Abstract

Epidemiological studies inversely associate body mass index (BMI) with breast cancer risk in premenopausal women, but the pathophysiological linkage remains ill-defined. Despite the documented relevance of the ‘local’ environment to breast cancer progression and the well-accepted differences in transcriptome and metabolic properties of anatomically distinct fat depots, specific breast adipose contributions to the proliferative potential of non-diseased breast glandular compartment are not fully understood. To address early breast cancer causation in the context of obesity status, we compared the cellular and molecular phenotypes of breast adipose and matched breast glandular tissue from premenopausal non-obese (mean BMI = 27 kg/m2) and obese (mean BMI = 44 kg/m2) women. Breast adipose from obese women showed higher expression levels of adipogenic, pro-inflammatory and estrogen synthetic genes, than from non-obese women. Obese breast glandular tissue displayed lower proliferation and inflammatory status and higher expression of anti-proliferative/pro-senescence biomarkers TP53 and p21, than from non-obese women. Transcript levels for T-cell receptor and co-receptors CD3 and CD4 were higher in breast adipose of obese cohorts, coincident with elevated adipose Interleukin 10 (IL10) and FOXP3 gene expression. In human breast epithelial cell lines MCF10A and HMEC, recombinant human IL10 reduced cell viability and CCND1 transcript levels, increased those of TP53 and p21, and promoted (MCF10A) apoptosis. Our findings suggest that breast adipose-associated IL10 may mediate paracrine interactions between non-diseased breast adipose and breast glandular compartments and highlight how breast adipose may program the local inflammatory milieu, partly by recruiting FOXP3+ T regulatory cells, to influence premenopausal breast cancer risk.

Keywords: breast adiposity, premenopausal, immune cells, interleukin 10, obesity, breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a complex, heterogenous disease and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in developed countries [Kamangar et al. 2006, Heer et al. 2020]. Breast tumors display a high degree of intra- and inter-genotypic and phenotypic diversity, which reflects the many risk factors and multiple interacting mechanisms underlying disease incidence, progression and treatment response [Perou et al. 2006, Park et al. 2010, Polyak 2011]. To date, despite the sophisticated OMICS technologies that have allowed the molecular dissection of breast tumors at the single cell level, the translation of these advances to clinical practice remains a challenge due to limited mechanistic understanding of tumor evolution and risks.

Reproductive, behavioral and environmental factors are major contributors to breast cancer etiologies [Hiatt et al. 2020]. However, because their respective influences are dependent on particular life stages and duration of exposure, their causal relationships to disease risk are less clear. Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, is one risk factor in breast cancer that has gained significant attention due to the dramatic increase in its incidence in the general population [https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html] and its emerging links to inflammation that underlies many chronic and often deadly diseases [Picon-Ruiz et al. 2017]. Recent studies have indicated that there are critical windows of susceptibility in the life course when exposure to an obesogenic environment (i.e., obesity) has greater impact than at other life stages [Fenton et al. 2012, Burkholder et al. 2020]. This appears to be the case for the seemingly paradoxical relationship reported for premenopausal vs. postmenopausal obesity and risk for developing breast cancer. Specifically, while epidemiological studies associate obesity to higher postmenopausal breast cancer risk, analyses of large data sets found inverse correlations between premenopausal breast cancer risk and obesity, with some exceptions [Chen et al. 2017, Kabat et al. 2017, Schoemaker et al. 2018]. The mechanistic underpinnings of the connection between breast cancer incidence and premenopausal obesity remain unclear since there are many variables involved in the reported studies, including the contribution of BMI vs. adiposity as marker for body fat; age range (18–24 vs >25–50 years), breast cancer subtypes (estrogen receptor (ESR1)-positive vs ESR1 negative breast cancers) and ethnicity [Chollet-Hinton et al. 2017, Agurs-Collins et al. 2019, Noh et al. 2020]. Understanding the complex relationship between obesity and breast cancer risk by menopausal status has significant public health implications for prognosis and therapeutic management. While the global incidence and mortality of breast cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women show comparable rising trends [Heer et al. 2020], affected premenopausal women present with more aggressive and higher-grade tumors and show greater rates of recurrence and lower overall survival [Azim et al. 2012, Chollet-Hinton et al 2017].

Adipose tissue is an important regulator of systemic metabolism and is organized into different depots. There is currently limited knowledge on how breast adipose tissue influences subsequent risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women. Studies to delineate fat-breast epithelial signaling have predominantly used non-mammary adipose cells (Strong et al., 2013) or cancer-associated adipocytes [Dirat et al. 2011] and breast tumor cells of different etiologies [Himbert et al. 2017]. The human adult breast is comprised of basal and luminal epithelial cell types. The luminal cells are further segregated into two populations defined by their hormone-responsiveness namely, Estrogen Receptor (ESR)/Progesterone Receptor (PGR)-positive and ESR/PGR-negative cells [Peterson & Polyak 2010, Nguyen et al. 2018]. A substantial body of work supports the concept that the luminal lineages, upon acquisition of mutations, constitute the cells‐of‐origin for breast cancer subtypes [Visvader & Stingl 2014]. In a recent report, obesity type (visceral vs. subcutaneous) was found to differentially influence the risk for ESR/PGR-positive vs. ESR/PGR-negative breast cancers in women [Liu et al. 2017]. In particular, subcutaneous obesity showed a strong association with ESR/PGR-positive tumor subtype, especially among premenopausal women, whereas visceral obesity was more specific for ESR/PGR-negative tumor subtype, independent of menopausal status [Liu et al 2017]. While these findings are consistent with accumulating evidence that fat depots [Hill et al 2018], and even adipocytes within a single depot [Lee et al. 2019], exhibit significant heterogeneity and vary in their inflammatory, paracrine and metabolic activities, the underlying mechanisms regulating breast adipose interaction with breast glandular tissue in the context of obesity are unclear.

In the present study, we used mammoplasties from reproductive-age women with no diagnosed breast or any cancers to investigate the relationship between breast adiposity and breast glandular tissue phenotype and genotype. We show that paracrine regulation by breast adipose tissues underpins the phenotypic and genotypic differences in premenopausal breast glandular tissue as a function of obesogenic status. We identify enhanced production of IL10 and increased recruitment of IL10-producing T regulatory cells by the obese adipose as potential mechanisms for influencing premenopausal breast cancer risk.

Methods

Subject recruitment

Premenopausal women undergoing breast reduction surgery at the Department of Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) were recruited for study participation during consultation visits with the collaborating surgeon (KGW). Eligibility criteria were: age between 21 and 50 years old (premenopausal), no previous diagnosis of breast or any other cancers, and BMI less than 30 Kg/m2 (non-obese, NO) and >30 Kg/m2 (obese, O). Risk-related information (parity, oral contraceptive use, smoking and alcohol consumption) were collected from clinical records for individual patients. Study procedures were under an approved UAMS Institutional Review Board protocol (UAMS IRB#206329). All participants provided written informed consent.

Sample collection and processing

Breast tissues collected at surgery were taken promptly to the cutting room of the Pathology Department, where a designated pathologist inspected and sampled the specimens for histology to confirm non-cancerous status. The rest of the breast tissue was transported to the laboratory in chilled Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline Solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 1% Antibiotic-antimycotic solution (ABAM; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A portion of the breast tissue (two sections per tissue sample) was fixed in buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 24 h, paraffin-embedded, and subsequently processed for immunohistochemistry (below). The remainder of the breast tissue was dissected to separate the adipose from the glandular tissue compartment. Tissue samples for RNA analyses were stored in RNAlater™ Solution (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), while the rest were frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 C until further use.

