INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis and chronic beryllium disease (CBD) are similar granulomatous diseases that lack good diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. CBD is characterized by a beryllium-specific, cell-mediated immune response resulting in granulomatous lung disease, whereas sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease with unknown causal antigen affecting the lungs in over 90% cases.[1][2] Tissue biopsy is usually required for a definitive diagnosis of CBD and sarcoidosis. Both have genetic and environmental contributions, as well as variable clinical presentations.[3][4] Given these similarities, it is not surprising that misdiagnoses occur between the two diseases especially when an exposure to beryllium is either not known or linked to the diagnosis.[5][6]

Beryllium exposure is necessary for the development of CBD, which also depends on genetic susceptibility with HLA-DPB1 Glu69 being the most significant risk factor.[7][8] Beryllium sensitization (BeS), the immune response to beryllium, is measured by the blood beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT). About 20% of workers exposed to beryllium will develop BeS,[9] and 6–8% of those individuals per year progress to CBD.[10] There is currently no biomarker that distinguishes BeS from CBD.

Sarcoidosis is a highly protean disease: some individuals recover from a remitting course, while others develop severe disease necessitating life-long treatment. Attempts to accurately identify individuals who will progress have been unsuccessful resulting in inadequate monitoring and treatment.[11] A prognostic biomarker to identify those sarcoidosis cases at risk of progressive disease is much needed.

Our goal was to develop non-invasive, accurate biomarkers that diagnose and prognosticate CBD and sarcoidosis. Previous gene expression studies have demonstrated promising genomic biomarkers for CBD and sarcoidosis.[12][13][14][15] Based on these previous works, we selected 5 genes to validate as genomic biomarkers in our cohort of sarcoidosis, CBD, and BeS cases and controls. These genes include IFNγ, TNFα, RNase 3, CXCL9, and CD55. IFNγ and TNFα are strongly associated with a Th1 immune response in granulomatous diseases, therefore we anticipated these genes would be upregulated in our cases versus controls and in severe sarcoidosis disease.[16][17][18] In previous studies, Li et al. showed that RNase 3 was significantly upregulated in sarcoidosis compared to CBD;[15] additionally, upregulation of CXCL9 was correlated with disease severity in sarcoidosis and differentiates CBD from controls.[14][15] Finally CD55, a complement and T cell activation modulator, deficiency has been implicated in autoimmune diseases, and we anticipated expression would be lower in those with severe disease.[19][20] We hypothesized that differential gene expression of IFNγ, TNFα, RNase 3, CXCL9, and CD55 would function as disease specific diagnostic biomarkers between CBD and sarcoidosis, and prognostic biomarkers for severe phenotypes of sarcoidosis.

METHODS

Case Definitions and Study Populations

Whole blood samples from sarcoidosis, CBD, BeS and control subjects were obtained from a biorepository in the Division of Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences at National Jewish Health from the years 2009 to 2016. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the biorepository and database. Medical charts were reviewed to ensure eligibility and extract clinical data. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Jewish Health (HS 3212).1

CBD cases were defined by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) diagnostic criteria,[2] which includes a history of beryllium exposure, a positive blood and/or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) BeLPT and evidence of granulomatous inflammation on lung biopsy. A probable diagnosis of CBD consistent with ATS guidelines was accepted if tissue biopsy was not feasible.[2] BeS cases were defined by a history of beryllium exposure, positive blood BeLPTs with no evidence of granulomatous lung disease.

All sarcoidosis subjects met the ATS/European Respiratory Society (ERS) criteria[1] for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis as confirmed by tissue biopsy. Medical records for all cases were reviewed retrospectively. Pulmonary function tests, chest imaging and immunosuppressive treatment status were collected for all subjects up to 2 years from the blood sample date. Only cases on treatment at the time of the sample date were considered to be on treatment. Sarcoidosis cases were categorized as either non-progressive or progressive pulmonary phenotypes as adopted from Su et al.[14] The non-progressive phenotype was defined by a less than 10% decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) or forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) % predicted, a less than 15% decline in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) % predicted and stable chest imaging over the course of 2 years (±1 year) from the blood sample date. The progressive phenotype was defined as a decline of 10% or more in FVC or FEV1 % predicted; or a 15% or more decline in DLCO % predicted; or worsening chest imaging over the course of 2 years (±1 year) from the blood sample date. Cases were also defined as progressive if they required escalation of systemic immunosuppressive treatment (e.g. daily corticosteroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate, or anti-TNF therapy) within 2 years from the sample date independent of PFT data or radiology. Cases were categorized as undefined if there was not enough information to make a designation of progressive or non-progressive. Healthy controls had no evidence of beryllium health effects or sarcoidosis.

