Abstract

Purpose

Oral chlorhexidine is used widely for mechanically ventilated patients to prevent pneumonia, but recent studies show an association with excess mortality. We examined whether de-adoption of chlorhexidine and parallel implementation of a standardized oral care bundle reduces intensive care unit (ICU) mortality in mechanically ventilated patients.

Methods

A stepped wedge cluster-randomized controlled trial with concurrent process evaluation in 6 ICUs in Toronto, Canada. Clusters were randomized to de-adopt chlorhexidine and implement a standardized oral care bundle at 2-month intervals. The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes were time to infection-related ventilator-associated complications (IVACs), oral procedural pain and oral health dysfunction. An exploratory post hoc analysis examined time to extubation in survivors.

Results

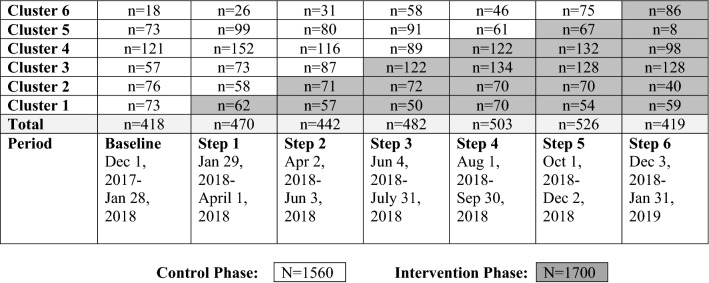

A total of 3260 patients were enrolled; 1560 control, 1700 intervention. ICU mortality for the intervention and control periods were 399 (23.5%) and 330 (21.2%), respectively (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.82 to 1.54; P = 0.46). Time to IVACs (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.06; 95% CI 0.44 to 2.57; P = 0.90), time to extubation (aHR 1.03; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.23; P = 0.79) (survivors) and oral procedural pain (aOR, 0.62; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.10; P = 0.10) were similar between control and intervention periods. However, oral health dysfunction scores (− 0.96; 95% CI − 1.75 to − 0.17; P = 0.02) improved in the intervention period.

Conclusion

Among mechanically ventilated ICU patients, no benefit was observed for de-adoption of chlorhexidine and implementation of an oral care bundle on ICU mortality, IVACs, oral procedural pain, or time to extubation. The intervention may improve oral health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-021-06475-2.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine; Critical care; De-adoption; Oral health; Randomized controlled trial; Respiration, artificial

Take-home message

| Among 3260 critically ill mechanically ventilated patients, we observed no benefit of de-adoption of chlorhexidine and implementation of an oral care bundle on ICU mortality, IVACs or time to extubation. However, the intervention improved oral health status. Lack of attainment of the predetermined sample size limited our ability to detect assumed differences in clinical outcomes. |

Introduction

In the last two decades, concerns about the association between ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and intensive care unit (ICU) mortality led to widespread adoption of the VAP prevention bundle [1]. This “bundle” consolidates multiple prevention strategies into one care package that, when systematically implemented, reduces infection-related ventilator-associated conditions (IVACs), such as VAP [2]. A key element of VAP bundles is chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse, which is used to prevent growth and aspiration of oropharyngeal bacteria linked to the development of VAP [3]. Inclusion of chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse in VAP bundles was based on meta-analyses reporting a 30–40% decrease in VAP rates and the belief that VAP was associated with excess ICU mortality [4]. While, VAP-attributable ICU mortality is relatively low (1–10%), it is associated with prolonged ventilation and higher treatment costs, and is therefore important to address [5, 6].

Cross-sectional surveys demonstrate up to 70% of ICUs in North America and Europe have adopted daily oral care with chlorhexidine as a simple, low-cost approach to VAP prophylaxis. However, new data have prompted re-evaluation of recommendations for daily oral care using chlorhexidine. Two independent meta-analyses suggest chlorhexidine may cause excess mortality in medical-surgical ICU patients whilst failing to prevent VAP [7, 8]. Other drawbacks include an unexpectedly high rate of oral lesions in patients exposed to 2% chlorhexidine [9] and evidence of reduced VAP pathogen susceptibility to chlorhexidine [10, 11]. These disadvantages may increase oral procedural pain due to disruption of oral mucosa integrity and possibly contribute to an increased risk of mortality through oral-systemic infection with antibiotic-resistant organisms [12].

