Abstract

While spinal cord injuries (SCIs) result in a vast array of functional deficits, many of which are life threatening, the majority of SCIs are anatomically incomplete. Spared neural pathways contribute to functional and anatomical neuroplasticity that can occur spontaneously, or can be harnessed using rehabilitative, electrophysiological, or pharmacological strategies. With a focus on respiratory networks that are affected by cervical level SCI, the present review summarizes how non-invasive respiratory treatments can be used to harness this neuroplastic potential and enhance long-term recovery. Specific attention is given to “respiratory training” strategies currently used clinically (e.g., strength training) and those being developed through pre-clinical and early clinical testing [e.g., intermittent chemical stimulation via altering inhaled oxygen (hypoxia) or carbon dioxide stimulation]. Consideration is also given to the effect of training on non-respiratory (e.g., locomotor) networks. This review highlights advances in this area of pre-clinical and translational research, with insight into future directions for enhancing plasticity and improving functional outcomes after SCI.

Keywords: rehabilitation, spinal cord injury, neuroplasticity, respiration, diaphragm, phrenic

Introduction

Respiratory dysfunction is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) (DeVivo et al., 1993; Winslow and Rozovsky, 2003; Garshick et al., 2005; Hoh et al., 2013). Damage to the neural networks controlling respiration frequently occurs following mid- or high-cervical injuries, which disrupt the phrenic motor circuit. The phrenic network is responsible for diaphragm innervation, which is often considered the primary muscle of respiration (Feldman, 1986; Lane, 2011; Hoh et al., 2013). Therefore, damage to this circuit results in diaphragm paresis or paralysis leading to respiratory deficits (Jackson and Groomes, 1994; Linn et al., 2000). In addition, injuries at this level will at least partially denervate intercostal and abdominal motor pools that are innervated by spinal motor neurons in the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord. The intercostal and abdominal respiratory circuits are also primary respiratory networks that are important for regular inspiratory and expiratory behaviors. Impaired respiratory muscle function can lead to decreased inspiration and vital capacity, potentially complete apnea, ventilator assistance (Jackson and Groomes, 1994; Linn et al., 2000; DiMarco, 2005; Onders et al., 2007), and secondary respiratory complications such as pneumonia (Dalal and DiMarco, 2014). While some spontaneous recovery – or functional plasticity – can occur after injury, it is limited (Vinit et al., 2006; Fuller et al., 2008; Lane et al., 2009), and significant deficits in breathing persist for months post-injury (Fuller et al., 2008; Vinit et al., 2008). There are many methods to assess the extent of these respiratory deficits. These include measures of ventilation, or “breathing behavior” (tidal volume, minute ventilation) and respiratory nerve or muscle activity (diaphragm EMG or phrenic nerve recording) (Lane et al., 2008a).

For the purpose of this review neuroplasticity is defined as the ability of the nervous system to change either anatomically and/or functionally, resulting in persistent alterations in sensorimotor function. These changes can be classified as either beneficial (adaptive plasticity) or detrimental (maladaptive plasticity). While plasticity has been extensively studied during development, learning, and memory, there is a rapidly growing interest in the neuroplastic potential of the injured or degenerating nervous system and how it can be therapeutically harnessed. One prominent example of neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury (SCI) has been documented in the respiratory system with spontaneous functional improvement. Here we summarize experimental as well as clinical evidence for spontaneous respiratory neuroplasticity, discuss methods used to harness this via intentional stimulation of respiratory circuits, and provide a summary of studies that propose mechanisms implicating neurotrophic factors as key players.

Respiration After Spinal Cord Injury

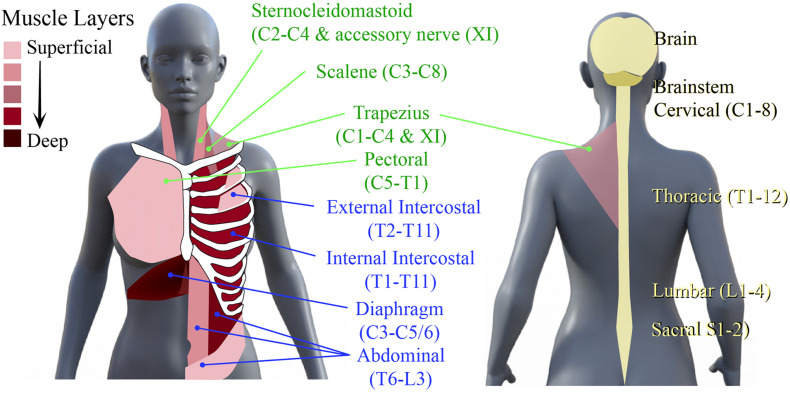

The neural networks mediating respiratory muscle function, comprising spinal interneurons and lower motoneurons, are distributed throughout the rostro-caudal neural axis. Motoneurons that innervate inspiratory, expiratory, and accessory respiratory muscles can be found throughout the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal cord (Lane, 2011). The primary inspiratory muscles include the diaphragm, external intercostal and scalene muscles, while the primary muscles of expiration are the internal intercostals, rectus abdominals and obliques (Van Houtte et al., 2006; Terson de Paleville et al., 2011). The accessory respiratory muscles, which include the sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, and upper trapezius, are recruited when ventilatory demands are higher than normal (Terson de Paleville et al., 2011; Figure 1). Given the rostro-caudal distribution of these motor networks, injury at any level of the spinal cord can compromise respiratory function. For example, a high cervical SCI usually results in denervation and loss of coordination of all respiratory muscles, leading to quadriplegia and respiratory deficits. This leads to paradoxical movement of the chest walls (De Troyer et al., 1986; De Troyer and Estenne, 1990), decreased pulmonary volumes (Anke et al., 1993; Hopman et al., 1997; Tow et al., 2001) and ineffective cough (Brown et al., 2006; Terson de Paleville et al., 2011). Impaired clearance increases risk of secondary complications such as pneumonia (Brown et al., 2006). Even among those people living with SCI that recover voluntary control of breathing, underlying respiratory deficits persist that can manifest in less overt ways, such as sleep-disordered breathing and episodes of hypoxia.

FIGURE 1.

Primary muscles of respiration and their neural circuitry. Schematic diagram of human torso showing the location of the primary muscles of inspiration and expiration and the spinal levels that innervate them.

To treat these deficits respiratory training has been used to stimulate plasticity in networks spared post-SCI. Respiratory training encompasses rehabilitative, resistive, and activity-based training methods to improve and strengthen the neural respiratory circuitry and their corresponding muscles. Early use of respiratory training aimed to strengthen respiratory muscles, using techniques to target inspiratory and expiratory muscles (Figure 1).

Respiratory Neuroplasticity After Spinal Cord Injury

Spontaneous respiratory neuroplasticity has been reported in both clinical (Hoh et al., 2013) and experimental studies (Mitchell and Johnson, 2003; Goshgarian, 2009; Lane et al., 2009; Nicaise et al., 2013; Warren and Alilain, 2014), serving as an excellent example of how the nervous system adapts to injury in order to maintain a vital, physiological function. While this spontaneous plasticity indicates the neuroplastic potential of the respiratory system, the amount of recovery attributable to this plasticity is limited, and long-term deficits in diaphragm activity persist. While neural plasticity can be used to describe changes in both neuronal and non-neuronal components, neuroplasticity (frequently referred to in this text) usually refers selectively to changes in the neuronal networks (see Box 1 for definitions).

Defining terminology. This box highlights definitions of terms used throughout this review.

Plasticity: Lasting anatomical and/or functional changes within neural networks or the behaviors they contribute to. These changes usually arise in response to some form of perturbation (e.g., traumatic injury or degenerative disease). Plasticity can also be stimulated or enhanced by increasing activity within these same neural networks (e.g., locomotor training, respiratory training).

Neural plasticity: Plasticity within central and peripheral neural networks. This has also been used to encompass the muscles they innervate (neuromuscular plasticity). While neuroplasticity has been used interchangeably with neural plasticity, it can perhaps be more appropriately used to selectively describe changes in the neuronal networks rather than changes in both neuronal and non-neuronal components (neural). Importantly, while plasticity is often thought of as being something that is beneficial, there is a growing appreciation for the fact that plasticity can be adaptive (resulting in beneficial consequences) or maladaptive (resulting in detrimental consequences). An example of the latter would be axonal sprouting and increased connectivity within networks that lead to increased pain or spasticity. For the most part, the plasticity discussed in the present review refers to beneficial types.

Anatomical neuroplasticity: Plasticity that typically refers to changes within neuronal connections which can arise via change in synaptic inputs in existing neuronal networks, increased dendritic growth to receive additional inputs, or axonal growth facilitating new neuronal connections. Notably, this neuroplastic axon growth typically arises from collateral sprouts in axonal pathways that were completely spared by injury, from collateral sprouts within injured pathways but proximal to the site of injury, and/or collateral sprouts from injured or non-injured primary afferents. Modest changes can arise spontaneously after injury or be enhanced by treatment.

