Abstract

Purpose of review:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. Over the past year, COVID-19 has posed a significant threat to global health. Although the infection is associated with mild symptoms in many patients, a significant proportion of patients develop a prothrombotic state due to a combination of alterations in coagulation and immune cell function. The purpose of this review is to discuss the pathophysiological characteristics of COVID-19 that contribute to the immunothrombosis.

Recent findings:

Endotheliopathy during COVID-19 results in increased multimeric von Willebrand factor release and the potential for increased platelet adhesion to the endothelium. In addition, decreased anticoagulant proteins on the surface of endothelial cells further alters the hemostatic balance. Soluble coagulation markers are also markedly dysregulated, including plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and tissue factor, leading to COVID-19 induced coagulopathy. Platelet hyperreactivity results in increased platelet-neutrophil and -monocyte aggregates further exacerbating the coagulopathy observed during COVID-19. Finally, the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm primes neutrophils to release neutrophil extracellular traps, which trap platelets and prothrombotic proteins contributing to pulmonary thrombotic complications.

Summary:

Immunothrombosis significantly contributes to the pathophysiology of COVID-19. Understanding the mechanisms behind COVID-19-induced coagulopathy will lead to future therapies for patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, coagulopathy, immunothrombosis, Neutrophil extracellular traps, platelets

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel coronavirus from zoonotic origin, first reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [1]. One year after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the spread of SARS-CoV-2 a global health emergency, over 113 million cases have been reported worldwide, causing more than 2.5 million deaths as a result of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2]. While most COVID-19 patients experience only mild symptoms such as fever and cough, more severe cases present with substantial pulmonary complications, such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), as well as an abnormal high rate of thrombosis [3–6*]. A meta-analysis of 36 studies calculated the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) as high as 28% for patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). In the non-ICU setting, the estimated incidence of VTE was 10% [7]. Although less common, arterial thrombotic events such as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction and systemic arterial embolism have also been reported [8, 9]. Numerous autopsy reports of COVID-19 patients described increased thrombi in pulmonary arteries [10–15] and small fibrin thrombi in the alveolar capillaries [16**–18]. While comparable observations were made for lungs from influenza A/H1N1-mediated ARDS patients [19, 20], alveolar capillary microthrombi were 9 times more prevalent in the COVID-19 patients [16**]. In agreement with this, a retrospective study from the Netherlands found a twofold higher 30-day VTE rate in hospitalized COVID-19 patients versus influenza patients [21*]. Similarly, an increased incidence of ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients compared to influenza patients was reported [22]. The observation that many COVID-19 patients with thrombotic complications were on standard prophylactic anticoagulation has raised the debate on whether therapeutic anticoagulation or alternative anti-thrombotic strategies should be considered [23–25]. However, properly controlled randomized clinical trials have yet to be finalized.

