effect on choice that is independent of top-down strategy.

To explore how top-down and bottom-up attention interact to influence choice, we developed an experimental paradigm in which participants chose between a known certain payoff (CP) and a risky gamble—presented briefly as an array of numbers in different font sizes (Fig. 1A). If a participant chose to gamble, a payoff was randomly drawn from the values in the array; otherwise, they received the CP. Here, participants must quickly evaluate the items in the array to determine the likely outcome of gambling. Previous research suggests that, under such conditions, participants are often driven by a goal (i.e., top down), being motivated to seek the largest payoffs and avoid the smallest, and thus selectively focus limited attentional resources on the most extreme items in the array (e.g., the highest numbers) (ref. 15; see also refs. 16 to 20). We further propose that top-down attention to goal-consistent features may be preempted by an initial (bottom-up) attraction to elements of the display that are visually salient, such as numbers appearing in a larger font size (11); here, we assume that items in larger font size had higher physical salience than others because their physical features were both distinctive (different in size from other items in the array; ref. 7) and more “intense” than those of other items [e.g., more white pixels, subtended greater visual angle (21, 22)] (see Discussion for further consideration of this assumption). We compare situations in which these two potential influences on choice converge—such as when the physically largest number in the display is also numerically largest—with situations in which they compete—such as when physical size and numerical value are negatively correlated (Experiment 1 and 2). Crucially, we also manipulate whether visually salient elements support an explicit goal, such as whether a number in large font is a potential payoff from the array or is a distractor with no value for choice (Experiment 3).

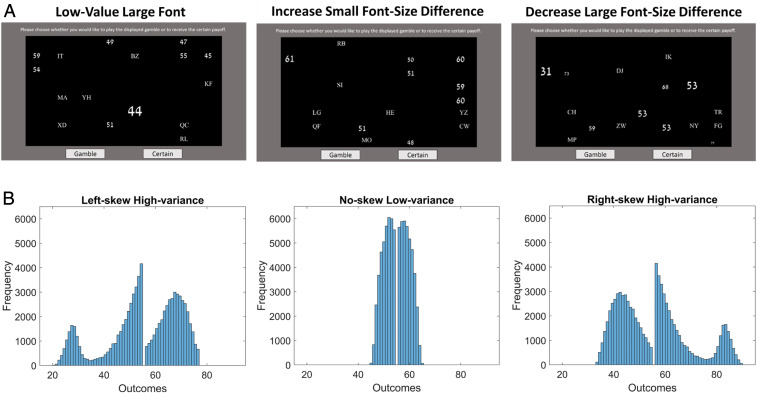

Fig. 1.

(A) Example array displays in which the participants are required to decide between winning (losing) a certain amount or taking a gamble of winning (losing) one of the amounts in the array chosen at random. In Experiment 1, we increased the font size of the lowest value in the array (Low-Value Large Font), the highest value (High-Value Large Font), or neither (All Values Same Font). (Left) The panel shows an example for the Low-Value Large Font condition. In Experiment 2, the payoffs’ font sizes either increased (Font-Size Increase) or decreased (Font-Size Decrease) with value rank, and differences among the font sizes were either small (Small Font-Size Difference) or large (Large Font-Size Difference). (Middle) The panel shows an example array in which font size increases as a number’s value rank in the display increases (i.e., numerically larger numbers are also physically larger), but the relative differences in font size across numbers are small. (Right) The panel shows an example array in which font size increases as a number’s value rank in the array decreases (numerically larger numbers are physically smaller) and the relative differences in font size are larger. The design of Experiment 3 was similar to Experiment 1, except participants were informed that the number in a larger font is a distractor (i.e., could not be selected as a payoff from the array). In all experiments, participants were informed that the letter bigrams were noninformative distractors included to make the visual search for numbers more difficult. (B) Plots of the frequency of outcome values displayed in the array, for trials with a corresponding CP of 55, in the three distribution conditions (Left-skew High-variance, No-skew Low-variance, Right-skew High-variance). These plots show data from 30,000 displays (10,000 in each condition) generated using the same procedure used in Experiments 1 through 3. The shape of the distributions is irregular because we constrained the number of items above and below the CP to be equal, and there is a gap at the CP because none of the array outcomes could be equal to the CP.

To operationalize differences in participants’ goals, we manipulated the framing of the task between groups such that the numbers in the arrays were described as potential gains or losses. We expected that participants in both groups would be motivated to win the best outcome. However, the best possible outcomes in gains and in losses are positioned at opposite ends of the distribution of numbers in the stimulus array—i.e., higher numbers are better in gains, and lower numbers are better in losses. Therefore, focusing on the best possible outcomes should encourage the participants to prioritize opposite properties of the array between gains and losses conditions (termed gamble type in what follows). We also manipulated the skew and variance properties of the outcome distributions in the arrays to elucidate how choice was influenced by the (goal-relevant) value information contained within the display (Fig. 1B). Following prior research and theorizing (see ref. 15), we anticipated that participants’ value estimates would be most influenced by the extreme (highest-value) outcomes in the array such that changing the shape of the outcome distribution—and hence the pattern of these extreme outcomes—should causally impact their choices (see Materials and Methods for examples).

We use our results regarding choice and gaze data to develop an account that incorporates influences of both value and attention. For the latter, we hypothesized that the first item attended is the most visually salient item in the display, irrespective of whether the item is consistent with winning the best outcome or even tied to a potential outcome. Thus, we proposed that bottom-up attention can be indexed by the proportion of instances in which a given item is the first to be fixated. We then examined the proportion of time spent looking at each item and take this as an indication of a top-down process. Specifically, looking time is taken to reflect whether an attended item represents a potential payoff that is consistent with the goal of winning the best outcome or a “distractor” that should be ignored as it has no value for choice. We assumed that if an item is goal relevant, then attention to the item persists and looking time increases; if it is not, then we expected to see rapid disengagement and shifting of attention toward the next salient item (9). Following the distinction between encoding the presence of an item and sampling that item, we assumed that while the former is modulated by bottom-up attention, the latter is governed by top-down control. We argue that the direction of attention is initially governed by a bottom-up process reflecting the attraction of visually salient items (i.e., larger font size) so that such items are more likely to undergo basic perceptual encoding. Following this initial deployment of attention to an item, a subsequent top-down mechanism determines whether processing remains focused on that item as it is sampled or whether attention disengages and moves toward the next salient item. Across three experiments, we found evidence that participants are able to selectively engage (and disengage) processes that reflect the interplay of top-down and bottom-up attention in sampling features within alternatives. Our computational model provided a formal explanation of how different stimulus properties that tap into top-down and bottom-up processes can influence sampling and choice.

Results

Experiment 1.

