Abstract

Background:

Early steroid withdrawal (ESW) is a viable maintenance immunosuppression strategy in low-risk kidney transplant recipients. A low panel reactive antibody (PRA) may indicate low-risk condition amenable to ESW. We aimed to identify the threshold value of PRA above which ESW may pose additional risk, and to compare the association of ESW with transplant outcomes across PRA strata.

Methods:

We studied 121,699 deceased-donor kidney-only recipients in 2002-2017 from SRTR. Using natural splines and ESW-PRA interaction terms, we explored how the associations of ESW with transplant outcomes change with increasing PRA values, and identified a threshold value for PRA. Then, we assessed whether PRA exceeding the threshold modified the associations of ESW with 1-year acute rejection, death-censored graft failure, and death.

Results:

The association of ESW with acute rejection exacerbated rapidly when PRA exceeded 60. Among PRA≤60 recipients, ESW was associated with a minor increase in rejection (aOR=1.001.051.10) and with a tendency of decreased graft failure (aHR=0.910.971.03). However, among PRA>60 recipients, ESW was associated with a substantial increase in rejection (aOR=1.191.271.36; interaction p<0.001) and with a tendency of increased graft failure (aHR=0.981.081.20; interaction p=0.028). The association of ESW with death was similar between PRA strata (PRA≤60, aHR=0.910.961.01; and PRA>60, aHR=0.900.991.09; interaction p=0.5).

Conclusions:

Our findings show that the association of ESW with transplant outcomes is less favorable in recipients with higher PRA, especially those with PRA>60, suggesting a possible role of PRA in the risk assessment for ESW.

INTRODUCTION

Landmark clinical trials have demonstrated that early steroid withdrawal (ESW) results in no or minimal increases in acute rejection and graft failure in low-risk kidney transplant (KT) recipients.1-10 Subsequent studies have also found the association of ESW with lower risk of steroid-related side effects such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and fracture.11-16 These findings have established ESW as a viable maintenance immunosuppression strategy in low-risk KT recipients.17 Over the last decade, approximately 30% of KT recipients has undergone ESW.18 Nonetheless, it remains unclear what characterizes the “low-risk” status that makes a KT recipient suitable for ESW.19,20

Panel reactive antibody (PRA), a key measure of immune sensitivity21,22 and a risk factor for acute rejection and graft failure,23-26 is seen as a potential indicator of suitability for ESW in scientific literature as well as clinical practice, although there is no profound evidence supporting this viewpoint.19 Virtually all of the landmark trials that shaped the current ESW practice have used PRA for restricting their study populations to low-risk recipients.1-7 The current clinical practice appears to follow suit; in our previous national registry analysis, KT recipients with higher PRA were less likely to undergo ESW.27 However, it has not been clearly shown whether PRA actually modifies the association of ESW with KT outcomes, or what value of PRA is the most appropriate threshold that classifies the recipients into those who are suitable for ESW versus those who are not.

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a national registry study to understand the role of PRA in assessing suitability for ESW. First, we aimed to identify the most appropriate threshold of PRA above which ESW may introduce additional risk of acute rejection or graft failure. Second, we assessed whether high- versus low-PRA, dichotomized at the identified threshold, modifies the association of ESW with acute rejection, graft failure, and death. Lastly, we examined whether PRA above the identified threshold is associated with the choice of ESW versus conventional steroid maintenance (CSM) across KT centers in the US.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services, provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. More details on the data are provided elsewhere.28

Study population

We studied all deceased-donor KT recipients from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2017. Recipients whose immunosuppression records could not be retrieved (n=2772; 1.7%), and those who received maintenance immunosuppressants other than tacrolimus and mycophenolate (n=28,136; 17.3%) were excluded. ESW was defined as withdrawal of steroid prior to the discharge from the KT admission; all other cases were defined as CSM. Since we did not have data on the exact date of steroid withdrawal, we excluded those who were not discharged within 30 days post-KT (n=1731; 1.3%) to exclude “late” steroid withdrawal cases (i.e., beyond the first few weeks post-KT) from our study.29 We also excluded those who died or developed graft failure before discharge (n=1044; 0.8%). Our primary exposure was peak PRA. PRA was measured periodically from placement on deceased-donor KT waitlist to receipt of KT, and reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. We used the maximum value of PRA to derive peak PRA. We excluded the recipients whose PRA records could not be retrieved (n=9896; 7.5%). Our final study population included 121,699 recipients.

