Abstract

Advances in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) biology now allow the generation of organoids that resemble different regions of the gastrointestinal tract. Generation of region-specific organoids has been facilitated by developmental biology studies carried out in model organisms such as mouse, frog and chick. By mimicking embryonic development, hPSC-derived human colonic organoids (HCOs) can be generated through a stepwise differentiation, first into definitive endoderm (DE), then into mid/hindgut spheroids which are then patterned into posterior gut tissue which gives rise to HCOs following prolonged in vitro culture. HCOs undergo transitions similar to those observed in the developing colon of model organisms and human embryos. HCOs develop into tissue that resembles fetal colon on the basis of morphology, gene expression and presence of differentiated cell types. Generation of HCOs without the proper training or expertise can be a daunting task. Here, we describe a detailed protocol for differentiating hPSCs into HCOs, we include suggestions for troubleshooting these differentiations, and we discuss experimental design considerations. We have also highlighted the key advantages and limitations of the system.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade there has been an explosion of new organoid models that allow for three-dimensional modeling of many endoderm derived tissues including: small intestine, colon, stomach, liver, lung and esophagus (Bartfeld et al., 2015; Dye et al., 2015; Huch et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2011; McCracken et al., 2017, 2014; Munera et al., 2017; Sato et al., 2011; Spence et al., 2011; Trisno et al., 2018). Organoids can be generated from either patient biopsies or through the directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Despite differences in starting material, most organoid models rely on culture conditions which were initially developed for the growth of single Lgr5+ mouse intestinal stem cells into organoids (Sato et al., 2009). This seminal work was instrumental to development of small intestinal, stomach, colon and esophageal organoids from hPSCs. Of note, other organoid models have been developed which allow the growth of primary tissue into organoids containing stromal components (Neal et al., 2018; Ootani et al., 2009).

We previously established a protocol for the generation of human colonic organoids (HCOs) from hPSCs (Munera et al., 2017). The protocol is based on work by Spence et al. who developed a protocol for generation of human intestinal organoids (HIOs) from hPSCs (Spence et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2017). HCOs are induced using a transient activation of BMP signaling on Days 7–10 of the differentiation, which induces posterior homeobox (HOX) genes and confers colonic identity on the gut tube cultures. Generation of HIOs and HCOs can be difficult for newcomers to the field. In this chapter we describe a detailed protocol with emphasis optimization and validation at each stage of the differentiation. In addition, we give a brief history of the foundational studies and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of this system.

2. Applications of human colonic organoids

2.1. Medical need

In terms of disease burden, the colon is the most highly affected region of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC), are estimated to affect 1.4 million Americans (Peery et al., 2012). Current treatment options are of variable benefit to the patient population as a whole and often have severe complications. Regenerative medicine is a promising approach for disease treatment. In the case of IBD, generation of colon tissue in vitro (HCOs) could provide material for transplantation into patients. In fact, proof-of-concept for this approach has been demonstrated in a mouse model of colitis where colonic organoids generated from adult colonic stem cells were able to replace damaged mucosa (Yui et al., 2012). More recent studies have demonstrated that expanded mouse fetal intestinal progenitors and human colonoids could also replace damaged colonic mucosa (Fordham et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2018). Human fetal intestine is not an ideal source of transplantable materials because of ethical considerations. HIOs and HCOs from induced pluripotent stem cells can be generated in an isogenic manner and they grow robustly in many different conditions because they contain mesenchyme. For example, HCOs grow and mature in the kidney capsule whereas intestinal fetal progenitors and human colonoids do not. It’s likely that the mesenchyme in HCOs secretes factors that enhance the organoid survival following transplantation.

The fact that colonic organoids can model human colon at a smaller scale opens new horizons for drug screening. For instance, HCOs generated by Crespo et al. from iPSCs of FAP patients were used for drug testing against the hyperproliferative activity of WNT signaling caused by germline mutations in the APC gene (Crespo et al., 2017). The promising results from the study support the potential of HCOs platform in evaluating drug candidates for the treatment of colorectal diseases.

2.2. Research need

Owing to the large number of diseases affecting colon, scientists have attempted to develop numerous models in order to investigate the molecular physio-pathological mechanisms of these diseases. Besides the contribution of animal models, the recent advances in organoid technologies have revolutionized the study of gastrointestinal (GI) epithelium during development and disease. Unlike 2D systems which lack cellular complexity, organoids provide a complex cellular environment with cell-extracellular and cell-cell interactions including epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Not only is this system experimentally tractable, for example, via CRISPR gene editing, gene overexpression and by adding growth factors and small molecules to the media, but it is also ideal for high-throughput screens and modeling certain human disease phenotypes that are absent in mice (Li & Izpisua Belmonte, 2019) (Sanger, Holbrook, & Andrews, 2011). More importantly, organoids can be generated from human induced polypotent stem cells (hiPSCs) of patients harboring specific mutations. For instance, human colonic organoids were generated from iPSCs of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients which have a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene exhibited an increase in WNT signaling and epithelial cell hyperproliferation, in comparison to wild type organoids (Crespo et al., 2017). Recently, HCOs were co-transplanted with human enteric neural crest-derived cells (ENCCs) into NOD/SCID mice to study the effect of the hedgehog pathway activation on enteric neuron maturity. To this aim, gut tube spheroids were patterned into HCOs in the presence of ENCCs and harvested for analysis or transplanted into the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice. Interestingly, while neuronal differentiation was observed in vitro in areas near the epithelium, the in vivo transplantation of HCOs-ENCCs promoted more NC maturation as indicated by the appearance of neurons and glia in the submucosa and the myenteric zones of the smooth muscle layers (Lau et al., 2019).

HIOs and HCOs reflect elements of fetal colon development making them ideal for studying human gut development. HIOs and HCOs have provided new insights into regional patterning of the intestinal epithelium during development. For instance, the dose and duration of exposure to WNT and FGF4 were found to control the regional identity of gut tube spheroids toward either proximal or distal small intestine (Tsai et al., 2017). We have previously demonstrated that a transient BMP2 treatment patterns gut tube spheroids into colonic organoids expressing a posterior HOX code associated with colonic fate (Munera et al., 2017). The resulting HCOs express the chromatin modifying nuclear protein SATB2 (Special AT-Rich Sequence-Binding Protein 2) and contain colon-specific goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells (EECs). In contrast, HIOs lack SATB2, express the proximal intestinal markers GATA4 and PDX1, and contain small intestinal EECs and Paneth cells.

Besides studying mechanisms of anterior-posterior patterning, insights about the differentiation of region-specific EECs have also been revealed from studies on HIOs and HCOs. This rare population of cells within the intestinal epithelium form the largest endocrine organ and secretes multiple hormones critical for controlling a variety of physiological functions in the GI tract. Using a Neurogenin 3 (NEUROG3)-inducible system, Sinagoga et al. were able to determine factors affecting the development of specific EEC subtypes using hPSCs derived organoids (Sinagoga et al., 2018). More about human gut development is yet to be revealed with the fast-growing organoid field.

2.3. Discovery of human colonic organoids (HCOs)

In 2011, the first protocol for generating human intestinal organoids (HIOs) from hPSCs was published (Spence et al., 2011). The group differentiated hPSCs into DE which was then exposed to FGF4 and WNT3A to form gut tube spheroids. HIOs were generated by culturing these spheroids under the culture conditions developed in the Clevers lab which include embedding in a 3D extracellular matrix (Matrigel®) and supplementing the culture media with R-spondin1, EGF and Noggin (Sato et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2011).

As for colonic organoids, we have recently reported the successful generation of HCOs through the direct differentiation of hPSCs, in a manner that was similar to HIOs, but with important modifications as described below. This protocol was successfully adopted by Lau et al. who constructed and innervated HCOs to study human enteric neural differentiation from hPSCs (Lau et al., 2019) (see Section 2.2).

3. Overview of HCO differentiation protocol

3.1. Definitive endoderm (DE)

The first step in generating HCOs is generating a DE monolayer. Activin A, a TGF-β super-family member which mimics the action of NODAL, was shown to induce an efficient differentiation of hPSC into DE that expresses SOX17 and FOXA2 (D’Amour et al., 2005; Spence et al., 2011). Activin A treatment for 3 days (with increasing serum concentration) induced gene expression changes which were similar to DE differentiation that occurs during vertebrate gastrulation. Furthermore, when transplanted under the kidney capsule of SCID mice, DE cells generated intestine-like tissue expressing CDX2 and Villin as well as liver-like tissue expressing hepatocyte-specific antigen (HSA). Although, these structures weren’t fully mature, the finding indicated that DE cells are capable of differentiating into foregut and mid-hindgut organs (D’Amour et al., 2005).

3.2. Mid-hindgut differentiation

Three-day treatment with Activin A results in a plastic DE capable of giving rise to both foregut and mid-hindgut fates. Following 3 days of DE generation, treatment of the DE monolayer with high levels of WNT and FGF4 for 4 days leads to mid-hindgut specification. Within this time period, epithelial tubes expressing the intestinal marker CDX2 begin to form indicating a morphogenic process. Gut tube spheroids, which are 3D structures that bud off the monolayer and tubes, appear as free-floating structures in the media usually within 1–2 days from WNT3A and FGF4 treatment (Spence et al., 2011).