On each trial, participants briefly saw an array containing a set of numbers and then chose whether to 1) receive (in the gains condition) or lose (losses condition) a CP, which varied between blocks of trials, or 2) take a gamble and receive (lose) one of the amounts shown in the array, selected randomly. Critically, arrays differed in terms of both the visual salience (the font size in which items appeared) and goal-relevant properties (the distributions of potential outcome values). With regard to font size, in some trials, the highest-value item in the array appeared in a larger font than all other items (high-value large-font condition); in other trials, the lowest value in the array appeared in a larger font (low-value large-font), and in other trials, all items had the same font size (all-values same-font). With regard to outcome values, we manipulated the distribution of numeric values in the array so that potential outcome values were either left skewed with high variance (LS-HV), right skewed with high variance (RS-HV), or nonskewed with low variance (NS-LV). This resulted in sets of arrays that had similar overall expected value, but in which the mean of the subset of highest-valued (extreme) outcomes in the array presented on each trial differed systematically. For example, whereas the mean across all eight items in the display was similar across conditions, the mean across the six highest-valued items in the array varied between conditions, being highest for LS-HV arrays, followed by RS-HV arrays, and lowest for NS-LV. Consequently, if participants’ choices were based primarily on the largest outcomes in the display (see ref. 15), we would expect the likelihood of choosing the array to be in the order LS-HV > RS-HV > NS-LV for gains. For losses, we anticipated that participants’ choices would be based on a subset of the lowest-value outcomes (i.e., the best possible outcomes), predicting the ordering RS-HV > LS-HV > NS-LV (see Materials and Methods for details).

Overall, participants faced an equal number of trials in which the expected value of the array was above CP, below CP, or approximately equal to CP. To assess participants’ overall engagement with the task, we first examined whether selection of the superior option was above chance. Across participants, choice for the superior option was greater than chance if the array’s mean was above (M = 0.55, SD = 0.13; t(78) = 3.77, p < 0.001, d = 0.426) or below (M = 0.63, SD = 0.13; t(78) = 8.96, p < 0.001, d = 1.008) the CP but was at chance if the expected values of the two options were approximately equal (M = 0.50, SD = 0.05; t(78) = −0.36, p = 0.718, d = −0.041). While the effect of array values above or below CP was highly significant, it was not huge numerically; this was unsurprising, since even in these conditions, the difference between CP and the mean of the array was relatively small (µ∼CP ± 3).

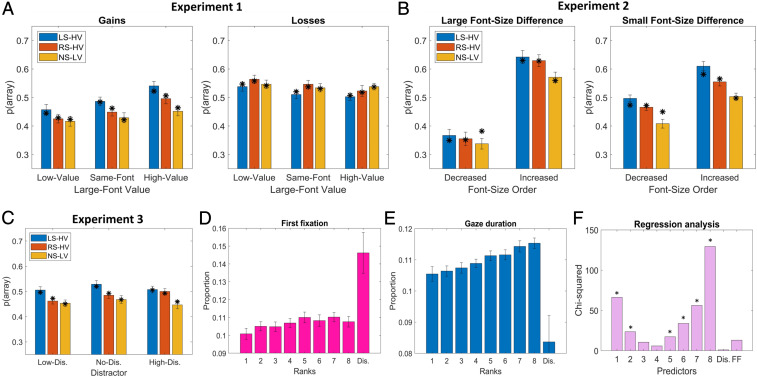

Next, we analyzed the influence of our experimental conditions on the proportion of the gamble choices (termed p[array]) by using a probit mixed-effects model with p(array) as the dependent variable; gamble type, large-font value, and outcome distribution as fixed effects; and participant as a random intercept effect.* The average p(array) values among the conditions are presented in Fig. 2A. We found a main effect for gamble type [χ2(1) = 8.86, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.102), with participants more likely to choose the gamble for losses (M = 0.54, SD = 0.11) than for gains (M = 0.46, SD = 0.11), and a small main effect for large-font value [MHigh = 0.51; SD = 0.13; MSame = 0.49; SD = 0.13; MLow = 0.49; SD = 0.14; χ2(2) = 6.49, p = 0.039, η2 = 0.017]. Importantly, an interaction between gamble type and large-font value [χ2(2) = 38.04, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.077] suggested that in gains, people chose to gamble more often when the font size of the highest payoff was large (M = 0.50, SD = 0.13) than when all values were in the same font size (M = 0.46, SD = 0.13) and were more likely to avoid gambling when the font size of the lowest payoff was large [M = 0.43, SD = 0.13; χ2(2) = 36.94, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.138]. In losses, we found the opposite trends [MHigh = 0.52; SD = 0.12; MSame = 0.53; SD = 0.12; MLow = 0.55; SD = 0.12; χ2(2)=7.61, p = 0.022, η2 = 0.034], although the effect size was small. Despite being informed that font size had no impact on the probability of an item being selected, participants preferred to gamble when the best possible outcome was in larger font size, consistent with a bottom-up influence on choice. Further, an interaction between outcome distribution and gamble type was found [χ2(2) =35.31, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.115), showing that in gains, participants gambled most often for LS-HV (M = 0.50, SD = 0.14), followed by RS-HV (M = 0.46, SD = 0.12) and NS-LV [M = 0.43, SD = 0.13; χ2 (2) = 34.83, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.179], while a significantly different ordering was found in losses [MLS-HV = 0.52, SD = 0.14; MRS-HV = 0.54, SD = 0.14; MNS-LV = 0.54, SD = 0.14; χ2(2) = 7.60, p = 0.022, η2 = 0.060]. This replicates findings from Vanunu, Hotaling, and Newell (15) and suggests that people often prioritize the highest-ranked items in the display in gains and the lowest-ranked items in losses because they are the best possible outcomes, while paying less attention to items from the opposite extreme.

Fig. 2.

(A–C) The average proportion of choosing the array (rather than the certain amount) between conditions and experiments. LS-HV, RS-HV, and NS-LV describe Left-skew High-variance, Right-skew High-variance, and No-skew Low-variance displays, respectively. The asterisks indicate the mean predictions collapsed across participants, generated by their best-fitting model version (see The SSIM for details). (D) The proportion of times each of the value ranks or the distractor were fixated first across trials and participants. (E) The proportion of time spent looking at each value rank during an array display, collapsed across trials and participants (Right). (F) χ2 values from the regression analysis, where first fixation and gaze duration for value ranks and the distractor were set as predictors for risky choice. Larger χ2 values indicate larger effects for the respective predictor, and black asterisks indicate values that are significantly greater than zero (at p < 0.001). Across panels, “Dis.” indicates distractor, “FF” indicates first fixation, and error bars correspond to within-subjects SE.

Together, the results of Experiment 1 offer some insight into the complementary and competing roles that top-down and bottom-up attention might play in governing risky choice. In line with our predictions, we found that risky choice increased (decreased) if the best (worst) outcome in the array was visually salient, consistent with the idea that bottom-up attention to items in larger font size increased the item’s influence on choice (though we consider an alternative interpretation in Discussion). On this account, in an environment in which sampling is limited by the duration of the display, the visually salient item is more likely to attract the participant’s attention and, therefore, to be considered in choice—and other (less visually salient) items are correspondingly less likely to be encoded and sampled. When the salient (large font) item has a higher value than other items in the array, this mechanism will tend to increase choice of the array (versus the certain option), and when the salient item has a lower value than other items in the array, it will tend to decrease choice of the array. In addition, it seems that top-down attention led participants to prioritize the best outcomes in sampling—high gains and low losses—resulting in more risk seeking for LS-HV than RS-HV and NS-LV in gains but a different pattern in losses. These results are consistent with our predictions for the ordering of the outcomes distribution conditions in gains (LS-HV > RS-HV > NS-LV) and are partly consistent for losses. Here, although the overall differences in choice rates between distributions were smaller, we observed the predicted pattern of riskier choice in the RS-HV condition than LS-HV. However, contrary to our predictions, the array was chosen more often for NS-LV than for RS-HV. Nonetheless, gamble type did significantly modulate choice, reinforcing our assumption of a top-down influence of participants’ goals (see SI Appendix for additional model-based analyses relating differences in choice patterns between gains and losses to participants’ sampling policies).