When current practice is shown to be ineffective or harmful, or where potential harms outweigh benefits, de-adoption, defined as the discontinuation of a medical practice following its previous adoption, is recommended [13]. Research shows that routine practices indicated for de-adoption can persist, despite evidence of limited benefit or potential harm [14]. For example, clinician perceptions that chlorhexidine confers significant benefit, may contribute to concerns about withholding of this treatment and the need for an alternative course of action [15, 16]. Recommended strategies to address this phenomenon include a rigorous de-adoption trial that removes one intervention (i.e., chlorhexidine) whilst advancing an alternative (i.e., standardized oral care bundle) that is consistent with ethical and evidence-based practice. Outcomes of concern (i.e., ICU mortality, IVACs) should then be measured and reported to stakeholders [17].

Therefore, we conducted a multi-center stepped wedge cluster-randomized controlled trial (SW-cRCT) to evaluate whether de-adoption of oral chlorhexidine and implementation of a standardized oral care bundle reduces ICU mortality among mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. We hypothesized de-adoption of chlorhexidine prophylaxis and implementation of a standardized oral care bundle would reduce ICU mortality, IVACs, and oral procedural pain, while improving oral health status.

Rationale for a SW-cRCT design includes the expressed desire of participating clusters to de-adopt chlorhexidine, to facilitate intervention education in smaller groups (clusters) at pre-defined time-points, avoid contamination between intervention and control groups seen in parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, and alleviate ethical concerns about withholding the intervention.

Methods

A detailed description of our methods has been previously published [18]. In brief, we conducted a SW-cRCT recruiting six adult ICUs in five university-affiliated hospitals over a 14-month period from December 2017 to January 2019. Research ethics board approval was received from Clinical Trials Ontario (CTO), which provides provincial ethical review for multi-site research in qualifying institutions [19]. The need for written informed consent from patients was waived due to the nature of the proposed intervention and the intention among participating ICUs to de-adopt oral chlorhexidine [20]. As the need for consent was waived, study posters and letters of information were made available to surrogate decision-makers in the participating units. Trial registration in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03382730) was submitted on October 19, 2017; posting on December 26, 2017 was delayed due to an extended review process.

Study design

We followed CONSORT cluster trial extension guidelines for SW-cRCTs [21]. Each cluster (defined as one ICU) was randomly allocated to receive the intervention according to a staggered implementation schedule in one of six sequential steps occurring at 2-month intervals. All clusters commenced the study with a 2-month control (pre-intervention) period in which standard of care included 0.12% chlorhexidine oral care for IVAC prevention. Each cluster maintained chlorhexidine oral care until the month scheduled to de-adopt. Study completion comprised a 2-month period during which all clusters had fully de-adopted chlorhexidine and implemented the oral care bundle. Guided by a framework for process evaluation of complex interventions in cluster-randomized trials, we conducted a concurrent mixed-methods process evaluation to assess ICU context, implementation fidelity, and mechanisms of impact.

Participants

We recruited 6 ICUs contributing patient demographic, treatment, and outcome data to the Toronto Intensive Care Observational Registry (iCORE). Participating ICUs were of variable size (range 14–36 staffed beds), located within urban university-affiliated hospital settings, were general medical-surgical and specialty (trauma, oncology, neurological, cardiovascular) ICUs, and were managed under an intensivist-led closed ICU model. Nurses managed mechanically ventilated patients with primarily a 1:1 nurse-to-patient ratio; respiratory therapists (RT) were present in all ICUs at approximately a 1:8 RT-to-patient ratio. All adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) who received invasive mechanical ventilation during the study period were eligible for inclusion.

Randomization and masking, data collection and interventions

The allocation sequence and secondary outcome data collection dates were generated by the study statistician using a computer-generated randomization scheme. ICU staff in each cluster were given 2 months advance notice of their scheduled date to cross-over into the intervention period.