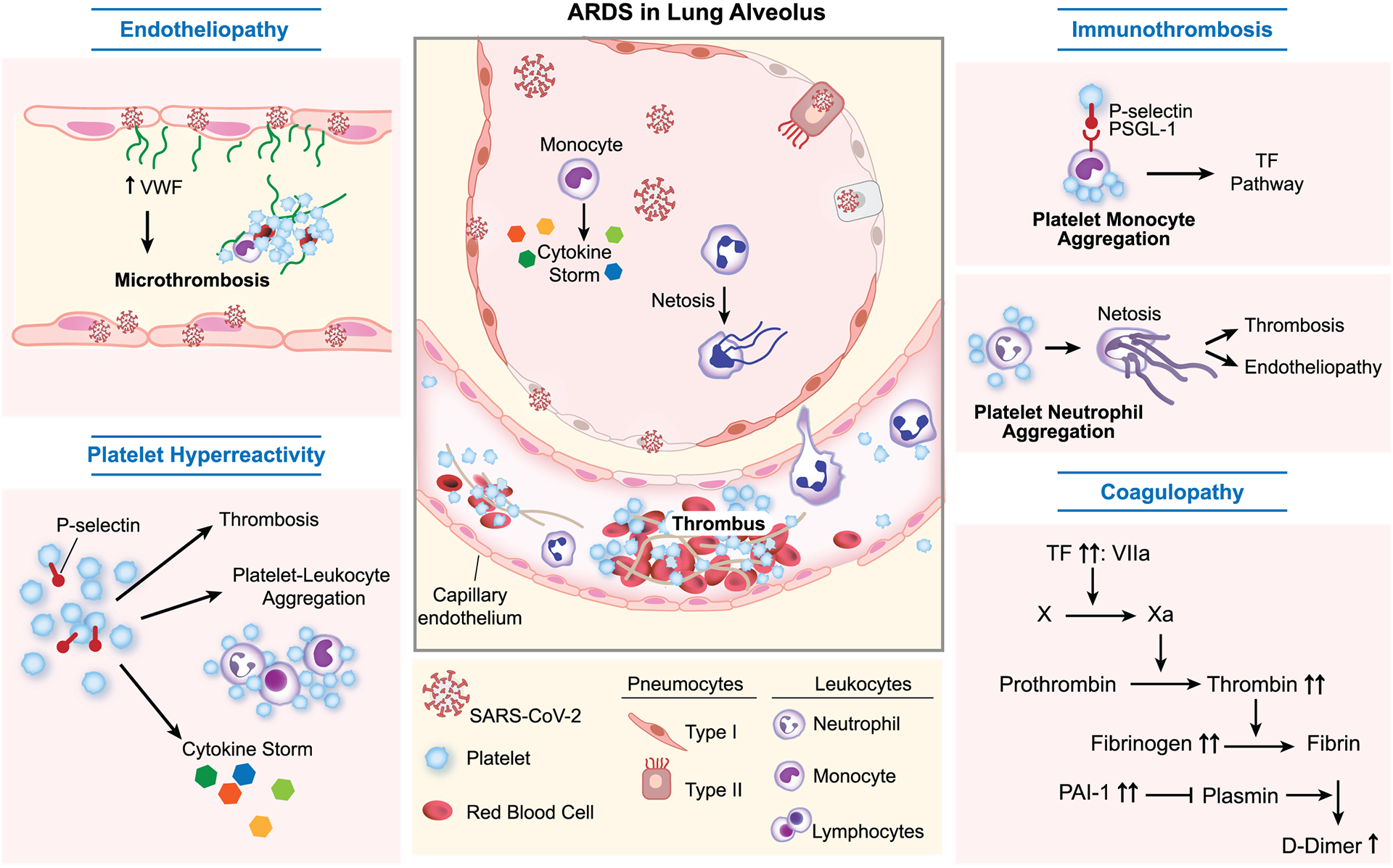

Clearly, thrombotic complications, and more specifically pulmonary thrombosis, are a hallmark of severe COVID-19 pathology and contribute to mortality. Pulmonary thrombi have been linked to the development of hypoxemia in the early stages of ARDS in COVID-19 and are estimated to contribute up to 10% of all COVID-19 related deaths [26*]. In this review, we will present an overview of emerging concepts in COVID-19 pathophysiology that explain the increased susceptibility to thrombotic complications. To this end we will discuss putative mechanisms and therapeutic approaches of pulmonary endotheliopathy, COVID-19 coagulopathy, platelet hyperreactivity and immunothrombosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of COVID-19 pathophysiology.

Severe COVID-19 is characterized by pulmonary complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and thrombosis. Increased susceptibility to thrombotic complications is caused by synergistic interplay of endotheliopathy, platelet hyperreactivity, immunothrombosis and coagulopathy. VWF, von Willebrand factor. TF, Tissue factor. PAI-1, Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

SARS-CoV-2 induced endotheliopathy

In normal blood vessels, the endothelial cell monolayer is designed to prevent pathological thrombus formation. Endothelial dysfunction is a principal determinant of microvascular dysfunction by shifting the vascular equilibrium towards vasoconstriction and a pro-coagulant state. Data from autopsy studies in COVID-19 have identified marked endothelial cell apoptosis [27**], together with loss of endothelial cell tight junctions in the pulmonary microvasculature [16**, 28]. SARS-CoV-2 infects the host cells using one of its spike glycoproteins to bind to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [29], which is expressed on several cell types, including endothelial cells [30*]. SARS-CoV-2 first binds ACE2 and is then cleaved by the serine protease TMPRSS2 to coordinate entry into the host cell [31**]. Varga and colleagues were the first to provide evidence of viral elements within endothelial cells [27**]. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus within endothelial cells suggests direct viral effects may contribute to the endothelial injury [32, 33]. Subsequent perivascular inflammation may provide a detrimental negative feedback loop, as plasma from COVID-19 patients has been shown to induce rapid endothelial cell cytotoxicity [34]. Notably, unique features of the lung endotheliopathy of COVID-19 have become apparent [16**, 35]. Compared to influenza patients, COVID-19 patients had increased endothelial disruption and alveolar capillary micro- and macrothrombi were more prevalent [16**, 18].

So far, no marker of endothelial dysfunction has been found to truly discriminate non-COVID-19 ARDS from COVID-19 ARDS [36, 37]. Nevertheless, several markers of endothelial dysfunction correlate with admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients [38–41]. Von Willebrand factor (VWF) has been studied the most, and appears to strongly predict outcomes. VWF is a multimeric glycoprotein produced exclusively by endothelial cells and megakaryocytes and plays an important role in hemostasis [42]. To maintain hemostasis, VWF acts as a bridge between the activated endothelium and platelets [43]. Besides its hemostatic role, VWF has recently been recognized as an effective mediator of inflammation. VWF actively participates in inflammatory processes by recruiting leukocytes at sites of vascular inflammation and plays a critical role in thromboinflammation [44]. Importantly, the activity of VWF is restricted by the metalloprotease ADAMTS13, which cleaves newly released highly active VWF multimers into smaller, less thrombogenic and inflammatory multimers [45]. Inefficient digestion of large VWF multimers is known to play a critical role in the pathogenesis underlying microvascular occlusion in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) [46], sickle cell disease [47] and sepsis [48].

In COVID-19 patients, VWF levels are markedly increased [37, 39*, 49–57*], while ADAMTS13 levels are significantly decreased [40, 49, 52, 58]. This imbalance results in elevated levels of highly reactive VWF multimers in the circulation, which spontaneously bind platelets, leading to thrombotic complications. Importantly, VWF hyperreactivity is strongly correlated to disease severity [52, 57*, 59, 60] and has been demonstrated in several independent studies to predict thrombotic complications [6*, 57*, 61], oxygen requirement [62] and mortality [41, 55, 60, 63, 64]. Similar to COVID-19, a mounting VWF/ADAMTS13 imbalance, culminating in the accumulation of platelet-rich microthrombi has been shown to induce secondary thrombotic microangiopathy in sepsis [48]. These observations have fueled the hypothesis that COVID-19 is a thrombotic microangiopathy similar to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) [65, 66]. However, unlike TTP, levels of ADAMTS13 are not fully reduced, and platelet counts are not decreased in most COVID-19 patients [67]. Nevertheless, the observed mild systemic VWF/ADAMTS13 imbalance might be exacerbated locally [68], e.g., in the pulmonary vascular bed where both virus-mediated endothelial damage [69, 70] and subsequent hypoxia [71] increase VWF release. Therapeutically, targeting excessive VWF with Caplacizumab, which inhibits platelet binding to VWF, might be an attractive avenue to treat SARS-CoV-2 associated thrombotic microangiopathy [72]. Alternatively, plasma exchange has been proposed to restore hemostatic balance and reduce levels of circulating inflammatory markers, as is done for several thrombotic microangiopathies [73].