RNA and cDNA preparation

Whole blood RNA was extracted using the PAXgene RNA kit (PreAnalytiX, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). RNA yield and quality were measured using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Bioanalyzer 2100 capillary electrophoresis system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) targeting an RNA integrity score of 7 or greater. RNA was converted to cDNA using the TaqMan cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR)

TaqMan RT-qPCR was performed to determine relative gene expression levels of the target genes CD55, CXCL9, TNFα, IFNγ, and RNase 3 by using the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To ensure reproducibility, 15% of samples were run in duplicate. Relative expression values of target genes were calculated using the 2-ΔCt method relative to the housekeeping gene 18S rRNA, where Ct stands for cycle threshold.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and lung function data were presented as median (range) or percentage (number) values. Numerical data were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed rank test or Student’s t-test, while categorical data were analyzed using chi-squared tests. Differential gene expression between diagnostic groups was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for differential gene expression between non-progressive and progressive sarcoidosis. Gene expression levels were expressed as the relative mRNA expression level log2 transformed, and significant differences were defined as p values <0.05.

Logistic regression modeling was performed to determine the ability of gene expression levels to differentiate 1) CBD and sarcoidosis 2) CBD and BeS 3) sarcoidosis and controls 4) non-progressive and progressive sarcoidosis. Logistic regression modeling was performed controlling for race, age and sex in all models; systemic treatment was included in the CBD and sarcoidosis model. Systemic treatment was not controlled for in the other models because one of the compared groups had little or no individuals on treatment. We selected the logistic regression models that included genes with significant differential expression, and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each ROC curve. Based on the results of the ROC curves, a threshold was chosen to minimize misclassified cases. The misclassified cases were compared to those correctly classified on age, race, ethnicity, gender, gene expression levels, lung function parameters (FVC % predicted, FEV1 % predicted, and DLCO % predicted), extrapulmonary involvement (sarcoidosis only) and systemic treatment (sarcoidosis and CBD only).

RESULTS

Demographics

Baseline cohort characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sarcoidosis cases were significantly younger than CBD, BeS, and controls.[3] There were significantly more Black individuals in our sarcoidosis cases compared to CBD. There were also more female but fewer Hispanic sarcoidosis cases when compared to those with CBD, BeS, and controls. Sarcoidosis cases had significantly lower median FEV1% predicted when compared to BeS and CBD and were more likely to be on treatment than CBD. There was a higher percentage of sarcoidosis individuals who have ever smoked, but this was not a statistically significant difference when compared to the other diagnostic groups.

Table 1:

Baseline Cohort Characteristics

| CBD | BeS | Sarcoidosis | Controls | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects n | 132 | 109 | 99 | 97 | |

| Age Years | |||||

| Median (range) | 63.8(31–81)* | 62.9(30–84)‡ | 51.6(27–78)*†‡ | 65(26–84)† | p < 0.05*†‡ |

| Gender | |||||

| Percentage Males % (n) | 82(108)*§ | 77(84)‡ | 47(47)*†‡ | 71 (69)†§ | p < 0.05*†‡§ |

| Race | |||||

| Percentage White % (n) | 96(127) | 88(96) | 87(86) | 92(89) | |

| Percentage Black % (n) | 3(4)* | 8(9) | 12(12)* | 5(5) | p < 0.05* |

| Percentage Other % (n) | 0.8(1) | 4(4) | 1(1) | 3(3) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Percentage Hispanic % (n) | 10(13)* | 14(15)‡ | 2(2)*†‡ | 10(10)† | p < 0.05*†‡ |

| Systemic Immunosuppression at Time of Sample | |||||

| Percentage on Treatment % (n) | 7(9)* | N/A | 36(36)* | N/A | p < 0.05* |

| Median Pulmonary Function Tests Values | |||||

| FVC % predicted (range) | 88(51–131) | 87(56–123) | 89(36–137) | N/A | |

| FEV1 % predicted (range) | 88(42–136)* | 90(44–129)‡ | 85(33–121)*‡ | N/A | p < 0.05*‡ |

| DLCO % predicted (range) | 80(19–127) | 83(31–118) | 83(31–127) | N/A | |

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Ever Smoker % (n) | 53(70) | 50(55) | 39(38) | 57(52) | |

| Never Smoker % (n) | 47(62) | 50(54) | 61(60) | 43(39) | |

p<0.05 for the following comparisons:

sarcoidosis versus CBD

sarcoidosis versus controls

sarcoidosis versus BeS

CBD versus controls

There were no significant differences in demographics between the non-progressive and progressive phenotypes of sarcoidosis (Table 2). However, the progressive phenotype was significantly more likely to be on treatment and had significantly lower median DLCO % predicted than non-progressive phenotypes.

Table 2:

Sarcoidosis Phenotypes

| Non Progressive | Progressive | Undefined | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects n | 23 | 61 | 15 | |

| Age Years | ||||

| Median (range) | 54(28–78) | 51(27–71) | 53(34–78) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Percentage Males % (n) | 43(10) | 49(30) | 47(7) | |

| Race | ||||

| Percentage White % (n) | 91(21) | 82(50) | 100(15) | |

| Percentage Black % (n) | 9(2) | 16(10) | 0(0) | |

| Percentage Other % (n) | 0(0) | 2(1) | 0(0) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Percentage Hispanic % (n) | 4(1) | 0(0) | 7(1) | |