Molecular neuroplasticity: Plasticity that encompasses an altered synthesis of cytokines, such as trophic factors, that can create a plasticity-promoting environment, attracting axons to the appropriate targets (or inappropriate targets in the case of maladaptive plasticity).

Functional neural plasticity: The restoration of activity in damaged pathways or increased activity in spared pathways to compensate for damage, which can occur after mild, moderate, and severe SCI (restorative vs. compensatory plasticity).

Restorative neural plasticity: Restoration of function in respiratory circuits (and muscles they control) that have been directly compromised/paralyzed by injury.

Compensatory neural plasticity: Altered activity within respiratory circuits (and the muscles they control) that are not directly compromised by injury.

Restorative behavioral neural plasticity: Restoration of the ability to perform ventilation in exactly the same manner as it was performed prior to injury.

Compensatory behavioral plasticity: Effective ventilation, but performed in a manner different from how it was performed prior to injury (e.g., rapid, shallow breathing).

Maladaptive neural plasticity: The amplitude or pattern of neural output may become dysfunctional (e.g., weakened or arhythmic), limiting recovery or contributing to deficit.

Maladaptive behavioral plasticity: Onset of inappropriate patterns of ventilation.

Activity based therapy (ABT): Non-invasive means of increasing motor activity with simultaneous sensory stimulation. In very simple terms this can be thought of as exercise or rehabilitation. Therapeutically, ABTs have been used in both a task specific basis (e.g., training for function within a specific network) or non-task specific basis (e.g., use of respiratory training to improve functional in non-respiratory networks).

Task-specific training: Increasing activity or exercise within specific networks to perform a specific task. For instance, training locomotor networks for rhythmic, patterned locomotion versus stance. Similarly, within the respiratory networks, training for breathing under certain conditions may train for activity within networks primarily known to be involved with that activity (e.g., hypoxia vs. hypercapnia). Data from task-specific training, however, needs to be very carefully interpreted as most forms of ABTs can still have off-target effects (e.g., effects on tasks not trained for).

Anatomical Neuroplasticity

Anatomical respiratory plasticity typically refers to changes within respiratory circuitry, especially neuronal connectivity, that can arise spontaneously after injury or be driven by treatment. Within the spinal cord, there is evidence of spontaneous plasticity involving axonal sprouting, rerouting (Vinit et al., 2005; Vinit and Kastner, 2009; Darlot et al., 2012), and the formation of new polysynaptic connections with phrenic motoneurons via cervical spinal interneurons (Lane et al., 2008b, 2009; Sandhu et al., 2009; Darlot et al., 2012).

One of the most commonly described models of pre-clinical SCI used to study respiratory plasticity has been a lateral Hemisection (Hx) at the second cervical (C2) spinal level. This injury model provides a historical example of respiratory plasticity: the crossed-phrenic phenomenon [CPP (Porter, 1895)]. Although this injury paralyzes the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm immediately, Porter demonstrated that transection of the contralateral phrenic nerve (paralyzing both hemidiaphragms) activated bulbospinal axons that crossed the spinal midline (decussated) below the C2 level to innervate the phrenic motor pool [reviewed in Goshgarian (2003)]. Several lines of research support this, demonstrating that CPP can be elicited soon after injury (O’Hara and Goshgarian, 1991; Goshgarian, 2003; Golder and Mitchell, 2005; Vinit et al., 2006), which suggests that this acute response does not require an anatomical change. Cross correlational analyses of phrenic nerve recordings supported this showing that post-injury function was mediated by bulbospinal pathways (Sandhu et al., 2009). However, these recordings also suggested a progressive recruitment of spinal interneurons into the injured phrenic network, which may be further contributing to functional plasticity. There is evidence of other supraspinal plasticity from sprouting monosynaptic respiratory bulbospinal projections (Vinit and Kastner, 2009; Ghali, 2017) and serotonergic centers (Bach and Mitchell, 1996; Ling et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2001a; Hodges and Richerson, 2010; Hsu and Lee, 2015) onto phrenic circuitry.

While the focus of these anatomical studies has been on neural pathways within the spinal cord, respiratory plasticity occurs throughout the neural axis. Respiratory neuroplasticity extends throughout the CNS within the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, peripheral nervous system (Mantilla and Sieck, 2009; Nicaise et al., 2012b), spinal afferents (Iscoe and Polosa, 1976; Potts et al., 2005; Vinit et al., 2007; Nair et al., 2017), and muscle (Raineteau and Schwab, 2001; Oza and Giszter, 2014, 2015). Identifying and enhancing this anatomical plasticity is crucial to improving respiratory recovery after SCI. Another consideration is that not all plasticity is beneficial. Certainly, depending on the condition, anatomical changes can occur that worsen the potential for recovery. An important example of this in respiratory networks after human SCI is the progressive decline in respiratory muscle anatomy and function with assisted-ventilation (Powers et al., 2002, 2013; Levine et al., 2008; Smuder et al., 2016). To promote respiratory recovery post-SCI, treatments need to take these changes into account.

Molecular Neuroplasticity

Molecular neuroplasticity encompasses an altered synthesis of cytokines, such as trophic factors, that can create a plasticity-promoting environment, attracting axons to the appropriate targets. An example is an increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) after injury or therapeutic intervention (Baker-Herman et al., 2004). Within the respiratory circuit, BDNF upregulation occurs within the phrenic motor neuron pool and is integral in enhancing anatomical plasticity (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Sieck and Mantilla, 2009; Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009; Mantilla et al., 2013, 2014; Gill et al., 2016; Hernandez-Torres et al., 2016; Martinez-Galvez et al., 2016) and promoting rhythmic diaphragm activity (Mantilla et al., 2013; Gransee et al., 2015).

Functional Neural Plasticity

Functional neural plasticity is the restoration of activity in damaged pathways or increased activity in spared pathways to compensate for damage, which can occur after mild, moderate, and severe SCI (Baussart et al., 2006; Golder et al., 2011; Lane et al., 2012; Nicaise et al., 2012a,b, 2013; Awad et al., 2013; Alvarez-Argote et al., 2016). It can also occur at either the neural or behavioral level, resulting in restorative or compensatory motor function (see Box 1).

An example of restorative plasticity within the neural network is the CPP following a C2Hx, and restorative function within the ipsilateral diaphragm. This plasticity is characterized by the activation of ordinarily latent, contralateral respiratory bulbospinal pathways that cross the spinal midline below the injury. This restoration in function occurs after inducing a respiratory stress such as asphyxia, hypoxia, hypercapnia or contralateral phrenicotomy (Porter, 1895; Lewis and Brookhart, 1951; Goshgarian, 2003; Golder and Mitchell, 2005). In contrast, neural compensation is an altered (e.g., elevated) activity within non-injured respiratory circuits and respective muscles. This form of adaptive functional compensates for deficits post injury. For example, an increase of activity within the contralateral phrenic circuit after a C2Hx or C3/4 contusion injury compensates for deficits within ipsilateral circuitry (Golder et al., 2001, 2003).

Behavioral restoration of function is the ability to breathe in the same way after an injury as pre-injury. This ventilation can be measured through plethysmography to record the flow and tidal volume of breathing. An example of this is that following a cervical contusion injury, there is a progressive recovery toward a more normal breathing behavior in post-injury weeks (Choi et al., 2005). In contrast, behavioral compensation manifests as an altered pattern of ventilation after injury. An example of this is rapid, shallow breathing seen after SCI (Choi et al., 2005; Fuller et al., 2009; Golder et al., 2011; Nicaise et al., 2013; Jensen et al., 2019). This phenomenon is also seen following injuries in humans (Ledsome and Sharp, 1981; Haas et al., 1985). This change in breathing behavior likely compensates for respiratory deficits.

The extent of functional neuroplasticity and motor recovery is closely tied to anatomical plasticity and changes within the circuit or the extent of the lesion. For example, with a more mild contusive injury, there will be a higher likelihood of recovery and limited functional deficit (Alvarez-Argote et al., 2016). Restorative functional plasticity relies on anatomical pathways to be connected, or in some cases, strengthen connections, form new connections, or establish novel pathways. Accordingly, this has been reported several weeks to months following injury. In contrast, compensatory plasticity typically occurs soon after injury and initially relies solely on existing anatomical substrates. With continued change in activity within those pathways, however, there can be progressive anatomical changes that further contribute to, or reinforce, compensatory functions.

