Abstract

Purpose(s)

To evaluate the relationship of men’s dietary patterns with outcomes of in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study including 231 couples with 407 IVF cycles, presented at an academic fertility center from April 2007 to April 2018. We assessed diet with a validated food frequency questionnaire and identified Dietary Pattern 1 and Dietary Pattern 2 using principal component analysis. We evaluated adjusted probability of IVF outcomes across the quartiles of the adherence to two dietary patterns by generalized linear mixed models.

Results

Men had a median age of 36.8 years and BMI of 26.9 kg/m2. Women’s median age and BMI were 35.0 years and 23.1 kg/m2, respectively. Adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 (rPearson=0.44) and Dietary Pattern 2 (rPearson=0.54) was positively correlated within couples. Adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 was positively associated with sperm concentration. A 1-unit increase in this pattern was associated with a 13.33 (0.71–25.96) million/mL higher sperm concentration. However, neither Dietary Pattern 1 nor Dietary Pattern 2 was associated with fertilization, implantation, clinical pregnancy, or live birth probabilities.

Conclusions

Data-derived dietary patterns were associated with semen quality but unrelated to the probability of successful IVF outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-021-02251-9.

Keywords: Dietary pattern, Male subfertility, In vitro fertilization, Probability of live birth

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse, is a worldwide issue [1] affecting 15% of reproductive age couples [2]. Male factor is one of the most common causes of infertility and male infertility evaluation is important not only for defining infertility treatment strategies but also for men’s health itself as male infertility could be a predictor of future morbidity [3]. Contributing factors to male infertility are various: genetic factors, environmental factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, psychological stress, substance abuse, exercise, and comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity [4–10].

Previous epidemiological work suggests that paternal dietary patterns associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions [11–13], such as the Mediterranean diet and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet may be positively associated with semen quality. On the other hand, dietary patterns favoring intakes of red and processed meats, animal fat, refined grains, and sweets—which have been related to a higher risk of non-communicable chronic diseases [14]—may affect negatively semen quality [15–20]. However, semen parameters are not perfectly correlated with a couple’s fertility [21, 22]. Moreover, while some evidence suggests men’s diet may influence a couple’s fertility [23–25], data on the extent to which men’s diet could impact fertility in couples trying to conceive naturally or with medical assistance remains scarce. To address this important question, we evaluated the association between adherence to men’s dietary patterns identified in the study population using a data-driven approach and outcomes of infertility treatment with in vitro fertilization (IVF). We hypothesized that couples with a male partner with greater adherence to dietary patterns consistent with diets associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases would have higher clinical pregnancy and live birth rates during the course of infertility treatment with IVF.

Materials and methods

Study population

Couples presenting for infertility evaluation and treatment to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Fertility Center were invited to enroll in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study. Established in 2004, this cohort study investigates the effect of environmental and dietary factors on fertility and pregnancy outcomes; study design has been described in detail elsewhere [26]. Men (ages 18–55) and women (ages 18–45) presenting to the MGH Fertility Center planning to use their own gametes for infertility treatment are eligible to join the study. Approximately 65% of women and 45% of men who were eligible, participated in the study [26]. All study participants completed several study questionnaires which included demographics, medical, reproductive, and occupational history, and lifestyle, and underwent an anthropometric evaluation after providing written consent. Diet assessments were introduced in April 2007. Couples were encouraged but not required to join as a couple. This study included all participants who joined as a couple, the male partner completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and his female partner started at least one IVF cycle by April 2018. Among the 377 couples who joined the study during this period, 146 men did not complete diet assessments leaving 231 couples eligible for the current study. Baseline demographic and reproductive data of participants included in the study did not differ substantially from those excluded (Supplemental table 1). The study was approved by the institutional review board of both MGH and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Dietary assessment and identification of dietary patterns

Diet was assessed using an extensively validated FFQ [27–35]. Participants were asked to report how often, on average, they consumed each of the 131 foods and beverages in the questionnaire during the previous year, with frequency choices ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “six or more times per day.” Individual food items were grouped into 42 pre-defined food groups based on those proposed by Hu and colleagues [36]. We used these 42 food groups to identify underlying dietary patterns in the study population using principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation in order to achieve a simpler and more interpretable structure. The number of factors retained was determined based on Eigenvalues, the scree plot, and interpretability of the resulting factors.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the probability of live birth per initiated treatment cycle. Live birth was defined as the birth of a neonate at or after 24 weeks of gestation. Secondary outcomes were fertilization rate, the probability of implantation, and clinical pregnancy. Fertilization rate was defined as the number of two pronuclei embryos divided by the number of metaphase II oocytes and evaluated by mode of insemination (conventional insemination or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)). Successful implantation was defined as an elevation of serum β-hCG level greater than 6 mIU/mL measured at approximately 2 weeks after embryo transfer. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of an intrauterine gestational sac on ultrasound at 6 gestational weeks.

Semen parameters assessment

Secondary outcomes included conventional semen parameters (ejaculate volume, total sperm count, sperm concentration, total motility, progressive motility, and the percentage of sperm normal morphology). We used data from semen samples collected for diagnostic purposes as well as pre-processing data for samples collected for treatment purposes. Men provided semen specimens on-site via masturbation and completed abstinence time questionnaires. A 48-h abstinence time before sample collection was recommended. For this study, we included all semen sample data even if the abstinence time was not adhered to. Semen parameters were assessed based on the 2010 WHO manual guideline [37]. Semen samples were inspected after 30-min liquefaction on a 37 °C incubator. Ejaculate volume was calculated from sample weight, assuming a semen density of 1g/mL. Sperm concentration and motility were assessed by a computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) system (10HTM-IVOS, Hamilton-Thorne Research, Beverly, MA) [38]. Motile spermatozoa were evaluated as total motility (progressive motility + non-progressive motility), progressive motility, non-progressive motility, and immotile sperm [37]. Total sperm count (million/ejaculate) referred to total number of spermatozoa in the entire ejaculate which was calculated by multiplying sperm concentration by ejaculated volume. Sperm morphology (% normal) was assessed on two slides per specimen (with a minimum of 200 cells assessed per slide) via a microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with an oil-immersion ×100 magnification. Then, men were dichotomized as having normal or below normal morphology according to Strict Kruger scoring criteria [39].