Outcomes of interest

The KT outcomes we studied were acute rejection at 1 year post-KT, graft failure, and patient death. Acute rejection was collected by OPTN via periodic follow-up reports from KT centers (at 3-, 6-, and 12-month post-KT). However, the exact dates of acute rejection episodes are not collected by the reports. For this reason, we treated acute rejection during the first year post-KT as a binary outcome, in accordance with prior published methods for ascertaining acute rejections from the OPTN/SRTR registry data.28,30 Graft survival was defined as the time from KT to graft failure, censoring for death. Patient survival was defined as the time from transplant to death. Both outcomes were also censored at the end of follow up on December 31, 2017. Unlike acute rejection, the exact dates of graft failure and death were available in our data, beyond 1 year post-KT and until our end of follow-up on December 31, 2017. We treated graft failure and death as survival (time-to-event) outcomes. Graft failure and death were collected via multiple data sources by OPTN and SRTR, including follow-up reports from transplant centers, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ESRD Death Notification Form (CMS 2746), and the Social Security Death Master File.

Inverse probability treatment weights

We used inverse probability treatment weights (IPTW) to adjust for imbalances in covariables that may confound the association of ESW with KT outcomes. We estimated the propensity score using multi-level logistic regression that included recipient factors (age, sex, race, previous transplants, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, peak PRA, primary cause of end-stage renal disease, time on dialysis, serum albumin, peripheral vascular diseases, malignancy, type of health insurance, hepatitis C virus seropositivity, and cytomegalovirus seropositivity), donor factors (age, race, sex, body mass index, donation after cardiac death, diabetes, hypertension, death due to stroke, kidney on machine perfusion, terminal serum creatinine, hepatitis C virus seropositivity, and cytomegalovirus seropositivity and left versus right kidney), and procedural factors (HLA-A/B/DR matches, cold ischemic time, rejection during transplant admission, delayed graft function, post-KT length of stay, induction immunosuppression agent, and calendar year of KT). To account for practice variations across KT centers, this model included a random intercept term for each KT center and random slope terms for recipient age, peak PRA, previous transplants, post-KT length of stay, delayed graft function, and calendar year of KT; our exploratory analyses showed high center-level heterogeneity in the associations of these factors with the choice of ESW over CSM. We examined the distribution of the propensity scores (Figure S1) and excluded recipients with extreme propensity scores (below the 1st or above the 99th percentile).31

Identifying PRA threshold

To identify the appropriate threshold value of PRA above which ESW introduce additional risk, we created statistical models that included (1) a treatment indicator for ESW, (2) natural cubic spline terms of PRA, and (3) interaction terms between ESW and natural cubic spline terms of PRA. This approach allows us to examine how the association of ESW with KT outcomes change over increasing values of PRA, while allowing PRA to have a flexible, non-linear functional form. We conducted multi-level logistic regression to study acute rejection, and stratified Cox regression to study graft failure and death. Both regression approaches can account for center-level clustering. We controlled for confounders using IPTW as described above.

Association of ESW with KT outcomes in high- and low-PRA recipients

After determining a threshold value of PRA in the previous step, we aimed to formally assess whether high PRA (PRA value above the identified threshold) modifies the association of ESW with KT outcomes; i.e., whether the association of ESW with KT outcome in high-PRA recipients is meaningfully different from that in low-PRA recipients. We created statistical models that included (1) ESW, (2) a binary indicator of whether PRA exceeds the threshold, and (3) interaction terms between ESW and the binary indicator. We conducted multi-level logistic regression to study acute rejection, and stratified Cox regression to study graft failure and death. All models were weighted via IPTW as described above. Lastly, we conducted subgroup analyses by previous history of KT, recipient’s age, sex, and race, and HLA-A/B/DR mismatches.