Methods to Enhance Plasticity

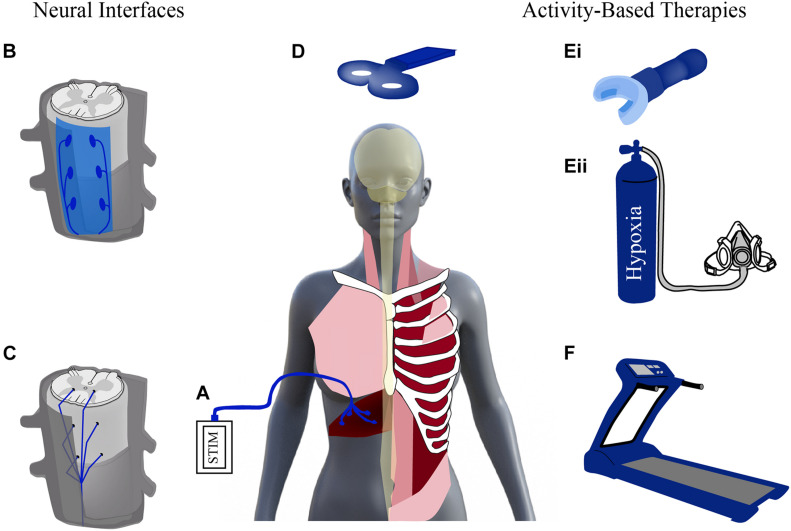

Given the promise seen with neuroplasticity after SCI, there has been increased effort in the past decade to develop treatments capable of enhancing this plasticity and promoting respiratory recovery after injury. These treatments stimulate the nervous system either through neural interfacing (e.g., electrical stimulation) or through physical stimuli (e.g., locomotor training and respiratory rehabilitation) (Figure 2). Stimulation activates spared neural networks and can encourage the formation of new pathways, contributing to modest repair of damaged circuitry. These activation strategies can promote beneficial changes in anatomical and functional plasticity and contribute to improved outcomes after SCI. Important considerations for any of these methods will be timing and dose of the treatment, as well as, efforts to preserve adaptive plasticity and limit maladaptive plasticity.

FIGURE 2.

Stimulating activity to enhance plasticity. Schematic diagram of neural interfaces (left) and activity based (right) strategies to drive neural activity. Neural interfaces include strategies that can be applied to the periphery [e.g., functional electrical stimulation of diaphragm via diaphragm pacer, (A)]. Electrical stimulation can be applied to the spinal cord via epidural stimulation (B) and intraspinal stimulation (C) as well as non-invasively, supraspinally, via transcranial magnetic stimulation (D). Activity-based therapies use physical stimuli to result in increased respiratory drive and neural stimulation via strategies like resistance training (Ei) or intermittent hypoxia (Eii), and locomotor training, e.g., via treadmill (F). Modified from Hormigo et al. (2017), Zholudeva et al. (2018).

Rapid advances are being made in both neural interfacing and electrical stimulation strategies (e.g., intraspinal, epidural, transmagnetic, and functional electrical stimulation; Figure 2). Multidisciplinary collaborations between mechanical and electrical engineers, material scientists and neurobiologists, have led to the development of highly novel and translationally appropriate devices that are being tested in both pre-clinical and clinical studies. Scientists and clinical professionals widely agree, however, that non-invasive rehabilitative strategies will always represent an effective means of helping injured individuals regain some functional improvement. Rehabilitative strategies provide the physical stimulus to enhance plasticity and provide a less invasive alternative to electrical stimulation. One example of these rehabilitative strategies is activity-based training (ABTs).

Activity-Based Therapies

Activity-based therapies (ABTs) have extensively shown to promote neuroplasticity and improve function post-SCI in several sensory, motor, and neurological disorders (stroke, brain injury, and SCI) (Vinit et al., 2009; Dale-Nagle et al., 2010a; Hormigo et al., 2017). ABTs increase activity, often in a repeated, intermittent or “set”-like fashion, in mature neural pathways. Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that these ABT strategies can strengthen existing neuronal networks, stimulate synaptic and dendritic growth/plasticity, and increase baseline neuronal activity (facilitation/potentiation) (Harkema, 2001; Dunlop, 2008; Lynskey et al., 2008; Dale-Nagle et al., 2010a; Singh et al., 2011a,b; Houle and Cote, 2013; Martinez et al., 2013; Hormigo et al., 2017). These changes can also refine and prune synaptic connections and promote the recruitment of other neurons (e.g., spinal interneurons) into the neural network (Rank et al., 2015; Sandhu et al., 2015; Streeter et al., 2017). Spinal interneurons (SpINs) are a vital component of neuroplasticity (Zholudeva and Lane, 2018; Zholudeva et al., 2021), that can change their pattern of activity and are reported to alter their connectivity to contribute to novel anatomical pathways. Most importantly, this neuroplastic potential can be therapeutically driven by either electrical stimulation or ABTs (Harkema, 2008; van den Brand et al., 2012; Houle and Cote, 2013).

In an effort to better understand the mechanisms underlying therapeutically driven plasticity, several pre-clinical studies investigated changes in cytokine expression within the networks being targeted. ABTs have been shown to increase the expression of several neurotrophic factors within the injured spinal cord (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Dunlop, 2008; Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009). A caveat in interpreting the role of these growth factors is their widespread distribution throughout the neural axis. For, example, ABT increases BDNF expression across multiple spinal levels. Despite this, ABT-driven expression of neurotrophic factors within denervated neuronal networks may provide a non-invasive means of attracting axonal growth and enhance functional connectivity (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2005; Sieck and Mantilla, 2009; Bonner et al., 2010, 2011; Weishaupt et al., 2012, 2013; Mantilla et al., 2013; Hernandez-Torres et al., 2017). Serotonergic neurons appear to be especially responsive to increased growth factor expression. Consistent with this notion, there is increased serotonergic input onto spinal motor circuitry and increased serotonergic receptor expression (Houle and Cote, 2013). These neuroplastic molecular changes can be harnessed for therapeutic gain. As the contribution of cytokines to neuroplasticity is more clearly defined, treatments may be better refined to optimize outcome.

Perhaps the most extensively studied ABT is locomotor training, either over-ground, treadmill, or with robotics (e.g., Lokomat®). Locomotor training has demonstrated beneficial effects on plasticity and locomotor function following a range of SCIs, with different spinal levels and severities (Singh et al., 2011a,b; Galea et al., 2013; Hajela et al., 2013; Hillen et al., 2013; Hubli and Dietz, 2013; Martinez et al., 2013; Morawietz and Moffat, 2013; Bonizzato and Martinez, 2021). Locomotor training uses repetition to strengthen muscles, stimulate afferent feedback, enhance motor output, and thus drive related neural plasticity (Harkema, 2001).

While historically the focus of locomotor training was to improve locomotion, it has also been shown to improve a range of non-locomotor functions, including bladder (Ward et al., 2014) and cardiovascular function (Ditor et al., 2005a,b; Hicks and Ginis, 2008). More recent studies have also demonstrated that treadmill training can enhance respiratory recovery in people with chronic cervical and thoracic injuries (Terson de Paleville et al., 2013). This improvement in respiratory function was speculated to be due to increased heart rate and minute ventilation (increase cardiopulmonary activity) during treadmill training (Terson de Paleville et al., 2013). However, the extent of respiratory improvement may also be “dose-dependent.” Terson de Paleville saw improvements in respiratory function for subjects who received 60 min of stepping on a treadmill, 5 days a week for an average of about 12 weeks (Terson de Paleville et al., 2013). In contrast, individuals who received passive robot-assisted stepping did not improve cardiopulmonary function (Jack et al., 2011). One limitation might be achieving sufficient increase in limb afferent stimulation to encourage locomotor-respiratory coupling post-SCI (Sherman et al., 2009). This hypothesis is supported by hindlimb stimulation (a passive event) producing respiratory rhythm entrainment (Iscoe and Polosa, 1976; Morin and Viala, 2002; Potts et al., 2005), increasing phrenic motor output (Persegol et al., 1993).

While the mechanisms explaining how locomotor training can promote respiratory plasticity remain unclear, there are some lines of evidence suggesting that training in the activity you wish to recover might provide a more direct and efficacious strategy. Thus, there has been growing interest in the field of SCI, to entrain respiratory plasticity by stimulating and increasing respiratory activity.

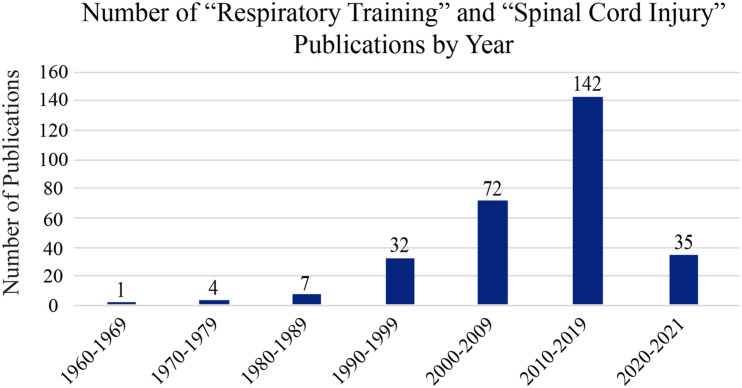

Respiratory Training

Respiratory training is the repetitive activation (either electrical or physical) of inspiratory and expiratory muscles in a systematic way to strengthen respiratory pathways and the muscles they innervate. The term “respiratory training” originated from respiratory axillary muscle training to improve breathing after cervical SCI in 1967 (Imamura, 1967). As the number of publications on respiratory training and SCI continues to increase, so has the definition and use for “respiratory training” (Figure 3). While the origins of respiratory training are within exercise physiology, it has also been used in elderly populations and for many disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, speech pathologies, and voice disorders (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006). Respiratory training now broadly refers to strengthening the primary and accessory (including inspiratory and expiratory) respiration muscles (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006; Sapienza et al., 2011). These are further divided into inspiratory and expiratory training strategies (Bolser et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2011; Sapienza et al., 2011; Laciuga et al., 2014). Deciding which training paradigm to use depends on the needs of the individual. For example, an individual with a high cervical injury will have inspiratory and expiratory deficits and will require a training technique that targets both muscle groups. However, an individual with a lower thoracic injury may require techniques targeting expiratory muscles.

