At the time of writing, the United States remains the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic with mass vaccination efforts still months away from completion. Unsurprisingly, the spread of COVID-19, an infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is not distributed equally. Legacies of structural racism and violence, specifically within settler colonial contexts, continue to manifest in contemporary examples of social and economic disparity for Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color populations. American Indian populations, in both rural and urban locales, face exceptional public health challenges. These inadequacies deprive American Indians of fundamental human rights including access to quality health care, clean water, and adequate living conditions.

Analyzing the impacts of COVID-19 on the Navajo Nation offers an important case study for examining the settler colonial origins of health inequities laid bare by COVID-19. Rather than viewing these conditions solely on the basis of racial inequality,1 we contend that histories of settler colonialism (e.g., dispossession of Indigenous lands, forced assimilation into Indian boarding schools, and the disproportionate burden of toxic exposure from resource extraction2) are crucial to understanding the impact of the current COVID-19 health crisis in tribal nations today.3 In this commentary, we present an overview of broader social and historical factors for understanding public health disparity in Diné (Navajo) communities, the role that Diné-centered knowledge has and continues to play in efforts to confront infectious disease, and how we can imagine new approaches to Indigenous-framed public health interventions.

DIK’OS NTSAAÍGÍÍ-19 (COVID-19) ON THE NAVAJO NATION

The first confirmed case of Dik’os Ntsaaígíí-19 (literal translation in the Diné language is “big cough-19”) on the Navajo Nation was on March 17, 2020, and was linked to a large church gathering held in the Diné community of Chilchinbeto, Arizona.4 From that point forward, the disease began to quickly spread to other Diné communities. Within a couple of months, the Navajo Nation would become a pandemic hotspot—far surpassing per-capita infection rates of more populated areas such as New York and New Jersey.5

At a time when understanding infection vectors was still uncertain and a coordinated national public health response was lacking, the Navajo Nation instituted its own infection control measures such as stay-at-home orders, weekend lockdowns, and provisions for local business operation.6 The Navajo Nation emergency response was officially activated on February 25, 2020, before any confirmed cases on the reservation.7

Despite these precautionary measures, American Indian and Alaska Native persons are 1.9 times more likely to contract COVID-19, 3.7 times more likely to be hospitalized because of COVID-19, and 2.4 times more likely to die from COVID-19 complications compared with non-Hispanic White persons.8 We have palpably felt the reality of these statistics in our Diné communities, families, and extended kin networks. Furthermore, we contend that such high rates of hospitalization and death are not fully accounted for within existing social determinants of health alone. According to the most recent census, the total population of tribal members residing on the Navajo Nation is 173 667.9 As of early February 2021, there were a total of 29 386 (16.9%) confirmed cases across the Navajo Nation, reaching the highest daily positive count of 400 on November 21, 2020. In total, 1127 (0.6%) Diné tribal members have died from COVID-19.10 In addition, the burden of COVID-19 is likely underestimated because of inadequate testing and discrepancies of data sharing across overlapping tribal and state jurisdictions in addition to the miscounting of Diné tribal members who reside in off-reservation border towns. The total counts reported may seem minor relative to more dense urban areas; however, these proportional data reveal a starker picture about the severity of this disease for Diné communities. Though public health control measures may have helped keep cases lower, they can only do so much to mitigate the ongoing outbreak in light of a longer history of settler colonial violence and structural racism.

SETTLER COLONIAL VIOLENCE AND HEALTH IMPACTS TODAY

The incursion of American settlers into Diné Bikéyah, the name of our original ancestral homelands, began in the 1850s with military expeditions, land surveys, and the establishment of trading posts. In 1863, Lt. Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson began a violent scorched earth campaign by burning dwellings, slaughtering livestock, and poisoning water sources as the US military sought to seize Diné territory. During this process, more than 10 000 Diné were forcibly marched hundreds of miles to a concentration camp in New Mexico in an act of attempted genocide now known as The Long Walk.11 At Fort Sumner, Diné prisoners of war were forced to adopt Christianity, English language and education, the Euro-American cultural value of individualism, and a foreign diet of commodity foods such as flour, lard, and coffee. During their internment, one in every four Diné died because of deprivation, starvation, and disease. Following what the military determined to be a failed experiment, the signing of the Treaty of 1868 ended their incarceration and allowed surviving Diné to return to their homelands, albeit to a drastically reduced land base that was established as the Navajo Reservation. The historical context of settler colonial violence is necessary and crucial for understanding health and economic disparity on the Navajo Nation today.