Hemostatic abnormalities result in a procoagulant phenotype in COVID-19

Despite abundant hematological abnormalities, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was rarely detected in blood samples [74], implying an important pathological cross-talk between the disrupted endothelium, the COVID-19 associated cytokine storm and other components of blood [75]. Several receptors expressed on endothelial cells function to promote anticoagulant pathways, including thrombomodulin (TM). TM is a constitutively expressed transmembrane receptor with important anticoagulant and antifibrinolytic activities [76]. Numerous studies have reported increased levels of soluble thrombomodulin (sTM) in COVID-19 patients, indicating active shedding from the endothelial surface [36, 39*, 77]. Interestingly, plasma concentrations of soluble thrombomodulin correlate with in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients [39*]. Besides sTM, SARS-CoV-2 infection was also reported to affect other modulators of coagulation such as plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) [78–85], tissue-type plasminogen activator [81, 83, 85, 86], angiopoietin-2 [84, 87] and tissue factor (TF) [79]. Mechanistically, IL-6 is thought to be the causative cytokine for these observations, and clinical trials targeting IL-6 in COVID-19 patients have shown promising results [88–91]. IL-6 is known to directly impact the endothelium inducing increased levels of PAI-1 [82**], fibrinogen [92], and TF [93]. Changes in these hemostatic parameters result in an increased potential to form fibrin clots. This is evident in vivo by elevated levels of circulating D-dimers [94], a biomarker of both fibrin formation and degradation. Remarkably, even though the presence of D-dimers suggests fibrin is actively being lysed, autopsy studies revealed numerous fibrin depositions in the pulmonary microvasculature and alveolar space of lungs from patients with COVID-19 [10–15]. This suggests that dysregulation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways is a major aspect of COVID-19 pathogenesis and is not just a bystander to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Interestingly, a recent study observed sustained hypercoagulable changes in COVID-19 patients 4 months after hospital discharge, suggesting that patients might be susceptible for thrombotic complications well beyond recovery [95*]. Importantly, these findings suggest plasma from convalescent COVID-19 patients used in transfusion medicine could be hypercoagulable and future studies examining the effect of “long” COVID-19-induced coagulopathy on plasma transfusion are necessary.

Bleeding complications due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) are a common cause for death in severely ill septic patients [96] and has been a concern in COVID-19 patients [97]. Similar to COVID-19, critically-ill sepsis patients exhibit exaggerated inflammation and are at an increased risk of thrombotic complications. However, while patients with sepsis frequently present with thrombosis and bleeding that stem from consumption of platelets and coagulation factors [96, 98], this is only rarely seen in patients with COVID-19 [99]. Indeed, severe COVID-19 patients usually present with normal or only mildly reduced platelet counts, high fibrinogen levels and increased or unaltered prothrombin times [100–104]. Moreover, when we retrospectively compared plasma from septic and COVID-19 patients we observed significant differences between the two diseases [36]. Compared to healthy donors, patients with COVID-19 showed increased thrombin generation and increased endogenous plasmin generation. In contrast, septic patients had similar thrombin generation and endogenous plasmin generation compared to healthy donors. Both groups had increased fibrinogen levels resulting in enhanced fibrin formation in both COVID-19 and sepsis. However, sepsis patients had significant resistance to fibrinolysis compared to COVID-19. These data suggest fundamental differences in the pathophysiology of these diseases and highlight the need for tailored treatment for COVID-19-associated coagulopathy [105**, 106]. Accordingly, a number of clinical trials were initiated to determine the best antithrombotic strategy [107–111]. While these trials are still ongoing, interim results have shown that early initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation was associated with a decreased risk of 30-day mortality and no increased risk of serious bleeding events [112]. Furthermore, an important distinction in the therapeutic benefits for moderate and severely ill hospitalized patients has emerged. In a large clinical trial conducted in more than 300 hospitals worldwide (incorporating the REMAP-CAP, ATTACC and ACTIV-4a trials), full dose heparin given to moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19 was safe and reduced the requirement of vital organ support. In contrast, full dose heparin did not reduce the need for organ support in critically ill COVID-19 patients requiring ICU support and concerns were raised regarding an increased bleeding risk [113].

Platelets become hyperreactive during SARS-CoV-2 infection

Thrombocytopenia is common in viral infections [114] and considered a prognostic marker for mortality in ICU patients [115]. Surprisingly, most COVID-19 patients present with normal platelet counts or only mild thrombocytopenia [116]. Nevertheless, extensive meta-analyses indicate that low platelet counts are associated with more severe COVID-19 and an increased risk for adverse outcomes [116, 117*]. A possible explanation for these findings could be consumption of platelets during micro- and macro-vascular thrombosis, as several studies reported the presence of platelets in thrombi found in multiple organs of COVID-19 autopsy cases [53*, 118, 119*].

Morphologically, platelet ultrastructure appeared normal during SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, RNA-sequencing revealed significant changes in the platelet transcriptome of COVID-19 patients [120*]. Many differentially expressed transcripts appear to be unique for COVID-19 compared to other infectious diseases. However, the exact cause for altered gene expression remains unknown [121]. One possible explanation would be direct interactions of SARS-CoV-2 with platelets or megakaryocytes. Several platelet surface receptors have reported to mediate binding and entry of various viruses in platelets resulting in platelet activation [122]. Interestingly, only a subset (8–24%) of COVID-19 patients had detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in their platelets [120*, 123*]. Nevertheless, hyperreactive platelets are common in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [56, 118, 120*, 123*–125]. We and others reported P-selectin expression, a marker for platelet activation, was significantly increased on resting platelets from COVID-19 patients [56, 120*, 124*]. Additionally, COVID-19 platelets were more prone to activate after in vitro exposure to weak agonists as evidenced by significantly increased P-selectin exposure, platelet aggregation, IL-1β and soluble CD40 ligand production [56, 120*, 123*]. Intriguingly, the increased reactivity to low concentrations of thrombin seems to be specific to COVID-19 ARDS patients [126]. These observations lead to several clinical trials targeting platelets, with early results showing reduced mortality in COVID-19 patients treated with aspirin [127, 128].