FIGURE 3.

Publication history of respiratory training post-SCI. A PubMed search was made using the terms “respiratory training” and “spinal cord injury” to assess the relative number of research papers on this topic over the last 60 years. As the image shows, interest on this topic is increasing exponentially with each decade.

Resistance Muscle Strength Training

The goal of any muscle strength training (MST) is to enhance the ability of the neuromuscular system to respond to a demand of gradually increasing intensity. This intensity is defined in terms of load amount and duration of the exercise task (e.g., minutes per day × days per week × total weeks) (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006). The total stimulus should increase the activity of the neuromuscular system beyond the normal level (Mueller et al., 2006) and drive it to adapt to increased demand (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006). Typical MST paradigms in the clinic consist of three sessions (with 25–30 repetitions), 3–5 days per week, 4–8 weeks (Carpinelli and Otto, 1998; Schlumberger et al., 2001; Rhea et al., 2002; Sapienza et al., 2011). The intensity of MST can directly affect improvement in respiratory muscle strength (Raab et al., 2019).

There are two main MST strategies: resistance and threshold training. Resistance MST consists of breathing through a small diameter hole, making the participant breathe harder due to the limited airflow (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006; Berlowitz and Tamplin, 2013; Raab et al., 2019). It can be targeted toward either inspiratory or expiratory muscles (Roth et al., 2010) or combined (Kim et al., 2017). Combined training resulted in increased forced vital capacity and expiratory volume, demonstrating improved pulmonary function compared to the respiratory muscle training alone and control group (Kim et al., 2017). Threshold MST forces the individual to modulate their breathing to overcome a spring-loaded valve controlling the airflow (Sapienza and Wheeler, 2006; Galeiras Vazquez et al., 2013; Raab et al., 2019). Resistance and threshold MST result in improved breathing, facilitates weaning from mechanical ventilation (Aldrich et al., 1989; Martin et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2014), and has beneficial effects in secondary respiratory behaviors [e.g., sneezing, sniffing, or coughing (Postma et al., 2015; Aslan et al., 2016; Legg Ditterline et al., 2018; Shin et al., 2019)].

Altering Inhaled Air for Respiratory Training

An alternative to direct electrical stimulation or resistance training of respiratory muscles is non-invasive peripheral and central chemoreceptor activation. For example, hypoxia (decreased oxygen) and hypercapnia (increased carbon dioxide) have been used to elicit activity within the phrenic network (Millhorn et al., 1980; Nielsen et al., 1986). These types of chemical activation have been used to stimulate respiratory drive and elicit neuroplasticity non-invasively. For example, Millhorn et al. (1980) discovered that stimulation of the peripheral and central chemoreceptors resulted in a lasting increase of phrenic activity (Millhorn et al., 1980). Building on this Bach and Mitchell (1996) used three, 5-min bursts of hypoxia (intermittent with room air) to stimulate this chemoreceptor activity and elicit a lasting (hours) increase in phrenic nerve activity (Bach and Mitchell, 1996), termed long-term phrenic facilitation (LTF). LTF is an example of respiratory neuroplasticity characterized by a period of enhanced neural output following a single stimulation paradigm (Fuller et al., 2000; Mitchell et al., 2001). When the same paradigm was applied to hypercapnia (10% CO2) stimulation paradigm resulted in long-term depression (LTD), effectively decreasing phrenic nerve output (Bach and Mitchell, 1996, 1998). Important to note is lowering CO2 levels (to 5%) or limiting exposure to 3–5 min does not elicit this LTD (Baker and Mitchell, 2000; Baker et al., 2001). These episodic exposures also elicit LTF for hypoxia and hypercapnia, but not continuous exposure paradigms (Baker and Mitchell, 2000; Baker et al., 2001).

Increased phrenic plasticity from intermittent hypoxia or hypercapnia led to using these strategies as an alternative method of “respiratory training.” This form of respiratory training is modeled after other rehabilitative ABTs [reviewed in Dale-Nagle et al. (2010b); Dale et al. (2014), Gonzalez-Rothi et al. (2015, 2021)]. Most importantly, this training activates chemoreceptors to drive respiration and provides a non-invasive means of attracting axonal growth, enhancing respiratory functional connectivity to improve breathing (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2005; Sieck and Mantilla, 2009; Bonner et al., 2010, 2011; Weishaupt et al., 2012, 2013; Mantilla et al., 2013; Hernandez-Torres et al., 2017).

Intermittent Hypoxia

Intermittent hypoxia (IH) has been studied both experimentally and clinically as a non-invasive means of stimulating respiratory output. This “activity-based” respiratory training has been used to enhance neuroplasticity, particularly with a focus on the phrenic network, and, improved respiration (Fuller et al., 2003; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003; Vinit et al., 2009; Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009). While a vast range of paradigms have been developed to test IH, the three most commonly reported strategies used in rodent models are:

-

•

Acute intermittent hypoxia (AIH); short exposures (e.g., 3 × 5 min each, or 5 × 3 min each), given in a single day.

-

•

Daily acute intermittent hypoxia (dAIH; short, daily exposures over several days (e.g., 10 hypoxia episodes per day for 5–7 days.

-

•

Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH); e.g., 72 episodes of hypoxia for 1–2 weeks or more.

Examples of these studies are reviewed in Dale-Nagle et al. (2010b). All paradigms effectively improve respiratory outcomes at multiple time points, including 2–10 weeks post spinal cord injury in rodents (Ling et al., 2001; Dale-Nagle et al., 2010b). While chronic intermittent hypoxia was able to enhance plasticity at the level of the phrenic motor pool and enhance crossed phrenic pathways (Fuller et al., 2003), it also led to significant cognitive (Row, 2007), metabolic (Tasali and Ip, 2008), and hypertensive (Fletcher et al., 1992) deficits, and decreased levels of BDNF within the hippocampus (Vinit et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2010; Navarrete-Opazo and Mitchell, 2014). Therefore, almost all IH training paradigms are now done daily with acute intermittent timing (Dale-Nagle et al., 2010b; Gonzalez-Rothi et al., 2015).

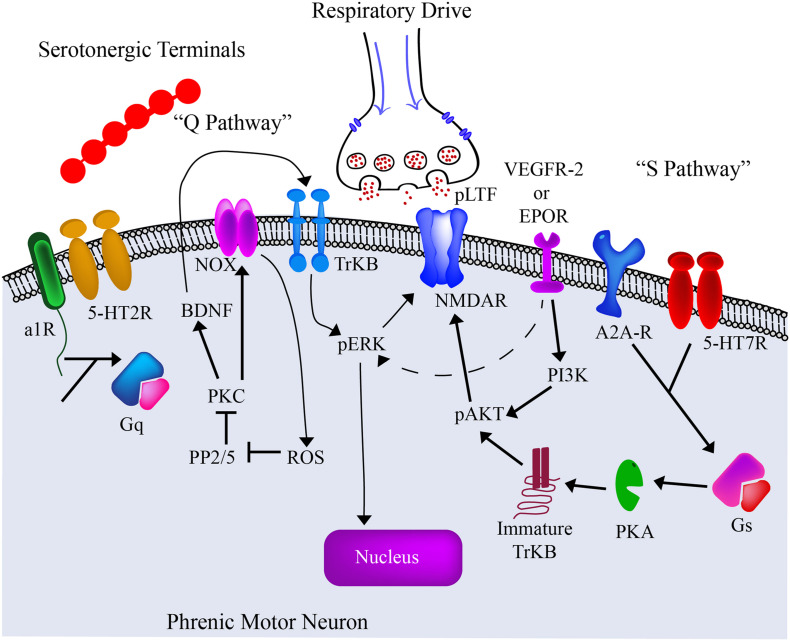

The mechanisms by which hypoxia induces LTF and phrenic plasticity are both complex and multifaceted. IH respiratory training has demonstrated the ability to elicit serotonin dependent plasticity (Ling et al., 2001; Mitchell et al., 2001; Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2002; Golder and Mitchell, 2005; Dale-Nagle et al., 2010b; Devinney et al., 2013), and enhance bulbospinal axon sprouting into phrenic circuitry (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Dale-Nagle et al., 2010b; Gonzalez-Rothi et al., 2015). There are two main pathways described as the “Q” and “S” pathways of promoting neuroplasticity [reviewed in Dale et al. (2014); Hassan et al. (2018); Figure 4]. These pathways get their name from the primary type of G protein-coupled receptor (Gs or Gq) activated.