Impact of high PRA on the choice between ESW and CSM

To examine whether high PRA (PRA value above the identified threshold) affects the choice between ESW and CSM across KT centers, we conducted multi-level logistic regression, with the choice of ESW as the outcome variable, and high PRA and its random slope term as the predictors, while adjusting for all other variables from the propensity score model. The random slope term represents the center-level variation in the association of high PRA with choosing ESW; we used the random slope term to estimate the center-specific odds ratio, i.e., the odds ratio estimated specifically at each center. This regression model estimates the association of high PRA with choosing ESW over the entire study population as well as specifically at each center.

Statistical analysis

Confidence intervals are reported as per the method of Louis and Zeger.32 Missing values were handled using multiple imputation. All analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1 and Stata 16.0/MP for Linux.

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 121,699 recipients included in our study, 33,456 (27.5%) underwent ESW. Compared to those who underwent CSM, those who underwent ESW were less likely to have peak PRA over 60 (16.1% vs. 24.3%), female sex (37.4% vs. 41.0%), or history of previous transplants (9.6% vs. 16.1%), but were more likely to be White (46.3% vs. 40.9%). Other characteristics were generally similar (Table 1). Additionally, the majority of the recipients continued to be on their discharge steroid regimen. We identified immunosuppression regimen at 1-year post-transplant in 91,356 (75.1%) recipients. Of them, 80,948 (88.6%) used the same steroid regimen at 1-year as at discharge.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics by Maintenance Steroid Regimen.

| ESW (n=33,456) |

CSM (n=88,243) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Recipient factors | ||

| Age | 54 (43, 63) | 52 (41, 62) |

| Female sex | 37.4% | 41.0% |

| Race | ||

| White | 46.3% | 40.9% |

| African American | 29.6% | 33.9% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15.5% | 16.9% |

| Other/multi-racial | 8.6% | 8.3% |

| Preemptive transplant | 11.0% | 9.8% |

| Years on dialysis | 3.2 (1.4, 5.4) | 3.4 (1.6, 5.7) |

| Primary cause of ESRD | ||

| Glomerulonephritis | 23.4% | 27.0% |

| Diabetes | 30.7% | 27.8% |

| Hypertension | 25.4% | 25.0% |

| Others | 20.5% | 20.2% |

| Peak PRA | ||

| 0 | 49.4% | 43.1% |

| 1-10 | 14.8% | 13.5% |

| 11-60 | 19.7% | 19.1% |

| 61-100 | 16.1% | 24.3% |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (23.8, 31.6) | 27.1 (23.5, 31.2) |

| Previous Transplants | 9.6% | 16.1% |

| Donor factors | ||

| Age | 39 (24, 51) | 39 (24, 50) |

| Female sex | 39.6% | 39.4% |

| Race | ||

| White | 70.0% | 67.4% |

| African American | 14.1% | 14.3% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13.0% | 14.9% |

| Other/multi-racial | 3.0% | 3.5% |

| Donation after cardiac death | 14.2% | 13.6% |

| Donor death due to stroke | 32.7% | 33.3% |

| Kidney on machine perfusion | 35.5% | 29.2% |

| Terminal serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) |

| Procedural factors | ||

| HLA-A mismatches | ||

| 0 | 15.2% | 16.4% |

| 1 | 36.8% | 37.0% |

| 2 | 48.0% | 46.5% |

| HLA-B mismatches | ||

| 0 | 11.3% | 12.6% |

| 1 | 23.9% | 24.8% |

| 2 | 64.8% | 62.6% |

| HLA-DR mismatches | ||

| 0 | 21.1% | 21.6% |

| 1 | 45.9% | 44.4% |

| 2 | 33.0% | 33.9% |

| Post-transplant length of stay (day) | 5 (4, 7) | 6 (4, 8) |

| Delayed graft function | 21.0% | 25.0% |

| Cold ischemic time (hour) | 17.0 (11.5, 23.3) | 16.5 (11.3, 22.1) |

ESW, early steroid withdrawal; CSM, conventional steroid maintenance; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PRA, panel reactive antibody; and HLA, human leukocyte antigen. Numbers are median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables.