The exact mechanism for hyperreactive platelets in COVID-19 is still unknown. Zhang and colleagues provided evidence for a direct interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE-2 on platelets, resulting in platelet activation through the MAPK pathway [125]. However, it is unlikely this suggested pathway is the sole contributor to platelet activation in COVID-19, considering several other groups were unable to detect ACE-2 RNA or protein on platelets or CD34+-derived megakaryocytes [120*, 123*, 129]. Intriguingly, not all markers of platelet activation were consistently up during COVID-19 pathology. PAC-1 binding, a marker for integrin αIIbβ3 activation, was reduced in platelets from COVID-19 patients compared to healthy donors after in vitro stimulation with different agonists [56, 120*, 130]. In addition, COVID-19 platelets also had a reduced ability to become procoagulant compared to healthy donor platelets [131]. The question remains if the reduced ability to form procoagulant platelets directly causes the hyper-aggregating platelets observed during COVID-19 [132] or whether exhausted platelets recirculate in the blood after activation and sequester in the lung [118]. Of interest to the latter hypothesis is the observation of increased circulating platelet extracellular vesicles [123*] and apoptotic platelets [133] in COVID-19 patients. The latter were induced by antibodies in COVID-19 sera and correlated with thrombotic events [133].

Finally, platelet activation during viral infections also triggers inflammation. Release of α-granule stored molecules, such as cytokines, chemokines and several surface molecules contribute to the recruitment and activation of immune cells [122]. Consistent with increased platelet P-selectin in COVID-19 patients, several studies also observed increased platelet-leukocyte aggregates [56, 120*, 124*, 130, 134]. Particularly, platelet-monocyte interactions are of interest as platelets from severe COVID-19 patients induce TF expression in monocytes, which correlated with disease severity and mortality [124*]. Moreover, platelet degranulation might contribute to the cytokine storm described in COVID-19 as many of the cytokines involved in viral infections were reduced in platelets from COVID-19 patients, indicating active release [123*].

Inflammation induced thrombosis contributes to outcomes in COVID-19

An important and common observation from COVID-19 autopsy studies is the involvement of leukocytes within platelet-rich macro and micro-vascular occlusions in the lung, kidney and heart [135, 136]. Circulating platelet-leukocyte complexes are common in COVID-19 and are thought to contribute to disease progression [56, 118, 120*, 124*, 134]. In particular, platelet-neutrophil interactions are known to induce the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [137–139]. NET formation is a form of neutrophil cell death, triggered to trap and kill invading pathogens [140]. NETs are extracellular webs of decondensed chromatin decorated with histones and antimicrobial proteins. However, NETs also capture blood cells and form a procoagulant and prothrombotic scaffold [139, 141] associated with detrimental collateral damage in sepsis and other thromboinflammatory diseases [142]. Several studies have identified NETs as important constituents of micro- and macro-vascular thrombi [14, 143–146] and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [53*] in COVID-19 patients, even after virus clearance from the lungs [147]. Additionally, biomarkers of NETs are increased in serum [148] and plasma [49, 59, 147, 149–151] from COVID-19 patients and correlate with disease severity[144], were associated with thrombosis [152, 153] and predicted outcomes [150*–152]. Neutrophils from COVID-19 patients readily made NETs, unlike healthy neutrophils, and plasma from COVID-19 patients induced in vitro NET formation by healthy neutrophils [53*, 151]. Importantly, NET levels were reduced to healthy donor levels in convalescent patients suggesting NETs resolve after COVID-19 [53*]. Lastly, several studies have found reduced levels of DNases in critically ill COVID-19 patients [149, 154]. Together these data indicate SARS-CoV-2 infection creates a hostile environment priming NET formation. Besides platelet-neutrophil interactions, other proposed mechanisms of NET formation in COVID-19 include direct interactions of SARS-CoV-2 with neutrophils [146, 155], complement-mediated NET formation [156, 157], circulating anti-phospholipid antibodies [158] or monocyte-driven hypercytokinemia [118, 159].

Importantly, early comparative studies have found four times more immunothrombotic occlusions containing NETs in COVID-19 cases compared to influenza pneumonia underscoring neutrophil-driven immunothrombosis as a key element of severe COVID-19 [160*]. Besides prothrombotic effects, the release of NETs in the lower respiratory tract of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients can trigger direct cytotoxic effects on the alveolar epithelium and endothelium resulting in loss of alveolar integrity [135, 137, 161–163]. This further contributes to the injurious vicious cycle of endotheliopathy induced coagulopathy and highlights the important therapeutic potential of targeting NETs in COVID-19 [164]. Interestingly, the corticosteroid dexamethasone [165] and the gout drug colchicine [166], which both were shown to reduce mortality in COVID-19 patients, are both NET inhibitors [167–169]. Furthermore, degrading NETs may represent an additional therapeutic option for NET-mediated lung injury in COVID-19 in the form of the FDA-approved Dornase alfa (recombinant DNase1) for which currently two COVID-19 clinical trials are underway (NCT04359654; NCT04409925). DNase1 was previously shown to reduce thrombosis and improve mortality in preclinical models of immunothrombosis by degrading NETs [137, 170–172]. Of-note, also low-molecular weight heparin degrades NETs and was shown to block COVID-19 plasma-induced NET formation in vitro [152]. Lastly, plasmapheresis might also devoid NET inducers circulating in COVID-19 patients; however, so far this has not been explored.

Conclusions

The cross-roads between infectious diseases and coagulation have become increasing intertwined during the COVID-19 pandemic. The combination of endothelial dysfunction, increased circulating procoagulant proteins, platelet hyperreactivity and altered inflammatory cell function appear to contribute to thrombotic complications in COVID-19 patients. Understanding the mechanisms behind COVID-19-induced coagulopathy will help develop novel therapies to treat immunothrombotic complications. In addition, future studies examining the acute versus chronic nature of the alterations in coagulation will have significant implications for transfusion medicine.

Keypoints.

COVID-19 patients are at increased risk for thrombotic complications.

COVID-19-specific coagulopathy and lung endotheliopathy contribute to prothrombotic changes via different mechanisms than sepsis-related disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Hyperreactive platelets and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to detrimental immunothrombosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Diana Lim for her excellent figure preparation.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the NIA and NINDS (K01AG059892 to R.A.C and Utah StrokeNET U24NS107228 to F.D.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *6.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary Embolism in Patients With COVID-19: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142:184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first study that reported increased PE events in COVID-19 patients compared to influenza patients.