Experiment 2.

Experiment 2 focused solely on the gain domain but employed a potentially more diagnostic manipulation of font size. Rather than simply highlighting the highest or lowest value in the display, in Experiment 2, the font size was varied on a scale that increased (i.e., font-size increase) or decreased (i.e., font-size decrease) with value-rank order, with the difference between the font sizes being either perceptually large (i.e., large font-size difference) or small (i.e., small font-size difference; see Fig. 1 A, Middle and Right). We hypothesized that the bottom-up effect of visual salience would be most pronounced in the large font-size difference condition, in which items differed most prominently in their physical size such that resulting differences in attention to items would have a substantial impact on choice. Consequently, we predicted that participants would be more risk seeking for displays in which font size and values were positively correlated (font size increases as value increases) than when they were negatively correlated (font size decreases as value increases). By contrast, in the small font-size difference condition, top-down attention should have a greater influence on choice patterns (i.e., a smaller effect of font-size order and correspondingly larger effect of outcome distribution), because here, the items in the display had more similar visual salience.

The same analysis from Experiment 1 was applied in Experiment 2 but including font-size order and font-size difference as fixed factors in the probit mixed-effects model. Across participants, choice for the superior option was greater than chance for the above [M = 0.56, SD = 0.13; t(42) = 3.02, p = 0.004, d = 0.460] and below [M = 0.57, SD = 0.12; t(42) = 3.77, p < 0.001, d = 0.575] conditions but at chance for the approximately equal condition [M = 0.51, SD = 0.04; t(42) = 0.79, p = 0.433, d = 0.121], indicating that participants understood the requirements of the task. The average p(array) values among conditions are presented in Fig. 2B. Firstly, Experiment 2 replicated the effect of font size on choice, with participants gambling more often in font-size increase than font-size decrease conditions [MInc. = 0.60, SD = 0.15; MDec. = 0.40, SD = 0.12; χ2(1) = 493.83, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.194]. Secondly, the Outcome Distribution effect was replicated [χ2(2) = 61.29, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.262), showing that p(array) was the highest for LS-HV (M = 0.53, SD = 0.13), followed by RS-HV (M = 0.50, SD = 0.11), and was lowest for NS-LV (M = 0.45, SD = 0.12), again consistent with the idea that people focus on the highest-ranked items in sampling. Moreover, a main effect of font-size difference was found [MLarge-d = 0.46, SD = 0.11; MSmall-d= 0.51, SD = 0.11; χ2(1) =9.27, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.606], but more importantly, a significant interaction between font-size order and font-size difference [χ2(2) = 119.80, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.615] suggested that the effect of font size on choice was larger under large font-size difference [MInc. = 0.63, SD = 0.17; MDec. = 0.34, SD = 0.14; χ2(1) = 543.53, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.639] than under small font-size difference [MInc. = 0.56, SD = 0.14; MDec. = 0.46, SD = 0.11; χ2(1) = 68.42, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.436]. This finding suggests that bottom-up effects of visual salience had a greater impact on choice when differences in font sizes were prominent than when they were less pronounced.

Experiment 3.

Experiments 1 and 2 found evidence for an impact of visual salience of outcome items on choice. A notable feature of those experiments is that the manipulation of visual salience was independent of the utility (value) of each option; that is, all numbers in the array were equally likely to be selected as the outcome of the gamble regardless of their font size. The finding that font size nevertheless influenced choice under these conditions could suggest a relatively automatic bottom-up effect of visual salience on choice, with more salient items being more likely to be sampled regardless of their relevance to a choice. An alternative possibility, however, is that the observed effect of visual salience was mediated by a goal-directed strategy, wherein participants were more likely to sample larger-font numbers because these numbers were easier to read and thus consistent with the goal of collecting the most information possible under a limited display time. Experiment 3 distinguished between these alternatives using a design that was similar to Experiment 1, but in which participants were informed that the large-font item would never be selected as the outcome of the gamble such that this large-font item was a distractor. If the bottom-up effect of visual salience on sampling is automatic (and hence unavoidable), then we would still expect to see evidence of overweighting of the large-font distractor item under these conditions, even though this distractor provided no information relevant to choice. That is, a high-value distractor should produce a larger proportion of gamble choices than a low-value distractor. By contrast, if the effect of visual salience interacts with a top-down strategy, then we would not expect to observe an effect of font size on choice in Experiment 3, in which the large-font item has no goal-relevant information: participants may be more likely to orient attention to (and hence encode) this item but would not sample the item when evaluating the array, such that gamble frequency should be similar in high-value distractor and low-value distractor trials. Importantly, in Experiment 3, we monitored participants’ eye movements to provide a direct, online measure of visual attention. Comparing patterns in gaze and choice then allowed us to discriminate between effects of our manipulations (the font size or value rank of items) on encoding versus sampling of items.

Choice data.

The same analysis as in Experiments 1 and 2 was applied in Experiment 3 but with distractor and outcome distribution as fixed factors in the probit mixed-effects model. Across participants, choice for the superior option was greater than chance for the above [M = 0.58, SD = 0.14; t(49) = 4.21, p < 0.001, d = 0.595] and below [M = 0.61, SD = 0.16; t(49) = 5.02, p < 0.001, d = 0.709] conditions but at chance for the approximately equal condition [M = 0.49, SD = 0.04; t(49) = −0.95, p = 0.349, d = −0.134], indicating that participants understood the requirements of the task. The average p(array) values between conditions are presented in Fig. 2C. Once again, there was a significant main effect of outcome distribution, consistent with a top-down influence on choice [MLS-HV = 0.51; SD = 0.16; MNS-LV = 0.46; SD = 0.13; MRS-HV = 0.48; SD = 0.15; χ2(2) = 44.76, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.107]. However, we found no evidence for significant differences in p(array) among the distractor conditions [MLow = 0.47; SD = 0.15; MNo = 0.49; SD = 0.14; MHigh = 0.49; SD = 0.12; χ2(2) = 5.51, p = 0.064, η2 = 0.041] nor a contrast effect between the low-value distractor and high-value distractor conditions [χ2(1) = 1.73, p = 0.189, η2 = 0.028], consistent with the idea that top-down control successfully suppressed the influence of the distractor on choice.

Gaze data.