FIGURE 4.

The current model of the “Q” and “S” Pathways. The past several decades has seen significant advances in our understanding of intermittent hypoxia and its effects on the spinal phrenic network. Particular focus has been given to changes on the phrenic motoneuron itself. From these ongoing studies we are gaining an appreciation of the cellular receptors and intracellular pathways that contribute to plasticity and altered motor function under different respiratory conditions. The current pre-clinical and clinical goal is to employ therapeutic strategies that can harness these mechanisms and enhance motor output after spinal cord injury or disease. Adapted from Dale-Nagle et al. (2010b); Gonzalez-Rothi et al. (2015).

In addition to upregulating molecular markers for plasticity, hypoxia has also been shown to enhance interneuronal plasticity and connectivity, and alter motor output. Studies have identified that spinal interneurons (SpINs) can respond to hypoxia (Lane et al., 2009; Sandhu et al., 2015) and can be recruited following IH training (Streeter et al., 2017).

Intermittent hypoxia training has also been shown to increase plasticity in non-respiratory networks (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 5). Pre-clinical studies reported 7 days of IH in rats with cervical SCI improved performance on the horizontal ladder test (Lovett-Barr et al., 2012; Prosser-Loose et al., 2015; Hassan et al., 2018). IH has also been used in conjunction with specific tasks resulting in synergistic improvements in locomotion (Lovett-Barr et al., 2012), reaching and grasping techniques (Prosser-Loose et al., 2015).

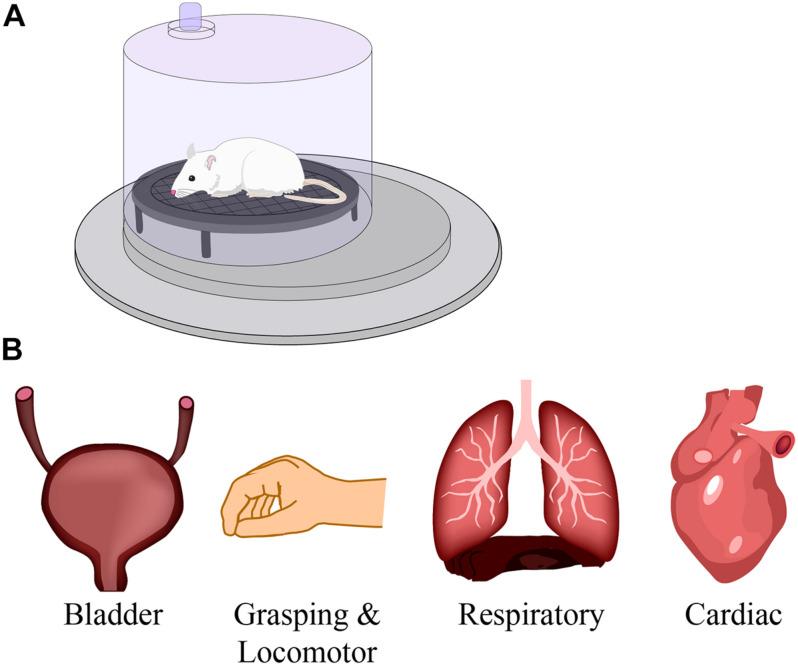

FIGURE 5.

The effect of respiratory training on neural networks. The studies described in this review use respiratory training, such as intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia in a pre-clinical model (A), to improve respiratory function after spinal cord injury. However, numerous studies have reported beneficial effects on other motor networks such as bladder, grasping and locomotion, and cardiac systems (B). Modified from Zholudeva and Lane (2019).

Building on the pre-clinical data, clinical studies first focused on ankle flexion in chronic incomplete SCI individuals (see Supplementary Table 2). IH training significantly improved maximal plantarflexion torque and gastrocnemius electromyographic activity that lasted up to 4 h after the initial IH administration (Trumbower et al., 2012). This not only demonstrated a persistent neuroplastic effect of IH training, but provided evidence of enhanced motor function in people living with SCI. IH training was subsequently shown to improve both walking speed 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT), distance and endurance 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) at 1 day and 1 week during training, and the 1 week follow up (Hayes et al., 2014). Combined IH training with 30 min of overground walking, showed even greater improvement in locomotion speed and distance (Hayes et al., 2014). This improvement may demonstrate that combinatorial therapies may promote greater synergistic functional benefits in injured individuals (Hayes et al., 2014). More recent use of IH training has shown that there is a persistent effect in locomotor facilitation over time and that this can be further maintained with three IH treatments per week after the initial combinatorial walk/IH training (Navarrete-Opazo et al., 2017a). Similarly, combined IH training with hand exercises revealed improved hand dexterity function and maximum hand opening in all participants (Trumbower et al., 2017).

Compromised bladder and bowel function has profound impacts on quality of life for those living with SCI, including a loss of independence, increased risk of infection from catheter use or from incomplete bladder voiding, and autonomic dysreflexia. While there are no clinical studies looking at IH and bladder and bowel function, some animal models are investigating IH and lower urinary tract plasticity. In brief, Collins et al. (2017) revealed that IH-induced neuroplasticity can improve lower urinary tract function in rats with chronic incomplete SCI and may provide a non-invasive method of improving bladder function within the SCI patient population (Collins et al., 2017).

Another respiratory deficit that arises following cervical SCI is sleep-disordered breathing. A consequence of this is obstructive sleep apnea that can result in chronic episodes of hypoxia and hypercapnia, contributing to cardiovascular morbidity, high blood pressure, increased sympathetic nerve activity, cardiac arrhythmia and myocardial infarction (Prabhakar et al., 2005). However, IH consisting of 3–4 rounds of 5–7 min exposures at 12–10% O2 for 2–3 weeks can benefit cardiovascular diseases such as decreased hypertension, coronary heart disease, and heart failure (Serebrovskaya and Xi, 2016). While these initial studies were conducted on spinally intact individuals, future work can begin to assess the potential in people living with SCI.

In summary, IH has demonstrated the ability to improve respiratory function, elicit serotonin and neurotrophic factor dependent plasticity, enhance bulbospinal axonal sprouting into active phrenic circuitry, and recruit populations of SpINs. Clinically, IH training has also been investigated for its ability to promote recovery of both respiratory (Vinit et al., 2009; Tester et al., 2014) and non-respiratory (Trumbower et al., 2012, 2017; Dale et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2014) motor functions.

Intermittent Hypercapnia

Like hypoxia, exposure to hypercapnia (elevated CO2) has also been used to increase respiratory drive via central and peripheral chemoreceptor activation. There is evidence that hypercapnia and hypoxia activate chemoreceptors differently (Long et al., 1994) and that hypercapnia can act as a stronger respiratory stimulant than hypoxia (Somers et al., 1989; Nattie and Li, 2012). This chemoreceptor activity is also enhanced in individuals with chronic SCI compared to non-injured individuals (Bascom et al., 2016).

Hypercapnia as a respiratory stimulus has been shown to increase activity within several brainstem nuclei, including the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) and those within the ventral respiratory column (VRC) (Millhorn and Eldridge, 1986; Guyenet et al., 2012, 2019; Molkov et al., 2014; Wakai et al., 2015). Following hypercapnia exposure, there is an increased drive from the RTN to the VRC resulting in increased amplitude and frequency of phrenic output (Molkov et al., 2014). Within the nucleus tractus solitarius, the principal visceral sensory nucleus, PHOX2B-expressing neurons exhibit CO2 sensitivity and increase activity after exposure to hypercapnia (Fu et al., 2019). Another crucial effect of hypercapnia on brainstem nuclei is the activation of the dorsal raphe (containing serotonergic neurons) (Smith et al., 2018; Kaur et al., 2020). Because carotid chemoafferents also activate raphe, there is also reason to believe that exposure to hypercapnia and hypoxia may further enhance serotonin-dependent mechanisms of plasticity beyond hypoxia alone (Welch, 2021).

While plasticity pathways are well studied following IH, the molecular changes post hypercapnia are not well defined. Overall, hypercapnia is known to upregulate many transcription factors responsible for respiration, motor, and immune function [reviewed in Shigemura et al. (2020)]. In light of the documented “S” and “Q” Pathways (Figure 4), hypercapnia is believed to activate the A2a receptors (Bach and Mitchell, 1998; Kinkead et al., 2001) as part of the initial “S” pathway. Consistent with this, exposure to severe hypercapnia (10% CO2) inhibits plasticity, resulting in long-term phrenic depression (LTD), which is attenuated with the delivery of an A2a receptor antagonist (Bach and Mitchell, 1998). However, it is important to note that lower hypercapnia concentrations (3–5% CO2) does not elicit LTD (Bach and Mitchell, 1998), and thus may drive other molecular pathways.