- 7.Porfidia A, Valeriani E, Pola R, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;196:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsoukkary SS, Mostyka M, Dillard A, et al. Autopsy Findings in 32 Patients with COVID-19: A Single-Institution Experience. Pathobiology. 2021;88:56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang T, Lv B, Liu H, et al. Autopsy and statistical evidence of disturbed hemostasis progress in COVID-19: medical records from 407 patients. Thromb J. 2021;19:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lax SF, Skok K, Zechner P, et al. Pulmonary Arterial Thrombosis in COVID-19 With Fatal Outcome : Results From a Prospective, Single-Center, Clinicopathologic Case Series. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:350–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, et al. Postmortem examination of COVID-19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings in lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology. 2020;77:198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schurink B, Roos E, Radonic T, et al. Viral presence and immunopathology in patients with lethal COVID-19: a prospective autopsy cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e290–e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lutgehetmann M, et al. Autopsy Findings and Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **16.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discovered vascular features specific for SARS-CoV-2 infection, distinguishable from influenza. The observed alveolar capillary microvascular thrombosis highlight the need for tailored antithrombotic therapy in COVID-19.

- 17.Dolhnikoff M, Duarte-Neto AN, de Almeida Monteiro RA, et al. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1517–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariri LP, North CM, Shih AR, et al. Lung Histopathology in Coronavirus Disease 2019 as Compared With Severe Acute Respiratory Sydrome and H1N1 Influenza: A Systematic Review. Chest. 2021;159:73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill JR, Sheng ZM, Ely SF, et al. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauad T, Hajjar LA, Callegari GD, et al. Lung pathology in fatal novel human influenza A (H1N1) infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *21.Stals M, Grootenboers M, van Guldener C, et al. Risk of thrombotic complications in influenza versus COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis.n/a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the largest retrospective study comparing VTE rates in hospitalized influenza and COVID-19 patients. The high VTE risk in COVID-19 patients compared with influenza patients underscores the importance of appropriate anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients.

- 22.Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, et al. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs Patients With Influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-Up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thachil J, Juffermans NP, Ranucci M, et al. ISTH DIC subcommittee communication on anticoagulation in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2138–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan BK, Mainbourg S, Friggeri A, et al. Arterial and venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a study-level meta-analysis. Thorax. 2021:thoraxjnl-2020–215383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Edler C, Schroder AS, Aepfelbacher M, et al. Dying with SARS-CoV-2 infection-an autopsy study of the first consecutive 80 cases in Hamburg, Germany. Int J Legal Med. 2020;134:1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Authopsy report that discovered at least 10% of COVID-19 related deaths were due to thrombotic events.

- **27.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study was the first to discover SARS-CoV-2 viral particles in the pulmonary vascular endothelium and provided direct evidence for SARS-CoV-2 induced endothelial dysfunction and associated thromboinflammation.

- 28.Qanadli SD, Beigelman-Aubry C, Rotzinger DC. Vascular Changes Detected With Thoracic CT in Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Might Be Significant Determinants for Accurate Diagnosis and Optimal Patient Management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215:W15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Engineered Human Tissues Using Clinical-Grade Soluble Human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:905–913 e907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors provided direct evidence for infection of endothelial cells by SARS-CoV-2.

- **31.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280 e278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study was essential for the discovery of the mode of action of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Since SARS-CoV-2 also infects endothelial cells, ACE2 inhibitors could also be useful in preventing SARS-CoV-2 associated coagulopathy.

- 32.Tay MZ, Poh CM, Renia L, et al. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, et al. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:389–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rauch A, Dupont A, Goutay J, et al. Endotheliopathy Is Induced by Plasma From Critically Ill Patients and Associated With Organ Failure in Severe COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142:1881–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuang PD, Wang C, Zheng HP, et al. Comparison of the clinical and CT features between COVID-19 and H1N1 influenza pneumonia patients in Zhejiang, China. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouck EG, Denorme F, Holle LA, et al. COVID-19 and Sepsis Are Associated With Different Abnormalities in Plasma Procoagulant and Fibrinolytic Activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:401–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masi P, Hekimian G, Lejeune M, et al. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Is a Major Contributor to COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy: Insights From a Prospective, Single-Center Cohort Study. Circulation. 2020;142:611–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *38.Fraser DD, Patterson EK, Slessarev M, et al. Endothelial Injury and Glycocalyx Degradation in Critically Ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients: Implications for Microvascular Platelet Aggregation. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, et al. Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e575–e582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First study demonstrating that markers of endothelial dysfunction predict mortality and hospital discharge in COVID-19.

- 40.Rovas A, Osiaevi I, Buscher K, et al. Microvascular dysfunction in COVID-19: the MYSTIC study. Angiogenesis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassiliou AG, Keskinidou C, Jahaj E, et al. ICU Admission Levels of Endothelial Biomarkers as Predictors of Mortality in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients. Cells. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verhenne S, Denorme F, Libbrecht S, et al. Platelet-derived VWF is not essential for normal thrombosis and hemostasis but fosters ischemic stroke injury in mice. Blood. 2015;126:1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenting PJ, Christophe OD, Denis CV. von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: connecting the far ends. Blood. 2015;125:2019–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denorme F, Vanhoorelbeke K, De Meyer SF. von Willebrand Factor and Platelet Glycoprotein Ib: A Thromboinflammatory Axis in Stroke. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chauhan AK, Motto DG, Lamb CB, et al. Systemic antithrombotic effects of ADAMTS13. J Exp Med. 2006;203:767–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kremer Hovinga JA, Coppo P, Lammle B, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ladeira VS, Barbosa AR, Oliveira MM, et al. ADAMTS-13-VWF axis in sickle cell disease patients. Ann Hematol. 2021;100:375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levi M, Scully M, Singer M. The role of ADAMTS-13 in the coagulopathy of sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blasi A, von Meijenfeldt FA, Adelmeijer J, et al. In vitro hypercoagulability and ongoing in vivo activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis in COVID-19 patients on anticoagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2646–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Escher R, Breakey N, Lammle B. ADAMTS13 activity, von Willebrand factor, factor VIII and D-dimers in COVID-19 inpatients. Thromb Res. 2020;192:174–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Escher R, Breakey N, Lammle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res. 2020;190:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mancini I, Baronciani L, Artoni A, et al. The ADAMTS13-von Willebrand factor axis in COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *53.Middleton EA, He XY, Denorme F, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;136:1169–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study was the first to report on Neutrophil extracellular traps in lung fluid and lung histology specimens from COVID-19 patients.

