It has been seven months since the beginning of New York State’s emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As of this writing, there have been 7.7 million COVID-19 cases and 214 000 deaths in the United States.1 SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) and COVID-19 represent an unprecedented threat to the lives and livelihoods of our community—globally, nationally, and locally. It has become clear that COVID-19 is not the great “equalizer” but quite the opposite, magnifying and bringing to the fore the detrimental, unignorable impact of long-standing systemic inequities. To focus beyond the disparities in COVID-19 fatalities and the disproportionate burden on hospitals and critical care, we must think about equitable strategies to address the longer-term health and socioeconomic impact.

Here we tell the story of our fractured primary care system, an extension of long-standing structural inequity, the further-exacerbated health inequities laid bare by the pandemic,2 and the perpetuating impact of deferred care. We also discuss the potential power of community-based care ecosystems with patients at the center.

PRE–COVID-19: A BROKEN HEALTH CARE ECOSYSTEM

Despite the highest per capita spending, various authorities have consistently ranked the US health care system the worst among developed countries.3 Poor performance in access, equity, and efficiency results in poor patient care experiences, poor health outcomes, and uncontained costs. Rather than overtaxing clinicians to deliver comprehensive solutions through isolated treatments, we must address the needs arising from deeply embedded social factors and, ultimately, drive improvements in access, equity, and efficiency. People who are high utilizers of health care services often have complex medical, behavioral and social needs.

Social determinants of health—the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work, age, and worship, which shape our health trajectories—drive more than 80% of health outcomes. Yet, up to 88% of the US health care budget is devoted to providing medical services, leaving many patients’ needs unaddressed as they remain caught in a cycle of requiring more clinical care.4 These inequities have been decades in the making. Across the United States, racism is built into the politics and structure of the health care system, public health infrastructure, and perceptions of the social safety net.5