Specifically, present-day inequity in socioeconomic position, food, and water security on the Navajo Nation underscores the impact of settler colonialism. Compared with the United States, the Navajo Nation population has lower education (25% vs 12% less than a high-school education) and annual household income (23% vs 6% less than $10 000), and greater unemployment (56% vs 6%) and poverty (36% vs 12%).12 Furthermore, the Navajo Nation only has 13 grocery stores, which serve the 27 000-square-mile area roughly equivalent to the area of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont combined.13 Moreover, water insecurity remains a prominent problem in a region drastically affected by human-driven climate change, the perpetuation of colonial era laws that prioritize settler claims to water over tribal sovereignty, and the ongoing toxic contamination of water sources from decades of resource extraction.14 According to recent estimates, more than 40% of Diné tribal members lack running water in their households and must rely on hauling water for household consumption.15 While the average American uses 88 gallons of water per day, most Diné use fewer than 10 gallons per day.16 A comparative study of water access on tribal nations found a higher incidence of COVID-19 infection rates in households that lack indoor plumbing.17 Therefore, water insecurity is directly related to health disparities that are further exacerbated during this pandemic.

Access to reliable health care remains a challenge for Navajo and other tribal nations. The Indian Health Service, operated by the US Department of Health and Human Services, provides health care to the 574 federally recognized Native American Tribes and Alaska Native people throughout the country. As of 2017, it has an annual operating budget of $5.9 billion to fund 26 hospitals, 59 health centers, and 32 health stations. Out of this total, the Navajo Area Indian Health Service—composed of seven tribally run service units, five Indian Health Service‒run units, and one urban health center in Flagstaff, Arizona—delivers health services to a population of more than 244 000 Diné across the reservation and beyond.18 Yet, the delivery of care is fragmented and limited because of severe underfunding. Under conditions of COVID-19, every hospital bed and ventilator is a precious and limited resource. On the Navajo Nation, across all service units, there are only 259 hospital beds, 26 ICU beds, 58 negative-pressure rooms, 74 ventilators, 313 nurses, and 285 providers (Jill Jim, online presentation at the Emerging Infection and Tribal Communities virtual conference, February 19, 2021).

During periods of heightened rates of infection, the number of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization often exceeded available resources. During a recent visit at Tséhootsooí Medical Center accompanying her elder relative to an appointment, coauthor T. M. heard a particularly emotional narrative from a doctor who described how at one point patients needed to be airlifted off the reservation “almost every hour.” The hospital simply did not have enough beds to accommodate all of the oxygen-compromised patients. He described the horror of witnessing those who “couldn’t breathe” and how several “didn’t make it.” As we have seen in numerous other hospitals across the country through news and social media, these stories are not isolated. The psychological burden of this contemporary moment also conjures memories of previous traumas and previous pandemics.

LESSONS FROM THE 1918 FLU

After we had moved away from the Place of the Reeds and resettled ourselves for the winter, for a long time whenever my father talked to the People, he’d talk about that terrible sickness and how it had spread so fast and killed so many of the People all over the reservation. He tried to use consoling words in his talks, and he used his big loud voice, so everybody could hear what he was saying. He talked about those things to all of us here in the family, too, almost every day, for a long time after that. He kept saying we should learn from what happened during that time. That showed nobody ever really knows the things that are going to come their way as they move along with their lives. He said we needed to learn life could be hard, that hardships and suffering were part of what we would experience while we were living. And he kept telling us we needed to be prepared for whatever was coming our way.19