Analysis of gaze data focused on two primary variables: the proportion of time participants spent looking at each item during an array display (gaze duration, a proxy for goal-driven top-down processing) and the proportion of trials in which each item was fixated first (first fixation, a proxy for salience-driven bottom-up processing). In addition, we present two secondary measures to reinforce our hypothesis: the proportion of times each item was fixated more than once (repeated fixations) and the average value rank for each position in the sequential fixation order (see Materials and Methods for details). Across participants, an average of 8.04 fixations (SD = 2.44) were made on each trial, 46.8% of which were on outcomes, 4.6% on the distractor, 24.6% on bigrams, and 24.1% on others (i.e., the grid’s center and frame locations or empty regions). A repeated measures ANOVA for differences among the eight value ranks and the distractor in First fixation (Fig. 2D) revealed a main effect of stimulus type (F[1.69,49] = 7.47, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.132, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected). A simple contrast analysis for differences between the distractor (M = 0.15, SD = 0.08) versus other value ranks (10 < M < 0.12, all SD = 0.02) revealed that the distractor was more likely to be fixated first (all p < 0.05 and η2 > 0.122) even though participants knew that this item would not be a payoff, which is consistent with a bottom-up effect wherein large-font items are more likely to initially attract attention regardless of their goal relevance. In contrast, across value ranks, we found no clear differences in first fixations (F[7,49] = 1.40, p = 0.204, η2 = 0.028); that is, initial attentional orienting did not differ significantly among items that had different values but the same font size (i.e., higher-ranked items were not more likely to attract initial attention than lower-ranked items). This latter finding was mirrored by a null effect for differences in the average value rank of fixated items as a function of sequential fixation order (average value ranks: 4.21 < M1−8 < 4.65, 0.14 < SD < 2.20; F[1.25,49] = 0.29, p = 0.649, η2 = 0.028, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected; SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). That is, there was no evidence that (nondistractor) items with a higher value rank were more likely to be fixated prior to items with a lower value rank, consistent with the idea that initial attentional orienting in this task was unrelated to the (goal-relevant) value of items in the array; instead, attentional orienting seemed to be a function of the visual salience of the items.

By contrast, the pattern observed for gaze duration (Fig. 2E) was quite different. Here, participants spent the smallest proportion of time looking at the distractor (M = 0.08, SD = 0.05) and an increasing proportion of time as a function of value rank, peaking for the highest outcome (M = 0.12, SD = 0.02) (F[1.37,49] = 7.51, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.133, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected). A similar pattern was observed for repeated fixations: the proportion of times in which an item was fixated on more than once was lowest for the distractor (M = 0.04, SD = 0.03) and increased with value rank, peaking for the highest rank (M = 0.07, SD = 0.03; F[3.43,49] = 15.17, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.236, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected; SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Hence, the data for gaze duration and repeated fixations were consistent with the operation of a top-down process that prioritized items as a function of their goal-relevant value rather than their visual salience.

Choice as a function of gaze.

We tested a mixed-effects probit regression model with p(array) as the dependent variable and participant as a random intercept. The fixed factors were the proportion of gaze duration for each value rank, the distractor during a display, and a categorical variable that described which item was fixated first on each trial (no interaction components were tested). The χ2 values for each factor are displayed in Fig. 2F, showing that gaze duration for the extreme ranks—especially the high extremes—predicted choice better than did gaze duration for the midrange ranks, while gaze duration for the distractor and the rank/distractor status of the item that was fixated first had little or no relation to risky choice. We also tested a similar mixed-effects model but with the array’s average as one factor and the average of the items weighted by their proportional gaze duration as a second factor (i.e., the average across all items in the display after multiplying each item with the proportion of time the participants spent looking at it). Findings show that although both factors were highly significant, the χ2 and β values were higher for the weighted average factor than for the array’s average factor [weighted average: χ2(1) = 296.85, p < 0.001, β = 0.18; array’s average: χ2(1) = 236.67, p < 0.001, β = 0.15]. These results suggest that the weighted average with the proportional gaze duration served as a better predictor for choice, highlighting the causal effect of gaze on choice.

Combining findings from participants’ choices and eye movements, results of Experiment 3 are consistent with the idea that the distractor first attracted bottom-up attention due to its visual salience in the display (7). However, goal-driven, top-down processes successfully suppressed its sampling by quickly disengaging attention toward task-relevant items (9), resulting in the distractor having the lowest gaze duration and a very limited effect on risky choice. Surprisingly, extreme outcomes (those with the highest or lowest ranks) were no more likely to attract initial attentional orienting than were midrange ranks (see ref. 11 for a counterexample). However, in line with our predictions, participants spent the most time looking at the high extreme outcomes (and were also most likely to revisit these items in their series of fixations), reflecting the greater probability of sampling the higher-value outcomes and their subsequent influence on choice. This is also in line with the effect of outcome distribution on choice, which again showed a pattern consistent with the idea that participants were prioritizing the highest outcomes in sampling (LS-HV > RS-HV > NS-LV). In the following section, we use computational modeling with the selective-sampling and integration model (SSIM) to test these intuitions (see SI Appendix for a test of a “stopping-rule” hypothesis that could potentially explain the patterns we found in gaze duration among ranks).

The SSIM.

The SSIM proposed by Vanunu et al. (15) describes the decision process in the gamble-array task via two steps: selective sampling—when information is collected selectively in accordance with task demands—and integration—when the sampled information is combined via averaging the displayed items or counting the number of items that are above or below the CP. Averaging is consistent with estimating the gambles’ expected values, and counting is consistent with estimating the probability of winning a larger payoff. Importantly, the SSIM assumes that people might not use all the displayed information when forming choice but may instead selectively sample items, based on goals and available cognitive resources. We illustrate this selective-sampling mechanism with the probabilistic sampling function (PSF), which defines a discrete probability of being sampled for each item in the array display according to its rank on a given scale. For example, we can assume that sampling is a function of value defined as the item’s value rank within the displayed array. Because each item has an independent probability of being sampled, the number of sampled items in a trial can vary. Note that the SSIM does not make any predictions regarding sampling order but only describes the individual probability of being sampled for each item in the display. The model simulates sampling each item like a biased coin toss in respect to the item’s probability defined by the PSF. The PSF is free to take many shapes describing various sampling policies, determined by three free parameters of curvature, symmetry, and area under the curve.

Mathematically, the PSF is an elaboration of a quadratic function in two steps. First, we define the shape of the function in Eq. 1 with the product q(X). Then, we transform q(X) into a probability vector p(X) of sampling each item, Xi, of rank i in an array (Eq. 2):

| [1] |

| [2] |

Here, z is a rescaling of ranks 1 through 8 to evenly spaced values between −1 and 1. Three free parameters (each in the range from −1 to 1) define the shape of the function: α determines the curvature, θ determines the symmetry, and β determines the area under the curve after a normalization that subtracts the minimum point in q(X) from all values in q(X). Finally, we replaced all values that exceeded the possible probability boundaries, one or zero, with the respective boundary (i.e., p[x] = min[1, p(x)] and p[x] = max[0, p(x)]). See SI Appendix for an illustration of the different shapes the PSF can take.

