To the Editors:

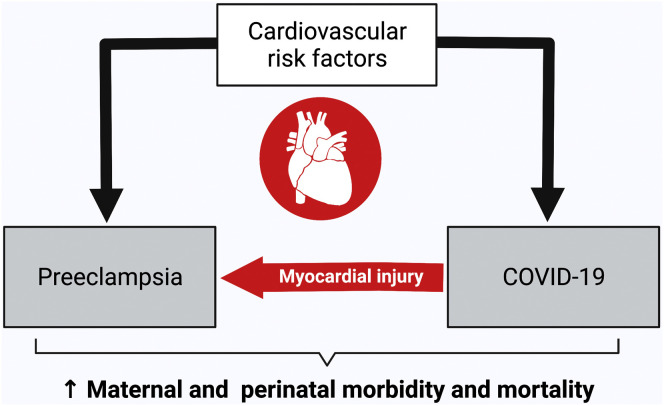

We read with interest the article by Conde-Agudelo and Romero.1 Their meta-analysis showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy increases the risk of preeclampsia by 62%. It also showed that this association remained significant even after adjusting for the confounding risk factors such as maternal age, body mass index, preexisting comorbidities, and ethnicity. Their meta-analysis also effectively proved that the latter preexisting maternal cardiovascular risk factors cannot entirely explain the nature of the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and preeclampsia. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated a bidirectional “dose-response” effect, with SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnancies having a 2-fold higher risk of severe preeclampsia; second, the association between infection and preeclampsia is stronger in symptomatic than in asymptomatic cases with COVID-19. Put together, these results suggest that maternal COVID-19 infection predisposes a patient to and triggers the development of preeclampsia. Although the mechanisms underlying COVID-19–related multiorgan manifestations are not completely understood, cardiovascular dysfunction is typical, and we believe that the possibility of an association between the latter finding and preeclampsia should be explored further.

Having maternal cardiovascular dysfunction predisposes a patient to preeclampsia. It predominates at the presentation of the disorder and persists as a cardiovascular legacy for decades following birth.2 It is entirely plausible that the complex relationship between COVID-19 infection and acute, severe cardiovascular dysfunction that has been described outside pregnancy may also occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy.3 Indeed, cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity are also predisposing factors for COVID-19 infection. Moreover, COVID-19 infection itself is known to cause acute myocardial injury, myocarditis, acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, and thromboembolism. SARS-CoV-2-related myocardial injury seems to be mostly related to a massive systemic inflammation and has been confirmed by elevated troponin and pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations and left ventricular dysfunction, both in and outside pregnancy. The finding of superimposed cardiovascular dysfunction in pregnant women who are critically ill because of COVID-19 is associated with an increased (13.3%) maternal mortality rate.4

Placental histologic studies are of limited value in understanding the pathophysiology of the COVID-19–related preeclampsia risk, because these are only available after birth and not during disease development. The authors suggested that a placentally-derived angiogenic imbalance may explain the predisposition to preeclampsia in maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. We hypothesize that even in asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 maternal infection, myocardial injury and subclinical cardiovascular dysfunction leading to acquired uteroplacental malperfusion and ischemia may lead to an angiogenic imbalance and the subsequent development of preeclampsia (Figure ).2 Further studies on the assessment of the maternal cardiovascular system by noninvasive imaging techniques and cardiac biomarkers in pregnancies complicated by SARS-CoV-2 infection could be beneficial to improve the prenatal and postnatal care of these women, considering the worse prognosis related to the myocardial injury and also, to prove this hypothesis.

Figure.

Relationship among cardiovascular risk factors, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and preeclampsia

Created with BioRender.com.

Giorgione.SARS-CoV-2 related myocardial injury and predisposition to preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

V.G.’s doctoral work is a part of the iPLACENTA project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no 765274.

References

- 1.Conde-Agudelo A., Romero R. SARS-COV-2 infection during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.07.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melchiorre K., Giorgione V., Thilaganathan B. The placenta and preeclampsia: villain or victim? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.024. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiga M., Wang D.W., Han Y., Lewis D.B., Wu J.C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:543–558. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercedes B.R., Serwat A., Naffaa L., et al. New-onset myocardial injury in pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a case series of 15 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.031. 387.e1–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]