3.3. Posterior patterning of gut tube spheroid into HCOs (Days 7–10)

Mid/hindgut spheroids can develop into intestine-like tissue if cultured in conditions developed for growth of mouse intestinal organoids (McCracken, Howell, Wells, & Spence, 2011; Sato et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2011). For generating HCOs, we also plated gut tube spheroids into a Matrigel® droplet to enable their three-dimensional growth and added the basic gut medium supplemented with EGF and BMP2. We found that a 3-day period of patterning is sufficient to differentiate gut tube spheroids into colonic organoids (Munera et al., 2017). Activation of BMP signaling induces the expression of BMP target genes such as MSX2 and posterior HOX genes such as HOXA13 and HOXD13. BMP treatment induces growth arrest in the majority of gut tube spheroids so plating high numbers of mid/hindgut spheroids is essential for generating sufficient material for analysis. After 3 days of patterning, the culture medium is switched to basic gastrointestinal growth medium with EGF for 2 weeks.

3.4. Passaging stage (Day 21)

Because HCOs grow significantly during the 14 days after patterning, the Matrigel® layer starts to degrade and HCO become crowded. Therefore, passaging around this time is required to ensure proper growth and maintenance of the organoids. During this time period, spheroids grow in volume and form a pseudostratified epithelium that is ensheathed by the co-differentiating mesenchyme. At this stage, posterior HOX genes are still expressed at higher levels compared to control (CTRL) organoids and Noggin treated HIOs (NOG HIOs).

3.5. Cytodifferentiation (Day 21–35)

Following extended growth, HCOs undergo maturation and transition from a pseudostratified epithelium to a simple columnar epithelium. By Day 35, colon-specific cell types are observed, such as colon-enriched MUC5B expressing goblet cells. In addition, HCOs are competent to generate colon-specific INSL5+ enteroendocrine cells in response to induced expression of NEUROG3. HCOs generated in vitro can be transplanted into the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice allowing for further maturation of HCOs including the formation crypts and development of smooth muscle layers (Munera et al., 2017).

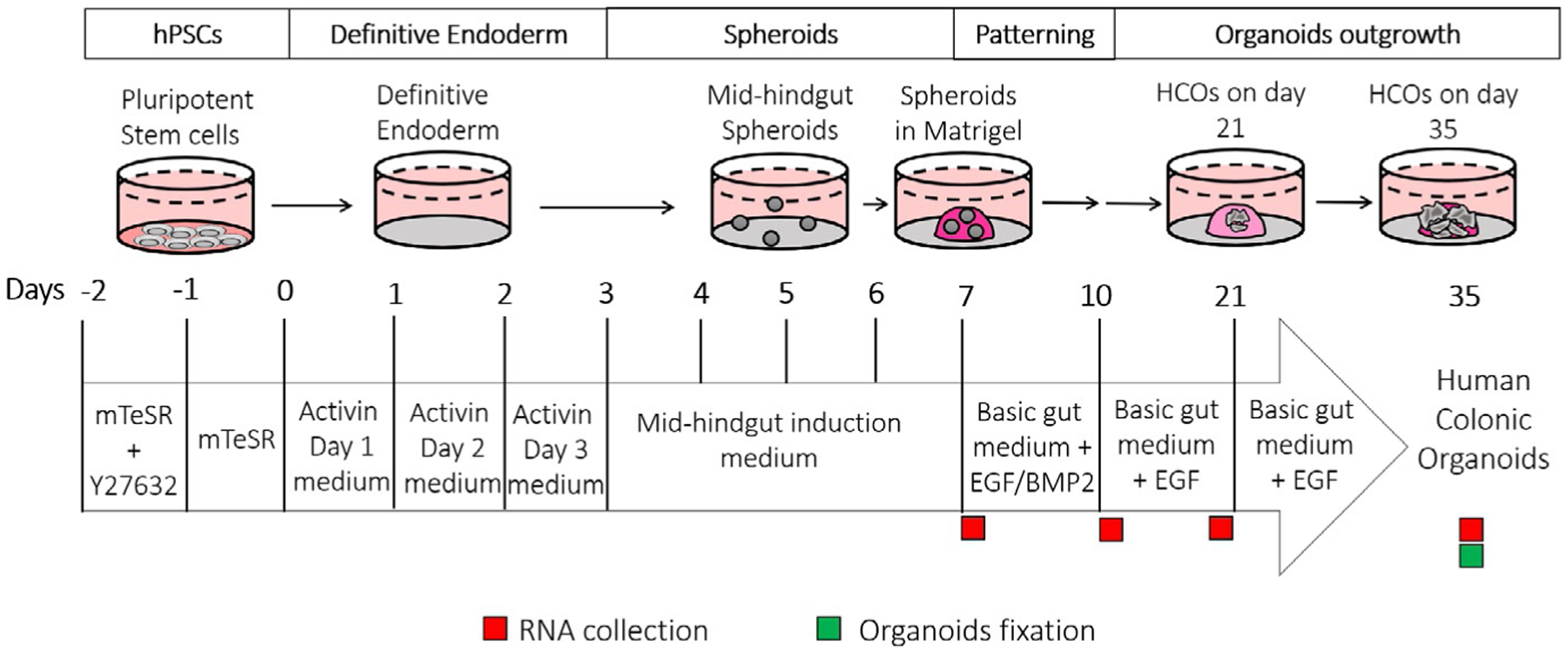

Here are the key steps for generating HCOs as depicted in Fig. 1:

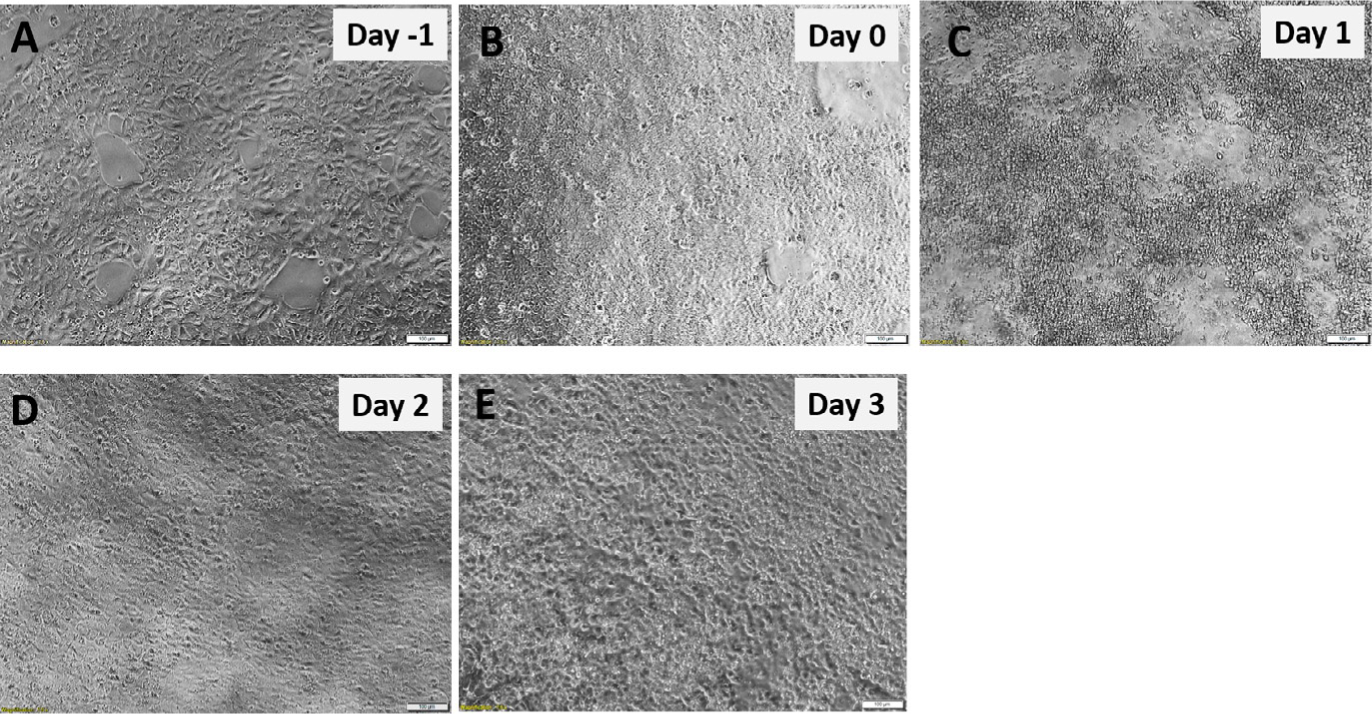

hPSCs are plated on Matrigel® coated plates and differentiated into definitive endoderm (DE) using Activin A for 3 days (Fig. 2) with BMP4 added on the first day of Activin A treatment.