Identifying PRA threshold

Across the entire population, ESW was associated with significantly increased acute rejection (aOR=1.061.111.15), but not with graft failure (aHR=0.940.991.05) or death (aHR=0.920.971.02). After adding ESW-PRA interaction terms, we observed that the associations of ESW with acute rejection and graft failure varied according to PRA. First, while ESW was associated with increased acute rejection across all values of PRA, the strength of the association intensified with increasing values of PRA, especially when PRA exceeded 60 (Figure 1a). Similarly, the association of ESW with graft failure also intensified with increasing PRA, but in a linear manner without a clear inflection point (Figure 1b). Lastly, we did not observe a clear trend how the association of ESW with death varied according to PRA (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Association of ESW with KT Outcomes by Different Values of PRA.

(a) Acute rejection, 1-year

(b) Graft failure, death-censored

(c) Death

ESW, early steroid withdrawal; KT, kidney transplant; and PRA, panel reactive antibody. Black lines represent the point estimates and gray lines represent piecewise 95% confidence intervals. Horizontal dashed lines at y=1 indicate null association.

Association of ESW with KT outcomes in high- and low-PRA recipients

Based on our findings described in the previous section, we stratified the study population into PRA>60 and PRA≤60. Using this PRA threshold, we observed statistically significant interactions of PRA and ESW in acute rejection and graft failure, but not in death (Table 2). Specifically, the association of ESW with acute rejection differed substantially between those with PRA≤60 versus PRA>60 (interaction p<0.001). ESW was associated with 1.001.051.10-fold the odds of acute rejection compared to CSM in PRA≤60 recipients (one-year incidence: 9.9% vs. 9.5%), and with 1.191.271.36-fold the odds in PRA>60 recipients (one-year incidence: 14.1% vs. 11.4%). Similarly, the PRA-ESW interaction was significant in graft failure (interaction p=0.028). ESW showed a tendency of correlation with decreased hazard of graft failure compared to CSM in PRA≤60 recipients (aHR=0.910.971.03; 5-year incidence: 12.9% vs. 12.4%), but with increased hazard in PRA>60 recipients (aHR=0.981.081.20; 5-year incidence: 16.0% vs. 13.0%) (Figure 2a). In contrast, we found no PRA-ESW interaction in the hazard of death (interaction p=0.5); the association of ESW with death was similar in PRA≤60 (aHR=0.910.961.01; 5-year incidence: 13.1% vs. 14.0%) and PRA>60 (aHR=0.900.991.09; 5-year incidence: 13.0% vs. 12.4%) recipients (Figure 2b).

Table 2.

Association of ESW with KT Outcomes in PRA Strata.

| Overall | PRA Strata | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRA≤60 | PRA>60 | Interaction P | ||

| Acute rejection, 1-year | 1.061.111.15 | 1.001.051.10 | 1.191.271.36 | <0.001 |

| Graft failure, death-censored | 0.940.991.05 | 0.910.971.03 | 0.981.081.20 | 0.028 |

| Death | 0.920.971.02 | 0.910.961.01 | 0.900.991.09 | 0.5 |

ESW, early steroid withdrawal; KT, kidney transplant; and PRA, panel reactive antibody. Estimates are adjusted odds ratios for acute rejection and adjusted hazard ratios for graft failure and death. Subscripts indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Cumulative Incidence of Graft Failure and Death by maintenance steroid regimen and PRA.

(a) Graft failure, death-censored

(b) Death

ESW, early steroid withdrawal; CSM, conventional steroid maintenance; KT, kidney transplant; and PRA, panel reactive antibody.