Data collection

Dedicated iCORE data collectors prospectively registered all mechanically ventilated patients admitted to participating ICUs and abstracted a daily minimum data set including but not limited to physiological variables, ventilation parameters, oxygenation, antibiotics, adjunctive therapies, and discharge disposition. In the 2 months preceding chlorhexidine de-adoption and standardized oral care bundle introduction at each site, and monthly thereafter, at randomly selected time-points trained assessors observed oral care delivery components and duration, procedural oral pain presence using the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) (range 0–8, score > 2 indicating pain) [22] and oral health dysfunction using the Beck Oral Assessment Scale (BOAS) (range, 5 [no dysfunction] to 20 [severe dysfunction]) [23].

Control

Daily oral care in the control period included 0.12% topical oral chlorhexidine rinse applied four times per day and a unit protocol comprising tooth brushing, oral suctioning, and mouth/lip moisturization individualized to patient needs.

Intervention

On commencement of the intervention period, we delivered an integrated knowledge translation (iKT) strategy including point-of-care education [24] to implement the evidence-based multicomponent oral care bundle. The bundle comprised twice daily (morning and evening) oral assessment and tooth brushing; mouth moisturization, lip moisturization with additional secretion removal every 4 h (Supplement 1; Table 1) [18]. We introduced an iKT oral care tool kit comprising a one-page study summary, detailed oral care protocol, template medical order set, instructional oral care video, and an ICU patient/family video of testimonials of the importance of the oral care bundle. Cluster leads and unit champions distributed the iKT oral care tool kit to frontline ICU nursing and allied health staff.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Control (n = 1560) |

Intervention (n = 1700) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Patients | ||

| Total No. | 1560 | 1700 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 60.3 (16.9) | 59.4 (17.6) |

| Sex (female) | 604 (38.7) | 644 (37.9) |

| Operative status | ||

| Non-operative | 908 (58.2) | 1078 (63.4) |

| Post-operative | 650 (41.7) | 621 (36.5) |

| APACHE II (mean, SD) | 23.9 (8) | 25.2 (7.9) |

| APACHE III diagnostic categories | ||

| Respiratory | 384 (24.7) | 389 (22.9) |

| Neurologic | 273 (17.5) | 238 (14) |

| Vascular/cardiovascular | 237 (15.2) | 101 (5.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 185 (11.9) | 235 (13.8) |

| Cardiovascular | 118 (7.6) | 124 (7.3) |

| Trauma | 116 (7.5) | 269 (15.8) |

| Sepsis | 105 (6.7) | 130 (7.7) |

| Metabolic | 46 (2.9) | 33 (1.9) |

| Other medical diseases | 39 (2.5) | 98 (5.8) |

| Hematologic | 16 (1.03) | 27 (1.5) |

| Renal disease | 7 (0.4) | 8 (0.4) |

| Gynecologic | 4 (0.3) | 17 (1) |

| Number of comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 472 (30.3) | 625 (36.8) |

| 1 | 563 (36.1) | 529 (31.1) |

| ≥ 2 | 525 (33.7) | 546 (32.1) |

SD standard deviation

On a date specified by the randomization schedule, we liaised with pharmacists at each site to remove oral chlorhexidine rinse from ICU stock and initiate the medical order set prescribing the non-chlorhexidine oral care bundle.

Outcomes and follow-up

The primary outcome was change in ICU mortality between control and intervention periods. Pre-specified secondary outcomes included time to IVACs between control and intervention periods. An IVAC was defined as a ventilator-associated condition (VAC)—an episode of worsening oxygenation defined by an increase in required levels of positive-end expiratory pressure (PEEP) and/or FiO2 for at least 2 calendar days following a period of stability or improvement with systemic inflammatory response elements suggestive of a new infection—leukocytosis/leukopenia or hypothermia/hyperthermia plus administration of a new antimicrobial agent [25, 26]. Other secondary outcomes were oral health status dysfunction measured using the BOAS, procedural oral pain measured using the CPOT, and fidelity of the intervention measured using an oral care bundle component checklist. ICU mortality was appraised by blinded assessors. To ensure BOAS, CPOT and fidelity outcomes were measured objectively and reliably, we employed assessors independent of unit staff to collect data. As prior research evaluating chlorhexidine prophylaxis has not provided sufficient evidence on the effect on duration of mechanical ventilation [27], we performed an exploratory post hoc analysis to assess the impact of the intervention on time to extubation for ICU survivors.