- 54.Panigada M, Bottino N, Tagliabue P, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1738–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Philippe A, Chocron R, Gendron N, et al. Circulating Von Willebrand factor and high molecular weight multimers as markers of endothelial injury predict COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Angiogenesis. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first large clinical study highlighting the predictive value of high molecular weight VWF multimers for mortality and disease severity in COVID-19 patients and puts forward VWF as a therapeutic target for COVID-19 associated thrombosis.

- 56.Taus F, Salvagno G, Cane S, et al. Platelets Promote Thromboinflammation in SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:2975–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *57.Ward SE, Curley GF, Lavin M, et al. Von Willebrand factor propeptide in severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence of acute and sustained endothelial cell activation. Br J Haematol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found sustained endothelial cell activation in COVID-19 patients up to 3-weeks after hospital admission.

- 58.Bazzan M, Montaruli B, Sciascia S, et al. Low ADAMTS 13 plasma levels are predictors of mortality in COVID-19 patients. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:861–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandez-Perez MP, Aguila S, Reguilon-Gallego L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and von Willebrand factor are allies that negatively influence COVID-19 outcomes. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez Rodriguez M, Castro Quismondo N, Zafra Torres D, et al. Increased von Willebrand factor antigen and low ADAMTS13 activity are related to poor prognosis in covid-19 patients. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delrue M, Siguret V, Neuwirth M, et al. von Willebrand factor/ADAMTS13 axis and venous thromboembolism in moderate-to-severe COVID-19 patients. Br J Haematol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rauch A, Labreuche J, Lassalle F, et al. Coagulation biomarkers are independent predictors of increased oxygen requirements in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2942–2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ladikou EE, Sivaloganathan H, Milne KM, et al. Von Willebrand factor (vWF): marker of endothelial damage and thrombotic risk in COVID-19? Clin Med (Lond). 2020;20:e178–e182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doevelaar AAN, Bachmann M, Holzer B, et al. von Willebrand Factor Multimer Formation Contributes to Immunothrombosis in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Katneni UK, Alexaki A, Hunt RC, et al. Coagulopathy and Thrombosis as a Result of Severe COVID-19 Infection: A Microvascular Focus. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:1668–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lowenstein CJ, Solomon SD. Severe COVID-19 Is a Microvascular Disease. Circulation. 2020;142:1609–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Falter T, Rossmann H, Menge P, et al. No Evidence for Classic Thrombotic Microangiopathy in COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedrazzini G, Biasco L, Sulzer I, et al. Acquired intracoronary ADAMTS13 deficiency and VWF retention at sites of critical coronary stenosis in patients with STEMI. Blood. 2016;127:2934–2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, et al. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on the release and cleavage of the endothelial cell-derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers under flow. Blood. 2004;104:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frentzou GA, Bradford C, Harkness KA, et al. IL-1beta down-regulates ADAMTS-13 mRNA expression in cells of the central nervous system. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;46:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pinsky DJ, Naka Y, Liao H, et al. Hypoxia-induced exocytosis of endothelial cell Weibel-Palade bodies. A mechanism for rapid neutrophil recruitment after cardiac preservation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peyvandi F, Scully M, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. Caplacizumab for Acquired Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arulkumaran N, Thomas M, Brealey D, et al. Plasma exchange for COVID-19 thromboinflammatory disease. EJHaem. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramlall V, Thangaraj PM, Meydan C, et al. Immune complement and coagulation dysfunction in adverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2020;26:1609–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watanabe-Kusunoki K, Nakazawa D, Ishizu A, et al. Thrombomodulin as a Physiological Modulator of Intravascular Injury. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jin X, Duan Y, Bao T, et al. The values of coagulation function in COVID-19 patients. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cugno M, Meroni PL, Gualtierotti R, et al. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID-19 severity and activity. J Autoimmun. 2021;116:102560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guervilly C, Bonifay A, Burtey S, et al. Dissemination of extreme levels of extracellular vesicles: tissue factor activity in patients with severe COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5:628–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hardy M, Michaux I, Lessire S, et al. Prothrombotic disturbances of hemostasis of patients with severe COVID-19: A prospective longitudinal observational study. Thromb Res. 2021;197:20–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Henry BM, Cheruiyot I, Benoit JL, et al. Circulating Levels of Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Are Independent Predictors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity: A Prospective, Observational Study. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **82.Kang S, Tanaka T, Inoue H, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from vascular endothelial cells in cytokine release syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:22351–22356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provided mechanistic evidence for IL-6 induced coagulopathy in COVID-19 and demonstrated that targeting IL-6 is a valuable therapeutic option in COVID-19.

- 83.Nougier C, Benoit R, Simon M, et al. Hypofibrinolytic state and high thrombin generation may play a major role in SARS-COV2 associated thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2215–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Goshua G, et al. Circulating markers of angiogenesis and endotheliopathy in COVID-19. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020966547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zuo Y, Warnock M, Harbaugh A, et al. Plasma tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bachler M, Bosch J, Sturzel DP, et al. Impaired fibrinolysis in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Villa E, Critelli R, Lasagni S, et al. Dynamic angiopoietin-2 assessment predicts survival and chronic course in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5:662–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hermine O, Mariette X, Tharaux PL, et al. Effect of Tocilizumab vs Usual Care in Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19 and Moderate or Severe Pneumonia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perrone F, Piccirillo MC, Ascierto PA, et al. Tocilizumab for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. The single-arm TOCIVID-19 prospective trial. J Transl Med. 2020;18:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Salama C, Han J, Yau L, et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carty CL, Heagerty P, Heckbert SR, et al. Interaction between fibrinogen and IL-6 genetic variants and associations with cardiovascular disease risk in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Szotowski B, Antoniak S, Poller W, et al. Procoagulant soluble tissue factor is released from endothelial cells in response to inflammatory cytokines. Circ Res. 2005;96:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. D-dimer is Associated with Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Pooled Analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:876–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *95.von Meijenfeldt FA, Havervall S, Adelmeijer J, et al. Sustained prothrombotic changes in COVID-19 patients 4 months after hospital discharge. Blood Adv. 2021;5:756–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study was the first to demonstrate sustained prothrombotic changes in COVID-19 patients, warranting carefull monotoring of patients after hospital discharge.