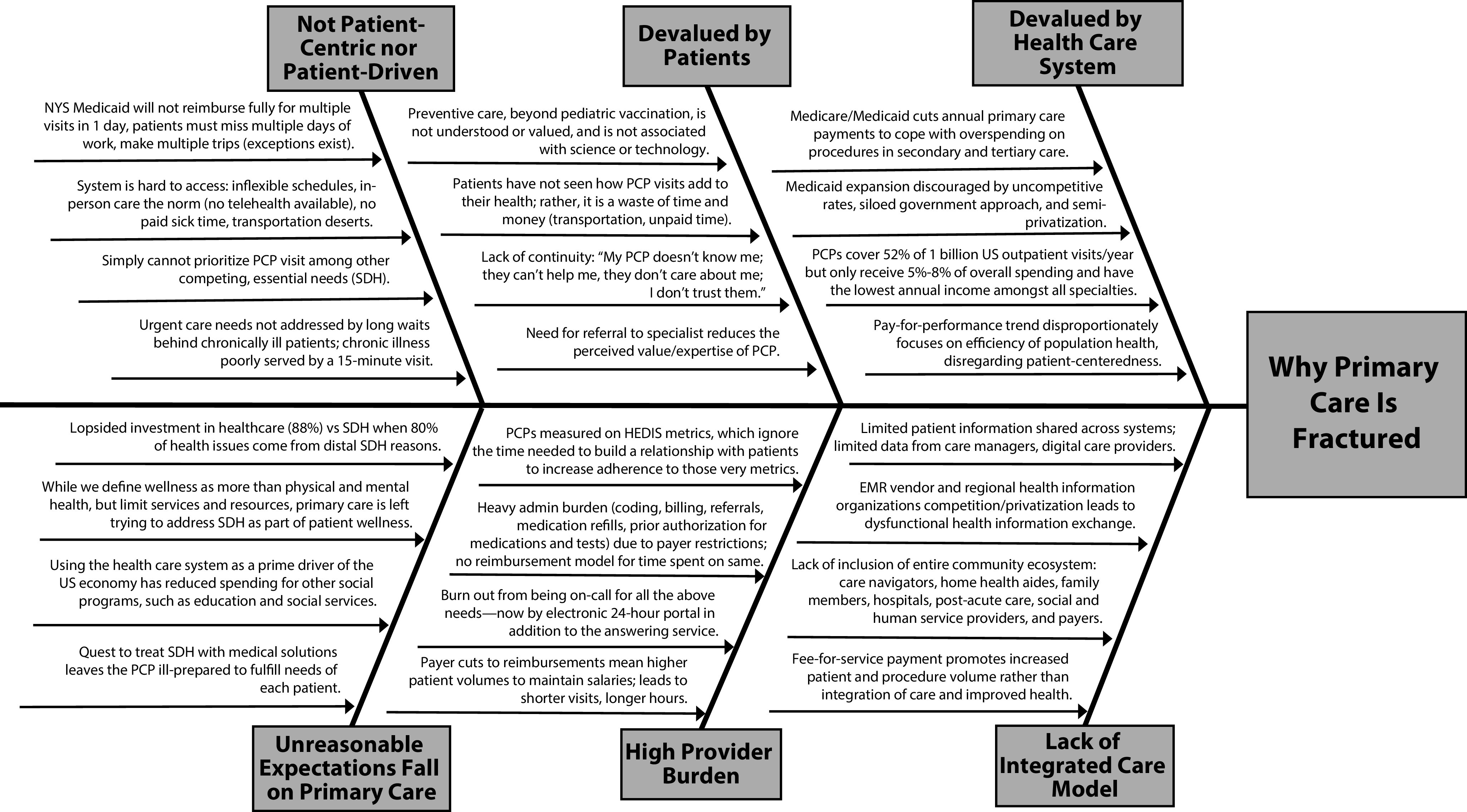

Primary care includes the specialties of adult internal medicine, pediatrics, and family medicine. It is intended to be the first place that people go when seeking health care, whether to treat symptoms of illness or prevent illness. Well before the pandemic, emergency rooms and urgent care centers had become preferred “first places” to seek care. This is in part because our health care ecosystem is fractured (Figure 1) and in part because we have a sick-care culture, not a preventive-care culture. In 2016, preventive care was the reason for a visit only one third of the time, even in the case of children.6

FIGURE 1—

Fishbone Diagram: Broken Primary Care System

Note. EMR = electronic medical record; HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; NYS = New York State; PCP = primary care physician; SDH = social determinants of health.

The general disregard for the value of preventive care is due to a mismatch between perceived benefit and the unaffordable level of effort required to access primary care. This problem worsens for our marginalized populations: both rural and low-income inner-city areas suffer from increased difficulty accessing primary care.7 Moreover, even in low-income inner-city areas where the ratios of patients and primary care physicians (PCPs) are comparable, social determinants of health (e.g., transportation and scheduling issues, lack of child care or paid sick time, Medicaid reimbursements that do not allow multiple doctors’ visits in one day) dictate true accessibility.

The system then reinforces itself: because health insurers devalue and underfund primary care, our too few, overencumbered PCPs overbook their schedules, creating longer waits for an appointment. Patients then wait further at the appointment, as the allotted one-size, 15-minute visit does not actually fit all. Their health problems are often unresolved, recognized too late, or met with further barriers of test and medication authorizations. The vicious cycle of waits and delays is reinforced, and patients’ trust in primary care erodes further without continuity and without faith that the PCP can actually help their complex needs.

Although divestments from primary care attempt to cope with overspending on medical procedures and tertiary care, the health care system still receives significantly more governmental funding than community-based organizations, which are better suited to address social determinants of health, the fundamental causes of much illness. When pediatricians see children failing to thrive because of inadequate nutrition, hunger becomes a health care problem, and as long as the solutions to social problems require health care providers to intervene, the problems of long patient waits and overburdened PCPs continue. In this way, primary care for marginalized populations is made much harder to deliver. Thus, inequities in health care and social determinants of health grow.

DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT OF COVID-19

As of October 10, 2020, the United States accounted for 21% of the world’s COVID-19 cases and 20% of the world’s COVID-19 deaths,1 despite accounting for only 4% of the world population. With no effort toward swift containment and severe inadequacies in testing and personal protective equipment, the United States missed the mark for containment by the time New York became the epicenter. Tried and true epidemiological methods (isolation of infected individuals, quarantine of contacts, and contact tracing) have not been effective. Moreover, evidence-based prevention measures (universal mask wearing, use of personal protective equipment, physical distancing, and hand hygiene) continue to encounter significant resistance.

Black and Latinx Americans are consistently overrepresented among COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths,8 and Black and Latinx patients hospitalized with COVID-19 present with more comorbidities—specifically obesity, hypertension, and heart disease9—greatly increasing the risk for COVID-19 fatality. The pandemic also highlights the disproportionate economic burden on people of color, especially in states that have rejected Medicaid expansion.10 People in marginalized racial/ethnic groups are overrepresented in racially and economically segregated communities with substandard housing conditions, unsafe or limited water, and crowded housing, all factors that make public health prevention measures extremely difficult if not impossible.2,5,11

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York, officials did not turn to primary care because our contingency plans for emergencies include only emergency rooms. PCPs were ill equipped to deal with a pandemic filled with conflicting information and a health care system in disarray. Health insurers quickly approved full payments for televisits and waived Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements so that PCPs and patients could communicate over nonmedical platforms. Although PCPs quickly adopted new systems for televisits, many patients were still left out as a result of technology gaps, scheduling issues, or lack of awareness about teleservices.

A different system design may have allowed PCPs to respond more quickly and to a broader population at a vulnerable moment. In this particular pandemic, an initial myopic focus on hospitalized patients prevented outpatient health care providers from early participation in basic COVID-19 education and close monitoring of individuals at high risk of both exposure and fatality. A lack of understanding of the asymptomatic state and contagion contributed to patients’ fears of seeing their PCP and other outpatient specialists (e.g., cardiologists, oncologists, psychiatrists), which led to more disenfranchised, disengaged patients with worsening health.

During the peak of the pandemic, about 41% of US adults avoided medical care because of COVID-19 concerns.12 New York City had the highest level of deferral of health care services, a peak reduction of 70%.13 The highest rates of deferred medical care were found among Black and Latinx adults, people with disabilities, and those with two or more underlying conditions.12 In a comparison of January through April 2019 and 2020, vaccine tracking systems reveal a significant decrease in childhood vaccinations beginning the week after March 16, 2020.14 Average weekly screenings for breast, colon, and cervical cancers dropped by 94%, 86%, and 94%, respectively, relative to the averages before January 2020.15 Combined diagnoses for breast, colorectal, lung, pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal cancers during the peak of the pandemic fell by 47%. These delays in diagnosis will likely lead to presentation at later stages and more fatal outcomes.16

To date, the largest drops in health service spending over 2019 have been in outpatient care centers,15 where patients are both screened and treated for diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, heart disease, and asthma. During the pandemic, there have been reductions in care for these conditions ranging from 7% to 38%.17 Delaying screenings and treatment of chronic disease patients can lead to increased complications, which often require critical care management and are associated with significant health care costs, morbidity, and mortality.18 , 19 This deferred care has resulted in excess deaths relative to prior years (a “death gap”) beyond those directly caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection: from March 1 to April 25, 2020, the United States had more than 87 000 excess deaths, of which only about 65% were attributed to COVID-19.20

In addition, with SARS-CoV-2 infection, we are seeing that many recovering patients have chronic cough, fibrotic lung disease, and bronchiectasis.21 Activating primary care would mean reaching out to patients for routine disease screening and treatment instead of hoping they remember to come in (or prioritize doing so) and ensuring that primary care is accessible to patients with persistent postinfection respiratory symptoms.

POST–COVID-19: REIMAGINING OUR CARE

The term “community-driven care ecosystem” describes a team-based health care model that includes primary care, care navigators and other lay workers, home health aides and family members, hospitals, postacute care, social and human service providers, accountable care organizations, and managed care organizations—based in and owned by the community—working in a concerted and coordinated manner to promote the physical, mental, and social well-being of the whole person. In most primary care models, a medical team led by the PCP drives care, expects the patient to respond, and is largely separate from community-level support. In a community-driven care ecosystem, patients drive their care toward self-management, and community-based sources of support join the PCP to meet patients where they are.