After the model determines which items are sampled, the subset of sampled items is integrated to produce evidence in one of two ways: by averaging (Eq. 3) or by counting (Eq. 4).

| [3] |

| [4] |

Here, j is the sampled item’s index, CP is the certain payoff, and N is the sample size. In averaging, the average of the sampled items is calculated and compared to CP. In counting, the number of sampled items above CP is compared to the number of sampled items below CP. Positive values of E indicate evidence in favor of the array, and negative values of E indicate evidence in favor of the CP. To calculate the probability of choosing the array, we transform the evidence using the logistic function:

| [5] |

where σ is an additional free parameter, ranging from 0 to 1, and controls for sensitivity to the evidence magnitude. The final free parameter λ determines the tendency to prefer one option over the other regardless of the evidence.

Finally, to describe sampling on a two-dimensional space of value rank and font rank (Experiment 2), we adapted the product q(X) in Eq. 6 to a symmetric quadratic surface.

| [6] |

Here, i is the value rank and k is the font rank. MV and MF are matrices that describe the symmetric variations in the two dimensions of value and font size, respectively, with rescaling of ranks 1 through 8 to evenly spaced values between −1 and 1. Hence, similar to the rescaled vector z in Eq. 1, MV is a copy of z across eight rows and MF is a copy of z across eight columns. By adding their squared values together, we form a three-dimensional quadratic surface, with α and θ defining its curvature and symmetry. Lastly, Eq. 2 is used to transform q(X) into a probability matrix p(X) of sampling each item, Xik, where the parameter β defines the surface’s altitude. Hence, the y-axis of the quadratic surface represents the outcomes’ value ranks, the x-axis represents the outcomes’ font ranks, and the z-axis represents the outcomes’ probability of being sampled.

We fitted the SSIM twice, once for each integration strategy (averaging and counting) and separately for each participant, font size (Experiment1), font-size difference (Experiment 2), and distractor (Experiment 3) condition. We used a bounded Nelder–Mead optimization routine (23) to search for parameter values that maximized the likelihood of each dataset. The PSF values determined the probability of sampling each item according to its rank. The sampled items were averaged or counted, and the resulting evidence was used to compute a choice probability using Eq. 5. Due to the stochastic nature of the sampling procedure, for each participant and condition, we simulated the model 100 times and optimized the parameters according to the maximum sum of log-likelihood values across trials and repetitions.

Predictions by the best-fitting model versions among conditions and experiments are represented by the asterisks in Fig. 2 A–C, showing that the SSIM often replicated participants’ choices quite accurately (with the exception of the NS-LV decrease conditions in Experiment 2). A model recovery analysis revealed a successful recovery of the SSIM predictions across conditions and experiments, and a cross-validation analysis illustrated the ability of the SSIM to fit novel data quite well (see SI Appendix for more details). Note that across conditions, participants, and experiments, we found that an averaging mechanism best explained choices for the majority of model fits across conditions, participants, and experiments (92%). We therefore focus our discussion on this mechanism in the following sections.

Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Attention in Sampling—Model Comparison.

To examine the interplay of top-down and bottom-up attention in sampling, we separately fitted and compared three versions of the model to each font-size difference condition in Experiment 2. One version assigned probability of sampling on a scale of value (Value-PSF), another assigned probabilities on a scale of font size (Font-PSF), and the third assigned probabilities along a symmetric two-dimensional space of value and font-size (2D-PSF, see Eq. 6). We did not perform model comparison on Experiment 1 because the font-size manipulation was not scaled, making it difficult for a Font-PSF model to determine how the probability would be assigned among seven values with an identical font size. We infer that the best-fitting model version indicates participants’ sampling policy: by value (top down), by font size (bottom up), or by both. The fit of each model version and the proportion of participants that were best described by each model version are shown in Table 1. Participants were more likely to sample by font size if perceptual differences were large but to sample by both dimensions when differences were small. That is, Font-PSF produced the best fit under the large font-size difference condition, and the symmetric 2D-PSF model produced the best fit under the small font-size difference condition. This result was replicated at the individual level, with the majority of participants best described by the SSIM version that produced the best fit at the group level. We therefore find evidence that both top-down and bottom-up processes influenced sampling in Experiment 2. When perceptual differences in font sizes were prominent, bottom-up attention encouraged participants to sample salient items despite font size being less relevant for the outcome of choice. However, when font sizes were similar, a top-down process, driven by the goal of winning the best outcome, encouraged the majority of participants to consider value in sampling as well.

Table 1.

Fit of the different SSIM versions in log-likelihood values and the proportion of participants that was best described by each SSIM version, between conditions and experiments

| Experiment | Model | Condition | Log-likelihood | Proportion |

| Experiment 2 | Large font-size difference | Value-PSF | −605,314 | 0.09 |

| Font-PSF | −547,766 | 0.64 | ||

| 2D-PSF | −551,666 | 0.27 | ||

| Small font-size difference | Value-PSF | −601,041 | 0.27 | |

| Font-PSF | −596,376 | 0.27 | ||

| 2D-PSF | −594,500 | 0.46 | ||

| Experiment 3 | Eight-PSF | −1,167,705 | 0.66 | |

| Nine-PSF | −1,171,605 | 0.34 | ||

The fits of the SSIM versions in Experiment 3 are aggregated across the distractor conditions.

In Experiment 3, participants were instructed that the large-font item would never be selected as the outcome of the gamble and so should be ignored. To investigate the role of top-down and bottom-up processing when the two opposed, we compared two versions of the SSIM. In both versions, attention was allocated on a scale of value. The Eight-PSF version distributed attention across eight value ranks, excluding the distractor from sampling. The Nine-PSF version distributed attention across all nine items, including the distractor. For the no distractor condition, attention was assigned across eight value ranks in both models. Consistent with the behavioral data, findings at the group and individual levels showed that the Eight-PSF model was superior (Table 1). Thus, the model that excludes the distractor from sampling was better able to account for participants’ choices, in line with our hypothesis that a top-down process would suppress the distractor in sampling when participants knew that this distractor could not be an outcome of the gamble.

Additional analysis of participants’ best-fitting PSFs, reported in SI Appendix, converges with the notion that when large-font items are potential outcomes of the gamble (Experiments 1 and 2), participants often prioritize sampling the highest ranks in value (top down) and font size (bottom up). This analysis also reveals some evidence for bottom-up attention to salient items interfering with the sampling of goal-consistent items (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Individual-level analysis of PSFs also supports the idea that sampling is affected by value but not by font size when large-font items are distractors (Experiment 3). Interestingly, the best-fitting PSFs in Experiment 3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2G) mimicked findings from the average gaze-duration values among value ranks in Fig. 2E. This result reinforces our assumption that sampling was modulated by attention, with longer gaze duration indicating higher probability of being sampled. Moreover, across participants, we found a moderate and positive correlation between the average number of fixations in a trial and the average sample size predicted by the SSIM (r[98] = 0.34, p = 0.016), consistent with the idea that the two measures tap into a common attentional mechanism. Consequently, we conclude that the SSIM’s description of how attention was deployed across the display matched with a direct measure of participants’ overt attention (eye tracking), highlighting the SSIM’s ability to capture the distribution of attention quite well.