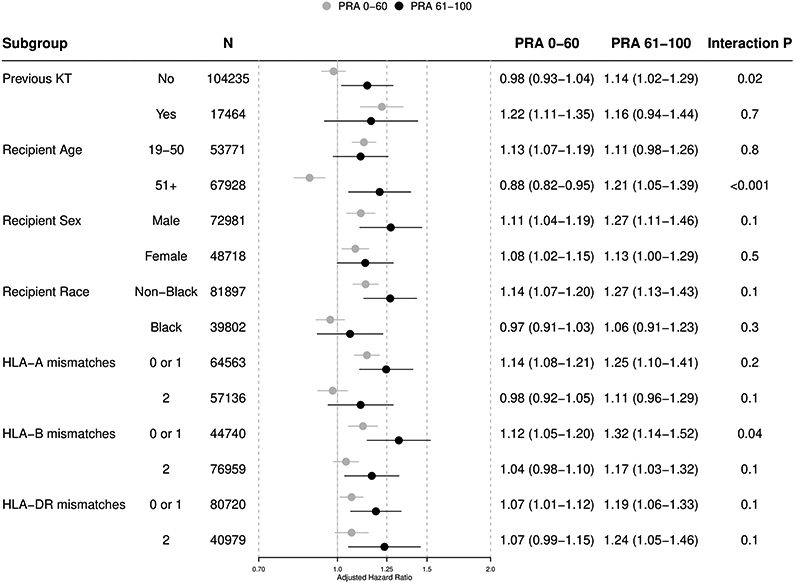

The impact of PRA on the association of ESW with clinical outcomes was generally similar across most of the subgroups, with few exceptions (Figure 3). For example, in recipients with previous KT, the association of ESW with acute rejection significantly varied by PRA (1.041.201.39 vs. 1.351.511.67; interaction p=0.006). However, in those without previous KT, such a variation was not observed (0.981.031.08 vs. 0.971.061.17; interaction p=0.5).

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses: Association of ESW with KT Outcomes by PRA Stratum.

(a) Acute rejection, 1-year

(b) Graft failure, death-censored

(c) Death

ESW, early steroid withdrawal; KT, kidney transplant; and PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Impact of high PRA on the choice between ESW and CSM

Across the entire population, PRA>60 was associated with significantly lower odds of choosing ESW over CSM after adjusting for other clinical factors (aOR=0.500.570.66). However, this association varied across KT centers (Figure 4). At some centers, PRA>60 was associated with substantially lower odds of choosing ESW (e.g., 21 [7.7%] centers had center-specific OR below 0.2.). On the other hand, PRA>60 seemed to have had little influence on the choice between ESW and CSM at other centers (e.g., 27 [9.9%] centers had center-specific OR between 0.9 and 1.1.). Furthermore, 8 (2.9%) centers were statistically significantly more likely to choose ESW in recipients with PRA>60, contrasting the practice at the majority of the centers. These findings underline the lack of consensus across KT centers in how the recipient’s PRA should inform the clinical decision between ESW and CSM.

Figure 4. Association of PRA>60 with the Choice of ESW at Each KT Center.

PRA, panel reactive antibody; ESW, early steroid withdrawal; KT, kidney transplant; and OR, odds ratio. Markers indicate adjusted OR of choosing ESW (vs. conventional steroid maintenance), estimated separately at each KT center. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Horizontal dashed line at y=1 indicates null association. Horizontal solid line indicates the adjusted OR over the entire population (aOR=0.500.570.66).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study of 121,699 deceased-donor KT recipients, we found that the associations of ESW with acute rejection and graft failure were more adverse in recipients with higher PRA. ESW was associated with increased acute rejection; and this association intensified with increasing PRA, especially when PRA exceeded 60. The association of ESW with graft failure also intensified with increasing PRA. After stratifying the study population by PRA of 60, we observed a statistically significant PRA-ESW interaction in acute rejection and graft failure. Compared to CSM, ESW was associated with only a 5% increase in the odds of acute rejection in the PRA≤60 stratum (aOR=1.001.051.10), but with a 27% increase in the PRA>60 stratum (aOR=1.191.271.36; interaction p<0.001). Similarly, ESW showed a tendency of correlation with decreased hazard of graft failure in the PRA≤60 stratum (aHR=0.910.971.03), but with increased hazard in the PRA>60 stratum (aHR=0.981.081.20; interaction p=0.028). These findings support that high PRA is an indicator of high immunological status that renders ESW unfavorable. We also found that, across the entire study population, PRA>60 was associated with lower odds of choosing ESW over CSM (aOR=0.500.570.66); however, the strength of this association varied across KT centers, underlining the lack of consensus on how PRA should inform the choice between ESW and CSM.

