Abstract

Capsular polysaccharides (CPSs) protect bacteria from host and environmental factors. Many bacteria can express different CPSs and these CPSs are phase variable. For example, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) is a prominent member of the human gut microbiome and expresses eight different capsular polysaccharides. Bacteria, including B. theta, have been shown to change their CPSs to adapt to various niches such as immune, bacteriophage, and antibiotic perturbations. However, there are limited tools to study CPSs and fundamental questions regarding phase variance, including if gut bacteria can express more than one capsule at the same time, remain unanswered. To better understand the roles of different CPSs, we generated a B. theta CPS1-specific antibody and a flow cytometry assay to detect CPS expression in individual bacteria in the gut microbiota. Using these novel tools, we report for the first time that bacteria can simultaneously express multiple CPSs. We also observed that nutrients such as glucose and salts had no effect on CPS expression. The ability to express multiple CPSs at the same time may provide bacteria with an adaptive advantage to thrive amid changing host and environmental conditions, especially in the intestine.

Keywords: capsular polysaccharide, microbiome, phase-variable

Introduction

Many bacteria express capsular polysaccharides (CPSs), which protect bacteria from host and environmental factors. CPSs have been found in a variety of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria as well as fungi and are critical for vaccine development and serological classification [1–4]. One interesting feature of CPSs is that they are phase variable, enabling bacteria to switch between different CPSs. This phase variance arises because CPS expression can be regulated by DNA inversions near the CPS biosynthesis loci with a reversible on-off phenotype [5–7], trans locus inhibitors [8, 9], slipped-strand mispairing [10], tandem sequence duplication [11], and NusG-like transcriptional antitermination factors [12]. This phase variance is thought to allow an individual cell to express one CPS locus, while enabling other cells in the population to explore expression of different capsules [8]. Such a strategy could improve bacterial fitness by enabling bacteria to express the most advantageous CPS in different environments [13–19].

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) is a Gram-negative anaerobe that is highly abundant in the human gut microbiota and degrades a variety of glycans from the diet, host mucous, and other microbes [20]. In addition, when TGF-β and IL-10 signalling is disrupted in mice, B. theta has been shown to cause colitis [21]. B. theta devotes a large portion of its genome to CPS production (182 genes in eight distinct genomic loci) and expresses eight CPSs (CPS1–CPS8), which can be several hundred nanometers thick [22]. B. theta is often used as a model gut symbiont to study CPSs because it is currently the only bacteria in which the roles of a complete set of capsules in a single species can be interrogated by individually expressing all eight capsules [23]. Previous work has shown that B. theta CPSs provide adaptive advantages by promoting increased competitive fitness [23], modulating immune responses to dominant antigens [24], and modifying bacteriophage susceptibility [25, 26].

Given the importance of CPSs in bacterial fitness, a longstanding fundamental question is whether bacteria can express multiple CPSs at the same time. Current tools to analyse CPS expression in the gut microbiota such as qPCR and ELISA are limited because they can only determine CPS expression in the entire bacterial population; they are unable to examine CPS expression in individual bacteria. CPS-specific antibodies are highly specific tools to detect CPS expression, but very few CPS-specific antibodies exist. For example, although B. theta has eight CPSs, only two B. theta CPS-specific antibodies against CPS3 [6] and CPS4 [27] currently exist. To deepen our understanding of the functions of CPSs, we generated a B. theta CPS1-specific antibody and developed a flow cytometry assay to detect CPS expression at the level of a single gut symbiont. Using these tools, we demonstrated for the first time that bacteria can simultaneously express multiple capsules, which is not affected by nutrients such as glucose and salt.

Methods

Generation of CPS-specific antibodies

The CPS1-specific antibody C73 was generated by immunizing C57BL/6 mice with killed CPS1 and boosted. Splenic B cells were then fused with P3Ag8.6.5.3 myeloma cells to create hybridomas [28]. The CPS3-specific antibody, 3H2, used in this study was previously generated and characterized [6]. The monoclonal antibodies C73 and 3H2 were fluorescently labelled with Alexa 647 and Alexa 750, respectively.