Discussion

The current work adds evidence for bottom-up effects on risky choice. Consistent with previous studies (4, 10–14), we have shown that perceptual properties often attract attention and can increase the probability that an item is sampled and influences choice. Our advance is to show that this influence can be overridden by a top-down process if the stimulus is a distractor and has no value for choice. This finding is important because it challenges the view that bottom-up effects on choice are purely “automatic” or “involuntary,” instead suggesting that such effects are ultimately governed by top-down control. Returning to our earlier supermarket example, if we know that the visual saliency of a snack’s logo is independent of its quality (snacks with salient logos may sometimes be tasty and sometimes bland), we may nevertheless use a top-down strategy in which rapid, bottom-up attentional responses to visually salient stimuli are harnessed in order to carry out fast and frugal sampling under bounded conditions (e.g., when under time constraint).

Converging evidence from eye-tracking measures supports our interpretation by shedding light on how top-down and bottom-up attention were deployed across the visual field. Consistent with our predictions, the visually salient distractor was most likely to be fixated first among all items—consistent with the idea that bottom-up attention was likely to be deployed first on the most salient item in the display (7). However, the distractor also exhibited the lowest gaze duration among all items, suggesting that a top-down process was responsible for sampling the item or quickly disengaging attention toward relevant potential outcomes (9). In line with this theory, gaze duration for the high extremes was the highest, reinforcing the notion that a goal-driven process prioritizes high extreme outcomes in sampling (ref. 15; see also refs. 16–19).

Modeling results presented additional evidence to support these interpretations, showing that a model in which the likelihood of sampling an outcome was a function of its font-size rank produced the best account of participants’ choices when differences in font sizes were prominent (Experiment 2), while a model that suppressed sampling of the large-font-size item produced the best fit when this item was framed as a distractor (Experiment 3). Moreover, it seems that people often sampled only part of the displayed information, with the probability that an item was sampled being modulated by top-down and bottom-up influences. In particular, high gains and low losses were most likely to be sampled, reflecting goal-consistent processing. However, it seems that the most visually salient item in the display occasionally interfered with sampling the most goal-consistent item in the display—but only if the salient item described a potential outcome (see SI Appendix for detailed analyses).

In line with our model’s predictions that sampling would be determined by attention, the SSIM’s representation of how attention is deployed among items (illustrated by the probability sampling function) matched with the time participants spent looking at each item. In future studies in which complete sampling of all relevant information is not possible and eye-tracking measures are unavailable (e.g., online studies in which the display time of the stimuli is constrained), one could use the SSIM to draw inferences about the distribution of attention. For example, the SSIM could be extended to test the distribution of attention across various stimulus features like location on the screen, intensity of color, size, or orientation. One could also broaden the scope of the model (beyond risky choice) to use the probability sampling function to describe the probability of an item being retrieved from memory as a function of properties such as familiarity, sequential order, or affective value.

Converging evidence across experiments suggested that items rendered physically distinctive by virtue of being presented in a larger font were more likely to attract participants’ attention first. We have interpreted this finding as consistent with a bottom-up effect of visual salience on attention. However, in addition to influencing visual salience and distinctiveness, our manipulation of font size may also have affected the readability of items. As such, it remains unclear whether effects on capture of attention reflected an influence of visual saliency alone or in combination with the relative ease of reading items in larger font size. A contribution of readability is possible because people often prefer to process more accessible information (24, 25), and high readability might also initiate automatic processes of reading (26), which could complement bottom-up effects of visual salience on attention. Future studies could attempt to disentangle these effects by varying visual salience independently of readability: for example, by manipulating the color of the salient item rather than its size. Nevertheless, whether it was visual salience or readability that attracted initial attention, neither feature was sufficient to modulate choice if sampling the more salient/readable item conflicted with participants’ goal (Experiment 3). This result demonstrates top-down processes as the final arbiter in collecting information to determine risky choice.

The current study tested risky choice, for which the decision criterion is subjective (also known as preferential choice [i.e., there is no right or wrong answer; see ref. 27]) and the numbers’ magnitudes determine the reward (i.e., winning the best outcome). However, the conclusions we draw here may also apply to perceptual choices, for which the decision criterion is objective and the numbers’ magnitudes have no implications for the reward [e.g., a task in which participants must decide whether the average of an array of numbers is smaller or larger than a known reference value and receive a fixed reward for correct responses (15)]. This is because limited sampling of a subset of the highest-valued items in the array would yield a greater perceived mean value than averaging across all items (or a random selection of items). In support of this notion, previous work has shown similar trends of prioritizing these high-extreme values in both preferential and perceptual choices (11, 15, 16, 19, 28). Future studies should aim to further examine whether distinctive perceptual features that are less relevant to the required choice would have a similar impact on perceptual and preferential choice and whether the current findings could be extended beyond numerical evaluations, such as to the case of estimating the average shape or color of multiple elements (29, 30) or the average expression in a set of faces (31).

Conclusion

We find that risky choice is governed by a top-down process that prioritizes information that is most consistent with a goal while suppressing irrelevant information that has no impact on the outcome of choice. However, the initial direction of attention across the visual field, which feeds the top-down process with information, is determined by bottom-up processes driven by the visual saliency of the stimulus in the environment. Critically, when the two mechanisms of top-down and bottom-up attention align (e.g., a salient stimulus that is tied to a potential outcome), bottom-up effects on option selection occur because the perceptual properties of a salient stimulus increase its chances of being included in choice. However, when the two mechanisms oppose (e.g., a salient stimulus that is a distractor and has no value for choice), top-down control suppresses bottom-up effects on choice. Returning to the consumer’s dilemma, the current findings suggest that in an environment in which there is competition for one’s attention, like a supermarket shelf, a distinctive logo design of a snack might initially attract the consumer’s gaze. However, it would not be enough to induce selection if the brand name is associated with a poor or unfamiliar product, because choice seems, ultimately, to be governed by top-down control.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1.

Participants and design.

A total of 79 first-year students from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) (55 females, age 18 to 31 y, M = 19.44) participated for course credit and an incentivization bonus. We used a 2 (gamble type: gains, losses) × 3 (large-font value: high-value large-font, low-value large-font, all values same-font) × 3 (outcome distribution: left-skew high-variance, no-skew low-variance, right-skew high-variance) design. The gamble type factor was implemented between subjects (39 and 40 participants in gains and losses groups, respectively); other factors were within subjects. All research reported in this article was approved by the UNSW Sydney Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel (Psychology), and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participating.

Materials.