Sample size

Based on a previous meta-analysis, we determined chlorhexidine may increase ICU mortality with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.25 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05 to 1.50). This corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.18 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.33). A sample of 300 patients per month across 6 clusters, for a total of 4200 patients over a 14-month period, would provide 80% power to detect an absolute mortality difference of 5.5% from a baseline rate of 26%, assuming an intra-cluster correlation (ICC) of 0.001. Previous ICU studies reporting BOAS scores demonstrate a mean [standard deviation (SD)] of 10 (2) [23]. With 150 patients in each time period, we would have 80% power to detect a 2-point minimally important decrease in BOAS score indicating improved oral health.

Statistical analysis

ICU mortality was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model with a binary distribution and logit link with random intercept to account for clustering of patients within sites and adjusting secular trends with time in days from start of the study as linear effect. Due to the small number of clusters, we adjusted for age, sex, APACHE II predicted mortality, and operative/non-operative status at ICU admission in our primary analysis. Number of comorbidities was in our original model but removed as it was correlated with APACHE II predicted mortality. Operative/non-operative status at ICU admission was added to the model as we observed differences in patient characteristics between baseline and intervention groups. Patients meeting IVAC criteria were included in time to IVAC evaluation, which was analyzed using a Fine-Gray model to account for competing risk of death with adjusting for the same covariates as for mortality. In this model, we used ICU as a fixed effect to account for clustering. For ICU mortality and IVAC rates, we excluded those patients exposed to both the control and intervention phases. BOAS was summarized using mean (SD) and analyzed using a linear mixed model (taking into account repeated measures per patient) with the treatment phase as an independent variable and adjusting for age, sex, number of orally placed tubes, and number of ICU days. BOAS adjustments were based upon sex differences in oral disease [28], increasing levels of plaque accumulation during ICU treatment [29], and greater numbers of oral tubes impeding preventative oral care [30]. Based on prior research demonstrating procedural pain during routine oral care, we dichotomized CPOT (< 3 and ≥ 3) scores to determine absence/presence of procedural pain and adjusted the analysis with the same covariates as the BOAS scores. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for post hoc analysis of time to extubation among survivors adjusting for the same covariates as for IVACs. For ICU mortality and dichotomized CPOT scores, we report adjusted odds ratios (aOR), for time to event adjusted hazard ratios (aHR), and for BOAS score difference in scores together with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the time effect in 30-day increments. Analysis was performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and statistical significance was considered if P < 0.05.

Role of the funding source

Study funders had no role in the design, conduct, management and analysis of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decisions to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Trial centers and participants

From December 2017 to January 2019, 3260 patients were enrolled (Fig. 1). Demographic characteristics differed between groups for diagnostic category, APACHE II score, and the number of chronic coexisting conditions (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Stepped wedge allocation of patients and hospitals to control and intervention phases according to stepped wedge design

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary analysis of ICU mortality was based on 3246 patients who had complete data. After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics, ICU mortality for the intervention and control periods were 399 (23.5%) and 330 (21.2%), respectively (aOR 1.13; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.54; P = 0.46). The ICC for ICU mortality after adjusting for covariates was 0.013 and there was no significant secular time trends (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.01, P = 0.21). A total of 1934 patients met eligibility for IVAC evaluation. Time to IVACs (aHR 1.06; 95% CI 0.44 to 2.57; P = 0.90) and time to extubation (survivors only) (aHR 1.03; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.23; P = 0.79) were similar with no secular time trends for either IVAC (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.16; P = 0.33) or time to extubation (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.02). Absence of oral procedural pain was similar between periods (aOR 1.62; 95% CI 0.90 to 2.91; P = 0.10); however, oral health dysfunction scores (− 0.96; 95% CI − 1.75 to − 0.17; P = 0.02) improved in the intervention period (Table 2). For full cohort figures, see Supplement 2.

Table 2.