ESW was developed under the premise that certain low-risk recipients would not need life-long steroid therapy to keep the risk of acute rejection or graft failure sufficiently low.17,19,33-39 Given that PRA is a known risk factor for acute rejection and graft failure,23-25 using PRA to assess suitability for ESW appears to be a reasonable strategy. In fact, this strategy has been used by researchers and clinicians since the inception of ESW. The landmark clinical trials that demonstrated the safety of ESW in low-risk recipients have invariably restricted their study population to those with PRA below certain thresholds.1-9 Correspondingly, clinicians appear to interpret high PRA as a contraindication to ESW; our previous registry analysis have found that recipients with PRA>80 are less likely to undergo ESW (aOR=0.490.580.70).27

Nonetheless, there is limited clinical evidence to support the role of PRA in assessing suitability for ESW. In an OPTN analysis of deceased-donor KT recipients from 2000 to 2008, Sureshkumar et al.40 found that ESW was associated with increased death-censored graft failure among recipients with peak PRA>60 (aHR=1.011.191.41), but not among recipients with PRA≤60. A more recent SRTR analysis of deceased-donor KT recipients from 2000 to 2014, Vock and Matas41 found that ESW was suggestively, although not statistically significantly, associated with increased death-censored graft failure among recipients with PRA≥80 (aHR=0.951.121.33). While these results generally agree with our findings, neither study can determine whether PRA affects a KT recipient’s suitability for ESW, because the studies lacked formal interaction analyses between PRA and ESW. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted PRA-ESW interaction analyses and found that the associations of ESW with acute rejection and graft failure were meaningfully more adverse in high-PRA recipients than they were in low-PRA recipients (interaction p, <0.001 and 0.028, respectively). Unlike those from previous literature, our results constitute direct clinical evidence supporting that high PRA is a viable reason to avoid ESW.

Our study also aimed to identify the most appropriate threshold of PRA above which ESW may introduce excessive risk. Although the landmark clinical trials that established the current ESW practice are in common that they restricted their study populations to those with PRA below a certain threshold, the threshold value is largely inconsistent across the studies, ranging from 202 to 50.1,3,4,7 As described above, the registry studies on ESW in high-PRA recipients also used different thresholds; Sureshkumar et al.40 stratified at PRA of 60, and Vock and Matas41 did at 80. To our knowledge, none of these threshold values is supported by clinical evidence or biological theory. The findings from our cubic spline term analyses suggest that the association of ESW with acute rejection intensifies sharply with PRA exceeding 60, supporting the threshold of 60 in assessing suitability for ESW. It is important to note that this threshold is derived from the entire deceased donor KT recipient population. In clinical practice, this threshold may need to be adjusted for individual recipients since the benefit-risk balance of ESW would also depend on other immunological risk factors and predictors of steroid-related side effects.19,20

Our study has limitations. First, our study was observational and does not provide confirmatory evidence. To minimize this issue, we adjusted for a wide array of potential confounders using IPTW and accounted for center-level clustering in the choice between ESW and CSM as well as in KT outcomes. Similarly, the high-PRA recipients who underwent ESW might have been more favorable candidates for ESW than the high-PRA recipients who underwent CSM due to other clinical factors that were not included in our dataset. The impact of this confounding due to unmeasured factors is unknown. However, if the unmeasured factors were to result in an overestimation of the PRA-ESW interaction, the factors need to have motivated clinicians to choose ESW over CSM in high-PRA recipients, while being risk factors for acute rejection and graft failure; this situation does not appear very likely. Second, donor-specific antibody was not considered in our analyses as it was not available in the national registry data. The presence and title of donor-specific antibodies could have influenced the choice between ESW and CSM as well as the clinical outcomes. Given its role as an important mediator between PRA and transplant outcomes,42 future research is needed to examine donor-specific antibody and PRA jointly as indications for ESW/CSM. Lastly, our study design does not account for multi-way interactions, i.e., the interaction amongst ESW, PRA, and other clinical factors. It is still possible that other clinical factors can modify the PRA-ESW interaction or the PRA threshold of 60 as identified in our study. Our findings are derived from the entire deceased donor KT recipient population, and might need adjustments before being applied to certain subgroups.