While hypoxia has been shown to have has a greater effect on respiratory timing, hypercapnia has a more significant effect on peak phrenic nerve activity (Ledlie et al., 1981). Together hypoxia and hypercapnia exposure demonstrate excitation to increase muscle sympathetic nerve activity (Jouett et al., 2015). Also, combined hypoxia and hypercapnia exposure leads to an increase in ipsilateral diaphragm activity but not intercostal activity after a mid-cervical contusion (Wen and Lee, 2018). Furthermore, intermittent hypoxia-hypercapnia following mid-cervical contusion induces an increase in tidal volume, whereas inactivation of the 5-HT7 receptor (Gs coupled protein) combined with this treatment further transiently improved this recovery (Wu et al., 2020). However, more studies need to be done to further understand the implication of the Gs or Gq pathway in this recovery.

A potential therapeutic advantage of hypercapnia training is that unlike IH it maintains normoxia. It has also been shown that hypercapnia can act as a more potent respiratory stimulus than hypoxia (Somers et al., 1989; Nattie and Li, 2012). Increased respiratory neural drive (brainstem) results in increased phrenic output (phrenic nerve and diaphragm) which contributes to entrainment of spared circuits after SCI, activation of latent pathways (Zhou et al., 2001b; Zimmer et al., 2007), as well as anatomical plasticity (e.g., the formation of novel neural circuits) (Baker et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2003). Apart from anatomical plasticity, intermittent hypercapnia elicits functional changes in respiratory circuits after SCI (Baker et al., 2001). A summary of studies using hypercapnia to enhance anatomical and functional neural plasticity is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Closing Remarks

With the mounting clinical and experimental evidence for plasticity after spinal cord injury, tremendous effort is being made to develop treatments that can reduce maladaptive changes, and act synergistically with ongoing adaptive changes, to further optimize the benefits of neuroplasticity. These neural interfacing and activity-based therapies are being extensively clinically tested, which also speaks to their translational relevance. Combining neural interfacing with activity-based therapies has already shown to be effective for promoting recovery of non-respiratory functions (van den Brand et al., 2012), so it is tempting to predict that similar benefits may be achievable for respiratory functions. Even greater benefit may come from combining these approaches with other therapies, such as cellular or biomaterial transplantation, or administration of pro-regenerative compounds, that can promote greater anatomical growth and repair. The future of therapeutic development for respiratory function and plasticity after spinal cord injury holds great promise.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank David S. K. Magnuson (Friends for Michael Chair, Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, University of Louisville) for his comments and contribution to the definitions provided in Box 1.