- 96.Gando S, Levi M, Toh CH. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uaprasert N, Moonla C, Sosothikul D, et al. Systemic Coagulopathy in Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2021;27:1076029620987629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Merrill JT, Erkan D, Winakur J, et al. Emerging evidence of a COVID-19 thrombotic syndrome has treatment implications. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Di Micco P, Russo V, Carannante N, et al. Clotting Factors in COVID-19: Epidemiological Association and Prognostic Values in Different Clinical Presentations in an Italian Cohort. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fan BE, Ng J, Chan SSW, et al. COVID-19 associated coagulopathy in critically ill patients: A hypercoagulable state demonstrated by parameters of haemostasis and clot waveform analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu Y, Liao W, Wan L, et al. Correlation Between Relative Nasopharyngeal Virus RNA Load and Lymphocyte Count Disease Severity in Patients with COVID-19. Viral Immunol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di Dedda U, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1747–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhu J, Pang J, Ji P, et al. Coagulation dysfunction is associated with severity of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93:962–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **105.Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136:489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Critical study which discovered that besides thrombotic complications, bleedings are also common in COVID-19 patients. These results highlighted the need for clinical trials to determine the benefit of anticoagulant prophylaxis in COVID-19 patients.

- 106.Waite AAC, Hamilton DO, Pizzi R, et al. Hypercoagulopathy in Severe COVID-19: Implications for Acute Care. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:1654–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Capell WH, Barnathan ES, Piazza G, et al. Rationale and Design for the Study of Rivaroxaban to Reduce Thrombotic Events, Hospitalization and Death in Outpatients with COVID-19: the PREVENT-HD Study. Am Heart J. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Houston BL, Lawler PR, Goligher EC, et al. Anti-Thrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19 (ATTACC): Study design and methodology for an international, adaptive Bayesian randomized controlled trial. Clin Trials. 2020;17:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kharma N, Roehrig S, Shible AA, et al. Anticoagulation in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation suffering from COVID-19 disease, The ANTI-CO trial: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sivaloganathan H, Ladikou EE, Chevassut T. COVID-19 mortality in patients on anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:e192–e195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vanassche T, Engelen MM, Van Thillo Q, et al. A randomized, open-label, adaptive, proof-of-concept clinical trial of modulation of host thromboinflammatory response in patients with COVID-19: the DAWn-Antico study. Trials. 2020;21:1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rentsch CT, Beckman JA, Tomlinson L, et al. Early initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation for prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 mortality in patients admitted to hospital in the United States: cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients 2021. [Available from: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/full-dose-blood-thinners-decreased-need-life-support-improved-outcome-hospitalized-covid-19-patients].

- 114.Assinger A Platelets and infection - an emerging role of platelets in viral infection. Front Immunol. 2014;5:649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moreau D, Timsit JF, Vesin A, et al. Platelet count decline: an early prognostic marker in critically ill patients with prolonged ICU stays. Chest. 2007;131:1735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *117.Jiang SQ, Huang QF, Xie WM, et al. The association between severe COVID-19 and low platelet count: evidence from 31 observational studies involving 7613 participants. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:e29–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found an association between low platelet counts and severe COVID-19 and puts forward the importance of platelet count monitoring in COVID-19 patients.

- 118.Nicolai L, Leunig A, Brambs S, et al. Immunothrombotic Dysregulation in COVID-19 Pneumonia Is Associated With Respiratory Failure and Coagulopathy. Circulation. 2020;142:1176–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *119.Rapkiewicz AV, Mai X, Carsons SE, et al. Megakaryocytes and platelet-fibrin thrombi characterize multi-organ thrombosis at autopsy in COVID-19: A case series. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The observation of platelet-rich thrombi and megakaryocytes in multiple organs implicated an important role for platelets in the pathophysiology of COVID-19.

- *120.Manne BK, Denorme F, Middleton EA, et al. Platelet gene expression and function in patients with COVID-19. Blood. 2020;136:1317–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, substantional changes in the platelet gene expression pattern of patients with COVID-19 were found. These changes were irrespective of disease severity and unique to COVID-19. This study was also the first to report platelet hyperreactivity in COVID-19.

- 121.Cecchetti L, Tolley ND, Michetti N, et al. Megakaryocytes differentially sort mRNAs for matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors into platelets: a mechanism for regulating synthetic events. Blood. 2011;118:1903–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Portier I, Campbell RA. Role of Platelets in Detection and Regulation of Infection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *123.Zaid Y, Puhm F, Allaeys I, et al. Platelets Can Associate with SARS-Cov-2 RNA and Are Hyperactivated in COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; It was demonstrated that platelets contribute significantly to the cytokine storm associated with COVID-19.

- *124.Hottz ED, Azevedo-Quintanilha IG, Palhinha L, et al. Platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation trigger tissue factor expression in patients with severe COVID-19. Blood. 2020;136:1330–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found a critical link between platelets and immune cells contributing to disease outcomes in COVID-19.