This excerpt is an English translation of an oral history story told in the Diné language by Rose Mitchell to anthropologist Charlotte Frisbie.19 Born in 1874, Mitchell narrates her memories of a great sickness that caused many Diné to perish. This illness has been called many names such as Ts’ii nidooh da iighã’yęę daa, meaning, roughly, “during the time the flu killed.” In English, it was known as the Spanish Flu, though its association with Spain is a misnomer as there is no consensus as to where it first spread to humans. What is known is that between 1918 and 1919 it infected more than 500 million people worldwide, approximately one third of the world’s population at the time, and killed an estimated 50 million people.20

Accounts of the illness in Diné communities, recorded by missionaries, anthropologists, and Indian Agents,21,22 identified risk factors for mortality including age and gender, socioeconomic status, the availability of resources, immunity related to health status and previous disease experience, social distancing, and community organization and communication infrastructure.23 It is not surprising that communities that successfully quarantined and who had greater access to food and health care fared better.

Several historic accounts analyzed Diné cultural norms as a medical liability, such as the common practice of intergenerational living in a single-room hogan (traditional Diné dwelling) or the use of traditional Diné medicine to treat symptoms of influenza.21 However, describing greater mortality rates as a consequence of the failed incorporation of Western medicine discounts the crucial role that Diné ontologies of k’é—an ethic of relational care and kinship with human and nonhuman beings—can play in confronting trauma and crisis, both historically and today. Therefore, current analyses of COVID-19 on the Navajo Nation must not fall into a common trap of recycling deficit narratives that frame cultural knowledge as an impediment to Western health care measures. In fact, successful contemporary approaches to health care in the Navajo Nation incorporate both Western medicine and Diné knowledge. Consider, for example, the Navajo Epidemiology Center, whose mandate is to “empower Diné People to achieve Hózhó (harmony) through naalniih naalkaah.”24 This italicized phrase in the Diné language is used to describe epidemiology as disease surveillance. This is but one example of how Diné communities and Navajo tribal health programs are incorporating Diné language and knowledge into culturally appropriate public health interventions (see also Image A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

INDIGENOUS FRAMEWORKS OF RELATIONAL CARE

Centuries of settler colonial ideologies and practice have led to deteriorated well-being and environmental destruction through attempts to replace Diné language, lifeways, and ceremonial practice. Nevertheless, we draw attention to the ways that Diné knowledge based on kinship and relationality has persisted through community-based systems of care to confront these enduring social and health inequities.

Recent grassroots mutual aid efforts guided through the Diné relational ethic of k’é have formed in response to COVID-19 on the Navajo Nation. For example, the Navajo and Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund, led by nine Diné women, was initially established in March 2020 via crowdfunding to provide Diné and Hopi families with food, personal protective equipment, and supplies to help them safely self-quarantine. As of February 2021, the group has supported more than 30 000 households on the Navajo Nation and Hopi Villages. Similar practices of relational care are at the heart of Indigenous grassroots relief efforts and mutual aid organizing.