| Systemic Immunosuppression at Time of Sample | ||||

| Percentage on Treatment % (n) | 9(2)* | 54(33)*† | 7(1)† | p < 0.05*† |

| Median Pulmonary Function Testing Values | ||||

| FVC % predicted (range) | 91(65–113) | 87(47–137) | 83(36–108) | |

| FEV1 % predicted (range) | 91(50–118) | 81(33–121) | 87(45–114) | |

| DLCO % predicted (range) | 91(62–127)* | 81(31–126)*† | 92(68–103)† | p < 0.05*† |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Ever % (n) | 35(8) | 41(25) | ||

| Never % (n) | 65(15) | 59(36) | ||

p<0.05 for the following comparisons:

progressive versus non-progressive

Progressive versus undefined

Differential Gene expression

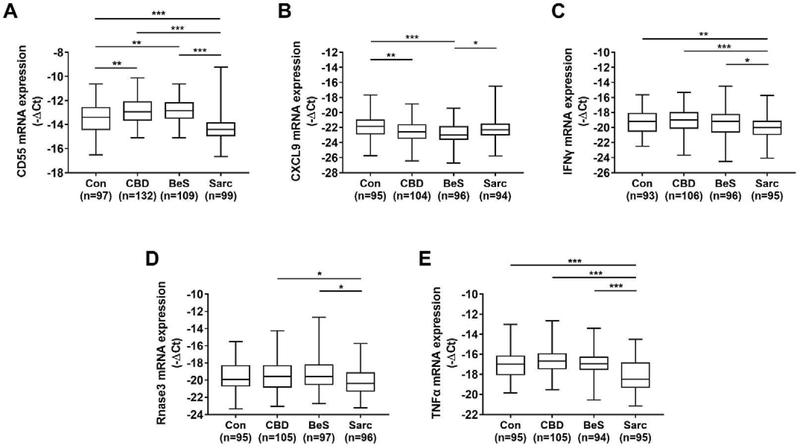

There was significant differential gene expression among the diagnostic groups for all target genes (Figure 1, see supplement Table A.1 for numerical values). For CD55, sarcoidosis had lower levels compared to controls, CBD and BeS; CBD and BeS had higher CD55 levels compared to controls. Sarcoidosis had higher CXCL9 levels compared to BeS while CBD and BeS had lower levels compared to controls. For IFNγ, sarcoidosis had lower levels compared to controls, CBD, and BeS. Sarcoidosis had lower RNase 3 levels than CBD and BeS. Sarcoidosis cases had lower TNFα levels than CBD, BeS and controls. The only significant differential gene expression in sarcoidosis phenotypes was that RNase 3 was upregulated in progressive compared to non-progressive sarcoidosis cases (data not shown).

Figure 1:

Differential Gene Expression Among Cases and Controls: Controls (Con), Chronic Beryllium Disease (CBD), Beryllium Sensitization (BeS), Sarcoidosis (Sarc). Boxplots show median, 25th and 75th percentile, and minimum and maximum gene expression levels for A) CD55 B) CXCL9 C) IFNγ D) RNase 3 E)TNFα. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Gene Expression Modeling

Logistic regression modeling was performed to differentiate CBD from sarcoidosis based on gene expression levels while controlling for sex, age, race and treatment. CD55 and TNFα were significantly upregulated in CBD compared to sarcoidosis, while CXCL9 was significantly downregulated (Figure 2A). The ROC curve of the logistic regression model with the combination of CD55, TNFα, and CXCL9 demonstrated a high discriminatory ability to distinguish between CBD and sarcoidosis with an AUC of 0.98 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2:

A) Logistic regression model including genes with significant differential expression and B) ROC curve demonstrating ability of CD55, TNFα, and CXCL9 to predict CBD versus sarcoidosis diagnosis w/ AUC of 0.98. TPR = true positive rate. FPR = false positive rate.

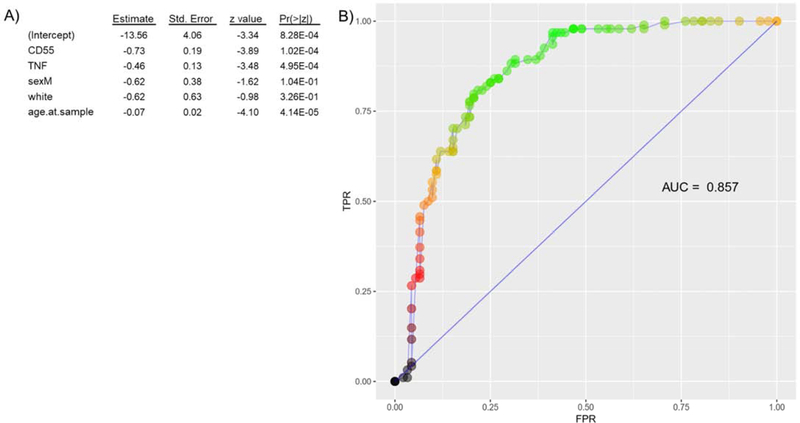

Models to differentiate between sarcoidosis and controls based on gene expression levels were controlled for sex, race and age. CD55 and TNFα were significantly downregulated in sarcoidosis compared to controls (Figure 3A). The ROC curve based on the logistic regression model with CD55 and TNFα expression levels shows a reasonable discriminatory ability of CD55 and TNFα expression levels to discriminate between sarcoidosis and controls with an AUC of 0.86 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3:

A) Logistic regression model including genes with significant differential expression and B) ROC curve demonstrating ability of CD55 and TNFα to predict sarcoidosis versus control diagnosis w/ AUC 0.86. TPR = true positive rate. FPR = false positive rate.