Adjusted primary and secondary trial outcomes

| Control, n (%) | Intervention, n (%) | Estimatea, (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU mortality group, N | 1555 | 1691 | ||

| ICU mortalityb | 330 (21.2) | 399 (23.5) | 1.13 (0.82 to 1.54) | 0.46 |

| IVAC group, N | 947 | 987 | ||

| IVACsb | 24 (2.5) | 48 (4.8) | 1.06 (0.44 to 2.57) | 0.90 |

| BOAS group, N | 154 | 182 | ||

| BOAS mean score (SD)c | 11.24 (3.2) | 10.47 (3.2) | − 0.96 (1.75 to − 0.17) | 0.02 |

| BOAS categorized | ||||

| No dysfunction (5) | 8 (5.0) | 6 (3.1) | ||

| Mild dysfunction (6–10) | 50 (32.5) | 86 (47.2) | ||

| Moderate dysfunction (11–15) | 80 (51.9) | 78 (42.8) | ||

| Severe dysfunction (16–20) | 16 (10.4) | 12 (6.5) | ||

| CPOT group, N | 154 | 184 | ||

| CPOT mean score (SD) | 2.32 (1.9) | 2.27 (1.9) | 1.62 (0.91 to 2.91) | 0.10 |

| CPOT categorizedc | ||||

| < 3 | 77 (50) | 106 (57.6) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 77 (50) | 78 (42.3) | ||

| Time to extubation group (survivors), N | 1061 | 994 | ||

| Time to extubation, median, days (IQR)b (SD) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 1.03 (0.85 to 1.23) | 0.79 |

BOAS Beck Oral Health Assessment Score, CPOT Critical-Care Pain Observational Tool, ICU Intensive Care Unit, IQR interquartile range, IVAC infection-related ventilator-associated, SD standard deviation

aOdds ratios for ICU mortality and CPOT dichotomized. Hazard ratio for IVAC and beta coefficient (change in average BOAS score in the intervention group vs control)

bP value based on an analysis that adjusts for age, sex, predicted mortality based on APACHE, operative status as well as secular trends and clustering of patients within ICU

cP values based on analysis adjusting for age, sex, admission category and number of tubes as well as the repeated measures per patient

Intervention fidelity

Among 348 randomly observed oral care encounters (see Supplement 1; Table 2), we identified 100% compliance with oral chlorhexidine de-adoption in the intervention period (61.4% vs. 0%; P < 0.0001). Delivery of 4 out of 5 elements of the oral care bundle increased in the intervention phase: oral assessment, 12.7% vs. 46.3%, P < 0.0001; tooth brushing, 36.7% vs. 72.6%, P < 0.0001; oral moisturization, 49.4% vs. 100%, P < 0.0001; and lip moisturization, 48.1% vs. 81.6%, P < 0.0001. No difference was noted for oral suctioning (94.3% vs. 89.5%; P = 0.11). The mean duration of oral care per observed encounter was longer in the intervention period compared to control: 4.47 min vs 3.71 min (P = 0.0086).

Discussion

In this SW-cRCT recruiting 3260 mechanically ventilated patients in six adult ICUs, we observed no ICU mortality benefit of an intervention comprising de-adoption of oral chlorhexidine and implementation of an oral care bundle. Other outcomes including time to IVACs, time to extubation in ICU survivors, and oral procedural pain were similar between control and intervention periods. Oral health scores improved during the intervention period but at a level below the minimally clinically important difference for this metric. Monitoring of intervention fidelity demonstrated successful de-adoption of chlorhexidine (100%) and increased delivery of 4 out of 5 oral care bundle components in ≥ 70% of patients.

Contrary to our a priori hypothesis that de-adoption would decrease ICU mortality, we found no effect on mortality between control and intervention periods. This differs from the conclusions of a previous meta-analysis by Price and colleagues reporting increased mortality in patients exposed to daily chlorhexidine oral care [8]. A potential explanation for no difference in ICU mortality found in our study is a lower concentration of chlorhexidine used in the participating units in comparison to previous studies (0.12% versus ≥ 1%) [3]. Higher concentrations of chlorhexidine are theorized to disrupt oral mucosa integrity, possibly contributing to an increased risk of bacteria translocating from the oral cavity to the bloodstream resulting in excess death [12]. Furthermore, previous trials were designed to detect differences in VAP, rather than ICU mortality, which may also explain the lack of an observed effect on mortality in our study [7]. Our findings are consistent with a recent retrospective observational cohort study including 8916 ICU patients demonstrating no increased risk of death in mechanically ventilated patients receiving chlorhexidine oral care [31].