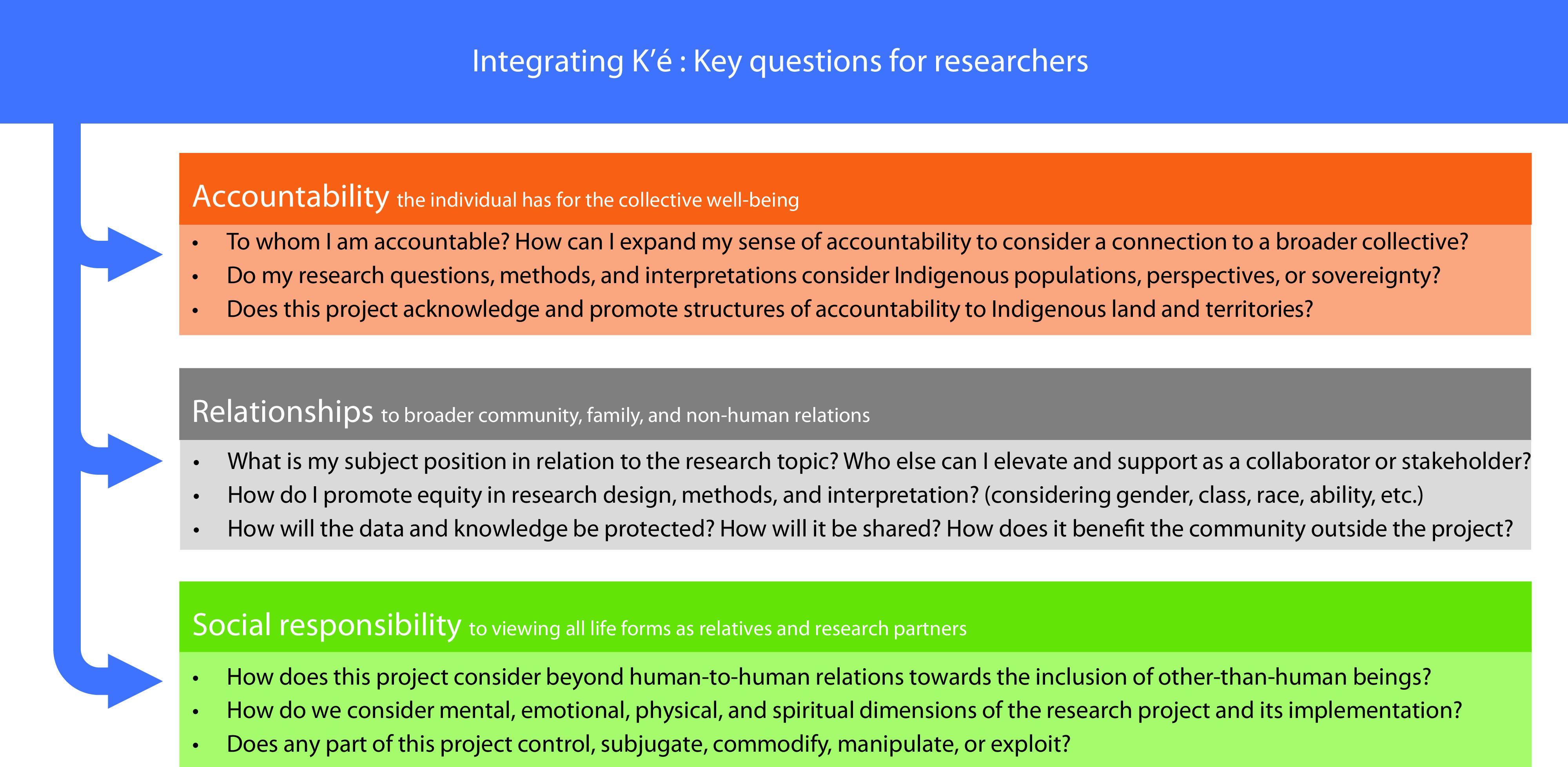

To provide readers with actionable suggestions for integrating a relational approach to research, we share a framework of Diné-oriented guidelines (Figure 1 and see recommended reading list in materials available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) for potential application in considerations of health policy, environmental stewardship, and disaster preparation. This relational approach to research based on traditional Diné knowledge begins with an introduction to k’é, a philosophy of being that integrates kinship, responsibility, inclusivity, unity, compassion, and cyclical life. This Diné concept considers relationships to broader community, family, and nonhuman relations. In addition, it considers the accountability the individual has for the collective well-being and views all life forms as relatives and research partners. Identifying self in the research process gives clarity to questions, methods for knowledge gathering, and interpretation of data. Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars alike can learn from frameworks that prioritize Indigenous relational approaches to our health and environment. Relying exclusively on Western epistemologies and methods often will result in interpretations entangled with hierarchical frameworks that continue to uphold notions of individualism, secularism, positivism, patriarchy, and fragmented, rather than holistic, understandings of self and kin relations. Diné relational philosophy, like many other kinship-based Indigenous knowledge systems, is an expression of interdependent ontology that guides how and for whom our work is made meaningful. This approach can radically transform how we understand health, environmental, and social justice issues as intrinsically interrelated.