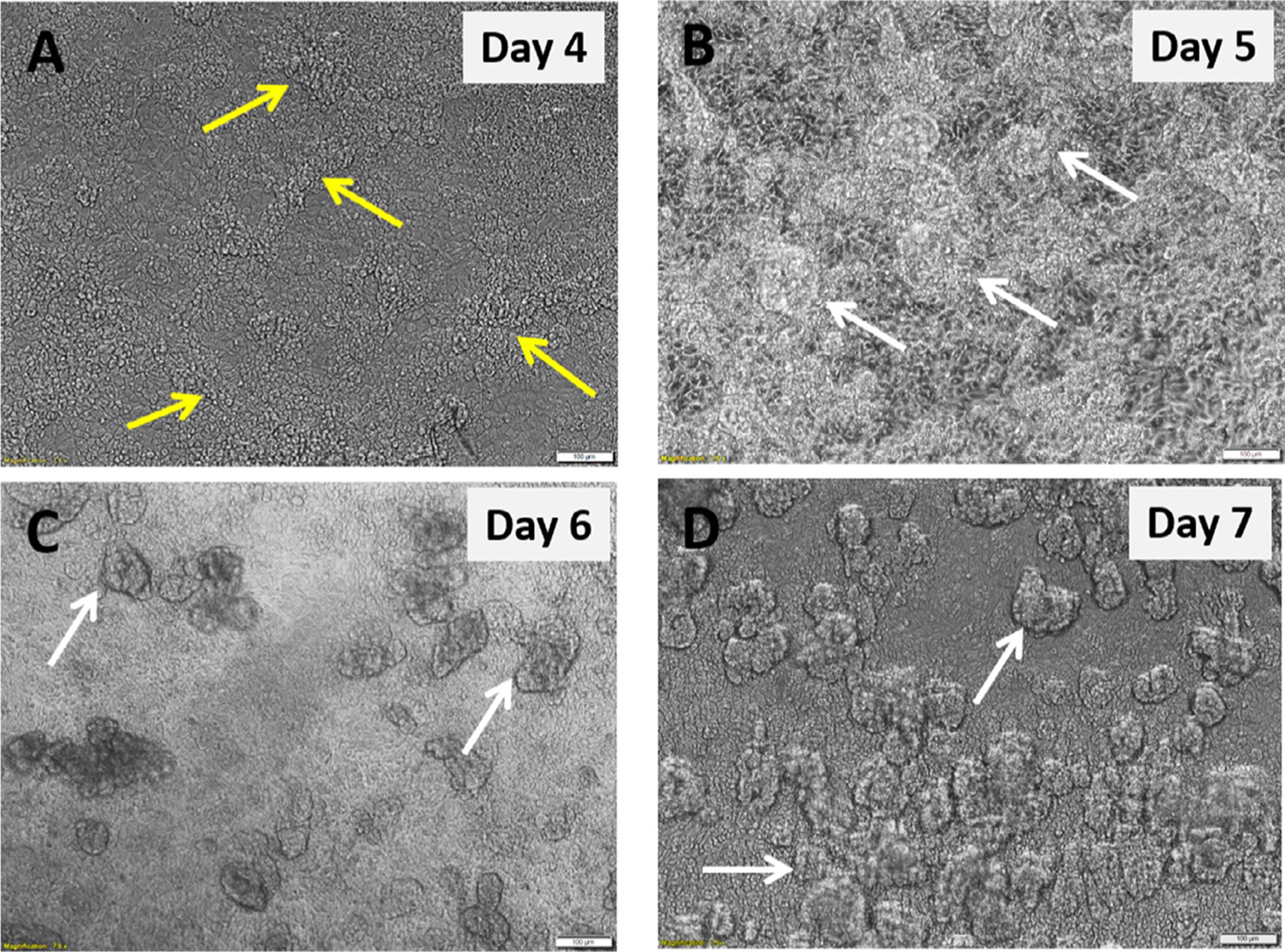

The DE monolayer is then treated with GSK3B inhibitor CHIR90221 and FGF4 for 4 days to generate free-floating mid/hindgut tube structures called spheroids (Fig. 3).

Spheroids are plated into a Matrigel® bubble, patterned with BMP2 into HCOs for 3 days then BMP2 is removed and HCOs are grown for an additional 11 days.

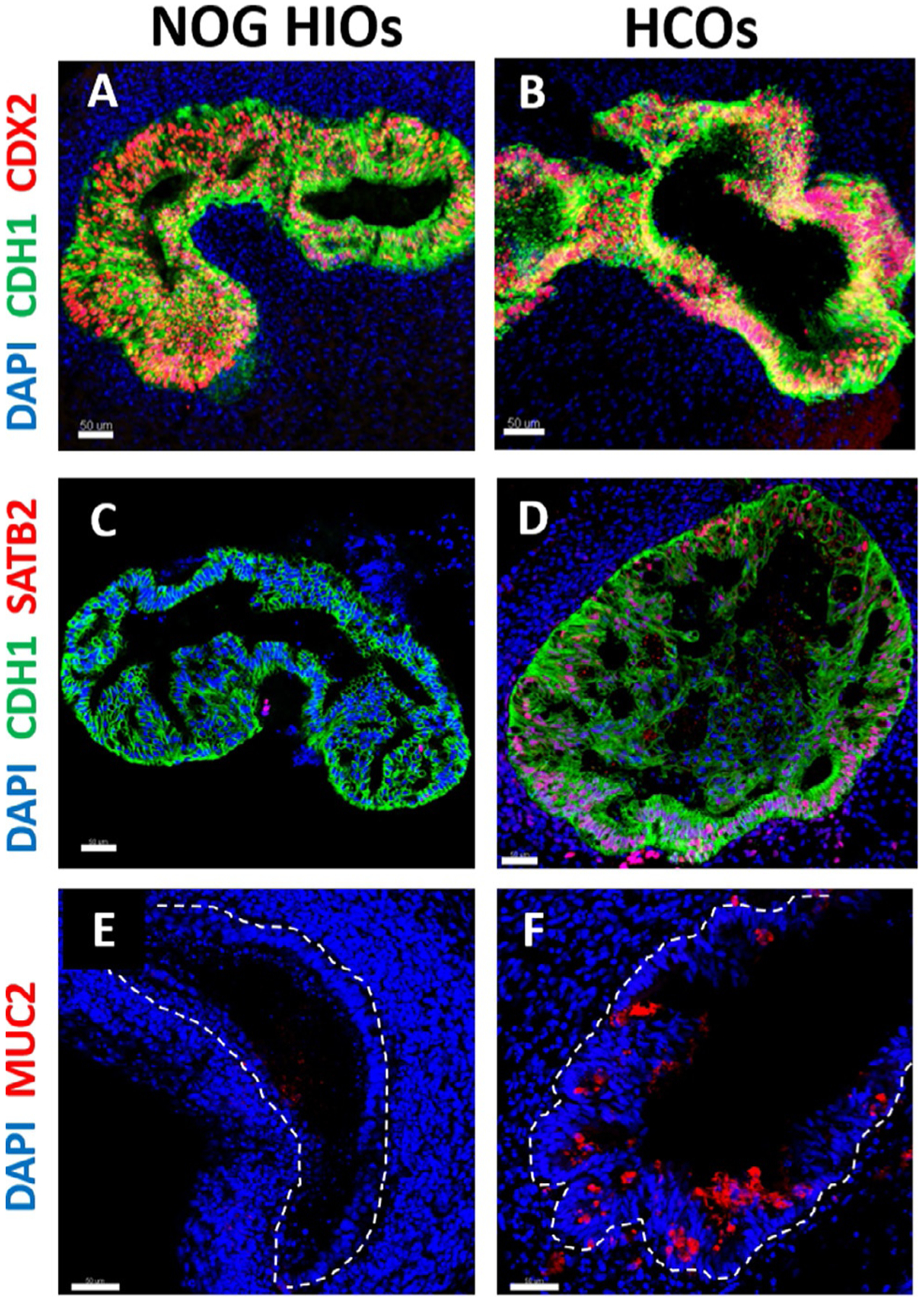

At Day 21, HCOs are passaged into a new Matrigel® bubble and grown for an additional 14 days. HCOs are collected on Day 35 at which organoids express colonic markers and contain major colon-specific cell populations (Fig. 6).

FIG. 1.

Overview of the protocol for generating colonic organoids (HCOs) in vitro. The general timeline of HCO generation. Specific media for each step, are indicated; recommended timepoints for samples collection are also depicted by green (organoids) and red (RNA) squares.

FIG. 2.

Definitive endoderm (DE) monolayer generation from hPSCs. hPSCs morphology before (A and B) and after Activin A Day 1 (C) after Activin A Day 2 (D) and after Activin A Day 3 (E). Scale bar = 100μm.

FIG. 3.

Mid-hindgut spheroids generation from the definitive endoderm. DE monolayer morphology 24h after adding mid-hindgut induction (MHGI) medium Day 1 (A) MHGI medium Day 2 (B) MHGI medium Day 3 (C) and MHGI medium Day 4 (D). Yellow arrows indicate tubular structures and white arrows indicates mid-hindgut spheroids. Scale bar = 100μm.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of human intestinal and colonic organoids by immunostaining. (A and B) Immunofluorescence of intestinal epithelial marker CDX2 (red), epithelial marker CDH1 (green) and DAPI (blue) of 35-days old organoids that resulted from a 3-days treatment of gut tube spheroids with NOGGIN (NOG HIOs) or BMP2 (HCOs). (C and D) Immunostaining of colonic marker SATB2 (red), CDH1 (green) and DAPI (blue) of NOG HIOs and HCOs. (E and F) Immunofluorescence of goblet cells marker MUC2 (red) and DAPI (blue) of NOG HIOs and HCOs. The dotted lines in E and F denote the epithelium. Scale bar = 50μm.