Statistical analysis

Men were categorized into quartiles according to adherence to PCA-derived dietary patterns. We first examined differences in demographic, nutritional and reproductive characteristics, and semen parameters by quartile of adherence to dietary patterns using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Chi-square test was used for evaluating differences across categories of primary infertility diagnosis and initial stimulation protocol as the Fisher’s test did not run with these two variables. We investigated the relationship between two PCA-derived patterns and semen quality using linear mixed models with random intercepts, to account for multiple IVF cycles per couple, adjusting men’s age, total calorie intake, body mass index (BMI), race, smoking status, education level, and physical activity. The association of adherence to PCA-derived dietary patterns with IVF outcomes was examined using generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts, to account for multiple IVF cycles per couple, while adjusting for potential confounders. We used population marginal means to present results as probabilities and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) adjusted for the covariates at their average levels for continuous variables and weighted average level of categorical variable in the model [40]. Tests for linear trend were conducted by modeling quartiles of adherence as a continuous variable. Confounding was evaluated using prior scientific knowledge and differences in baseline patient characteristics by dietary pattern adherence. The initial multivariable-adjusted model included terms for men’s age and total calorie intake. The second model included additional terms for men’s BMI, race, smoking status, education level, and physical activity, as well as women’s age and BMI, the couples’ primary infertility diagnosis, treatment protocol, and indicators for missing covariate data. The third model included all variables of the second model and terms for women’s adherence to the two dietary patterns, race and smoking status.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of the findings. These included restricting all analyses to couples with complete female diet data, and to the first treatment cycle for each couple for IVF outcomes. We also conducted analyses stratified by primary infertility diagnosis (male factor vs. female and unexplained factor), IVF treatment history, and past pregnancy history. In addition, we conducted stratified analysis of previous infertility examination for the association between dietary pattern and semen quality. All analyses were performed using SAS university edition with VirtualBox version 6.1.6.

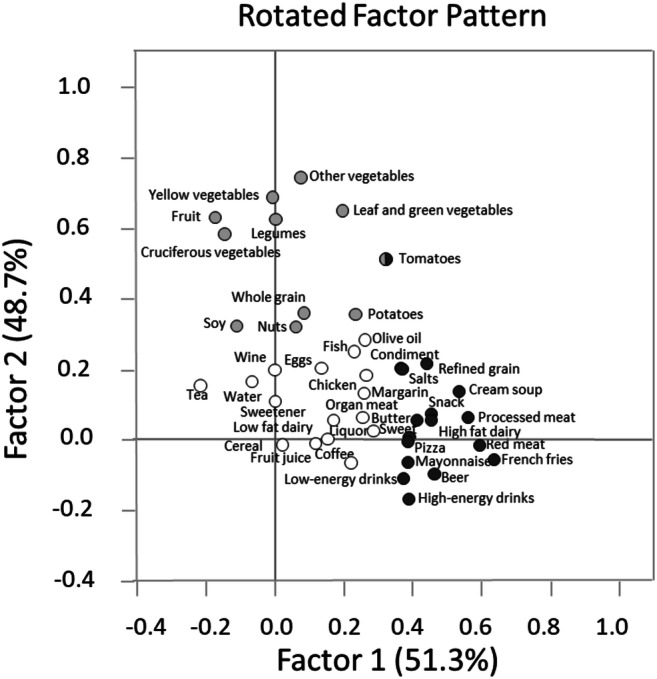

Results

A total of 231 couples who underwent 407 IVF cycles were included in the analysis. Median age of male partners at enrollment was 36.8 years (interquartile range (IQR): 33.4–40.0 years) and median BMI was 26.9 kg/m2 (IQR: 24.1–29.1 kg/m2). Most men were white (89.2%) and had never smoked (66.2%) (Table 1). Women had a median baseline age and BMI of 35.0 years (IQR: 32.0–38.0 years) and 23.1 kg/m2 (IQR: 21.0–25.7 kg/m2), respectively. Male factor infertility was the most common initial primary infertility diagnosis (36.8%). Two dietary patterns were identified using PCA (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental figure 1). Dietary Pattern 1 was characterized by greater intakes of processed meats, unprocessed red meats, high-fat dairy, beer, French fries, cream soups, refined grains, pizza, snacks, and sweets. Dietary Pattern 2 was characterized by greater intakes of fruit, vegetables, legumes, soy foods, whole grains, nuts, and nut butters. Intakes of organ meats, fish, chicken, eggs, margarine, low-fat dairy, liquor, wine, tea, coffee, fruit juice, cold breakfast cereal, salad dressings, artificial sweeteners, and water did not have high loading scores on either of the identified dietary patterns (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, nutritional, and reproductive characteristics of study participants, overall and in lowest and highest quartiles of adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2*

| n | Total | Dietary Pattern 1 | Dietary Pattern 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q4 | P** | Q1 | Q4 | P** | ||

| 231 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 58 | |||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (y) | 36.8 (33.4–40.0) | 37.9 (34.1–40.0) | 36.0 (33.6–40.5) | 0.67 | 35.5 (33.0–39.2) | 38.0 (34.0–41.9) | 0.08 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 (24.1–29.1) | 26.6 (23.7–29.3) | 27.5 (25.4–29.4) | 0.01 | 27.4 (25.6–30.0) | 27.1 (25.1–28.7) | 0.04 |

| Race, white | 206 (89.2) | 47 (82.5) | 55 (94.8) | 0.21 | 54 (94.7) | 51 (87.9) | 0.43 |

| Smoking status, never smoker | 153 (66.2) | 44 (77.2) | 34 (58.6) | 0.19 | 36 (63.2) | 40 (69.0) | 0.32 |

| Education, college or higher | 183 (84.7) | 48 (90.6) | 46 (83.6) | 0.51 | 37 (71.2) | 47 (85.5) | 0.02 |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (min/week) | 165 (60–390) | 150 (60–330) | 168 (47–390) | 0.28 | 150 (30–360) | 205 (72–402) | 0.29 |

| Calories (kcal/day) | 1934 (1586–2384) | 1530 (1225–1843) | 2585 (2164–2934) | <0.001 | 1664 (1237–2077) | 2568 (2096–2900) | <0.001 |

| Reproductive characteristics | |||||||

| History of varicocele | 19 (8.2) | 4 (7.0) | 4 (6.9) | 0.95 | 5 (8.8) | 4 (6.9) | 0.57 |