- 125.Zhang S, Liu Y, Wang X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 binds platelet ACE2 to enhance thrombosis in COVID-19. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zaid Y, Guessous F, Puhm F, et al. Platelet reactivity to thrombin differs between patients with COVID-19 and those with ARDS unrelated to COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5:635–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chow JH, Khanna AK, Kethireddy S, et al. Aspirin Use is Associated with Decreased Mechanical Ventilation, ICU Admission, and In-Hospital Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Anesth Analg. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Meizlish ML, Goshua G, Liu Y, et al. Intermediate-dose anticoagulation, aspirin, and in-hospital mortality in COVID-19: a propensity score-matched analysis. Am J Hematol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Campbell RA, Boilard E, Rondina MT. Is there a role for the ACE2 receptor in SARS-CoV-2 interactions with platelets? J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Leopold V, Pereverzeva L, Schuurman AR, et al. Platelets are hyperactivated but show reduced glycoprotein VI reactivity in COVID-19 patients. Thromb Haemost. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Denorme F, Manne BK, Portier I, et al. COVID-19 patients exhibit reduced procoagulant platelet responses. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:3067–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Heemskerk JW, Mattheij NJ, Cosemans JM. Platelet-based coagulation: different populations, different functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:2–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Althaus K, Marini I, Zlamal J, et al. Antibody-induced procoagulant platelets in severe COVID-19 infection. Blood. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Combes AJ, Courau T, Kuhn NF, et al. Global absence and targeting of protective immune states in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Barnes BJ, Adrover JM, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2020;217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Li S, Jiang L, Li X, et al. Clinical and pathological investigation of patients with severe COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, et al. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2661–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16:887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15880–15885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sorvillo N, Cherpokova D, Martinod K, et al. Extracellular DNA NET-Works With Dire Consequences for Health. Circ Res. 2019;125:470–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Blasco A, Coronado MJ, Hernandez-Terciado F, et al. Assessment of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Coronary Thrombus of a Case Series of Patients With COVID-19 and Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Leppkes M, Knopf J, Naschberger E, et al. Vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. EBioMedicine. 2020;58:102925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Radermecker C, Detrembleur N, Guiot J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps infiltrate the lung airway, interstitial, and vascular compartments in severe COVID-19. J Exp Med. 2020;217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Veras FP, Pontelli MC, Silva CM, et al. SARS-CoV-2-triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J Exp Med. 2020;217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ouwendijk WJD, Raadsen MP, van Kampen JJA, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps persist at high levels in the lower respiratory tract of critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Infect Dis. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zuo Y, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gueant JL, Gueant-Rodriguez RM, Fromonot J, et al. Elastase and Exacerbation of Neutrophil Innate Immunity are Involved in Multi-Visceral Manifestations of COVID-19. Allergy. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *150.Ng H, Havervall S, Rosell A, et al. Circulating Markers of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Are of Prognostic Value in Patients With COVID-19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020:ATVBAHA120315267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this large retrospective study, several markers of NETs correlated with COVID-19 disease severity and outcomes. This observation puts forward the use of NET inhibiting strategies for the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

- 151.Strich JR, Ramos-Benitez MJ, Randazzo D, et al. Fostamatinib Inhibits Neutrophils Extracellular Traps Induced by COVID-19 Patient Plasma: A Potential Therapeutic. J Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Petito E, Falcinelli E, Paliani U, et al. Neutrophil more than platelet activation associates with thrombotic complications in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zuo Y, Zuo M, Yalavarthi S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and thrombosis in COVID-19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lee YY, Park HH, Park W, et al. Long-acting nanoparticulate DNase-1 for effective suppression of SARS-CoV-2-mediated neutrophil activities and cytokine storm. Biomaterials. 2021;267:120389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Arcanjo A, Logullo J, Menezes CCB, et al. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19). Sci Rep. 2020;10:19630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Busch MH, Timmermans S, Nagy M, et al. Neutrophils and Contact Activation of Coagulation as Potential Drivers of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142:1787–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Skendros P, Mitsios A, Chrysanthopoulou A, et al. Complement and tissue factor-enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID-19 immunothrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:6151–6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Zuo Y, Estes SK, Ali RA, et al. Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Vanderbeke L, Van Mol P, Van Herck Y, et al. Monocyte-driven atypical cytokine storm and aberrant neutrophil activation as key mediators of COVID-19 disease severity. 19 October 2020, PREPRINT:available at Research Square [ 10.21203/rs.21203.rs-60579/v21201]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *160.Nicolai L, Leunig A, Brambs S, et al. Vascular neutrophilic inflammation and immunothrombosis distinguish severe COVID-19 from influenza pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:574–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study further underlined the distinction between influenza and COVID-19 pneumonia. Highlighting the need for tailored treatment for COVID-19, targeting immunothrombosis.

- 161.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Folco EJ, Mawson TL, Vromman A, et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Induce Endothelial Cell Activation and Tissue Factor Production Through Interleukin-1alpha and Cathepsin G. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1901–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Laforge M, Elbim C, Frere C, et al. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:515–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Gupta AK, Joshi MB, Philippova M, et al. Activated endothelial cells induce neutrophil extracellular traps and are susceptible to NETosis-mediated cell death. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3193–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, et al. Effect of Dexamethasone on Days Alive and Ventilator-Free in Patients With Moderate or Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19: The CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1307–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Deftereos SG, Giannopoulos G, Vrachatis DA, et al. Effect of Colchicine vs Standard Care on Cardiac and Inflammatory Biomarkers and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019: The GRECCO-19 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2013136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Safi R, Kallas R, Bardawil T, et al. Neutrophils contribute to vasculitis by increased release of neutrophil extracellular traps in Behcet’s disease. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;92:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Vaidya K, Tucker B, Kurup R, et al. Colchicine Inhibits Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Wan T, Zhao Y, Fan F, et al. Dexamethasone Inhibits S. aureus-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Pathogen-Killing Mechanism, Possibly through Toll-Like Receptor Regulation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Chen G, Zhang D, Fuchs TA, et al. Heme-induced neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014;123:3818–3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Jimenez-Alcazar M, Rangaswamy C, Panda R, et al. Host DNases prevent vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps. Science. 2017;358:1202–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Thomas GM, Carbo C, Curtis BR, et al. Extracellular DNA traps are associated with the pathogenesis of TRALI in humans and mice. Blood. 2012;119:6335–6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]