Tissue RNA isolation and analyses

Total RNA was isolated from adipose tissue using the RNeasy® Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen N.V., Hilden, Germany) and from glandular epithelial tissue using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was assessed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels. Intact RNAs were reverse-transcribed (iScript cDNA Synthesis kit, BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and used for SYBR green-based real-time quantitative PCR (iTaq SYBR Green Supermix, Bio-Rad), as previously described [Pabona et al. 2012]. Primer sequences (available upon request) were designed to span introns and were purchased from Integrated DNA Biotechnologies Inc. (Coralville, IA). Target mRNA levels were normalized to a factor calculated from the geometric mean of expression values for ribosomal protein L19 (RPL19) and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs [Pabona et al. 2012]. Gene expression analyses were performed twice on the same sample sets to confirm reproducibility of significant trends.

Adipocyte volume

Five-micron sections of paraffin-embedded breast tissues were stained with hematoxylin followed by eosin (H&E), and images were captured by using a digital pathology whole slide scanner (Aperio ImageScope; Leica Biosystems Nussloch GmbH, Ortenborg, Germany). Adipocyte areas (μm2) were determined by measuring the length and width of each cell from acquired images of 25 adjacent adipocytes per visual field. Four random areas were analyzed per tissue slide, with one tissue slide evaluated per patient. Adipocyte volume (μm3) was determined from calculated area x tissue thickness (5 μm). The mean adipocyte areas and adipocyte size distributions (<3000, 3000–6000, >6000 μm2) for 100 adipocytes per tissue sample were compared between NO and O cohorts, each representing 10 patients.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) prepared from O and NO breast tissues were processed and incubated with specific antibodies, following previously described protocols [Brown et al. 2018]. The antibodies [Research Resource Identifier (RRID), www.antibodyregistry.org] and their respective working dilutions used at incubation conditions of 4°C; 16 to 24 h are: rabbit anti-Ki67 monoclonal (RRID:AB_302459, 1:100); rabbit anti-human galectin-1 (GAL-1) (RRID:AB_2136615, 1:500); rabbit anti-human perilipin (RRID:AB_10829911, 1:400); rabbit anti-human TP53 (RRID:AB_331476, 1:200); rabbit anti-human β-galactosidase (β-GAL) (RRID:AB_221539, 1:400); and mouse anti-human p21 (RRID: AB_2077688, 1:200). Negative controls were sections processed in parallel, with omission of the primary antibody. Slides were imaged with EVOS® FL Auto Imaging System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For Ki67, TP53 and p21 antibodies, the numbers of nuclei-localized immunopositive glandular epithelial cells and the total numbers of cells counted (stained + unstained) were determined. Immunostaining intensities for β-GAL (within whole glands), GAL-1 (localized to glandular myoepithelia) and perilipin (localized to adipocyte cell surface) were quantified using the Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). For GAL-1, the staining intensity of the myoepithelial layer of each gland was determined from the intensity difference between the entire gland and the luminal epithelial layer alone. Data from analyses of Perilipin, Ki67, TP53, p21, GAL-1 and β-GAL immunostaining (n=10 tissue sections each for NO and O groups) represent 6 random glands located at two random visual fields per tissue section, with each section representing an individual patient.

Telomere length assay

Genomic DNA from breast glandular tissue of NO (n=5) and O (n=5) women was prepared using the QIAmp DNA Mini-Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Relative human telomere length quantification used the qPCR-based assay kit (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocols. Data normalization employed a 100 bp-long region on human chromosome 17, quantified by qPCR in the same sample sets, using the single copy reference primer set provided in the kit.

Cell culture and treatments, viability and apoptosis assays and RNA expression analyses

The human non-tumor breast epithelial cell lines MCF10A and HMEC (American Tissue Type Collection, Manassas, VA) were propagated and maintained in growth media (Human Mammary Epithelial Cell Growth Media; Cell Application Inc., San Diego, CA) at 37 C in a 5% CO2 incubator, as previously described [Su & Simmen 2009]. For cell viability assays, cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and were serum-starved for 18 h using diluted (20%) growth media prior to treatments. Recombinant human (rh) IL10 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was dissolved in PBS, further diluted in media and used at various concentrations (5, 10, 25 and 50 ng/ml) to determine the optimal treatment dose. Treatment with media alone served as control. Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 metabolic assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD). Absorbance at 450 nm was determined using a CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech GmbH) and the mean optical density from n=6 wells/treatment group was calculated. Apoptosis assay was carried out in control and rhIL10-treated (10 ng/ml) cells grown in 24-well plates, 72 h post-treatment using the TACS apoptosis detection kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Early (annexin V–positive/propidium iodide–negative) and late (positive for both annexin V and propidium iodide) stages were determined using the Attune NxT acoustic focusing cytometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For RNA isolation, cells were plated in 24-well plates and treated with rhIL10 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h prior to collection. Total RNA was isolated using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and processed for qPCR analyses as described above.

Statistical analyses

Data (Mean ± SEM) obtained from analyses of all measured parameters between O and NO groups were compared by Student t-test using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (Graphpad Software, CA). All outlier points were included in the analyses. For in vitro (cell) studies, IL10 effects on cell viability, apoptosis and gene expression were compared to the control (PBS alone) group. In all figures, significant differences are indicated as*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.001 and #0.1<P< 0.05, relative to the NO (breast tissues) or vehicle control (cells) group.

RESULTS

Demographic information of patient cohorts

Twenty women (10 non-obese and 10 obese) were successfully recruited to the study. The mean age (years) for each group did not differ (NO, 36.1 ± 3.3 vs. O, 40.0 ± 2.0; Table 1) and was below the average menopausal age of 51 [Gold 2011]. The mean BMI of the O group (44.5 ± 2.8 kg/m2) is consistent with the obese classification. Because of the low numbers of lean women (BMI<24 kg/m2) undergoing breast reduction surgery at UAMS, the mean BMI for the comparison group was in the overweight range of 27.6 ± 0.8 kg/m2 and hence, this group was designated as non-obese (NO). All participants were confirmed breast cancer-free by pathology. The numbers of patients with term pregnancy (resulting in successful births) and of those reporting regular alcohol consumption (previous or current) were comparable between the two groups. Oral contraceptive use and smoking history (all previous smokers) were higher for women in the O group (Table 1). Only one patient (O group) reported a family history (maternal) of breast cancer.

Table 1 –

Study Subjects

| Group | BMI (kg/m2) | Age (yrs) | Parity*1 | Contraception*2 | Smoker* | Alcohol* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Obese (n=10) | 27.6 ± 0.8 | 36.1 ± 3.3 | 3/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 |

| Obese (n=10) | 44.5 ± 2.8 | 40.0 ± 2.0 | 2/10 | 3/10 | 4/10 | 2/10 |

Number of patients

Pregnancy resulted in childbirth

Contraception use

Figure 1a provides a schematic summary of the analyses performed on the collected breast tissues. To evaluate the purity of the dissected compartments and thus, ensure confidence that expression level differences in subsequently analyzed transcripts are specific to each compartment, tissue-specific biomarkers (vimentin, VIM; perilipin 1, PLIN1; keratin 1, KRT1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR from RNAs prepared from adipose and glandular epithelial tissues. Transcripts for VIM and PLIN1 were high in adipose tissue and were undetectable in the glandular compartment; by contrast, KRT1 transcripts were markedly enriched (by 1000-fold) in the glandular relative to the adipose compartment (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Experimental design.