| Female partner characteristics | |||||||

| Age (y) | 35.0 (32.0–38.0) | 35.0 (32.0–39.0) | 35.0 (32.0–38.0) | 0.78 | 35.0 (32.0–38.0) | 36.0 (33.0–39.0) | 0.36 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 (21.0–25.7) | 22.0 (20.5–25.5) | 23.9 (21.6–27.9) | 0.11 | 23.3 (21.7–27.9) | 23.1 (20.7–25.7) | 0.41 |

| Race, white | 194 (84.4) | 40 (70.2) | 49 (84.5) | 0.006 | 48 (84.2) | 48 (82.8) | 0.97 |

| Smoking status, never smoker | 166 (72.2) | 41 (71.9) | 43 (74.1) | 0.17 | 39 (68.4) | 44 (75.9) | 0.18 |

| Dietary Pattern 1 | −0.38 (−0.87 to −0.01) | −0.88 (−1.07 to −0.34) | −0.08 (−0.40 to 0.54) | <.001 | −0.36 (−0.85 to 0.07) | −0.31 (−0.86 to 0.10) | 0.8 |

| Dietary Pattern 2 | −0.04 (−0.50 to 0.56) | 0.10 (−0.36 to 0.75) | −0.05 (−0.42 to 0.58) | 0.47 | −0.44 (−0.99 to −0.15) | 0.57 (−0.05 to 1.16) | <0.001 |

| Couple-level characteristics | |||||||

| History of past pregnancy | 86 (37.4) | 22 (38.6) | 19 (32.8) | 0.64 | 24 (42.1) | 21 (36.2) | 0.2 |

| Previous infertility examination | 188 (83.6) | 45 (81.8) | 44 (78.6) | 0.56 | 46 (82.1) | 47 (83.9) | 0.24 |

| Previous infertility treatment | 107 (51.7) | 20 (40.0) | 31 (60.8) | 0.13 | 25 (48.1) | 31 (58.5) | 0.39 |

| Primary infertility diagnosis | |||||||

| Male factor | 85 (36.8) | 21 (36.8) | 23 (39.7) | 0.93 | 20 (35.1) | 17 (29.3) | 0.26 |

| Female factors | |||||||

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 24 (10.4) | 8 (14.0) | 6 (10.3) | 7 (12.3) | 8 (13.8) | ||

| Endometriosis | 14 (6.1) | 4 (7.0) | 2 (3.5) | 5 (8.8) | 4 (6.9) | ||

| Ovulatory | 22 (9.5) | 5 (8.8) | 2 (3.5) | 7 (12.3) | 4 (6.9) | ||

| Tubal disease | 17 (7.4) | 5 (8.8) | 4 (6.9) | 5 (8.8) | 3 (5.2) | ||

| Uterine | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Other disease | 4 (1.7) | 2 (3.5) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.9) | ||

| Unexplained | 62 (26.8) | 11 (19.3) | 20 (34.5) | 12 (21.1) | 17 (29.3) | ||

| Initial stimulation protocol | |||||||

| Antagonist | 35 (15.2) | 14 (24.6) | 9 (15.5) | 0.12 | 9 (15.8) | 9 (15.5) | 0.77 |

| Flare | 22 (9.5) | 8 (14.0) | 4 (6.9) | 4 (7.0) | 5 (8.6) | ||

| Luteal phase agonist | 152 (65.8) | 33 (57.9) | 39 (67.2) | 39 (68.4) | 38 (65.5) | ||

| Egg donor or cryo-cycle | 22 (9.5) | 2 (3.5) | 6 (10.3) | 5 (8.8) | 6 (10.3) | ||

| Initial mode of insemination; ICSI | 122 (59.2) | 33 (61.1) | 28 (53.9) | 0.85 | 28 (53.9) | 33 (64.7) | 0.71 |

*Data are presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables or n (%) for categorical variables

**From the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables except for primary infertility diagnosis and in vitro fertilization treatment protocol where the Chi-square test was used

BMI body mass index, Q quartile

Fig. 1.

Principal component analysis plot with two factor loadings for food groups among 231 couples undergoing infertility treatment. Dark gray: Food groups which had factor 1 loading greater than 0.3. Light gray: Food groups which had factor 2 loading greater than 0.3. White: Food groups which had both factor 1 and factor 2 loading less than 0.3

Men’s adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 was associated with higher BMI. Men’s adherence to Dietary Pattern 2 was inversely related to BMI and positively related to educational attainment. Adherence to both patterns was positively related to higher total calorie intake. Moreover, adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 (rPearson=0.44) and Dietary Pattern 2 (rPearson=0.54) was positively correlated within couples (Table 1). Supplemental Table 3 shows the distribution of semen quality parameters among male participants. Approximately 40–60% of participants demonstrated asthenospermia according to the WHO reference limits [37].

Adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 was positively related to sperm concentration. A 1-unit increase in this pattern was associated with a 13.33 (0.71–25.96) million/mL higher sperm concentration (Table 2). This association was stronger among men who had had an infertility examination prior to joining the study (β=17.93 (3.55 to 32.30) million/mL). The association was in the opposite direction among men who had not had an infertility examination before joining the study, although sample size was limited in this group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between men’s adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2 and semen parameters

| Estimate (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pattern 1 | Pattern 2 | |