In the past decade or so, there have been promising practices in terms of care bundles and value-based payments in partnership with payers at either the individual practice or the municipality level.22 In addition, larger scale state-level reform endeavors for Medicaid populations, including in New York, have renewed attention to primary care, integrating primary care and behavioral health and prioritizing social issues confronting patients. New York State funded coordinated networks, reflecting the belief that delivery system reform will occur only if hospitals and clinical providers work together with community-based partners to change care delivery. The funding algorithm rewarded networks for breaking barriers to collaborating and contracting with community-based providers serving large numbers of Medicaid beneficiaries, which necessitated that clinical and social service providers build new partnerships with one another and find ways to strengthen joint efforts. These networks are one form of an ecosystem. Next, we expand on two critical tenets of the community-based care ecosystem.

Team-Based Care

The primary care system in New York City is already well positioned to respond to future pandemics: PCPs now test their patients for SARS-CoV-2 and are active in COVID-19 education. But the burdens are too great for the current fractured and siloed system to bear; it is unrealistic to expect medical providers to attempt to implement universal testing, care for COVID-19 patients, and reach out to care-deferring patients while responding to patients’ food insecurity. Successful examples of community-based care models must be deployed to stretch the care team beyond the medical model. One example involves PCPs alerting community health workers of cases of uncontrolled asthma among their patients. The community health workers then visit the patients’ homes—in person or, now, virtually—to ensure they understand how to use their inhalers and peak flow meters and evaluate their homes for evidence of roach and rodent infestation (known asthma triggers).

When the major receiver of funds is the hospital, the hospital remains the power broker for health care. Health care payers such as Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial insurers should contract directly with community-based service organizations, rather than hospitals and large clinical practices only, to transfer power and thereby elevate their capacity. If our goal is to increase preventive care and promote self-management, we need to elevate community-based preventive care and testing and a community-driven care continuum for chronic disease. Then ambulatory care can partner with community-based organizations to deliver care to people where they are. This requires workforce development and training to make primary care emergency ready. Moreover, it requires paid sick leave and other appropriate benefits for all members of the workforce and complete compensation and reimbursement for all care, face to face or otherwise.

Telemedicine and Technology

Health care must overcome its inertia and continue to nimbly adopt innovative approaches to improving equitable care. For example, telemedicine had been blocked for years by regulatory barriers until those barriers “magically” disappeared: the number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving telehealth services nationwide, including audio-only visits, virtual check-ins, and video visits, increased from 13 000 per week before the pandemic to almost 1.7 million in the last week of April 2020.23 New York City Health + Hospital’s 500 monthly televisits increased to 57 000 within three weeks of the outbreak.24 Despite uncertainties about payment models, many PCPs are maintaining their telehealth appointments to better respond to the next wave.

Moreover, basic technology and infrastructure have allowed for teleservices beyond billable telemedicine. Services range from tele-education and virtual visits with asthmatic clients and patients with uncontrolled diabetes to remote release planners for soon-to-be-decarcerated individuals to provide substance use support and video assessments and telephonic shelter intakes for homeless individuals. Community-based organizations have seen a noticeable rise in engagement with their clients, including hard-to-reach and previous unreached clients. These virtual means also allow staff members to stay safely employed, with more uninterrupted focus on their clients.

Still, enabling these services equitably will require powerful level setting. We must break the digital divide by providing devices and broadband connections to patients who lack them and culturally responsive education toward virtual and digital health care access.