To differentiate between CBD and BeS modeling was performed based on gene expression levels while controlling for sex, race and age. TNFα was significantly upregulated in CBD compared to BeS, but there were no gene combinations that could discriminate CBD from BeS accurately (best AUC 0.62). Logistic regression modeling was also performed to differentiate between non-progressive and progressive based on gene expression levels controlling for sex, race and age. We did not control for treatment since only two non-progressive cases were on treatment. No combination of genes was able to accurately discriminate between sarcoidosis phenotypes (best AUC 0.67).

Cases Misclassified by Models

For the CBD and sarcoidosis ROC analysis, a classification threshold 0.6 was chosen resulting in a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 92.5%. Individuals with CBD misclassified as sarcoidosis (n=8) were younger, more likely to be female and had lower CD55 and TNFα levels compared to accurately classified CBD cases. Sarcoidosis cases misclassified as CBD (n=7) were older, more likely to be non-progressive, less likely to be on treatment or have extrapulmonary involvement and had significantly higher CD55 levels when compared to accurately classified sarcoidosis cases.

A classification threshold of 0.5 in the sarcoidosis and control analysis resulted in a sensitivity of 80.9% and specificity of 79.3%. Sarcoidosis cases misclassified as controls (n=18) were significantly older and had higher CD55 and TNFα levels compared to accurately classified sarcoidosis cases. Controls misclassified as sarcoidosis (n=19) were significantly younger, more likely to be female, and had lower CD55 and TNFα levels compared to accurately classified controls.

There were no PFT differences between accurately classified and misclassified cases.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that gene expression of CD55, TNFα and CXCL9 together can function as a highly accurate diagnostic biomarker between CBD and sarcoidosis. The ROC curve of these combined gene expression levels demonstrates high accuracy in discriminating CBD from sarcoidosis with an AUC of 0.98 and a sensitivity and specificity of 92%. We also showed that CD55 and TNFα expression levels could be used to differentiate between sarcoidosis and controls. The ROC curve demonstrates good accuracy with an AUC of 0.86. Unfortunately, we were unable to identify gene expression combinations that could differentiate between CBD and BeS or between progressive and non-progressive sarcoidosis phenotypes.

Misdiagnosis often occurs between CBD and sarcoidosis. A recent study from the Netherlands identified 3 out of 256 sarcoidosis cases in their cohort that were actually deemed to be CBD upon further investigation.[21] The BeLPT, which detects beryllium sensitization, can distinguish between the two diseases, however this specialized test is only available in a few certified labs across the United States and not routinely available in many countries outside the US. Additionally, while the specificity of the BeLPT is high at 96.9%, the sensitivity is lower at 68.3%.[22] Furthermore, if exposure to beryllium is not suspected or known, a BeLPT may not be obtained. In our granuloma clinic, we do see individuals with granulomatous disease and negative BeLPTs who have worked with beryllium and are diagnosed with sarcoidosis; it is possible these are actually cases of CBD that lack a BeLPT response. Additionally, there have also been individuals who have beryllium sensitization but who later go on to develop multi-organ disease more suggestive of a diagnosis of sarcoidosis than CBD. These scenarios further support an alternative diagnostic biomarker to distinguish CBD from sarcoidosis beyond the BeLPT. Distinguishing sarcoidosis from CBD is important as sarcoidosis often requires closer monitoring given the risk of extrapulmonary involvement and ongoing organ-specific follow-up. In addition, a diagnosis of a work-related condition like CBD may have implications for workplace restrictions/exposure mitigation, risk for other workers for disease, benefits and other compensation. A non-invasive biomarker used in conjunction with the BeLPT, when available, could reduce misdiagnosis.

In our logistic regression model, CD55 and TNFα were significantly upregulated in CBD compared to sarcoidosis. Reduced CD55 expression in sarcoidosis is consistent with studies implicating CD55 deficiency in immune diseases, although few studies have evaluated CD55 in granulomatous disease. CD55, also known as decay-accelerating factor, is a regulator protein of the complement system.[23] CD55 interferes with C3 and C5 convertases to suppress an overly exuberant complement response.[24][25] CD55 deficiency has been seen in human diseases such as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and bronchiolitis obliterans post-lung transplant.[23][26][27] In CD55 knockout mouse studies, CD55 deficiency results in an increased incidence of murine inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune encephalomyelitis.[19][20][24] In this study, sarcoidosis cases had greater disease severity, as evidenced by lower pulmonary function tests and need for systemic treatment, and were associated with lower expression of CD55 than in CBD. Interestingly, our sarcoidosis cases misdiagnosed as CBD generally had higher CD55 expression and less severe disease compared to accurately diagnosed sarcoidosis cases. There is also evidence in the literature that CD55 deficiency causes a hyper T cell response that could lead to the development of autoimmune disease.[24] Furthermore, recent studies show that CD55 stimulation induces differentiation of a discrete T regulatory type 1 cell population.[28] Sarcoidosis and CBD are both diseases marked by an inappropriately activated Th1 immune response and deficiency/dysfunction of T regulatory cells. While our study was not designed to investigate the mechanistic role of CD55 in sarcoidosis and CBD, it does suggest that CD55 may be an important mediator of the immune response and disease severity in these granulomatous diseases.