Funding

This work was supported by the Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation (LZ), Fondation de France and Fondation Médisite, INSERM, and Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (SV), National Institutes of Health R01 NS104291, Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation, Wings for Life Spinal Cord Research Foundation, and Craig H. Neilsen 465068 (ML).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2021.700821/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aldrich T. K., Karpel J. P., Uhrlass R. M., Sparapani M. A., Eramo D., Ferranti R. (1989). Weaning from mechanical ventilation: adjunctive use of inspiratory muscle resistive training. Crit. Care Med. 17 143–147. 10.1097/00003246-198902000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Argote S., Gransee H. M., Mora J. C., Stowe J. M., Jorgenson A. J., Sieck G. C., et al. (2016). The Impact of Midcervical Contusion Injury on Diaphragm Muscle Function. J. Neurotrauma 33 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anke A., Aksnes A. K., Stanghelle J. K., Hjeltnes N. (1993). Lung volumes in tetraplegic patients according to cervical spinal cord injury level. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 25 73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B. M., Toosi B. M., Caine S., Mitchell G. S., Muir G. D. (2021). Prolonged acute intermittent hypoxia improves forelimb reach-to-grasp function in a rat model of chronic cervical spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 340:113672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan S. C., Randall D. C., Krassioukov A. V., Phillips A., Ovechkin A. V. (2016). Respiratory Training Improves Blood Pressure Regulation in Individuals With Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 97 964–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad B. I., Warren P. M., Steinmetz M. P., Alilain W. J. (2013). The role of the crossed phrenic pathway after cervical contusion injury and a new model to evaluate therapeutic interventions. Exp. Neurol. 248 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach K. B., Mitchell G. S. (1996). Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir. Physiol. 104 251–260. 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach K. B., Mitchell G. S. (1998). Hypercapnia-induced long-term depression of respiratory activity requires alpha2-adrenergic receptors. J. Appl. Physiol. 84 2099–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. L., Fuller D. D., Zabka A. G., Mitchell G. S. (2001). Respiratory plasticity: differential actions of continuous and episodic hypoxia and hypercapnia. Respir. Physiol. 129 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. L., Mitchell G. S. (2000). Episodic but not continuous hypoxia elicits long-term facilitation of phrenic motor output in rats. J. Physiol. 529 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman T. L., Fuller D. D., Bavis R. W., Zabka A. G., Golder F. J., Doperalski N. J., et al. (2004). BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat. Neurosci. 7 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman T. L., Mitchell G. S. (2002). Phrenic long-term facilitation requires spinal serotonin receptor activation and protein synthesis. J. Neurosci. 22 6239–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascom A. T., Sankari A., Badr M. S. (2016). Spinal cord injury is associated with enhanced peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity. Physiol. Rep. 4:e12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baussart B., Stamegna J. C., Polentes J., Tadie M., Gauthier P. (2006). A new model of upper cervical spinal contusion inducing a persistent unilateral diaphragmatic deficit in the adult rat. Neurobiol. Dis. 22 562–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz D. J., Tamplin J. (2013). Respiratory muscle training for cervical spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7:CD008507. 10.1002/14651858.CD008507.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser D. C., Jefferson S. C., Rose M. J., Tester N. J., Reier P. J., Fuller D. D., et al. (2009). Recovery of airway protective behaviors after spinal cord injury. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 169 150–156. 10.1016/j.resp.2009.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzato M., Martinez M. (2021). An intracortical neuroprosthesis immediately alleviates walking deficits and improves recovery of leg control after spinal cord injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 13:eabb4422. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb4422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J. F., Blesch A., Neuhuber B., Fischer I. (2010). Promoting directional axon growth from neural progenitors grafted into the injured spinal cord. J. Neurosci. Res. 88 1182–1192. 10.1002/jnr.22288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J. F., Connors T. M., Silverman W. F., Kowalski D. P., Lemay M. A., Fischer I. (2011). Grafted neural progenitors integrate and restore synaptic connectivity across the injured spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 31 4675–4686. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4130-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R., Dimarco A. F., Hoit J. D., Garshick E. (2006). Respiratory dysfunction and management in spinal cord injury. Respir. Care 51 853–868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpinelli R. N., Otto R. M. (1998). Strength training. Single versus multiple sets. Sports Med 26 73–84. 10.2165/00007256-199826020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H., Liao W. L., Newton K. M., Onario R. C., King A. M., Desilets F. C., et al. (2005). Respiratory abnormalities resulting from midcervical spinal cord injury and their reversal by serotonin 1A agonists in conscious rats. J. Neurosci. 25 4550–4559. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5135-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen L., Chen B., Lei Y., Urbin M. A., Richardson M. S. A., Oudega M., et al. (2021). Acute intermittent hypoxia boosts spinal plasticity in humans with tetraplegia. Exp. Neurol. 335:113483. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla M. C., Seven Y. B., Allen L. L., Smith K. N., Asa Z. A., Simon A. K., et al. (2021). Serotonergic innervation of respiratory motor nuclei after cervical spinal injury: impact of intermittent hypoxia. Exp. Neurol. 338:113609. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins W., Phagu N., Catege M., Solomon I. (2017). Improvement in Lower Urinary Tract Function Following a Single Bout of Acute Intermittent Hypoxia in Rats with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. FASEB J. 31 724.8–724.8. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal K., DiMarco A. F. (2014). Diaphragmatic pacing in spinal cord injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 25 619–629. 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale E. A., Ben Mabrouk F., Mitchell G. S. (2014). Unexpected benefits of intermittent hypoxia: enhanced respiratory and nonrespiratory motor function. Physiology 29 39–48. 10.1152/physiol.00012.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle E. A., Hoffman M. S., Macfarlane P. M., Mitchell G. S. (2010a). Multiple pathways to long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 669 225–230. 10.1007/978-1-4419-5692-7_45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle E. A., Hoffman M. S., Macfarlane P. M., Satriotomo I., Lovett-Barr M. R., Vinit S., et al. (2010b). Spinal plasticity following intermittent hypoxia: implications for spinal injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1198 252–259. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05499.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlot F., Cayetanot F., Gauthier P., Matarazzo V., Kastner A. (2012). Extensive respiratory plasticity after cervical spinal cord injury in rats: axonal sprouting and rerouting of ventrolateral bulbospinal pathways. Exp. Neurol. 236 88–102. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Troyer A., Estenne M. (1990). Chest wall motion in paraplegic subjects. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 141 332–336. 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Troyer A., Estenne M., Vincken W. (1986). Rib cage motion and muscle use in high tetraplegics. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 133 1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinney M. J., Huxtable A. G., Nichols N. L., Mitchell G. S. (2013). Hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation: emergent properties. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1279 143–153. 10.1111/nyas.12085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVivo M. J., Black K. J., Stover S. L. (1993). Causes of death during the first 12 years after spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 74 248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep T. T., Khan T. R., Zhang R., Duffin J. (2007). Long-term facilitation of breathing is absent after episodes of hypercapnic hypoxia in awake humans. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 156 132–136. 10.1016/j.resp.2006.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMarco A. F. (2005). Restoration of respiratory muscle function following spinal cord injury. Review of electrical and magnetic stimulation techniques. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 147 273–287. 10.1016/j.resp.2005.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditor D. S., Kamath M. V., Macdonald M. J., Bugaresti J., Mccartney N., Hicks A. L. (2005a). Effects of body weight-supported treadmill training on heart rate variability and blood pressure variability in individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Appl. Physiol. 98 1519–1525. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01004.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditor D. S., Macdonald M. J., Kamath M. V., Bugaresti J., Adams M., Mccartney N., et al. (2005b). The effects of body-weight supported treadmill training on cardiovascular regulation in individuals with motor-complete SCI. Spinal Cord 43 664–673. 10.1038/sj.sc.3101785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doperalski N. J., Fuller D. D. (2006). Long-term facilitation of ipsilateral but not contralateral phrenic output after cervical spinal cord hemisection. Exp. Neurol. 200 74–81. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty B. J., Terada J., Springborn S. R., Vinit S., Macfarlane P. M., Mitchell G. S. (2018). Daily acute intermittent hypoxia improves breathing function with acute and chronic spinal injury via distinct mechanisms. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 256 50–57. 10.1016/j.resp.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop S. A. (2008). Activity-dependent plasticity: implications for recovery after spinal cord injury. Trends Neurosci. 31 410–418. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engwall M. J., Vidruk E. H., Nielsen A. M., Bisgard G. E. (1988). Response of the goat carotid body to acute and prolonged hypercapnia. Respir. Physiol. 74 335–344. 10.1016/0034-5687(88)90041-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J. L. (1986). “Neurophysiology of breathing in mammals,” in Handbook of Physiology - The Nervous System IV, ed. Bloom F. E. (Bethesda: American Physiological Society; ), 463–524. 10.1002/cphy.cp010409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J. L., Mitchell G. S., Nattie E. E. (2003). Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26 239–266. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. C., Lesske J., Qian W., Miller C. C., III, Unger T. (1992). Repetitive, episodic hypoxia causes diurnal elevation of blood pressure in rats. Hypertension 19 555–561. 10.1161/01.HYP.19.6.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Shi L., Wei Z., Yu H., Hao Y., Tian Y., et al. (2019). Activation of Phox2b-Expressing Neurons in the Nucleus Tractus Solitarii Drives Breathing in Mice. J. Neurosci. 39 2837–2846. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2048-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. D., Bach K. B., Baker T. L., Kinkead R., Mitchell G. S. (2000). Long term facilitation of phrenic motor output. Respir. Physiol. 121 135–146. 10.1016/S0034-5687(00)00124-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. D., Doperalski N. J., Dougherty B. J., Sandhu M. S., Bolser D. C., Reier P. J. (2008). Modest spontaneous recovery of ventilation following chronic high cervical hemisection in rats. Exp. Neurol. 211 97–106. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. D., Johnson S. M., Olson E. B., Jr., Mitchell G. S. (2003). Synaptic pathways to phrenic motoneurons are enhanced by chronic intermittent hypoxia after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 23 2993–3000. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02993.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. D., Sandhu M. S., Doperalski N. J., Lane M. A., White T. E., Bishop M. D., et al. (2009). Graded unilateral cervical spinal cord injury and respiratory motor recovery. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 165 245–253. 10.1016/j.resp.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea M. P., Dunlop S. A., Davis G. M., Nunn A., Geraghty T., Hsueh Y. S., et al. (2013). Intensive exercise program after spinal cord injury (”Full-On”): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 14:291. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeiras Vazquez R., Rascado Sedes P., Mourelo Farina M., Montoto Marques A., Ferreiro Velasco M. E. (2013). Respiratory management in the patient with spinal cord injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:168757. 10.1155/2013/168757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garshick E., Kelley A., Cohen S. A., Garrison A., Tun C. G., Gagnon D., et al. (2005). A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43 408–416. 10.1038/sj.sc.3101729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali M. G. (2017). The bulbospinal network controlling the phrenic motor system: laterality and course of descending projections. Neurosci. Res. 121 7–17. 10.1016/j.neures.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill L. C., Gransee H. M., Sieck G. C., Mantilla C. B. (2016). Functional recovery after cervical spinal cord injury: role of neurotrophin and glutamatergic signaling in phrenic motoneurons. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 226 128–136. 10.1016/j.resp.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder F. J., Fuller D. D., Davenport P. W., Johnson R. D., Reier P. J., Bolser D. C. (2003). Respiratory motor recovery after unilateral spinal cord injury: eliminating crossed phrenic activity decreases tidal volume and increases contralateral respiratory motor output. J. Neurosci. 23 2494–2501. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02494.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder F. J., Fuller D. D., Lovett-Barr M. R., Vinit S., Resnick D. K., Mitchell G. S. (2011). Breathing patterns after mid-cervical spinal contusion in rats. Exp. Neurol. 231 97–103. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder F. J., Mitchell G. S. (2005). Spinal synaptic enhancement with acute intermittent hypoxia improves respiratory function after chronic cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 25 2925–2932. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0148-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder F. J., Reier P. J., Bolser D. C. (2001). Altered respiratory motor drive after spinal cord injury: supraspinal and bilateral effects of a unilateral lesion. J. Neurosci. 