(a) Premenopausal women undergoing breast reduction surgery at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Department of Surgery were consented to the study and provided breast tissues for analyses. Breast tissues were processed for gene expression (adipose and glandular compartments) and immunohistochemical (formalin-fixed whole breast) analyses. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were purchased from commercial sources as described under Materials and Methods. (b) The purity of the separated breast adipose and glandular compartments was evaluated by qRT-PCR of genes specific to each compartment [(Adipose- vimentin, VIM; perilipin 1, PLIN1); glandular epithelial- Keratin 1, KRT1)]. RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls for all analyses. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from adipose tissue values and were obtained from n=10 patients of the obese group. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.001 by Student’s t test.

Adipose morphometry

Adipocytes located at discrete anatomical sites differ in their biology, glucose and lipid metabolism, and endocrine regulation [Lee et al. 2013, Hill et al. 2018]. To characterize breast adipose of premenopausal women as a function of BMI, we evaluated breast tissues of NO and O women for: a) adipocyte size distributions and volumes in H&E-stained tissue sections; and b) adipocyte expression of lipid droplet-associated protein perilipin (PLIN1) by IHC. Adipocyte size distribution (Fig. 2a) and volumes (Fig. 2b) did not differ between the two groups. PLIN1 immunostaining was confined to adipocyte surface as expected, but did not differ in intensities between NO and O (Fig. 2c, 2d).

Figure 2. Phenotype of breast adipose tissue from premenopausal non-obese and obese women.

(a) Distribution of breast adipocyte sizes (expressed as a percent of the total numbers of adipocytes counted) from premenopausal non-obese (n=10) and obese (n=10) women. Paraffin-embedded breast tissue sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and images were captured by Aperio software. Adipocyte area (μm2) was determined from length and width of each cell. Analyzed adipocytes (100 total) were from four random visual fields per tissue sample, with each field showing 25 adjacent cells. (b) Adipocyte volume (μm3) was determined from calculated area x tissue thickness (5 μm). (c) Representative images of immunostained breast adipocytes of obese women in the absence (No Ab) and presence of anti-perilipin antibody. (d) Perilipin immunostaining intensities localized to adipocyte cell surfaces were quantified by Aperio software from 100 adipocytes located in 4 random visual fields per tissue section. Data (mean ± SEM) were obtained from n=10 patients per experimental group and expressed relative to NO values.

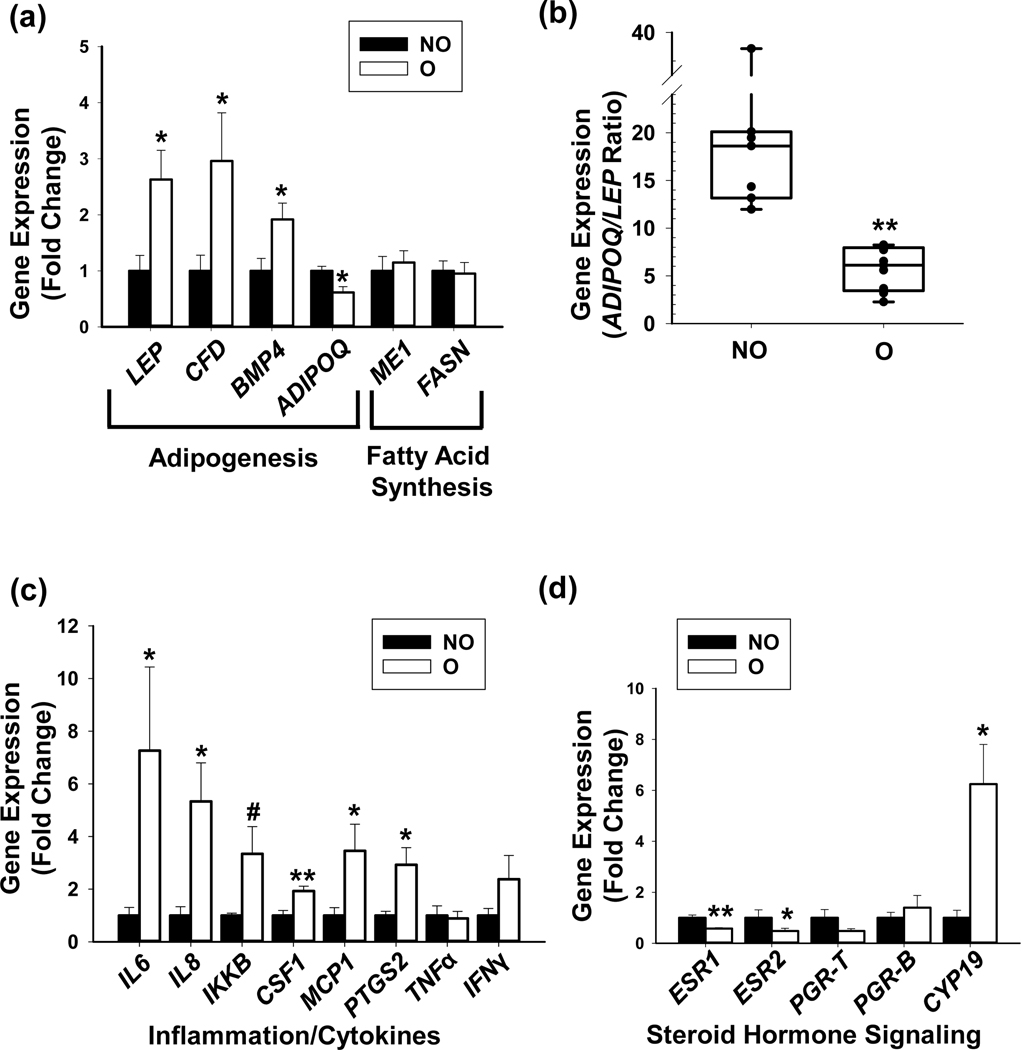

Adipogenic and inflammatory gene expression and steroid hormone signaling status in non-obese and obese breast adipose tissues

Obesity is associated with chronic and low-grade inflammation, higher estrogen synthesis and an altered response to steroid hormone receptor-mediated signaling in adipose tissue [Gerard & Brown 2018, Kolb & Zhang 2020]. We assessed the expression of genes encoding for a subset of adipogenic proteins, inflammatory cytokines/adipokines and steroid hormone-related components in NO and O groups. Transcript levels for Leptin (LEP), Complement factor D (CFD, also known as Adipsin) and Bone Morphometric Protein-4 (BMP4) were higher while those for Adiponectin (ADIPOQ) were lower, in O vs NO breast adipose (Fig. 3a). No differences in the transcript levels of Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) and Malic Enzyme 1 (ME1) were noted between the groups (Fig. 3a). Consistent with the significant changes in their respective transcript levels, the ratio of ADIPOQ to LEP mRNAs was higher for NO than for O (Fig. 3b). Levels of Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, Inhibitor of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Kinase subunit beta (IKKβ), Colony Stimulating Factor 1 (CSF1), Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), and Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 2 (PTGS2) transcripts were higher in O vs NO (Fig. 3C). No significant differences in transcript levels for Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α and Interferon Gamma (IFNγ) were found between the groups. Transcript levels for Estrogen Receptor (ESR) isoforms α and β (ESR1, ESR2) were lower, whereas those for Cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19), the terminal enzyme involved in estrogen synthesis [Simpson & Davis, 2018] were higher, in O vs. NO breast adipose (Fig 3d). There were no differences in transcript levels for Progesterone Receptor (PGR) total and B isoform (PGR-T, PGR-B) in adipose tissues between the groups.