CXCL9 levels were upregulated in sarcoidosis compared to CBD cases, which is consistent with the literature that CXCL9 is associated with a greater Th1 response. CXCL9 is an IFNγ induced chemokine that is a ligand for the receptor CXCR3 found on Cd4+ Th1 and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.[29][30] Activation of the CXCR3 receptor appears to play a key role in transmigrating Th1 cells to sites of inflammation, and studies suggest blockade of the CXCR3 receptor inhibits pulmonary granulomatosis.[31][32]

Decreased TNFα gene expression in sarcoidosis compared to CBD cases was unexpected. TNFα is a cytokine primarily produced by activated macrophages and an important mediator of granuloma formation.[33][34][35] In the literature spontaneous TNFα release is higher in fresh BAL cells from sarcoidosis cases with progressive disease compared to those with stable disease and controls.[36] TNFα was also increased in beryllium stimulated cells from the BAL of CBD cases.[37] Since our sarcoidosis cases had more severe disease compared to CBD, we expected TNFα expression to be higher in our sarcoidosis group. The lower TNFα expression found instead may be explained by the possibility that the release of TNFα may be restricted to the site of inflammation in sarcoidosis. While our study focused on pulmonary sarcoidosis, we looked for gene expression in whole blood cells samples. A previous study showed elevated TNFα protein levels in active pulmonary sarcoidosis only in alveolar macrophages and not peripheral blood mononuclear cells.[38] There have been past studies showing elevated TNFα protein levels in serum for subgroups of severe pulmonary sarcoidosis cases,[39] although not all, while other studies have found no significant difference in serum TNFα levels between the sarcoidosis cases and controls.[40] These findings may be confounded by other factors besides phenotype, as one study found difference by ancestry, with White sarcoidosis patients demonstrating no significant difference in TNFα levels compare with matched controls, while Black patients had higher TNFα levels than matched controls.[41] In our study the vast majority of our subjects were White (91%) and only 7% were Black which may partially explain the low TNFα levels. In addition those studies measured TNFα protein and not gene expression levels as we did in this study. A future direction from our study would be to compare both TNFα protein and expression levels, although this is beyond the scope of this current study.

We also showed that CD55 and TNFα expression levels could be used as a biomarker to differentiate between sarcoidosis and controls. In our logistic regression model, CD55 and TNFα were significantly downregulated in sarcoidosis compared to healthy controls. These results raise the interesting possibility that CD55 and TNFα may be used as non-invasive biomarkers to diagnose sarcoidosis. We chose to differentiate sarcoidosis from healthy controls since many sarcoidosis cases present without symptoms or impairment and only radiographic abnormalities; thus those with asymptomatic/mild sarcoidosis cases includes a spectrum not too dissimilar to healthy individuals, especially those with post-infectious or non-specific adenopathy. Surprisingly, our logistic regression modeling did not demonstrate any genes that could differentiate CBD from BeS.

The lack of genes that could differentiate non-progressive from progressive pulmonary phenotypes of sarcoidosis was unexpected as we used the same phenotyping criteria as Su et al., who found that CXCL9 was significantly upregulated in progressive disease.[14] We did not use a prospective longitudinal data, which may have influenced the accuracy of our clinical phenotyping; 15 cases could not be categorized due to insufficient data and limited our sample size. However, these issues have been present in other studies also. A recent study has suggested that CXCL9 might be a marker of systemic organ involvement more so than severe disease, which could explain why we did not detect a significant difference between our progressive and non-progressive phenotypes.[42] Organ involvement was not a criteria in our phenotyping since we focused on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Consistent clinical phenotyping has been a challenge in all sarcoidosis research, and the quality of prognostic biomarkers depends on accurate and well-defined phenotypes. Given that TNFα levels have been higher in progressive sarcoidosis phenotypes, we did expect TNFα expression levels to be significantly different between sarcoidosis phenotypes; however, there was no difference in TNFα expression between phenotypes in our univariate or logistic regression analyses [36] However studying the cytokine gene expression in whole blood samples as opposed to BAL cells and the challenges of accurate phenotyping in sarcoidosis may have diminished any significant differences.

Increased IFNγ levels have been found in fresh BAL/serum cells from sarcoidosis cases[43][44] and in beryllium stimulated BAL cells from CBD cases.[45] While our univariate analysis did demonstrate differential IFNγ gene expression between different diagnostic groups, IFNγ expression levels were not able to accurately predict any diagnosis based on the ROC curves. While we did demonstrate a significant difference in RNase 3, also called the eosinophil cationic protein, between CBD versus sarcoidosis and non-progressive versus progressive sarcoidosis in our univariate analysis, these differences did not persist in our logistic regression modeling when controlled for race, sex, age and treatment in our outcome pairings.