The step-by-step procedure for HCO generation in vitro is described below.

4. Step-by-step protocol

The steps to generate human colonic organoids (HCOs) from hPSCs are shown in Fig. 1.

4.1. Matrigel® coating of culture plates

hPSCs are maintained using feeder free culture, which requires the use 6-well Nunclon™ plates that are coated with Matrigel® and growth in mTeSR1 media.

4.1.1. Materials

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 6-wells (Nunc) (Thermo Scientific 73520–906)

Matrigel® hESC-qualified Matrix (Corning 354277): Prepare 4 × Matrigel® aliquots which correspond to volumes sufficient to make enough diluted Matrigel® for 4 × 6-well dishes. Because each lot of Matrigel® differs in protein concentration, the exact volume of Matrigel® in each aliquot size will differ from one lot to another; therefore check the certificate of analysis (CoA) from the manufacturer’s website for each batch of hESC-qualified Matrigel® to find the “dilution factor,” which determines the volume necessary to make enough diluted Matrigel® for the desired number of 6-well or 24-well plates. For example, a volume of 275μL for 4 × Matrigel® aliquot on the CoA means that a 275μL aliquot of Matrigel® is required to make diluted Matrigel® enough for 4 × 6-well plates. To aliquot the Matrigel®, take one bottle out of −20°C freezer and place it on ice at 4°C overnight to thaw. Once thawed, swirl the vial to ensure even mixing. Spray top of vial with 70% ethanol to sterilize prior to opening and place in the hood to air dry. Quickly dispense cold Matrigel® into appropriate sized aliquots (i.e., 275μL), using pre-cooled tubes and immediately re-freeze at −80°C

Gibco advanced DMEM (Gibco 12-491-023)

50-mL Corning tube (Falcon 21008–951)

4.1.2. Methods

Dispense 25-mL of cold DMEM medium into a 50-mL Falcon tube. This is sufficient to coat 4 × 6-well plates with 1mL per well, with a small amount of excess volume to compensate for pipetting error.

Remove aliquot of Matrigel® from −80°C freezer, spray it with 70% ethanol, then wipe dry with a Kimwipe. This step should be done quickly.

Take 750μL of cold DMEM from the 50-mL Falcon tube, add it to the tube of Matrigel® and pipette up and down to thaw and mix the Matrigel®.

Transfer this mixture back to 50-mL Falcon tube and mix well.

Add 1-mL per well into each of 4 × 6-well Nunclon™ delta surface plates.

Swirl the plates 2–3 times clockwise and counterclockwise to spread the Matrigel® evenly and ensure coating of the entire surface.

Seal coated plates with parafilm and leave at room temperature for at least 1h.

Coated plates can be store at 4°C for 7–10 days.

Before using stored plates, place inside the hood for half an hour at room temperature.

Note: Single cell plating (Section 4.3) is performed in 24-well plates and hence Matrigel® coating is also required for these plates. To do so, follow the same steps listed above for coating 6-well plates, however dilute one 4× vial of Matrigel® hESC-qualified Matrix in 50-mL of cold DMEM. After mixing, dispense 0.5-mL per well into 4 × 24-well Nunclon™ delta surface plates, and process plates as described in Section 4.1.2 (steps 6–9).

4.2. Maintenance of hPSCs

A prerequisite for generating mid-hindgut spheroids is maintaining hPSCs in optimal conditions with respect to differentiation and passaging interval. The following protocol describes the detailed procedures for maintaining undifferentiated stem cells.

4.2.1. Materials

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs 72.3, generated by the Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center). Note: Other hESC or iPSC lines can be used, but the protocol needs to be optimized for each cell line.

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 6-wells coated with Matrigel® (Section 4.1).

Fisherbrand™ Cell Lifter (Fisher 08-100-240).

Fisherbrand™ Disposable Borosilicate Glass Pasteur Pipette (13-678-2D0).

MilliporeSigma™ Steriflip™ Sterile Disposable Vacuum Filter Units (MilliporeSigma™ SCGP00525).

mTeSR1 complete growth medium: Add 100 mL of mTeSR supplement (Stem Cell technologies 85870) into one 400-mL mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell technologies 85870) and aliquot into 50-mL tubes to avoid contamination. Store at 4°C until use.

Dispase (Gibco 17105041): Resuspend lyophilized powder in DMEM-F12 (Gibco MT15090CV) to a 1mg/mL final concentration. Filter the solution for sterilization by vacuuming using a Millipore filter sterilization tube. Make 10-mL aliquots (1mg/mL) and store at −20°C for up to 6 months. Place at 4°C overnight before use.

Gibco advanced DMEM (Gibco 12-491-023).

4.2.2. Methods

Place one Matrigel® coated 6-well plate inside of a tissue culture hood for 30min.

Meanwhile, prewarm mTeSR1, dispase and advanced DMEM in a 37°C bath.

Check cell the density of the hPSCs. hPSCs are passaged once every 4 days when they are 70–80% confluent routinely split at a ratio of 1:6 to 1:8.

Manually remove any areas of differentiation from the plate.

For passaging, start by aspirating the old medium from the culture and wash once with 2-mL per well of advanced DMEM.

Aspirate the DMEM and add 1-mL per well of dispase solution.

-

Place cells in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C until the colony edges begin to lift slightly but the majority of the colony still remains attached to the plate. Colony edges routinely start to lift within 4–5min.

Note: Depending on the hPSC cell line and lot number of dispase, the time required for edges to fold may vary. Don’t scrape cells before edges have started lifting as this will result in poor survival.

During dispase incubation, aspirate the Matrigel® out of the 6-well plate that will be used to split cells and add 1.5-mL of pre-warmed mTeSR1 per well.

Aspirate dispase gently and wash each well three times with 2-mL advanced DMEM. During washing, dispense the medium onto the edge of the well to avoid dislodging of the colonies.

After the third wash, aspirate DMEM and add the appropriate volume of pre-warmed mTeSR1 per well (for example, add 3.5-mL per dish 6 well dish (~0.5mL per well) for a 1:6 passage and 4.5-mL for a 1:8 split).

Using a sterile cell lifter detach the colonies from the plate.

Triturate colonies by carefully pipetting up and down 2 or 3 times against the bottom of the plate to help break up the colonies.

Check under a microscope, if large clumps are visible after the first round of trituration, triturate more and keep checking clump size after each trituration.

Gently, dispense 0.5-mL of clump suspension per well in of the new Matrigel® coated plate.

Transfer the plate to the incubator and rock three times clockwise, three times counterclockwise, three times back and forth, and three times side to side to evenly distribute the clumps across the wells.

Perform daily medium changes and observe for colony growth.

4.3. Single cell plating of hPSCs for definitive endoderm (DE) differentiation

4.3.1. Materials

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs 72.3, generated by the Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center)

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 24-wells coated with Matrigel® (see Section 4.1)

mTeSR1 complete growth medium (Stem Cell technologies 85870)

Accutase (Thermo Scientific A1110501): Aliquot into 10-mL tubes and store at −20°C for up to 6 months. Place at 4°C overnight before use

ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Tocris 1254): Resuspend in DMSO at 10mM and filter sterilize. Make aliquots and store at −20°C

Gibco advanced DMEM (Gibco 12-491-023)

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 24-wells (Nunc) (Thermo Scientific 73521–004)

Hemocytometer (Sigma-Aldrich Z359629)

50-mL Corning tube (Falcon 21008–951)

15-mL Corning tube (Falcon 21008–918)

4.3.2. Methods

Place one Matrigel® coated 24-well plate inside the tissue culture hood for 30min.

Meanwhile, prewarm mTeSR1, accutase and advanced DMEM in a 37°C bath.

Check cell density (>85% confluency is optimal) and remove any areas of differentiation before starting.

In one 50-mL Falcon tube, dispense 13-mL of mTeSR and add 13μL of 1mM Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor (final concentration = 10μM). Addition of ROCK inhibitor is required to enhance cell survival by preventing anoikis.

Aspirate the culture media from 3 to 4 wells of hPSCs grown in 6-well plate and wash each well once with 2-mL advanced DMEM.

Aspirate the DMEM, add 1-mL of accutase per well and place the plate 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 5–7min. Microscopically inspect the plate to ensure that cells have detached.

Gently pipette the cell suspension 2–3 times with a serological pipette to ensure any remaining clumps are fully dissociated and to dislodge any cells that are still attached to the surface of the plate.

Add 2-mL of advanced DMEM per well and pipette up and down 2–3 times.

Transfer the cells to a 15-mL conical tube and centrifuge at 300 × g for 3min at room temperature.

Aspirate the supernatant and gently resuspend the pellet in 6-mL of mTeSR/ROCK inhibitor, from step 4 (take 6-mL of mTeSR/Y-27632 out of 13-mL which is in 50-mL conical tube).