Figure 3. Adipose gene expression patterns in breast tissues from premenopausal non-obese and obese women.

Isolated adipose tissues were evaluated for expression of selected genes representing distinct functional categories, by qRT-PCR. (a) Transcript levels of genes involved in adipogenesis (LEP, CFD, BMP4, ADIPOQ) and fatty acid synthesis (ME1, FASN). (b) The ratio of transcripts for ADIPOQ and LEP for non-obese and obese groups, obtained from (a) and expressed as mean ± SEM. (c) Transcript levels of genes associated with inflammation and immune response. (d) Transcript levels of genes associated with estrogen receptor (ESR) and progesterone receptor (PGR) signaling. For all analyses, RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from non-obese values and were obtained from n=10 patients per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.001 and #0.1<P< 0.05, by Student’s t test.

Breast glandular tissue from obese and non-obese women differ in inflammation and proliferation status

Breast adipose cells of O women may confer a highly inflammatory phenotype on neighboring breast glandular tissue. To examine this in the context of the premenopausal breast, we compared the expression levels of a subset of pro-inflammatory genes, which were up-regulated (IL6, IL8, CSF1, MCP1) or not altered (TNF-α) with obese status in breast adipose (Fig. 3c), in O and NO glandular tissues. In contrast to the corresponding adipose, breast glandular tissue from the O group manifested lower levels of IL6 and IL8 mRNAs than the NO group (Fig. 4a). Transcript levels for MCP1 were numerically lower (but did not reach statistical significance) for O relative to NO, whereas those for TNF-α and CSF1 were comparable between the two groups (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, transcript levels for proliferation-associated proteins Cyclin D1 (CCND1) and NOTCH-1 (NOTCH-1) were also lower for breast glandular tissue of O than NO cohort (Fig. 4b). By contrast, transcript levels for the pro-apoptotic protein BAX2 and for the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2 (data not shown) and for their respective ratios (BAX/BCL-2) (Fig. 4c) did not differ between O and NO groups.

Figure 4. Breast glandular tissue gene and protein expression of premenopausal non-obese and obese women.

(a) Transcript levels of genes involved in inflammation and immune response. RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from non-obese values and were obtained from n=10 subjects per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 by the Student’s t test. (b) Transcript levels of genes involved in proliferation (CCND1, NOTCH1). RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from non-obese values and were obtained from n=10 subjects per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P< 0.001, by Student’s t test. (c) The ratio of transcripts for BAX and BCL2 for non-obese and obese groups, expressed as mean ± SEM. (d) Representative images of anti-Ki67 immunostained breast glandular cells of non-obese (NO) and obese (O) women. Control panel is tissue section from breasts of obese women processed in parallel with the omission of the primary antibody incubation step. The percentage of nuclei-localized Ki67 immunopositive glandular luminal epithelial cells was determined by counting the number of immunopositive nuclei over the total number of cells counted per gland. Data (mean ± SEM) represent the analyses of 6 random glands per tissue section, each representing an individual patient and n=5 tissue sections per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t-test. (e) Representative images of anti-Galectin-1 immunostained breast glandular cells of non-obese (NO) and obese (O) women. Control panel is tissue section from breasts of obese women processed in parallel with the omission of the primary antibody incubation step. The anti-Galectin-1 immunostaining intensities in glandular myoepithelial layers were quantified by Aperio software, following procedures described under Materials and Methods. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed relative to non-obese values and represent the analyses of 6 random glands per tissue section, each from an individual subject and n=5 tissue sections per experimental group. #0.1<P< 0.05, by Student’s t test.

To confirm the higher proliferation status of breast epithelia from NO vs O as inferred from the higher NO expression of CCND1 and NOTCH1 (Fig. 4b), we evaluated the levels of Ki67 protein, a marker of proliferating cells, in breast tissues by immunohistochemistry. Immunostaining for Ki67 in breast glandular epithelia from both NO and O groups was localized to the nuclear compartment (Fig. 4d). The NO group showed a greater percentage of nuclear Ki67-positive luminal epithelial cells than did the O group (Fig. 4d).

To explore a potential basis for the inverse relationship in inflammatory and proliferative status of adipose and glandular epithelia in breast tissues of O and NO women, we evaluated galectin-1 (GAL-1) protein expression in O and NO samples. GAL-1, a member of the β-galactoside-binding protein and produced by adipocytes, is associated with cessation of acute and chronic inflammation [Sundblad et al 2017], and implicated in inhibiting tumor development when it binds to tumor cells [Geiger et al 2016]. In breast tissues, GAL-1 immunostaining localized predominantly to glandular myoepithelial cells and was undetectable in underlying glandular luminal epithelium (Fig. 4e). Moreover, myoepithelial GAL-1 immunostaining intensities tended to be higher in O than in NO breast tissues (Fig. 4e).

Enhanced recruitment of T regulatory cells to obese adipose

To address the inverse association between higher expression of inflammation (IL6, IL8, MCP1) and estrogen biosynthetic enzyme (CYP19) genes in obese adipose and the lower proliferative and inflammatory status of corresponding glandular tissue (Fig. 4), we evaluated the potential participation of immune cells in the paracrine interactions between these tissue compartments as summarized in Fig. 5a. The rationale for this approach is two-fold: first, estrogens promote CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cell expansion [Prieto & Rosenstein, 2006] and second, immune Foxp3-expressing Treg cells are recruited to and reside in adipose tissues where they are known to regulate inflammation [Zeng et al. 2018]. We addressed the presence and possible differential recruitment of Treg cells in breast adipose of O vs NO women, by measuring the relative transcript levels of T cell receptor alpha and beta chains (TCRa, TCRb), TCR co-receptors CD3e and CD4 and Treg biomarker FOXP3, in NO and O breast adipose. Transcript levels of TCRa, TCRb, Cd3e, CD4 (Fig. 5b) and of FOXP3 (Fig. 5c) were higher in O than NO breast adipose. The higher levels of FOXP3 transcripts in breast adipose of O relative to NO paralleled those of the transcript for the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 (Fig. 5c). T-BET and GATA3 regulate CD4+ T cell Th1 and Th2 cell fate decision, respectively [Morel 2018]. As shown in Fig. 5c, Th1 cell recruitment (determined from T-BET transcript levels) to the breast adipose paralleled that of Treg cells, while recruitment of GATA3-expressing Th2 cells did not differ between O and NO breast adipose (Fig. 5c). The lack of comparable differences in FOXP3 and IL10 transcript levels between O and NO glandular tissue supports the preferential recruitment of Treg cells to and of IL10 expression by, the O adipose (Fig, 5d).

Figure 5. Adipose resident immune cells in breasts of premenopausal non-obese and obese women.

(a) Proposed model that integrates the potential involvement of immune cells in the paracrine signaling between breast adipose and neighboring glandular epithelium. The pathways indicated with question marks (?) are unknowns and addressed by data presented below as described in the text. (b) Transcript levels of breast adipose-associated T cell receptor chains alpha and beta (TCRa, TCRb) and TCR co-receptors CD3e and CD4. (c) Transcript levels of breast adipose-associated FOXP3, T-BET, GATA3 and IL10. (d) Transcript levels of breast glandular epithelial-associated FOXP3 and IL10. For all analyses, RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from non-obese values and were obtained from n=10 subjects per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P< 0.001, by Student’s t test.