Our study was a cross-sectional study and did not allow us to see how gene expression changes over time, which could have offered insight into the natural history of granulomatous disease. Instead, we were focused on developing a biomarker that could be used at any given point in the disease. Also, we did not have a validation cohort; alternatively, our study effectively functioned as a validation cohort as it was undertaken to confirm target genes selected from previous gene expression studies reported in the literature. Given that we selected our candidate genes from previous studies, our study was not designed to discover novel genomic biomarkers in sarcoidosis or CBD. We did not collect data on concomitant health conditions that may also influence gene expression of our candidate genes, especially other immune and inflammatory conditions. Finally, there is no standard approach to clinical phenotyping in sarcoidosis although we used definitions outlined in prior studies in which gene expression differences were noted. In this study, we did not have sufficient power to investigate gene expression differences between the fibrotic and non-fibrotic phenotypes, but we plan to study this phenotype along with multi-organ phenotypes in future studies.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study demonstrated the promise of differential gene expression to function as accurate diagnostic biomarkers in granulomatous diseases. We demonstrated that a panel of CD55, TNFα, and CXCL9 expression levels can distinguish between CBD and sarcoidosis with a high degree of accuracy. We also demonstrated that CD55 and TNFα expression levels can distinguish between sarcoidosis and healthy controls with a good degree of accuracy. We were not able to determine prognostic biomarkers for severe phenotypes of sarcoidosis, and it may be that there are different genes associated with disease severity than those studied in our paper. Our future directions include evaluating more genes of interest in BAL cell samples, comparing protein and gene expression levels and exploring more accurate methods of phenotyping sarcoidosis to continue developing genomic biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of CBD and sarcoidosis.

Highlights.

Genomic biomarkers used as a diagnostic tool in sarcoidosis and CBD

CD55, TNFα, and CXCL9 gene levels distinguish between sarcoidosis and CBD

CD55 and TNFα gene levels distinguish between sarcoidosis and controls

Acknowledgements

Nancy W. Lin: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original Draft Lisa A. Maier: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition Margaret M. Mroz: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing Sean Jacobson: Software, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing Kristyn MacPhail: Investigation, Resources Sucai Liu: Investigation, Resources Zhe Lei: Formal analysis, Visualization Briana Q. Barkes: Data Curation, Resources Tasha E. Fingerlin: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision Nabeel Hamzeh: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing Annyce S. Mayer: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing Clara I. Restrepo: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing Divya Chhabra: Formal analysis Ivana V. Yang: Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing, Supervision Li Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing -Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition

Funding Information

This work was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants:

1) 1R01ES025722-01A1

2) 1K01ES020857- 01

3) 1R01 HL140357-01A1

4) 1R01 ES023826-01A1

5) 1R01HL114587-01A1

The funding source had no involvement in the research or preparation of the article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary Declaration of Interest Statements

Dr. Yang reports consultant fees from Eleven P15, outside the submitted work.

Guarantor statement: LL has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures:

Dr. Ivana V. Yang reports consultant fees from Eleven P15, outside the submitted work.