Transfer the cell suspension back to the 50-mL conical tube (from step 4) and mix well by pipetting up and down. Total volume in the tube should be ~13mL.

Perform cell counting using a hemacytometer.

Aspirate Matrigel® from one coated 24-well plate.

Mix cell suspension and plate 100,000–200,000 cells per well into the 24-well plate (0.5-mL/well of suspension). We recommend optimizing the cell number by testing different densities (from 50,000 to 300,000 cells per well) for each hPSC line.

Rock the plate three times clockwise, three times counterclockwise, three times back and forth, and three times side to side.

Incubate the plate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24h.

Next day replace the medium with fresh mTeSR and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for another 24h.

Proceed to the next step (Section 4.4).

4.4. Differentiation of hPSCs into definitive endoderm (DE)

4.4.1. Materials

hPSC cells seeded in a Matrigel® coated 24-well plate (Section 4.3).

Activin A (Cell guidance Systems GFH6–100×10): Reconstitute the lyophilized powder at 100μg/mL in sterile PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Aliquot into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes and store at −80°C.

Recombinant Human BMP-4 Protein (R&D 314-BP-010): Reconstitute the lyophilized powder at 100μg/mL in sterile 4mM HCl containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Aliquot into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes and store at −80°C.

Activin Day 1 medium: RPMI 1640 (Corning MT10041CV), nonessential amino acids (Corning 11140050). Store at 4°C. To make Activin Day 1 medium add Activin A and BMP4 to a final concentration of 100ng/mL Activin A and 15ng/mL of BMP4.

Activin Day 2 medium: RPMI 1640, 0.2% FBS vol/vol (Hyclone SH30070.03T), nonessential amino acids. Store at 4°C. To make Activin Day 2 medium add Activin A to a final concentration of 100ng/mL.

Activin Day 3 medium: RPMI 1640, 2% FBS vol/vol, nonessential amino acids. Store at 4°C. To make Activin Day 3 medium add Activin A to a final concentration of 100ng/mL.

4.4.2. Methods

Prepare 13-mL of Activin Day 1 medium: 13-mL of basic Activin Day 1 medium, 13μL of 100μg/mL Activin A and 1.95μL of 100μg/mL BMP4. If possible, make media fresh each day. Warm media for the particular day in a 37°C water bath.

Aspirate the culture medium from each well of the 24-well plate.

Add 0.5-mL per well of Activin Day 1 medium.

Place the plate in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 24h.

On the next day, cell death should be evident (Fig. 2). This is expected due to the absence of serum in the culture medium.

The monolayer will appear sparse, but colonies of cells will have expanded.

Prepare 12.5-mL of Activin Day 2 medium: 12.5-mL of basic Activin Day 2 medium and 12.5μL of 100μg/mL Activin A. Warm in 37°C water bath before use.

Aspirate Activin Day 1 medium and add 0.5-mL per well of Activin Day 2 medium.

24h later, cells will form a monolayer and reach 90–95% confluency. You will still observe some cell death at this point.

Prepare 12.5-mL of Activin Day 3 medium: 12.5-mL of basic Activin Day 3 medium and 12.5μL of 100μg/mL Activin A. Warm in 37°C water bath.

Aspirate Activin Day 2 media and add 0.5-mL per well of Activin Day 3 medium.

After 24h, minimal cell death should be observed while the monolayer should be completely confluent. The morphology of the DE monolayer which is required for mid-hindgut spheroids generation is depicted in Fig. 2E.

Note: If the DE monolayer is not confluent 24h after adding Activin Day 3, discard and redo the experiment; don’t proceed to mid-hindgut differentiation.

4.5. Differentiation of DE into mid-hindgut spheroids

4.5.1. Materials

DE monolayer generated in prior steps (Section 4.4)

Recombinant Human FGF-4 Protein (R&D systems 235-F4–01M): Reconstitute at 100μg/mL in sterile PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Aliquot into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes and store at −80°C.

CHIR99021 (Reprocell 04000410): Reconstitute in DMSO at 10mM, make 50μL aliquots, protect from light and store at −20°C.

Mid-hindgut induction medium: RPMI 1640 (Corning MT10041CV), nonessential amino acids (Corning 11140050), 2% FBS vol/vol (Hyclone SH30070.03T), 3μM CHIR99021 and 500ng/mL FGF4.

4.5.2. Methods

Prepare 25-mL of mid-hindgut induction medium without CHIR99021 and warm in a 37°C water bath. This volume should be enough to feed 1 × 24-well plate for 2 days.

Once the medium is warm, add 7.5μL of 10mM CHIR99021 (final concentration = 3μM) into the 25-mL medium and mix well. Protect from light.

Aspirate Activin Day 3 medium and add 0.5-mL per well of mid-hindgut induction medium and place the plate in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator.

After 24h, tubular structures will start appearing in the monolayer (Fig. 3A); discard old medium, add fresh mid-hindgut induction medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

24h later, discard the old medium and add fresh medium then incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

After 3 days of mid-hindgut induction, spheroids will begin to detach from the monolayer and float in the culture medium (Fig. 3C). At this stage, floating spheroids should be collected and replated. To do so, collect the medium from each well containing floating spheroids into a 15-mL conical tube and spin down at 300 × g for 1min at room temperature. Add fresh mid-hindgut induction medium into the tube, resuspend the floating spheroids and dispense 0.5-mL of medium containing spheroids per well in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 24h.

After 4 days of mid-hindgut induction, floating spheroids are collected and plated in a Matrigel® droplet to generate organoids (Section 4.6).

4.6. Generation of HCOs from mid-hindgut spheroids

4.6.1. Materials

Mid-hindgut spheroids (Section 4.5).

Matrigel® Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning 354234).

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 24-wells (Nunc) (Thermo Scientific 73521–004).

15-mL Corning tube (Falcon 21008–918).

Basic gut medium: Advanced DMEM (Gibco 12491015), B27 (Gibco), N2 (Gibco 17-502-048), 15mM HEPES (15630080), 2mM l-glutamine (Corning A2916801), 100U/mL Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco 15-140-122).

NOG HIO patterning medium: Basic gut medium, 100ng/mL EGF and 100ng/mL NOGGIN.

CTRL HIO patterning medium: Basic gut medium and 100ng/mL EGF.

HCOs patterning medium: Basic gut medium, 100ng/mL EGF and 100ng/mL BMP2.

Outgrowth medium for HIOs, CTRL HIOs and HCOs: Basic gut medium and 100ng/mL EGF (Final concentration).

4.6.2. Methods

Thaw the Matrigel® Basement Membrane Matrix at 4°C overnight and aliquot the appropriate volume into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes on ice. For example, 750μL of Matrigel® is required for plating 12 wells of spheroids, to ensure that the Matrigel® concentration is at least 75% in the droplet in which the organoids will be embedded (see Table 1):

Place the Matrigel aliquots on ice inside the hood.

Warm a Nunclon™ 24-well plate in a 37°C incubator.

Prepare a few 200μL pipette tips by cutting their ends.

Using 1-mL pipette, transfer the floating spheroids from all wells into a 15-mL conical tube and spin down at 300 × g for 1min at room temperature.

Aspirate the medium and leave the volume required for plating: For 12 wells, its 240μL (Table 1).

Cut the tip off a p1000 pipette tip and transfer the spheroids into the Matrigel tube placed on ice.

Readjust pipettor to 700 μL and resuspend the spheroids and Matrigel® by pipetting up and down 3–5 times.

Using a cut 200μL pipette tip, add 60–65μL of the spheroids and Matrigel® mixture into the center of each well of the 24-well plate to create a Matrigel® droplet. When dispensing the spheroids, touch the bottom of the well with the tip and gently lift up while the mixture is being dispensed.

Gently transfer the plate into a 37°C incubator and incubate for 5min.

Flip the plate upside down and incubate for an additional 20min. This helps the Matrigel® droplet maintain a dome like structure.

Once the Matrigel® is solidified, add 0.5-mL of HCOs patterning medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 3 days. For troubleshooting purposes, we recommend also doing 6 wells of NOG HIO and 6 wells of control HIO medium.

After 72h, aspirate the patterning medium and add 0.5-mL of HCOs growth medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Change medium every 2–3 days until Day 21.

Table 1.

Volume of Matrigel®/Spheroids required for plating.

| Matrigel (μL) | Spheroid suspension (μL) | |

|---|---|---|

| 12-Wells | 750 | 240 |

| 6-Wells | 375 | 120 |

4.7. Splitting of HCOs on Day 21

4.7.1. Materials

Fisherbrand™ 6-cm Petri Dishes with Clear Lid (Fisher FB0875713A).

21-Days old HCOs (Section 4.6).

Matrigel® Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning 354234).

Nunclon™ delta surface tissue culture dish 24-wells (Nunc) (Thermo Scientific 73521–004).

Outgrowth medium for HIOs, CTRL HIOs and HCOs: Basic gut medium and 100ng/mL EGF.

4.7.2. Methods

Due to organoid growth and expansion, Matrigel® is almost entirely degraded by Day 21. Passaging is required at this stage to ensure a proper 3D growth until Day 35 when HCOs are collected.