Six values for the CP were drawn randomly from a uniform distribution, U(50,60), one for each experimental block. For each trial, an array of eight two-digit numbers and eight two-letter strings were randomly placed on a screen within an invisible 10 × 10 grid of 100 equally sized rectangles (192 × 108 pixels each), with no stimuli displayed within the central four grid locations or in the first or last column or row of the grid (Fig. 1A). For each participant, we created 324 sets of numbers by randomly drawing (for each set) eight items from one of nine Gaussian distributions with lower and upper boundaries of 10 and 99, respectively. The mean (µ) of the distributions used in each block was set according to the value of CP in that block and was either below (μ∼CP-3), above (μ∼CP+3), or approximately equal (−1 ≤ μ − CP ≤ 1). The distributions had either left skew (measured with the Fisher–Pearson standardized third moment coefficient g1; see ref. 32) and high variance (g1 ≤ 0.4, SD∼15; LS-HV), no skew and low variance (−0.4 ≤ g1 ≤ 0.4, SD∼5; NS-LV), or right skew and high variance (g1 > 0.4, SD∼15; RS-HV). We allowed a deviation of ±0.5 in the arrays’ statistics (μ and SD). Based on previous findings (15), we expected the shape of the array distribution to systematically influence participants’ choices. Consider the following three example arrays, one from each outcome distribution condition:

The overall expected values of these arrays are equal (MLS-HV = MRS-HV = MNS-LV = 53); hence, if participants’ choices are based on averaging all items in the array, then we would expect no difference in choice between conditions. However, if participants consider only the highest subset of items in each array (and ignore the lowest items), then differences between conditions emerge. For example, if only the highest six outcomes in each array are considered (indicated in bold in the examples above), the resulting subjective value of LS-HV would be greatest (M = 60.17), followed by RS-HV (M = 58.50) and NS-LV (M = 55.00). This pattern holds more generally: prioritizing the highest payoffs in sampling should produce systematic differences in choice among arrays with different outcome distributions (but equal overall means) due to changes in the dispersal of extreme and midrange outcomes across the array. Specifically, the two lowest values in the left tail are usually the smallest for LS-HV, followed by RS-HV, and are the largest for NS-LV. This is because the two lowest values are smaller in arrays with high rather than low variance and in arrays that are skewed to the left rather than skewed to the right. Consequently, disregarding these values in sampling should increase the subjective value of LS-HV over RS-HV and NS-LV. These predictions are consistent with previous findings, in which choice for the array increased if the variance of the display was high or left-skewed (15). The same logic applies in losses, in which we expected participants to focus on sampling a subset (∼6 items) of the lowest values in the display, resulting in the largest subjective value for NS-LV (M = 51), followed by LS-HV (M = 50.57) and RS-HV (M = 45.83). Importantly, we expected participants to approach high subjective values in gains but to avoid high subjective values in losses. Therefore, we anticipated that the influence of outcome distribution on choice would be manifest as a pattern wherein probability of choosing the array (versus the certain outcome) under gains followed the order LS-HV > RS-HV > NS-LV, while in losses, it would follow the order RS-HV > LS-HV > NS-LV (see SI Appendix for more details).

The number of items in each array above and below CP was balanced to discourage participants from using an alternative strategy in which the probability of winning an outcome larger than CP (i.e., proportion of items greater than CP) determines choice, rather than the gambles’ expected values (see The SSIM for more information). Fig. 1B presents illustrative frequency plots of outcomes displayed in the array generated using this procedure for each of the distribution conditions (LS-HV, NS-LV, and RS-HV).

In one-third of the trials, the font size of the highest value (high-value larger-font) or the lowest value (low-value larger-font) in the array was set to 130 (in “David” font), while the rest of the values were set to 65 (Fig. 1A). In the remaining trials, all values had the same font size of 65 (all values same-font).

The number of trials was equally divided among the nine conditions of outcome distribution and large-font value. The difference between µ and CP was balanced within blocks. The letter strings were randomly selected from the English alphabet and intended to impose difficulties in scanning the array.

Procedure.

Participants were instructed that the array represented a gamble with the numbers as monetary payoffs or penalties, depending on the gamble-type condition (i.e., gains or losses). They were asked to choose between two options: either to receive (lose) a CP or to take a gamble and receive (lose) one of the eight amounts displayed in the array, with equal probability. Participants were also informed that some numbers would appear in larger fonts but that all items had an equal probability of being picked as the gamble’s payoff. In the gains condition, they were told that at the end of the experiment, a random trial would be selected by the computer and that 10% of that trial’s payoff would be granted to them as a reward. In the losses condition, participants started with $10 AUD and were told that at end of the experiment, 10% of an outcome from a random trial would be deducted from this starting balance. Finally, all participants were instructed that the letters in the array had no meaning. Following the instructions, a short practice phase was given in which an example CP was initially displayed, followed by nine example trials that corresponded to each of the experimental conditions described in Materials and Methods, Materials.

In the experimental trials, each block started with a display of the CP and participants were instructed to remember it, since this value would apply for all 54 trials in the block. Each trial started with a display of a fixation cross for 0.5 s, followed by the array display for 2 s before disappearing. To make their choice, participants pressed one of two buttons—one for the gamble and one for the CP—which were displayed at the bottom of the screen throughout the trial. Participants had unlimited time to make their choice. Next, the outcome of the participant’s choice was displayed in the center of the screen as feedback (i.e., the value of CP or a random draw from the array), and a high- or low-pitched tone was played to indicate whether the outcome received was higher or lower than the outcome they had forgone, respectively. If the outcome of the chosen option was better than the forgone outcome, then participants heard a high tone, and if the chosen outcome was worse, then they heard a low tone. In effect, on each trial, the auditory feedback was based on a comparison between a random draw from the array and the CP regardless of the participant’s choice. Overall, participants completed six experimental blocks of 54 trials. Each block contained six trials from each of the outcome distribution × large-font value conditions, with trial order randomized within blocks.

Experiment 2.

Participants, design, materials, and procedure.

A total of 43 first-year students from the UNSW (25 females, age 18 to 28 y, M = 19.72) participated for course credit and an incentivization bonus. We used a 2 (font-size order: font-size increase, font-size decrease) × 2 (font-size difference: large font-size difference, small font-size difference) × 3 (outcome distribution: LS-HV, NS-LV, RS-HV) within-subjects design.

The design, materials, and procedure were identical to Experiment 1 with the following exceptions: we only tested participants under the “gains” framing, and we implemented a scaled font-size manipulation in which font size either increased with rank order (i.e., font size increased as a function of the value of each item; font-size Increase condition) or decreased with rank order (i.e., the lowest value had the largest font size; font-size decrease condition; Fig. 1A). Font sizes were randomly drawn from two Gaussian distributions with the same mean (µ∼70) but with either a small font-size difference (SD∼9) or a large font size difference (SD∼27) among values (with ±0.5 deviation allowed); these font sizes were then assigned to array items in accordance with the font-size order condition. Minimum and maximum font-size values were set to 30 and 120 to ensure that all numbers were readable and did not exceed the boundaries of the display grid (a separate manipulation check, in which participants had to read out briefly presented numbers, revealed 100% accuracy for a font size of 30—confirming that our minimum font size was clearly legible). Overall, participants completed six experimental blocks of 72 trials. Each block contained six trials from each of the font-size order × font-size difference × outcome distribution conditions, with trial order randomized within blocks.

Experiment 3.

Participants, design, materials, and procedure.

A total of 50 first-year students from the UNSW (30 females, age 17 to 22 y, M = 18.94) participated for course credit and an incentivization bonus. We used a 3 (distractor: high-value distractor, low-value distractor, no distractor) × 3 (outcome distribution: LS-HV, NS-LV, RS-HV) within-subjects design.

The design, materials, and procedure were similar to Experiment 1 but without the loss condition. Critically, participants were informed that, if the display contained an item in a larger font than others, this large-font item would never be selected as the outcome of the gamble (hence the large-font item was a distractor that should be ignored).