Growth of B. theta

The single CPS-expressing B. theta strains used in this study have been generated and characterized previously [23, 24]. B. theta strains were grown at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions in a BD GasPak EZ Small Incubation Chamber with BD GasPak EZ Anaerobe Container System Sachets with Indicator. B. theta strains were grown to mid-log phase in tryptone-yeast-extract-glucose (TYG) medium or modified TYG medium (mTYG). TYG medium (10 g l−1 tryptone, 5 g l−1 yeast extract, 4 g l−1 d-glucose, 100 mM KH2PO4, 8.5 mM [NH2]4SO4, 15 mM NaCl, 10 mM vitamin K3, 2.63 mM FeSO4·7H2O, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 1.9 mM hematin, 0.2 mM l-histidine, 3.69 nM vitamin B12, 413 mM l-cysteine, and 7.2 mM CaCl2·2H2O) and mTYG medium (20 g l−1 tryptone, 10 g l−1 yeast extract, 5 g l−1 d-glucose, 8.25 mM l-cysteine, 78 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 294 mM KH2PO4, 230 mM K2HPO4, 1.4 mM NaCl, 7.9 mM hemin [hematin], 4 mM resazurin, 24 mM NaHCO3, 68 mM CaCl2·2H2O) were prepared as described previously [29]. Cultures were washed once and resuspended in PBS prior to staining.

B. theta ELISA

B. theta cultures were grown to log phase. Immulon two plates were coated with poly l-lysine followed by fixed bacterial dilutions overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed, blocked, and incubated. The ELISA was developed with biotin-goat anti-mouse IgG, streptavidin peroxidase, and then 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA.

Sample preparation and flow cytometry

B. theta strains were stained with the Invitrogen LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability kit, C73 conjugated to Alexa 647, and 3H2 conjugated to Alexa 750 at 1 : 200 at room temperature protected from light for 20 min. Flow cytometry was performed with a BD FACS Canto.

Data analysis

FlowJo Software v10.7.1 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR) was used to analyse all flow cytometry experiments. Statistical analyses were performed in Prism Software v9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). P-values were determined using Student’s t-test.

Results

Generation of a CPS1-specific antibody and a flow cytometry assay that detects CPS expression in individual cells