| Total | N=231 men | |

| Volume | −0.21 (−0.48 to 0.04) | −0.16 (−0.38 to 0.05) |

| Total sperm count | 1.54 (−24.70 to 27.77) | −16.53 (−38.41 to 5.35) |

| Sperm concentration | 13.33 (0.71 to 25.96) * | 1.07 (−9.42 to 11.57) |

| Total motility | 0.17 (−4.36 to 4.70) | −1.97 (−5.73 to 1.80) |

| Progressive motility | 0.64 (−2.21 to 3.48) | −0.76 (−3.12 to 1.60) |

| Morphology | 0.03 (−0.58 to 0.65) | 0.11 (−0.41 to 0.62) |

| Past examination | N=188 men | |

| Volume | −0.20 (−0.49 to 0.08) | −0.11 (−0.36 to 0.12) |

| Total sperm count | 11.23 (−17.55 to 40.01) | −11.87 (−36.47 to 12.72) |

| Concentration | 17.93 (3.55 to 32.30) * | 2.98 (−9.26 to 15.22) |

| Total motility | 1.12 (−3.67 to 5.92) | −2.24 (−6.31 to 1.83) |

| Progressive motility | 1.15 (−1.97 to 4.27) | −1.03 (−3.68 to 1.62) |

| Morphology | 0.40 (−0.30 to 1.09) | 0.16 (−0.43 to 0.75) |

| Never examination | N=37 men | |

| Volume | −0.20 (−0.84 to 0.43) | −0.36 (−0.86 to 0.14) |

| Total sperm count | −52.28 (−108.91 to 4.34) | −43.63 (−88.17 to 0.92) |

| Concentration | −15.50 (−37.52 to 6.52) | −13.02 (−30.24 to 4.21) |

| Total motility | −6.03 (−17.84 to 5.78) | −3.14 (−12.37 to 6.09) |

| Progressive motility | −3.74 (−9.82 to 2.34) | −1.82 (−6.59 to 2.94) |

| Morphology | −2.11 (−3.07 to −1.14) * | −0.14 (−0.95 to 0.67) |

*P<0.05

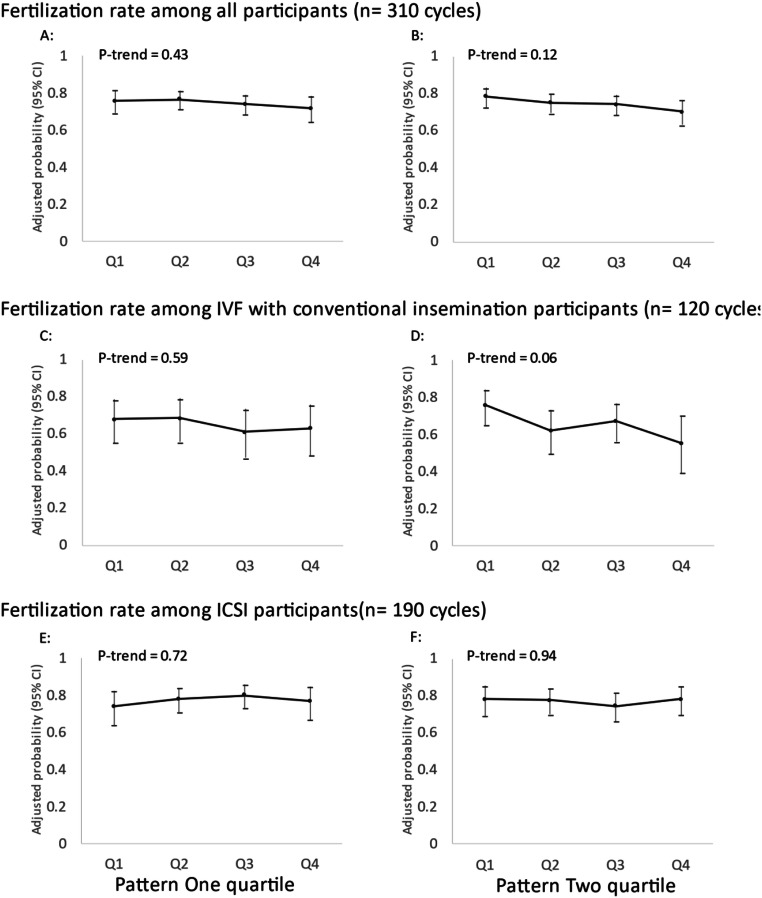

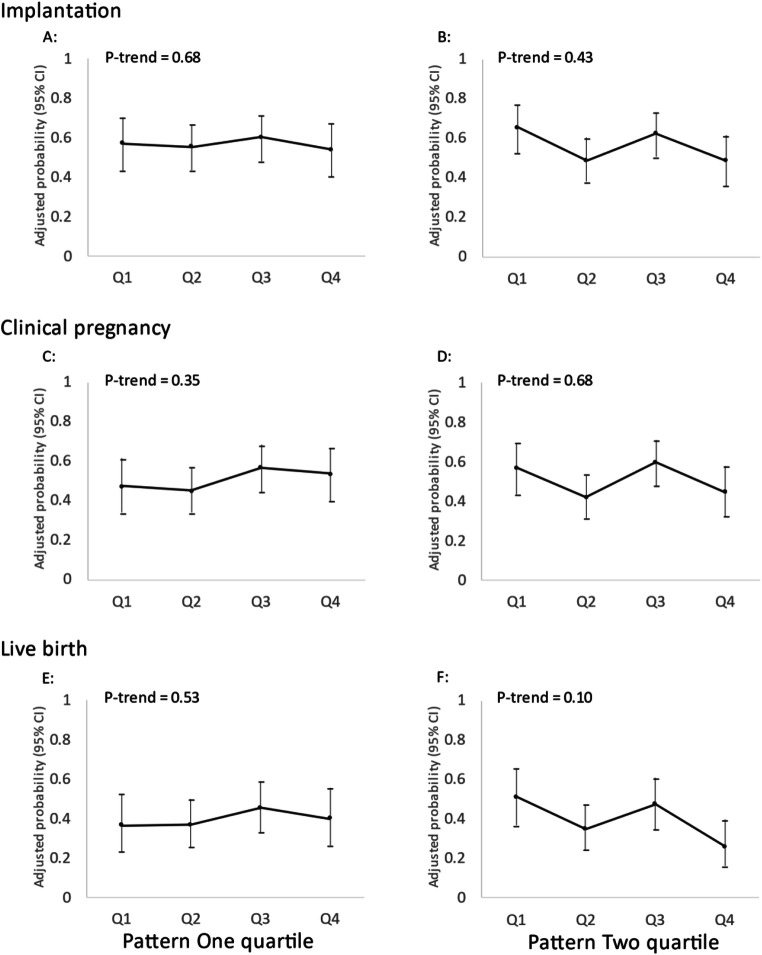

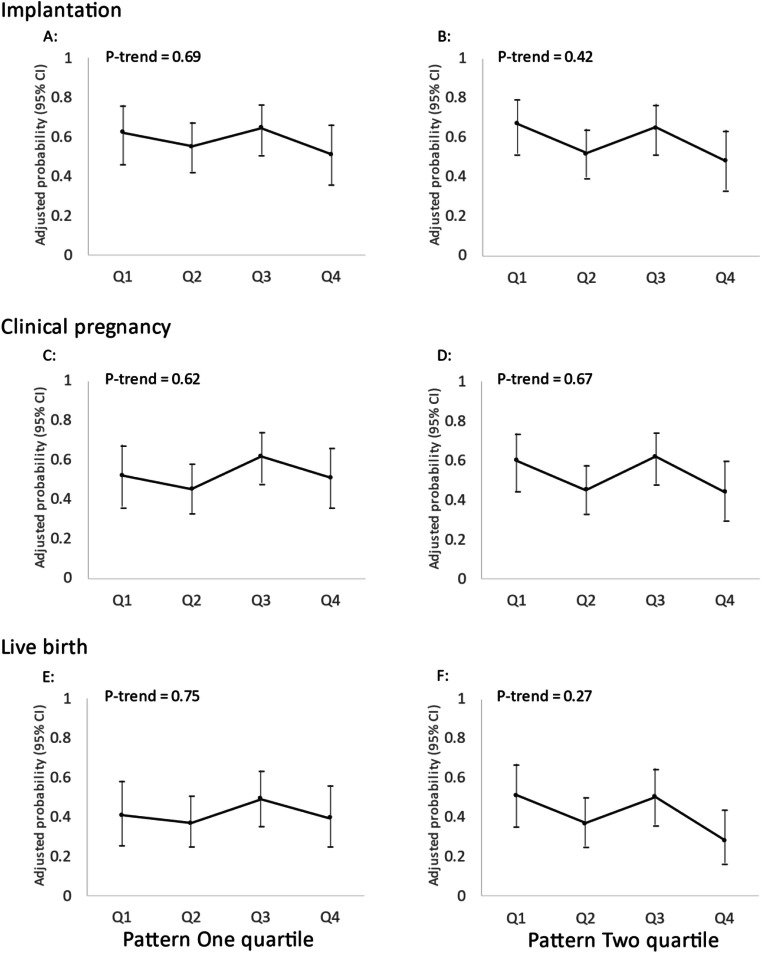

There was no association between men’s adherence to two data-derived dietary patterns and fertilization rate in total cycles, stratified analyses for IVF cycles using conventional insemination and ICSI cycles (Fig. 2). There was also no discernible association of men’s adherence to either dietary pattern with probabilities of implantation, clinical pregnancy or live birth in multivariable-adjusted models without (Fig. 3) or with adjustment for women’s adherence to the same dietary patterns (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Men’s adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2 in relation to fertilization rate. Adjusted for men’s age, total calorie intake, BMI, race, smoking status, education level, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; women’s age and BMI; primary infertility and treatment protocol. Q, quartile

Fig. 3.

Men’s adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2 in relation to clinical outcomes of infertility treatment with IVF (N = 231 couples, 407 cycles). Adjusted for men’s age, total calorie intake, BMI, race, smoking status, education level, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; women’s age and BMI; primary infertility diagnosis and treatment protocol

Fig. 4.

Men’s adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2 in relation to clinical outcomes of infertility treatment with IVF after co-adjustment for women’s adherence to the same diet patterns (N = 213 couples, 367 cycles). Adjusted for men’s age, total calorie intake, BMI, race, smoking status, education level, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; women’s age, BMI, and adherence to Dietary Patterns 1 and 2; primary infertility diagnosis and treatment protocol. Q, quartile