Role of the sponsors: None

Abbreviations List

Area under the curve – AUC

Beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test – BeLPT

Beryllium sensitization – BeS

Bronchoalveolar lavage – BAL

Chronic beryllium disease – CBD

Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide – DLCO

Forced expiratory volume in one second – FEV1

Forced vital capacity – FVC

Receiver operating characteristic – ROC

References

- [1].Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, Bonham CA, Morgenthau AS, Patterson KC, Abston E, Bernstein RC, Blankstein R, Chen ES, Culver DA, Drake W, Drent M, Gerke AK, Ghobrial M, Govender P, Hamzeh N, James WE, Judson MA, Kellermeyer L, Knight S, Koth LL, Poletti V, Raman SV, Tukey MH, Westney GE, Baughman RP, Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201 (2020) e26–e51. https://doi.org/10-1164/rccm.202002-0251ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Balmes JR, Abraham JL, Dweik RA, Fireman E, Fontenot AP, Maier LA, Muller-Quernheim J, Ostiguy G, Pepper LD, Saltini C, Schuler CR, Takaro TK, Wambach PF, An official American Thoracic Society statement: Diagnosis and management of beryllium sensitivity and chronic beryllium disease, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190 (2014) e34–e59. https://doi.org/10-1164/rccm.201409-1722ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA, Sarcoidosis, N. Engl. J. Med. 336 (1997) 1224–1234. 10.1056/NEJM199704243361706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Newman LS, Lloyd J, Daniloff E, The natural history of beryllium sensitization and chronic beryllium disease, Environ. Health Perspect. 104 (1996) 937–943. 10.2307/3433014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Müller-Quernheim J, Gaede KI, Fireman E, Zissel G, Diagnoses of chronic beryllium disease within cohorts of sarcoidosis patients, Eur. Respir. J. 27 (2006) 1190–1195. 10.1183/09031936.06.00112205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fireman E LY, Haimsky E, Noiderfer M, Priel I, Misdiagnosis of sarcoidosis in patients with chronic beryllium disease, Sarcoidosis Vase Diffus. Lung Dis. 20 (2003) 144–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Richeldi L, Sorrentino R, Saltini C, HLA-DPB1 Glutamate 69: A Genetic Marker of Beryllium Disease, Science (80-.). 262 (1993) 242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maier LA, McGrath DS, Sato H, Lympany P, Welsh K, du Bois R, Silveira L, Fontenot AP, Sawyer RT, Wilcox E, Newman LS, Influence of MHC CLASS II in Susceptibility to Beryllium Sensitization and Chronic Beryllium Disease, J. Immunol. 171 (2003) 6910–6918. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kreiss K, Mroz MM, Zhen B, Wiedemann H, Barna B, Risks of beryllium disease related to work processes at a metal, alloy, and oxide production plant, Occup. Environ. Med. 54 (1997) 605–612. 10.1136/oem.54.8.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Newman LS, Mroz MM, Balkissoon R, Maier LA, Beryllium Sensitization Progresses to Chronic Beryllium Disease, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171 (2004) 54–60. 10.1164/rccm.200402-190oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Culver DA, Baughman RP, It’s time to evolve from Scadding: Phenotyping sarcoidosis, Eur. Respir. J. 51 (2018). 10.1183/13993003.00050-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Crouser ED, Culver DA, Knox KS, Julian MW, Shao G, Abraham S, Liyanarachchi S, Macre JE, Wewers MD, Gavrilin MA, Ross P, Abbas A, Eng C, Gene Expression Profiling Identifies MMP-12 and ADAMDEC1 as Potential Pathogenic Mediators of Pulmonary Sarcoidosis, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179 (2009) 929–938. 10.1164/rccm.200803-490OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lockstone HE, Sanderson S, Kulakova N, Baban D, Leonard A, Kok WL, McGowan S, McMichael AJ, Ho LP, Gene Set Analysis of Lung Samples Provides Insight into Pathogenesis of Progressive, Fibrotic Pulmonary Sarcoidosis, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181 (2010) 1367–1375. 10.1164/rccm.200912-1855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Su R, Li MM, Bhakta NR, Solberg OD, Darnell EPB, Ramstein J, Garudadri S, Ho M, Woodruff PG, Koth LL, Longitudinal analysis of sarcoidosis blood transcriptomic signatures and disease outcomes, Eur. Respir. J. 44 (2014) 985–993. 10.1183/09031936.00039714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li L, Silveira LJ, Hamzeh N, Gillespie M, Mroz PM, Mayer AS, Fingerlin TE, Maier LA, Beryllium-induced lung disease exhibits expression profiles similar to sarcoidosis, Eur. Respir. J. 47 (2016) 1797–808. 10.1183/13993003.01469-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moller DR, Forman JD, Liu MC, Noble PW, Greenlee BM, Vyas P, Holden DA, Forrester JM, Lazarus A, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Karp C, Enhanced expression of IL-12 associated with Th1 cytokine profiles in active pulmonary sarcoidosis., J. Immunol. 156 (1996) 4952–60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8648147 (accessed January 8, 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Baughman RP, Strohofer SA, Buchsbaum J, Lower EE, Release of tumor necrosis factor by alveolar macrophages of patients with sarcoidosis, J. Lab. Clin. Med. 115 (1990) 36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maier LA, Sawyer RT, Tinkle SS, Kittle LA, Barker EA, Balkissoon R, Rose C, Newman LS, IL-4 fails to regulate in vitro beryllium-induced cytokines in berylliosis., Eur. Respir. J. 17 (2001) 403–15. 10.1183/09031936.01.17304030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Miwa T, Maldonado MA, Zhou L, Sun X, Luo HY, Cai D, Werth VP, Madaio MP, Eisenberg RA, Song W-C, Deletion of decay-accelerating factor (CD55) exacerbates autoimmune disease development in MRL/lpr mice., Am. J. Pathol. 161 (2002) 1077–86. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64268-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lin F, Spencer D, Hatala DA, Levine AD, Medof ME, Decay-Accelerating Factor Deficiency Increases Susceptibility to Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis: Role for Complement in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, J. Immunol. 172 (2004) 3836–3841. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Beijer E, Meek B, Bossuyt X, Bossuyt X, Peters S, Vermeulen RCH, Kromhout H, Veltkamp M, Veltkamp M, Immunoreactivity to metal and silica associates with sarcoidosis in Dutch patients, Respir. Res. 21 (2020) 1–8. 