Our research team completed initial and ongoing staff engagement in the participating units, which are part of an Academic Health Sciences Network. These efforts may have built upon existing network collegiality to improve stakeholder buy-in for the removal of chlorhexidine and replacement with a standardized oral care bundle. Implementation of an immediate alternative to chlorhexidine oral care follows recommendations for de-adopting ineffective or harmful practices [17]. Our iKT implementation process comprising bundle education, audit and feedback, and reminders may have facilitated an observed increase in the comprehensiveness of oral care and a decrease in oral health dysfunction scores during the intervention period. Regular tooth brushing and moisture application may inhibit bacterial overgrowth, inflammation, mouth sores and dental disease associated with inadequate salivary flow [32]. Similar to other research in VAP prevention, our intervention required interdisciplinary team involvement [33] to deploy established strategies to improve care delivery including staff education, surveillance of compliance, and reporting of performance measures [34]. Hospitals may need to prioritize oral care education, audit and feedback, and reminders for similar results.

This trial has several strengths. First, our chlorhexidine de-adoption and oral care bundle implementation intervention comprised a low-cost multi-center research collaboration involving discrete ICUs with broad case mix, making our results generalizable. Importantly, the total research costs for this trial (excluding investigator costs) were $52,543 US dollars giving a cost per patient recruited of only US$16. In previous multicentre trials the costs per patient recruited is quoted as an average of US$4200 [35]. By leveraging existing infrastructure, our trial was cost-efficient compared to contemporary clinical trials. However, further studies of cost effectiveness are required to study practice based costs for this intervention. Another strength of our study is its use of patient-centered outcomes (e.g., ICU mortality, IVACs, time to extubation in survivors) from clinical data that are readily available in existing electronic data systems [36]. Our process evaluation provides clinicians and policy-makers with clear information about implementation strategies, thereby strengthening interpretation, replication and potentially assuaging uncertainties about the negative consequences of withholding chlorhexidine [15, 37].

Several limitations must be considered. First, unlike parallel group individual patient RCTs, a stepped-wedge cluster design produces a fixed number and duration of steps, thereby removing any flexibility to add clusters or lengthen control and intervention periods to recruit additional participants [38]. Therefore our final sample size fell short of the participant number anticipated in our sample size calculations and has insufficient power to detect a mortality difference. Second, lower than anticipated baseline compliance with chlorhexidine and basic oral care delivery may be due to failure of random oral care fidelity observation to coincide with prescribed chlorhexidine delivery times or oral care routines. Third, we observed differences in patient characteristics between study periods within and between centers as would be expected in a stepped wedge cluster-randomized trial. However, we accounted for this by adjusting for center, time, and baseline characteristics in our analyses, although unmeasured confounding may still be present [39]. Fourth, due to the implementation of two interventions, we are unable to separate the effect of chlorhexidine de-adoption versus implementation of an oral care bundle on oral health scores. Finally, we were unable to blind clinical staff to study allocation due to the nature of the intervention.

Conclusion

Among mechanically ventilated ICU patients, de-adoption of chlorhexidine and implementation of an oral care bundle has no effect on ICU mortality, time to IVACs, time to extubation in ICU survivors, or oral procedural pain. Oral health scores improved during the intervention period but at a level below the minimally clinically important difference for this metric. Therefore, it is reasonable for ICUs to focus on improvements in oral care delivery until further evidence becomes available.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the significant work and dedication of our research team including Michael Detsky, Jan Friedrich, Clare Fielding, Kaila Wingrove, Carlos R. Quiñonez, and Susan Sutherland. We are also grateful for the contributions of our research assistants Julie Moore, Teresa Valenzano, and Tiffany Jefkins.