In sensitivity analyses, results were consistent with the primary findings when analyses were restricted to couples with complete female diet data (Supplemental Figure 2) and to the first treatment cycle for each couple (Supplemental Figure 3). Similarly, analyses stratified by a primary infertility diagnosis (Supplemental Figure 4), past IVF treatment history (Supplemental Figure 5), or past pregnancy history (Supplemental Figure 6) showed no association between the dietary patterns and IVF outcomes either.

Discussion

We investigated the association of men’s adherence to two data-derived dietary patterns identified using a data-driven approach with intake data collected using a validated 131-item FFQ with semen quality and outcomes of infertility treatment with IVF. Despite sperm concentration being associated with one of these patterns, we found no evidence that men’s adherence to these dietary patterns had any meaningful impact on the outcome of infertility treatment with IVF. To our knowledge, this is the first study to date examining the association between men’s dietary patterns and couples’ IVF outcomes. Hence, it is important that this question is revisited in additional studies.

The finding that higher adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 was associated with higher sperm concentration stands in contrast with several observational studies suggesting that male adherence to dietary patterns linked to higher chronic disease risk could also have a negative impact on semen quality [17, 41, 42], whereas the opposite appears to be the case for adherence to diet patterns previously related to lower risk of chronic comorbidities [15–18, 41–43]. A possible reason for the observed relation and the inconsistency with previous literature may be reverse causation. As couples undergo diagnostic testing for infertility, results from these tests may influence their behavior. In this study, knowledge of results of semen analyses, and possibly other diagnostic information, may change the way in which men eat or engage in other behaviors with the goal of optimizing their fertility and this change in behavior would be expected to be differential between men with poor and men with favorable semen analyses. For example, if men who know that their semen analysis was above the WHO reference limit would not change their diet, whereas if they were informed that they had abnormal results in their semen analysis, we would expect them to change their behavior. So, any association between diet and semen quality would be more reflective of this differential change in behavior than of any true influence that diet may have on semen quality. This situation is analogous to previously described paradoxical associations in cross-sectional studies of diet with outcomes that are known to participants, such as the cross-sectional association between intake of diet sodas and BMI [44, 45]. Similarly, although there was no association between adherence to dietary patterns and sperm morphology in the entire study sample, higher adherence to Dietary Pattern 1 among men who had not been previously evaluated for infertility was inversely related to sperm morphology. This relationship is reminiscent of a previous report of processed meat intake—which has a high factor loading in Diet Pattern 1—with sperm morphology [46]. Our findings, and in particular the divergent pattern after stratified stratification by whether or not men had undergone diagnostic procedures prior to joining the study, highlight a potential peril of conducting research on behavioral determinants of semen quality in clinical populations.