In conclusion, our national registry analysis of 121,699 deceased-donor KT recipients has found that increasing PRA adversely modified the associations of ESW with acute rejection and graft failure, particularly when PRA exceeded 60. ESW was associated with only a minor increase in acute rejection and a suggestive decrease in graft failure among recipients with PRA≤60, but with a substantial increase in acute rejection and a suggestive increase in graft failure among those with PRA>60. Recipients with PRA>60 were less likely to undergo ESW; however, this practice appears to be inconsistent across KT centers. Our findings lend support to tailoring the choice between ESW and CSM according to the recipient’s PRA. PRA>60 appears to be a reasonable threshold above which ESW might become less favorable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Funding:

This work was supported by the American Society of Nephrology (Bae) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK120518, McAdams-DeMarco; K01DK101677, Massie; and K23DK115908, Garonzik-Wang) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K24AI144954, Segev).

Abbreviations:

- CSM

conventional steroid maintenance

- ESW

early steroid withdrawal

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- IPTW

inverse probability treatment weights

- KT

kidney transplantation

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Footnotes

Disclosure:

None.

References:

- 1.Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincenti F, Schena FP, Paraskevas S, et al. A randomized, multicenter study of steroid avoidance, early steroid withdrawal or standard steroid therapy in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(2):307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vítko S, Klinger M, Salmela K, et al. Two corticosteroid-free regimens-tacrolimus monotherapy after basiliximab administration and tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil-in comparison with a standard triple regimen in renal transplantation: results of the Atlas study. Transplantation. 2005;80(12):1734–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostaing L, Cantarovich D, Mourad G, et al. Corticosteroid-free immunosuppression with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and daclizumab induction in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79(7):807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincenti F, Monaco A, Grinyo J, et al. Multicenter randomized prospective trial of steroid withdrawal in renal transplant recipients receiving basiliximab, cyclosporine microemulsion and mycophenolate mofetil. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(3):306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laftavi MR, Stephan R, Stefanick B, et al. Randomized prospective trial of early steroid withdrawal compared with low-dose steroids in renal transplant recipients using serial protocol biopsies to assess efficacy and safety. Surgery. 2005;137(3):364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montagnino G, Sandrini S, Iorio B, et al. A randomized exploratory trial of steroid avoidance in renal transplant patients treated with everolimus and low-dose cyclosporine. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(2):707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haller MC, Royuela A, Nagler EV, et al. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online August 22, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pascual J, van Hooff JP, Salmela K, et al. Three-year observational follow-up of a multicenter, randomized trial on tacrolimus-based therapy with withdrawal of steroids or mycophenolate mofetil after renal transplant. Transplantation. 2006;82(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krämer BK, Klinger M, Vítko Š, et al. Tacrolimus-based, steroid-free regimens in renal transplantation: 3-year follow-up of the ATLAS trial. Transplant J. 2012;94(5):492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight SR, Morris PJ. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal after renal transplantation increases the risk of acute rejection but decreases cardiovascular risk. a meta-analysis: Transplantation. 2010;89(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rike AH, Mogilishetty G, Alloway RR, et al. Cardiovascular risk, cardiovascular events, and metabolic syndrome in renal transplantation: comparison of early steroid withdrawal and chronic steroids. Clin Transplant. 2008;22(2):229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikkel LE, Mohan S, Zhang A, et al. Reduced fracture risk with early corticosteroid withdrawal after kidney transplant. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(3):649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharnidharka VR, Schnitzler MA, Chen J, et al. Differential risks for adverse outcomes 3 years after kidney transplantation based on initial immunosuppression regimen: a national study. Transpl Int. 2016;29(11):1226–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar MSA, Heifets M, Moritz MJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of steroid withdrawal two days after kidney transplantation: analysis of results at three years. Transplantation. 2006;81(6):832–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luan FL, Steffick DE, Ojo AO. New-onset diabetes mellitus in kidney transplant recipients discharged on steroid-free immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2011;91(3):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2009;9 Suppl 3:S1–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2020;20 Suppl s1:20–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matas AJ, Gaston RS. Moving beyond minimization trials in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(12):2898–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae S, Garonzik Wang JM, Massie AB, et al. Early steroid withdrawal in deceased-donor kidney transplant recipients with delayed graft function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(1):175–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon RD, Fung JJ, Markus B, et al. The antibody crossmatch in liver transplantation. Surgery. 1986;100(4):705–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel R, Terasaki PI. Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1969;280(14):735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim WH, Chapman JR, Wong G. Peak panel reactive antibody, cancer, graft, and patient outcomes in kidney transplant recipients: Transplantation. 2015;99(5):1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KW, Kim SJ, Lee DS, et al. Effect of panel-reactive antibody positivity on graft rejection before or after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(7):2009–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Premasathian N, Panorchan K, Vongwiwatana A, et al. The effect of peak and current serum panel-reactive antibody on graft survival. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(7):2200–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. SRTR Risk Adjustment Model Documentation: Posttransplant Outcomes. Available at: https://www.srtr.org/reports-tools/posttransplant-outcomes/ Accessed on January 31, 2020.