Start by cutting the tip off a 1-mL pipette tip to enable HCOs to pass through the tip without any damage. Also, cut the tip off a few 200μL pipette tips.

Warm a 24-well plate in a 37°C incubator.

Using the pipette tip gently scrape the Matrigel® droplet with the organoids in each well.

Pipette the Matrigel®-organoids mixture up and down a few times to break up the Matrigel®.

Transfer the mixture into a 6-cm dish containing 2–3mL of advanced DMEM and if necessary, separate the organoids from each other using sterile forceps. Be cautious not to damage the epithelium of the organoids while splitting them.

Using a 200μL pipette with a cut tip, collect the dissociated HCOs into a 1.5-mL tube. Aim to transfer the organoids in the smallest volume if possible.

Adjust the volume of the organoids based on number of wells required (see Table 1).

Using a cut P1000 pipette tip transfer the organoids into a 1.5-mL tube filled with the Matrigel®.

Mix by pipetting up and down while avoiding any bubbles.

Cut the tip off a 200μL pipette tip and plate 60–65μL of organoid-Matrigel® mixture into each well of the 24-wells plate to create a Matrigel® droplet with 5–10 organoids per well. It is very critical during the pipetting to suck up the organoids first then the Matrigel® so while dispensing the mixture, the organoids are at the top of the Matrigel® droplet.

Incubate the plate at 37°C for 5min.

Flip the plate upside down and incubate for 20min.

Add 0.5-mL of HCOs outgrowth medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Change the medium when it becomes yellow (usually every 2–3 days) until Day 35.

4.8. Characterization of colonic organoids

In general, HCOs are collected on Day 35 for qPCR and immunofluorescence (IF).

4.8.1. Real-time PCR

4.8.1.1. Materials

NucleoSpin® RNA (Takara 740955.250). Note: other RNA isolation kits may be used.

SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo 11-754-250).

Primers from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (IDT) are listed in Table 2.

Biorad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System. Note: other qRT-PCR systems can be used.

Table 2.

Primer list.

| Gene | Primers |

|---|---|

| PPIA (CphA) |

Forward: CCCACCGTGTTCTTCGACATT Reverse: GGACCCGTATGCTTTAGGATGA |

| HOXD3 |

Forward: CACCTCCAATGTCTGCTGAA Reverse: CAAAATTCAAGAAAACACACACA |

| HOXA13 |

Forward: GCACCTTGGTATAAGGCACG Reverse: CCTCTGGAAGTCCACTCTGC |

| HOXD13 |

Forward: CCTCTTCGGTAGACGCACAT Reverse: CAGGTGTACTGCACCAAGGA |

| MSX2 |

Forward: GGTCTTGTGTTTCCTCAGGG Reverse: AAATTCAGAAGATGGAGCGG |

4.8.1.2. Methods

Note: Steps 1, 4, 6 and 7 below describe our standard methods. Alternative RNA isolation kits, reversed transcription kits and qRT-PCR machines can be used, but will need to be optimized.

Prepare the RNA lysis buffer as instructed in the manufacturer’s protocol.

Aspirate the media from each well of a 24-well plate containing Matrigel® coated organoids.

Add 350μL of lysis buffer per 2 wells of the 24-well plate.

Using a 1-mL pipette break down the Matrigel® and pipette up and down to resuspend the organoids. Vortex at full speed for 5 s to ensure complete suspension of organoids in lysis buffer. Store samples in lysis buffer at −80 °C until ready to isolate RNA.

Thaw samples in lysis buffer on ice for 10 min. Vortex at max speed for 10–15 min to completely lyse the organoids.

Isolate RNA according to manufacturers protocol and store RNA samples at −80°C until ready to perform next step.

Reverse-transcribe 700–1000ng of RNA into cDNA using the SuperScript kit as instructed by the manufacturer. Dilute your cDNA 1:100 before starting your qPCR.

Using the primers listed in Table 2, perform qPCR on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR machine as described by the manufacturer.

Calculate the ddCT for each gene in each sample and perform a Student’s t-test for find significant differences between groups.

4.8.1.3. qPCR anticipated results

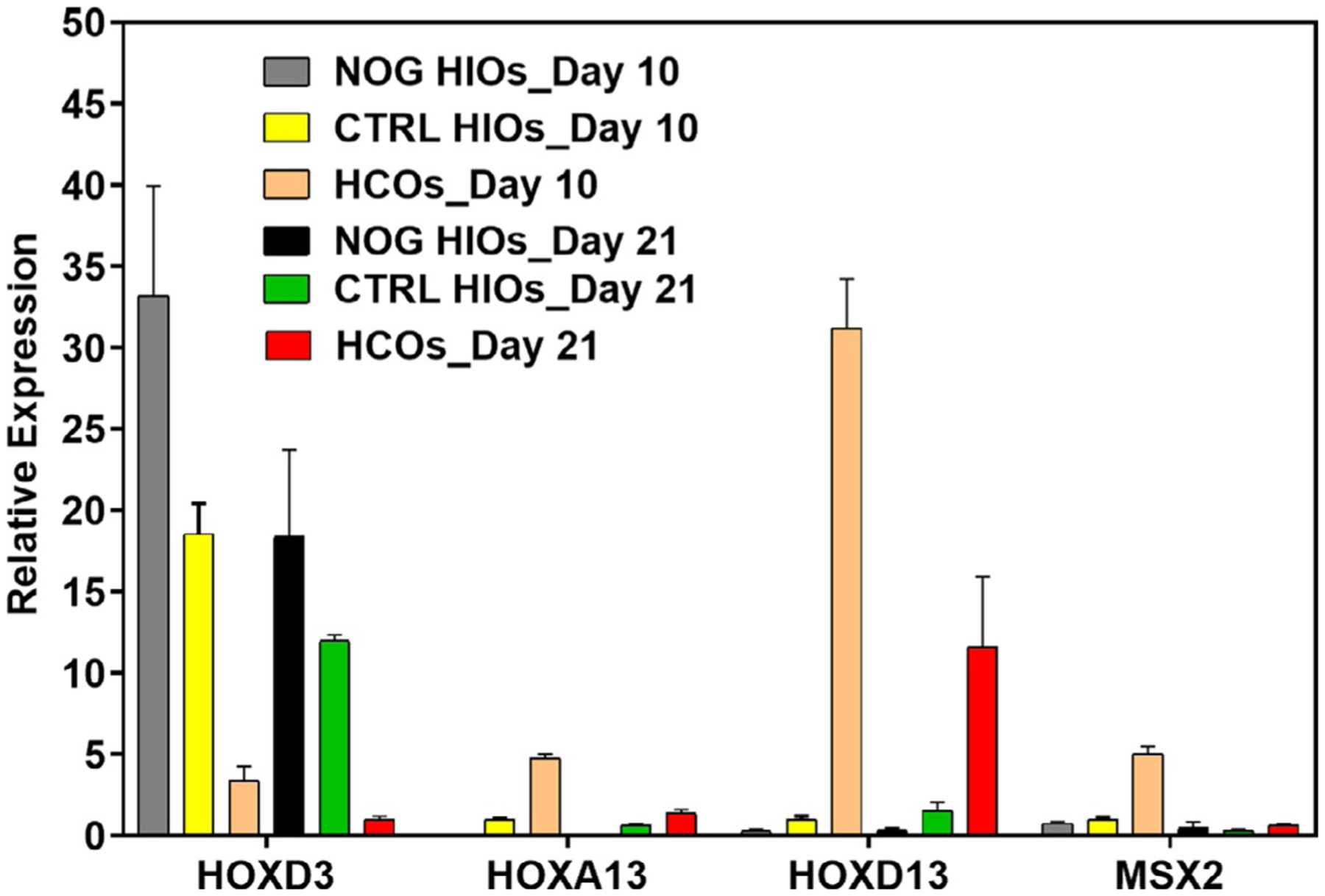

A significant increase of HOXA13, HOXD13 and MSX2 in HCOs (BMP2 treated) should be observed relative to Noggin treated HIOs (NOG HIOs) and CTRL organoids on Day 10 and Day 21 (Fig. 4 shows relative expression of HOX genes and MSX2 in organoids from Day 10and Day 21compared to control organoids fromDay 10). In contrast, HOXD3, a BMP2-repressed gene should be significantly lower in HCOs compared to NOG HIOs (Fig. 4).MSX2, a direct SMAD target, is increased upon BMP2 activation and is significantly higher in HCOs on Day 10 but goes down later on (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Gene expression of HOX genes and MSX2 in human colonic and intestinal organoids. RNA is isolated from Noggin HIOs (NOG HIOs), CTRL organoids and HCOs on Day 10 and 21. qRT-PCR was performed as previously described in methods and relative expression of HOX genes and MSX2 was calculated for each group compared to control organoids of Day 10.

4.8.2. Organoid fixation

4.8.2.1. Materials

Ice-cold Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) pH 7.4

Cell Recovery Solution (Corning 354253)

Ice-cold 4% Paraformaldehyde solution (PFA)

4.8.2.2. Methods

Aspirate the media from each well of the 24-well plate and add 0.5-mL of ice-cold PBS.