Author contributions

CMD and BHC had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. BHC, CMD, LR, RP, ACK-BA, EF, and DCS conceptualized and designed the study. CMD, BHC, OMS, LB, VAM, RP, LR, ACK-BA, EF, DCS and SC contributed to the acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation of the data. CMD, LR, BHC and RP drafted the original manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. RP conducted all statistical analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by the Network for Canadian Oral Health Research (NCOHR) and the Canadian Lung Association.

Data availability

A de-identified dataset and the study protocol may be made available to researchers with a methodologically sound proposal, to achieve the aims described in the approved proposal. Data will be available upon request beginning 9 months and ending 36 months following article publication. Requests for data should be directed at craig.dale@utoronto.ca to gain access, and requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report in the conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rello J, Afonso E, Lisboa T, Ricart M, Balsera B, Rovira A, Valles J, Diaz E, Investigators FP. A care bundle approach for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camporota L, Brett S. Care bundles: implementing evidence or common sense? Crit Care. 2011;15:159. doi: 10.1186/cc10232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua F, Xie H, Worthington HV, Furness S, Zhang Q, Li C. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):CD008367. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labeau SO, Van de Vyver K, Brusselaers N, Vogelaers D, Blot SI. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia with oral antiseptics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:845–854. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR, Howell MD, Lee G, Magill SS, Maragakis LL, Priebe GP, Speck K, Yokoe DS, Berenholtz SM. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:915–936. doi: 10.1086/677144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muscedere J, Sinuff T, Heyland DK, Dodek PM, Keenan SP, Wood G, Jiang X, Day AG, Laporta D, Klompas M. The clinical impact and preventability of ventilator-associated conditions in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest. 2013;144:1453–1460. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, Greene LR, Berenholtz SM. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:751–761. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price R, MacLennan G, Glen J. Selective digestive or oropharyngeal decontamination and topical oropharyngeal chlorhexidine for prevention of death in general intensive care: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2197. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plantinga NL, Wittekamp BHJ, Leleu K, Depuydt P, Van den Abeele AM, Brun-Buisson C, Bonten MJM. Oral mucosal adverse events with chlorhexidine 2% mouthwash in ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:620–621. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cieplik F, Jakubovics NS, Buchalla W, Maisch T, Hellwig E, Al-Ahmad A. Resistance toward chlorhexidine in oral bacteria - is there cause for concern? Front Microbiol. 2019;10:587. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampf G. Acquired resistance to chlorhexidine - is it time to establish an 'antiseptic stewardship' initiative? J Hosp Infect. 2016;94:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellissimo-Rodrigues WT, Menegueti MG, de Macedo LD, Basile-Filho A, Martinez R, Bellissimo-Rodrigues F. Oral mucositis as a pathway for fatal outcome among critically ill patients exposed to chlorhexidine: post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care. 2019;23:382. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2664-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niven DJ, Mrklas KJ, Holodinsky JK, Straus SE, Hemmelgarn BR, Jeffs LP, Stelfox HT. Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: a scoping review. BMC Med. 2015;13:255–255. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0488-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyu PF, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, Howard DH, Buchman TG, Murphy DJ. Impact of a sequential intervention on albumin utilization in critical care. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1307–1313. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15:2. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittekamp BH, Plantinga NL. Less daily oral hygiene is more in the ICU: no. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(3):331–333. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06359-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helfrich CD, Rose AJ, Hartmann CW, van Bodegom-Vos L, Graham ID, Wood SJ, Majerczyk BR, Good CB, Pogach LM, Ball SL, Au DH, Aron DC. How the dual process model of human cognition can inform efforts to de-implement ineffective and harmful clinical practices: a preliminary model of unlearning and substitution. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:198–205. doi: 10.1111/jep.12855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale CM, Rose L, Carbone S, Smith OM, Burry L, Fan E, Amaral ACK, McCredie VA, Pinto R, Quinonez CR, Sutherland S, Scales DC, Cuthbertson BH. Protocol for a multi-centered, stepped wedge, cluster randomized controlled trial of the de-adoption of oral chlorhexidine prophylaxis and implementation of an oral care bundle for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: the CHORAL study. Trials. 2019;20:603. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3673-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical Trials Ontario (2021) Streamlined research ethics review. https://www.ctontario.ca/cto-programs/streamlined-research-ethics-review/. Accessed 01 Jan 2021