CONCLUSIONS

What does our society’s post–COVID-19 era look like? Data show that since the beginning of the outbreak in New York (March 2020), about 80% of all COVID-19 patients have not been hospitalized, and about 95% have not required a ventilator and have not died.25 This means that well over 90% of COVID-19 patients have recovered in the community and emphasizes the paramount need to invest in community-based, person-centered, person-driven care. Data on non–COVID-19 fatalities and deferred care warn us to act now to prevent another wave of health care crises. Currently, our system is driven by hospital-based health care, a semiprivatized economy feeding on structural inequity and inequitable distribution of consumer technology. We must take this opportunity to examine our current unbalanced, inequitable public health and health care system and build and bolster a community-based care structure in a holistic, humane, and equitable way.

COVID-19 is not spreading over a level playing field, nor do affected individuals recover and sustain equitably. By highlighting the most vulnerable spots in our community, the pandemic underscores new opportunities for longer-term preparation to prevent further deepening of health inequities. Some of these “new” opportunities are not actually new but have seen chronic underinvestment. Our marginalized communities have not observed meaningful investment in their health and well-being. This pandemic may be due to a novel virus, but curtailing the prolonged human-made disaster of inadequately addressing our marginalized communities’ needs is in our control. As much as primary care is part of and suffers from structural inequity, it can also be part of the effort to break down such structures and contribute to population wellness in the post–COVID-19 era.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering. COVID-19 dashboard, global map. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bailey ZD, Moon JR. Racism and the political economy of COVID-19: will we continue to resurrect the past? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(6):937–950. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8641481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, Shah A, Doty MM. Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better US Health Care. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard T, Paradis R, Bauer A, Hung P. Healthy People/Healthy Economy: An Initiative to Make Massachusetts the National Leader in Health and Wellness. Boston, MA: Boston Foundation and Network for Excellence in Health Innovation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashman J, Rui P, Okeyode T. Characteristics of office-based physician visits. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db331.htm [PubMed]

- 7.Kerns C, Wills D. The problem with US health care isn’t a shortage of doctors. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/03/the-problem-with-u-s-health-care-isnt-a-shortage-of-doctors

- 8.American Public Media The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the US. https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race

- 9.Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an urban medical center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019795. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann C. The COVID-19 crisis is giving states that haven’t expanded Medicaid new reasons to reconsider. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/covid-19-crisis-giving-states-havent-expanded-medicaid-new-reconsideration

- 11.Bailey ZD, Barber S, Robinson W, Slaughter-Acey J, Ford C, Sealy-Jefferson S. Racism in the time of COVID-19. https://iaphs.org/racism-in-the-time-of-covid-19

- 12.Czeisler ME, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19–Related Concerns—United States, June 2020. Vol. 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall RD. COVID-19 Return Stages: Deferral and Restarting of Health Care Services. Schumburg, IL: Society of Actuaries; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration—United States, 2020. Vol. 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox C, Amin K. How have health spending and utilization changed during the coronavirus pandemic? https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-have-healthcare-utilization-and-spending-changed-so-far-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/#item-costs-use-covid_change-in-average-weekly-cancer-screening-volume-jan-1-2017-jan-19-2020-vs-jan-20-apr-21-2020-by-type-of-screening

- 16.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2017267. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Ness-Otunnu R, Hack JB. Hyperglycemic crisis. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):797–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of California: San Francisco. Kidney Project; https://pharm.ucsf.edu/kidney/need/statistics#:∼:text=Hemodialysis%20care%20costs%20the%20Medicare,patient%20care%20is%20%243.4%20billion [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March–April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(5):510–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser E. Long term respiratory complications of COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evolent Health Value-based care news digest. May 2019. https://knowledge.evolenthealth.com/blog/value-based-care-news-digest-may-2019

- 23.Verma S. Early impact of CMS expansion of Medicare telehealth during COVID-19. 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200715.454789/full

- 24.NYC Health + Hospitals NYC Health + Hospitals announces success of telehealth expansion to address COVID-19 pandemic managing nearly 57,000 televisits during peak. https://www.nychealthandhospitals.org/pressrelease/system-announces-success-of-telehealth-expansion-during-covid-19-pandemic/#∼:text=The%20City's%20public%20health%20system,over%20235%2C000%20televisits%20to%2Ddate

- 25.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]