21 8680–8689. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08680.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rothi E. J., Lee K. Z., Dale E. A., Reier P. J., Mitchell G. S., Fuller D. D. (2015). Intermittent hypoxia and neurorehabilitation. J. Appl. Physiol. 119 1455–1465. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00235.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rothi E. J., Tadjalli A., Allen L. L., Ciesla M. C., El Chami M., Mitchell G. (2021). Protocol-specific effects of intermittent hypoxia preconditioning on phrenic motor plasticity in rats with chronic cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 38 1292–1305. 10.1089/neu.2020.7324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian H. G. (2003). The crossed phrenic phenomenon: a model for plasticity in the respiratory pathways following spinal cord injury. J. Appl. Physiol. 94 795–810. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian H. G. (2009). The crossed phrenic phenomenon and recovery of function following spinal cord injury. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 169 85–93. 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee H. M., Zhan W. Z., Sieck G. C., Mantilla C. B. (2015). Localized delivery of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-expressing mesenchymal stem cells enhances functional recovery following cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 32 185–193. 10.1089/neu.2014.3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin H. S., Pugh K., Kumar P., Balanos G. M. (2012). Long-term facilitation of ventilation following acute continuous hypoxia in awake humans during sustained hypercapnia. J. Physiol. 590 5151–5165. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.236109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez D. V., Clark M., Nwanna O., Alilain W. J. (2013). Intermittent hypoxia training after C2 hemisection modifies the expression of PTEN and mTOR. Exp. Neurol. 248 45–52. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet P. G., Stornetta R. L., Abbott S. B., Depuy S. D., Kanbar R. (2012). The retrotrapezoid nucleus and breathing. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 758 115–122. 10.1007/978-94-007-4584-1_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet P. G., Stornetta R. L., Souza G., Abbott S. B. G., Shi Y., Bayliss D. A. (2019). The Retrotrapezoid Nucleus: central Chemoreceptor and Regulator of Breathing Automaticity. Trends Neurosci. 42 807–824. 10.1016/j.tins.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas F., Axen K., Pineda H., Gandino D., Haas A. (1985). Temporal pulmonary function changes in cervical cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 66 139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajela N., Mummidisetty C. K., Smith A. C., Knikou M. (2013). Corticospinal reorganization after locomotor training in a person with motor incomplete paraplegia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:516427. 10.1155/2013/516427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema S. J. (2001). Neural plasticity after human spinal cord injury: application of locomotor training to the rehabilitation of walking. Neuroscientist 7 455–468. 10.1177/107385840100700514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema S. J. (2008). Plasticity of interneuronal networks of the functionally isolated human spinal cord. Brain Res. Rev. 57 255–264. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D. P., Balasubramaniam A., Badr M. S., Mateika J. H. (2006). Long-term facilitation of ventilation and genioglossus muscle activity is evident in the presence of elevated levels of carbon dioxide in awake humans. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291 R1111–R1119. 10.1152/ajpregu.00896.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A., Arnold B. M., Caine S., Toosi B. M., Verge V. M. K., Muir G. D. (2018). Acute intermittent hypoxia and rehabilitative training following cervical spinal injury alters neuronal hypoxia- and plasticity-associated protein expression. PLoS One 13:e0197486. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F., Coles S. K., Bach K. B., Mitchell G. S., Mccrimmon D. R. (1993). Time-dependent phrenic nerve responses to carotid afferent activation: intact vs. decerebellate rats. Am. J. Physiol. 265 R811–R819. 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes H. B., Jayaraman A., Herrmann M., Mitchell G. S., Rymer W. Z., Trumbower R. D. (2014). Daily intermittent hypoxia enhances walking after chronic spinal cord injury: a randomized trial. Neurology 82 104–113. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000437416.34298.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Torres V., Gransee H. M., Mantilla C. B., Wang Y., Zhan W. Z., Sieck G. C. (2016). BDNF Effects on Functional Recovery across Motor Behaviors after Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurophysiol. 117 537–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Torres V., Gransee H. M., Mantilla C. B., Wang Y., Zhan W. Z., Sieck G. C. (2017). BDNF effects on functional recovery across motor behaviors after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 117 537–544. 10.1152/jn.00654.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks A. L., Ginis K. A. (2008). Treadmill training after spinal cord injury: it’s not just about the walking. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 45 241–248. 10.1682/JRRD.2007.02.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillen B. K., Abbas J. J., Jung R. (2013). Accelerating locomotor recovery after incomplete spinal injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1279 164–174. 10.1111/nyas.12061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M. R., Richerson G. B. (2010). The role of medullary serotonin (5-HT) neurons in respiratory control: contributions to eupneic ventilation, CO2 chemoreception, and thermoregulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 108 1425–1432. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoh D. J., Mercier L. M., Hussey S. P., Lane M. A. (2013). Respiration following spinal cord injury: evidence for human neuroplasticity. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 189 450–464. 10.1016/j.resp.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman M. T., Van Der Woude L. H., Dallmeijer A. J., Snoek G., Folgering H. T. (1997). Respiratory muscle strength and endurance in individuals with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 35 104–108. 10.1038/sj.sc.3100353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormigo K. M., Zholudeva L. V., Spruance V. M., Marchenko V., Cote M. P., Vinit S., et al. (2017). Enhancing neural activity to drive respiratory plasticity following cervical spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 287 276–287. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle J. D., Cote M. P. (2013). Axon regeneration and exercise-dependent plasticity after spinal cord injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1279 154–163. 10.1111/nyas.12052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. H., Lee K. Z. (2015). Effects of serotonergic agents on respiratory recovery after cervical spinal injury. J. Appl. Physiol. 119 1075–1087. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00329.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubli M., Dietz V. (2013). The physiological basis of neurorehabilitation–locomotor training after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 10:5. 10.1186/1743-0003-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T. (1967). [The effect of auxiliary respiratory muscular training on breathing exercise in cervical cord injuries]. Kumamoto Igakkai Zasshi 41 130–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscoe S., Polosa C. (1976). Synchronization of respiratory frequency by somatic afferent stimulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 40 138–148. 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.2.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack L. P., Purcell M., Allan D. B., Hunt K. J. (2011). The metabolic cost of passive walking during robotics-assisted treadmill exercise. Technol. Health Care 19 21–27. 10.3233/THC-2011-0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. B., Groomes T. E. (1994). Incidence of respiratory complications following spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 75 270–275. 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90027-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal P. B., Tester N. J., Davenport P. W. (2016). Effect of acute intermittent hypoxia treatment on ventilatory load compensation and magnitude estimation of inspiratory resistive loads in an individual with chronic incomplete cervical spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 39 103–110. 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen V. N., Alilain W. J., Crone S. A. (2019). Role of Propriospinal Neurons in Control of Respiratory Muscles and Recovery of Breathing Following Injury. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13:84. 10.3389/fnsys.2019.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouett N. P., Watenpaugh D. E., Dunlap M. E., Smith M. L. (2015). Interactive effects of hypoxia, hypercapnia and lung volume on sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Exp. Physiol. 100 1018–1029. 10.1113/EP085092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S., De Luca R., Khanday M. A., Bandaru S. S., Thomas R. C., Broadhurst R. Y., et al. (2020). Role of serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons in hypercapnia-induced arousals. Nat. Commun. 11:2769. 10.1038/s41467-020-16518-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. Y., Lee J. S., Kim H. D., Lee D. J. (2017). Short-term effects of respiratory muscle training combined with the abdominal drawing-in maneuver on the decreased pulmonary function of individuals with chronic spinal cord injury: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Spinal Cord Med. 40 17–25. 10.1080/10790268.2016.1198576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkead R., Bach K. B., Johnson S. M., Hodgeman B. A., Mitchell G. S. (2001). Plasticity in respiratory motor control: intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia activate opposing serotonergic and noradrenergic modulatory systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 130 207–218. 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00393-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komnenov D., Solarewicz J. Z., Afzal F., Nantwi K. D., Kuhn D. M., Mateika J. H. (2016). Intermittent hypoxia promotes recovery of respiratory motor function in spinal cord-injured mice depleted of serotonin in the central nervous system. J. Appl. Physiol. 121 545–557. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00448.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laciuga H., Rosenbek J. C., Davenport P. W., Sapienza C. M. (2014). Functional outcomes associated with expiratory muscle strength training: narrative review. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 51 535–546. 10.1682/JRRD.2013.03.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A. (2011). Spinal respiratory motoneurons and interneurons. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 179 3–13. 10.1016/j.resp.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A., Fuller D. D., White T. E., Reier P. J. (2008a). Respiratory neuroplasticity and cervical spinal cord injury: translational perspectives. Trends Neurosci. 31 538–547. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A., White T. E., Coutts M. A., Jones A. L., Sandhu M. S., Bloom D. C., et al. (2008b). Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 511 692–709. 10.1002/cne.21864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A., Lee K. Z., Fuller D. D., Reier P. J. (2009). Spinal circuitry and respiratory recovery following spinal cord injury. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 169 123–132. 10.1016/j.resp.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M. A., Lee K. Z., Salazar K., O’steen B. E., Bloom D. C., Fuller D. D., et al. (2012). Respiratory function following bilateral mid-cervical contusion injury in the adult rat. Exp. Neurol. 235 197–210. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledlie J. F., Kelsen S. G., Cherniack N. S., Fishman A. P. (1981). Effects of hypercapnia and hypoxia on phrenic nerve activity and respiratory timing. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 51 732–738. 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.3.732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledsome J. R., Sharp J. M. (1981). Pulmonary function in acute cervical cord injury. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 124 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. Z., Chiang S. C., Li Y. J. (2017). Mild Acute Intermittent Hypoxia Improves Respiratory Function in Unanesthetized Rats With Midcervical Contusion. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 31 364–375. 10.1177/1545968316680494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg Ditterline B. E., Aslan S. C., Randall D. C., Harkema S. J., Castillo C., Ovechkin A. V. (2018). Effects of Respiratory Training on Heart Rate Variability and Baroreflex Sensitivity in Individuals With Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 99 423–432. 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S., Nguyen T., Taylor N., Friscia M. E., Budak M. T., Rothenberg P., et al. (2008). Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 358 1327–1335. 10.1056/NEJMoa070447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L. J., Brookhart J. M. (1951). Significance of the crossed phrenic phenomenon. Am. J. Physiol. 166 241–254. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.166.2.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. T., Vinit S., Lee K. Z. (2021). Functional role of carbon dioxide on intermittent hypoxia induced respiratory response following mid-cervical contusion in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 339:113610. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L., Fuller D. D., Bach K. B., Kinkead R., Olson E. B., Jr., Mitchell G. S. (2001). Chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits serotonin-dependent plasticity in the central neural control of breathing. J. Neurosci. 21 5381–5388. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05381.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn W. S., Adkins R. H., Gong H., Jr., Waters R. L. (2000). Pulmonary function in chronic spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional survey of 222 southern California adult outpatients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81 757–763. 10.1016/S0003-9993(00)90107-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long W., Lobchuk D., Anthonisen N. R. (1994). Ventilatory responses to CO2 and hypoxia after sustained hypoxia in awake cats. J. Appl. Physiol. 76 2262–2266. 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Barr M. R., Satriotomo I., Muir G. D., Wilkerson J. E., Hoffman M. S., Vinit S., et al. (2012). Repetitive intermittent hypoxia induces respiratory and somatic motor recovery after chronic cervical spinal injury. J. Neurosci. 32 3591–3600. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2908-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P., Jones L. L., Tuszynski M. H. (2005). BDNF-expressing marrow stromal cells support extensive axonal growth at sites of spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 191 344–360. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]