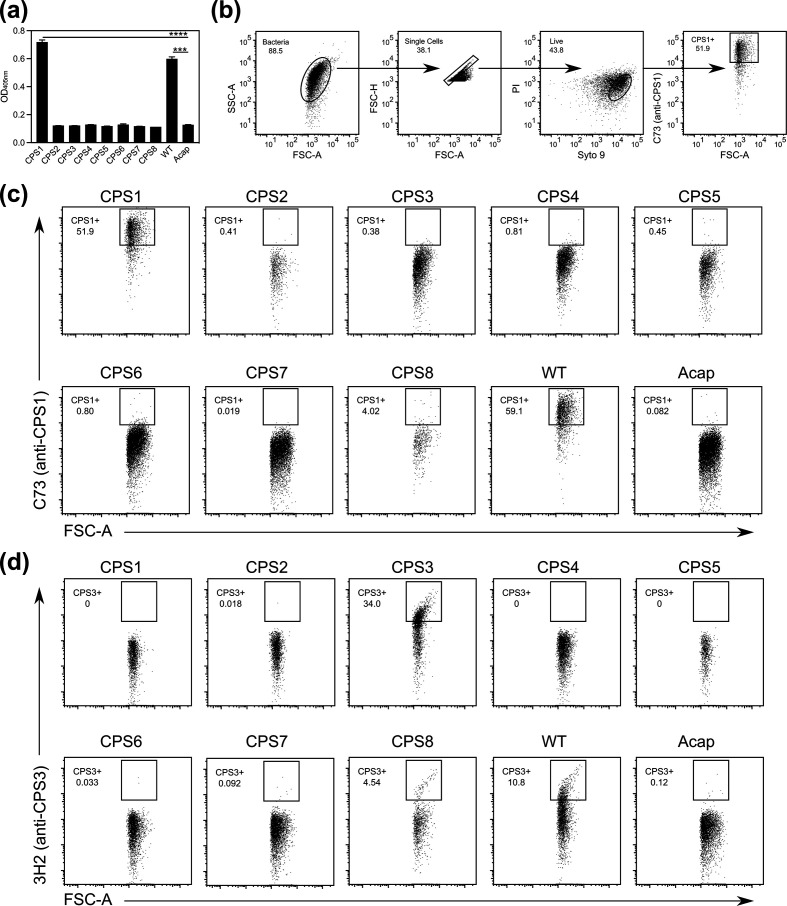

Recent evidence suggests that CPS1 has interesting immunoinhibitory properties because it evades activation of the innate and adaptive immune system [24]. To gain further insight into CPS1’s functions, we generated the only CPS1-specific antibody called C73 (Fig. 1a). Since a previous study demonstrated that flow cytometry can be used to identify the expression of individual CPSs in Neisseria meningitidis [30], we examined if we could use flow cytometry to detect CPS expression in individual bacteria in the gut microbiota. We directly conjugated C73 to Alexa 647 and found that C73 could detect CPS1 expression by flow cytometry in pure B. theta cultures (Fig. 1b). We then used flow cytometry to screen C73 against a complete set of eight single CPS–expressing B. theta strains, wild-type (WT), and acapsular (Acap) B. theta, which lacks all B. theta CPSs. Thus, we used our novel CPS1 antibody and flow cytometry assay to demonstrate that C73 also bound to WT, indicating that WT expresses CPS1 (Fig. 1c). CPS2-8 and Acap do not express CPS1 and did not bind to C73, illustrating that C73 can specifically detect CPS1 expression in B. theta by flow cytometry (Fig. 1c). Our lab has previously generated an antibody that is specific for CPS3 called 3H2 [6]. We showed that 3H2 could also be used to identify CPS3 expression by flow cytometry (Fig. 1d). These results demonstrate that this flow cytometry assay can be used to specifically detect CPS expression in single cells in the gut microbiota. Of note, C73 and 3H2 slightly bound to CPS8 by flow cytometry (~4 %), though fewer events were captured. This suggests that CPS1, CPS3, and CPS8 may share common sugars or polysaccharides with similar epitopes or CPS8 could bind to IgG with low affinity. Thus, we generated the only CPS1-specific antibody, C73, and developed a flow cytometry assay to characterize the CPSs expressed by individual gut bacteria, which may enhance our understanding of the roles of CPSs.

Fig. 1.

C73 and 3H2 are CPS1 and CPS3-specific antibodies, respectively, and can detect CPS expression in single cells in the gut microbiota by flow cytometry. (a) The amount of C73 that bound to CPS1-8, wild-type (WT), and acapsular (Acap) Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) was quantified via ELISA. The data is presented as mean±SD (n=2). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test. CPS2-8 are significantly different from CPS1 and WT (P <0.0001); other significant differences are indicated by asterisks (***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001). (b) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating schema. (c, d) Flow cytometry of bacterial cultures were used to determine the amount of (c) C73 or (d) 3H2 that bound to CPS1-8, WT, and Acap B. theta. Numbers indicate the percent of live cells in the indicated gates (n=2).

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron simultaneously expresses two CPSs, CPS1 and CPS3, which is not affected by glucose or salt