Data on men’s diet and a couple’s fertility is scant, yet the literature on diet and semen quality has been interpreted as implying positive effects on a couple’s fertility. However, the evidence base to support this inference is weak. To start, semen quality is known to be a weak predictor of probability of conception both among couples attempting conception on their own as well as in couples trying to conceive with medical assistance [21, 22]. Moreover, in previous reports from this cohort, we have found that specific dietary factors related to semen quality, such as intake of processed meat, dairy, and soy foods [46–48], are unrelated to infertility treatment outcomes [23, 49, 50]. Conversely, we have found that dietary factors that have been consistently found to be unrelated to semen quality, such as intakes of alcohol and caffeine [5, 6], were, paradoxically, related to live birth rates during the course of IVF [51]. This does not mean that there are no specific nutritional factors that can impact couple fertility by improving semen quality. For example, we and others have documented positive associations between intake of fish, fish oil, or marine fatty acids and better semen quality and other markers of testicular function [52–55] and, independently, with greater fecundability [24]. Nevertheless, the discrepancies highlight the fact that improvements in semen quality do not necessarily imply improvements in IVF outcomes for couples undergoing treatment and that, therefore, the identification of male partner characteristics that impact a couple’s fertility requires the direct evaluation of IVF outcomes as the study outcome rather than relying on semen quality as a proxy outcome as has been traditional in andrology and reproductive medicine.

It is important to mention that male effects on reproduction not mediated through traditional semen quality parameters are not purely theoretical. Although the evidence base is still emerging, there is literature showing that the sperm genome and epigenome may play an important role in fertility [56, 57] and are subject to environmental modification [58, 59]. Also, while not directly examining fertility, emerging experimental data suggests that paternal environmental exposures could exert effects on pregnancy and offspring health through the sperm epigenome [60–62]. For example, folate-deficient, high-fat, or low-protein diets in males, but not females, negatively impact offspring’s metabolism through epigenetic mechanisms [60, 62]. These findings suggest that men’s diet can impact reproduction through additional mechanisms.

As discussed above, a possible interpretation of our findings is that, despite previous research relating dietary patterns to semen quality, men’s diet has no impact on a couple’s outcomes through IVF. The interpretation of a lack of effect is also in line with findings from two recent randomized trials which found no effect on live birth rate of supplementing men in infertile couples with custom micronutrient formulations [63, 64]. A related explanation for the lack of association is the fact that we studied this question among couples undergoing infertility treatment with IVF. ICSI has been the most widely utilized assisted reproductive technology over the recent years [65] and IVF/ICSI is a powerful intervention for male factor infertility and impaired semen quality (primarily on concentration and motility) that may completely offset comparatively smaller impacts of men’s diet on semen quality. If this is the case, reexamining this question among couples attempting conception without medical intervention is essential. It is also important to consider alternate interpretations. One possibility is that the data-derived dietary patterns did not capture food groups that could impact fertility. For example, fish intake was not part of either of the dietary patterns identified in this analysis, but has been previously linked to a couple’s fertility [24]. Clearly, additional work aimed at identifying male partner factors, including modifiable lifestyle factors, that could impact a couple’s fertility is necessary.

It is also important to interpret the results in light of the study’s limitations and strengths. First, we only assessed diet at baseline FFQ and hence, we were unable to document any changes in diet over time as couples underwent treatment. This could result in a dilution of the actual relationship, particularly for couples who take longer to conceive, either due to longer intervals from enrollment to first treatment cycle or more failed treatment cycles, or are never able to conceive. However, sensitivity analyses restricted to each couple’s first cycle were consistent with the primary findings. Also, this study was conducted at an academic fertility center and more than 80% of the men had already been examined before the study baseline. Therefore, it is important to consider the extent to which associations with semen quality reflect an effect of diet on spermatogenesis or the effect of being aware of one’s semen quality on subsequent dietary behaviors. Second, although we used an extensively validated diet questionnaire, measurement error is still unavoidable in questionnaire-based studies of diet. Given that diet assessment preceded treatment outcome assessment the expected effect would be an attenuation of effect estimates towards the null. Third, as mentioned above, investigating the role of men’s diet on fertility among couples undergoing IVF could completely obscure a true but modest effect of men’s diet on a couple’s fertility and therefore results cannot be generalized to couples attempting conception naturally. Last, the study population was primarily white. While this certainly limits generalizability to other racial groups, the race distribution in our study closely mirrors that of couples undergoing infertility treatment nationwide and therefore results can still inform practice.

Strengths of the study include the recruitment of both male and female partners, which is, unfortunately, still not the norm in fertility studies and allowed us to inquire about the role men’s diet may have on fertility. Moreover, it allowed us to take into consideration within-couple correlations and discordance in diet and other relevant behavioral and demographic factors that could influence the outcome of infertility treatment. For example, diet is a complex and dynamic behavior that, while correlated within couples, is not perfectly matched within couples as shown by the modest within-couple correlation for both dietary patterns. While counterintuitive at first sight, this is not unexpected. In couples where both partners work outside of the home, which is the most common arrangement for couples in our study, it is not unusual for couples to have a substantial number of eating occasions completely separate from each other, most obviously but not exclusively, lunch and any daytime snacks. The study’s prospective design with complete follow-up of clinically relevant outcomes including live birth rate, the extensive collection of key lifestyle factors in both partners, and the use of validated instruments also adds to the study’s strengths.

In brief, results from this study suggest that men’s adherence to two data-derived dietary patterns was not related to outcomes of infertility treatment with IVF in spite of an association between one of these patterns and sperm concentration. These results differ with the expanding literature suggesting that adherence to healthy dietary patterns is related to better semen quality. Given the scarcity of data on this topic, it is important that additional studies examine the role of men’s diet on fertility both in the setting of infertility treatment and among couples attempting conception without medical assistance.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 775 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all members of the EARTH study team and extend a special thanks to all the study participants.

Author contribution

Jorge E. Chavarro was involved in study concept and design and critical revision for important intellectual content of the manuscript and had a primary responsibility for final content. Makiko Mitsunami drafted the manuscript and analyzed data; Albert Salas-Huetos reviewed the statistical analysis; Lidia Mínguez-Alarcón contributed to the statistical analysis; Jennifer B. Ford and Irene Souter were involved in acquisition of the data; Makiko Mitsunami, Albert Salas-Huetos, Lidia Mínguez-Alarcón, Jill A. Attaman, Jennifer B. Ford, Martin Kathrins, Irene Souter, and Jorge E. Chavarro interpreted the data; all authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Supported by grants ES009718, ES022955, ES026648, and ES000002 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and P30DK46200 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Data availability

Data are available upon request after approval of data sharing and use agreements between institutions.