FIGURE 1—

A Relational Approach to Research Based on the Diné (Navajo) Concept of k’é, a Philosophy of Being That Integrates Kinship Relations, Social Responsibility, Inclusivity, Unity, Compassion, and Cyclical and Perennial Life

In conclusion, analyzing contemporary public health and environmental contamination issues as part of a longer trajectory of colonial violence is necessary to creating appropriate and useful responses to infectious disease. Racial determinants alone do not adequately describe health inequities in Indigenous contexts. Furthermore, we encourage inclusive participation of our public health colleagues who can benefit from learning and applying relational philosophies of care into their own research practice and pedagogy. In imagining the future of public health, we need to name, acknowledge, and understand the legacy of settler colonialism’s systemic impact in the context of COVID-19 as well as Indigenous framing of social determinants of health as a valid, sovereign, and useful means of interventive knowledge production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. A. Emerson acknowledges support from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, grant T32-CA057726. T. Montoya offers gratitude to Nicole Horseherder for assisting with Diné language translation and orthography. Lastly, we both acknowledge the legacy and teachings of the late Larry Emerson.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41(1):311–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover E, Cook K, Plain R, et al. Indigenous peoples of North America: environmental exposures and reproductive justice. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(12):1645–1649. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yellow Horse AJ, Yang T-C, Huyser KR. Structural inequalities established the architecture for COVID-19 pandemic among Native Americans in Arizona: a geographically weighted regression perspective. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00940-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen K. Virus strikes at rally: Chilchinbeto church gathering may be source of outbreak Navajo Times. March 22, 2020https://navajotimes.com/coronavirus-updates/two-deaths-in-western-may-have-been-covid-virus-spread-at-church-rally

- 5.Silverman H, Toropin K, Sidner S, Perrot L. Navajo Nation surpasses New York State for the highest Covid-19 infection rate in the US. CNN. May 18, 2020https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/18/us/navajo-nation-infection-rate-trnd/index.html

- 6.Navajo Department of Health. 2020. https://www.navajo-nsn.gov/News%20Releases/NNDOH/2020/Nov/NDOH%20Public%20Health%20Emergency%20Order%202020-029%20Dikos%20Ntsaaigii-19.pdf

- 7.Becenti A. Dikos Ntsaaígíí dóódaa! Nation musters defense against COVID-19. Navajo Times. March 12, 2020https://navajotimes.com/reznews/dikos-ntsaaigii-doodaa-nation-musters-defense-against-covid-19

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/covid-data/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.pdf

- 9.The Navajo Nation Department of Health. 2013. https://www.nec.navajo-nsn.gov/Portals/0/Reports/NN2010PopulationProfile.pdf

- 10.The Navajo Nation Department of Health. 2021. https://www.ndoh.navajo-nsn.gov/COVID-19

- 11.The Smithsonian Institution. 2019. https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/navajo/long-walk/long-walk.cshtml

- 12.US Census Bureau. 2019. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html

- 13.Diné Policy Institute. 2014. https://www.dinecollege.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/dpi-food-sovereignty-report.pdf

- 14.Ingram JC, Jones L, Credo J, Rock T. Uranium and arsenic unregulated water issues on Navajo lands. J Vac Sci Technol A. 2020;38(3):031003. doi: 10.1116/1.5142283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deitz S, Meehan K. Plumbing poverty: mapping hot spots of racial and geographic inequality in US household water insecurity. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2019;109(4):1092–1109. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1530587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold A, Shakesprere J. 2020. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/four-ways-improve-water-access-navajo-nation-during-covid-19

- 17.Rodriguez-Lonebear D, Barceló NE, Akee R, Carroll SR. American Indian Reservations and COVID-19: correlates of early infection rates in the pandemic. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26(4):371–377. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Indian Health Service. https://www.ihs.gov/navajo

- 19.Frisbie CJ, editor. Tall Woman: The Life Story of Rose Mitchell, a Navajo Woman c. 1874‒1977. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/1918-pandemic-history.htm

- 21.Reagan AB. The “flu” among the Navajos. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903‒). 1919;30:131–138. doi: 10.2307/3624053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahr HM. The Navajo as Seen by the Franciscans, 1898‒1921: A Sourcebook. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamin RB, Howard MB. The influenza epidemic of 1918‒1920 among the Navajos: marginality, mortality, and the implications of some neglected eyewitness accounts. Am Indian Q. 2014;38(4):459–491. doi: 10.5250/amerindiquar.38.4.0459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navajo Epidemiology Center. https://www.nec.navajo-nsn.gov