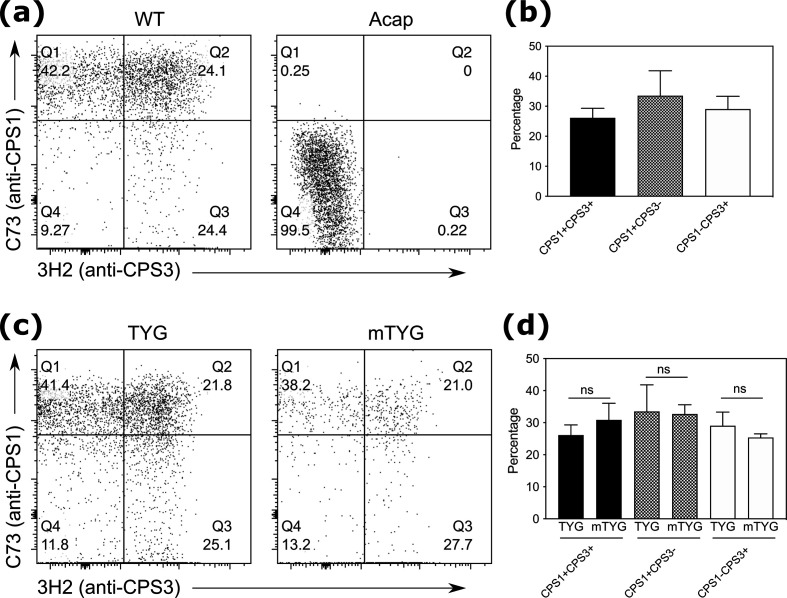

Bacteria have been shown to switch expression of phase variable CPSs to adapt to different niches [23]. Yet it remains unknown if bacteria can concurrently express multiple capsules. To interrogate if bacteria can express more than one capsule at the same time, we performed flow cytometry of WT B. theta with the C73 and 3H2 antibodies and found that B. theta can express both CPS1 and CPS3 in the same cell (Fig. 2a). These results demonstrate for the first time that bacteria can simultaneously express multiple capsules. This ability to express different capsules at the same time likely promotes bacterial fitness by enabling bacteria to rapidly acclimate to different conditions and thrive in a broader range of environments.

Fig. 2.

B. theta simultaneously expresses CPS1 and CPS3, which is not affected by glucose or salt. (a) Representative flow cytometry plots of C73+ and/or 3H2+ cells in WT or Acap B. theta cultures. Numbers indicate the percent of cells in the indicated gates. (b) Percentage of WT B. theta cells that express CPS1, CPS3, or both CPS1 and CPS3 (n=3). (c) Representative flow cytometry plots of C73+ and/or 3H2+ cells in WT B. theta cultures grown in tryptone-yeast-extract-glucose (TYG) medium or modified TYG medium (mTYG) media. Numbers indicate the percent of cells in the indicated gates. (d) Percentage of WT B. theta cells grown in TYG or mTYG media that express CPS1, CPS3, or both CPS1 and CPS3 (n=3). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test.

The factors that drive CPS expression remain poorly understood, but previous studies have shown that there may be a link between dietary nutrients and CPS expression [9, 17, 31–36]. In addition, a study demonstrated that many Bacteroides fragilis CPSs can incorporate exogenous fucose through a complementary glycosyl transferase [37]. All of our CPS studies so far had been performed by growing B. theta in tryptone-yeast-glucose (TYG) media. Another media called modified TYG (mTYG) media has been shown to contain significant differences in glucose and salts compared to TYG media that affect protein expression and immunogenicity of B. theta [29]. We grew WT B. theta in TYG versus mTYG media and found that there were no differences in CPS1 and CPS3 expression in B. theta (Fig. 2b). WT B. theta grown in mTYG media without glucose or mTYG media with TYG salts also showed no differences in CPS1 and CPS3 expression (results not shown). Together, these data suggest that glucose and salt do not regulate expression of CPSs.

CPSs are diverse structures that promote bacterial survival by providing critical protection against environmental and host factors, but the roles of CPSs remain poorly understood. One challenge in ascertaining CPS functions is the limited availability of tools to study CPS expression. Here, we generated two novel tools to study CPSs: a B. theta-specific CPS1 antibody and a flow cytometry assay to identify CPS expression in individual cells in the gut microbiota. Using these tools, we answered a fundamental question in the CPS field by demonstrating that individual bacteria can simultaneously express multiple CPSs. We also showed that glucose and salts do not affect CPS expression. These findings suggest that CPS diversity is not limited to single CPSs expressed by each cell; rather, the potential diversity of CPS coating in gut Bacteroides is exponentially expanded by combinatorial CPS expression. Future studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which multiple CPSs are co-expressed, such as a mixture of separate polysaccharide molecules on the cell surface or hybrid polysaccharide structures, as well as how CPSs are organized on the cell surface. Furthermore, this CPS diversity greatly increases the possibilities of antigenic variation, especially if varying amounts of individual CPSs or more than two CPSs are involved, and novel CPS roles likely remain to be discovered. Whether the simultaneous expression of multiple capsules that we observe in B. theta is a general phenomenon in gut bacteria remains to be elucidated. Identifying other factors that drive CPS expression may also provide further insight into the functional roles of CPSs.