Code availability

All analyses were performed using SAS university edition with VirtualBox version 6.1.6.

Code is available upon request after approval of data sharing and use agreements between institutions.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The EARTH study was approved by the institutional review board of both MGH and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Consent to participate

All participants to the EARTH study completed written consent forms.

Consent for publication

The written consent forms included the permission for publication.

Competing interests

Not aplicable for Makiko Mitsunami, Albert Salas-Huetos, Lidia Mínguez-Alarcón, Jill A. Attaman, Jennifer B. Ford, Martin Kathrins, Irene Souter.

Jorge E. Chavarro received grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, Sullivan E, Vanderpoel S, International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology. World Health Organization International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009∗. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg ML, Li S, Cullen MR, Baker LC. Increased risk of incident chronic medical conditions in infertile men: analysis of United States claims data. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(3):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundhun PK, Janoo G, Bhurtu A, Teeluck AR, Soogund MZS, Pursun M, Huang F. Tobacco smoking and semen quality in infertile males: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci E, Al Beitawi S, Cipriani S, Candiani M, Chiaffarino F, Viganò P, et al. Semen quality and alcohol intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;34(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Lin H, Li Y, Cao J. Association between socio-psycho-behavioral factors and male semen quality: systematic review and meta-analyses. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jóźków P, Rossato M. The impact of intense exercise on semen quality. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(3):654–662. doi: 10.1177/1557988316669045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nassan FL, Arvizu M, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Gaskins AJ, Williams PL, Petrozza JC, Hauser R, Chavarro JE, EARTH Study Team Marijuana smoking and outcomes of infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(9):1818–1829. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JM, Lane M, Owens JA, Bakos HW. Paternal obesity negatively affects male fertility and assisted reproduction outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;31(5):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salas-Huetos A, Maghsoumi-Norouzabad L, James ER, Carrell DT, Aston KI, Jenkins TG, et al. Male adiposity, sperm parameters and reproductive hormones: an updated systematic review and collaborative meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 ;obr.13082. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation. 2009;119(8):1093–1100. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmon BE, Boushey CJ, Shvetsov YB, Ettienne R, Reedy J, Wilkens LR, le Marchand L, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Associations of key diet-quality indexes with mortality in the Multiethnic Cohort: the Dietary Patterns Methods Project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(3):587–597. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.090688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahleova H, Salas-Salvadó J, Rahelić D, Kendall CW, Rembert E, Sievenpiper JL. Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic outcomes in diabetes: a summary of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2209. doi: 10.3390/nu11092209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187–225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaskins AJ, Colaci DS, Mendiola J, Swan SH, Chavarro JE. Dietary patterns and semen quality in young men. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(10):2899–2907. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karayiannis D, Kontogianni MD, Mendorou C, Douka L, Mastrominas M, Yiannakouris N. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and semen quality parameters in male partners of couples attempting fertility. Hum Reprod. 2016 ;humrep;dew288v1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Oostingh EC, Steegers-Theunissen RPM, de Vries JHM, Laven JSE, Koster MPH. Strong adherence to a healthy dietary pattern is associated with better semen quality, especially in men with poor semen quality. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(4):916–923.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efrat M, Stein A, Pinkas H, Unger R, Birk R. Dietary patterns are positively associated with semen quality. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(5):809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salas-Huetos A, Babio N, Carrell DT, Bulló M, Salas-Salvadó J. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is positively associated with sperm motility: a cross-sectional analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3389. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39826-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danielewicz A, Morze J, Przybyłowicz M, Przybyłowicz KE. Association of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension, physical activity, and their combination with semen quality: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2019;12(1):39. doi: 10.3390/nu12010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jedrzejczak P, Taszarek-Hauke G, Hauke J, Pawelczyk L, Duleba AJ. Prediction of spontaneous conception based on semen parameters. Int J Androl. 2008;31(5):499–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Schisterman EF, Sweeney A, Lynch CD, Kim S, Maisog JM, Gore-Langton R, Eisenberg ML, Chen Z. Semen quality and time to pregnancy: the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment Study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(2):453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia W, Chiu Y-H, Williams PL, Gaskins AJ, Toth TL, Tanrikut C, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Men’s meat intake and treatment outcomes among couples undergoing assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaskins AJ, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM, Chavarro JE. Seafood intake, sexual activity, and time to pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(7):2680–2688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatch EE, Wesselink AK, Hahn KA, Michiel JJ, Mikkelsen EM, Sorensen HT, et al. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and fecundability in a North American preconception cohort: epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2018;29(3):369–378. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messerlian C, Williams PL, Ford JB, Chavarro JE, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Dadd R, et al. The Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study: a prospective preconception cohort. Hum Reprod Open [Internet]. 2018;2018(2). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/hropen/article/doi/10.1093/hropen/hoy001/4877108. Accessed 19 Jun 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, Chavarro JE, Subar AF, Sampson LK, Willett WC. Validity of a dietary questionnaire assessed by comparison with multiple weighed dietary records or 24-hour recalls. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(7):570–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, Chavarro JE, Rood JC, Harnack LJ, Sampson LK, Willett WC. Relative validity of nutrient intakes assessed by questionnaire, 24-hour recalls, and diet Records as Compared With Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(5):1051–1063. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willett WC, Sampson LK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;185(11):1109–1123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Shaar L, Yuan C, Rosner B, Dean SB, Ivey KL, Clowry CM, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire in men assessed by multiple methods. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;kwaa280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, COLDITZ GA, Rosner B, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):858–867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Sampson L, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(2):243–249. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newby P, Hu FB, Rimm EB, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Sampson L, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of the Diet Quality Index Revised as assessed by use of a food-frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):941–949. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu FB, Satija A, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Sampson L, Rosner B, Camargo CA, Jr, Stampfer M, Willett WC. Diet assessment methods in the nurses’ health studies and contribution to evidence-based nutritional policies and guidelines. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1567–1572. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(4):912–921. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization, editor. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 5. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mínguez-Alarcón L, Williams PL, Chiu Y-H, Gaskins AJ, Nassan FL, Dadd R, Petrozza J, Hauser R, Chavarro JE, Earth Study Team Secular trends in semen parameters among men attending a fertility center between 2000 and 2017: identifying potential predictors. Environ Int. 2018;121:1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruger TF, Acosta AA, Simmons KF, Swanson RJ, Matta JF, Oehninger S. Reprint of: predictive value of abnormal sperm morphology in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(4):e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares Means. 2020;7.