Across trials, eight payoffs—extracted from one of the nine Gaussian distributions used in Experiment 1—were displayed in the array with a font size of 55 (in “Times New Roman” font). For two-thirds of the trials, an additional distractor number was displayed in the array with a large font size of 110. The value of the distractor was sampled from a uniform distribution ranging from [10] to the array’s minimum payoff for the low-value distractor condition and from the array’s maximum payoff to [99] for the high-value distractor condition. For the remaining trials, no distractor appeared in the array. Thus, in the low-value distractor and the high-value distractor conditions, nine numbers were displayed in the array (eight payoffs and a distractor), while eight numbers were displayed in the no distractor condition. Critically, if sampled when evaluating the array, the distractor would increase the array’s mean (i.e., expected value) under the high-value distractor condition and decrease it under the low-value distractor condition compared to the no distractor condition, potentially leading to significant differences in probability of choosing the array between the conditions. Participants completed seven experimental blocks of 54 trials. Each block contained six trials from each of the distractor × outcome distribution conditions.

Eye tracking.

Participants’ eye movements were recorded using a Tobii Pro Spectrum eye tracker (sample rate 600 Hz) mounted on a 23-inch monitor (1,920 × 1,080 resolution, 60 Hz refresh rate). The participants’ head position was stabilized using a chinrest 60 cm from the screen. For each participant, the tracker was calibrated at the beginning of the session. Each trial began when participants had accumulated 0.5 s of gaze dwell time on the fixation cross, ensuring that gaze was central when the array appeared on each trial. Gaze was defined as being on an item if it fell anywhere in the area of interest (AOI) defined by the grid rectangle containing that item (see Materials and Methods, Experiment 1). For each trial, the proportional time spent looking at each numeric item in the array (which we term gaze duration) was calculated by dividing the time spent looking at that item by the total time spent looking at all numbers in the display (i.e., excluding gaze on bigrams and empty AOIs).† Gaze durations were then recoded as a function of the value rank of the item in the display (highest rank to lowest rank, with distractors coded separately) and then averaged across trials. In cases in which values repeated in the array (example in Fig. 1A), the appropriate ranks were allocated randomly among the repeating values. We also analyzed the item that was fixated first in each trial (first fixation), defined as the first number within whose AOI the participant’s gaze remained for more than 20 ms consecutively (i.e., excluding fixations on bigrams). We then calculated the proportions of first fixations by dividing the number of trials in which each value rank or distractor was fixated first by the total number of trials (for value ranks) or the total number of trials in which a distractor appeared (for distractors). We also calculated the proportion of repeated fixations for each value rank and the distractor by counting the number of times participants fixated on an item more than once and then averaged it across the respective total number of trials. Finally, we calculated the average value rank across trials for each position within the sequential fixation order. That is, we calculated the average value rank for outcomes that were fixated first, second, etc. (excluding fixations on the distractor and bigrams).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Australian Government International Research Training Program Scholarship to Y.V. and an Australian Research Council Discovery Project to B.R.N. (DP160101186). We thank Chris Donkin for useful discussions and feedback on this project.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Since there is no consensus method to calculate standardized effect sizes in mixed-effects models, we report the partial eta squared estimates from repeated measures ANOVA tests with the same variables as in the mixed-effects models.

†A similar analysis for gaze duration with the raw data (i.e., not normalized to the total gaze duration among the numerical values) produced very similar results.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2025646118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Behavioral data (responses and eye-movements) and the computational modeling codes have been deposited in Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/54m3q/.

Change History

September 24, 2021: The article text has been updated.

References

- 1.Gluth S., Kern N., Kortmann M., Vitali C. L., Value-based attention but not divisive normalization influences decisions with multiple alternatives. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 634–645 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krajbich I., Armel C., Rangel A., Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1292–1298 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith S. M., Krajbich I., Gaze amplifies value in decision making. Psychol. Sci. 30, 116–128 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towal R. B., Mormann M., Koch C., Simultaneous modeling of visual saliency and value computation improves predictions of economic choice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E3858–E3867 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner M. I., Orienting of attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 32, 3–25 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe J. M., Cave K. R., Franzel S. L., Guided search: An alternative to the feature integration model for visual search. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 15, 419–433 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itti L., Koch C., Computational modelling of visual attention. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 194–203 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treisman A. M., Gelade G., A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognit. Psychol. 12, 97–136 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theeuwes J., Top-down and bottom-up control of visual selection. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 135, 77–99 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotaling J. M., Jarvstad A., Donkin C., Newell B. R., How to change the weight of rare events in decisions from experience. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1767–1779 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunar M. A., Watson D. G., Tsetsos K., Chater N., The influence of attention on value integration. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 79, 1615–1627 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milosavljevic M., Navalpakkam V., Koch C., Rangel A., Relative visual saliency differences induce sizable bias in consumer choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 22, 67–74 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orquin J. L., Lagerkvist C. J., Effects of salience are both short- and long-lived. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 160, 69–76 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orquin J. L., Perkovic S., Grunert K. G., Visual biases in decision making. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 40, 523–537 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanunu Y., Hotaling J. M., Newell B. R., Elucidating the differential impact of extreme-outcomes in perceptual and preferential choice. Cognit. Psychol. 119, 101274 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glickman M., Tsetsos K., Usher M., Attentional selection mediates framing and risk-bias effects. Psychol. Sci. 29, 2010–2019 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludvig E. A., Madan C. R., McMillan N., Xu Y., Spetch M. L., Living near the edge: How extreme outcomes and their neighbors drive risky choice. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147, 1905–1918 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvig E. A., Madan C. R., Spetch M. L., Extreme outcomes sway risky decisions from experience. J. Behav. Decis. Making 27, 146–156 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsetsos K., Chater N., Usher M., Salience driven value integration explains decision biases and preference reversal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9659–9664 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanunu Y., Pachur T., Usher M., Constructing preference from sequential samples: The impact of evaluation format on risk attitudes. Decision (Wash. D.C.) 6, 223–236 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu S., Han S., Attentional capture is contingent on the interaction between task demand and stimulus salience. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 71, 1015–1026 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spehar B., Owens C., When do luminance changes capture attention? Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 74, 674–690 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelder J. A., Mead R., A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 7, 308–313 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alter A. L., Oppenheimer D. M., Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 13, 219–235 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zilker V., Hertwig R., Pachur T., Age differences in risk attitude are shaped by option complexity. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149, 1644–1683 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLeod C. M., Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychol. Bull. 109, 163–203 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutilh G., Rieskamp J., Comparing perceptual and preferential decision making. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 23, 723–737 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum D., de Gardelle V., Usher M., Ensemble perception: Extracting the average of perceptual versus numerical stimuli. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 83, 956–969 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Gardelle V., Summerfield C., Robust averaging during perceptual judgment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13341–13346 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michael E., de Gardelle V., Nevado-Holgado A., Summerfield C., Unreliable evidence: 2 sources of uncertainty during perceptual choice. Cereb. Cortex 25, 937–947 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haberman J., Whitney D., The visual system discounts emotional deviants when extracting average expression. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 72, 1825–1838 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doane D. P., Seward L. E., Measuring skewness: A forgotten statistic? J. Stat. Educ. 19, 1–18 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Behavioral data (responses and eye-movements) and the computational modeling codes have been deposited in Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/54m3q/.