Adipose IL10 expression and glandular phenotype

The lower proliferation status of breast glandular epithelial cells of O women may be partly due to cell cycle arrest, leading to cellular senescence. Promotion of senescence has been ascribed to IL10 in a number of cell types [Novakova et al. 2010, Huang et al 2020]. To examine the possibility that breast adipose-associated IL10 expression is correlated with glandular epithelial cell senescence in the context of the premenopausal breast, we analyzed breast tissues for expression of cell senescence biomarkers TP53, p21 and β-galactosidase (β-GAL) by IHC using specific antibodies to these proteins. Breast tissues from O women exhibited a higher percentage of nuclear TP53-positive epithelial cells than from NO women (Fig. 6a). Further, levels of p21 transcripts (Fig. 6b) and of nuclear-localized p21 protein (Fig. 6c) were higher in O than NO glandular compartment. KRT1 transcript levels in O vs. NO did not differ, indicating the specificity of the noted changes in TP53 and p21 expression (Fig. 6b). β-GAL immunostaining was present in the cytoplasmic compartment of glandular epithelium, but unlike for TP53 and p21, its expression only tended to be higher for O than NO (Fig. 6d). Relative telomere length analyses revealed comparable telomere lengths between NO (1.07±0.30 ×10 3kb/diploid cell) and O (1.10±0.28 ×10 3kb/diploid cell) glandular epithelial cells.

Figure 6. Expression of senescence/proliferative-associated biomarkers in breast tissues of premenopausal non-obese and obese women.

(a) Representative images of anti-TP53 immunostained breast glandular cells of non-obese (NO) and obese (O) women. Control panel is tissue section from breasts of obese women processed in parallel with the omission of the primary antibody incubation step. The percent of nuclei-localized, TP53 immunopositive glandular epithelial cells was determined by counting the number of immunopositive nuclei over the total number of cells counted per gland. Data (mean ± SEM) represent the analyses of 6 glands per tissue section, each representing an individual patient and n=5 tissue sections per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t-test. (b) Transcript levels of p21 and KRT1 in breast glandular epithelium. RPL19 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNAs were normalization controls. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as fold-change from non-obese values and were obtained from n=10 subjects per experimental group. *P≤ 0.05. (c) Representative images of anti-p21 immunostained breast glandular cells of non-obese (NO) and obese (O) women. Control panel is a tissue section from a breast of obese women processed in parallel with the omission of the primary antibody incubation step. The percentages of nuclei-localized p21 in O and NO breasts were determined following those for TP53 (above). Data (mean ± SEM) designated as p21 nuclear staining, are expressed as fold-change from non-obese breast and represent the analyses of 6 glands per tissue section, each from an individual patient and n=5 tissue sections per experimental group. *P ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t-test. (d) Representative images of anti-β-Galactosidase immunostained breast glandular cells of non-obese (NO) and obese (O) women. Control panel is tissue section from breasts of obese women processed in parallel with the omission of primary antibody incubation step. Immunostaining intensities in glandular cells were quantified using the Aperio software, following procedures described under Materials and Methods. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed relative to NO values and represent the analyses of 6 glands per tissue section, each from individual subject and n=5 tissue sections per experimental group. #0.1<P< 0.05, by Student’s t test.

To evaluate a causal (direct) role of adipose-associated IL10 in glandular epithelial proliferation, two non-tumor breast epithelial cell lines MCF10A and HMEC were treated with recombinant human IL10 (rhIL10) and assessed for cell viability, apoptosis status and transcript levels of proliferative (Cyclin D1) and anti-proliferative/pro-senescent/pro-apoptotic (TP53, p21, PTEN) biomarkers, relative to control cells. In initial studies (data not shown), MCF10A cells were treated with different concentrations of rhIL10 after serum starvation (18h) and evaluated at two time points (48h and 65h) to determine the optimal concentration for cell viability response (data not shown). Relative to respective controls, MCF10A and HMEC incubated with rhIL10 (10 ng/ml) showed significant reductions in cell proliferation, 48h and 65h post-treatment (Fig. 7a). IL10 increased the basal apoptotic status of MCF10A at both the early and late stages, but showed no effects on HMEC, 72h post-treatment (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7. IL10 effects on proliferation, apoptosis and gene expression of nontumor breast epithelial cell lines MCF10A and HMEC.

(a) MCF10A and HMEC were cultured in media without (vehicle control) and with IL10 (10 ng/ml) and evaluated for cell proliferation at 48h and 65h post-treatment, using the CCK8 assay kit. Data are presented as mean ±SEM (n=6 wells/treatment group) and were compared to vehicle control. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P< 0.001, by Student’s t test. (b) Distribution of MCF10A and HMEC in early and late apoptotic stages as a function of IL10 treatment (10 ng/ml, 72 h). The percentages of cells in each category were determined from Annexin V/propidium iodide-staining cells separated using Attune NxT acoustic focusing flow cytometer and analyzed using the Flow-Jo program. (c) Transcript levels of TP53, p21, CCND1 and PTEN in control and IL10-treated (10 ng/ml) MCF10A and HMEC, 24h post treatment. RPL19 and TBP mRNAs were normalization controls. Data are presented as mean ±SEM (n=4) and are expressed as fold-change from control cells. #0.1<P< 0.05, *P ≤ 0.05 and **P< 0.001, by Student’s t test.

For gene expression analyses, cells were collected 24 h after treatment with rhIL10 (10 ng/ml) or media alone and subjected to qPCR. In MCF10A cells, transcript levels for TP53 and p21 were increased and those for CCND1 were reduced by IL10, relative to control cells (Fig. 7c). Expression profiles of TP53, p21 and CCND1 in HMEC with and without IL10-treatment followed those of MCF10A cells (Fig. 7c). Tumor suppressor PTEN transcript levels tended to increase with IL10-treatment relative to control cells, in MCF10A but not in HMEC (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

Obesity is a known risk factor for many adult chronic diseases including breast cancer [Reeves et al. 2007, Guh et al. 2009, Picon-Ruiz et al. 2017]. Nevertheless, the risk conferred by obesogenic status (measured as BMI) on breast cancer in women is reproductive age-dependent, with an inverse association for premenopausal women. The molecular basis for this seemingly paradoxical relationship remains poorly defined. To understand the cellular dynamics of breast cancer initiation under this context, we used mammosplasties from premenopausal obese (O) and non-obese (NO) women with no diagnosed breast and other cancers for interrogating the cellular and molecular phenotypes of isolated breast adipose tissues and associated breast glandular epithelium. Our analyses did not include patients exclusively in the lean group (Table 1) due to the limited number of women with BMI<25 Kg/m2 undergoing mammoplasties at our institution. Our experimental groups (O vs NO) demonstrated phenotypic differences in breast glandular tissues, consistent with the reported 8% reduction in premenopausal breast cancer risk, per 5 Kg/m2 increase in BMI [Picon-Ruiz et al. 2017]. While breast adipose tissues from O women were substantially adipogenic and more inflammatory than from NO counterparts, the gene expression profiles of respective glandular epithelia displayed counter-intuitive trends, with NO breast epithelia exhibiting elevated pro-inflammatory (IL6, IL8) and proliferative (CCND1, NOTCH1) gene expression and higher nuclear presence of proliferation marker Ki67 protein, than epithelia from O breasts. NO breast glandular tissue also showed higher expression levels of ESR1 than corresponding O breast glandular tissue, consistent with enhanced estrogen-mediated signaling associated with breast cancer progression. Further, breast epithelia from NO women displayed lower expression of pro-senescence biomarkers (p21, TP53), despite showing comparable cellular telomere lengths, from O women. Taken together, our findings provide support to a working model whereby the premenopausal obese breast adipose initiates a dialog within the local environment of glandular epithelial cells by utilizing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 to activate the TP53/p21 signaling pathway, leading to a reduction in epithelial cell proliferation and potentially, lower risk for premenopausal breast cancer (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed model for the paracrine action of breast adipose-associated IL10 on the proliferative, inflammatory and senescent-like status of breast glandular epithelial cells. In this model, an increase in P450 aromatase (CYP19) expression in obese adipose promotes the expansion and activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes, leading to adipose recruitment of FOXP3+ T regulatory cells. IL10 produced by both the breast adipose and recruited FOXP3+Treg cells contributes to the distinct phenotype (lower inflammation and proliferation status) of breast glandular epithelial cells of premenopausal obese women. Whether the obese breast adipose promotes a senescence-like phenotype in corresponding breast glandular epithelial cells remains unclear (?).