Cut the tip off a 1-mL pipette tip and dissociate organoids from the Matrigel® by pipetting up and down.

Transfer the organoids into a 15-mL conical tube.

Steps 4–8 are designed to remove Matrigel® prior to organoid fixation. Fill the tube with ice-cold PBS up to 14-mL and mix gently by inverting five times.

Allow the organoids to settle by gravity which may take 2–3min.

Aspirate the PBS and add 1-mL of ice-cold cell recovery solution.

Place the tube on ice for 10–15min on a rotating platform with gentle shaking.

Organoids should sink to the bottom indicating a complete digestion of the Matrigel®.

Fill the tube with ice-cold PBS up to 15-mL.

Aspirate the PBS, add 1-mL of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde and fix the organoids on ice for 30–60min.

Fill the tube with ice-cold PBS up to 14-mL and place horizontally on a rocking platform at 4°C overnight.

The next day, properly dispose of the paraformaldehyde/PBS solution and wash once with 15-mL of ice-cold PBS.

Store the sample in ice-cold PBS and place at 4°C. Organoids can be stored like this for up to 1 month.

4.8.3. Whole mount immunostaining

4.8.3.1. Materials

1% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution

Phosphate Buffered Saline – —0.5% Triton X (PBS-T)

5% Normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab 017-000-121)

Murray’s Clear solution (also known as BABB): 1:2 benzyl benzoate and benzyl alcohol

Fisherbrand™ Class B Clear Glass Threaded Vials with Closures Attached (Fisher 03–338B)

μ-Slide 2 well (Ibidi 80286)

4.8.3.2. Methods

Fill a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube with 1% BSA and place on gyrating platform for 1 h. This step is important to prevent organoids from sticking to the wall of the tube.

Transfer 3–5 organoids that were stored in PBS into the pre-coated tube and add 1-mL of PBS-T.

Place the tube on a rocking platform overnight at 4°C to permeabilize the organoids.

Block organoids with 5% donkey serum made in PBS-T for 6–8h at room temperature.

Aspirate the blocking solution. Be cautious not to aspirate the organoids.

Incubate the organoids with the primary antibody upright in a tube rack overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. Use 250μL of antibody solution per 100μL of organoids (up to 5 organoids). Do not place tubes horizontally or they will dry out.

Wash three times with PBS-T for 20–60min on a gyrating platform at room temperature.

Incubate the organoids with the secondary antibody overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform.

Wash two times with PBS-T for 20min on a gyrating platform at room temperature.

Wash once with PBS for 20min on a gyrating platform at room temperature.

-

Wash three times with 100% methanol for 20min on a gyrating platform at room temperature.

Note: At this step, organoids can be stored in methanol at 4°C for a month.

-

Place the organoids in a glass vial tube, add 2-mL of fill with Murray’s Clear and allow clearing for at least 1h in the dark.

Note: You can also incubate the sample in Murray’s Clear solution at room temperature overnight in the dark.

Note: Other clearing methods may be used, but we routinely use Murray’s Clear. Optimization of other methods will be required.

Transfer the organoids into an Ibidi imaging chamber and add Murray’s Clear until organoids are submerged.

-

Image the organoids on a confocal microscope.

Note: Because in whole mount protocol the entire organoid is stained, some antibodies and DAPI may not penetrate the organoids entirely, hence optimization of the protocol may be necessary.

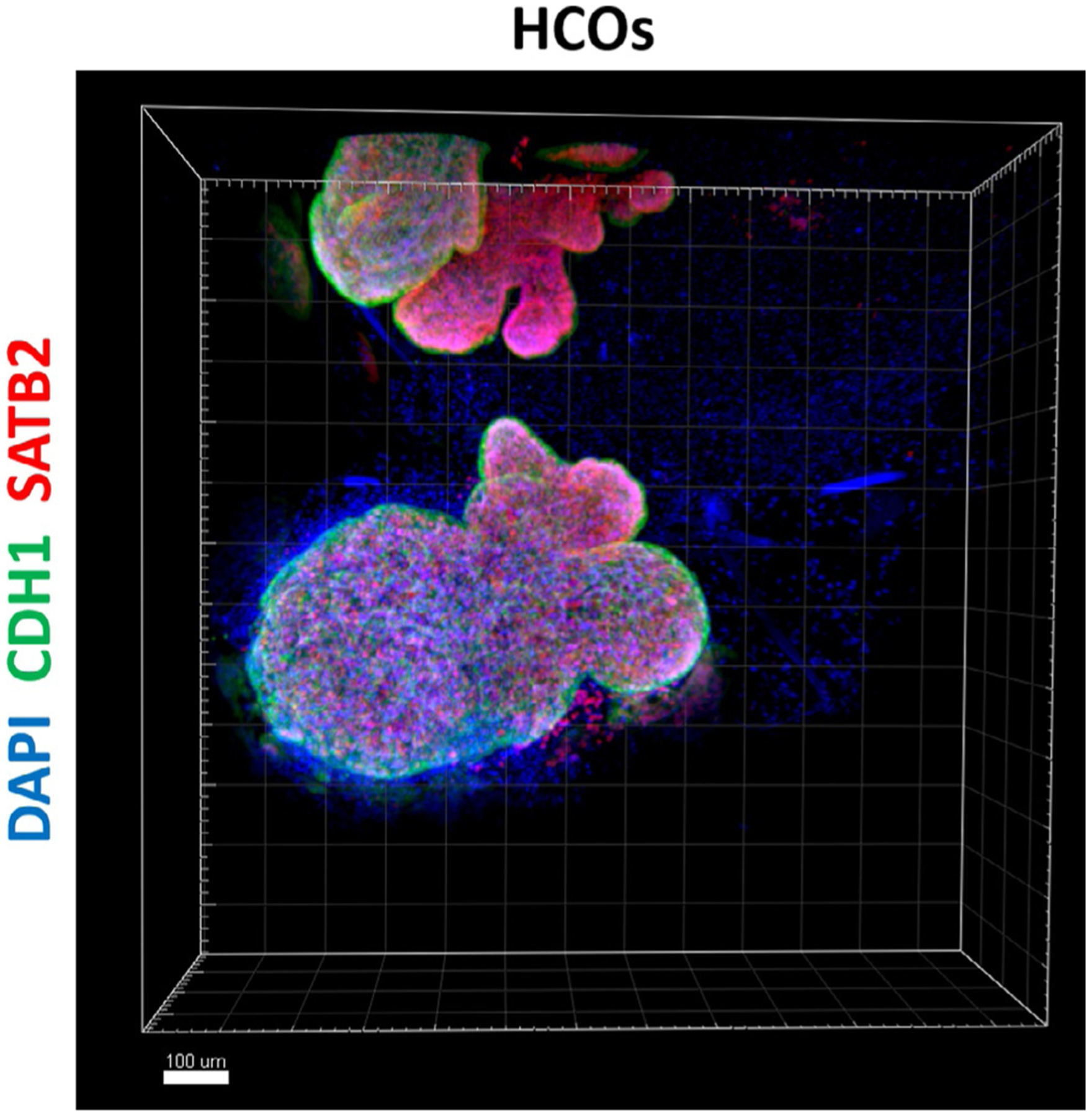

4.8.3.3. Whole mount anticipated results

For imaging, we recommend performing a z-stack of the entire organoid with a 10× objective. Some organoids are 600–1000μm in diameter, so it is important to verify whether the microscope you intend to use has the capability to image such thick structures. By using a marker that stains the epithelium such as E-cadherin (CDH1), the whole mount image will show the budding morphology of HCOs (Fig. 5). Whole mount or thin section staining (see Section 4.8.4) should demonstrate that SATB2 is highly expressed in HCOs on Day 35 and absent in NOG HIOs and CTRL HIOs (Fig. 6C and D). The goblet cell marker MUC2 should also be abundant in HCOs, but expressed only in rare cells within NOG and CTRL HIOs (Fig. 6E and F). CDH17 should be expressed in NOG HIOs, CTRL HIOs and HCOs. The proximal intestinal markers ONECUT1 and PDX1 are not expressed in HCOs but highly abundant in NOG HIOs (Munera et al., 2017).

FIG. 5.

Whole mount immunostaining of human colonic organoid. Whole mount immunostaining of colonic marker SATB2 (red), CDH1 (green) and DAPI (blue) of 35-days old organoids that resulted from a 3-day treatment of gut tube spheroids with BMP2 (HCOs). Scale bar = 100μm.

4.8.4. Immunostaining of tissue sections

4.8.4.1. Materials

30% Sucrose made in PBS

Base mold (Fisher 22-363-552)

Phosphate Buffered Saline —0.5% Triton X (PBS-T)

5% Normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab 017-000-121)

Tissue-Tek* O.C.T. Compound (VWR 25608–930)

Leica microtome

ImmEdge™ Hydrophobic Barrier Pen (Vector Laboratories 101098–065)

Fluoromount-G® Slide Mounting Medium (VWR 100241–874)

DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich D9542) (Table 3)

Table 3.