10.1186/s12931-020-01409-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stange AW, Furman FJ, Hilmas DE, The beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test: Relevant issues in beryllium health surveillance, Am. J. Ind. Med. 46 (2004) 453–462. 10.1002/ajim.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pandya PH, Wilkes DS, Complement System in Lung Disease, Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 51 (2014) 467–473. 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0485TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu J, Miwa T, Hilliard B, Chen Y, Lambris JD, Wells AD, Song WC, The complement inhibitory protein DAF (CD55) suppresses T cell immunity in vivo, J. Exp. Med. 201 (2005) 567–577. 10.1084/jem.20040863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Miwa T, Song WC, Membrane complement regulatory proteins: Insight from animal studies and relevance to human diseases, Int. Immunopharmacol. 1 (2001) 445–459. 10.1016/S1567-5769(00)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nicholson Weller A, March JP, Rosenfeld SI, Austen KF, Affected erythrocytes of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria are deficient in the complement regulatory protein, decay accelerating factor, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 80 (1983) 5066–5070. 10.1073/pnas.80.16.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].et al. Suzuki H, Lasbury ME, Fan L, Role of Complement Activation in Obliterative Bronchiolitis Post Lung Transplantation, J Immunol. 191 (2013) 4431–4440. 10.1038/jid.2014.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sutavani RV, Bradley RG, Ramage JM, Jackson AM, Durrant LG, Spendlove I, CD55 Costimulation Induces Differentiation of a Discrete T Regulatory Type 1 Cell Population with a Stable Phenotype, J. Immunol. 191 (2013) 5895–5903. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Groom AJR, Luster, CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions, 89 (2011) 207–215. 10.1038/icb.2010.158.CXCR3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].et al. Loetscher M, Gerber B, Loetscher P, Chemokine Receptor Specific for IP10 and Mig: Structure, Function, and Expression in Activated T-Lymphocytes, J Exp Med. 184 (1996) 963–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xie JH, Nomura N, Lu M, Chen S, Koch GE, Weng Y, Rosa R, Di Salvo J, Mudgett J, Peterson LB, Wicker LS, Demartino JA, T. Cxcr-positive, Antibody-mediated blockade of the CXCR3 chemokine receptor results in diminished recruitment of T helper 1 cells into sites of inflammation, J Leukoc Biol. 73 (2003) 771–780. 10.1189/jlb.1102573.Journal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kishi J, Nishioka Y, Kuwahara T, Kakiuchi S, Azuma M, Aono Y, Makino H, Kinoshita K, Kishi M, Batmunkh R, Uehara H, Izumi K, Sone S, Blockade of Th1 chemokine receptors ameliorates pulmonary granulomatosis in mice, Eur. Respir. J. 38 (2011) 415–424. 10.1183/09031936.00070610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dai H, Guzman J, Chen B, Costabel U, Production of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors and tumor necrosis factor-α by alveolar macrophages in sarcoidosis and extrinsic allergic alveolitis, Chest. 127 (2005) 251–256. 10.1378/chest.127.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lukacs NW, Chensue SW, Strieter RM, Warmington K, Kunkel SL, Inflammatory granuloma formation is mediated by TNF-alpha-inducible intercellular adhesion molecule-1., J. Immunol. 152 (1994) 5883–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7911491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bachwich PR, Lynch JP, Larrick J, Spengler M, Kunkel SL, Tumor necrosis factor production by human sarcoid alveolar macrophages, Am. J. Pathol. 125 (1986) 421–425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ziegenhagen MW, Müller-Quernheim J, The cytokine network in sarcoidosis and its clinical relevance, J. Intern. Med. 253 (2003) 18–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tinkle SS, Newman LS, Beryllium-stimulated release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and their soluble receptors in chronic beryllium disease, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156 (1997) 1884–1891. 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9610040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muller-Quernheim J, Pfeifer S, Mannel D, Strausz J, Ferlinz R, Lung-restricted activation of the alveolar macrophage/monocyte system in pulmonary sarcoidosis, Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 145 (1992) 187–192. 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Loza MJ, Brodmerkel C, Du Bois RM, Judson MA, Costabel U, Drent M, Kavuru M, Flavin S, Lo KH, Barnathan ES, Baughman RP, Inflammatory profile and response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis, Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18 (2011) 931–939. 10.1128/CVI.00337-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Beirne P, Pantelidis P, Charles P, Wells AU, Abraham DJ, Denton CP, Welsh KI, Shah PL, Du Boise RM, Kelleher P, Multiplex immune serum biomarker profiling in sarcoidosis and systemic sclerosis, Eur. Respir. J 34 (2009) 1376–1382. 10.1183/09031936.00028209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sweiss NJ, Zhang W, Franek BS, Kariuki SN, Moller DR, Patterson KC, Bennett P, Girijala LR, Nair V, Baughman RP, Garcia JGN, Niewold TB, Linkage of type i interferon activity and TNF-alpha levels in serum with sarcoidosis manifestations and ancestry, PLoS One. 6 (2011) 1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arger NK, Ho ME, Allen IE, Benn BS, Woodruff PG, Koth LL, CXCL9 and CXCL10 are differentially associated with systemic organ involvement and pulmonary disease severity in sarcoidosis, Respir. Med 161 (2020) 105822. 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Robinson BWS, McLemore TL, Crystal RG, Gamma interferon is spontaneously released by alveolar macrophages and lung T lymphocytes in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis, J. Clin. Invest. 75 (1985) 1488–1495. 10.1172/JCI111852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Prior C, Haslam PL, Increased levels of serum interferon-gamma in pulmonary sarcoidosis and relationship with response to corticosteroid therapy, Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 143 (1991) 53–60. 10.1164/ajrccm/143.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tinkle SS, Schwitters PW, Newman LS, Cytokine production by bronchoalveolar lavage cells in chronic beryllium disease, Environ. Health Perspect. 104 (1996) 969–971. 10.2307/3433019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]