Our results show that obesity confers distinct characteristics to breast adipose relative to other regional fat depots. Concordant with fat depots at different anatomical sites (e.g., subcutaneous, visceral) [Derosa et al. 2013, Blázquez-Medela et al. 2019], breast adipose from O women showed higher transcript levels of adipocyte markers LEP, CFD and BMP4 and lower ADIPOQ/LEP ratio than from NO women. Nevertheless, notable differences exist among these fat depots. FASN and ME1 transcript levels, which in visceral and subcutaneous fat depots are higher with obesogenic status [Berndt et al. 2007], were unaffected in breast adipose by subject BMIs. PLIN1 is a highly abundant adipocyte protein that coats lipid droplets and functions to regulate lipid storage and lipolysis [Smith & Ordovas 2012]. In subcutaneous and visceral fat, PLIN1 levels correlated positively with obesity status and with adipocyte size [Kern et al. 2012]. By contrast, we found that breast adipose tissues of O and NO women had comparable PLIN1 expression, a finding consistent with the similar breast adipocyte volumes and size distributions for the two groups. In a recent study of premenopausal women, no associations were found between breast adipose and visceral fat volumes and between breast adipose volume and cardiometabolic risk factors, after adjusting for BMI [Schautz et al 2011]. Thus, differences in breast adipose parameters between O and NO women may largely translate to paracrine (local) regulation of neighboring breast glandular cells, rather than to longer-range (systemic/endocrine) effects.

Obesity is known to affect the profiles of immune cells within adipose tissues [Liu & Nikolajczyk, 2019]. A major finding of our study is the potential contribution of adipose-recruited FoxP3+Treg cells to glandular epithelial proliferation in premenopausal breast. While systemic low-grade chronic inflammation is linked to adiposity and enhanced cell proliferation [Sun et al. 2012], we show here that the highly inflammatory breast adipose tissue from O women associated with reduced glandular epithelial proliferation. Based on published literature and our own experimental results, we provide a conceivable pathway by which the high estrogenic capacity of the premenopausal obese breast can lead to enhanced Treg cell recruitment and accumulation in the adipose environment, to increase the amounts of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 within the vicinity of breast glandular compartment (Fig. 5a, Fig. 8). The likelihood that IL10 plays a functional role in the control of glandular epithelial proliferation, was supported by the reduced cell viability and the elicited gene expression patterns (higher TP53 and p21; lower CCND1), concordant with those noted in O breast glandular tissue in vivo, when human breast epithelial cell lines MCF10A and HMEC were treated with physiological levels (10 ng/ml) of IL10. Thus, breast adipose of premenopausal obese women likely employs distinct mechanisms from those of obese post-menopausal breast, to sense and promptly resolve over-activated inflammatory responses in neighboring epithelial cells to curtail uncontrolled proliferation [Kolodin et al. 2015]. Recent studies have shown that the heterogeneity among adipocytes within a single white adipose depot may underlie distinct adipocyte inflammatory activity [Luong et al. 2019]. It is tempting to speculate that differing adipocyte subpopulations in pre- and post-menopausal breast tissues may be central to the distinct responses of breast epithelial cells to the same obesogenic stimuli imposed by the breast adipose.

Our findings of lower proliferation status of breast glandular epithelia from premenopausal obese women align with a recent report showing that as BMI increases, gene expression in breast epithelial cells of premenopausal women show a pattern consistent with decreased proliferation [Zhao et al. 2018]. Cellular senescence is a known defensive mechanism to inhibit proliferation of cells with extensive DNA damage [Rodier & Campisi 2011] imposed in part by chronic inflammation and which may be linked to chemotherapy resistance in cancers [Guillon et al. 2019]. Our data showing higher nuclear levels of TP53 and p21 and a non-significant (but tending) increase in β-GAL expression coincident with comparable mean relative telomere lengths, in O relative to NO breast epithelial cells, do not completely support the establishment of a full-blown senescence phenotype in O breast epithelium. Rather, they suggest a pause in epithelial cell proliferation, providing an opportunity for these cells to transition to a new steady-state, recalibrate to homeostasis and hence, escape the uncontrolled proliferative pathway [Herranz & Gil 2018].

While there are multiple stimuli presented to breast epithelial cells by the breast adipose in the context of obesity, we posit that the inhibition of cell proliferation and by inference, reduced breast cancer risk is significantly driven by chronic exposure to adipose/Treg-derived immunomodulatory molecule IL10. To our knowledge, our study constitutes the first investigation on the positive association between adipose-associated IL10 and premenopausal normal breast phenotype. IL10 has been largely studied in the context of breast tumor cells or in normal breast tissue with adjacent tumor tissue, where it is reported to exhibit a tumor promoter or a tumor suppressor role [Llanes-Fernández et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2010; Hamidullah et al., 2012; Bishop et al., 2015]. Our identification of IL10 as a potential mediator of early (protective) events in breast cancer development is correlative, rather than causative, but is strengthened by the collective effects elicited by IL10 in vitro on gene expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis in two non-tumorigenic human breast cell lines MCF10A and HMEC. The distinct apoptotic responses of MCF10A (increased) and HMEC (no effect) to IL10 likely reflect their different biological backgrounds with HMEC more akin to normal mammary epithelial phenotype (i.e., isolated from normal reduction mammoplasty) than MCF10A, which originated from benign proliferative breasts.

Of relevance to the biology of breast glandular epithelia and subsequent breast cancer risk is our findings of the tendency for higher expression of GAL-1 in breasts of O relative to NO subjects. Galectins comprise a large family of soluble lectins located inside and outside of cells and implicated in many tumor-associated events including apoptosis, proliferation, adhesion and migration [Brinchman et al. 2018]. A recent study showing promotion of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation upon binding of GAL-1 to breast tumor MCF-7 cells [Geiger et al. 2016] aligns with our findings of reduced breast glandular epithelial Ki67 protein levels and lower CCND1 gene expression coincident with enhanced GAL-1 localization in breast myopeithelial cells of O women. In another study, however, loss of GAL-1 function led to inhibition of immunosuppression and metastasis in breast cancers [Dalotto-Moreno et al 2013]. These results suggest the context-dependent regulatory role of GAL-1 in normal vs. diseased breast and require further inquiry.