- 41.Nassan FL, Jensen TK, Priskorn L, Halldorsson TI, Chavarro JE, Jørgensen N. Association of dietary patterns with testicular function in young Danish men. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921610. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cutillas-Tolín A, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Mendiola J, López-Espín JJ, Jørgensen N, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, et al. Mediterranean and western dietary patterns are related to markers of testicular function among healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2015;dev236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Cutillas-Tolín A, Adoamnei E, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, Vioque J, Moñino-García M, Jørgensen N, Chavarro JE, Mendiola J, Torres-Cantero AM. Adherence to diet quality indices in relation to semen quality and reproductive hormones in young men. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(10):1866–1875. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, MPharm BFC, Rabbani R, Lys J, Copstein L, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28):11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinkle SN, Rawal S, Bjerregaard AA, Halldorsson TI, Li M, Ley SH, Wu J, Zhu Y, Chen L, Liu A, Grunnet LG, Rahman ML, Kampmann FB, Mills JL, Olsen SF, Zhang C. A prospective study of artificially sweetened beverage intake and cardiometabolic health among women at high risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):221–232. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afeiche MC, Gaskins AJ, Williams PL, Toth TL, Wright DL, Tanrikut C, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Processed meat intake is unfavorably and fish intake favorably associated with semen quality indicators among men attending a fertility clinic. J Nutr. 2014;144(7):1091–1098. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.190173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afeiche MC, Bridges ND, Williams PL, Gaskins AJ, Tanrikut C, Petrozza JC, et al. Dairy intake and semen quality among men attending a fertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(5):1280–1287.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Povey AC, Clyma J, McNamee R, Moore HD, Baillie H, Pacey AA, et al. Phytoestrogen intake and other dietary risk factors for low motile sperm count and poor sperm morphology. Andrology. 2020;8(6):1805–1814. doi: 10.1111/andr.12858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia W, Chiu Y-H, Afeiche MC, Williams PL, Ford JB, Tanrikut C, Souter I, Hauser R, Chavarro JE, the EARTH study team Impact of men’s dairy intake on assisted reproductive technology outcomes among couples attending a fertility clinic. Andrology. 2016;4(2):277–283. doi: 10.1111/andr.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mínguez-Alarcón L, Afeiche MC, Chiu Y-H, Vanegas JC, Williams PL, Tanrikut C, Toth TL, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Male soy food intake was not associated with in vitro fertilization outcomes among couples attending a fertility center. Andrology. 2015;3(4):702–708. doi: 10.1111/andr.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karmon AE, Toth TL, Chiu Y-H, Gaskins AJ, Tanrikut C, Wright DL, Hauser R, Chavarro JE, the Earth Study Team Male caffeine and alcohol intake in relation to semen parameters and in vitro fertilization outcomes among fertility patients. Andrology. 2017;5(2):354–361. doi: 10.1111/andr.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Attaman JA, Toth TL, Furtado J, Campos H, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Dietary fat and semen quality among men attending a fertility clinic. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1466–1474. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ricci E, Al-Beitawi S, Cipriani S, Alteri A, Chiaffarino F, Candiani M, et al. Dietary habits and semen parameters: a systematic narrative review. Andrology. 2018;6(1):104–116. doi: 10.1111/andr.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salas-Huetos A, James ER, Aston KI, Jenkins TG, Carrell DT. Diet and sperm quality: nutrients, foods and dietary patterns. Reprod Biol. 2019;19(3):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jensen TK, Priskorn L, Holmboe SA, Nassan FL, Andersson A-M, Dalgård C, Petersen JH, Chavarro JE, Jørgensen N. Associations of fish oil supplement use with testicular function in young men. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919462. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jodar M, Sendler E, Moskovtsev SI, Librach CL, Goodrich R, Swanson S, et al. Absence of sperm RNA elements correlates with idiopathic male infertility. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(295):295re6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turner KA, Rambhatla A, Schon S, Agarwal A, Krawetz SA, Dupree JM, Avidor-Reiss T. Male infertility is a women’s health issue—research and clinical evaluation of male infertility is needed. Cells. 2020;9(4):990. doi: 10.3390/cells9040990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Estill M, Hauser R, Nassan FL, Moss A, Krawetz SA. The effects of di-butyl phthalate exposure from medications on human sperm RNA among men. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12397. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salas-Huetos A, James ER, Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Aston KI, Carrell DT, et al. Sperm DNA methylation changes after short-term nut supplementation in healthy men consuming a Western-style diet. Andrology. 2020 Nov 3;andr.12911. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Lambrot R, Xu C, Saint-Phar S, Chountalos G, Cohen T, Paquet M, Suderman M, Hallett M, Kimmins S. Low paternal dietary folate alters the mouse sperm epigenome and is associated with negative pregnancy outcomes. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):2889. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, Feng GH, Peng H, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Qian J, Duan E, Zhai Q, Zhou Q. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science. 2016;351(6271):397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watkins AJ, Dias I, Tsuro H, Allen D, Emes RD, Moreton J, Wilson R, Ingram RJM, Sinclair KD. Paternal diet programs offspring health through sperm- and seminal plasma-specific pathways in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(40):10064–10069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806333115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steiner AZ, Hansen KR, Barnhart KT, Cedars MI, Legro RS, Diamond MP, et al. The effect of antioxidants on male factor infertility: the Males, Antioxidants, and Infertility (MOXI) randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(3):552-560.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Schisterman EF, Sjaarda LA, Clemons T, Carrell DT, Perkins NJ, Johnstone E, Lamb D, Chaney K, van Voorhis BJ, Ryan G, Summers K, Hotaling J, Robins J, Mills JL, Mendola P, Chen Z, DeVilbiss EA, Peterson CM, Mumford SL. Effect of folic acid and zinc supplementation in men on semen quality and live birth among couples undergoing infertility treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(1):35–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Chambers GM, Zegers-Hochschild F, Mansour R, Ishihara O, Banker M, Dyer S. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(6):1067–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 775 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request after approval of data sharing and use agreements between institutions.

All analyses were performed using SAS university edition with VirtualBox version 6.1.6.

Code is available upon request after approval of data sharing and use agreements between institutions.