- 27.Axelrod DA, Naik AS, Schnitzler MA, et al. National variation in use of immunosuppression for kidney transplantation: a call for evidence-based regimen selection. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(8):2453–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massie AB, Kuricka LM, Segev DL. Big data in organ transplantation: registries and administrative claims: big data in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1723–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascual J, Galeano C, Royuela A, et al. A systematic review on steroid withdrawal between 3 and 6 months after kidney transplantation: Transplantation. 2010;90(4):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lentine KL, Gheorghian A, Axelrod D, et al. The implications of acute rejection for allograft survival in contemporary U.S. kidney transplantation: Transplant J. 2012;94(4):369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals. Biostat Oxf Engl. 2009;10(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matas AJ, Kandaswamy R, Humar A, et al. Long-term immunosuppression, without maintenance prednisone, after kidney transplantation. Ann Surg. 2004;240(3):510–516; discussion 516-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprangers B, Vanrenterghem Y. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal after kidney transplantation: a balancing act. Transplantation. 2010;90(4):350–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprangers B, Kuypers DR, Vanrenterghem Y. Immunosuppression: does one regimen fit all? Transplantation. 2011;92(3):251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oettl T, Zuliani E, Gaspert A, et al. Late steroid withdrawal after abo blood group-incompatible living donor kidney transplantation: high rate of mild cellular rejection. Transplantation. 2010;89(6):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gloor J, Matas AJ. Steroid-free Maintenance Immunosuppression and ABO-incompatible Transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89(6):648–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luan FL, Schaubel DE, Zhang H, et al. Impact of immunosuppressive regimen on survival of kidney transplant recipients with hepatitis C: Transplantation. 2008;85(11):1601–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiner RW. Steroid Withdrawal in Kidney Transplantation: The Subgroup Fallacy. Transplantation. 2011;91(5):e27–e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sureshkumar KK, Marcus RJ, Chopra B. Role of steroid maintenance in sensitized kidney transplant recipients. World J Transplant. 2015;5(3):102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vock DM, Matas AJ. Rapid discontinuation of prednisone in kidney transplant recipients from at-risk subgroups: an OPTN/SRTR analysis. Transpl Int. Published online October 24, 2019:tri.13530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunn TB, Noreen H, Gillingham K, et al. Revisiting traditional risk factors for rejection and graft loss after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2132–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.