We found that premenopausal breast glandular tissues displayed higher ESR1 and ESR2 transcript levels for NO than O women, implicating the participation of estrogen receptor signaling in the elevated breast cancer risk of premenopausal non-obese women. Two previous studies are consistent with this suggestion. In one study of premenopausal women between 18 to 54 years of age, the inverse associations between BMI and breast cancer risk were stronger for ESR1/PGR-positive than for hormone receptor–negative breast cancer [Schoemaker et al. 2018]. In the other study, premenopausal women with lower BMI showed higher follicular and luteal estradiol levels than premenopausal women with higher BMI [Tworoger SS et al. 2006]. The validation of the latter relationship was not possible in the current study due to the lack of available serum estradiol levels for our patient cohorts. Nevertheless, our findings of higher CCND1 transcript levels and lower TP53 protein expression, which are respectively, positively and negatively targeted by estrogen-dependent ESR1 signaling, in breast glandular tissue of NO relative to O women provide support for the convergence of estrogen-dependent ESR1 and growth signaling pathways [Casimiro et al. 2013] for promotion of breast cancer risk in premenopausal NO women.

Recognized limitations to the current study include the relatively small numbers of patient cohorts and the lack of clinical information on their menstrual cycle phase, other reproductive dysfunctions (e.g., polycystic ovarian syndrome) and potential metabolic-associated disorders. The contribution of the immune microenvironment was indirectly interrogated through transcriptional profiles; in future studies involving the participation of additional patient cohorts, we plan to directly identify the types of immune cells populating premenopausal O and NO breast adipose and glandular tissues by FACS analyses to further validate the heterogeneity of breast adipose-recruited immune cells and their respective contribution to breast epithelial/adipose cross-talk. Further, the candidate gene approach utilized here precluded a more global perspective on transcriptomic changes, which we plan to address using unbiased RNA seq studies.

In conclusion, our data provide support to the hypothesis that paracrine regulation by breast adipose elicits molecular and phenotypic changes in breast glandular tissue that are consistent with lower breast cancer risk in premenopausal obese women. We identify adipose-recruited immune (FOXP3+ Treg) cells and IL10 as potential mediators of the protective effects of obese breast adipose by inhibiting cell proliferation to resolve adipose-elicited local inflammatory signals. Further studies are merited to expand the mechanistic analyses described in this pilot study using a larger cohort of premenopausal women with more divergent BMIs (lean vs. obese) and within a wider age-range (young adults vs. peri-menopausal) to gain a better understanding of early breast cancer causation and strategies for prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Remelle Eggerson, UAMS Tissue Repository and Procurement Service Coordinator and Hillary Mayberry, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery for their valuable assistance in these studies.

Funding: This work was supported by the UAMS Barton Pilot Grant; UAMS Chancellor’s Research Development Award; NIGMS/NIH (P20 GM103429); NIH TL1 TR003109; and NIH/NCI RO1CA136498. Iad Alhallak is a recipient of the 2019 Endocrine Society of America Summer Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Disclosure Summary: The authors declare no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this study.

References

- Agurs-Collins T, Ross SA, Dunn BK 2019The many faces of obesity and its influence on breast cancer risk. Frontiers in Oncology 9765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim HA Jr, Michiels S, Bedard PL, Singhal SK, Criscitiello C, Ignatiadis M, Haibe-Kains B, Piccart MJ, Sotiriou C, Loi S 2012Elucidating prognosis and biology of breast cancer arising in young women using gene expression profiling. Clinical Cancer Research 181341–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badache A, Hynes NE 2001Interleukin 6 inhibits proliferation and, in cooperation with an epidermal growth factor receptor autocrine loop, increases migration of T47D breast cancer cells. Cancer Research 61383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt J, Kovacs P, Ruschke K, Klöting N, Fasshauer M, Schön MR, Körner A, Stumvoll M, Blüher M 2007Fatty acid synthase gene expression in human adipose tissue: association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 501472–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop RK, Valle Oseguera CA, Spencer JV 2015Human Cytomegalovirus interleukin-10 promotes proliferation and migration of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell Microenviron 2e678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez-Medela AM, Jumabay M, Boström KI 2019Beyond the bone: Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in adipose tissue. Obesity Review 20648–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinchmann MF, Patel DM, Iversen MH 2018The role of galectins as modulators of metabolism and inflammation. Mediators Inflammation 8. 10.1155/2018/9186940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Lee HC, Liu S, Quick CM, Fernandes LM, Simmen FA, Tsai SJ, Simmen RCM 2018Notch-1 signaling activation and progesterone receptor expression in ectopic lesions of women with endometriosis. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2765–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder A, Akrobetu D, Pandiri AR, Ton K, Kim S, Labow BJ, Nuzzi LC, Firriolo JM, Schneider SS, Fenton SE, et al. 2020Investigation of the adolescent female breast transcriptome and the impact of obesity. Breast Cancer Research 2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro MC, Wang C, Li Z, Sante GD, Willmart NE, Addya S, Chen L, Liu Y, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG 2013Cyclin D1 determines estrogen signaling in the mammary gland in vivo. Mol Endocrinology 271415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liu L, Zhou Q, Imam MU, Cai J, Wang Y, Qi M, Sun P, Ping Z, Fu X 2017Body mass index had different effects on premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer risks: a dose-response meta-analysis with 3,318,796 subjects from 31 cohort studies. BMC Public Health 17936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chollet-Hinton L, Olshan AF, Nichols HB, Anders CK, Lund JL, Allott EH, Bethea TN, Hong C, Cohen SM, Khoury T, et al. 2017Biology and etiology of young-onset breast cancers among premenopausal African-American women: results from the AMBER consortium. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 261722–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalotto-Moreno T, Croci DO, Cerliani JP, Martinez-Allo VC, Dergan-Dylan S, Méndez-Huergo SP, Stupirski JC, Mazal D, Osinaga E, Toscano MA, et al. 2013Targeting galectin-1 overcomes breast cancer-associated immunosuppression and prevents metastatic disease. Cancer Research 731107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derosa G, Fogari E, D’Angelo A, Bianchi L, Bonaventura A, Romano D, Maffioli P 2013Adipocytokine levels in obese and non-obese subjects: an observational study. Inflammation 36914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirat B, Bochet L, Dabek M, Daviaud D, Dauvillier S, Majed B, Wang YY, Meulle A, Salles B, Gonidec SL, et al. 2011Cancer-associated adipocytes exhibit an activated phenotype and contribute to breast cancer invasion. Cancer Research 712455–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton SE, Reed C, Newbold RR 2012Perinatal environmental exposures affect mammary development, function, and cancer risk in adulthood. Annual Review of Pharmacology Toxicology 52455–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger P, Mayer B, Wiest I, Schulze S, Jeschke U, Weissenbacher T 2016Binding of galectin-1 to breast cancer cells MCF7 induces apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation in vitro in a 2D- and 3D- cell culture model. BMC Cancer 16870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard C, Brown KA 2018Obesity and breast cancer-Role of estrogens and the molecular underpinnings of aromatase regulation in breast adipose tissue. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 46615–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold EB 2011The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstetrics Gynecology Clinics of North America 38425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH 2009The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon J, Petit C, Toutain B, Guette C, Lelièvre E, Coqueret O 2019Chemotherapy-induced senescence, an adaptive mechanism driving resistance and tumor heterogeneity. Cell Cycle 182385–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidullah S, Changkija B, Konwar R 2012Role of interleukin-10 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 13311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H, McCormack V, Fidler-Benaoudia MM 2020Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Global Health 8e1027–e1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz N, Gil J 2018Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1281238–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt RA, Engmann NJ, Balke K, Rehkopf DH 2020Paradigm II Multidisciplinary Panel. A complex systems model of breast cancer etiology: The Paradigm II conceptual model [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 8]. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JH, Solt C, Foster MT 2018Obesity associated disease risk: the role of inherent differences and location of adipose depots. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himbert C, Delphan M, Scherer D, Bowers LW, Hursting S, Ulrich CM 2017Signals from the adipose microenvironment and the obesity-cancer link-a systematic review. Cancer Prevention Research 10494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat GC, Kim MY, Lee JS, Ho GY, Going SB, Beebe-Dimmer J, Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Rohan TE 2017Metabolic obesity phenotypes and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 261730–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF 2006Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. Journal of Clinical Oncology 242137–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern PA, Di Gregorio G, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G 2004Perilipin expression in human adipose tissue is elevated with obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 891352–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb R, Zhang W 2020Obesity and breast cancer: a case of inflamed adipose tissue. Cancers (Basel) 121686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodin D, van Panhuys N, Li C, Magnuson AM, Cipolletta D, Miller CM, Wagers A, Germain RN, Benoist C, Mathis D 2015Antigen- and cytokine-driven accumulation of regulatory T cells in visceral adipose tissue of lean mice. Cell Metabolism 21543–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanes-Fernández L, Alvarez-Goyanes RI, Arango-Prado M del C, Alcocer-González JM, Mojarrieta JC, Pérez XE, López MO, Odio SF, Camacho-Rodríguez R, Guerra-Yi ME, et al. 2006Relationship between IL-10 and tumor markers in breast cancer patients. Breast 15482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Nikolajczyk BS 2019Tissue immune cells fuel obesity-associated inflammation in adipose tissue and beyond. Front Immunol. 101587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Luong Q, Sharma R, Dreyfuss JM, Ussar S, Kahn CR 2019Developmental and functional heterogeneity of white adipocytes within a single fat depot. EMBO Journal 38 e99291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK 2013Adipose tissue heterogeneity: implication of depot differences in adipose tissue for obesity complications. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 341–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LY, Wang F, Cui SD, Tian FG, Fan ZM, Geng CZ, Cao XC, Yang ZL, Wang X, Liang H, et al. 2017Distinct effects of body mass index and waist/hip ratio on risk of breast cancer by joint estrogen and progestogen receptor status: results from a case-control study in northern and eastern china and implications for chemoprevention. Oncologist 121431–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Wagner WM, Gad E, Yang Y, Duan H, Amon LM, Van Denend N, Larson ER, Chang A, Tufvesson H, et al. 2010Treatment failure of a TLR-7 agonist occurs due to self-regulation of acute inflammation and can be overcome by IL-10 blockade. J Immunol 1845360–5367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong Q, Lee K, Sharma R, Huang J 2019Adipocyte subpopulations mediate obesity-associated inflammation in adipose tissues. Journal of the Endocrine Society 3 (Suppl 1) OR12–4. [Google Scholar]