- 20.Weijer C, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, McRae AD, White A, Brehaut JC, Taljaard M, Ottawa Ethics of Cluster Randomized Trials Consensus Group The Ottawa statement on the ethical design and conduct of cluster randomized trials. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001346–e1001346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemming K, Taljaard M, McKenzie JE, Hooper R, Copas A, Thompson JA, Dixon-Woods M, Aldcroft A, Doussau A, Grayling M, Kristunas C, Goldstein CE, Campbell MK, Girling A, Eldridge S, Campbell MJ, Lilford RJ, Weijer C, Forbes AB, Grimshaw JM. Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2018;363:k1614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dale CM, Prendergast V, Gelinas C, Rose L. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool (CPOT) for the detection of oral-pharyngeal pain in critically ill adults. J Crit Care. 2018;48:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ames NJ, Sulima P, Yates JM, McCullagh L, Gollins SL, Soeken K, Wallen GR. Effects of systematic oral care in critically ill patients: a multicenter study. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:e103–114. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinuff T, Muscedere J, Adhikari NK, Stelfox HT, Dodek P, Heyland DK, Rubenfeld GD, Cook DJ, Pinto R, Manoharan V, Currie J, Cahill N, Friedrich JO, Amaral A, Piquette D, Scales DC, Dhanani S, Garland A. Knowledge translation interventions for critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2627–2640. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182982b03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klompas M, Berra L. Should ventilator-associated events become a quality indicator for ICUs? Respir Care. 2016;61:723–736. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2020) Ventilator-associated event (VAE). https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/10-vae_final.pdf. Retrieved 20 Dec 2020

- 27.Zhao T, Wu X, Zhang Q, Li C, Worthington HV. Hua F (2020) Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):CD008367. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiau HJ, Reynolds MA. Sex differences in destructive periodontal disease: exploring the biologic basis. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1505–1517. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terezakis E. The impact of hospitalization on oral health: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:628–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dale CM, Smith O, Burry L, Rose L. Prevalence and predictors of difficulty accessing the mouths of intubated critically ill adults to deliver oral care: an observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;80:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deschepper M, Waegeman W, Eeckloo K, Vogelaers D, Blot S. Effects of chlorhexidine gluconate oral care on hospital mortality: a hospital-wide, observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1017–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5171-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennesen P, van der Ven A, Vlasveld M, Lokker L, Ramsay G, Kessels A, van den Keijbus P, van Nieuw AA, Veerman E. Inadequate salivary flow and poor oral mucosal status in intubated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:781–786. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000053646.04085.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNally E, Krisciunas GP, Langmore SE, Crimlisk JT, Pisegna JM, Massaro J. Oral care clinical trial to reduce non-intensive care unit, hospital-acquired pneumonia: lessons for future research. J Healthc Qual. 2019;41:1–9. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellingson K, Haas JP, Aiello AE, Kusek L, Maragakis LL, Olmsted RN, Perencevich E, Polgreen PM, Schweizer ML, Trexler P, VanAmringe M, Yokoe DS. Strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections through hand hygiene. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:937–960. doi: 10.1086/651677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ernst R CI (2014) Price indexes for clinical trial research: a feasibility study. In: Services DoIaM, editor. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

- 36.Klompas M, Berra M. Should ventilator-associated events become a quality indicator for ICUs? Respir Care. 2016;61(6):723–736. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D, Baird J. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemming K, Taljaard M. Sample size calculations for stepped wedge and cluster randomised trials: a unified approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemming K, Taljaard M. Reflection on modern methods: when is a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial a good study design choice? Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:1043–1052. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A de-identified dataset and the study protocol may be made available to researchers with a methodologically sound proposal, to achieve the aims described in the approved proposal. Data will be available upon request beginning 9 months and ending 36 months following article publication. Requests for data should be directed at craig.dale@utoronto.ca to gain access, and requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.