Dear Editor,

The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is leading to this disease becoming endemic in several countries. Various neurological complications related to COVID-19 have been reported,1,2 one of which is Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a well-known para/postinfectious immune-mediated neuropathy. Since Zhao et al. first reported COVID-19 related GBS, several cases have been reported worldwide, but most were COVID-19 with respiratory symptoms.3,4 Here we report a case of facial diplegia, which is a rare subtype of GBS, during the postinfectious stage of COVID-19 without respiratory symptoms. To our knowledge, this is the first report of GBS associated with COVID-19 in Korea.

A 62-year-old male presented to our hospital with facial diplegia that had first appeared 6 weeks previously. He reported no limb symptoms. He had a past medical history of blindness and mild exotropia in the right eye after an eye trauma in 1976. He was also admitted to a local public medical center after testing positive for COVID-19 infection following a nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, with a fever of up to 39℃ and mild myalgia 2 months previously. He had no respiratory complaints, and chest CT revealed no pneumonic infiltration. Antipyretic drugs resulted in his body temperature returning to normal 2 days after admission, and he did not receive any other medication. The patient was discharged without symptoms on day 10 of admission after a negative nasopharyngeal COVID-19 PCR test.

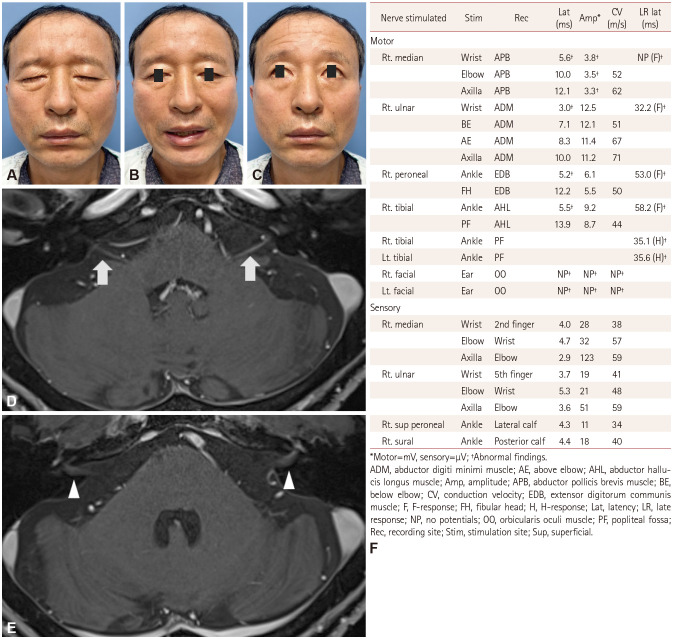

Two days after discharge and 17 days after fever onset, the patient experienced stabbing pain behind the left ear. He found facial asymmetry and bilateral facial muscle weakness upon waking the next morning, which worsened over the following 3 days. The initial neurological examination at our hospital revealed bilateral facial muscle weakness that was worse on the right than the left side (Fig. 1A–C). Other cranial nerve examination, motor examination, sensory examination of all modalities, and examination of the deep tendon reflexes revealed no abnormalities. Blood tests (including inflammatory markers) and chest radiography produced no abnormal findings; serum antiganglioside antibodies (IgG and IgM) including GM1, GM2, GD1a, GD1b, GD3, GT1a, and GQ1b were not detected. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed a protein level of 61 mg/dL and white blood cells at 2/µL. PCR testing of the CSF and nasopharyngeal cavity for COVID-19 was negative. Brain MRI with intravenous gadolinium showed enhancement in the labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid segments in both facial nerves within the internal auditory canals (Fig. 1D and E).

Fig. 1. Clinical phenotype, brain MRI, and nerve conduction study of the patient. Facial diplegia at presentation while: closing the eyes (A), smiling (B), and raising the eyebrows (C). Axial postcontrast T1-weighted MRI showing subtle enhancement along the labyrinthine (white arrows) (D) and tympanic segments (white arrowheads) (E) of the facial nerves bilaterally. F: Nerve conduction study demonstrating motor dominant polyneuropathy with a demyelinating pattern.

Nerve conduction studies of the limbs revealed a motor-dominant polyneuropathy with absent or prolonged late responses (Fig. 1F). Bilateral blink reflexes and facial nerve compound motor action potentials were not detected. Electromyography revealed abundant spontaneous activity in the right first dorsal interossei and bilateral facial muscles.

Facial diplegia with/without limb paresthesia, which is a subtype of GBS,5 was diagnosed. The patient refused intravenous immunoglobulin therapy because of the high cost, and so instead received intravenous steroid therapy for 5 days. After 1 month his symptoms had not improved, but the latency of the distal motor nerve and late response had improved slightly (Supplementary Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement).

This report suggests that in the current pandemic, patients visiting a hospital with new-onset neurological symptoms should undergo COVID-19 testing as part of their evaluation, even when they have no or only mild COVID-19 symptoms. To help clinicians better understand the disease, further characterization of GBS and other neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 is needed.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: All procedures in this study involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Korea University, Ansan Hospital and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for posting and use of photographs.

- Conceptualization: Hwa Been Yang, Hyung-Soo Lee.

- Data curation: Hwa Been Yang, Hyung-Soo Lee.

- Investigation: Hwa Been Yang, Hyung-Soo Lee.

- Supervision: Hyung-Soo Lee.

- Writing—original draft: Hwa Been Yang, Hyung-Soo Lee.

- Writing—review & editing: Hwa Been Yang, Hyung-Soo Lee.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Statement: None

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2021.17.4.590.

The follow-up nerve conduction study after 1 month

References

- 1.Nath A. Neurologic complications of coronavirus infections. Neurology. 2020;94:809–810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:383–384. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Sanctis P, Doneddu PE, Viganò L, Selmi C, Nobile-Orazio E. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. A systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:2361–2370. doi: 10.1111/ene.14462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susuki K, Koga M, Hirata K, Isogai E, Yuki N. A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant with prominent facial diplegia. J Neurol. 2009;256:1899–1905. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The follow-up nerve conduction study after 1 month

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.