Primary and secondary antibodies list.

| Antibody | Source | Catalog number | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit anti-CDX2 | Cell Marque | EPR2764Y | 1:100 |

| Mouse anti-CDX2 | BioGenex | MU392-UC | 1:300 |

| Rabbit anti-SATB2 | Cell Marque | EP281 | 1:100 |

| Goat anti-E-Cadherin | R&D systems | AF648 | 1:400 |

| Rabbit anti-MUC2 (replaced sc 15334 from Santa Cruz) | Cloud Clone | PAA705Hu01 | 1:100 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Donkey anti-Mouse | Thermo | A31571 | 1:500 |

| Alexa Fluor 546 Donkey anti-Mouse | Thermo | A10036 | 1:500 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-Rabbit | Thermo | A21206 | 1:500 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-Goat | Thermo | A11055 | 1:500 |

4.8.4.2. Methods

Transfer 0.5-mL of organoids stored in PBS into a 15-mL tube and fill up with 30% sucrose. Make sure the organoids are not attached to the wall or the cap of the tube.

Place the tube on a rocking platform overnight at 4°C. Organoids will initially float in 30% sucrose, but will sink as they equilibrate.

Transfer the organoids into the base mold and aspirate the sucrose.

Add the O.C.T to the mold while avoiding bubbles.

Leave the block at room temp for 30min to 1h.

Flash freeze the block in an ethanol-dry ice bath for 10min. Take care not to get ethanol on the top of the mold or on the O.C.T.

-

Store the organoids at −80°C overnight, then proceed to sectioning on a Leica cryotome.

Note: Blocks of organoids can be stored at −80 °C for months before sectioning. Store sections at −80°C in a slide box until beginning the immunostaining protocol (step 8).

Wash the slides in a Coplin jar filled with PBS-T for 10–15min, then once with PBS for 3min.

Dry the slides with a Kimwipe avoiding the embedded tissue then use the vacuum to aspirate the buffer around the tissue.

Circle the area around tissue with the ImmEdge pen and let it dry for about 10min.

Block the slides with 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) diluted in PBS-T at room temperature for 30min.

Aspirate the NDS, add the primary antibodies and incubate at 4 °C overnight.

Tip off the primary antibodies and wash the slides three times with PBS-T, 5min each wash.

Add the secondary antibodies diluted in PBS-T plus 5% NDS plus DAPI, protect from light and incubate at room temperature for 1.5–2h.

Tip off the buffer and antibody mix and wash the slides twice with PBS-T and once with PBS for 5min each.

Dry the slides with a Kimwipe avoiding the tissue, then use the vacuum to aspirate the buffer around the tissue. Leave some buffer on the tissue itself so that it doesn’t dry out.

Add Fluoromount-G and place a cover glass on top of the slide. Be cautious not to introduce bubbles.

Allow the slides to dry in dark at room temperature for at least 2h before imaging.

4.8.4.3. Anticipated results

See Section 4.8.3.3

5. Statistical analysis

For statistical purposes, generate at least three batches of organoids each from a different passage number of hPSCs.

For qPCR calculate the ddCT of each gene, use PPIA (CphA) as the housekeeping gene and take EGF treated group as the control.

Perform statistical analysis using Student’s t-test and calculate P values of each comparison.

6. Pros and cons

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| HCOs generated by this method contain both intestinal epithelium and mesenchyme | Time consuming in comparison to 2D culture models |

| Any personal with cell culture expertise can generate organoids | Occasionally, failure of spheroids generation |

| No special equipment is required, and all supplements and growth factors are available for purchase from common vendors | Variability of spheroids generation between different iPSCs lines (see Section 7) |

7. Troubleshooting and optimization

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor DE induction |

|

| Monolayer breaks down after adding hindgut induction medium |

|

| Low spheroid number |

|

| Organoids growing in 2D rather than 3D after splitting on Day 21 |

|

| Organoids grow in 3D but lack the expression of SATB2 on Day 35 |

|

8. Conclusion

Colonic organoids represent a promising platform for basic science as well as translational studies. The purpose of this chapter is to give the reader a precise, up-to-date method for successful HCOs generation in vitro. By following this procedure, someone with tissue culture knowledge will successfully generate organoids from hPSCs and will be able to characterize them using immunostaining and qPCR. The current protocol also addresses the main issues faced during each step of organoids generation with solutions to overcome these challenges.

References

- Bartfeld S, Bayram T, van de Wetering M, Huch M, Begthel H, Kujala P, et al. (2015). In vitro expansion of human gastric epithelial stem cells and their responses to bacterial infection. Gastroenterology, 148(1), 126–136.e126. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo M, Vilar E, Tsai SY, Chang K, Amin S, Srinivasan T, et al. (2017). Colonic organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for modeling colorectal cancer and drug testing. Nature Medicine, 23(7), 878–884. 10.1038/nm.4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amour KA, Agulnick AD, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Kroon E, & Baetge EE (2005). Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nature Biotechnology, 23(12), 1534–1541. 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BR, Hill DR, Ferguson MA, Tsai YH, Nagy MS, Dyal R, et al. (2015). In vitro generation of human pluripotent stem cell derived lung organoids. eLife, 4, e05098. 10.7554/eLife.05098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham RP, Yui S, Hannan NR, Soendergaard C, Madgwick A, Schweiger PJ, et al. (2013). Transplantation of expanded fetal intestinal progenitors contributes to colon regeneration after injury. Cell Stem Cell, 13(6), 734–744. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huch M, Gehart H, van Boxtel R, Hamer K, Blokzijl F, Verstegen MM, et al. (2015). Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell, 160(1–2), 299–312. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung P, Sato T, Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Iglesias M, Rossell D, et al. (2011). Isolation and in vitro expansion of human colonic stem cells. Nature Medicine, 17(10), 1225–1227. 10.1038/nm.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau ST, Li Z, Pui-Ling Lai F, Nga-Chu Lui K, Li P, Munera JO, et al. (2019). Activation of hedgehog signaling promotes development of mouse and human enteric neural crest cells, based on single-cell transcriptome analyses. Gastroenterology, 157(6), 1556–1571.e1555. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, & Izpisua Belmonte JC (2019). Organoids—Preclinical models of human disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 380(20), 1982. 10.1056/NEJMc1903253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken KW, Aihara E, Martin B, Crawford CM, Broda T, Treguier J, et al. (2017). Wnt/beta-catenin promotes gastric fundus specification in mice and humans. Nature, 541(7636), 182–187. 10.1038/nature21021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken KW, Cata EM, Crawford CM, Sinagoga KL, Schumacher M, Rockich BE, et al. (2014). Modelling human development and disease in pluripotent stem-cell-derived gastric organoids. Nature, 516(7531), 400–404. 10.1038/nature13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken KW, Howell JC, Wells JM, & Spence JR (2011). Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nature Protocols, 6(12), 1920–1928. 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munera JO, Sundaram N, Rankin SA, Hill D, Watson C, Mahe M, et al. (2017). Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into colonic organoids via transient activation of BMP signaling. Cell Stem Cell, 21(1), 51–64.e56. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JT, Li X, Zhu J, Giangarra V, Grzeskowiak CL, Ju J, et al. (2018). Organoid modeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Cell, 175(7), 1972–1988.e1916. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ootani A, Li X, Sangiorgi E, Ho QT, Ueno H, Toda S, et al. (2009). Sustained in vitro intestinal epithelial culture within a Wnt-dependent stem cell niche. Nature Medicine, 15(6), 701–706. 10.1038/nm.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, et al. (2012). Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 Update. Gastroenterology, 143(5), 1179–1187.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger GJ, Holbrook JD, & Andrews PL (2011). The translational value of rodent gastrointestinal functions: A cautionary tale. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 32(7), 402–409. 10.1016/j.tips.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, Van den Brink S, et al. (2011). Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology, 141(5), 1762–1772. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, et al. (2009). Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature, 459(7244), 262–265. 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinagoga KL, McCauley HA, Munera JO, Reynolds NA, Enriquez JR, Watson C, et al. (2018). Deriving functional human enteroendocrine cells from pluripotent stem cells. Development, 145(19), 1–11. 10.1242/dev.165795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, et al. (2011). Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature, 470(7332), 105–109. 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto S, Ohta Y, Fujii M, Matano M, Shimokawa M, Nanki K, et al. (2018). Re-construction of the human colon epithelium in vivo. Cell Stem Cell, 22(2), 171–176.e175. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trisno SL, Philo KED, McCracken KW, Cata EM, Ruiz-Torres S, Rankin SA, et al. (2018). Esophageal organoids from human pluripotent stem cells delineate Sox2 functions during esophageal specification. Cell Stem Cell, 23(4), 501–515.e507. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YH, Nattiv R, Dedhia PH, Nagy MS, Chin AM, Thomson M, et al. (2017). In vitro patterning of pluripotent stem cell-derived intestine recapitulates in vivo human development. Development, 144(6), 1045–1055. 10.1242/dev.138453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui S, Nakamura T, Sato T, Nemoto Y, Mizutani T, Zheng X, et al. (2012). Functional engraftment of colon epithelium expanded in vitro from a single adult Lgr5(+) stem cell. Nature Medicine, 18(4), 618–623. 10.1038/nm.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]