- Morel PA 2018Differential T-cell receptor signals for T helper cell programming. Immunology 15563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen QH, Pervolarakis N, Blake K, Ma D, Davis RT, James N, Phung AT, Willey E, Kumar R, Jabart E, et al. 2018Profiling human breast epithelial cells using single cell RNA sequencing identifies cell diversity. Nature Communications 92028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh H, Charvat H, Freisling H, Noh H, Charvat H, Freisling H, Ólafsdóttir GH, Ólafsdóttir EJ, Tryggvadóttir L, Arnold A, et al. 2020Cumulative exposure to premenopausal obesity and risk of postmenopausal cancer: A population-based study in Icelandic women. International Journal of Cancer 147793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova Z, Hubackova S, Kosar M, Janderova-Rossmeislova L, Dobrovolna J, Vasicova P, Vancurova M, Horejsi Z, Hozak P, Bartek J, et al. 2010Cytokine expression and signaling in drug-induced cellular senescence. Oncogene 29273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabona JM, Simmen FA, Nikiforov MA, Zhuang D, Shankar K, Velarde MC, Zelenko Z, Giudice LC, Simmen RC 2012Krüppel-like factor 9 and progesterone receptor coregulation of decidualizing endometrial stromal cells: implications for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97E376–E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Lee HE, Li H, Shipitsin M, Gelman R, Polyak K 2010Heterogeneity for stem cell-related markers according to tumor subtype and histologic stage in breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 16876–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. 2000Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OW, Polyak K 2010Stem cells in the human breast. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picon-Ruiz M, Morata-Tarifa C, Valle-Goffin JJ, Friedman ER, Slingerland JM 2017Obesity and adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: Mechanistic insights and strategies for intervention. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians 67378–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K 2011Heterogeneity in breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1213786–3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto GA, Rosenstein Y 2006Oestradiol potentiates the suppressive function of human CD4 CD25 regulatory T cells by promoting their proliferation. Immunology 11858–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D 2007Million Women Study Collaboration. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ 3351134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F, Campisi J 2011Four faces of cellular senescence. Journal of Cell Biology 192547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I. Melino G 2013Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene 325129–5143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schautz B, Later W, Heller M, Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A 2011Associations between breast adipose tissue, body fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk in women: cross-sectional data and weight-loss intervention. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 65784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker MJ, Nichols HB, Wright LB, Brook MN, Jones ME, O’Brien KM, Adami H, Baglietto L, Bernstein L, Bertrand KA, et al. 2018Association of body mass index and age with subsequent breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. JAMA Oncology 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson ER, Davis SR 2001Minireview: aromatase and the regulation of estrogen biosynthesis--some new perspectives. Endocrinology 1424589–4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Ordovás JM 2012Update on perilipin polymorphisms and obesity. Nutriton Review 70611–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong AL, Strong TA, Rhodes LV, Semon JA, Zhang X, Shi Z, Zhang S, Gimble JM, Burow ME, Bunnell BA 2013Obesity associated alterations in the biology of adipose stem cells mediate enhanced tumorigenesis by estrogen dependent pathways. Breast Cancer Research 15R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Simmen RC 2009Soy isoflavone genistein upregulates epithelial adhesion molecule E-cadherin expression and attenuates beta-catenin signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 30331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Ji Y, Kersten S, Qi L 2012Mechanisms of inflammatory responses in obese adipose tissue. Annual Review of Nutrition 32261–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundblad V, Morosi LG, Geffner JR, Rabinovich GA 2017Galectin-1: a jack-of-all-trades in the resolution of acute and chronic inflammation. Journal of Immunology 1993721–3730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Baer H, Rich-Edwards J, Michels KB, Barbieri RL, Dowsett M, Hankinson SE 2006Birthweight and body size throughout life in relation to sex hormones and prolactin concentrations in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 152494–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader JE, Stingl J 2014Mammary stem cells and the differentiation hierarchy: current status and perspectives. Genes & Development 281143–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Sun X, Xiao L, Xie Z, Bettini M, Deng T 2018A Unique Population: Adipose-Resident Regulatory T Cells. Frontiers in Immunology 92075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wang J, Fang D, Chatterton RT, Stearns V, Khan SA, Bulun SE 2018Adiposity results in metabolic and inflammation differences in premenopausal and postmenopausal women consistent with the difference in breast cancer risk. Hormones and Cancer 9229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]