Funding information

This work was supported by NIH grants F30DK114950 (to S.A.H.) and R21AI142257 (to P.M.A).

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Porter and E. Martens for the single capsule-expressing B. theta strains. We thank C. Hsieh, E. Unanue, and the Pathology Flow Cytometry Core for assistance and use of the flow cytometer.

Author contributions

S.A.H., designed and performed the experiments and wrote the paper. D.L.D., generated the antibodies. S.C.H., assisted with the bacterial cultures. P.M.A., guided the overall project design and assisted in writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

All animal work was approved by the Washington University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Acap, acapsular; B. theta, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron; CPS, capsular polysaccharide; WT, wild-type.

References

- 1.Hsieh SA, Allen PM. Immunomodulatory roles of polysaccharide capsules in the intestine. Front Immunol. 2020;11:690. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter NT, Martens EC. The critical roles of polysaccharides in gut microbial ecology and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:349–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carboni F, Adamo R. Structure-based glycoconjugate vaccine design: The example of Group B streptococcus type III capsular polysaccharide. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2020;35–36:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makela PH. Capsular polysaccharide vaccines today. Infection. 1984;12:S72–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01641750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyne MJ, Weinacht KG, Krinos CM, Comstock LE. Mpi recombinase globally modulates the surface architecture of a human commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10446–10451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832655100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey CA, Kuhn KA, Donermeyer DL, Porter NT, Jin C, et al. Colitogenic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron antigens access host immune cells in a sulfatase-dependent manner via outer membrane vesicles. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Zhang JR. Phase Variation of Streptococcus pneumoniae . Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0005-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Weinacht KG, Comstock LE. Trans locus inhibitors limit concomitant polysaccharide synthesis in the human gut symbiont Bacteroides fragilis . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11976–11980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005039107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martens EC, Roth R, Heuser JE, Gordon JI. Coordinate regulation of glycan degradation and polysaccharide capsule biosynthesis by a prominent human gut symbiont. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18445–18457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammerschmidt S, Muller A, Sillmann H, Muhlenhoff M, Borrow R, et al. Capsule phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B by slipped-strand mispairing in the polysialyltransferase gene (siaD): correlation with bacterial invasion and the outbreak of meningococcal disease. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1211–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waite RD, Penfold DW, Struthers JK, Dowson CG. Spontaneous sequence duplications within capsule genes cap8E and tts control phase variation in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 8 and 37. Microbiology (Reading) 2003;149:497–504. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Coyne MJ, Comstock LE. A family of transcriptional antitermination factors necessary for synthesis of the capsular polysaccharides of Bacteroides fragilis . J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7288–7295. doi: 10.1128/JB.00500-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava M, Tucker MS, Gulig PA, Wright AC. Phase variation, capsular polysaccharide, pilus and flagella contribute to uptake of vibrio vulnificus by the eastern oyster (crassostrea virginica . Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1934–1944. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holst Sorensen MC, van Alphen LB, Fodor C, Crowley SM, Christensen BB, et al. Phase variable expression of capsular polysaccharide modifications allows Campylobacter jejuni to avoid bacteriophage infection in chickens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AC, Powell JL, Tanner MK, Ensor LA, Karpas AB, et al. Differential expression of Vibrio vulnificus capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2250–2257. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.5.2250-2257.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright AC, Powell JL, Kaper JB, Morris JG. Identification of a group 1-like capsular polysaccharide operon for Vibrio vulnificus . Infect Immun. 2001;69:6893–6901. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6893-6901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrison-Schilling KL, Grau BL, McCarter KS, Olivier BJ, Comeaux NE, et al. Calcium promotes exopolysaccharide phase variation and biofilm formation of the resulting phase variants in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus . Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:643–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernebro J, Andersson I, Sublett J, Morfeldt E, Novak R, et al. Capsular expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae negatively affects spontaneous and antibiotic-induced lysis and contributes to antibiotic tolerance. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:328–338. doi: 10.1086/380564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.TerAvest MA, He Z, Rosenbaum MA, Martens EC, Cotta MA, et al. Regulated expression of polysaccharide utilization and capsular biosynthesis loci in biofilm and planktonic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron during growth in chemostats. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:165–173. doi: 10.1002/bit.24994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter NT, Luis AS, Martens EC. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:966–967. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang SS, Bloom SM, Norian LA, Geske MJ, Flavell RA, et al. An antibiotic-responsive mouse model of fulminant ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Bjursell MK, Himrod J, Deng S, Carmichael LK, et al. A genomic view of the human-Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron symbiosis. Science. 2003;299:2074–2076. doi: 10.1126/science.1080029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter NT, Canales P, Peterson DA, Martens EC. A subset of polysaccharide capsules in the human symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron promote increased competitive fitness in the mouse gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh S, Porter NT, Donermeyer DL, Horvath S, Strout G, et al. Polysaccharide capsules equip the human symbiont Bacteroides thetaIotaomicron to modulate immune responses to a dominant antigen in the intestine. J Immunol. 2020;204:1035–1046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter NT, Hryckowian AJ, Merrill BD, Fuentes JJ, Gardner JO, et al. Phase-variable capsular polysaccharides and lipoproteins modify bacteriophage susceptibility in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron . Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1170–1181. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0746-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hryckowian AJ, Merrill BD, Porter NT, Van Treuren W, Nelson EJ, et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-infecting bacteriophage isolates inform sequence-based host range predictions. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson DA, Planer JD, Guruge JL, Xue L, Downey-Virgin W, et al. Characterizing the interactions between a naturally primed immunoglobulin A and its conserved Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron species-specific epitope in gnotobiotic mice. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12630–12649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.633800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearney JF, Radbruch A, Liesegang B, Rajewsky K. A new mouse myeloma cell line that has lost immunoglobulin expression but permits the construction of antibody-secreting hybrid cell lines. J Immunol. 1979;123:1548–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wegorzewska MM, Glowacki RWP, Hsieh SA, Donermeyer DL, Hickey CA, et al. Diet modulates colonic T cell responses by regulating the expression of a Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron antigen. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:32. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loschko J, Garcia K, Cooper D, Pride M, Anderson A. Flow cytometric assays to quantify Fhbp expression and detect serotype specific capsular polysaccharides on Neisseria meningitidis . Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1969:217–236. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9202-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjursell MK, Martens EC, Gordon JI. Functional genomic and metabolic studies of the adaptations of a prominent adult human gut symbiont, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, to the suckling period. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36269–36279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raftis EJ, Salvetti E, Torriani S, Felis GE, O’Toole PW. Genomic diversity of Lactobacillus salivarius . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:954–965. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01687-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL, Manchester JK, Hansen EE, Chiang HC, et al. A hybrid two-component system protein of a prominent human gut symbiont couples glycan sensing in vivo to carbohydrate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8834–8839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, Chen CH, Westover BP, et al. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science. 2005;307:1955–1959. doi: 10.1126/science.1109051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Hijum SA, Kralj S, Ozimek LK, Dijkhuizen L, van Geel-Schutten IG. Structure-function relationships of glucansucrase and fructansucrase enzymes from lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:157–176. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.157-176.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaluskar ZM, Garrison-Schilling KL, McCarter KS, Lambert B, Simar SR, et al. Manganese is an additional cation that enhances colonial phase variation of Vibrio vulnificus . Environ Microbiol Rep. 2015;7:789–794. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coyne MJ, Reinap B, Lee MM, Comstock LE. Human symbionts use a host-like pathway for surface fucosylation. Science. 2005;307:1778–1781. doi: 10.1126/science.1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]